Emerging Issues of Corrosion in Nuclear Power Plants: The Case of Small Modular Reactors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Corrosion Processes in Nuclear Reactors

- This involves a uniform loss of metal across the entire surface.

- This occurs at the boundaries of material grains, leading to localized corrosion.

- This happens when a material is exposed to both stress and a corrosive environment, which may lead to stress corrosion cracking (SCC).

- This is characterized by localized dissolution of material, resulting in the rapid formation of holes.

- This is a type of material failure that arises when a material is subjected to repeated stress while simultaneously being exposed to corrosion. This can lead to cracks and eventual structural failure.

- This develops in areas where flow is restricted, often occurring in spaces with limited access to working fluids.

- This results from the contact between two different metals that are in contact with the same corrosive medium. The less noble metal corrodes more quickly when in contact with the more noble metal (which is protected).

- This refers to the chemical deterioration of a material due to elevated temperatures.

- This occurs when a specific alloying element or alloy phase dissolves preferentially under certain conditions.

- This refers to the changes (for better or worse) in the properties of a material, structure, or system over time or with use.

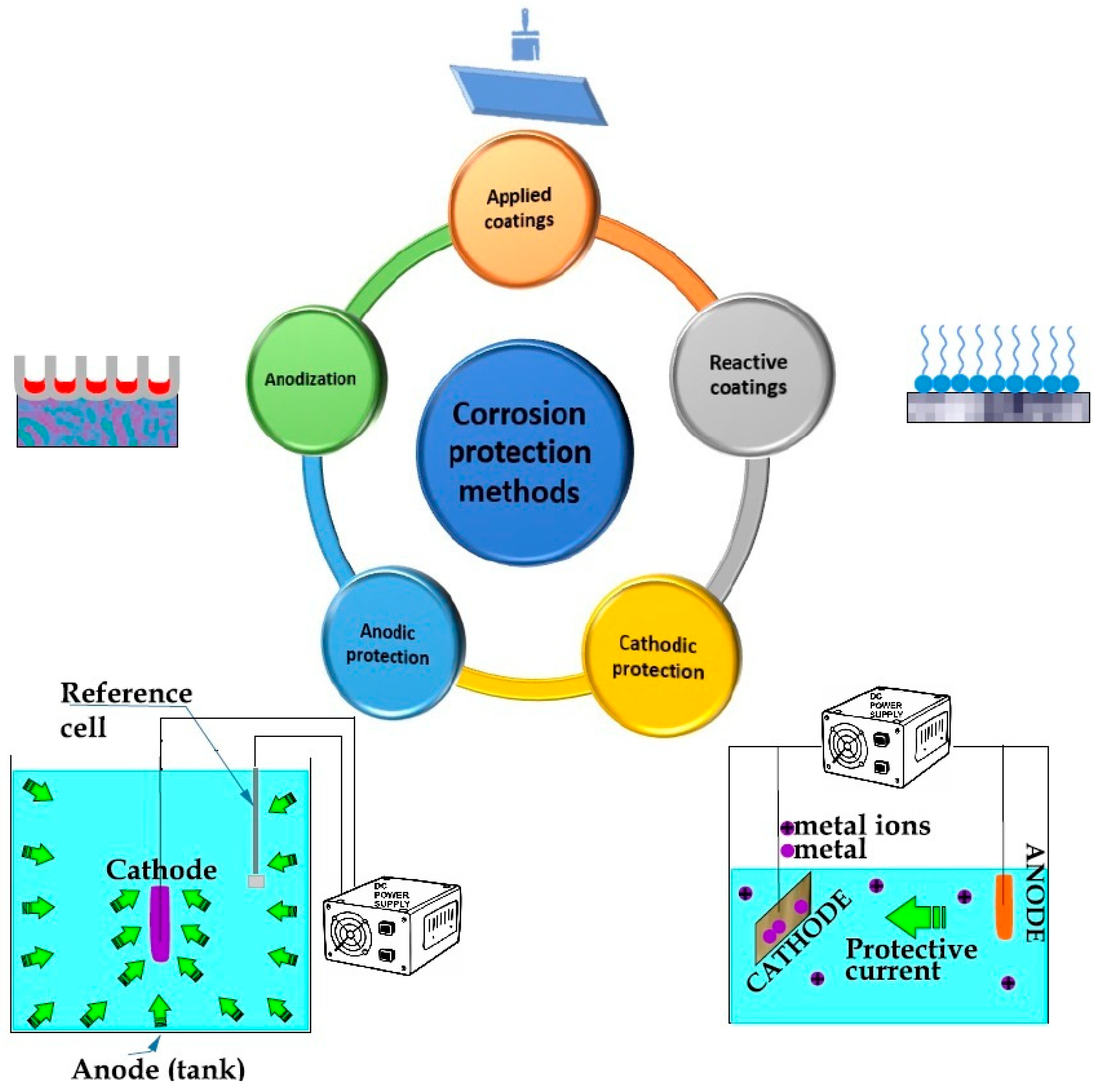

- Applied coatings techniques like plating, painting, and enamel application serve as barriers made of corrosion-resistant materials between the environment and the structural material.

- Corrosion inhibitors can be added to create an electrically insulating reactive coating on metal surfaces.

- In the anodizadion process uniform pores appear in the oxide film on metals under electrochemical conditions, making the oxide layer thicker than the passive layer.

