1. Introduction

Modern energy is faced with the need to solve two interrelated global problems: the depletion of traditional fossil fuels and the increasing anthropogenic impact on the environment. In this context, the development and implementation of renewable energy technologies, among which biomass occupies one of the key places, is of particular relevance. The energy potential of biomass is due not only to its renewability, but also to significant reserves: according to the latest estimates, the annual renewable plant resources on the planet amount to about 1830–1836 billion tons, which in oil equivalent corresponds to about 640 billion tons [

1,

2]. At the same time, the energy value of various types of biomass varies in the range of 10–20 MJ/kg, which, although inferior to traditional hydrocarbon fuels, significantly exceeds other renewable sources, such as solar or wind energy. The most important advantage of biomass as an energy resource is its stable availability and storage ability, which distinguishes it from intermittent renewable energy sources. The importance of bioenergy development is emphasized in key strategic documents. Specifically, Directive (EU) 2023/2413 (RED III) sets a mandatory target for the European Union to achieve a 42.5% (with a target of 45%) share of renewable energy in total energy consumption by 2030 [

3]. Achieving such ambitious targets is impossible without the widespread adoption of biomass, including in the form of composite fuels for co-firing with fossil resources, which reduces emissions with minimal modernization of existing energy infrastructure [

4].

Comprehensive processing of forestry and agricultural waste is of particular importance, allowing for the simultaneous solution of energy problems and problems of organic waste disposal [

5,

6]. In particular, the technology of co-firing coal and biomass has already proven its effectiveness in European countries, where it is successfully used at a number of energy facilities [

7,

8]. The main advantage of this approach is that it does not require a radical modernization of existing thermal power plant equipment, while ensuring an increase in process efficiency of up to 35–40% and a significant reduction in greenhouse gas emissions [

9].

The mechanisms of interaction between coal and biomass during co-combustion are of considerable scientific interest. Previous studies have shown that mechanical activation of fuel compositions by joint grinding of the components leads to the formation of paramagnetic centers on the surface of particles, which significantly increases their reactivity [

10,

11,

12]. A particularly pronounced synergistic effect is observed when using low-reactivity coals, such as brown coals, where the addition of even small amounts of biomass can significantly improve the ignition and combustion characteristics [

13].

However, co-firing coal and biomass also presents several challenges, including differences in fuel properties, such as volatile content, moisture, and ash composition, which can lead to issues in ignition, combustion stability, and slagging [

14,

15,

16]. Moreover, the milling and feeding systems designed for coal may not be suitable for biomass, and the higher chlorine content in some biomass types can cause corrosion. These technical challenges require careful optimization of fuel blends and processing methods.

In parallel with co-combustion technologies, high-temperature plasma gasification methods are actively developing, allowing the conversion of carbon-containing materials into valuable synthesis gas (a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide) with the simultaneous formation of inert slag. This approach has a number of significant advantages, including a high degree of raw material conversion (up to 95–98%), minimal emissions of harmful substances and the ability to process a wide range of renewable resources [

17,

18]. Gasification processes occurring at temperatures of 1200–1600 °C ensure almost complete decomposition of organic compounds, which makes this method especially promising for the disposal of low-grade fuels and various types of organic waste [

19].

Despite a significant amount of research devoted to the co-combustion and thermochemical conversion of coal and biomass [

7,

8,

9,

13], the key aspects determining the synergistic effects in composite fuels remain poorly understood. In particular, there is a lack of quantitative data on the kinetic parameters of composite pyrolysis, and there is a lack of direct experimental evidence linking mechanical activation with the evolution of active sites on the particle surface and their influence on the subsequent stages of ignition and combustion. Most existing studies focus on highly reactive coals (e.g., brown coals), while systems based on low-reactivity anthracite are poorly understood. The present study fills these gaps through an integrated approach combining thermogravimetric analysis with kinetic modeling, the study of ignition and flare combustion processes, and plasma gasification. The main innovative component of this work lies in establishing a quantitative relationship between mechanical activation of the fuel, the formation of active paramagnetic centers, non-additive behavior during thermal decomposition, and the uniformity of gas evolution during gasification of hard-to-burn anthracite [

20]. This allows us to move beyond a simple description of the observed effects to elucidating their physicochemical nature.

Particular attention in the work was paid to studying the effect of mechanical activation on the reactivity of fuel materials. As shown by previous studies, newly formed active centers on the surface of particles that arise during intensive milling have a limited lifetime, which requires prompt use of the processed material [

21]. This factor is of fundamental importance for the practical application of composite fuels, since it determines the optimal time frame between the activation process and the direct use of the material. Thus, the conducted comprehensive study of the processes of thermal processing of composite fuels based on coal and biomass makes a significant contribution both to the development of fundamental knowledge in the field of combustion and gasification chemistry and to solving applied energy problems.

2. Experimental Setup and Measurement Methods

The study employed anthracite coal from the Kuznetsk Basin (Russia), exhibiting typical properties of low-volatile fuels with less than 8% volatile matter and more than 85% fixed carbon content. The biomass component consisted of pine sawdust sourced from woodworking industry waste in Novosibirsk, Russia. Proximate analysis revealed fundamental differences between the materials: the anthracite contained 2.1% moisture, 8.5% ash, 7.3% volatile matter, and 82.1% fixed carbon, while the pine sawdust showed higher volatile content 75.4% with 10.2% moisture, 0.8% ash, and 13.6% fixed carbon. Ultimate analysis further highlighted the contrast in composition, with the anthracite dominated by carbon 89.2% and the sawdust richer in oxygen 45.2%.

The study examined two types of fuels: mechanical blends and composite fuels. The preparation of mechanical blends involved separately grinding anthracite and pine sawdust, followed by mixing them in specified proportions. To produce composite fuels, the same starting components in similar ratios were subjected to combined mechanical activation in a mill. The key difference in this approach is that the intensive co-grinding process creates new shared particle surfaces and strong interfacial bonds between the coal and biomass. This allows for the production of not just a blend, but a homogeneous composite with unique properties.

