1. Introduction

The introduction of various European Union regulations aimed at lowering carbon dioxide emissions has had a significant impact on the energy and heat-generation industries serving residential, domestic, and industrial applications across the European Union [

1]. Based on the European Green Deal and sustainability directives, enterprises must not only limit greenhouse gas emissions but also gradually phase out fossil fuels [

2]. This creates a growing need to introduce energy-efficient and environmentally friendly solutions. One promising area is the use of ionic liquids in the field of high-temperature absorption heat pumps (AHPs).

To this date, an expanding body of literature addresses the use of ionic liquids as alternatives to conventional working fluids in absorption heat pumps [

3,

4,

5]. Thus far, investigations have focused mainly on low-capacity devices delivering supply temperatures in the 45–65 °C range [

4,

5]. Kühn et al. [

3] conducted a review of ionic liquids as novel absorbents for thermally driven chillers and heat pumps. The review emphasized the negligible vapor pressure and tunability of solvent–solute interactions. Wang and Infante Ferreira conducted an analysis of NH

3–IL absorption cycles, emphasizing that the majority of prior implementations target ≤ 65 °C delivery and offering guidance on IL selection at the cycle level. Wang’s monograph serves to further consolidate the fundamentals and applications [

4,

5]. The experimental and correlative foundations for NH

3 + IL mixtures were established by Yokozeki and Shiflett. VLE measurements were provided, and Redlich–Kwong/EOS treatments were modified, enabling cycle modeling at elevated temperatures [

6,

7,

8]. Concurrently, Ren et al. reported vapor pressures, excess enthalpies, and heat capacities for IL-containing binaries [

9]. It is evident that researchers have not considered the impact of increasing the temperature of hot water. Additionally, previous work on AHP with ammonia–ionic liquids does not provide quantitative, verifiable criteria for selecting ionic liquids for use at high temperatures (>100 °C). In particular, there is a lack of correlation between the properties of ionic liquids and the three key design requirements of eliminating rectification, reducing generator power due to the low specific heat capacity of the mixture, and maintaining exothermicity in the absorption process within a useful concentration and temperature range. Analyzing fast-growing energy demands, particularly in the industrial sector, it is necessary to extend these studies to higher-capacity devices capable of delivering supply temperatures above 100 °C. This kind of solution can be pivotal in the industry, where heat demand is high and there is simultaneous pressure to reduce emissions and limit fossil-fuel consumption. In this context, the present study establishes a steady-state thermodynamic model of the NH

3–IL cycle for a heating system operating at temperatures above 100 °C. This is achieved by using well-established property frameworks from the literature to quantitatively define IL selection criteria, such as negligible volatility, low solution Cp, and a strongly negative excess enthalpy at absorber temperatures. The study also benchmarks literature-reported ILs against the NH

3–H

2O pair, providing practical guidance on selecting an absorbent for industrial applications.

The deployment of absorption heat pumps in industrial facilities and factories is particularly important due to the increasingly constrained availability of electricity. With global electricity demand rising, the industry faces difficulties in securing additional electricity supply. Moreover, many plants experience grid congestion, which limits the addition of electrically driven systems. Consequently, absorption heat pumps in which the mechanical compressor is replaced with a thermally driven sorption compressor are an attractive alternative. They can be driven by an existing heat source, such as a steam boiler, which is advantageous from a capital expenditure perspective. This solution, combined with an absorption heat pump, does not significantly burden the power grid, which is an essential consideration for sustainable development.

Traditionally, the absorption heat pumps considered in this paper have ammonia–water and lithium bromide–water as the working pairs. The NH3–H2O system, which is commonly used and is considered as a base for this paper, has several limitations that are particularly significant at high-temperature heating systems. The volatility of water means that vapors leaving the generator must be purified, generating internal heat/cooling cycles, exergy losses, and a practical limit on the purity of the medium. This narrows the possible temperature difference and the achievable temperature in the absorber/condenser. The thermodynamics of the NH3–H2O equilibrium generate high solution circulation ratios: the solubility of NH3 in water decreases sharply with temperature. Therefore, maintain the required vapor purity, large flows of strong/weak solution must be circulated. This increases the size of the exchangers and pumping costs. The high heat capacity of the water–ammonia solution results in a large proportion of sensible heat in the generator and absorber, thereby increasing the required heat. Consequently, at water-heating temperatures above 100 °C, NH3–H2O systems incur significant losses and design limitations, prompting the search for alternative absorbents. Nevertheless, the ionic liquids under discussion in this paper, as outlined in the existing literature, have the potential to offer a number of advantages over conventional solutions based on standard working pairs. A principal property that could be considered an advantage is that they can be engineered to meet specific physicochemical and thermodynamic requirements, thereby affording engineers and scientists greater flexibility in tailoring parameters to the needs of a given process. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that the maintenance of high thermal stability and low vapor pressure of ionic liquids is a possibility, which could in turn allow operation at higher temperatures. These parameters could be of critical importance for industrial processes that necessitate elevated water-supply temperatures for process equipment.

At the same time, further research is needed to optimize or find proper ionic liquids for achieving the highest possible coefficient of performance (COP), especially in high-temperature applications. The potential of ionic liquids in this area is promising; however, satisfactory results have so far only been achieved in systems with relatively low supply temperatures—for domestic usage. This article presents the possibilities, methods, and proposals for employing ionic liquids in high-temperature absorption heat pumps. The optimal physicochemical parameters of these liquids are also considered to ensure their effectiveness in industrial processes while minimizing energy use and CO2 emissions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General

All quantitative analyses were performed in custom Microsoft Excel workbooks developed by the authors. Input parameters were taken exclusively from papers, standards, and technical documents listed in the References. When multiple sources reported the same quantity, priority was given to primary literature and international/industry standards; secondary sources were used only for cross-checks. When sources provided ranges, the mid-point was used for central estimates. No stochastic or machine-learning methods were used; all results arise from deterministic spreadsheet calculations.

Generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) was used solely to render publication quality figures from the precomputed Excel/CSV table. Figures have been generated by programs written in Python (version 3.14) language.

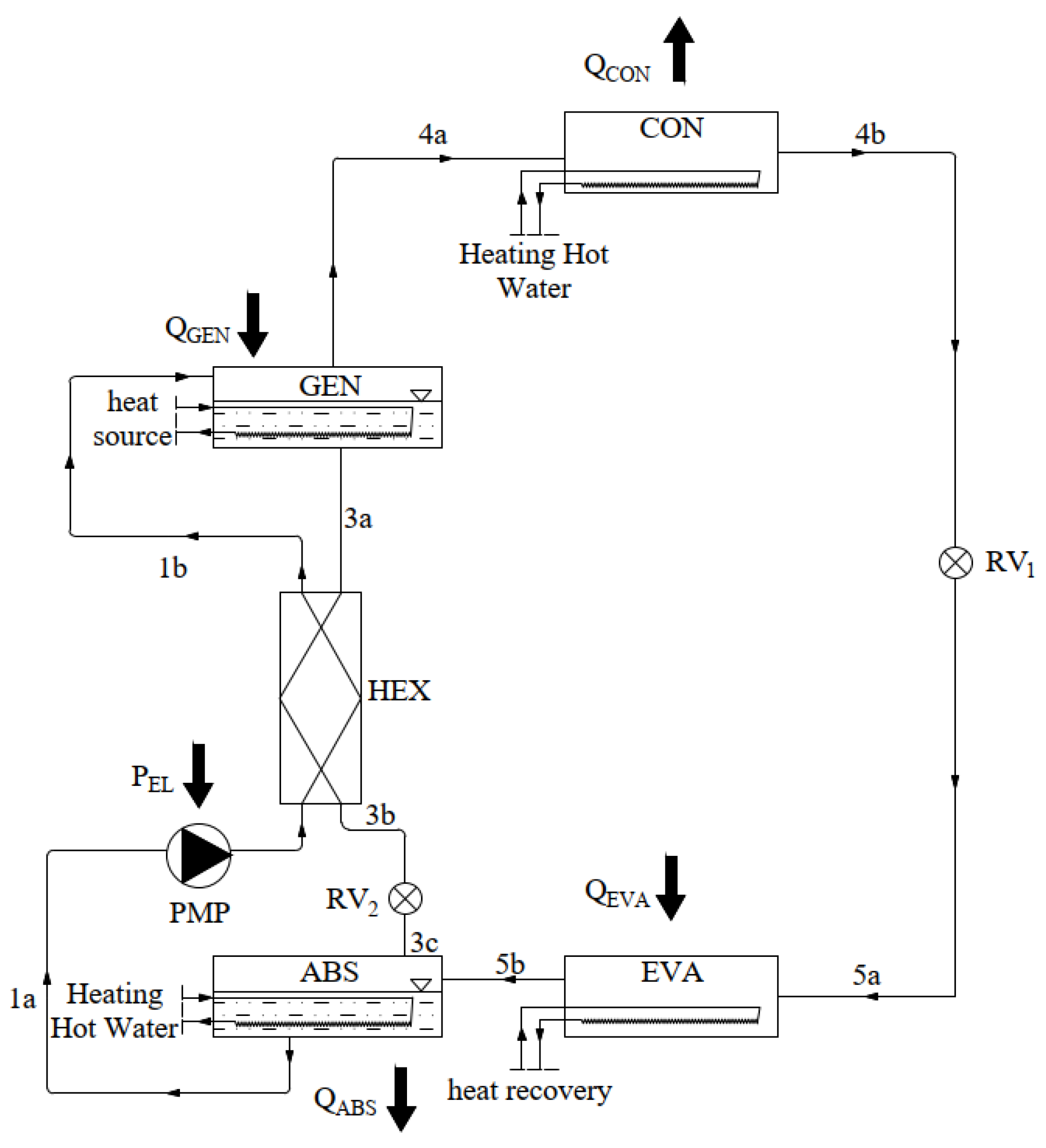

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 were drawn by the authors using Autodesk AutoCAD software (version 2025). There are no restrictions on material availability beyond standard licensing of third-party sources cited in the References.

