1. Introduction

In remote areas, islands, or situations involving grid disconnection or fault-induced islanding, power systems often operate in an “islanded” mode, forming what is known as an isolated power system [

1]. These systems are typically small-scale, with limited resource availability and heightened sensitivity to external disturbances [

2]. With the increasing implementation of dual-carbon policy objectives [

3], traditional fossil-fuel-based generation units in these systems are progressively being replaced by renewable energy sources such as wind and solar power [

4]. As a result, system operation has become increasingly reliant on power-electronics-interfaced sources [

5]. In this context, the frequency support and rotational inertia originally provided by synchronous generators are diminishing, leading to growing concerns about frequency stability [

6]. Particularly in the absence of interconnection with a large power grid, isolated systems are more susceptible to significant frequency deviations or even instability in the event of disturbances [

7]. Therefore, establishing a fast frequency response control mechanism to ensure dynamic stability under high renewable energy penetration has become a critical focus in the control of grid-forming energy storage systems.

To address the insufficient frequency support capacity in isolated power systems, recent research has increasingly focused on grid-forming control strategies based on battery energy storage systems [

8,

9]. Among these strategies, the virtual synchronous machine (VSM) control scheme has emerged as a representative solution. By embedding inertia and damping responses within power electronic converters, VSM control emulates the dynamic behavior of conventional synchronous machines, offering a novel approach to frequency regulation under high renewable energy penetration [

10,

11]. For example, Li et al. emphasized that the effectiveness of VSM control is highly dependent on the configuration of its control parameters, particularly the settings of virtual inertia and damping [

12]. To achieve optimal control performance under different disturbance types, various studies have developed VSM parameter tuning models based on frequency response metrics [

13,

14]. Sun et al. proposed a tuning method that accounts for constraints in storage capacity and response speed, introducing a dual-layer control architecture wherein fast-responding storage emulates inertia and damping, while slow-responding storage provides long-term support [

15]. Elwakil et al. further advanced an adaptive control strategy based on frequency response optimization, enabling dynamic parameter tuning in islanded microgrids [

16]. While these studies have laid a theoretical foundation for VSM parameter optimization, most have concentrated on single-disturbance scenarios and have lacked a systematic approach for multi-disturbance and multi-operating-condition contexts. As energy storage systems are increasingly tasked with balancing functions in islanded grids, there is an urgent need to develop generalized parameter tuning models that can accommodate representative disturbances. Such models would enhance the adaptability and robustness of control strategies under complex operational conditions.

In response to the limitations of fixed-parameter control—particularly its inadequate adaptability and slow response under various disturbance conditions—adaptive control strategies for VSM parameters have gained significant attention in recent years [

17]. A prominent line of research introduces intelligent algorithms such as fuzzy logic and neural networks [

18,

19], which dynamically adjust virtual inertia and damping parameters based on operating conditions such as frequency deviation and power fluctuation. This approach improves both frequency regulation performance and response speed [

20]. For example, Li et al. proposed a deep reinforcement learning-based VSM controller that autonomously tunes virtual inertia and damping to suppress system frequency oscillations [

21]. Another approach utilizes rule-based logic with predefined switching conditions, allowing rapid parameter switching in response to substantial changes in system states to adapt to various disturbance scenarios [

22]. Yu et al., for instance, developed a feedforward reference-based damping tuning method for VSMs that effectively suppresses low-frequency power oscillations without compromising inertia response [

23]. Compared to fixed-parameter schemes, adaptive control strategies can better balance frequency stability with the regulatory burden placed on energy storage systems. However, most existing adaptive strategies lack a unified disturbance identification criterion, which makes it difficult to address multiple disturbances—such as sudden generation losses and voltage fluctuations—simultaneously. Particularly, under fault conditions with significant voltage variations, issues like improper inertia settings and delayed control switching frequently arise, negatively impacting frequency recovery and the overall stability of the system.

