Review of DC Microgrid Design, Optimization, and Control for the Resilient and Efficient Renewable Energy Integration

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Critical review of different DC microgrid architectures and their situational analysis with respect to control complexity and reliable operability.

- How different control strategies can help achieve the realization of flexible DC microgrids while satisfying safety and operational standards as set by different organizations such as IEEE, IEC, and EMerge.

- Which typical standards must be kept in view by the designer while designing a DC microgrid?

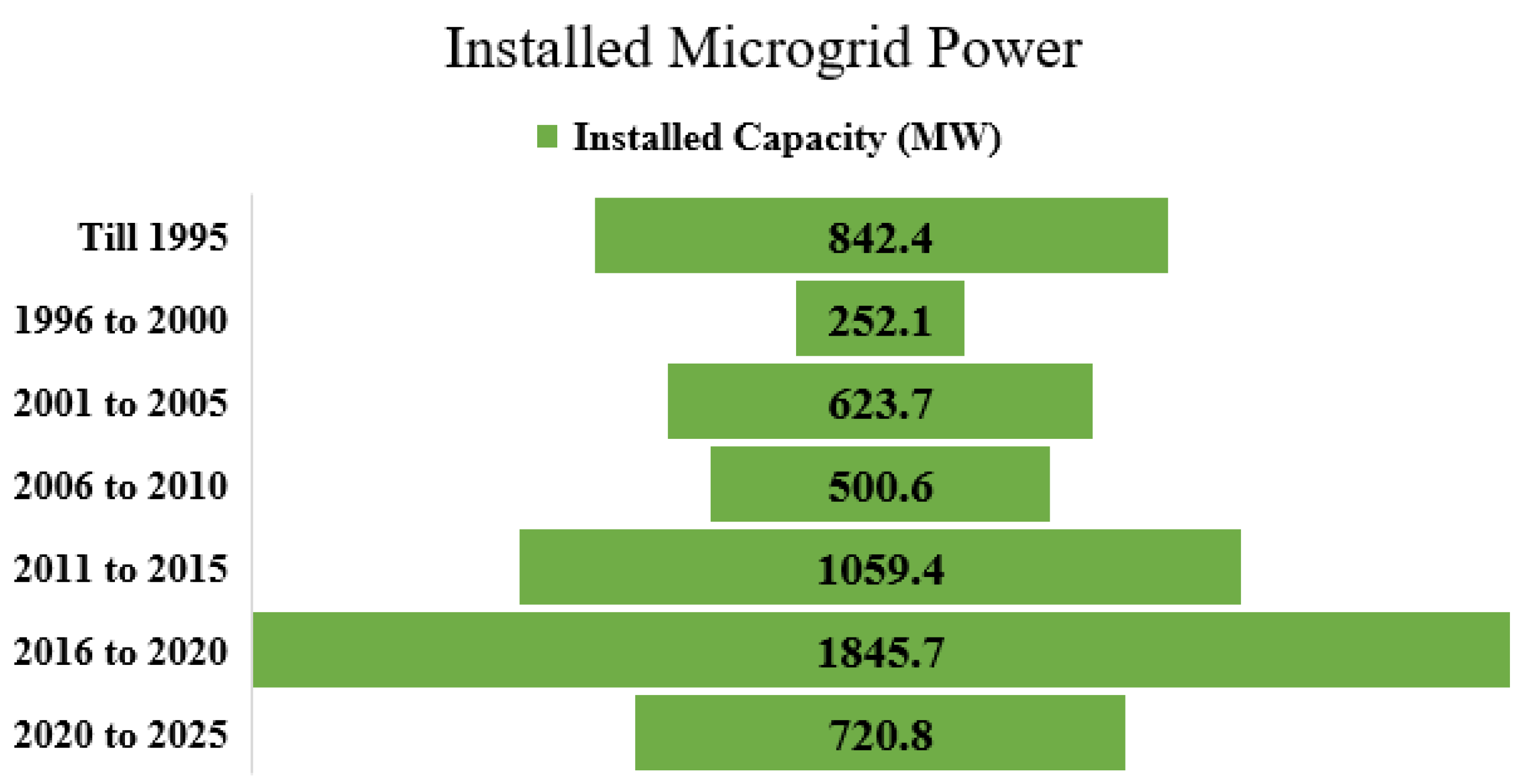

2. DCMG Components, Configurations, and Global Market

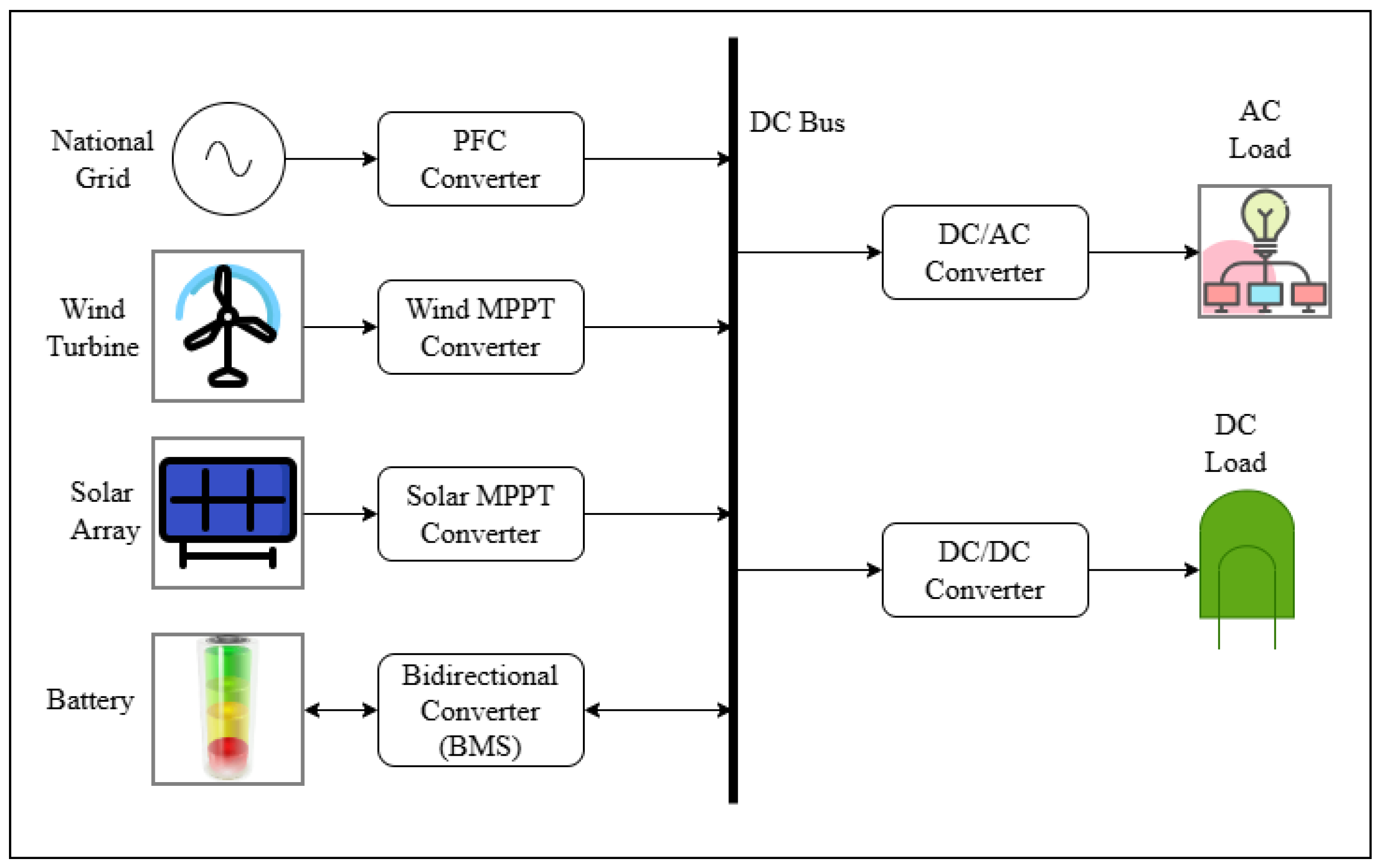

2.1. DC Microgrid Building Blocks

2.1.1. Functions of Power Converters

- Voltage Interfacing: A moderately to highly complex DC microgrid needs to operate on different levels at different ports. For instance, if a DC microgrid integrates multiple PV systems operating at different voltage levels while the common DC bus is designed to operate at 110 V, a battery system at 48 V, and a 24 V DC load, the DC/DC converters, like buck/boost converters, can easily bridge energy flow at these different voltage levels [9].

- Power Flow Control: Power flow is one of the major tasks performed by all power converters. The control and amount of power flow are actively regulated by varying the duty cycles of converter switches in response to feedback control signals. The control systems implemented for different converters ensure the controlled flow of power, which is only possible if the entire system is robustly stable [10,11].

- Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT): Variable power generation is the core characteristic of all renewable energy sources, like PV, wind, tidal, etc. To utilize the available energy to the fullest, the converter connected to the renewable energy source must be operated to track the maximum available power and ensure that the power flows towards the shared bus, and hence towards energy storage devices and loads. This goal is achieved using different MPPT algorithms. Currently, there are many such algorithms in the literature. The boost converter is the most widely used MPPT controller. Some designers also prefer the use of buck converters or buck-boost converters [12,13].

- Bidirectional Operation for Energy Storage: These converters are the heart of modern DC microgrids for the integration of energy systems. The maximum cost–benefit can only be achieved if an energy storage system is integrated. The integration of energy storage systems makes the overall system flexible, stable, and scalable. Bidirectional converters are created by combining buck and boost converters, with one controlling the flow of power in the opposite direction with respect to the other converter [14].

