Scenario-Based Spatial Assessment of Solar and Wind Energy Potential in Pakistan Using FUCOM–OWA Integration

Abstract

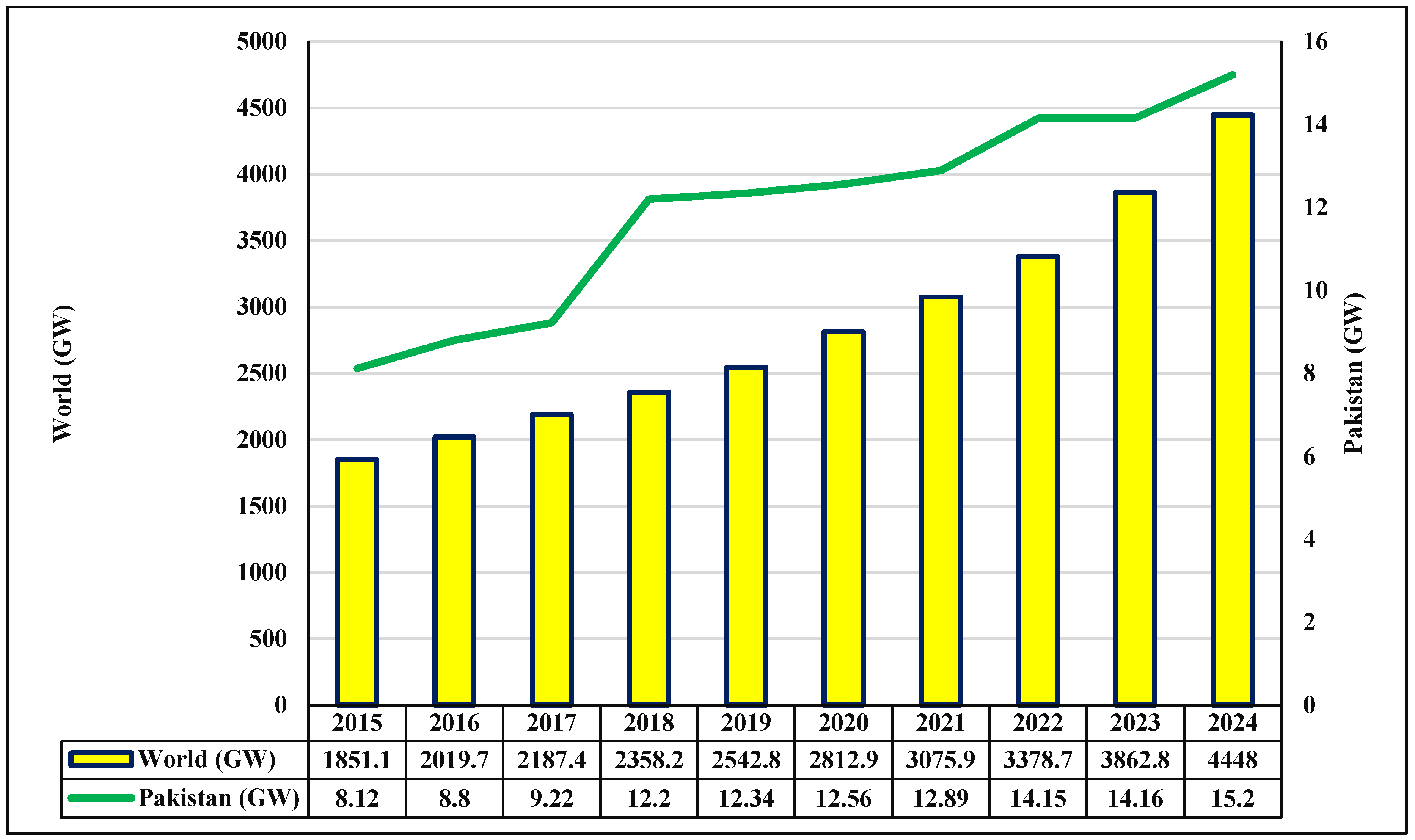

