1. Introduction

In the context of the green energy transition, solar energy utilization technologies are increasingly favored, among which photovoltaic cell power generation technology stands out as one of the most effective methods due to its clean nature. However, the solar radiation energy absorbed by crystalline silicon photovoltaic cells only converts 5–25% into electrical energy, while the remaining unused energy is transformed into heat. The photoelectric efficiency of photovoltaic (PV) panels is influenced by their surface temperature. Under solar irradiation with an intensity of 1000 W/m2, once the surface temperature exceeds 25 °C, for every increase of 1 degree, the photoelectric efficiency will decrease by 0.4–0.5%. Meanwhile, excessively high operating temperatures can also affect the service life of PV modules. Therefore, research on how to effectively manage the heat of photovoltaic components is significant in reducing the operating temperature of solar panels and improving their photoelectric conversion efficiency, which is very important in addressing issues such as the depletion of traditional fossil energy and environmental pollution.

The temperature control technologies for PV can be categorized into active and passive methods. Among these, active temperature control technology exhibits a high heat exchange efficiency and good effectiveness because active cooling technology generally requires the consumption of electrical energy or other forms of energy to provide power and displays a complex structure, and the temperature of photovoltaic panels tends to increase along the direction of the working fluid’s flow. This results in an uneven temperature distribution that affects the lifespan of the PV panels, thus severely limiting their practical application, and the issue of temperature increase along the flow direction of the working fluid. This temperature gradient results in uneven thermal distribution, which can adversely affect the lifespan of PV panels. In contrast, passive cooling technologies do not require external energy input, but most conventional passive approaches suffer from low heat transfer efficiency and sub-optimal cooling performance. Currently, research efforts investigating passive temperature control are primarily focused on phase change materials (PCM) and heat pipes (HP).

The latent heat of the phase change of PCM is relatively large, the temperature during the phase change process is close to a constant temperature, and it displays good temperature uniformity, which can well control the temperature of photovoltaic modules. Smith et al. [

1] established a one-dimensional mathematical model of PV–PCM, discretized it using the finite difference method, explored the thermal performance and power generation characteristics of the panels under different parameter conditions, and selected appropriate phase change materials for different regions. Hasan et al. [

2] conducted a temperature control study on the building-integrated photovoltaic (BIPV) system using paraffin wax. The results demonstrated that under solar irradiation with an intensity of 1000 W/m

2, the system achieved a temperature reduction of 18 K over a continuous 30 min period and maintained a cooling effect of 10 K over 5 h. In addition, there were also many related studies regarding the temperature control of lithium batteries. Al-Hallaj and Selman [

3,

4] were the first to apply phase change materials to the temperature control system of lithium-ion batteries. Under nearly adiabatic conditions, they discharged a 100 Ah battery and observed that the temperature rise was approximately 8 °C lower with PCM encapsulation compared to natural cooling. The PCM temperature control could not only effectively reduce the maximum temperature of lithium batteries, but also better maintain the consistency of individual cell temperatures.

Although PCMs have many benefits, they also have drawbacks, including low thermal conductivity, temperature range restrictions, material compatibility, and liquid leakage and volume expansion during phase change [

5]. Further, with a view to augmenting the thermal management performance of PCM, using composite PCM, PCM with nanoparticles, and PCM with hybrid nanoparticles for PV cooling were described as solutions to PCM’s low thermal conductivity problem [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Yadav et al. [

10], through CFD simulation of the effect of nanoparticle-dispersed PCM on PV panel cooling, confirmed that 1 wt% SiO

2 nanoparticles could reduce thermal resistance by approximately 18% and lower panel temperature by 6–9 °C. Zhou et al. [

11] systematically compared the mechanisms by which CuO and CNT enhance the thermal conductivity of paraffin: CuO relied on thermal bridges and interfacial liquid layer effects, while CNT depends on high thermal conductivity networks and molecular orientation. The combination of the two could enhance the effect synergistically, providing a basis for the design of a high-efficiency composite PCM. Concurrently, advancements in HP technology have focused on optimizing wick structures, working fluids, and even exploring wickless or oscillating heat pipe designs for enhanced thermal performance and adaptability under varying heat fluxes [

12,

13]. The synergy of these advanced materials and components hold great promise for developing next-generation, highly efficient passive thermal management systems for photovoltaics.

