A Review of Filters for Conducted Electromagnetic Interference Suppression in Converters

Abstract

1. Introduction

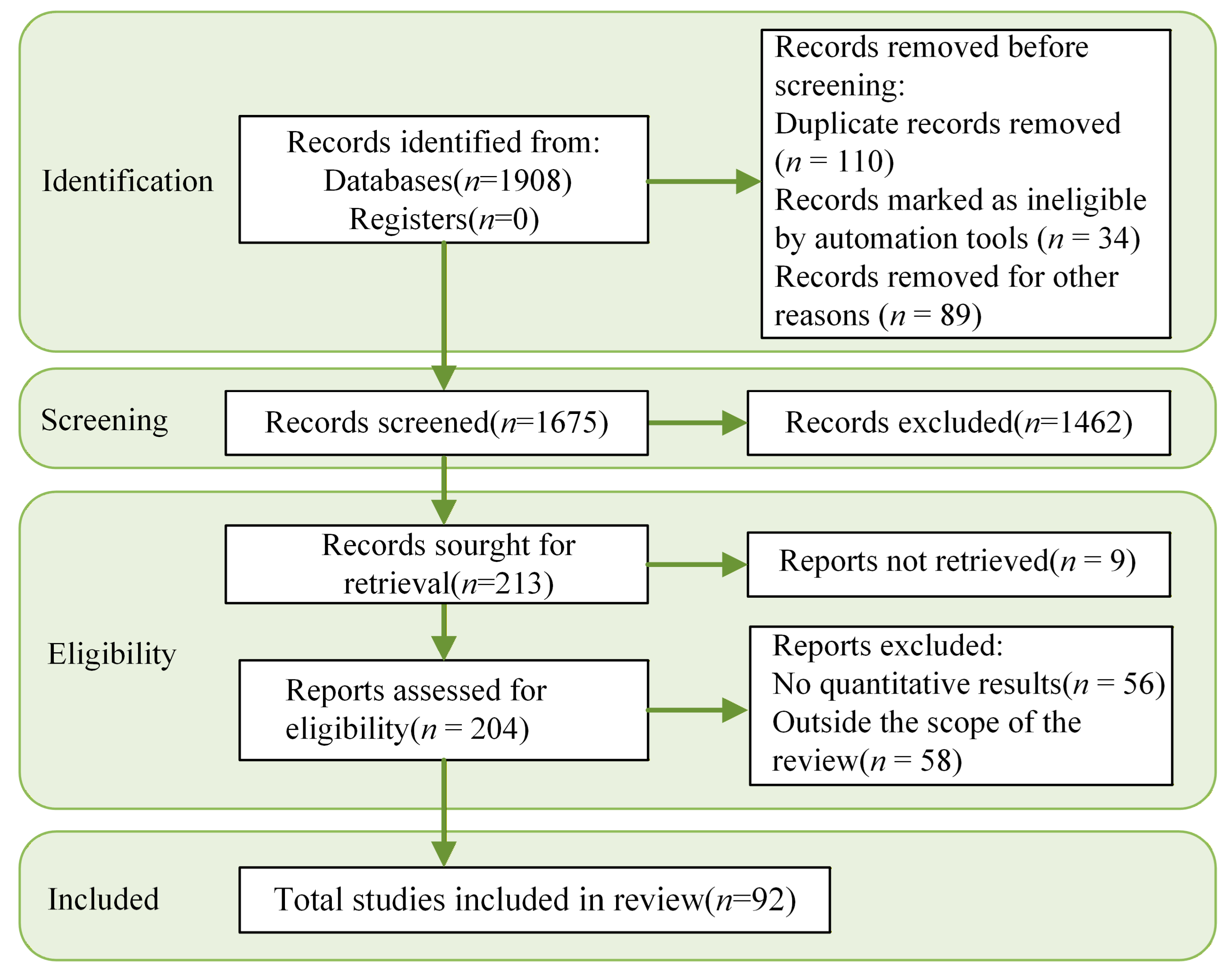

2. Methodology

2.1. Reference Database

2.2. Selection Criteria

- (1)

- The research topic should pertain to filter design.

- (2)

- The abstract must include references to electromagnetic interference or electromagnetic compatibility.

- (3)

- Priority shall be given to original research articles and conference papers to ensure data originality and reliability.

- (4)

- Non-original research literature such as review articles, book chapters, editorials, and commentaries shall be excluded.