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

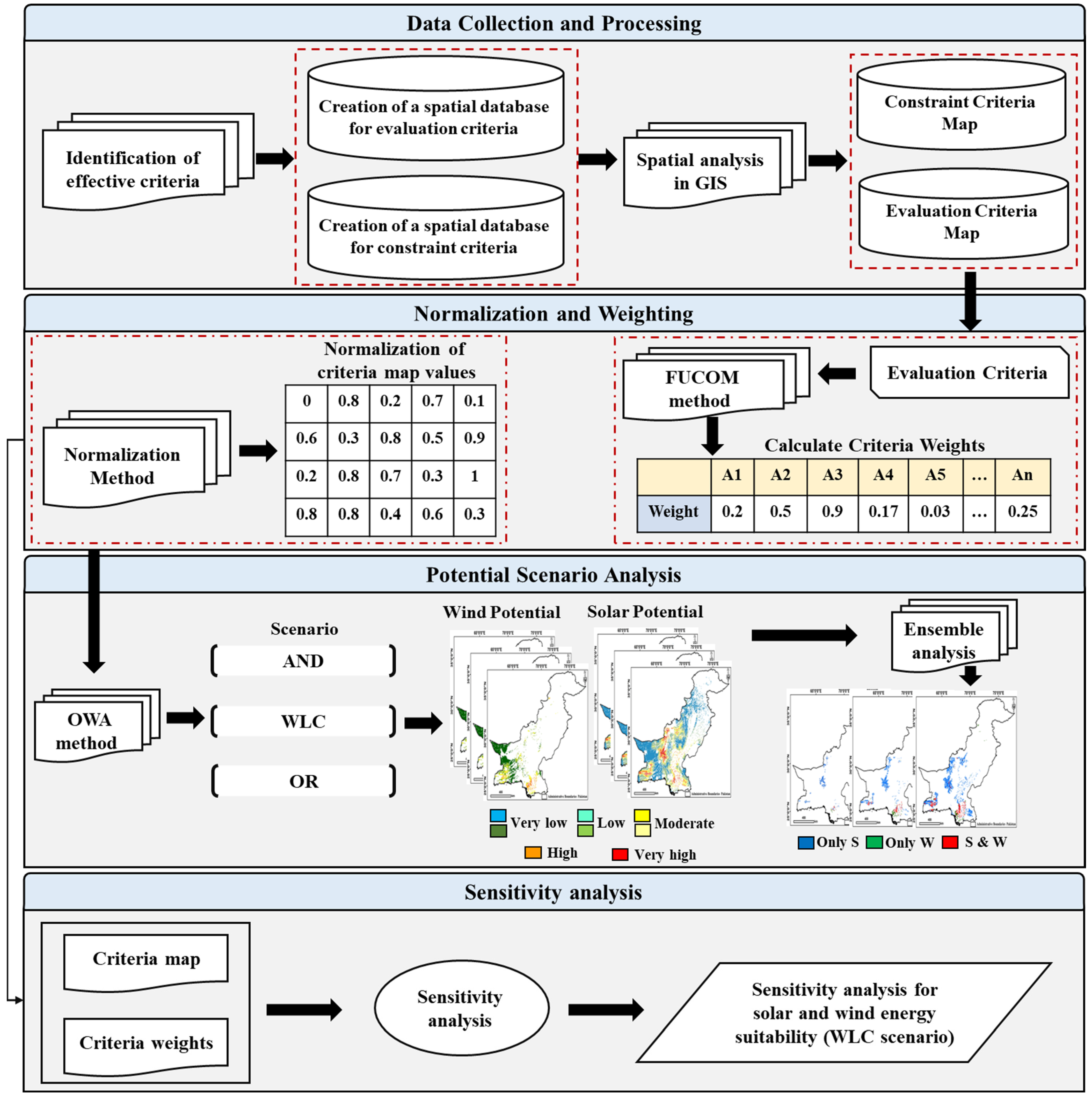

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Identification of Criteria and Constrain Areas