All parameters for ionic liquids were taken from peer-reviewed correlations within their reported T-x validity ranges. The parameters have not been fitted. From a design standpoint, for a high-temperature absorption heat pump, the following requirements have been targeted: absorbents with negligible vapor pressure, low mass-based heat capacity and strongly negative excess enthalpy, and NRTL parameterizations that yield ammonia-strong vapor at generator temperatures. The selected ILs meet these criteria.

2.2. Example Model Validation

2.2.1. VLE

The NRTL-based predictions for VLE were overlaid with experimental VLE from Yokozeki & Shiflett [

6]. According to this, Mean Absolute Percentage Error has been calculated to 4.71%, which shows

Table 1.

2.2.2. Specific Heat Capacity

The Group additivity method and Linear T-correlation method predictions for specific heat capacity were overlaid with experimental SHC data from ILThermo [

10]. According to this, Mean Absolute Percentage Error has been calculated to 1.06% for Group additivity method as shown in [

11] and 0.22% for Linear T-correlation method as shown in [

4]. Values which are the base for this calculation are shown in

Table 2.

2.3. Limitation of the Present Study

This work presents a steady-state thermodynamic cycle model for a high-temperature ammonia–ionic liquid absorption heat pump, based on property frameworks from the literature (NRTL for vapor–liquid equilibrium (VLE), modified Redlich–Kwong for vapor pressures, and group-contribution heat capacities). The main limitations are as follows:

Data and models: The model parameters (NRTL/EOS/Cp) were obtained from correlations in the literature, with limited validity with respect to temperature and composition. The quantitative model form and parameter uncertainties were not propagated to the cycle metrics.

Scope of fluids: The research covers a set of ILs used as a base for other studies (e.g., [emim][SCN], [emim][EtSO4], [bmim][PF6]). Some EOS parameters are incomplete due to lack of information in the literature.

Cycle idealizations: Pressure drops, heat losses, rectifier behavior, and dynamic mass-transfer resistances are assumed as neglected. Boundary conditions are fixed to representative industrial temperatures—parameters are assumed to be constant.

Mixture thermodynamics: Excess enthalpy is computed from simplified correlations; composition-dependent Cp is approximated by mass-weighted averages.

Engineering aspects: No hydraulic design, viscosity impact, material compatibility, IL stability/degradation, environmental, safety, or cost considerations are quantified.

Parameters out of scope: circulation ratio, COP, and flow rates have not been calculated.

2.4. Thermodynamic Model Structure

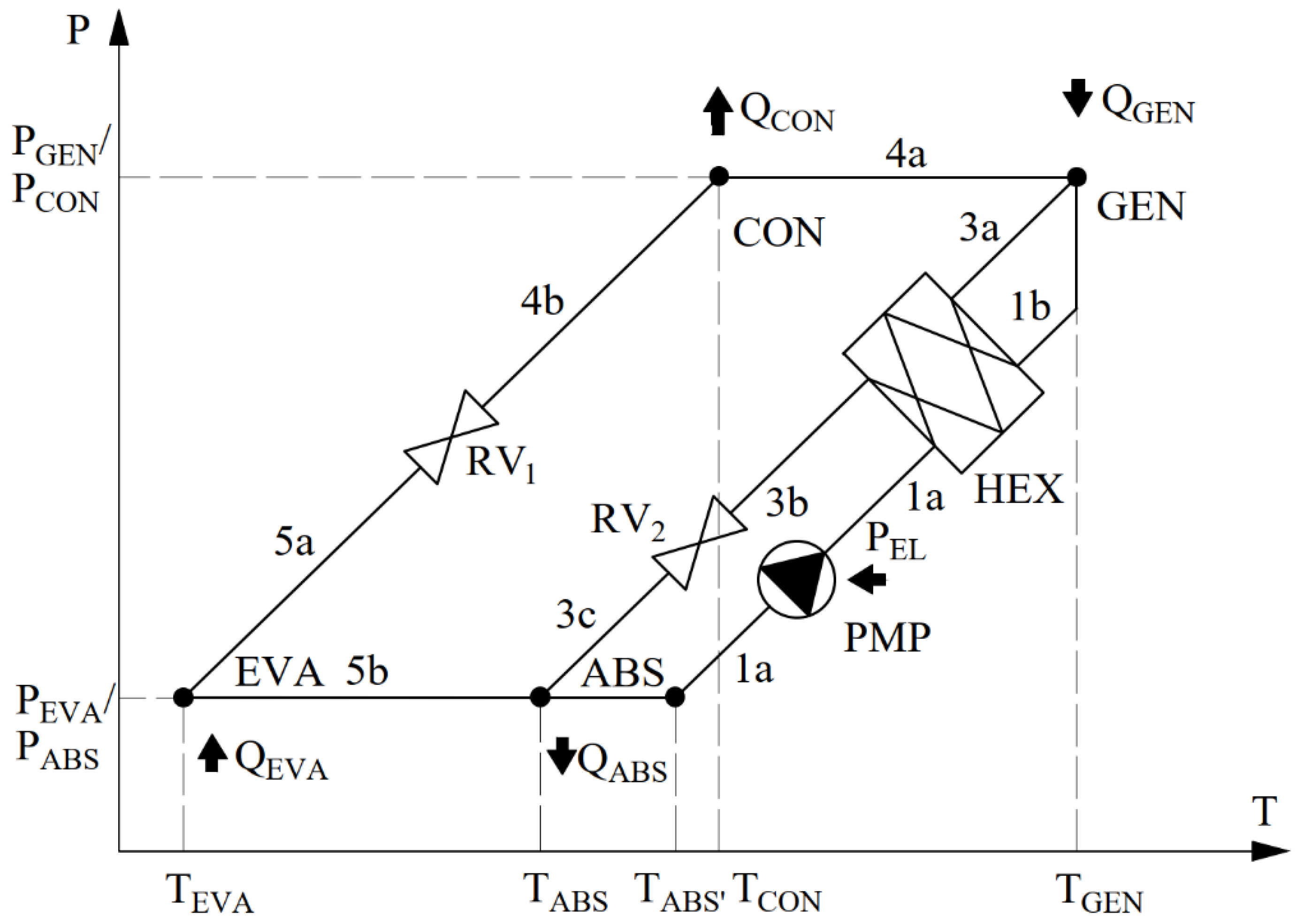

This study analyzes an absorption heat pump system operating in a conventional configuration, comprising an absorber (ABS), a generator (GEN), a condenser (CON), an evaporator (EVA), circulation pumps (PMP), and a heat exchanger (HEX).

The description of the individual components of the absorption heat pump is as follows. In the analysis below, processes occurring in the rectifying section (KOR) are omitted.

Absorber (ABS): In the absorber, refrigerant vapor returning from the evaporator (EVA) is absorbed by the weak solution, forming a strong solution. This solution is then conveyed via line (1a) by the circulation pumps (PMP) to the heat exchanger (HEX) and subsequently to the generator (GEN). Absorption of the refrigerant by the weak solution in the absorber releases heat (QABS—an exothermic process), which is used to heat the heating water via a heat exchanger located within the absorber; this is essential for proper system operation.

Generator (GEN): The strong solution transported from the absorber (1b) is heated in a heat exchanger supplied with energy from an external heat source (QGEN). In practice, steam or hot flue gases from combustion processes are commonly used as heating media; electric heaters or other high-temperature sources are also possible. Heat exchange between the high-temperature source and the strong solution results in desorption (evaporation) and significant heating of the refrigerant (e.g., ammonia), a constituent of the working pair. Consequently, the solution splits into two streams: a vapor (refrigerant) and a liquid (weak absorbent solution). The refrigerant is directed to the condenser (4a–CON), while the weak solution returns to the absorber via the heat exchanger (3a, 3b–HEX) and the expansion valve (3c–RV2).

