Line Loss Calculation with Meteorological Dynamic Clustering and Photovoltaic Output Reconstruction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Clustering Algorithms

2.2. Coupling Mechanism Between Meteorological Conditions, PV Power Generation, and Transmission Line Losses

2.2.1. Factors Affecting Fluctuations in PV Output

2.2.2. Effect of Temperature Changes on Line Losses

2.2.3. Power Flow Distribution Adjustment

3. PV Output-Meteorological Coupled Forward-Backward Line Loss Calculation Model

3.1. Data Preprocessing

3.1.1. Anomaly Data Cleaning

3.1.2. Standardized Processing

3.2. Meteorological-Photovoltaic Output Clustering Method Based on LDTW

3.2.1. Dynamic Weight Matrix Construction

3.2.2. Improved SC Algorithm

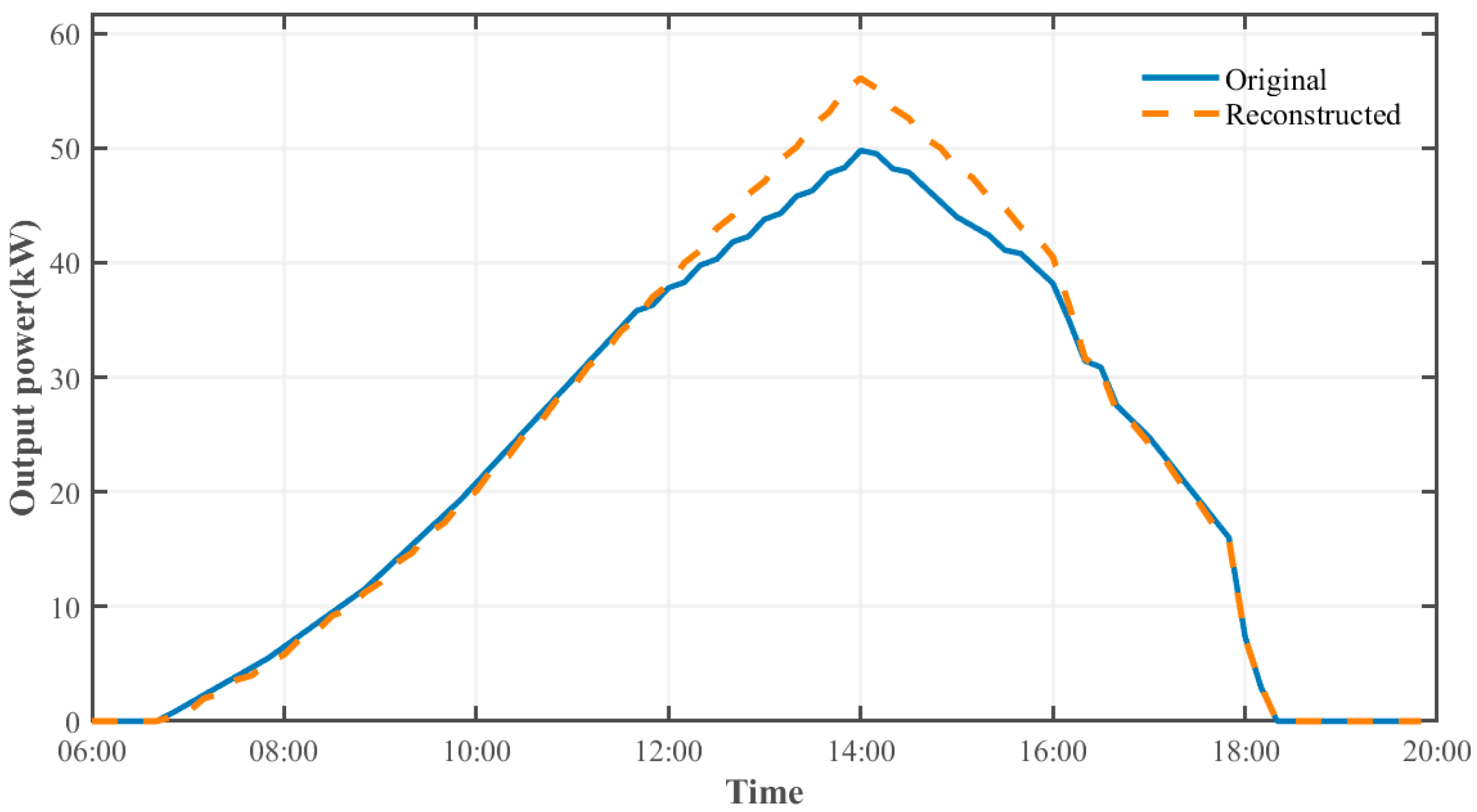

3.2.3. Reconstruction of PV Power Output Curves

3.3. Voltage-Corrected Improved Feedforward Backward Propagation Method

4. Case Study Analysis

4.1. Application of Theoretical Formulas

4.1.1. Application Logic of Theoretical Formulas and Key Parameter Mapping

4.1.2. Verification of Core Formula Application Effectiveness in Typical Scenarios

4.2. Cases Analysis Under Different Weather Conditions

4.3. Quantitative Error Analysis

4.3.1. Fundamental Formula for Error Calculation

4.3.2. Overall Error Statistics

4.4. Experimental Parameter Settings

4.5. Repeatability Verification

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ge, Y.; Dai, S.; Liang, W.; Li, Y.; Song, D.; Chen, J.; Zhou, X.; Shan, Y. Prediction of Distributed Photovoltaic Output Interval Based on Meteorological Fusion and Deep Learning. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 40, 112–120. [Google Scholar]

- He, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, T.; Chen, L. Voltage control strategy for medium-voltage distribution networks with distributed photovoltaic power generation. Electr. Meas. Instrum. 2022, 59, 142–148. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, C.; Ling, W.; Ji, X. Interval power flow for power distribution networks considering uncertain wind power injection. Electr. Meas. Instrum. 2022, 59, 126–132. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Lan, S.; Li, Z. Calculation Method for Losses in Ultra-High Voltage AC Transmission Lines Considering Corona Losses Under Different Weather Conditions. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2023, 182–188+191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Yu, K.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, W.; Wang, Q.; Niu, Y. Calculation Method of Distribution Line Loss Based on Typical Load Curve. Smart Power 2020, 48, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Zhou, X. Calculation of joint extended tidal current for transmission and distribution systems with distributed power sources. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2011, 39, 34–39+44. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Li, Z.; Lu, J. Short-term photovoltaic power prediction based on fusion clustering and BKA-VMD-TCN-BiLSTM. J. Univ. Electron. Sci. Technol. 2025, 54, 592–603. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z. Short-term photovoltaic power prediction by PKO-KELM based on k-means. J. Eng. Therm. Energy Power 2025, 40, 144–152. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Yang, B.; Lu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Qi, L.; Liu, S. Ultra-short-term prediction method for distributed photovoltaic clusters based on spectral clustering and AM-LSTM. Electr. Supply 2023, 40, 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, X. Research on Data-Driven-Based tine oss Calculation Methofor Distribution Network. Process Autom. Instrum. 