2.3.2. Normalization of Evaluation Criteria

2.3.3. Weight of Criteria

2.3.4. OWA

2.3.5. Sensitivity Analysis

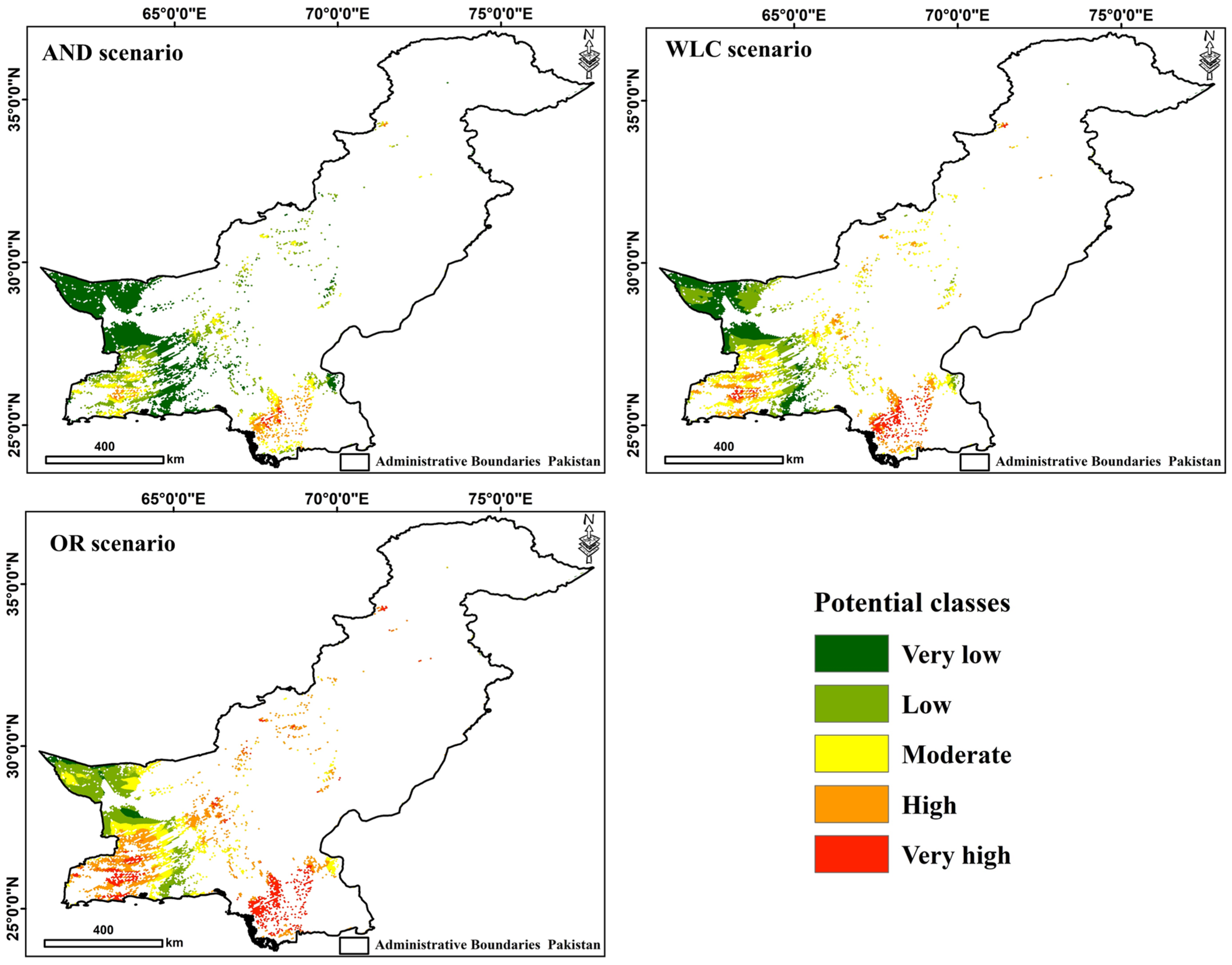

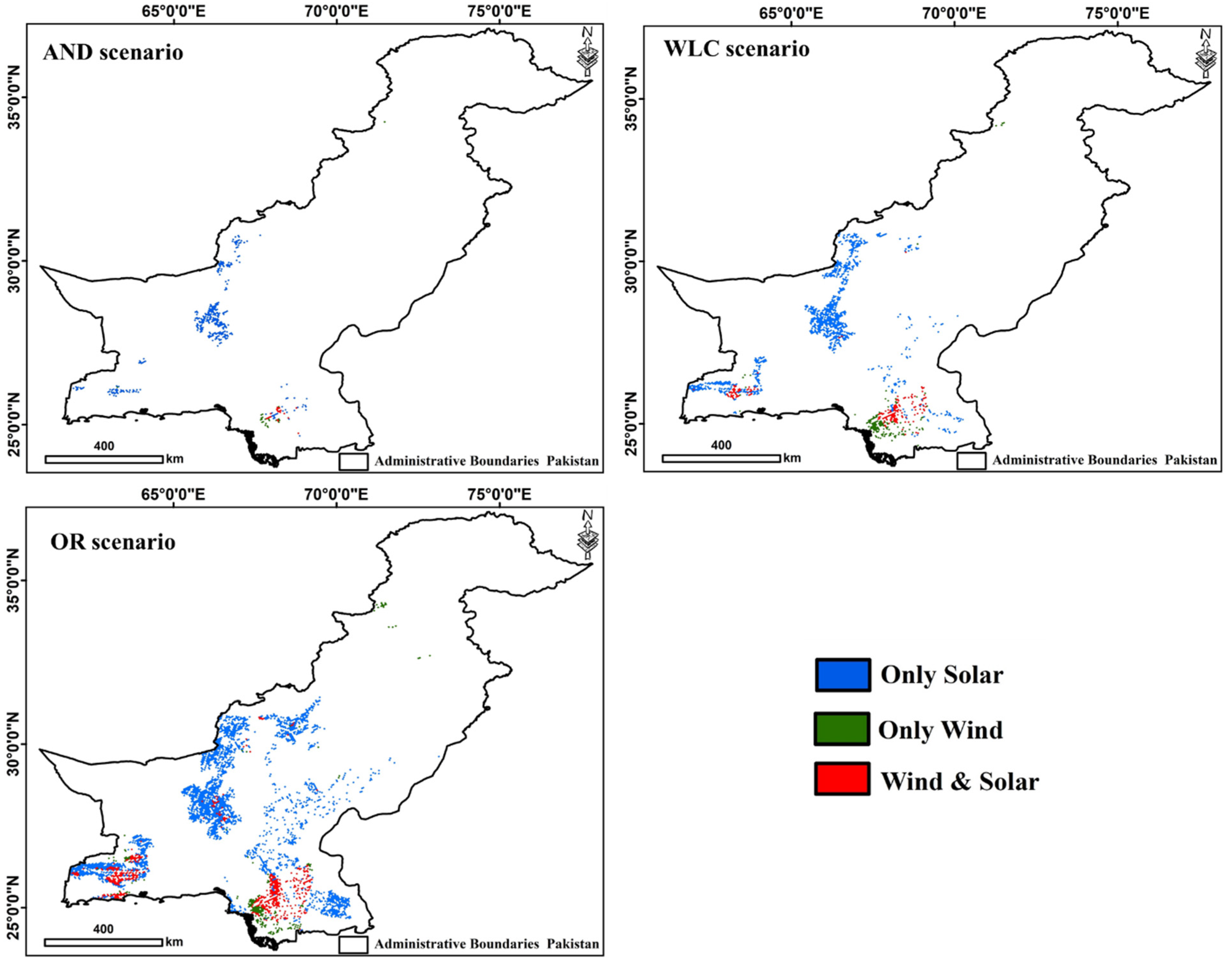

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shorabeh, S.N.; Firozjaei, M.K.; Nematollahi, O.; Firozjaei, H.K.; Jelokhani-Niaraki, M. A risk-based multi-criteria spatial decision analysis for solar power plant site selection in different climates: A case study in Iran. Renew. Energy 2019, 143, 958–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sward, J.A.; Nilson, R.S.; Katkar, V.V.; Stedman, R.C.; Kay, D.L.; Ifft, J.E.; Zhang, K.M. Integrating social considerations in multicriteria decision analysis for utility-scale solar photovoltaic siting. Appl. Energy 2021, 288, 116543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghi, M.; Hajinezhad, A.; Naseri, A.; Noorollahi, Y.; Moosavian, S.F. Multi-criteria decision-making for selecting a solar farm location to supply energy to reverse osmosis devices and produce freshwater using GIS in Iran. Sol. Energy 2023, 253, 501–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Asanza, S.; Quiros-Tortos, J.; Franco, J.F. Optimal site selection for photovoltaic power plants using a GIS-based multi-criteria decision making and spatial overlay with electric load. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 143, 110853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Tong, D.; Davis, S.J.; Qin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, R.; Yang, J.; Yan, X.; Geng, G.; Che, H. Climate change impacts on the extreme power shortage events of wind-solar supply systems worldwide during 1980–2022. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yum, S.-G.; Adhikari, M.D. Suitable site selection for the development of solar based smart hydrogen energy plant in the Gangwon-do region, South Korea using big data: A geospatial approach. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 36295–36313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorabeh, S.N.; Argany, M.; Rabiei, J.; Firozjaei, H.K.; Nematollahi, O. Potential assessment of multi-renewable energy farms establishment using spatial multi-criteria decision analysis: A case study and mapping in Iran. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126318. [Google Scholar]

