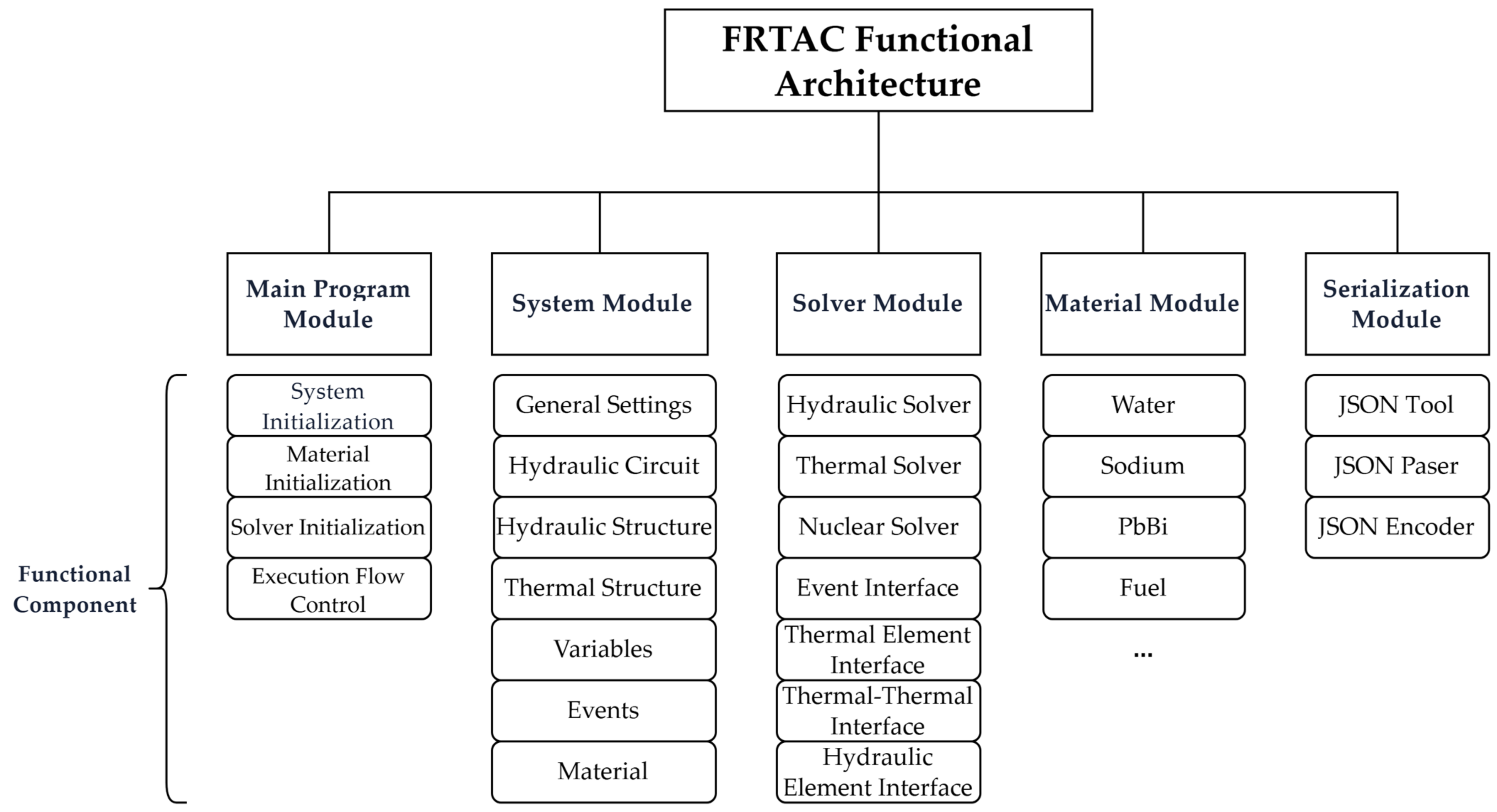

2.1. System Functional Architecture

FRTAC is a system safety analysis code for LMRs that supports thermal–hydraulic simulations for both steady-state and transient conditions, capable of analyzing system responses during normal operation, startup/shutdown, and various design basis accidents. The code has multi-scale modeling capabilities, allowing for detailed modeling of key components such as the reactor core, primary coolant system, intermediate loop, and steam generator. Many studies have used FRTAC as a tool for accident analysis and safety assessment of nuclear facilities, such as EBR-II [

17] and small lead-cooled reactors [

18].

The program is developed in the object-oriented C++ language, adhering to modular design principles to ensure its extensibility, maintainability, and robustness. The entire program consists of five core modules, each with clear responsibilities, working collaboratively to complete complex system transient analysis tasks. Its original functional architecture is shown in

Figure 1.