Heat Exchanger (HEX): A typical liquid–liquid heat exchanger connected to the absorber and generator via piping. The weak solution returning from the generator (3a) transfers heat to the strong solution (1a), thereby preheating it prior to further heating in the generator.

Condenser (CON): The refrigerant vapor separated from the strong solution in the generator is cooled and condensed in the condenser, transferring heat to the heating medium (e.g., heating hot water). The condensed refrigerant is then routed to the evaporator (4b) via the expansion valve (RV1).

Evaporator (EVA): In the evaporator, the refrigerant is re-evaporated by heat from the low-temperature heat source (e.g., process cooling water). The evaporated refrigerant returns via line (5b) to the absorber, where the cycle restarts.

2.5. Thermodynamic Aspects of the Model

The thermodynamic model of this system is based on an absorption cycle, in which heat is turned from a lower to a higher temperature with minimal mechanical-energy input, in contrast to electrically driven compressor heat pumps [

12]. Using ionic liquids as the absorbent—i.e., as part of the working pair—can enable higher efficiency and higher heating-water temperatures owing to favorable physicochemical properties (e.g., high chemical and thermal stability) and the ability to adapt liquid parameters to the specific requirements of the process. In this system, ammonia acts as the refrigerant and the ionic liquid acts as the absorbent. Together, they form strong solutions. Since ammonia boils at −33.35 °C at atmospheric pressure [

13], it is assumed to be more volatile than the ionic-liquid component of the working pair. The process is depicted in the p–t diagram below.

In what follows, the system is analyzed primarily from the standpoint of the highest achievable heating-water temperatures. To provide a detailed discussion of the thermodynamic processes, we treat them on a component-by-component basis of the absorption heat pump.

Generator (GEN)

Thermophysical parameters of the fluids: The conditions in the generator should enable the heating water to reach a high supply temperature (>100 °C); the following assumptions are adopted:

A heating medium at 135 °C is supplied to the generator heat exchanger; the temperature of the fluid in the generator is 130 °C. It was assumed that the differential temperature between the heating medium in the generator and the strong solution should be at least 5 °C. A temperature of 130 °C was selected to maximize overheating heat gains in ammonia. The temperature of this element is determined by commercially available heat exchange devices, and can be increased if the permissible temperature of each generator element exceeds the design temperature.

The circulation pump (PMP) raises the pressure from the absorber to the target liquid pressure in the generator; the pressure is further affected by the heat supplied to the generator. After ammonia evaporation, isochoric heating increases its pressure. If only pure ammonia—or a mixture with similar thermophysical properties—was evaporated, the vapor would have to be compressed to about 72.83 bar, the saturation pressure corresponding to 108 °C. The pressure in this component has been selected to enable the transfer of heat from the condensation of ammonia to the high-temperature heating-water system (>100 °C). It is imperative that the differential temperature between the heating-water system and the condensation temperature of ammonia is a minimum of 8 °C. A reduction in the quantity may be possible (to 5 °C), although this would result in an increase in the size of the condenser.

Process description: The strong solution—a stable mixture of ammonia and an ionic liquid—is pumped by the circulation pump (PMP) into the generator. For correct operation and to avoid rectification, one component—here, ammonia—should evaporate at a lower temperature than the ionic liquid [

12], which is assumed based on the current knowledge of ionic liquids [

14]. Upon heat addition, the strong solution undergoes distillation and splits into two independent fluids; the evaporated refrigerant (ammonia vapor) carries away heat. To ensure evaporation of the cleanest possible refrigerant (ammonia) and eliminate rectification, the ionic liquid must have a much lower volatility than ammonia and remain liquid at the generator’s pressure and temperature. Saturation vapor-pressure parameters for the ammonia/ionic-liquid system are given in

Section 4.2. After refrigerant evaporation in the generator and its appropriate purification (i.e., removal of the ionic-liquid fraction from the vapor), the AHP cycle divides into two independent streams: the weak solution and the refrigerant.

Heat Exchanger (HEX)

Thermophysical parameters of the fluids:

The weak solution, consisting predominantly of the ionic liquid, is at a high temperature attained in the generator. For analysis, 130 °C at the HEX inlet and 90 °C at the outlet are assumed. The liquid pressure follows the generator pressure; its exact value depends on the ionic liquid used and its thermophysical properties. The temperature of the weak solution has been taken directly from that of the fluid in the generator. It is assumed that the fluid in pipeline connecting HEX and GEN will not exhibit any cooling. The outlet temperature of the weak solution in the heat exchanger is assumed to be directly proportional to the differential temperature between the weak solution outlet and the strong solution inlet. It was hypothesized that this differential temperature would be a of 7 °C.

The strong solution—a stable mixture of ionic liquid and ammonia—enters the HEX at a temperature determined by the processes in the absorber and the physicochemical characteristics of that component. The temperature of 83 °C is taken directly from the strong solution outlet of the absorber. It is assumed that the fluid in pipeline connecting HEX and ABS will not exhibit any cooling. Additionally, it is assumed that upon leaving the HEX, the strong solution’s temperature is 10 °C below the weak solution inlet temperature, i.e., 120 °C. A decrease in differential temperature will result in an increase in the size of the HEX. The liquid pressure follows the circulation pump discharge and thus the generator pressure (GEN).

Process description: The weak solution is routed to the HEX, where it transfers heat to the strong solution, thereby reducing its own temperature. To quantify the heat transferred to the strong solution, the ionic liquid’s physicochemical and thermodynamic properties are required—specifically, specific heat, thermal conductivity, kinematic viscosity, enthalpy, and density (or specific volume). These parameters and their determination are discussed in the next section. After passing through the HEX, the weak solution (liquid) reaches the expansion valve, where its pressure is reduced to the absorber pressure.

The strong solution is transported by the circulation pump to the HEX and then to the generator. Partial ammonia evaporation from the strong solution may occur in the HEX; however, it is essential to maximize recovery of the heat contained in the ionic liquid (weak solution) discharged to the absorber. To correctly describe heat exchange between the ionic liquid and the ionic-liquid–ammonia mixture, the properties of the considered solution must be known; as with the ionic liquid, the required parameters are specific heat, thermal conductivity, kinematic viscosity, enthalpy, and specific volume.

Condenser (CON)

Thermophysical parameters of the fluids:

The refrigerant (ammonia) enters the condenser as a vapor at the high temperature (130 °C) and pressure established in the generator. Any pressure loss or temperature decrease is assumed to occur in the pipelines between GEN and CON. While transferring heat to the heating water, the ammonia condenses at the saturation temperature corresponding to the high-side pressure (Tcond > 100 °C), thereafter, the condensate may be subcooled to about 90 °C. For subsequent analysis, the condenser outlet ammonia is taken as 90 °C (subcooled liquid) at a pressure equal to the generator (high-side) pressure. It is assumed that the differential temperature between the heating water inlet and the ammonia outlet should be at least 10 °C. Note that, to meet the heating-water requirements, the high-side pressure must not be lower than the saturation pressure, which corresponds to a temperature of not less than 104 °C.

The heating water changes from 80 °C to 100 °C across the condenser. The inlet temperature is taken directly from the outlet temperature of the heating water in the absorber. The outlet temperature in the condenser must be at least 100 °C to fulfill the hypothesis of this paper. The pressure of the heating water is not analyzed in the present paper and is therefore omitted.

Process description:

In the condenser, high-temperature, high-pressure ammonia vapor transfers heat to the heating water, raising its temperature from 80 °C to 100 °C. Condensation occurs at the saturation temperature Tcond > 100 °C, followed by possible subcooling of the liquid to about 90 °C.

Evaporator (EVA)

Thermophysical parameters of the fluids:

Immediately after leaving the condenser, the refrigerant passes the expansion valve (RV1), where its pressure is reduced to a value that enables evaporation by heat from the low-temperature source. An evaporation pressure of 11.36 bar, corresponding to 30 °C, is assumed and used in subsequent analyses. The temperature and pressure of ammonia are assumed to be 5 °C lower in any part of the evaporator than in the heat-recovery water flowing through it. It is assumed that with heat supplied from the low-temperature source, the refrigerant fully evaporates to dry saturated vapor (no superheat).

The heat-recovery water flowing through the evaporator heat exchanger is cooled from 40 °C to 35 °C. The temperature of the heat-recovery system is set at 40 °C, which is the standard return temperature for cooling systems in the beverage industry. Pressure of heat-recovery water is not analyzed in the present paper and is therefore omitted.

