Enhancing Shaft Voltage Mitigation with Diffusion Models: A Comprehensive Review for Industrial Electric Motors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Research Motivation

1.2. Scope and Purpose of the Review

- What are the primary sources and causes of shaft voltage in inverter-fed electric motors, and how do they impact the motor’s reliability and performance?

- What are the existing mitigation strategies for shaft voltage, and how effective are they in reducing bearing failure and improving motor lifespan?

- How can DMs be leveraged to improve the signal processing of shaft voltage, and what are the advantages of DMs over traditional methods such as machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL)?

- What challenges and limitations exist in the application of DMs for shaft voltage analysis, and how can future research address these gaps to improve industrial motor systems?

- Analyzing the shaft voltage and its causes in detail: The review provides a detailed overview of shaft voltage in industrial electric motors. It focuses on their physical origins and the factors that contribute to shaft voltage. Key causes include high-frequency CMV, parasitic capacitances between the motor components, and the fast switching transients from inverter drives.

- Reviewing the existing shaft voltage reduction techniques: The current techniques to reduce the shaft voltage in industrial electric motors are discussed in detail. These strategies include grounding brushes, insulated bearings, common-mode (CM) chokes, and shielding techniques. The effectiveness and limitations of these methods are also evaluated.

- Offering a comprehensive, diffusion-based shaft voltage analysis framework: It consists of three complementary components:

- Emphasis to denoise shaft voltage signals to get precise depictions of basic cycles and transitions.

- Prediction of maintenance and anomaly reduction can be made possible by probabilistic forecasting of future voltage increases or adverse resonance patterns.

- Synthetic data generation of uncommon or severe shaft voltage settings improves the prediction and adaptability of ML algorithms for diagnosis and control purposes downstream.

- Bridging interdisciplinary domains: The review aims to encourage the integration of signal processing, ML, and power electronics. The paper offers a path for introducing generative artificial intelligence (AI) approaches into electromechanical systems.

- Stimulating future research and industrial implementation: To stimulate future research and industrial implementation by identifying open questions, practical challenges, and potential research directions. It includes real-time installation, artificial augmentation-based data scarcity solutions, and hybrid systems that combine hardware and AI-driven mitigation techniques.

1.3. Contributions to the Literature

2. Review Methodology

2.1. Databases and Time Window

2.2. Search Keywords

- shaft voltage OR bearing voltage OR bearing current OR EDM OR electrostatic discharge

- common-mode voltage OR VFD OR PWM OR inverter-fed motor OR parasitic capacitance

- shaft grounding ring OR insulated bearing OR common-mode choke OR shielding OR slot wedge

- signal denoising OR time-series forecasting OR anomaly detection OR predictive maintenance

