Abstract

In this manuscript, an analysis of the prospect of using a direct-contact air, gravel, ground heat exchanger (GAHE)—patented and tested at the Wroclaw University of Science and Technology—as a simple and inexpensive way of improving microclimate parameters in horse stables using renewable energy was presented. Different options for introducing a GAHE into the typical HVAC system have been proposed and examined. Using the GAHE calculation model developed based on the research, computer simulations of the GAHE’s interaction with the ventilation system were conducted. The effects of GAHE interaction were compared with a typical solution that does not utilise ground renewable energy. The analyses demonstrate year-round changes in microclimate parameters, particularly in the air temperature, relative humidity, and the THI comfort index. The benefits of using a GAHE as a component that improves comfort for animals and employees, while simultaneously saving energy, were demonstrated. The use of measurement data and computer energy simulations demonstrates the engineering feasibility of including GAHEs in a mechanical ventilation system for a horse stable. The obtained results indicate the potential for improving animal husbandry and employee working conditions without the need to consume additional energy to operate complex HVAC systems.

1. Introduction

1.1. Reasons for Raising the Issue

Horses naturally prefer to be outside; however, for a variety of reasons, we more often keep them in a horse stable. A poor stable climate can cause health and welfare problems, one of the biggest being respiratory problems. These conditions can be difficult to treat, especially when they become chronic. A stable climate consists of several factors: temperature, humidity, ventilation, and light. According to Harewood and McGowan [1], housing conditions are also important, as horses generally spend most of the day in the stable [2,3]. Despite the positive aspects of keeping horses in stables, which include feed and water intake monitoring and protecting them from harmful insects and adverse weather conditions [4], the way that horses are kept in stables needs continuous improvement [5].

1.2. The Air Direct-Contact, Gravel, Ground Heat Exchanger (GAHE)

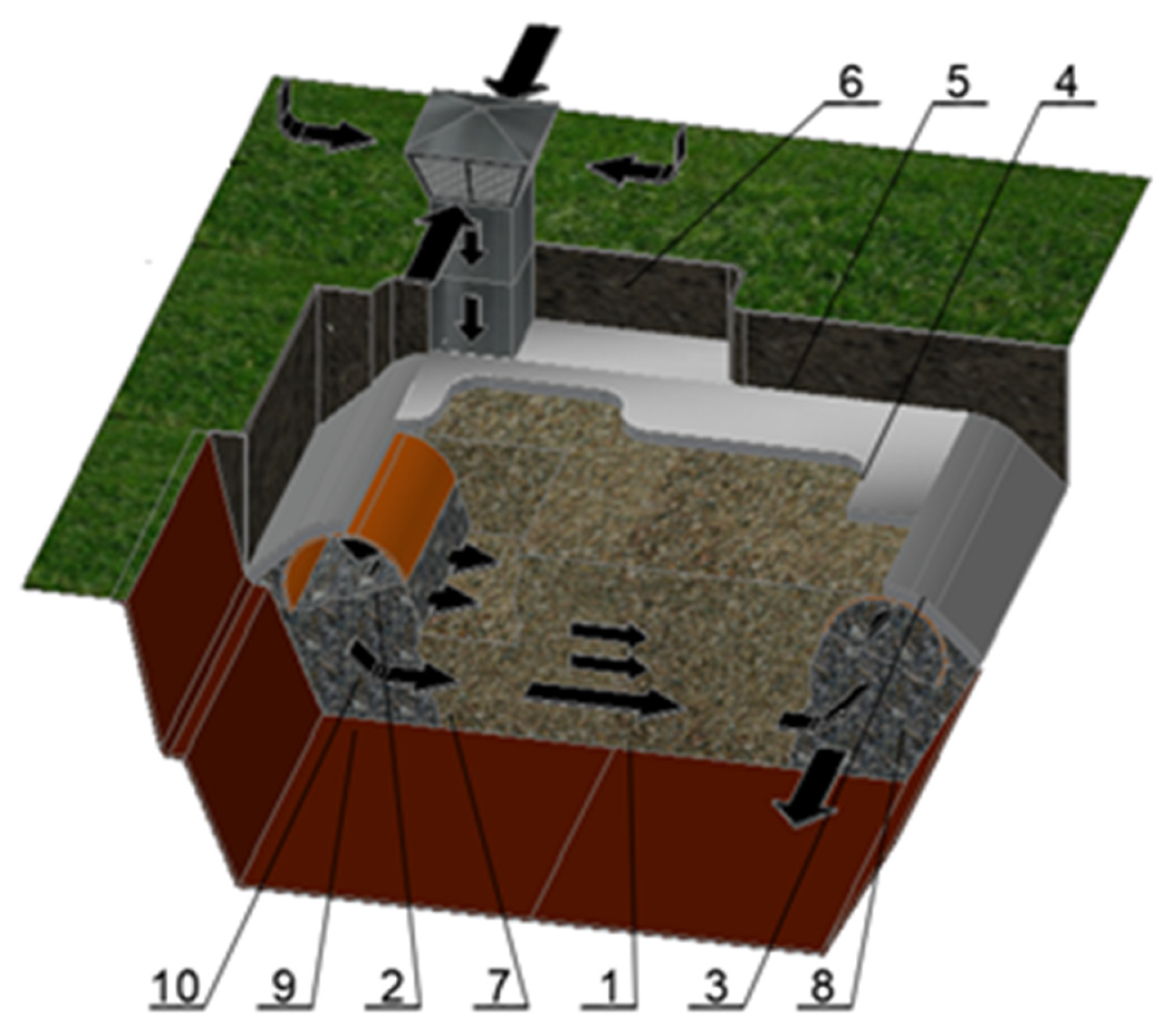

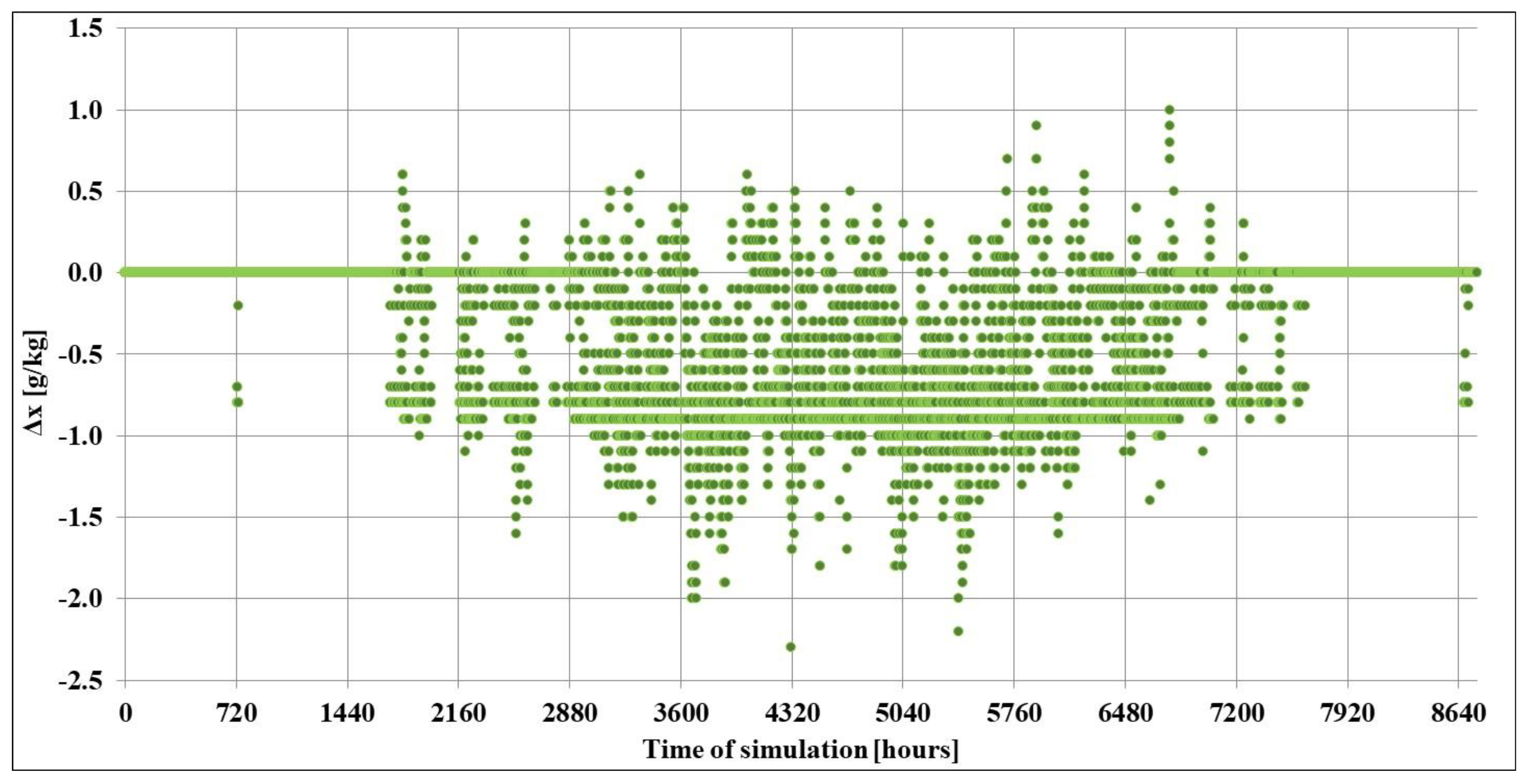

The Institute of Air Conditioning and District Heating at Wroclaw University of Science and Technology has been executing scientific work [6,7,8] over an extended period regarding the effective utilisation of thermal energy (both heating and cooling) drawn from the shallow, direct-contact, gravel GAHE systems (Figure 1), specifically targeting ventilation and air-conditioning systems.

Figure 1.

Proposal for exchanger construction: 1—gravel accumulation bed, 2—distribution duct, 3—collection duct, 4—thermal/humidity insulation, 5—exchanger cover, 6—air intake, 7—coarse-gravel distribution bed, 8—coarse-gravel collecting bed, 9—native soil, 10—geotextile [8]. The black arrows indicate the direction of air flow.

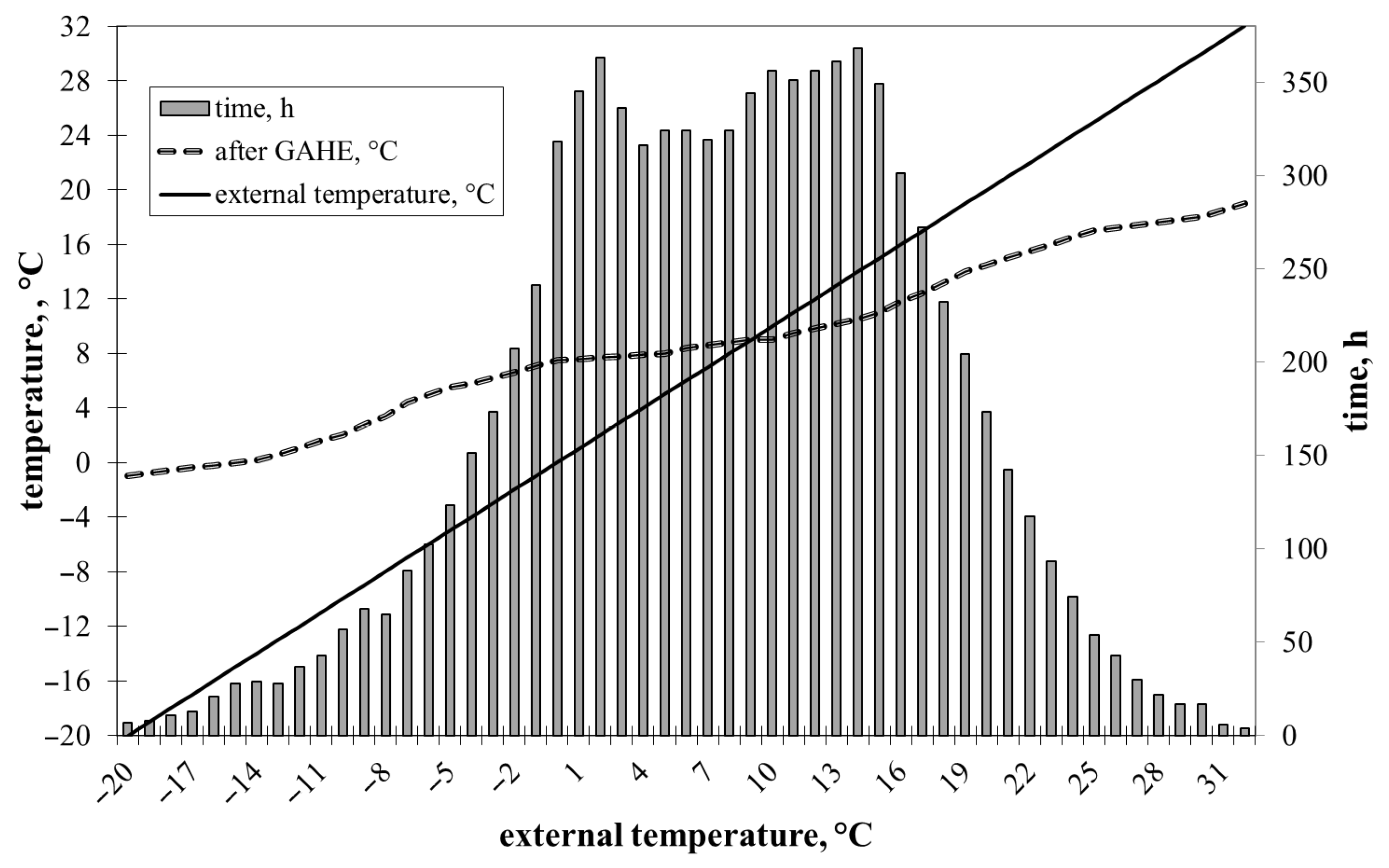

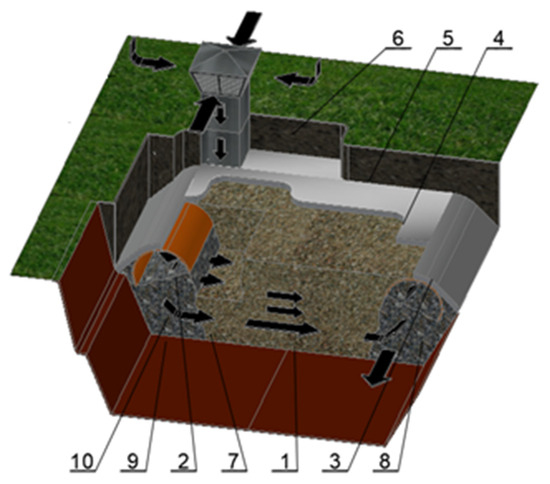

In the mid-European climate, the ground temperature at 4–5 m underground is almost constant throughout the year, and is close to the average annual outdoor temperature (around +10.0 (±1.5 °C)). GAHEs can be constructed by placing the heat-exchanging gravel bed of appropriate volume at a shallower depth. The effects of GAHE operation are shown in Figure 2, based on the results obtained in already operating exchangers (used for the needs of facilities other than horse stables). The construction of the analysed exchanger is not complicated, and the materials needed are easily accessible and relatively inexpensive to acquire. The entire structure should be insulated with a layer of polystyrene foam placed over the bed. Proposed construction can be installed almost anywhere within the limits of the property, or under the ground floor of the building itself. This type of GAHE construction is not recommended in soils or with fills that contain radon particles.

Figure 2.

Average air temperature values downstream of the ground exchanger (GAHE) superimposed on the yearly duration of corresponding outdoor temperatures [7,8].

The air in horse stables also contains a large number of inorganic and organic particles, which can be potential allergens and respiratory irritants. Organic particles are particularly irritating and often originate from feed, bedding, manure, or from coatings on horse stable walls [9,10]. Proper hygiene and a healthy microclimate have a significant impact on the health and well-being of horses.

Poor air quality in horse stables can be responsible for respiratory diseases in horses [11]. Respiratory diseases can occur as a result of accidents, but can also be caused by irritating or toxic gases or by inhaling dust suspended in the air [12].

Respiratory allergy is a common problem, commonly diagnosed as a condition affecting the lungs of horses. Long periods of this condition cause COPD, an animal model of asthma [13]. Poor air quality can also lead to appetite and thermoregulation problems [14,15].

Studies conducted in traditional horse stables have shown that permissible levels of pollution are often exceeded, which can cause respiratory tract inflammation in service staff as well [9,16,17]. However, until recently, the impact of air in horse stables on human health has been relatively neglected.

The use of properly functioning ventilation, ensuring adequate air exchange, reduces the number of pollutants absorbed by animals and staff [18,19].

Adequate air exchange is necessary to regulate horse stables’ inside air temperature, remove moisture, stable gases, and organic pollutants. In northern climates, there is no need to remove excess heat from horse stables during the winter season; however, greater emphasis is placed on the removal of moisture, odours, and ammonia that have accumulated in the enclosed stable environment. Horses have a low tolerance for high humidity [20]; it makes them more susceptible to respiratory diseases and, in older individuals, exacerbations of the symptoms of chronic rheumatic disease can occur [21,22].

The air—after passing through the GAHE—also contains far fewer cells of microorganisms than those contained in the outside air. Both the numbers of fungi and bacteria are significantly reduced [7,8]. This phenomenon was confirmed by measurements of airflow purity downstream of heat exchangers, operating for several seasons, conducted by the Polish Sanitary and Epidemiological Office. The results of the evaluation of air quality that leaves the GAHE after many years of operation are presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Results of the investigation of air purity in ground exchangers in Wrocław [7,8].

A ten-fold reduction in bacteria counts and a 70% reduction in fungal spores were observed in the supply air. Thus, the exchanger acts as a kind of effective air filter. Reducing the number of pathogens in the airflow supplied to the horse stable significantly reduces the risk of chronic respiratory diseases (POChP, RAO, dizziness, and persistent cough), among others [7,8,23].

A significant improvement in hygiene conditions and animal comfort can be achieved by using a solution that is cheaper and less prone to failures than typical air-conditioning systems.

1.3. The Conditions for Keeping Horses

Horse breeding plays a significant economic role in the agricultural economy. Horses living in the wild are exposed to the environment. In particular, access to food, climate heat and humidity conditions, and soil conditions are important.

Domesticated horses that remain in a human-designed microclimate, closer to the optimum than natural ones, are less hardened and have reduced resistance to disease.

In practice, a large number of horses raised are kept indoors for a considerable amount of time [3].

A distinction is made between two directions for keeping horses under artificial conditions [24,25,26,27,28].

According to Regulation [29], the minimum box area for adult horses should be 10 m2. Some researchers recommend slightly larger areas for recreational horses [26,28].

1.4. Required Air Parameters for Horse Stables

In stables, horses should be provided protection from adverse external conditions, while at the same time being provided suitable internal conditions in accordance with animal welfare requirements. The right microclimate is influenced by the indoor air temperature, its humidity, cleanliness, and supply of fresh air [30]. The microclimate conditions in a horse stable significantly affect animal welfare, health, comfort, growth, and longevity.

The increasing intensification of horse husbandry efficiency requires that the microclimate conditions in stables are kept as close as possible to optimal maintenance conditions [31].

Therefore, by avoiding diseases, the costs associated with horse breeding are reduced.

Factors that influence horse sensation can be divided into those related to horse behavioural needs, for example, allowing animals to come into contact with other horses (the architecture of the building) and also ensuring appropriate thermal and climatic conditions.

There is a need to look for solutions that can meaningfully improve the efficiency of breeding without a negative impact on the environment. In an era where traditional energy sources are becoming increasingly scarce due to significant fossil fuel consumption, it is increasingly important to find better solutions that utilise environmentally friendly energy, preferably energy that is available from the natural environment and readily accessible. GAHEs are a solution that could potentially meet these expectations.

Adult horses tolerate a relatively wide range of temperature variation. Minimum winter temperatures in the holding area should not fall below +5 (0) °C, and maximum temperatures in the stable should not exceed +28 °C. Horses can cope much better with lower temperatures than with too-high temperatures. This is possible, among other things, because of specific physiological reactions [2].

A few hours’ drop in air temperature in the stable, slightly below 0 °C, is not usually, for unshorn horses, a serious problem. Constant exposure to low temperatures and draughts (horses in stalls close to the gate) is certainly detrimental.

The optimal range of air temperature in the stable for horse rearing (TNZ—thermoneutral zone, Table 2) is between 8 (5) °C and 20 (25) °C [32], and when this is provided, horses consume the least energy necessary to maintain their physiological parameters and are not exposed to heat stress. Some discrepancies in the limit values are related to the ability of horses to acclimate to different microclimate conditions, depending on the external climatic conditions prevailing in the region. Within this temperature range, horses can easily eliminate excess heat generated by their bodies. Horses consume approximately 75% of their energy metabolism to improve blood circulation in order to produce heat, while the remaining 25% is spent on motion [33]. Most of the heat is lost by sweating and evaporation from the skin surface (65%); the rest is lost mainly through respiration (25%). At high temperatures, the main problem is the loss of water and electrolytes [34].

Table 2.

Recommended ranges of temperature and humidity for stables.

At higher (but also lower) temperatures, changes take place within the body. The body tries to adapt to the new undesirable situation. At temperatures higher than what is considered optimal, heat stress begins; it becomes more acute when the temperature increases and/or the relative humidity increases. Under heat stress, horses generate more body heat than they can dispose of.

Excessively high room temperatures usually prevail in stables that overheat in the heat of summer. Excess room heat gain can also be caused by poor, inefficient ventilation. In facilities with poor partition insulation and high heat penetration, and at the same time poor ventilation, excessive indoor air temperatures are maintained even throughout the night [37]. The use of air-conditioning in stables is useful but expensive, both in terms of the investment and operation.