As part of this study, complex experiments were conducted to study the processes of thermal decomposition, ignition and combustion of composite fuels, consisting of traditional fossil fuel and biomass, as well as their gasification in plasma installations. The methodological part of the study included a set of modern experimental approaches, such as thermogravimetric analysis, flash time determination in a fan furnace, flare combustion of fuel and gasification. The objects of study were composite materials based on anthracite (as a representative of low-reaction coals) and pine sawdust, chosen due to their high specific heat of combustion (21.1 MJ/kg) and widespread occurrence in woodworking waste [

22]. To activate the fuel compositions, a DESI-11 impact-centrifugal grinder was used, providing a high degree of particle dispersion and the formation of reactive surfaces. The fuel components were mixed in various proportions, as shown in

Table 1. The choice of component ratios (70/30, 50/50, 30/70) was based on the desire to cover a wide range from biomass-dominated fuels to coal-dominated fuels. This allows for a systematic study of the transition from a combustion regime controlled by the release of volatiles from the biomass to one controlled by the combustion of coal coke residue. The 50/50 ratio is of particular interest as the point of potential maximum synergistic effect, where the interaction of the components can manifest itself most clearly. Further research is planned to optimize the composition using experimental design methods.

All fuel samples for a given ratio were prepared by maintaining a constant total mass for comparative purposes. The components for both mixtures and composites were dry-mixed by mass according to the ratios specified in

Table 1.

Synchronous thermal analysis (TGA/DTG) allowed a detailed study of the kinetics of thermal decomposition of samples under controlled conditions. The study of the ignition processes of dust suspensions was carried out in a vertical tubular furnace simulating the conditions of real power plants. To study the combustion characteristics, a two-stage burner with tangential fuel supply was used, which made it possible to evaluate the effect of the composite composition on the combustion process under conditions close to industrial ones.

In parallel with the combustion process studies, experiments were conducted on plasma gasification of both individual components (sawdust, coal) and their mechanical mixtures and composite compositions. Analysis of gasification products with determination of concentrations of hydrogen, carbon monoxide, methane and nitrogen oxides allowed for to identification of key patterns of influence of fuel composition and degree of its mechanical activation on the yield and quality of synthesis gas. The obtained results are of great importance for the development of technologies for the joint processing of coal and biomass.

2.1. Thermal Decomposition Process Study

The thermal decomposition process was investigated employing a synchronous thermal analyzer, the STA 449F1 Jupiter

® (NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany), in strict compliance with the manufacturer’s protocol and the requirements of ISO 11357-1 [

23] and DIN 51007 [

24] standards. Prior to the experiments, the instrument underwent temperature and sensitivity calibration with a set of high-purity reference materials, including In, Sn, Bi, Zn, Al, Ag, and Au. This calibration was performed under conditions identical to those planned for the actual measurements, encompassing heating rate, atmospheric environment, sample holder type, crucible material, and operational temperature range.

The experiments utilized 10 mg samples heated from 30 to 1000 °C within a synthetic air atmosphere, composed of 80% argon and 20% oxygen, flowing at a rate of 10 mL/min. The heating process was conducted at a constant rate of 10 °C/min using open corundum crucibles. The resulting data were processed with the Proteus analysis software (

https://analyzing-testing.netzsch.com/en/products/software/proteus (accessed on 15 July 2025).) and the NETZSCH Thermokinetics 3.1 package. The interpretation of the data relies on several thermal analysis curves. The Thermogravimetric (TG) curve maps the change in sample mass against temperature. Its derivative, the Differential Thermogravimetric (DTG) curve, plots the rate of mass loss, which is instrumental in resolving overlapping stages of decomposition and identifying the temperature of the most rapid mass change. Simultaneously, the Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) curve charts the heat flow as a function of temperature, allowing for the evaluation of endothermic and exothermic effects taking place in the sample during heating.

