1. Introduction

In the context of global environmental degradation and the pressing need for a transition to low-carbon energy solutions, Park Integrated Energy Systems (PIESs) emerge as a pivotal solution. PIESs are characterized by multi-energy complementarity, cascading energy utilization, enhanced energy efficiency, and increased integration of renewable sources such as photovoltaics and wind power. These features position PIESs as a critical component in achieving carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals [

1,

2]. PV generation exhibits significant environmental sensitivity, resulting in inherent fluctuations and randomness. These characteristics pose challenges to the safe and stable operation of power systems. Therefore, incorporating the uncertainty of photovoltaic output into the optimization and scheduling of PIESs is crucial for ensuring the secure and stable operation of the system.

In describing PV output uncertainty, commonly employed methods primarily encompass several major categories including probabilistic, stochastic process-based, and scenario-based approaches. Probabilistic methods, grounded in the statistical characteristics of historical data, fit PV output to specific probability distributions (such as Beta, log-normal, or hybrid distributions), proving suitable for scenarios with ample data and relatively stable distribution characteristics. Stochastic process methods (such as ARIMA, GARCH, Markov chains, Gaussian processes, etc.) can characterize the correlations within time series, but they often prove inadequate for capturing the non-stationarity and extreme volatility inherent in PV output. Scenario-based approaches, generating extensive samples via Monte Carlo simulations, LHS or Copula methods, then extracting a small number of representative scenarios through clustering, currently represent the most widely applied pathway in integrated energy system scheduling. Furthermore, while deep generative models (GANs, VAE) and machine learning methods such as random forests can fit complex distributions, they suffer from high training costs, strong parameter sensitivity, and insufficient interpretability. Consequently, their application in engineering scheduling remains limited.