- REN21. Renewables Global Status Report (GSR 2023); REN21 Secretariat: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Renewable Capacity Statistics 2024; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Kiavarz, M.; Jelokhani-Niaraki, M. Geothermal prospectivity mapping using GIS-based Ordered Weighted Averaging approach: A case study in Japan’s Akita and Iwate provinces. Geothermics 2017, 70, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, M.; Nickravesh, F.; Astaneh, A.D.; Kazemi, N. A risk-based decision-making approach for identifying natural-based tourism potential areas. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2022, 37, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doljak, D.; Stanojević, G.; Miljanović, D. A GIS-MCDA based assessment for siting wind farms and estimation of the technical generation potential for wind power in Serbia. Int. J. Green Energy 2021, 18, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Garni, H.Z.; Awasthi, A. Solar PV power plant site selection using a GIS-AHP based approach with application in Saudi Arabia. Appl. Energy 2017, 206, 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, B.; Banik, P.; Almohamad, H.; Al Dughairi, A.A.; Al-Mutiry, M.; Al Shahrani, H.F.; Abdo, H.G. Land suitability investigation for solar power plant using GIS, AHP and multi-criteria decision approach: A case of megacity Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsiou, M.M.; Theochari, A.P.; Gergatsoulis, D.; Gerakianakis, M.; Baltas, E. Optimal site selection for wind and solar parks in Karpathos Island using a GIS-MCDM model. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boube, B.D.; Bhandari, R.; Saley, M.M.; Adamou, R. Topic: Geospatial evaluation of solar potential for hydrogen production site suitability: GIS-MCDA approach for off-grid and utility or large-scale systems over Niger. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 2393–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsharuk, A.; Łaska, G. The approach to finding locations for wind farms using GIS and MCDA: Case study based on Podlaskie Voivodeship, Poland. Energies 2023, 16, 7107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, A.K.; Al-Dulaimi, O.; Fakhruldeen, H.F.; Sapaev, I.; Jabbar, F.I.; Dawood, I.I.; Khalaf, D.H.; Algburi, S. Multi-criteria GIS-based approach for optimal site selection of solar and wind energy. Unconv. Resour. 2025, 7, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaman, A. A GIS-based multi-criteria decision-making approach (GIS-MCDM) for determination of the most appropriate site selection of onshore wind farm in Adana, Turkey. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2024, 26, 4231–4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifkirne, M.; El Bouhi, H.; Acharki, S.; Pham, Q.B.; Farah, A.; Linh, N.T.T. Multi-criteria GIS-based analysis for mapping suitable sites for onshore wind farms in southeast France. Land 2022, 11, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorabeh, S.N.; Firozjaei, H.K.; Firozjaei, M.K.; Jelokhani-Niaraki, M.; Homaee, M.; Nematollahi, O. The site selection of wind energy power plant using GIS-multi-criteria evaluation from economic perspectives. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Liang, X.; Xiao, C.; Wang, G. Geothermal resource potential assessment utilizing GIS-based multi criteria decision analysis method. Geothermics 2021, 89, 101969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, S. Spatial multi-criteria decision making approach for wind farm site selection: A case study in Balıkesir, Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 192, 114158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, H.; Moradi, S.; Zahedi, R.; Ranjbar, Z. Developed analytic hierarchy process and multi criteria decision support system for wind farm site selection using GIS: A regional-scale application with environmental responsibility. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2024, 22, 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, G.; Koç, A.; van Sark, W. Multi-criteria decision making for solar power-Wind power plant site selection using a GIS-intuitionistic fuzzy-based approach with an application in the Netherlands. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 51, 101307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, M.A.; Yousif, M.; Hassan, M.; Numan, M.; Kazmi, S.A.A. Site suitability for solar and wind energy in developing countries using combination of GIS-AHP; a case study of Pakistan. Renew. Energy 2023, 206, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albraheem, L.; Alabdulkarim, L. Geospatial analysis of solar energy in riyadh using a GIS-AHP-based technique. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokarram, M.; Pourghasemi, H.R.; Mokarram, M.J. A multi-criteria GIS-based model for wind farm site selection with the least impact on environmental pollution using the OWA-ANP method. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 43891–43912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharani, R.; Sivaprakasam, A. A meteorological data set and wind power density from selective locations of Tamil Nadu, India: Implication for installation of wind turbines. Total Environ. Res. Themes 2022, 3, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorollahi, Y.; Senani, A.G.; Fadaei, A.; Simaee, M.; Moltames, R. A framework for GIS-based site selection and technical potential evaluation of PV solar farm using Fuzzy-Boolean logic and AHP multi-criteria decision-making approach. Renew. Energy 2022, 186, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinci, H.; Özalp, A.Y. Optimal site selection for solar photovoltaic power plants using geographical information systems and fuzzy logic approach: A case study in Artvin, Turkey. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyan, M. GIS-based solar farms site selection using analytic hierarchy process (AHP) in Karapinar region, Konya/Turkey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 28, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, H.A.; Shorabeh, S.N. Designing and implementing a location-based model to identify areas suitable for multi-renewable energy development for supplying electricity to agricultural wells. Renew. Energy 2022, 200, 1251–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satkin, M.; Noorollahi, Y.; Abbaspour, M.; Yousefi, H. Multi criteria site selection model for wind-compressed air energy storage power plants in Iran. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 32, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colak, H.E.; Memisoglu, T.; Gercek, Y. Optimal site selection for solar photovoltaic (PV) power plants using GIS and AHP: A case study of Malatya Province, Turkey. Renew. Energy 2020, 149, 565–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocabaldır, C.; Yücel, M.A. GIS-based multicriteria decision analysis for spatial planning of solar photovoltaic power plants in Çanakkale province, Turkey. Renew. Energy 2023, 212, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, A.; Malekmohammadi, B.; Jafari, H.R.; Nasiri, H.; Amini Parsa, V. Land suitability assessment for wind power plant site selection using ANP-DEMATEL in a GIS environment: Case study of Ardabil province, Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2014, 186, 6695–6709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaloo, K.; Ali, T.; Chiu, Y.-R.; Sharifi, A. Optimal site selection for the solar-wind hybrid renewable energy systems in Bangladesh using an integrated GIS-based BWM-fuzzy logic method. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 283, 116899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamanehpour, E. Site selection of wind power plant using multi-criteria decision-making methods in GIS: A case study. Comput. Ecol. Softw. 2017, 7, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Tahri, M.; Hakdaoui, M.; Maanan, M. The evaluation of solar farm locations applying Geographic Information System and Multi-Criteria Decision-Making methods: Case study in southern Morocco. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 51, 1354–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Utility-Scale Solar and Wind Areas: Burkina Faso; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Utility-Scale Solar and Wind Areas: Mauritania; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Can, G.; Kocabaldır, C.; Yücel, M.A. Spatial multi-criteria decision analysis for site selection of wind power plants: A case study. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2024, 46, 4012–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, G.; Riaz, M.; Deveci, M. Wind farm site selection using geographic information system and fuzzy decision making model. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, A.; Astaraei, F.R.; Rajabi, N. GIS-AHP-GAMS based analysis of wind and solar energy integration for addressing energy shortage in industries: A case study. Renew. Energy 2024, 225, 120295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayodele, T.R.; Ogunjuyigbe, A.; Odigie, O.; Munda, J.L. A multi-criteria GIS based model for wind farm site selection using interval type-2 fuzzy analytic hierarchy process: The case study of Nigeria. Appl. Energy 2018, 228, 1853–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadizadeh Shorabeh, S.; Neisany Samany, N.; Abdali, Y. Mapping the potential of solar power plants based on the concept of risk Case study: Razavi Khorasan Province. Sci.-Res. Q. Geogr. Data (SEPEHR) 2019, 28, 129–147. [Google Scholar]