2.2. Study of the Process of Self-Ignition of Samples in a Vertical Tubular Furnace

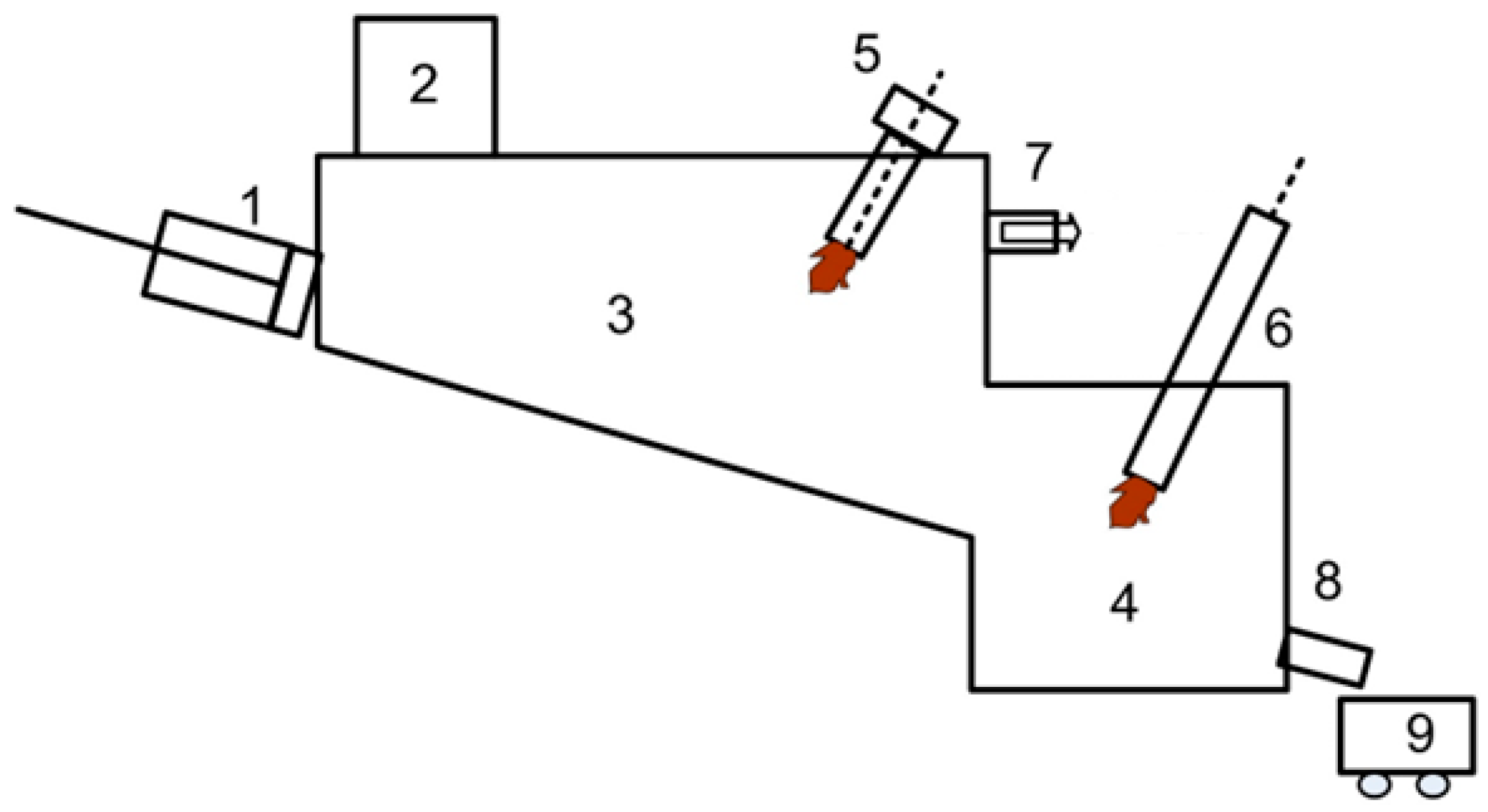

The experimental setup for analyzing the flash delay of a sample injected via compressed air into a heated environment utilized a vertical tubular furnace, shown in

Figure 1. This apparatus consisted of a one-meter-long, thermally insulated steel pipe with an internal diameter of 0.4 m. The pipe was electrically heated by a low-voltage transformer system. An array of photodiodes and thermocouples was positioned along the combustion chamber at 0.1 m intervals within specially designed ports to detect the flash and monitor temperature, respectively. To maintain a stable temperature at the reactor’s inlet and to eliminate unwanted convective currents and combustion residues, a slight vacuum of approximately 5 mm of water column was created using an air blower and an ejector. The airflow rate was regulated based on the furnace temperature to ensure thermal stability throughout the entire chamber. The injection mechanism comprised a magnetic valve and a 45 × 10

−8 m

3 chamber. A powder fuel feeder, located above this valve, was loaded with samples ranging from 0.1 to 1 g. The procedure involved pressurizing the chamber with air, which then triggered the injection of the dust into the reactor.

The ignition monitoring system is built around a set of optical sensors, which are supported by excitation and signal processing circuits, a data acquisition unit, and dedicated software for analyzing the signals. A key component is the flame detector, which employs a photodiode equipped with a lens that focuses light from the flame onto a dedicated window, operating within a spectral range of 400 to 1100 nm. This configuration enables the determination of the minimum dust ignition temperature and the analysis of ignition delay relative to reactor temperature. The signals from the photodiodes and the activation pulse for the magnetic valve are logged using an Lcard ADC (Moscow, Russia). This setup directly measures the time interval from the valve’s opening to the first detected signal from a photodiode.

2.3. Flare Combustion Study

The flare combustion study was conducted on a horizontal burner device. The setup is a chamber furnace with a cooling circuit, in which a vortex burner with three stages is installed. The first stage of the burner is designed to ignite highly reactive initiation fuel, the second stage is designed for solid pulverized fuel of fine fraction composition, and the third stage is designed to ignite large particles of solid fuel.

Ignition of highly reactive fuel is carried out using an ignition device, which is built into the diffuser at the end of the burner device. Thermocouples located in characteristic places are used to obtain temperature readings of the setup, shown in

Figure 2.

2.4. Gasification of Composite Fuel

The work investigated the gasification of various samples of organic fuel (components, mixtures, and composites), according to

Table 1. The prepared fuel samples were packaged in boxes of 0.75 kg. The gasification technology is based on high-temperature (1200–1600 °C) plasma action and complete decomposition of high-molecular organic compounds and gasification of utilized products using arc plasma to simple chemical compounds to obtain a useful product—synthesis gas, which is a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide, as well as inert slag. The basic diagram of the experimental plasma-thermal electric furnace with a capacity of up to 20 kg/h is shown in

Figure 3.

The plasma electric furnace serves to evaluate the technology for high-temperature plasma gasification of diverse renewable carbon-based fuels and waste materials, including substances like sawdust, textiles, polyethylene, and medical waste. Fuel is introduced into the furnace’s workspace through a loading mechanism (2), pre-packaged in containers measuring 200 × 200 × 250 mm. This loading device features a lock chamber designed to mitigate the escape of flue gases into the atmosphere during overpressure conditions and to prevent the infiltration of ambient air into the furnace chamber when a vacuum is present.

A hydraulic pusher (1), which is connected to an oil station and a control unit, advances the packaged fuel along the inclined hearth within the gasification zone (3). Initial heating of the lining and the gasification area is achieved using a 42 kW gas burner (5) alongside a 50 kW plasma torch (6). Once operational, the target gasification temperature of 1200 °C is sustained solely by the plasma torch, which generates an air plasma with an average mass temperature of 4000 °K.

The synthesis gas, or fuel gas, produced in the gasification zone is then directed to a centrifugal bubbling apparatus (CBA) to quench the plasma-chemical reactions and remove particulate matter. Meanwhile, the residual ash, which contains particles of unburned material and carbon, moves into a dedicated combustion zone (4). There, a plasma jet facilitates the complete combustion of carbon and its fusion into an inert slag.