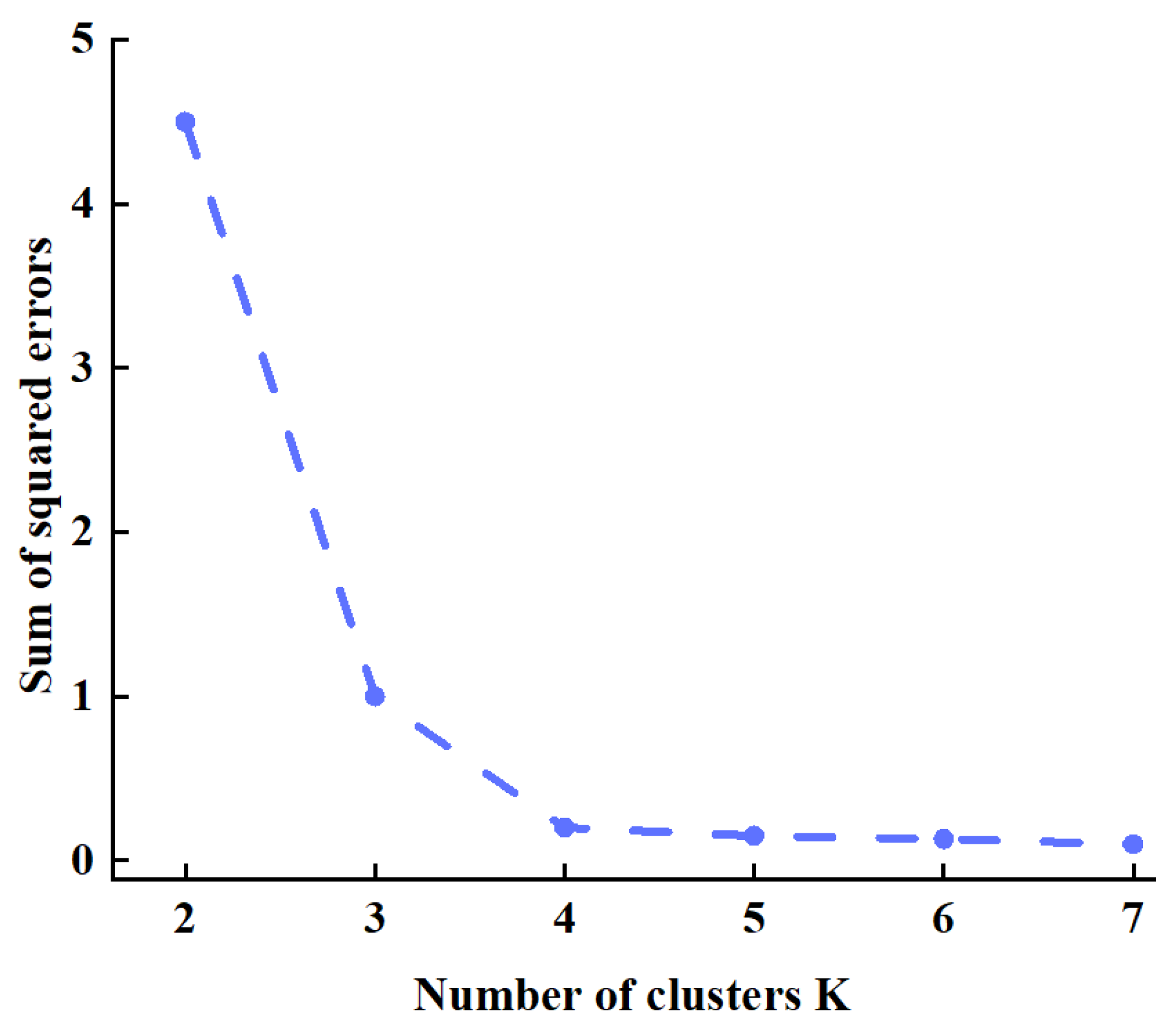

Compared to traditional Monte Carlo sampling, Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) achieves more uniform coverage of values with the same sample size. By partitioning the input variable range into non-overlapping subintervals and sampling within each interval, it ensures balanced distribution of samples, thereby enhancing estimation accuracy and sample utilization efficiency. During the scenario reduction phase, K-means clustering generates a smaller number of well-defined representative scenarios while preserving distributional representativeness. This approach offers good interpretability and significantly reduces the computational scale of the subsequent DRO scheduling model. Compared to complex distribution generation methods such as Copula, GAN, and VAE, K-means offers straightforward computation, intuitive results, and effectively controls the computational scale of the DRO scheduling model, thereby enhancing the convergence efficiency of the CCG algorithm.

In summary, this paper employs LHS for sample generation and combines it with K-means clustering to construct typical photovoltaic scenarios. This approach balances accuracy, interpretability, and algorithmic convergence, rendering it more suitable for the integrated energy system dispatch scenarios described herein.

In PIES optimization scheduling, two main strategies mitigate PV output variability: improving forecasting accuracy and applying advanced optimization techniques. With respect to forecasting, methods can be classified into two categories: physical forecasting and statistical forecasting, based on the differing prediction models [

3]. The physical prediction method is an engineering-based approach that utilizes a comprehensive simulation model encompassing the entire process, from solar irradiation to photovoltaic power generation. While it does not require extensive data, it necessitates accurate photovoltaic parameter information and complex photovoltaic mechanism modeling.

Conversely, the statistical prediction method utilizes big data models to ascertain the correlation between photovoltaic power generation inputs and outputs for forecasting. This data-driven approach exhibits a reduced reliance on physics-based modeling. Reference [

4] examines the spatiotemporal characteristics of PV output and designs a discriminator structure that integrates CNN and LSTM networks. In this structure, the earth mover’s distance is employed as the loss function of the discriminator to generate PV output scenarios. Reference [