The heat pipe offers high effective thermal conductivity, compact size, light weight, and structural versatility. Passive thermal management using heat pipes has been widely applied in many fields, especially in electronic devices. Tran et al. [

14] demonstrated the feasibility of applying HP for battery thermal management and showed that the thermal resistance of the HP-based cooling system could be reduced by 30% under natural convection at the condenser section. Rao et al. [

15] adopted a constant-temperature water bath for cooling in the condensation section. The research found that when the heat release rate was lower than 50 W, the maximum temperature of the battery could be controlled below 50 °C, and when the heat release rate was lower than 30 W, the maximum temperature gradient inside the battery could be reduced to 5 °C. Zhao et al. [

16] incorporated HP into the battery thermal management system and implemented five distinct cooling methods in the condensation section of the heat pipes: natural convection, horizontal forced convection, vertical forced convection, constant temperature water bath, and water spray. The results indicated that the water spray cooling method in the condensation section was optimal. For HP, their thermal management performance was significantly influenced by the cooling capacity of the condenser section. Under passive thermal management conditions, heat dissipation at the condenser was primarily limited to natural air convection, which posed certain challenges to the overall thermal management effectiveness.

In recent years, thermal management systems utilizing coupled PCM and HP cooling have garnered significant attention from researchers. The combination of these two technologies effectively leverages their complementary advantages, making them well-suited to meet the thermal management requirements of photovoltaic modules. Yang et al. [

7] studied the thermal management of photovoltaic panels with a pulsating heat pipe/phase change material coupled module. The results showed that the peak temperature and average temperature could be reduced by 14.0% and 11.1%, respectively, in Xiamen. David et al. [

17] utilized an HP to transfer heat to the back of the PCM, and the daily efficiency of the photovoltaic panels could increase by 50%. Sheikh et al. [

18] put PCM into the condensation section to enlarge the cooling capacity of the HP, indicating that phase change material could enhance the temperature drop. In addition, the phase change material and heat pipe coupled module could also be used in spacecraft thermal management [

19] and battery management [

20,

21,

22]. Madhav et al. [

19] proved that a PCM/HP coupled module could prolong working time and reduce peak temperature, which could be applied to spacecraft to reduce the size of the thermal radiator. Chen et al. [

20] demonstrated that combining phase change material with an HP could stabilize the temperature distribution of the battery.

The authors previously studied the thermal management performance of lithium-ion power battery packs using HP/PCM coupled thermal management (TM) [

23,

24]. The results demonstrated that the hybrid TM approach achieved lower surface temperatures and a longer temperature control duration compared to standalone HP or PCM solutions. As the heat transfer process proceeds, the internal coupled heat flux distribution transitions from being dominated by PCM to being dominated by HP, and the temperature control effect after stabilization depends mainly on HP. Under various discharge–charge conditions during prolonged operation, the coupled thermal management system effectively maintains battery temperature stability. Through its hybrid active–passive operation, the maximum energy saving rate can reach up to 81.80%.

The authors of this article previously researched the cooling effect of single-sided photovoltaic modules when PCM and HP are combined. Through model experiments and numerical analysis, it was proven that the coupling of PCM and HP can effectively reduce the temperature of photovoltaic modules, which is conducive to increasing their power generation (

Figure 1) [

25]. Meanwhile, the authors’ univariate analysis indicated that the key parameters of the coupled cooling device must be determined in accordance with local meteorological conditions. Due to the interplay of factors such as solar radiation intensity, ambient temperature, and wind speed, the aforementioned study could not fully reveal the adequacy and effectiveness of the coupled cooling method under realistic weather conditions in different regions. Building upon previous research, this study designed a modular PCM/HP thermal regulation device and applied it for the first time to a full-scale commercial photovoltaic module. Field tests were conducted at three different locations to compare and analyze the cooling and efficiency enhancement effects of using pure PCM versus a combined PCM/HP system on PV panels. The suitability of the thermal regulation device under varying meteorological conditions was also investigated. The contributions of this research are primarily reflected in the following aspects:

An efficient and cost-effective modular passive thermal management device has been developed, which can be directly applied to commercial photovoltaic modules.