Main Program Module: As the program’s entry point, it is responsible for system initialization, configuration loading, coordination between modules, and controlling the overall calculation flow, ensuring all modules operate efficiently in the prescribed order.

System Module: Stores all state-related system variables; constructs and manages the physical models of the entire reactor system, including hydraulic circuits, thermal structures, and nuclear parameters; builds the control system, setting control variables and trigger events; loads built-in and externally defined material information.

Solver Module: As the core computational unit responsible for transient analysis in FRTAC, this module integrates multiple sub-solvers and coupled calculation interfaces. The hydraulic solver is based on a staggered-grid finite volume method and employs a semi-implicit discretization scheme to solve the one-dimensional mass, momentum, and energy conservation equations for the fluid. The thermal conduction solver uses a fully implicit finite volume formulation on a two-dimensional mesh to resolve transient heat conduction in thermal components. The nuclear solver solves the point kinetics model together with the decay heat model, with time integration carried out using a first-order Taylor expansion. The event interface updates the function values associated with triggered events at the current time level. The inter-component coupling interface handles the coupled calculations between thermal structures and hydraulic component. Furthermore, reactivity feedback is computed within the nuclear solver: after the hydraulic and thermal solvers complete their calculations at each time step, the nuclear solver evaluates various reactivity feedback terms based on the geometric and thermophysical properties of the fluid and thermal components.

Material Module: Provides a library of physical properties for various built-in materials such as sodium, water, fuel, and structural steel.

Serialization Module: Responsible for the program’s input/output, parsing user-input configuration files, and generating formatted result files for subsequent processing.

2.3. Numerical Solution Methods

2.3.1. Discretization of Fluid Equations

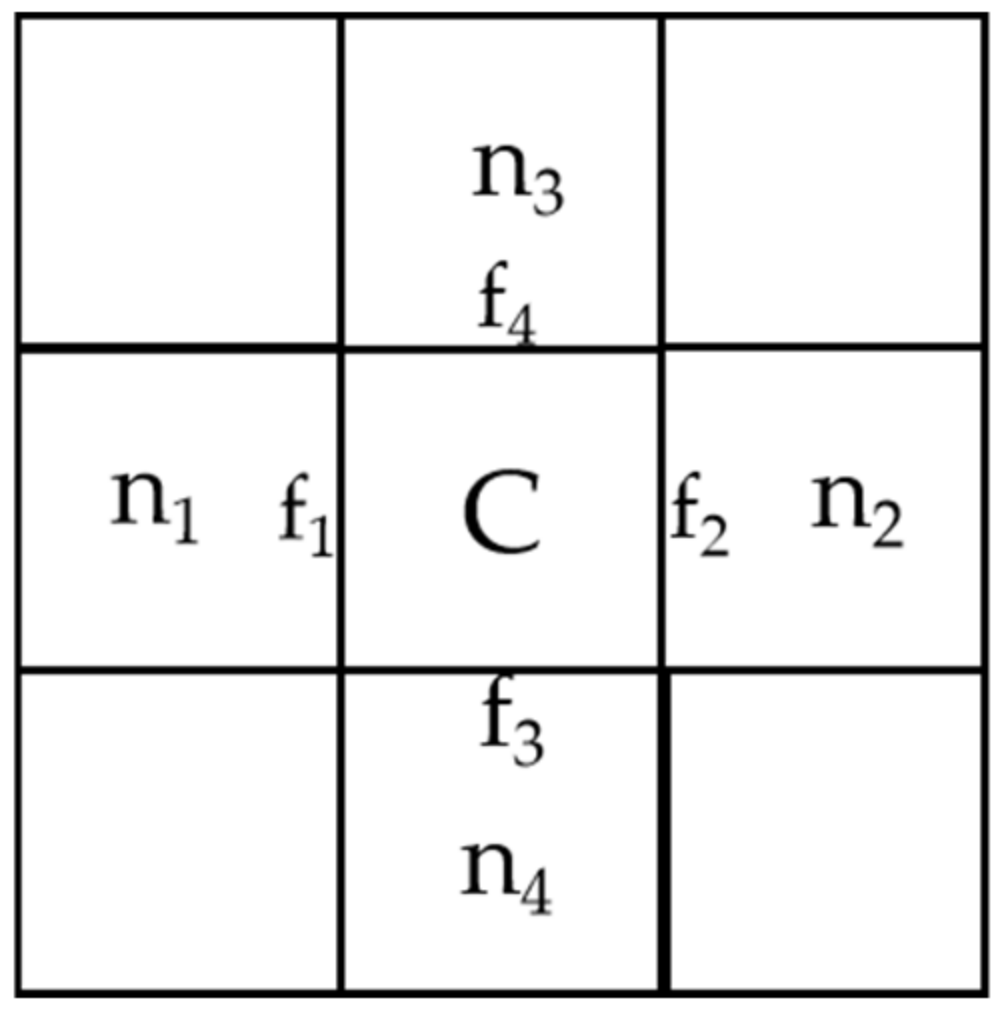

The fluid equations are discretized using the staggered grid finite volume method. Scalar quantities like density, enthalpy (or temperature), and pressure are solved at the center of the grid cells, while velocity is solved at the junctions between grid cells. A schematic of the grid division is shown in

Figure 3.

