1. Introduction

Hydrogen, an earth-abundant chemical element, has several useful properties that make it a critical component in the challenging transition towards a decarbonized energy infrastructure comprising renewable energy sources and energy storage [

1,

2]. Molecular hydrogen (H

2) is a colorless gas with a specific energy density of 140 MJ/kg, which is four times higher than diesel and the lithium-ion battery [

3]. The high specific energy density is due to the low relative atomic mass of hydrogen and the H-H covalent bond dissociation energy of 435.9 kJ/mol [

4]. When oxidized by combustion in air or by reaction with molecular oxygen (O

2) in a fuel cell, the chemical energy in H

2 is converted to heat and electricity, respectively, and only water is produced as the reaction product [

4]. These attributes make H

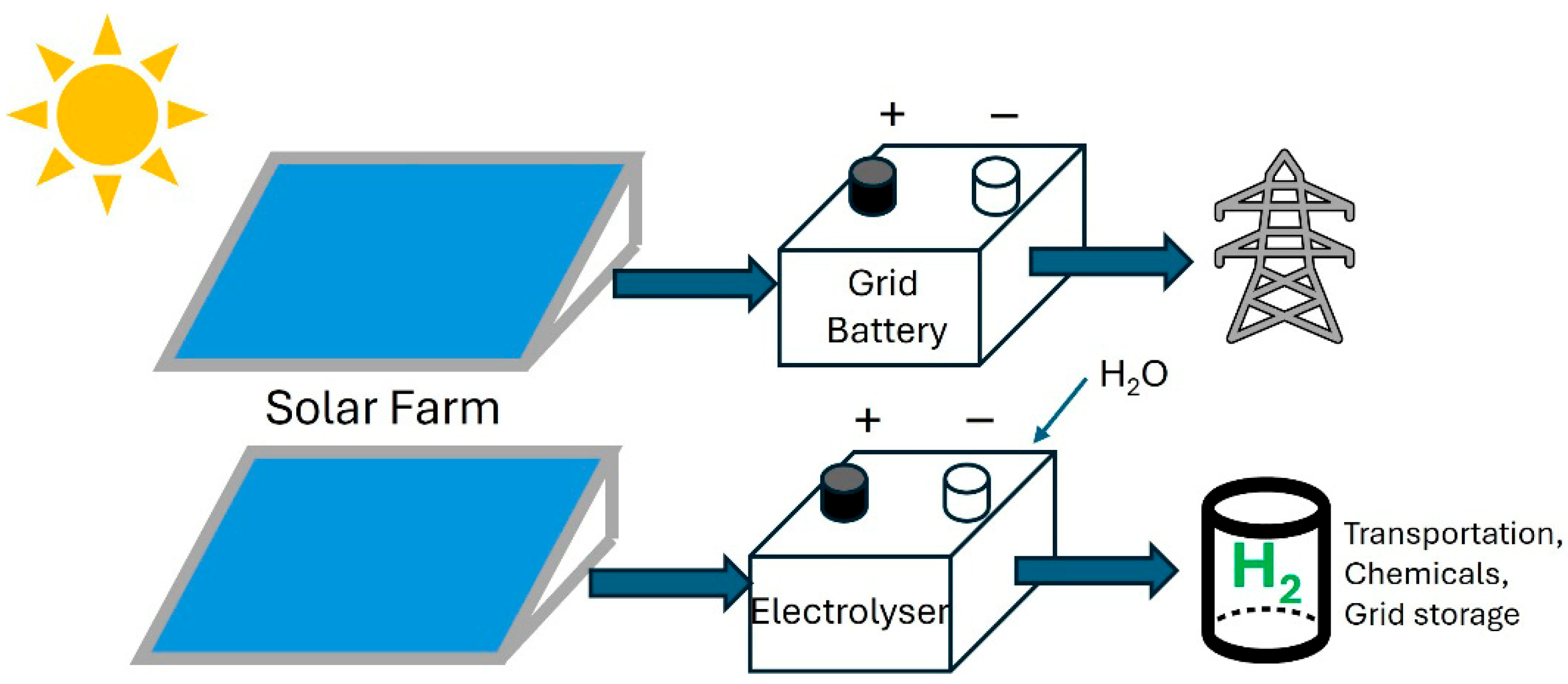

2 an attractive energy carrier and storage medium for mitigating the uncertainty in supply in an electricity grid with a high proportion of intermittent renewable energy sources (

Figure 1). The large-scale generation of H

2 from renewable energy sources such as solar farms and wind farms can also facilitate the decarbonization of steel, chemical, cement manufacturing and the transportation industry, such as heavy goods vehicles and marine shipping [

5]. For heavy industries that are difficult to electrify, H

2 is really the only alternative to fossil fuels as a source of sustainable energy [

6].

Hydrogen is already produced on an industrial scale as a feedstock chemical for the synthesis of ammonia for manufacturing fertilizer and for refining petrochemicals. However, the present steam methane (CH

4) reforming process for making H

2 uses CH

4 from natural gas as both a reactant and as a fuel to heat the methane and steam mixture to the high temperatures required for H

2 and CO

2 formation [

7]. Both the steam methane reforming reaction and the combustion release large amounts of CO

2, which is the main greenhouse gas causing global warming. It has been reported that the current method of H

2 production results in annual CO

2 emission equal to the combined emissions of Indonesia and the United Kingdom [

3]. In another life cycle assessment study using the ecoinvent database, Eryazici et al. estimated that in 2019, the global chemical industry emitted about 2.6 billion tons of CO

2 equivalent into the atmosphere, of which 42% is direct emission [

8]. A significant portion of this direct emission is due to hydrogen generation from the steam methane reforming process for ammonia production [

8]. Since the purity of H

2 produced by the methane steam reforming method is also not high, there is a need for an alternative method that is both economical and environmentally friendly.

The most promising carbon neutral process to produce H

2 is to use water electrolysis or electrochemical water splitting (EWS) powered by renewable electricity such as solar and wind [

9,

10]. Hydrogen produced by this method is often referred to as green H

2 [

11]. The other color designations of H

2 are gray for H

2 produced from fossil fuels and blue for H

2 produced from fossil fuels with carbon capture and storage [

11]. Interestingly, the EWS method driven by hydropower was in fact the main H

2 production process from 1927 to 1990, before the advent of the cheaper steam methane reforming process [

12]. Although the EWS method is mature and well established, the amount of green H

2 produced in 2022 was a paltry 109 kilotons or 0.11% of the 95 million metric tons of H

2 produced that year [

13]. There are also few reports on solar- or wind-driven EWS systems in the literature [

14]. As mentioned recently in ref. [

15], this shortfall in green H

2 generation is due to three reasons. First, the proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzer, which is at present the only mature EWS system tolerant of intermittent supply voltages, operates in highly acidic conditions [

16]. These conditions can corrode the electrodes and their coatings. As a result, noble metals from the platinum (Pt) group and their oxides such as Pt and iridium dioxide (IrO

2) are currently used as electrocatalysts to accelerate the kinetics of the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) at the cathode and the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) at the anode. These scarce metals are, however, very expensive and limited in supply, making the upscaling of green H

2 production by PEM electrolyzers impractical. The other two limiting factors for green H

2 production by EWS are the need to develop highly durable ion conducting membranes which are not based on fluoropolymers and new electrolyzer designs that are compatible with intermittent renewable power sources [

15]. In this article, the focus will be on the development of earth-abundant HER electrocatalysts in EWS systems.

