Coordinated Voltage and Power Factor Optimization in EV- and DER-Integrated Distribution Systems Using an Adaptive Rolling Horizon Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

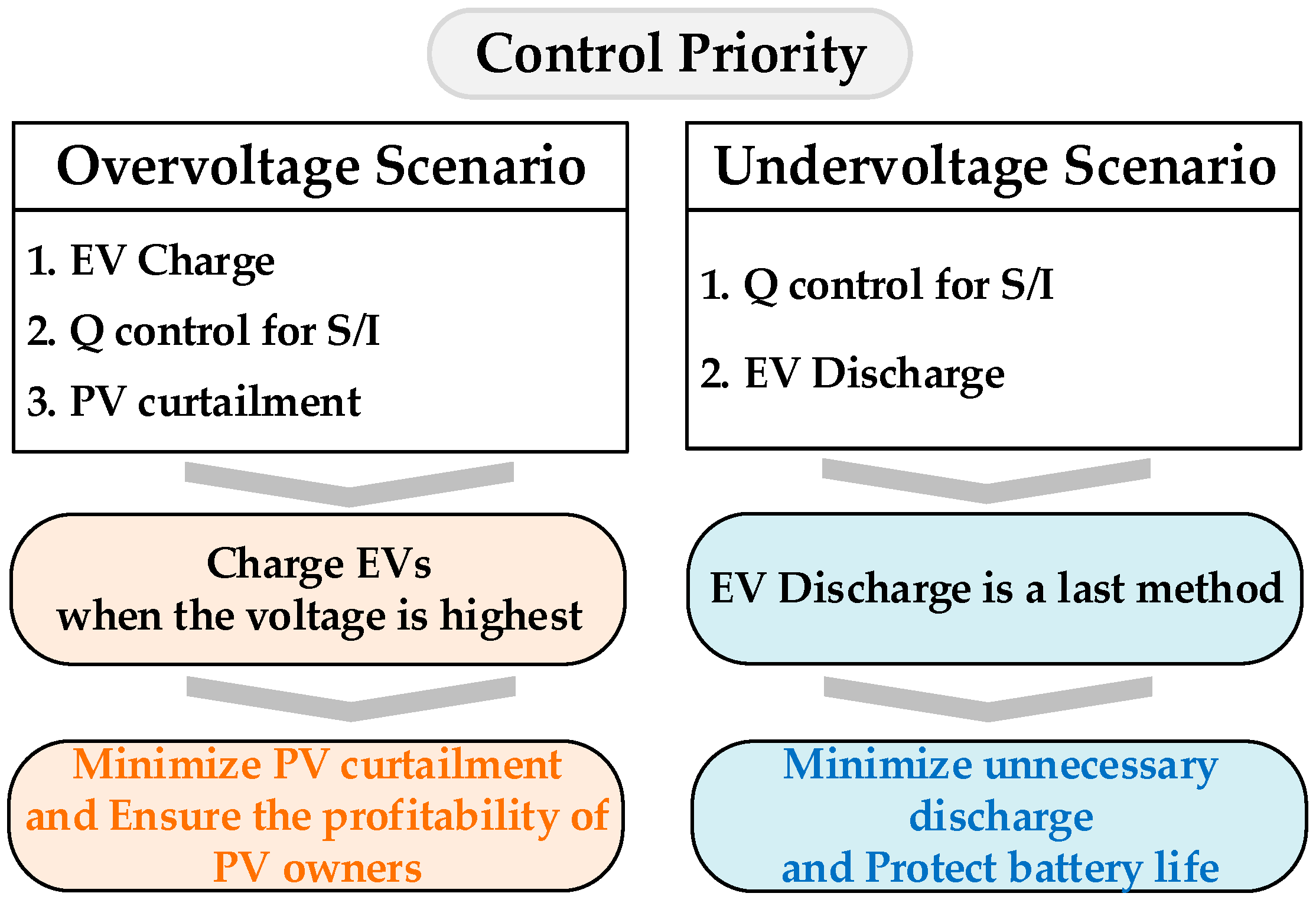

- A real-time control strategy for EVs and inverters based on the ARH framework is proposed. By explicitly considering uncertainties in EV arrival/departure times and SOC levels, the method enables effective voltage regulation through EV charging and discharging. The MILP-based formulation ensures satisfaction of SOC constraints while meeting the requirements of EV owners.