2025, 46, 111–115+121. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, L. Transmission Line Loss Control Method Considering Dynamic Three phase Unbalance Degree. Microcomput. Appl. 2024, 40, 174–177. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Jiang, T. Parallel Calculation Method for Three-phase Power Flow Based on Vector Instruction Set. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 47, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Li, P.; Zhang, G.; Sun, J.; Qiao, J.; Meng, X. Clustering-based theoretical line loss calculation method for low-voltage transformer areas containing a high percentage of wind power distribution networks. Wind Eng. 2025, 49, 235–248. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Li, S.; Zhao, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, K.; Jiang, Z. Distribution network line loss analysis method based on improved clustering algorithm and isolated forest algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Tian, J.; Zhao, F.; Gao, F. Distribution network current calculation with photovoltaic power. Electr. Meas. Instrum. 2020, 57, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Li, W. Research on photovoltaic output portfolio prediction model based on similar day selection and PCA-LSTM. J. Sol. Energy 2024, 45, 453–461. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, H.; Lian, H.; Liu, J.; Li, Y. Application of Three-Phase Linearized Power Flow and Line Loss Analysis of Distribution Network Driven by Data and Physics Fusion. Electr. Power 2024, 57, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Yang, J.; Gao, M.; Zhao, T.; Li, Y. Power Flow Calculation Method for Distribution Network with Distributed Generation Based on Improved Forward and Back Generation. Autom. Instrum. 2021, 36, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Tang, X.; Shen, J.; Ma, S.; Su, Z.; Ren, J. A spatial clustering method for frequency adaptive spectral clustering in power systems. J. Power Syst. Its Autom. 2025, 37, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, H.; Han, J.; Li, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Han, T.; Feng, T. An accurate calculation method of line loss based on reconstructing a photovoltaic output curve by daily cumulative power generation. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2024, 52, 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, X.; Wang, S.; Su, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, F.; Wu, Z.; Huang, H.; He, Y.; Yan, W. Probabilistic analysis of daily theoretical line loss rate in low-voltage distribution networks. J. Chongqing Univ. 2025, 48, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Spampinato, C.; Valastro, S.; Calogero, G.; Smecca, E.; Mannino, G.; Arena, V.; Balestrini, R.; Sillo, F.; Ciná, L.; La Magna, A.; et al. Improved radicchio seedling growth under CsPbI3 perovskite rooftop in a laboratory-scale greenhouse for Agrivoltaics application. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theoretical Formula (Section 2) | Core Parameters | Data Source (Section 3) | Application Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entropy Weighting Method | Temperature T Humidity H Wind speed V | March 13 (Sunny) 10-minutely meteorological monitoring data (144 points total) | Weighting Allocation for Meteorological Clustering |