2.3. PRISMA Protocol

3. Principles and Current Development Status of PEFs

3.1. Basic Components of PEFs

- (1)

- Obtain the electromagnetic interference spectrum of the equipment through measurement or prediction, including both DM and CM interference.

- (2)

- Select an appropriate filter topology.

- (3)

- Design the filter’s insertion loss and determine its cutoff frequency.

- (4)

- Determine the parameters of each filter component based on the cutoff frequency and safety regulations.

- (5)

- Further optimize the filter to ensure its applicability in practical scenarios.

3.2. Methodology for PEFs Topology Selection

3.3. Development Status of PEFs

4. Principles and Current Development Status of AEFs

4.1. Introduction of Analog AEFs

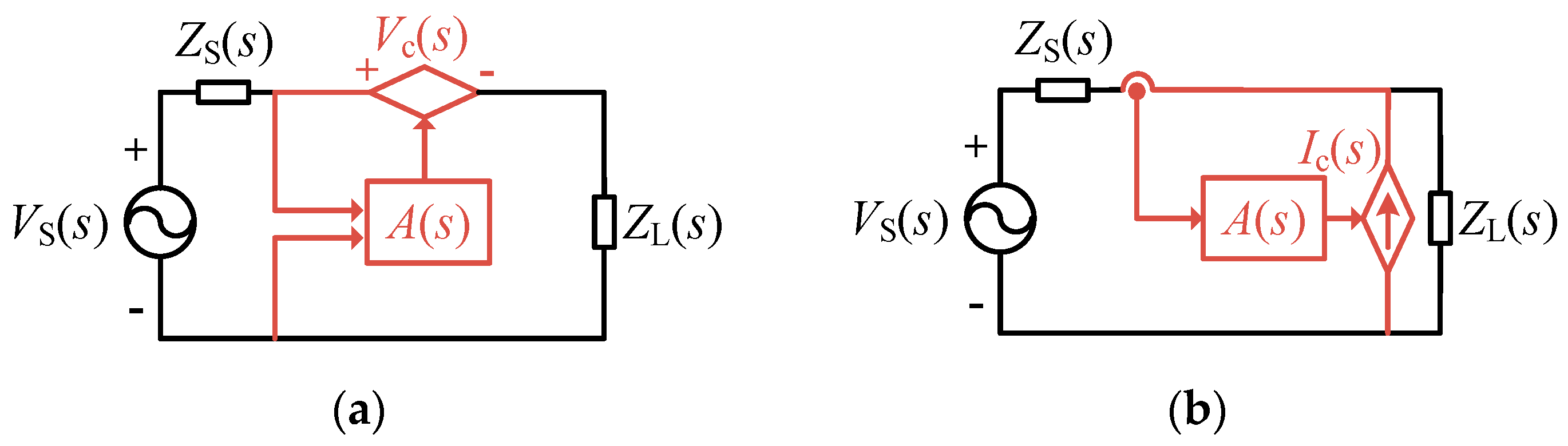

4.1.1. Basic Topologies of AEFs

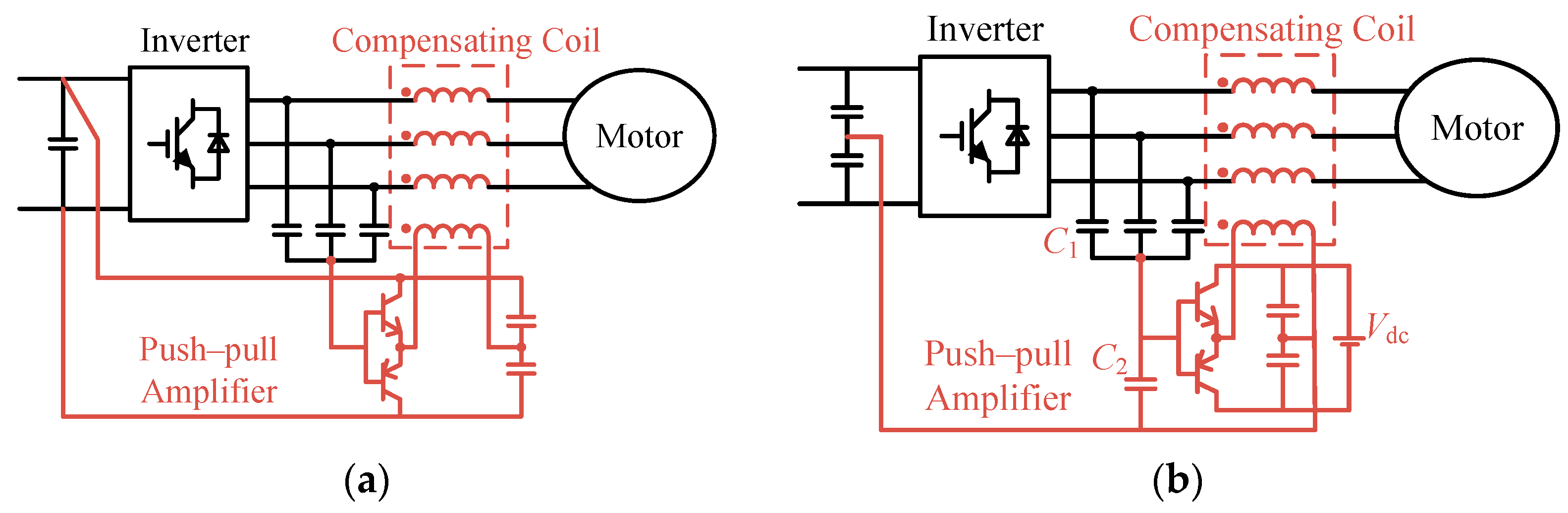

4.1.2. Research Status of Analog AEFs

4.2. Introduction of DAEFs

5. Integrated Electromagnetic EMI Filters

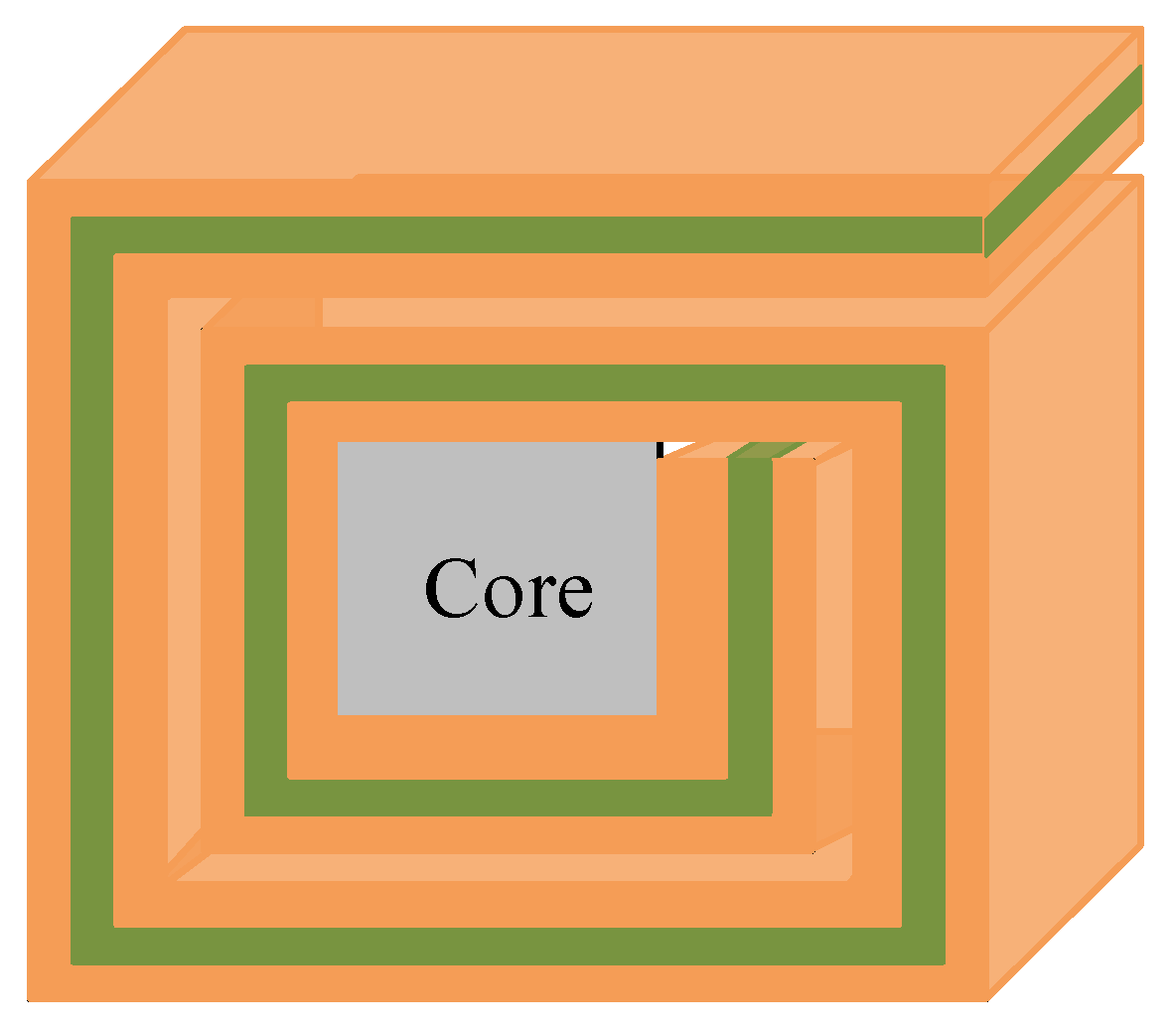

5.1. Planar Electromagnetic IEFs

5.2. FMLFs Electromagnetic IEFs

6. Comparative Analysis of Different Types of EMI Filters

- (1)

- From the cost perspective, PEFs are mature and simple in design, resulting in low research and development (R&D) expenses. The passive components that constitute PEFs, such as capacitors and inductors, are also relatively inexpensive, making PEFs the most cost-effective solution. Designing analog AEFs requires consideration of factors such as stability, making the process more challenging. Additionally, the