Following treatment in the CBA, the fuel gas proceeds to an afterburner chamber, where it is fully oxidized to CO2. The temperature of the resulting flue gas at the furnace outlet is monitored by a type S (Pt-Pt/Rh) thermocouple, capable of measuring between 500 and 1300 °C, and up to 1500 °C for short durations. Furthermore, the concentration of key gases (H2, CO, CO2, N2, O2, CH4) at the outlet is analyzed by a multi-component gas analyzer integrated into the equipment system.

3. Results and Discussion

Experimental investigations into the processes of thermal-oxidative destruction yielded thermal decomposition curves, which illustrate the relationship between temperature and the sample’s mass, its mass loss rate, and associated energy release.

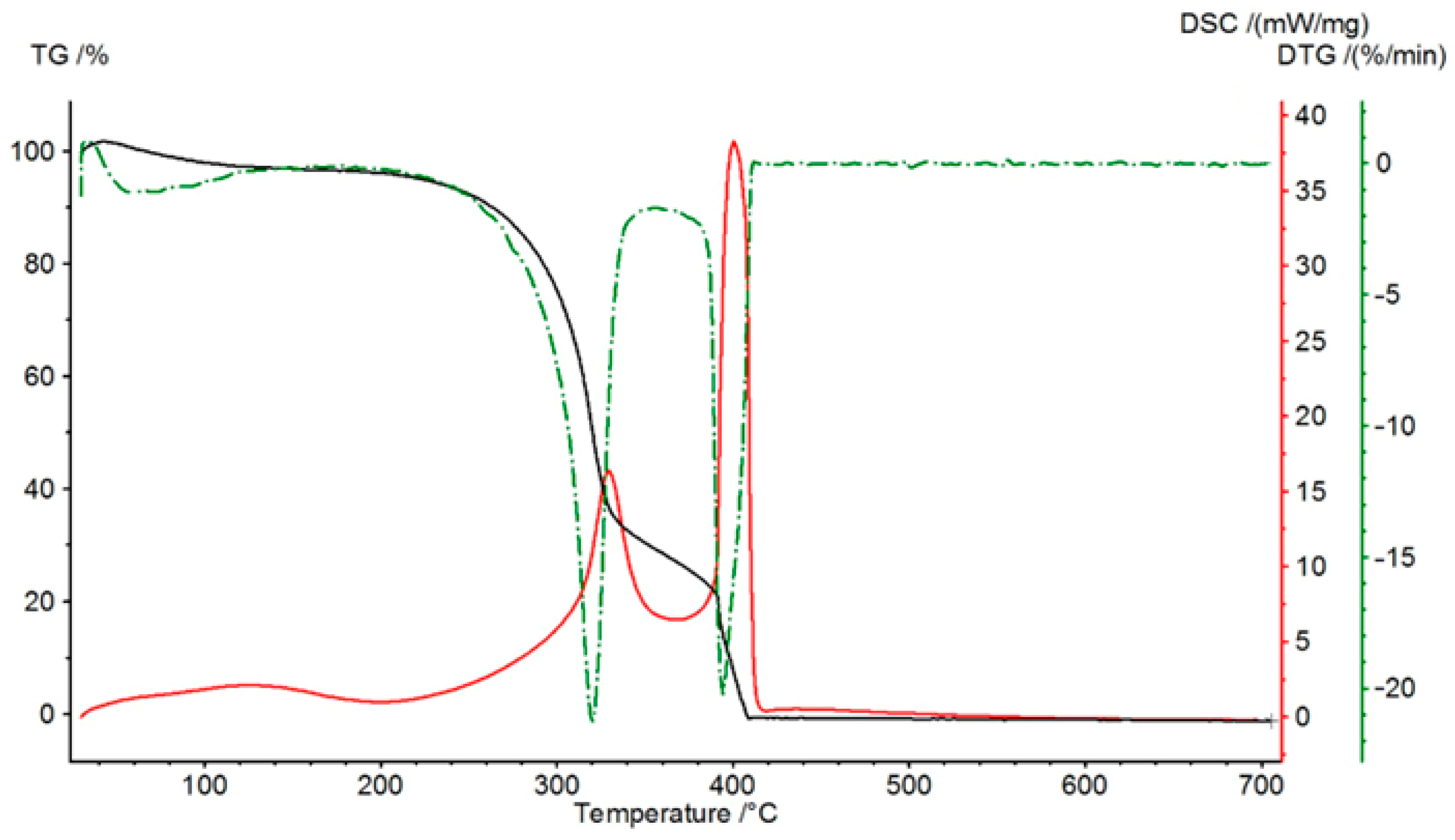

Figure 4 presents these curves for pine sawdust. The Thermogravimetric (TG) curve depicts the variation in the sample’s mass as a function of temperature. Its derivative, the Differential Thermogravimetric (DTG) curve, which expresses the rate of mass change, is instrumental in distinguishing between overlapping stages of the decomposition process and identifying the temperature of the most rapid mass loss. Concurrently, the Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) curve shows the heat flow as a function of temperature, enabling an assessment of the endothermic and exothermic effects during heating. The overall decomposition can be categorized into two primary stages: an initial stage of volatile release occurring between 300 and 350 °C, followed by a second stage involving the decomposition of the residual coke at 380–420 °C.