- diffusion model OR DDPM OR score-based model OR generative model

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

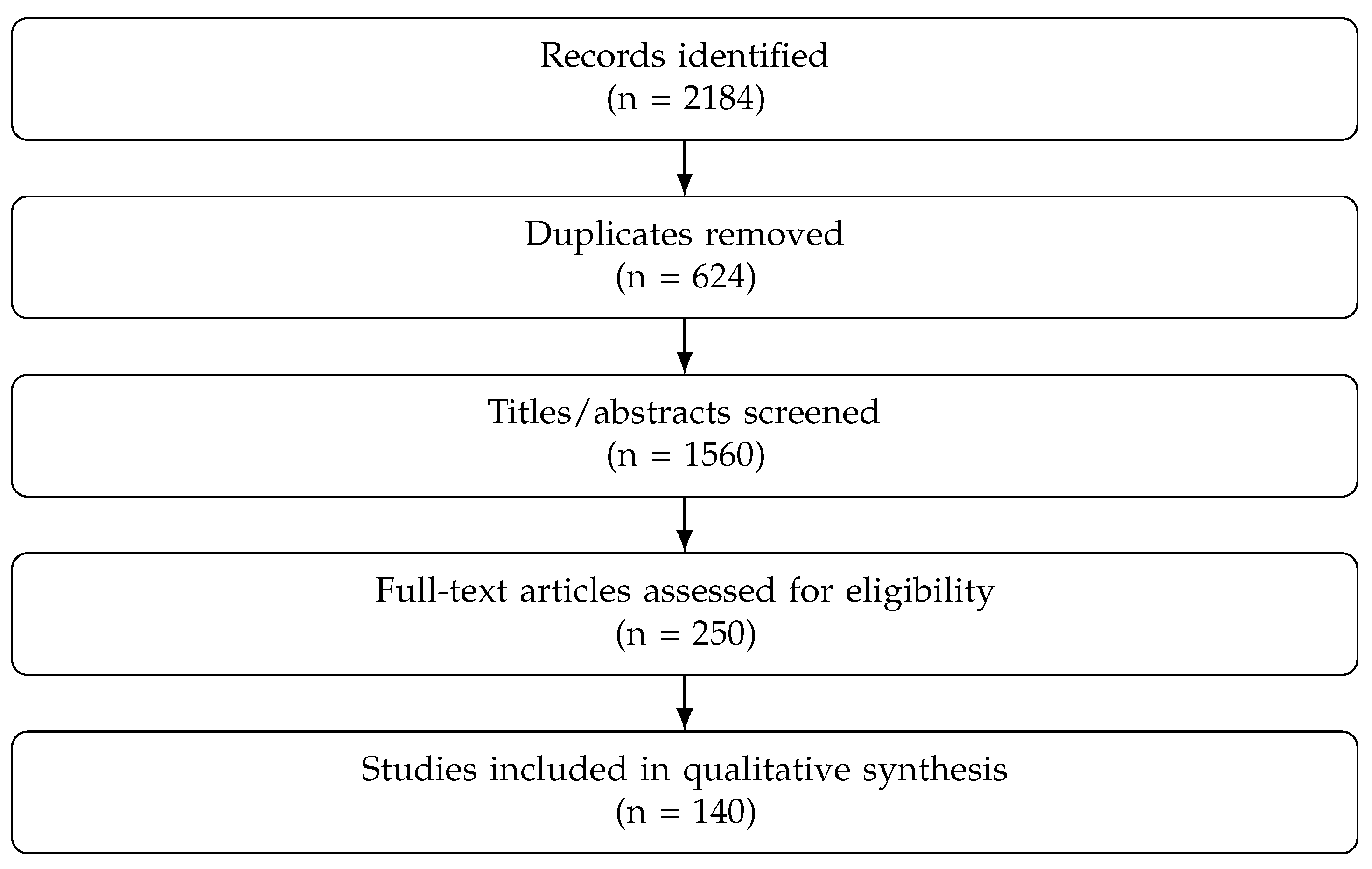

2.4. Study Selection Process

3. Shaft Voltage in Electric Motors

3.1. Origins of Shaft Voltage

3.1.1. Magnetic Imbalance

3.1.2. Common Mode Voltage

3.1.3. Electrostatic Discharge

3.1.4. Shaft Magnetization

3.2. Equivalent Circuit for Measuring the Shaft Voltage

3.3. Review of Shaft Voltage Mitigation Methods

3.3.1. Common Mode Voltage Suppression

3.3.2. Shaft Voltage Grounding

3.3.3. Capacitive Coupling Reduction

3.3.4. Bearing Insulation

3.3.5. Motor Geometry Modification

3.3.6. Hybrid Approaches for Shaft Voltage Mitigation

3.4. Comparative Analysis of Shaft Voltage Mitigation Methods

4. Applications of Artificial Intelligence in Rotating Machines

4.1. Machine Learning & Deep Learning in Vibration Signal Analysis

4.2. Deep Learning in Time-Series and Fault Detection Tasks

4.3. AI-Based Predictive Maintenance

5. Diffusion Models: Theory and Applications

5.1. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models

5.2. Mathematical Formulation of the Diffusion Model Architecture

- Forward Diffusion Process

- ii.

- Time Embedding

- iii.

- Neural Network Denoiser

- iv.

- Reverse Sampling (Denoising)

- v.

- Training Objective

5.3. Recent Developments in Diffusion Models

5.4. Diffusion Models for Industrial Time-Series and Rotating Machinery

6. Comparison of Existing Signal Processing Models with Diffusion Models

6.1. Overview of Signal-Based Modeling

6.2. Advantages of Diffusion Models for Shaft Voltage Analysis

6.3. Summary of Comparative Evaluation

6.4. Relevance to Industrial Motor Systems

7. Challenges and Limitations

7.1. Shaft Voltage Data Scarcity and Limited Fault Labels

7.2. Rotor Speed Dependence and Operating Point Distribution Shift

7.3. Real EMI, Switching Harmonics, and Nonstationary Noise

7.4. Sensor Constraints: Bandwidth, Isolation, Placement, and Reliability

7.5. Latency Requirements, Compute Limits, and Fast Sampling for Online Monitoring

7.6. Hyperparameter Sensitivity and Optimization Difficulty in Industrial Signals

7.7. Integration with PLC/SCADA and End-to-End System Constraints

7.8. Industrial Deployment Scenarios and Real-Time Feasibility

8. Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Acronyms | |

| AE | Acoustic emission |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| BVR | Bearing voltage ratio |

| CM | Common mode |

| CMV | Common mode voltage |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| DAE | Denoising autoencoder |

| DDPM | Denoising diffusion probabilistic model |

| DL | Deep learning |

| DM | Diffusion model |

| DPM | Diffusion probabilistic model |

| EDM | Electrical discharge machining |

| EMD | Empirical mode decomposition |

| EMI | Electromagnetic interference |

| ESD | Electrostatic discharge |

| GAN | Generative adversarial network |

| GMM | Gaussian mixture model |

| GM | Generative model |

| GRU | Gated recurrent unit |

| HHT | Hilbert–Huang transform |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| KD | Knowledge distillation |

| KNN | k-nearest neighbors |

| LSTM | Long short-term memory |

| ML | Machine learning |

| NDE | Non-drive end |

| NN | Neural network |

| OS-ELM | Online sequential extreme learning machine |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| PHM | Prognostics and health management |

| PWM | Pulse width modulation |

| RF | Random forest |

| RUL | Remaining useful life |

| SGR | Shaft grounding ring |

| SHM | Structural health monitoring |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| VFD | Variable frequency drive |

