A Coordinated Inertia Support Strategy for Wind–PV–Thermal Storage Systems Considering System Inertia Demand

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Inertia Assessment of Integrated Wind-PV-Thermal-Storage Systems

2.1. Inertia Characteristics of Wind-PV-Thermal-Storage Units

2.1.1. Inertia Characteristics of Thermal Power Units

2.1.2. Inertia Characteristics of Wind Turbines

2.1.3. Inertia Characteristics of Photovoltaic Systems

2.1.4. Inertia Characteristics of Battery Energy Storage Systems

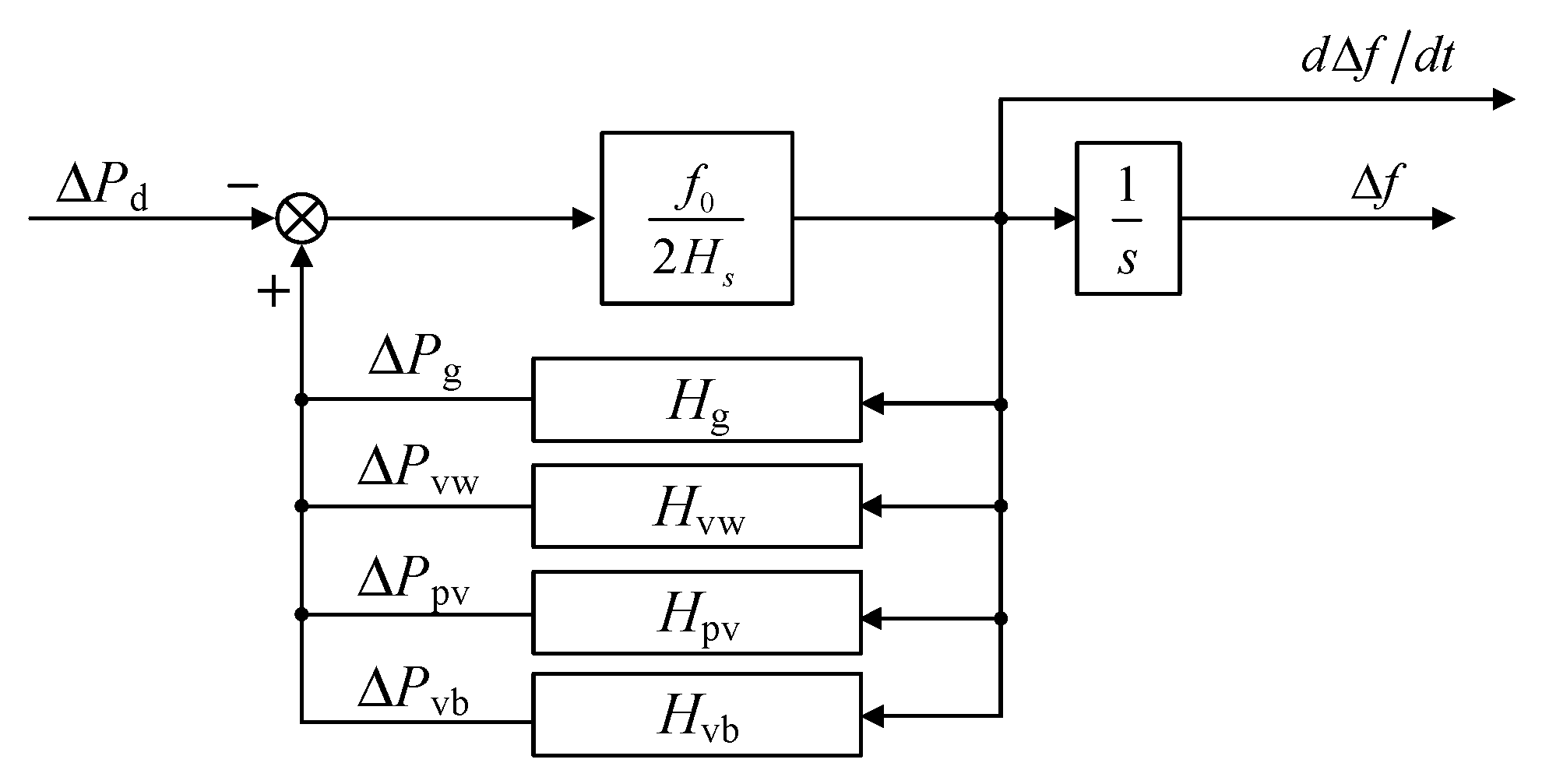

2.2. Frequency Response Model of Wind-PV-Thermal Power and Battery Storage

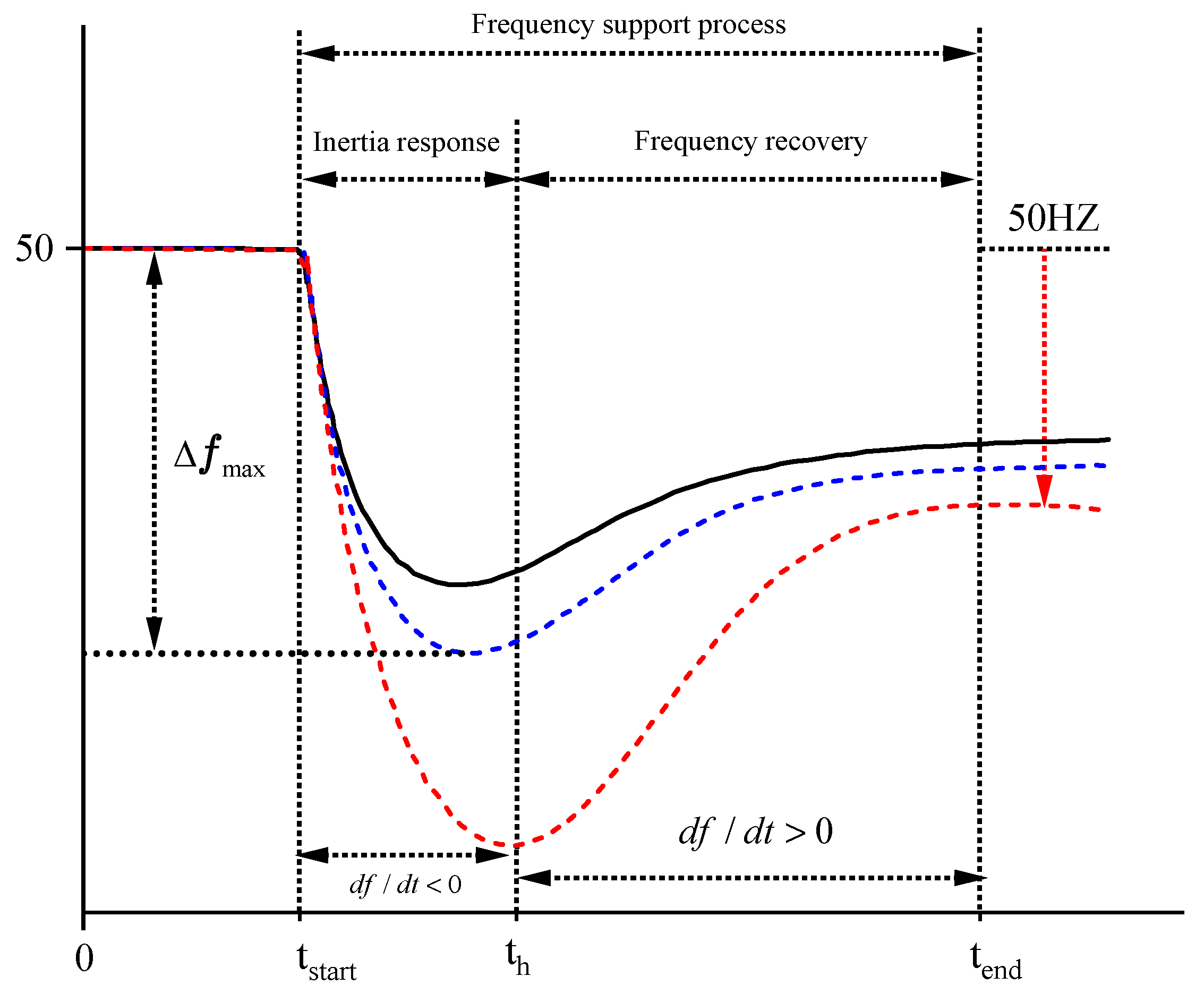

3. System Frequency Dynamic Characteristics

3.1. System Inertia Requirement Under Frequency Security Constraints

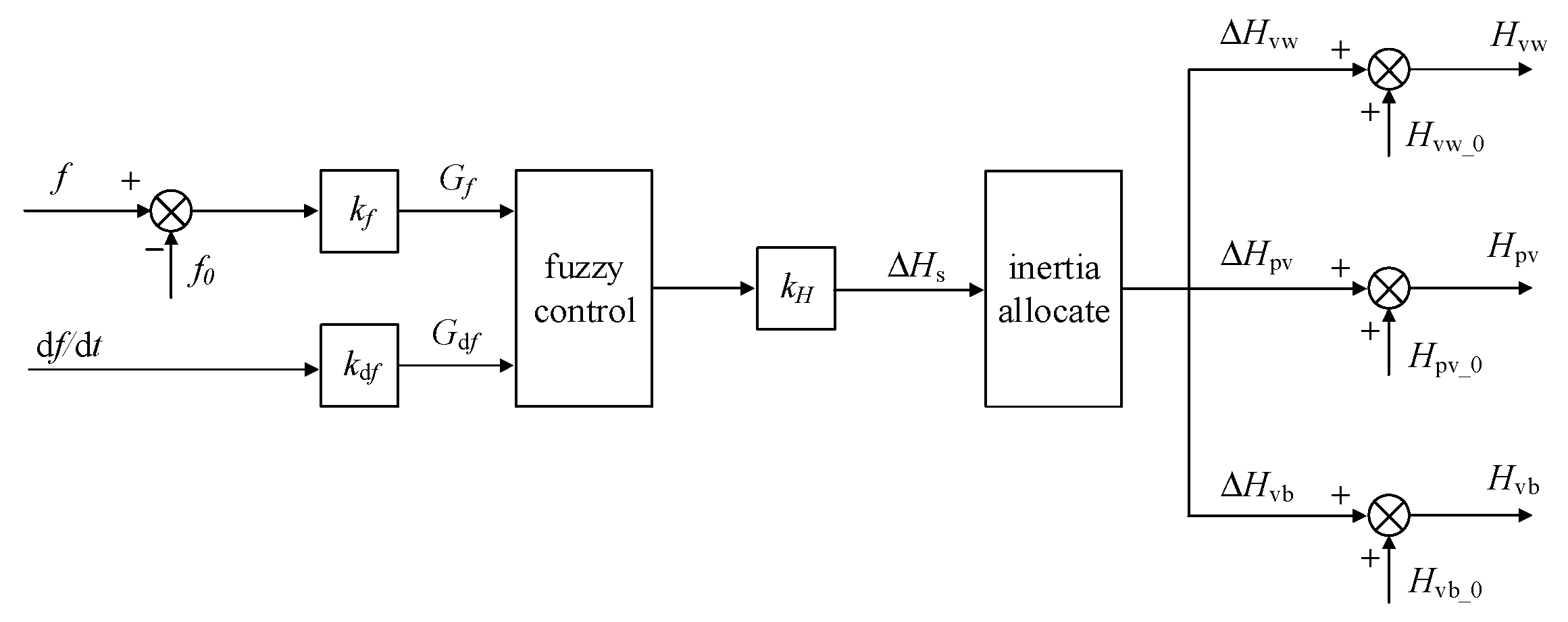

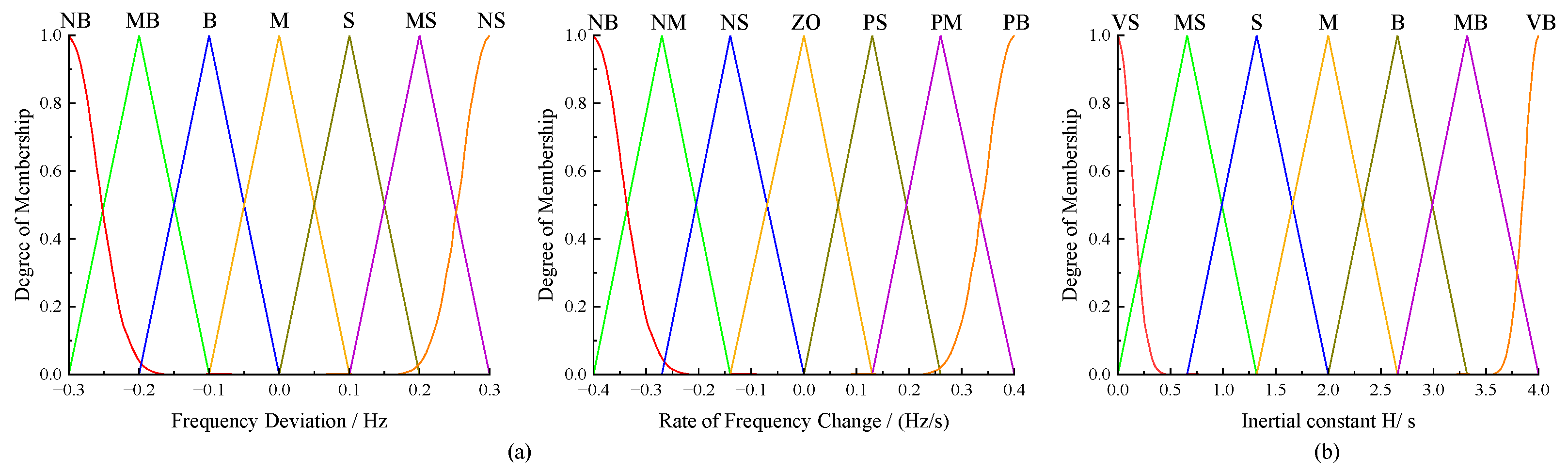

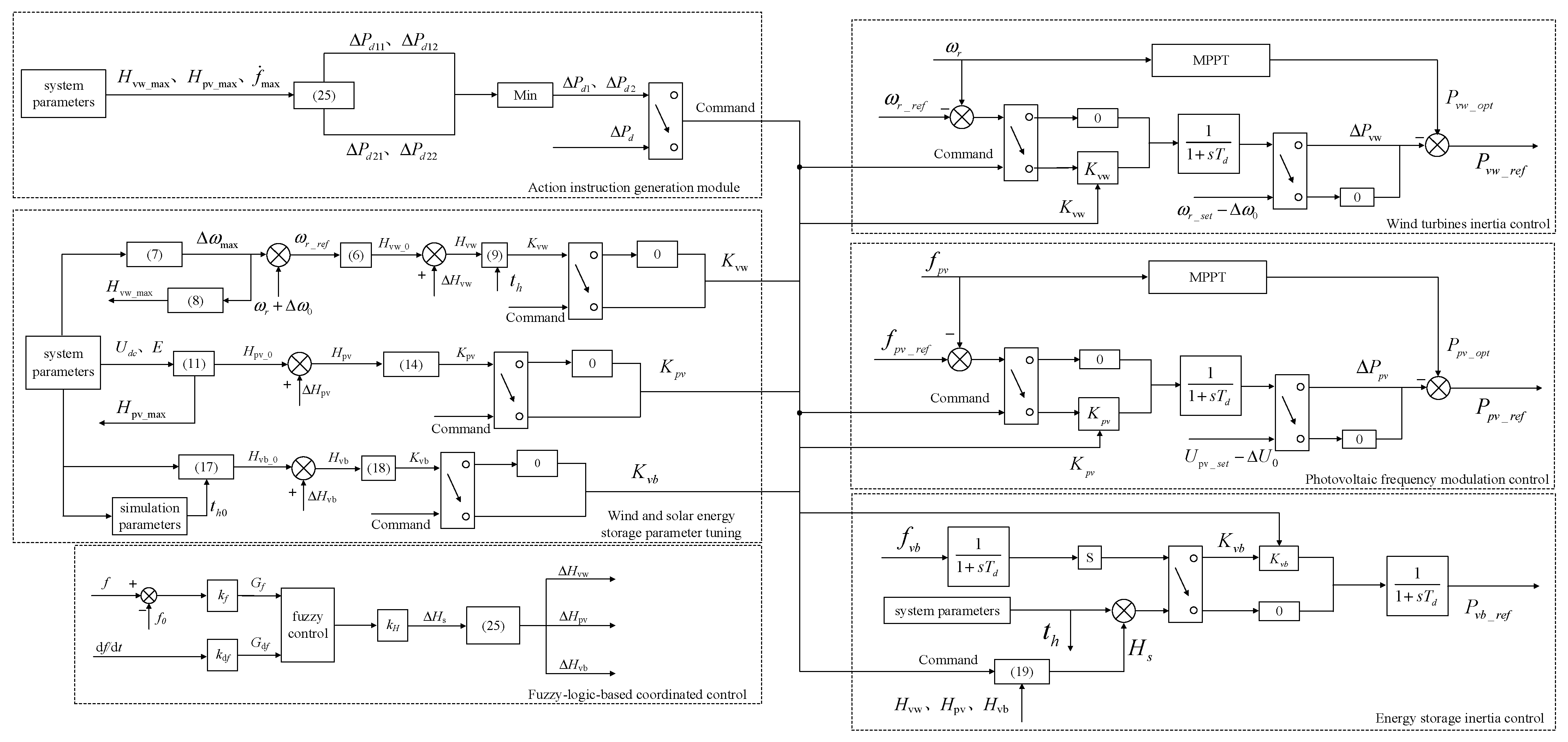

3.2. Design of the Fuzzy-Logic-Based Coordinated Control

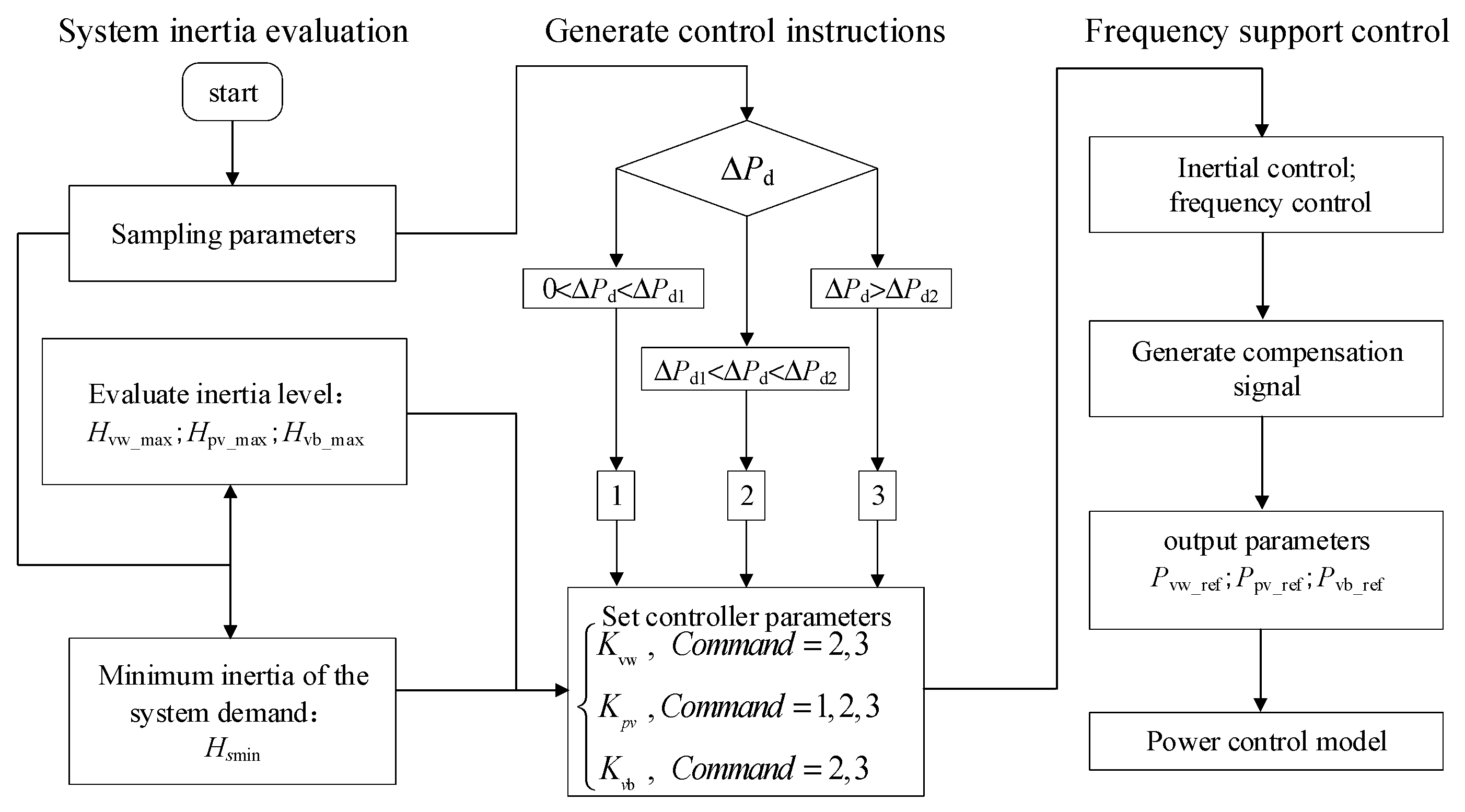

4. Coordinated Inertia Support Strategy for Wind-Solar-Storage Systems Under Security Constraints

4.1. Inertia Allocation Method

4.1.1. Disturbance Reference Interval Partitioning