The optimal indoor relative humidity for horses should not exceed 70% [Table 2] [36]. Some researchers consider an upper limit to be 80% relative humidity [2,38,39,40]. Excess humidity can lead to inflammatory skin diseases and accelerate the corrosion and the rotting of leather and wooden objects of equipment stored in the premises.

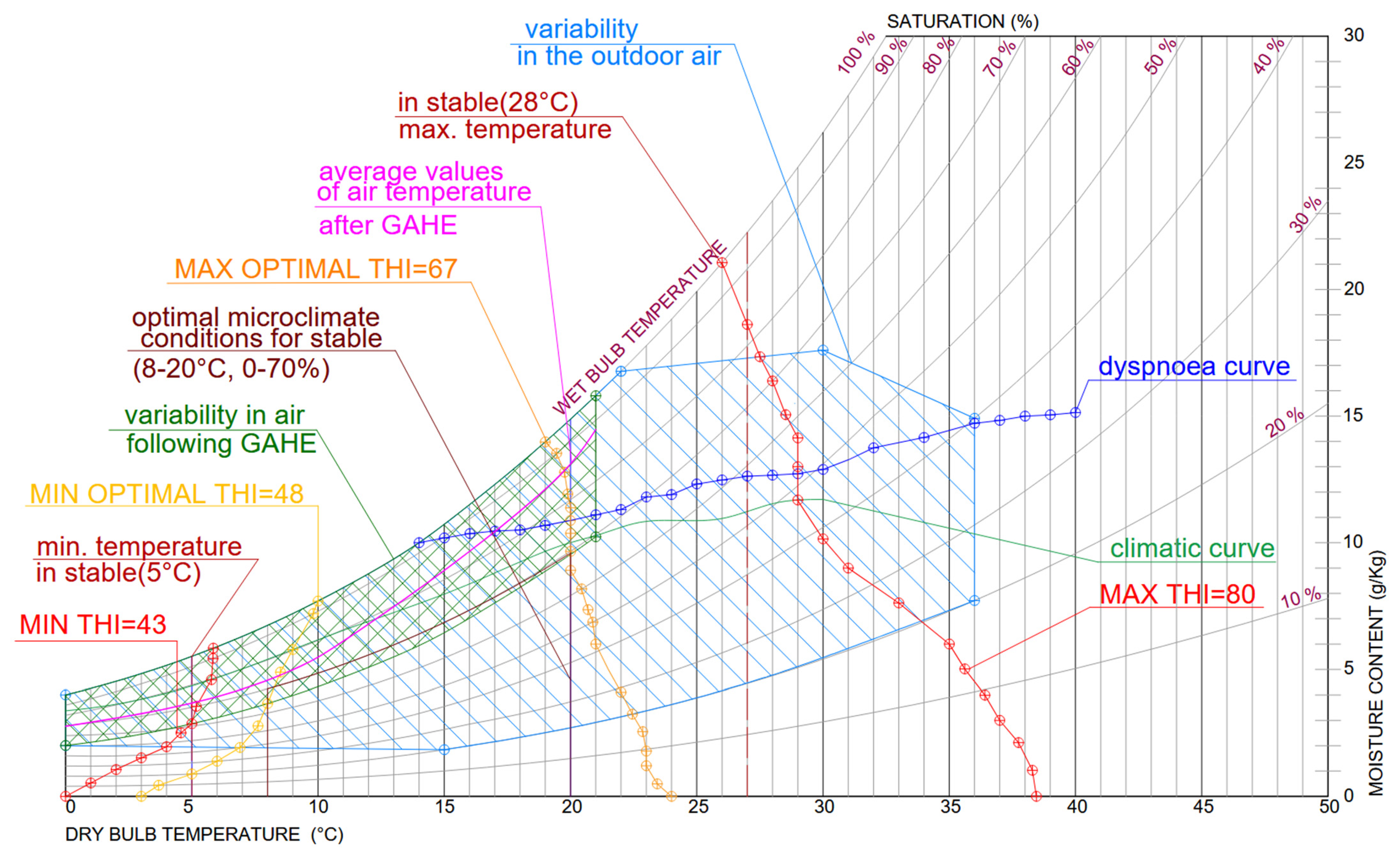

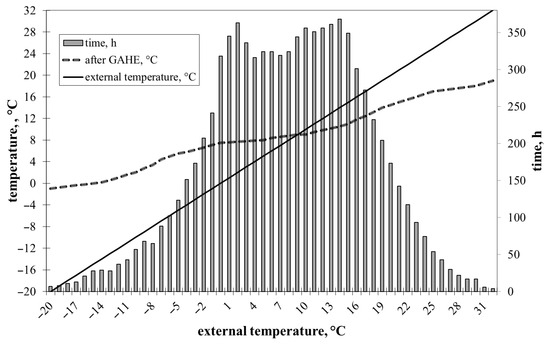

Horses do not tolerate excessive humidity, especially when combined with high indoor air temperatures. At a relative humidity of 80% and a temperature of up to +20 °C, the water vapour content reaches 12 g/m3 of dry air. This value is considered the limit to thermal comfort. The following graph (Figure 3) shows a line indicating the values of the stuffiness curve for different temperatures according to Lancaster–Curtens–Ruge [41].

Figure 3.

Ranges of air-parameter changes in the psychometric chart.

Excess humidity affects the well-being of horses and increases the risk of respiratory diseases [40]. It also causes faster degradation of the building. Moisture comes from breathing, sweat, and the evaporation of untreated faeces [42,43,44].

The outside and indoor air can contain various types of dangerous pollutants, such as bacteria, viruses, protozoa, fungi, moulds, and pollen, which cause allergies and asthma. In addition to biological pollutants, air can also contain chemical compounds and fractions of suspended particulate matter (PM) [45,46].

Any reduction in pollution is beneficial for the interior air quality in horse stables, especially in the context of protecting the respiratory health of horses. The specific operation of a GAHE, with its direct contact of the moistened bed with the supply air stream, significantly reduces the number of particles introduced through ventilation. The role of ventilation systems is to remove or dilute pollutants in the indoor air. Research shows that a balanced and effective mechanical ventilation system reduces the concentration of CO2, ammonia, ultrafine dust particles, and allergens [18]. Adequate ventilation also provides sufficient air to breathe, effectively removes moisture, heat, gaseous and dust pollutants, and prevents horses from draughts (Table 2) [24,38,39,47]. The speed of air passing over the horse’s body surface in the stable is also important [48,49].

In Figure 3, areas are presented that show the nature of the variability in the outdoor air and the air after using a GAHE, recorded in Poland. In addition, in this graphic, the so-called climatic curve is indicated, showing the average outdoor air parameters of the geographical area of Poland, and the typical thermal comfort parameters of the stables. The maximum allowable air parameters exceed this range, which means that these parameters should be analysed together.

1.5. Stress and Temperature–Humidity Comfort Conditions in Horse Stables

Horses often spend many hours a day in the confined spaces of stables; therefore, it is particularly important to take into account their natural needs and to provide them with conditions as close as possible to optimal living conditions [31]. In addition to indoor air cleanliness, proper levels of temperature and humidity are important.

Non-optimal air parameters negatively affect the health of horses, their physical and mental fitness and condition, lowering the welfare level [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57].

Horses show a much higher tolerance to cold than to heat. In temperate regions during summer, heat stress is a major concern for the welfare of farm animals.

Horses find it difficult to cope with conditions of excessive humidity. Excess humidity worsens their well-being and increases the risk of respiratory diseases [40]. High relative humidity prevents animals from releasing heat into the environment by evaporating from the body surface.

Heat stress is the sum of two factors: the animal’s metabolism and physical activity—which generate the amount of heat and moisture released—and the value of environmental factors (e.g., air temperature, relative humidity, air velocity, and solar radiation). All of these together affect the ability to dissipate heat generated in the body [57]. This is necessary to maintain the body’s thermal balance.

This can cause physiological and behavioural responses, leading to physiological disorders that negatively affect agricultural efficiency, productivity, and reproductive performance [58,59].

THI is a widely used bioclimatic indicator [60].

One of the first formulas used to determine the value of THI is that developed by Thom (Formula (1)) [61,62], which is used as an indicator of human comfort by the US Meteorological Administration.

THI is expressed as a single value representing the combined effects of air temperature and humidity, which is commonly used to assess the degree of heat stress in animals [63,64].

Several thermal indices that the THI formulas use in animal studies have been compared, and it was found that indoor relative humidity is the dominant factor for heat stress in animals in humid climates, while the temperature of the dry thermometer is more important in dry climate conditions [65,66]. The most unfavourable combination of parameters is a set of high temperature with high humidity (more than 80%) and small air exchange. In this case, high levels of temperature–humidity index (THI) may occur among horses.

The minimum and maximum value ranges for the formula used have been defined. The optimal zone for horse well-being with this indicator is 48 ≤ THI ≤ 67, which indicates an adequate level for the environment; 67 < THI ≤ 80 indicates a moderate level of heat stress; THI > 80 indicates a severe level of heat stress. The values of 43 ≤ THI ≤ 48 indicate a slight discomfort due to a too-low ambient temperature, and below THI = 43 represents unsuitable conditions, well outside the thermoneutral zone. Non-optimal air parameters negatively affect the health of animals, including horses, their physical and mental fitness and condition, lowering the welfare level [50,51,52,53]. Furthermore, in deviating from optimal zoo-hygienic standards in the conditions of keeping horses, violating the homeostasis of the system can lead to a decrease in immunity and the occurrence of diseases of environmental aetiology [54,55,56,57].

Horses show a much higher tolerance to cold. This is the reason why the effect of cold stress on nutrient utilisation and animal welfare has received less research attention. In the tropics, subtropics, and temperate regions during summer, heat stress is a major concern for the welfare of farm animals.

Horses find it difficult to cope with conditions of excessive humidity. Excess humidity worsens their well-being and increases the risk of respiratory diseases [40]. It also causes faster degradation of the building, stored equipment, and indoor furniture. Relatively high humidity prevents animals from releasing heat into the environment by evaporating from the body surface.

where t is the dry bulb temperature (°C) and is the relative humidity of the air (%).

As a result of being under thermal stress conditions, horses show a number of signs, such as, among others, the following [67]:

- High rectal temperature (103–107 °F or 39.5–41.5 °C);

- Increased heart rate at rest;

- Rapid breathing and flared nostrils at rest;

- Rapid heart rate;

- Dehydration: loss of skin elasticity, tacky gums, sunken eyes, and reduced urine output;

- Exhaustion or lethargy;

- Excess sweating and hot skin;

- Reduced feeding intake;

- Incoordination;

- Heatstroke symptoms such as weakness;

- Stumbling.

Figure 3 shows that in the most unfavourable climatic conditions, the air parameters leaving the GAHE do not exceed the value of the THI equal to 67.

1.6. Solution Idea

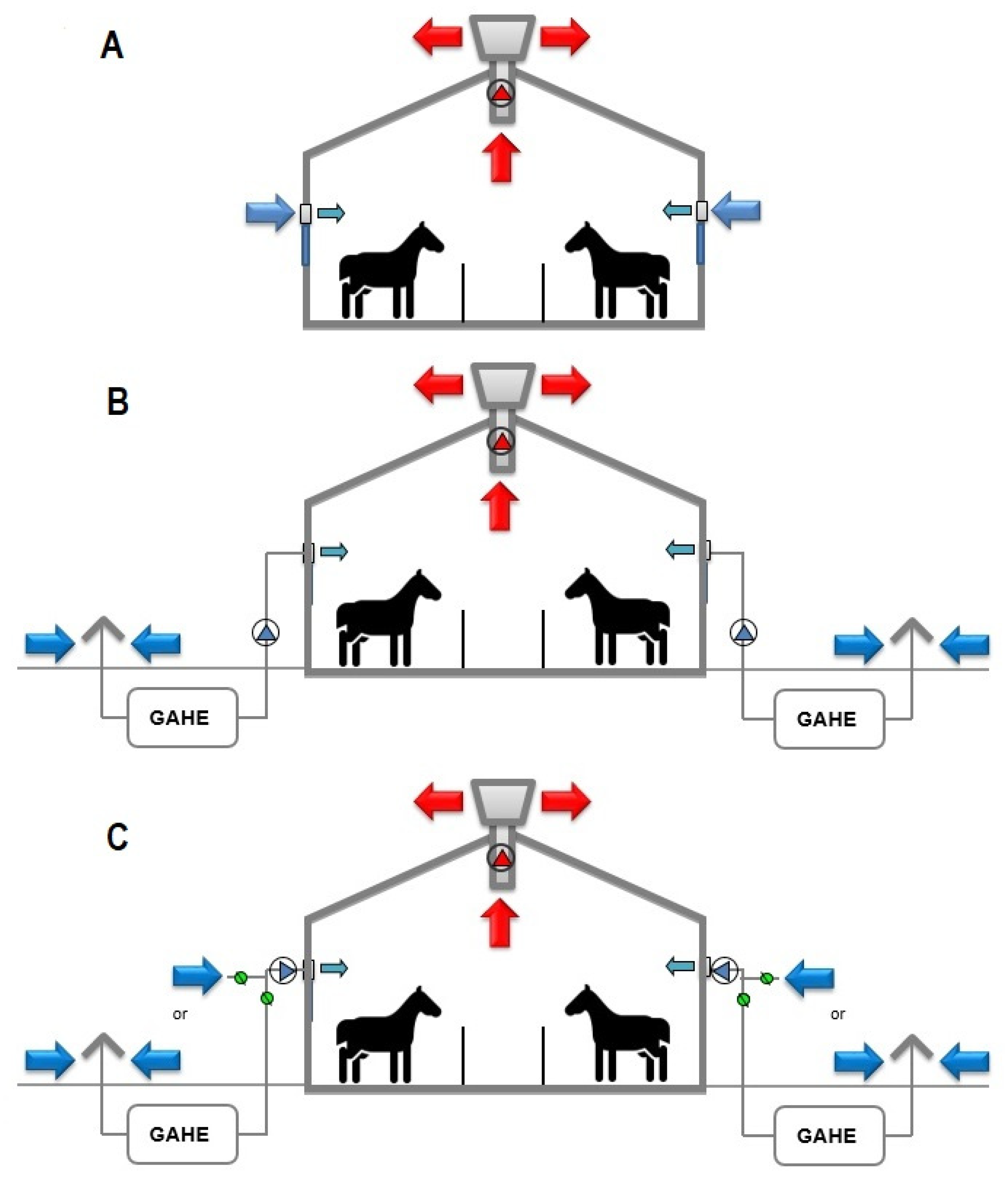

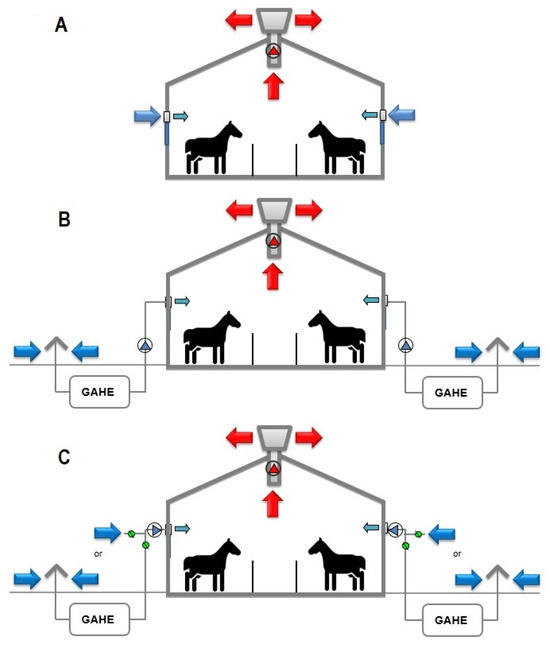

Standard solutions for horse-stable mechanical ventilation are presented in Figure 4. Fresh air is supplied directly to the stall-box zone through ventilation inlets installed in the external walls. The used air is removed through ventilation exhaust points located under the horse stable roof.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the ventilation system: (A) natural or mechanical ventilation system; (B) proposed supply and exhaust mechanical ventilation system, air supplied by GAHE; (C) proposed supply and exhaust mechanical ventilation system, air supplied through or bypassed by GAHE. Blue arrows—fresh air; red arrows—exhaust air; blue triangle—mechanical fan; green circles—dampers.

The innovative solution proposed in this manuscript involves implementing a GAHE heat exchanger into a typical horse-stable ventilation system. Variations of this concept are presented in Figure 4A–C. In Figure 4A, the exhaust fan supports the natural ventilation of the horse stable, and can only be activated periodically in the event of unfavourable conditions in the stall-box zone. In Figure 4B, the flow of fresh ventilation air is directed through the GAHE, and the exhaust of stale air is supported (or not) by the exhaust fan. In Figure 4C, the mechanical ventilation can directly use fresh outside air or first route it through the GAHE, with the exhaust of stale air also supported (or not) by the exhaust fan. The use of both supply and exhaust mechanical ventilation allows for better organisation and control of airflow throughout the horse stable.

Depending on the time of year, heated or cooled air is supplied to the room, providing a more favourable microclimate. As a result of this, temperature fluctuations in air entering a building, as well as air already inside it, both in daily and seasonal cycles, are considerably lower. This noticeably increases animal comfort and provides the beneficial effects of the use of GAHEs.

1.7. Research Gap and the Aims of This Paper

Numerous publications focus on optimising microclimatic conditions, the energy efficiency of ventilation systems, and the impact of these factors on animal health and productivity.

Nevertheless, despite the wealth of existing research, a significant research gap has been identified. In the context of stable ventilation and improvements in microclimates, the potential application of GAHEs remains an underexplored or insufficiently described topic in the literature. There is a lack of comprehensive analyses of their effectiveness and the rationale for their implementation in this type of facility. In Poland, as well as other regions of the world, there is dynamic development in the construction of livestock buildings, including the emergence of many modern stables. In such facilities, the application of GAHE could bring significant benefits, both in terms of maintaining optimal microclimate parameters throughout the year and, consequently, contributing to the improvement in overall horse comfort and welfare.

In light of the identified gap, the main objective of this research paper is a comprehensive analysis of the possibilities and effectiveness of using a GAHE to improve microclimate parameters in a horse stable. Specific research aims include the following:

- Determining the practical feasibility of using a GAHE to provide optimal microclimate parameters in a typical stable, considering the facility’s specifics and the environmental requirements for horses;

- Investigating the influence of different types of ventilation systems and assumed air flows on the achieved microclimate parameters in the stable, with particular attention given to inside air temperatures and humidity values obtained by using a GAHE.

1.8. Novelty of This Paper

The novelty of this research paper is manifested in several key aspects that distinguish it from existing scientific publications:

- Pioneering analysis of the application of thoroughly researched ground-air heat exchangers (GAHEs) in the context of modern stable design. Previous research on GAHEs has focused mainly on residential buildings, office buildings, or certain types of industrial facilities. This paper fills a gap in the literature by presenting a detailed analysis of the possibilities of integrating and operating GAHEs in the specific environment of a modern horse stable, taking into account its unique ventilation and comfort requirements.

- A comprehensive approach to improving the microclimate in horse stables using GAHEs. The paper is not limited to a general description of the system, but thoroughly analyses how a GAHE can actively influence indoor air temperature and humidity, contributing to optimising the conditions for animals. This represents a significant expansion of current knowledge with respect to the applications of this technology. Furthermore, the research highlights the viability of a simple, low-cost GAHE system constructed from readily available materials and harnessing renewable geothermal energy to achieve indoor air parameters comparable to those of conventional HVAC systems, which are not only capital-intensive but also energy-demanding in operation. This sustainable alternative presents a cost-effective, environmentally friendly solution for optimising horse stable environments without compromising performance or animal health.

- A detailed comparison of the performance of the proposed solution with traditional ventilation systems that do not utilise a ground-air heat exchanger. This analysis covers not only technical and energy parameters but also potential benefits for horse welfare and the indoor environment, providing empirical evidence for the advantages of GAHEs under specific conditions.

- Development of a proposal for an innovative ventilation control system for horse stables, considering the specific operation of the GAHE. The presented control system concept aims to maximise the energy efficiency of the GAHE and optimally adapt microclimate parameters to changing external conditions and animal needs, thus providing a practical contribution to the development of intelligent ventilation systems in the construction of livestock buildings.

- Highlighting the benefits of using GAHEs in the fight for horse health by delivering filtered, cleaner, fresher, and more thermally stable air to horse stables. The resulting improvement in the microclimate can directly translate into a reduced risk of respiratory diseases and an overall improvement in animal welfare.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis

All analyses were performed in the EDSL TAS simulation programme v. 9.5.6. EDSL TAS works on the EnergyPlus engine. This GUI software is used in both the typical building design process and advanced energy analyses carried out by scientific institutions in many countries.

The EDSL TAS software v. 9.5.6. consists of three main modules and many auxiliary databases. In the TAS 3D Modeller, a three-dimensional model of the analysed stable building was developed, location data were entered, and calculations related to the solar radiation of the building were performed (daily step). In the auxiliary databases, the details of the construction, including all stable partitions, were collected, and the official climate data, parameters of internal conditions, and operating schedules of individual spaces were entered. The data collected were used to create two variants of simulation models of the stable: the first was a typical mechanically ventilated building, the second was supported by a GAHE. Verified through many years of research (for example, [7,8]), the two-phase heat and mass transfer model in a ground exchanger formulated by Kowalczyk [68] was used to simulate the operation of the GAHE. The EDSL TAS model was created using a precisely defined set of design data based on the parameters and dimensions of the ground-air heat exchanger, which were individually tailored to the specific ventilation system of the horse stable under analysis. The further impact of the air supplied from the GAHE on the analysed parameters of the horse stable was calculated thanks to the computational algorithms built into the EnergyPlus engine. Based on the models prepared in this way, the required simulations were performed; then, the results were exported and prepared for presentation in the Result Viewer. With each data export to subsequent modules, a detailed validation of both the definition of the model itself and the obtained results was carried out.