Process description:

After throttling at the expansion valve between the condenser and the evaporator to the evaporation pressure, the refrigerant enters the evaporator and absorbs heat from the low-temperature source. As heat is absorbed, ammonia evaporates to saturated vapor, which is routed to the absorber.

Absorber (ABS)

Thermophysical parameters of the fluids:

The refrigerant, in the vapor phase, enters the absorber directly from the evaporator. Its temperature and pressure are assumed to be unchanged at 30 °C and 11.36 bar—any pressure loss or temperature decrease or increase is assumed to occur in the pipelines between EVA and ABS.

The weak solution, as a liquid, entering the absorber immediately after the expansion valve is assumed to be at 90 °C and 11.36 bar. To prevent ammonia from flashing out of the strong solution in the absorber, the absorbent (ionic liquid) must markedly depress the ammonia vapor pressure at the absorber temperature.

The mixture temperature (strong solution) after absorption and heat removal is assumed to be 83 °C, with the pressure remaining 11.36 bar. It is hypothesized that the temperature differential between the weak solution outlet and the heating hot water inlet must be a minimum of 8 °C. It is hypothesized that lower values could be impacted by an increase in absorbers.

The heating water across the absorber’s heat exchanger changes from 75 °C to 80 °C. It is assumed that the inlet temperature will be maintained at a differential temperature of 20–25 °C between the supply and return flow in a heating-water system. Its pressure is not material in the present analysis and is omitted.

Process description:

In the absorber, the weak solution (liquid) contacts the ammonia vapor from the evaporator. Absorption is exothermic; the absorber is therefore cooled by the returning heating water, raising its temperature from 75 °C to 80 °C. The absorber is the first element where heat is transferred from the working fluid to the heating loop [

12].

4. Results

To verify the feasibility of using selected ionic liquids in the working mixtures of high-temperature absorption heat pumps, a series of calculations were performed as indicated in the subsections below. The parameters of the individual ionic liquids analyzed are shown in

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7. In

Table 3, viscosity and density parameters have been selected for a temperature of 25 °C and atmospheric pressure of 101.3 kPa. The determination of the vapor pressure of the ionic liquid was carried out on the basis of the works of Yokozeki and Shiflett [

6,

7,

8]. Liquid–vapor equilibrium was implemented using the equations of the NRTL model. The specific heat of the ionic liquids was determined according to the formulas indicated in the article by Meng Wang and Carlos A. Infante Ferreira [

4], and a modification of the approach of Ruzicka V., Domalski E. S., as indicated in [

11] by Ramesh L. Gardas and Joao A. P. Coutinho. The excess enthalpy was determined from two relations, namely the NRTL (Non-Random Two-Liquid) method with the Gibbs–Helmholtz relation [

19] and the Redlich–Kister equation [

17,

18]. Each set of results is shown in comparison with water, which, together with ammonia, constitutes the classical working mixture used in absorption heat pump systems. The parameters of the ionic liquids for the calculations were taken from the respective sources, i.e., [

4,

6,

9,

11]. The ionic liquids which have been considered in this paper are as follows: 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium thiocyanate ([emim][SCN]), 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium ethyl sulfate ([emim][EtSO

4]), 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate ([bmim][PF

6]), 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)imide ([hmim][NTf

2]). These liquids are well known, and information about their properties can easily be found in a wide range of publications. This is why they have been selected for this research project.

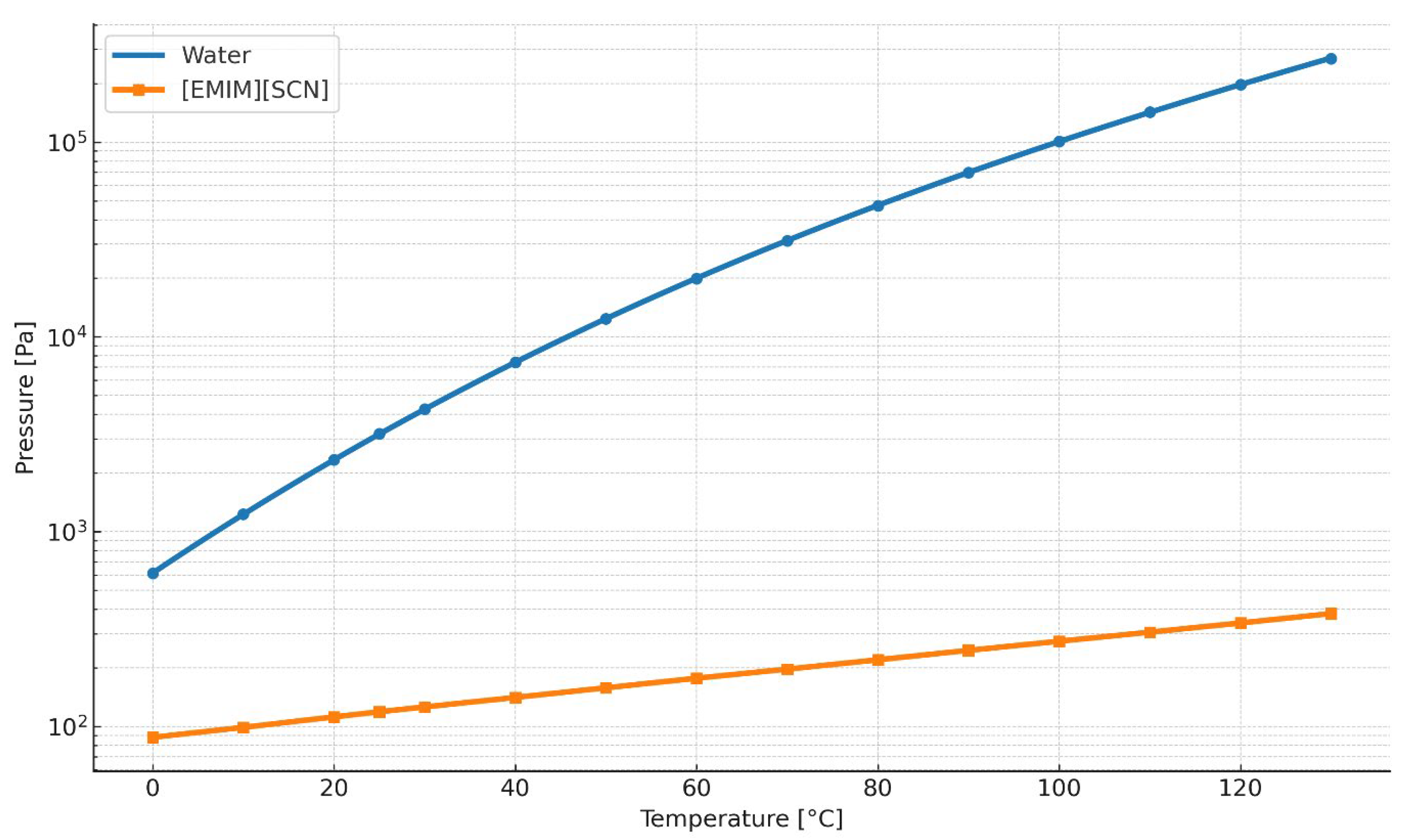

4.1. Vapor Pressure of Pure Ionic Liquids

For the analysis of the vapor pressure of ionic liquids, the substance 1-Ethyl-3-methyl-imidazolium-thiocyanate [emim][SCN] was considered. The calculation results are given in

Table 8 and illustrated in

Figure 3.

Accordingly, it may be stated unequivocally that the vapor pressure of ionic liquids is virtually zero, which implies that, over the entire range of engineering applications, a vacuum would be required to induce evaporation of this substance.

