1. Introduction

To achieve the goal of mitigating global climate change, the 2 °C and 1.5 °C temperature control targets outlined in the Paris Agreement have emerged as an international consensus [

1,

2,

3]. As a central pathway for achieving the climate goals, the low-carbon transition in the energy sector has garnered significant attention worldwide [

4,

5]. This transformation hinges on large-scale deployment of renewable energy to progressively replace traditional fossil fuels, thereby substantially reducing greenhouse gas emissions [

6,

7,

8]. However, the inherent characteristics of renewable energy systems—particularly their lower energy density—coupled with the substantial land requirements of centralized development models [

9,

10], pose constraints on their expansion scale. Consequently, distributed renewable energy systems are increasingly becoming a focal point in energy transition strategies. By leveraging their advantages of flexibility and localization, distributed renewable solutions demonstrate enhanced adaptability to regional energy demands and natural resource endowments, offering novel pathway for advancing low-carbon energy transitions.

Rooftop photovoltaic systems, as a crucial component of distributed renewable energy systems, have garnered substantial attention in recent years [

11]. The operational mechanism involves installing photovoltaic (PV) modules on building rooftops to achieve decentralized solar power generation. This distributed generation paradigm demonstrates significant advantages, including efficient utilization of underutilized rooftop spaces [

3], optimal land resource management through spatial multiplexing, and the capacity of on-site power consumption [

12]. These advantages thereby effectively reduce the transmission losses associated with long-distance electricity delivery. Regarding deployment potential, extensive roof resources across various building typologies—encompassing residential, commercial, and industrial structures—exhibit technical feasibility for PV installation [

8]. The global technical potential of rooftop PV was quantified through geospatial analysis, estimating approximately 36 billion square meters of suitable rooftop surfaces worldwide, equating to 4.7 m

2 per capita, which translates to an annual generation capacity of 8.3 petawatt hours [

13].

Many experiences have accumulated in terms of rooftop PV projects. Germany began to promote rooftop PV projects in the 1990s through implementing subsidy policies and refining technical standards, which motivated widespread adoption among households and enterprises [

14]. In China, systematic development of rooftop PV projects commenced in 2010, primarily driven by government funding and demonstration initiatives. Under the feed-in tariff (FIT) policy, rooftop PV projects experienced rapid growth between 2013 and 2017, with commercial and industrial rooftop PV emerging as the primary growth driver. With the falling back of the subsidy policy from 2018 to 2020, the sector transitioned into grid parity. After 2021, aligned with the dual carbon goals, rooftop PV has become pivotal for both energy transition and rural revitalization strategies [

12]. The National Energy Administration (NEA) of China issued a notice on pilot schemes for county-level distributed rooftop PV (DRPV) projects. Eligible pilot regions must satisfy criteria encompassing abundant rooftop resources, robust power absorption capacity, and compliance with minimum PV installation coverage requirements across diverse building types.

The development of DRPV projects in China, however, has encountered multifaceted challenges, particularly in rural residential promotion campaigns. Key obstacles include inadequate qualification screening of PV enterprises resulting in unqualified equipment. This is coupled with insufficient post-installation maintenance safeguards that undermine residents’ confidence in long-term returns and system safety. The degree of resident acceptance directly determines the implementation efficacy of these projects. Existing research has revealed that farmers’ personal authority exerted the strongest positive influence on PV adoption willingness, followed by authoritative persuasion and PV technology awareness [

15]. Most rural households exhibited risk-averse tendencies and prioritized immediate gains over long-term investments typical of PV systems [

16]. Moreover, limited technical literacy also hindered proactive engagement among the farmers. These intertwined factors foster skepticism and resistance among rural populations, emerging as critical barriers to DRPV project implementation.