Pioneering experimental data on the thermal regulation and efficiency enhancement effects of the PCM/HP coupled passive cooling device on PV modules under varying meteorological conditions have been obtained, while also providing technical support for passive thermal management technologies in low heat-flux scenarios.

3. Results and Discussion

To explore the temperature control effects of different PV thermal management modules during operation, this section collates the experimental data of two modules, namely PV-ref and PV–PCM + HP, during their actual operation. The specific measurement period and test location of the experiment are shown in

Table 6. The collated experimental data mainly include temperature (PV temperature change history), electrical performance (PV photoelectric conversion efficiency, open-circuit voltage, and short-circuit current), and meteorological data (solar irradiance, air temperature, and wind speed).

3.1. Jinan

During the test from 9 to 11 October 2022, the average daily solar irradiance in Jinan was concentrated at 800 W/m

2, with sufficient light intensity. The air temperature mainly varied between 15 °C and 20 °C, with a small temperature difference between morning and evening. The average wind speed was about 0.5 m/s, which was relatively weak. Other relevant data are shown in

Table 7. The temperature changes of PV and PV–PCM/HP are shown in

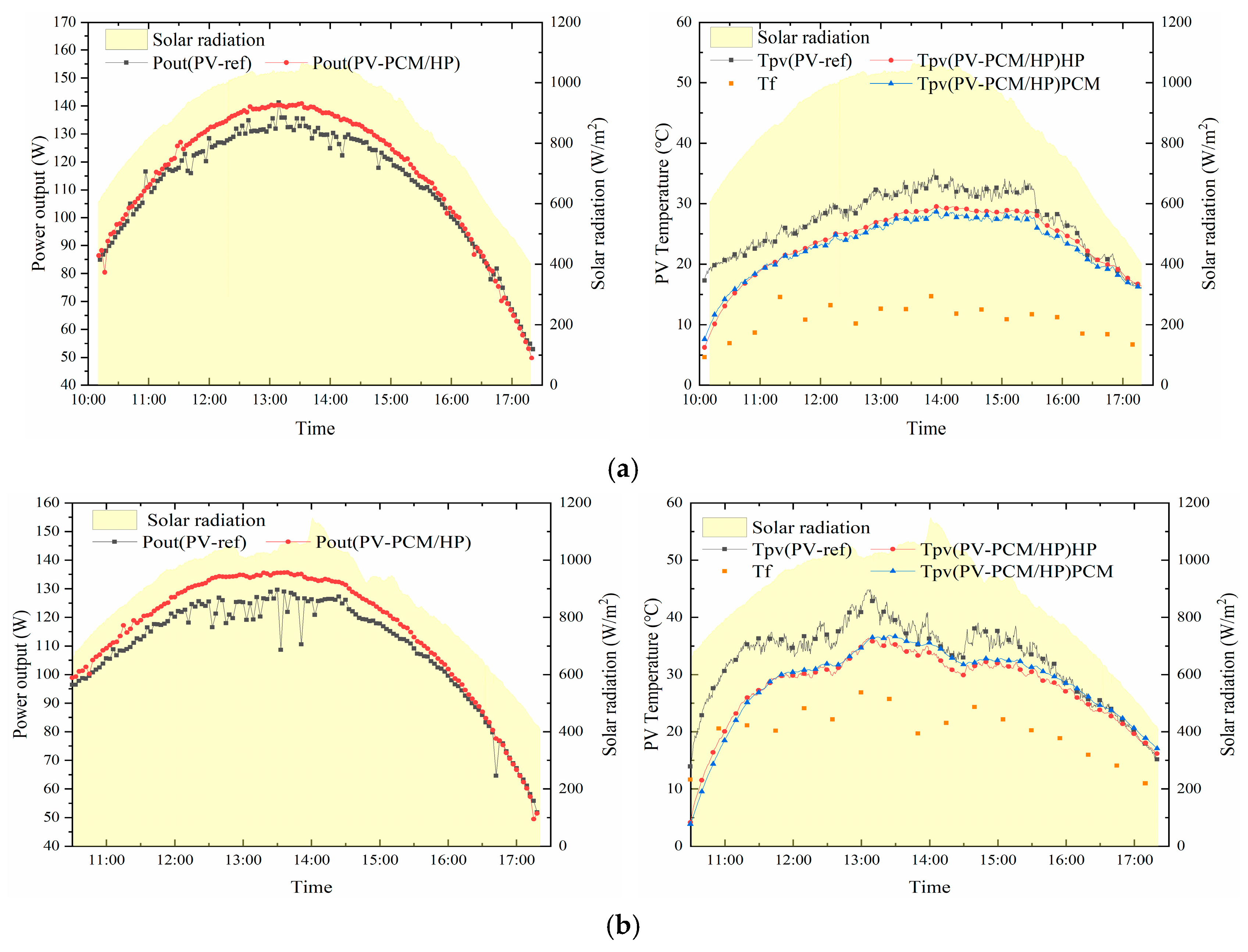

Figure 5. On Day 1, the solar irradiance increased slowly from 9:00 to 12:00, resulting in a relatively gentle increase in the backsheet temperature. A comparison of the data from Day 2 and Day 3 indicates that solar irradiance has a significant impact on the increase in the backsheet temperature. Although the average solar irradiance was similar over the three days, the ambient temperature on Day 3 was significantly higher than that on the other two days, and the average wind speed was lower, leading to a poor convective heat transfer effect of the backsheet and an overall higher backsheet temperature. Meanwhile, both T_(pv(PV-ref)) and T_(pv(PV–PCM/HP)) were basically below 40 °C on Day 1 and Day 2, and a large amount of heat was absorbed by the PCM in the form of sensible heat. Thus, when compared with the data on Day 3, it can be found that the PCM module can better control the backsheet temperature during operation, reducing the maximum temperature difference of the backsheet.

In

Table 7,

is the power generation increase rate, which can be calculated as

and represent the power generation of the PV modules and the PV module equipped with the thermal management system, respectively.

