Household Challenges in Solar Retrofitting to Optimize Energy Usage in Subtropical Climates

Abstract

1. Background

2. Scoping the Problem

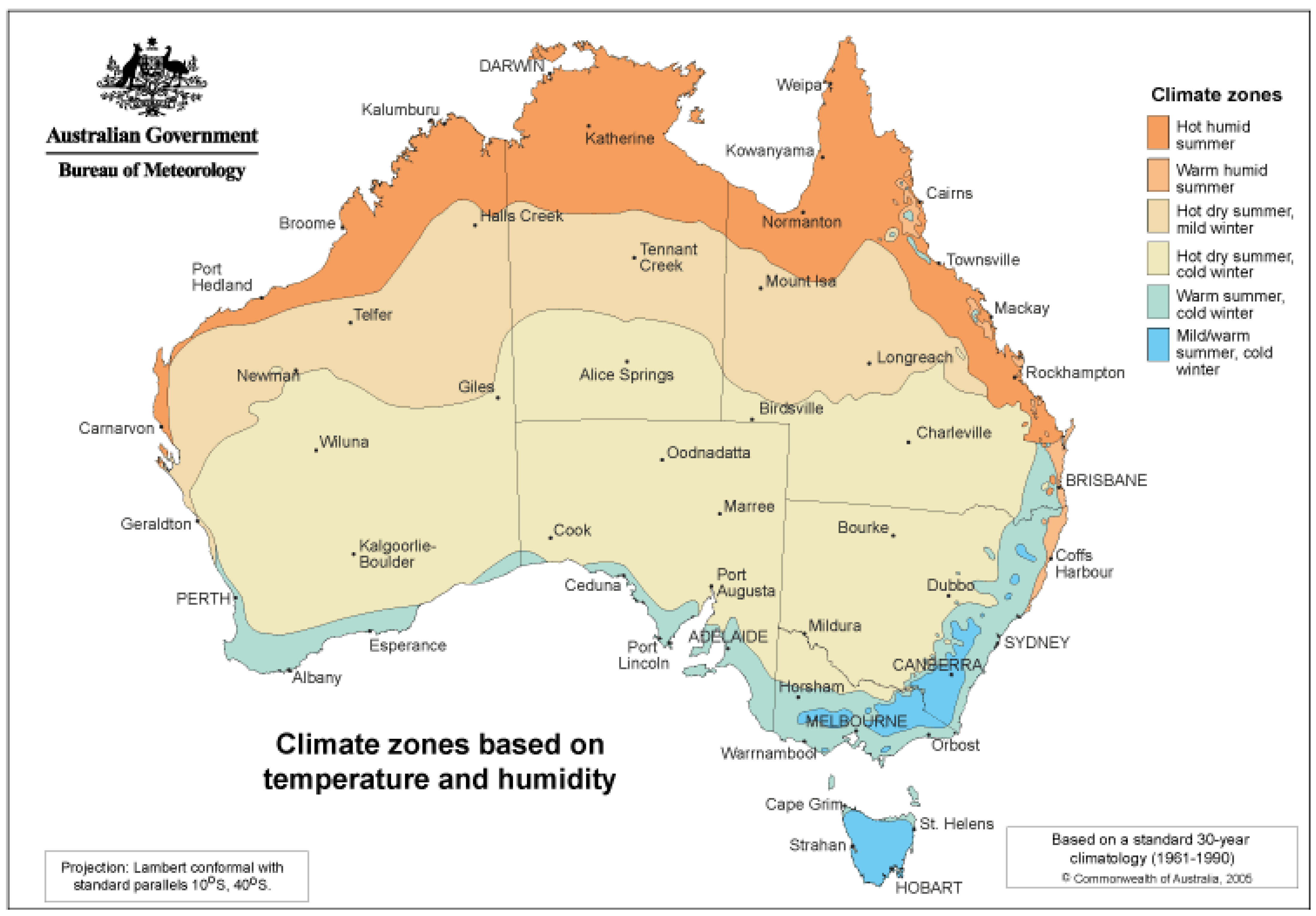

2.1. The Setting

2.2. Definitions

- Retrofitting Types: A light retrofit adapts specific building components without disrupting other areas. In contrast, a deep retrofit requires significant changes to building services and may involve large-scale interventions, such as changing occupancy.