This study sought to identify the drivers and barriers affecting rural households’ adoption decisions regarding DRPV systems. On this basis, the ultimate objective is to delineate the critical factors that can inform the design of supportive policies for this project. A mix-methods approach was used to establish a theoretical model that adopting the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model as a basic framework, supplemented by antecedent factors extracted from online textual analysis. Based on the survey data from villages in Jiangsu Province, China, structural equation modeling was used to elucidate the key factors and driving mechanisms of public participation in DRPV projects. The findings provided practical implications for accelerating photovoltaic deployment and advancing rural energy revolution. The contributions of this study were as follows: Through the analysis of multi-source online textual data, this study complements the potential antecedent factors influencing the acceptance of DRPV projects. The key driving factors influencing rural residents’ participation in rooftop PV project were systematically identified and investigated. The findings can provide transferable implications for scaling rural rooftop PV systems across other Chinese provinces and global contexts.

This paper is divided into six sections. Related studies are reviewed in

Section 2.

Section 3 introduces the research methods. The theoretical framework and survey are designed in

Section 4. Then,

Section 5 mainly modifies the original model and tests related paths.

Section 6 discusses the research results. The main conclusions and some policy implications are provided in

Section 7.

2. Literature Review

Current research on the impacts of energy project development predominantly focuses on production-related environmental effects and technological dimensions. The ecological consequences of unconventional oil and gas development, including horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing on natural habitats, were examined in North Dakota [

17]. Beyond technical considerations, local community acceptance emerged as a pivotal determinant for project implementation. Existing studies categorize factors influencing public support into three groups: demographic variables, psychosocial elements, and contextual parameters [

18]. Based on the analysis of 450 farmers near mining areas, it was revealed that individuals with higher educational attainment (24.3%) exhibited stronger support for coal development, primarily due to enhanced employment opportunities and economic benefits [

19]. The Not-In-My-Backyard (NIMBY) phenomenon, originally describing American public aversion to chemical waste facilities, evolved to denote community resistance strategies against undesirable infrastructure siting [

20,

21]. This conceptual framework was extensively applied in conventional energy project studies.

Compared to fossil energy projects, renewable energy technologies demonstrate distinct environmental advantages. However, due to the relatively lower energy density of renewable projects, they are often developed following a distributed mode, which intensifies public interactions. Consequently, public acceptance has emerged as a critical determinant for the large-scale deployment of renewable energy. The complexity of influencing factors for public attitudes toward renewable projects surpasses that of fossil energy counterparts, compounded by greater environmental awareness and diversified public perceptions [

22]. Olve (2025) challenged the simplistic attribution of local resistance to wind power development as mere NIMBYism, emphasizing the oversight of crucial determinants including environmental identity, place attachment, and broader ecological attitudes [

23]. The heightened visibility of solar and wind infrastructure—compared to subsurface energy forms like geothermal or hydropower—amplified the NIMBY effect through intensified landscape alterations [

24]. Additional critical considerations included perceived negative impacts on noise levels, daylight accessibility, and visual aesthetics, which collectively constituted primary determinants of local renewable project acceptance [

25]. Alessandra Scognamiglio (2016) established a direct correlation between community acceptance and photovoltaic landscape integration design, highlighting the underestimated role of aesthetic harmonization in securing local endorsement [

26].

Rural areas, endowed with abundant natural resources, have emerged as indispensable components of renewable energy development. Three predominant renewable energy forms characterize rural energy systems: solar power, hydroelectricity, and bioenergy. Specifically, solar thermal systems provide domestic water heating, hydropower facilities support agricultural processing, and bioenergy serves as cooking fuel [

27]. Currently, the energy transition in rural areas confronts challenges of infrastructural limitations, sociocultural barriers, technological gaps, and financial constraints [

28]. Outka (2021) identified an equity paradox where low-income communities disproportionately bore environmental burdens from large-scale renewable deployment [

29]. Although solar PV systems demonstrated environmental merits and market accessibility that facilitate household adoption, their proliferation faced obstacles including high upfront costs, limited public awareness, technical capacity shortages, and unreliable supply chains. Spatial isolation and financial accessibility further compound adoption challenges, as Aklin (2018) revealed that remote villages’ constrained bank financing options critically influence solar technology uptake [

30]. An Irish case study delineated rural solar PV barriers encompassing cost-prohibitive implementation, land scarcity, resource intermittency, public perception gaps, and data-driven decision-making deficiencies [

31]. This complexity manifested distinctly in China’s context, where Yang (2023) documented the challenges of China’s rural households during adopting a distributed PV system, including inadequate policy incentives, construction-oriented governance neglect, and extended payback periods [

32].