- In cathodic protection the metal surface acts as the cathode in an electrochemical cell. This approach is widely employed to safeguard steel pipelines, tanks, pier piles, ships, and offshore oil platforms.

- In anodic protection the metal surface serves as the anode in an electrochemical cell.

- Low-temperature radiation hardening and embrittlement.

- Radiation-induced segregation and phase stability.

- Irradiation creep.

- Void swelling.

- High-temperature helium embrittlement.

3. Cooling Agents

3.1. Small Modular Reactors Cooled with Water

3.2. Molten-Salt-Cooled Small Modular Reactors

3.3. Liquid Metal-Cooled Fast Reactors

3.4. Gas-Cooled Nuclear Small Modular Reactors

4. Mitigation Measures in Cooling Systems to Prevent Corrosion

5. Materials

- Decreasing core enthalpy input;

- Reducing hydrogen generation;

- Improving cladding materials;

- Enhancing containment control.

- Developing non-zirconium cladding with high oxidation resistance and strength;

- Enhancing the high-temperature oxidation resistance and strength of zirconium alloy cladding;

- Exploring alternative fuel forms that offer improved performance and fission product retention.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lloyd, C.A.; Roulstone, T.; Lyons, R.E. Transport, constructability, and economic advantages of SMR modularization. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2021, 134, 103672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.I. Review of Small Modular Reactors: Challenges in Safety and Economy to Success. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 41, 2761–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewska-Śmietanko, D.K.; Miśkiewicz, A.; Smoliński, T.; Zakrzewska-Kołtuniewicz, G.; Chmielewski, A. Selected Legal and Safety Aspects of the “Coal-To-Nuclear” Strategy in Poland. Energies 2024, 17, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanatta, M.; Patel, D.; Allan, T.; Cooper, D.; Craig, M.T. Technoeconomic analysis of small modular reactors decarbonizing industrial process heat. Joule 2023, 7, 713–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevisan, S.; Buchbjerg, B.; Guedez, R. Power-to-heat for the industrial sector: Techno-economic assessment of a molten salt-based solution. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 272, 116362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Dios Sánchez, J. Key Emerging Issues and Recent Progress Related to Plant Chemistry/Corrosion (PWR, CANDU, and BWR Nuclear Power Plants). Available online: https://antinternational.com/docs/samples/LCC/SAMPLE%20-%20LCC19-Key%20Emerging%20Issues%20NPC-2023-%20Sample.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Vujic, J.; Bergman, R.M.; Skoda, R.; Miletic, M. Small modular reactors: Simpler, safer, cheaper? Energy 2012, 45, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krall, L.M.; Macfarlane, A.M.; Ewing, R.C. Nuclear waste from small modular reactors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2111833119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Huang, G.H.; Liu, R.L.; Chen, J.P.; Luo, B.; Fu, Y.P.; Zheng, X.G.; Han, D.C.; Liu, Y.Y. Perspective on Site Selection of Small Modular Reactors. JEIL 2020, 3, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattant, F.O. Materials Ageing in Light-Water Reactors: Handbook of Destructive Assays, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 978-3-030-85600-7. [Google Scholar]

- Vachtsevanos, G.; Natarajan, K.A.; Rajamani, R.; Sandborn, P. Corrosion Processes Sensing, Monitoring, Data Analytics, Prevention/Protection, Diagnosis/Prognosis and Maintenance Strategies (Structural Integrity), 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 2, ISBN 978-3030328337. [Google Scholar]