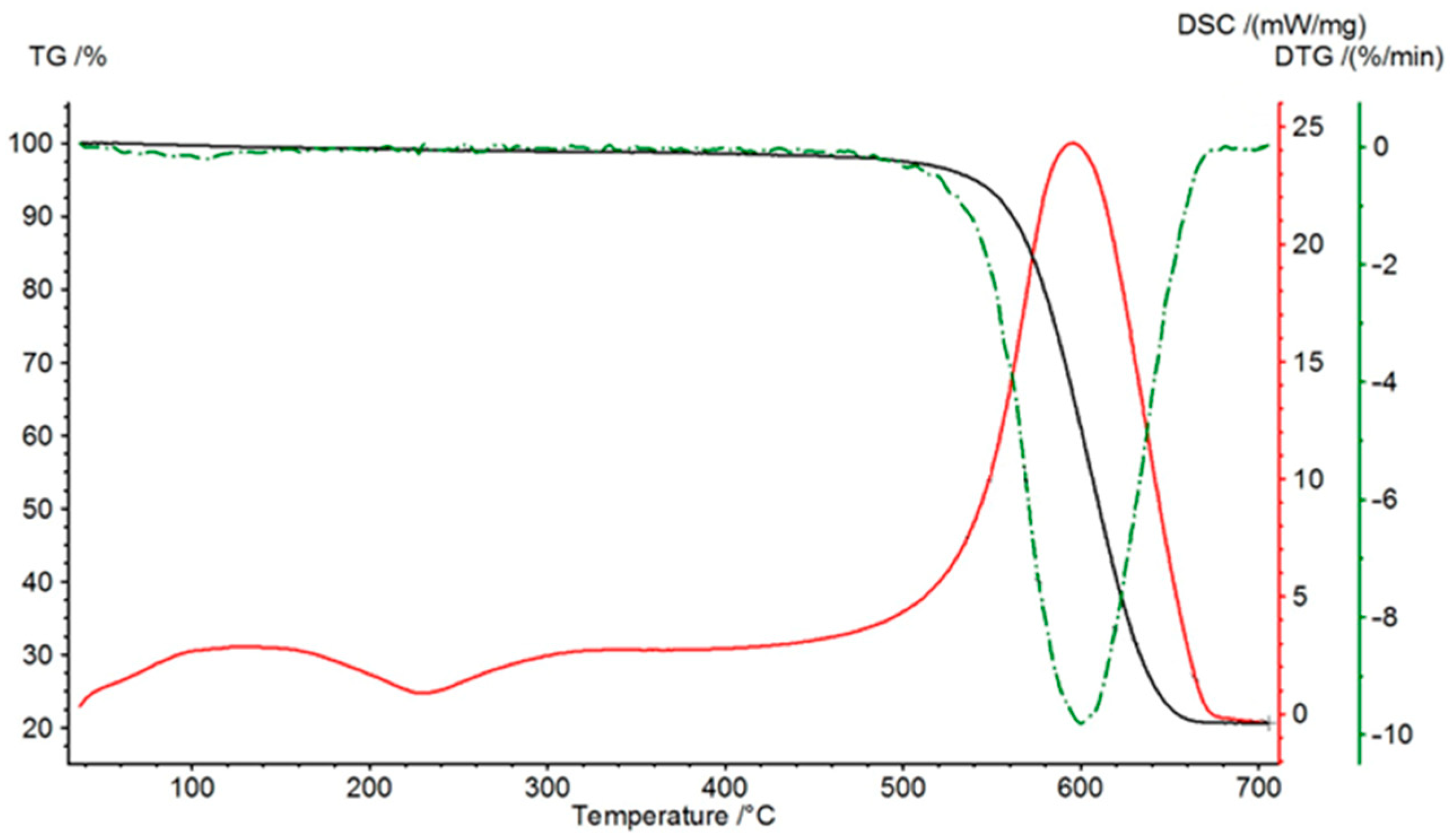

Figure 5 shows the decomposition curves of anthracite. In this case, it is clear that the process of thermal-oxidative destruction occurs in one stage—the decomposition of carbon, which occurs in the range from 500 to 680 °C.

Figure 6 shows the results of comparison of thermogravimetric analysis of composite fuel and mixture. The process of thermal decomposition of mixtures and composites can be divided into several main stages: 300–360 °C is the release of volatiles, 380–520 °C is the decomposition of coke residue and the reaction of active centers with oxygen, it is worth noting that these 2 processes in the composite are combined, unlike the mixture, which indicates a non-additive addition of characteristics, the third stage is the decomposition of the carbon part of anthracite 520–680 °C. There are no significant differences in the decomposition process, since the sawdust and coal particles are in close proximity, lying in the crucible, unlike the dust-air fuel supply in subsequent methods.

Qualitative analysis of the derivative thermogravimetric curves (DTG) shows that for the composite fuel, the peaks corresponding to volatile release and coke residue decomposition overlap and shift, demonstrating a more intimate interaction between the stages compared to the mechanical mixture, where these peaks are more separated. This is visual evidence of a synergistic mechanism facilitating composite pyrolysis.

As a result of the experiments, dependences of the flash delay time on the coal content in the sample were obtained. In experiments on ignition of dust suspension in a vertical tube furnace, it was not possible to ignite a sample consisting of 100 percent anthracite. The results of comparing the flash delay time (the graph shows the average time value calculated from a series of experiments for each sample) on the coal content in the sample are shown in

Table 2.

The active surface centers formed during mechanical activation specifically enhance the combustion process by serving as preferential sites for oxygen chemisorption and reaction initiation. This reduces the ignition delay time by facilitating earlier heterogeneous ignition. The TGA/DTG data (

Figure 6) confirm that the processes of volatile release and char residue decomposition are indeed combined in the composite fuel, occurring in overlapping temperature ranges (380–520 °C), unlike in the mechanical mixture, where these stages are more distinct.

The flash time of the composite is lower than that of the mixture, which also indicates a non-additive behavior of properties, which occurs due to the appearance of a common surface of coal and sawdust particles as a result of processing, and the ignition time of the composite fuel is lower than that of pure sawdust for each sample. In addition, adding coal to sawdust reduces the flash time compared to pure sawdust (for samples with a biomass content of 70% and 50%), this occurs due to the reaction of oxygen and radical centers on the coal surface, the amount of which is significantly higher than that of sawdust, the reaction of which initiates the combustion of the sawdust component in the sample.