| Symbols | |

| Bearing voltage ratio | |

| Bearing capacitance | |

| Stator-to-rotor capacitance | |

| Winding-to-rotor capacitance | |

| Winding-to-stator capacitance | |

| Time-embedding vector at timestep t | |

| Identity matrix | |

| Training loss function | |

| Phase-A stator inductances | |

| Phase-B stator inductances | |

| Phase-C stator inductances | |

| Reverse diffusion (learned) transition distribution | |

| Forward diffusion transition distribution | |

| t | Diffusion timestep |

| T | Total number of diffusion steps |

| Bearing voltage | |

| Common mode voltage | |

| Shaft voltage | |

| Clean data sample | |

| Noisy data sample at timestep t | |

| Pure noise sample at timestep T | |

| Noise variance schedule parameter | |

| Cumulative product of up to timestep t | |

| Gaussian noise | |

| Predicted noise (network output) | |

| Mean of reverse diffusion transition | |

| Covariance of reverse diffusion transition |

References

- Vostrov, K.; Pyrhönen, J.; Niemelä, M.; Lindh, P.; Ahola, J. On the Application of Extended Grounded Slot Electrodes to Reduce Noncirculating Bearing Currents. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 2286–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazenet, T.; Boileau, T.; Caironi, C.; Nahid-Mobarakeh, B. A Comprehensive Study on Shaft Voltages and Bearing Currents in Rotating Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 54, 3749–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asefi, M.; Nazarzadeh, J. Survey on high-frequency models of PWM electric drives for shaft voltage and bearing current analysis. IET Electr. Syst. Transp. 2017, 7, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Xue, Y.; Han, Q.; Li, X.; Yu, C. Motor Bearing Damage Induced by Bearing Current: A Review. Machines 2022, 10, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludois, D.C.; Reed, J.K. Brushless Mitigation of Bearing Currents in Electric Machines Via Capacitively Coupled Shunting. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2015, 51, 3783–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almounajjed, A.; Sahoo, A.K.; Kumar, M.K. Condition monitoring and fault detection of induction motor based on wavelet denoising with ensemble learning. Electr. Eng. 2022, 104, 2859–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Xu, F.; Hu, M.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Li, M. A novel denoising algorithm based on TVF-EMD and its application in fault classification of rotating machinery. Measurement 2021, 179, 109337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, P.; Buigues, G.; Mazon, A.J. Noise in Electric Motors: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2023, 16, 5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Tang, R.; Yu, S.; Zhang, H. The influence of vibration and acoustic noise of axial flux permanent magnet machines by inverter. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Mechanic Automation and Control Engineering, Wuhan, China, 26–28 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, P.; Cheng, N. Erasing Noise in Signal Detection with Diffusion Model: From Theory to Application. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.07030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemercier, J.M.; Richter, J.; Welker, S.; Moliner, E.; Välimäki, V.; Gerkmann, T. Diffusion Models for Audio Restoration: A review. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2024, 41, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Du, Y.; Habetler, T.G.; Lu, B. A survey of condition monitoring and protection methods for medium-voltage induction motors. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2011, 47, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Êvo, M.T.A.; Alzamora, A.M.; Zaparoli, I.O.; de Paula, H. Inverter-induced bearing currents—A thorough study of the cause-and-effect chains. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Industry Applications Society Annual Meeting (IAS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–14 October 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Shami, U.T.; Akagi, H. Identification and Discussion of the Origin of a Shaft End-to-End Voltage in an Inverter-Driven Motor. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2010, 25, 1615–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaiselvi, J.; Srinivas, S. Bearing currents and shaft voltage reduction in dual-inverter-fed open-end winding induction motor with reduced CMV PWM methods. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 62, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Zhao, M.; Chow, T.W.S.; Pecht, M. Motor Bearing Fault Diagnosis Using Trace Ratio Linear Discriminant Analysis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2014, 61, 2441–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muetze, A.; Oh, H.W. Design aspects of conductive microfiber rings for shaft-grounding purposes. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2008, 44, 1749–1757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.W.; Willwerth, A. Shaft grounding-a solution to motor bearing currents. ASHRAE Trans. 2008, 114, 246–251. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaeili, K.; Wang, L.; Harvey, T.J.; White, N.M.; Holweger, W. Electrical Discharges in Oil-Lubricated Rolling Contacts and Their Detection Using Electrostatic Sensing Technique. Sensors 2022, 22, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prashad, H. Shaft voltages and their origin in rotating machines and flow of electric current through bearings. In Tribology and Interface Engineering Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 49, pp. 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, M.; Minakata, K.; Reznikov, M. Electrostatic enforcement of steam power plant. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Industry Applications Society Annual Meeting, Lake Buena Vista, FL, USA, 6–11 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.K.; Wellawatta, T.R.; Ullah, Z.; Hur, J. New Equivalent Circuit of the IPM-Type BLDC Motor for Calculation of Shaft Voltage by Considering Electric and Magnetic Fields. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2016, 52, 3763–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Li, Y.W. Simultaneous DC Current Balance and CMV Reduction for Parallel CSC System with Interleaved Carrier-Based SPWM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 67, 8495–8505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; He, J. Common-Mode Voltage Reduction and Fault-Tolerant Operation of Four-Leg CSI-Fed Motor Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 8570–8574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Gao, H.; Yuan, L.; Lu, T. Hybrid selective harmonic elimination PWM for common-mode voltage reduction in three-level neutral-point-clamped inverters for variable speed induction drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 27, 1152–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turzynski, M.; Chrzan, P.J. Reducing Common-Mode Voltage and Bearing Currents in Quasi-Resonant DC-Link Inverter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 9553–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turzyński, M.; Musznicki, P. A Review of Reduction Methods of Impact of Common-Mode Voltage on Electric Drives. Energies 2021, 14, 4003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muetze, A.; Oh, H.W. Application of static charge dissipation to mitigate electric discharge bearing currents. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2008, 44, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muetze, A.; Oh, H.W. Current-carrying characteristics of conductive microfiber electrical contact for high frequencies and current amplitudes: Theory and applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2010, 25, 2082–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willwerth, A.; Roman, M. Electrical bearing damage—A lurking problem in inverter-driven traction motors. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC), Detroit, MI, USA, 16–19 June 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Z.; Xia, Y.; Ge, X. Conductive capacity and tribological properties of several carbon materials in conductive greases. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2016, 68, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzumura, J. Prevention of electrical pitting on rolling bearings by electrically conductive grease. Q. Rep. RTRI 2016, 57, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.J.T.E.; Cistelecan, M.V.; de Almeida, A.T. Evaluation of slot-embedded partial electrostatic shield for high-frequency bearing current mitigation in inverter-fed induction motors. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2012, 27, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Bai, B.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W. Research on electrostatic shield for discharge bearing currents suppression in variable-frequency motors. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems, Hangzhou, China, 22–25 October 2014; pp. 139–143. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X. Suppression for discharging bearing current in variable-frequency motors based on electromagnetic shielding slot wedge. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2015, 51, 8109404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdun, O.; Gemeinder, Y.; Binder, A. Prevention of harmful EDM currents in inverter-fed AC machines by use of electrostatic shields in the stator winding over-hang. In Proceedings of the IECON 2010—36th Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Glendale, AZ, USA, 7–10 November 2010; pp. 962–967. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.K.; Wellawatta, T.R.; Choi, S.J.; Hur, J. Mitigation Method of the Shaft Voltage According to Parasitic Capacitance of the PMSM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2017, 53, 4441–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vostrov, K.; Pyrhönen, J.; Lindh, P.; Niemelä, M.; Ahola, J. Mitigation of Inverter-Induced Noncirculating Bearing Currents by Introducing Grounded Electrodes into Stator Slot Openings. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 11752–11760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuermann, S.; Brodatzki, M.; Doppelbauer, M. Investigation of electrostatic shieldings in traction motors to mitigate capacitive bearing currents. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Power Electronics, Electrical Drives, Automation and Motion (SPEEDAM), Napoli, Italy, 19–21 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, J.H.; Kang, J.K.; Im, J.H.; Hur, J. Proposing the New Layered-Shield Structure for Shaft Voltage Reduction in IPMSM. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 4313–4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.K.; Heo, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Hur, J. Novel Structure of Shield Ring to Reduce Shaft Voltage and Improve Cooling Performance of Interior Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Electronics 2024, 13, 1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.; Cistelecan, M.; Almeida, A. Slot-embedded partial electrostatic shield for high-frequency bearing current mitigation in inverter-fed induction motors. In Proceedings of the XIX International Conference on Electrical Machines (ICEM 2010), Rome, Italy, 6–8 September 2010; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Muetze, A.; Binder, A. Practical rules for assessment of inverter-induced bearing currents in inverter-FED AC motors up to 500 kW. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2007, 54, 1614–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Gaetano, D.D.; Chen, X.; Jewell, G.W.; Hu, Y. A review of modeling and mitigation techniques for bearing currents in electrical machines with variable-frequency drives. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 125279–125297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedneault-Desroches, J.; Merkhouf, A.; Al-Haddad, K. Hydrogenerators’ Vulnerability Towards Bearing Insulation Systems, Shaft Voltage and Current. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Electrical Insulation Conference (EIC), Quebec City, QC, Canada, 18–21 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Han, P.; Heins, G.; Patterson, D.; Thiele, M.; Ionel, D.M. Evaluation of Bearing Voltage Reduction in Electric Machines by Using Insulated Shaft and Bearings. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Detroit, MI, USA, 11–15 October 2020; pp. 5584–5589. [Google Scholar]