A gradual decrease in the power generation output of the PV panels is observed during the 3 days. A comparison of the relationships between solar radiation, temperature, wind speed, and power generation across the 3 days reveals that although solar radiation intensity peaks on the second day, the average wind speed and average temperature are higher, resulting in lower power generation from the PV modules than that on the first day. A marked increase in temperature is observed on the third day in comparison to that of the preceding two days. The backsheet temperature of the PV panels attains its maximum level, consequently leading to the lowest power generation output. Thus, the temperature of the photovoltaic module backsheet is the most direct indicator of power generation, influenced by the combined effects of solar radiation, ambient temperature, and wind speed. It can be observed from

Figure 6 that the power generation of the photovoltaic modules using the thermal management module is significantly higher than that of the pure PV system. Meanwhile, due to the highest solar radiation intensity on Day 2 and the largest difference in the average backsheet temperature between the PV and PV–PCM/HP systems during operation, the power generation increase can reach 7.95%, which is higher than 5.67% on Day 1 and 6.02% on Day 3. Additionally, the PCM/HP thermal management system can also reduce temperature fluctuations in photovoltaic panels.

3.2. Huanjiang

The solar irradiance in the Huanjiang is affected by the local cloudy weather. During the test from 29 to 30 October 2022, the average daily solar irradiance was relatively low, concentrated in the range of 400–600 W/m

2. However, on the 31st, the light intensity was sufficient, with an average solar irradiance reaching 800 W/m

2. The atmospheric temperature mainly varied between 25 °C and 30 °C, with a small temperature difference between morning and evening and a relatively high average daily temperature. Other relevant data are shown in

Table 8. The temperature changes of PV and PV–PCM/HP are presented in

Figure 7, from which it can be seen that the variation law in the backsheet temperature is consistent with that of solar irradiance. Due to the generally low photovoltaic intensity and low ambient temperature on Day 2, the operating temperature of the backsheet on that day was relatively low, and the temperature difference between the PV panel and the PCM/HP system was not obvious. Although the ambient temperatures on Day 1 and Day 3 were close, the average wind speed on Day 3 was twice that on Day 1, resulting in different degrees of convective heat dissipation. Consequently, the backsheet temperature on Day 1 was generally 2–3 °C higher than that on Day 3. This indicates that wind speed has a significant impact on the heat dissipation of PV panels. Enhancing the convective heat transfer effect of the backsheet would be more conducive to maintaining PV panels within the ideal operating temperature range in terms of temperature control.

