Lab-Scale Performance Evaluation of CaCl2/MgCl2/Silica Gel Sorbent Material for Thermal Energy Storage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. CaCl2/MgCl2/Silica Gel Sorbent Materials Preparation

2.2. Sorbent Materials Morphological and Textural Characterisation

2.3. Thermochemical Behaviour Assessment

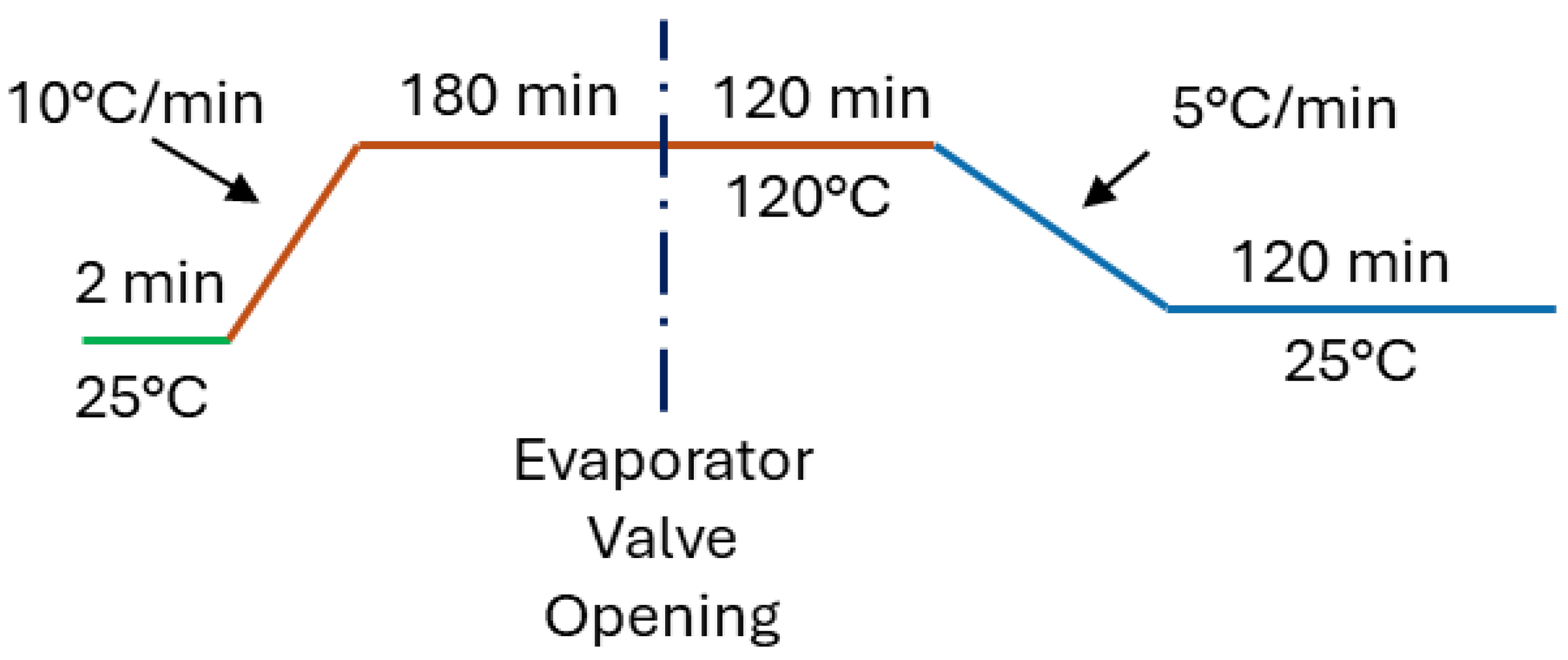

2.4. Lab-Scale Sorption/Desorption Apparatus and Experimental

3. Results

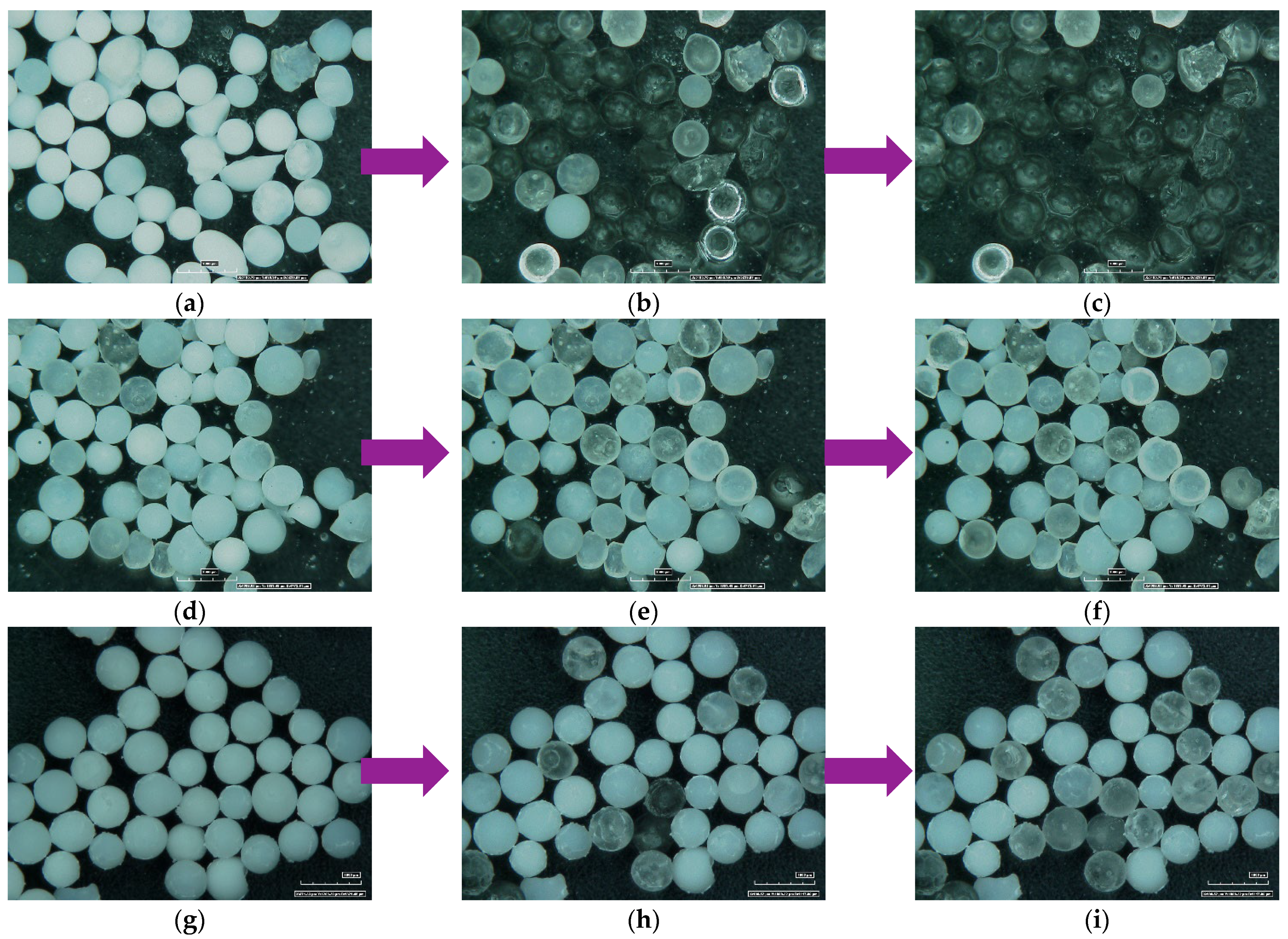

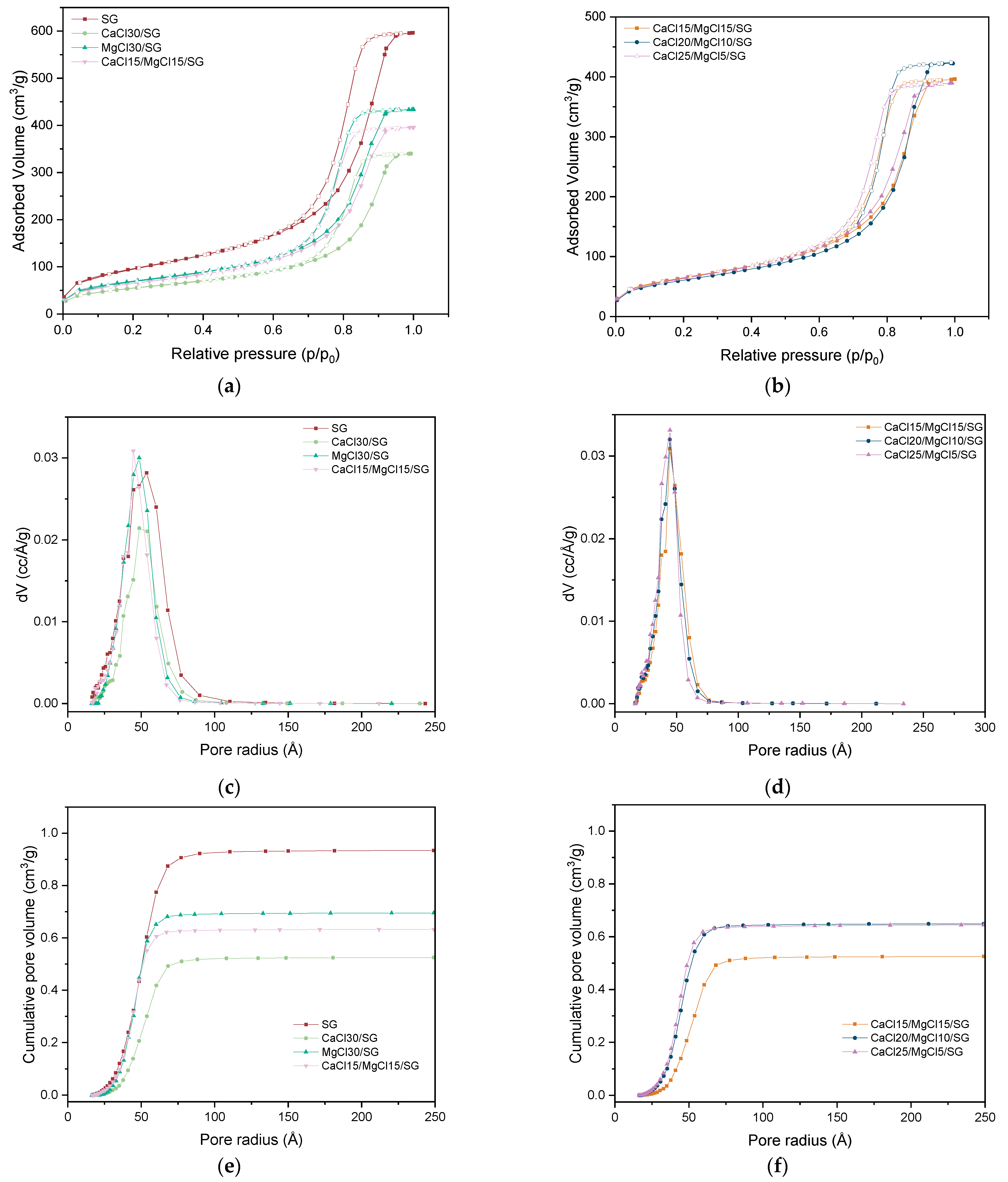

3.1. Sorbent Materials Preparation, Morphological and Textural Analysis