To investigate the psychological motivations and enhancement mechanisms influencing public participation in energy projects, the current literature predominantly employs questionnaire surveys and interviews grounded in theoretical analyses. Venkatesh (2003) systematically compared eight behavioral models [

33]—including the Theory of Reasoned Action [

34], Technology Acceptance Model [

35], and Theory of Planned Behavior [

36]—to develop the UTAUT, which can synthesize their respective advantages. Subsequent applications demonstrate UTAUT’s adaptability to renewable energy contexts: Jain (2022) examined how perceived risks interact with UTAUT’s core determinants in shaping electric vehicle adoption [

37], while Agozie (2023) explored psychological empowerment’s role in renewable technology acceptance and recommendation behaviors [

38]. Notably, UTAUT has also proven effective in analyzing rural residents’ willingness to pay for crop straw energy utilization [

39], confirming its robust extensibility in renewable energy project evaluations.

The proliferation of internet technologies has shifted public discourse to social platforms, making web-text mining an emerging tool for capturing collective sentiment and perceptions. Scholars are increasingly integrating this approach with traditional survey methods to holistically assess public support for renewable energy initiatives—a methodological synergy that addresses conventional limitations while enhancing analytical comprehensiveness through data integration. Jeong (2023) employed Pearson’s correlation analysis on Reddit discussions to quantify inter-energy perception dynamics across five energy types [

40]. Hong (2022) utilized China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) microdata and Probit modeling to demonstrate clean energy’s poverty alleviation effects [

41].

While the existing literature has achieved substantial progress in studying public participation in renewable energy projects, several limitations persist: Current research predominantly focuses on technical and economic determinants, with insufficient exploration of other critical factors influencing public participation behavior. Under the context of advancing county-wide distributed rooftop photovoltaic pilots, studies specifically targeting rural residents as primary stakeholders remained notably underexplored. Few investigations effectively integrate data methodologies into traditional survey frameworks to systematically identify the influencing factors through mining and analyzing online textual data, nor do they construct theoretical models for empirical analysis. This study aimed to address these research gaps through methodological and contextual innovations.

4. Theoretical Framework

The literature review revealed that UTAUT synthesizes the strengths of multiple behavioral theories and has been successfully applied in rural energy technology adoption contexts. Therefore, UTAUT was adopted as the basic theoretical framework of this study. Building on this foundation, the study employed web-based data collection and analytical methods to systematically identify precursor factors influencing the promotion and implementation of DRPV projects. These empirical insights were subsequently integrated with the UTAUT framework to establish the theoretical framework of this research.

4.1. Data Source and Preprocessing

Given the limited channels currently available for rural residents to express their views, obtaining the textual data related to rural DRPV projects posed significant challenges. Therefore, this study adopted a multi-source data collection strategy to acquire more comprehensive and relevant online textual data. To this end, data was collected from popular platforms, including TikTok, Bilibili, Zhihu, and Weibo, using keywords such as “county-wide distributed rooftop PV” and “residential distributed PV systems”. A total of 370,000 text and commentary data points were collected from videos, Q&A threads, and articles spanning January 2014 to February 2024. To mitigate noise in topic modeling, a custom lexicon was developed to filter high-frequency invalid terms prior to the traditional natural language processing method. The NLPir Semantic Analysis Toolkit was then employed for batch segmentation of categorized documents, generating corresponding tokenized outputs for subsequent analytical workflows.

4.2. Theme Modeling Analysis

This study employed the BERTopic topic modeling library to conduct the thematic analysis of the collected online texts. This library integrated the SentenceTransformer model to generate text embeddings, UMAP for dimensionality reduction, HDBSCAN for density-based clustering, and CountVectorizer from scikit-learn for text vectorization, collectively enabling an automated end-to-end process for topic discovery and extraction from textual data. On this basis, the visualize_topics function was adopted to reduce topic quantity until achieving non-overlapping topic clusters in the visualization space. High-relevance topics associated with DRPV systems were systematically selected through this iterative optimization. For voluminous topics exceeding computational tractability, secondary modeling was implemented to enhance analytical precision. The related parameters of the BERTopic model are shown in

Table 1.