Despite notable progress in the modeling, parameter tuning, and adaptive control strategies of VSMs, several critical challenges remain in current research [

24,

25]. On the one hand, most existing parameter tuning methods rely on pre-disturbance operating conditions, limiting their applicability in isolated systems where uncertainties, such as generation unit availability, voltage levels, and synchronous inertia, can dynamically fluctuate. As a result, these methods often show poor generalization across diverse scenarios. On the other hand, many adaptive control strategies are based on single indicators, such as frequency deviation or power error, and lack integrated multi-source information and disturbance identification mechanisms. This shortcoming hampers precise control under complex operational conditions. Particularly, in grid fault scenarios, abrupt voltage sags and the strong dynamic coupling between synchronous machines and grid-forming converters can significantly alter the system’s frequency response pathways. If control parameters designed for steady-state conditions are maintained, this may lead to exacerbated frequency dips or amplified power transients. Furthermore, in practical engineering applications, grid-forming energy storage systems are often required to operate across multiple scenarios. Therefore, the development of a control parameter configuration framework that combines broad applicability with dynamic responsiveness to disturbance variations remains an urgent challenge.

To address the need for dynamic frequency support provided by battery energy storage stations in grid-forming power systems, this study proposes a parameter tuning and adaptive switching strategy for VSM control. First, a comprehensive control model is developed that incorporates virtual inertia, virtual damping, active/reactive power droop control, and transient virtual impedance, enabling a detailed characterization of the dynamic response of energy storage systems under varying operating conditions. Second, an optimization model for control parameter tuning is formulated based on two representative disturbances—generator disconnection and three-phase symmetrical short-circuit faults—to identify the applicability patterns of VSM parameter configurations. Finally, a rule-based adaptive switching mechanism is designed, which utilizes voltage at the converter terminal and system frequency as criteria to achieve integrated mode recognition and real-time parameter updates. This approach aims to enhance the system’s dynamic stability, providing robust frequency regulation even under complex and fluctuating grid conditions.

The features of this study are as follows: (1) An adaptive parameter tuning method for VSM control is proposed, which is applicable to multiple disturbance scenarios, revealing the underlying mechanisms of virtual inertia and damping configurations under different disturbance types; (2) A rule-based adaptive switching strategy for control parameters is developed, significantly enhancing the frequency stability of the grid-forming energy storage system under fault disturbances; (3) The integrated design of control, parameter tuning, and adaptive switching mechanisms is achieved, improving the adaptability and engineering implementability of the control strategy. The similarities and differences between existing research on VSM control in grid-forming systems and this study are summarized in

Table 1.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 develops the power converter control model for the grid-forming energy storage system, providing theoretical support for the subsequent control parameter tuning.

Section 3 focuses on two typical disturbance scenarios and reveals the impact of VSM control parameters on the dynamic frequency characteristics of the system.

Section 4 establishes a model for tuning inertia and damping parameters, analyzing the system frequency response characteristics under two types of disturbances and four scenario combinations.

Section 5 proposes a rule-based adaptive control parameter switching strategy, enhancing the system’s ability to respond to frequency disturbances.

Section 6 presents the conclusions.

2. Control Model of Grid-Forming Energy Storage Systems

This section presents a control-oriented model for the key functional loops within the power converter of a grid-forming energy storage system, encompassing VSM control, virtual speed regulation, reactive power–voltage control, and transient virtual impedance. Here, the term “VSM” specifically refers to the power converter control system of a battery energy storage system operating in a grid-forming mode. By mimicking the dynamic characteristics of a synchronous generator, the VSM facilitates a rapid response to frequency disturbances and is widely recognized as a highly effective method for enhancing frequency stability and providing inertia support in low-inertia power systems [

35]. The overall architecture of the control system implemented in this section is depicted in

Figure 1.