- Zinkle, S.J.; Was, G.S. Materials challenges in nuclear energy. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 735–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, K.C.; Madhushree, C.; Chandini, M.S.; Shree, N.; Hemanth, S.; Jeevanl, T.P. Corrosion in Steel Structures: A Review. J. Mines Met. Fuels 2025, 73, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz Martínez-Viademonte, M.; Abrahami, S.T.; Hack, T.; Burchardt, M.; Terryn, H. A Review on Anodizing of Aerospace Aluminum Alloys for Corrosion Protection. Coat 2020, 10, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimha, R. Latest Exploration on Natural Corrosion Inhibitors for Industrial Important Metals in Hostile Fluid Environments: A Comprehensive Overview. J. Bio Tribo Corros. 2019, 5, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gressier, F.; Mascarenhas, D.; Taunier, S.; Le-Calvar, M.; Bretelle, J.-L.; Ranchoux, G. EDF PWRs primary coolant purification strategies. In Proceedings of the Nuclear Plant Chemistry Conference, International Conference on Water Chemistry of Nuclear Reactor Systems (NPC 2012), Paris, France, 23–27 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Good Practices for Water Quality Management in Research Reactors and Spent Fuel Storage Facilities, IAEA Nuclear Energy Series No. NP-T-5.2; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lister, D.; Uchida, S. Determining water chemistry conditions in nuclear reactor coolants. J. Nucl. Sci. 2015, 52, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Atomic Energy Agency. High-Temperature On-Line Monitoring of Water Chemistry and Corrosion Control in Water Cooled Power Reactors, IAEA-TECDOC-1303; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sindelar, R.L.; Chandler, G.T.; Micalonis, J.L. Water quality and corrosion: Considerations for nuclear reactor systems. J. SCAS 2011, 9, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, Y.H.; Lee, N.Y.; Park, B.H.; Park, S.C.; Kim, E.K. Primary Coolant pH Control for Soluble Boron-Free PWRs. In Proceedings of the Transactions of the Korean Nuclear Society Autumn Meeting, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, 9–30 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rizk, J.T.; McMurray, J.W.; Wirth, B.D. Boron and lithium aqueous thermochemistry to model crud deposition in pressurized water reactors. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2024, 195, 107289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzaben, Y.; Sanchez-Espinoza, V.H.; Stieglitz, R. Core neutronics and safety characteristics of a boron-free core for Small Modular Reactors. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2019, 132, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.S.; Kim, A.-Y.; Kim, S.-H.; Yoon, J.; Zee, S.-Q. Design criteria of primary coolant chemistry in SMART-P. In Proceedings of the Korean Nuclear Society Conference, Busan, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, K.; Ickes, M.R.; Burke, M.A.; Was, G.S. The effect of potassium hydroxide primary water chemistry on the IASCC behavior of 304 stainless steel. J. Nucl. Mater 2022, 558, 153323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, P.; Smith, J.; Demma, A.; Burke, M.; Fruzzetti, K. Potassium Hydroxide for PWR Primary Coolant pH Control: Materials Qualification Testing. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Water Chemistry in Nuclear Reactor Systems, NPC 2018, San Francisco, CA, USA, 9–14 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, T.; Bao, Y.; Liu, X.; Shi, X.; Guo, X.; Han, Z.; Andresen, P.L.; Zhang, L.; Chen, K. Insights into the stress corrosion cracking propagation behavior of Alloy 690 and 316 L stainless steel in KOH versus LiOH oxygenated water. Corros. Sci. 2023, 224, 111556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, B.; Weng, M. Chemical Flocculation for Treatment of Simulated Liquid Radwaste From Nuclear Power Plant. At. Energy Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 781–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjmand, F.; Wang, J.; Zhang, L. Zinc addition and its effect on the corrosion behavior of a 30% cold forged Alloy 690 in simulated primary coolant of pressurized water reactors. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 791, 1176–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.-H.; Lim, D.-S.; Choi, J.; Song, K.-M.; Lee, J.-H.; Hur, D.-H. Effects of Zinc Addition on the Corrosion Behavior of Pre-Filmed Alloy 690 in Borated and Lithiated Water at 330 °C. Materials 2021, 14, 4105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arjmand, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Guan, K. Effect of zinc injection on the electrochemical behavior and crack growth rate of a 316 L stainless steel in simulated primary coolant of pressurized water reactors. Mater. Charact. 2021, 177, 111177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-S.; Park, S.-C.; Park, K.-R.; Yang, H.; Yang, O. Effect of zinc injection on the corrosion products in nuclear fuel assembly. Nat. Sci. 2013, 5, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Status of Research and Technology Development for Supercritical Water Cooled Reactors; IAEA-TECDOC-1869; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Roper, R.; Harkema, M.; Sabharwall, P.; Riddle, C.; Chisholm, B.; Day, B.; Marotta, P. Molten salt for advanced energy applications: A review. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2022, 169, 108924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Shin, D.; Yoon, D.; Choi, E.-Y.; Lee, C.H. Corrosion Behavior of Candidate Structural Materials for Molten Salt Reactors in Flowing NaCl-MgCl2. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 1, 2883918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, L.C.; Ambrosek, J.W.; Sridharan, K.; Anderson, M.H.; Allen, T.R. Materials corrosion in molten LiF–NaF–KF salt. J. Fluorine Chem. 2009, 130, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergari, L.; Scarlat, R.O.; Hayes, R.D.; Fratoni, M. The corrosion effects of neutron activation of 2LiF-BeF2 (FLiBe). Nucl. Mater. Energy 2023, 34, 101289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Chen, B.; Ge, M.; Qian, Y.; Wang, Q. Corrosion behavior of GH3535 alloy in molten LiF–BeF2 salt. Corros. Sci. 2022, 199, 110168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulejmanovic, D.; Kurley, J.M.; Robb, K.; Raima, S. Validating modern methods for impurity analysis in fluoride salts. J. Nucl. Mater. 2021, 553, 152972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Y.; Yuanwei, L. Comparative review of different influence factors on molten salt corrosion characteristics for thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 235, 111485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, J.; Wu, W.; Zhou, W. Corrosion in the molten fluoride and chloride salts and materials development for nuclear applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 97, 448–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Sridharan, K. Corrosion of Structural Alloys in High-Temperature Molten Fluoride Salts for Applications in Molten Salt Reactors. JOM 2018, 70, 1535–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Forsberg, C.W.; Simpson, M.F.; Guo, S.; Lam, S.T.; Scarlat, R.O.; Carotti, F.; Chan, K.J.; Singh, P.M.; Donigeret, W.; et al. Redox potential control in molten salt systems for corrosion mitigation. Corros. Sci. 2018, 144, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paydar, A.Z.; Balgehshiri, S.K.M.; Zohuri, B. Chapter 1—Next generation nuclear plant (NGNP). In Advanced Reactor Concepts (ARC), 1st ed.; Paydar, A.Z., Balgehshiri, S.K.M., Zohuri, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 1–102. ISBN 9780443189890. [Google Scholar]