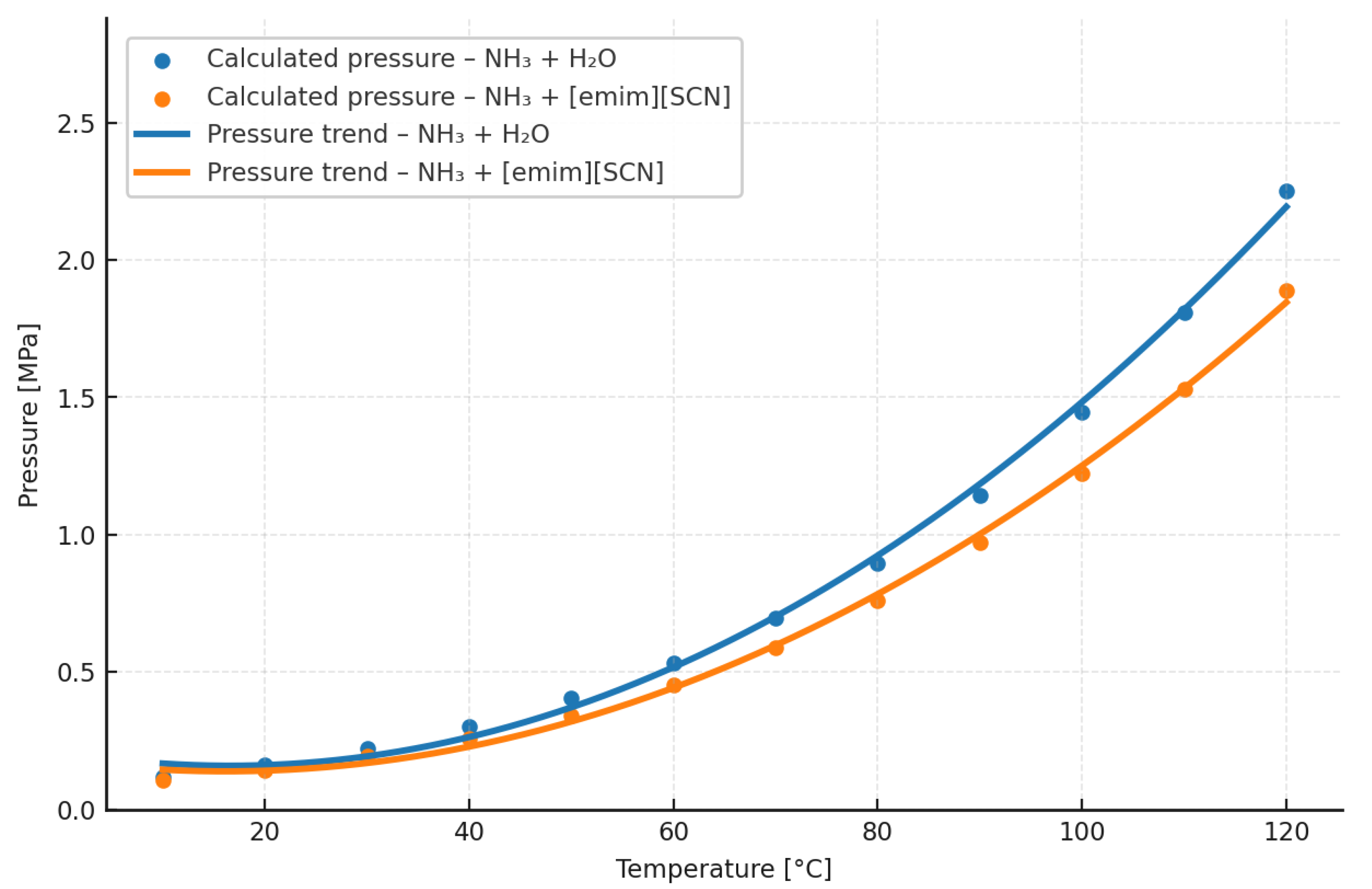

4.2. Vapor Pressure of Working-Fluid Solutions

For the analysis of the vapor pressure of working-fluid mixtures with ionic liquids, the substance 1-Ethyl-3-methyl-imidazolium-thiocyanate [emim][SCN] in mixture with ammonia was considered. A mole fraction of ammonia x

1 = 0.4 was assumed. The calculation results are presented in

Table 9 and illustrated in

Figure 4.

Based on the results from

Table 9 and

Table 10 and

Figure 4, it can be inferred that the vapor pressure of the ammonia–IL mixture, in the operating temperature range from 283.15 K to 323.15 K, is greater than the vapor pressure of the ammonia–water working fluid used in absorption heat pumps. Above 323.15 K, the pressure of the IL-based working fluid is lower than that of the water-based one. At the same time, it should be noted that the higher pressure of the ammonia (NH

3)/[emim][SCN] mixture at low temperatures mainly results from the high values of γ

1 and γ

2 calculated by the NRTL model.

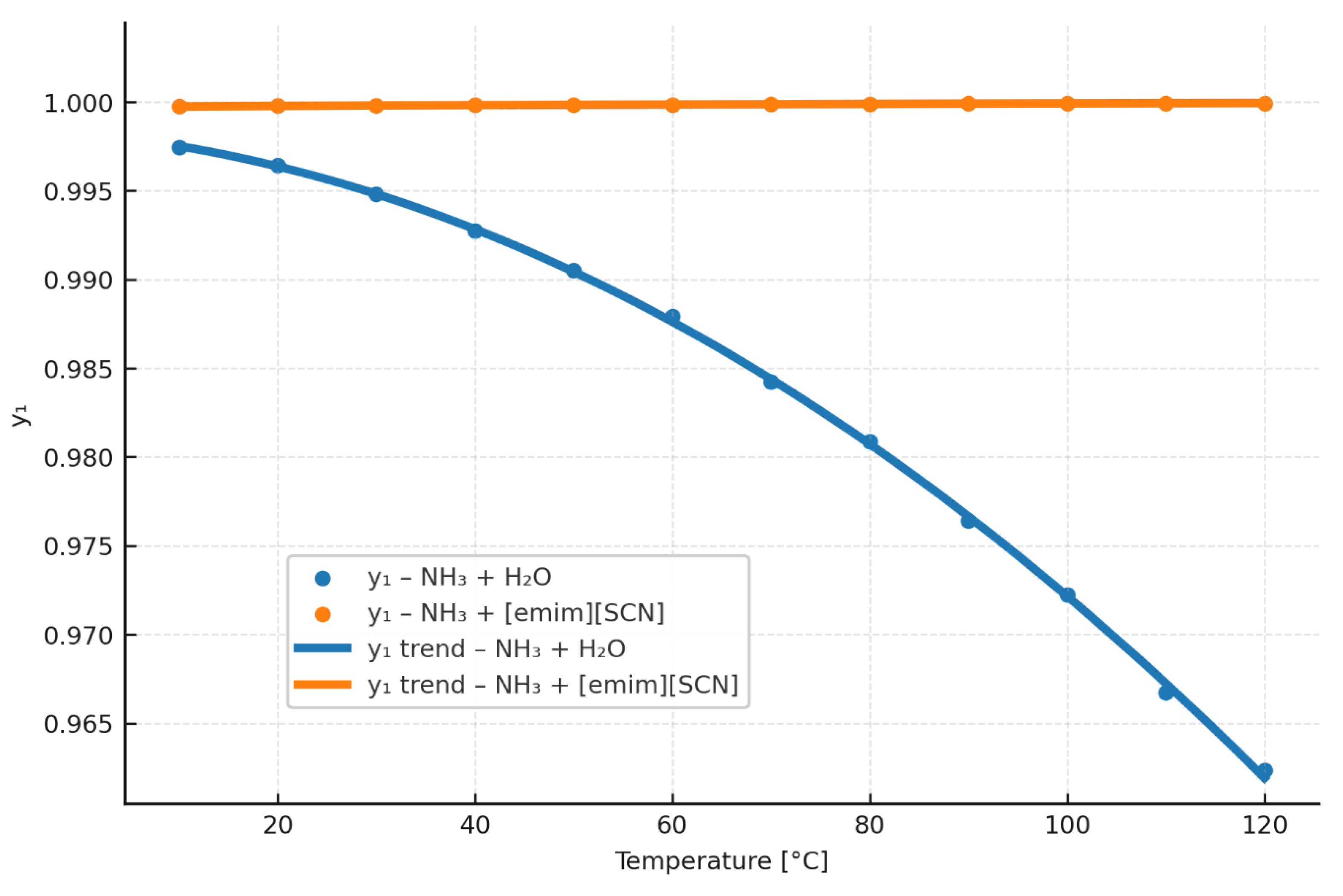

4.3. Vapor–Liquid Equilibrium (VLE)

According to the calculations presented in

Section 4.2, the differences in vapor pressure for the NH

3/[emim][SCN] mixture and for NH

3/H

2O [

23] are relatively small. However, a more pertinent parameter from the standpoint of high-temperature absorption heat pumps is the composition of the vapor observed above the working-liquid mixture in the GEN. According to

Figure 5, the vapor above the working fluid consisting of [emim][SCN] and ammonia is practically pure ammonia. These results indicate that, in AHP systems based on an NH

3/IL mixture, it is reasonable to forgo the rectification process even at high temperatures in the generator, which are required in high-temperature absorption heat pumps. By eliminating rectification, the system increases its COP, and it does not decline appreciably with increasing generator temperature.

Table 11 contains a wide range of data for the molar content of ammonia (y

1) in the vapor in the GEN.