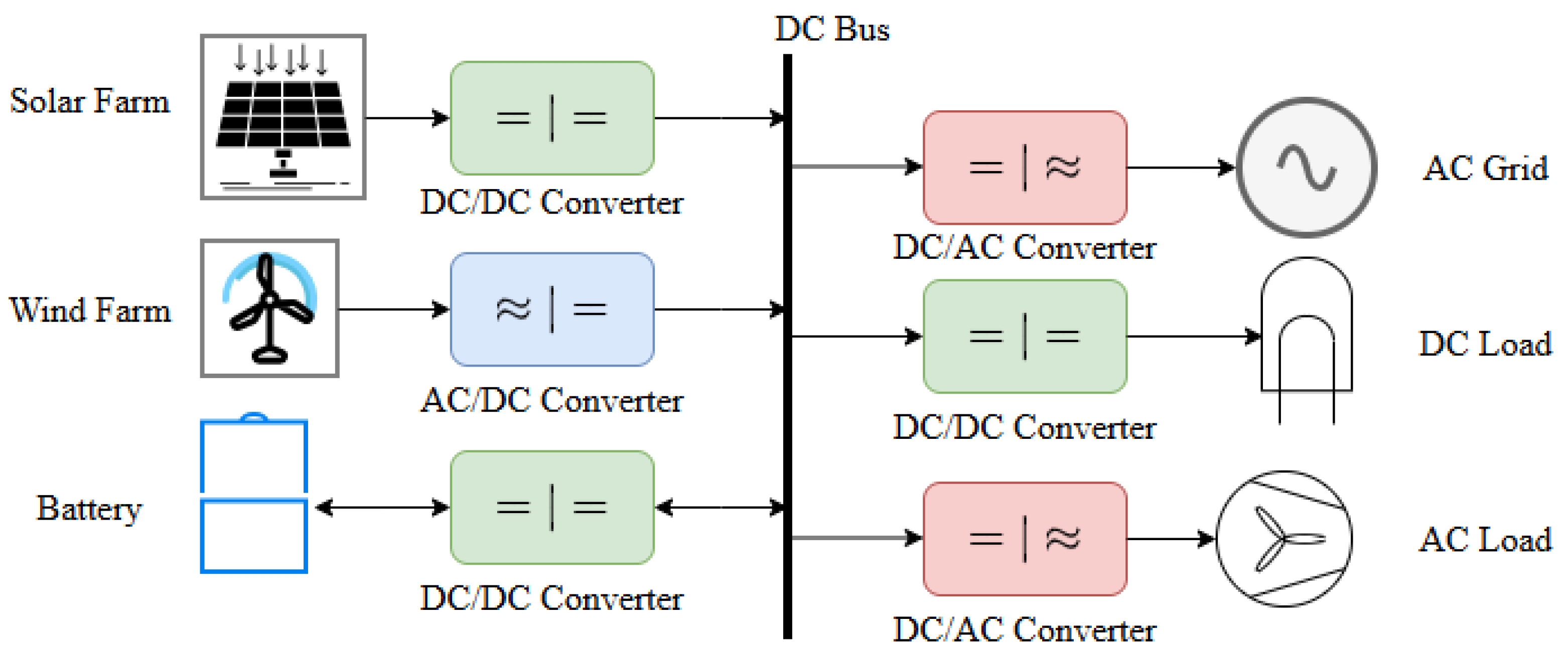

- AC to DC Conversion (Rectification): This function is necessary for integrating the national grid as a power source into DC microgrid operations. It also enables the integration of variable-frequency sources, such as wind and tidal turbines. Rectification can help optimize the sizing of resources such as batteries, solar panels, and other components to achieve optimal implementation and running costs.

- DC to AC Conversion (Inversion): This function is required if an AC load or AC grid is to be supplied power from a DC microgrid. Thus, this function provides greater flexibility, as the DC microgrid not only drives DC loads but also serves AC loads. But the design of control systems for inverters poses a real challenge for energy engineers because the control system for the inversion process is comparatively complex compared with those for DC-DC converters.