- Solar Electric Systems: Also known as photovoltaic (PV) systems, these collect sunlight to generate electricity, typically comprising solar panels, an inverter to convert DC to AC, and sometimes, batteries for storage.

- Bill Savings: Solar generation and storage can significantly reduce energy bills. It is essential to assess these savings against the initial investment costs.

- Payback Period: The time required to recover the cost of an investment and reach a break-even point.

- Return on Investment (ROI): ROI measures the profitability of an investment, calculated as the percentage of net profit divided by the initial cost. It helps compare different investment opportunities, accounting for the holding period.

- Investment Gain (RI): This measures the percentage gain or loss on an investment, calculated by dividing the gain or loss by the original purchase price.

- Discounted Cash Flow: DCF evaluates an investment’s value based on expected future cash flows adjusted for the time value of money, emphasizing the importance of present value over future cash.

- Self-Sufficiency and Self-Consumption: Self-consumption is the percentage of energy used from the solar system, while self-sufficiency measures the percentage of energy consumed generated by the system. A 60% self-consumption target is recommended.

- Energy Efficiency and Emissions Abatement: Enhancements like efficient lighting, heat pumps, and improved building envelopes can significantly boost energy productivity and reduce emissions.

- Energy Sufficiency and Conservation: This concept focuses on maintaining sufficient energy service consumption while avoiding excess, promoting an equitable and environmentally friendly approach.

- Embedded and Embodied Carbon: Carbon intensity measures the CO2 emissions produced per kWh of electricity. Retaining existing materials during retrofitting reduces overall carbon intensity.

2.3. Customary Problems with Retrofitting

- High temperatures and thermal mass: Materials like concrete can help regulate temperature but can also lead to overheating during heatwaves.

- Building orientation and shading: Optimal orientation and shading are critical to passive cooling, but many existing buildings lack these features.

- Comfort difficulties: High humidity makes it hard to maintain comfortable indoor temperatures with passive cooling.

- Integration with existing structures: Retrofitting passive design features into current buildings can be complex.

- High temperatures and efficiency: Solar panels operate best under cooler conditions; high temperatures can reduce their energy output and return on investment.

- Weather impact: Severe weather, including intense winds and hail, can damage solar panels and mounts, necessitating stronger systems.

- Cost: The high initial investment for solar panel systems can deter some households from installing them.

- Solar electric and solar thermal end-use management: Households might struggle to align systems such as hot water provision with solar operation, reducing overall efficiency.

2.4. Energy Criteria in Retrofitting

2.4.1. Energy Efficiency

2.4.2. Energy Sufficiency

2.4.3. Self-Consumption and Self-Sufficiency

3. Method and Means

3.1. Research by Design

- Learning and Reflection: Architects study past projects to understand the thought processes behind them, analyzing what worked and what did not and learning from both successes and mistakes.

- Developing Best Practices: By systematically examining successful projects, architects can identify and document evidence-based approaches that offer valuable lessons for future endeavors.

- Benchmarking: Case studies enable architects to compare their own work against industry standards or exemplary projects, serving as a tool to refine their methods and elevate their own standards.

- Client Communication: These case studies serve as powerful tools to demonstrate the feasibility of specific design approaches, justify design decisions, and build client trust by showcasing successful past projects.

3.2. Sustainable Retrofitting

- Households are looking for ways to reduce consumption and change behaviour as the cost-of-living increases.

- Electricity suppliers are considering issues of cost and financial incentives.

- Interest in and uptake of new-energy technology has lately waned [16]. The Australian Government provides guides for the selection of solar systems for households wishing to explore the environmental and economic impacts on their family. They form another basis for this study’s methodology, especially the advice to engage in forward planning before purchasing and using electricity bills to estimate the amount of energy consumed annually by a typical household of similar size in the exact location (climate zone) [17].

3.3. National Energy Usage Benchmarks, System Selection Process, and Budget Guidelines

- Consumption information provided to the NERR by distributors.

