The Impact of Input Data on the Building Energy Performance Gap: A Case Study of Heating a Single-Family Building in Polish Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Energy Performance of the Building

1.2. Building Energy Demand Models

1.3. Performance Gap

1.4. Input Data

1.5. Research Gap

1.6. Novelty and Aim of the Paper

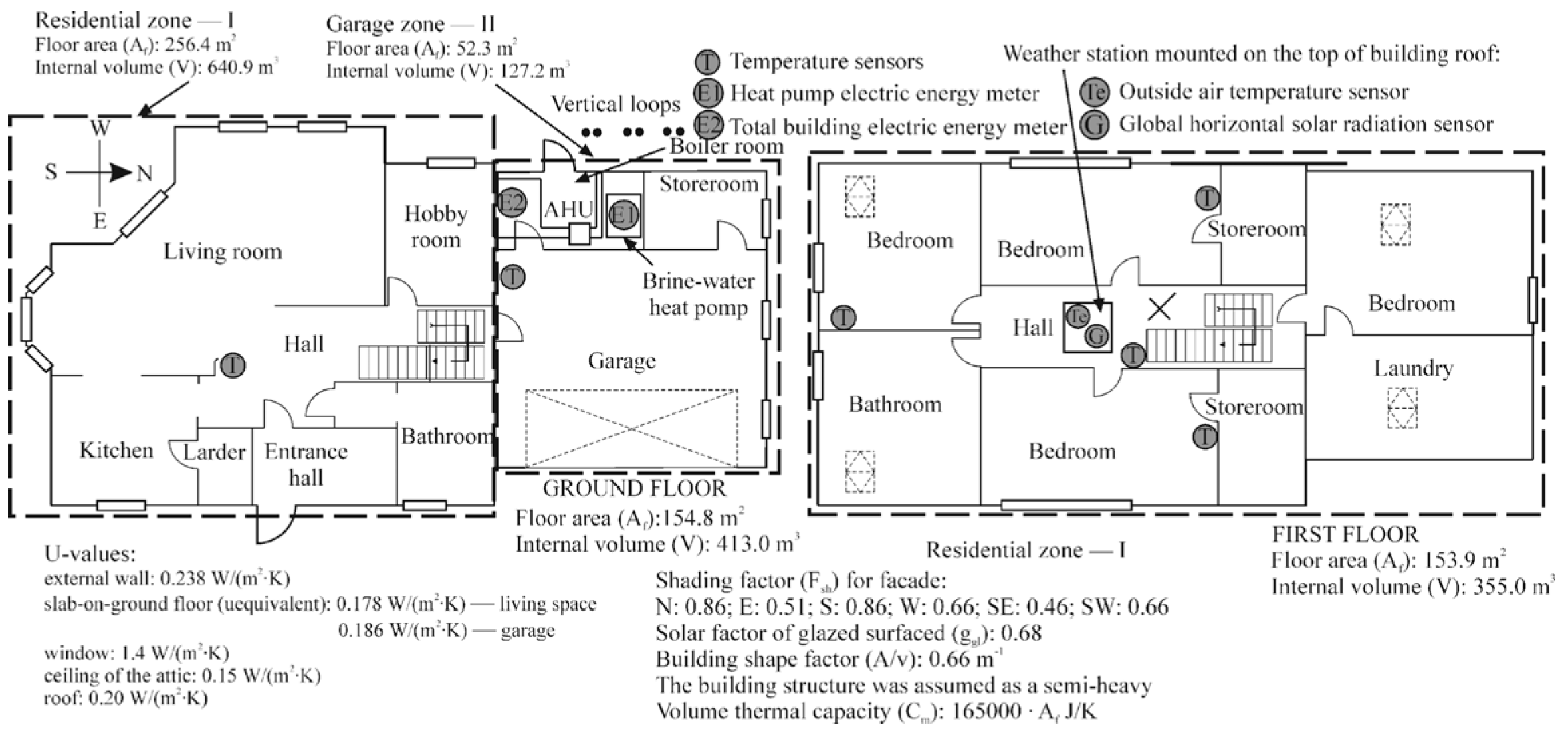

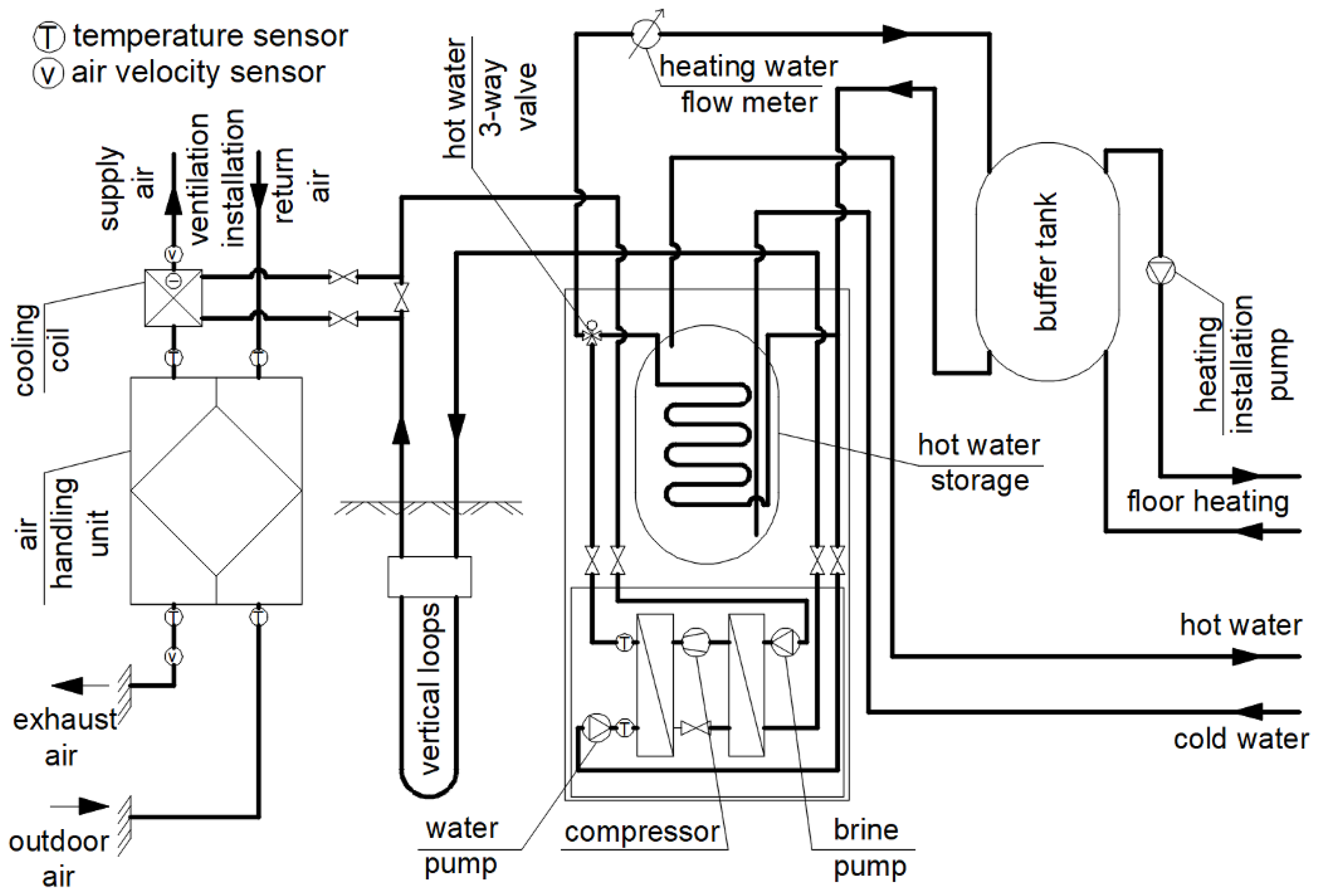

2. Analyzed Building