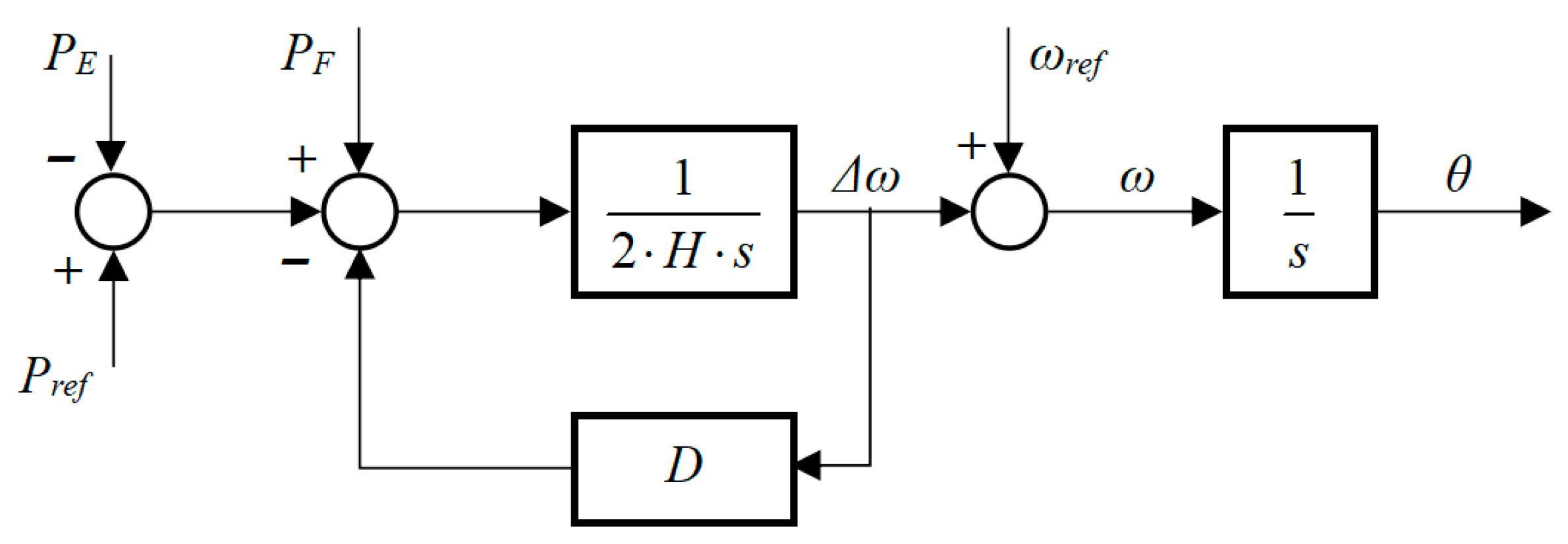

2.1. VSM Control Modeling

A VSM model based on the classical swing equation is introduced to capture the dynamic behavior of synchronous generators induced by inertia and damping characteristics [

36], as illustrated in

Figure 2. The model can be expressed as

Here,

t denotes the current time,

represents the system rated angular frequency, Δ

ω represents the deviation in the virtual rotor’s angular frequency, and

ω is the actual angular frequency.

H is the virtual inertia, and

D is the virtual damping coefficient; both

H and

D are tunable control parameters.

PM and

PE represent the virtual mechanical input power and electrical output power, respectively. All angular frequency and power quantities are expressed in pu. Accordingly, the virtual mechanical power term in Equation (1) can be reformulated as

Here, Pref denotes the active power reference, and PF represents the active power regulation component induced by the virtual rotor’s angular velocity error. The outputs of this module include the angular frequency and the phase angle , where is obtained by integrating . Together, these two variables determine the output voltage’s frequency and phase characteristics.

2.2. Virtual Speed Regulation Control Modeling

The virtual speed regulation controller is designed to emulate the load-frequency control functionality of conventional synchronous generators. As illustrated in

Figure 2, it dynamically adjusts the active power output based on the deviation in the virtual rotor’s angular velocity. The control logic is formulated as follows.

Here, cD denotes the active power–frequency droop coefficient. This module serves as a key component in enabling primary frequency regulation for grid-forming converters, allowing them to autonomously modulate active power output in response to frequency deviations, thereby supporting system frequency stability.

2.3. Reactive Power–Voltage Control Modeling

The reactive power–voltage control module regulates the output voltage magnitude of the converter in response to deviations in reactive power, thereby contributing to system voltage stability. As illustrated in

Figure 3 [

37], the control principle can be expressed as

Here, Qref and Q represent the reference and actual reactive power, respectively (in pu); tD denotes the time constant of the control loop; kD is the reactive power–voltage droop coefficient; Vref is the voltage reference value; V is the output voltage magnitude of the converter. V0 denotes the rated voltage, and V also serves as the target output voltage magnitude of the converter as determined by the controller.

2.4. Transient Virtual Impedance Control Modeling

To effectively limit the converter output current under fault conditions, a transient virtual impedance control strategy is introduced. A virtual impedance is dynamically superimposed at the converter output, with its magnitude adjusted according to the real-time current amplitude [

38]. As illustrated in

Figure 4, when an overcurrent event occurs, the transient virtual impedance controller applies a virtual voltage drop on top of the voltage reference generated by the reactive power–voltage controller, which can be expressed as

where

VC is the compensated output voltage magnitude, and Δ

VVI is the voltage drop introduced by the virtual impedance.