In recent years, many types of earth-abundant HER electrocatalysts based on mono- or multi-transition metal (TM) compounds have been actively investigated for the EWS application [

17]. These include TM borides, carbides, phosphides, sulfides and selenides. A comprehensive review of these main categories of crystalline earth-abundant HER electrocatalysts has been published [

18]. The TMSs are especially promising because they are highly effective for HER and sulfur is an abundant chemical element [

19,

20]. The TMS compounds are also the only category of HER electrocatalysts that mimic the catalytic sites in the hydrogenase and nitrogenase enzymes in microorganisms for the biological production and splitting of H

2 [

21]. A major recognition in the field of earth-abundant electrocatalysts in recent years is that the bulk and nanocrystalline form of TM compounds are less effective than their amorphous (non-crystalline) counterparts. This is because the short-range order in amorphous catalytic materials results in many structural defects such as uncoordinated atoms, which can act as active adsorption sites for HER [

22,

23]. In this article, we focus on recent developments in the synthesis, deposition and characterization of amorphous TMS HER electrocatalysts. Amorphous metal sulfides derived from the first and third rows of the TM series will be covered first, including mono-metallic and multi-metallic TMS compounds. Since amorphous nickel sulfide (a-NiS

x)- and Ni-containing a-TMS compounds have the best overall electrocatalytic properties for the HER at present, emphasis will be placed on developments in these materials. A theoretical explanation for the important role of Ni in these a-TMS electrocatalysts will also be provided in

Section 4. Amorphous TMS from the second row are not discussed in detail because there had been multiple prior reviews on amorphous molybdenum sulfide (a-MoS

x), and amorphous ruthenium sulfide (a-RuS

x) is not earth-abundant [

24,

25,

26,

27]. Instead, we use a-MoS

x as the benchmark amorphous electrocatalyst to evaluate the performance of TMS electrocatalytic materials from the first and third row of the transition metal series. Comparison will also be made wherever possible with the crystalline counterpart of a first- or third-row amorphous TMS. This article will conclude with an outlook on the search strategy for promising amorphous TM sulfides from the third-row TM elements.

2. EWS Reactions and the Role of Electrocatalysts

The overall EWS reaction is simple and can be written as Equation (1) [

28]:

This reaction is strongly endothermic with an enthalpy change of 285.84 kJ/mol at the standard conditions of 298.15 K and 1 atm pressure. Thus, energy input is needed for EWS to occur. The theoretical equilibrium thermodynamic applied potential for Equation (1) is 1.23 V [

28]. This is the minimum voltage required for EWS, and the actual applied potential with acceptable H

2 generation rates will be higher due to ohmic and other losses. In an EWS electrolyzer, the above redox reaction takes place via two concurrent half-cell reactions (HER and OER) at the cathode/electrolyte and anode/electrolyte interfaces, respectively. Despite decades of investigation, the detailed reaction mechanism of the HER and OER is not fully understood and are somewhat controversial, especially for the more complicated OER [

29]. However, it is generally agreed that the EWS mechanism depends on the pH condition within the electrolyzer. For acidic conditions such as those in the PEM electrolyzer, the three steps of the HER are as follows [

17]:

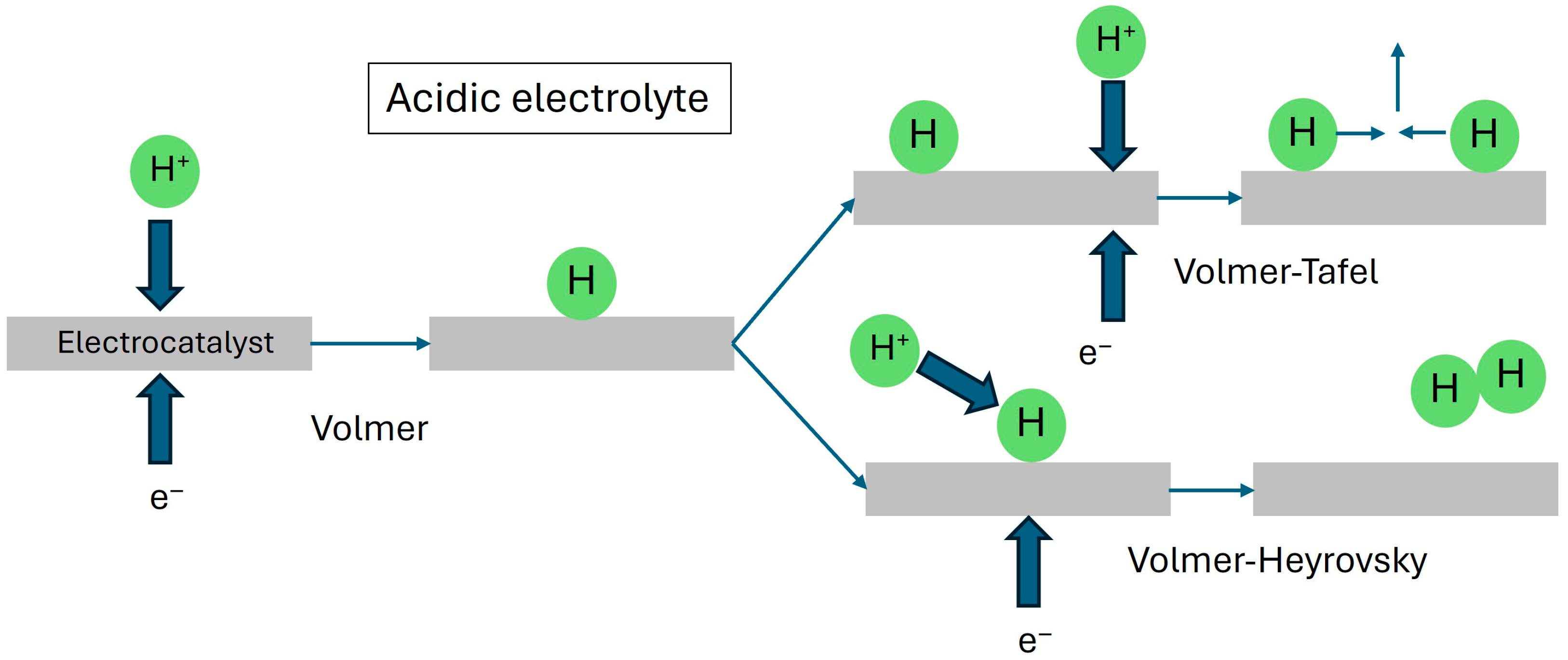

This mechanism is essentially a 2-electron reduction process (

Figure 2). In the Volmer step of Equation (2), protons originated from the oxidation of water at the anode traverse the PEM to reach the cathode. After adsorption at active catalytic sites on the electrocatalyst surface, these protons are reduced and become adsorbed atomic hydrogen H* (the asterisk * is used to designate an adsorption site on a heterogeneous catalyst in these equations). The adsorbed H* can form H

2 by either the Heyrovsky step or the Tafel step. In the former (Equation (3)), H* reacts with a reduced proton, while in the latter (Equation (4)), two proximate adsorbed hydrogen atoms combine to form a H

2 molecule. It is important to note that all three steps require active adsorption sites on the catalyst surface, which ideally should not undergo any chemical change during EWS.