- Zahedi, R.; Ghorbani, M.; Daneshgar, S.; Gitifar, S.; Qezelbigloo, S. Potential measurement of Iran’s western regional wind energy using GIS. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwarzai, M.A.; Nagasaka, K. Utility-scale implementable potential of wind and solar energies for Afghanistan using GIS multi-criteria decision analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfer, T.; Sunak, Y.; Siddique, H.; Madlener, R. Wind farm siting using a spatial Analytic Hierarchy Process approach: A case study of the Städteregion Aachen. Appl. Energy 2016, 163, 222–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.Q. Wind energy in Vietnam: Resource assessment, development status and future implications. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, K.; Dinçer, A.E.; Ayhan, E.N. Exploring flood and erosion risk indices for optimal solar PV site selection and assessing the influence of topographic resolution. Renew. Energy 2023, 216, 119056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.K.; Alqurashi, I.M.; Salama, A.E.; Mohamed, A.F. Investigation the performance of PV solar cells in extremely hot environments. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 13, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-del Río, S.; Lujan, C.; Ferrer, S.; Mereu, R.; Osorio-Gomez, G. GIS-based approach including social considerations for identifying locations for solar and wind power plants. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2025, 84, 101602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boloorani, A.D.; Shorabeh, S.N.; Samany, N.N.; Mousivand, A.; Kazemi, Y.; Jaafarzadeh, N.; Zahedi, A.; Rabiei, J. Vulnerability mapping and risk analysis of sand and dust storms in Ahvaz, IRAN. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 279, 116859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamučar, D.; Stević, Ž.; Sremac, S. A new model for determining weight coefficients of criteria in mcdm models: Full consistency method (fucom). Symmetry 2018, 10, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yager, R.R. On ordered weighted averaging aggregation operators in multicriteria decisionmaking. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 2002, 18, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsari, R.; Nadizadeh Shorabeh, S.; Kouhnavard, M.; Homaee, M.; Arsanjani, J.J. A spatial decision support approach for flood vulnerability analysis in urban areas: A case study of Tehran. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf 2022, 11, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewski, J.; Rinner, C. Multicriteria Decision Analysis in Geographic Information Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, B.; Qiu, H. Comprehensive assessment of ecological risk in southwest Guangxi-Beibu bay based on DPSIR model and OWA-GIS. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewski, J. Integrating multicriteria analysis and geographic information systems: The ordered weighted averaging (OWA) approach. Int. J. Environ. Technol. Manag. 2006, 6, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malczewski, J.; Chapman, T.; Flegel, C.; Walters, D.; Shrubsole, D.; Healy, M.A. GIS–multicriteria evaluation with ordered weighted averaging (OWA): Case study of developing watershed management strategies. Environ. Plan. A 2003, 35, 1769–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firozjaei, M.K.; Nematollahi, O.; Mijani, N.; Shorabeh, S.N.; Firozjaei, H.K.; Toomanian, A. An integrated GIS-based Ordered Weighted Averaging analysis for solar energy evaluation in Iran: Current conditions and future planning. Renew. Energy 2019, 136, 1130–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Escobedo, Q.; Franco, J.A.; Perea-Moreno, A.-J. GIS-based wind and solar power assessment in Central Mexico. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharram, N.A.; Konsowa, A.H.; Shehata, A.I.; El-Maghlany, W.M. Sustainable seascapes: An in-depth analysis of multigeneration plants utilizing supercritical zero liquid discharge desalination and a combined cycle power plant. Alexandria Eng. J. 2025, 118, 523–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Description | Data Type | Data Category | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Horizontal Irradiation (GHI) | GHI is one of the most critical factors for solar power plant site selection, as it represents the amount of solar energy received on a horizontal surface. Higher GHI values indicate greater potential for electricity generation and improved economic viability of the solar project [27]. | Raster | Spatio-temporal | 250 m | Annual average | https://globalsolaratlas.info/map (accessed on 8 January 2017) |

| Wind speed | Wind Speed plays a key role in wind energy production. Since the power output of wind turbines is proportional to the square of wind speed, higher wind speeds significantly increase electricity generation. Therefore, areas with high wind speeds are more suitable for wind farms [28]. | Raster | Spatio-temporal | 250 m | Annual average | https://globalwindatlas.info/en/ (accessed on 19 November 2017) |

| Wind power density | Wind Power Density (WPD) is a key indicator for wind power plant site selection, as it quantifies the available wind energy per unit area at a given height. Higher WPD values indicate stronger and more consistent winds, which lead to higher electricity generation and better economic feasibility of wind energy projects [29]. | Raster | Spatio-temporal | 250 m | Annual average | https://globalwindatlas.info/en/ (accessed on 19 November 2017) |

| Villages | Proximity from villages is important in renewable energy plants; appropriate proximity reduces costs, increases efficiency, promotes local development, and enhances social acceptance of the project [30]. | Vector | Spatial | N/A | Static | https://data.re-explorer.org (accessed on 19 February 2024) |

| Cities | Proximity to cities can reduce energy transmission costs and improve access to communication and management infrastructure. Additionally, local energy demand can enhance the efficiency of solar and wind energy systems [31]. | Vector | Spatial | N/A | Static | https://data.re-explorer.org (accessed on 19 February 2024) |

| Roads | The proximity from roads in solar and wind power plants affects costs and efficiency. Easy access to roads reduces transportation, installation, and maintenance costs. A large distance from roads increases costs and makes operations more difficult [32]. | Vector | Spatial | N/A | Static | https://data.re-explorer.org (accessed on 19 February 2024) |

| Transmission lines | The proximity from transmission lines significantly impacts the costs and efficiency of solar, and wind power plants. Greater distance increases infrastructure costs and energy losses. Proximity to transmission lines reduces costs and improves system efficiency [33]. | Vector | Spatial | N/A | Static | https://data.re-explorer.org (accessed on 19 February 2024) |

| Substation | The distance between solar and wind power plants and the substation should be minimized to reduce transmission costs and energy losses [34]. | Vector | Spatial | N/A | Static | https://data.re-explorer.org (accessed on 19 February 2024) |

| Elevation | Lower elevation can be more suitable for solar and wind energy siting, as it provides easier access and lower costs for infrastructure construction and maintenance [35]. | Raster | Spatial | 30 m | Static | https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 12 February 2021) |