When the current magnitude is below the threshold

, the voltage drop is

where

RVI and

XVI represent the predefined maximum values of virtual resistance and reactance, respectively. When the output current exceeds the threshold

, the controller activates the current-limiting function, and the voltage drop is given by

where

ZVI is the virtual impedance that varies linearly with the output current magnitude, expressed as

The diesel generator unit is modeled using the standard synchronous machine model and the IEEE Type_I automatic voltage regulator model provided in the MATLAB R2013b/Simulink

® toolbox [

39]. The wind power and photovoltaic station systems are modeled based on existing simplified grid-following control models [

40,

41], which describe dynamic response through first-order transfer functions and account for the current-limiting characteristics of power electronic converters.

In summary, the proposed control model for the grid-forming energy storage system integrates key controllers, including VSM, virtual speed regulation, reactive power–voltage control, and transient virtual impedance. Compared with conventional models that simplify power converters as ideal voltage sources or static controllers, this model offers a more precise representation of the converter’s control response under dynamic disturbances. This enhanced accuracy makes it particularly suitable for characterizing system behavior under representative scenarios, such as generator disconnection and short-circuit faults, thus improving the system’s overall stability and responsiveness to various disturbances.

3. Control Parameters and Their Impact on Frequency Dynamic Characteristics

Based on the control model of the grid-forming energy storage system, this section evaluates the influence of VSM control parameters on the system’s frequency dynamic characteristics. Focusing on two representative disturbance scenarios—(1) sudden disconnection of the largest generation unit and (2) occurrence of a three-phase symmetrical short-circuit fault—this analysis elucidates the roles of virtual inertia and damping parameters in shaping the system’s frequency response, thereby providing theoretical support for subsequent parameter tuning.

3.1. System Configuration and Operating Scenario

The study focuses on the power system of a demonstration industrial park located in a mountainous area of Yunnan Province, China, operating in an isolated microgrid mode. This industrial park is rich in renewable energy resources and has deployed medium- to large-scale wind and photovoltaic power generation systems. Due to the relatively weak power grid infrastructure in the region and its unstable connection to the external grid, isolated operation is common. The system serves as a demonstration project for the optimized configuration of grid-forming energy storage, with its topology shown in

Figure 5 and system component parameters listed in

Table 2. The transmission network operates at a voltage level of 20 kV, and the power generation system includes two diesel power plants, one photovoltaic power plant, and two wind farms. The two diesel power plants are equipped with three 15.4 MVA units and three 10 MVA units, respectively; the photovoltaic power plant has an installed capacity of 9.6 MW, occupying 7.6 hectares; the two wind farms have installed capacities of 9.8 MW and 4.9 MW, respectively. The system’s total load fluctuates with time, ranging from 15.6 MW (off-peak) to 31.8 MW (peak). To improve the system’s frequency stability, an 11.5 MW battery energy storage station is introduced, with its power converter operating in VSM control mode to support the system’s frequency regulation in conjunction with at least one diesel generator.

Figure 6 illustrates the typical daily load profile of the industrial park under islanded operation, with the system load fluctuating between 14.5 MW and 28.5 MW. It can be observed that the load remains at around 15 MW during the off-peak period from 2:00 to 5:00. From 6:00 to 10:00, the load exhibits a pronounced increase, reaching a peak of 28.5 MW around 9:00–10:00. Subsequently, between 11:00 and 15:00, the load decreases slightly and stabilizes within the range of 23–25 MW. A secondary peak of approximately 27.5 MW occurs during 17:00–21:00, after which the load gradually declines toward the end of the day (22:00–23:00). As listed in

Table 3, this load profile highlights two representative operational challenges: (1) During the midday and peak periods, the rotational reserve provided by the diesel generators is insufficient; (2) During the off-peak period, the system frequency becomes unstable due to the integration of renewable energy sources.

The system prioritizes scheduling the large-capacity Diesel Generator 1 (15.4 MVA), which operates within a conventional power range of 4.2–12.3 MW. The battery energy storage system serves as a rotating reserve resource for frequency regulation, with an initial output of zero. The system frequency tolerance range is set between 48.5 and 51.5 Hz; if the frequency falls below the lower limit, a load shedding protection mechanism will be triggered. It is important to note that the power system operates in an isolated mode without large grid interconnection support and has a high proportion of renewable energy integration. Therefore, a broader frequency range is set to ensure that the system has greater flexibility to adjust during disturbances and avoid prolonged frequency deviation from the normal range, which could lead to system instability.

