Improved Biomethane Potential by Substrate Augmentation in Anaerobic Digestion and Biodigestate Utilization in Meeting Circular Bioeconomy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Collection and Preparation

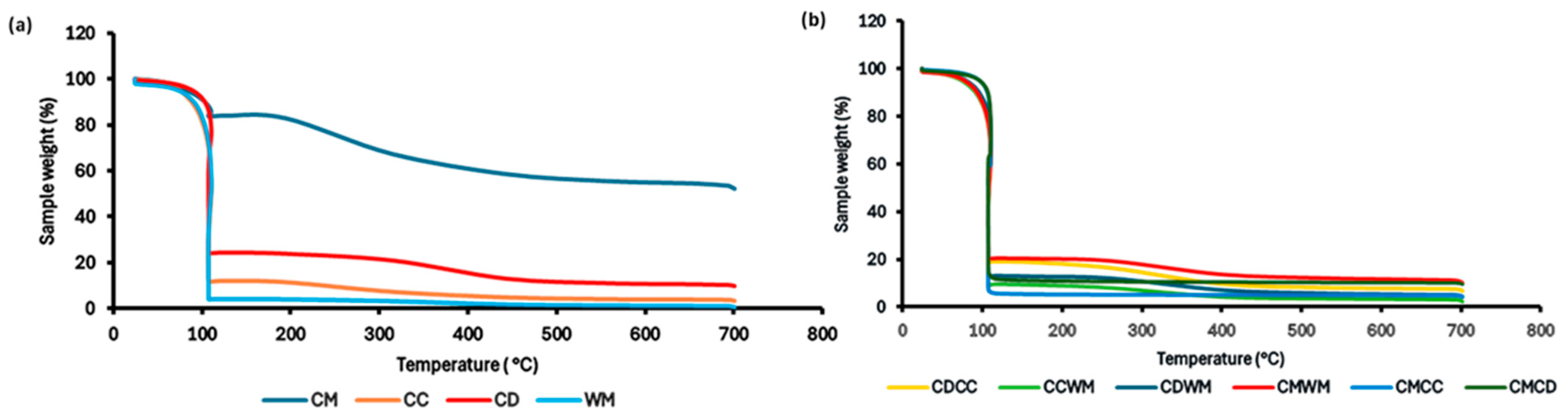

2.2. Substrate Characterization by Proximate Analysis

2.3. Determination of Biomethane Potential by AMPTS

2.4. Biogas Production by Water-Displacement Method

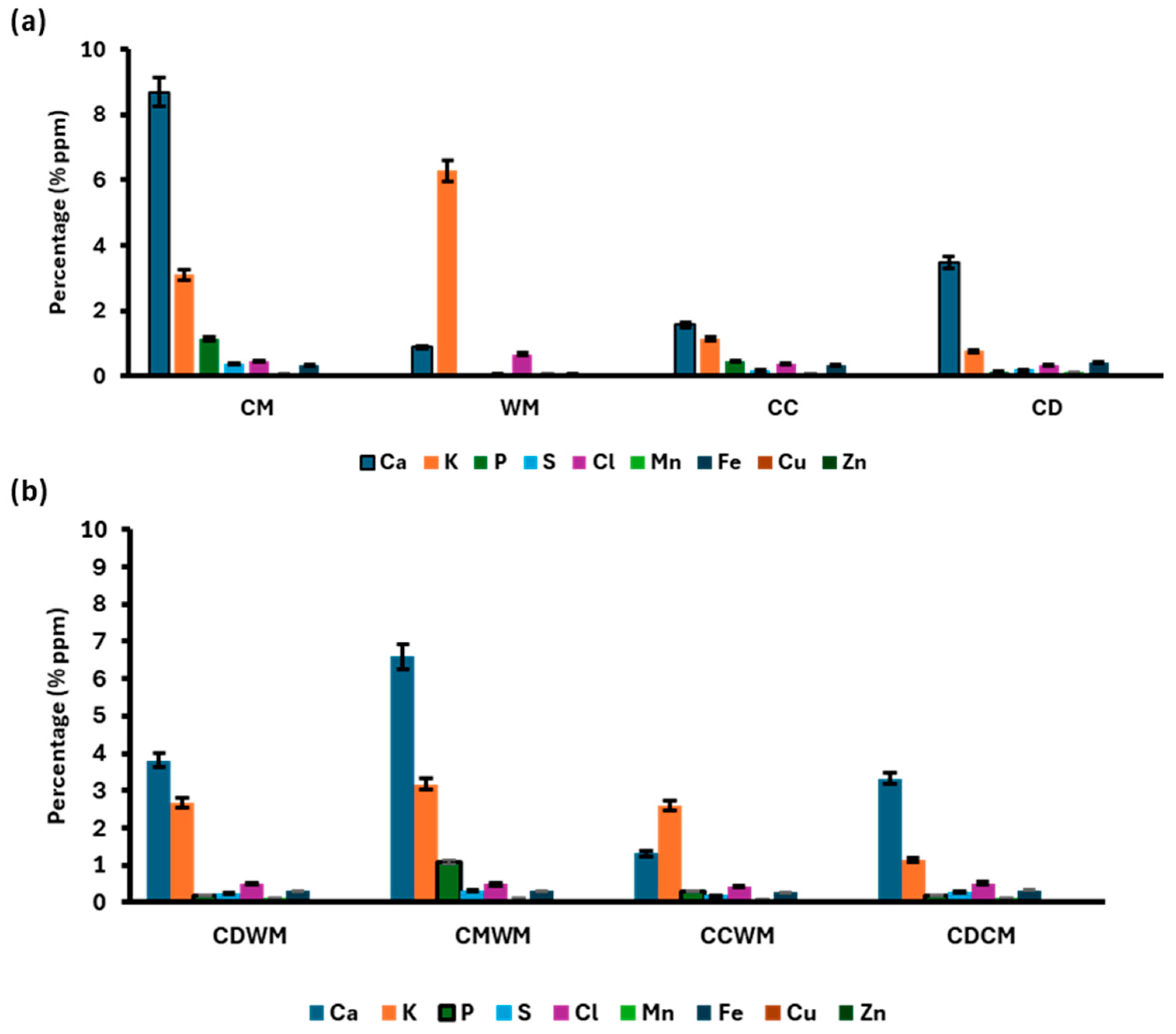

2.5. Elemental Analysis of the Substrates and Biodigestate Using X-Ray Fluorescence

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Proximate Analysis and C:N Analysis of the Used Substrates