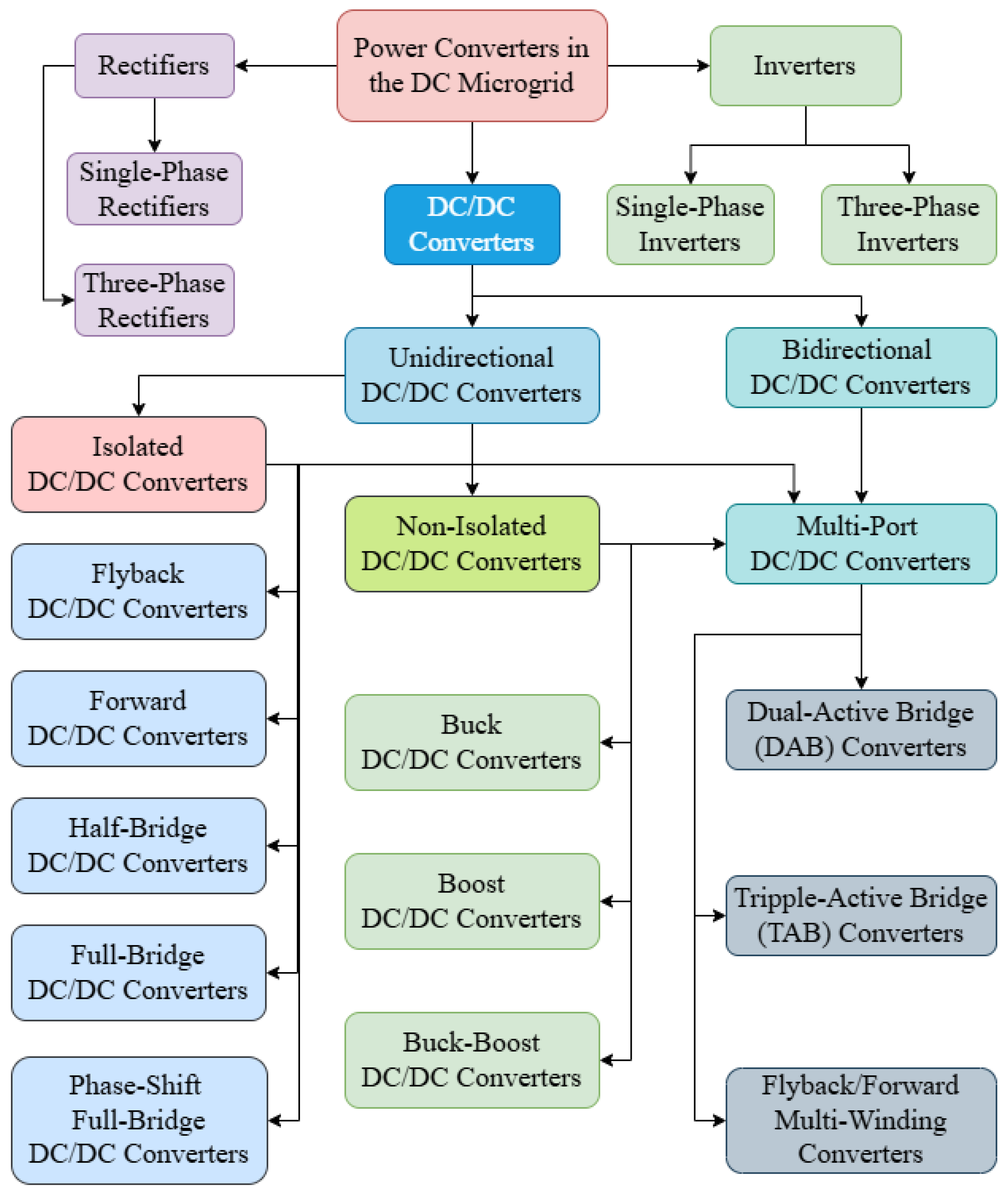

2.1.2. Converter Topologies—DC/DC Converters

2.1.3. Converter Topologies—AC/DC and DC/AC Converters

2.1.4. Converters for Bipolar DC Microgrids

2.1.5. Impact of Wide Bandgap Semiconductors on Converter Performance

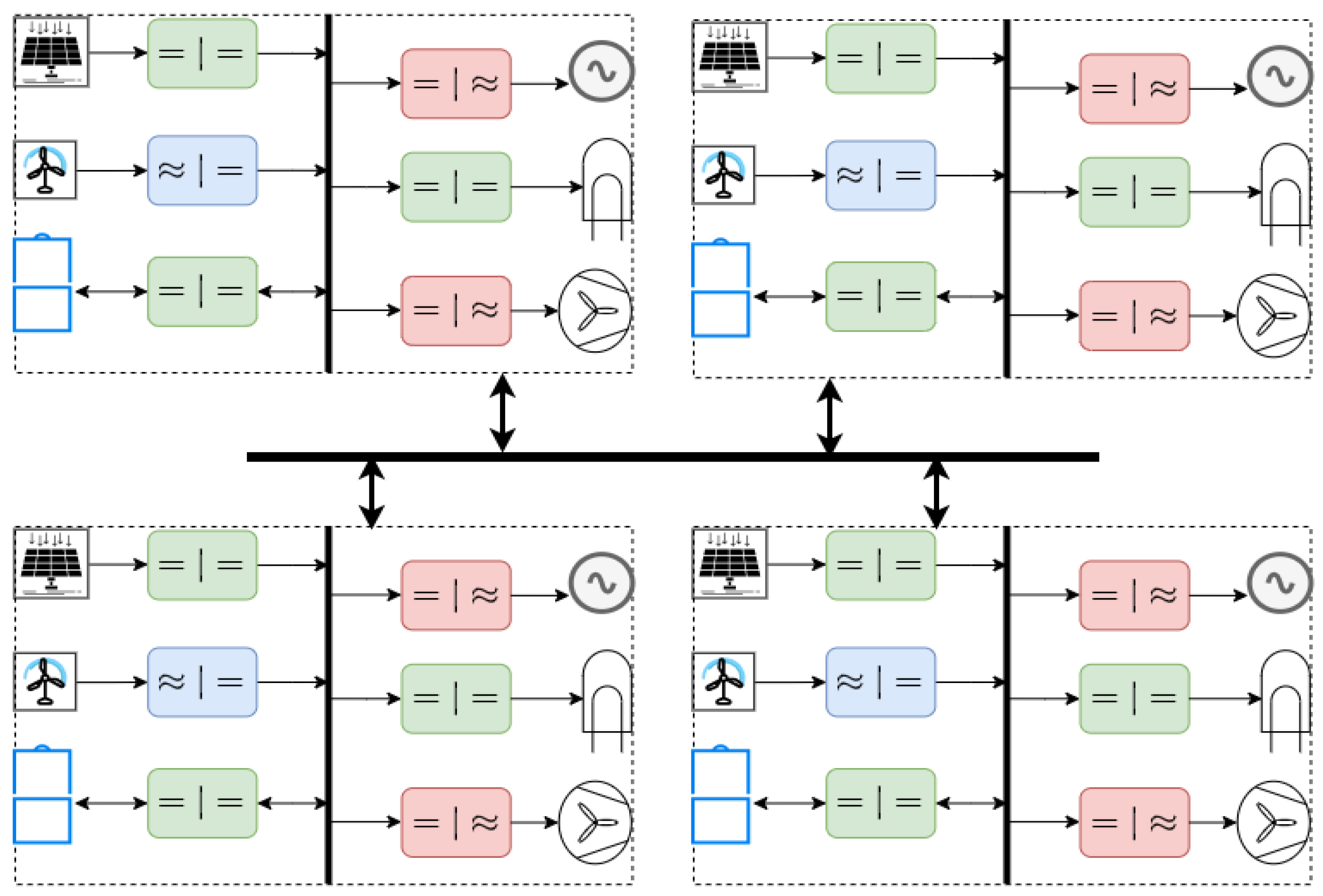

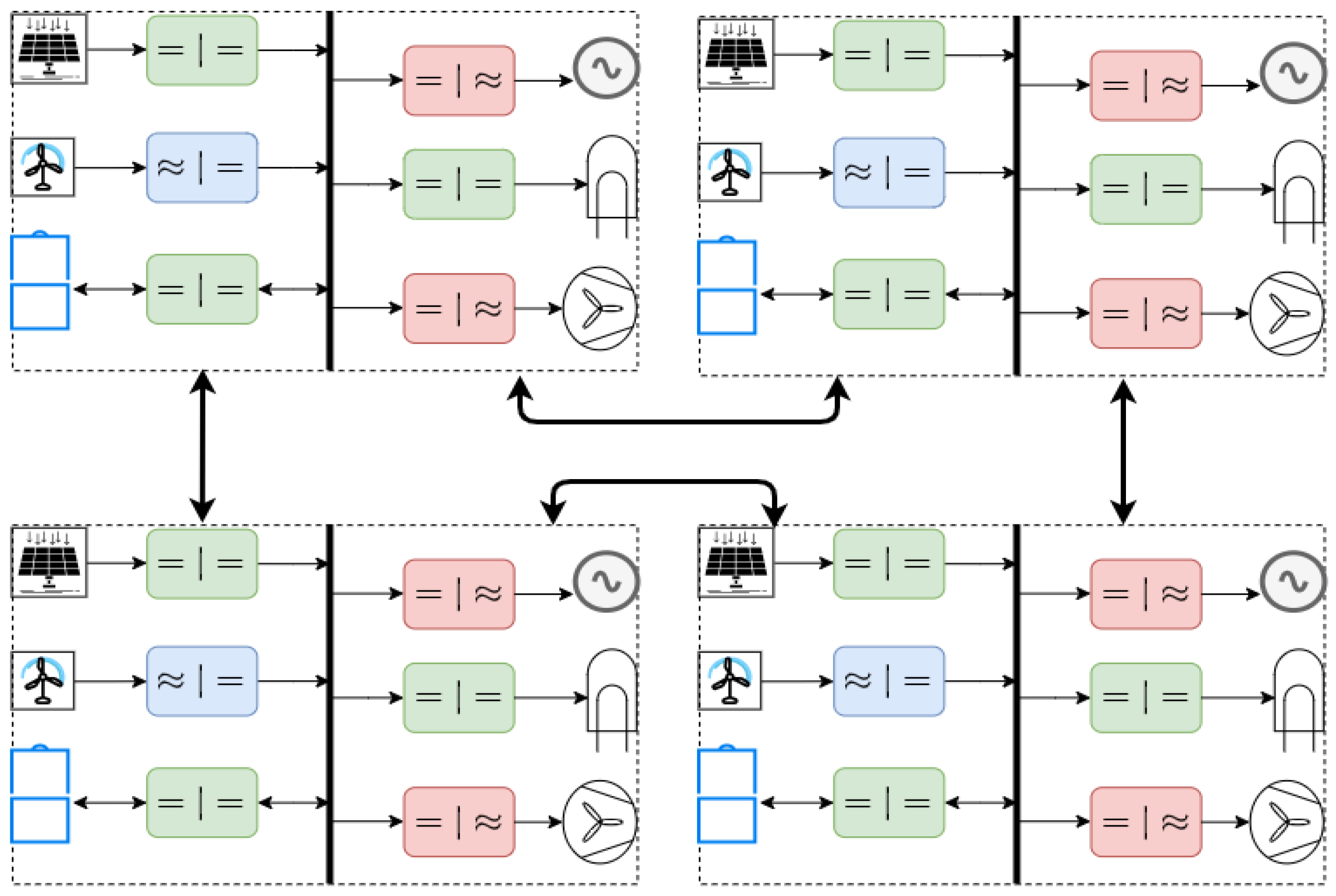

2.2. Architectural Topologies of a DC Microgrid

2.2.1. Single Bus Topology

2.2.2. Radial Topology

2.2.3. Ring or Loop Topology

2.2.4. Mesh and Interconnected Topologies

2.3. Advantages of DC Microgrid Architectures

2.3.1. Quantitative Efficiency and Comparative Advantage

- A hardware prototype comparison demonstrated that a DC system could achieve a 15% increase in efficiency over an equivalent AC system [2].

- A comparative installation by Bosch in Charlotte, North Carolina, where a DC microgrid was installed alongside an equivalent AC system for direct comparison, showed that the DC system utilized the energy from its PV array with 8% more efficiency [24].

- A comprehensive simulation study conducted by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and Bosch, modeling various commercial building types across different U.S. climates, concluded that the Bosch DC microgrid architecture uses locally generated PV energy 6% to 8% more efficiently than traditional AC systems [2]

- For specific high-density DC load applications like data centers, the potential savings are even more dramatic. Studies from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory have indicated that data centers could reduce energy consumption by up to 28% by transitioning to a DC microgrid architecture [25].

2.3.2. Control Simplicity, Stability, and Integration of Energy Storage

2.3.3. The Hybrid AC/DC Approach: A Pragmatic Bridge to Future Grids

3. Intelligent Control and Management Systems

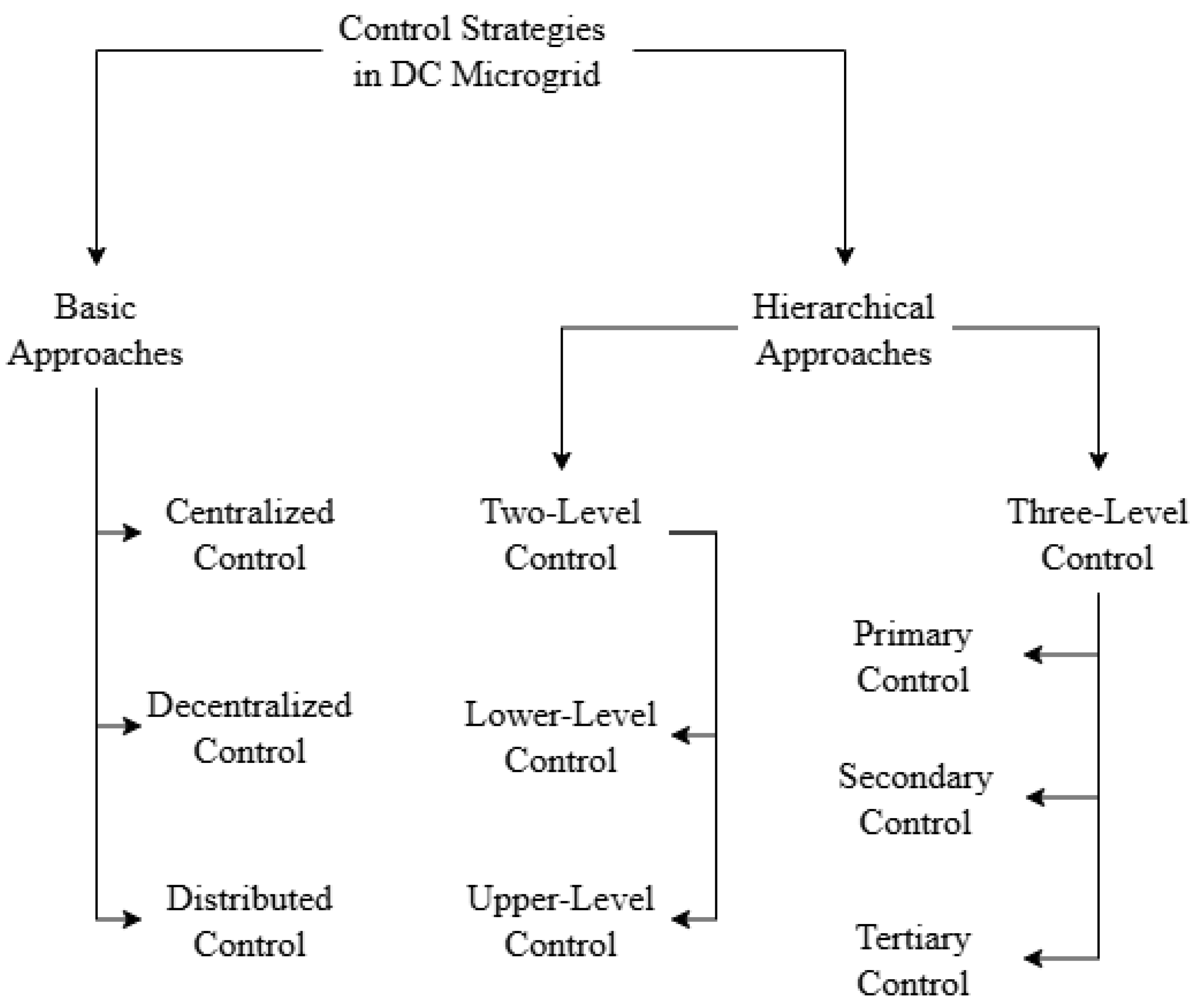

3.1. Hierarchical Control Frameworks for Coordinated Operation

3.1.1. Primary Control

3.1.2. Secondary Control

3.1.3. Tertiary Control

3.2. Centralized, Decentralized, and Distributed Control

- Enhanced Reliability: By eliminating the central controller and communication network as single points of failure, the system becomes more robust and resilient [38].