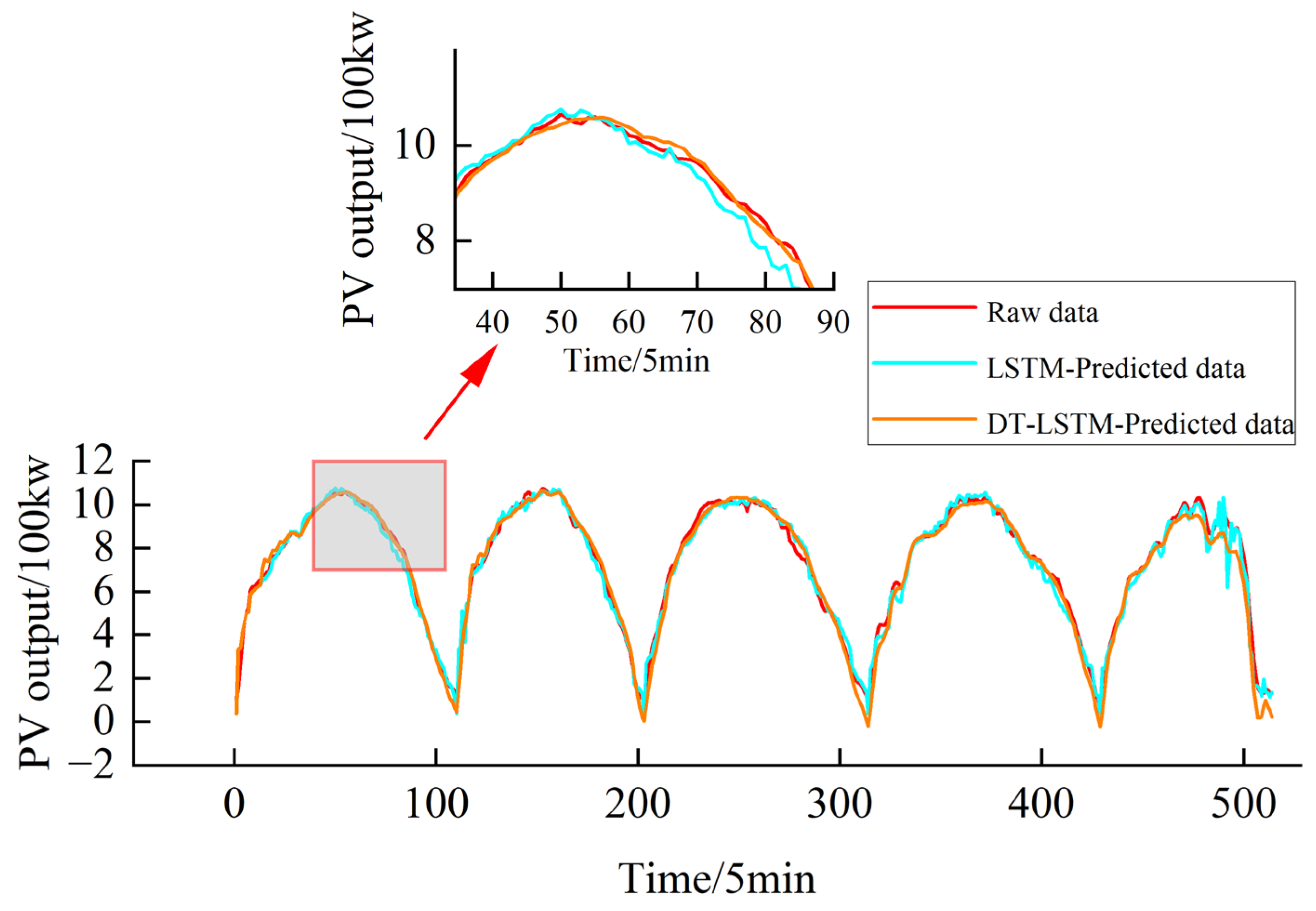

5] addresses alterations in weather patterns caused by significant meteorological fluctuations by proposing a weather classification algorithm based on multi-scale volatility features. A multi-channel structured LSTM modeling approach is employed for comprehensive PV forecasting. While the aforementioned PV forecasting models take into account a variety of parameters, they are fundamentally reliant on pre-trained models for prediction. Reference [

6] employs multiple data-driven models to forecast PV output, including Elastic Net regression, linear regression, random forests, k-nearest neighbors, gradient boosting regressors, lightweight gradient boosting regressors, extreme gradient boosting regressors, and decision tree regressors. This study systematically compares the performance of different machine learning methods in PV forecasting, providing guidance for selecting data-driven predictive models. Reference [

7] proposes a novel fractional-order whale optimization algorithm enhanced support vector regression framework. By incorporating fractional calculus into the whale optimization algorithm, it effectively improves the balance between exploration and exploitation during hyperparameter optimization, yielding significantly enhanced prediction accuracy compared to traditional benchmark models.

The aforementioned PV forecasting studies have thoroughly explored aspects such as feature construction, model selection, and parameter optimization, achieving satisfactory prediction outcomes. However, such methods generally rely on static models trained offline, whose predictive performance becomes fixed after model training. When external conditions change—such as abrupt weather shifts, PV module aging, or increased dust contamination—the original model’s input-output relationship may become inaccurate. Consequently, prediction accuracy degrades over time, rendering the model incapable of continuously adapting to the dynamic variations inherent in real-world operational scenarios [

8].

Therefore, it is necessary to compare the established models with their physical entities in real time, continuously track their accuracy, and perform online corrections when the accuracy requirement is not met. This can be achieved by constructing a digital twin (DT) model of PV, which enables real-time tracking of the physical PV system and iterative correction of the virtual model.