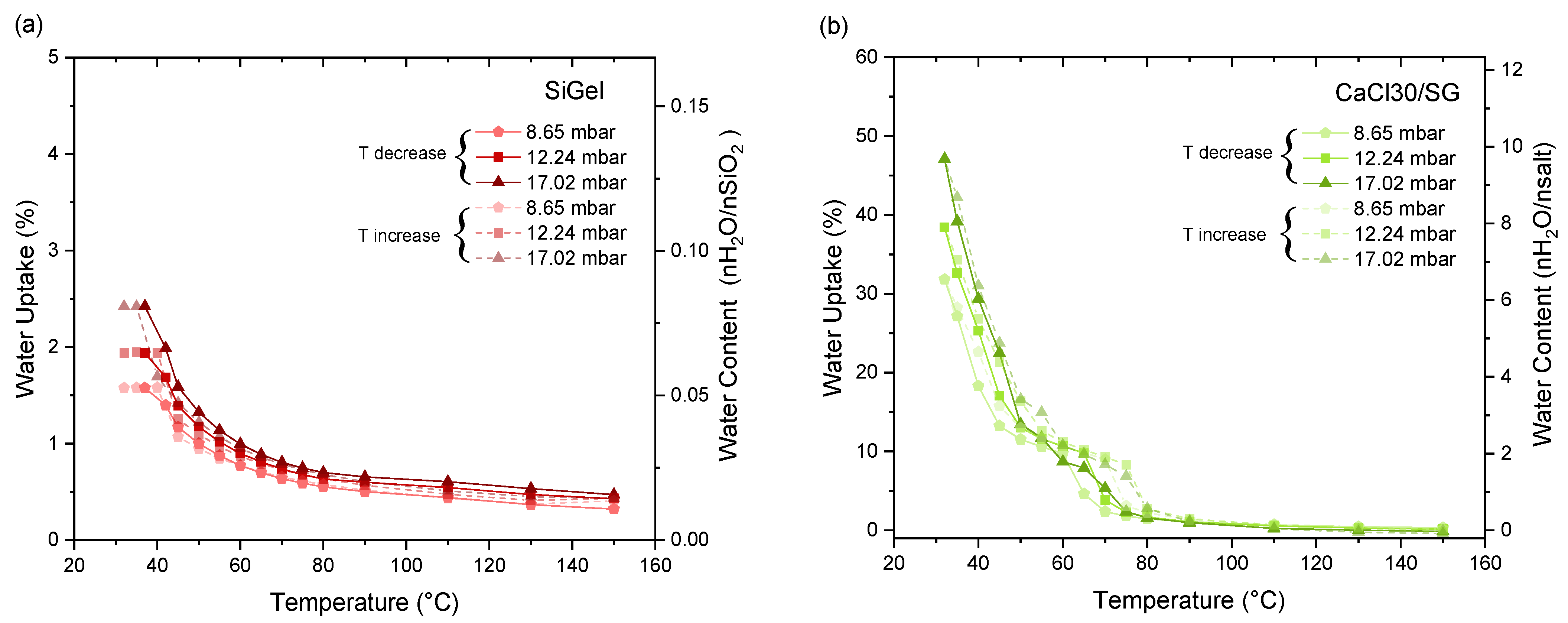

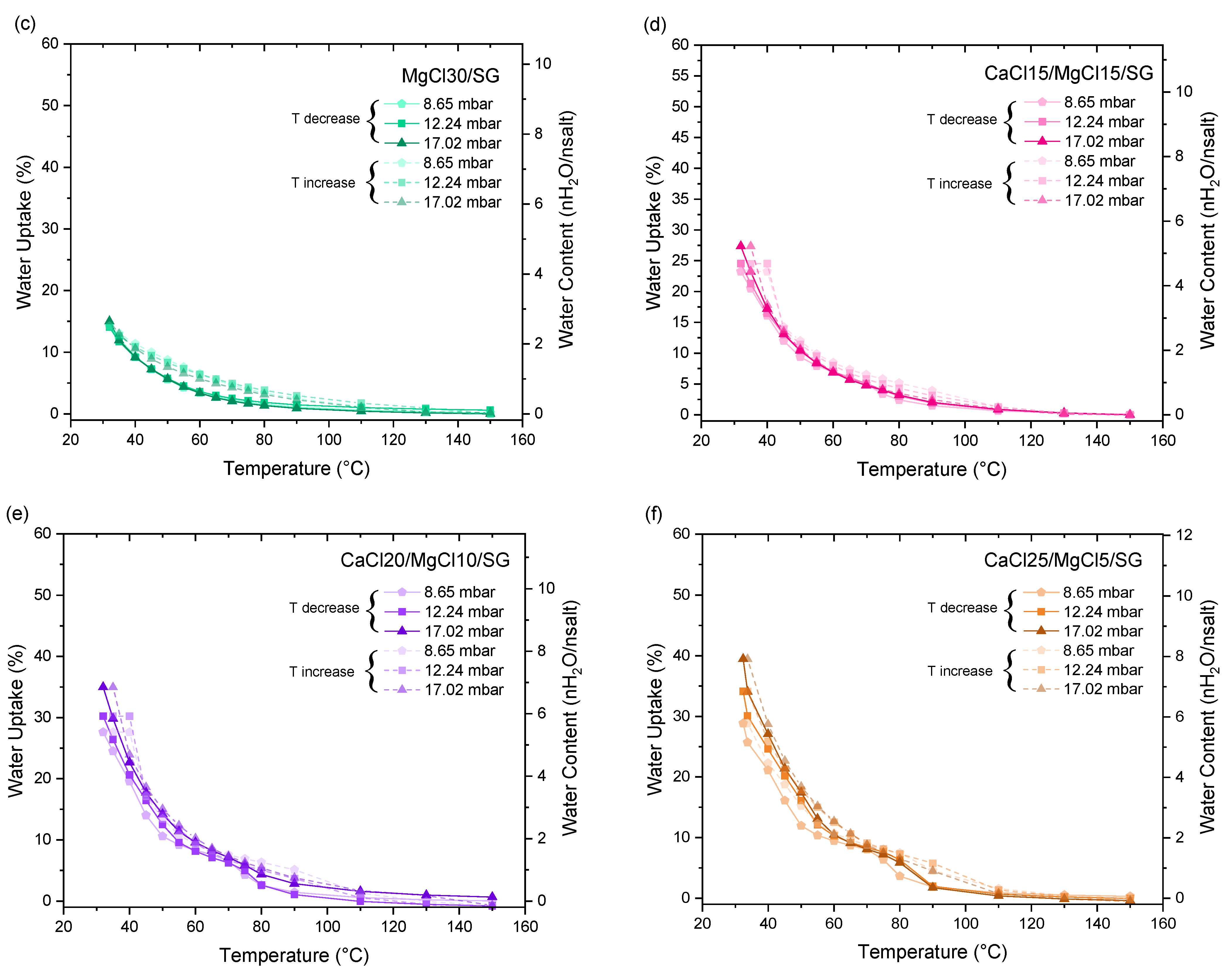

3.2. Thermochemical Performance Evaluation

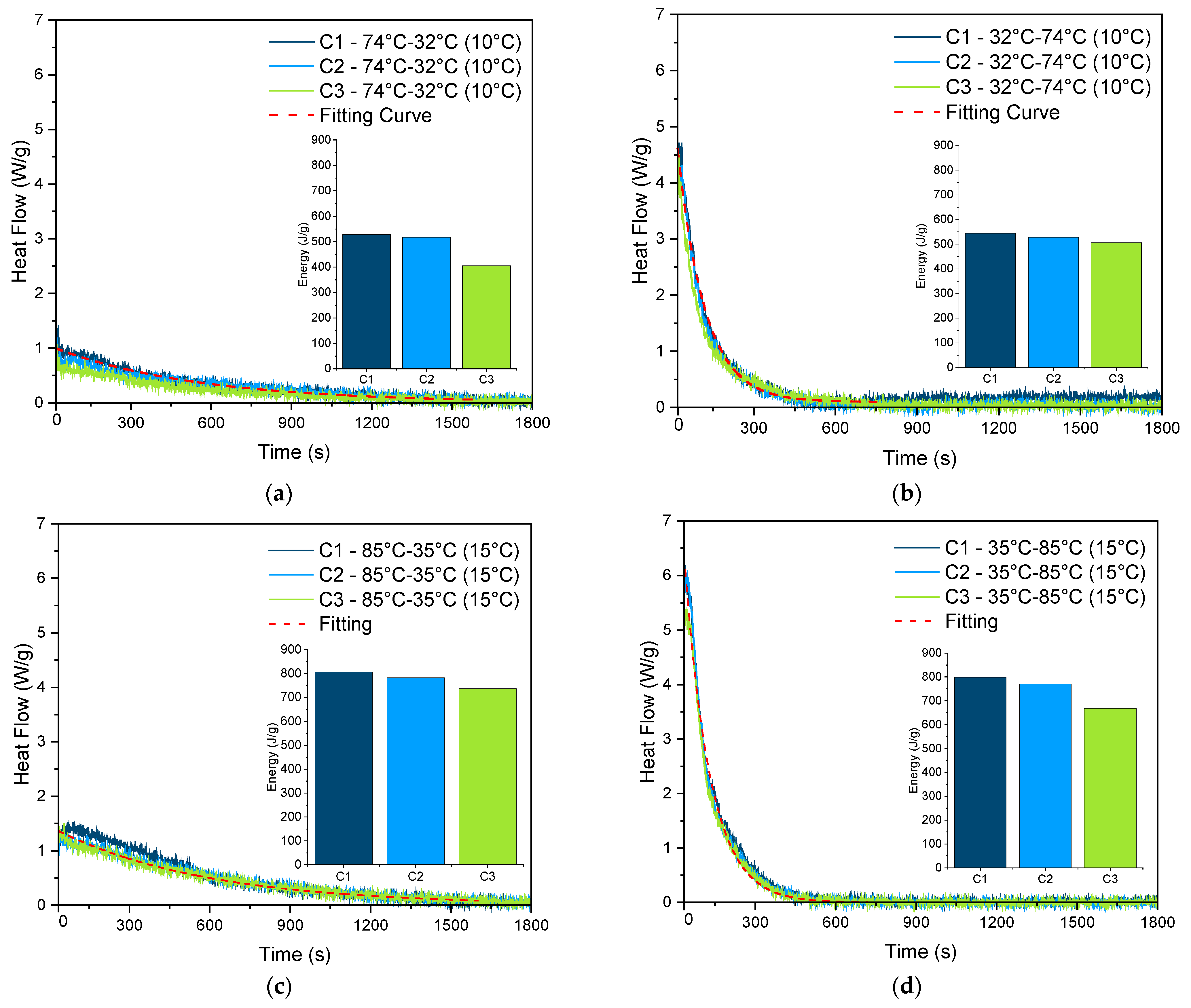

3.3. Lab-Scale Adsorption/Desorption Analysis

3.4. Relevance of the Achieved Results

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trausel, F.; De Jong, A.J.; Cuypers, R. A Review on the Properties of Salt Hydrates for Thermochemical Storage. Energy Procedia 2014, 48, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farulla, G.A.; Cellura, M.; Guarino, F.; Ferraro, M. A Review of Thermochemical Energy Storage Systems for Power Grid Support. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spietz, T.; Fryza, R.; Lasek, J.; Zuwała, J. Thermochemical Energy Storage Based on Salt Hydrates: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2025, 18, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, C.; Tong, L.; Yin, S.; Wang, L.; Ding, Y. Salt Hydrate Adsorption Material-Based Thermochemical Energy Storage for Space Heating Application: A Review. Energies 2023, 16, 2875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarimi, H.; Aydin, D.; Yanan, Z.; Ozankaya, G.; Chen, X.; Riffat, S. Review on the Recent Progress of Thermochemical Materials and Processes for Solar Thermal Energy Storage and Industrial Waste Heat Recovery. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2019, 14, 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbair, M.; Bennici, S. Survey Summary on Salts Hydrates and Composites Used in Thermochemical Sorption Heat Storage: A Review. Energies 2021, 14, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, J.; Fischer, H.; Adan, O.; Huinink, H. Towards Stable Performance of Salt Hydrates in Thermochemical Energy Storage: A Review. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Hirschey, J.; LaClair, T.J.; Gluesenkamp, K.R.; Graham, S. Review of Stability and Thermal Conductivity Enhancements for Salt Hydrates. J. Energy Storage 2019, 24, 100794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ousaleh, H.A.; Said, S.; Zaki, A.; Faik, A.; El Bouari, A. Silica Gel/Inorganic Salts Composites for Thermochemical Heat Storage: Improvement of Energy Storage Density and Assessment of Cycling Stability. In Materials Today: Proceedings; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 30, pp. 937–941. [Google Scholar]