active components used are more expensive than passive components, resulting in higher costs for AEFs compared to standard PEFs. The cost of designing DAEFs is higher. Electromagnetic IEFs are still in the R&D phase, with costs primarily stemming from R&D as well as integration processes. Lower-cost production may be achievable in the future.

- (2)

- In terms of volume and weight, PEFs emerged earliest and exhibit the largest dimensions and heaviest weight. To address miniaturization in power electronics, researchers began exploring AEFs in the 1980s, which generally feature smaller volumes than PEFs. Electromagnetic IEFs have only been studied in the past two decades, achieving even smaller volumes than analog AEFs. Particularly, FMLFs electromagnetic IEFs enable significant reduction in filter size.

- (3)

- Regarding filtering performance and reliability, PEFs provide stable performance but are inherently inflexible due to fixed parameters, leading to over-design. AEFs offer superior adaptability through active compensation but face stability risks. Electromagnetic IEFs, as passive devices, maintain the inherent stability of PEFs.

7. Conclusions and Future Prospects

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- She, X.; Huang, A.Q.; Lucía, Ó.; Ozpineci, B. Review of Silicon Carbide Power Devices and Their Applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 8193–8205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, F.-Y.; Chen, D.Y.; Wu, Y.-P.; Chen, Y.-T. A Procedure for Designing EMI Filters for AC Line Applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 1996, 11, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, K.; Oruganti, R.; Viswanathan, K.; Ng, S.P. A Metric for Evaluating the EMI Spectra of Power Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2008, 23, 2075–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, L.M. Noise Source Equivalent Circuit Model for Off-Line Converters and Its Use in Input Filter Design. In Proceedings of the 1983 IEEE International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility, Arlington, VA, USA, 23–25 August 1983; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Zhang, Z.; Zhan, J.; Gong, C. An Optimization Method to Enhance the Accuracy of Noise Source Impedance Extraction Based on the Insertion Loss Method. Micromachines 2025, 16, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, D.Y.; Nave, M.J.; Sable, D. Measurement of Noise Source Impedance of Off-Line Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2000, 15, 820–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, K.Y.; Deng, J. Measurement of Noise Source Impedance of SMPS Using a Two Probes Approach. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2004, 19, 862–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; See, K.Y. Characterization of RF Noise Source Impedance for Switched Mode Power Supply. In Proceedings of the 2006 17th International Zurich Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility, Singapore, 27 February–3 March 2006; pp. 537–540. [Google Scholar]