- Scalability and Modularity: New generators, loads, or storage units can be added to the system without needing to reprogram a central controller. The system can grow organically, which is a significant advantage in terms of cost and flexibility [38].

- Plug-and-Play (PnP) Capability: This is the goal of decentralized control. PnP functionality allows devices to be seamlessly connected to or disconnected from the microgrid, with the system automatically adapting to the change and reconfiguring its operation to maintain stability [39].

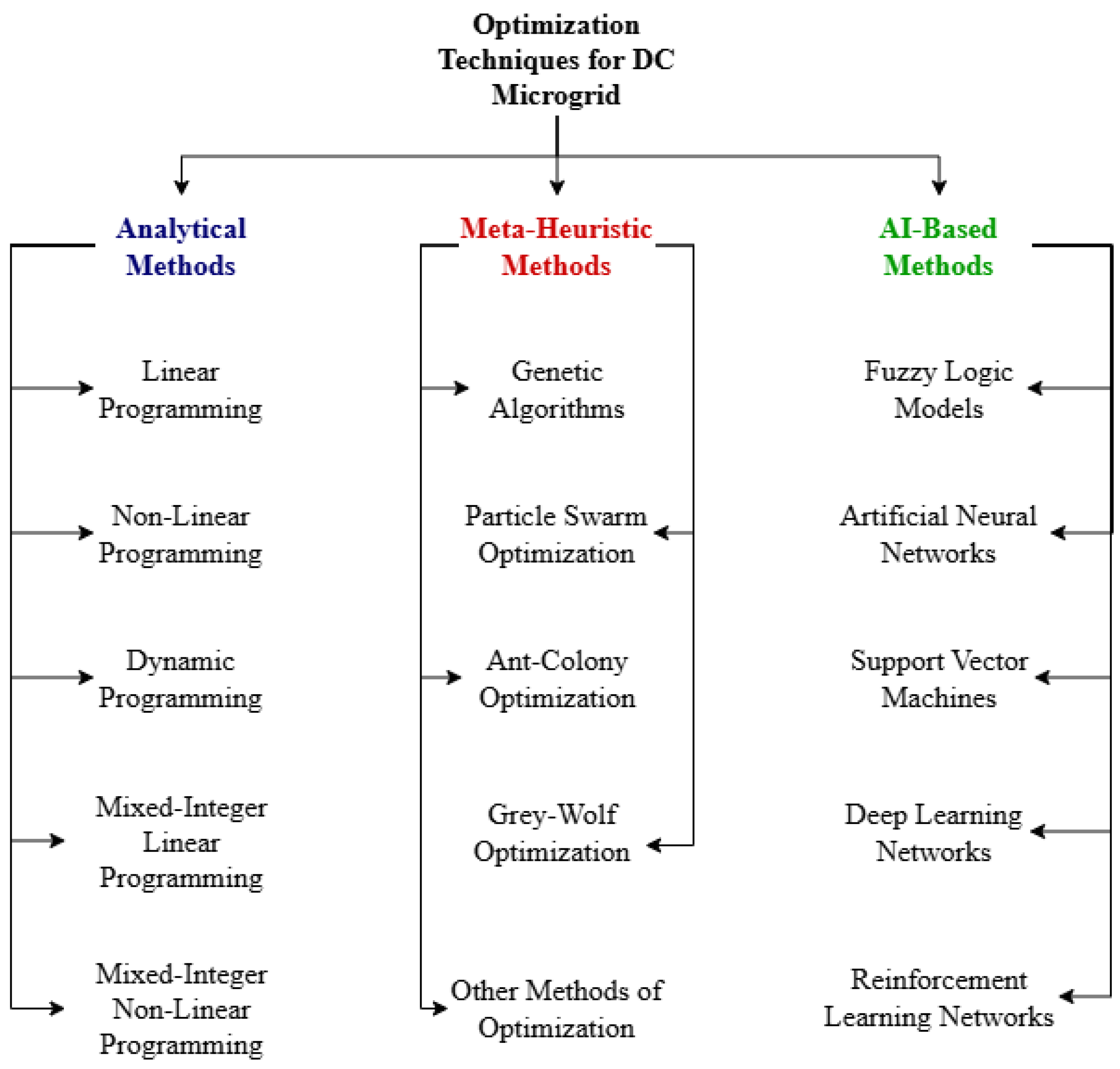

3.3. Optimization Techniques for Economic and Resilient Operation

3.3.1. Mathematical Programming

3.3.2. Heuristic and Meta-Heuristic Algorithms

3.3.3. Advanced and AI-Based Techniques

3.4. Fault Detection and Classification for Resilient Control

3.4.1. Fault Detection Issues

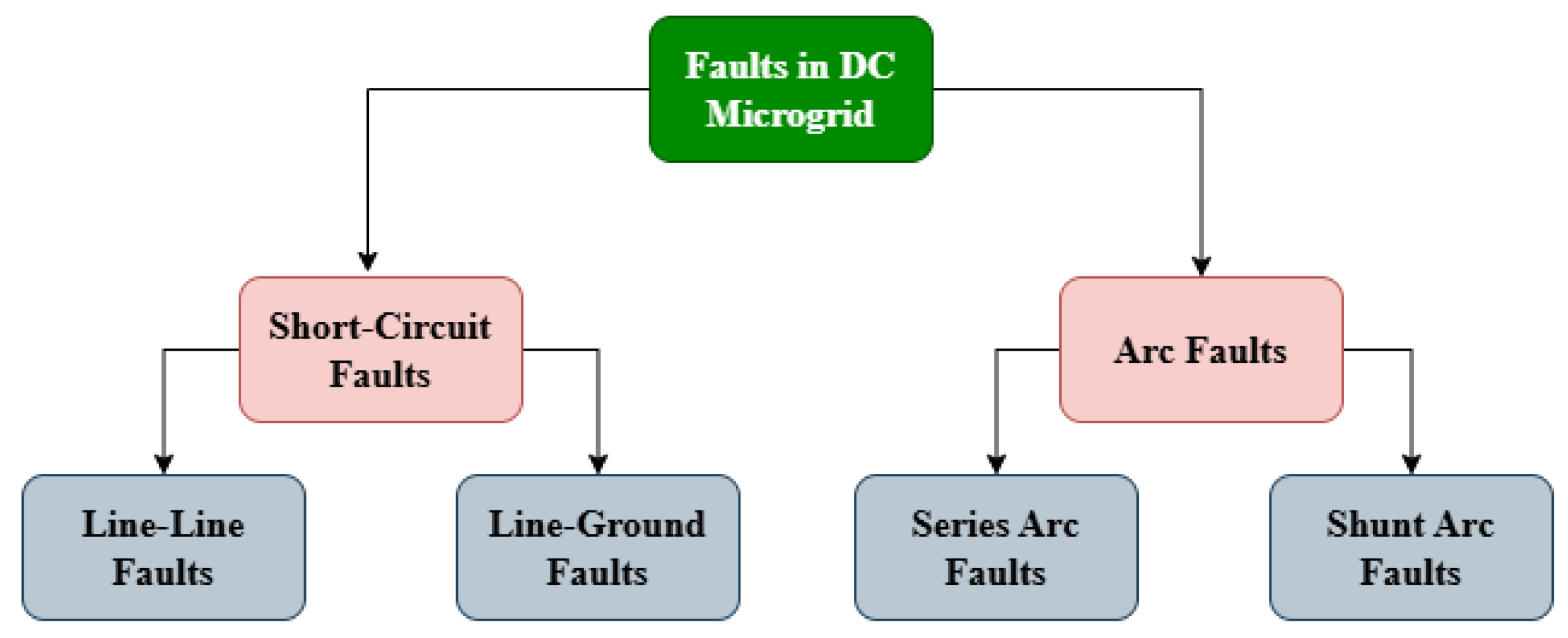

3.4.2. Types of Faults in DC Microgrid

3.5. State-of-the-Art Protection Schemes and Coordination Strategies

3.5.1. Adaptive Protection

3.5.2. Differential Protection

3.5.3. Transient-Based and Derivative Methods

- Voltage and Current Derivatives (dv/dt, di/dt): The rapid discharge of capacitors during a fault causes a sharp voltage-drop (dv/dt) and a sharp rise in current (di/dt). By monitoring these rates of change, a fault can be detected within microseconds, much faster than waiting for the current to reach a specific overcurrent threshold [52].

- Traveling Wave Protection: A fault inception generates high-frequency electromagnetic waves that travel along the power lines away from the fault location. Sensors can detect the arrival time and polarity of these “traveling waves” to very quickly detect and even locate the fault with high precision [53].