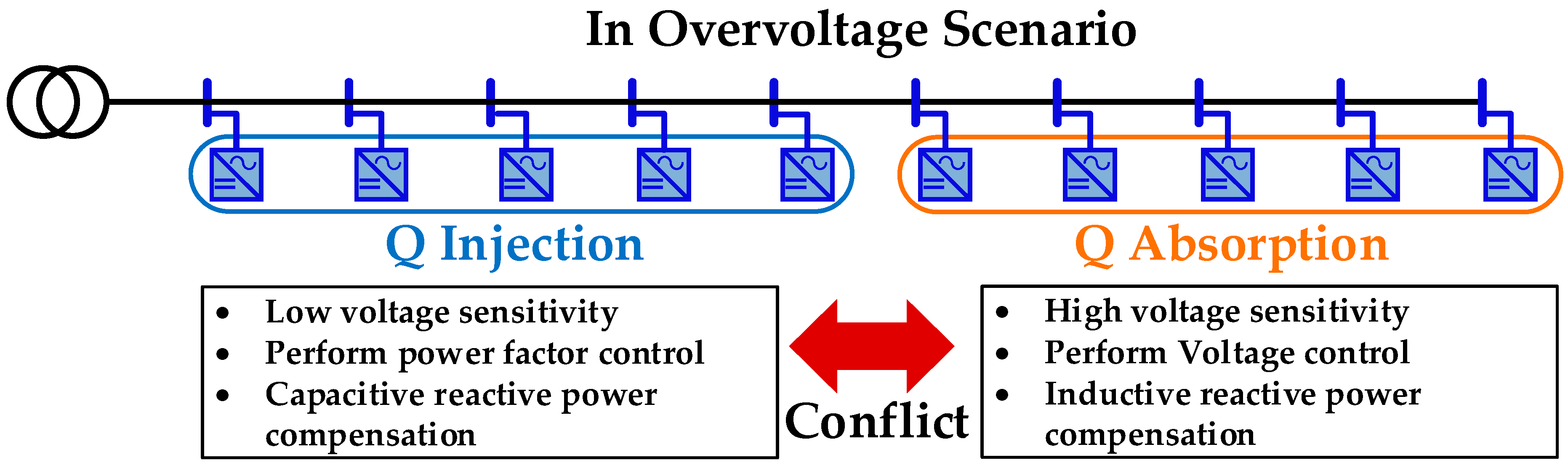

- Since reactive power control for voltage regulation may degrade the system’s power factor, this paper proposes a strategy that distinguishes between inverters that are responsible for voltage control and those dedicated to power-factor improvement. The optimal reactive power output of each inverter is determined through AC-OPF to maximize overall system performance.

- The proposed method enables stable operation of the power system without network upgrades or additional infrastructure. By providing an algorithm that is applicable to low-voltage distribution networks, it offers a practical foundation for maintaining system stability during the transitional period prior to full voltage level uprating in distribution systems.

2. System Description

2.1. Control Structure

2.2. Proposed Method

2.2.1. Two-Stage Optimization Framework for Voltage and PF Using ARH

- MILP for EV charging/discharging scheduling.

- NLP for AC-OPF.

2.2.2. The Need for Optimization Method

2.3. Adaptive Rolling Horizon Approach

3. Mathematical Description

3.1. MILP for EV Charge/Discharge Scheduling (Stage 1)

- (1)

- Objective Function:

- (2)

- SOC constraints:

3.2. NLP for AC-OPF (Stage 2)

- (1)

- Objective Function:

- (2)

- Constraints:

4. Simulation and Results

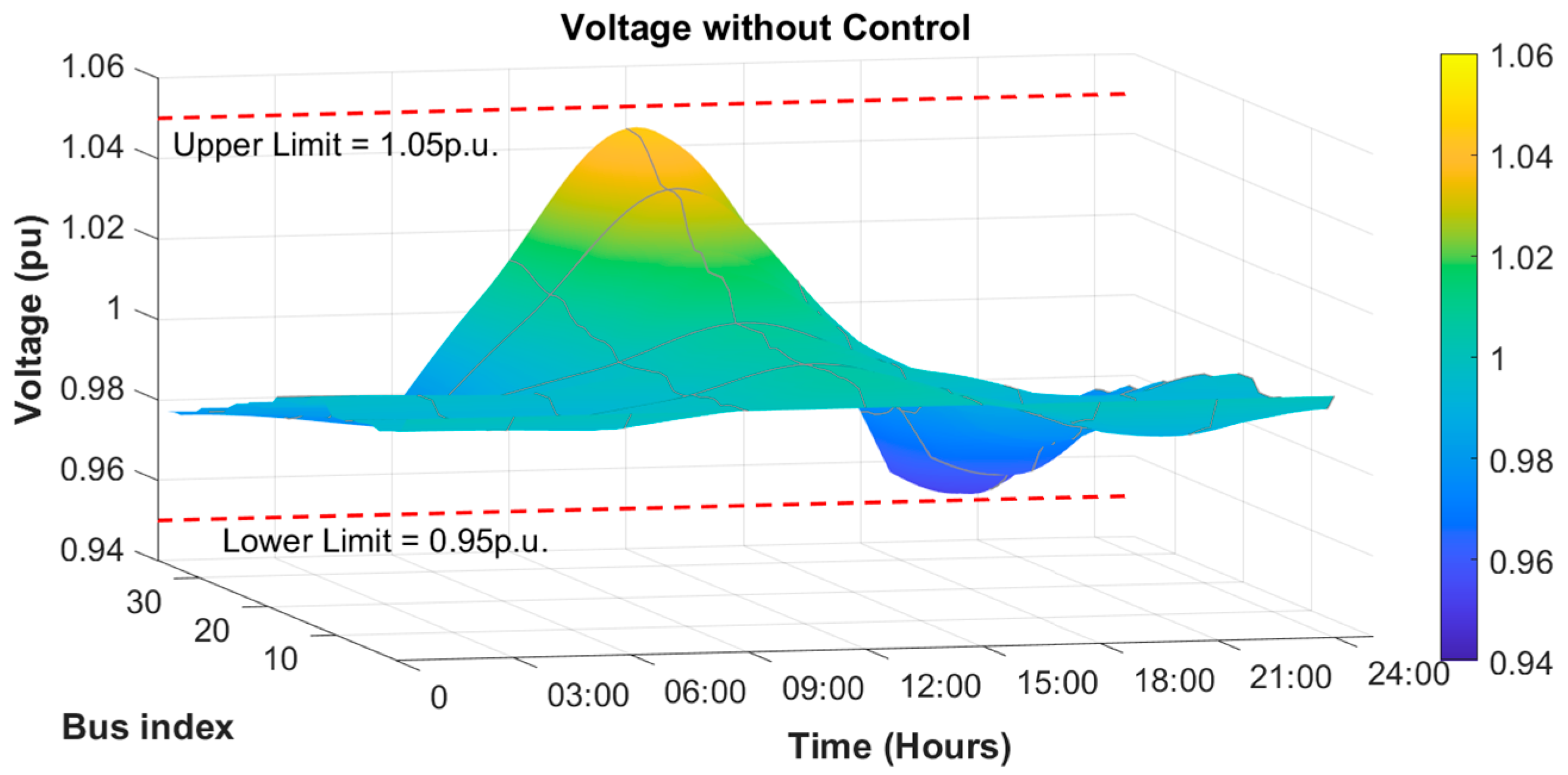

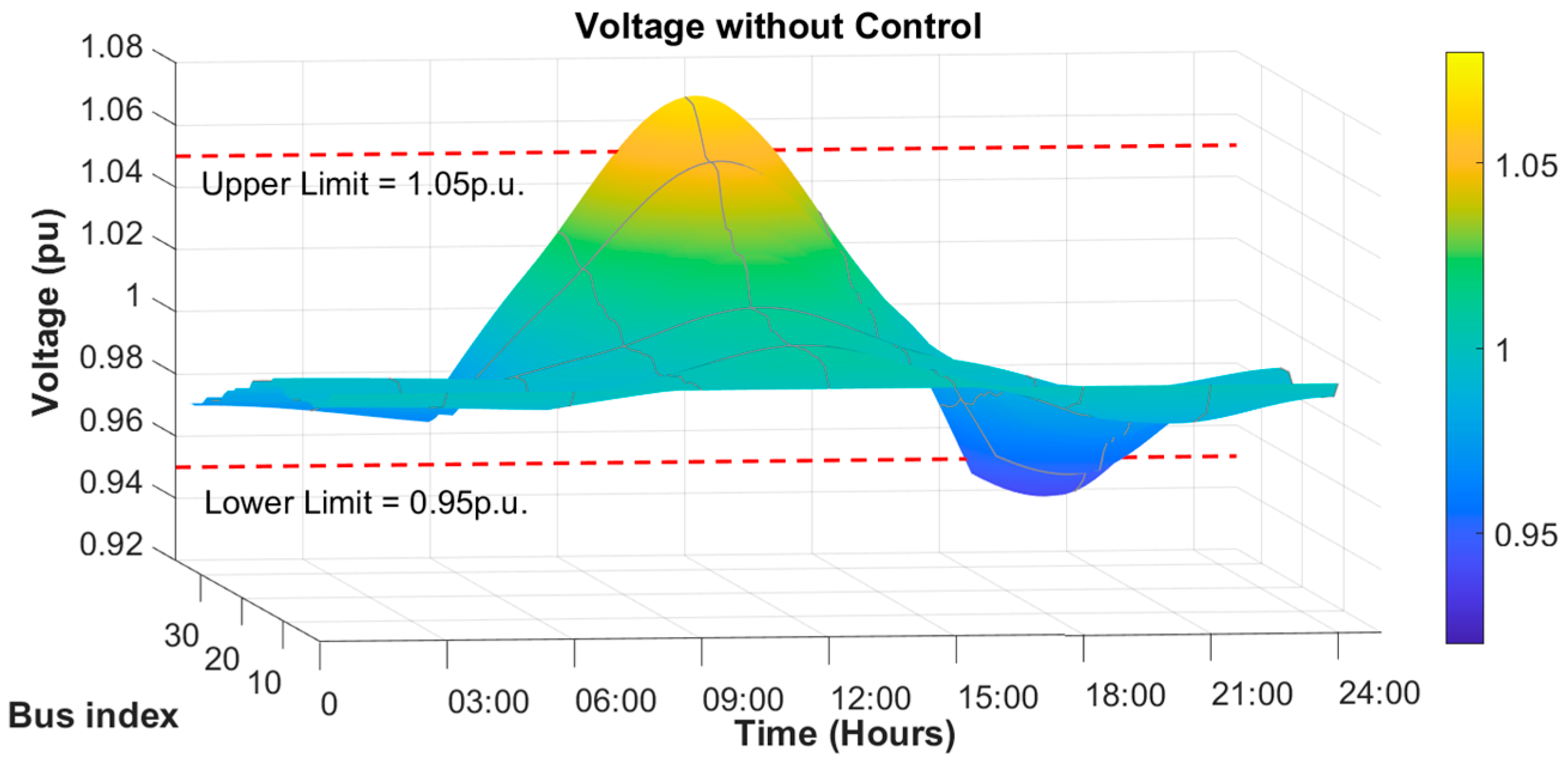

4.1. Results of Case 1 (No Control)

4.1.1. Case 1-1 (Low PV Generation, Load)

4.1.2. Case 1-2 (Medium PV Generation, Load)

4.2. Results of Case 2 (AC-OPF Control)

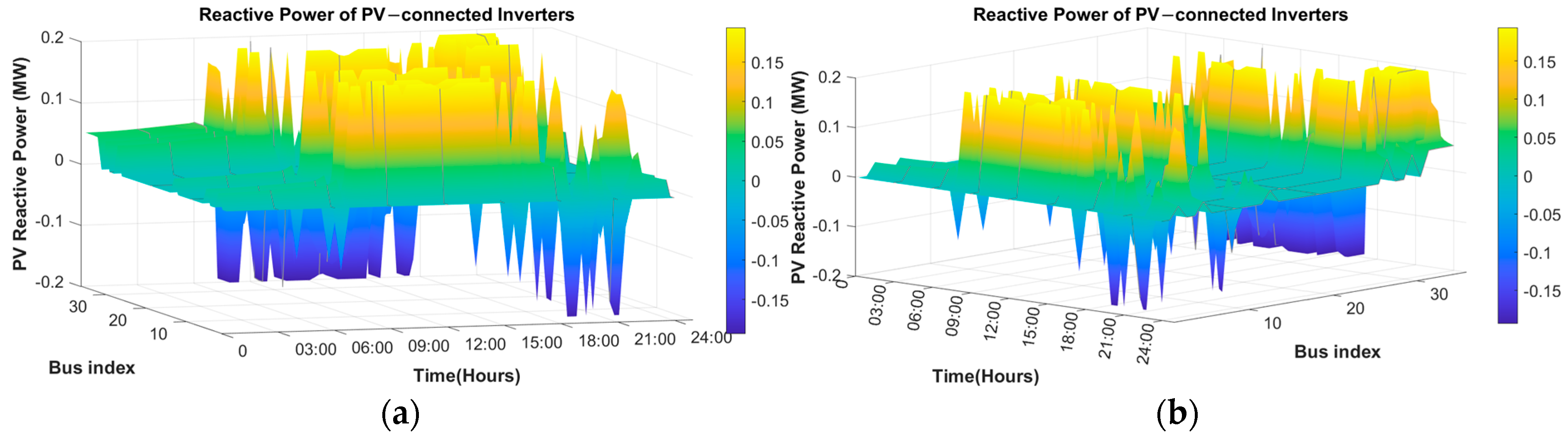

4.2.1. Case 2-1 (Medium PV Generation, Load)

4.2.2. Case 2-2 (High PV Generation, Load)

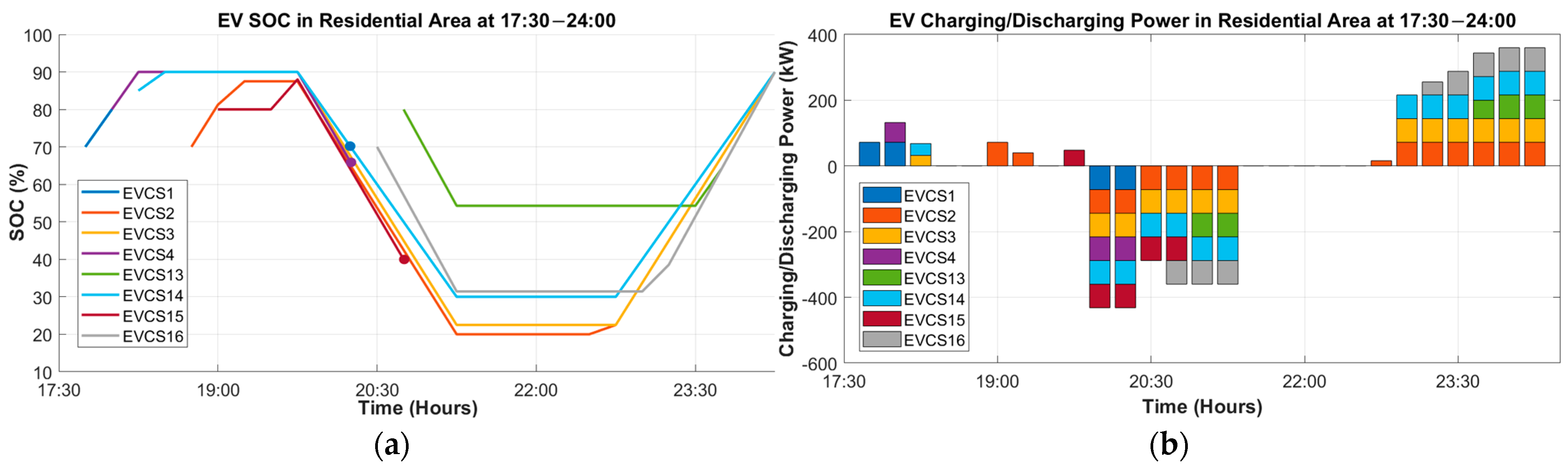

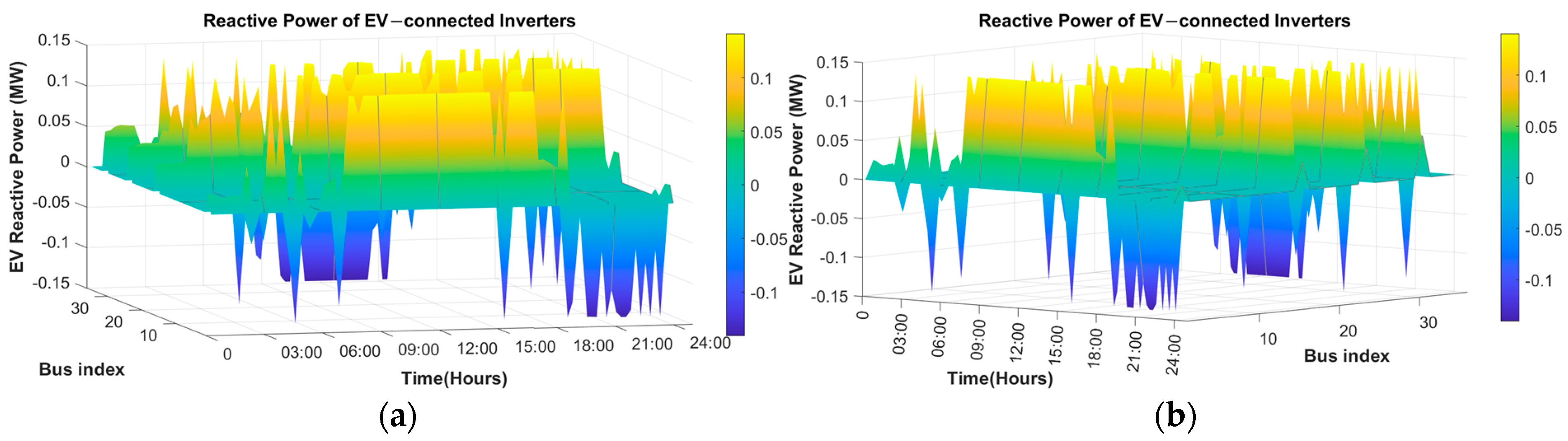

4.3. Results of Case 3 (ARH-Based EV, DERs Control)

4.3.1. Case 3-1 (Medium PV Generation, Load)

4.3.2. Case 3-2 (High PV Generation, Load)

4.4. Results Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Acronyms | |

| DERs | Distributed energy resources |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| ARH | Adaptive rolling horizon |

| MPC | Model predictive control |

| PF | Power factor |

| DERMS | Distributed energy resource management system |

| p.u. | Per unit |

| NWA | Non wire alternative |

| DSO | Distribution system operator |

| DR | Demand response |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-grid |

| PEV | Plug-in electric vehicle |

| PCC | Point of common coupling |

| VVO | Volt/Var optimization |

| OLTC | On-load tap changer |

| CB | Capacitor bank |

| SOCP | Second-order cone programming |

| OPF | Optimal power flow |

| IBR | Inverter-based resources |

| MILP | Mixed-integer linear programming |

| NLP | Nonlinear programming |

| Indices and Sets definition | |

| Time step index in the rolling horizon | |

| Time step duration | |

| Bus indices | |

| Number of buses | |

| Number of time steps, | |

| Number of EV buses | |

| Number of PV buses | |

| Adaptive rolling-horizon window at time t (set of time steps from current t to the latest EV departure) | |