- Won, J.H.; Cho, N.Z.; Park, H.M.; Jeong, Y.H. Sodium-cooled fast reactor (SFR) fuel assembly design with graphite-moderating rods to reduce the sodium void reactivity coefficient. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2014, 280, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, M. Advanced Reactors and Future Concepts. In Nuclear Engineering; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2018; pp. 263–295. ISBN 978-0-08-100962-8. [Google Scholar]

- Suppes, G.J.; Storvick, T. Chapter 12—Nuclear Power Plant Design. In Sustainable Nuclear Power; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 319–351. ISBN 978-0-12-370602-7. [Google Scholar]

- Judd, A.M. An Introduction to the Engineering of Fast Nuclear Reactors; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 192–238. [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission. Overview of Liquid Sodium Fires: A Case of Sodium-Cooled Fast Reactors; Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission: Ottawa, ON, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa, T.; Kato, S.; Yoshida, E. Compatibility of FBR materials with sodium. J. Nucl. Mater. 2009, 392, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, E.; Kato, S.; Wada, E. Post-corrosion and metallurgical analyses of sodium piping materials operated for 100,000 h. In Liquid Metal Systems; Borgstedt, H.U., Frees, G., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 55–66. ISBN 978-1-4615-1977-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mangus, D.; Napora, A.; Briggs, S.; Anderson, M.; Nollet, W. Design and demonstration of a laboratory-scale oxygen-controlled liquid sodium facility. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2021, 378, 111093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foust, O. Sodium-NaK Engineering Handbook; Gordon and Breach, Science Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1976; ISBN 0-677-03030-4. [Google Scholar]

- Rivollier, M.; Courouau, J.-L.; Tabarant, M.; Blanc, C.; Jomard, F.; Giorgi, M.-L. Further insights into the mechanisms involved in the corrosion of 316L(N) austenitic steel in oxygenated liquid sodium at 550 °C. Corros. Sci. 2020, 165, 108399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.; Crawford, D. Lead-Cooled Fast Reactor Systems and the Fuels and Materials Challenges. STNI 2007, 2007, 097486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, M.; Woloshun, K.; Rubio, F.; Maloy, S.A.; Hosemann, P. Heavy Liquid Metal Corrosion of Structural Materials in Advanced Nuclear Systems. JOM 2013, 65, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorley, A.; Tyzack, C. Corrosion and mass transport of steel and nickel alloys in sodium systems. In Liquid Alkali Metals; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 1973; ISBN 978-0-7277-5126-3. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, D.T. 2–Small modular reactors (SMRs) for producing nuclear energy: International developments. In Handbook of Small Modular Nuclear Reactors, 2nd ed.; Ingersoll, D.T., Carelli, M.D., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2014; pp. 29–50. ISBN 9780128239162. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaba, N.; Ohashi, H.; Takeda, T. Hydrogen permeation through heat transfer pipes made of Hastelloy XR during the initial 950 °C operation of the HTTR. J. Nucl. Mater. 2006, 353, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natesan, K.; Purohit, A.; Tam, S.W. Materials Behavior in HTGR Environments; Division of Engineering Technology, Office of Nuclear Regulatory Research, U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Graham, L.W. Corrosion of metallic materials in HTR-helium environments. J. Nucl. Mater. 1990, 171, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yan, D.; Li, G.; Tian, C.; An, J.; Tan, J.; Zheng, W.; Du, B.; Yin, H. Corrosion mechanisms and differences of Inconel 617 and Incoloy 800H under high-temperature air ingress accident. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2025, 184, 105725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnaw, F.; Gubner, R. Part II: Corrosion Topics. In Corrosion Atlas Case Studies, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; ISBN 9780443132278. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D. Behavior Comparison and Kinetics Simulation of Nuclear Graphite Corroded by Oxygen and Vapor. Master’s Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Contescu, C.I. Validation of Wichner Predictive Model for Chronic Oxidation by Moisture of Nuclear Graphite; Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2019. Available online: https://info.ornl.gov/sites/publications/Files/Pub131755.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Zhang, X.; Sun, F.; Xiong, G.; Wei, X.; Ding, M. A review of research progress of graphite oxidation in high temperature gas-cooled reactors. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 428, 113486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, C.; Kadak, A. Safeguards and Security for High-Burnup TRISO Pebble Bed Spent Fuel and Reactors. Nucl. Technol. 2024, 210, 1354–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabet, C. Review: Oxidation of SiC/SiC Composites in Low Oxidising and High Temperature Environment. In Materials Issues for Generation IV Systems; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jalan, V.; Bratten, A.; Shi, M.; Gerczak, T.; Zhao, H.; Poplawsky, J.D.; He, X.; Helmreich, G.; Wen, H. Influence of temperature, oxygen partial pressure, and microstructure on the high-temperature oxidation behavior of the SiC Layer of TRISO particles. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2025, 45, 116913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Wei, L.; Li, H.; Cao, J.; Fang, S. Radiation Protection Practices during the Helium Circulator Maintenance of the 10 MW High Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactor-Test Module (HTR-10). Sci. Technol. Nucl. Install. 2016, 2016, 5967831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanbury, D.M. Reduction potentials involving inorganic free radicals in aqueous solution. In Advances in Inorganic Chemistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1989; pp. 69–138. [Google Scholar]