3.5.4. Machine Learning (ML) Approaches

3.6. Advanced DC Circuit Breaker Technologies

3.6.1. Solid-State Circuit Breakers (SSCBs)

3.6.2. Hybrid Circuit Breakers (HCBs)

3.6.3. Z-Source Breakers

4. Reliability, Standardization, and Future Outlook

4.1. Methodologies for Rigorous Reliability Assessment

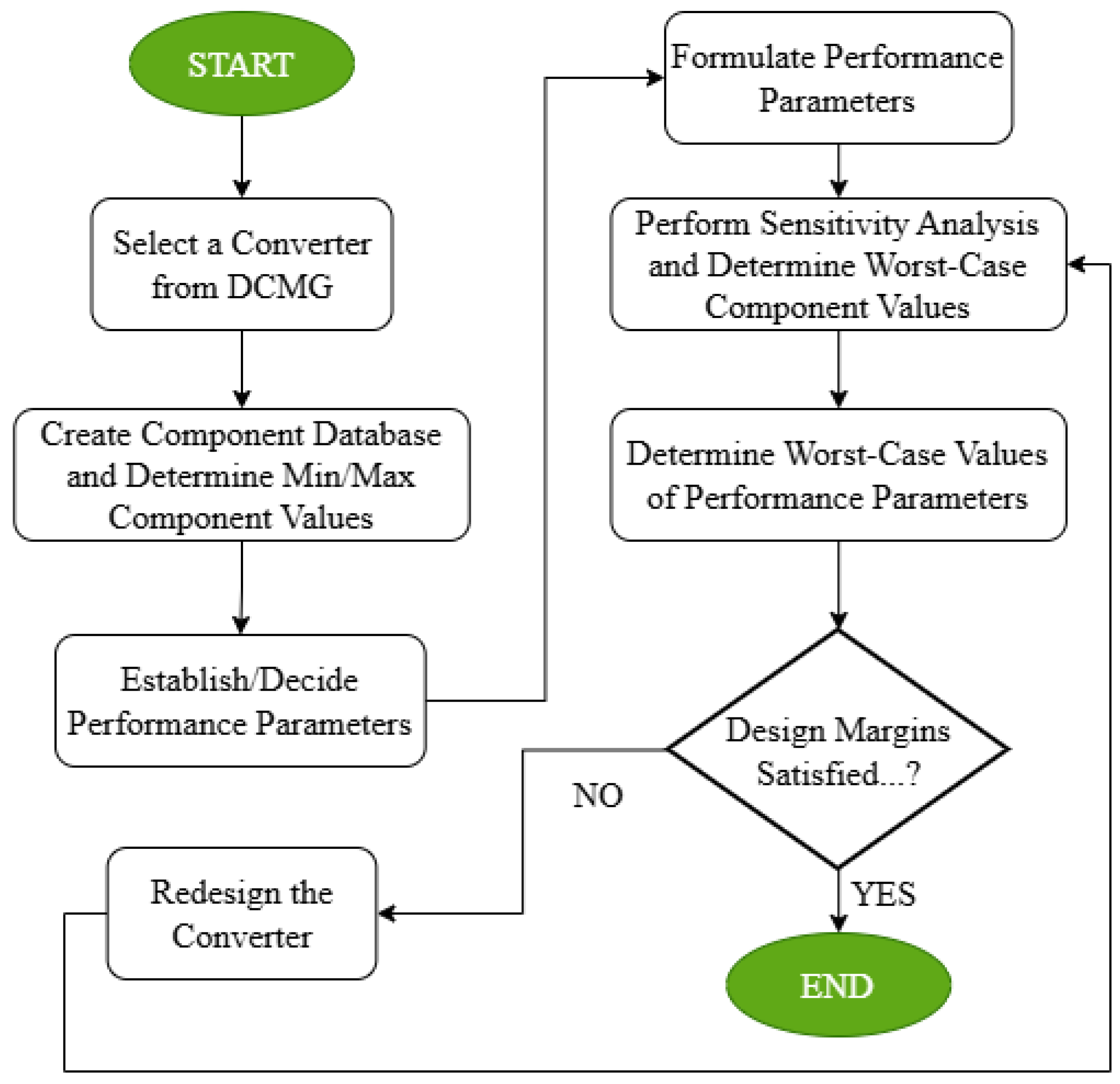

4.1.1. Worst-Case Circuit Analysis (WCCA)

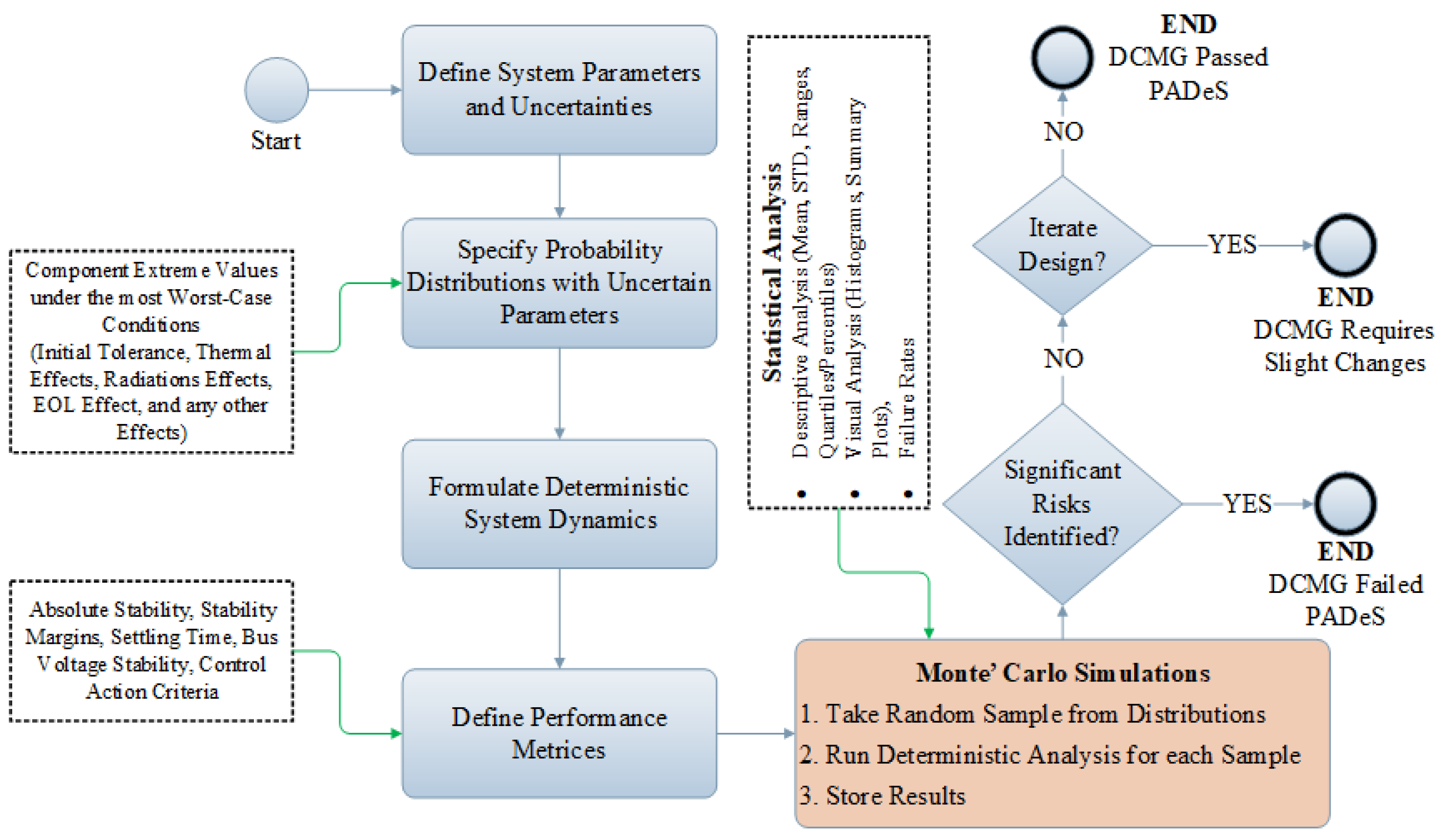

4.1.2. Probabilistic and Statistical Methods

4.1.3. Failure Modes, Effects, and Criticality Analysis (FMECA)

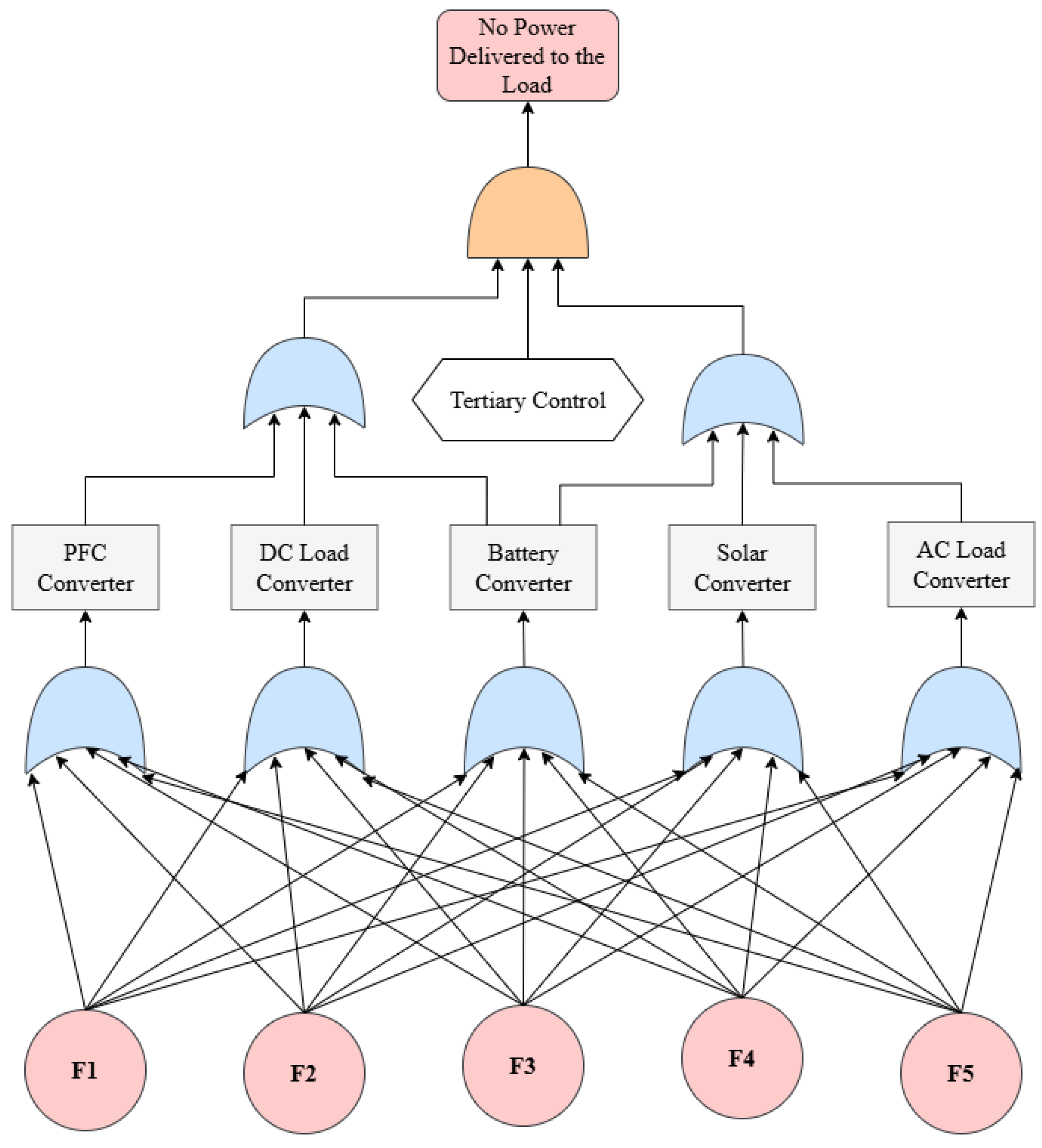

- F1: It can occur if the buck converter is driven from a rectifier converting a variable frequency source to DC. Since the input voltage is usually filtered using special LC filters, its occurrence is less likely. It is easily detected by active-sensing systems embedded in control ICs, and its severity will be low because it can only damage the PCB on which the converter is implemented [67].

- F2: Capacitors and inductors are used to filter non-DC power in various power converters. Excessive voltage across a capacitor caused by overcharging can damage it, which is the most common cause of failure. The effects of equivalent series resistance (ESR) and high