2.2. Assumptions

2.2.1. Basic Building Parameters

The stable is located in the city outskirts of Wrocław, in the second Polish climate zone, where the external air design temperature is −18.0 °C. The models were created using meteorological data downloaded from the EnergyPlus database, which is based on IMGW official data [69,70].

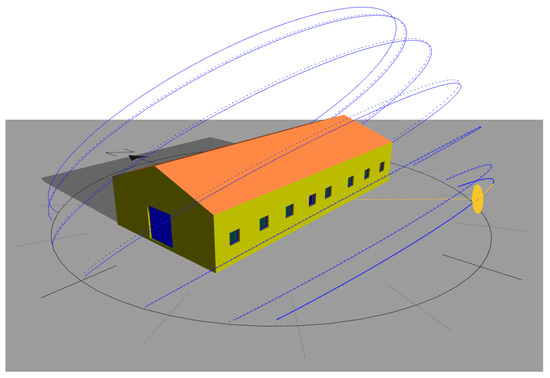

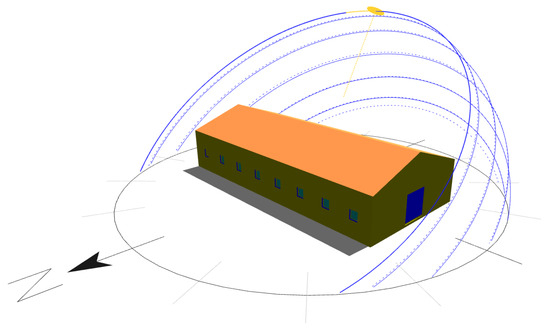

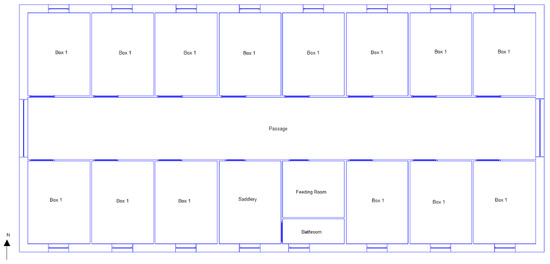

The data used in all the simulations and the horse stable geometry are presented in Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 and Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7. Information on the building, comprising the construction parameters, type of use and schedules, localisation, etc., was adopted on the basis of the design documentation and the literature.

Table 3.

The output data entered into the models used in all simulations performed.

Table 4.

Basic geometric parameters of the analysed horse stable.

Table 5.

Materials used for the construction and glazing of simulation models.

Table 6.

Basic HVAC parameters used in all simulations.

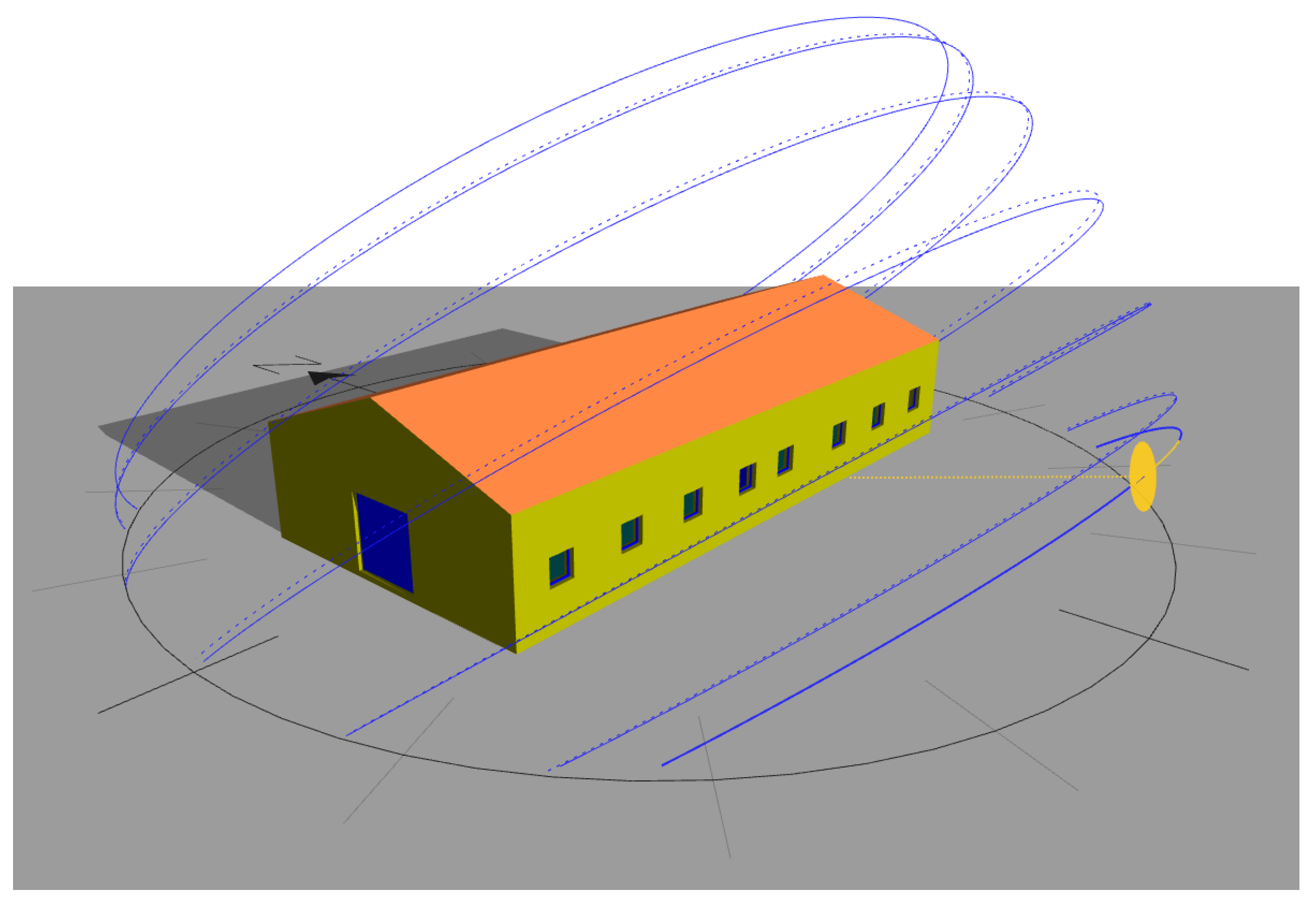

Figure 5.

Geometry of the simulation model, S-W angle view, sun position on 355th day at 12:00 h (the shortest day in 2025), TAS 3D Modeller. Additional blue and yellow elements—sun, sun arcs and movement of the sun during the year.

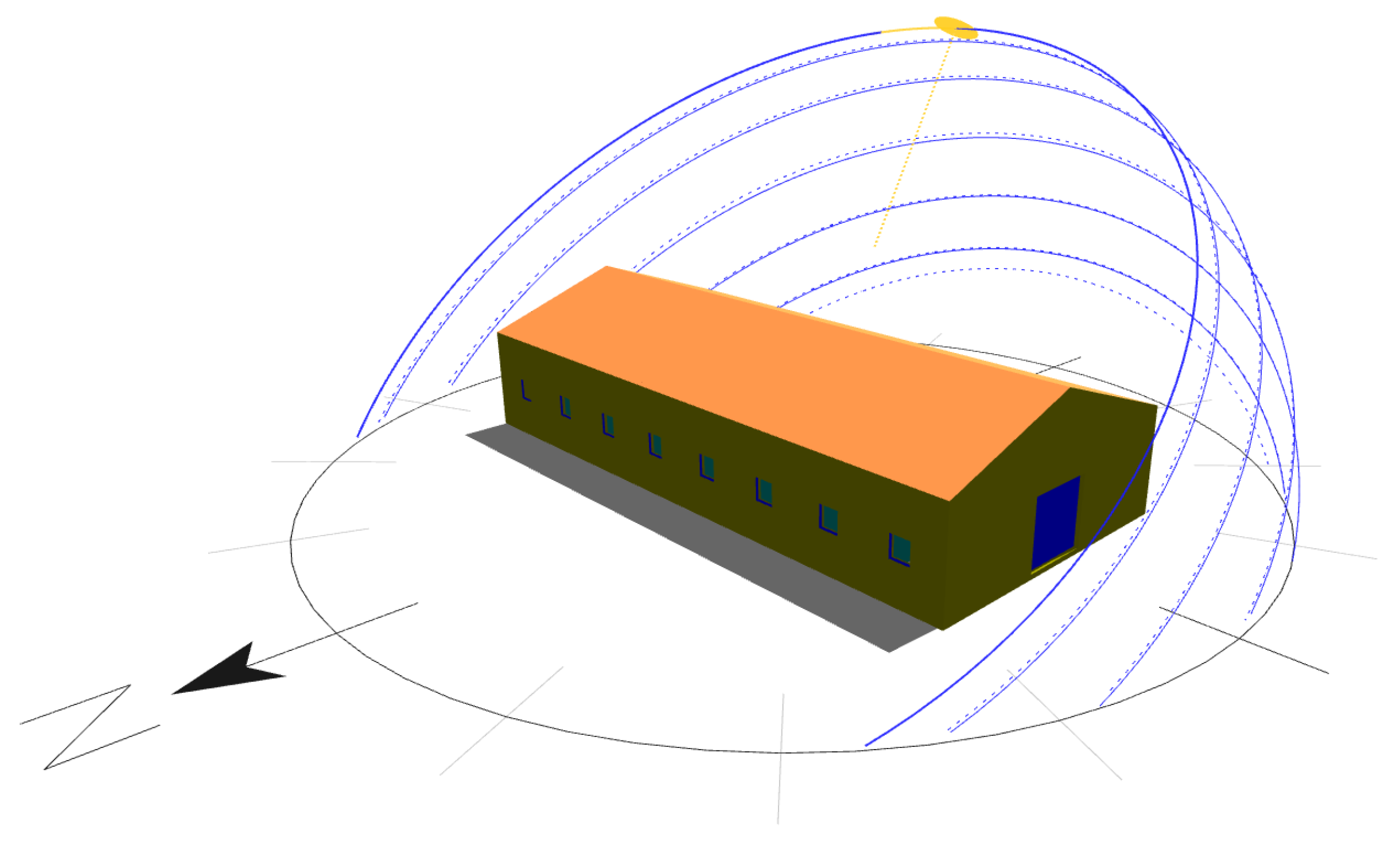

Figure 6.

Geometry of the simulation model, N-W angle view, sun position on 172nd day at 12:00 h (the longest day in 2025), TAS 3D Modeller. Additional blue and yellow elements—sun, sun arcs and movement of the sun during the year.

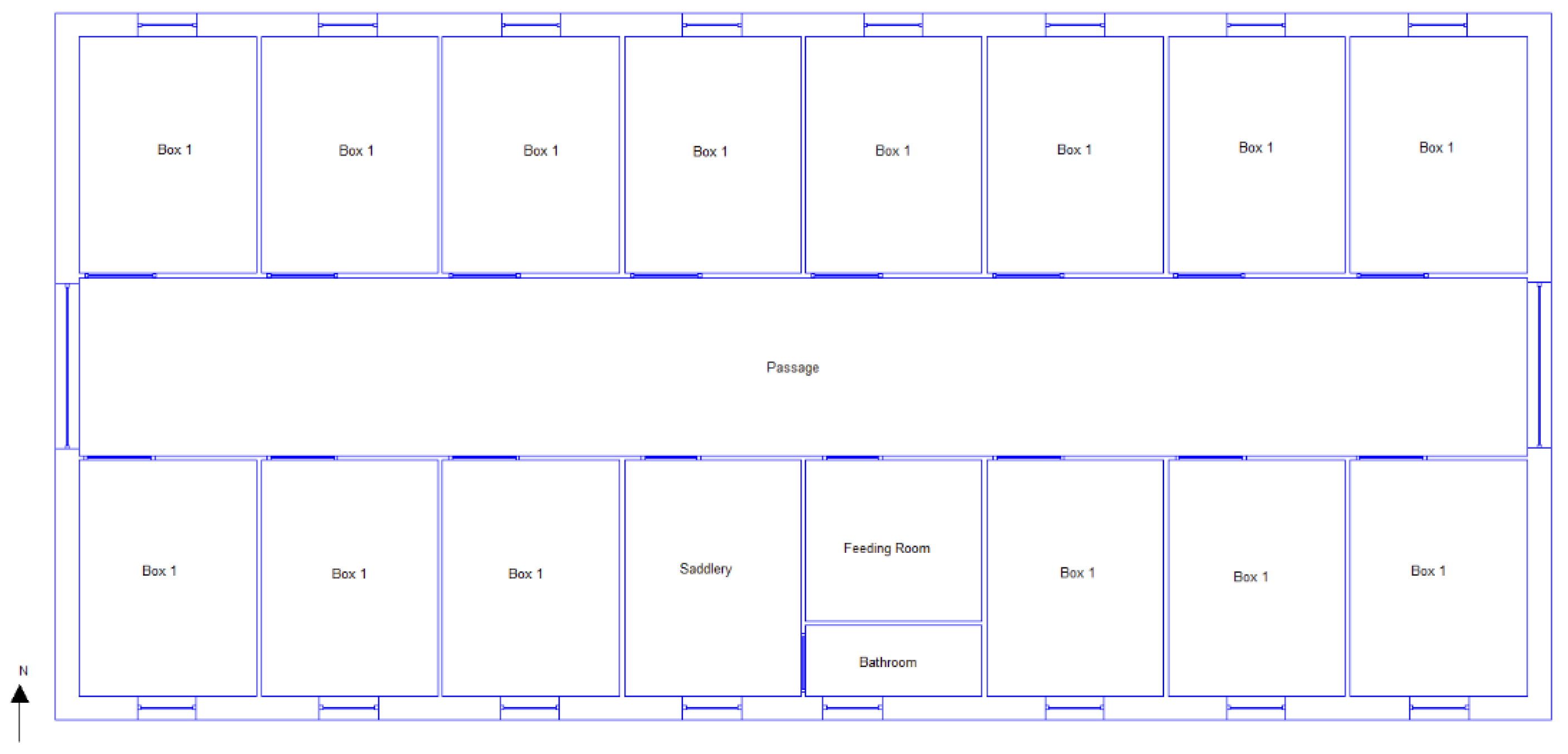

Figure 7.

Geometry of the simulation model, ground floor plan view, TAS 3D Modeller.

The stable building analysed was designed for 14 adult horses with an average weight of 700 kg; the horses are used for recreation (under light training conditions). It is a single-story building, without a basement. The horses are kept in separate box stalls. The building contains auxiliary rooms: a feeding room, a saddlery, and a bathroom. All box stalls and auxiliary rooms are connected by a common passage that runs throughout the building. There is heavy construction of the external walls, lightweight construction of a gable roof, and internal partitions. The box stalls and the auxiliary rooms are equipped with windows measuring 1.00 × 1.00 m—all with reinforced glazing that is safe for horses. On both sides of the passage, there are entrance gates measuring 2.80 × 2.80 m, which allow for emergency ventilation of the horse stable.

The final geometry of the model of the analysed horse stable building is presented in Table 4 and in 3D visualisations of Figure 5 and Figure 6. The arrangement and shape of individual rooms are presented in a simplified way in Figure 7.

To ensure the most stable indoor conditions, a heavy external wall construction was used—a brick wall made of Porotherm 38 Profi ceramic blocks [71] covered on both sides with cement–lime plaster. Light PU ARGO roof panels with good insulation properties that are insensitive to moisture condensation were used in the construction of the gable roof. An important structural element was the appropriately selected glazing. Finally, monolithic laminated SunGuard HD Neutral 67 [72] glass was used; this kind of material ensures the safety of animals while maintaining the best possible insulating properties and solar radiation transmittance. The details of all the “construction elements” used in the stable models are presented in Table 5.

2.2.2. Building Internal Conditions—Internal Heat Gain Calculation Method

The stable building was divided into six separate simulation zones: Box 1 (all box stalls), passage, saddlery, feeding room, bathroom, roof (open space under the gable roof and above the other zones). The layout of the simulation zones is shown in Figure 7. Separate internal conditions were assigned to each zone, consisting of the values of the internal sensible and latent heat gains, among others. These parameters are particularly important because of their high dependence on changes in internal air temperature and their influence on general conditions in a stable living space.

The total heat production of a horse at a temperature of 20.0 °C was calculated based on the following formula [73,74]:

where

Φtot—total heat production by a horse at a temperature of 20 °C, W;

m—body mass of a horse, kg;

K—horse activity coefficient, -;

Φm—horse heat dissipation due to maintenance, W.

The total heat production of a horse at a lower temperature than 20 °C expressed per hpu was calculated on the basis of the formula below [73,74]:

where

—total heat production by a horse at a temperature different from 20.0 °C, W;

tlsh—stall boxes current internal air temperature, °C;

hpu—heat-producing unit (1000 W in total heat at 20.0 °C).

The sensible heat production of a horse at a temperature different from 20 °C, expressed per hpu, was calculated on the basis of the formula outlined below [73]:

where

—sensible heat production by a horse at a temperature different from 20 °C, W;

ks—correction factor for sensible heat.

The latent heat production by a horse at a temperature different from 20 °C, expressed per hpu, was calculated on the basis of the following formula [73,74]:

where

Φl,hpu—latent heat production by a horse at a temperature different from 20 °C, W;

Φtot,hpu—total heat production by a horse at a temperature different from 20 °C, W;

Φs,hpu—sensible heat production by a horse at a temperature different from 20 °C, W.

In the studied horse stable, it was assumed that the animals would be housed individually, each in an individual box. Therefore, the internal sensible and latent heat gains from the animals were entered directly into the stall-box (Box 1) calculation zone as average hourly values, given in W/m2 of the zone area. Specific hourly values of those internal heat gains were calculated based on Formulas 4 and 5 (value ranges are given in Table 6). The location and shape of the zone are shown in Figure 7. Average internal sensible heat gains from lighting were assigned only within the roof calculation zone, which includes the space above the ground-floor rooms.

2.2.3. Building Internal Conditions—GAHE Simulation Data

The parameters of the EDSL TAS “Indoor conditions” function for the GAHE were created by assigning the minimum and maximum values of the supply air temperature and its relative humidity for the GAHE—calculated in the previous stage of this work—for each hour of the simulation year separately. The air temperature and humidity after passing through the GAHE took into account the changes in ventilation air volume between the minimum value of 2650 m3/h (4.0 ach) and the maximum value of 5300 m3/h (8.0 ach).

The values used were based on the guidelines of [2,3,32] and Wroclaw weather data (WMO Region 6/POL/Station no. 124240).

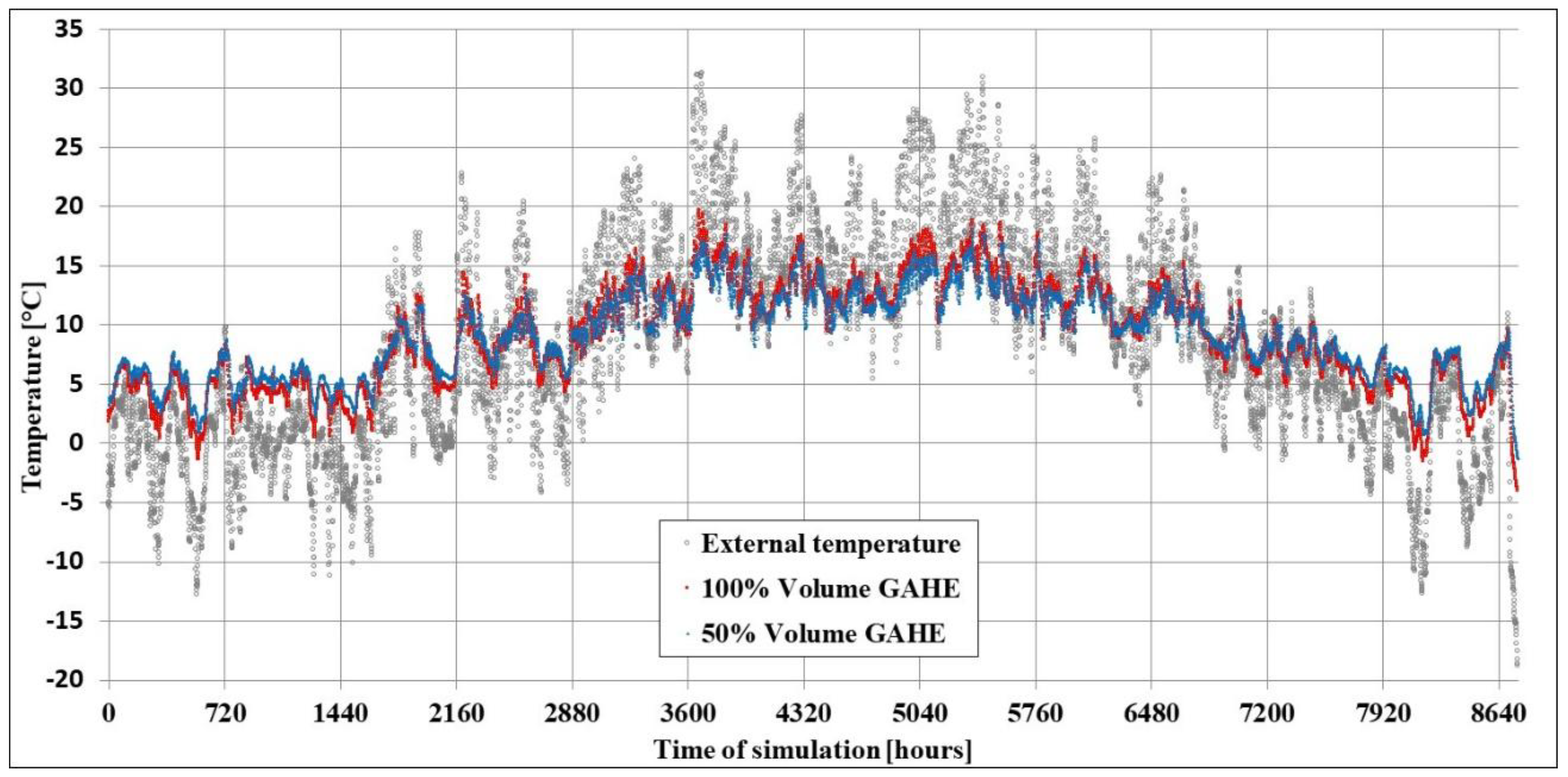

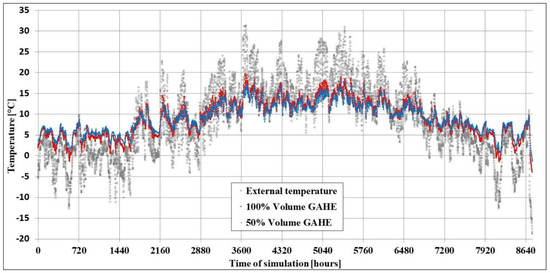

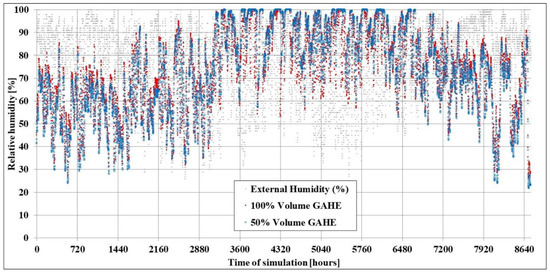

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the inlet and outlet air parameters (temperature and relative humidity) obtained in the GAHE with dimensions of 1.5 m × 8.0 m × 5.0 m (Height × Width × Length) at 100% and 50% of the design air flow for the year of its operation.