- Small disturbance: Inertia control of renewable energy units is not required. When the synchronous generator inertia equals the minimum system inertia requirement, the disturbance magnitude is ΔPd1. That is, when ΔPd ≤ ΔPd1, Hsmin ≤ Hg.

- Moderate disturbance: Wind turbines and photovoltaic systems are required to provide inertia support. When the sum of the maximum inertia reserves from wind, photovoltaic, and thermal power equals the minimum system inertia requirement, the disturbance magnitude is ΔPd2. Combining with Equation (6), when ΔPd1 < ΔPd ≤ ΔPd2, Hg < Hsmin ≤ F(Hvw_max, Hpv_max, Hg).

- Large disturbance: Wind, photovoltaic, thermal, and storage systems collectively provide inertia support. Energy storage inertia control is activated, and the system’s reserved inertia meets the minimum system inertia requirement. That is, when ΔPd2 < ΔPd, Hsmin ≤ Hs.

4.1.2. Inertia Allocation Scheme

- In Scenario 1, the system generates frequency regulation command 1, where wind, solar, and storage units only activate frequency regulation control without providing inertia support.

- In Scenario 2, the system generates frequency regulation command 2, where wind turbine inertia control is activated, while energy storage inertia control remains inactive.

- In Scenario 3, the system generates frequency regulation command 3, where both wind and storage inertia controls are activated.

4.2. Coordinated Control Strategy

5. Simulation Analysis

5.1. Experimental Design

- Traditional Control: Wind and storage systems adopt conventional inertia control with fixed controller parameters, while photovoltaic systems utilize traditional power tracking control.

- Proposed Coordinated Strategy: Fuzzy-logic-based coordinated control is applied to adjust the parameters of wind-storage inertia controllers and photovoltaic droop controllers. Based on the predefined disturbance intervals, a coordinated allocation strategy is implemented to achieve stepwise activation of wind, photovoltaic, and storage controllers.

- Scenario 1 (Synchronous Generators Solely Providing Support): When the step change in disturbance load is 0.07 p.u., the minimum system inertia requirement Hsmin is determined to be 3.5 s based on the frequency constraint. The inertia provided by the synchronous generators is 7.3 s. Since 0 < ΔPd < ΔPd1, the system generates frequency regulation command 1. Renewable sources (wind and PV) and energy storage only participate in power regulation and do not provide inertia support.

- Scenario 2 (Renewables Participating in Inertia Support): When the step change in disturbance load is 0.10 p.u., the minimum system inertia requirement Hsmin is 6.3 s. Since ΔPd1 < ΔPd < ΔPd2, the system generates frequency regulation command 2. The parameter setting module outputs the parameters for the wind turbine inertia controller and the PV power regulation coefficient, while the parameters for the energy storage inertia controller are set to zero. Wind turbines and synchronous generators jointly provide inertia support, and wind, PV, thermal, and energy storage work coordinatively to accomplish frequency regulation.

- Scenario 3 (Coordinated Inertia Support from Wind, PV, Thermal, and Storage): When the step change in disturbance load is 0.15 p.u., the minimum system inertia requirement Hsmin is 7.2 s. Since ΔPd > ΔPd2, the system generates frequency regulation command 3. The parameter setting module outputs the parameters for the wind and energy storage inertia controllers and the PV power regulation coefficient. Wind turbines, energy storage, and synchronous generators jointly provide inertia support, achieving coordinated frequency support from wind, PV, thermal, and energy storage.