dv/dt can also harm a capacitor. Excessive current—caused by DC resistance and di/dt—can damage an inductor. If the WCCA’s conservative guidelines are followed, the likelihood of these issues occurring will be minimized. They often go unnoticed and are usually not protected, which can lead to mild symptoms [68,69].

- F4: Primary control circuits are usually accomplished using specialized control ICs whose functionalities are guaranteed by their manufacturers. Yet these ICs require external passive components to configure the feedback network and control loops. Therefore, their occurrence and non-detection are less likely. But if a fault occurs that could be highly damaging to the entire circuit, or even it can cause injury to nearby people [72,73].

- F5: Secondary control is usually applied to implement efficient energy flow control. Therefore, the occurrence of this fault is less likely because the energy flow is continuously measured to force dynamic control actions. But its failure could be highly severe to the system and the people nearby [74].

4.1.4. Fault-Tree Analysis (FTA)

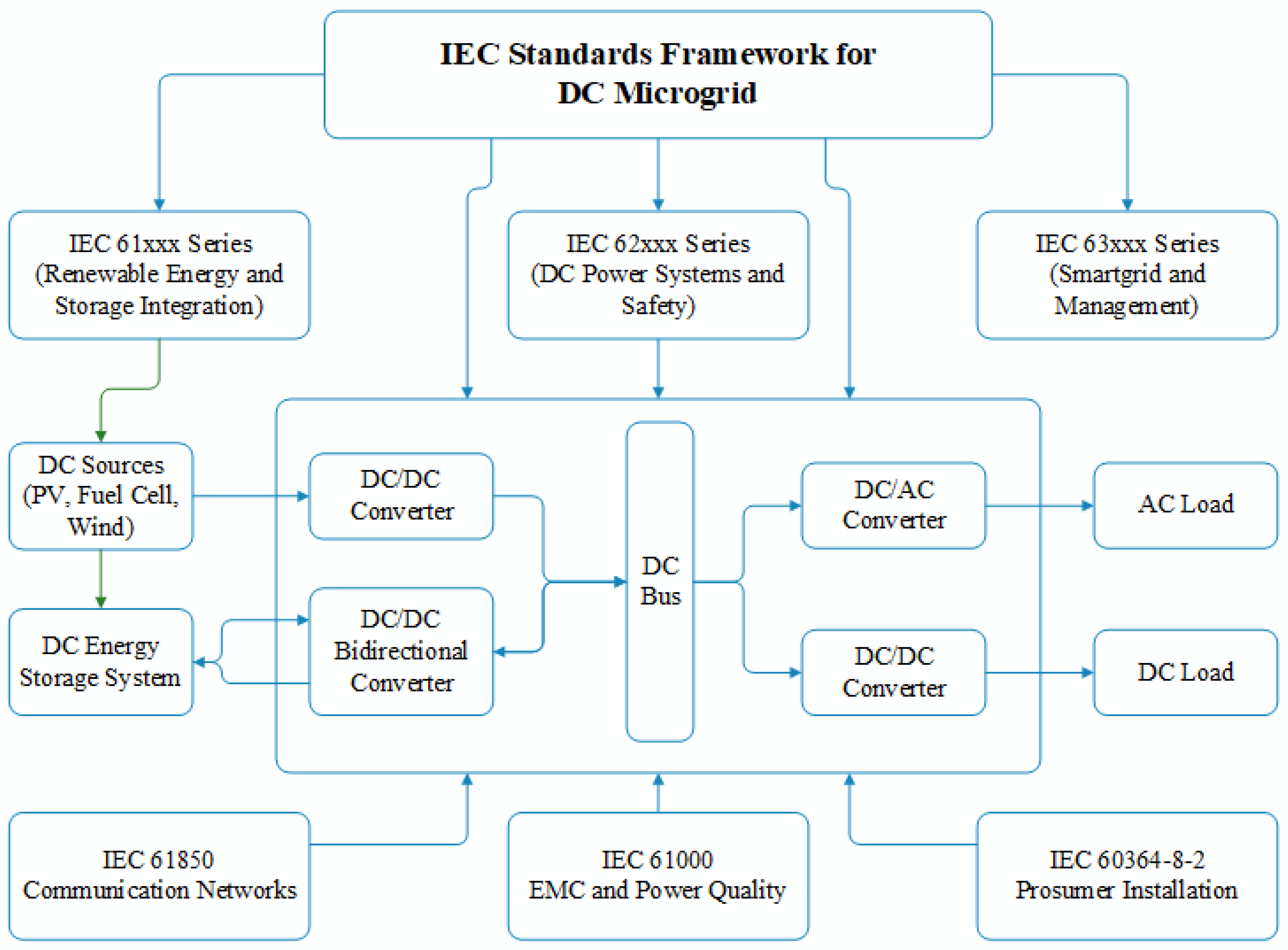

4.2. Standards Applicable to DC Microgrid

4.2.1. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC)