Figure 8.

Values of air temperature after GAHE during the year.

Figure 9.

Values of relative air humidity after GAHE during the year.

2.3. Options Considered and Research Routes

Considered Variants of Ventilation Schemes

The following describes the assumptions made for each variant of the stall-box zone (Box 1) ventilation schemes analysed:

- Variant 0 Outside—the horses are kept outside in external conditions, second Polish climate zone.

- Variant 1 no GAHE, 4.0 ach—ventilation air volume set to a minimum acceptable value at 2650 m3/h (exchange rate 4.0 ach), no GAHE used.

- Variant 2 GAHE, 4.0 ach—ventilation air volume set at a minimum acceptable value at 2650 m3/h (exchange rate 4.0 ach), GAHE supported ventilation.

- Variant 3 no GAHE, 8.0 ach—ventilation air volume set to a maximum acceptable value at 5300 m3/h (exchange rate 8.0 ach), no GAHE used.

- Variant 4 GAHE, 8.0 ach—ventilation air volume set to a maximum acceptable value at 5300 m3/h (exchange rate 8.0 ach), ventilation supported with GAHE.

- Variant 5 MIX—ventilation air volume and GAHE usage controlled based on outside air temperature and time of day, details presented in Table 7.

Table 7. Parameters of ventilation air volume and GAHE usage in stall-box (Box 1) zone of Variant 5 MIX in relation to the outside air temperature and the time of day.

Table 7. Parameters of ventilation air volume and GAHE usage in stall-box (Box 1) zone of Variant 5 MIX in relation to the outside air temperature and the time of day.

The range of a minimum of 2650 m3/h (exchange rate 4.0 ach) and maximum of 5300 m3/h (exchange rate 8.0 ach) of supply air volume was adopted based on [39] and described in Table 2.

For the Variant 5 MIX, the lower switching point of 8 °C and the upper switching point of 15 °C were determined based on [24]. Hours between 4:00 am and 7:00 pm were assigned as daylight hours due to the occurrence of positive values of solar global radiation during these hours in the used weather data.

3. Results

3.1. Results of Calculations and Analyses

3.1.1. Current Standard—Mechanically Ventilated Stable

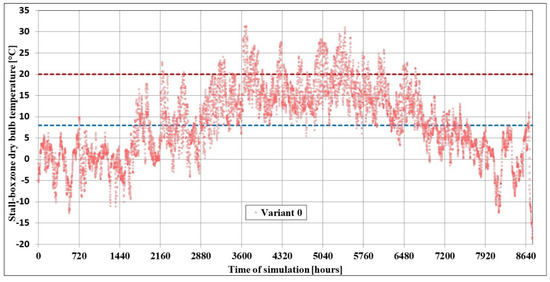

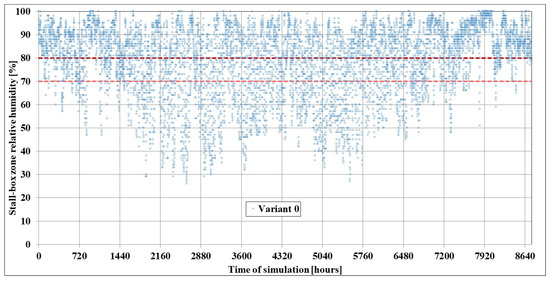

The calculations of the parameters analysed were performed for the five operating variants of the ventilation system described above. The results calculated for Variant 0 show the conditions under which the horses would stay outside in the moderate climate of Wroclaw. This variant was treated as the most unfavourable but still acceptable for animals, and the effects of using subsequent solutions were compared with its results.

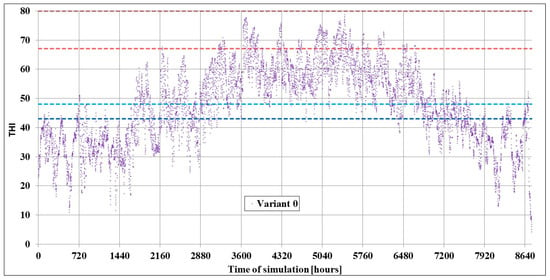

For Variant 0, the outside air temperature varies from −18.8 to 31.3 °C (Figure 10). Relative humidity ranges from 26.0 to 100.0% (Figure 11). The THI ranges from 4.2 to 78.7, and its average annual value is 47.2 (Figure 12).

Figure 10.

Variation in the external air temperature value during the simulation period—Variant 0. Red and blue lines—maximum and minimum values of suggested comfort air temperatures for horses.

Figure 11.

Variation in the external relative humidity value during the simulation period—Variant 0. Red and light red lines—maximum permissible and maximum optimal air humidity limits suggested for horses.

Figure 12.

Variation in the THI value during the simulation period—Variant 0. Red, light red, light blue and blue lines—maximum permissible, maximum optimal, minimum optimal, minimum permissible THI value for horses.

The analysed data indicate a problem of significantly exceeding the previously described horse-comfort thresholds:

- Too-low air temperatures, values below 8.0 °C, occurred for 4332 h (49.5% of the year);

- Too-high air temperatures, values above 20.0 °C, occurred for 699 h (8.0% of the year);

- Too-high relative air humidity, values above 70.0%, occurred for 6523 h (74.5% of the year);

- The maximum daily fluctuation in air temperature was 19.0 °C.

The THI values in the analysed period were outside the optimal range for 5011 h. In this period, the THI values were too high for 580 h. There were no cases where THI reached values above the safe range causing heat stress in horses (THI > 80); however, values below thermal comfort conditions (THI < 43) occurred for 3490 h.

These conditions are acceptable for horses, but at the same time, they are far from providing the level of comfort described in the literature [61,62,65,67] (other parameters of the external environment, such as rain, excessive solar radiation, or wind gusts, were not taken into account). The main problem is the inability to maintain the minimum air temperature for almost half a year in total. These conditions contribute to a significant increase in horse feed consumption [42,43]. Long periods of increased relative air humidity increase the risk of the development of pathogenic factors and moulds, negatively affecting the health of horses [40]. At higher outside air temperatures, high relative humidity also makes it difficult for horses to cool down naturally, further burdening them and increasing the daily demand for drinking water [42,43]. Long-term high air temperatures and high relative humidity lead to an excessive increase in horse internal body temperature; they also affect unfavourable heart and respiratory rates [2].

Large daily temperature fluctuations can also increase the stress level of horses and further increase the risk of disease [40].

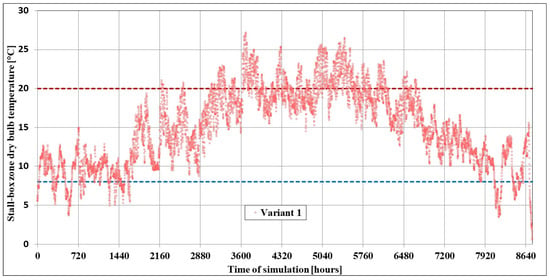

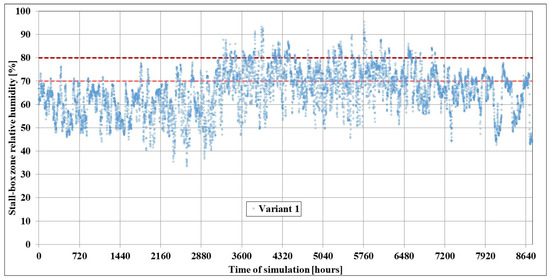

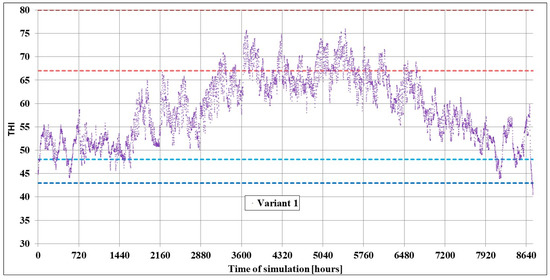

In Variant 1, the current standard, the mechanically ventilated stable was analysed. The minimum recommended external air flow to the stall-box zone was maintained at a constant level of 4,0 ach exchange rate throughout the year.

In Variant 1, a reduction in range from min. –18.8 °C and max. 31.3 °C to min. 0.5 °C and max. 27.2 °C (Figure 13) of air temperature was achieved. In addition, the relative humidity range was reduced from min. 26.0% and max. 100.0% to min. 33.4 and max. 95.25% (Figure 14); the THI ranged from 42.8 to 81.5, and its average annual value is 66.0 (Figure 15).

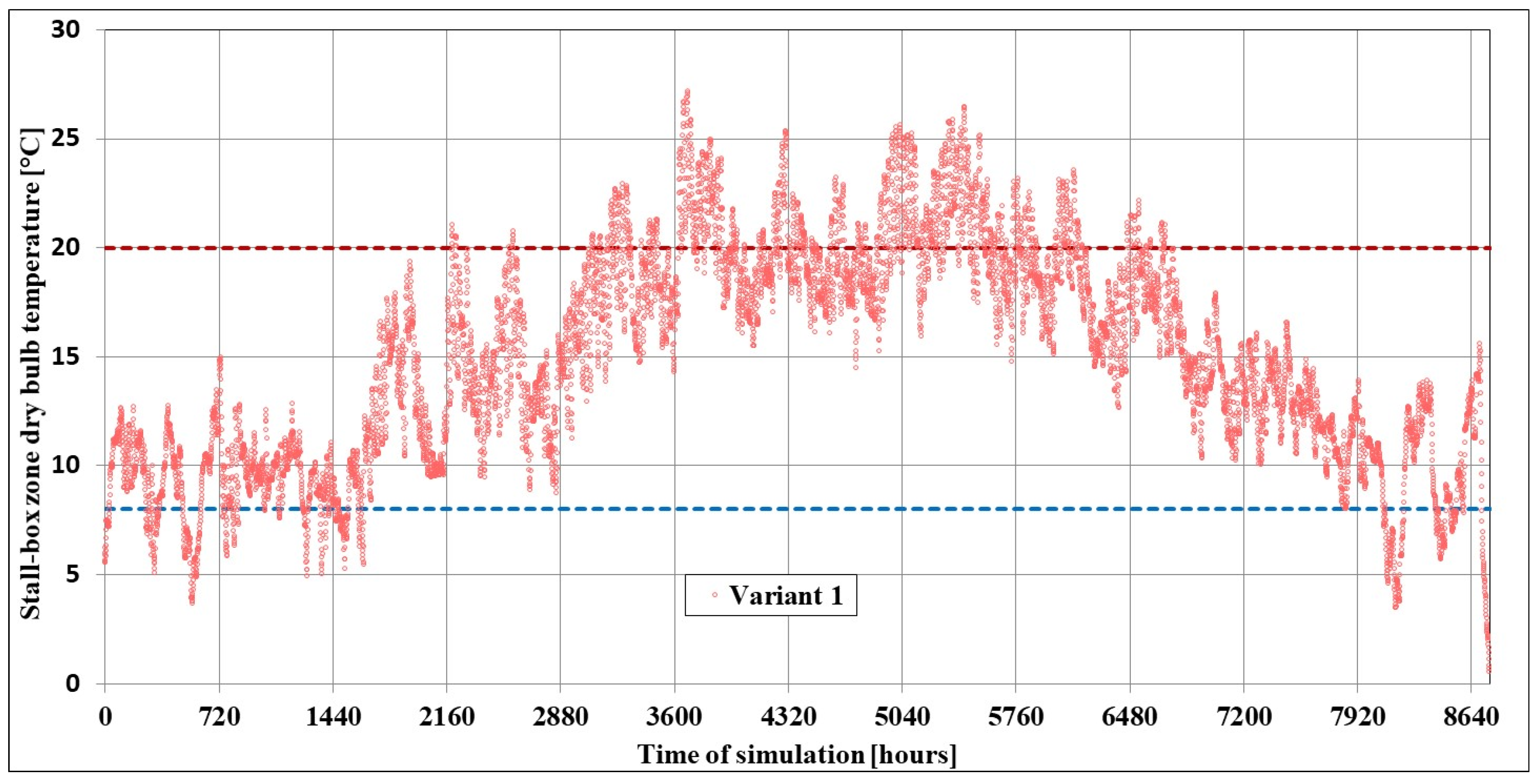

Figure 13.

Variation in the internal air temperature value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 1. Red and blue lines—maximum and minimum values of suggested comfort air temperatures for horses.

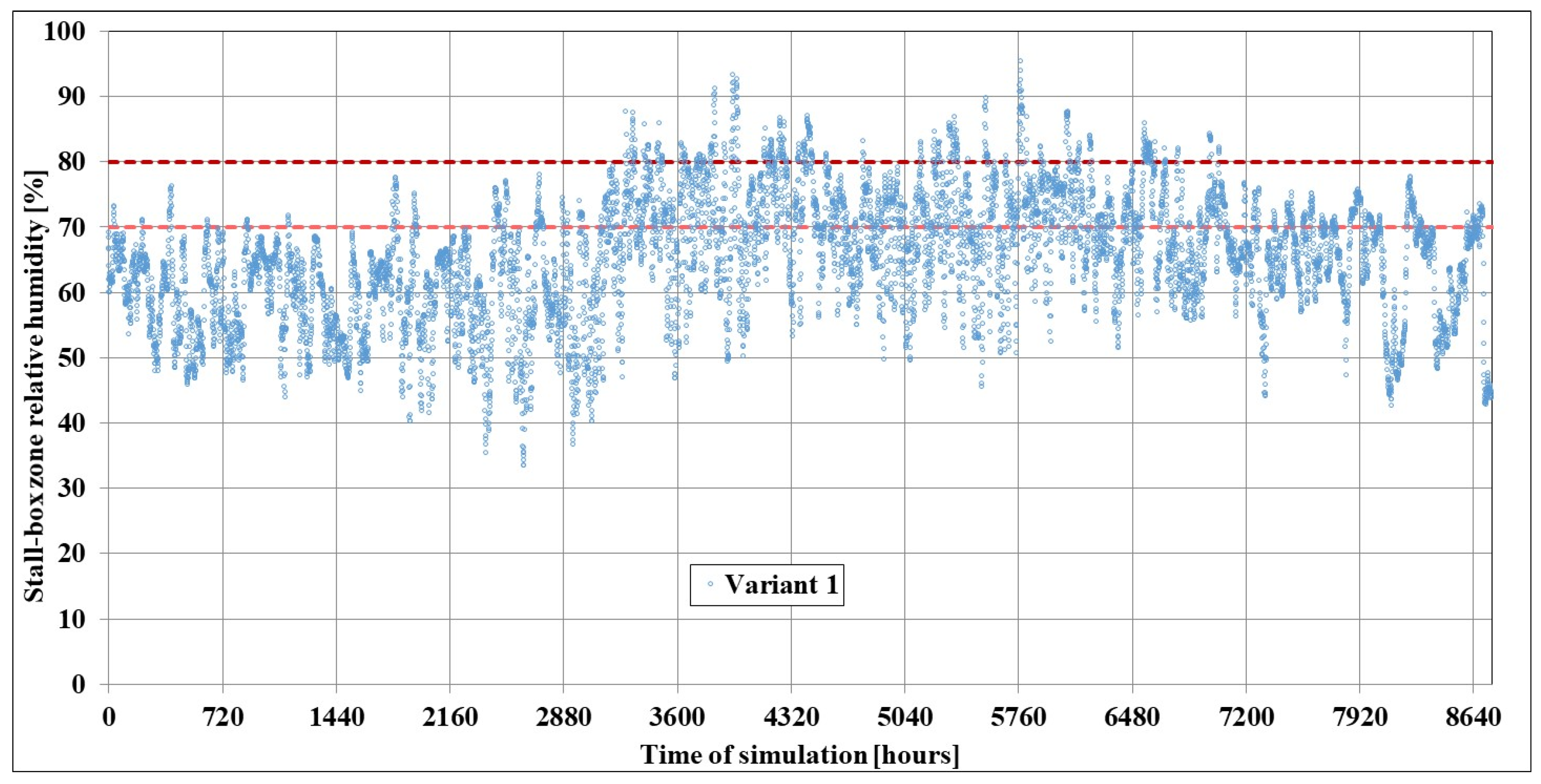

Figure 14.

Variation in the internalrelative humidity value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 1. Red and light red lines—maximum permissible and maximum optimal air humidity limits suggested for horses.

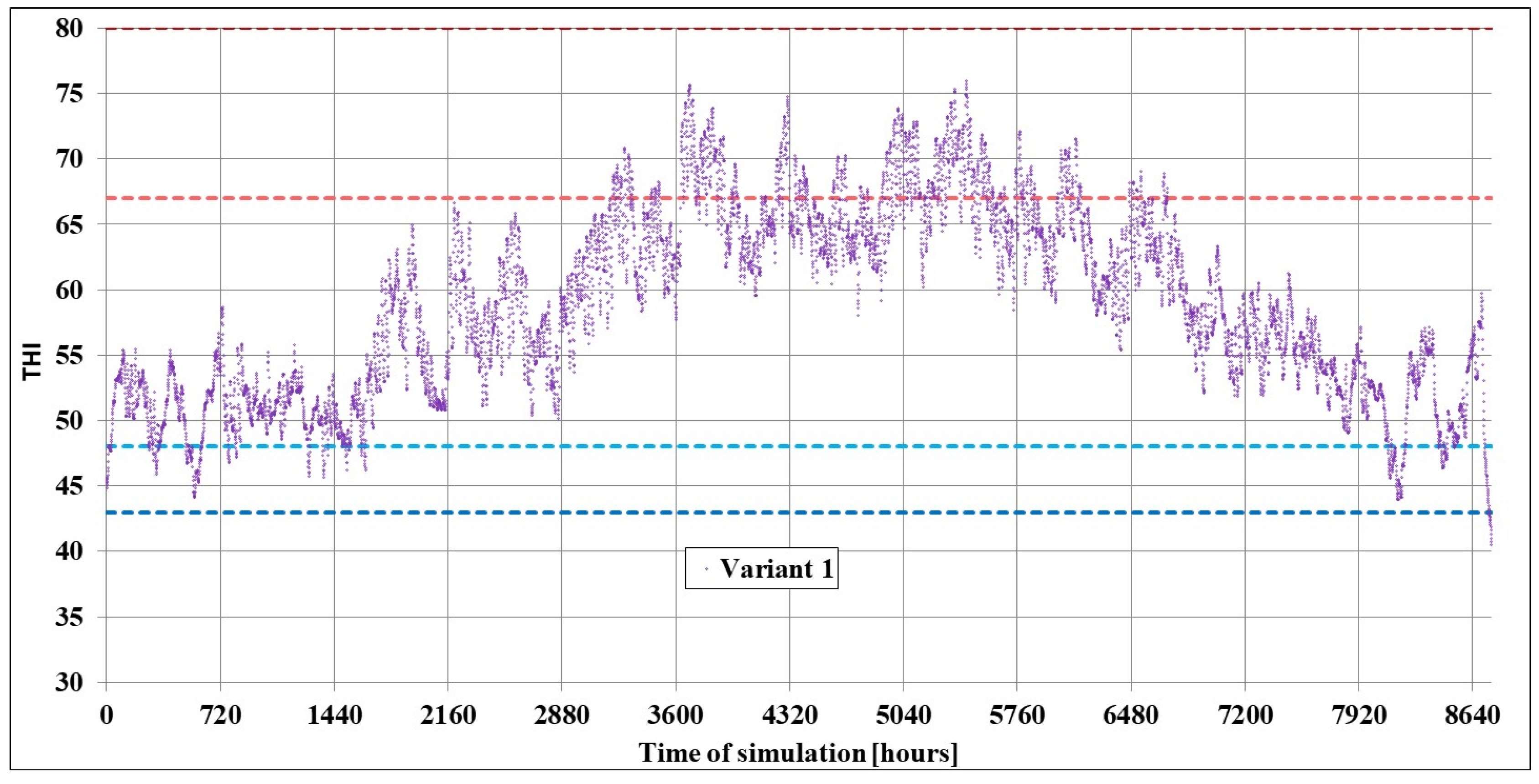

Figure 15.