- Fotia, A.; Brancato, V.; Mastronardo, E.; Calabrese, L.; Frazzica, A. Enhancement of CaCl2/Silica Gel Composites Sorbent Stability for Low-Grade Thermal Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage 2025, 132, 117679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbari-Hichri, A.; Bennici, S.; Auroux, A. Enhancing the Heat Storage Density of Silica–Alumina by Addition of Hygroscopic Salts (CaCl2, Ba(OH)2, and LiNO3). Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2015, 140, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Liu, X.; Yang, F.; Guan, L.; Sani, S.; Sun, C.; Wu, Y. Development of MgSO4 /Mesoporous Silica Composites for Thermochemical Energy Storage: The Role of Porous Structure on Water Adsorption. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 4913–4921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, O.; Coutiño-Gonzalez, E.; Grandjean, D.; Baekelant, W.; Richard, F.; Bonacchi, S.; De Vos, D.; Lievens, P.; Roeffaers, M.; Hofkens, J.; et al. Tuning the Energetics and Tailoring the Optical Properties of Silver Clusters Confined in Zeolites. Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongois, S.; Kuznik, F.; Stevens, P.; Roux, J.-J. Development and Characterisation of a New MgSO4−zeolite Composite for Long-Term Thermal Energy Storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 1831–1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, G.; Grondin, D.; Bennici, S.; Auroux, A. Heats of Water Sorption Studies on Zeolite–MgSO4 Composites as Potential Thermochemical Heat Storage Materials. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2013, 112, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, S.P.; Elvins, J.; Riffat, S.; Robinson, A. Salt Impregnated Desiccant Matrices for ‘Open’ Thermochemical Energy Storage—Selection, Synthesis and Characterisation of Candidate Materials. Energy Build. 2014, 84, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Deng, L. Development of Lithium Hydroxide-Metal Organic Framework-Derived Porous Carbon Composite Materials for Efficient Low Temperature Thermal Energy Storage. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2021, 328, 111455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zhou, W.; Jin, W. Experimental and Numerical Study on Thermal Energy Storage of Polyethylene Glycol/Expanded Graphite Composite Phase Change Material. Energy Build. 2016, 111, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenobu, T.; Takano, T.; Shiraishi, M.; Murakami, Y.; Ata, M.; Kataura, H.; Achiba, Y.; Iwasa, Y. Stable and Controlled Amphoteric Doping by Encapsulation of Organic Molecules inside Carbon Nanotubes. Nat. Mater. 2003, 2, 683–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, G.; Hong, G.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, X. Graphene Aerogel Templated Fabrication of Phase Change Microspheres as Thermal Buffers in Microelectronic Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 41323–41331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, A.J.; González-Aguilar, J.; Romero, M.; Coronado, J.M. Solar Energy on Demand: A Review on High Temperature Thermochemical Heat Storage Systems and Materials. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 4777–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Tan, B.; Liang, X.; Wang, S.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Fang, Y. Investigation on Water Vapor Adsorption Performance of LiCl@MIL-100(Fe) Composite Adsorbent for Adsorption Heat Pumps. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 44, 5895–5904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padamurthy, A.; Nandanavanam, J.; Rajagopalan, P. Preparation and Characterization of Metal Organic Framework Based Composite Materials for Thermochemical Energy Storage Applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2022, 11, 100309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touloumet, Q.; Postole, G.; Silvester, L.; Bois, L.; Auroux, A. Hierarchical Aluminum Fumarate Metal-Organic Framework—Alumina Host Matrix: Design and Application to CaCl2 Composites for Thermochemical Heat Storage. J. Energy Storage 2022, 50, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Aftab, W.