The mass and energy equations are discretized for the control volume j. The momentum equation is discretized at the j + 1/2 junction. A semi-implicit scheme is used for the discretization of the control equations.

Discretizing and simplifying the mass equation yields:

Differencing and simplifying the momentum equation gives:

Discretizing the energy conservation equation results in:

Substituting the discretized mass Equation (8) and momentum Equation (9) into the energy Equation (10) gives:

Finally, a system of non-linear equations is obtained that depends only on the control volume pressures. Let the left side of Equation (11) be denoted as

Ej. The Newton-Raphson method [

20] is used to solve this system of equations:

After obtaining the pressure changes

,

,

, taking

as an example, the pressure for the

k + 1 iteration is updated as follows

By substituting the final calculated pressure values into the mass, momentum, and state equations, other quantities such as control volume density, junction velocity, control volume specific enthalpy, fluid temperature, and void fraction can be obtained.

2.3.2. Discretization of Heat Conduction Equation

A two-dimensional grid system is used for thermal structures, with its mesh structure shown in

Figure 4. The interfaces between grid cells in the thermal structure are divided into internal interfaces and boundary interfaces, with the latter corresponding to the three types of boundary conditions.

Taking control volume C as an example, the heat conduction equation is discretized using a fully implicit scheme, forming a system of linear equations for temperature.

When control volume C is an internal control volume, i.e., all four sides are internal interfaces, the discretized heat conduction equation is:

For the first-kind boundary condition, assuming

f1 is the boundary surface with temperature

, the discretized equation is:

For the second-kind boundary condition, assuming

f1 is the boundary surface with heat flux

, the discretized equation is:

For the third-kind boundary condition, assuming

f1 is the boundary surface, with external fluid temperature

, and convective heat transfer coefficient

:

where

ρ is the nodal density,

δτ is the nodal volume,

S is the nodal volumetric power density,

δx is the nodal length,

λ is the nodal thermal conductivity,

T is the nodal temperature,

is the interface area,

is the interface thermal conductivity, and

is the interface length.

The coefficient matrix for temperature is constructed based on Equations (16) to (19). It is necessary to traverse every node and determine the coefficients of its corresponding equation based on the type of each of its interfaces, placing them into the appropriate positions in the coefficient matrix and source vector.

Ultimately, the following standard form is obtained:

where

Tc is the temperature of the central node,

Tnb is the temperature of its neighboring nodes,

ac is the diagonal element of the coefficient matrix,

−anb is the off-diagonal element of the coefficient matrix, and

b is the source vector. This linear system is solved using a direct method, requiring no iteration.