- Bo, Z.; Min, Z.; Zhiming, F.; Limin, S.; Min, Y. An Improved Dual-Probe Approach to Measure Noise Source Impedance. In Proceedings of the 2010 Asia-Pacific International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility, Beijing, China, 12–16 April 2010; pp. 214–217. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, D.; Jeong, S.; Kweon, H.S.; Kwack, Y.H.; Kim, J. Extraction of Noise Source Impedance of an Operating High-Power Converter with High-EMI Noises by Increasing SNR Using an Amplifier. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility—EMC Europe, Brugge, Belgium, 2–5 September 2024; pp. 786–791. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, S.; Eberle, W.; Liu, Y.-F. A Novel EMI Filter Design Method for Switching Power Supplies. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2004, 19, 1668–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoyama, M.; Li, G.; Ninomiya, T. Balanced Switching Converter to Reduce Common-Mode Conducted Noise. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2003, 50, 1095–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kong, P.; Lee, F.C. Common Mode Noise Reduction for Boost Converters Using General Balance Technique. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2007, 22, 1410–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Fan, B.; Bai, Y.; Mitrovic, V.; Dong, D.; Burgos, R.; Boroyevich, D. Common-Mode Noise Reduction and Capacitor Voltage Auto-Balance Using Bridged Midpoints and Coupled Inductor in a 3-L Buck-Boost Converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 12365–12369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, P.; Wang, S.; Lee, F.C.; Wang, Z. Reducing Common-Mode Noise in Two-Switch Forward Converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2011, 26, 1522–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Sun, J. Conducted Common-Mode EMI Reduction by Impedance Balancing. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2012, 27, 1084–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, S.; Puukko, J. Common-Mode EMI Noise Modeling and Reduction with Balance Technique for Three-Level Neutral Point Clamped Topology. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 7563–7573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, H.; Wang, S.; Zhi, Y. Common-Mode EMI Noise Analysis and Reduction for AC–DC–AC Systems with Paralleled Power Modules. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 6989–7000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Son, G.; Li, Q.; Lee, F.C. Balance Techniques and PCB Winding Magnetics for Common-Mode EMI Noise Reduction in Three-Phase AC–DC Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 3130–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, G.; Li, Q. PCB Winding Coupled Inductor Design and Common-Mode EMI Noise Reduction for SiC-Based Soft-Switching Three-Phase AC–DC Converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 14514–14526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Bai, Y.; Mitrovic, V.; Fan, B.; Dong, D.; Burgos, R.; Boroyevich, D.; Moorthy, R.S.K.; Chinthavali, M. A Three-Level Buck–Boost Converter with Planar Coupled Inductor and Common-Mode Noise Suppression. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 10483–10500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, Z.; Guo, P.; Xu, Q.; Hu, J.; Chen, P.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Y.; Luo, A. Common-Mode EMI Noise Reduction with Improved Balance Technique for DC–AC Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 14318–14329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, S.-Y.; Phukan, R.; Burgos, R.; Dong, D.; Mondal, G.; Krupp, H. Common-Mode EMI Noise Modeling and Cancellation with Impedance Balance Technique for Three-Phase Three-Level Back-to-Back Bridge Interconnection-Based Converter. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Phoenix, AZ, USA, 20–24 October 2024; pp. 4887–4894. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Lee, F.C.; Chen, D.Y.; Odendaal, W.G. Effects of Parasitic Parameters on EMI Filter Performance. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2004, 19, 869–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lee, F.C.; Odendaal, W.G. Characterization and Parasitic Extraction of EMI Filters Using Scattering Parameters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2005, 20, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, A.; Koledintseva, M.Y.; Beetner, D.G.; Shao, P.; Berger, P. A Lumped-Element Circuit Model of Ferrite Chokes. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 25–30 July 2010; pp. 754–759. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacic, M.; Hanic, Z.; Stipetic, S.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Zarko, D. Analytical Wideband Model of a Common-Mode Choke. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2012, 27, 3173–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, M.; Stipetić, S.; Hanić, Z.; Žarko, D. Small-Signal Calculation of Common-Mode Choke Characteristics Using Finite-Element Method. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2015, 57, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuellar, C.; Idir, N.; Benabou, A. High-Frequency Behavioral Ring Core Inductor Model. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 3763–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; See, K.Y.; Lai, J.-S.; Tseng, K.J.; Liu, Y.; Tong, C.F.; Nawawi, A.; Yin, S.; Sakanova, A.; Simanjorang, R.; et al. FEM Modelling of Three-Phase Common Mode Choke for Performance Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Asia-Pacific International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility (APEMC), Shenzhen, China, 18–21 May 2016; Volume 01. pp. 96–99. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Feng, C.; Yang, Z.; Yang, Z. An Improved Ferrite Choke RLC Model and Its Parameters Determination Method. In Proceedings of the IECON 2017—43rd Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Beijing, China, 29 October–1 November 2017; pp. 6995–6999. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, G. EMI Filter Design Based on High-Frequency Modeling of Common-Mode Chokes. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 27th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), Cairns, Australia, 13–15 June 2018; pp. 384–388. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačević, I.F.; Friedli, T.; Muesing, A.M.; Kolar, J.W. 3-D Electromagnetic Modeling of EMI Input Filters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2014, 61, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minardi, G.; Greco, G.; Vinci, G.; Rizzo, S.A.; Salerno, N.; Sorbello, G. Electromagnetic Simulation Flow for Integrated Power Electronics Modules. Electronics 2022, 11, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Murata, Y.; Tsubaki, Y.; Fujiwara, T.; Maniwa, H.; Uehara, N. Simulation of Shielding Performance against near Field Coupling to EMI Filter for Power Electronic Converter Using FEM. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility—EMC EUROPE, Wroclaw, Poland, 5–9 September 2016; pp. 716–721. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, W.; Wang, F.; Boroyevich, D.; Stefanovic, V.; Arpilliere, M. Optimizing EMI Filter Design for Motor Drives Considering Filter Component High-Frequency Characteristics and Noise Source Impedance. In Proceedings of the Nineteenth Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition, 2004. APEC ’04., Anaheim, CA, USA, 22–26 February 2004; Volume 2. pp. 669–674. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Fan, T.; Ning, P.; Wen, X. An Automatic EMI Filter Design Methodology for Electric Vehicle Application. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1–5 October 2017; pp. 4497–4503. [Google Scholar]