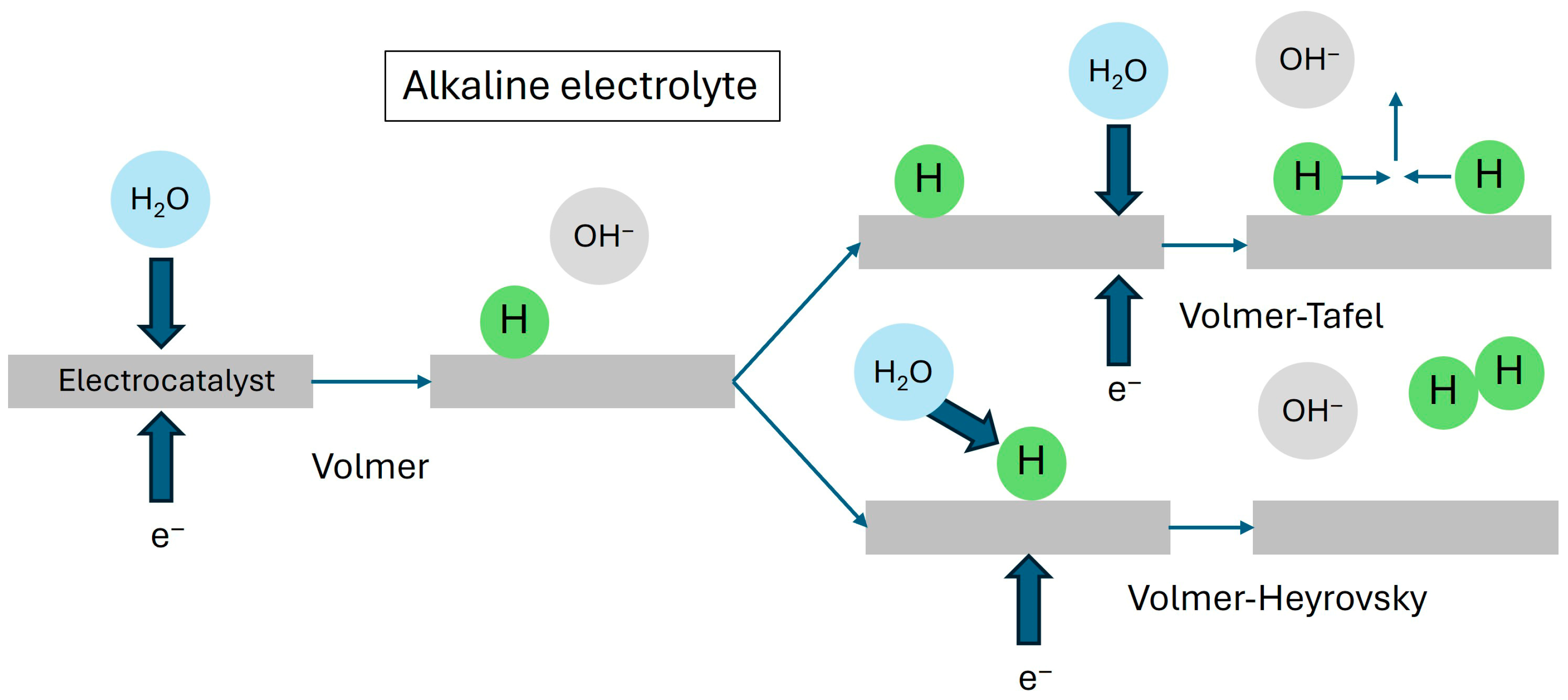

In the alkaline water electrolyzer (AWE) and the more recent anion exchange membrane (AEM) electrolyzer [

30], the three steps of the HER can be written as follows [

17]:

In alkaline and neutral conditions, water molecules are reduced at the cathode to form H* (

Figure 3), and the OH

− ions present either in the electrolyte or transit through the anion exchange membrane are oxidized at the anode to O

2. Note that Equations (5)–(7) also involve the participation of active sites on the catalyst surface.

For the OER, there are currently two proposed models for the reaction mechanism. In the conventional adsorbate evolution mechanism [

31], the OER involves a series of four coordinated proton electron transfer (CPET) reactions that are also dependent on pH conditions. For acidic electrolytes, the CPET reactions can be written as follows:

For alkaline electrolytes, the reaction steps are the following:

In Equations (8)–(15), O*, HO* and HOO* are reaction intermediates that are adsorbed on the electrocatalyst surface. Since the focus of this article is HER, we refer the reader to refs. [

31,

32] for the lattice oxygen-mediated mechanism for OER. Ref. [

32] also includes an excellent review of a-TM OER electrocatalysts.

The slowest step(s) in Equations (2)–(7) determines the rate of the water splitting reaction and is termed the rate-determining step. This step in the reaction mechanism for a HER electrocatalyst can in principle be deduced from the slope of the Tafel plot, which is a semi-logarithmic plot of the Tafel equation [

18]:

In Equation (16), h is the overpotential, a is an intercept parameter, b is the Tafel slope and j is the stabilized current density at overpotential h. The Tafel equation can be derived from the fundamental Butler–Volmer equation of electrochemistry and is discussed in detail in [

33]. The Tafel slope

, where R is the molar gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, b is the electron transfer coefficient (or asymmetry parameter), n is the number of moles of electrons and F is Faraday’s constant. According to the classical theory for HER [

34,

35], the value of b for a rate-determining Volmer, Heyrovsky and Tafel step at room temperature should be 4.6 RT/F (~118 mV/dec), 1.53 RT/F (~39 mV/dec) and 1.15 RT/F (~29 mV/dec), respectively. It is not trivial to deduce the rate-determining step from the Tafel plot. First, it is crucial to measure the steady state current density at a given overpotential. Second, as discussed in [

36], the ideal straight line Tafel plot is only obtained when multiple experimental conditions are fulfilled. For the multi-step HER and OER, this is seldom the case. As a result, the Tafel plot can deviate from linearity. Van der Heijden et al. have recently proposed the Tafel slope plot to identify the cardinal Tafel slope for a physically meaningful Tafel slope extraction [

36]. Deeper physical insight into the Tafel slope can be gained from theoretical simulations. A recent breakthrough is the microkinetic model for the HER and the reverse hydrogen oxidation reaction (HOR) on Pt(111) surfaces [

37]. In their computational study, Gao and Wang used the continuum solvation density functional theory (CS-DFT) approach to calculate the potential dependent energy barriers and hydrogen coverage for all elementary reaction steps in the HER and HOR on Pt(111). In highly acidic conditions, the HER energy barriers for the Volmer–Heyrovsky path are found to be lower than the competing Volmer–Tafel path. As a result, the HER proceeds primarily via the Volmer–Heyrovsky mechanism and the Heyrovsky step is rate limiting. The calculated polarization curve based on potential dependent reaction barriers yields a computed Tafel slope of 42 mV/dec, which is close to the experimental Tafel slope of 39 mV/dec [

37]. The microkinetic model demonstrates that the Tafel slope results from multiple reaction pathways rather than one reaction pathway.

The electrocatalyst used for the HER in electrolyzers serves two functions. First, by providing active sites for adsorption, it lowers the activation energy barrier for the Volmer, Heyrovsky and Tafel reactions and increases the kinetics of these reactions. Second, the electrocatalyst provides a conductive surface at which electron transfer reactions can take place readily. These two functions are especially critical for the more sluggish OER in EWS [

28]. As discussed in ref. [

38], there are two major mechanisms of adsorption onto the catalyst surface. In physisorption, the adsorbate is only weakly bound to the adsorption site by van der Waals’s electrostatic forces. As a result, the adsorbate can be physisorbed onto any part of the catalyst surface. On the other hand, in chemisorption, the adsorbate needs to form a chemical bond with the catalyst surface. As a result, this usually takes place at specific sites on the catalyst surface.

The desired characteristics of an earth-abundant EWS electrocatalyst include the following: (i) high electrode catalytic activity, (ii) small Tafel slope b, (iii) high Faradaic efficiency (FE), (iv) large electrode surface area, (v) high intrinsic activity at catalytic sites, (vi) durability in electrolyte with wide pH range, (vii) bifunctionality, (viii) superhydrophilicity, (ix) good adhesion to electrode support and (x) high electrical conductivity. The electrode catalytic activity is the most basic characteristic of an electrocatalyst and is usually reported as the onset overpotential of the measured polarization curve (current density–voltage) or the overpotential corresponding to a working electrode current density of 10 mA/cm2 (η10). A low onset overpotential and low η10 is desirable as they imply that an electrolyzer can operate efficiently at high current density. A small slope b in the linear portion of the Tafel plot implies fast electrode kinetics and is desirable for industrial water electrolyzers. The current density of the working electrode comprises a Faradaic component related to H2 generation and a non-Faradaic component due to non-EWS side reactions. For high FE, the Faradaic component should be the only, or dominant, cathode current component. The FE is usually determined by dividing the actual mass of H2 generated during EWS by the theoretical mass of H2 generated by the current density used and the ratio is converted to a percentage.