This study utilized Word2Vec semantic similarity to validate the quality of topic categorization. When the text data exhibited high similarity with the keywords of a specific topic, it confirmed a strong alignment between the text and that topic. The validation results showed that the average relevance proportion between the text data and their respective topic keywords throughout the study period exceeded 0.8, indicating a high quality of topic classification. On this basis, topic modeling was performed on the collected online texts. The text cases of four representative topics are shown in

Table 2. To achieve a visual representation of topic evolution, the textual keywords were first converted into vector representations based on scikit-learn’s CountVectorizer. Then, the cosine similarity between topic keywords of adjacent time periods was calculated using cosine_similarity. Finally, based on the similarity network relationships of the topics, the Sankey diagram was drawn using boardmix.

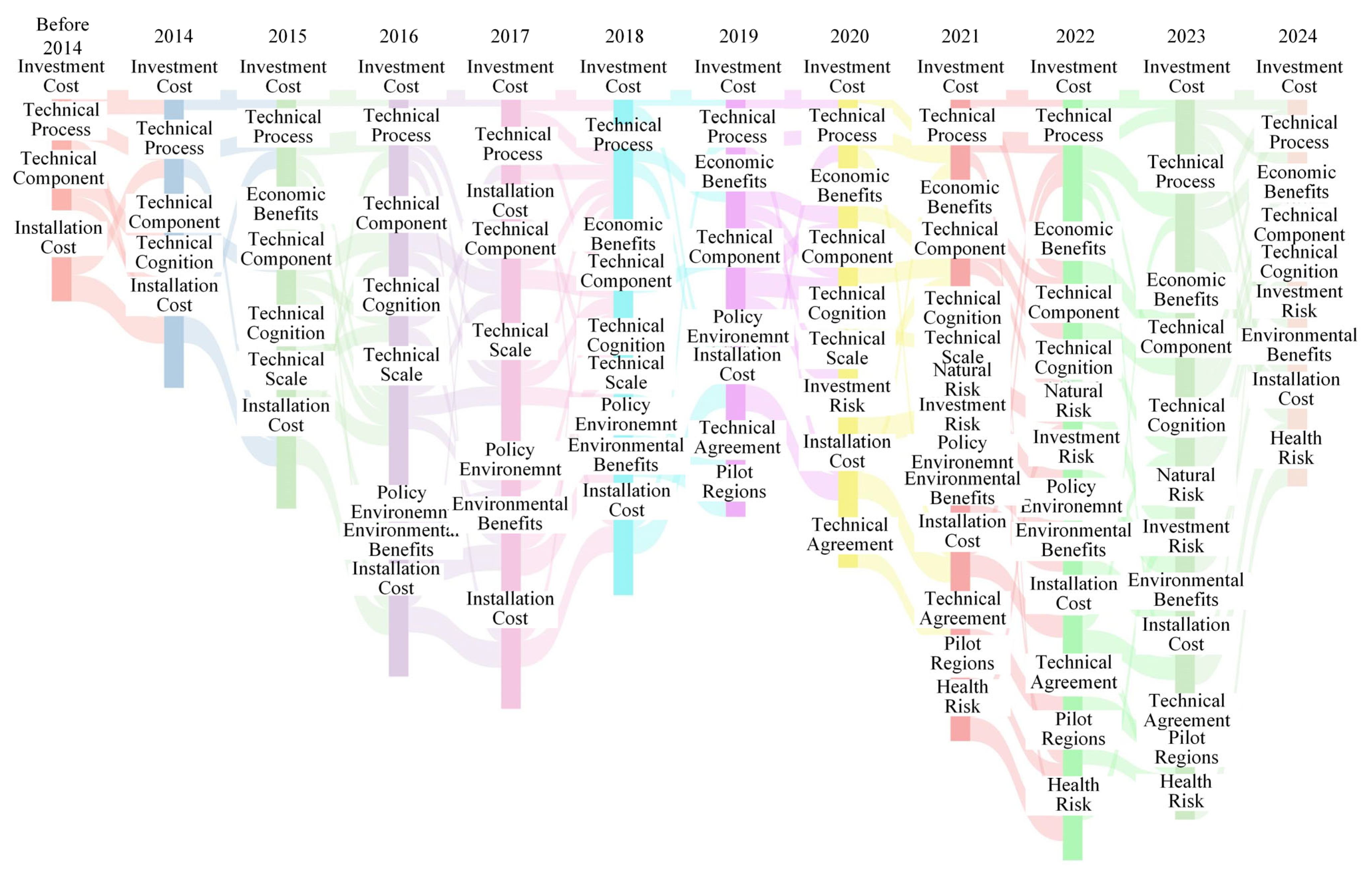

Through systematic analysis of topic evolution in DRPV systems during the 2014–2024 period, this study identified the dynamic patterns of the emergence, convergence, divergence, and obsolescence of the related themes (as illustrated in

Figure 1). The nodes in this Sankey diagram represent different topics related to DRPV systems. Yearly variations are represented by different colors. The findings revealed that technological feasibility and economic returns persistently dominated public discourse. Notably, the diversification of the topics accelerated after 2021—a critical inflection point aligning with county-wide DRPV pilot initiatives. Driven by national promotional campaigns, the understandings of the public in terms of technical specifications, financial incentives, and ancillary considerations, including policy frameworks, environmental externalities, and participatory mechanisms, were enhanced. Given the temporal sensitivity of topic classification, the research prioritized 2023 data (230,000 records) for final thematic categorization and influencing factor identification, as recent datasets better capture contemporary public perceptions of PV project implementation.

4.3. Establishment of Theoretical Framework

The analysis of 2023 web-text data revealed 11 distinct themes associated with DRPV projects, categorized into four perceptual dimensions: cost perception, risk perception, technical perception, and policy perception (as detailed in

Table 3). Cost perception encompasses initial investment and installation expenditures, while risk perception integrates financial uncertainties, environmental hazards, and health-related concerns during system deployment. Technical perception comprises system integration processes, operational cognition, and grid compliance protocols. Policy perception encapsulates economic incentives from feed-in tariffs and environmental externalities quantified through carbon reduction metrics. This multi-dimensional taxonomy can reflect the operational complexities and stakeholder priorities in China’s county-wide DRPV pilot initiatives.