- Pastina, B.; Isabey, J.; Hickel, B. The influence of water chemistry on the radiolysis of the primary coolant water in pressurized water reactors. J. Nucl. Mater. 1999, 264, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doniger, W.H.; Falconer, C.; Elbakhshwan, M.; Britsch, K.; Couet, A.; Sridharan, K. Investigation of impurity driven corrosion behavior in molten 2LiF-BeF2 salt. Corros. Sci. 2020, 174, 108823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridharan, K.; Allen, T.R. 12–Corrosion in Molten Salts. In Molten Salts Chemistry; Lantelme, F., Groult, H., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 241–267. [Google Scholar]

- Seifried, J.E.; Scarlat, R.O.; Peterson, P.F.; Greenspan, E. A general approach for determination of acceptable FLiBe impurity concentrations in Fluoride-Salt Cooled High Temperature Reactors (FHRs). Nucl. Eng. Des. 2019, 343, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, M.; Hu, L. Trace Elemental Analysis of Flibe by Neutron Activation Analysis in support of FHR Research. In Proceedings of the ANS Proceedings 2013, Atlanta, GA, USA, 16–20 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, J.H. Preparation and Handling of Salt Mixtures for the Molten Salt Reactor Experiment; Oak Ridge National Lab. (ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1971.

- Zong, G.; Zhang, Z.-B.; Sun, J.-H.; Xiao, J.-C. Preparation of high-purity molten FLiNaK salt by the hydrofluorination process. J. Fluor. Chem. 2017, 197, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, W. Chemical Research and Development for Molten-Salt Breeder Reactors; Oak Ridge National Lab.(ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1967.

