Residual Ammonia Effects on NO Formation in Cracked Ammonia/Air Premixed Flames

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Methods

3. Results and Discussion

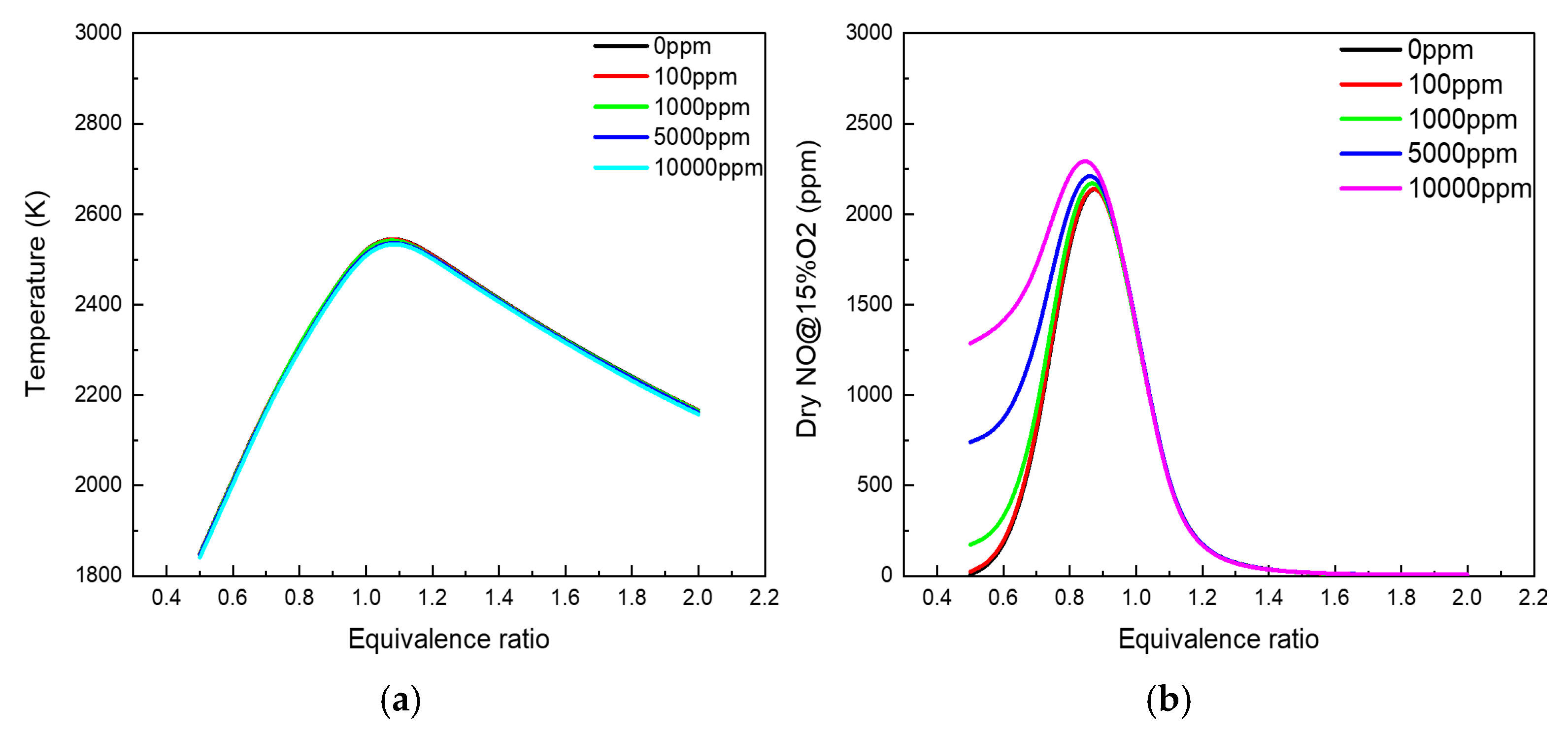

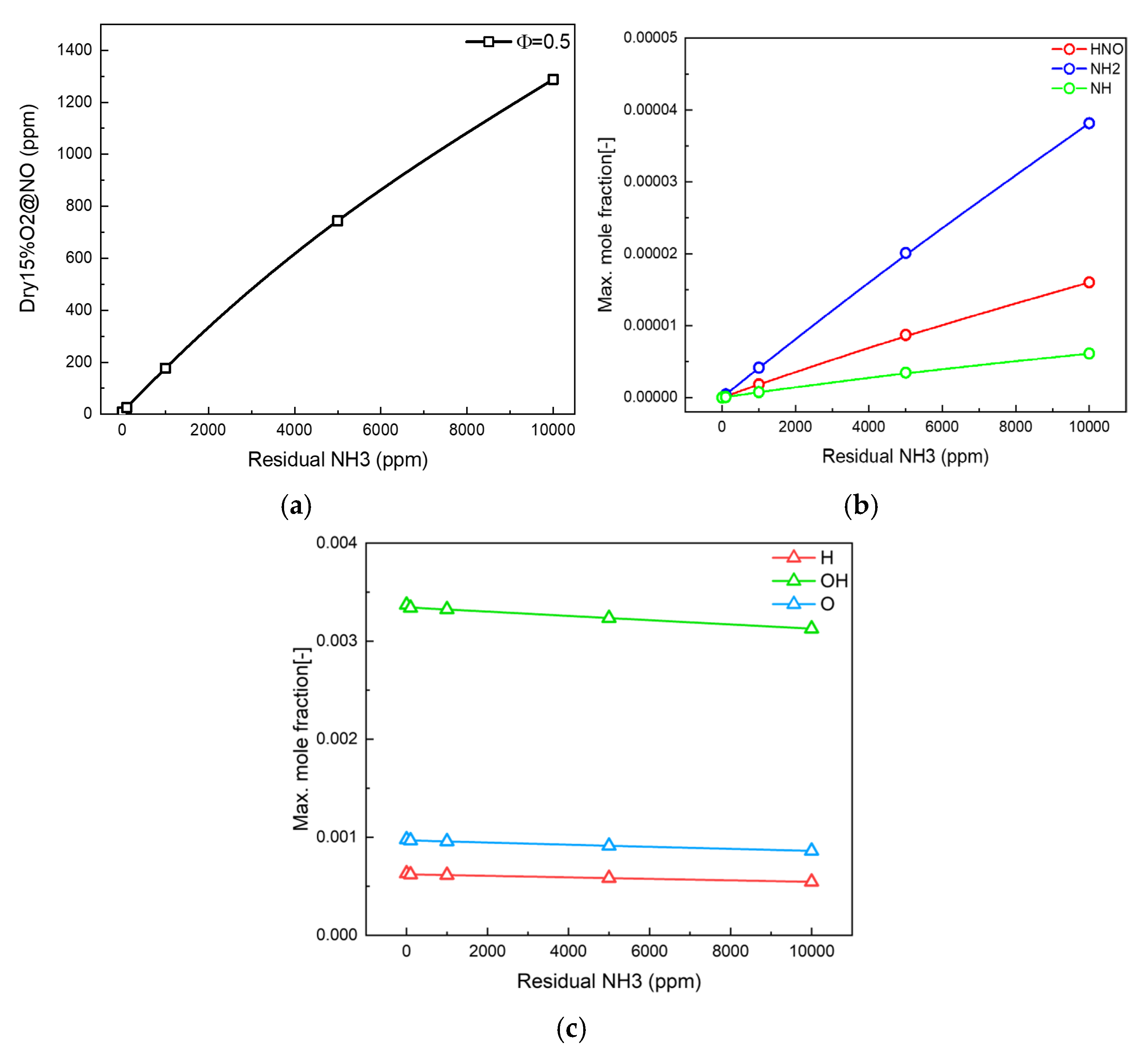

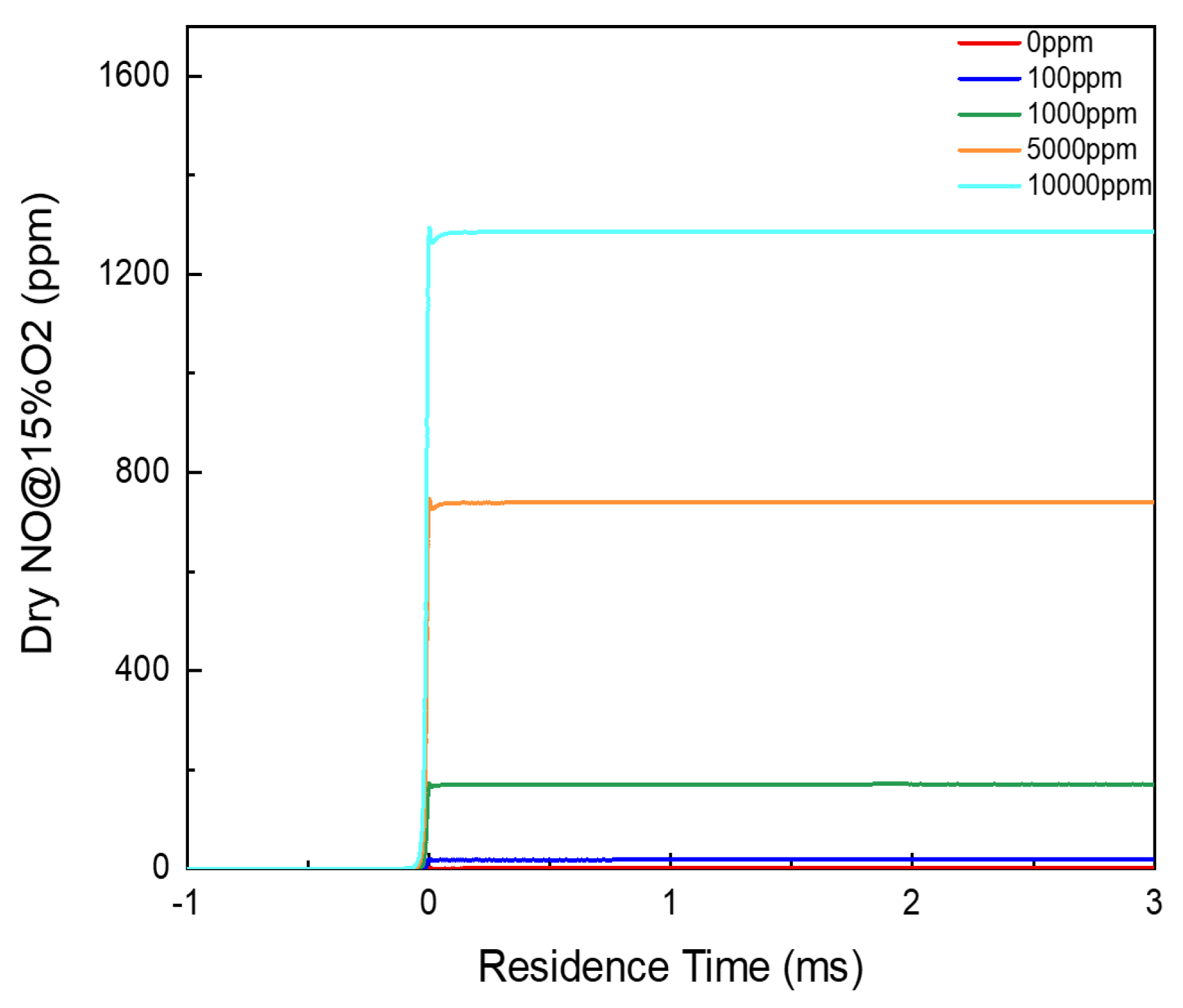

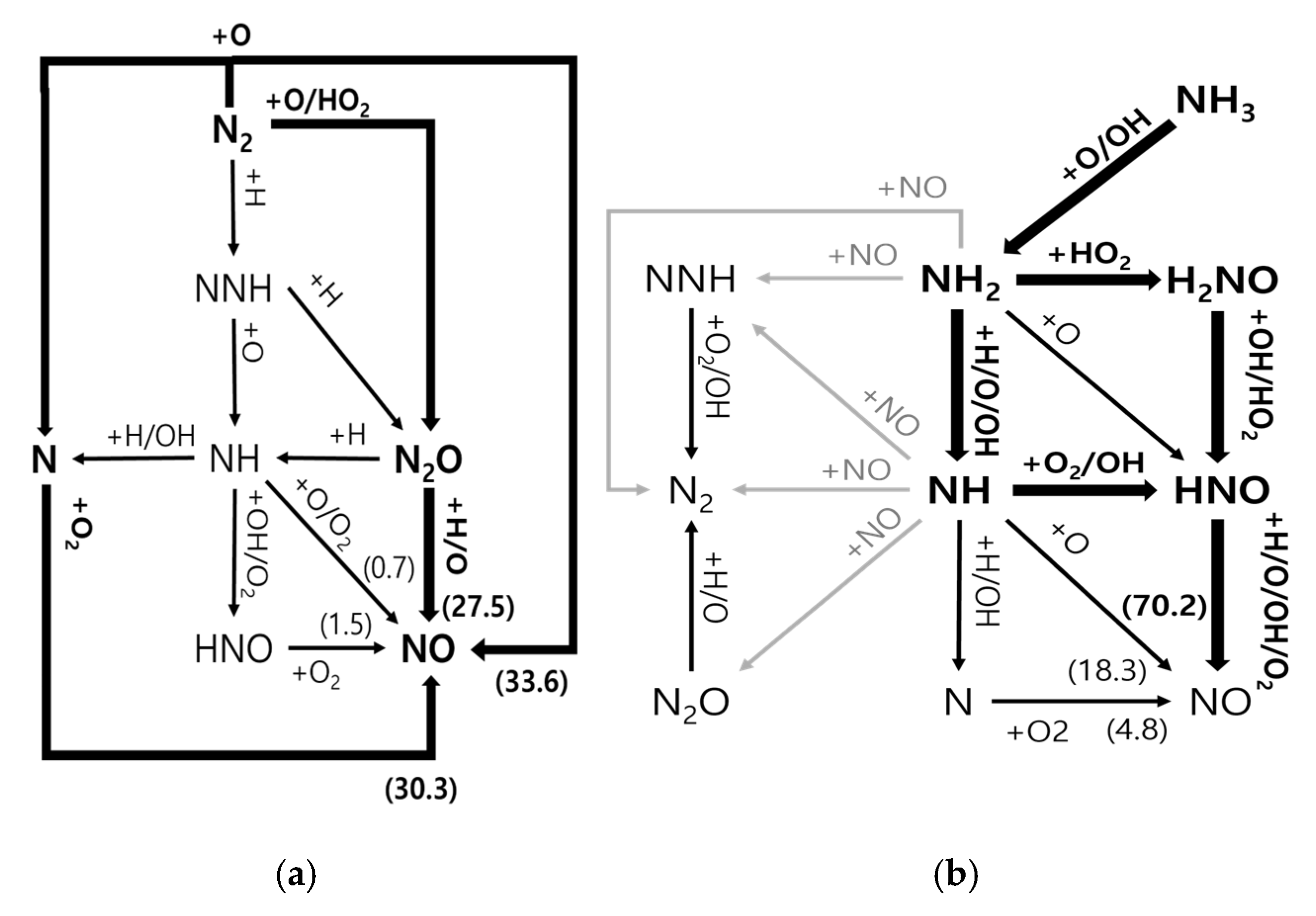

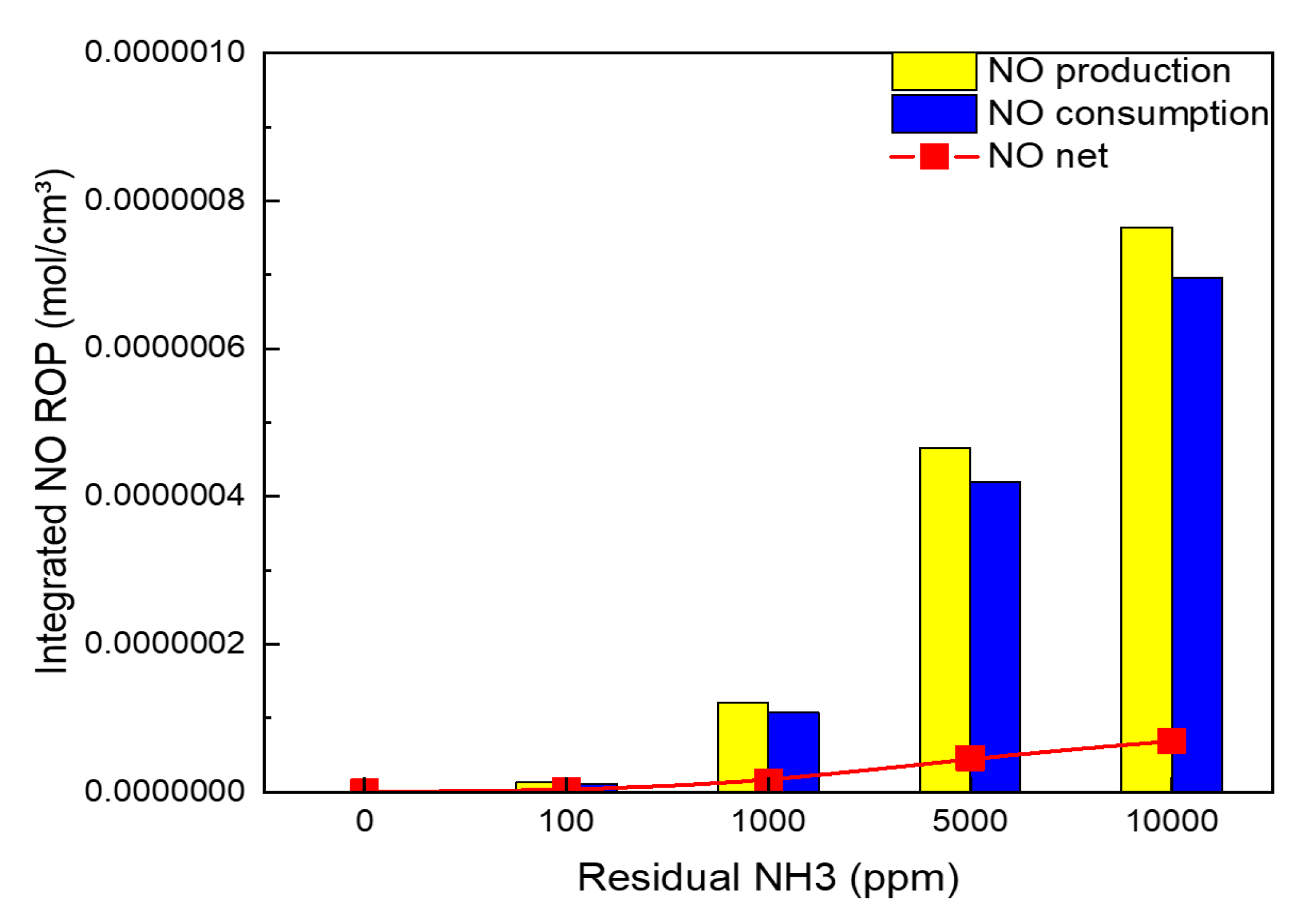

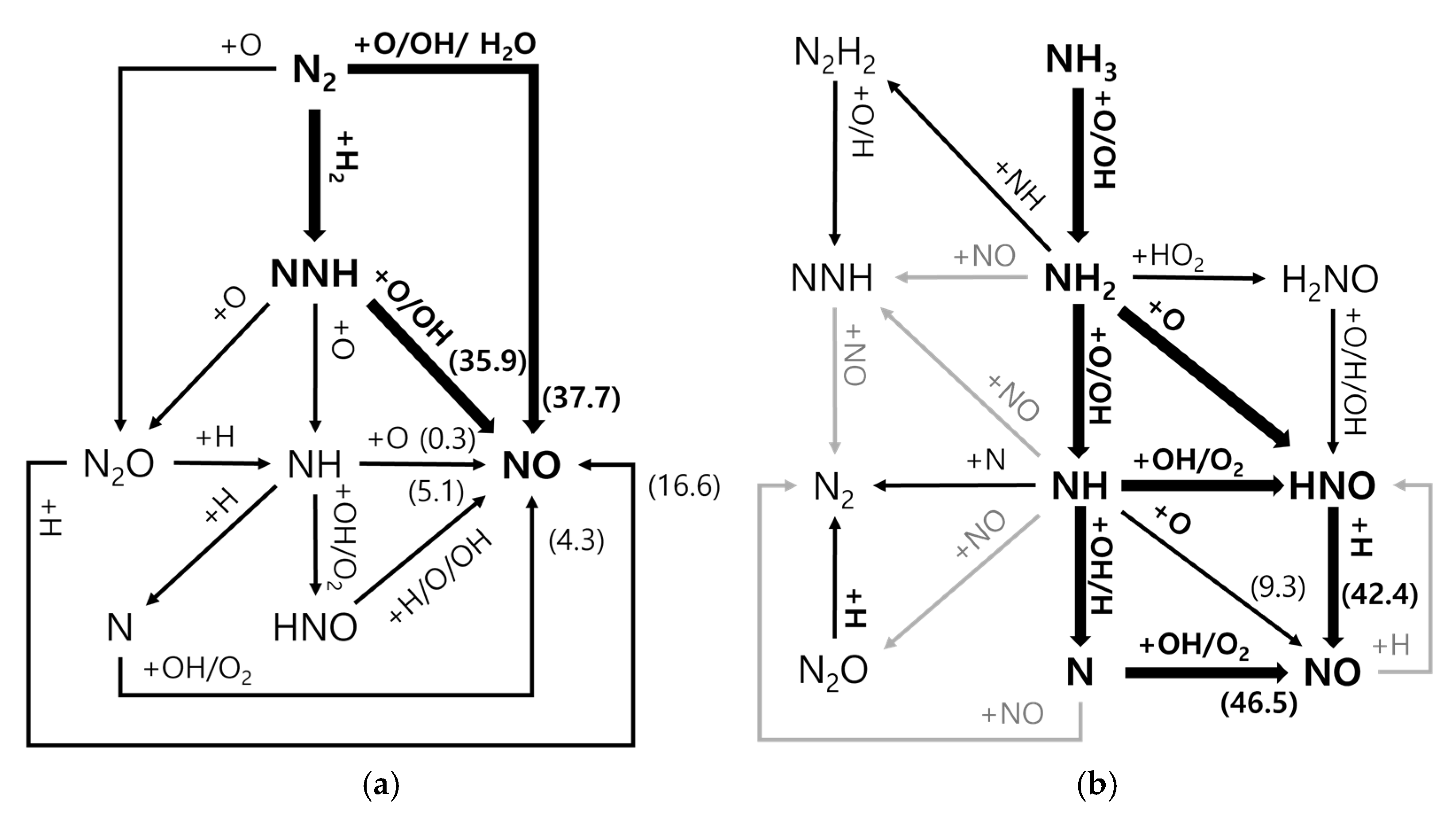

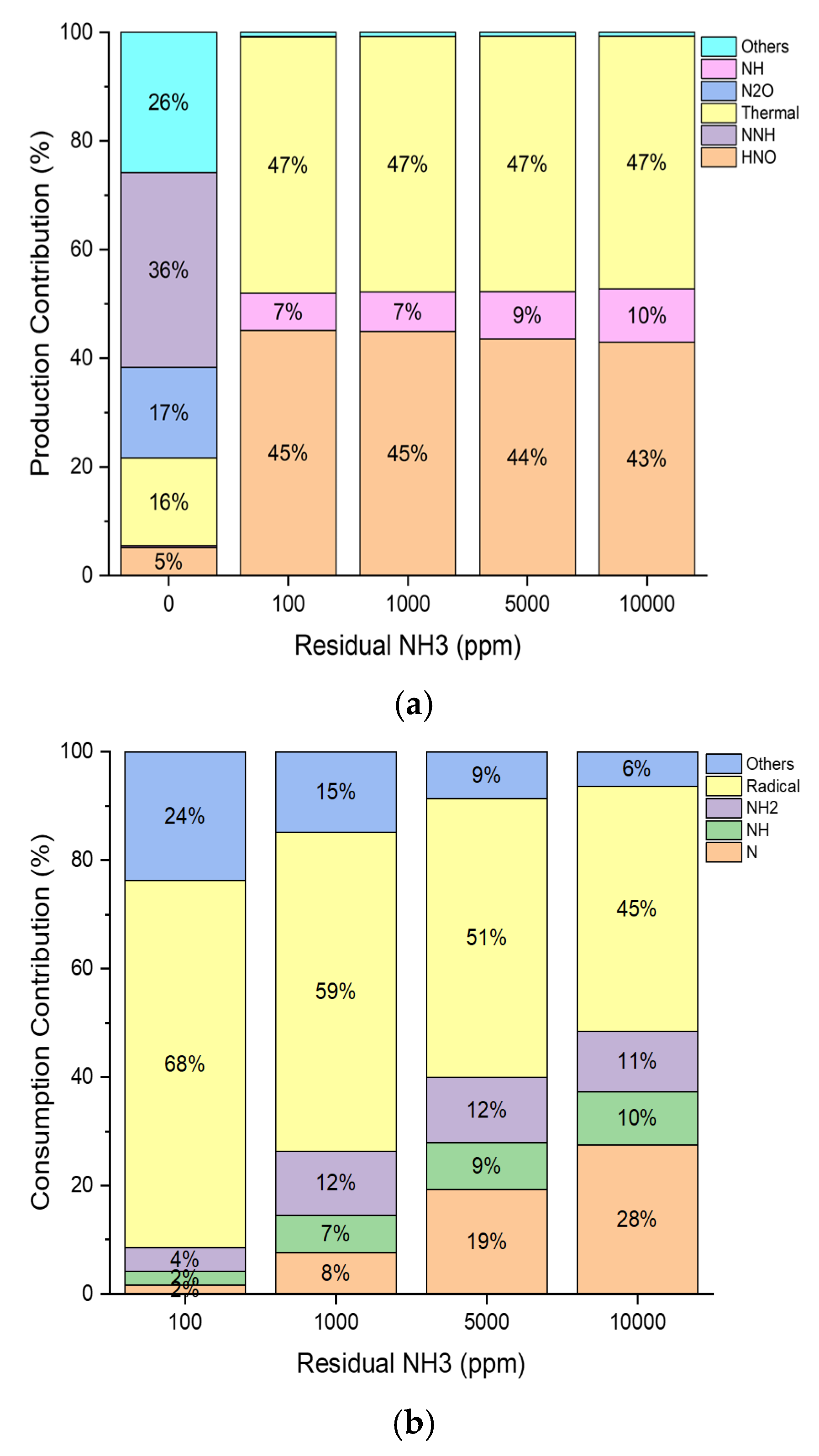

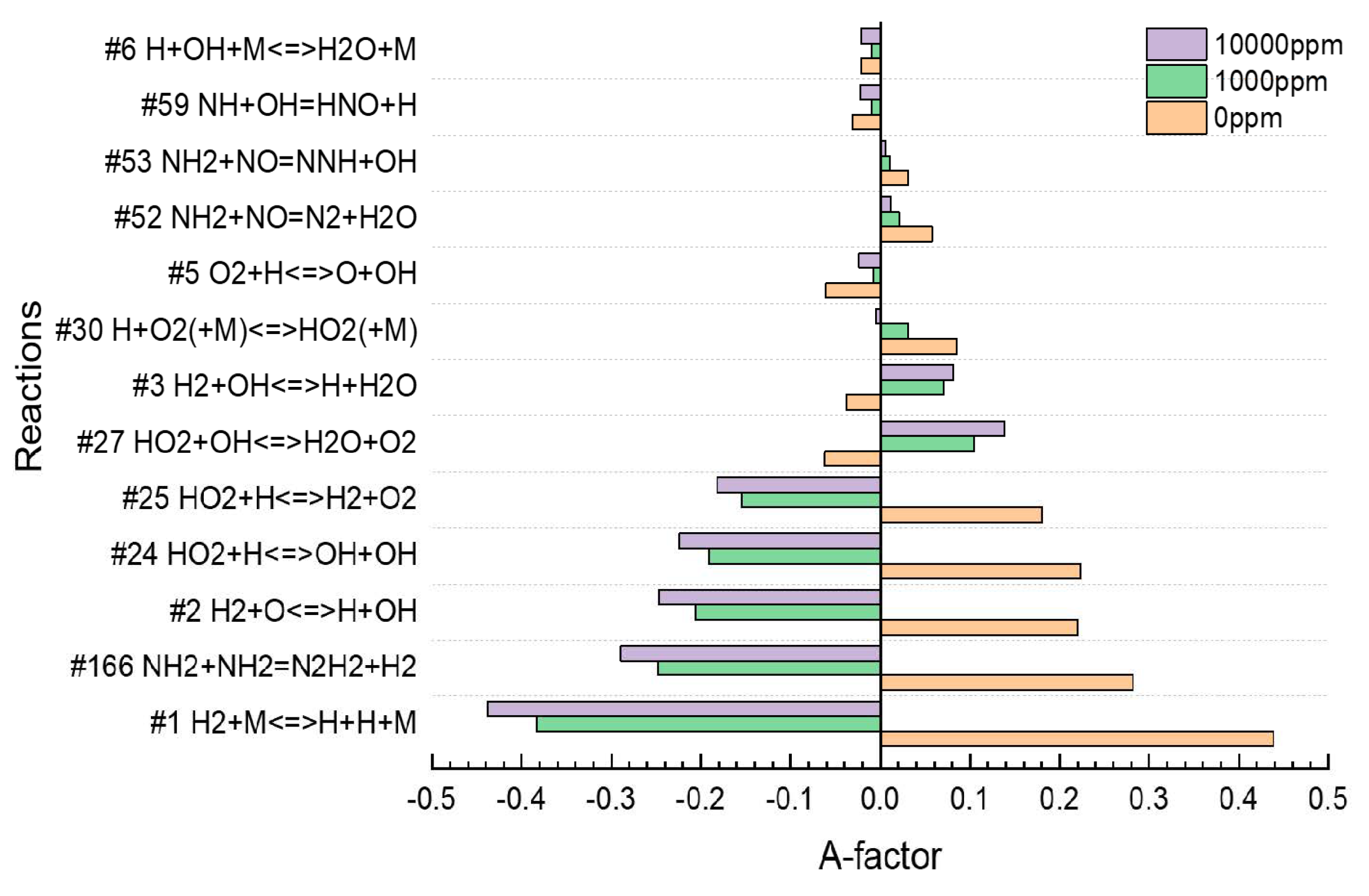

3.1. Residual Ammonia’s Effects on NO Formation in Lean Flames

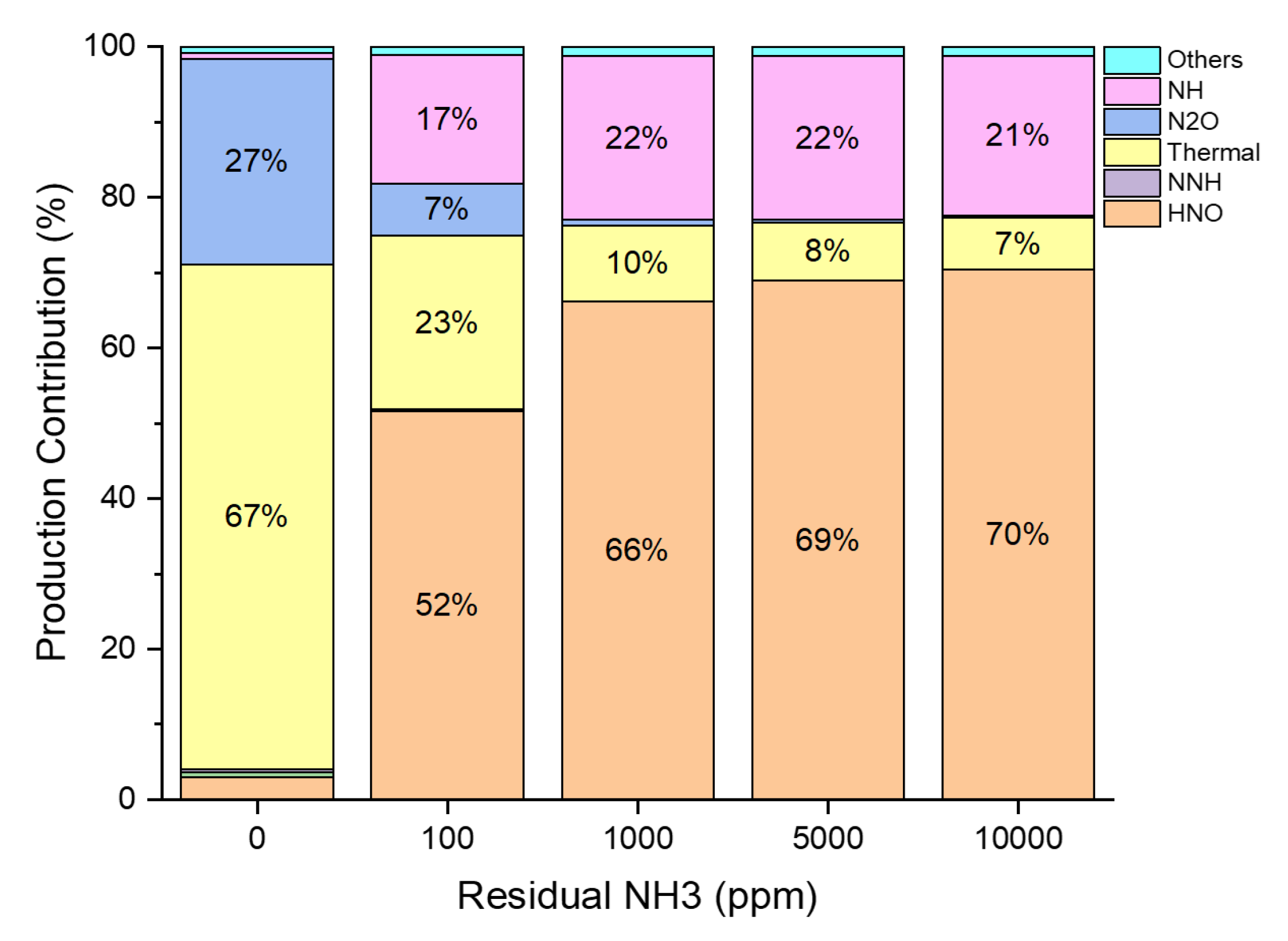

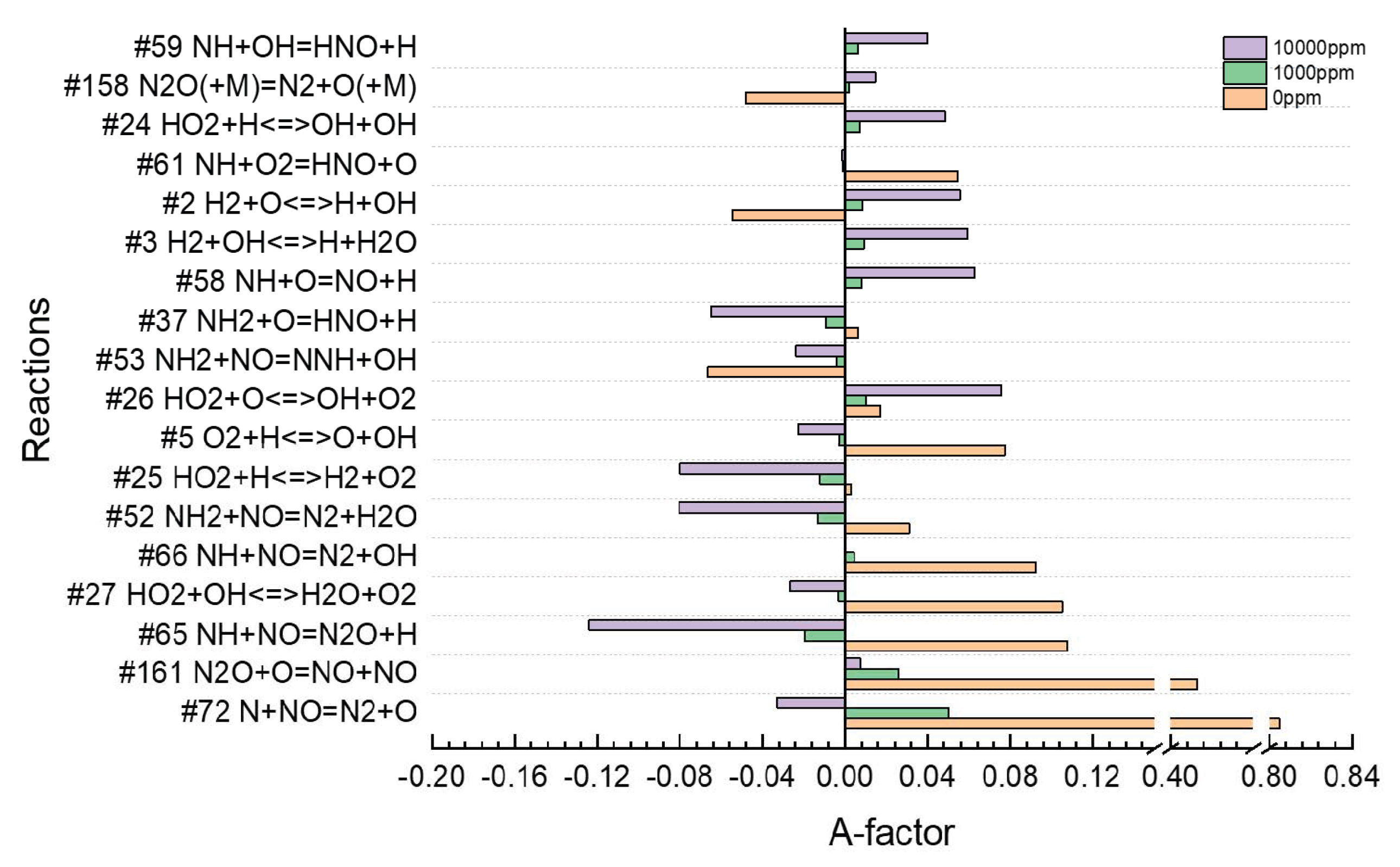