| LDTW Curve Reconstruction | Photovoltaic Power Output Sequence PPV(t) | Actual measured active power of the inverter for the day (60 points total) | Repair of abrupt changes in the force curve |

| Improved Forward-Backward Substitution | Node voltage Vb Branch resistance R | IEEE 33 Node System Measured Voltage Data (Node 19 is the PV Access Point) | Voltage Deviation Correction in Line Loss Calculation |

| Date | Average Method (kW) | Curve Reconstruction Method (kW) | Standard Value (kW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.13 | 17.057 | 16.024 | 16.024 |

| 7.23 | 18.095 | 18.214 | 18.241 |

| 11.11 | 15.047 | 15.432 | 15.433 |

| Date | Season | Weather | Core Characteristics (Meteorological—Photovoltaic) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.10 | Winter | Sunny | Low temperature (5 °C), low irradiance (daily average 320 W/m2), stable output |

| 6.15 | Summer | Cloudy | High temperature (32 °C), fluctuating irradiance (intraday variation 25%), fluctuating output |

| 10.8 | Autumn | Rainy | Moderate temperature (18 °C), abrupt irradiance fluctuations (80% increase post-rain) |

| Date | Calculated Line Loss (kW) | OpenDSS Standard Value (kW) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.10 | 14.826 | 14.840 | 0.09 |

| 6.15 | 17.932 | 17.955 | 0.13 |

| 10.8 | 16.518 | 16.541 | 0.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feng, T.; Wei, D.; Li, H.; Han, J.; Zhang, S.; Han, T.; Chai, Y. Line Loss Calculation with Meteorological Dynamic Clustering and Photovoltaic Output Reconstruction. Energies 2025, 18, 6467. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246467

Feng T, Wei D, Li H, Han J, Zhang S, Han T, Chai Y. Line Loss Calculation with Meteorological Dynamic Clustering and Photovoltaic Output Reconstruction. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6467. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246467

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeng, Tao, Dan Wei, Huibin Li, Jinglin Han, Shaobo Zhang, Tianhua Han, and Yuanyuan Chai. 2025. "Line Loss Calculation with Meteorological Dynamic Clustering and Photovoltaic Output Reconstruction" Energies 18, no. 24: 6467. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246467

APA StyleFeng, T., Wei, D., Li, H., Han, J., Zhang, S., Han, T., & Chai, Y. (2025). Line Loss Calculation with Meteorological Dynamic Clustering and Photovoltaic Output Reconstruction. Energies, 18(24), 6467. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246467