- Varajão, D.; Esteves Araújo, R.; Miranda, L.M.; Peças Lopes, J.A. EMI Filter Design for a Single-Stage Bidirectional and Isolated AC–DC Matrix Converter. Electronics 2018, 7, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, L.; Yang, S.; Hu, G.; Lv, M. Optimal Design Method of High Voltage DC Power Supply EMI Filter Considering Source Impedance of Motor Controller for Electric Vehicle. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orvai, R.; Hamar, J.; Csörnyei, M. A Practical Survey on Multi-Objective Optimization of EMI Filters. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility—EMC Europe, Paris, France, 1–5 September 2025; pp. 795–800. [Google Scholar]

- Wojtkowski, W.; Kociszewski, R. Pulse-Width Modulation Approaches for Efficient Harmonic Suppression. Electronics 2025, 14, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, S.; Akagi, H. Modeling and Damping of High-Frequency Leakage Currents in PWM Inverter-Fed AC Motor Drive Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1996, 32, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Luo, F.; Dong, D.; Mattavelli, P.; Boroyevich, D. CM Noise Containment in a DC-Fed Motor Drive System Using DM Filter. In Proceedings of the 2012 Twenty-Seventh Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Orlando, FL, USA, 5–9 February 2012; pp. 1808–1813. [Google Scholar]

- Son, Y.-C.; Sul, S.-K. Generalization of Active Filters for EMI Reduction and Harmonics Compensation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2006, 42, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haensel, S.; Teller, J.; Frei, S. Modeling and Stability Analysis of Voltage Sense Current Cancellation Active EMI Filter. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility—EMC Europe, Kraków, Poland, 4–8 September 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chow, A.C.; Perreault, D.J. Design and Evaluation of a Hybrid Passive/Active Ripple Filter with Voltage Injection. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2003, 39, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, R.; Wang, S. Investigation and Modeling of Combined Feedforward and Feedback Control Schemes to Improve the Performance of Differential Mode Active EMI Filters in AC–DC Power Converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 6538–6548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Shao, S.; Zhou, J.; Chen, H. Design of Active EMI Filter Combining Feedforward and Feedback Control. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd China Power Supply Society Electromagnetic Compatibility Conference (CPEMC), Hangzhou, China, 16–18 August 2024; pp. 328–333. [Google Scholar]