- Binder, A.; Muetze, A. Scaling Effects of Inverter-Induced Bearing Currents in AC Machines. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Electric Machines & Drives Conference, Antalya, Turkey, 3–5 May 2007; pp. 1477–1483. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, J.; Guerrero, G.; Goldman, J. Ceramic bearings for electric motors: Eliminating damage with new materials. IEEE Ind. Appl. Mag. 2017, 23, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Wu, Z. Characteristic Research of Bearing Currents in Inverter-Motor Drive Systems. In Proceedings of the 2006 CES/IEEE 5th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference, Shanghai, China, 14–16 August 2006; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Cohen, Y.; Lee, H.J.; Badescu, M.; Sherrit, S.; Bao, X.; Shalev, Y. Specialized Drilling Techniques for Medical Applications. In Advances in Terrestrial and Extraterrestrial Drilling: Ground, Ice, and Underwater; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume Chapter 9, p. 271. [Google Scholar]

- Gaetano, D.D.; Zhu, W.; Sun, X.; Chen, X.; Griffo, A.; Jewell, G.W. Novel Stator Slot Opening to Reduce Electrical Machine Bearing Currents. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2023, 59, 8101605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yea, M.; Han, K.J. Modified slot opening for reducing shaft-to-frame voltage of AC motors. Energies 2020, 13, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhausen, S.; Jarek, T. Method of Limiting Shaft Voltages in AC Electric Machines. Energies 2021, 14, 3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Wang, X.; Zhao, W.; Ren, J. Study on shaft voltage in fractional slot permanent magnet machine with different pole and slot number combinations. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2019, 55, 8102305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maetani, T.; Isomura, Y.; Watanabe, A.; Iimori, K.; Morimoto, S. Suppressing bearing voltage in an inverter-fed ungrounded brushless DC motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2013, 60, 4861–4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.T.; Cha, S.H.; Hur, J.; Shim, J.-S.; Kim, B.-W. Suppression of shaft voltage by rotor and magnet shape design of IPM-type high voltage motor. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2013, 8, 938–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Cheng, Y.; Du, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Cui, S. Research on Analysis and Suppression Methods of the Bearing Current for Electric Vehicle Motor Driven by SiC Inverter. Energies 2024, 17, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqil, M.; Im, J.H.; Hur, J. Application of Perovskite Layer to Rotor for Enhanced Stator-Rotor Capacitance for PMSM Shaft Voltage Reduction. Energies 2020, 13, 5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.T.; Park, J.K.; Jeong, C.L.; Rhyu, S.H.; Hur, J. Shaft-to-Frame Voltage Mitigation Method by Changing Winding-to-Rotor Parasitic Capacitance of IPMSM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 1430–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, H. Review on pulse-width modulation strategies for common-mode voltage reduction in three-phase voltage-source inverters. IET Power Electron. 2016, 9, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Chen, J.; Shen, Z. Common mode EMI reduction through PWM methods for three-phase motor controller. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2019, 3, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, M.C.D.; Ragusa, A.; Vitale, G. Effect of common-mode active filtering in induction motor drives for electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2010, 59, 2664–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Maillet, Y.Y.; Wang, F.; Boroyevich, D.; Burgos, R. Investigation of hybrid EMI filters for common-mode EMI suppression in a motor drive system. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2010, 25, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Boroyevich, D.; Gazel, N.; Kang, Y.; Baisden, A.C. Analysis of CM volt-second influence on CM inductor saturation and design for input EMI filters in three-phase dc-fed motor drive systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2010, 25, 1905–1914. [Google Scholar]

- Ström, J.P.; Tyster, J.; Korhonen, J.; Purhonen, M.; Silventoinen, P. Active du/dt filter dimensioning in variable speed AC drives. In Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications, Birmingham, UK, 30 August–1 September 2011; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Muetze, A. Scaling issues for common-mode chokes to mitigate ground currents in inverter-based drive systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2009, 45, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanigovszki, N.; Landkildehus, J.; Blaabjerg, F. Output filters for AC adjustable speed drives. In Proceedings of the APEC 07—Twenty-Second Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition, Anaheim, CA, USA, 25 February–1 March 2007; pp. 236–242. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, G.; Sheron, F.; Das, A.; Sivakumar, K.; Gopakumar, K. A DC-link capacitor voltage balancing with CMV elimination using only the switching state redundancies for a reduced switch count multi-level inverter fed IM drive. EPE J. 2009, 19, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, K.J.; Zuckerberger, A.; Rabinovici, R. Fourth-arm common-mode voltage mitigation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, C.; Balda, J.; Waite, W. Cancellation of common-mode voltages for induction motor drives using active method. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2006, 21, 380–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muetze, A.; Sullivan, C. Simplified Design of Common-Mode Chokes for Reduction of Motor Ground Currents in Inverter Drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2011, 47, 2570–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muetze, A.; Binder, A. Calculation of influence of insulated bearings and insulated inner bearing seats on circulating bearing currents in machines of inverter-based drive systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2006, 42, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.; Willwerth, A. New motor design with conductive micro fiber shaft grounding ring prevents bearing failure in PWE inverter driven motors. In Proceedings of the 2007 Electrical Insulation Conference and Electrical Manufacturing Expo, Nashville, TN, USA, 22–24 October 2007; pp. 240–246. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, R.A.; Saeed, N.; Masood, M.; Fard, Y.M.; Alouini, M.S.; Al-Naffouri, T.Y. Deep learning in the industrial internet of things: Potentials, challenges, and emerging applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 11016–11040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Nahin, K.H.; Nirob, J.H.; Ahmed, M.K.; Sawaran Singh, N.S.; Paul, L.C.; Ateya, A.A. Multiband THz MIMO antenna with regression machine learning techniques for isolation prediction in IoT applications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, F.; Ding, N.; Li, N.; Liu, L.; Hou, N.; Xu, N.; Chen, X. A review of bearing failure Modes, mechanisms and causes. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 152, 107518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krentowski, J.R. Assessment of destructive impact of different factors on concrete structures durability. Materials 2021, 15, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.L.; Li, G.; Yu, D.H.; Dong, Z.Q. Framework for seismic risk analysis of engineering structures considering the coupling damage from multienvironmental factors. J. Struct. Eng. 2024, 150, 04024147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, S.; Dackermann, U. A systematic review of advanced sensor technologies for non-destructive testing and structural health monitoring. Sensors 2023, 23, 2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralovec, C.; Schagerl, M. Review of structural health monitoring methods regarding a multi-sensor approach for damage assessment of metal and composite structures. Sensors 2020, 20, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanssini, M.; de Aguirre, P.C.C.; Compassi-Severo, L.; Girardi, A.G. A review on vibration monitoring techniques for predictive maintenance of rotating machinery. Eng 2023, 4, 1797–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nithin, S.K.; Hemanth, K.; Shamanth, V.; Mahale, R.S.; Sharath, P.C.; Patil, A. Importance of condition monitoring in mechanical domain. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 54, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagatheesaperumal, S.K.; Rahouti, M.; Ahmad, K.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Guizani, M. The duo of artificial intelligence and big data for Industry 4.0: Applications, techniques, challenges, and future research directions. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 12861–12885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, N.N.; Dixit, Y.; Al-Mallahi, A.; Bhullar, M.S.; Upadhyay, R.; Martynenko, A. IoT, big data, and artificial intelligence in agriculture and food industry. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 9, 6305–6324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, F.; Sous, C.; Chaib, A.O.; Jacobs, G. Machine learning based anomaly detection and classification of acoustic emission events for wear monitoring in sliding bearing systems. Tribol. Int. 2021, 155, 106811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Guo, Q.; Song, Y.; Gao, S.; Li, Y. Application of multiscale learning neural network based on CNN in bearing fault diagnosis. J. Signal Process. Syst. 2019, 91, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, J.; Hur, K.; Kim, H. CNN and GRU combination scheme for bearing anomaly detection in rotating machinery health monitoring. In Proceedings of the 2018 1st IEEE International Conference on Knowledge Innovation and Invention (ICKII), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 23–27 July 2018; pp. 102–105. [Google Scholar]