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Y. Form-Stable Metal Ion Coordination Organic Sorbent Aerogel and Its Application in Low Temperature Microwave-Powered Sorption Thermochemical Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhao, Q.; Huang, H.; Mao, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, Y. Applications of Low-Temperature Thermochemical Energy Storage Systems for Salt Hydrates Based on Material Classification: A Review. Sol. Energy 2021, 214, 149–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammelberg, H.U.; Osterland, T.; Priehs, B.; Opel, O.; Ruck, W.K.L. Thermochemical Heat Storage Materials—Performance of Mixed Salt Hydrates. Sol. Energy 2016, 136, 571–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammelberg, H.; Myrau, M.; Osterland, T.; L Ruck, W.K.; Rammelberg, H.U.; Schmidt, T.; Ruck, W. An Optimization of Salt Hydrates for Thermochemical Heat Storae. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 30, 937–941. [Google Scholar]

- Ejeian, M.; Entezari, A.; Wang, R.Z. Solar Powered Atmospheric Water Harvesting with Enhanced LiCl /MgSO4/ACF Composite. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 176, 115396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordeeva, L.G.; Grekova, A.D.; Krieger, T.A.; Aristov, Y.I. Adsorption Properties of Composite Materials (LiCl + LiBr)/Silica. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2009, 126, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posern, K.; Kaps, C. Calorimetric Studies of Thermochemical Heat Storage Materials Based on Mixtures of MgSO4 and MgCl2. Thermochim. Acta 2010, 502, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, A.; Miró, L.; Barreneche, C.; Martorell, I.; Cabeza, L.F. Corrosion of Metals and Salt Hydrates Used for Thermochemical Energy Storage. Renew Energy 2015, 75, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, E.; Menon, A.K. Thermochemical energy storage using salt mixtures with improved hydration kinetics and cycling stability. J. Energy Storage 2024, 90, 111916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamara, D.; Palomba, V.; Calabrese, L.; Frazzica, A. Evaluation of Ad/Desorption Dynamics of S-PEEK/Zeolite Composite Coatings by T-LTJ Method. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 208, 118262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Gu, W.; Peng, C.; Wang, W.; Jie Li, Y.; Zong, T.; Tang, Y.; Wu, Z.; Lin, Q.; Ge, M.; et al. A Comprehensive Study of Hygroscopic Properties of Calcium-and Magnesium-Containing Salts: Implication for Hygroscopicity of Mineral Dust and Sea Salt Aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 2115–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancato, V.; Gordeeva, L.G.; Sapienza, A.; Palomba, V.; Vasta, S.; Grekova, A.D.; Frazzica, A.; Aristov, Y.I. Experimental Characterization of the LiCl/Vermiculite Composite for Sorption Heat Storage Applications. Int. J. Refrig. 2019, 105, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Palamara, D.; Palomba, V.; Calabrese, L.; Frazzica, A. Performance Analysis of a Lab-Scale Adsorption Desalination System Using Silica Gel/LiCl Composite. Desalination 2023, 548, 116278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancato, V.; Gordeeva, L.G.; Grekova, A.D.; Sapienza, A.; Vasta, S.; Frazzica, A.; Aristov, Y.I. Water Adsorption Equilibrium and Dynamics of LICL/MWCNT/PVA Composite for Adsorptive Heat Storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2019, 193, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamara, D.; Proverbio, E.; Frazzica, A.; Calabrese, L. Investigating Ad/Desorption Kinetics of SAPO-34/Graphite Filled Coatings by T-LTJ for Energy-Efficient Sorption Application. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 281, 128631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition Parameters | Textural Properties | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samples | Salt1 | Salt2 | Mass Ratio Salts:Composite | Mass Ratio Salt1:Salt 2 | Specific Surface Area [m3/g] | Pore Volume [cm3/g] | Pore Radius [Å] | Density [g/cm3] |