During the experiment conducted in Huanjiang, the power generation of the photovoltaic modules using thermal management modules was higher than that of the pure PV system, but the efficiency improvement was only 2–3%. This is mainly because only the average solar irradiance on Day 3 reached above 800 W/m2, while Day 1 and Day 2 were cloudy, resulting in relatively low power generation. Meanwhile, when the PV and PV–PCM/HP systems were in operation, the ambient temperature was relatively high, reaching up to 30 °C, which led to insufficient heat dissipation and excessively high backsheet temperature. Both the PV system and the PV–PCM/HP system exhibit poor performance under high-temperature and low solar irradiance conditions. Even though the backsheet is treated using the temperature control characteristics of phase change materials, the power generation is not significantly increased. This is due to the limited heat dissipation of photovoltaic panels under high-temperature conditions. Over the three days of testing, the third day recorded the lowest photovoltaic conversion efficiency.

3.3. Shangri-La

From 10 to 12 November 2022, the solar irradiance in Shangri-La can be divided into two stages. In the first stage, the solar irradiance steadily increased from a low level to a peak, then moderately weakened and stably decreased. During the test, the average daily solar irradiance values were 839.79 W/m

2, 794.23 W/m

2, and 630.91 W/m

2, respectively, with sufficient light intensity. The air temperature mainly varied between 0 °C and 20 °C, with a large temperature difference between day and night, and the average temperature was relatively lower than that of other tested locations. The average wind speed was about 0.2 m/s, which was relatively weak. Other relevant data are shown in

Table 9. The temperature changes of PV and PV–PCM/HP are shown in

Figure 8. The data of Day 1 and Day 2 further indicate that under the action of high solar irradiance, phase change materials can reach the phase change temperature faster and achieve efficient temperature control through latent heat absorption. As the solar irradiance weakened, the temperature of the PV panel dropped rapidly. However, due to the heat storage characteristics of phase change materials, the backsheet temperature of PV–PCM/HP could remain stable at 40 °C for a relatively long time. For Day 3, since the solar irradiance of the day was much lower than that of the previous two days, both

and

were basically below 40 °C, so the overall temperature difference was smaller than in the test results of the previous two days.

As can be seen from

Figure 8, during Day 1 and Day 2 of the test in Shangri-La, the environmental parameters were basically the same, and the performance characteristics of the PV system and the PV–PCM/HP system were almost identical for these two days. In terms of power generation, due to the influence of ambient temperature, the lower temperature on Day 2 was more conducive to heat dissipation, which led to a decrease in the backsheet temperature and a higher power generation compared with the results for Day 1. However, the effect of using the PCM/HP temperature control system slightly decreased from 5.36% on Day 1 to 5.21% on Day 2, which was only caused by the difference in total power generation. From the experimental data of the three days, it can be found that under the conditions of medium temperature and high solar irradiance, during the operation of the PV–PCM/HP system, the phase change material can reach the phase change temperature, and the power generation of the photovoltaic modules using the thermal management module is significantly higher than that of the pure PV system.

A distinctive occurrence is documented in Shangri-La: PCM/HP modules exhibited effective temperature control performance until approximately 14:30. Subsequent to this moment, however, both PV panels exhibited near-identical temperatures and power generation levels. This discrepancy is probably attributable to the fact that Shangri-La has the highest solar radiation intensity among the four regions. The PCM has fully melted and increases the thermal resistance between the PV panel and the surrounding air. It is difficult for the heat pipes to dissipate such high heat loads into the surrounding air. Consequently, the effectiveness of the thermal management system is significantly diminished.