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Computational Model

- The monthly method of the quasi-steady state, (subscript “m”);

- The dynamic simple hourly method (subscript “h”).

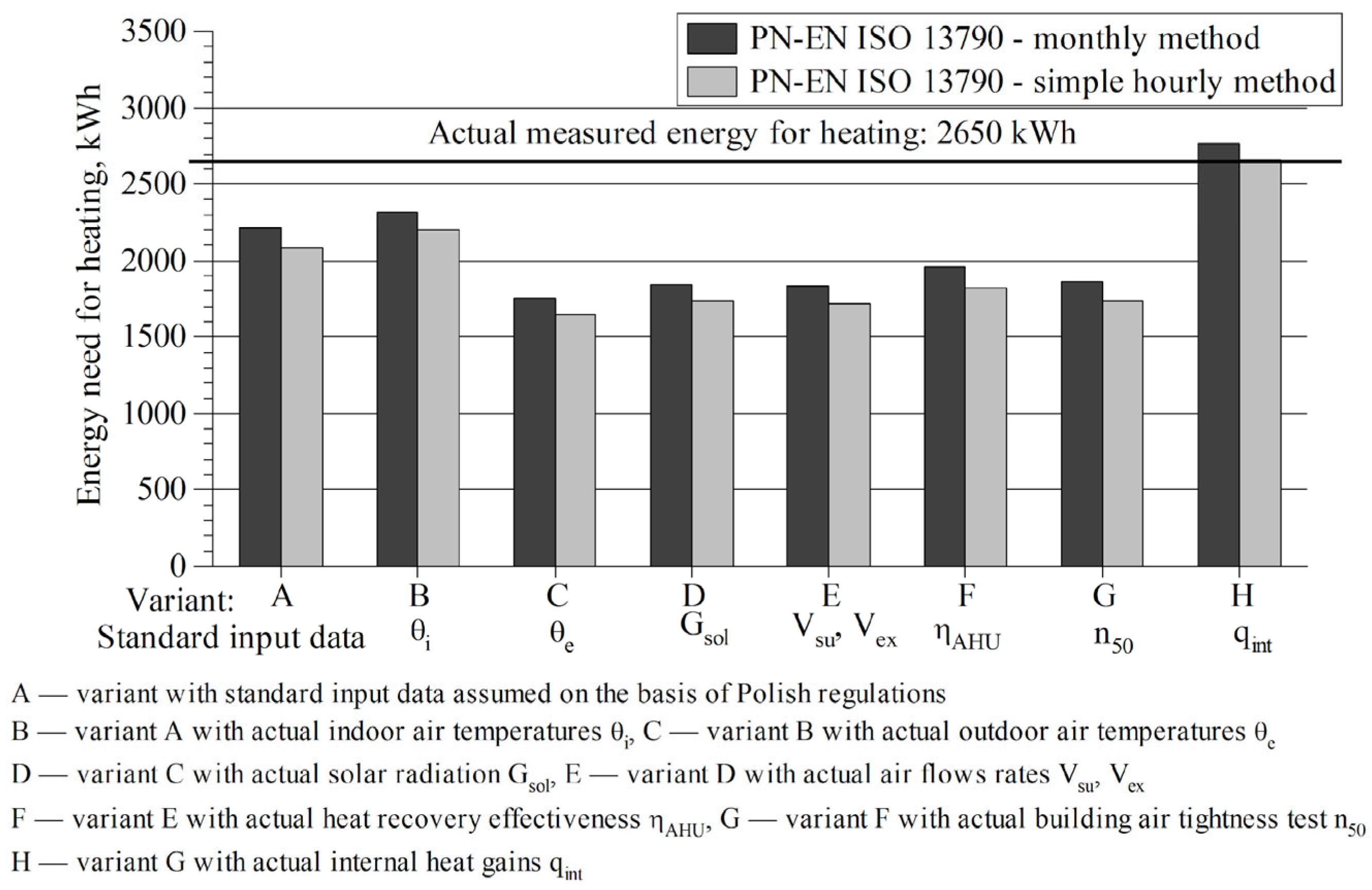

- A—variant with standard input data assumed on the basis of Polish regulations;

- B—variant A, with actual indoor air temperatures;

- C—variant B, with actual outdoor air temperatures;

- D—variant C, with actual solar radiation Gsol;