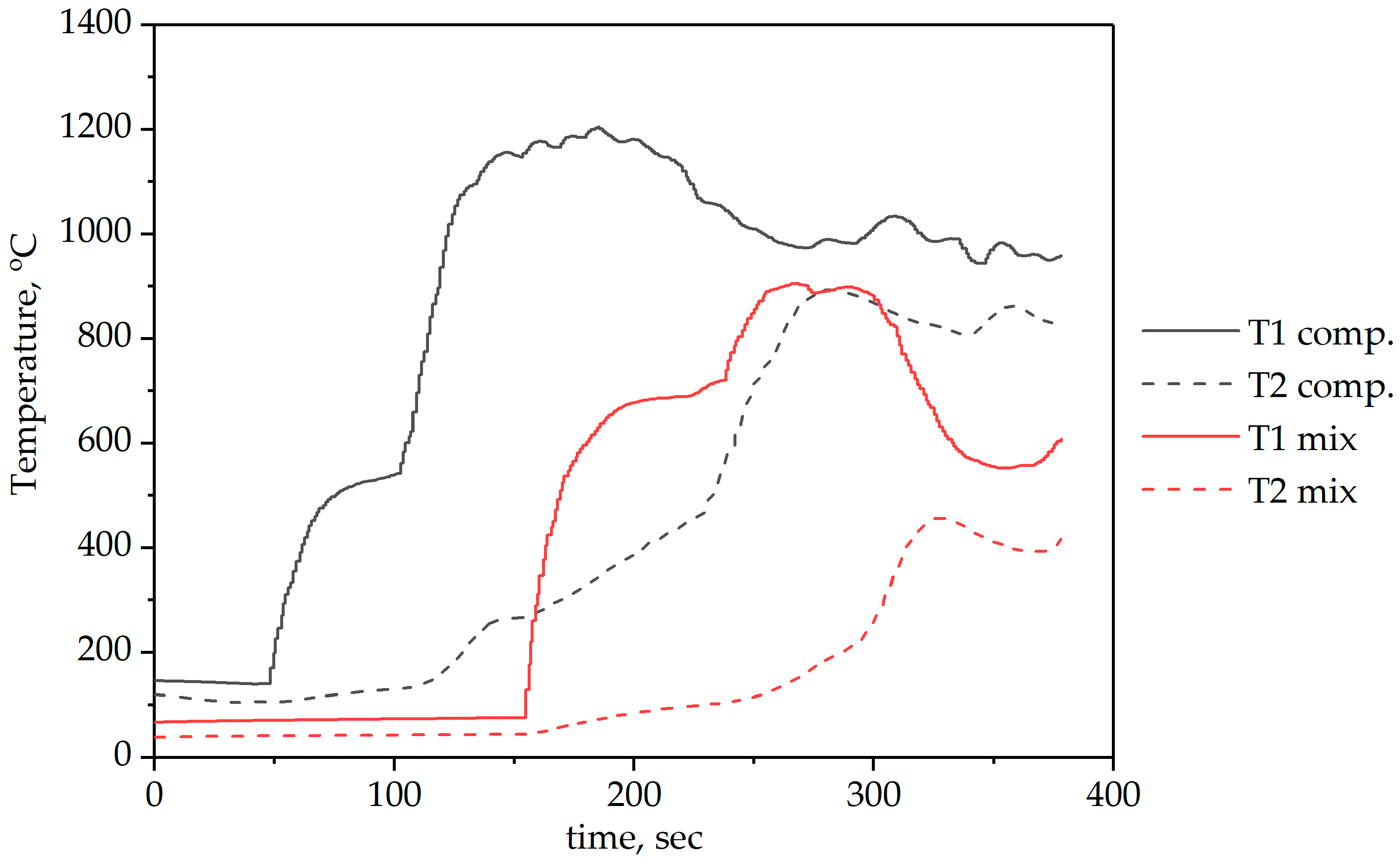

The results of the flare combustion experiments are presented as temperature dependencies at key points of the burner stand (

Figure 7 and

Figure 8). Curves T1 and T2 represent temperatures measured at two different locations in the combustion chamber (see

Figure 2), with thermocouple 1 located closer to the burner nozzle and thermocouple 2 located in the combustion chamber.

The following results were obtained during flame stabilization in the first part of the test bench for mixture and composite samples, presented in

Table 3.

The mixture with the ratio 2 component ratio burned unstably, with flame pulsations occurring.

With the addition of air, the torch broke away from the nozzle and lengthened, and the combustion was distributed deep into the furnace into the combustion chamber. The results obtained using thermocouples are presented in

Table 4.

The combustion process of the composite fuel took place at higher temperatures, and the flame was stable, unlike the combustion of the mixture. This superior performance is attributed to the synergistic interaction between the components within the composite structure. The intimate contact between coal and sawdust particles, achieved through mechanical activation, facilitates a continuous reaction zone. The rapid release and combustion of volatiles from the biomass component create a high-temperature environment that enhances the ignition and combustion of the less reactive anthracite char. On the contrary, coal provides stability and active surface sites that support the combustion process. In contrast, the mechanical mixture lacks this integrated structure, leading to segregated combustion of the components. This results in flame pulsations, as seen with the Ratio 2 mixture, and lower overall temperatures due to less efficient heat release and possible local extinctions.

As a result of the studies of flare combustion in various modes, data on the temperature distribution in the furnace were obtained. The studies showed more complete combustion of the composite fuel sample, as evidenced by the higher process temperature. In addition, the combustion of the composite more quickly reaches its stable mode. The results obtained correlate for all three methods; the technology for preparing composite fuel has opened up the possibility of igniting a low-reaction type of coal, which opens up wide possibilities for its use.