The Faradaic current component depends on the actual or true electrode surface area and the intrinsic catalytic activity of each catalytic site. The electrode area can be increased by using either a porous electrode such as a metal foam or a nanostructured electrocatalyst that has greater surface roughness or porosity. In addition to increasing the surface area, a porous morphology is also beneficial to mass transport. The actual surface area of the working electrode is usually determined directly by gas adsorption porosimetry or indirectly by measuring the geometric electric double layer (EDL) capacitance (C

dl), defined as the EDL capacitance (C) normalized by the geometric electrode area [

39]. This is because, according to the Helmholtz theory [

40],

, where e

0 is the permittivity of free space, e

r is the dielectric constant of the electrolyte, A is the electrode area and d is the thickness of the EDL. Physical insight into the EDL beyond that described by the Gouy–Chapman–Stern theory can be obtained through computational modeling. The most often used techniques are classical DFT, classical molecular dynamics and grand canonical Monte Carlo simulations [

40]. In one study [

41], classical DFT was used to study the effect of pore size and electrode geometry on EDL capacitance. A spherical pore-shell geometry was considered in which two concentric hollow spherical electrodes are separated by a pore-like space with variable pore size. This geometry turns into a slit pore when the inner sphere radius tends towards infinity. The simulated EDL capacitance for a pore filled with an ionic liquid showed an oscillatory dependence on both the pore size and the radius of the inner electrode.

The intrinsic activity of a catalytic site is quantitatively described by the turnover frequency (TOF), defined as the number of reactants converted into the EWS reaction product (H

2) by a catalytic site per unit time [

18]. TOF is an important fundamental property of an electrocatalyst. However, it is not straightforward to measure and is therefore seldom reported in the literature. One other indicator of intrinsic catalytic activity is the exchange current density j

0, which can be extracted from the log|j| intercept and the gradient of the Tafel plot [

18].

Since an EWS electrolyzer typically operates in strongly acidic or alkaline conditions, it is essential for any non-noble metal electrocatalyst to be chemically inert and survive the corrosive conditions during operation. The lifetime or chemical stability of an electrocatalyst can be measured by cyclic voltammetry (CV) or chronoamperometry (CA). A very useful and desirable property of EWS catalysts is bifunctionality. This refers to the use of the same catalyst material for both the HER and OER. An electrocatalyst with bifunctionality does not have the pH compatibility issues that may arise when different HER and OER electrocatalysts are used in the same electrolyzer. Once H2 has been formed on the cathode, it is important for the gas bubble to lift off from the electrode surface rapidly so that the catalyst surface can be freed for new reactants. A superhydrophilic surface with very low water contact angle or high wettability is beneficial for gas bubble removal. In addition, since the HER involves electron transfer at the surface of the electrocatalyst, good adhesion by the electrocatalyst to the electrode support and high electrical conductivity are also important requirements for an effective electrocatalyst. This rather onerous set of material requirements makes it extremely challenging to design and fabricate HER electrocatalyst materials for EWS.

4. Amorphous Multi-Metallic First-Row TMS HER Electrocatalysts

The incorporation of suitable transition metal dopants is a proven technique for enhancing the catalytic properties of a-TMS electrocatalysts [

55]. This enhancement strategy has also been demonstrated for polycrystalline TMS electrocatalyst materials [

56]. In 2022, Dong et al. reported a hydrothermal/sulfurization technique for synthesizing bifunctional a-Co

xNi

yS electrocatalyst with a nanoflake morphology on carbon cloth (CC) [

57]. In this two-step process, an a-Co

xNi

yO precursor material was first synthesized by dissolving cobalt (II) nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO

3)

2·6H

2O), nickel (II) nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO

3)

2·6H

2O), glucose and 2-aminoterephthalic acid (NH

2-TPA) in methanol. NH

2-TPA is a ligand often used for the fabrication of crystalline metal–organic frameworks (MOF). When the NH

2-TPA concentration drops below that needed for MOF formation, the NH

2-TPA serves as a spacer for coordinating the Co and Ni ions in a hybrid non-crystalline network. An acid-activated CC substrate is placed within this solution for 30 min before being transferred to an autoclave for hydrothermal reaction at 180 °C for 12 hrs. During the hydrothermal reaction, glucose is hydrolyzed, and a glucose-derived polymer is deposited preferentially on the activated CC. The interaction between this polymer and the non-crystalline Co/Ni network results in the deposition of a-Co

xNi

yO. Suitable amounts of glucose and NH

2-TPA must be present for the precursor to be deposited. After formation, this precursor is converted into a-Co

xNi

yS by immersion in Na

2S solution at room temperature for 14 hrs.

The HER catalytic activity of the synthesized a-Co

xNi

yS/CC was evaluated by LSV using a three-electrode electrochemical cell with a 1 M KOH solution. The a-Co

xNi

yS/CC, graphite rod and Hg/HgO were used as the working, counter and reference electrodes, respectively. For the optimized composition of a-Co

4NiS, the iR corrected η

10 is 192 mV which is significantly higher than that of the benchmark Pt/C electrode (

Table 2). The η

10 for samples with other Co:Ni atomic ratios were all higher. On the other hand, the Tafel slope of a-Co

4NiS (119 mV/dec) is the lowest amongst all composition ratios investigated, suggesting effective charge transfer during catalysis. The value of the Tafel slope of a-Co

4NiS is in the range that corresponds to the Volmer–Heyrovsky HER mechanism [

35]. The effective charge transfer in a-Co

4NiS is also demonstrated by the R

ct measured by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (0.1–10

5 Hz). The R

ct value of 2.32 W for a-Co

4NiS is the smallest amongst the Co:Ni composition ratios investigated. Dong et al. also investigated the catalytic activity of a-Co

xNi

yS/CC for the OER. Oxygen evolution was catalyzed when a-Co

xNi

yS/CC was used as the anode. Hence, a-Co

xNi

yS/CC is a bifunctional electrocatalyst and this property can simplify the practical application of this material for EWS.