4.2.2. EMerge Alliance

4.2.3. IEEE Standards

4.2.4. Military Standards (MIL-STD)

4.3. Persisting Challenges and Future Research Trajectories

4.3.1. Cost-Effective Protection

4.3.2. Standardization and Interoperability

4.3.3. Stability in Low-Inertia Systems

4.3.4. Advanced Control and Optimization

4.3.5. Network Security Issues

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cucuzzella, M.; Scherpen, J.M.A.; Machado, J.E. Microgrids control: AC or DC, that is not the question. EPJ Web Conf. 2024, 310, 00015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, D.A.; Ali, K.H.; Memon, A.A.; Ansari, J.A.; Badar, J.; Alharbi, M.; Banatwala, A.Z.; Kumar, M. Comparative analysis and implementation of DC microgrid systems versus AC microgrid performance. Front. Energy Res. 2024, 12, 1370547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, V.F.; Pires, A.; Cordeiro, A. DC Microgrids: Benefits, Architectures, Perspectives and Challenges. Energies 2023, 16, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.; Liu, Y.; Guo, C.; Zhou, N.; Wang, Q.; Kang, W.; Vasquez, J.C.; Guerrero, J.M. Power quality of DC microgrid: Index classification, definition, correlation analysis and cases study. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 156, 109782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, A.A.; Edpuganti, A.; Khadkikar, V.; Zeineldin, H. A Novel Simultaneous AC and DC Charging Scheme for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 39, 1534–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Paja, C.A.; Serna-Garcés, S.I.; Saavedra-Montes, A.J. Battery Power Interface to Mitigate Load Transients and Reduce Current Harmonics for Increasing Sustainability in DC Microgrids. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adegboyega, A.W.; Sepasi, S.; Howlader, H.O.R.; Griswold, B.; Matsuura, M.; Roose, L.R. DC Microgrid Deployments and Challenges: A Comprehensive Review of Academic and Corporate Implementations. Energies 2025, 18, 1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanda, S.; Pattanayak, B.; Barik, S.K.; Senapati, R.N. DC Microgrid, Faults and Detection Techniques: A Comprehensive Review. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Recent Trends in Computer Science and Technology, ICRTCST 2024—Proceedings, Jamshedpur, India, 15–16 April 2024; pp. 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, S.; Iqbal, M.S.; Adnan, M.; Akbar, M.A.; Bermak, A. Multilevel Inverters Design, Topologies, and Applications: Research Issues, Current, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 149320–149350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lin, P.; Zhu, M.; Chen, W.; DU, L.; Lu, Z.; Wu, L. Modular Multi-Level Multi-Line DC Power Flow Controller for Meshed HVDC Grids Enabled by Decentralized Power Exchange Mechanism. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmokadam, S.; Suresh, M.; Mathew, R. Power flow control strategy for prosumer based EV charging scheme to minimize charging impact on distribution network. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 3794–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guanghua, L.; Siddiqui, F.A.; Aman, M.M.; Shah, S.H.H.; Ali, A.; Soomar, A.M.; Shaikh, S. Improved maximum power point tracking algorithms by using numerical analysis techniques for photovoltaic systems. Results Eng. 2024, 21, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, A.; Javed, M.Y.; Shahid, K.; Mussenbrock, T. Optimized Maximum Power Point Tracking for Hybrid PV-TEG Systems Using an Improved Water Cycle Algorithm. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 149343–149360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, S.S.; Sharma, K.K. Power enhancement in distributed system to control the bidirectional power flow in electric vehicle. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 54673–54698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahale, S.; Das, A.; Pindoriya, N.M.; Rajendran, S. An overview of DC-DC converter topologies and controls in DC microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2017 7th International Conference on Power Systems, ICPS 2017, Pune, India, 21–23 December 2017; pp. 410–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saafan, A.A.; Khadkikar, V.; El Moursi, M.S.; Zeineldin, H.H. A New Multiport DC-DC Converter for DC Microgrid Applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, V.F.; Cordeiro, A.; Roncero-Clemente, C.; Rivera, S.; Dragicevic, T. DC–DC Converters for Bipolar Microgrid VoltageBalancing: A Comprehensive Review of Architectures and Topologies. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2023, 11, 981–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutwald, B.; Reichenstein, T.; Barth, M.; Franke, J. Measurement Technology in Industrial Low Voltage DC grids—Requirements and Selection Procedure. In Proceedings of the 2024 1st International Conference on Production Technologies and Systems for E-Mobility (EPTS), Bamberg, Germany, 5–6 June 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Rahman, S.U.; Sarwar, R. Impact of Bidirectional Semiconductor Devices on DC and Hybrid Microgrids Enhanced by Wide Bandgap Materials. Eng. Rep. 2025, 7, e70197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuyyuru, U.; Maiti, S.; Chakraborty, C.; Pal, B.C. A Series Voltage Regulator for the Radial DC Microgrid. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2019, 10, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, R.K.; Tripathy, M. Enhancing Stability and Performance of DC Microgrid: A Coordinated Impedance Reshaping Controller Design Approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 7797–7806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binqadhi, H.; Hamanah, W.M.; Shafiullah, M.; Alam, M.S.; AlMuhaini, M.M.; Abido, M.A. A Comprehensive Survey on Advancement and Challenges of DC Microgrid Protection. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ismail, F.S. DC Microgrid Planning, Operation, and Control: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 36154–36172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fregosi, D.; Ravula, S.; Brhlik, D.; Saussele, J.; Frank, S.; Bonnema, E.; Scheib, J.; Wilson, E. A Comparative Study of DC and AC Microgrids in Commercial Buildings Across Different Climates and Operating. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE First International Conference on DC Microgrids (ICDCM), Atlanta, GA, USA, 7–10 June 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraj, A.; Tranchero, M. How Does Data Access Shape Science? The Impact of Federal Statistical Research Data Centers on Economics Research. 1 June 2023. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=4483672 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Vasantharaj, S.; Indragandhi, V.; Subramaniyaswamy, V.; Teekaraman, Y.; Kuppusamy, R.; Nikolovski, S. Efficient Control of DC Microgrid with Hybrid PV—Fuel Cell and Energy Storage Systems. Energies 2021, 14, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ismail, F.S. A Critical Review on DC Microgrids Voltage Control and Power Management. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 30345–30361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unamuno, E.; Barrena, J.A. Hybrid ac/dc microgrids-Part I: Review and classification of topologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S. Comparative Analysis of ac Coupled and dc Coupled Microgrids: Analyzing Electrical Performances and Economics. Cal Poly Humboldt Theses and Projects. January 2024. Available online: https://digitalcommons.humboldt.edu/etd/788 (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Nagpal, M. Empowering Energy Evolution: The rise of microgrid autonomy [Technology Leaders]. IEEE Electrif. Mag. 2024, 12, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.A.; Prabha, N.A. A comprehensive review of DC microgrid in market segments and control technique. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, N.; Mobarrez, M.; Bhattacharya, S. A Review and Modeling of Different Droop Control Based Methods for Battery State of the Charge Balancing in DC Microgrids. In Proceedings of the IECON 2018—44th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Washington, DC, USA, 21–23 October 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Zamora, R.; Sheina, A. A Comprehensive Review in DC microgrids: Topologies, Controls and Future Trends. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Energy Technologies for Future Grids, ETFG 2023, Wollongong, Australia, 3–6 December 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargavi, K.M.; Jayalakshmi, N.S.; Gaonkar, D.N.; Shrivastava, A.; Jadoun, V.K. A comprehensive review on control techniques for power management of isolated DC microgrid system operation. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 32196–32228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, F.; Chen, K.; Lu, Q. Research on Adaptive Droop Control Strategy for a Solar-Storage DC Microgrid. Energies 2024, 17, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, L.; Wang, L.; Zhou, W.; Ge, X. Fuzzy Droop Control for SOC Balance and Stability Analysis of DC Microgrid with Distributed Energy Storage Systems. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 12, 1203–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, L.; Boudinet, C.; Ranaivoson, S.A.; Rabarivao, J.O.; Befeno, A.E.; Frey, D.; Alvarez-Hérault, M.-C.; Raison, B.; Saincy, N. Development of a DC Microgrid with Decentralized Production and Storage: From the Lab to Field Deployment in Rural Africa. Energies 2022, 15, 6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibullah, A.F.; Padhilah, F.A.; Kim, K.-H.; de Lucas, C.H.; Prieto, D.R.; Rodriguez, N.F.G. Decentralized Control of DC Microgrid Based on Droop and Voltage Controls with Electricity Price Consideration. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Feng, W.; Nordman, B.; Gerber, D.; Li, Y.; Kang, J.; Hao, B.; Brown, R. Technology standards for direct current microgrids in buildings: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 211, 115278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukkarasu, G.S.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Jamei, E.; Horan, B.; Mekhilef, S.; Stojcevski, A. Role of optimization techniques in microgrid energy management systems—A review. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 43, 100899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Tobar, A.; Pavan, A.M.; Petrone, G.; Spagnuolo, G. A Review of the Optimization and Control Techniques in the Presence of Uncertainties for the Energy Management of Microgrids. Energies 2022, 15, 9114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehimehr, S.; Miraftabzadeh, S.M.; Brenna, M. A Novel Machine Learning-Based Approach for Fault Detection and Location in Low-Voltage DC Microgrids. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.H.; Badran, E.A.; Abdel-Rahman, M.H. Detect, Classify, and Locate Faults in DC Microgrids Based on Support Vector Machines and Bagged Trees in the Machine Learning Approach. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 139199–139224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, M.; Nor, N.B.M.; Shiekh, M.A.; Alharthi, Y.Z.; Shutari, H.; Majeed, M.F. A Review on Microgrid Protection Challenges and Approaches to Address Protection Issues. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 175278–175303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Mohanty, R.; Ghazvini, M.A.F.; Tuan, L.A.; Steen, D.; Carlson, O. A Review on Challenges and Solutions in Microgrid Protection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Madrid PowerTech, PowerTech 2021—Conference Proceedings, Madrid, Spain, 27 June–2 July 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Han, H.; Sun, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, H.; Zheng, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J. A Novel Fault Diagnosis Scheme Based on Local Fault Currents for DC Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2025, 40, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PrashanthKumar, H.K.; Dash, R.; Swain, S.C. Analyzing Line-Line Faults in DC Microgrids Through Discrete Wavelet Transform Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Smart Power Control and Renewable Energy, ICSPCRE 2024, Rourkela, India, 19–21 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.M.; Navarro, G.; Mahtani, K.; Platero, C.A. Double Line-to-Ground Faults Detection Method in DC-AC Converters. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 59, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P.; Mandal, R.K. Learning approach based DC arc fault location classification in DC microgrids. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2022, 208, 107874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsaeidi, S.; Dong, X.; Shi, S.; Wang, B. AC and DC Microgrids: A Review on Protection Issues and Approaches. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2017, 12, 2089–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.K.; Gangwar, T.; Choudhury, B.K.; Jena, P. Novel Differential Protection Strategy for Zonal DC Microgrid. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 2476–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sijo, A.; Quiroz, J.E.; Reno, M.J. DC Microgrid Protection: Review and Challenges. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326957897_DC_Microgrid_Protection_Review_and_Challenges (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Paruthiyil, S.K.; Bidram, A.; Aparicio, M.J.; Hernandez-Alvidrez, J.; Dow, A.R.R.; Reno, M.J.; Bauer, D. Travelling wave—Based fault detection and location in a real low—Voltage DC microgrid. IET Smart Grid 2025, 8, e12207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugalde-Loo, C.E.; Wang, Y.; Wang, S.; Ming, W.; Liang, J.; Li, W. Review on Z-Source Solid State Circuit Breakers for DC Distribution Networks. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 9, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bento, A.R.F.; Bento, F.; Cardoso, A.J.M. A Review on Hybrid Circuit Breakers for DC Applications. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2023, 4, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayati, N.; Hajizadeh, A.; Soltani, M. Impact of Faults and Protection Methods on DC Microgrids Operation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2018 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe, EEEIC/I and CPS Europe 2018, Palermo, Italy, 12–15 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Prado, J.L.; Vélez, J.I.; Garcia-Llinás, G.A. Reliability Evaluation in Distribution Networks with Microgrids: Review and Classification of the Literature. Energies 2020, 13, 6189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCCA. The Who, What, When and Why of WCCA Contents: What Is a WCCA? WCCA: West Covina, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.M. Worst case circuit analysis—An overview (electronic parts/circuits tolerance analysis). In Proceedings of the Annual Reliability and Maintainability Symposium, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 22–25 January 1996; pp. 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenertz, B.A. Electrical Design Worst-Case Circuit Analysis: Guidelines and Draft Standard (REV A); The Aerospace Corporation: Chantilly, VA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, M.J.; Tadeo, F.; Salazar, J. Evaluation of the Worst-Case Performance of Active Filters, using Robust Control Ideas. Int. J. Sci. Tech. Autom. Control Comput. Eng. IJ-STA 2010, 4, 1338–1353. [Google Scholar]