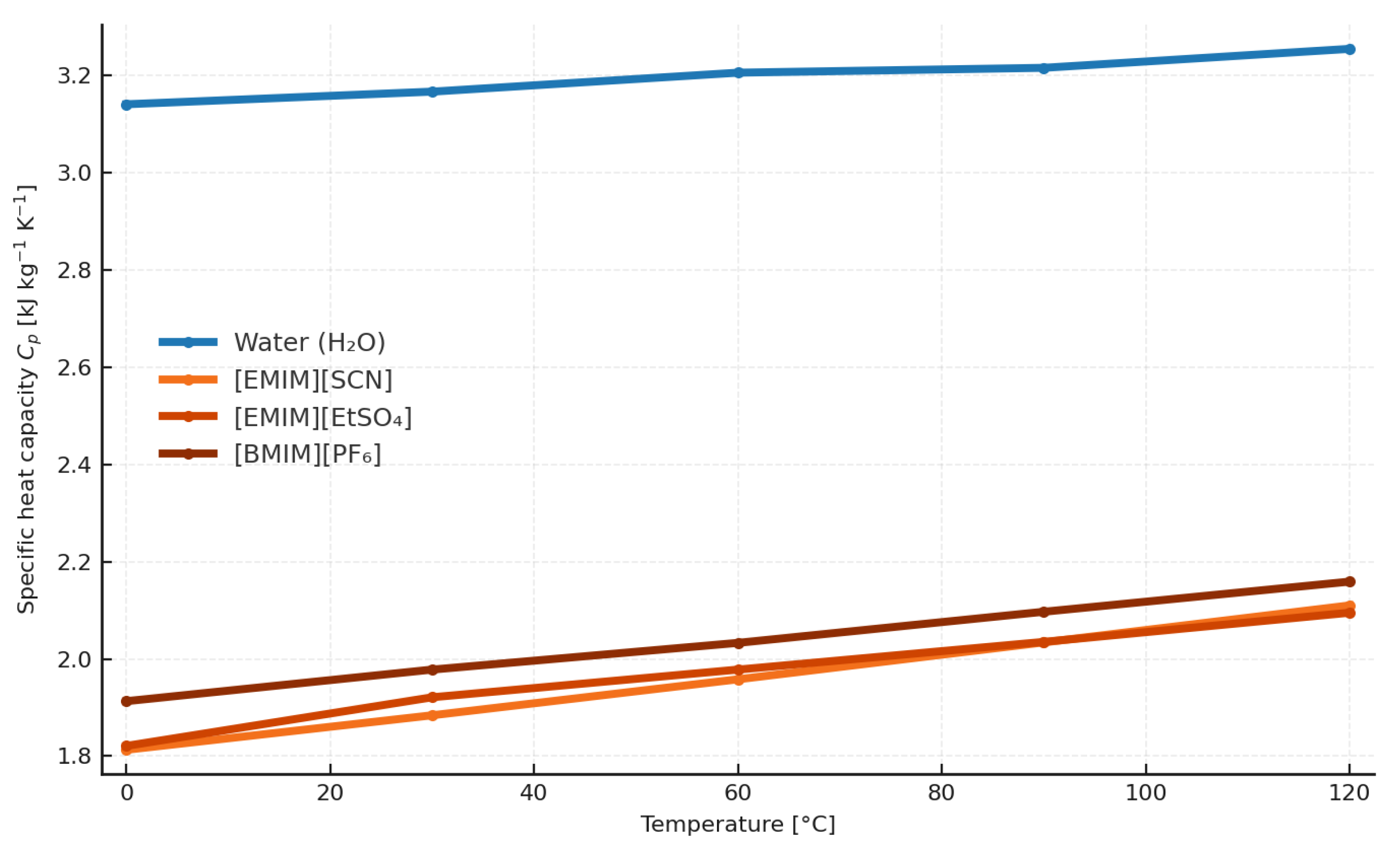

4.4. Specific Heat Capacity of Ionic Liquids

The specific heat capacity of an ionic liquid is a parameter defined primarily on the basis of experimental studies. Based on experimental data [

24], it has been assessed that the specific heat capacity depends on the liquid temperature and, to a very small extent, on its pressure. Characteristic, interpolated values as a function of pressure are given in

Table 12. At the same time, the determination of specific heat can be performed using empirical computational models based on the structure presented in

Section 3.1. The results of calculations using the method indicated in the article by Meng Wang and Carlos A. Infante Ferreira [

4] are shown in

Table 13. Calculations based on the formula of Ruzicka V., Domalski E. S., as adapted by Ramesh L. Gardas and Joao A. P. Coutinho [

11], are also shown in

Table 13 and in

Figure 6.

Based on the results, it can be stated unequivocally that, in calculating the specific heat of ionic liquids, variations in this parameter due to pressure changes are negligible.

Accordingly, it follows that the two methods proposed in this article for use in thermodynamic calculations for determining specific heat capacity are equivalent and provide similar results over the temperature range 273.15–393.15 K. The maximum observed difference in results is 6.78%. Relative to water, the specific heat of ionic liquids on a molar basis is 350% to 600% higher than that of water. By contrast, the specific heat capacity of the analyzed substances on a mass basis (per gram) is 63% to 52% lower than that of water.

4.5. Specific Heat Capacity of Working-Fluid Solutions with Ionic Liquids

The specific heat capacity of solutions of an ionic liquid and ammonia could be calculated using the formula below [

4], which takes the mass fraction of the given substance into account. This value is necessary for calculating the enthalpy of the mixture including mixtures with ionic liquids.

The calculated values for the ammonia–ionic-liquid mixtures (for each ionic liquid) and for ammonia–water are given in

Table 14. A 50/50 mass solution is considered, and the specific heat (

Cp) parameters are assumed without considering the mixture

From the calculated data, illustrated in

Figure 6, it can be concluded with certainty that ionic-liquid-based mixtures have a significantly lower specific heat at the same mass fraction.

4.6. Excess Enthalpy

The excess enthalpy is a key thermodynamic parameter for working mixtures used in absorption heat pumps, because it enters directly into the generator heat balance and thus determines the required generator duty (QGEN) and the achievable COP.