To reveal the system frequency response characteristics under different diesel generator output ratios, scenarios 2 and 3 were selected for analysis. Although both scenarios operate under relatively weak rotating reserve capacity, there is a significant difference in the output share of the diesel generators in the total load, reflecting different typical cases of synchronous generation support capability. Additionally, since this paper focuses on evaluating the dynamic regulation performance of the battery energy storage system in primary frequency control, the simulation does not include secondary frequency regulation mechanisms. The default control parameters of the virtual synchronous generator are set according to reference [

22], with specific values listed in

Table 4. The virtual inertia (

H) and virtual damping (

D) are the tuning parameters, with no default values set.

3.2. Disturbance Scenario 1: Generator Disconnection

The simulation for this condition assumes the sudden disconnection of Diesel Generator 1 after the system stabilizes (given:

), resulting in a 12 MW power loss in scenario 2 and a 10.5 MW power loss in scenario 3. To analyze the impact of VSM control parameters on frequency response, virtual damping (

D) is first fixed at 20 pu, and the effect of virtual inertia on the synthesized frequency of the VSM is examined. The simulation results are shown in

Figure 7a,b. Under three different inertia settings, the system stabilization time in scenario 2 is less than 1 s, and, in scenario 3, it is less than 2 s, both achieving rapid stabilization. A larger virtual inertia can suppress the frequency fluctuation range. With a larger inertia

, the frequency fluctuation widths for the two scenarios are 8 Hz and 5 Hz, significantly smaller than the other two inertia settings. Next, with virtual inertia (

H) fixed at 1 s, the effect of virtual damping on frequency is analyzed, as shown in

Figure 7c,d. Under three different damping settings, the system stabilization time in both scenario 2 and scenario 3 is less than 2 s. The analysis indicates that virtual damping mainly affects the frequency decay process, with higher virtual damping helping to increase the lowest frequency point. With high damping

, the system frequency is approximately 0.4 Hz higher compared to the lower damping setting.

3.3. Disturbance Scenario 2: Three-Phase Symmetrical Short-Circuit Fault

In this scenario, a three-phase symmetrical short-circuit fault occurs at the given time

, located on the transmission line connecting buses B7 and B8, as shown in

Figure 5. The fault is cleared after 200 milliseconds, followed by the permanent disconnection of the affected line. First, the virtual damping coefficient (

D) is fixed at 20 pu to analyze the effect of varying virtual inertia on the synthesized frequency response of the VSM. The corresponding results are presented in

Figure 8a,b. Next, the virtual inertia (

H) is fixed at 0.1 s to investigate the influence of virtual damping on frequency response, with results shown in

Figure 8b,d. Under both scenario 2 and scenario 3, the frequency response evolution exhibits a generally consistent trend.

The results indicate that during the short-circuit fault, variations in virtual inertia have limited impact on the frequency response. This is attributed to the significantly reduced residual voltage in the system, which causes the VSM to promptly activate current limiting, thereby preventing the inertia control from taking effect. After the fault is cleared, the frequency response is significantly sensitive to the inertia setting. Low inertia facilitates quick frequency recovery, with the system stabilization time in both scenarios being less than 2 s. On the other hand, high inertia induces noticeable oscillations. This is due to the fact that, although high inertia suppresses the rate of frequency change, it also delays frequency restoration. Similarly, virtual damping has minimal influence on frequency response during the initial fault period. After the fault is cleared, the frequency stabilizes within 2 s, but the frequency response shows significant differences based on the damping setting. Under low damping , the VSM-synthesized frequency rises rapidly with large amplitude, whereas high damping effectively suppresses such fluctuations. These results suggest that virtual damping begins to play a significant role once voltage recovery occurs. Although lower damping helps reduce the active power surge between the VSM and diesel generator, it also weakens the system’s frequency stability.