3.4. Derong

The relevant measurement data of the Derong area from 17 to 18 November 2022, are shown in

Table 10. During the experimental period, the local average daily solar irradiance was close to 870 W/m

2, with sufficient light intensity. The air temperature mainly varied between 0 °C and 20 °C, with a large temperature difference between day and night, and the average wind speed was about 0.27 m/s. The main difference in the meteorological environment was the different average daytime temperatures between the two tested days, which were 10.78 °C and 15.31 °C, respectively. The temperature changes of PV and PV–PCM/HP are shown in

Figure 9. The data of Day 1 and Day 2 indicate that the ambient temperature has an impact on the backsheet temperature, and excessively high ambient temperature will increase the maximum temperature limit of the PV panel. Meanwhile, it can be found from the experiment in the Derong area that the phase change material almost did not reach the phase change temperature, resulting in the PCM absorbing excess heat through sensible heat. In addition, due to the heat dissipation effect of the heat pipe,

was always slightly lower than

, but the temperature difference was not significant.

In the test conducted in Derong, although the power generation on Day 2 was lower than that on Day 1, the increase in power generation was slightly higher. This is because the backsheet temperature of the system on Day 2 was generally higher, and the phase change material completely melted during operation, achieving a full temperature control effect. As a result, the PV–PCM/HP system saw a greater increase in power generation. On Day 1, however, due to the lower average backsheet temperature, the power generation itself was higher, but the phase change material did not melt completely, only absorbing part of the energy. Its temperature control effect was not fully exerted, so the power generation only increased by 3.78%. Meanwhile, since the solar irradiance on Day 1 and Day 2 was roughly similar, with the main difference being in ambient temperature, it can be observed that under the conditions of low temperature and high solar irradiance, during the operation of the PV–PCM/HP system, the power generation of photovoltaic modules using the thermal management unit is higher than that of the pure PV system. Nevertheless, excessively low ambient temperatures will reduce the amount of increase in power generation because lower ambient temperatures facilitate heat dissipation from PV panels into the air.

3.5. Comparison Study

For the above four regions, the experiments generally found that , and rise from the low temperature at the start of the experiment to a peak as the solar irradiance increases during the day. This is because during PV power generation, not all radiant energy can be converted into electricity; instead, a portion of the heat is transferred and accumulated, thereby causing an increase in the backsheet temperature of the PV module. However, due to the heat absorption by phase change materials and the enhanced heat transfer by heat pipes, the temperature of PV panels with PCM/HP modules is always lower than that of pure PV panels during the heat storage process. Moreover, it can be observed that and do not exhibit significant differences throughout the entire working process, indicating that heat pipes have excellent temperature uniformity. When the operating temperature of the PV reaches around 40 °C, the positive effect of the PCM/HP module begins to manifest. At this point, the temperature curve of rises sharply, while the temperature increase of and shows an obvious phase change plateau. This indicates that the PCM is melting and absorbing heat, playing an active role, and the unconverted energy is absorbed by the PCM in the form of heat. When the PV module’s operating temperature remains below 40 °C, the thermal regulation of the PCM/HP system is primarily governed by the heat pipe’s efficient conductive heat transfer mechanism. Under these conditions, the heat pipe effectively dissipates thermal energy, resulting in a consistently lower backsheet temperature in the PV–PCM/HP module compared to that in the conventional PV panel without thermal management.

Meanwhile, the power generation trends of both the PV system and the PV–PCM/HP system are consistent, being significantly affected by solar irradiance and backsheet temperature. Overall, the PV power generation exhibits noticeable fluctuations, while the PV–PCM/HP system is relatively stable, which is mainly attributed to the temperature control characteristics of phase change materials. During the slow change of light intensity, the backsheet temperature of the PV–PCM/HP system shows a relatively small change trend, and the overall temperature is lower than that of the pure PV system, resulting in a general increase in its power generation. Under normal circumstances, after the system starts working, the power generation of the PV system will first be lower than that of the PV–PCM/HP system. However, after the light intensity begins to decrease in the afternoon, the real-time power generation of the two systems will gradually approach and occasionally, eventually be higher than that of the PV–PCM/HP system. This is because during the heat release stage of the phase change material, it acts as an additional heat source to heat the backsheet, thus continuously maintaining its working temperature at the phase change temperature. At this point, only the heat pipe can dissipate heat for the entire system, leading to a decrease in power generation. This test result also indicates that the optimal parameters for the PCM/HP thermal management module vary under different meteorological conditions.