- Ou, J.; Li, H.; Huang, G.; Yang, G. Intelligent analysis of tool wear state using stacked denoising autoencoder with online sequential-extreme learning machine. Measurement 2021, 167, 108153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, A.; Khan, S.S.; Ahmad, A. Ensemble of autoencoders for anomaly detection in biomedical data: A narrative review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 17273–17289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stefano, A.G.; Ruta, M.; Masera, G. Advanced digital tools for data-informed and performance-driven design: A review of building energy consumption forecasting models based on machine learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, P.V.; Desavale, R.G. Application of dimension analysis and soft competitive tool to predict compound faults present in rotor-bearing systems. Measurement 2022, 193, 110984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, P.M.; Kumbhar, S.G.; Desavale, R.G.; Patil, S.B. Distributed fault diagnosis of rotor-bearing system using dimensional analysis and experimental methods. Measurement 2020, 166, 108239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, F.M.; Perumal, T.; Mustapha, N.; Mohamed, R. A comprehensive overview and comparative analysis on deep learning models: CNN, RNN, LSTM, GRU. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.17473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunsch, A.; Liesch, T.; Broda, S. Groundwater level forecasting with artificial neural networks: A comparison of long short-term memory (LSTM), convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and non-linear autoregressive networks with exogenous input (NARX). Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 1671–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, D.; Wang, H. Data-driven methods for predictive maintenance of industrial equipment: A survey. IEEE Syst. J. 2019, 13, 2213–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, W.; Ding, X.; Tang, S.; Xu, J.; Shi, B.; Liu, Y. Vibration analysis for fault detection of wind turbine drivetrains—A comprehensive investigation. Sensors 2021, 21, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.P.; Chauhan, P.S.; Pandit, P.P. Time domain vibration analysis techniques for condition monitoring of rolling element bearing: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 6336–6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaneghah, M.Z.; Alzayed, M.; Chaoui, H. Fault detection and diagnosis of the electric motor drive and battery system of electric vehicles. Machines 2023, 11, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, W.; Hu, Y.; Gong, C.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Deng, J. Artificial intelligence-based technique for fault detection and diagnosis of EV motors: A review. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2021, 8, 384–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, W.G.C.; Nair, N.G.; Patel, V.M. DDPM-CD: Denoising diffusion probabilistic models as feature extractors for change detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2206.11892. [Google Scholar]