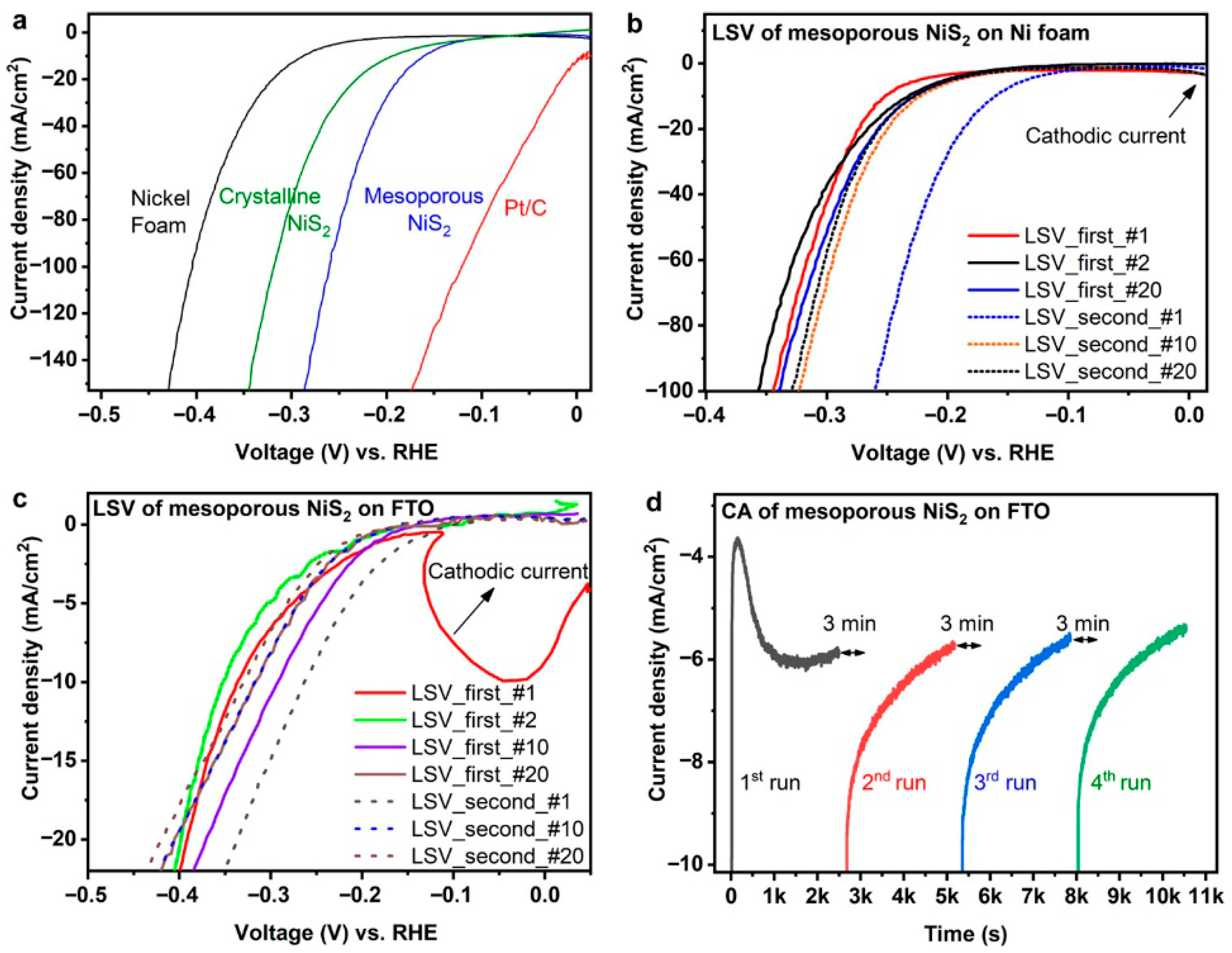

Pre-catalyst behavior like that mentioned in the previous section has been observed in multi-metallic first-row TMS HER electrocatalysts. In ref. [

58], Lu and co-workers used a two-step hydrothermal solution process to synthesize amorphous CoNiS

x on NF. This process has similarities with the one reported by Dong et al. [

57]. First, a Co-Ni carbonate hydroxide hydrate (CoNiCHH) precursor is formed on NF by dissolving Co(NO

3)

2, ammonium fluoride (NH

4F) and urea in ultra-pure water to form an aqueous solution. A pre-cleaned NF and this solution are then transferred to a Teflon lined autoclave for hydrothermal reaction at 90 °C for 6 h to form a CoNiCHH/NF precursor. The precursor is converted into a-CoNiS

x by immersion in a Na

2S solution at 25 °C for 14 hrs. During this immersion, the carbonate (CO

32−) and hydroxide ions (OH

−) are replaced by sulfide ions (S

2−) in CoNiCHH. The temperature of the Na

2S solution during ion exchange is crucial. If the temperature is below 25 °C, amorphous CoNiS

x with a coupled nanoplate-nanowire (NPNW) morphology and surface roughness is obtained. By contrast, when CoNiCHH was immersed in Na

2S at 120 °C, only Co

3S

4 nanocrystals were deposited on NF. The amorphous structure of the CoNiS

x is demonstrated by XRD, HR-TEM and SAED. CoNiS

x does not yield XRD peaks, and crystallinity cannot be detected by HR-TEM imaging and by SAED. A uniform distribution of Co, Ni and S was observed by elemental mapping [

58].

The electrocatalytic properties of CoNiS

x were investigated in 1 M KOH using a three-electrode cell. The CoNiS

x/NF, graphite and saturated calomel electrode (SCE) are the working, counter and reference electrodes, respectively. Dynamic activation behavior like that reported by Karakaya et al. in ref. [

44] was observed during the initial LSV scan of a pristine CoNiS

x electrode. This includes an initial cathodic current without H

2 bubble formation on the cathode. Compositional characterization showed that the cathodic current is associated with the reduction in Co-S and Ni-S to elemental Co and Ni, respectively, at the surface of the NPNW structures. This reduction results in a leaching of S

2− ions into the electrolyte. After the third LSV scan was completed, the electrode was further characterized by HR-TEM, SAED and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). These showed that the electrode has undergone further de-sulfurization and the final electrode is in fact nanocrystalline Ni and S co-doped CoO. The presence of oxygen in the electrode is indicated by the appearance of a new lattice O XPS peak, and this oxygen is supposed to stabilize the Co metal sites. Since the electrode responsible for HER is Ni and S co-doped CoO, the CoNiS

x should be considered as a pre-catalyst.

One other notable multi-metallic first-row EWS electrocatalyst reported recently is the bifunctional amorphous composite (NiFe)S

x/NiFe(OH)

y prepared by Che et al. [

59]. In this study, a one-step electrodeposition process was used for the synthesis of the (NiFe)S

x/NiFe(OH)

y. The three-electrode electrochemical cell consists of a cleaned NF substrate, a Pt counter electrode and an SCE reference electrode. The aqueous solution used for deposition comprises nickel sulfate hexahydrate (NiSO

4·6H

2O), iron nitrate nonahydrate (Fe(NO

3)

3·9H

2O), thiourea and trisodium citrate dihydrate (Na

3C

6H

5O

7·2H

2O), and deposition was carried out at −80 mA/cm

2 for 6 min. The (NiFe)S

x in the resulting composite is as the main HER electrocatalyst, while the NiFe(OH)

y is the OER electrocatalyst. This composite material approach is the unique and innovative aspect of this work. For both HER and OER catalyst components, Ni and Fe are needed because, while the Fe

3+ ions provide favorable catalytic sites for adsorption, both FeS

x and Fe(OH)

3 do not have good electrical conductivity, as shown by separate characterization experiments discussed below. Ni is therefore needed to reduce the charge transfer resistance of this composite catalyst.

The HER performance of (NiFe)Sx/NiFe(OH)y/NF was evaluated in 1 M KOH using a cell with a graphite counter electrode and SCE reference electrode. An extremely low overpotential at 100 mA/cm2 (η100) of 124 mV was observed. This corresponds to η10 of ~59 mV. The Tafel plot yields a slope b = 68 mV/dec and an exchange current density j0 = 3.3 mA/cm2. Both b and j0 are close to those of Pt, which currently is still the best HER electrocatalyst. The Rct of (NiFe)Sx/NiFe(OH)y was determined from the Nyquist plot of electrochemical impedance data to be 0.957 W, which is much lower than Fe0.96S/Fe(OH)3 (80.9 W) but comparable to Ni0.96S (0.705 W). This shows the necessity of using a bimetallic approach in material design. Finally, in a durability test conducted at a constant current bias of −120 mA/cm2, the (NiFe)Sx/NiFe(OH)y catalyst shows negligible degradation of catalytic activity over a 48 h period.

Multi-metallic a-TMS electrocatalysts without Ni have also been reported by He et al. [

60]. In this study, two related processes were used to synthesize amorphous N-doped cobalt-copper sulfide nanostructures on CF as bifunctional electrocatalysts. In the first process, anodic oxidation was used to grow Cu(OH)

2 nanowires on CF. ECD was then used to deposit Co(OH)

2 nanosheets on the Cu(OH)

2 nanowires from cobalt nitrate solution. Finally, the sample was sulfurized by immersion in thiourea to form the electrocatalyst designated as N-CoS/Cu

2S. By using a galvanostatic reaction with thiourea instead of immersion as the final step, a second electrocatalyst designated as N-(Co-Cu)S

x can be prepared. HRTEM and XRD characterization showed that both materials are amorphous. The main difference is that in N-CoS/Cu

2S, an amorphous heterostructure interface is present, whereas CoS

x and CuS

x are intermixed in N-(Co-Cu)S

x.