The correspondence relationships were established as follows: cost perception directly influences public expectations of performance expectancy (e.g., financial returns) and effort expectancy (e.g., installation complexity); risk perception modulates performance expectancy by introducing uncertainties in system reliability and safety; technical perception shapes facilitating conditions through evaluations of system interoperability and maintenance protocols; and policy perception amplifies social influence via government-endorsed incentives and community adoption trends.

4.4. Questionnaire Design and Modification

The preliminary interviews revealed a notable gap: residents exhibited limited awareness of DRPV risks and conflated the risk perceptions with cost evaluations—a finding corroborated by survey data where items under “cost perception” and “risk perception” failed to achieve distinct categorization in factor analysis. Given that risk inherently reflects anticipations of potential costs, this study consolidated risk perception into the cost perception dimension, yielding the theoretical Model M1 (

Figure 2). The ellipses represent the latent variables in the theoretical model. Rectangles represent the measurement items for latent variables, where letters denote different latent variables and numbers indicate distinct measurement items.

5. Results

5.1. Investigation Process

The final investigation grounded in theoretical Model M2 adopted the field surveys method, targeting rural residents in Xuzhou and Wuxi, Jiangsu Province. This study employed a multistage stratified random sampling method. First, representative counties were selected within the research area. These counties were then subjected to a second stratification based on village types (e.g., traditional agricultural areas, urban–rural integration zones), from which administrative villages were randomly selected. This sampling strategy was designed to ensure that the sample effectively reflects the characteristics and development levels of the study area, thereby enhancing the generalizability and representativeness of the research findings. Given the inherent knowledge threshold associated with rooftop photovoltaic adoption, the research team strategically targeted young and middle-aged rural residents with foundational educational attainment to enhance data validity during field surveys. A total of 862 questionnaires were collected, with 828 valid responses retained after excluding incomplete or inconsistent entries, yielding a 96% validity rate. Demographic characteristics of the sample, including age distribution, educational attainment, and occupational composition, are systematically detailed in

Table 4.