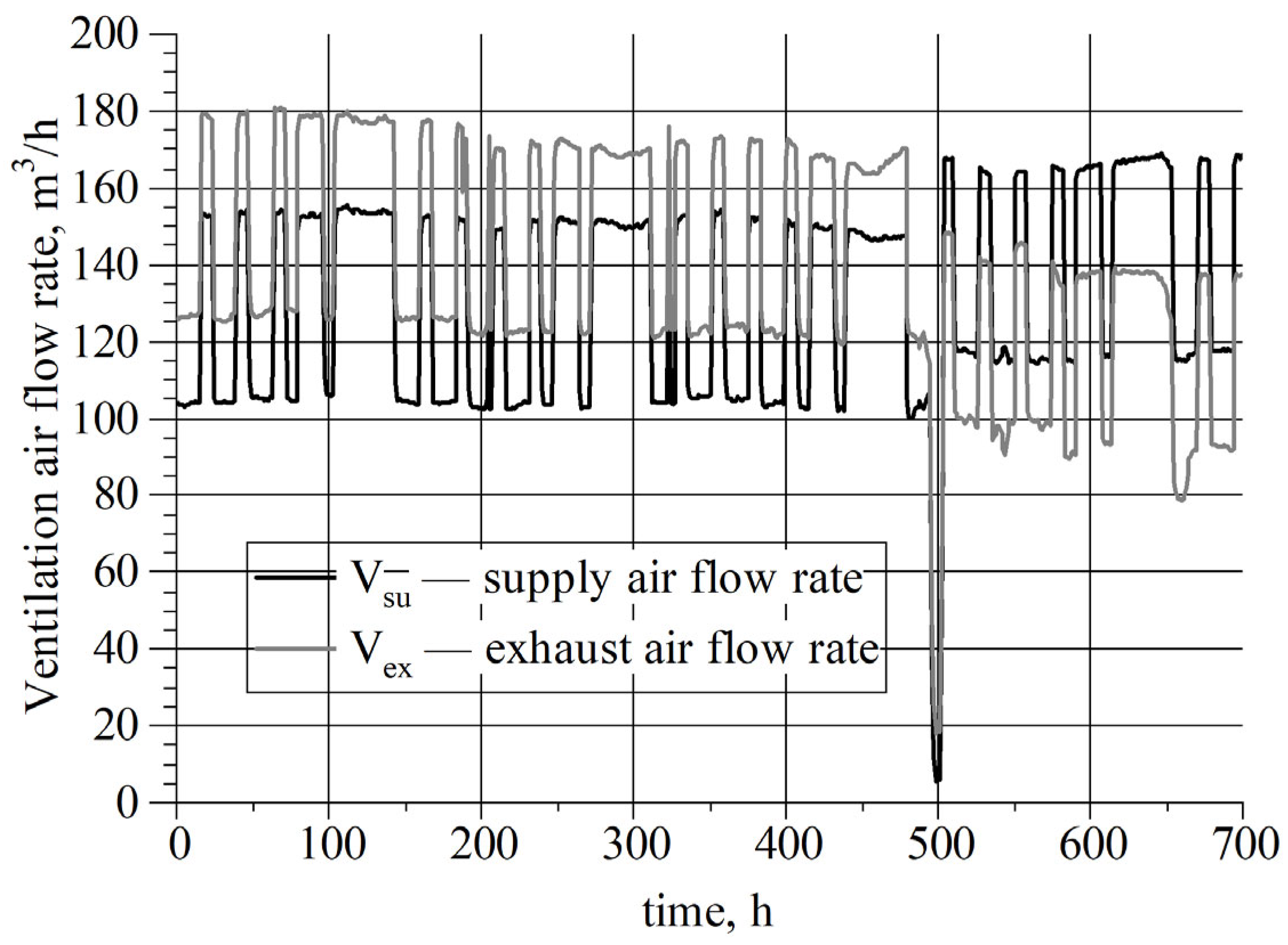

- E—variant D, with actual air flow rates Vsu, Vex;

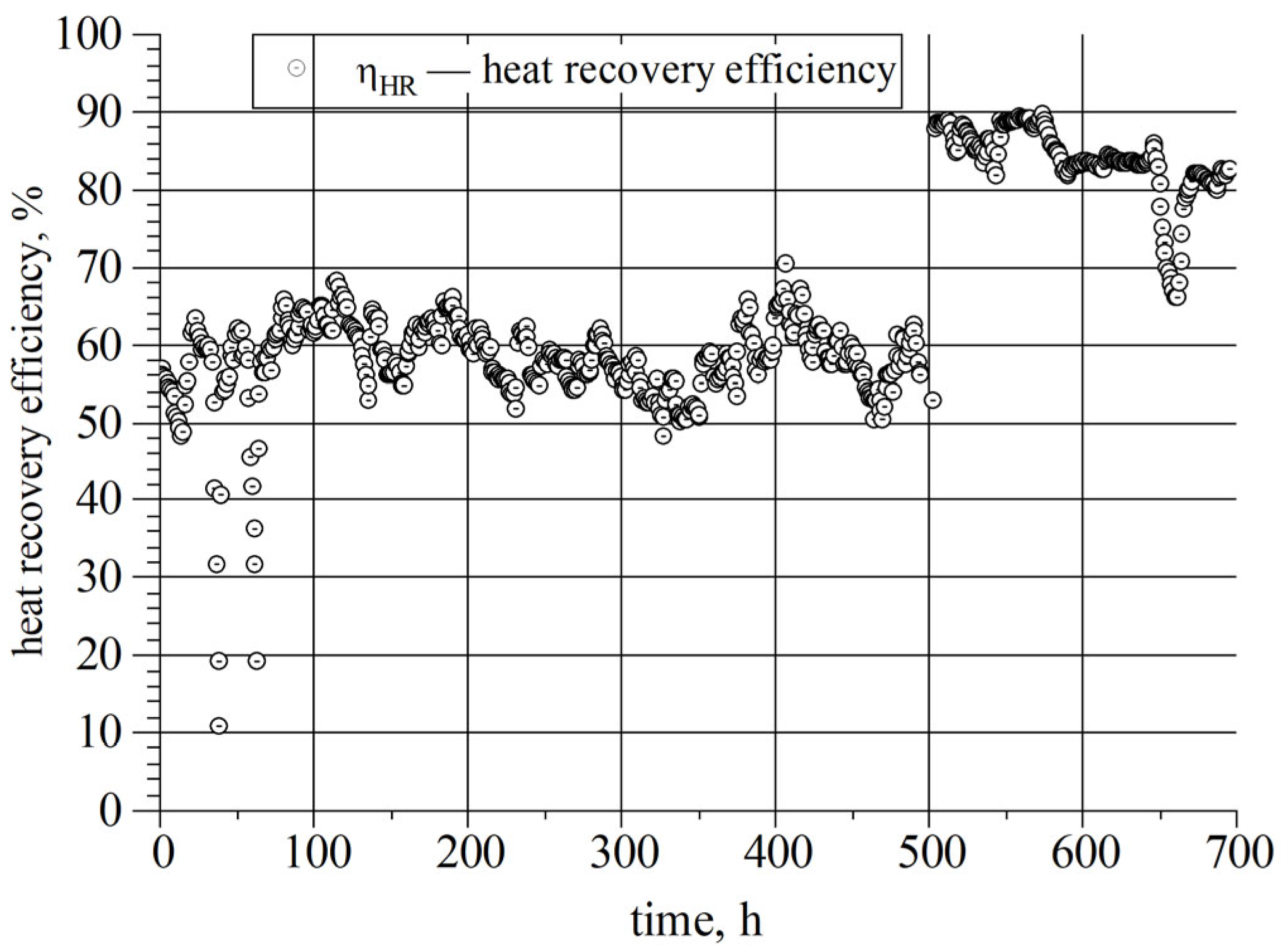

- F—variant E, with actual effective heat recovery rate ηHR;