DT principally utilizes historical and real-time data to construct a virtual twin of physical entities, thereby enabling the reflection of their real-time status [

9]. Reference [

10] provides a comprehensive review of the current application status and key advancements of DT technology within the power generation sector, establishing a novel DT classification framework based on temporal scales and application scenarios. As one of the core enabling technologies for DT, machine learning has demonstrated formidable modeling capabilities across multiple energy contexts. In related research, Reference [

11] proposed a novel hybrid quantum genetic algorithm–proximal policy optimization framework. This method combines the efficient global search capability of the quantum genetic algorithm with the adaptive policy update mechanism of proximal policy optimization, thereby achieving automatic parameter tuning and efficient feature space refinement. Reference [

12] constructed a high-precision artificial intelligence diagnostic system successfully applied to wind turbine fault detection, demonstrating outstanding intelligent recognition performance. Reference [

13] employed advanced deep learning image classification models for screening and evaluation, achieving exceptional results in image processing. These studies have yielded significant outcomes in machine learning algorithm design and model construction. Reference [

14] employs advanced analytical modules such as CNN-LSTM and optimization algorithms to construct a proactive cognitive DT system. This system enables forward-looking power grid anomaly identification by predicting future health states and comparing them against real-time monitoring data.

The aforementioned research has achieved significant results in both DT architecture design and intelligent model construction. However, it has primarily focused on application scenarios such as condition monitoring, anomaly detection, or fault identification, without yet integrating DTs with distributed robust scheduling. In other words, how to leverage the real-time calibration capabilities of digital twins to construct uncertainty-driven probabilistic scenarios and serve the distributed robust scheduling of PIESs remains an unaddressed gap in current research.

The PV DT model constructed herein possesses not only self-learning capabilities but also dynamically calibrates itself based on real-time data, thereby ensuring its predictive accuracy remains consistently stable over time. This characteristic provides enhanced adaptability and reliability for PV forecasting. Furthermore, the DT model delivers more precise initial probability information for distributed robust scheduling, thereby improving the economic efficiency and robustness of the scheduling model when confronting PV output uncertainty.

With respect to the optimization techniques employed, the scheduling methods of PIES can be classified according to their uncertainty modeling approaches. These approaches include fuzzy optimization [

15], stochastic optimization [

16], robust optimization [

17], and distributionally robust optimization (DRO) [

18]. Fuzzy optimization and stochastic optimization are relatively dependent on subjective factors in the selection of related functions. While these systems offer notable economic advantages, their inherent fragility poses significant challenges to the reliable and secure operation of the system. Conversely, robust optimization addresses the worst-case scenarios, ensuring system resilience but often resulting in overly conservative outcomes and significant economic expenditures. DRO integrates the advantages of both stochastic optimization and robust optimization. The primary focus of this study is the uncertainty surrounding parameters in probability distribution functions. The objective is to ascertain the probability distribution of PV output under the most unfavorable conditions. Reference [

19] established a DRO scheduling model for PIESs based on historical wind and solar data. In comparison with alternative optimization methodologies, DRO strikes a balance between economic efficiency and robustness. However, the initial scenarios required for its implementation are often challenging to obtain. Consequently, this paper employs a photovoltaic digital twin model, incorporates error, and utilizes Latin hypercube sampling and k-means clustering to provide typical PV output scenarios and corresponding scenario probabilities for DRO scheduling.

To overcome such problems and challenges, this paper proposes a DRO scheduling approach for PIESs based on DT. First, a DT model of PV is established, and on this basis, initial PV output scenarios are generated to characterize output uncertainty using Latin hypercube sampling and k-means clustering. Then, with the minimization of the total system operating cost and curtailment cost as the optimization objective, a two-stage distributionally robust optimization model is constructed considering the constraints of various equipment in PIES. To demonstrate the effectiveness and engineering applicability of the proposed methodology, a PV DT model and the corresponding DRO scheduling framework were implemented and validated at a representative site within an industrial park in Shanxi Province.

3. Distributed Robust Scheduling Model for Integrated Energy Systems in Industrial Parks

The overall logic of the distributed robust scheduling model for PIES is demonstrated in

Figure 4. Firstly, a digital twin model for photovoltaic generation is established, along with a basic PIES scheduling model that aims to minimize system operational costs without considering the uncertainty in photovoltaic output. As a consequence of photovoltaic power forecasting, errors are introduced, and multiple scenarios are generated to match the error distribution. These scenarios are then reduced to a small number of representative ones, each assigned a corresponding probability. The inherent variability in photovoltaic output is then integrated into the fundamental PIES scheduling model, thereby transforming it into a distributed, robust scheduling model for PIES. Ultimately, the CCG algorithm is employed to solve and obtain the final distributed robust scheduling solution for PIES.