When N-CoS/Cu

2S was tested for HER activity in 1 M KOH by LSV, the measured η

10 and η

1 were 67 and 163 mV, respectively, and the Tafel slope was 88.7 mV/dec. Note that, although these electrocatalytic parameters are not as good as NiFeS

x/NiFe(OH)

y/NF, they are better than a-CoNiS

x/NF. The extracted C

dl and R

ct of N-CoS/Cu

2S are 288.3 mF/cm

2 and 3.35 W, respectively. In addition, a CA stability test conducted at −0.1 V versus RHE showed no change in current density for 36 h. The electrocatalytic parameters for N-(Co-Cu)S

x are listed in

Table 2. As shown in the HER electrocatalytic properties of N-(Co-Cu)S

x are not as good as N-CoS/Cu

2S. This is attributed to the higher intrinsic activity of the catalytic sites and the three-dimensional material structure of N-CoS/Cu

2S that is favorable to both charge and mass transfer. Note that both N-CoS/Cu

2S and N-(Co-Cu)S

x are bifunctional electrocatalysts.

A very recent development in multi-metallic a-TMS electrocatalysts is the use of amorphous–crystalline heterostructures in catalyst design. These combine the useful attributes of the amorphous and crystalline components and are usually in the form of a three-dimensional nanostructure. The properties of two of these hierarchical catalysts (CoWO

4/Ni

xFe

yS [

61] and Cu-CuS

2/NiCoS [

62]) are included in

Table 2.