- G—variant F, with actual building air tightness test n50;

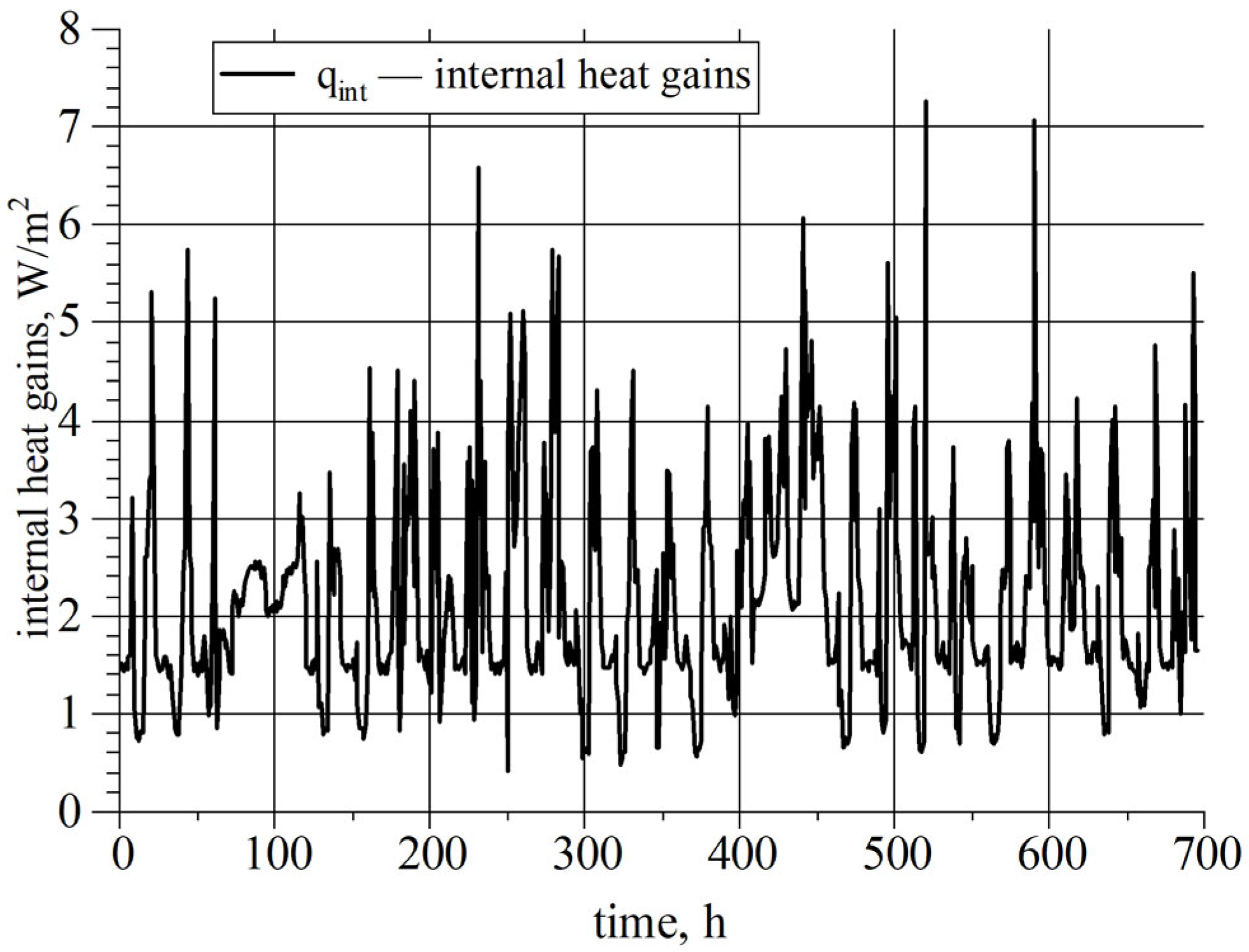

- H—variant G, with actual internal heat gains qint.