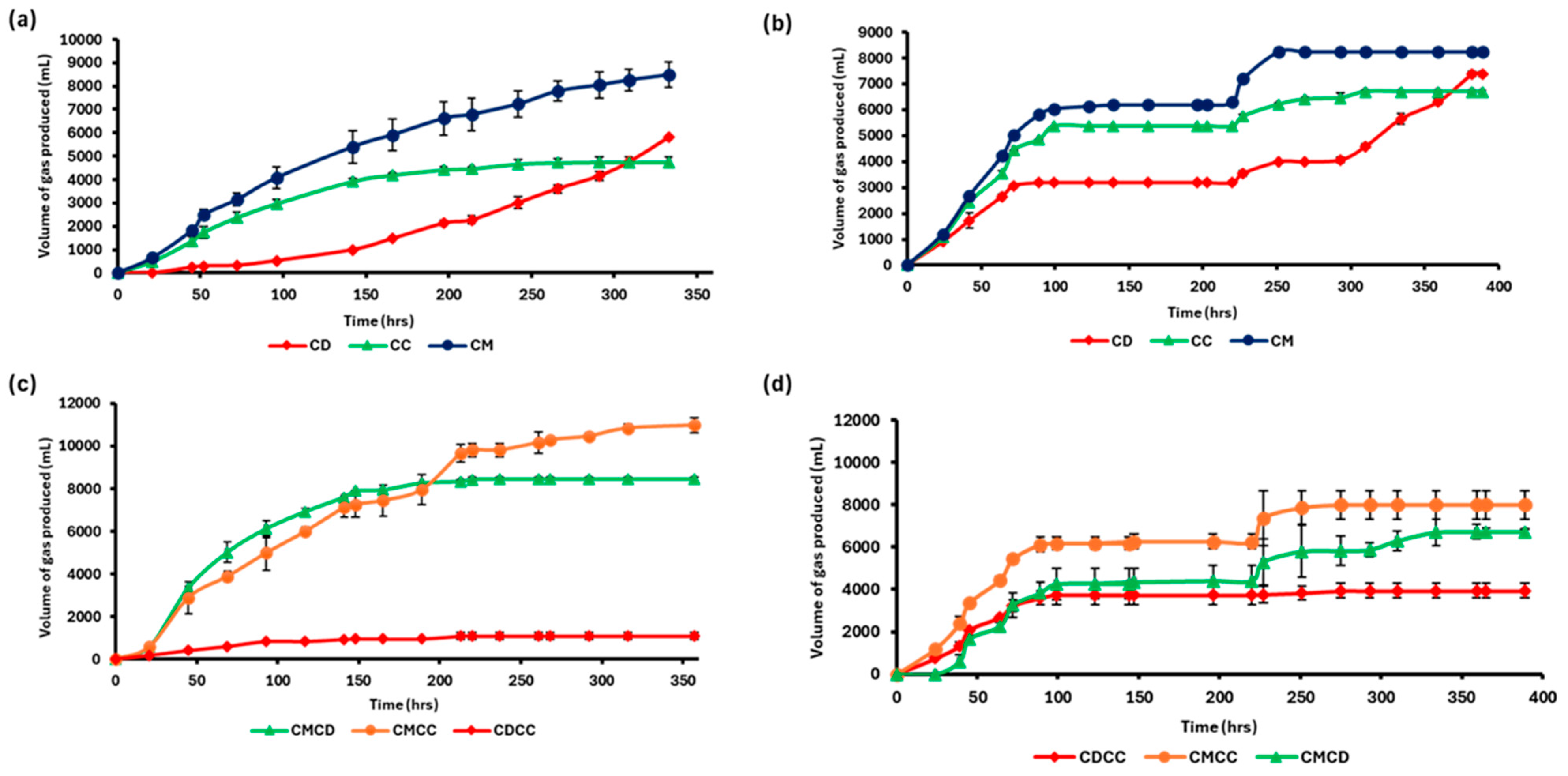

3.2. Biomethane Production Curves from Different Substrates Using AMPTS

3.3. Determination of Biomethane Potential (BMP) of the Different Substrates

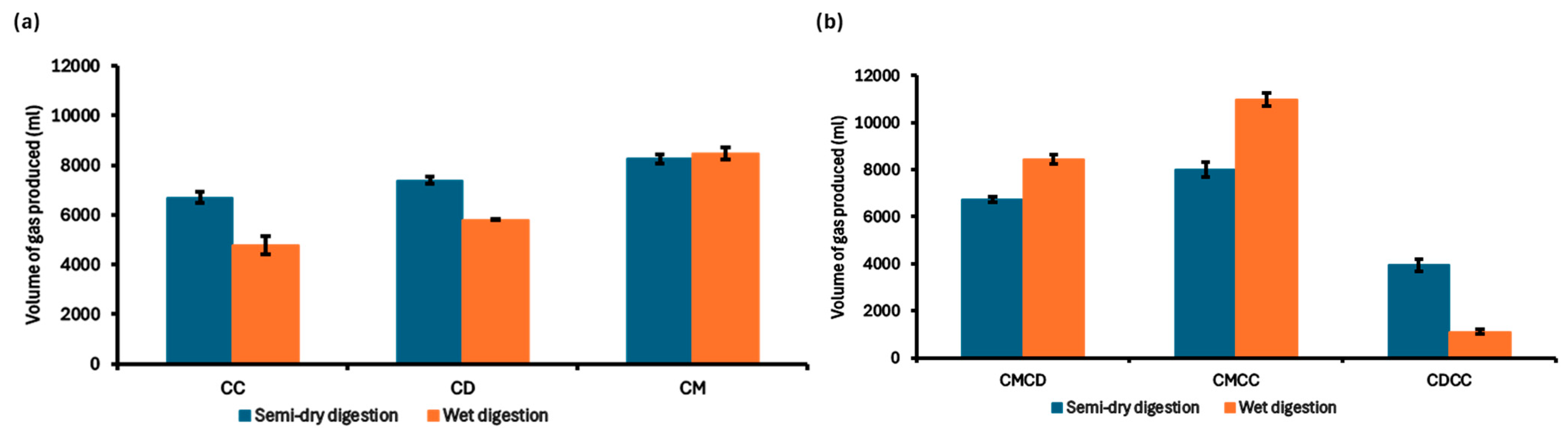

3.4. Biogas Production Using the Water Displacement Method in Wet and Semi-Dry Digestion

3.5. Analysis of Biodigestate Nutrient Composition Using XRF

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dhungana, B.; Lohani, S.P.; Marsolek, M. Anaerobic co-digestion of food waste with livestock manure at ambient temperature: A biogas based circular economy and sustainable development goals. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubańska, A.; Kazak, J.K. The role of biogas production in circular economy approach from the perspective of locality. Energies 2023, 16, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Y.; Yun, S.; Mehmood, A.; Ali Shah, F.; Wang, K.; Eldin, E.T.; Al-Qahtani, W.H.; Ali, S.; Bocchett, P. Co-digestion of cow manure and food waste for biogas enhancement and nutrients revival in bio-circular economy. Chemosphere 2023, 311, 137018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chodkowska-Miszczuk, J.; Martinát, S.; Van Der Horst, D. Changes in feedstocks of rural anaerobic digestion plants: External drivers towards a circular bioeconomy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 148, 111344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrzypczak, D.; Trzaska, K.; Gil, F.; Chawla, Y.; Mikula, K.; Izydorczyk, G.; Samoraj, M.; Tkacz, K.; Turkiewicz, I.; Moustakas, K.; et al. Towards anaerobic digestate valorization to recover fertilizer nutrients: Elaboration of technology and profitability analysis. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 178, 106967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Buhari, M.; Yauri, I.Y. Comparative analysis of biogas production from agricultural wastes. Int. J. Sci. Glob. Sustain. 2024, 10, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ncube, A.; Sadondo, P.; Makhanda, R.; Mabika, C.; Beinisch, N.; Cocker, J.; Gwenzi, W.; Ulgiati, S. Circular bioeconomy potential and challenges within an African context: From theory to practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 367, 133068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appels, L.; Baeyens, J.; Degrève, J.; Dewil, R. Principles and potential of the anaerobic digestion of waste-activated sludge. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2008, 34, 755–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Aryal, N.; Li, Y.; Horn, S.J.; Ward, A.J. Developing a biogas centralised circular bioeconomy using agricultural residues-Challenges and opportunities. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 868, 161656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Mofijur, M.; Uddin, M.N.; Kabir, Z.; Badruddin, I.A.; Khan, T.M.Y. Insights into anaerobic digestion of microalgal biomass for enhanced energy recovery. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1355686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Yan, H.; Xing, S. Research on the control system for the use of biogas slurry as fertilizer. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Baere, L. Anaerobic digestion of solid waste: State-of-the-art. Water Sci. Technol. 2006, 41, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheri, A.N.; Ndiweni, S.N.; Belaid, M.; Muzenda, E.; Hubert, R. Optimising biogas production from anaerobic co-digestion of chicken manure and organic fraction of municipal solid waste. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 756–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Strömberg, S.; Li, C.; Nges, I.A.; Nistor, M.; Deng, L.; Liu, J. Effects of substrate concentration on methane potential and degradation kinetics in batch anaerobic digestion. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 194, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata-Alvarez, J.; Dosta, J.; Romero-Güiza, M.S.; Fonoll, X.; Peces, M.; Astals, S. A critical review on anaerobic co-digestion achievements between 2010 and 2013. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 36, 412–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnürer, A. Biogas Production: Microbiology and Technology. In Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cheng, J.J.; Creamer, K.S. Inhibition of anaerobic digestion process: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 4044–4064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyi-Loh, C.E.; Lues, R. Anaerobic digestion of lignocellulosic biomass: Substrate characteristics (challenge) and innovation. Fermentation 2023, 9, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Ali, A.; Alam, M.Z.; Abdoul-latif, M.F.; Jami, M.S.; Gamiye Bouh, I.; Adebayo Bello, I.; Ainane, T. Production of biogas from food waste using the anaerobic digestion process with biofilm-based pretreatment. Processes 2023, 11, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayyat, U.; Khan, M.U.; Sultan, M.; Zahid, U.; Bhat, S.A.; Muzamil, M. A review on dry anaerobic digestion: Existing technologies, performance factors, challenges, and recommendations. Methane 2024, 3, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sganzerla, W.G.; Costa, J.M.; Tena-Villares, M.; Buller, L.S.; Mussatto, S.I.; Forster-Carneiro, T. Dry anaerobic digestion of brewer’s spent grains toward a more sustainable brewery: Operational performance, kinetic analysis, and bioenergy potential. Fermentation 2022, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, V.; Tumwesige, V.; Smith, J.U. Water for small-scale biogas digesters in sub-Saharan Africa. GCB Bioenergy 2017, 9, 339–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaedi, M.; Nasab, H.; Ehrampoush, M.H.; Ebrahimi, A.A. Evaluation of the efficiency of dry anaerobic digester in the production of biogas and fertilizer using activated sludge and plant waste. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekała, W.; Nowak, M.; Bojarski, W. Characteristics of substrates used for biogas production in terms of water content. Fermentation 2023, 9, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y.; Hu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, G.; Zhan, X. A critical review on dry anaerobic digestion of organic waste: Characteristics, operational conditions, and improvement strategies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 176, 113208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannis, A.; Diamantis, V.; Eftaxias, A.; Stamatelatou, K. Long-Term Anaerobic Digestion of Seasonal Fruit and Vegetable Waste Using a Leach-Bed Reactor Coupled to an Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Bed Reactor. Sustainability 2023, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallaji, S.M.; Kuroshkarim, M.; Moussavi, S.P. Enhancing methane production using anaerobic co-digestion of waste activated sludge with combined fruit waste and cheese whey. BMC Biotechnol. 2019, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oduor, W.W.; Wandera, S.M.; Murunga, S.I.; Raude, J.M. Enhancement of anaerobic digestion by co-digesting food waste and water hyacinth in improving treatment of organic waste and bio-methane recovery. Heliyon 2022, 8, 10580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyoni., K.; Kelebopile, L. Physio-chemical and Thermal Characterization of Demineralized Poultry Litter using Mechanical Sizing Fractioning, Acid Solvents, and Deionized Water. J. Chem. Environ. 2023, 2, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D7582; Standard Test Methods for Proximate Analysis of Coal and Coke by Macro Thermogravimetric Analysis. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Marczewski, P.; Sytek-Szmeichel, K.; Zubrowska-Sudol, M. Assessment of Potential of Organic Waste Methane for Implementation in Energy Self-Sufficient Wastewater Treatment Facilities. Energies 2025, 18, 5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagi, Z.; Ács, N.; Bálint, B.; Horváth, L.; Dobó, K.; Perei, K.R.; Kovács, K.L. Biotechnological intensification of biogas production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 76, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle; Board on Agriculture and Natural Resources; Division on Earth and Life Studies; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle: Eighth Revised Edition; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedwitschka, H.; Gallegos Ibanez, D.; Schäfer, F.; Jenson, E.; Nelles, M. Material characterization and substrate suitability assessment of chicken manure for dry batch anaerobic digestion processes. Bioengineering 2020, 7, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Reimer, C.; Picard, M.; Mohanty, A.K.; Misra, M. Characterization of chicken feather biocarbon for use in sustainable biocomposites. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashekuzzaman, S.M.; Poulsen, T.G. Optimizing feed composition for improved methane yield during anaerobic digestion of cow manure based waste mixtures. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 2213–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diagi, E.A.; Akinyemi, M.L.; Emetere, M.E.; Ogunrinola, I.E.; Ndubuisi, A.O. Comparative Analysis of Biogas Produced from Cow Dung and Poultry Droppings. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 331, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhorhoro, E.K.; Ebunilo, P.O.; Sadjere, G.E. Experimental determination of effect of total solid (TS) and volatile solid (VS) on biogas yield. Am. J. Mod. Energy 2017, 3, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, K.; Chen, X.; Pan, J.; Kloss, R.; Wei, Y.; Ying, Y. Effect of ammonia and nitrate on biogas production from food waste via anaerobic digestion. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 116, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.; Davies, S.; Villa, R.; Gomes, D.M.; Coulon, F.; Wagland, S.T. Compositional analysis of excavated landfill samples and the determination of residual biogas potential of the organic fraction. Waste Manag. 2016, 55, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johari, S.A.M.; Aqsha, A.; Shamsudin, M.R.; Lam, M.K.; Osman, N.; Tijani, M.; Jawaid, M.; Khan, A. (Eds.) Technical trends in biogas production from chicken manure. In Manure Technology and Sustainable Development; Sustainable Materials and Technology; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 145–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmohamadsadeghi, S.; Karimi, K.; Zamani, A.; Amiri, H.; Horváth, I.S. Enhanced Solid-State Biogas Production from Lignocellulosic Biomass by Organosolv Pretreatment. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabii, A.; Aldin, S.; Dahman, Y.; Elbeshbishy, E. A Review on Anaerobic Co-Digestion with a Focus on the Microbial Populations and the Effect of Multi-Stage Digester Configuration. Energies 2019, 12, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surendra, K.C.; Takara, D.; Hashimoto, A.G.; Khanal, S.K. Biogas as a sustainable energy source for developing countries: Opportunities and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 31, 846–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koszel, M.; Przywara, A.; Kachel-Jakubowska, M.; Kraszkiewicz, A. Evaluation of the Use of Biogas Plant Digestate as a Fertilizer in Field Cultivation Plant. In Proceedings of the IX International Scientific Symposium “Farm Machinery and Processes Management in Sustainable Agriculture”, Lublin, Poland, 22–24 November 2017; pp. 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Hua, Y.; Deng, L. Nutrient Status and Contamination Risks from Digested Pig Slurry Applied on a Vegetable Crops Field. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, M.; Dwivedi, V.; Kumar, S.; Patel, A.; Niazi, P.; Yadav, V.K. Lead toxicity in plants: Mechanistic insights into toxicity, physiological responses of plants and mitigation strategies. Plant Signal. Behav. 2024, 19, 2365576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Sanz-Garrido, C.; Revuelta-Aramburu, M.; Santos-Montes, A.M.; Morales-Polo, C. A Review on Anaerobic Digestate as a Biofertilizer: Characteristics, Production, and Environmental Impacts from a Life Cycle Assessment Perspective. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Substrate | Moisture (%) | Volatile Solids (%) | Fixed Carbon (%) | Ash (%) | C:N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 88.14 | 8.55 | 2.01 | 1.31 | 32 |