To further evaluate the impact of control parameters on system response, the variation in rotor angle difference between the diesel generator and the VSM under different control parameter settings is analyzed, with results shown in

Figure 9. Taking scenario 2 as an example, after the fault is cleared, a smaller inertia setting

leads to a rapid stabilization of the angle difference, while a larger inertia setting

induces pronounced oscillations. The effect of virtual damping follows a similar pattern: low damping

results in severe angle fluctuations, whereas high damping

effectively suppresses such oscillations and facilitates faster resynchronization of the system. In summary, although the influence of virtual inertia and damping is limited during the fault period, these parameters significantly determine the angle response characteristics after voltage recovery. The proper tuning of control parameters can help suppress angle oscillations, reduce the risk of loss of synchronism, and enhance system synchronization stability.

5. Adaptive Switching Strategy for Control Parameters

To enhance the control performance of VSMs under typical disturbances, this paper proposes a rule-based adaptive switching strategy for control parameters. This strategy enables the automatic adjustment of the VSM’s virtual inertia and damping parameters in response to changes in system operating conditions, thereby improving the responsiveness to frequency disturbances. The preceding analysis has shown that control parameters significantly influence system frequency behavior under different types of disturbances, and the optimal configuration is highly dependent on fault characteristics, system synchronous inertia, and voltage dynamics. Using fixed parameter settings may lead to degraded frequency regulation performance and even trigger operational risks such as frequency limit violations. To avoid this issue, specific thresholds are set to enable smooth switching between different modes, thereby enhancing the system’s stability and recovery capability.

In the proposed strategy, system operating conditions are classified into two modes: normal mode and fault mode. Based on real-time measurements of converter terminal voltage, grid frequency, and voltage recovery time, the current operating mode is identified, and the control system switches between two corresponding sets of control parameters. During fault detection, measurement noise or transient fluctuations may occur. To prevent false triggering, Kalman filtering or rate-of-change-based identification strategies can be employed.

As illustrated in

Figure 11, the design logic of the rule-based mechanism can be summarized as follows. (1) When the voltage drops below the threshold, the system is identified as being subject to a severe disturbance; it immediately switches to the fault mode, where the low-inertia and high-damping settings are employed to rapidly suppress voltage and frequency decline. (2) Once the voltage recovers above the threshold and remains stable for a certain duration, or when the system frequency falls below the prescribed limit, the control is switched back to the normal mode (high inertia and low damping), thereby avoiding excessive oscillations caused by frequent parameter switching. The control logic is defined as

Here, the subscripts N and F represent the normal mode and fault mode, respectively; V denotes the measured converter terminal voltage, f is the system frequency, and is the voltage recovery time. The control rule parameters include , , and , which correspond to the voltage threshold, the lower frequency limit, and the maximum allowable voltage recovery time, respectively. According to system operating requirements, the frequency threshold is set to 48.5 Hz.

5.1. Tuning of Control Rule Parameters

The fault mode is defined as a three-phase short-circuit fault occurring between buses B1 and B2, which is cleared after 200 ms. Various fault resistance values are considered to reflect different levels of residual voltage. The control parameters are based on the optimal results obtained from the aggregated scenario: the configuration is applied in the normal mode, while the configuration is used in the fault mode. By comparing system frequency stability and the regulation behavior of the energy storage system under different conditions, appropriate values for the control rule parameters—voltage threshold and voltage recovery time limit —are determined.

Figure 12c,d show that, under normal mode control, the minimum terminal voltage is approximately 0.38 pu when using the parameter

, while it remains above 0.4 pu when using the parameter

. Combined with the frequency response in

Figure 9a, it can be seen that applying fault-mode parameters under the condition

would lead to intensified frequency fluctuations or even violations of frequency limits. Therefore, a voltage threshold

is defined as the boundary criterion for mode switching. The voltage threshold has a significant impact on the frequency response. If the voltage recovery is slow or exceeds the set threshold, it may lead to excessive frequency fluctuations, thus affecting system stability. When the voltage recovery is delayed, the system cannot switch back to normal mode in time, which increases the recovery time and delays frequency stabilization.

Figure 12 also shows that, under all three fault resistance conditions, the voltage recovers to 0.9 pu within 0.2 s. However, if the control parameters are immediately switched back to normal mode, the abrupt change in inertia may induce unnecessary frequency oscillations and increase the regulation burden on the energy storage system. To avoid false switching and power surges, a minimum voltage recovery holding time

is defined as a delay condition for switching from fault mode back to normal mode, ensuring a stable system transition. This delay helps to ensure a smooth transition, preventing system oscillations or unstable responses caused by frequent switching.