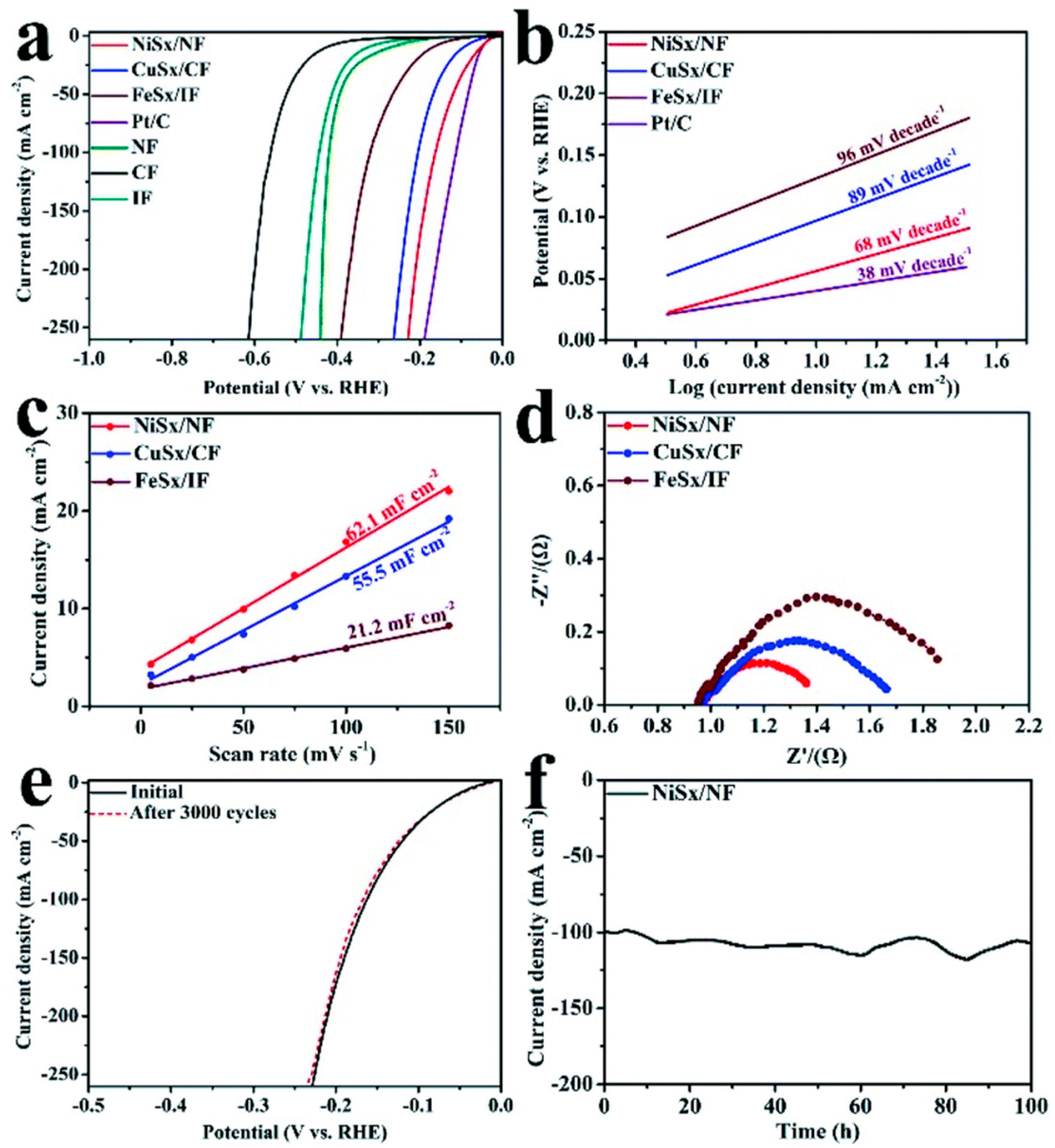

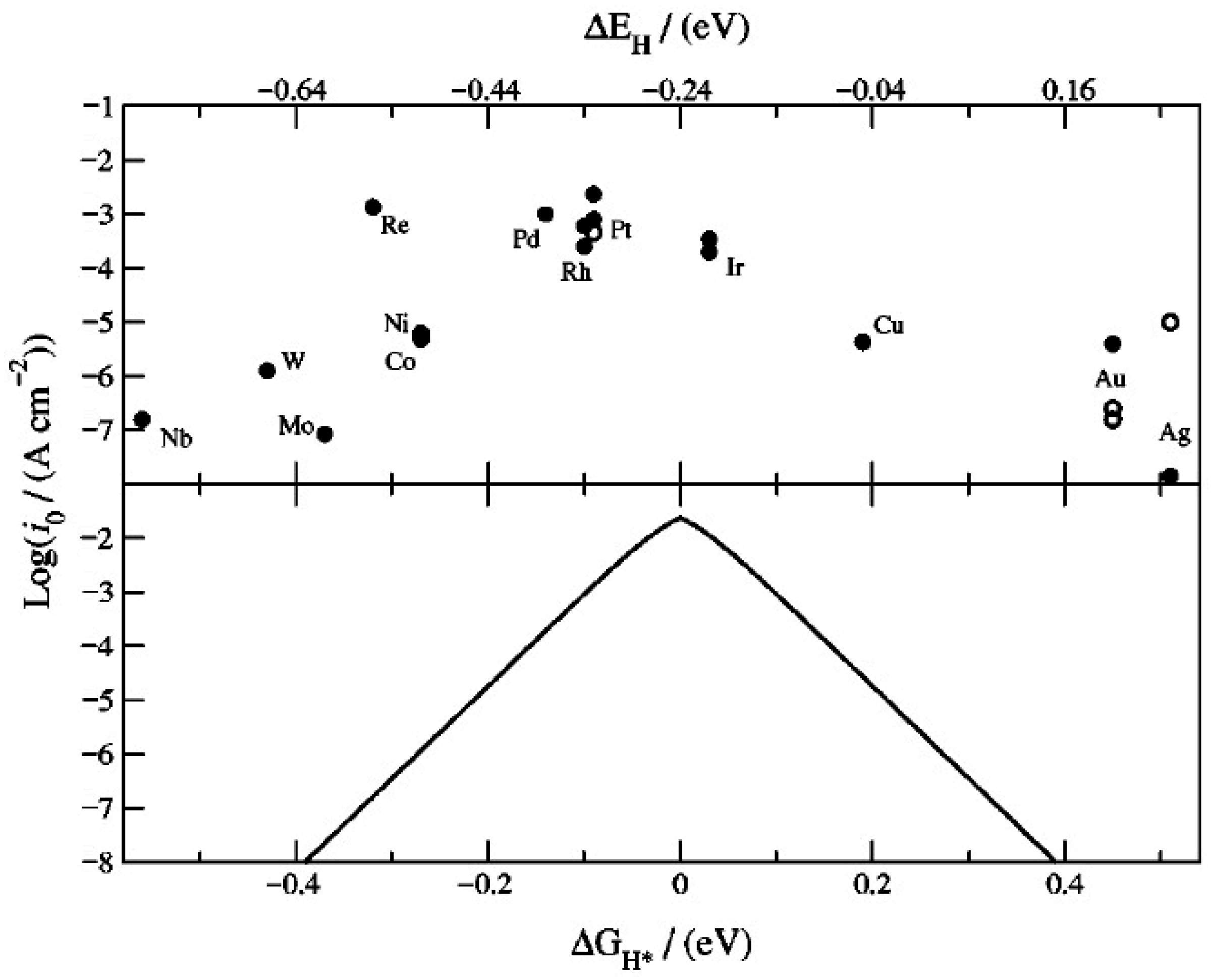

Table 1 and

Table 2 summarize the main properties of the amorphous first-row TMS HER electrocatalysts discussed thus far. It is evident that the majority of the electrocatalyst materials tabulated have only been tested in either strongly alkaline solution or neutral water (pH 7) conditions. The exceptions are electrodeposited a-NiS

x and a-CoS

x, which have also been tested in sulfuric acid. This can be due to chemical instability of amorphous TMS in acidic electrolytes leading to deactivation of the catalyst as mentioned in ref. [

46]. Amongst the mono-metallic amorphous TMS, the most promising HER electrocatalyst is a-NiS

x deposited by the CBD method. This synthesis route results in a-NiS

x with the lowest η

10, the highest exchange current density j

0, a low Tafel slope and 100 hrs of durability at 100 mA/cm

2. It is also bifunctional and an alkaline EWS cell with a-NiS

x/NF as cathode and anode can generate H

2 at a current density of 10 mA/cm

2 at 1.5 V [

42]. The electrochemical properties of a-NiS

x appear strongly dependent on the deposition method. When a-NiS

x is deposited by the electrodeposition method, the h

10 becomes much larger and the Tafel slope also increases. Also notable is electrodeposited a-CoS

x, which is a bifunctional electrocatalyst material. The dependence of HER electrocatalytic properties on the chemical composition of the TMS can be explained in terms of the hydrogen chemisorption energy per atom DE

H on different metallic sites or the volcano plot [

63]. This is illustrated by

Figure 6 (top) reprinted from the article by NØskov et al. [

64]. The volcano plot is a semi-logarithmic plot of the exchange current density j

0 versus the DE

H for different metallic catalyst surfaces. The DE

H of each metal in

Figure 6 is calculated using density functional theory for a 2 × 2 surface unit cell, and crystallinity is therefore assumed. The j

0 value for each metal is taken from other publications in the literature. The lower plot of

Figure 6 is the volcano plot based on NØrskov’s kinetic model. Here, the logarithm of j

0 is plotted against the free energy of adsorbed hydrogen DG

H* = DE

H + 0.24 eV [

64]. As shown by these two plots, the best HER electrocatalyst materials, namely Pt, rhodium (Rh) and palladium (Pd), are nearly thermo-neutral with near zero DG

H*. Hydrogen can adsorb and desorb easily from these precious metals. Alternative suitable earth-abundant metals are Ni and Co with DG

H* = −0.28 eV and Cu with DG

H* = 0.2 eV. This is consistent with the electrocatalytic properties shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2 for amorphous TMS materials.

Amongst the multi-metallic amorphous TMS, the most promising electrocatalyst for HER is the bifunctional NiFeS

x/NiFe(OH)

y. The η

10 and Tafel slope of this composite are comparable to a-NiS

x but j

0 is higher, suggesting higher intrinsic activity at catalytic sites. The low value of the h

100 shows that this composite bifunctional electrocatalyst has potential for industrial applications. An electrolyzer based on NiFeS

x/NiFe(OH)

y || NiFeS

x/NiFe(OH)

y electrodes in 1 M KOH has a low onset voltage of 1.39 V at 10 mA/cm

2 at 40 °C [

59].

Further insight can be gained by comparing the amorphous TMS electrocatalyst parameters in

Table 1 and

Table 2 with those of mono-metallic and multi-metallic crystalline TMS (c-TMS) electrocatalysts in

Table 3. The materials data in

Table 3 are taken from the recent literature [

65,

66,

67,

68]. The a-NiS

x deposited by the CBD method has lower h

10 and Tafel slope than crystalline NiS

2 formed on NiV LDH and polycrystalline NiS

2 film on polished glassy carbon (GC) [

65]. However, for a-NiS

x prepared by the electrodeposition and sol-ge/precursor routes, the h

10 is higher than crystalline NiS

2 [

66]. This shows that the electrocatalytic performance of amorphous TMS is not necessarily better than crystalline TMS and is strongly dependent on the deposition method. Similar observations can be made when a-CoS

x and a-FeS

x are compared with their crystalline counterparts [

67,

68].

A comparison should also be made with the more widely studied amorphous second-row TMS electrocatalyst a-MoS

x and the benchmark Pt/C. For the former, according to the initial 2011 publication [

69], amorphous MoS

3 deposited by cyclic voltammetry on rotating glassy carbon in 1 M H

2SO

4 has a η = 200 mV at the current density 14 mA/cm

2. This is comparable to the η

10 of electrodeposited a-NiS

x on FTO and higher than CBD a-NiS

x/NF (

Table 1). As for Pt/C, the η

10 and Tafel slope has been reported as 44 mV and 38 mV/dec, respectively, in 1 M KOH [

42]. These are about 83% of the η

10 and 56% of the Tafel slope for a-NiS

x prepared by the CBD method, demonstrating that promising progress has been made.

5. Amorphous Third-Row TMS HER Electrocatalysts

For the third row of the transition metal series (atomic number 71–80) in the Periodic Table, only tungsten (W) thus far is known to form amorphous sulfides with electrocatalytic properties for the HER. In 2015, Xiao et al. used ECD to deposit amorphous tungsten sulfide (a-WS

x) onto nanoporous gold (NPG) to form a composite a-WS

x/NPG electrode and demonstrated good catalytic performance [

49]. The NPG with larger effective surface area than a conventional electrode was prepared by selective wet etching of silver (Ag) from an Au/Ag leaf alloy. After this dealloying, the NPG film was transferred to a polished glassy carbon electrode and a-WS

x was electrodeposited using an electrochemical cell containing an aqueous electrolyte with 0.1 M KCl and 5 mM of ammonium tetrathiotungstate ((NH

4)

2WS

4). The non-crystalline nature of the deposited film was confirmed by XRD, and the presence of W and S was determined by energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. When tested for HER activity by LSV in 0.5 M H

2SO

4, the optimized a-WS

x/NPG bilayer electrode showed an onset overpotential of 108 mV and a η

10 of ~150 mV. The extracted Tafel slope b and j

0 are 74 mV/dec and 1.2 mA/cm

2, respectively. It is significant that the Tafel slope for a-WS

x/NPG is much lower than that for a-WS

x (127 mV/dec) and glassy carbon (135 mV/dec). This study highlighted the fact that the porosity of the support layer is crucial to the performance of a-WS

x electrocatalysts. The stability of a-WS

x/NPG in acidic electrolyte was studied by LSV cycling. No change in the polarization curve was observed after 500 cycles.

a-WS

x has also been prepared by Yang et al. using a simple thermolysis technique [

50]. This technique was previously used for the deposition of crystalline WS

2 [

70]. The thermolysis process involves first dissolving (NH

4)

2WS

4 in hydrochloric acid to form a stock solution. Droplets of this aqueous solution were deposited onto either FTO or glassy carbon substrates. The wetted substrate was transferred into the quartz tube of a chemical vapor deposition (CVD) furnace and thermal annealing was performed at 210 °C for 30 min in flowing nitrogen gas. During this annealing period, (NH

4)

2WS

4 decomposes into a-WS

x. For the preparation of a-WS

x, it is crucial to choose an annealing temperature between 150 and 310 °C because at higher temperatures, crystalline 2H-WS

2 polytype will form instead [

53].