5.2. Descriptive Analysis

The collected questionnaires revealed a balanced gender distribution (52% male, 48% female). The sample exhibited concentrated age demographics, with 87% of respondents aged 21–40—a core demographic serving as primary decision-makers in households. Given the project’s substantial upfront investment requirements, participants were predominantly drawn from economically advanced regions, where 73.5% reported annual household incomes exceeding CNY 80,000, ensuring baseline financial capacity for DRPV adoption. Concurrently, the sample demonstrated elevated educational attainment, with 74.6% holding bachelor’s degrees. These socioeconomic characteristics collectively validated the sample’s representativeness for investigating decision-making dynamics in DRPV projects.

5.3. Factor Analysis

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 26.0) was employed to assess the reliability and validity of the measurement model. Reliability was evaluated through psychometric indicators to verify the rationality and trustworthiness of the questionnaire design and data collection. Specifically, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was adopted as the reliability metric, where higher values denoted stronger consistency. Established reliability thresholds were applied: α > 0.7 indicated high reliability, while 0.6–0.7 denoted acceptable levels. The overall Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the questionnaire reached 0.815, demonstrating satisfactory internal consistency.

The validity assessment employed Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure to evaluate the structural robustness of the questionnaire. Bartlett’s test yielded a statistically significant p-value of 0.000 with an approximate chi-square value of 10,275.03 and degrees of freedom (df) = 703, while the KMO statistic reached 0.958—exceeding the 0.9 threshold for “excellent suitability” in factor analysis. These metrics collectively confirmed the questionnaire’s optimized validity.

Building upon the initial analysis of the full sample, a systematic examination of dimensionality-specific datasets was also conducted. The results demonstrated robust psychometric properties across all constructs: Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged from 0.713 to 0.862, exceeding the 0.7 threshold for high reliability, while KMO statistics spanned 0.717 to 0.866, which were suitable for factor analysis. The enhanced sample exhibited superior reliability and analytical viability for advanced SEM.

To further assess the model’s internal reliability, composite reliability (CR) indices were introduced. Based on AMOS calculations, the CR values for the nine latent constructs ranged from 0.881 to 0.982, reflecting an ideal level of internal consistency. Additionally, the average variance extracted (AVE) values were analyzed to evaluate the explanatory power of items within each dimension. All latent constructs exhibited AVE values between 0.669 and 0.949, demonstrating robust explanatory capacity of the measurement items for their corresponding variables.

5.4. Optimization of Structural Equation Modeling

Following the validity and reliability assessments, SEM was employed to validate the theoretical framework. Key goodness-of-fit indices were evaluated.

Table 5 reveals suboptimal performance in multiple indices of the initial model, necessitating iterative refinement through path adjustments and error covariance optimization.

Under the constraint of maintaining a moderate number of observed variables, the modified model M2 was refined based on initial model adjustment indices. Some items were excluded from the revised model due to their elevated modification indices. For residual terms exhibiting pronounced collinearity, optimization was achieved by establishing covariance paths between measurement errors, as illustrated in

Figure 3. In this figure, the error terms of the variables and items from e1 to e37 are represented by circles.

The goodness-of-fit analysis of the modified model is summarized in

Table 6, demonstrating significant improvements compared to the initial framework M1. All fit indices were significantly improved and reached ideal levels, indicating that the modified model achieved a satisfactory overall goodness-of-fit. These enhancements confirmed the refined model’s statistical robustness and theoretical validity, making it suitable for subsequent path analysis.

5.5. Path Analysis

Path analysis was conducted based on the modified model. As shown in

Table 7, all paths except the one between effort expectancy and usage intention exhibited statistically significant results, with P-values below 0.001.

First, cost perception demonstrated a path coefficient of −0.81 with performance expectancy, indicating that rural residents’ cost awareness significantly diminished their benefit expectations of distributed rooftop photovoltaic projects. Similarly, the −0.832 coefficient between cost perception and effort expectancy revealed that heightened cost sensitivity reduced anticipated returns on participation efforts.