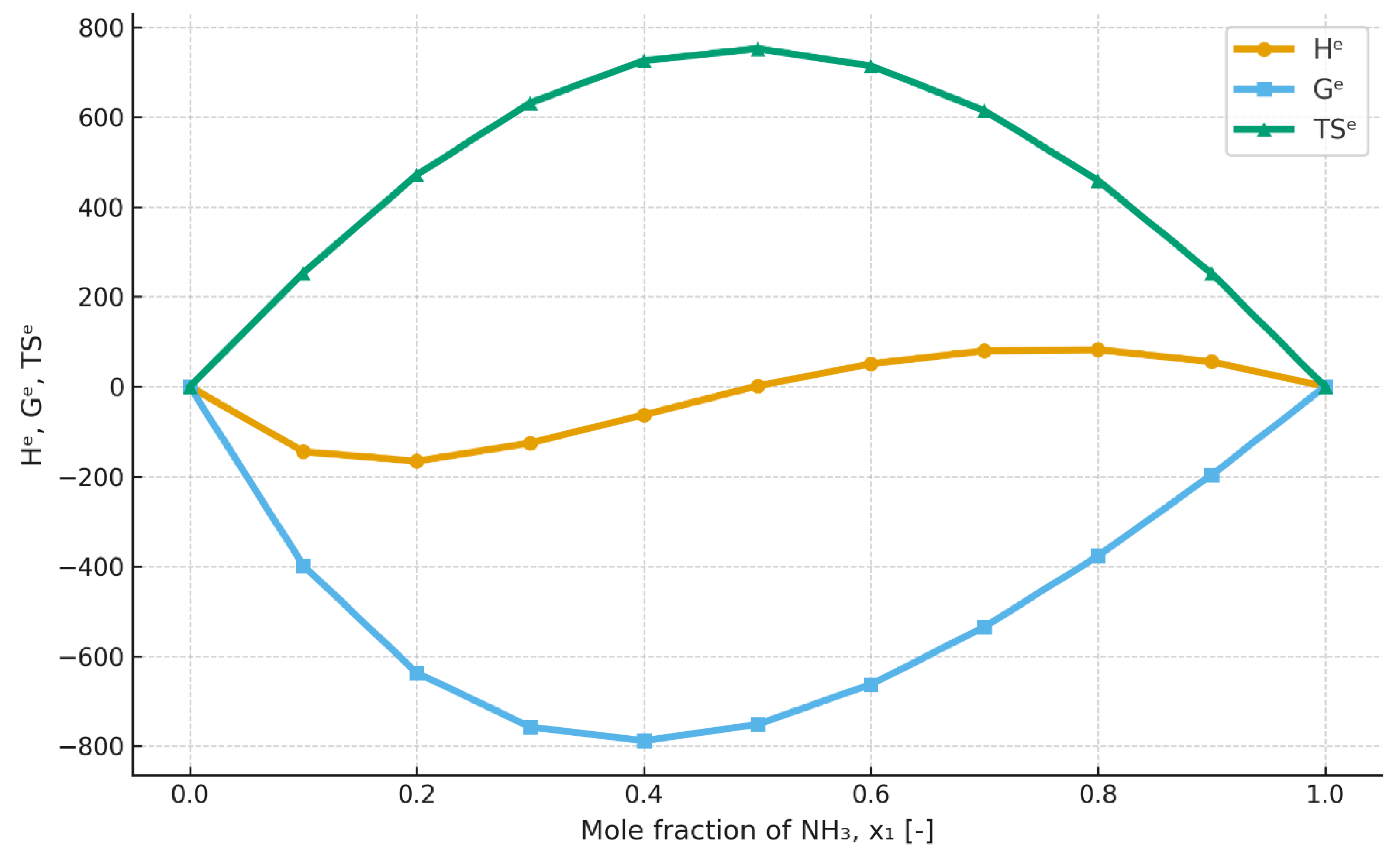

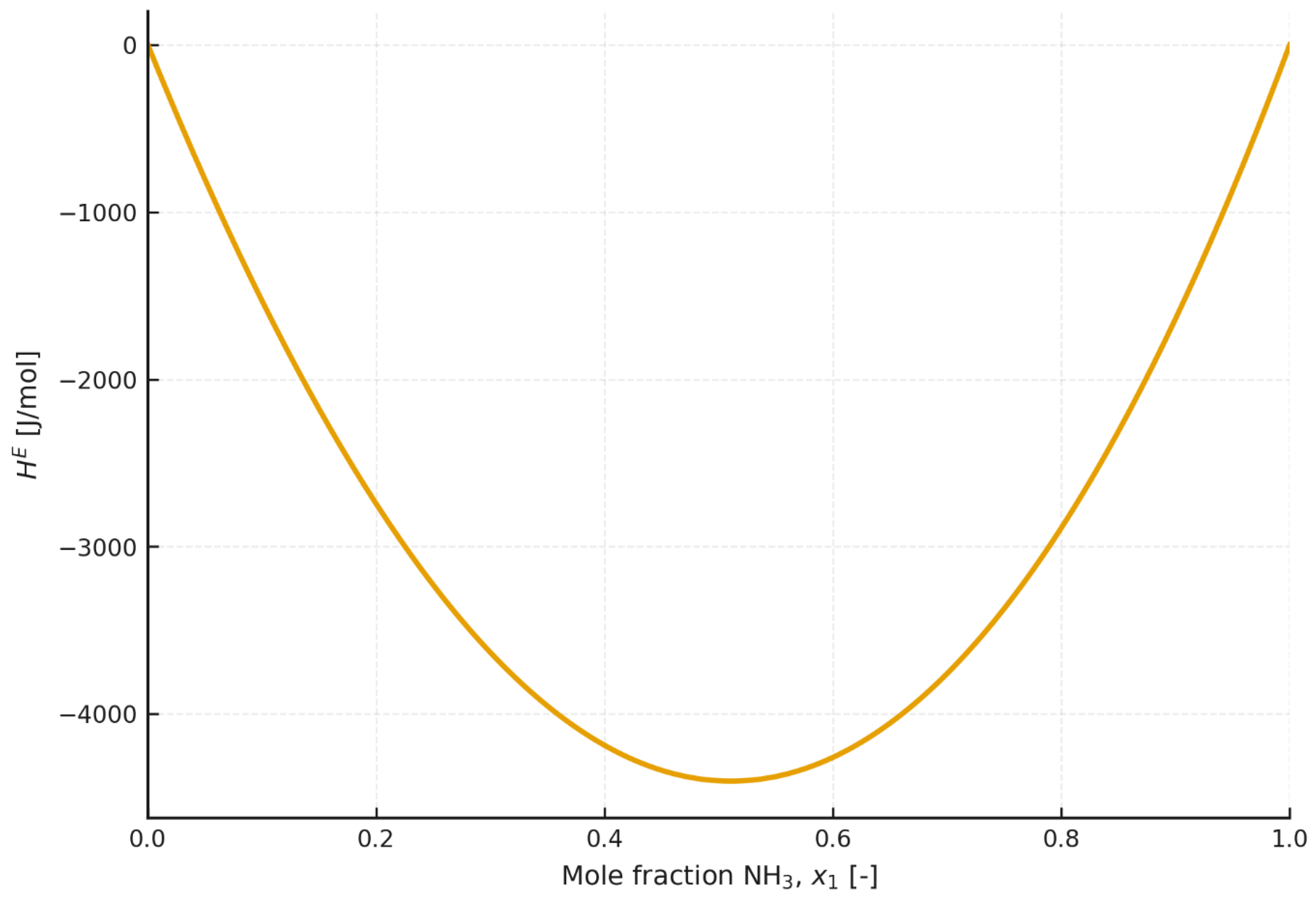

According to

Figure 7, it can be inferred that, for the [emim][SCN]–ammonia mixture at 403.15 K, the excess enthalpy is negative for every ammonia mole fraction. For 303.15 K, in accordance with

Figure 8, the excess enthalpy for the ammonia–[emim][SCN] mixture is negative up to an ammonia mole fraction of approximately 0.5. Above this value, the excess enthalpy becomes positive, which indicates an endothermic process and, at the same time, points to a significant reduction in the suitability of such a working-fluid composition for use in an absorption heat pump.