| Slope | Steep slopes in solar and wind power plants cause issues with panel installation and maintenance access. Additionally, they require specialized infrastructure for installation and upkeep [36]. | Raster | Spatial | 30 m | Static | Extracted from SRTM DEM |

| Cropland | Croplands are considered constrained areas due to their negative impact on agricultural production and food security, as well as environmental issues like soil degradation [37]. | Vector | Spatial | 10 m | Static | https://esa-worldcover.org/en (accessed on 2 January 2021) |

| Tree cover | Tree cover is considered an area with constraints because clearing forests for energy projects can lead to biodiversity loss, carbon release, and disruption of ecosystems [36]. | Vector | Spatial | 10 m | Static | https://esa-worldcover.org/en (accessed on 2 January 2021) |

| Airports | Distance to airports is important as it may impose restrictions on equipment installation and structure height, as well as increase transportation costs [38] | Vector | Spatial | N/A | Static | https://data.re-explorer.org (accessed on 19 February 2024) |

| Floodplain zoning | Solar and wind power plants should be located away from floodplains to avoid the risk of flooding, erosion, and damage to equipment [39]. | Vector | Spatial | N/A | Static | https://data.re-explorer.org (accessed on 19 February 2024) |

| Fault lines | Proximity to fault lines in solar and wind power plants increases the risk of damage to equipment due to ground vibrations, which can lead to structural failure and reduced system lifespan [7]. | Vector | Spatial | N/A | Static | https://data.re-explorer.org (accessed on 19 May 2020) |

| Air temperature | Temperature affects the performance of solar and wind power plants. In solar plants, higher temperatures reduce efficiency, while in wind plants, lower temperatures increase energy production, and higher temperatures decrease it [36]. | Raster | Spatio-temporal | 1 km | Annual average | https://globalsolaratlas.info/map (accessed on 27 January 2017) |

| Vegetation density | Vegetation density reduces the efficiency of solar panels due to shading and decreases wind speed in wind power plants. Developing power plants in these areas may harm ecosystems [40]. | Raster | Spatial | 30 m | Static | https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov/ (accessed on 8 August 2024) |

| Protected areas | Protected areas, such as national parks and wildlife reserves, are critical for biodiversity and cultural heritage preservation, so building solar power plants in or near them is restricted or prohibited [41]. | Vector | Spatial | N/A | Static | https://data.re-explorer.org/data-library/layers (accessed on 19 February 2024) |

| Population density | High-density areas, with greater energy needs and established infrastructure, offer favorable conditions for building power plants [42]. | Raster | Spatial | 1 km | Static | https://www.worldpop.org/ (accessed on 9 March 2013) |

| Criteria | Solar | Wind | Type of Impact | Constrains | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHI | * | Maximum | Less than 3.56 kWh/m2 | [42] | |

| Wind speed | * | Maximum | Less than 6 m/s | [41] | |

| Wind power density | * | Maximum | Less than 250 w/m2 | [43] | |

| Villages | * | * | Minimum | Less than 500 m and 1000 m are, respectively, for solar and wind power plants. | [44] |

| Cities | * | * | Minimum | Less than 1000 m and 2000 m are, respectively, for solar and wind power plants. | [25] |

| Roads | * | * | Minimum | Less than 500 m | [45] |

| Transmission lines | * | * | Minimum | Less than 250 m | [46] |

| Substations | * | * | Minimum | Less than 250 m | [47] |

| Elevation | * | * | Minimum | Greater than 2000 m | [48] |

| Slope | * | * | Minimum | Greater than 15% and 20% are, respectively, for wind and solar power plants. | Solar: [49]; Wind: [50] |

| Cropland | * | * | - | Less than 500 m | [41] |

| Tree cover | * | * | - | Less than 1000 m | [1] |

| Airports | * | * | - | Less than 2500 m | Solar: [37]; Wind: [51] |

| Floodplain zoning | * | * | Maximum | Less than 1000 m | [52] |

| Fault lines | * | * | Maximum | Less than 1000 m | [21] |

| Air temperature | * | * | Minimum | - | [53] |

| Vegetation density | * | * | Minimum | Greater than 0.5 | [1] |

| Protected areas | * | * | - | Less than 1000 m | [54] |

| Population density | * | * | Maximum | - | [26] |

| Criteria | Solar Weight | Wind Weight |

|---|---|---|

| GHI | 0.26 | – |

| Wind speed | – | 0.275 |

| Wind power density | – | 0.105 |

| Proximity to Villages | 0.055 | 0.06 |

| Proximity to Cities | 0.065 | 0.07 |

| Proximity to Roads | 0.06 | 0.065 |

| Proximity to Transmission lines | 0.11 | 0.095 |

| Proximity to Substations | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Elevation | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Slope | 0.035 | 0.05 |

| Floodplain zoning | 0.025 | 0.015 |

| Proximity to Fault lines | 0.03 | 0.025 |

| Air temperature | 0.035 | 0.03 |

| Vegetation density | 0.02 | 0.005 |

| Population density | 0.095 | 0.08 |

| Sum | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Potential Classes | AND Scenario | WLC Scenario | OR Scenario | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | % | km2 | % | km2 | % | |