The conducted study of the ignition and combustion processes of composite fuel based on pine sawdust and anthracite demonstrates significant differences from previously studied systems with brown coal [

25]. Unlike brown coal composites, which are characterized by rapid ignition (ignition delay of 50–80 ms at 600 °C) due to the high content of volatiles, anthracite mixtures exhibit more inertial behavior, delay of 120–150 ms under the same conditions. This is due to a lower proportion of volatile components and a higher degree of carbonization of anthracite. In addition, if in the case of brown coal, joint thermal decomposition of biomass and coal was observed in a single temperature range 300–500 °C, then for anthracite, the processes of sawdust and coal destruction occur more separately, which is confirmed by thermogravimetric analysis data. These results are consistent with the findings of other studies, which also note that the classical ability of composite fuels is highly dependent on the type of coal. For example, the work of Zhou et al. [

26] showed that the interaction of biomass with brown coal leads to more pronounced synergistic effects compared to anthracite.

The obtained data emphasize the low degree of impact for anthracite-based composites, since it allows for exceeding its low power step. This is consistent with the results [

13], where it was shown that mechanochemical treatment creates active sites on the particle surface that cause ignition. Thus, the present study makes additional work by demonstrating that even for difficult-to-burn coals such as anthracite, stable and efficient combustion can be achieved to optimize the composition and processing methods of composite fuels.

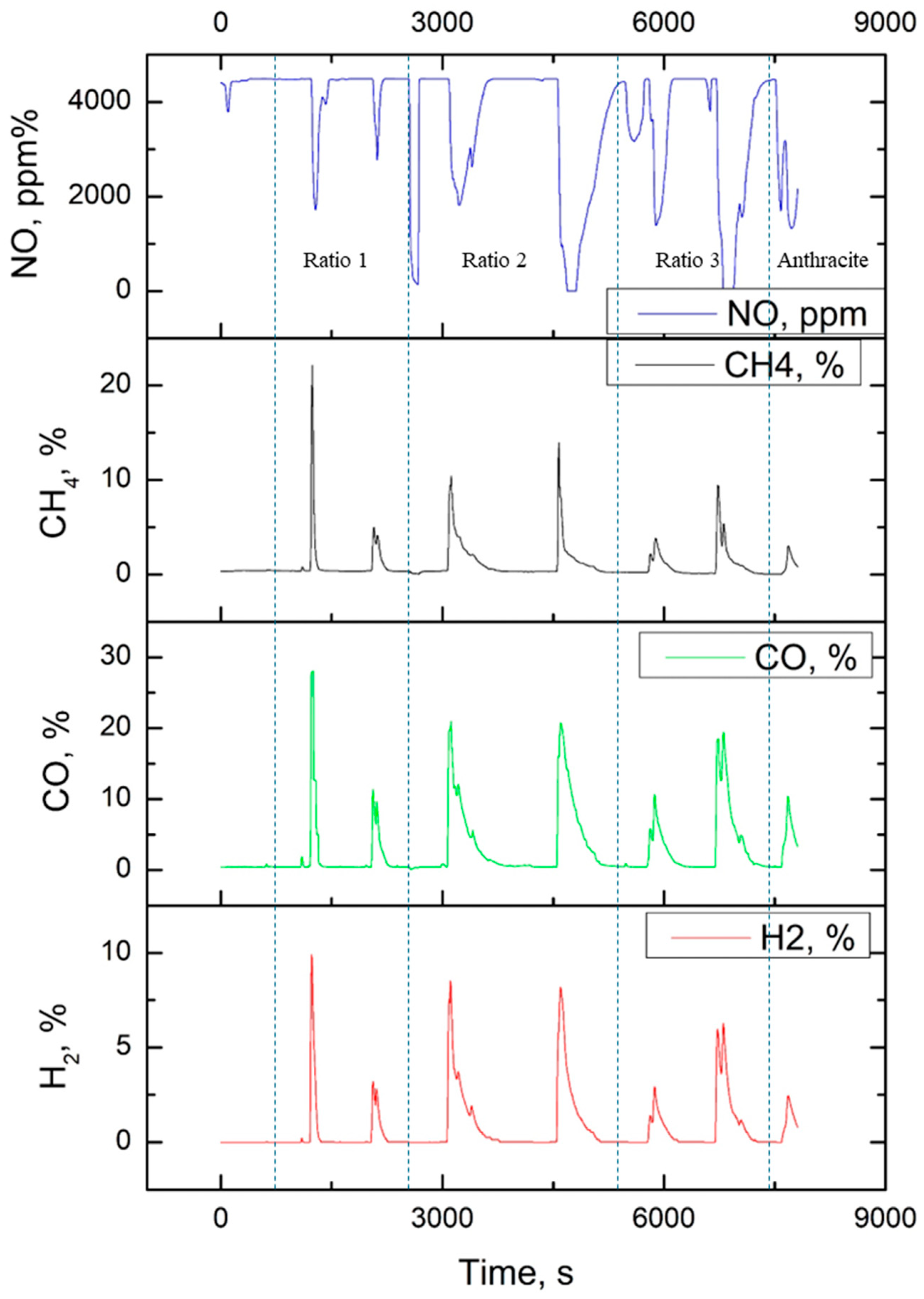

As a result of experiments on fuel gasification, a synthesis gas composition was obtained depending on the composition and method of obtaining the fuel. Gasification experiments were carried out on samples of mixtures and composite fuels in ratios of 1–3, as well as on a sample of anthracite; the results are shown in

Figure 9.

For each concentration, the temperature regime of the experimental setup was selected. The data contain measurements of gas concentrations (H2, CO, CH4, NO) during gasification of various fuel samples. Each sample is a mixture of sawdust and coal in different proportions, as well as pure coal. The following conclusions can be made based on the dynamic process, depending on the concentration composition of the fuel:

The highest concentrations of H2 are observed for ratio 1 up to 9.91%. Composite samples show a smoother release of hydrogen. The maximum values of CO reach 28.04% for the sample of ratio 1. Composite samples demonstrate more stable CO levels. The highest concentrations of CH4 up to 22.1% are recorded for samples with a high sawdust content. Pure coal emits less methane. The concentration of NO is high due to the operation of the plasma torch. For composite fuel, there is a decrease in the concentration of NO to 0 ppm, which indicates the redistribution of oxygen during the gasification process and stable formation of CO.