3.2. Method of Determining Input Data for Models

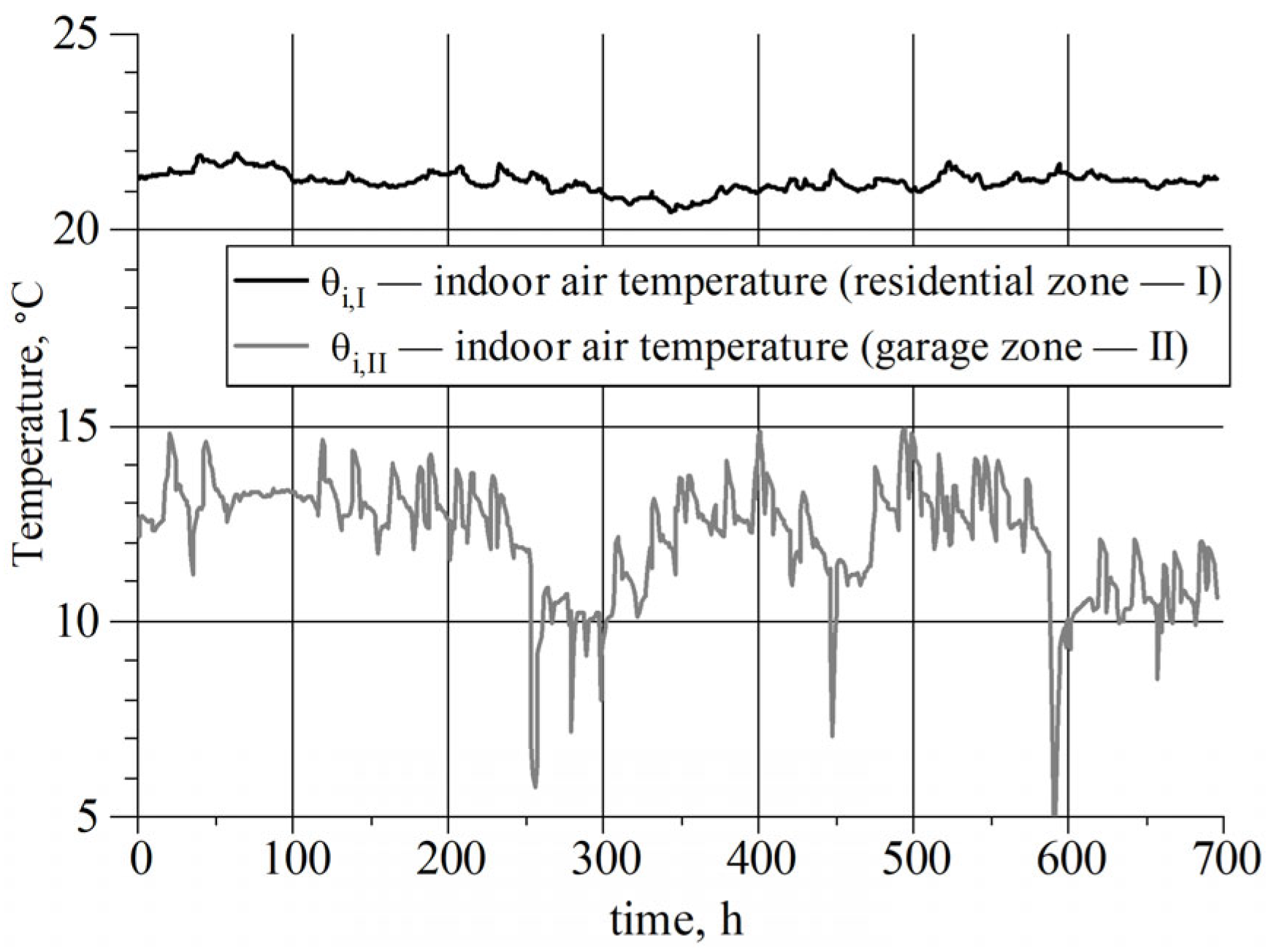

3.2.1. Indoor Air Temperatures

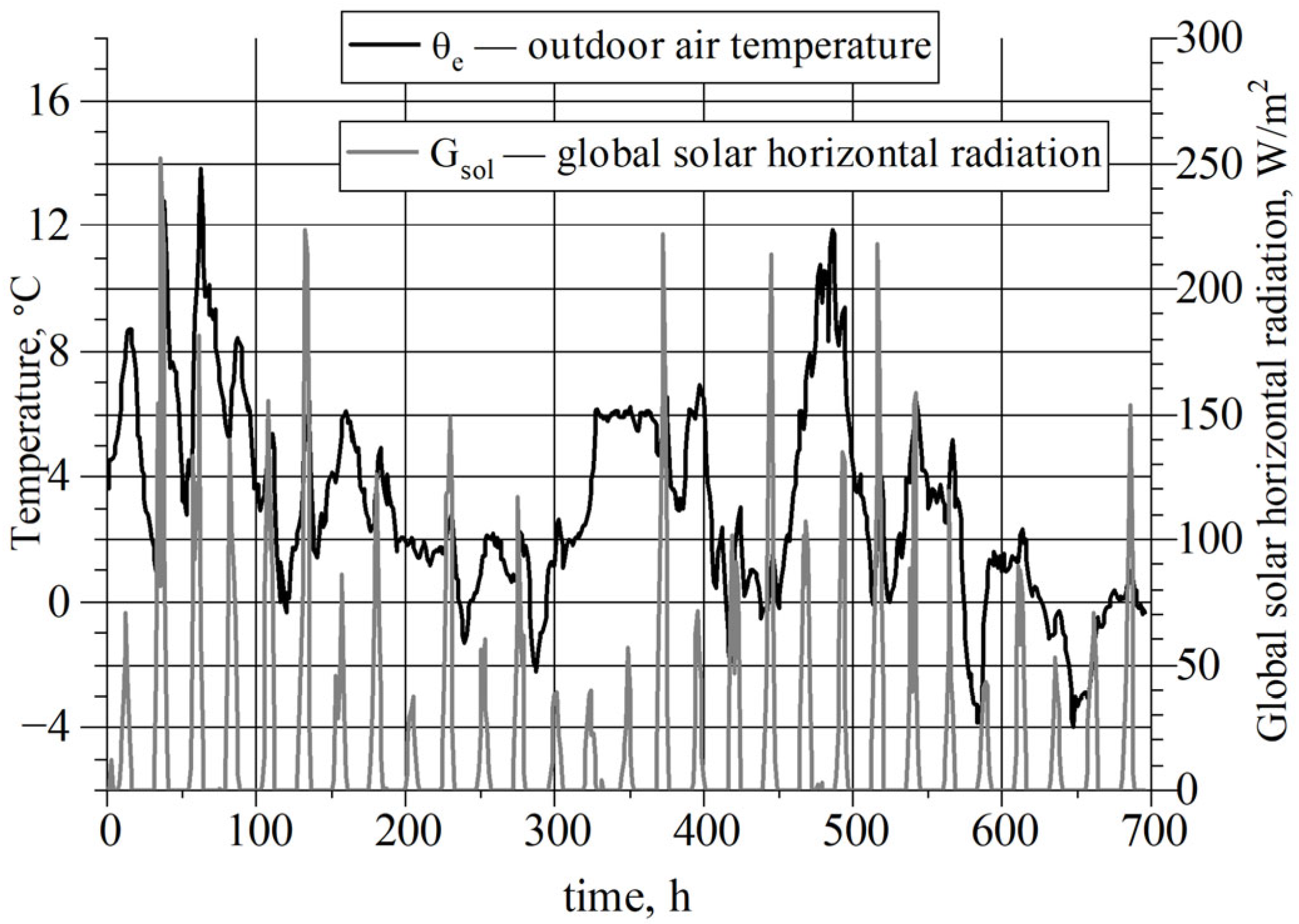

3.2.2. External Parameters

3.2.3. Ventilation Air Flow Rates and Heat Recovery Efficiency

- VSUP—outdoor air flow, m3/h;

- VEXT—extract air flow, m3/h;

- tODA—outdoor air temperature, °C;

- tEXT—extract air temperature, °C;

- tSUP—supply air temperature, °C.