- Ogasawara, S.; Ayano, H.; Akagi, H. An Active Circuit for Cancellation of Common-Mode Voltage Generated by a PWM Inverter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 1998, 13, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.-C.; Sul, S.-K. A New Active Common-Mode EMI Filter for PWM Inverter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2003, 18, 1309–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Piazza, M.C.; Tine, G.; Vitale, G. An Improved Active Common-Mode Voltage Compensation Device for Induction Motor Drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2008, 55, 1823–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.; Kim, J.; Son, C.; Jeon, S.; Cho, B.; Han, J. A Simple Low-Cost Common Mode Active EMI Filter Using a Push-Pull Amplifier. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Milwaukee, WI, USA, 18–22 September 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.; Jeong, S.; Kim, J. Quantified Design Guidelines of a Compact Transformerless Active EMI Filter for Performance, Stability, and High Voltage Immunity. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 6723–6737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z. An Active EMI Filtering Technique for Improving Passive Filter Low-Frequency Performance. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2006, 48, 172–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainali, K.; Oruganti, R. Design of a Current-Sense Voltage-Feedback Common Mode EMI Filter for an off-Line Power Converter. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Power Electronics Specialists Conference, Rhodes, Greece, 15–19 June 2008; pp. 1632–1638. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Zhang, W.; Yang, X.; Sheng, Z.; Wang, Z. An Experimental Study of Common- and Differential-Mode Active EMI Filter Compensation Characteristics. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2009, 51, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarateeraseth, V. Enhancement of Operational Amplifier Gain-Bandwidth Product Used in Common-Mode Active EMI Filter Compensation Circuit. In Proceedings of the 2013 10th International Conference on Electrical Engineering/Electronics, Computer, Telecommunications and Information Technology, Krabi, Thailand, 15–17 May 2013; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Labouré, E.; Costa, F. Integrated Active Filter for Differential-Mode Noise Suppression. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2014, 29, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, X.; Zhang, R.; Yan, R.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. A New Integrated Active EMI Filter Topology with Both CM Noise and DM Noise Attenuation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 5466–5478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Bazzi, A.M. A Virtual Impedance Enhancement Based Transformer-Less Active EMI Filter for Conducted EMI Suppression in Power Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 11962–11973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poon, N.K.; Liu, J.C.P.; Tse, C.K.; Pong, M.H. Techniques for Input Ripple Current Cancellation: Classification and Implementation [in SMPS]. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2000, 15, 1144–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Maillet, Y.Y.; Wang, F.; Boroyevich, D.; Burgos, R. Investigation of Hybrid EMI Filters for Common-Mode EMI Suppression in a Motor Drive System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2010, 25, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, D.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Z. Insertion Loss Analysis and Optimization of a Current Based Common-Mode Active EMI Filter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 14353–14362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, Z. A Novel Hybrid Common-Mode EMI Filter with Active Impedance Multiplication. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 1826–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q. Modeling and Stability Analysis of Active/Hybrid Common-Mode EMI Filters for DC/DC Power Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 6254–6263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhou, P.; Pei, X.; Yu, Y.; Kang, Y. A Novel Design Method for Hybrid Common-Mode EMI Filters Based on Attenuation Adjustability. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 3138–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, S.; He, D.; Zhao, Z.; Su, W. A Hybrid EMI Filter Incorporating Active Y-Capacitor for Common-Mode Noise Mitigation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 5252–5264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, X.; Yu, Z.; Meng, X.; Ren, P.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X. A Novel Neutral Point-Based Active EMI Filter for Common Mode Noise Attenuation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 10081–10085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, W.; Yang, X. Investigation of Cascade Connection Method to Improve the Insertion Loss of DM Active EMI Filters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2022, 10, 1084–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Meng, X.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Dang, H.; Su, D.; Sun, S.; Chen, W.; Yang, X. A Novel Virtual Capacitance Enhancement-Based Active EMI Filter for CM Noise Attenuation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 16870–16874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhou, P.; Pei, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Kang, Y. Phasor Analysis-Based Design Method for Active Common-Mode EMI Filter in DC/AC Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 18027–18039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, D.; Mei, Q.; Jain, P.K. Implementation of an EMI Active Filter in Grid-Tied PV Micro-Inverter Controller and Stability Verification. In Proceedings of the IECON 2012—38th Annual Conference on IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Quebec, QC, Canada, 25–28 October 2012; pp. 477–482. [Google Scholar]

- Hamza, D.; Pahlevaninezhad, M.; Jain, P.K. Implementation of a Novel Digital Active EMI Technique in a DSP-Based DC–DC Digital Controller Used in Electric Vehicle (EV). IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 3126–3137. [Google Scholar]