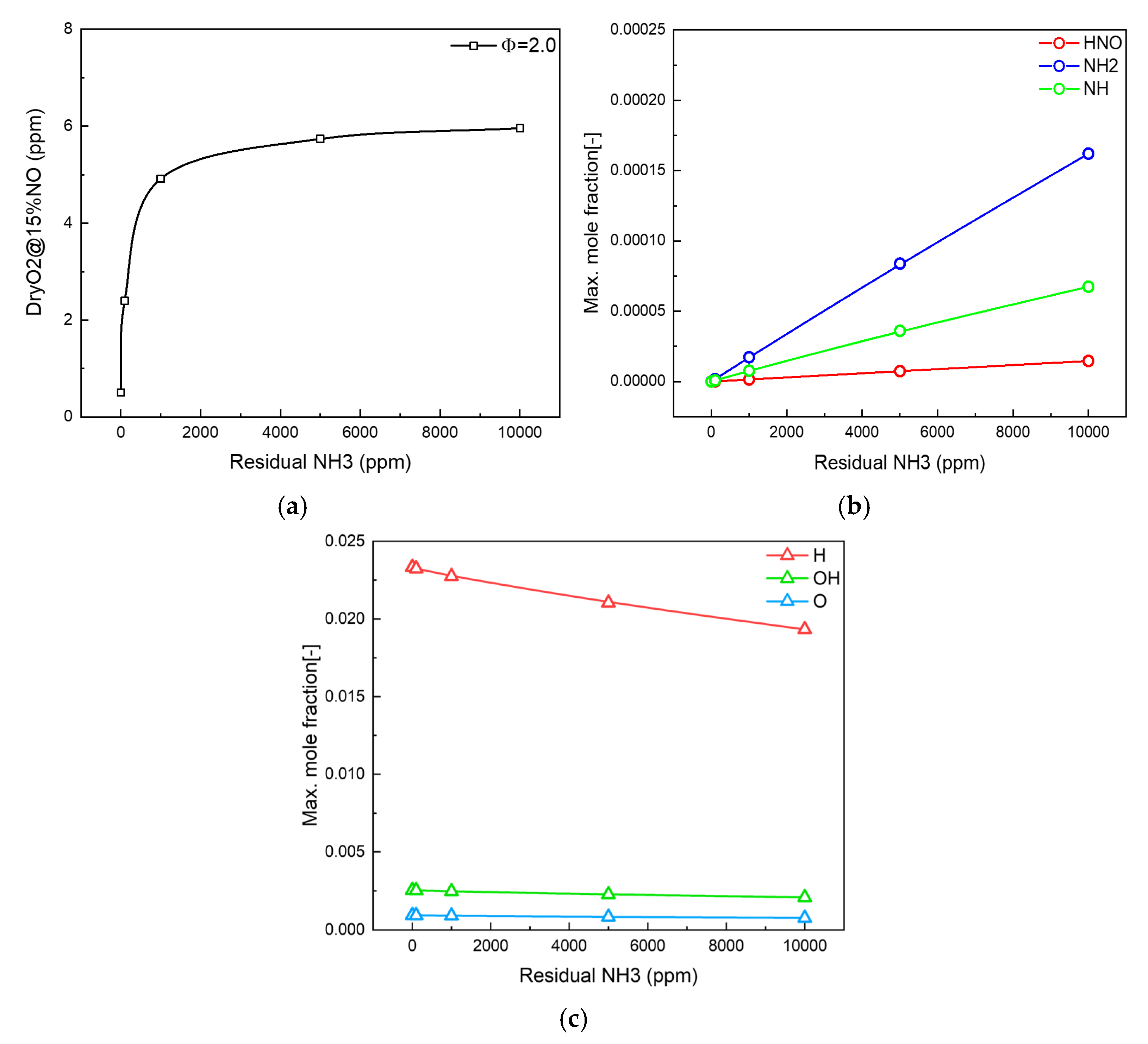

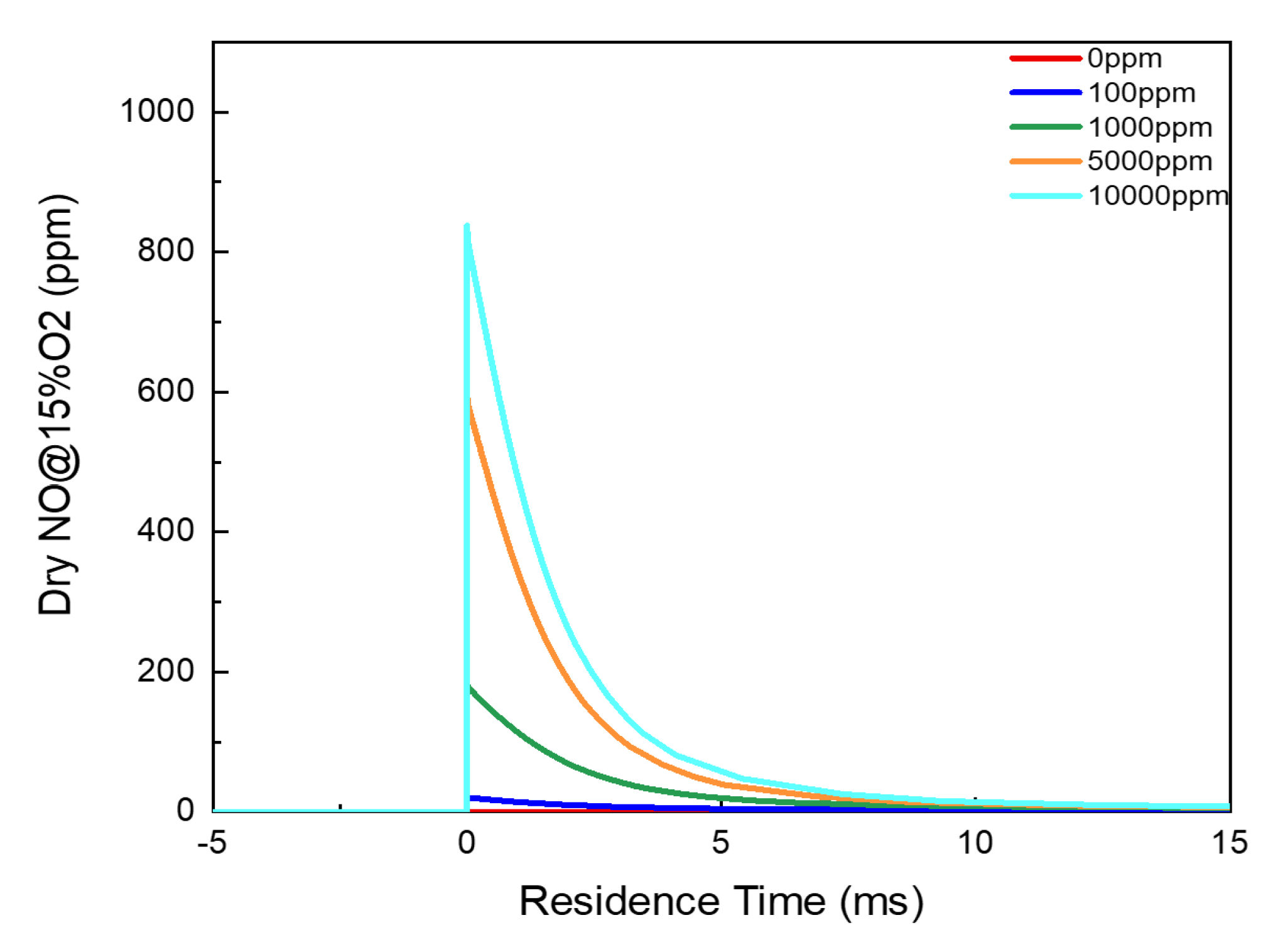

3.2. Residual Ammonia’s Effects on NO Formation in Rich Flames

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NOx | Nitrogen oxides |

| ROP | Rate of production |

| TCR | Thermochemical recuperation |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| CRN | Chemical reaction network |

| LES | Large eddy simulation |

| RQL | Rich–quench–lean |

| IDT | Ignition delay time |

| LBV | Laminar burning velocity |

| PSR | Perfectly stirred reactor |

References

- Salman, M.; Wang, G.; Qin, L.; He, X. G20 roadmap for carbon neutrality: The role of Paris agreement, artificial intelligence, and energy transition in changing geopolitical landscape. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 367, 122080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Yang, R.; Liu, J.; Xie, T.; Liu, J. Investigation of the mechanism behind the surge in nitrogen dioxide emissions in engines transitioning from pure diesel operation to methanol/diesel dual-fuel operation. Fuel Process Technol. 2024, 264, 108131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J. Applying separate treatment of fuel- and air-borne nitrogen to enhance understanding of in-cylinder nitrogen-based pollutants formation and evolution in ammonia-diesel dual fuel engines. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 69, 103910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. A Review of Ammonia Combustion Reaction Mechanism and Emission Reduction Strategies. Energies 2025, 18, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutak, W.; Jamrozik, A. Analysis of the Application of Ammonia as a Fuel for a Compression-Ignition Engine. Energies 2025, 18, 3217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömich-Jenewein, M.; Saidi, A.; Pivatello, A.; Mazzoni, S. Net-Zero Backup Solutions for Green Ammonia Hubs Based on Hydrogen Power Generation. Energies 2025, 18, 3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Paris Agreement; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Gonzalez-Mathiesen, C.; Aravena-Solís, N.; Rosales, C. Reconstruction as an Opportunity to Reduce Risk? Physical Changes Post-Wildfire in Chilean Case Studies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 9162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cheng, P.; Li, Z.; Fan, C.; Wen, J.; Yu, Y.; Jia, L. Efficient removal of gaseous elemental mercury by Fe-UiO-66@BC composite adsorbent: Performance evaluation and mechanistic elucidation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 372, 133463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, G.; Chaves, J.; Mendes, M.; Coelho, P. CFD-Assisted Design of an NH3/H2 Combustion Chamber Based on the Rich–Quench–Lean Concept. Energies 2025, 18, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.S.; Bao, Y.; Jin, P.; Tang, G.; Zhou, L. A review on ammonia, ammonia-hydrogen and ammonia-methane fuels. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 147, 111254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouacida, I.; Wachsmuth, J.; Eichhammer, W. Impacts of greenhouse gas neutrality strategies on gas infrastructure and costs: Implications from case studies based on French and German GHG-neutral scenarios. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 44, 100908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y. Hydrogen storage materials for hydrogen and energy carriers. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 18179–18192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.; Shabani, B.; Converti, A. Liquid Hydrogen: A Review on Liquefaction, Storage, Transportation, and Safety. Energies 2021, 14, 5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, A.K.; Kashyap, A.; Kumar, R. Hydrogen Fuel in Internal Combustion Engines: Advancements and Challenges. In Hydrogen as Emerging Fuel for De-Fossilizing Transport Sector; Valera, H., Agarwal, A.K., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 41–91. [Google Scholar]