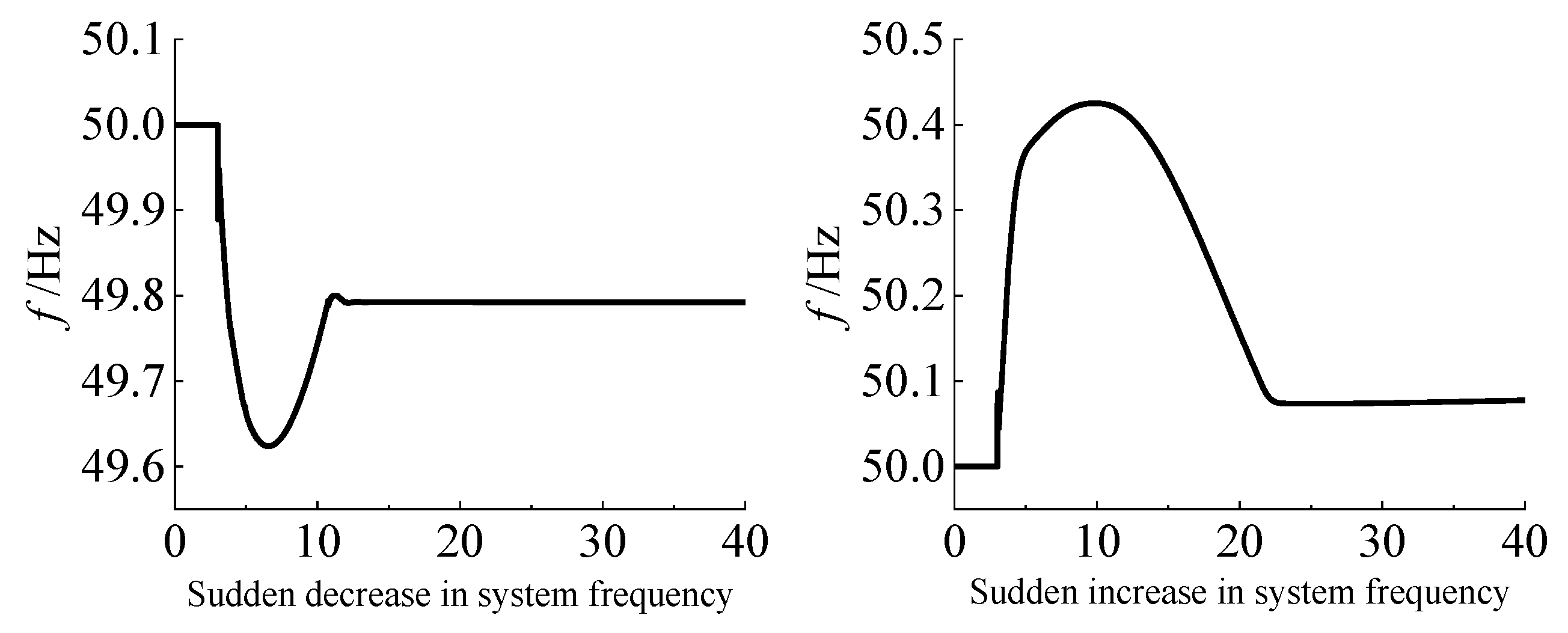

- According to Figure 8, in Scenario 1 under the proposed strategy, a sudden load increase leads to a frequency drop, with a maximum RoCoF of −0.558 Hz/s and a maximum frequency deviation of −0.425 Hz. Conversely, a sudden load decrease results in a frequency rise, with a maximum RoCoF of 0.655 Hz/s and a maximum frequency deviation of 0.377 Hz. These values satisfy the frequency security constraints, with wind and storage providing no inertia support. The controller parameters for the three scenarios are listed in Table 6.