Variation in the THI value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 1. Red, light red, light blue and blue lines—maximum permissible, maximum optimal, minimum optimal, minimum permissible THI value for horses.

Most of the horse-comfort threshold values described above were improved in Variant 1:

- Too-low air temperatures, values below 8.0 °C, occurred for 684 h (7.8% of the year), a reduction of 3648 h;

- Too-high air temperatures, values above 20.0 °C, occurred for 1451 h (16.6% of the year), an increase of 752 h;

- Too-high relative air humidity, values above 70.0%, occurred for 2763 h (31.5% of the year), a reduction of 3760 h;

- The maximum daily fluctuation in air temperature was 9.2° C, a reduction of 9.8 °C.

The THI values in the studied period were outside the optimal range for 1659 h. Of these, the THI reached values that were too high for 1268 h and values that were too low for 391 h. There was no case of the THI reaching values above the safe range that cause heat stress in animals (THI > 80); however, values below thermal comfort conditions (THI < 43) occurred for 15 h.

These conditions are better for horses. Horses spend most of the year sheltered, in higher and less-varied air temperatures. Unfortunately, a significant reduction in direct contact with external conditions, especially during the warm period, causes frequent exceedances of air temperature above comfortable levels. There are days when the temperature does not drop below 20 °C. Furthermore, despite a significant reduction in the occurrence of exceedances, high values of relative air humidity still occur for almost 1/3 of the year, affecting the deterioration of horse welfare and the physiological condition of horses [75].

Studies conducted in real facilities indicate similar changes in microclimate in different seasons of the year [2]. The average values of temperature measurements obtained during the winter period reached 3.7 °C in the tie stables and were slightly higher in the box stables [2,33]. The average level of relative humidity reached 81.8% in the tie-stall stable and 70.5% in the box stable [33].

3.1.2. Basic Application of GAHE

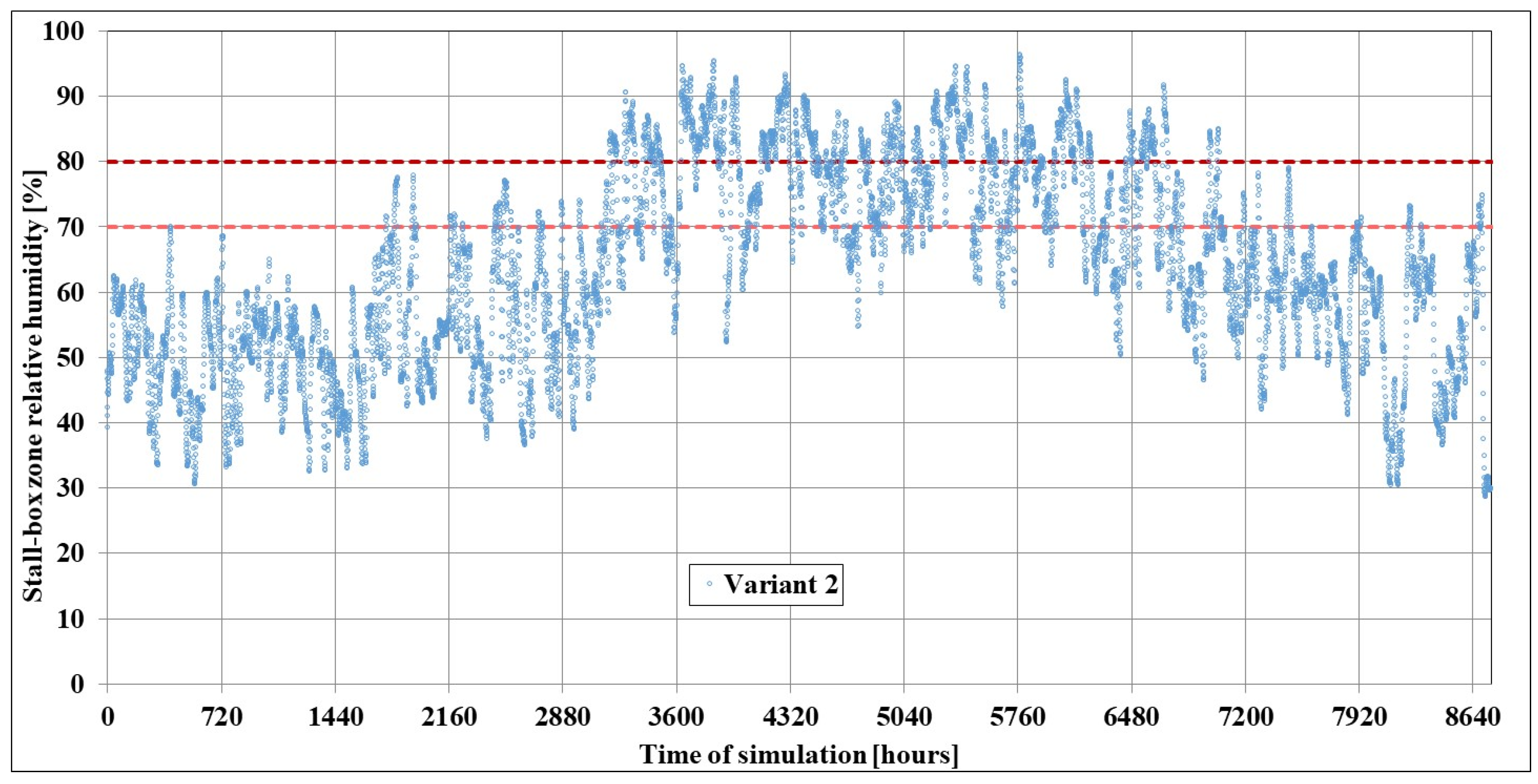

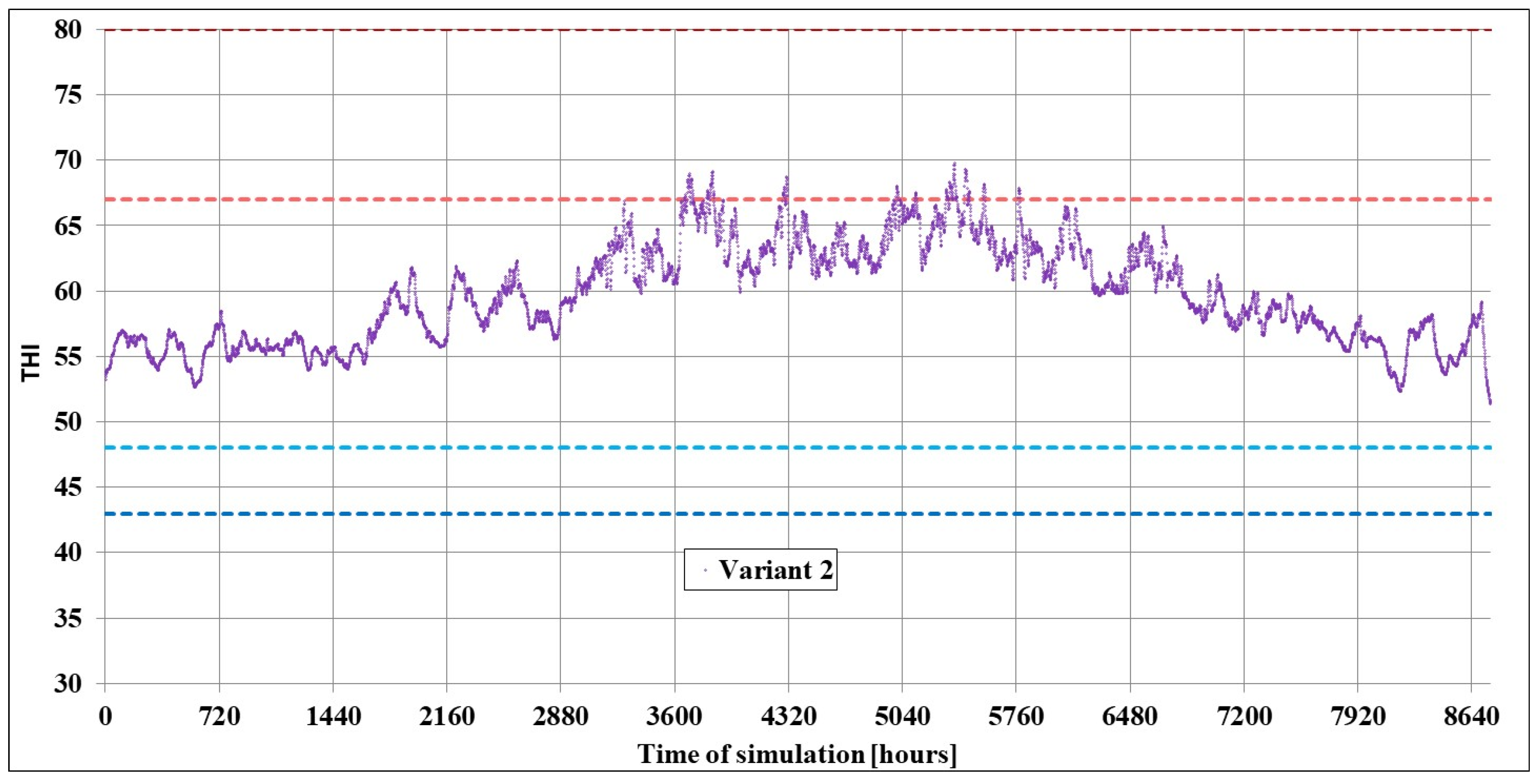

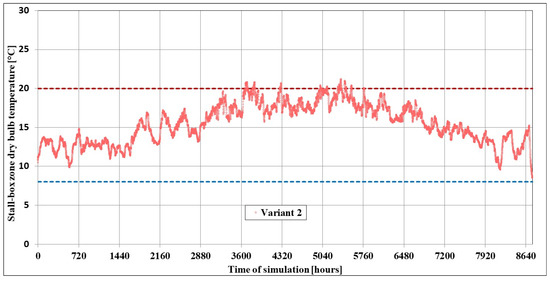

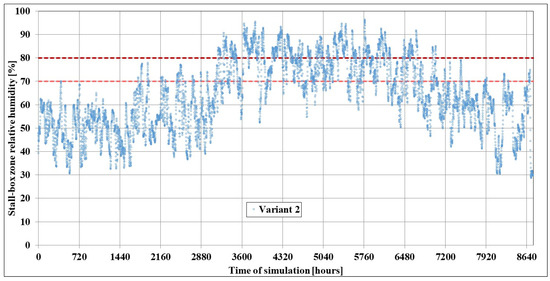

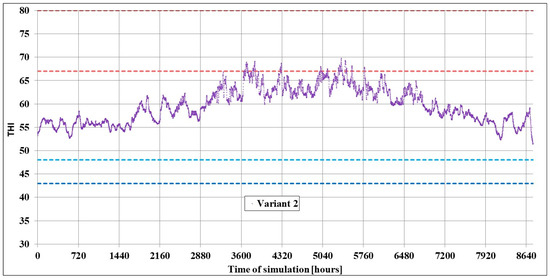

It was assumed that the use of a GAHE, as a support for the horse-stable ventilation system, would improve the comfort conditions of horses staying in the stall-box zone, and so Variant 2 was introduced. Mechanical ventilation, still operating with a constant external air flow to the stall-box zone of 4.0 ach exchange rate throughout the year, but supported by a GAHE, was analysed. A further reduction in the internal air temperature range was achieved between min. 8.5 °C and max. 21.2 °C (Figure 16); relative humidity ranged from min. 28.7% to max. 96.3% (Figure 17); the THI ranged from 42.8 to 81.5, and its average annual value is 66.0 (Figure 18).

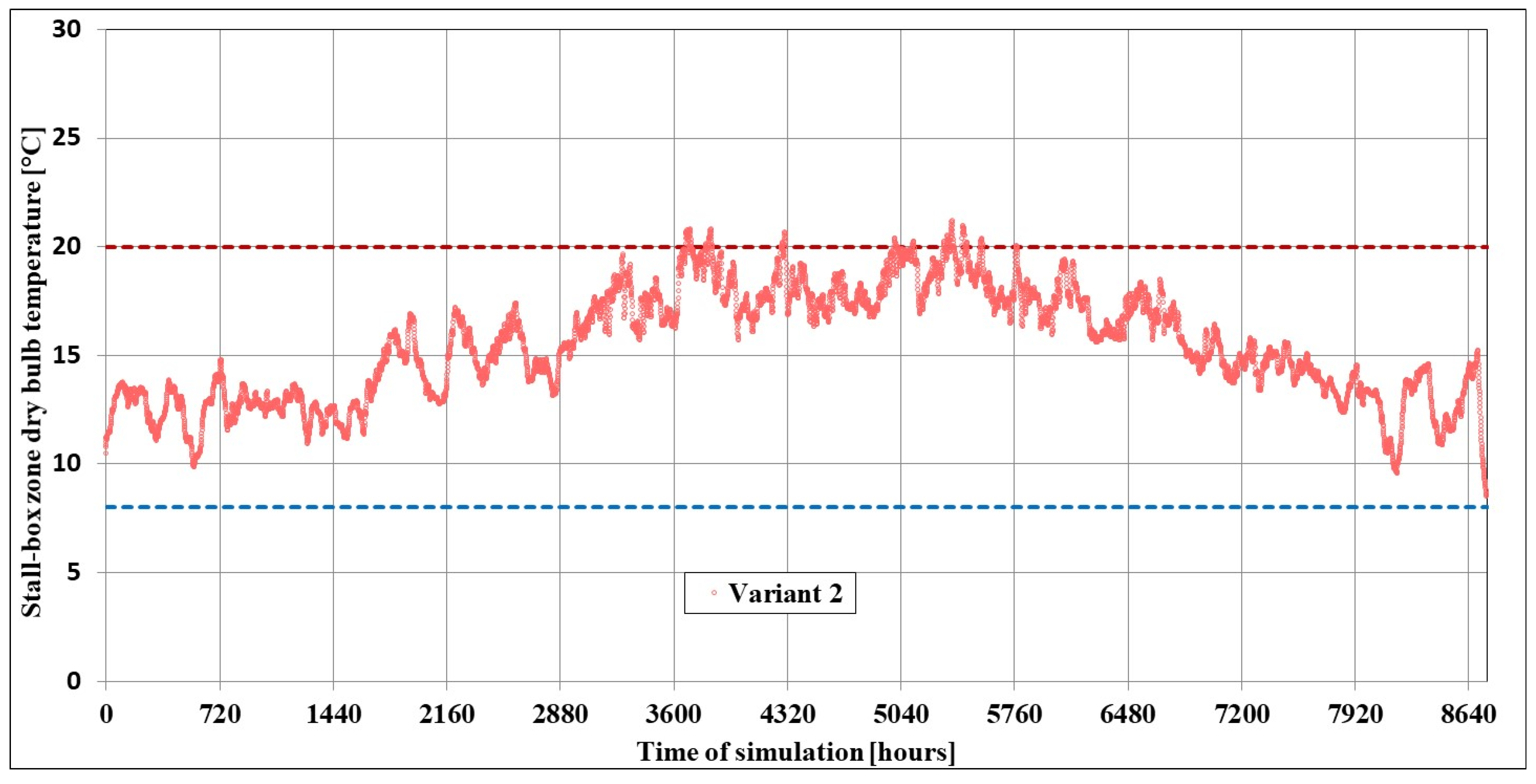

Figure 16.

Variation in the internalair temperature value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 2. Red and blue lines—maximum and minimum values of suggested comfort air temperatures for horses.

Figure 17.

Variation in the internalrelative humidity value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 2. Red and light red lines—maximum permissible and maximum optimal air humidity limits suggested for horses.

Figure 18.

Variation in the THI value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 2. Red, light red, light blue and blue lines—maximum permissible, maximum optimal, minimum optimal, minimum permissible THI value for horses.

The use of a GAHE in Variant 2 had a positive impact, further improving the analysed parameters:

- There were no air temperature values below 8.0 °C, a reduction of 684 h;

- Too-high air temperatures, values above 20.0 °C, occurred for 157 h (1.8% of the year), a reduction of 1294 h;

- Too-high relative air humidity, values above 70.0%, occurred for 3123 h (35.7% of the year), an increase of 360 h;

- The maximum daily fluctuation in air temperature was 3.6 °C, a reduction of 5.6 °C.

The THI values were outside the optimal range for 238 h. All recorded cases reached values above the THI > 67 range; however, no THI values below the lower value of the optimal range (THI > 48) were found.

The air temperature in the stall-box zone did not fall below the comfort values for horses throughout the year. A significant reduction in the maximum air temperature values was also achieved; exceedances occur only during 157 h, which is even less time than achieved in Variant 0. The use of a GAHE also contributed to a significant reduction in daily fluctuations in air temperature, which reached a maximum of 3.6 °C, but the mean value dropped to 0.9 °C. Such stabilisation of the extreme and average temperatures of the indoor air significantly improves the comfort of the horses. However, due to the reduction in air temperatures, the use of a GAHE resulted in an increase in both the values of relative air humidity and the total time of exceedance (an increase of another 360 h) of the comfort limit set at 70%.

3.1.3. Further Modifications to the Solution

Variant 2 made it possible to obtain conditions in the stall-box zone close to the assumed comfort adopted on the basis of the literature. It was decided to attempt to further improve the conditions obtained and to focus mainly on reducing relative air humidity while maintaining or slightly reducing the maximum temperatures.

The main assumptions were as follows, and there was an attempt to reduce,

- Air humidity by using a larger external air flow (Variant 3);

- Air humidity by using a larger GAHE air flow (Variant 4);

- The maximum air temperature by increasing the GAHE air flow (Variant 4).