- Alreshidi, M.A.; Yadav, K.K.; Shoba, G.; Gacem, A.; Padmanabhan, S.; Ganesan, S.; Guganathanh, L.; Bhuttoi, J.K.; Saravananj, P.; Fallatah, A.M.; et al. Hydrogen in transport: A review of opportunities, challenges, and sustainability concerns. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 23874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, Y.; Yamaguchi, M. Ammonia as a hydrogen energy carrier. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 22832–22839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasani; Prasidha, W.; Widyatama, A.; Aziz, M. Energy-saving and environmentally-benign integrated ammonia production system. Energy 2021, 235, 121400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obara, S. Energy and exergy flows of a hydrogen supply chain with truck transportation of ammonia or methyl cyclohexane. Energy 2019, 174, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbi, S.; Cole, R.; Emerson, B.; Noble, D.; Steele, R.; Sun, W.; Lieuwen, T. Evaluation of Minimum NOx Emission From Ammonia Combustion. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2024, 146, 031023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valera-Medina, A.; Xiao, H.; Owen-Jones, M.; David, W.I.F.; Bowen, P.J. Ammonia for power. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 69, 63–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Hayakawa, A.; Somarathne, K.D.K.A.; Okafor, E.C. Science and technology of ammonia combustion. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2019, 37, 109–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbaz, A.M.; Wang, S.; Guiberti, T.F.; Roberts, W.L. Review on the recent advances on ammonia combustion from the fundamentals to the applications. Fuel Commun. 2022, 10, 100053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, N.A.; Valera-Medina, A.; Alsaegh, A.S. Ammonia- hydrogen combustion in a swirl burner with reduction of NOx emissions. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 2305–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhao, N.; Chen, M.; Zheng, H. Numerically study of CH4/NH3 combustion characteristics in an industrial gas turbine combustor based on a reduced mechanism. Fuel 2022, 327, 124897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariemma, G.B.; Sorrentino, G.; Ragucci, R.; de Joannon, M.; Sabia, P. Ammonia/Methane combustion: Stability and NOx emissions. Combust. Flame 2022, 241, 112071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lee, M.; Park, J.; Park, J.; Lee, T. A Comparative Study of NOx Emission Characteristics in a Fuel Staging and Air Staging Combustor Fueled with Partially Cracked Ammonia. Energies 2022, 15, 9617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, B.; Zhang, J.; Shi, X.; Xi, Z.; Li, Y. Enhancement of ammonia combustion with partial fuel cracking strategy: Laminar flame propagation and kinetic modeling investigation of NH3/H2/N2/air mixtures up to 10 atm. Combust. Flame 2021, 231, 111472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bioche, K.; Bricteux, L.; Bertolino, A.; Parente, A.; Blondeau, J. Large Eddy Simulation of rich ammonia/hydrogen/air combustion in a gas turbine burner. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 39548–39562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Duan, F. Kinetic modeling and emission characteristics of multi-staged partially cracked ammonia/ammonia-fueled gas turbine combustors. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 122, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashchenko, D. Thermochemical waste-heat recuperation as on-board hydrogen production technology. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 28961–28968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Chitsaz, A.; Marivani, P.; Yari, M.; Mahmoudi, S.M.S. Effects of thermophysical and thermochemical recuperation on the performance of combined gas turbine and organic rankine cycle power generation system: Thermoeconomic comparison and multi-objective optimization. Energy 2020, 210, 118551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashchenko, D.; Mustafin, R.; Karpilov, I. Ammonia-fired chemically recuperated gas turbine: Thermodynamic analysis of cycle and recuperation system. Energy 2022, 252, 124081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucentini, I.; Garcia, X.; Vendrell, X.; Llorca, J. Review of the Decomposition of Ammonia to Generate Hydrogen. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 18560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzotta, L.; Meloni, R.; Lamioni, R.; Romano, C.; Galletti, C.; Borello, D. Numerical Investigation of NOx emissions in a gas turbine burner using hydrogen-ammonia and partially cracked ammonia fuel blends: A combined LES and CRN approach. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 278, 127330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Duan, F. Combustion and emission characteristics of industrial gas turbine combustor fueled with partially cracked ammonia: Effects of fuel–air staging and mixing. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 521, 146205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, M.J. Evaluation of NOx Emission Characteristics with Respect to Residual Ammonia Concentration in Ammonia Cracked Fuel. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashchenko, D. Ammonia-fueled solar combined cycle power system: Thermal and combustion efficiency enhancement via solar-driven ammonia decomposition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 142, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, D.; Park, S. Numerical investigation of the hydrogen addition effect on NO formation in ammonia/air premixed flames at elevated pressure using an improved reaction mechanism. Energy 2025, 327, 136393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glarborg, P.; Miller, J.A.; Ruscic, B.; Klippenstein, S.J. Modeling nitrogen chemistry in combustion. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2018, 67, 31–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.-W.; Li, Y.; Burke, U.; Banyon, C.; Somers, K.P.; Ding, S.; Khan, S.; Hargis, J.W.; Sikes, T.; Mathieu, O.; et al. An experimental and chemical kinetic modeling study of 1,3-butadiene combustion: Ignition delay time and laminar flame speed measurements. Combust. Flame 2018, 197, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS. CHEMKIN-PRO Release 2021 R1; ANSYS, Inc.: Canonsburg, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M.; Miller, M. Optically-accessible gas turbine combustor for high pressure diagnostics validation. In Proceedings of the 35th Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Reno, NV, USA, 6–10 January 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Arghode, V.K.; Gupta, A.K.; Bryden, K.M. High intensity colorless distributed combustion for ultra low emissions and enhanced performance. Appl. Energy 2012, 92, 822–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jin, T.; Luo, K.H. Response of heat release to equivalence ratio variations in high Karlovitz premixed H2/air flames at 20 atm. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 3195–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prade, B. Gas turbine operation and combustion performance issues. In Modern Gas Turbine Systems; Jansohn, P., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2013; pp. 383–423. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Wang, H.; Luo, K.; Fan, J. The Effects of Cracking Ratio on Ammonia/Air Non-Premixed Flames under High-Pressure Conditions Using Large Eddy Simulations. Energies 2023, 16, 6985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, X.; Meng, X.; Long, W.; Bi, M. A comprehensive kinetic modeling study on NH3/H2, NH3/CO and NH3/CH4 blended fuels. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 85, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skottene, M.; Rian, K.E. A study of NOx formation in hydrogen flames. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 3572–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Hydrogen addition effect on NO formation in methane/air lean-premixed flames at elevated pressure. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 25712–25725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Residual NH3 [ppm] | 0 | 100 | 1000 | 5000 | 10,000 | |

| Cracking Ratio [%] | 100.00 | 99.98 | 99.8 | 99.00 | 98.02 | |

| Fuel | XNH3 | 0 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.01 |

| XH2 | 0.75 | 0.749925 | 0.74925 | 0.74625 | 0.7425 | |

| XN2 | 0.25 | 0.249975 | 0.24975 | 0.24875 | 0.2475 | |

| Flame Temp. [K] | ϕ = 0.5 | 1850.0 | 1849.4 | 1848.5 | 1846.8 | 1840.7 |

| ϕ = 2.0 | 2164.8 | 2164.8 | 2164.2 | 2162.0 | 2158.0 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, D.; Kim, J.; Park, S. Residual Ammonia Effects on NO Formation in Cracked Ammonia/Air Premixed Flames. Energies 2025, 18, 6334. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236334

Kim D, Kim J, Park S. Residual Ammonia Effects on NO Formation in Cracked Ammonia/Air Premixed Flames. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6334. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236334

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Donghyun, Jiwon Kim, and Sungwoo Park. 2025. "Residual Ammonia Effects on NO Formation in Cracked Ammonia/Air Premixed Flames" Energies 18, no. 23: 6334. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236334

APA StyleKim, D., Kim, J., & Park, S. (2025). Residual Ammonia Effects on NO Formation in Cracked Ammonia/Air Premixed Flames. Energies, 18(23), 6334. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236334