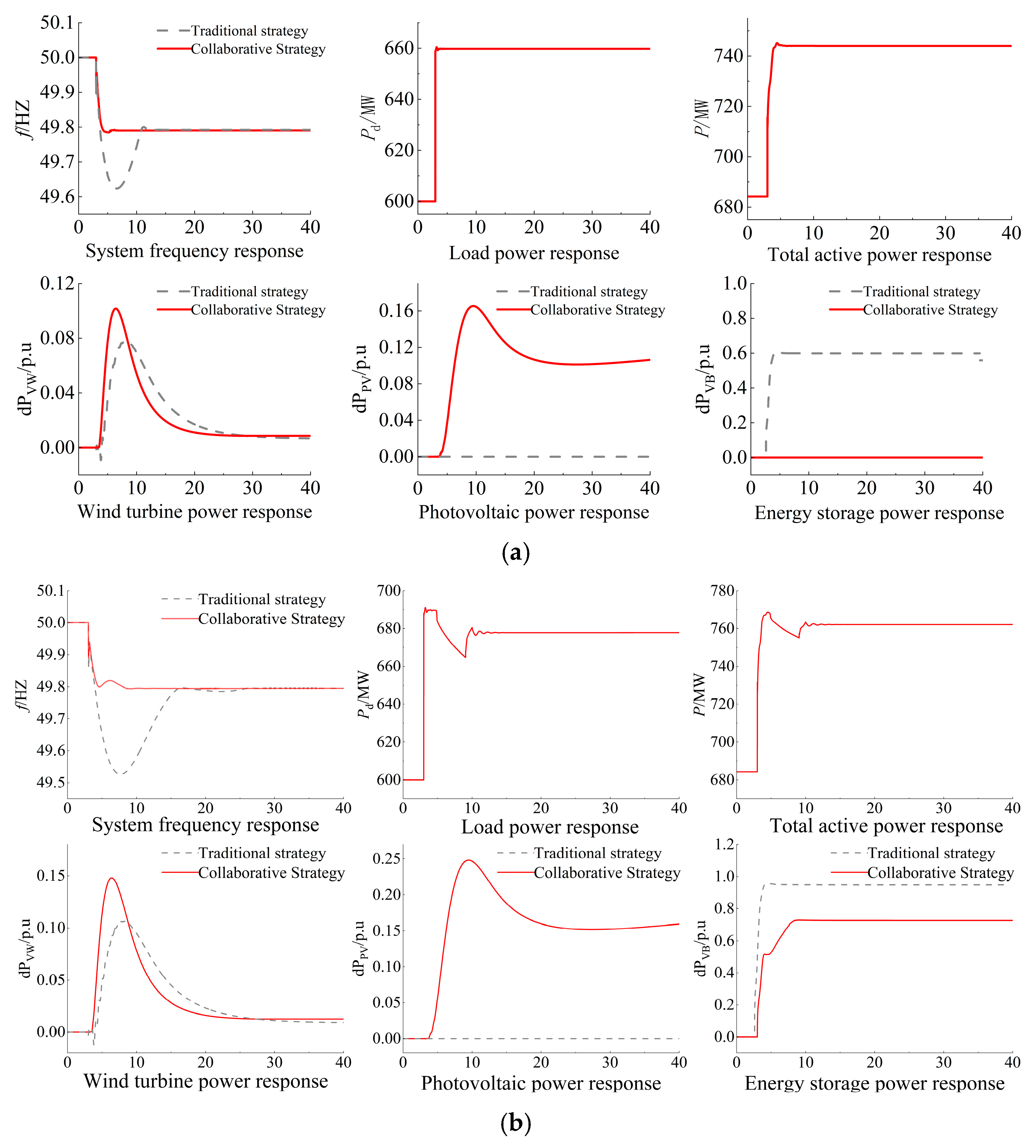

5.2. Simulation Experiment for Sudden Load Increase

- In Scenario 2, under the proposed strategy, the inertial response time is 2.084 s, the maximum RoCoF is −0.307 Hz/s, and the frequency nadir is 0.215 Hz, all of which satisfy the frequency constraints. During the initial stage of the disturbance, the wind turbine’s inertial control is activated, increasing its output power by 0.102 p.u. before recovering to 1.01 p.u. The photovoltaic system increases its output by 0.1 p.u. when reserve capacity is available, while the energy storage system remains inactive.

- In Scenario 3, under the proposed strategy, the inertial response time is 1.86 s, the maximum RoCoF is −0.34 Hz/s, and the frequency nadir is 0.2 Hz, also meeting the frequency constraints. During the initial stage of the disturbance, the wind turbine’s inertial control is activated, increasing its output power by 0.147 p.u. before recovering to 1.01 p.u. The photovoltaic system increases its output by 0.151 p.u. when reserve capacity is available, while the energy storage system’s inertial control is activated, briefly delivering 0.51 p.u. of power and further increasing to 0.72 p.u. according to frequency regulation requirements.

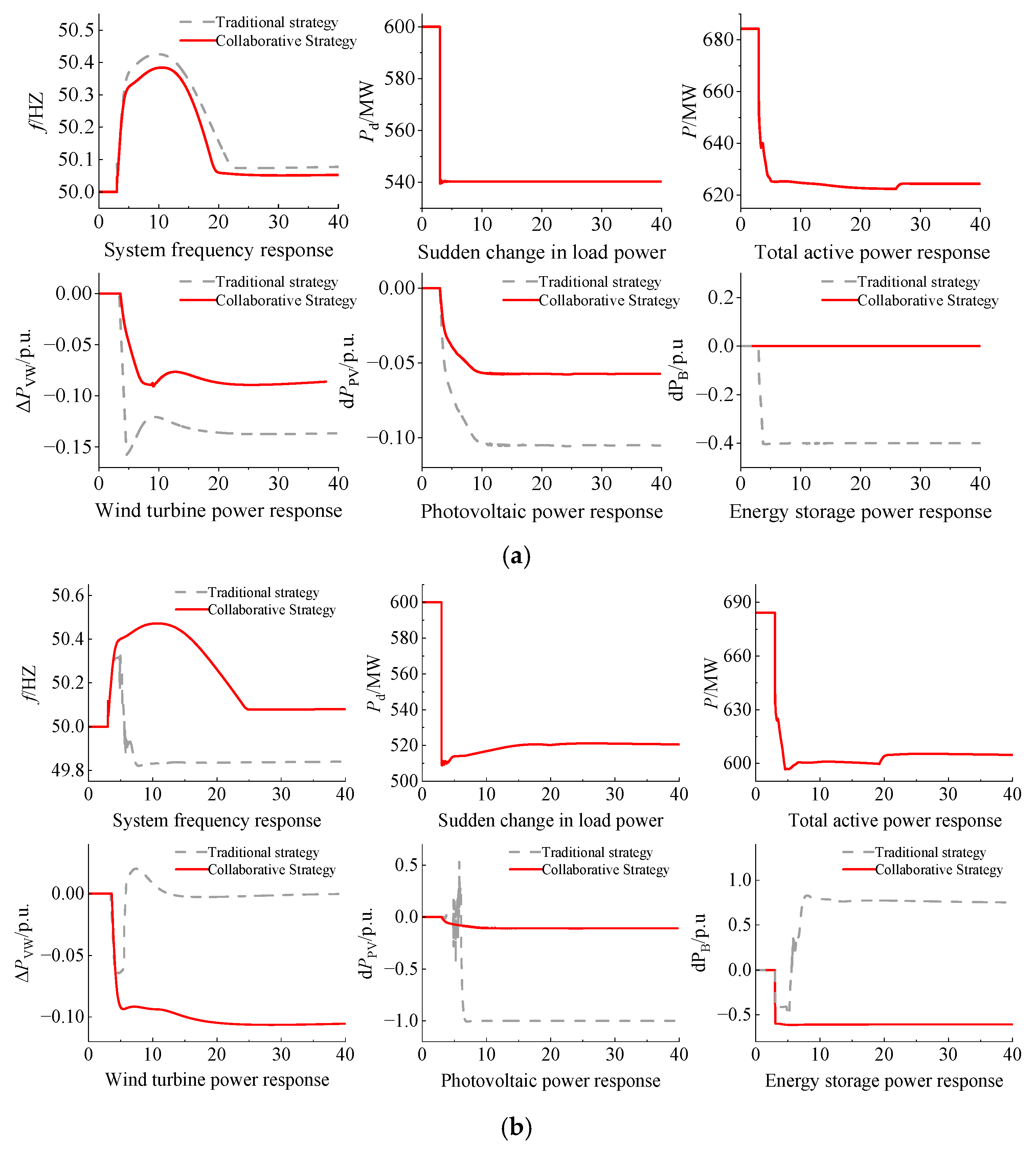

5.3. Simulation Experiment for Sudden Load Decrease

- In Scenario 2, under the proposed strategy, the maximum RoCoF is 0.312 Hz/s, the frequency peak is 50.383 Hz, and the inertial response time is 6.76 s, all of which satisfy the frequency constraints. During the initial stage of the disturbance, the wind turbine’s inertial control is activated, reducing its output power by 0.153 p.u. before recovering to 0.863 p.u. The photovoltaic system reduces its output by 0.057 p.u. under droop control, while the energy storage system remains inactive.

- In Scenario 3, under the proposed strategy, the maximum RoCoF is 0.411 Hz/s, the frequency peak is 50.47 Hz, and the inertial response time is 7.77 s, also meeting the frequency constraints. During the initial stage of the disturbance, the wind turbine’s inertial control is activated, reducing its output power by 0.093 p.u. and further decreasing to 0.894 p.u. The photovoltaic system reduces its output by 0.107 p.u. under droop control, while the energy storage system’s inertial control is activated, absorbing 0.6 p.u. of power.