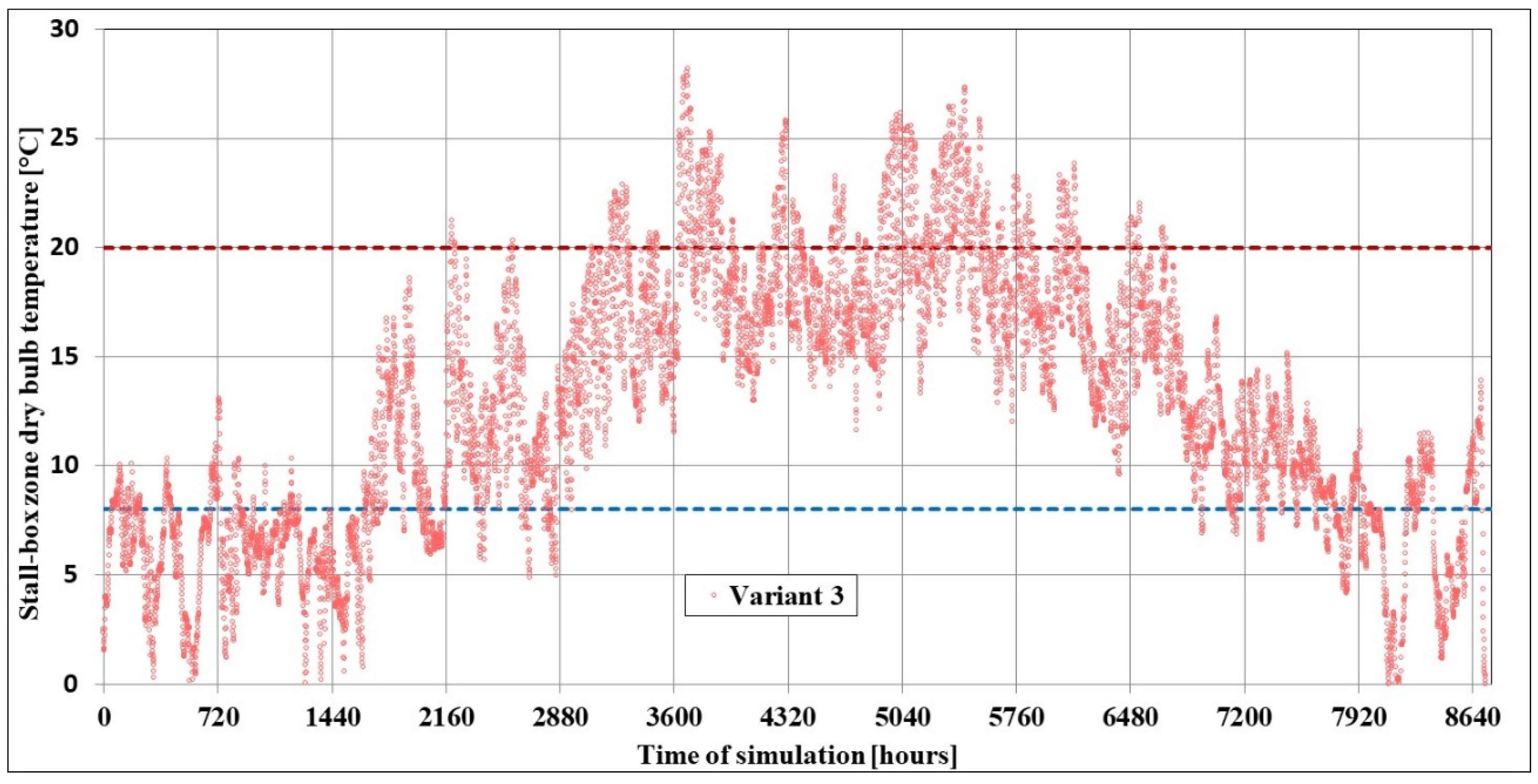

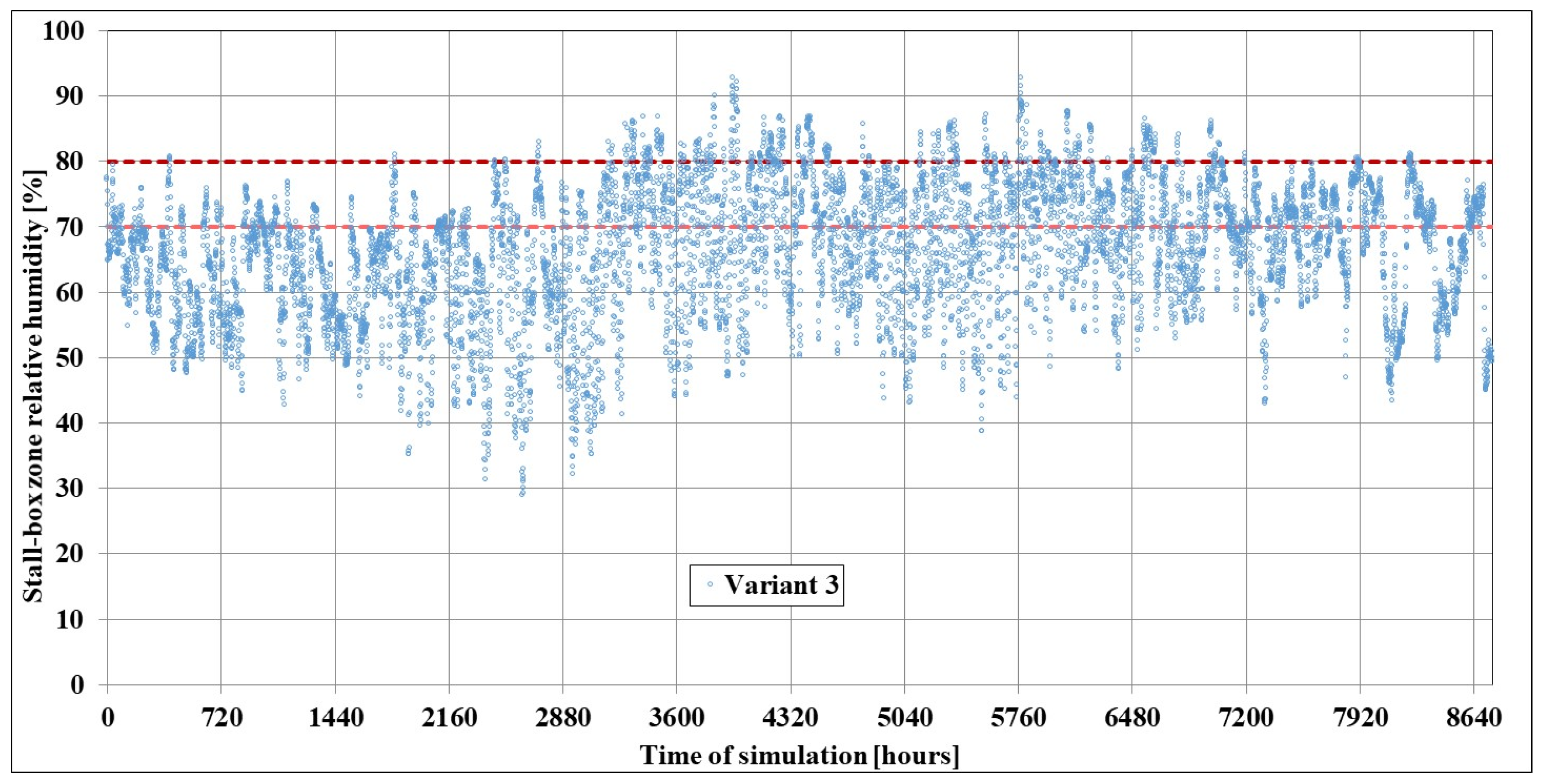

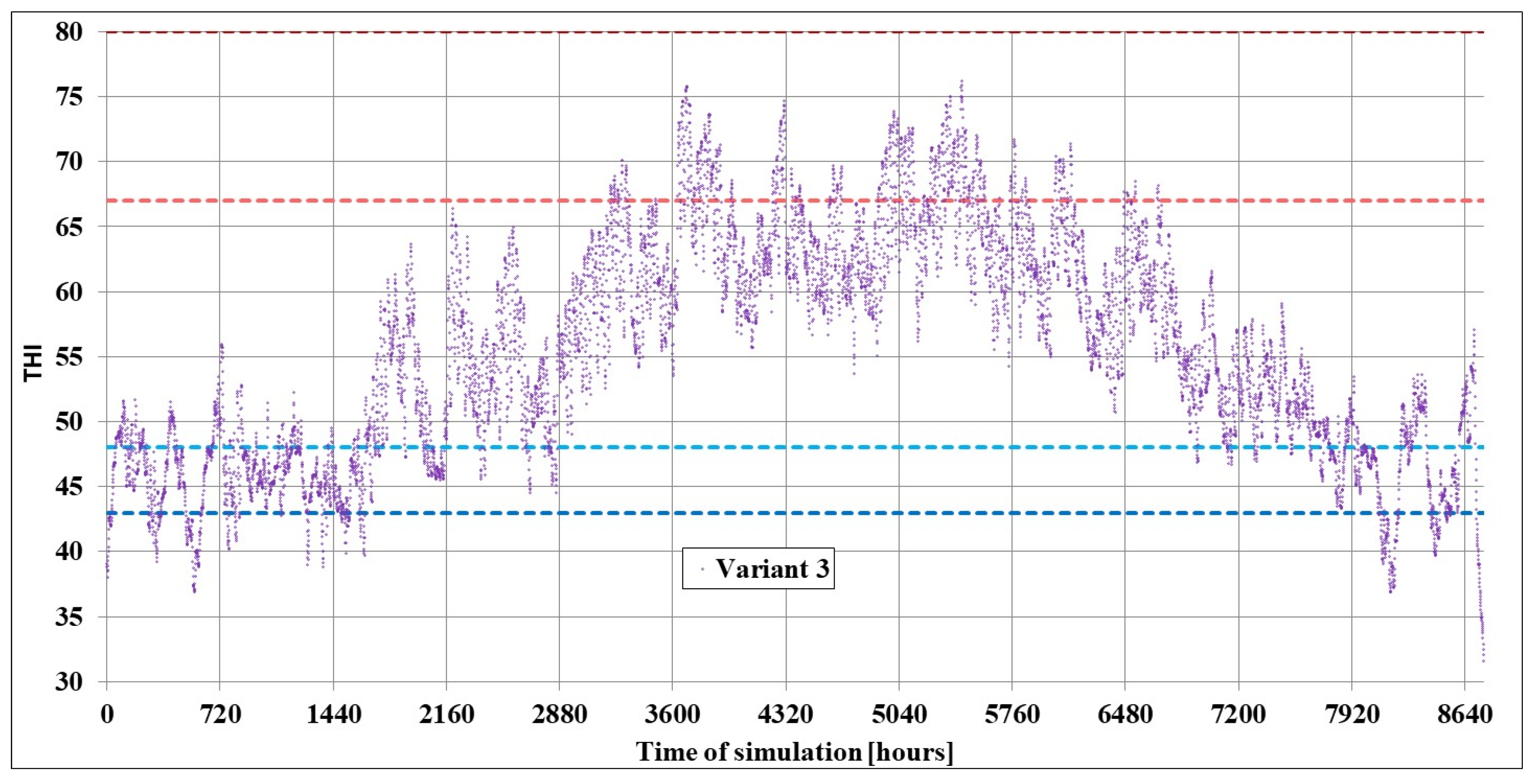

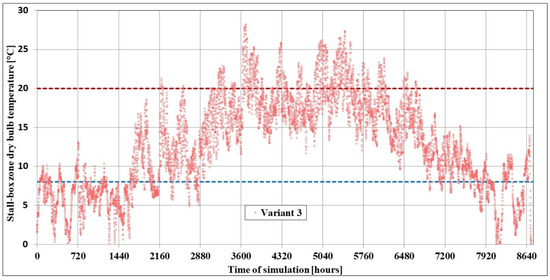

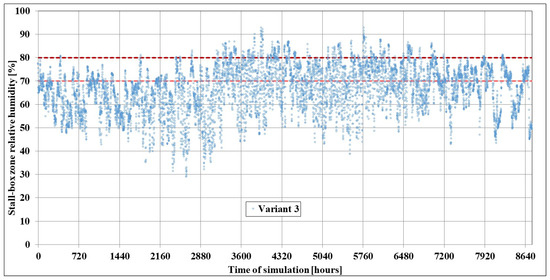

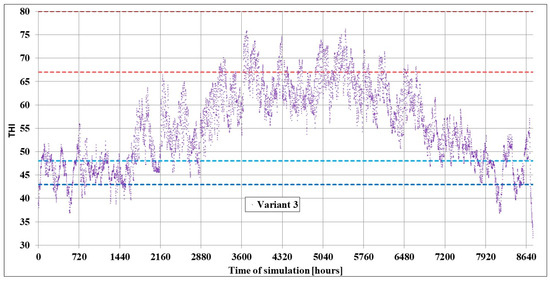

The increase in external air flow to the recommended maximum value of 8.0 ach of the mechanical ventilation system without a GAHE (Variant 3) resulted in a change in the air temperature range to min. −5.6 °C and max. 28.2 °C (Figure 19); relative humidity ranged from min. 28.9% to max. 92.8% (Figure 20); the THI ranged from 42.8 to 81.5, and its average annual value is 66.0 (Figure 21).

Figure 19.

Variation in the internalair temperature value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 3. Red and blue lines—maximum and minimum values of suggested comfort air temperatures for horses.

Figure 20.

Variation in the internalrelative humidity value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 3. Red and light red lines—maximum permissible and maximum optimal air humidity limits suggested for horses.

Figure 21.

Variation in the THI value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 3. Red, light red, light blue and blue lines—maximum permissible, maximum optimal, minimum optimal, minimum permissible THI value for horses.

Changes in the rest parameters were as follows:

- Too-low air temperatures, values below 8.0 °C, occurred for 2338 h (26.7% of the year), 2338 h more than in Variant 2;

- Too-high air temperatures, values above 20.0 °C, occurred for 993 h (11.3% of the year), 836 h more than in Variant 2;

- Too-high relative air humidity, values above 70.0%, occurred for 3467 h (39.6% of the year), 344 h more than in Variant 2;

- The maximum daily fluctuation in air temperature was 12.3 °C, 8.7 °C more than in Variant 2.

Results indicated a significant deterioration of the horse comfort parameters in the annual perspective of Variant 3. Based on more detailed analyses of the daily course of changes in air temperature and relative air humidity in Variant 3, significant daily drops in relative air humidity were observed in the warm period of the year. Drops in relative air humidity were associated with a simultaneous increase in air temperature in the stall-box zone, significantly limiting the possibility of using an increase in fresh air flow as a way to reduce relative air humidity.

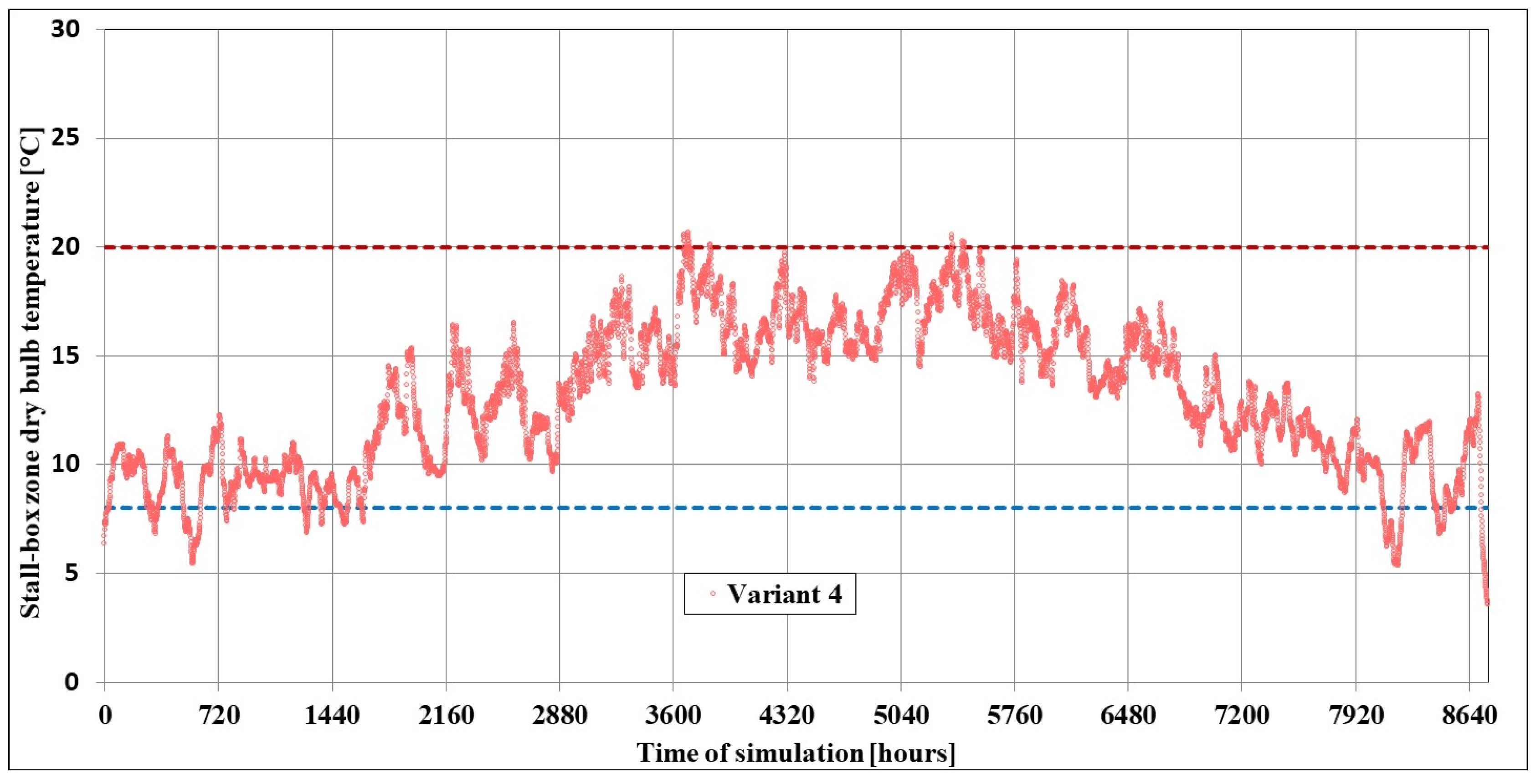

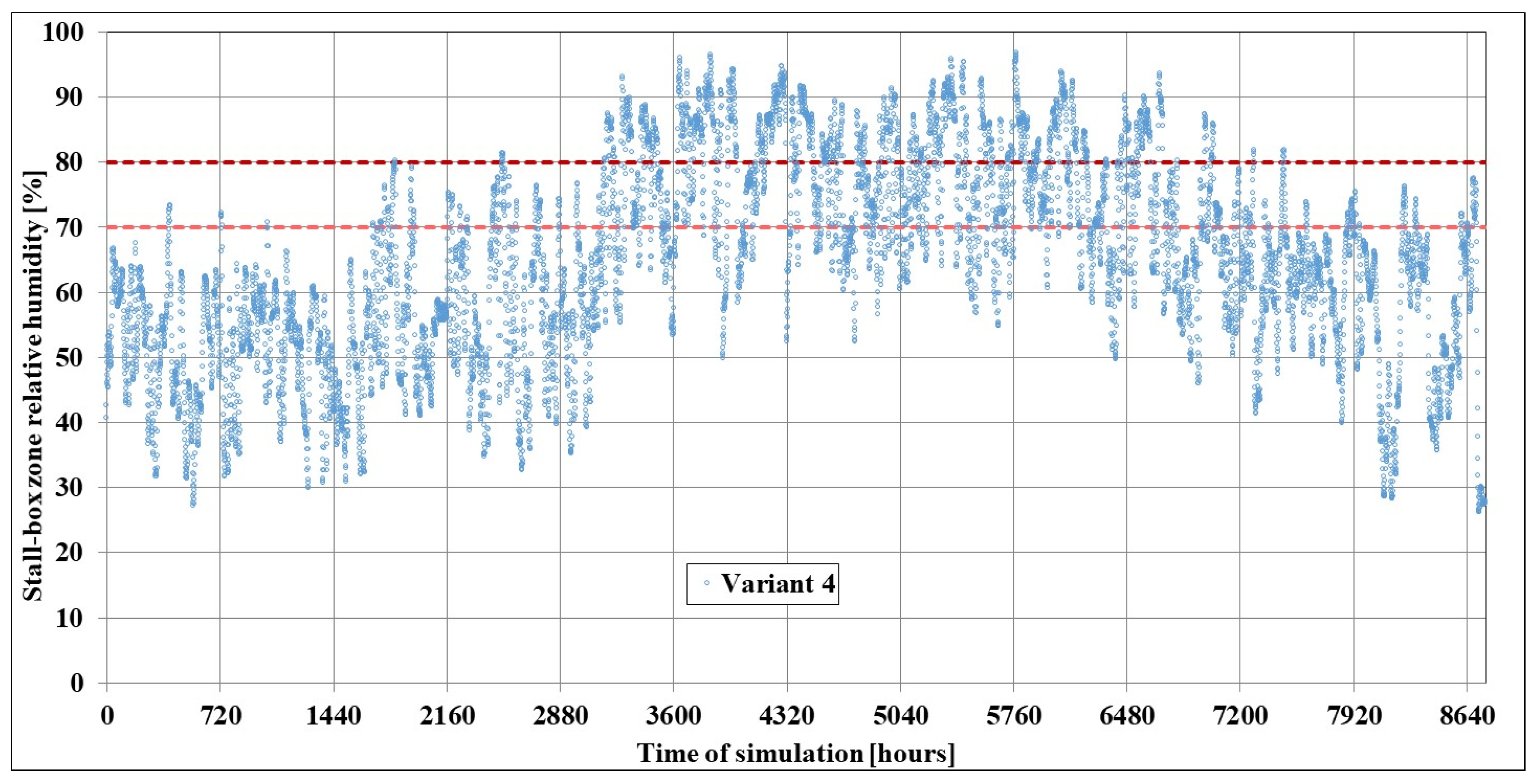

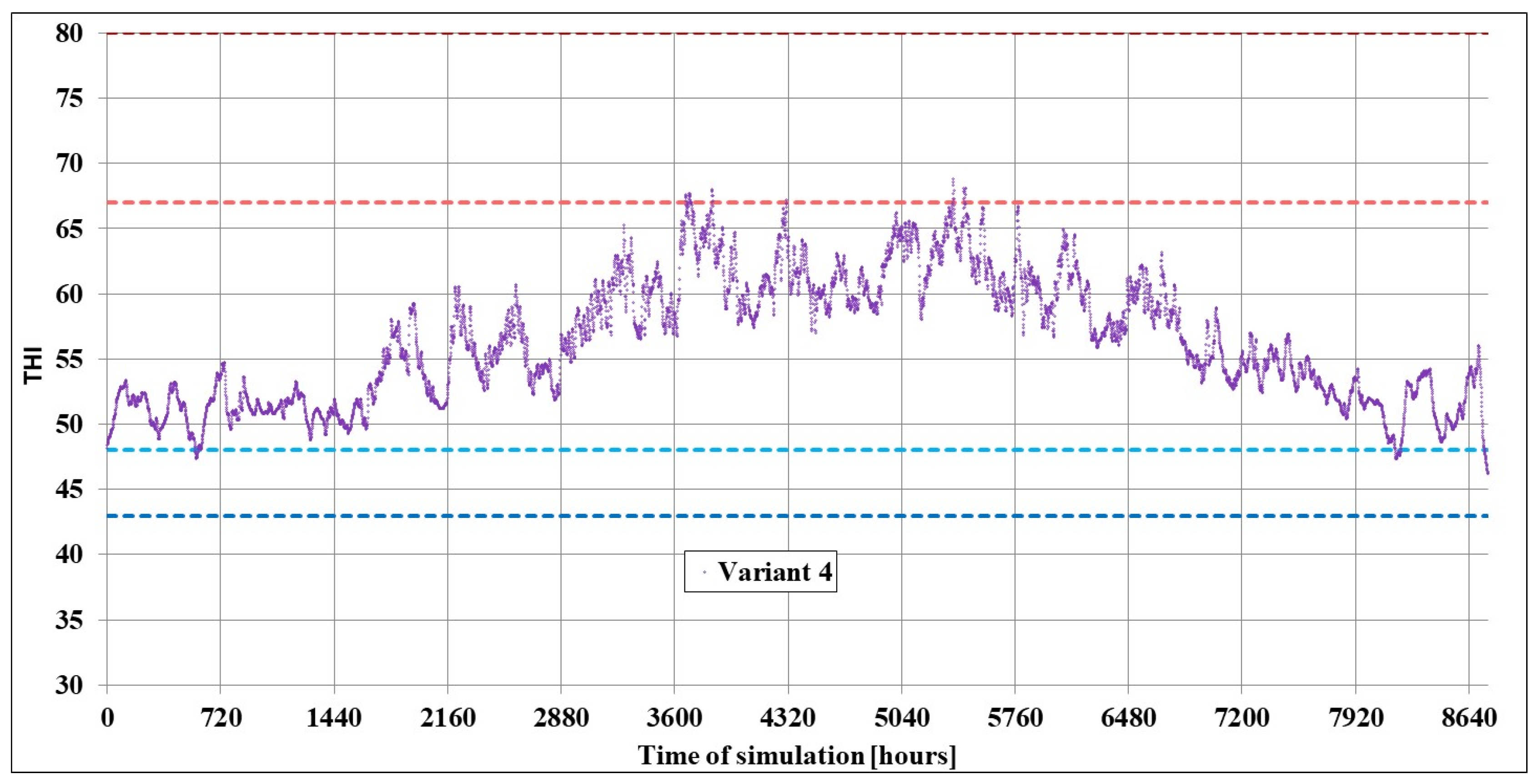

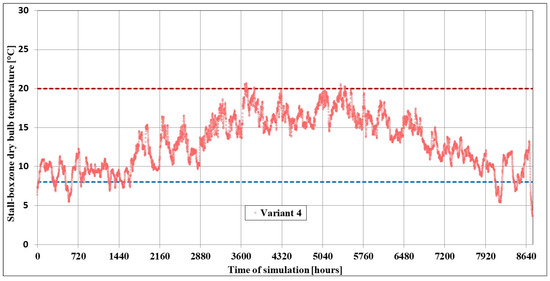

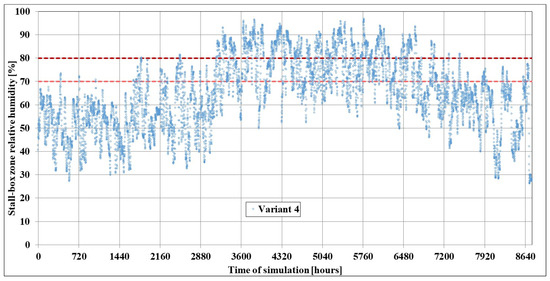

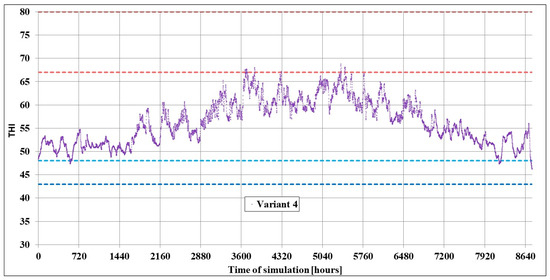

The increase in external air flow to the maximum recommended value of 8.0 ach of the mechanical ventilation system and the addition of a GAHE (Variant 4), resulted in a change in the air temperature range to min. 3.6 °C and max. 20.7 °C (Figure 22); relative humidity ranged from min. 26.2% to max. 96,8% (Figure 23); the THI ranged from 42.8 to 81.5, and its average annual value is 66.0 (Figure 24).