3.1. Dispatch Model for Integrated Energy Systems in Industrial Parks

(1) Objective function

This section first constructs the basic scheduling model for PIES without considering the uncertainty in PV power output, which serves as the foundation for the subsequent distributed scheduling. The objective function of this model is to minimize system operational costs and curtailment costs, as shown in the following equation.

where

represents the system operating cost, and

represents the curtailment cost. The system operating cost comprises the start-up and shutdown costs of conventional generating units, and the power generation cost, denoted by

and, respectively.

The generation cost can be represented by the corresponding fuel coefficient.

The generation costs for conventional units are expressed as follows:

where

and

represent the equivalent nonlinear and linear power generation cost functions for the

j-th conventional unit, respectively.

denote fixed costs for the j-th unit generators such as maintenance expenses.

denotes the total number of time periods.

denote the total number of units for conventional.

denote the power output of the

j-th unit for conventional units at time

.

In order to address potential fluctuations, conventional units incur corresponding startup and shutdown costs.

The startup and shutdown costs are given as

where

and

represent the startup and shutdown costs for conventional units, while

and

denote the startup/shutdown status flags of the

j-th unit for conventional units at time

. When

equals 1 and

equals 0, it indicates startup; when

equals 1 and

equals 0, it indicates shutdown.

In order to achieve greater decarbonization, it is essential to prioritize the maximization of PV power accommodation. Consequently, the financial implications of PV curtailment are integrated into the objective function.

where

denotes the number of PV units,

represents the linear coefficient of curtailment costs,

and

denote the actual output and predicted output of the

j-th PV unit at time

, respectively.

(2) Constraints

To ensure the safe and stable operation of the system and to account for the inherent characteristics of various devices, the PIES scheduling must satisfy a set of constraint conditions. The power balance constraints include both electrical power balance and thermal power balance.

The electrical power balance constraint is given as

where

and

represent the number of electrical energy storage units and electric boilers, respectively.

denotes the

j-th energy storage charge/discharge indicator at time, where −1 indicates charging and +1 indicates discharging.

is the output value of the

j-th electrical energy storage unit at time

.

is the electrical power consumed by the

j-th electric boiler at time

.

is the electrical load at time

.

The thermal power balance constraint is given as

where

denotes the thermal output of the

j-th thermal energy storage unit at time

;

is the thermal output of the

j-th electric boiler at time

; and

represents the thermal load at time

.

Conventional units must satisfy corresponding electrical power constraints and ramping constraints.

Electrical power constraints are defined as:

where

and

represent the upper and lower limits of the output of the

j-th unit, respectively.

Ramp rate constraints:

where

denotes the climbing rate of a conventional unit, and

denotes the sliding rate.

The start-up and shutdown status of conventional units is represented by a single state variable, namely:

The output of the electric boiler must also meet the upper and lower limit requirements and coupling requirements, with its coupling efficiency also being a fixed value:

where

and

represent the upper and lower limits of the output for the j-th electric boiler unit, respectively, and

denotes the electrical-to-thermal conversion efficiency of the electric boiler.

Photovoltaic output must meet its upper and lower limit requirements:

where

and

represent the upper and lower limits of the

j-th photovoltaic output, respectively.

The operation of energy storage systems must satisfy the mutually exclusive charging and discharging requirement, as well as the upper and lower limits of charging/discharging power and storage capacity. In addition, the initial and final states of the storage system must be consistent. Since the operational principles of electrical and thermal energy storage are similar, this paper takes electrical energy storage as an example, and the thermal energy storage model is therefore not presented in detail.

The electrical energy storage constraints as follows:

where

/

are the energy storage charge/discharge status bits. A value of 1 indicates charging/discharging, while a value of 0 indicates no charging/discharging.

and

denote the charging/discharging power of the

j-th energy storage unit at time

.

,

,

, and

represent the upper and lower limits of charging/discharging for the

j-th unit.

and

are the charging/discharging conversion coefficients.

indicates the capacity of the

j-th unit at time

.

and

denote the initial and final storage capacities of the

j-th unit.

To simplify the analysis, the basic scheduling model underlying the above construction can be expressed by the following equation:

where

represents deterministic variables that are not affected by PV forecast errors, including the start-up and shutdown status of conventional units as well as the charging and discharging states of electrical and thermal energy storage systems.

represents real-time adjustable variables that vary with PV output, including the power outputs of various units.

denotes the equivalent start-up and shutdown costs coefficient, while

represents the generation cost and the cost associated with PV curtailment.

is the PV forecast vector.