Second, the analysis revealed a robust path coefficient of 0.738 between policy perception and social influence, indicating that well-designed regulatory frameworks significantly fostered a pro-DRPV social environment. Simultaneously, technical perception exhibited a high path coefficient of 0.848 with facilitating conditions, suggesting that heightened public confidence in DRPV technologies strengthened recognition of institutional support mechanisms.

Third, usage intention was primarily driven by social influence (0.424), followed by effort expectancy (0.301) and performance expectancy (0.253), highlighting the need of policymakers for social mobilization. To enhance public engagement into this project, governments should prioritize fostering community-driven social norms conducive to project diffusion while reducing administrative and financial barriers. Conversely, potential economic benefits from participation were not the primary determinant influencing rural residents’ adoption decisions.

Fourth, the path coefficients were 0.582 for facilitating conditions and 0.347 for usage intention, respectively, on usage behavior, revealing that institutional enablers—specifically grid infrastructure upgrades, financial accessibility mechanisms, and technical assistance programs tailored for DRPV systems exerted a more decisive influence on rural residents’ participation than intrinsic behavioral willingness.

6. Discussion

The empirical results revealed that both facilitating conditions and behavior intention exerted significant positive effects on user participation behavior, with facilitating conditions demonstrating a higher path coefficient (0.582). This underscored that public perception of institutional support mechanisms held greater influence over DRPV adoption decisions compared to intrinsic behavioral willingness. To identify the key measure for enhancing facilitating conditions, a membership degree analysis was conducted. The findings highlight that D4 (“I believe difficulties encountered in operating DRPV systems can be promptly resolved through established support channels”) achieved the highest score (0.69), indicating that robust operational safeguards constituted the cornerstone of public confidence. Meanwhile, D1 (“Understanding DRPV-related incentive policies motivates my participation”) ranked second, emphasizing the critical role of policy visibility and implementation transparency in shaping convenience perceptions. This finding contrasted with Sütterlin (2017), who found that the positive image of a PV project diminished when respondents were informed about the disadvantages [

49].

In addition, performance expectancy, effort expectancy, and social influence also exerted statistically significant positive effects on public participation willingness. Notably, social influence exhibited the highest path coefficient (0.424), underscoring the predominant role of community environment in shaping individuals’ engagement decisions regarding DRPV projects. Further analysis of membership degrees within this dimension revealed elevated scores for indicators C2 (0.69) and C3 (0.69). Specifically, C2 (“Relatives or friends in my social circle have already joined rooftop PV projects”) highlighted the critical impact of peer influence on residents’ adoption behaviors, fostering conformity and imitative decision-making, which was consistent with [

15]. Concurrently, C3 (“Active promotion of DRPV participation by local governments and enterprises in my community”) reflected the efficacy of authoritative advocacy in cultivating a pro-adoption sociopolitical environment. This phenomenon corroborated behavioral economics opinions, where rural residents’ decisions were disproportionately swayed by institutional legitimacy and collective behavioral norms rather than individualized cost–benefit assessments. This finding was corroborated by Enserink (2023), who indicated that a well-designed participatory process for stakeholders contributed to public acceptance of solar power plants [

50].

To further explore pathways for enhancing social influence, this study conducted a membership degree analysis of its antecedent dimension. The results indicated uniformly high membership scores across all three indicators within this dimension. Notably, I1 (“Local governments have established dedicated service centers for residents to consult and learn about rooftop photovoltaic projects”) achieved the highest membership score (0.72), revealing that traditional in-person consultation models demonstrate greater effectiveness than digital outreach in improving rural residents’ policy awareness and participation. Similar results were also identified by Yadav (2020), showing that the rural residents preferred word of mouth, experiential learning, and village-level awareness programs than electronic and print media advertising in the case of decentralized solar photovoltaic projects [

51]. Furthermore, I2 (“Government commitments to provide technical training or professional support”) emerged as a critical trust-building mechanism, particularly given rural populations’ limited technical literacy. The importance of technical support for public acceptance of photovoltaic projects was also verified by [

52].