3.2.4. Air Tightness of the Building Envelope

3.2.5. Internal Heat Gains

- The electric energy consumption of the heat pump and the heating installation pump (logged in 10 min intervals) was measured via the high-resolution data technique;

- The electric energy consumption of the fans in the air handling unit was determined based on an instant measurement (made by a BM357s wattmeter (Brymen Technology Corporation, Taiwan)) and the application of the intrusive testing technique;

- The electric energy consumption measured by an electric energy meter for the whole house (logged in 10 min intervals) was measured via the high-resolution data technique;

- The sum of the above-mentioned results was subtracted from the electric energy consumption measured by an electric energy meter for the whole house;

- The obtained difference was reduced by 30% [31] (fE = 0.7 was assumed; see Equation (2)) in order to take into account that not all electric energy is transformed into heat within the air-conditioned zone of the building (e.g., heater of the washing machine, dishwasher), based on the detailed audit and expert knowledge technique;

- The number of occupants was noted throughout the analysis period based on interviews, a high-resolution data technique;

- Metabolic heat gains from people were determined based on the above schedule of occupancy and assumed activity, relying on the expert knowledge technique;

- The above values were summed for every hour of the analyzed period:

- nap—number of adult occupants, person;

- nch—number of children occupants, person;

- qap—the average heat gain per adult person, W/person (assumed to be 77.8 W/person [45]);

- qch—the average heat gain per child, W/person (assumed 34.5 W/person [45]);

- QE—measured electricity use per reference floor area, W;

- fE—the share of total electrical energy consumption in the building, i.e., the portion of electrical energy used that is converted into heat within the air-conditioned space.

3.2.6. Analyzed Variants

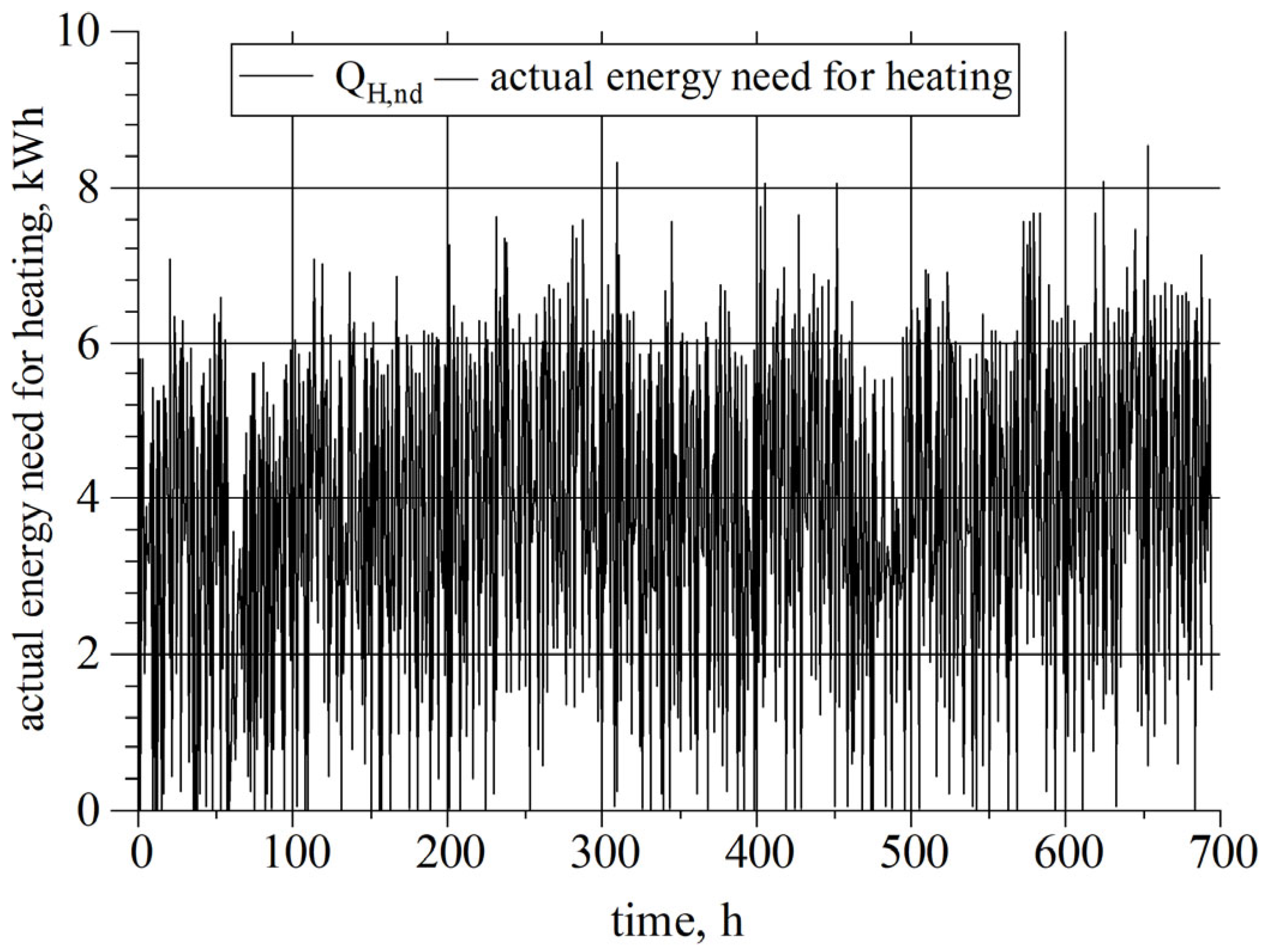

3.3. Actual Energy Needed for Heating

- Vfm—measured volumetric flow of the heating water, dm3/s;

- w—density of the heating water at the flow meter, kg/dm3;

- cw—specific heat of the heating water, kJ/(kg·K);

- tsw—measured temperature of the supply heating water, °C;

- trw—measured temperature of the return heating water, °C;

- H,d—distribution heat loss (calculated based on length and diameter of the pipes—unit losses from installations with pipe length 25 m: 2.6 W/m [25]), kWh;

- H,s—storage heat loss (calculated based on storage heat loss due to manufacturer data for the buffer tank, 60 W), kWh.

- Supply and return temperatures of heating water measured using own heat pump temperature sensors;

- The water pump, the brine pump, the heating installation pump, the compressor, and the 3-way hot water valve operation status.

3.4. Characteristics of Measuring Equipment

3.5. Calibration Performance Assessment

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Sensitivity Results for Internal Heat Gains

4.2. Validation

5. Policy Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commision. The European Green Deal; Routledge: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulgowska-Zgrzywa, M.; Stefanowicz, E.; Chmielewska, A.; Piechurski, K. Detailed Analysis of the Causes of the Energy Performance Gap Using the Example of Apartments in Historical Buildings in Wroclaw (Poland). Energies 2023, 16, 1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, P.; Szałański, P. Computational and the real energy performance of a single-family residential building in Poland—An attempt to compare: A case study. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2017; Volume 17, p. 00045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wilde, P. The gap between predicted and measured energy performance of buildings: A framework for investigation. Autom. Constr. 2014, 41, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, D.; Raftery, P.; Keane, M. A review of methods to match building energy simulation models to measured data. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 37, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Piazzini, O.; Scarpa, M. Building energy model calibration: A review of the state of the art in approaches, methods, and tools. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, P.; Szałański, P. Airtightness test of single-family building and calculation result of the energy need for heating in Polish conditions. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2018; Volume 44, p. 00078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, P.; Szałański, P.; Cepiński, W. Waste heat recovery by air-to-water heat pump from exhausted ventilating air for heating of multi-family residential buildings. Energies 2021, 14, 7985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepinski, W.; Kowalski, P.; Szałański, P. Waste Heat Recovery by Electric Heat Pump from Exhausted Ventilating Air for Domestic Hot Water in Multi-Family Residential Buildings. Rocz. Ochr. Srodowiska 2020, 22, 940–958. [Google Scholar]