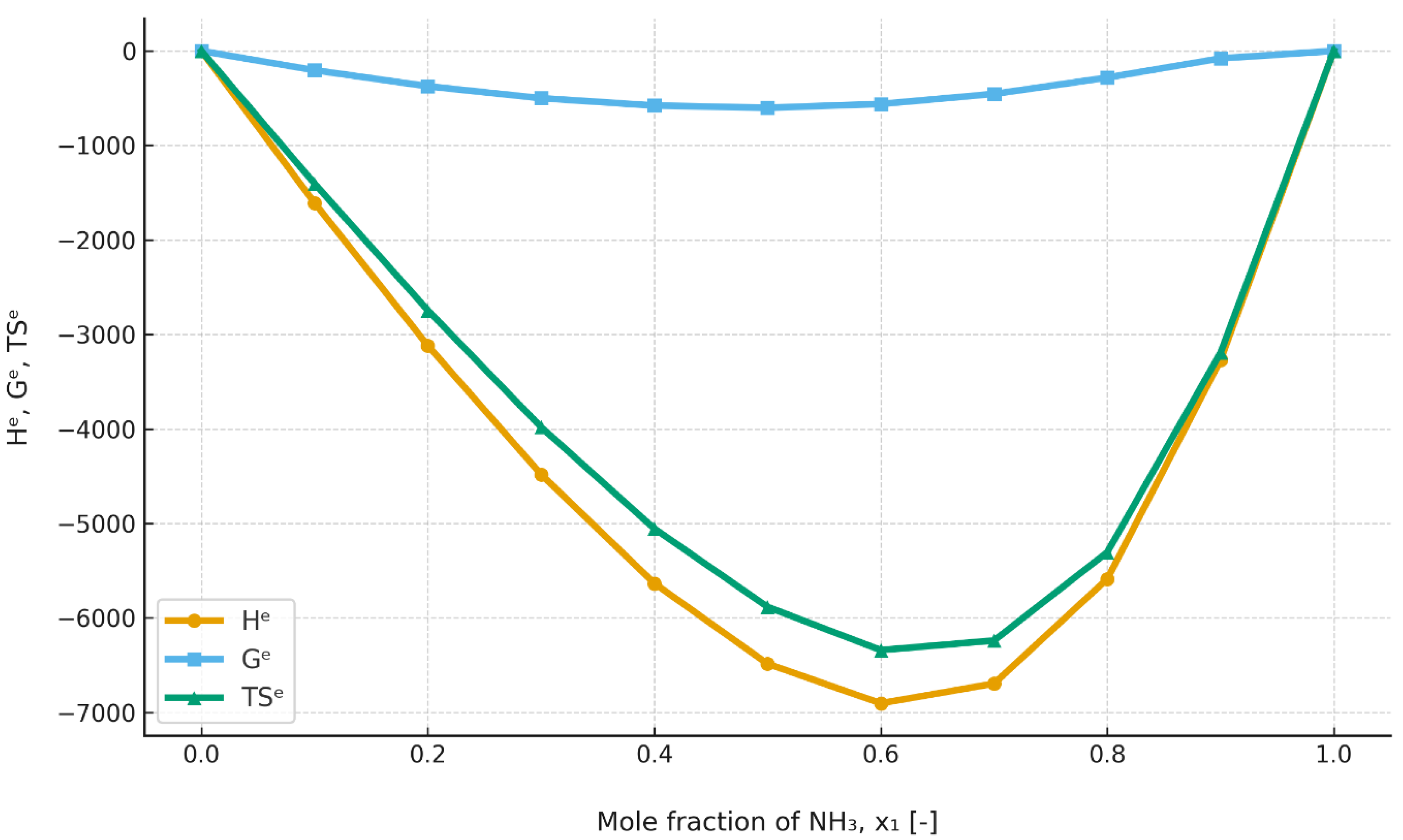

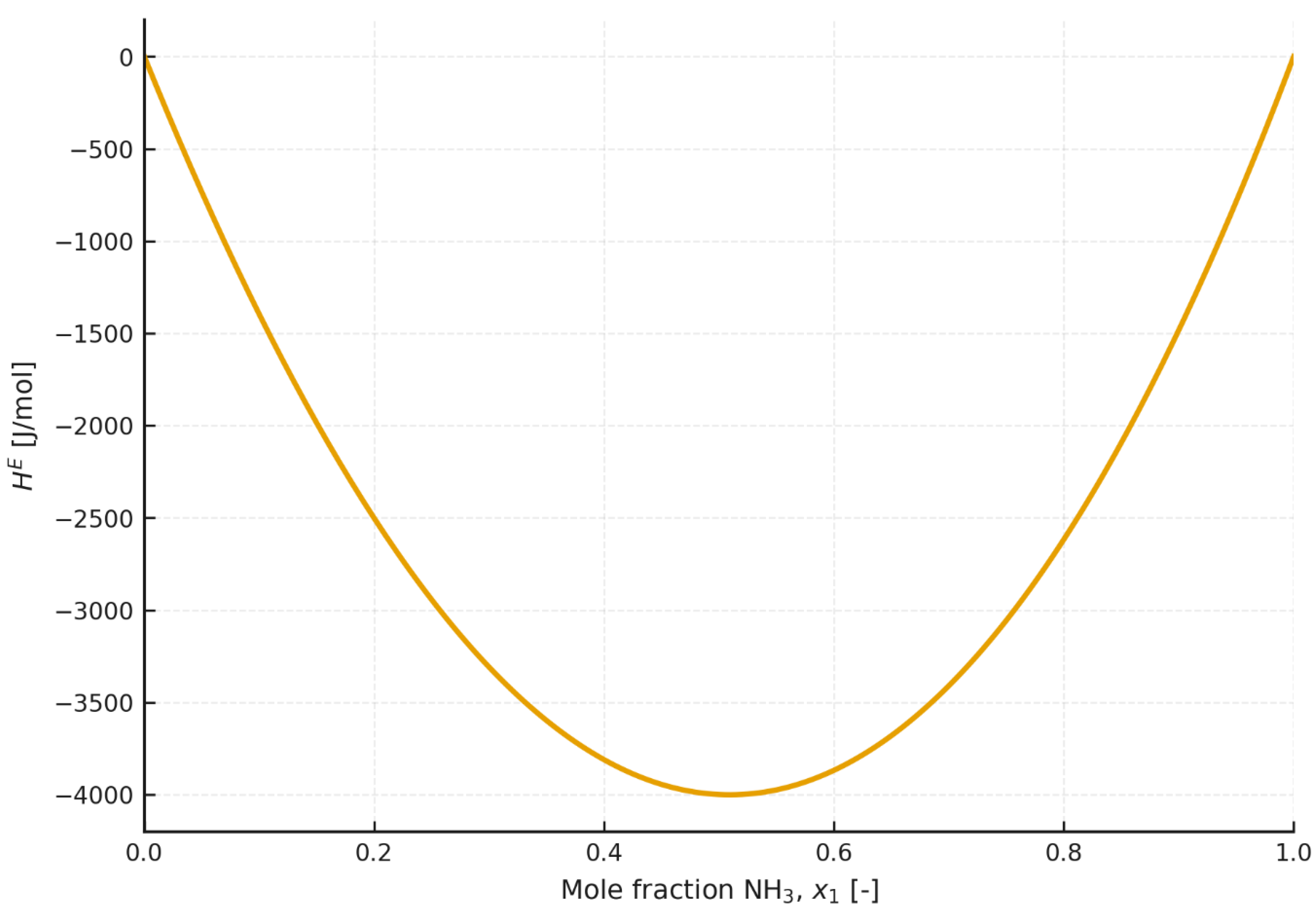

For the ammonia–ionic-liquid [emim][EtSO

4] mixture, the excess enthalpy values at 403.15 K, shown in

Figure 9, are significantly negative over the entire range and are, at the same time, decidedly more negative than in the case of [emim][SCN]. At 303.15 K, which indicated in

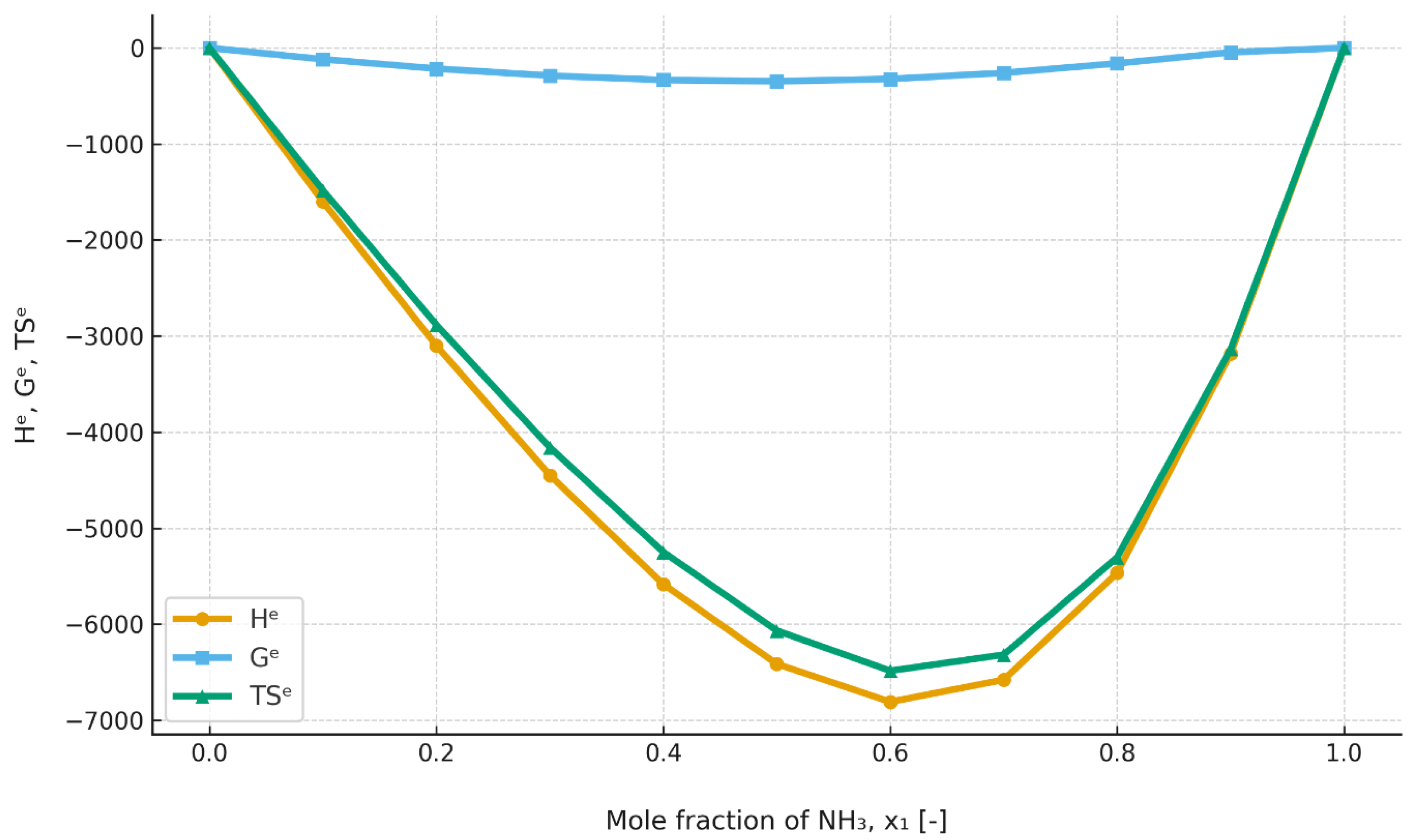

Figure 10, the excess enthalpy increases slightly; however, it retains the same characteristic behavior.

The excess enthalpy results indicate that the mixing process of ammonia and ionic liquids should, in principle, be exothermic over all or part of the concentration range. In addition, it should be noted that the excess enthalpy exhibits different temperature dependence for different mixtures. For [emim][SCN], the excess enthalpy decreases markedly with increasing temperature, whereas for mixtures based on [emim][EtSO4], it increases only slightly with increasing temperature. Considering that mixing of the components in an absorption heat pump takes place in the absorber, it may be assumed that, when high heating-water temperatures are considered, the excess enthalpy will be negative for every composition and system.

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 have been added for comparison, providing data on the excess enthalpies of the ammonia/water mixture.