Samples with ratio 1 demonstrate the highest activity at the beginning of the process but are quickly depleted. Composite fuels provide more uniform gas evolution. The mixture shows sharp peaks in gas evolution: H2 reaches 9.91%, CO—28.04%, and CH4—22.1%, but then the concentration of gases quickly decreases. Composite fuel behaves differently: the increase in the concentrations of H2 up to 3.19 and CO up to 11.31% is smoother, and CH4 is retained longer, although at lower values—4.97%. The composite version provides stability, but with smaller peaks, while the usual mixture gives an intense, but short-term release of gases.

Samples of ratio 2. The mixture shows high but unstable concentrations: H2 up to 8.52%, CO up to 20.97%, CH4 up to 10.38%. Composite fuel softens the fluctuations: CO reaches 20.72%, and CH4—13.9%, but with a more uniform distribution over time. The composite composition reduces sharp jumps, making the process more controllable, while the usual mixture gives higher but less stable indicators.

Samples of ratio 3. The mixture releases H2 up to 6.78% and CO up to 19.04% quickly, but with drops, the composite analogue smooths out the dynamics: H2 increases to 6.27%, CO to 19.42%, and CH4 is retained longer, despite a smaller peak of 5.35%. Composite fuel stabilizes the process but reduces peak values, while a conventional mixture provides a fast but less predictable gas release.

A potential microscopic mechanism explaining the more uniform gas evolution from the composite fuel involves the intimate contact and integrated surface between coal and biomass particles. This structure likely promotes more efficient and continuous heat and mass transfer during gasification, preventing the rapid, isolated decomposition of biomass volatiles seen in mixtures and leading to a steadier release of syngas components (H2, CO) over time. Establishing a detailed thermodynamic or kinetic model would be valuable to further explain this non-additive behavior but is beyond the scope of the current experimental study.

The conducted set of experiments on thermal decomposition, ignition, combustion, and gasification is unique in that composite fuels continue to produce a non-additive, synergistic effect compared to their mechanical mixtures. This synergy is not random, but rather a result of the deep structural integration of the components achieved during mechanochemical activation. The formation of a unified, developed surface and strong interfacial bonds between coal particles and biomass creates conditions for efficient heat and mass transfer, which underlies the observed improvements.

This synergy is consistently observed at all stages of thermochemical conversion. At the thermal decomposition stage, it manifests itself in overlapping and shifted peaks on the DTG curves (

Figure 6), indicating coupled component decomposition processes, with the flying biomass initiating and enhancing the destruction of the difficult-to-decompose anthracite.

Under ignition conditions, the established ignition delay time (

Table 2) is due to the presence of active centers on the coal surface, which act as catalytic sites for igniting the biomass’s volatiles. This leads to a more rapid transition to the homogeneous combustion stage.

During the combustion stage, the synergistic effect is realized as an increase in temperature in the standard zone and increased flame stability (

Table 3). This predicts the formation of a continuous combustion zone, in which the volatile components of the biomass are characterized by stable combustion of the anthracite coke residue, compensating for its low class tendency.

Finally, during the gasification process, the advantages of the integrated composite structure continue in a smoother and more uniform syngas production profile (

Figure 9). This is due to the controlled, sequential conversion of components within a single fuel matrix, which ensures localized superheating and complete conversion.

Thus, the combined data allows us to conclude that the mechanochemically synthesized composite is not simply a mixture, but a new, purposefully created fuel whose properties surpass those of its individual components in strength. A key practical result of this is the ability to effectively utilize even low-reactivity anthracite coal due to its synergistic interaction with biomass.

4. Conclusions

The results of comparative thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of composite fuel and mixtures with different carbon content show that the thermal decomposition process has several stages. The first stage is the release of volatile fractions; the second stage is the decomposition of the coke residue and the reaction of active centers with oxygen; the third stage is the decomposition of the carbon part of the coal.

When analyzing the flash time of the composite, it was found that it is lower than that of the mixture, which, together with the TGA results, indicates a non-additive behavior of properties, which occurs due to the appearance of a common surface of coal particles and sawdust as a result of processing. In addition, the addition of coal to sawdust reduces the flash time compared to pure sawdust, which occurs due to the reaction of oxygen and radical centers on the coal surface, the amount of which is significantly higher than that of sawdust, the reaction of which initiates the combustion of the sawdust component in the sample. Studies of flare combustion of the obtained composite fuel showed more complete combustion than that of the mixture, as evidenced by the process temperature, as well as gas analyzer data.

As a result, it was found that the composite fuel has increased flammability due to the non-additive interaction of the components, which allows for more efficient combustion of solid organic fuel and waste, opening up new possibilities for its use.

Samples with ratio 1 show the highest activity early in the process but quickly become exhausted. Composite fuels provide a wider gas partitioning. This results in a more pronounced O2 reduction mid-process, which can lead to higher oxygen consumption during peak gasification stages. Clean coals show significantly lower gasification rates than blends, especially for H2 and CH4.

This study demonstrates that the mechanochemical activation of coal-biomass blends to create composite fuels yields significant non-additive advantages over conventional mechanical mixtures. The key novelty of this work lies in the comprehensive experimental evidence linking the composite’s structure, formed by joint grinding, to its superior performance across all stages of thermochemical conversion—from accelerated ignition and stable combustion to uniform gasification. This approach moves beyond simple blending and provides a foundation for engineering optimized composite fuels, particularly for hard-to-burn coals like anthracite.

The practical application of sawdust-anthracite mixtures and composites in power engineering holds significant promise. The enhanced combustion characteristics, such as reduced ignition delay and improved flame stability, make these fuels suitable for co-firing in existing coal-fired power plants with minimal modifications. The findings of this study provide a foundation for optimizing fuel blends in industrial settings, aligning with global efforts to transition toward sustainable energy solutions.