| Variables and parameters | |

| Latest departure time among connected EVs at time step t | |

| Normalized EV charging/discharging rate at bus k, time step t | |

| Penalty factor for EV discharging | |

| Normalized voltage index (0–1) at bus k, time step t | |

| Upper/lower voltage limit | |

| SOC for EV at bus k, time step t | |

| SOC for EV at bus k, departure time step | |

| Required SOC for EV on bus k | |

| Maximum/minimum SOC limit for EV | |

| EV capacity at bus k | |

| Rated charging/discharging active power for EV | |

| Charging/discharging efficiency | |

| Binary indicator enforcing mutual exclusivity of EV charging/discharging at time step t | |

| Weight factor | |

| Voltage magnitude for bus k, time step t | |

| Reference bus voltage magnitude | |

| Power factor at substation, time step t | |

| Target power factor | |

| Maximum/minimum allowable power factor | |

| Penalty coefficient for PV curtailment | |

| Curtailed PV active power for bus i, time step t | |

| Injected active/reactive power for bus i, time step t | |

| Active/reactive load of bus i, time step t | |

| Available PV active power for bus i, time step t | |

| Charging/discharging active power for bus i, time step t | |

| Reactive power of PV/EV inverter for bus i, time step t | |

| Maximum reactive power of PV/EV inverter for bus k, time step t | |

| Rated apparent power of PV/EV inverter for bus k, time step t | |

| Current magnitude flowing at line , time step t | |

| Thermal current limit of line | |

| Voltage phase angle at bus i, time step t | |

| Conductance/susceptance between buses i and k | |

References

- Masson, G.; Bosch, E.; Van Rechem, A.; de l’Epine, M. Snapshot of Global PV Markets 2023; Report IEA-PVPS T1-44:2023. IEA Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme (IEA PVPS), Task 1; IEA: Angers, France, 2023; ISBN 978-3-907281-43-7. Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2024; Typeset in France, October 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Abedinia, O.; Moradzadeh, M.; Acharya, D.; Ghadimi, N. Grid Integration Challenges and Solution Strategies for Solar PV Systems: A Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 52233–52249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Guo, Q.; Qi, J.; Ajjarapu, V.; Bravo, R.; Chow, J.; Li, Z.; Moghe, R.; Nasr-Azadani, E.; Tamrakar, U.; et al. Review of Challenges and Research Opportunities for Voltage Control in Smart Grids. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2019, 34, 2790–2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabali, A.; Ghofrani, M.; Etezadi-Amoli, M.; Fadali, M.S.; Baghzouz, Y. Genetic-Algorithm-Based Optimization Approach for Energy Management. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2013, 28, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoune, K.; Ahaitouf, A.; El Markhi, H.; Ghandour, M.; Ghennioui, A. Optimal Sizing of Multiple Renewable Energy Resources and PV Inverter Reactive Power Control Encompassing Environmental, Technical, and Economic Issues. IEEE Syst. J. 2019, 13, 3026–3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Vega, S.; Toquica, M.H.; Lima, L.; Leite, J.A.C.; Cabalcante-Goyes, C. Voltage Control in Distribution Networks: An Overview. Energies 2025, 18, 3568. [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Ocaña, J.E.; Chen, Y.; Siddiqi, U.; Zhang, B. Non-Wire Alternatives: An Additional Value Stream for Distributed Energy Resources. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2020, 11, 1287–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourghasem Gavgani, P.; Baghbannovin, S.; Mohseni-Bonab, S.M.; Kamwa, I. Distributed Energy Resources Management System (DERMS) and Its Coordination with Transmission System: A Review and Co-Simulation. Energies 2024, 17, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, X.; Xie, J.; Zhou, M.; Wang, X.; Hu, T.; Bai, W.; Zhang, T. Distributed Energy Resource Management System (DERMS) Solution for Feeder Voltage Management for Utility Integrated DERs. In Proceedings of the 2021 6th International Conference on Power and Renewable Energy (ICPRE), Shanghai, China, 17–20 September 2021; pp. 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strezoski, L. Utility DERMS and DER Aggregators: An Ideal Case for Tomorrow’s DSO. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference Europe (ISGT Europe), Novi Sad, Serbia, 10–12 October 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Ye, K.; Zhao, J.; Ding, F.; Giraldez, J. DERMS Online: A New Voltage Sensitivity-Enabled Feedback Optimization Framework. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference (ISGT), New Orleans, LA, USA, 24–28 April 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strezoski, L.; Stefani, I. Utility DERMS for Active Management of Emerging Distribution Grids with High Penetration of Renewable DERs. Electronics 2021, 10, 2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global EV Outlook 2025; IEA: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.iea.org/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Eltohamy, M.S.; Tawfiq, M.H.; Ahmed, M.M.R.; Mohammed, B.; Ahmed, I.; Alaas, Z.; Youssef, H.; Raouf, A. A Comprehensive Review of V2G Technology. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 27, 101138. [Google Scholar]