Figure 22.

Variation in the internalair temperature value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 4. Red and blue lines—maximum and minimum values of suggested comfort air temperatures for horses.

Figure 23.

Variation in the internalrelative humidity value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 4. Red and light red lines—maximum permissible and maximum optimal air humidity limits suggested for horses.

Figure 24.

Variation in the THI value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 4. Red, light red, light blue and blue lines—maximum permissible, maximum optimal, minimum optimal, minimum permissible THI value for horses.

Changes in the rest of the parameters were as follows:

- Too-low air temperatures, values below 8.0 °C, occurred for 530 h (6.1% of the year), 530 h more than in Variant 2;

- Too-high air temperatures, values above 20.0 °C, occurred for 31 h (0.4% of the year), 126 h less than in Variant 2;

- Too-high relative air humidity, values above 70.0%, occurred for 3286 h (37.5% of the year), 163 h more than in Variant 2;

- The maximum daily fluctuation in air temperature was 4.1 °C, 0.5 °C more than in Variant 2.

In Variant 4, the THI was outside the optimal range for 118 h throughout the year. During this period, the THI values were too high for 46 h and too low for 72 h. No THI values were found below the lower or above the upper comfort range. The use of Variant 4 contributed to a further reduction in the frequency of exceedances of maximum air temperatures, while only slightly worsening the remaining analysed parameters. The most important effect of increasing the air flow rate supplied by a GAHE was the reduction in the maximum daily air temperatures during the warm period.

3.1.4. Final Variant for the Adopted Assumptions

Selected assumptions from Variants 1, 2, and 4, those that improved the obtained results, were combined in the proposed control method of the ventilation system supported with the GAHE and were used in the Variant 5 simulation model.

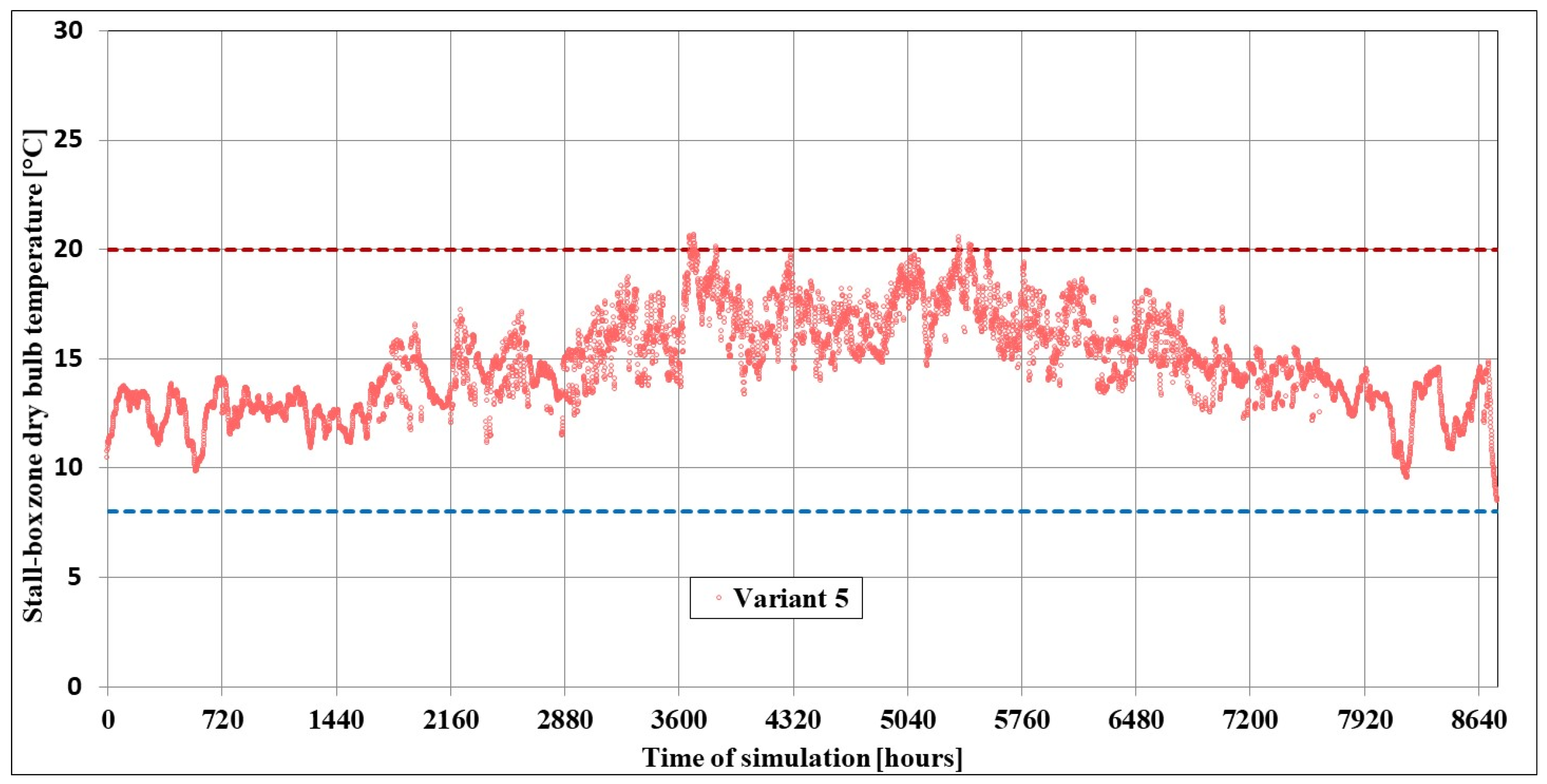

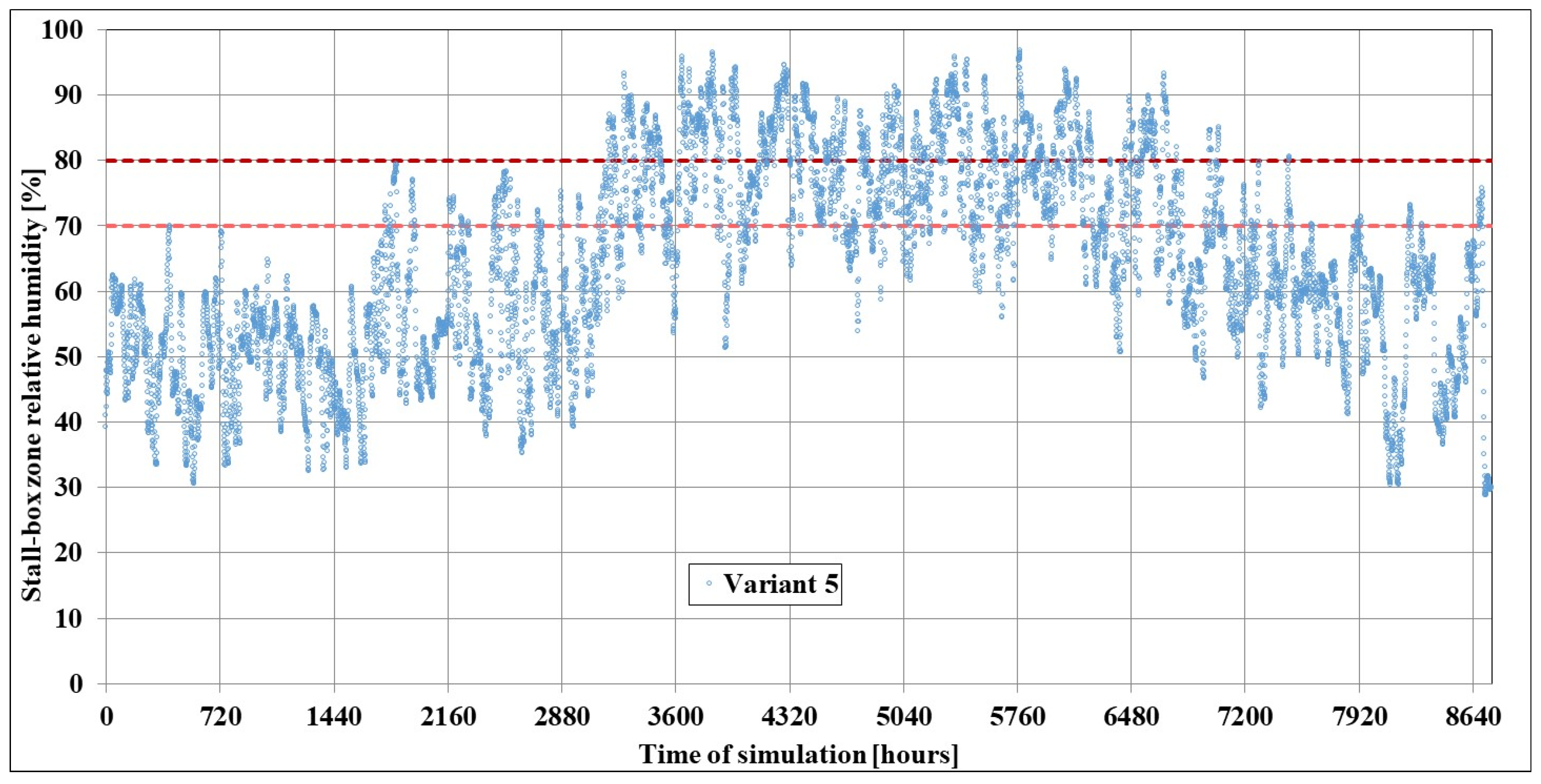

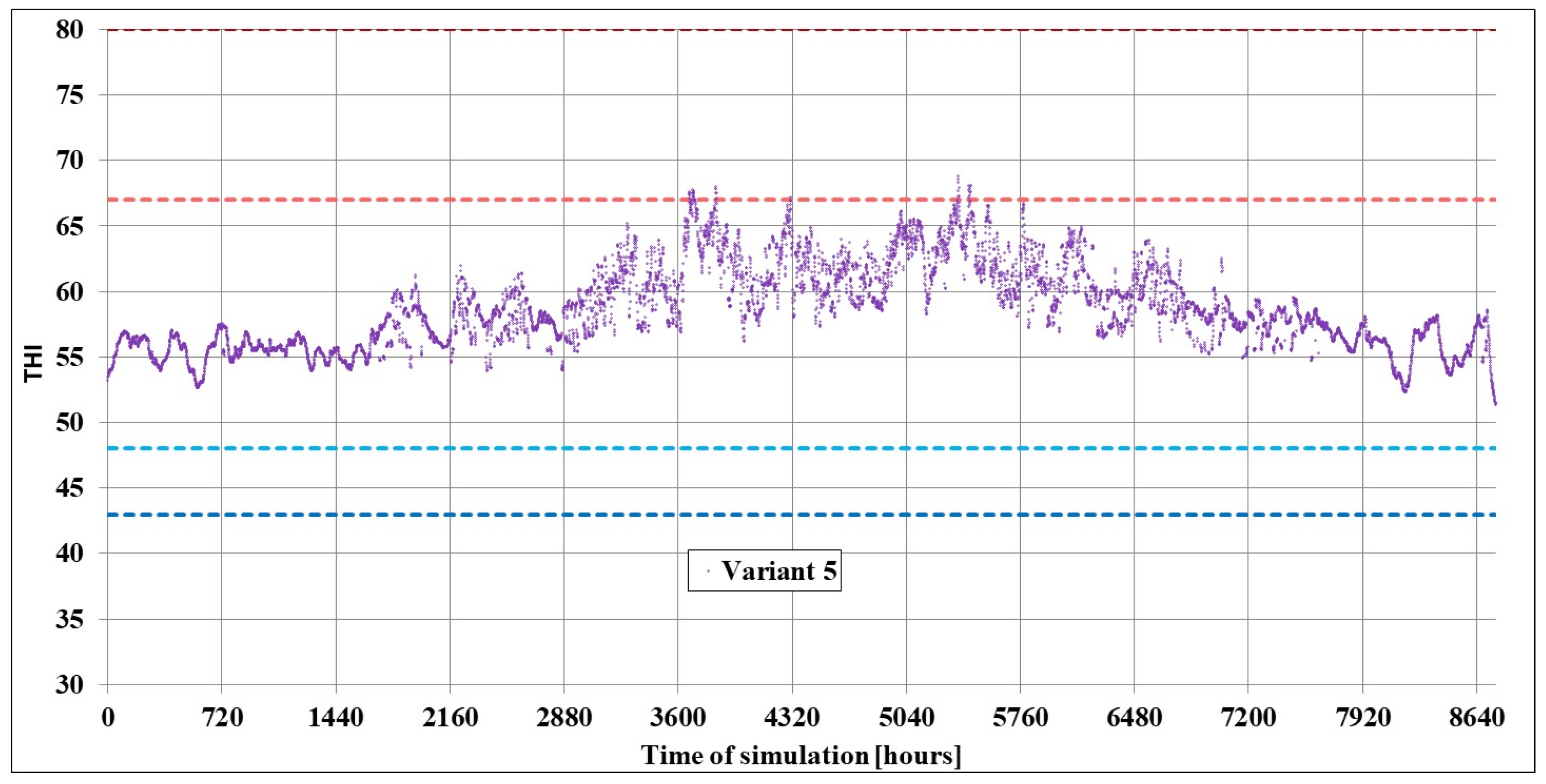

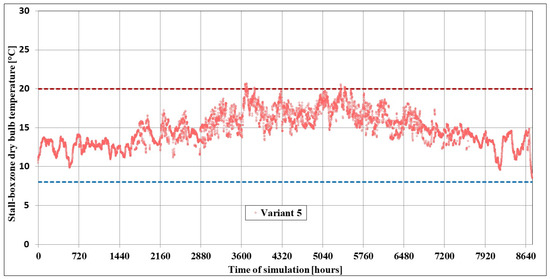

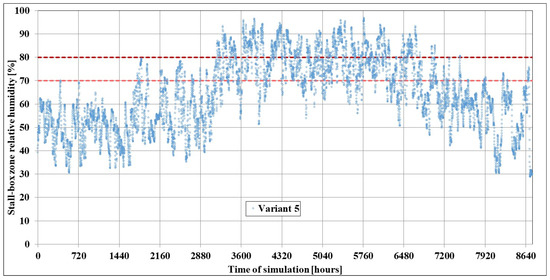

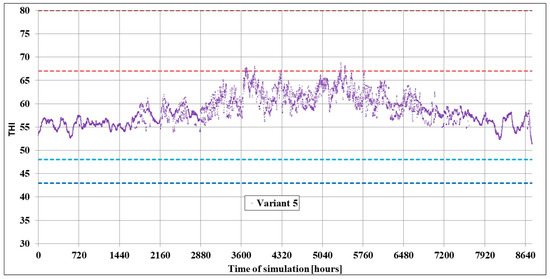

In Variant 5, the air temperature of the zone values ranges between min. 8.5 °C and max. 20.7 °C (Figure 25), relative humidity ranges between min. 28.7% and max. 96.8% (Figure 26), and the THI ranges from 42.8 to 81.5, with an average annual value of 66.0 (Figure 27).

Figure 25.

Variation in the internalair temperature value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 5. Red and blue lines—maximum and minimum values of suggested comfort air temperatures for horses.

Figure 26.

Variation in the internalrelative humidity value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 5. Red and light red lines—maximum permissible and maximum optimal air humidity limits suggested for horses.

Figure 27.

Variation in the THI value during the simulation period in the stall-box zone—Variant 5. Red, light red, light blue and blue lines—maximum permissible, maximum optimal, minimum optimal, minimum permissible THI value for horses.

The changes in the rest of the parameters were as follows:

- There were no air temperature values below 8.0 °C, the same as in Variant 2;

- Too-high air temperatures, values above 20.0 °C, occurred for 29 h (0.3% of the year), 128 h less than in Variant 2;

- Too-high relative air humidity, values above 70.0%, occurred for 3314 h (37.8% of the year), 191 h more than in Variant 2;

- The maximum daily fluctuation in air temperature was 4.4 °C, 0.8 °C more than in Variant 2.

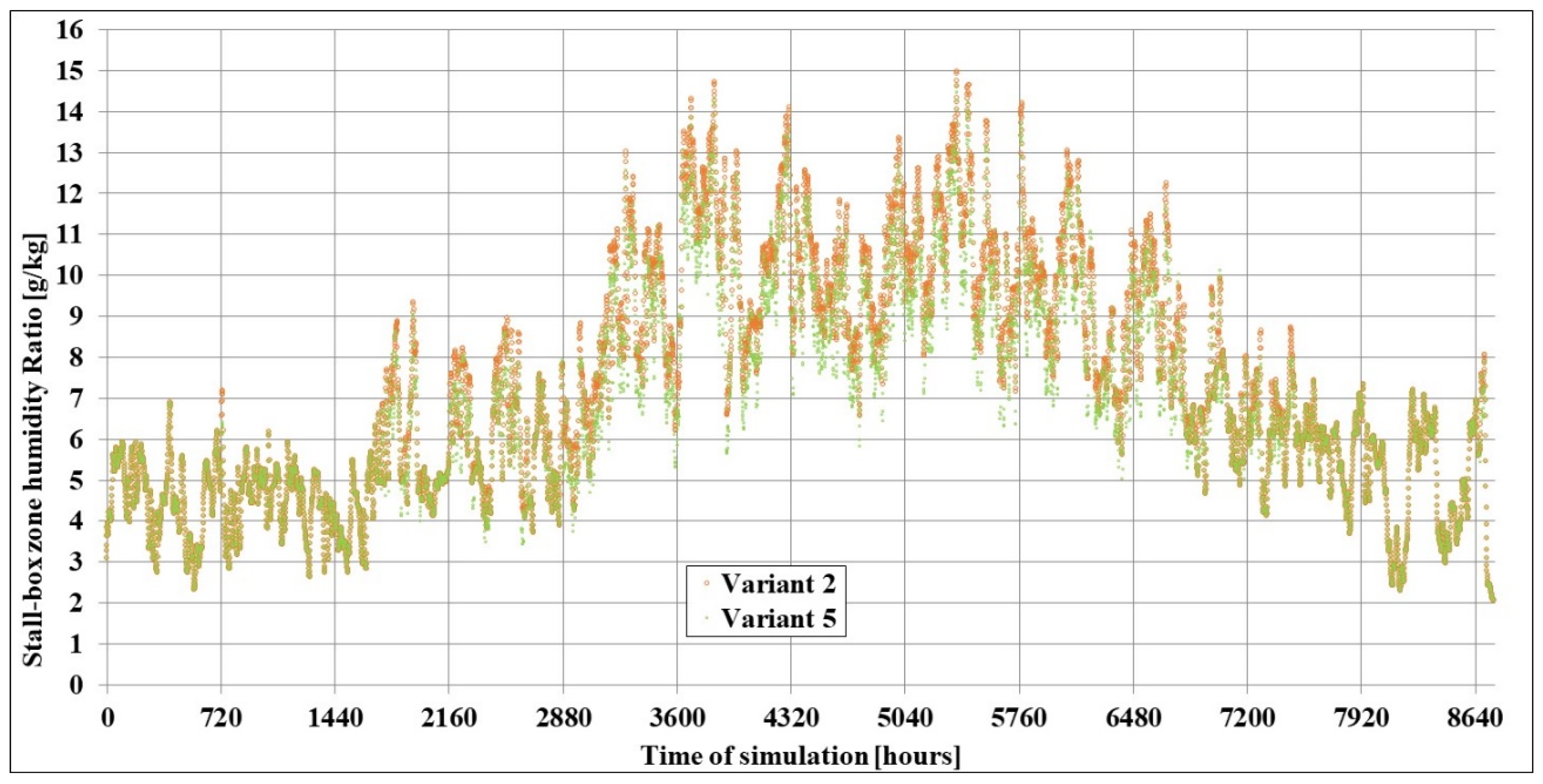

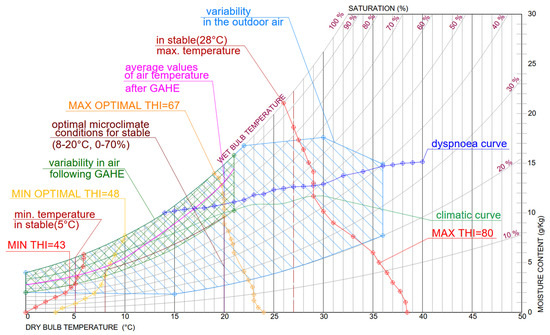

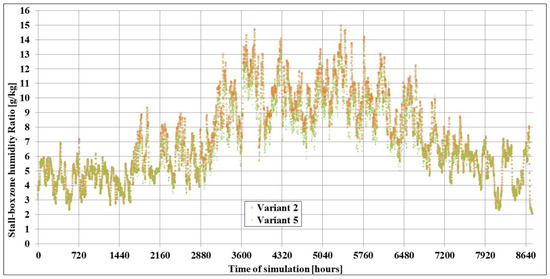

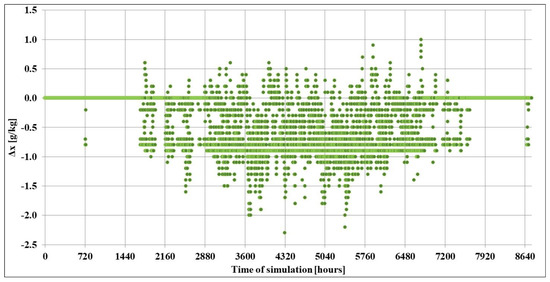

Throughout the cold period, the GAHE-supported ventilation system was maintained and provided a minimum amount of outside air—there were no differences between the results of both variants. The main changes were introduced in the warm and transition periods. The expected and confirmed effect of increasing the air flow treated and supplied to horses by a GAHE was a further decrease in maximum temperatures. However, no clear improvement in the relative humidity was achieved; some hourly values were reduced, but at the same time, some increased. These values are closely related to air temperature, the changes of which significantly hindered the demonstration of the effect of using Variant 5 on drying the air. It was decided to supplement the results with analyses of the absolute humidity values of Variants 2 and 5, and to compare their results (Figure 28). The use of Variant 5 caused a decrease in absolute air humidity in the case of 4164 h of the entire year and, at the same time, increased only in the case of 254 h (Figure 29).