,

,

,

,

, and

are coefficient matrices.

Equation (22) represents the objective function, while Equations (23)–(26) correspond to the constraint conditions. Equation (23) describes the start-up/shutdown and charging/discharging state constraints, corresponding to Equations (18) and (21). Equation (24) represents the upper limit constraint of PV output, corresponding to Equation (20). Equations (25) and (26) encompass all the remaining equality and inequality constraints that must be satisfied, including power balance constraints.

3.2. Distributed Robust Dispatch Model for Integrated Energy Systems in Industrial Parks

Even after prediction using DT, PV output still contains uncertainties. Therefore, a distributionally robust approach is adopted to account for this portion of uncertainty. In the previous section, a basic scheduling model was established; based on this model, a distributionally robust model will be constructed.

Distributed robust models combine robust optimization methods with stochastic optimization methods, deriving scheduling schemes by seeking the most unfavorable probability distribution of PV output.

To facilitate analysis and solution, this paper constructs a two-stage DRO scheduling framework: in the first stage, decision variable remains constant regardless of actual scenario variations; in the second stage, decision variable is adjusted according to different scenarios to describe feasible scheduling strategies under the worst-case probability distribution. This model identifies optimal scheduling solutions that balance economic efficiency and robustness by searching for the probability distribution of the worst-case scenario within the uncertainty set.

Building upon this foundation, Equation (22) can be further modified as follows:

where

and

denote the feasible domains of

and

formed by their respective constraints;

represents the probability of the scenario occurring;

denotes the set of feasible domains for the scenario’s probability distribution.

Equation (27) represents the two-stage distributed robust model constructed in this paper. In the first stage, remains constant regardless of actual scenario changes, while represents the quantity subject to change in the second stage. This primarily involves probabilistically modeling the worst-case scenario to identify an optimized value that meets economic objectives.

To identify the worst-case probability distribution of the scenarios, the most straightforward method is to enumerate the probability values of each scenario and iterate. However, to ensure the reasonableness of the probability distribution, two additional constraints—the

norm and

norm—are imposed on

based on its initial value. The initial value

is obtained from the PV output predicted by the digital twin in

Section 2, after clustering and reduction.

To avoid the occurrence of extreme conditions, both the

norm and the

norm must be considered simultaneously. Their constraints can be expressed as

where

and

represent the probability-allowed deviation values under the

norm and

norm conditions, respectively.

According to Reference [

28], the confidence constraints of

and

satisfy

where

is the opportunity constraint function.

The right-hand side of Equations (29) and (30) can also be expressed in terms of the confidence levels and of the uncertainties.

Consequently,

and

can be determined as

It is worth noting that Equations (29) and (30) also contain absolute value variables, which complicate the solution process. Therefore, two auxiliary variables

and

are introduced into these constraints. This allows the absolute values to be transformed into

where

and

denote the positive and negative offsets of the initial values.

Similarly, it can be obtained that:

where

and

are also auxiliary variables.

3.3. Model Solution

Equation (27) can be considered as a min-max-min problem. For this problem structure, the column-and-constraint generation (CCG) algorithm is highly suitable. This is due to the fact that it facilitates the decomposition of the original problem into a primary problem and a series of subsidiary problems. The approach entails the alternating resolution of the primary and secondary problems, thereby circumventing the computational explosion that would otherwise ensue from the direct solution of a large-scale model. This, in turn, enhances solution efficiency. The solution process to this problem is outlined below:

(1) Main Problem (MP)

MP lies in obtaining variables that satisfy optimal economic conditions under the most adverse probability distributions. It provides a lower bound (LB) for model Equation (27), as shown in Equation (34).

where

is the number of iterations.

(2) Subproblem (SP)

The subproblem essentially involves identifying the most unfavorable probability distribution while fixing the variable

, thereby providing an upper bound (UB) for Equation (27) to facilitate further iterative computation in the main problem. Specifically, as demonstrated in Equation (35):

First set and . Then fix to solve the main problem Equation (27) to obtain . Update the value of such that . At this point, fix the obtained and solve the subproblem Equation (28) to obtain a new value. Update the value of such that .

(3) After obtaining the new value, solve Equation (35) to obtain the new value, and update the values of and . Repeat this process until .

It is posited that, by means of this iterative, alternating solution process, an optimal scheduling scheme that satisfies economic efficiency can ultimately be obtained.