| Very low | 152,408.90 | 43.49 | 57,724.34 | 16.47 | 24,663.20 | 7.04 |

| low | 109,888.50 | 31.36 | 98,652.79 | 28.15 | 64,230.45 | 18.33 |

| Moderate | 51,933.45 | 14.82 | 115,125.70 | 32.85 | 85,133.03 | 24.30 |

| High | 28,170.03 | 8.04 | 54,655.86 | 15.60 | 112,772.40 | 32.18 |

| Very high | 8005.72 | 2.29 | 24,247.91 | 6.93 | 63,607.52 | 18.15 |

| Potential Classes | AND Scenario | WLC Scenario | OR Scenario | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km2 | % | km2 | % | km2 | % | |

| Very low | 56,732.28 | 55.91 | 26,001.33 | 25.63 | 3852.90 | 3.80 |

| low | 21,986.93 | 21.67 | 26,578.11 | 26.19 | 30,292.59 | 29.85 |

| Moderate | 14,373.41 | 14.17 | 25,332.26 | 24.97 | 22,056.14 | 21.74 |

| High | 7405.88 | 7.30 | 16,565.18 | 16.33 | 28,977.53 | 28.6 |

| Very high | 968.98 | 0.95 | 6990.60 | 6.89 | 16,288.32 | 16.05 |

| Criterion | Base Weight | Adjusted Weight (±10%) | R2 (vs. Baseline Map) | Change in High & Very High Suitability Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GHI | 0.26 | 0.234/0.286 | 0.978 | 3.8 |

| Proximity to Villages | 0.055 | 0.0495/0.0605 | 0.982 | 2.1 |

| Proximity to Cities | 0.065 | 0.0585/0.0715 | 0.975 | 2.7 |

| Proximity to Roads | 0.06 | 0.054/0.066 | 0.973 | 2.5 |

| Proximity to Transmission Lines | 0.11 | 0.099/0.121 | 0.968 | 3.4 |

| Proximity to Substations | 0.08 | 0.072/0.088 | 0.971 | 2.9 |

| Elevation | 0.04 | 0.036/0.044 | 0.984 | 1.9 |

| Slope | 0.035 | 0.0315/0.0385 | 0.979 | 2.2 |

| Floodplain Zoning | 0.025 | 0.0225/0.0275 | 0.987 | 2.0 |

| Proximity to Fault Lines | 0.03 | 0.027/0.033 | 0.981 | 2.6 |

| Air Temperature | 0.035 | 0.0315/0.0385 | 0.977 | 2.3 |

| Vegetation Density | 0.02 | 0.018/0.022 | 0.986 | 2.1 |

| Population Density | 0.095 | 0.0855/0.1045 | 0.962 | 4.1 |

| Criterion | Base Weight | Adjusted Weight (±10%) | R2 (vs. Baseline Map) | Change in High & Very High Suitability Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wind Speed | 0.275 | 0.2475/0.3025 | 0.952 | 4.7 |

| Wind Power Density | 0.105 | 0.0945/0.1155 | 0.965 | 3.5 |

| Proximity to Villages | 0.06 | 0.054/0.066 | 0.981 | 2.4 |

| Proximity to Cities | 0.07 | 0.063/0.077 | 0.976 | 2.8 |

| Proximity to Roads | 0.065 | 0.0585/0.0715 | 0.979 | 2.5 |

| Proximity to Transmission Lines | 0.095 | 0.0855/0.1045 | 0.967 | 3.2 |

| Proximity to Substations | 0.08 | 0.072/0.088 | 0.973 | 2.9 |

| Elevation | 0.04 | 0.036/0.044 | 0.985 | 2.0 |

| Slope | 0.05 | 0.045/0.055 | 0.971 | 3.1 |

| Floodplain Zoning | 0.015 | 0.0135/0.0165 | 0.988 | 1.9 |

| Proximity to Fault Lines | 0.025 | 0.0225/0.0275 | 0.982 | 2.3 |

| Air Temperature | 0.03 | 0.027/0.033 | 0.978 | 2.6 |

| Vegetation Density | 0.005 | 0.0045/0.0055 | 0.991 | 2.0 |

| Population Density | 0.08 | 0.072/0.088 | 0.963 | 3.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ateeq, M.; Liu, Q.; Xin, X.; Li, T.; Ahmed, R.; Rahman, Z.U.; Irfan, M. Scenario-Based Spatial Assessment of Solar and Wind Energy Potential in Pakistan Using FUCOM–OWA Integration. Energies 2025, 18, 6478. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246478

Ateeq M, Liu Q, Xin X, Li T, Ahmed R, Rahman ZU, Irfan M. Scenario-Based Spatial Assessment of Solar and Wind Energy Potential in Pakistan Using FUCOM–OWA Integration. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6478. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246478

Chicago/Turabian StyleAteeq, Muhammad, Qinhuo Liu, Xiaozhou Xin, Tianci Li, Raza Ahmed, Zahid Ur Rahman, and Muhammad Irfan. 2025. "Scenario-Based Spatial Assessment of Solar and Wind Energy Potential in Pakistan Using FUCOM–OWA Integration" Energies 18, no. 24: 6478. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246478

APA StyleAteeq, M., Liu, Q., Xin, X., Li, T., Ahmed, R., Rahman, Z. U., & Irfan, M. (2025). Scenario-Based Spatial Assessment of Solar and Wind Energy Potential in Pakistan Using FUCOM–OWA Integration. Energies, 18(24), 6478. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246478