Figure 28.

Comparison of the results of absolute air humidity in the stall-box zone of Variant 2 and Variant 5.

Figure 29.

Differences between the absolute air humidity values in the stall-box zone of Variant 5 and Variant 2.

There was a further decrease in the number of hours in which the THI in the rooms reached values outside the optimal range. The number of those hours dropped to 46, and all of them showed values above the upper limit of the optimal range. The THI did not reach a value above or below the thermal comfort range.

3.2. Comparison of Variants

The data in Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10 allow for direct comparison of the parameters obtained for the individual variants of solutions in the context of the number of hours of occurrence of a given air temperature, relative air humidity, THI, daily temperature, and moisture content increases in the stall-box zone. To provide a more comprehensive view, the ranges of air parameters (temperature and relative humidity) were extended to include comfortable and acceptable conditions previously described in the literature.

Table 8.

Time of occurrence of temperature and relative humidity exceedances, maximum and average daily temperature changes for all analysed variants, hours.

Table 9.

Summary of THI occurrence time for all analysed variants, hours.

Table 10.

Summary of exceedances, maximum, and average daily temperature changes for all analysed variants, hours, summary of THI occurrence time for all analysed variants, hours.

4. Discussion

Horses kept outdoors for long periods are exposed to direct contact with climatic conditions that deviate from the optimal range. In the moderate Central European climate, there are long periods of low air temperature. As determined in the analysis of Variant 0, in combination with relative air humidities, the THI (temperature and humidity index) values can drop to THI = 4. At the same time, during warm periods, the outside air temperatures exceed 30 °C for hours. Due to climate changes that have occurred in recent years, extreme air temperatures are occurring more and more frequently. At the same time, high values of relative air humidity often occur in combination with high air temperatures. As a result, horses are exposed to comfort factor conditions close to THI = 80. Another unfavourable phenomenon is the significant fluctuations in daily temperature values. The maximum observed values of daily temperature fluctuations (Table 10) reached 19 °C and relative air humidity up to 70%. This resulted in significant fluctuations in THI, exceeding ΔTHI > 30 for one day.

In the conditions established in the stall-box zone (Variant 1), a significant reduction can be observed in periods of low and uncomfortable air temperature values. Minimum THI values did not fall below THI = 40. Under closed room conditions, significant stabilisation of air temperature and humidity conditions was observed. Maximum daily differences in air temperature did not exceed Δt = 8.3 °C and humidity Δφ < 34.2%. At the same time, there was a negligible number of extremely high air temperature values in the stall-box zone. The daily fluctuations in the THI fell below ΔTHI = 11 for one day.

However, as shown in Table 8, there was a significantly higher number of cases of air temperature values exceeding the upper limit of the optimal temperature compared to the external air conditions of Variant 0.

The values of relative air humidity and moisture content in the air also increased throughout the year. In warm periods, the maximum values of the THI occurring inside the stall-box zone do not differ significantly from those occurring outside, with a reduced number of hours of occurrence of these maximum values.

The values of air temperature and humidity in the stall-box zone obtained in the conducted analysis coincide with the results obtained during the studies of other facilities [76,77,78].

A simple increase in the intensity of ventilation in the stall-box zone (Variant 3) from 4 ACH to 8 ACH did not unequivocally improve the internal conditions in the stable. The number of hours of excessively high temperatures in the warm period decreased (compared to Variant 1). However, the number of excessively high relative air humidities in warm periods increased with a reduced number of extremely high humidity cases. At the same time, conditions at low outside air temperatures worsened significantly. The number of hours with air temperatures lower than the comfort temperatures increased. There were also cases of air temperature drops in the stall-box zone below 0 °C, even reaching −5 °C. The daily stability of the thermal conditions also decreased. Maximum daily changes in air temperature reach the value of Δt = 11.2 °C, for humidity Δφ > 38%, and ΔTHI > 15. The differences are caused by the increase in the amount of untreated air flowing into the stall-box zone.

The introduction of a GAHE (Variant 2) in the ventilation system of the stable completely eliminated air temperature drops below the minimum optimum values (Table 8). The number of cases where air temperature exceeded the upper optimum limit in the stall-box zone also decreased significantly. With the volume of ventilation air reduced by half compared to Variant 3, the number of cases of exceeding the air humidity value φ < 70% increased. However, at the same time, the number of hours with air humidity exceeding the maximum allowed value of φ < 80% decreased. The thermal conditions in the stall-box zone are more stable. Daily changes in temperature (Table 10) and humidity were reduced. THI did not change by more than ΔTHI = 5 during the day. The number of hours with THI values outside the optimum range decreased to 200 (Table 9).

The analysed Variant 5 shows one of the possibilities of dynamic cooperation of a GAHE with the mechanical ventilation system, taking into account better adjustment of ventilation efficiency, parameters obtained with a GAHE, and thermal–humidity needs of the stable. Thanks to this, the inside air temperatures were maintained in a favourable range of values and even improved in some ranges. Parameter values in winter periods are slightly more favourable than in the other variants. The number of occurrences of extremely high air temperatures in the stall-box zone was reduced. The THI values also improved significantly (Table 9). As a result of the data presented in Table 8, the maximum daily changes in air temperature increased slightly, with practically unchanged daily fluctuations in relative air humidity. The daily variability in THI increased to ΔTHI = 7.

5. Conclusions

Improving the microclimate in stables has a significant impact on the health and well-being of horses. Good quality air, with a limited number of harmful gases, reduces the risk of respiratory diseases, and reducing dust and mould spores prevents allergies and chronic diseases. This is especially true for airborne diseases (for example, IAD, RAO, and obstructive pulmonary diseases). Proper ventilation ensures optimal humidity, which inhibits the growth of bacteria and fungi while reducing the risk of skin and hoof infections. Better, stable air temperature control helps to avoid overheating in warm periods and cooling in winter periods, minimising heat stress and strengthening the immunity of horses. Inappropriate internal conditions can cause colds and inflammation of muscles and joints. Stable microclimate conditions also improve the psychological comfort of horses, which translates into their appetite, condition, training efficiency, and faster regeneration after exercise. Furthermore, keeping the bedding clean and dry (e.g., with straw and sawdust) reduces dermatological problems and hoof problems.

Standard ventilation systems supply air to the stall-box zone with little or no processing, and their quality and quantity have a significant impact on the microclimate conditions in a stable. Ventilation control usually comes down to switching the air flow between summer and winter modes. Such a practice often results in inappropriate conditions inside the stable, causing discomfort to horses, especially in temperate and warm climates. However, the introduction of advanced air purification and regulation systems is associated with a significant increase in both investment and maintenance costs. The literature lacks detailed studies on the use of ground-air heat exchangers (GAHEs) to improve the microclimate in stables. Meanwhile, this solution can be an economical and effective method to improve indoor conditions without the need for large financial investments, while improving animal welfare. Taking care of the microclimate within the stable is a key element of modern horse breeding and maintenance. The climate changes observed in recent years require investments in solutions that reduce the risk of thermal stress for animals. Analysis of the use of GAHEs to ensure the parameters required for stable microclimate proves that the direction of the research undertaken is correct. Using GAHEs to prepare supply air in stable ventilation processes can translate into better general conditions for horses, less susceptibility to diseases, higher vitality, and better sports results. Investment in appropriate ventilation, temperature, and relative humidity control systems, regular cleaning, and high-quality bedding not only raises the standard of horse maintenance but also generates savings by reducing treatment costs and increasing training efficiency. GAHEs can independently provide more favourable conditions or be used for preliminary preparation of air in air-conditioning processes. It can be used in both new and existing, modernised, or renovated stables.

The implementation of the ground-air heat exchanger (GAHE) within a horse stable’s ventilation system plays a key role in significantly improving the stall-box zone’s microclimate by stabilising the two most important parameters: air temperature and humidity. This directly contributes to the health and welfare of the horses, minimising the risk of physiological stress and serious diseases. The proposed exchanger design is relatively inexpensive, and can be constructed using simple methods with locally available materials. Tests conducted on existing installations have confirmed the system’s suitability for horse stable environments. Through heat exchange with the ground, the GAHE system effectively mitigates sharp daily and seasonal fluctuations, raising the minimum air temperature during cold periods and lowering the maximum air temperature during warm periods. This stabilisation of parameters means that the horse’s body does not have to waste excessive energy on maintaining a constant body temperature, preventing both overheating and dehydration as well as hypothermia. In warmer periods, the system effectively lowers the average indoor air temperature, reducing peak heat in the stall-box zone and minimising the risk of horse overheating. Furthermore, by limiting the increase in air temperature, horses brought into rooms after exercise can return to their thermal norm faster, shortening regeneration time by up to 30–50% [79,80,81,82]. Conversely, in colder periods, the GAHE passively preheats the supply air, preventing excessive cooling of the stall-box zone while maintaining adequate airflow. Simultaneously, the system has a positive effect on the air humidity level, hindering the development of pathogens (mould, fungi, and bacteria) responsible for Recurrent Airway Obstruction (RAO) and preventing the drying of respiratory mucous membranes. The greatest benefit is the mitigation of the dangerous combination of high temperature and high humidity, which poses the most serious thermal threat. The resulting improvement in the THI (temperature–humidity index), both in summer and winter, demonstrates the creation of a stable, safe, and healthy environment that directly reduces morbidity and enhances the animals’ performance. GAHEs also allow for energy consumption optimisation: during the warm periods it is possible to reduce the amount of ventilation air without worsening conditions (which allows designing systems with smaller components and limits the size of fans, reducing electricity consumption). During the cold periods, however, thanks to passive air heating, the volume of air exchange can be increased without the risk of excessive cooling of the room, which additionally improves the quality and cleanliness of the air, positively affecting the health of animals. Consequently, the use of GAHEs in horse stable ventilation not only enhances animal welfare by stabilising the indoor microclimate but also may generate energy savings, making the future HVAC system more economical and environmentally friendly.

Deteriorating climatic conditions and the desire to improve horse breeding conditions may necessitate the use of energy-intensive cooling and heating systems in horse stables in the future. This article demonstrates that the use of GAHEs in horse stable mechanical ventilation systems allow for achieving the desired parameters without the need to invest significant sums in advanced HVAC systems, and significantly reduces the energy consumption and operating costs of these systems. The use of GAHEs in the future could significantly reduce energy consumption and, consequently, CO2 emissions from horse stables.

Improving the quality and microbiological purity of the air is crucial for preventing diseases in horses, especially those related to the respiratory system. The application of a GAHE system provides significant improvement in this area by acting as a unique biological filter within a mechanical ventilation system. By passing the outside air through layers of soil, the system effectively cleanses it of pathogenic microorganisms such as bacteria, endotoxins, and fungal and mould spores. Inhaling these pollutants is a primary cause of allergies, inflammatory airway disease (IAD), Recurrent Airway Obstruction (RAO) commonly known as heaves, and skin conditions such as hives. Simultaneously, the GAHE ensures a constant and controlled exchange of stale air for fresh air, which drastically reduces the concentration of harmful gases like ammonia, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide. These gases irritate the respiratory tract, weaken the animals’ natural immunity, and significantly increase their susceptibility to infections. By combining these two functions, the GAHE directly contributes to creating a healthier breeding environment by minimising the risk factors that lead to serious illnesses.

6. Limitations and Future Research

In the simulation model used for the GAHE heat exchanger, several simplifications were adopted, e.g., regarding the homogeneity of the bed and the surrounding ground, the simplification of hydrothermal phenomena, the idealisation of airflow through the bed, etc. These assumptions mean that the simulation results are only an approximation of the actual performance of the GAHE. However, as previous studies have shown, the obtained results accurately reflects the bed’s operation and are sufficient for engineering analysis.

Although EDSL TAS (the EnergyPlus engine) is one of the more advanced building energy simulation programs, it has certain limitations; these result primarily from the complexity and nature of computer simulations, whose accuracy is directly dependent on the quality of the input data and the computational simplifications adopted. For example, the modelling of the complex internal airflow or external-construction thermal bridges are simplified. A more detailed analysis of turbulent or complex airflow inside a zone would require the use of specialised CFD (Computational Fluid Dynamics) software, which was not necessary in the analysed case. Nevertheless, EDSL TAS is considered a reliable tool for building energy analysis, and has been validated in accordance with international standards. The software meets a number of norms, which confirms its ability to perform accurate simulations like the one presented in this article.

Furthermore, it is planned to conduct studies in real-world conditions to collect measurement data and compare them with simulation results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, M.B., W.C. and P.K.; methodology, M.B., W.C. and P.K.; software, P.K.; validation, M.B., W.C. and P.K.; formal analysis, M.B., W.C. and P.K.; investigation, M.B., W.C. and P.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B., W.C. and P.K.; writing—review and editing, M.B., W.C. and P.K.; visualisation, M.B., W.C. and P.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Harewood, E.J.; McGowan, C.M. Behavioral and physiological responses to stabling in naive horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2005, 25, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczarek, I.; Wilk, I.; Wiśniewska, A.; Kusy, R.; Cikacz, K.; Frątczak, M.; Wójcik, P. Effect of air temperature and humidity in stable on basic physiological parameters in horses. Roczniki Nauk. Pol. Tow. Zoot. 2020, 16, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, D. Horse behaviour: Evolution, domestication and feralization. In The Welfare of Horses; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, D.S.; Clarke, A. Housing, management and welfare. In The Welfare of Horses; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Minero, M.; Canali, E. Welfare issues of horses: An overview and practical recommendations. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 8, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besler, G.J. Bezprzeponowy Gruntowy Wymiennik Ciepła i Masy. Patent nr. 128261 PRL, 28 June 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Besler, M. Badania Efektywności Wykorzystania Energii Gruntu w Inżynierii Środowiska. Praca Doktorska, Politechniki Wrocławskiej, Wrocław, Poland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Cepiński, W. Efektywność Pozyskiwania Energii Naturalnej. Praca Doktorska, Efektywność Pozyskiwania Energii Naturalnej, Wrocław, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Elfman, L.; Riihimäki, M.; Pringle, J.; Wålinder, R. Influence of horse stable environment on human airways. J. Occup. Med. Toxicol. 2009, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardoni, S.; Mancianti, F.; Sgorbini, M.; Taccini, F.; Corazza, M. Identification and seasonal distribution of airborne fungi in three horse stables in Italy. Mycopathologia 2005, 160, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz, C.; Maleh, S. Zivilisationrankheiten des Pferdes—Ganzheitliche Behandlung Chronischer Krankheiten; Sonntag Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, H.; Coenen, M.; Vervuert, J. Pferdefütterung; Enke Verlag: Stuttgart, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kwiatkowska-Stenzel, A.; Sowińska, J.; Witkowska, D. The Effect of Different Bedding Materials Used in Stable on Horses Behavior. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2016, 42, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janczarek, I.; Wilk, I.; Zalewska, E.; Bocian, K. Correlations between the behavior of recreational horses, the physiological parameters and summer atmospheric conditions. Anim. Sci. J. 2015, 86, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, D.R.; Davis, R.E.; McConaghy, F.F. Thermoregulation in the horse in response to exercise. Br. Vet. J. 1994, 150, 219–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadi, S.; Wouters, I.M.; Houben, R.; Jamshidifard, A.; Eerdenburg, F.; Heederik, D.J.J. Exposure to inhalable dust, endotoxins, β(1→3)-glucans, and airborne microorganisms in horse stables. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2009, 53, 595–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, L.M.; Crane, J.; Fitzharris, P.; Bates, M.N. Occupational respiratory health of New Zealand horse trainers. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2007, 80, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wålinder, R.; Riihimäki, M.; Bohlin, S.; Hogstedt, C.; Nordquist, T.; Raine, A.; Pringle, J.; Elfman, L. Installation of mechanical ventilation in a horse stable: Effects on air quality and human and equine airways. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2011, 16, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elfman, L.; Wålinder, R.; Riihimäki, M.; Pringle, J. Air Quality in Horse Stables. In Chemistry, Emission Control, Radioactive Pollution and Indoor Air Quality; InTech: Houston, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A.F. A review of environmental and host factors in relation to equine respiratory disease. Equine Vet. J. 1987, 19, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullone, M.; Murcia, R.Y.; Lavoie, J.P. Environmental heat and airborne pollen concentration are associated with increased asthma severity in horses. Equine Vet. J. 2016, 48, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woods, P.S.; Robinson, N.E.; Swanson, M.C.; Reed, C.E.; Broadstone, R.V.; Derksen, F.J. Airborne dust and aeroallergen concentration in a horse stable under two different management systems. Equine Vet. J. 1993, 25, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pirie, R.S.; Collie, D.D.S.; Dixon, P.M.; McGorum, B.C. Inhaled endotoxin and organic dust particulates have synergistic proinflammatory effects in equine heaves (organic dust-induced asthma). Clin. Exp. Allergy 2003, 33, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łojek, J. Dobrostan i utrzymanie koni. In Hodowla i Użytkowanie Koni; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warsaw, Poland, 2013; Volume T. II. [Google Scholar]

- Bombik, T.; Górski, K.; Bombik, E.; Malec, B. Evaluation of selected Parameters of Horse stabling Environment in Box-Stal Stables. Acta Sci. Pol. Zootech. 2009, 8, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kaletowski, K. Budownictwo dla koni—Małe stajnie. Koń Polski 1997, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Jodkowska, E. Wskazania przed rozpoczęciem budowy ośrodka hippicznego. Przegl. Hodowlany 2002, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedorowicz, G.; Łojek, J.; Clausen, E. Budowa nowych stajni i modernizacja budynków inwentarskich dla koni. Przegl. Hodowlany 2004, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Minister Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi. Rozporządzenie Ministra Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi z Dnia 28 Czerwca 2010 r w Sprawie Minimalnych Warunków Utrzymywania Gatunków Zwierząt Gospodarskich Innych Niż te dla Których Normy Ochrony Zostały Określone w Przepisach Unii Europejskiej; Dziennik Ustaw: Warsaw, Poland, 2010; nr 116, poz. 778. [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, L. Mikroklimat W Budynkach Inwentarskich; PWN: Warsaw, Poland, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- McGreevy, P.D.; Cripps, P.J.; French, N.P.; Green, L.E.; Nicol, C.J. Management factors associated with stereotypic and redirected behaviour in the thoroughbred horse. Equine Vet. J. 1995, 27, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K. Thermoneutral zone and critical temperatures of horses. J. Therm. Biol. 1998, 23, 59–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombik, E.; Bombik, T.; Frankowska, A. Evaluation of selected Parameters of Horse Stabling Environment in Box-Stal Stables. Acta Sci. Pol. Zootech. 2011, 10, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Noordhuizen, J.; Noordhuizen, T. Heat Stress in (Sport) Horses: (I) Occurrence, Signs & Diagnosis, (II) Practical Management and Preventive Measures. J. Dairy Vet. Sci. 2017, 2, 555597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polski Związek Hodowców Koni. Sprawozdanie z Działalności Polskiego Związku Hodowców Koni w Latach 2020–2023; Polski Związek Hodowców Koni (PZHK): Warsaw, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]