- İnci, M.; Savrun, M.M.; Çelik, Ö. Integrating Electric Vehicles as Virtual Power Plants: A Comprehensive Review on Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) Concepts, Interface Topologies, Marketing and Future Prospects. J. Energy Storage 2022, 55, 105579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.J.E.; Muttaqi, K.M.; Sutanto, D. Effective Utilization of Available PEV Battery Capacity for Mitigation of Solar PV Impact and Grid Support with Integrated V2G Functionality. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2016, 7, 1562–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Awami, A.T.; Sortomme, E.; Akhtar, G.M.A.; Faddel, S. A Voltage-Based Controller for an Electric-Vehicle Charger. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2016, 65, 4185–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 1547-2018; IEEE Standard for Interconnection and Interoperability of Distributed Energy Resources with Associated Electric Power Systems Interfaces. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/ (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Ismeil, M.A.; Alfouly, A.; Hussein, H.S.; Hamdan, I. Improved Inverter Control Techniques in Terms of Hosting Capacity for Solar Photovoltaic Energy with Battery Energy Storage System. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 140161–140176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Kirschen, D.S. Bi-Level Volt/VAR Optimization in Distribution Networks with Smart PV Inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 37, 3604–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.M.-U.-T.; Hasan, M.S.; Kamalasadan, S. A Novel Voltage Optimization Co-Simulation Framework for Electrical Distribution System with High Penetration of Renewables. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 61, 1080–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboshady, F.M.; Pisica, I.; Zobaa, A.F.; Taylor, G.A.; Ceylan, O.; Ozdemir, A. Reactive Power Control of PV Inverters in Active Distribution Grids with High PV Penetration. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 81477–81496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, K.R.; Khatod, D.K. Smart Inverter-Based Distributed Volt/Var Control for Voltage Violation Mitigation of Unbalanced Distribution Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2024, 39, 1481–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farokhi Soofi, A.; Manshadi, S.D. Unleashing Grid Services Potential of Electric Vehicles for the Volt/VAR Optimization Problem. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 14115–14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Biyik, E.; Dhople, S.V.; Wang, J.; Low, S.H.; Lavaei, J.; Domínguez-García, A.D. MPC-Based Decentralized Voltage Control in Power Distribution Systems with EV and PV Coordination. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 2900–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Teh, J. Two-Stage Optimal Dispatching of AC/DC Hybrid Active Distribution Systems Considering Network Flexibility. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2023, 11, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Teh, J.; Chen, C. Optimal Dispatching for AC/DC Hybrid Distribution Systems with Electric Vehicles: Application of Cloud-Edge-Device Cooperation. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 3128–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinh, P.-H.; Zafar, R.; Chung, I.-Y. Optimal PEV Charging and Discharging Algorithms to Reduce Operational Cost of Microgrid Using Adaptive Rolling Horizon Framework. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 133668–133680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- California Public Advocates Office (Cal Advocates). Report on the Results of Operations for Southern California Edison Company General Rate Case Test Year 2025; Doc ID: 526146957; California Public Utilities Commission: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, J.; Denholm, P.; Mooney, M.; Steinberg, D.; Hale, E.; Heath, G.; Palminitier, B.; Sigrin, B.; Keyser, D.; McCamey, D.; et al. LA100: The Los Angeles 100% Renewable Energy Study—Executive Summary; NREL/TP-6A20-79444-ES; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kersting, W.H. Radial Distribution Test Feeders. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 1991, 6, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI C84.1-2011; American National Standard for Electric Power Systems and Equipment—Voltage Ratings (60 Hertz). National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA): Rosslyn, VA, USA, 2011.

- Vega-Fuentes, E.; León-del Rosario, S.; Cerezo-Sánchez, J.M.; Vega-Martínez, A. Fuzzy Inference System for Volt/Var Control in Distribution Substations in Isolated Power Systems. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1401.1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husein, M.; Chung, I.-Y. Optimal Design and Financial Feasibility of a University Campus Microgrid Considering Renewable Energy Incentives. Appl. Energy 2018, 225, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husein, M.; Hau, V.B.; Chung, I.-Y.; Chae, W.-K.; Lee, H.-J. Design and Dynamic Performance Analysis of a Stand-Alone Microgrid—A Case Study of Gasa Island, South Korea. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2017, 12, 1777–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Teh, J.; Fang, S.; Dai, Z.; Wang, P. Two-Stage Optimal Dispatch Framework of Active Distribution Networks with Hybrid Energy Storage Systems via Deep Reinforcement Learning and Real-Time Feedback Dispatch. J. Energy Storage 2025, 108, 115169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | No Control | AC-OPF Control | ARH-Based EV, DERs Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1-1 | Case 1-2 | Case 2-1 | Case 2-2 | Case 3-1 | Case 3-2 | |