6. Conclusions

- A virtual inertia evaluation method incorporating the inertia time constant was developed to quantify system inertia demand and the inertia support capability of individual units. This method provides an intuitive assessment of system inertia reserve and enables effective analysis of the impact of parameters such as wind turbine speed and energy storage capacity on overall system inertia. Simulation results verify that the method accurately assesses system frequency security requirements, establishing a critical foundation for subsequent coordinated control.

- A fuzzy-logic-based coordinated control with the inertia time constant as its output was designed to optimize the inertia evaluation results and achieve precise allocation of virtual inertia across units. To address the challenge of multi-source inertia fitting and distribution, this approach innovatively employs the inertia time constant as the fuzzy-logic-based coordinated control output, replacing traditional fixed-parameter allocation methods. Utilizing adaptive rules to dynamically optimize the control parameters for wind, PV, and storage units, this method significantly enhances allocation accuracy and system dynamic response performance, ensuring the evaluation results align closely with actual system needs.

- An integrated “evaluation-allocation-control” framework was established, where inertia evaluation results directly inform the parameter tuning of wind, PV, and storage controllers. The core innovation lies in the seamless integration of inertia assessment with controller setpoints. The evaluated system inertia demand is no longer an isolated metric but serves as a direct input for adaptively adjusting the control commands of renewable units and storage, thereby translating system-level inertia requirements into precise, coordinated unit-level actions.

- A scenario-based unit commitment strategy was proposed, which selectively activates resources according to disturbance type and severity, effectively enhancing the system’s inertia support capability under various operating conditions. By categorizing power disturbances into different intervals and types (e.g., sudden increase/decrease), this strategy enables the intelligent switching and role assignment of wind, PV, and storage units. Simulation results demonstrate its effectiveness: under a sudden load increase scenario (Scenario 2), the strategy coordinated a wind power increase of 0.102 p.u. and a PV output increase of 0.1 p.u., maintaining the frequency nadir at 49.785 Hz without requiring energy storage intervention. Under a sudden load decrease scenario (Scenario 3), the strategy directed wind power to rapidly reduce output by 0.093 p.u. and activated the energy storage system to absorb 0.6 p.u. of excess power, successfully suppressing the frequency peak to 50.47 Hz. This fully proves the strategy’s capability to flexibly and efficiently utilize system resources to handle bidirectional power disturbances while avoiding frequent actions by any single unit.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, H.; Liu, D.; Yao, D. Analysis and reflection on the development of power system towards the goal of carbon emission peak and carbon neutrality. Proc. CSEE 2021, 41, 6245–6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Hove, A.; Hu, J.; Dupuy, M.; Bregnbæk, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, N. Coping with power crises under decarbonization: The case of China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 193, 114294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Kang, C. Challenges and prospects for constructing the new-type power system towards a carbon neutrality future. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 2806–2819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y. Reflections on frequency stability control technology based on the blackout event of 9 August 2019 in UK. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2019, 43, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lin, W.; He, G.; Shi, W.; Feng, S. Enlightenment of 2021 Texas blackout to the renewable energy development in China. Proc. CSEE 2021, 41, 4033–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, L.; Zhou, W.; Li, C. Comprehensive Evaluation of Active Frequency Support Characteristics of Photovoltaic Stations Connected to Regional Power System. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 14th International Conference on CYBER Technology in Automation, Control, and Intelligent Systems (CYBER), Copenhagen, Denmark, 16–19 July 2024; pp. 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Bai, K.; Lu, Z.X.; Li, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, S. Analysis of Challenges and Future Form Evolution of Extra-Large New Energy Bases. J. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2023, 6, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heptonstall, P.J.; Gross, R.J. A systematic review of the costs and impacts of integrating variable renewables into power grids. Nat. Energy 2021, 6, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. Frequency modulation technology for power systems incorporating wind power, energy storage, and flexible frequency modulation. Sustain. Energy Res. 2025, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, K.; Lai, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, X.; Lu, P.; Jin, Y. Review of frequency characteristics analysis and battery energy storage frequency regulation control strategies in power system under low inertia level. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 47, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhu, D.; Hu, J.; Liu, R.; Zou, X.; Kang, Y. Inertia Evaluation and Optimal Design for PMSG-Based Wind Turbines With df/dt Control. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 2905–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.H.; Yuan, T.; Tong, X.; Li, X.L. Coordination control strategy of wind-storage system based on fuzzy control. Mod. Electr. Power 2021, 42, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.U.; Yan, X.; Abdelbaky, M.A.; Jan, M.U.; Iqbal, S. An advanced virtual synchronous generator control technique for frequency regulation of grid-connected PV system. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 125, 106440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.H.; Yan, L.J.; Huang, W.T.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, F.; Ye, J.Y. Control strategy of photovoltaic-storage VSG considering maximum power output and energy storage coordination. J. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2024, 52, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, Y. Wind-storage cooperative fast frequency response technology based on system inertia demand. Proc. CSEE 2023, 43, 5415–5429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Qian, K.; Lin, H.; Cao, Y. Photovoltaic-storage coordinated support control technology based on primary frequency regulation requirements. Energy Rep. 2024, 12, 6126–6136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, T.; Zeng, Z.; Qu, M.; Catalão, J.P.S.; Shahidehpour, M. Two-Stage Chance-Constrained Stochastic Thermal Unit Commitment for Optimal Provision of Virtual Inertia in Wind-Storage Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 3520–3530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Cai, J.; Xiao, R.; Wang, S.; Xie, Y.; Tang, X. A wind-storage coordinated control strategy for improving system frequency response characteristics. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2021, 41, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Yang, Y.; Liu, T.; Blaabjerg, F. Coordination of virtual inertia control and frequency damping in PV systems for optimal frequency support. CPSS Trans. Power Electron. Appl. 2020, 5, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Bian, Z. Virtual moment inertia control based on hybrid static energy storage. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2019, 39, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yao, L.; Xu, J.; Cheng, F.; Mao, B.; Wen, Z.; Chen, R. S-MCMC Based Equivalent Inertia Probability Evaluation for Power Systems with High Proportional Renewable Energy. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 48, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, O.H.; Carlos, B.D. Trade-off between frequency stability and renewable generation–Studying virtual inertia from solar PV and operating stability constraints. Renew. Energy 2024, 232, 121075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrzad, A.; Darmiani, M.; Rouhani, S.H.; Su, C.-L.; Sepestanaki, M.A.; Mofidipour, E.; Monti, A.; Anvari-Moghaddam, A. Inertia in renewable power systems: A review of estimation methods and practical implementation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heylen, E.; Teng, F.; Strbac, G. Challenges and opportunities of inertia estimation and forecasting in low-inertia power systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 147, 111176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Sun, H.; Li, W.; Yan, J.; Yu, Z.; Yang, C. Minimum inertia estimation of power system considering dynamic frequency constraints. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, D.; Cai, G. Review of research on power system inertia related issues in the context of high penetration of renewable power generation. Power Syst. Technol. 2020, 44, 2998–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, R.K.; Wu, W.; Zou, Z.B.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y.; Yi, P. Discrimination of inertia and inertia response characteristics in power system frequency dynamics. Proc. CSEE 2022, 43, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Gao, J. Frequency Characteristic Analysis of Low-inertia Power System Considering Energy Storage. Proc. CSEE 2023, 43, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Wen, Y.; Ye, X.; Liu, F.; Guo, W.; Zhou, S. Emergency frequency control strategy for double-high sending-end grids with coordination of multiple resources. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 48, 3801–3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Lv, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, Y. Virtual synchronous generator of PV generation without energy storage for frequency support in autonomous microgrid. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 134, 107343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, G.; Zhang, H.; Wang, C. Analysis of renewable energy participation in primary frequency regulation and parameter setting scheme of power grid. Power Syst. Technol. 2020, 44, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, J.; Hu, P. Feasible Region Analysis Method for Virtual Inertia and Power-frequency Droop Gain ofActive-supporting Sources. Proc. CSU-EPSA 2024, 36, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, A.; Khayat, Y.; Naderi, M.; Dragicevic, T.; Mirzaei, R.; Blaabjerg, F.; Bevrani, H. Inertia Response Improvement in AC Microgrids: A Fuzzy-Based Virtual Synchronous Generator Control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 4321–4331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Pan, T.; Yang, W.; Zhang, C.; Huang, W.; Xu, D. Fuzzy-enhanced cooperative control of multiple virtual synchronous generators for grid-connected energy storage systems. J. Energy Storage 2026, 142, 119607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, C. Fuzzy adaptive virtual inertia control strategy of wind turbines based on system frequency response interval division. Power Syst. Technol. 2021, 45, 1658–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scenario | Oscillation Interval | df/dt | Δf | Hs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Load Sudden Increase | [tstart, th] | <0 | <0 | Increase |