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Li, B.; Zhao, Z. Characterization and removal of oxygen ions in LiF-NaF-KF melt by electrochemical methods. J. Fluor. Chem. 2015, 175, 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Song, Y.-L.; Tang, R.; Qian, Y. A novel purification method for fluoride or chloride molten salts based on the redox of hydrogen on a nickel electrode. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 35069–35076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsberg, C.W.; Lam, S.; Carpenter, D.M.; Whyte, D.G.; Scarlat, R.; Contescu, C.; Wei, L.; Stempien, J.; Blandford, E. Tritium Control and Capture in Salt-Cooled Fission and Fusion Reactors: Status, Challenges, and Path Forward. Nucl. Technol. 2017, 197, 119–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burchell, T.D. 4.10–Radiation Effects in Graphite. In Comprehensive Nuclear Materials; Konings, R.J.M., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 299–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hemanath, M.; Meikandamurthy, C.; Kumar, A.A.; Chandramouli, S.; Rajan, K.; Rajan, M.; Vaidyanathan, G.; Padmakumar, G.; Kalyanasundaram, P.; Raj, B. Theoretical and experimental performance analysis for cold trap design. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2010, 240, 2737–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appiah, R.; Heifetz, A.; Kultgen, D.; Tsoukalas, L.H.; Vilim, R.B. Dynamic Control of Sodium Cold Trap Purification Temperature Using LSTM System Identification. Energies 2024, 17, 6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latgé, C.; Sellier, S. Oxidation of Zirconium-Titanium Alloys in Liquid Sodium: Validation of a Hot Trap, Determination of the Kinetics. In Liquid Metal Systems: Material Behavior and Physical Chemistry in Liquid Metal Systems 2; Borgstedt, H.U., Frees, G., Eds.; Springer US: Boston, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov, F.A.; Konovalov, M.A.; Sorokin, A.P. Purification of liquid metal systems with sodium coolant from oxygen using getters. Therm. Eng. 2016, 63, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaizer, V.P.; Efimov, I.A.; Lastov, A.I.; Shereshkov, V.S.; Konovalov, É.E. Purification of the BR-10 sodium coolant from cesium radionuclides. Sov. At. Energy 1983, 54, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Li, H.; Du, B.; Yin, H.; He, X.; Ma, T. High-temperature reaction kinetics of Inconel 617 in impure helium. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2023, 34, 101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadakkers, W.J.; Schuster, H. Thermodynamic and kinetic aspects of the corrosion of high-temperature alloys in high-temperature gas-cooled reactor helium. Nucl. Technol. 1984, 66, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouillard, F.; Cabet, C.; Wolski, K.; Terlain, A.; Tabarant, M.; Pijolat, M.; Valdivieso, F. High temperature corrosion of a nickel base alloy by helium impurities. J. Nucl. Mater. 2007, 362, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabet, C.; Chapovaloff, J.; Rouillard, F.; Girardin, G.; Kaczorowski, D.; Wolski, K.; Pijolat, M. High temperature reactivity of two chromium-containing alloys in impure helium. J. Nucl. Mater. 2008, 375, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawabe, T.; Sonoda, T.; Furuya, M.; Kitajima, S.; Kinoshita, M.; Tokiwai, M. Microstructure of oxide layers formed on zirconium alloy by air oxidation, uniform corrosion and fresh-green surface modification. J. Nucl. Mater. 2011, 419, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartowska, B.; Starosta, W.; Sokołowski, P.; Wawszczak, D.; Smolik, J. Protective layers of zirconium alloys used for claddings to improve the corrosion resistance. Nukleonika 2024, 69, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrani, K.; Zinkle, S.J.; Snead, L.L. Advanced Oxidation-Resistant Iron-Based Alloys for LWR Fuel Cladding. J. Nucl. Mater. 2014, 448, 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Stueber, M.; Seifert, H.J.; Steinbrueck, M. Protective coatings on zirconium-based alloys as accident-tolerant fuel (ATF) claddings. Corros. Rev. 2017, 35, 141–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Analysis of Options and Experimental Examination of Fuels for Water Cooled Reactors with Increased Accident Tolerance (ACTOF); International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kashkarov, E.; Afornu, B.; Sidelev, D.; Krinitcyn, M.; Gouws, V.; Lider, A. Recent Advances in Protective Coatings for Accident Tolerant Zr-Based Fuel Claddings. Coatings 2021, 11, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartowska, B.; Starosta, W.; Waliś, L.; Smolik, J.; Pańczyk, E. Multi-Elemental Coatings on Zirconium Alloy for Corrosion Resistance Improvement. Coatings 2022, 12, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrani, K.A.; Parish, C.M.; Shin, D.; Pint, B.A. Protection of zirconium by alumina- and chromia-forming iron alloys under high-temperature steam exposure. J. Nucl. Mater. 2013, 438, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Chen, K.; Guo, X.; Zhang, L. A study on the corrosion and stress corrosion cracking susceptibility of 310-ODS steel in supercritical water. J. Nucl. Mater. 2019, 514, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, J.S.; Lee, C.B.; Lee, B.O.; Raison, J.; Mizuno, T.; Delage, F.; Carmack, J. Sodium fast reactor evaluation: Core materials. J. Nucl. Mater. 2009, 392, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.G.; Shin, Y.-H.; Park, J.; Hwang, I.S. High-Temperature Corrosion Behaviors of Structural Materials for Lead-Alloy-Cooled Fast Reactor Application. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-S.; Wang, Y.-F.; Chai, J.; Gong, W.; Wang, X.-Z. Additive manufactured ODS-FeCrAl steel achieves high corrosion resistance in lead-bismuth eutectic (LBE). J. Nucl. Mater. 2025, 604, 155516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Long, B.; Li, L.; Lu, S.; Yang, J. Lead-bismuth eutectic corrosion behavior of NbMoVCr refractory multi-principal element alloys coating synthesized by magnetron sputtering. J. Nucl. Mater. 2024, 599, 155230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, T.; Paviet, P. Corrosion of Containment Alloys in Molten Salt Reactors and the Prospect of Online Monitoring. J. Nucl. Fuel Cycle Waste Technol. 2022, 20, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karfidov, E.; Nikitina, E.; Erzhenkov, M.; Seliverstov, K.; Chernenky, P.; Mullabaev, A.; Tsvetov, V.; Mushnikov, P.; Karimov, K.; Molchanova, N.; et al. Corrosion Behavior of Candidate Functional Materials for Molten Salts Reactors in LiF–NaF–KF Containing Actinide Fluoride Imitators. Materials 2022, 15, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, R.H.; Alexander, R.; Chaudhary, N.; Sanyal, S.; Sengupta, P. Spectroscopic studies on natural fluorapatites irradiated with 10 MeV electrons. J. Nucl. Mater. 2024, 599, 155199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herschitz, R.; Seidman, D.N. An atomic resolution study of homogeneous radiation-induced precipitation in a neutron irradiated W-10at.% Re alloy. Acta Metall. 1984, 32, 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, E.A.; Hyde, J.M.; Saxey, D.W.; Lozano-Perez, S.; de Castro, V.; Hudson, D.; Williams, C.A.; Humphry-Baker, S.; Smith, G.D. Nuclear reactor materials at the atomic scale. Mater. Today 2009, 12, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.; Simonen, E.; Bruemmer, S.; Efsing, P. Microstructural Evolution in Neutron-Irradiated Stainless Steels: Comparison of LWR and Fast-Reactor Irradiations. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power System-Water Reactos, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 14–18 August 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Porollo, S.I.; Vorobjev, A.N.; Konobeev, Y.V.; Dvoriashin, A.M.; Krigan, V.M.; Budylkin, N.I.; Mironova, E.G.; Garner, F.A. Swelling and void-induced embrittlement of austenitic stainless steel irradiated to 73–82 dpa at 335–365 °C. J. Nucl. Mater. 1998, 258–263, 1613–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okita, T.; Sato, T.; Sekimura, N.; Garner, F.A.; Greenwood, L.R.; Wolfer, W.G.; Isobe, Y. Neutron-Induced Microstructural Evolution of Fe-15Cr-16Ni Alloys at ~400 C During Neutron Irradiation in the FFTF Fast Reactor; US Department of Energy, Office of Fusion Energy Sciences: Washington, DC, USA; Pacific Northwest National Lab. (PNNL): Richland, WA, USA, 2001.