- Cepiński, W.; Szałański, P. Increasing the efficiency of split type air conditioners/heat pumps by using ventilating exhaust air. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2019; Volume 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanowicz, Ł.; Ratajczak, K.; Dudkiewicz, E. Recent Advancements in Ventilation Systems Used to Decrease Energy Consumption in Buildings—Literature Review. Energies 2023, 16, 1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2002/91/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2002 on the Energy Performance of Buildings. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2002/91/oj/eng (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Directive 2024/1275 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 April 2024 on the Energy Performance of Buildings. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1275/oj/eng (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Statistics Poland. Energy Consumption in Households in 2021; Statistics Poland: Warszawa, Poland, 2024. (In Polish)

- Norford, L.K.; Socolow, R.H.; Hsieh, E.S.; Spadaro, G.V. Two-to-one discrepancy between measured and predicted performance of a ‘low-energy’ office building: Insights from a reconciliation based on the DOE-2 model. Energy Build. 1994, 21, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordass, B.; Cohen, R.; Standeven, M.; Leaman, A. Assessing building performance in use 3: Energy performance of the Probe buildings. Build. Res. Inf. 2001, 29, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zero Carbon Hub. A Review of the Modelling Tools and Assumptions: Topic 4, Closing the Gap Between Designed and Built Performance; Zero Carbon Hub: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stoppel, C.M.; Leite, F. Evaluating building energy model performance of LEED buildings: Identifying potential sources of error through aggregate analysis. Energy Build. 2013, 65, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, K.; Bandurski, K.; Amanowicz, Ł.; Brzeziński, J. Rozbieżności między obliczeniowym i zmierzonym zużyciem energii do ogrzewania i przygotowania ciepłej wody użytkowej na przykładzie budynków jednorodzinnych. Ciep. Ogrzew. Went. 2022, 53, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menezes, A.C.; Cripps, A.; Bouchlaghem, D.; Buswell, R. Predicted vs. actual energy performance of non-domestic buildings: Using post-occupancy evaluation data to reduce the performance gap. Appl. Energy 2012, 97, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, E.; Wouters, P.; Panek, A. Concerted Action: Supporting Transposition and Implementation of the Directive 2002/91/EC CA EPBD (2005–2007), Intelligent Energy Europe, Brussels. 2008. Available online: https://immobilierdurable.eu/images/2128_uploads/CA_Book_Implementing_the_EPBD_Featuring_Country_Reports_____.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Regulation of the Minister of Infrastructure of November 6, 2008 on the Methodology for Calculating the Energy Performance of Building and Dwelling or Part of Building, and Method of Preparing and Templates for Energy Performance Certificates. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20082011240 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- The Act of August 27, 2009, on Amending the Construction Law Act and the Real Estate Management Act. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20091611279 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Regulation of the Minister of Infrastructure and Development of the 27th of February 2015 on the Methodology for Determining the Energy Performance of a Building or Part of a Building and Energy Performance Certificates. (In Polish). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20150000376 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- De Wit, S.; Augenbroe, G. Analysis of uncertainty in building design evaluations and its implications. Energy Build. 2002, 34, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.X.; Magoulès, F. A review on the prediction of building energy consumption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 3586–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanhudo, L.; Ramos, N.M.M.; Poças Martins, J.; Almeida, R.M.S.F.; Barreira, E.; Simões, M.L.; Cardoso, V. Building information modeling for energy retrofitting—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 89, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. Procedures for Commercial Building Energy Audits, 2nd ed.; American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Draft (17 September 2025) Regulation of the Minister of Development and Technology on the Methodology for Determining the Energy Performance of a Building or Part of a Building and Energy Performance Certificates. (In Polish). Available online: https://legislacja.rcl.gov.pl/projekt/12386852 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- EN ISO 13790:2008; Energy Performance of Buildings—Calculation of Energy Use for Space Heating and Cooling. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- PN-EN 12831:2004; Heating Systems in Buildings—Method for Calculation of the Design Heat Load. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- PN-EN ISO 6946:2008; Building Components and Building Elements—Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance—Calculation Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. (In Polish)

- ISO 9869-1:2014; Thermal Insulation—Building Elements—In-Situ Measurement of Thermal Resistance and Thermal Transmittance—Part 1: Heat Flow Meter Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014.

- PN-EN ISO 14683:2007; Thermal Bridges in Building Construction—Linear Thermal Transmittance—Simplified Methods and Default Values. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. (In Polish)

- PN EN-ISO 10211; Thermal Bridges in Building Construction—Heat Flows and Surface Temperatures—Detailed Calculations. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- PN-EN ISO 13370:2007; Thermal Performance of Buildings—Heat Transfer via the Ground—Calculation Methods. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. (In Polish)

- PN-EN ISO 13789:2007; Thermal Performance of Buildings—Transmission and Ventilation Heat Transfer Coefficients—Calculation Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. (In Polish)

- Regulation of Minister of Infrastructure and Economic Development (12 April, 2002) on the Technical Conditions, Which Are to Be Met by Buildings and Their Location. (In Polish). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20020750690 (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Klein, S.A.; Beckman, W.A.; Mitchell, J.W.; Duffie, J.A.; Duffie, N.A.; Freeman, T.L.; Mitchell, J.C.; Braun, J.E.; Evans, B.L.; Kummer, J.P.; et al. TRNSYS 17: A Transient System Simulation Program; Solar Energy Laboratory, University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Minister of Infrastructure and Economic Development. Typical Statistical Climate Data for the Polish Area for Building Energy Performance Purposes. Available online: https://www.miir.gov.pl/strony/zadania/budownictwo/charakterystyka-energetyczna-budynkow/dane-do-obliczen-energetycznych-budynkow-1/ (accessed on 12 January 2019).

- PN-B-03430:1983; Ventilation in Residential, Common Living and Public Buildings—Requirements. Polish Commitee for Standardization: Warszawa, Poland, 1983. (In Polish)

- PN-EN 13829; Thermal Performance of Buildings—Determination of Air Permeability of Buildings—Fan Pressurization Method. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- PN ISO 9972; Determination of Air Permeability of Buildings—Fan Pressurization Method. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1999.