| SG | - | - | - | - | 386.30 | 1.049 | 44.843 | 2.210 |

| CaCl30/SG | CaCl2 | - | 0.30 | - | 197.88 | 0.554 | 48.675 | 2.116 |

| MgCl30/SG | - | MgCl2 | 0.30 | - | 242.84 | 0.695 | 48.620 | 2.156 |

| CaCl15/MgCl15/SG | CaCl2 | MgCl2 | 0.30 | 1:1 | 226.18 | 0.632 | 44.560 | 2.103 |

| CaCl20/MgCl10/SG | CaCl2 | MgCl2 | 0.30 | 2:1 | 228.32 | 0.648 | 44.422 | 2.099 |

| CaCl25/MgCl5/SG | CaCl2 | MgCl2 | 0.30 | 5:1 | 215.34 | 0.635 | 44.653 | 2.210 |

| Samples | [J/g] | [kWh/kg] | [MJ/m3] | [kWh/m3] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiGel | 193.31 | 0.053 | 0.427 | 0.118 |

| CaCl30/SG | 1315.98 | 0.365 | 2.785 | 0.773 |

| MgCl30/SG | 766.33 | 0.212 | 1.652 | 0.458 |

| CaCl15MgCl15/SG | 1091.95 | 0.303 | 2.296 | 0.637 |

| CaCl20MgCl10/SG | 1089.78 | 0.302 | 2.287 | 0.635 |

| CaCl25MgCl5/SG | 1172.482 | 0.032 | 2.591 | 0.719 |

| Conditions | [∆T]∞ | [∆T]0 | τ (s) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 74–32–Tev = 10 | 0 | 1.03 | 542.57 ± 2.49 | 0.958 |

| 32–74–Tcon = 10 | 0.1 | 5.5 | 100.52 ± 0.37 | 0.991 |

| 85–35–Tev = 15 | 0 | 1.45 | 562.54 ± 2.83 | 0.947 |

| 35–85–Tcon = 15 | 0 | 9.2 | 95.65 ± 0.54 | 0.977 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Prestipino, M.; Fotia, A.; Avila-Gutierrez, M.A.; Calabrese, L.; Frazzica, A.; Milone, C.; Mastronardo, E. Lab-Scale Performance Evaluation of CaCl2/MgCl2/Silica Gel Sorbent Material for Thermal Energy Storage. Energies 2025, 18, 6527. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246527

Prestipino M, Fotia A, Avila-Gutierrez MA, Calabrese L, Frazzica A, Milone C, Mastronardo E. Lab-Scale Performance Evaluation of CaCl2/MgCl2/Silica Gel Sorbent Material for Thermal Energy Storage. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6527. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246527

Chicago/Turabian StylePrestipino, Mauro, Antonio Fotia, Mario Alberto Avila-Gutierrez, Luigi Calabrese, Andrea Frazzica, Candida Milone, and Emanuela Mastronardo. 2025. "Lab-Scale Performance Evaluation of CaCl2/MgCl2/Silica Gel Sorbent Material for Thermal Energy Storage" Energies 18, no. 24: 6527. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246527

APA StylePrestipino, M., Fotia, A., Avila-Gutierrez, M. A., Calabrese, L., Frazzica, A., Milone, C., & Mastronardo, E. (2025). Lab-Scale Performance Evaluation of CaCl2/MgCl2/Silica Gel Sorbent Material for Thermal Energy Storage. Energies, 18(24), 6527. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246527