- Bond, G.M.; Sencer, B.H.; Garner, F.A.; Hamilton, M.L.; Allen, T.R.; Porter, D.L. Void Swelling of Annealed 304 Stainless Steel at ∼370–385 °C and PWR-Relevant Displacement Rates. In Ninth International Symposium on Environmental Degradation of Materials in Nuclear Power Systems—Water Reactors; Minerals, Metals and Materials Society: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1999; pp. 1045–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Byun, T.; Garrison, B.; McAlister, M.; Chen, X.; Gussev, M.; Lach, T.; Le Coq, A.; Linton, K.; Joslin, C.; Carver, J.; et al. Mechanical behavior of additively manufactured and wrought 316L stainless steels before and after neutron irradiation. J. Nucl. Mater. 2021, 548, 152849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunes, M.A.; Harrison, R.W.; Donnelly, S.E.; Edmondson, P.D. A Transmission Electron Microscopy study of the neutron-irradiation response of Ti-based MAX phases at high temperatures. Acta Mater. 2019, 169, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumita, J.; Shibata, T.; Nakagawa, S.; Iyoku, T.; Sawa, K. Development of an Evaluation Model for the Thermal Annealing Effect on Thermal Conductivity of IG-110 Graphite for High-Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactors. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2009, 46, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego, N.C.; Burchell, T.D. A Review of Stored Energy Release of Irradiated Graphite; Oak Ridge National Lab. (ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 2011.

- Burchell, T.D.; Eatherly, W.P. The effects of radiation damage on the properties of GraphNOL N3M. J. Nucl. Mater. 1991, 179–181, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, C.; Panuganti, S.; Warren, P.H.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, Y.; Wheeler, K.; Frazer, D.; Guillen, D.P.; Gandy, D.W.; Wharry, J.P. Comparing structure-property evolution for PM-HIP and forged alloy 625 irradiated with neutrons to 1 dpa. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 857, 144058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, K.G.; Briggs, S.A.; Sridharan, K.; Yamamoto, Y.; Howard, R.H. Dislocation loop formation in model FeCrAl alloys after neutron irradiation below 1 dpa. J. Nucl. Mater. 2017, 495, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senor, D.; Youngblood, G.; Greenwood, L.; Archer, D.; Alexander, D.; Chen, M.; Newsome, G. Defect structure and evolution in silicon carbide irradiated to 1 dpa-SiC at 1100 °C. J. Nucl. Mater. 2003, 317, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelles, D.S. Void swelling in binary FeCr alloys at 200 dpa. J. Nucl. Mater. 1995, 225, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Reese, E.R.; Ghamarian, I.; Marquis, E.A. Atom probe tomography characterization of ion and neutron irradiated Alloy 800H. J. Nucl. Mater. 2020, 543, 152598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Kim, B.; Yang, Y.; Field, K.; Gray, S.; Li, M. Microstructural evolution of neutron-irradiated T91 and NF616 to ∼4.3 dpa at 469 °C. J. Nucl. Mater. 2017, 493, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, L.; Huang, H.; Huang, Q.; Ren, C.; Lei, G.; Lin, J.; Fu, C.; Bai, J. Corrosion behavior of ion-irradiated SiC in FLiNaK molten salt. Corros. Sci. 2020, 163, 108229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Bowman, J.; Bachhav, M.; Kammenzind, B.; Smith, R.; Carter, J.; Motta, A.; Lacroix, E.; Was, G. Emulation of neutron damage with proton irradiation and its effects on microstructure and microchemistry of Zircaloy-4. J. Nucl. Mater. 2021, 557, 153281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasiak, T.; Jasiński, J.; Rzempołuch, J.; Woy, U.; Wilczopolska, M.; Mulewska, K.; Kowal, M.; Ciporska, K.; Kurpaska, Ł.; Jagielski, J. Effects of Fe2+ ion-irradiation on additively manufactured Inconel 617 alloy. J. Nucl. Mater. 2025, 615, 155978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhong, Y.; Long, B.; Li, L.; Qu, G.; Lu, S.; Yang, J. Corrosion of irradiated NbMoVCr coatings in lead-bismuth eutectic. Corros. Sci. 2024, 237, 112331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de los Reyes, M.; Edwards, L.; Kirk, M.A.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Lu, K.T.; Lumpkin, G.R. Microstructural Evolution of an Ion Irradiated Ni-Mo-Cr-Fe Alloy at Elevated Temperatures. Mater. Trans. 2014, 55, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, W.; He, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, R.; Zhou, X. Defects evolution and element segregation of Ni-Mo-Cr alloy irradiated by 30 keV Ar ions. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2020, 52, 1749–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, M.; Maksimkin, O.; Osipov, I.; Garner, F. Anomalously large deformation of 12Cr18Ni10Ti austenitic steel irradiated to 55 dpa at 310 °C in the BN-350 reactor. J. Nucl. Mater. 2009, 386–388, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porollo, S.I.; Shulepi, S.V.; Konobeev, Y.V.; Garner, F.A. Influence of silicon on swelling and microstructure in Russian stainless steel EI-847 irradiated to high neutron doses. J. Nucl. Mater. 2008, 378, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiyaremye, F.; Rouland, S.; Radiguet, B.; Cuvilly, F.; Klaes, B.; Tanguy, B.; Malaplate, J.; Domain, C.; Goncalves, D.; Abramova, M.M. Microstructural evolution of neutron irradiated ultrafine-grained austenitic stainless steel. J. Nucl. Mater. 2008, 607, 155710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Material | Type of Reactor for Which Material Is Specifically Engineered | Radiation Damage to Material (dpa) | Changes Observed in Material after Irradiation | Irradiation Temperature | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | W-10 at.% Re alloy | SFR | 8.6 | Coherent, semicoherent, and possibly incoherent precipitates of the σ phase. | 575–675 °C | [109] |

| 2. | W-25 at.% Re alloy | SFR | 2.8 | Coherent, semicoherent, and possibly incoherent precipitates of the σ phase. | 500 °C | [110] |