| [th, tend] | >0 | <0 | Decrease | |

| Load Sudden Decrease | [tstart, th] | >0 | >0 | Increase |

| [th, tend] | <0 | >0 | Decrease |

| ΔHs | Gf | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NB | NM | NS | ZE | PS | PM | PB | ||

| Gdf | NB | PB | PM | PM | PB | NM | NM | NB |

| NM | PB | PM | PS | PM | NS | NM | NB | |

| NS | NS | PM | PS | ZE | NS | NM | NM | |

| ZE | NB | NM | ZE | ZE | ZE | NM | NB | |

| PS | NM | NM | NS | ZE | PS | PM | PM | |

| PM | NB | NM | NM | PB | PM | PM | PB | |

| PB | NB | NM | NM | PB | PM | PM | PB | |

| Disturbance Scenarios | ΔPd/p.u. | Hg/s | Hvw_set/s | Hpv_set/s | Hvb_set/s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1 | [0, ΔPd1] | Hg | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scenario 2 | [ΔPd1, ΔPd2] | Hg | Hvw | Hpv | 0 |

| Scenario 3 | [ΔPd2, ΔPde) | Hg | Hvw_max | Hpv_max | Hvb |

| Component Type | Total Fixed Capacity or Load Level/MW | Configuration Situation |

|---|---|---|

| Total load: Pload | 600 | 3 × 200 |

| Thermal power unit: Pst | 600 | 3 × 200 |

| Wind turbine unit: Pvw | 500 | 250 × 2 |

| Photovoltaic unit: Ppv | 150 | 300 × 0.5 |

| Energy storage unit: Pvb | 70 | 1 × 70 |

| Simulation Parameters | Measured Value (a/b) |

|---|---|

| Inertial response time: th/s | 3.562/7.044 |

| RoCoF: /Hz/s | −0.655/0.558 |

| Frequency variation: Δf/Hz | −0.377/0.425 |

| Simulation Parameters | Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | Scenario 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fan controller parameters: Kvw | 0 | 3.55/2.45 | 4.41/3.63 |

| Photovoltaic controller parameters: Kpv | 0.7/0 | 2.31/1.56 | 2.75/1.92 |

| Energy storage controller parameters: Kvb | 0 | 0 | 4.74/4.88 |

| Aspect | Sudden Load Increase | Sudden Load Decrease |

|---|---|---|

| Key Metrics | Scenario 2:

| Scenario 2:

|

| Control Actions |

|

|

| Advantages & Mechanism | 1. Coordinated Inertia: Wind provides instant response, PV supplements with reserves, and BESS engages only for severe deficits. 2. Enhanced System Inertia: This staged activation effectively elevates the overall system inertia support. 3. Optimized Resource Use: Minimizes BESS dependency, reserving it for critical needs. | 1. Hierarchical Response: Wind leads the power reduction, PV cooperates, and BESS acts as a final sink for excess power. 2. Staged Inertia Support: This coordinated strategy provides structured and robust inertia against over-frequency. 3. Improved Stability: Prevents excessive RoCoF and generator tripping, enhancing system resilience. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, T.; Ren, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, M.; Yuan, J. A Coordinated Inertia Support Strategy for Wind–PV–Thermal Storage Systems Considering System Inertia Demand. Energies 2025, 18, 6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246468

Chen T, Ren J, Liu Y, Xu Y, Zhao M, Yuan J. A Coordinated Inertia Support Strategy for Wind–PV–Thermal Storage Systems Considering System Inertia Demand. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246468

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Tie, Junlin Ren, Yue Liu, Yifan Xu, Mingrui Zhao, and Jiaxin Yuan. 2025. "A Coordinated Inertia Support Strategy for Wind–PV–Thermal Storage Systems Considering System Inertia Demand" Energies 18, no. 24: 6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246468

APA StyleChen, T., Ren, J., Liu, Y., Xu, Y., Zhao, M., & Yuan, J. (2025). A Coordinated Inertia Support Strategy for Wind–PV–Thermal Storage Systems Considering System Inertia Demand. Energies, 18(24), 6468. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246468