5.2. Performance Comparison

To verify the effectiveness of the proposed adaptive control parameter switching strategy, a three-phase symmetrical short-circuit fault lasting 200 milliseconds is applied at bus B6. After the fault is cleared, the associated wind power station is disconnected. This disturbance combination simulates the coupled impact of a sudden voltage drop and generation loss, aiming to assess the strategy’s capability to maintain frequency stability. Three operating conditions are established to compare the performance of the proposed strategy with conventional strategies: (1) Operating condition 1 uses the normal mode parameters, i.e., the parameter tuning strategy without considering disturbances, as in reference [

34]; (2) Operating condition 2 uses fixed fault mode parameters, i.e., the conventional non-adaptive parameter tuning strategy, as in reference [

23]; (3) Operating condition 3 applies the proposed adaptive control parameter switching strategy. Scenario 2, characterized by the lowest synchronous inertia and minimal spinning reserve, is selected for system frequency simulation analysis. The results are shown in

Figure 13.

The results show significant differences in system frequency response across the three operating conditions. In operating condition 1, the system maintains high inertia throughout the process, leading to excessive inertia injection during the fault period, which results in increased frequency oscillations, preventing convergence within 2 s. In operating condition 2, the system stability time is less than 2 s, but, due to insufficient inertia, the frequency drop reaches 47.6 Hz, exceeding the frequency safety limit. In contrast, operating condition 3 employs low inertia and high damping parameters during the initial fault period to mitigate the frequency drop and achieve a smooth transition within 0.5 s.

After voltage recovery, the system switches promptly to the normal mode, enabling rapid frequency restoration and stabilization above 48.5 Hz, within the allowable operating range. In summary, the proposed adaptive switching strategy for control parameters effectively balances frequency stability and response speed, while also reducing the regulation burden on the battery energy storage system, demonstrating strong adaptability and practical engineering applicability.

6. Conclusions

This paper proposes a VSM control parameter tuning and adaptive switching strategy to improve the frequency regulation performance of grid-forming energy storage systems under multiple disturbance conditions. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows. First, based on the grid-forming control structure, a comprehensive control model is established, covering virtual inertia, virtual damping, droop control, and transient virtual impedance. Second, an optimization model for parameter tuning is developed for two typical disturbances: generator disconnection and three-phase symmetrical short-circuit faults, specifying the optimal configurations of virtual inertia and damping under different operating conditions. Lastly, a rule-based adaptive control parameter switching strategy is proposed, integrating multi-disturbance aggregation scenario-based parameter tuning and real-time state recognition based on voltage/frequency criteria into a control framework.

This method is applied to control parameter tuning and operational state simulation of a specific isolated microgrid system, leading to the following key conclusions. (1) The performance of the grid-forming energy storage system in frequency regulation tasks in an isolated grid is highly dependent on the virtual synchronous generator (VSG) parameter settings. In the case of a sudden disconnection of a large-capacity generation unit, a larger virtual inertia (e.g., greater than 15 pu) should be selected to enhance the frequency support capability. In the case of a three-phase symmetrical short-circuit fault, low inertia (e.g., 0.1 s) and high damping (e.g., 50 pu) parameters should be used to suppress oscillations and ensure transient stability. (2) The joint tuning of parameters for multiple operating conditions can effectively improve the applicability of the control strategy. Compared to single-scenario parameter optimization, the aggregated scenario parameter tuning results exhibit good frequency maintenance capability across all scenarios, significantly improving the consistency of system operation state control and the engineering feasibility. (3) The rule-based adaptive control parameter switching strategy significantly improves the system’s dynamic response performance. By judging the system state through port voltage, frequency, and recovery time, it automatically switches the VSG control mode, effectively balancing adjustment speed, frequency stability, and energy storage power burden, demonstrating excellent dynamic adaptability. The voltage threshold is set to 0.4 pu, and the recovery time is set to 2 s, ensuring that the system frequency can recover to the specified range within 1 s under short-circuit disturbances.

The limitation of the proposed method lies in the reliance on simulation-based analysis and offline tuning for rule parameter selection, which lacks adaptability to stochastic uncertainties and variations in network topology. Future research may focus on online parameter identification, the optimization of intelligent switching logic, and the development of multi-source integrated regulation mechanisms to further enhance the applicability of grid-forming energy storage system control in complex power system environments.