- Hamza, D.; Qiu, M. Digital Active EMI Control Technique for Switch Mode Power Converters. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2013, 55, 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Darisi, M.; Caldognetto, T.; Biadene, D.; Stellini, M. Digital Active EMI Filter for Smart Electronic Power Converters. Electronics 2024, 13, 3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Chen, W.; Yang, X.; Lu, J. Delay and Decoupling Analysis of a Digital Active EMI Filter Used in Arc Welding Inverter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2018, 33, 6710–6722. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Pei, X.; Chen, Q.; Yang, C.; Zhou, P.; Geng, G. Design and Delay Compensation of Digital Active EMI Filter Based on Adaptive Notch LMS Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 CPSS & IEEE International Symposium on Energy Storage and Conversion (ISESC), Xi’an, China, 8–11 November 2024; pp. 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; Wang, S.; van Wyk, J.D.; Odendaal, W.G. Integration of EMI Filter for Distributed Power System (DPS) Front-End Converter. In Proceedings of the IEEE 34th Annual Conference on Power Electronics Specialist, 2003, PESC ’03., Acapulco, Mexico, 15–19 June 2003; Volume 1. pp. 296–300. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Wen, Z.; Xu, D.; Okuma, Y.; Mino, K. An Integrating Structure of EMI Filter Based on Interleaved Flexible Multi-Layer (FML) Foils. In Proceedings of the 2009 Twenty-Fourth Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition, Washington, DC, USA, 15–19 February 2009; pp. 491–497. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R.; van Wyk, J.D.; Wang, S.; Odendaal, W.G. Planar Electromagnetic Integration Technologies for Integrated EMI Filters. In Proceedings of the 38th IAS Annual Meeting on Conference Record of the Industry Applications Conference, 2003, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 12–16 October 2003; Volume 3. pp. 1582–1588. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; van Wyk, J.D. Frequency-Domain Modeling of Integrated Electromagnetic Power Passives by a Generalized Two-Conductor Transmission Structure. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Regul. Pap. 2004, 51, 2325–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xu, C. Design Theory and Implementation of a Planar EMI Filter Based on Annular Integrated Inductor–Capacitor Unit. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2013, 28, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Wang, S.; Li, B.-L. Design and Implementation of Planar EMI Filter under the Condition of Impedance Mismatching. In Proceedings of the 2015 Asia-Pacific Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility (APEMC), Taipei, Taiwan, 26–29 May 2015; pp. 136–139. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Dehong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Okuma, Y.; Mino, K. Integrated EMI Filter Design with Flexible PCB Structure. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Power Electronics Specialists Conference, Rhodes, Greece, 15–19 June 2008; pp. 1613–1617. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Xu, D.; Wen, Z.; Okuma, Y.; Mino, K. Design, Modeling, and Improvement of Integrated EMI Filter with Flexible Multilayer Foils. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2011, 26, 1344–1354. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, C.; Chen, M.; Chen, P.; Hu, C.; Zhang, W.; Xu, D. A PFC Converter with Novel Integration of Both the EMI Filter and Boost Inductor. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2014, 29, 4485–4489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Xu, D.; Chen, P.; Hu, C.; Zhang, W.; Wen, Z.; Wu, X. Integration of Both EMI Filter and Boost Inductor for 1-kW PFC Converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2014, 29, 5823–5834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Chen, Y.; Chen, P.; Zhong, W.; Xu, D. An Integrating Structure of Output Filter for Grid Connected Inverter Based on FMLF Technique. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Power Electronics Conference (IPEC-Niigata 2018-ECCE Asia), Niigata, Japan, 20–24 May 2018; pp. 1118–1124. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, W.; Wang, P.; Xu, D. A Fully Integrated Common-Mode Choke Design Embedded with Differential-Mode Capacitances. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 5501–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Xu, D. Full Electromagnetic Integration of Impedance-Balanced EMI Filters for Single-Phase Power Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 7166–7182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Li, S.; Tang, J. A Review of Flexible Multilayer Foil Integration Technology for Passive Components. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 13025–13038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control Method | IL(s) | Approximate IL(s) | Condition for Maximum IL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feedback CSVC | |||

| Feedback VSCC | |||

| Feedback VSVC | |||

| Feedback CSCC | |||

| Feedforward VSVC | |||

| Feedforward CSCC |

| EMI Filter Types | Cost | Volume | Filter Reliability | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEFs | Low | Large | High | Low |

| AEFs | Mid | Mid | Low | Mid |

| Electromagnetic IEFs | High | Compact | High | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, C.; Wang, P.; Wang, W.; Xu, D. A Review of Filters for Conducted Electromagnetic Interference Suppression in Converters. Energies 2025, 18, 6470. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246470

Cao C, Wang P, Wang W, Xu D. A Review of Filters for Conducted Electromagnetic Interference Suppression in Converters. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6470. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246470

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Chenyu, Panbao Wang, Wei Wang, and Dianguo Xu. 2025. "A Review of Filters for Conducted Electromagnetic Interference Suppression in Converters" Energies 18, no. 24: 6470. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246470

APA StyleCao, C., Wang, P., Wang, W., & Xu, D. (2025). A Review of Filters for Conducted Electromagnetic Interference Suppression in Converters. Energies, 18(24), 6470. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246470