- Koller, D.; Friedman, N. Probabilistic Graphical Models: Principles and Techniques; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, S.; Hayes, T.; Yang, H.; Yin, X.; Pang, G.; Jacobs, D.; Huang, J.B.; Parikh, D. Long video generation with time-agnostic VQGAN and time-sensitive transformer. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Chen, X.; Xie, S.; Li, Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Masked Autoencoders Are Scalable Vision Learners. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 16000–16009. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, G.; Ma, X.; Wang, X. Structural Pruning for Diffusion Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.10924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Ermon, S. Generative Modeling by Estimating Gradients of the Data Distribution. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, Y.; Mao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Song, M.; Wang, X.; Tao, D. Learning Graph Neural Networks for Image Style Transfer. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Qiu, J.; Song, M.; Tao, D.; Wang, X. Distilling Knowledge from Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J.; Wang, X. Diffusion Probabilistic Model Made Slim. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bentamou, A.; Chretien, S.; Gavet, Y. 3D Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models for 3D microstructure image generation of fuel cell electrodes. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2025, 248, 113596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengesi, S.; El-Sayed, H.; Sarker, M.K.; Houkpati, Y.; Irungu, J.; Oladunni, T. Advancements in Generative AI: A Comprehensive Review of GANs, GPT, Autoencoders, Diffusion Model, and Transformers. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 69812–69837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, G.; Zhao, L.; Ma, Y.; Ma, M.; Zhou, B. Efficient diffusion models: A comprehensive survey from principles to practices. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025, 47, 7506–7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, W.; Ren, Y. A Comprehensive Survey of Image Generation Models Based on Deep Learning. Ann. Data Sci. 2025, 12, 141–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Jin, M.; Wen, H.; Zhang, C.; Liang, Y.; Ma, L.; Wen, Q. A survey on diffusion models for time series and spatio-temporal data. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.18886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y. An observed value consistent diffusion model for imputing missing values in multivariate time series. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Long Beach, CA, USA, 6–10 August 2023; pp. 2409–2418. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Zheng, G.; Wang, X.; Zhou, C. Mtsci: A conditional diffusion model for multivariate time series consistent imputation. In Proceedings of the 33rd ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Boise, IA, USA, 21–25 October 2024; pp. 3474–3483. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, B.; Duan, Y.; Zhou, W. Few-shot aero-engine bearing fault diagnosis with denoising diffusion based data augmentation. Neurocomputing 2025, 622, 129327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashiro, Y.; Song, J.; Song, Y.; Ermon, S. CSDI: Conditional Score-based Diffusion Models for Probabilistic Time Series Imputation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.03502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.Y.; Lim, M.H.; Ngui, W.K.; Leong, M.S. Denoising diffusion implicit model for bearing fault diagnosis under different working loads. In ITM Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Grenoble, France, 2024; Volume 63, p. 01025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, P.; Zhang, W.; Cao, X.; Li, X. Denoising diffusion probabilistic model-enabled data augmentation method for intelligent machine fault diagnosis. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Fan, C.; Jiang, Z.; Yu, K.; Ren, Z.; Feng, K. Diffusion model-assisted cross-domain fault diagnosis for rotating machinery under limited data. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 264, 111372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Wen, C.; Liu, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, D. Industrial Anomaly Detection Based on Improved Diffusion Model: A Review. Cogn. Comput. 2025, 17, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Gao, Z. From Model, Signal to Knowledge: A Data-Driven Perspective of Fault Detection and Diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informatics 2013, 9, 2226–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, R.A.; Ravindran, V.; Rönnberg, S.K.; Bollen, M.H.J. Deep Learning Method with Manual Post-Processing for Identification of Spectral Patterns of Waveform Distortion in PV Installations. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2021, 12, 5444–5456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Paffenroth, R.C. Anomaly Detection with Robust Deep Autoencoders. In Proceedings of the 23rd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (KDD ’17), Halifax, NS, Canada, 13–17 August 2017; pp. 665–674. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, C.; Chen, W.; Ma, Z.; Yan, J.; Sun, L. Transformers in Time Series: A Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2202.07125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Hong, S.; Xu, R.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Cui, B.; Yang, M.H. Diffusion Models: A Comprehensive Survey of Methods and Applications. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 56, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Gupta, A. Dealing with Noise Problem in Machine Learning Data-sets: A Systematic Review. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 161, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, A.F.; Seward, C.; Schuster, I.; Vollgraf, R. Autoregressive Denoising Diffusion Models for Multivariate Probabilistic Time Series Forecasting. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.12072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Bu, J.; Li, S.; Cao, J. ImDiffusion: Imputed Diffusion Models for Multivariate Time Series Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.00754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Bu, J.; VanGemert, J.; Cao, J. Optimizing Diffusion Models for Multivariate Time Series Classification via Squeezed-State Encoding and Bures-Wasserstein Metric. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.05740. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Chen, W.; Hu, X.; Chen, B.; Sun, B.; Zhou, M. Transformer-Modulated Diffusion Models for Probabilistic Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, T.; Zhang, H.; Hua, W.; Zhang, F. Comprehensive Review of Bearing Currents in Electrical Machines: Mechanisms, Impacts, and Mitigation Techniques. Energies 2025, 18, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailula, K.O.; Saha, K.A. A Comprehensive Review of Shaft Voltages and Bearing Currents, Measurements and Monitoring Systems in Large Turbogenerators. Energies 2025, 18, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimans, T.; Ho, J. Progressive Distillation for Fast Sampling of Diffusion Models. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.00512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimans, T.; Mensink, T.; Heek, J.; Hoogeboom, E. Multistep Distillation of Diffusion Models via Moment Matching. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 36046–36070. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Song, Y. Simplifying, Stabilizing & Scaling Continuous-Time Consistency Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.11081. [Google Scholar]

- OPC Foundation. OPC Unified Architecture: Interoperability for Industrie 4.0 and the Internet of Things; Whitepaper (PDF); OPC Foundation: Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2024; Version V17. [Google Scholar]

- Mennilli, R.; Mazza, L.; Mura, A. Integrating Machine Learning for Predictive Maintenance on Resource-Constrained PLCs: A Feasibility Study. Sensors 2025, 25, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Shaft Voltage Origins | Sources | References |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Asymmetry | - Rotor and stator eccentricity. | [2,14] |

| - Imbalance winding. | ||

| CMV | - Switching transients of VFDs | [15,16] |

| ESD | - Potential induced by particle impingement. | [17,18,19] |

| - Potential due to charged particles. | ||

| - Permanent magnetization of casing or pedestals. | ||

| Shaft Magnetization | - Unbalanced ampere turns around the shaft. | [20,21] |

| - Unintended electrical contact between rotor winding and core. |

| Mitigation Method | Implementation Type | Working Principle | Limitations | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMV suppression | Hybrid | Using common mode chokes and supervised PWM strategies. | Increased complexity and computational costs. | [15,23,24,25,26,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71] |