- Ahmed, K.; Kurnitski, J.; Olesen, B. Data for occupancy internal heat gain calculation in main building categories. Data Brief. 2017, 15, 1030–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgios, K.; Joe, C.; Paul, S. Impact of Using Different Models in Practice—A Case Study with the Simplified Method of ISO 13790 Standard and Detailed Modelling Programs. In Proceedings of the Building Simulation 2007: 10th Conference of IBPSA, Beijing, China, 27–30 July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kokogiannakis, G.; Strachan, P.; Clarke, J. Comparison of the simplified methods of the ISO 13790 standard and detailed modelling programs in a regulatory context. J. Build Perform. Simul. 2008, 1, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, S.; Zagarella, F.; Caputo, P.; Bonomolo, M. Internal heat loads profiles for buildings’ energy modelling: Comparison of different standards. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 89, 104306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huld, T.; Müller, R.; Gambardella, A. A new solar radiation database for estimating PV performance in Europe and Africa. Sol. Energy 2012, 86, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input Data/Variant | Method | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor temperatures (Section 3.2.1) | m | S: based on [39] 20.4 °C for zone I 8.1 °C for zone II | M: 21.2 °C for zone I; 12.1 °C for zone II | ||||||

| h | M: variable according to Figure 3 | ||||||||

| Outdoor temperatures (Section 3.2.2) | m | S: based on [41] −0.4 °C | M: 3.0 °C | ||||||

| h | M: variable according to Figure 4 | ||||||||

| Horizontal solar radiation (Section 3.2.2) | m | S: based on [41] 23.1 kWh/m2 | M/C: 14.1 kWh/m2—value adjusted to the angle and direction of solar radiation on windows | ||||||

| h | S: based on [41] | M/C: variable according to Figure 4—values adjusted to the angle and direction of solar radiation on windows | |||||||

| Ventilation supply and extract air flow (Section 3.2.3) | m | S: Vsu,I,ave = 195∙0.75 = 146 m3/h Vex,I,ave = 195∙0.75 = 146 m3/h Vsu,II,ave = 0 m3/h; Vex,II,ave = 20 m3/h | M: Vsu,I,ave = 131.3 m3/h and Vex,I,ave = 130.1 m3/h | ||||||

| h | M: variable according to Figure 5 | ||||||||

| Ventilation heat recovery effectiveness (Section 3.2.3) | m | S: 0.84 | M/C: 0.647 | ||||||

| h | M/C: variable according to Figure 6 | ||||||||

| Air tightness (Section 3.2.4) | m | S: n50 = 4.0 h−1 | M/C: n50 = 3.55 h−1 | ||||||

| h | |||||||||

| Heat gains (Section 3.2.5) | m | S: 6.8 W/m2 | M/C: Qint, I = 1.92 W/m2 for zone I; Qint, II = 2.39 W/m2 for zone II | ||||||

| h | M/C: variable according to Figure 7 | ||||||||

| Equipment | Parameter Range | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature logger LB-516AT (LAB-EL Elektronika Laboratoryjna sp. z o.o., Reguły, Poland) | −30.0 to 70.0 °C | ±0.2 °C for −10 to 40 °C |

| Thermohigrometer logger of type LB-516A (LAB-EL Elektronika Laboratoryjna sp. z o.o., Reguły, Poland) | −30.0 to 70.0 °C | ±0.2 °C for −10 to 40 °C |

| WatchDog 2000 weather station Spectrum (Spectrum Technologies, Inc., Aurora, IL, USA) | Temperature −20 to 70 °C | Temperature ±0.6 °C |

| Solar radiation 1 to 1250 W/m2 | Solar radiation ±5% | |

| Thermoanemometer probe 802A (LAB-EL Elektronika Laboratoryjna sp. z o.o., Reguły, Poland) | Temperature −30.0 to 70.0 °C | Temperature ±0.1 °C ± 1 last digit |

| Air velocity 0.1 to 50 m/s | Air velocity ±0.05 m/s ± 3% | |

| Temperature probe T-115a-4-100-1/3B-Pt100-R-100 (TERMO-PRECYZJA sp.j., Wrocław, Poland) | Up to 100 °C | 1/3B class |

| Retrotec blower door EU5101 (Retrotec, Everson, WA, USA) | 188 to 9670 m3/h | ±5% |

| Variant/ Method | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly method | CENH, kWh | 2209 | 2317 | 1757 | 1842 | 1837 | 1955 | 1865 | 2762 |

| ACENH, kWh | 2650 | ||||||||

| MBE, % | 16.6 | 12.6 | 33.7 | 30.5 | 30.7 | 26.2 | 29.6 | −2.7% | |

| Hourly method | CENH, kWh | 2086 | 2205 | 1649 | 1733 | 1717 | 1820 | 1733 | 2653 |

| ACENH, kWh | 2650 | ||||||||

| MBE, % | 21.3 | 16.8 | 37.8 | 34.6 | 35.2 | 31.3 | 34.6 | −0.1 | |

| Variant/ Method | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly method | CENH, kWh | 2039 | 2240 | 2538 | 2204 | 2145 | 2168 | 2228 | 3019 |

| ACENH, kWh | 3271 | ||||||||

| MBE, % | 37.7 | 31.5 | 22.4 | 32.6 | 34.4 | 33.7 | 31.9 | 7.7 | |

| Hourly method | CENH, kWh | 1929 | 2121 | 2424 | 2145 | 2093 | 2105 | 1986 | 3079 |

| ACENH, kWh | 3271 | ||||||||

| MBE, % | 41.0 | 35.2 | 25.9 | 34.4 | 36.0 | 35.7 | 39.3 | 5.9 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szałański, P.; Kowalski, P. The Impact of Input Data on the Building Energy Performance Gap: A Case Study of Heating a Single-Family Building in Polish Conditions. Energies 2025, 18, 6396. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246396

Szałański P, Kowalski P. The Impact of Input Data on the Building Energy Performance Gap: A Case Study of Heating a Single-Family Building in Polish Conditions. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6396. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246396

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzałański, Paweł, and Piotr Kowalski. 2025. "The Impact of Input Data on the Building Energy Performance Gap: A Case Study of Heating a Single-Family Building in Polish Conditions" Energies 18, no. 24: 6396. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246396

APA StyleSzałański, P., & Kowalski, P. (2025). The Impact of Input Data on the Building Energy Performance Gap: A Case Study of Heating a Single-Family Building in Polish Conditions. Energies, 18(24), 6396. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246396