The analysis of membership degrees across other significant pathways revealed that electricity cost reduction through DRPV participation (A1) and air quality improvement outcomes (A5) were equally prioritized under the performance expectancy dimension, indicating rural residents’ dual emphasis on economic returns and environmental co-benefits when evaluating DRPV projects. Simultaneously, under the effort expectancy dimension, concerns about post-installation operational maintenance difficulty (B4) and transparent cost–benefit accounting mechanisms (B5) emerged as critical factors. These findings implicitly reflect residents’ demand for long-term technical assistance and their risk-averse tendencies driven by perceived investment uncertainties.

7. Conclusions

This study employed a mixed-methods approach integrating online textual data analytics and field surveys to identify critical determinants and enhancement pathways for public participation in DRPV projects. Analysis of online discourse revealed a stepwise increase in public cognition and perceived salience following county-level DRPV pilot initiatives, with investment costs, risk perceptions, technical barriers, and policy frameworks emerging as focal concerns. Empirically, SEM demonstrated that facilitating conditions exerted the strongest influence on rural residents’ participation behavior (0.582***), significantly surpassing behavioral intention (0.347***). Government support, particularly localized technical assistance and streamlined administrative processes, constituted the primary driver of perceived convenience. Concurrently, effort expectancy (0.301**), performance expectancy (0.253***), and social influence (0.424***) collectively enhance participation willingness, with community-driven social norms exhibiting the most potent catalytic effect.

To amplify social influence, policymakers should prioritize on-site consultation hubs and comprehensive lifecycle support systems. Notably, rural participants demonstrated dual-equilibrium valuation of environmental co-benefits and economic returns. These findings underscore the necessity of integrating institutional reliability, community trust-building mechanisms, and multi-stakeholder governance frameworks in DRPV diffusion strategies.

Building upon the preceding analysis and synthesizing systemic challenges observed in county-wide DRPV pilot projects, this study proposes the following policy recommendations:

To amplify policy support and mitigate rural residents’ perceived cost barriers to DRPV participation, targeted fiscal interventions must address their inherent cost sensitivity as risk-averse investors. To enhance their performance expectancy and effort expectancy in DRPV engagement, the government should reduce the cost perception of rural residents through the following measures: equipment purchase subsidies, preferential financing terms, and electricity tariff subsidies.

Project promotion should be intensified to cultivate a conducive social atmosphere for public engagement in constructing new energy systems. Current outreach efforts on green and low-carbon development concepts in rural areas remain insufficient, constraining residents’ willingness to participate in DRPV initiatives. To amplify behavioral intention, strategic communication frameworks should synergize conventional community outreach with digital engagement tactics. Leveraging the persuasive capacity of new media platforms through visually immersive and culturally resonant content formats—aligned with rural users’ digital consumption patterns—can effectively bridge the cognition–action gap.

To optimize project support services and reduce participation barriers for potential users in rural DRPV initiatives, governments must systematically address the complexity of multi-stakeholder coordination and technical implementation procedures. Given the intricate lifecycle phases of DRPV projects, targeted service frameworks should align with rural residents’ evolving needs to enhance their perceived convenience. Pre-implementation campaigns can bridge knowledge gaps in project benefits and contractual obligations, while real-time technical guidance during installation phases mitigates risks of suboptimal system integration. Post-deployment, establishing localized operation and maintenance (O&M) networks ensures sustained performance monitoring and fault resolution, thereby reinforcing user confidence in long-term energy yield stability.

This study integrated methods such as online text mining and textual analysis with traditional survey research approaches, applying them to the practical issue of promoting DRPV systems in rural areas. However, this study has certain limitations. Due to the current lack of dedicated information dissemination channels for rural residents, online data collection was conducted on popular social platforms to construct the theoretical framework. This approach might lead to a discrepancy between the identified factors influencing rural residents’ acceptance of DRPV system and the actual situation. Similarly, the field research primarily selected younger, highly educated rural residents who were more likely to accept DRPV systems, which might limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader rural population. Future research could expand the demographic composition of the participants to explore internal differences in the influencing factors affecting the support for DRPV among various types of rural residents, thereby providing a basis for designing differentiated policy support schemes.