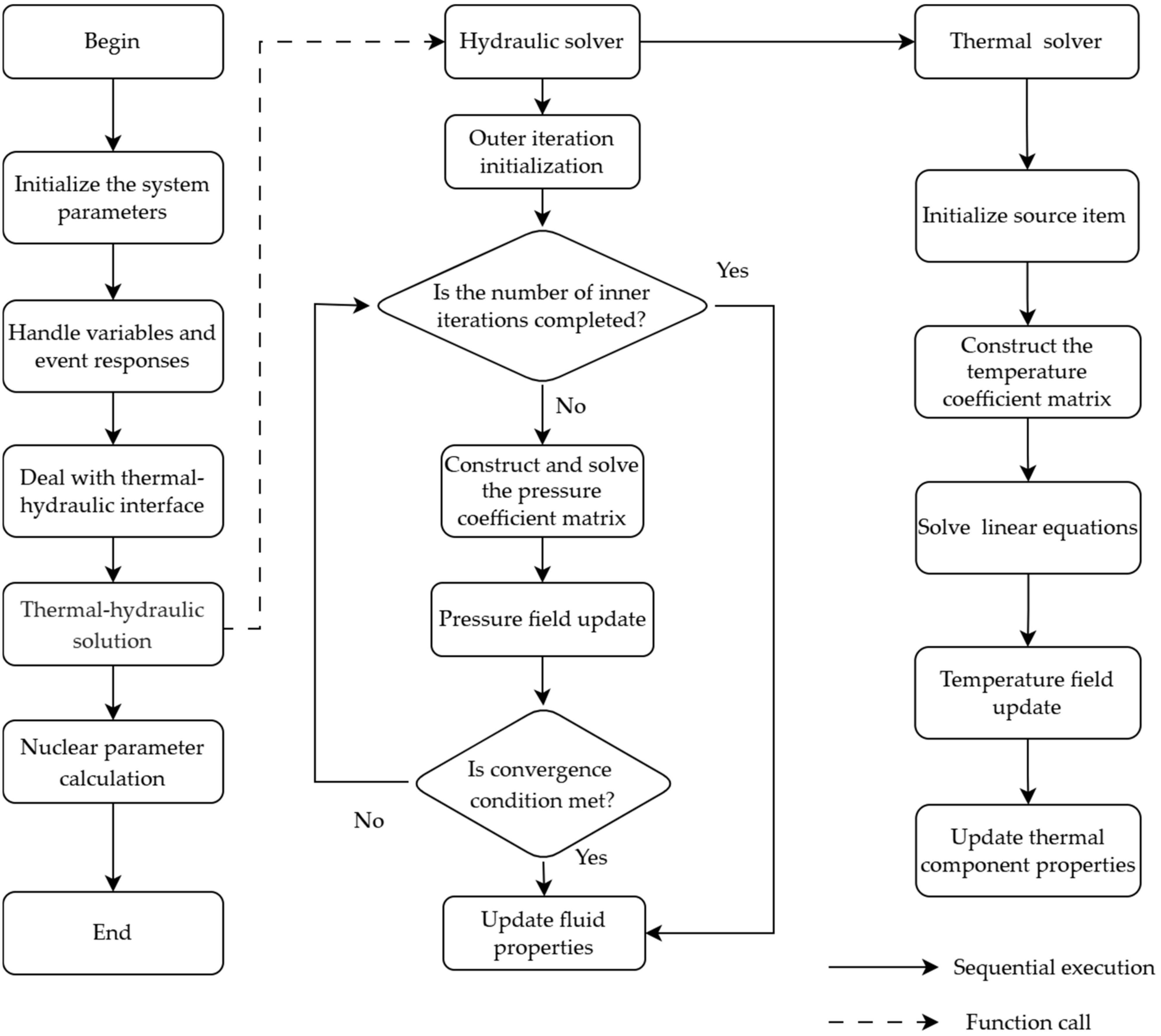

2.4. Solution Procedure

The main solution procedure of the program is shown in

Figure 5, where the thermal–hydraulic calculation provides detailed subroutine call information.

After the program starts, it first initializes various system parameters, such as system configuration information, material information, and solver information. Before calculation, event handling is performed to determine if any event meeting the trigger conditions has occurred, modifying the physical field properties of the triggered objects. Next, the thermal–hydraulic interface heat transfer process is handled; this process explicitly treats the thermal power generated by convective heat transfer as an external heat source for the fluid and updates the boundary values of the third-kind boundary conditions on the thermal component surfaces coupled with the fluid.

After handling the above processes, the hydraulic solver subroutine is called to solve the pressure non-linear system, and the thermal solver is called to solve the temperature linear system.

The hydraulic solver involves outer and inner iteration processes. Outer iteration initialization calculates the source terms needed for solving the pressure matrix, including calculating the control volume frictional resistance, then averaging to obtain the junction frictional resistance based on the calculated control volume friction; calculating local frictional resistance, involving four types: sudden enlargement, sudden contraction, bends, and valves; and finally updating inter-grid heat conduction for the fluid. The inner iteration constructs the pressure coefficient matrix and uses the Newton-Raphson method [

20] to iteratively solve and update pressure values. The inner iteration process ends when the residual meets the convergence criterion or the maximum number of inner iterations is reached. The values calculated in the last inner iteration are the results for the new time level. The outer iteration process continues, using the pressure values from the inner iteration to update the fluid properties for the next time level, concluding the outer iteration loop.

Compared to the hydraulic solver, the thermal solver is simpler. It first initializes explicit source terms, then constructs the temperature coefficient matrix. Since the linear system obtained using the fully implicit discretization scheme is solved using a direct method, no iteration is required. The temperature field is updated based on the calculation results, which in turn updates other properties of the thermal components, such as density and specific heat capacity.

After all thermal–hydraulic solvers have completed their calculations, if an update of core reactivity and decay heat power is required, nuclear parameters are further solved by the nuclear solver. First, various reactivity feedback mechanisms—including coolant density feedback, Doppler feedback, fuel axial expansion feedback, cladding axial expansion feedback, and core radial expansion feedback—are evaluated to compute their individual contributions to reactivity, which are then accumulated into the corresponding reactivity terms. Subsequently, a coupled solution of the point kinetics neutron dynamics model and the decay heat model is performed based on the updated total reactivity, yielding key nuclear parameters for the current time step, such as neutron flux density, precursor concentrations for each delayed neutron group, fission product concentrations, and decay heat power fractions.