| Total PV Capacity (MW) | 1.8 MW | 2.7 MW | 2.7 MW | 3.6 MW | 2.7 MW | 3.6 MW |

| EV Scheduling | X | X | X | X | O | O |

| Peak P Load (MW) | 2.207 | 3.21 | 3.21 | 3.531 | 3.21 | 3.531 |

| Peak Q Load (MVar) | 0.899 | 1.308 | 1.308 | 1.438 | 1.308 | 1.438 |

| Bus | Station No. | Connecting Time | EV Capacity (kWh) | Initial SOC (%) | Depart SOC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17 | 5 | 08:50–11:25 12:25–17:12 | 90 90 | 70 55 | 90 90 |

| 17 | 6 | 09:05–10:50 13:24–16:17 | 80 100 | 80 65 | 90 90 |

| 17 | 7 | 09:40–11:08 12:55–16:03 | 100 90 | 65 50 | 90 90 |

| 17 | 8 | 09:38–15:47 | 120 | 60 | 90 |

| 25 | 9 | 08:47–16:44 | 150 | 70 | 90 |

| 25 | 10 | 09:10–11:02 11:37–16:12 | 130 100 | 80 75 | 90 90 |

| 25 | 11 | 09:41–11:23 11:56–16:07 | 100 95 | 65 80 | 90 90 |

| 25 | 12 | 08:42–10:51 12:18–15:14 | 120 110 | 60 50 | 90 90 |

| Bus | Station No. | Connecting Time | EV Capacity (kWh) | Initial SOC (%) | Depart SOC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 00:12–05:55 17:25–19:48 | 110 | 40 70 | 90 50 |

| 180 | |||||

| 2 | 2 | 00:25–08:27 18:28–23:59 | 100 160 | 30 70 | 80 90 |

| 2 | 3 | 00:20–06:50 17:49–23:59 | 120 160 | 40 85 | 90 90 |

| 2 | 4 | 00:40–06:10 17:40–19:58 | 100 150 | 30 80 | 85 50 |

| 32 | 13 | 00:12–06:32 20:17–23:59 | 100 140 | 60 80 | 85 90 |

| 32 | 14 | 00:20–06:16 17:51–23:59 | 90 180 | 50 85 | 80 90 |

| 32 | 15 | 00:58–07:48 18:36–20:20 | 120 150 | 70 80 | 80 40 |

| 32 | 16 | 00:37–07:37 20:03–23:59 | 130 140 | 60 70 | 90 90 |

| Method | Size of PV, Load | Cases | Voltage (p.u.) | Power Factor | PV Curtailment (MWh) | Total PV Capacity (MW) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Min | Max | Min | Avg | |||||

| No Control | Low | Case 1-1 | 1.045 | 0.952 | 0.994 | 0.678 | 0.916 | - | 1.8 |

| Medium | Case 1-2 | 1.068 | 0.938 | 0.995 | 0.517 | 0.899 | - | 2.7 | |

| AC-OPF Control | Medium | Case 2-1 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1 | 0.973 | 0.995 | 0.23 | 2.7 |

| High | Case 2-2 | 1.05 | 0.947 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.995 | 2.42 | 3.6 | |

| ARH-based EV, DERs Control | Medium | Case 3-1 | 1.045 | 0.95 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.994 | 0 | 2.7 |

| High | Case 3-2 | 1.05 | 0.95 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.995 | 1.16 | 3.6 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yun, W.; Trinh, P.-H.; Joo, J.-Y.; Chung, I.-Y. Coordinated Voltage and Power Factor Optimization in EV- and DER-Integrated Distribution Systems Using an Adaptive Rolling Horizon Approach. Energies 2025, 18, 6357. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236357

Yun W, Trinh P-H, Joo J-Y, Chung I-Y. Coordinated Voltage and Power Factor Optimization in EV- and DER-Integrated Distribution Systems Using an Adaptive Rolling Horizon Approach. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6357. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236357

Chicago/Turabian StyleYun, Wonjun, Phi-Hai Trinh, Jhi-Young Joo, and Il-Yop Chung. 2025. "Coordinated Voltage and Power Factor Optimization in EV- and DER-Integrated Distribution Systems Using an Adaptive Rolling Horizon Approach" Energies 18, no. 23: 6357. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236357

APA StyleYun, W., Trinh, P.-H., Joo, J.-Y., & Chung, I.-Y. (2025). Coordinated Voltage and Power Factor Optimization in EV- and DER-Integrated Distribution Systems Using an Adaptive Rolling Horizon Approach. Energies, 18(23), 6357. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236357