- Khayat, M.; El Mrabet, M.; Mekrini, Z.; Boulaala, M. Review on the Reliability Analysis of Isolated Microgrids. In International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems for Sustainable Development; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 931, pp. 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strenge, L.; Kirchhoff, H.; Ndow, G.L.; Hellmann, F. Stability of meshed DC microgrids using Probabilistic Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Direct Current Microgrids, ICDCM 2017, Nuremburg, Germany, 27–29 June 2017; pp. 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatis, D.H. Failure Mode and Effect Analysis: FMEA from Theory to Execution; ASQC/Quality Press: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2003; p. 455. [Google Scholar]

- Zúñiga, A.A.; Fernandes, J.F.P.; Branco, P.J.C. Fuzzy-Based Failure Modes, Effects, and Criticality Analysis Applied to Cyber-Power Grids. Energies 2023, 16, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyghami, S.; Davari, P.; F-Firuzabad, M.; Blaabjerg, F. Failure mode, effects and criticality analysis (FMECA) in power electronic based power systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 21st European Conference on Power Electronics and Applications, EPE 2019 ECCE Europe, Genova, Italy, 3–5 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badapanda, M.K.; Tripathi, A.; Upadhyay, R.; Lad, M. High Voltage DC Power Supply with Input Parallel and Output Series Connected DC-DC Converters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 6764–6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Hossain, M.M.; Mantooth, H.A. Cryogenic Overcurrent Characteristic of GaN HEMT and Converter Evaluation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 6479–6487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, K.P.; Vijayakumar, T. Study of Capacitor & Diode Aging effects on Output Ripple in Voltage Regulators and Prognostic Detection of Failure. Int. J. Electron. Telecommun. 2022, 68, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, J.P.; Zhang, R.; Porter, M.; Song, Q.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.; Wang, R.; Saito, W.; Zhang, Y. Stability, Reliability, and Robustness of GaN Power Devices: A Review. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 8442–8471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abuelnaga, A.; Narimani, M.; Bahman, A.S. Power electronic converter reliability and prognosis review focusing on power switch module failures. J. Power Electron. 2021, 21, 865–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinabadi, F.; Chakraborty, S.; Bhoi, S.K.; Prochart, G.; Hrvanovic, D.; Hegazy, O. A Comprehensive Overview of Reliability Assessment Strategies and Testing of Power Electronics Converters. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2024, 5, 473–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimpour, S.; Husev, O.; Vinnikov, D.; Kurdkandi, N.V.; Tarzamni, H. Fault Management Techniques to Enhance the Reliability of Power Electronic Converters: An Overview. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 13432–13446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaide, A.M.; Buticchi, G.; Chub, A.; Dalessandro, L. Design and Control for High-Reliability Power Electronics: State-of-the-Art and Future Trends. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Ind. Electron. 2023, 5, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, M.; Mohammadpour, J.; Li, H.; Huang, H.; Zarei, E.; Pirbalouti, R.G.; Adumene, S. Fault tree analysis improvements: A bibliometric analysis and literature review. Qual. Reliab. Eng. Int. 2023, 39, 1639–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patiño-Álvarez, G.A.; Arias-Pérez, J.S.; Muñoz-Galeano, N. A Step-by-Step Methodology for Obtaining the Reliability of Building Microgrids Using Fault TreeAnalysis. Computers 2024, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC TS 62257-5:2015; Recommendations for Renewable Energy and Hybrid Systems for Rural Electrification-Part 5: Protection Against Electrical Hazards International Electrotechnical Commission. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- IEC TS 62257-7-1:2010; Recommendations for Small Renewable Energy and Hybrid Systems for Rural Electrification-Part 7-1: Generators-Photovoltaic Generators. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- IEC TS 62257-9-2:2016; Technical Specification Recommendations for Renewable Energy and Hybrid Systems for Rural Electrification-Part 9-2: Integrated systems-Microgrids International Electrotechnical Commission. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- IEC TS 62257-9-5:2024; Technical Specification Renewable Energy Off-Grid Systems-Part 9-5: Integrated Systems-Laboratory Evaluation of Stand-Alone Renewable Energy Products for Rural Electrification International Electrotechnical Commission. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- IEEE 2030.10:2021; IEEE Standard for DC Microgrids for Rural and Remote Electricity Access Applications. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021.

- IEEE 1547:2018; IEEE Standard for Interconnection and Interoperability of Distributed Energy Resources with Associated Electric Power Systems Interfaces. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018.

- Kant, K.; Gupta, O.H. DC Microgrid: A Comprehensive Review on Protection Challenges and Schemes. IETE Tech. Rev. 2023, 40, 574–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandini, K.K.; Jayalakshmi, N.S.; Jadoun, V.K. An overview of DC Microgrid with DC distribution system for DC loads. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 51, 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MIL-STD-1399-1:2018. Available online: http://everyspec.com/MIL-STD/MIL-STD-1300-1399/MIL-STD-1399-SECT-300_PART-1_55833/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Hoffman, M.; Marcos, A.C.; Jessica, R.K.; Shahnawaz, A.S.; Tan, J.; De La Rosa Marcus, I. Microgrid Handbook for Army Resilience a Technical Review. 2025. Available online: https://www.pnnl.gov/main/publications/external/technical_reports/PNNL-38494.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Carvalho, E.L.; Blinov, A.; Chub, A.; Emiliani, P.; De Carne, G.; Vinnikov, D. Grid Integration of DC Buildings: Standards, Requirements and Power Converter Topologies. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2022, 3, 798–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher | Building-Integrated DCMG | Standalone DCMG | Grid-Connected DCMG | Community DCMG | General Applications of DCMG | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elsevier | 320 | 410 | 720 | 260 | 540 | 2250 |

| IEEE | 360 | 450 | 780 | 290 | 520 | 2400 |

| Wiley | 210 | 330 | 430 | 170 | 330 | 1470 |

| Springer | 240 | 390 | 520 | 180 | 450 | 1780 |

| Taylor & Francis | 180 | 310 | 420 | 150 | 340 | 1400 |

| MDPI | 260 | 420 | 560 | 190 | 370 | 1800 |

| Google Scholar | 1200 | 1800 | 3000 | 950 | 2100 | 9050 |

| 13.75% | 20.40% | 31.90% | 10.87% | 23.08% | 100% |

| Parameter/Topology | Single-Bus | Radial | Ring | Mesh |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplicity | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Reliability | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Fault-Tolerance | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Protection Complexity | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Power Efficiency | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Scalability | 2 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Flexibility | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Cost | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Use Cases | Small Labs | Small Community | Critical or Remote sites | Utility Scale |

| Feature | Centralized Control | Decentralized Control | Distributed Control | Hierarchical Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reliability | Low | Very High | High | High |

| Single-Point of Failure Effect | Yes | No | No | Reduced |

| Realizability | High | High | Complex | Medium |

| Flexibility | Very Low | Very High | High | High |

| Scalability & Modularity | Very Low | Very High | High | High |

| Plug-and-Play Capability | Very Low | Very High | High | High |

| Cost | High | Low | Medium | Medium |

| Parameter | SSCB | HCB | ZSB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interruption Time | 5–50 µs | 1–3 ms | 100–500 µs |

| On-State Voltage Drop | 1.5–3.0 V | ≤0.2 V | 0.5–1.5 V |

| Conduction Loss at 100 A | 150–300 W | ≤10 W | 50–150 W |

| DC Current Rating (INOM) | 50–300 A | 50–300 A | 50–300 A |

| Fault-Current Limiting | 2–4 × INOM | 2–4 × INOM | 2–4 × INOM |

| -Rating | Very Low | Low–Moderate | Low |

| Typical LVDC Rating | 380–750 V DC | 380–750 V DC | 380–750 V DC |

| Control Complexity | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| Thermal Management | High | Low | Medium |

| Relative Cost | High | Medium | Medium |

| Fault ID | Fault Description | Severity | Occurrence | Non-Detection | PRN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Over Voltage (Input) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| F2 | Failure of the Filtering components | 4 | 3 | 7 | 84 |

| F3 | Failure of switching devices | 3 | 2 | 2 | 12 |

| F4 | Failure in the Primary control network | 4 | 2 | 3 | 24 |

| F5 | Failure in the Secondary control system | 7 | 3 | 2 | 42 |

| F1 | Over Voltage (Input) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shabbir, G.; Hasan, A.; Yaqoob Javed, M.; Shahid, K.; Mussenbrock, T. Review of DC Microgrid Design, Optimization, and Control for the Resilient and Efficient Renewable Energy Integration. Energies 2025, 18, 6364. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236364

Shabbir G, Hasan A, Yaqoob Javed M, Shahid K, Mussenbrock T. Review of DC Microgrid Design, Optimization, and Control for the Resilient and Efficient Renewable Energy Integration. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6364. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236364

Chicago/Turabian StyleShabbir, Ghulam, Ali Hasan, Muhammad Yaqoob Javed, Kamal Shahid, and Thomas Mussenbrock. 2025. "Review of DC Microgrid Design, Optimization, and Control for the Resilient and Efficient Renewable Energy Integration" Energies 18, no. 23: 6364. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236364

APA StyleShabbir, G., Hasan, A., Yaqoob Javed, M., Shahid, K., & Mussenbrock, T. (2025). Review of DC Microgrid Design, Optimization, and Control for the Resilient and Efficient Renewable Energy Integration. Energies, 18(23), 6364. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236364