| 3. | UHP 304 SS | SFR | 20 | No evidence of He bubbles, voids, or precipitates. Fine-scale defects observed. | 320 °C | [111] |

| 4. | 316 SS | SFR | 20 | No precipitates, cavities, or voids. | 320 °C | [111] |

| 5. | 316 SS | PWR | 33 | No precipitates or voids. Presence of nanocavities. | 290 °C | [111] |

| 6. | 316 SS | PWR | 70 | A low density of precipitation. Presence of nanocavities. | 315 °C | [111] |

| 7. | EI-847 | SFR | 73–83 | Large levels of void swelling. Pronounced embrittlement. | 335–365 °C | [112] |

| 8. | Austenitic alloys (Fe-15Cr-16Ni and Fe-15Cr-16Ni-0.25Ti) | SFR | <1 to ~60 | Pronounced reduction in the transient regime of void swelling. | 400 °C | [113] |

| 9. | AISI 304 SS | SFR | 14–17 | Swelling. | 370–385 °C | [114] |

| 10. | AM 316L SS | LWR | 2 | Unstable plastic deformation (i.e., necking). No embrittlement. | 300 °C | [115] |

| 11. | Ti-based MAX phases | LWR | 2, 10 | Dislocation lines and loops, cavities, and stacking faults. Phase decomposition and segregation. | 1000 °C | [116] |

| 12. | IG-110 graphite | HTGR | up to 1.5 | Reduction in thermal conductivity. | 550–1150 °C | [117] |

| 13. | PCEA graphite | HTGR | Up to 12 | Dimensional changes (crystallite shrinkage in the a-direction). | 1300–1500 °C | [118] |

| 14. | GraphNOL N3M graphite | HTGR | 28.4 | Reduction in thermal conductivity. | 600 °C | [119] |

| 15. | Alloy 625 | LWR | 1 | Greater ductility. | 400 °C | [120] |

| 16. | FeCrAl alloys | LWR | 0.3, 0.8 | Dislocation loop formation. | 335–360 °C | [121] |

| 17. | SiC | LWR | 1 | No void swelling. Formation of point defects. | 1100 °C | [122] |

| 18. | Hexoloy SA | LWR | 1 | Formation of helium bubbles on the grain boundaries. | 1100 °C | [122] |

| 19. | Fe-Cr alloys | SFR | 200 | Swelling. Precipitation. | 425 °C | [123] |

| 20. | Alloy 800H | BWR PWR MSR | 17 | Formation of Al and Ti co-clusters, a high density of dislocation loops, and formation of carbides. | 385 °C | [124] |

| 21. | NF616 | LWR | 4.28 | Development of dislocation loops. | 469 °C | [125] |

| 22. | T91 | LWR | 4.36 | Development of dislocation loops. Formation of small cavities. | 469 °C | [125] |

| 23. | SiC | MSR | 3 | Amorphization. | RT | [126] |

| 24. | Zircaloy-4 | PWR | 17 | Formation of precipitates. Localized Fe redistribution. | 270 °C | [127] |

| 25. | Inconel 617 | HTGR MSR SFR LFR | 1 | Presence of defect clusters. | RT | [128] |

| 26. | NbMoVCr coatings | LFR | 80 | Formation of dislocation loops. No voids. Desegregation of Cr and V. Facilitation of intergranular corrosion. | 550 °C | [129] |

| 27. | Ni-Mo-Cr-Fe alloy | MSR | 5 | Formation and annihilation of point defect clusters. | 700 °C | [130] |

| 28. | Ni-Mo-Cr alloy | MSR | 1.38 and 2.76 | Formation of black dots that grow with increasing dose. | RT | [131] |

| 29. | Ni-Mo-Cr alloy | MSR | 13.8 and 27.6 | Pea-shaped dislocation loops, polygon dislocation networks, and large loops. Significant Mo depletions at dislocation lines and grain boundaries. | RT | [131] |

| 30. | 12Cr18Ni10Ti SS | SFR | 55 | A moving wave of plastic deformation at 20 °C results in very high values of engineering ductility. | 310 °C | [132] |

| 31. | EI-847 | SFR | up to 49 | Void swelling, reduced with silicon concentration. | 485–550 °C | [133] |

| 32. | 316 SS | LWR | up to 3.9 | Frank loops, cavities, Mo-Cr carbides, radiation-induced element segregation, and increase in grain size. | ~365 °C | [134] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chmielewska-Śmietanko, D.; Sartowska, B. Emerging Issues of Corrosion in Nuclear Power Plants: The Case of Small Modular Reactors. Energies 2025, 18, 6376. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246376

Chmielewska-Śmietanko D, Sartowska B. Emerging Issues of Corrosion in Nuclear Power Plants: The Case of Small Modular Reactors. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6376. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246376

Chicago/Turabian StyleChmielewska-Śmietanko, Dagmara, and Bożena Sartowska. 2025. "Emerging Issues of Corrosion in Nuclear Power Plants: The Case of Small Modular Reactors" Energies 18, no. 24: 6376. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246376

APA StyleChmielewska-Śmietanko, D., & Sartowska, B. (2025). Emerging Issues of Corrosion in Nuclear Power Plants: The Case of Small Modular Reactors. Energies, 18(24), 6376. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246376