| Shaft voltage grounding | Hardware | Adding a low impedance path for bearing currents to divert them from the bearings to the ground. | Periodic maintenance requirement and high cost. | [5,17,28,29,30,31,32] |

| Capacitive coupling reduction | Hardware | Reducing the parasitic capacitances of the motor contributing to shaft voltage. | High cost and slot-fill factor considerations. | [1,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,58,59] |

| Bearing insulation | Hardware | Increasing the impedance for blocking the bearing currents. | Costly. The safety of other components connected to the bearings becomes sensitive. | [43,44,45,46,47,48,49,72,73] |

| Motor geometry modification | Hardware | Modifying the motors’s geometry that include winding patterns, slot structure, and rotor design. | Invasive nature. Imposes additional working and labor costs. | [37,50,51,52,53,54,55,56] |

| Hybrid approach | Hybrid | Employing multiple shaft voltage mitigation strategies. | Handling can be complex. Increases computational time and costs due to multiple components. | [27,57,58,59] |

| Model Type | Example Methods | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| ML | SVM, RF, KNN. | Low training time, interpretable. | Poor at capturing temporal features. |

| Performance drops with noise. | |||

| DL | CNN, LSTM, GRU. | Good for sequential and high-dimensional data. | Requires large datasets. |

| Difficult to interpret; overfitting risk. | |||

| Autoencoders | Denoising, Variational. | Useful for anomaly detection and compression. | Struggles with time-variant behavior. |

| Weak generalization in new conditions. | |||

| Transformers | Attention-based models. | Excellent at long-range dependency modeling. | High computational cost. |

| May require extensive pretraining. |

| Feature | ML Models | DL Models | DMs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Requirement | Low | High | Moderate–High |

| Robustness to Noise | Low | Medium | High |

| Temporal Feature Capture | Poor | Good | Excellent |

| Interpretability | Medium | Low | Low–Medium |

| Uncertainty Modeling | No | Limited | Yes |

| Generalization | Medium | Medium | High |

| Computational Cost | Low | High | High |

| Diffusion-Based Model | Primary Task | Compared Against (Examples) | Dataset/Setting | Reported Quantitative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSDI [117] | TS imputation | Probabilistic imputers; SOTA deterministic imputers | Healthcare & environmental TS | Improves by 40–65% on probabilistic metrics; reduces deterministic imputation error by 5–20%. |

| TimeGrad [128] | Probabilistic forecasting | VAR, LSTM-copula, GP, Transformer | High-dimensional benchmarks | Lower CRPS than strong baselines (e.g., Traffic: 0.110 vs. 0.133; Taxi: 0.311 vs. 0.346). |

| ImDiffusion [129] | Anomaly detection | Forecasting- and reconstruction-based detectors | Benchmarks + Microsoft production | In production, reports + 11.4% improvement in detection F1-score vs. a legacy approach. |

| MTSCI [130] | Time-series classification | Strong classification baselines (reported) | MTSCL benchmark | Reports average improvements of 17.88% (MSE), 15.09% (MAE), and 13.64% (RMSE) over baselines. |

| TMDM [131] | Uncertainty-aware forecasting | Strong SOTA forecasters (reported) | Weather/ Electricity/ Traffic | Improves predictive-interval coverage (PICP) by +3.42 (71.12→74.54) on Weather, +2.99 (84.98→87.97) on Electricity, and +4.62 (78.03→82.65) on Traffic. |

| Scenario | Signals | Sampling (Edge → PLC) | Compute Location | Latency Target | PLC/SCADA Integration (Outputs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrofit monitoring | , CMV proxy (opt.), bearing current (opt.) | kHz-range → Hz-range | IPC (CPU) near drive | sub-second to seconds | Alarm flag + severity + discharge-rate via OPC UA/Modbus; maintenance trigger. |

| Cabinet edge analytics | , phase currents, , temp (opt.) | high-rate → low-rate | IPC + optional GPU/NPU | tens–hundreds ms | Uncertainty bounds + health indicators; mitigation logic (filters/PWM changes). |

| Fast-event protection | High-bandwidth , bearing current, PWM timing | event-based reporting | Edge GPU/NPU | ms-scale | Event flags/time-stamps; PLC protective action (PWM change/controlled stop). |

| Digital twin planning | Aggregated trends/indicators | low-rate reporting | Edge + server/cloud | seconds–minutes | Dashboards + trend/RUL; integrates with SCADA/CMMS. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abbas, Z.; Zahir, A.; Hur, J. Enhancing Shaft Voltage Mitigation with Diffusion Models: A Comprehensive Review for Industrial Electric Motors. Energies 2025, 18, 6504. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246504

Abbas Z, Zahir A, Hur J. Enhancing Shaft Voltage Mitigation with Diffusion Models: A Comprehensive Review for Industrial Electric Motors. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6504. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246504

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbas, Zuhair, Arifa Zahir, and Jin Hur. 2025. "Enhancing Shaft Voltage Mitigation with Diffusion Models: A Comprehensive Review for Industrial Electric Motors" Energies 18, no. 24: 6504. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246504

APA StyleAbbas, Z., Zahir, A., & Hur, J. (2025). Enhancing Shaft Voltage Mitigation with Diffusion Models: A Comprehensive Review for Industrial Electric Motors. Energies, 18(24), 6504. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246504