| CD | 76.03 | 14.54 | 4.08 | 5.36 | 23 |

| CM | 15.72 | 32.66 | 8.85 | 42.77 | 8 |

| WM | 95.78 | 3.66 | 0.2 | 0.36 | 20 |

| CDCC | 81.31 | 12.12 | 3.02 | 3.56 | - |

| CMCD | 67.38 | 19.58 | 5.47 | 7.58 | - |

| CMCC | 75.43 | 15.46 | 4.44 | 4.67 | - |

| CDWM | 87.19 | 8.64 | 1.83 | 2.34 | - |

| CCWM | 90.92 | 7.07 | 1.2 | 0.8 | - |

| CMWM | 79.63 | 10.47 | 2.12 | 7.78 | - |

| Substrate | Substrate Weight (g) | Substrate VS (g VS) | VS Consumed, (%) | Av. Gas Produced (NmL CH4) | BMP (NmL CH4/g VS) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC | 700 | 78.82 | 11.26 | 408.3 | 5.2 |

| CD | 700 | 107.38 | 15.34 | 3166.2 | 29.5 |

| CM | 400 | 94.16 | 23.54 | 2262.6 | 21.9 |

| CDCC | 700 | 43.47 | 6.21 | 954.5 | 17.4 |

| CMCD | 400 | 77.04 | 19.26 | 997.6 | 12.9 |

| CMCC | 400 | 56.48 | 14.12 | 903.45 | 16.0 |

| CDWM | 700 | 32.83 | 4.69 | 265.3 | 8.1 |

| CCWM | 700 | 36.47 | 5.21 | 863.25 | 23.7 |

| CMWM | 400 | 20.24 | 5.06 | 1480.6 | 63.3 |

| BLANK | 0 | - | 0.78 | 199.0 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bontsi, W.; Othusitse, N.; Gessesse, A.; Lebogang, L. Improved Biomethane Potential by Substrate Augmentation in Anaerobic Digestion and Biodigestate Utilization in Meeting Circular Bioeconomy. Energies 2025, 18, 6505. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246505

Bontsi W, Othusitse N, Gessesse A, Lebogang L. Improved Biomethane Potential by Substrate Augmentation in Anaerobic Digestion and Biodigestate Utilization in Meeting Circular Bioeconomy. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6505. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246505

Chicago/Turabian StyleBontsi, Wame, Nhlanhla Othusitse, Amare Gessesse, and Lesedi Lebogang. 2025. "Improved Biomethane Potential by Substrate Augmentation in Anaerobic Digestion and Biodigestate Utilization in Meeting Circular Bioeconomy" Energies 18, no. 24: 6505. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246505

APA StyleBontsi, W., Othusitse, N., Gessesse, A., & Lebogang, L. (2025). Improved Biomethane Potential by Substrate Augmentation in Anaerobic Digestion and Biodigestate Utilization in Meeting Circular Bioeconomy. Energies, 18(24), 6505. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246505