Although mono-metallic a-WS

x can be easily prepared by thermolysis, it is not suitable for HER electrocatalysis. This is because, as shown by SEM, the as-synthesized a-WS

x has a branched texture with a characteristic length scale of micrometers. Furthermore, when tested in a 3-electrode cell with a Pt mesh counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, the polarization curve for a-WS

x in 0.5 M H

2SO

4 solution showed an onset potential of approximately 300 mV vs. RHE, and the η

10 is 604 mV vs. RHE (

Table 1) [

50]. These overpotentials, which are significantly higher than the corresponding values for amorphous first-row TMS HER electrocatalysts, can be explained by the higher chemisorption energy of hydrogen on W, as shown by the volcano curve (

Figure 6).

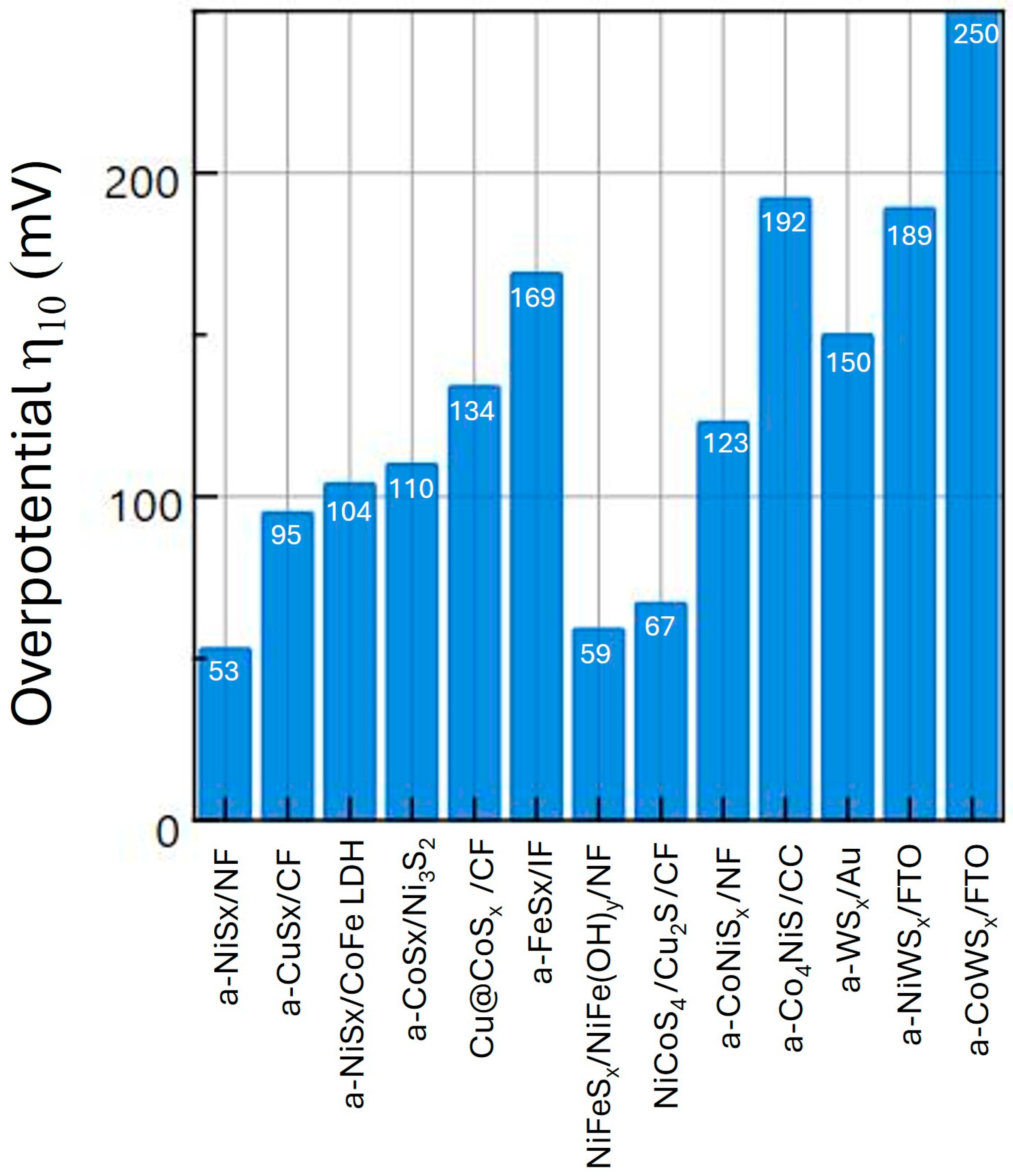

The electrocatalytic properties of a-WS

x can be significantly enhanced by incorporating optimized concentrations of Co

2+ or Ni

2+ ions into a-WS

x. When cobalt (II) chloride hexahydrate (CoCl

2·6H

2O) is added to an aqueous solution of (NH

4)

2WS

4 at a Co:W atomic ratio of 1:3, the a-CoWS

x film obtained by thermolysis at 210 °C has a lower overpotential at 10 mA/cm

2 of 330 mV (

Table 2). This overpotential can be further reduced to 250 mV by using cobalt (II) acetate as a cobalt source in a-CoWS

x [

50]. In the Tafel analysis of ohmic loss corrected current density–voltage data, Yang et al. showed that a-CoWS

x has an exchange current density j

0 of 3.2 mA/cm

2 and a Tafel slope b of 74 mV/dec. By contrast, a-WS

x has a j

0 value of only 0.86 mA/cm

2 and b is 129 mV/dec. This shows that a-CoWS

x has greater intrinsic catalytic activity and the HER kinetics are faster because of Co

2+ on the reaction mechanism.

When Ni

2+ is similarly incorporated into a-WS

x using nickel (II) chloride hexahydrate (NiCl

2·6H

2O) at an optimized Ni:W atomic concentration of 1:3, the a-NiWS

x film obtained by thermolysis at 210 °C showed a lower overpotential of 265 mV at 10 mA/cm

2. This can be further reduced to the minimum value of 189 mV at 10 mA/cm

2 when nickel (II) acetate is used instead as the Ni

2+ source [

50] (note that this overpotential of 189 mV is ~31% of the corresponding overpotential of a-WS

x). In the Tafel analysis, Yang et al. reported an extracted j

0 value of 3.5 mA/cm

2 and a Tafel slope of 55 mV/dec for a-NiWS

x (

Table 2). These parameters showed that a-NiWS

x has both higher intrinsic catalytic activity and faster HER kinetics because of the presence of Ni

2+ ions. This is consistent with TOF measurements for a-NiWS

x and a-CoWS

x. For a-NiWS

x and a-CoWS

x, the measured TOF at 300 mV overpotential are 0.34 and 0.12 s

−1, respectively. A durability test carried out by CA at 250 mV overpotential showed that the a-NiWS

x can maintain a constant current density for 24 hrs. Hence, a-NiWS

x is overall a more suitable HER electrocatalyst than a-CoWS

x. One further notable difference between a-WS

x and Ni- and Co-doped a-WS

x is that the doped films have a uniform nanoporous morphology which results in a large effective surface area.

Figure 7 shows a bar chart comparison of the published η

10 values for the W-based and first-row-based a-TMS HER catalysts listed in

Table 1 and

Table 2. It can be seen that the W-based catalysts have a generally higher h

10 than the catalysts based on first-row metals. This can be understood from

Figure 6, which shows that W has a higher chemisorption energy and free energy change in adsorption for hydrogen than Ni and Co.

_Xie.png)