- Localized zones, determined by jurisdictional ministers responsible for energy supply;

- Household size.

3.4. Solar Retrofitting System Brief

- What are the specific benefits of solar retrofitting for households (in subtropical climates)?

- How can households ensure that the right solar system for our needs and budget is selected?

- What key decision-making factors should households and consultants consider when planning for solar retrofitting?

- Bill savings: Of central interest will be the amount of grid power displaced by the solar energy generated and stored, its cost, and revenue from any available feed-in tariff (for supplying power to the grid) to offset initial capital expenditure. Recent research by the Federal Government reports that bill savings for 2023 to 2024 in Southeast Queensland amounted to 44% with solar and 96% with solar plus battery backup [22].

- Cost-effectiveness and Return on Investment (ROI): Consultants evaluate the financial returns on investments made in solar systems. The ideal payback period for these systems ranges from one to five years, while their lifespan can provide benefits for approximately 19 years, with an optimal lifespan around 25 years, as energy yields typically decrease over time [23]. Although the payback period indicates how many years it will take to recover the initial investment, it is a less effective criterion for financial decision-making compared to discounted cash flow analysis (DCA). Additionally, in situations with multiple contributing factors, such as economic subsidies and the high costs of advanced technologies like batteries, the decision-making environment can be somewhat opaque, requiring clear explanations [24]. In this study, cost-effectiveness plays a central role in the analyses conducted using ROI and DCA.

- Energy efficiency and emissions abatement: Advisors should add that households can achieve considerable energy productivity gains through more extensive adoption of mature technologies such as efficient lighting, heat pumps, improved building envelopes, and higher-efficiency appliances and equipment. Emissions are reduced in the process.

- Achieve a solar self-sufficiency rate of 90% and a self-consumption rate of 60% through batteries and electric vehicles.

- Design a solar system that matches existing and projected energy end use.

- Upfront cost can be saved if systems are bought as packages rather than purchased piece by piece.

- Monitor usage through a system such as an inverter.

- Use electricity bills to validate monitoring.

- Make effective use of electricity tariffs and times of use, i.e., avoiding peak use to reduce cost and reduce emissions.

- Site, system types, efficiency, and technological advancements.

- Cost of systems, payback periods, and life cycle energy.

- Climate, usage profiles, and energy demand.

- Energy sources and supply chain efficiency.

- Emissions related to carbon reduction [25].

- The largest possible generation system for a residential property;

- The most efficient array for the available roof space and local environmental conditions.

3.5. Establishing System Parameters and Practices

- Improve energy efficiency by using passive systems such as insulation and natural ventilation to reduce load on active systems.

- Shift electric use to daytime, e.g., mobile appliances should charge on solar power during the day.

- Switch off heating and cooling at night.

- Use appliances effectively and avoid standby mode.

- Transition from existing energy sources to all-electric systems.

- Reduce carbon emissions [27].

4. Feasibility Study Results

4.1. Identifying Candidate Energy Systems

4.1.1. Site Survey, End-Usage Pattern, and System Design

- Explore retaining the existing services to reduce costs.

- Replace the existing HWS with a solar thermal system, packaged with a solar electric system to save on installation costs.

- Make provision for future energy needs to be provided by a battery storage system.

4.1.2. System Comparison

- System 1: Grid-tied, generation only, an electric heat pump HWS.

- System 2: Grid-tied with solar generation and storage.

- System 3: Grid-tied, generation only, an electric heat pump HWS, battery-ready.

4.1.3. Observations and Limitations

- System packages have very different potential operational performance; unpacking supply performance is needed; self-consumption is a much smaller fraction of the whole than expected, with nearly two-thirds of the generated power being exported to the grid; higher-yield panels assist in optimizing the space on the roof, i.e., creating more power with fewer panels; battery power is limited, 21% of consumption. Unpacking supply performance is, therefore, needed. The operational performance of various system packages varies significantly; a clearer understanding of supply performance is necessary.

- Export to gid constitutes is a much larger fraction of total generation than initially anticipated, with nearly two-thirds of the generated power being exported to the grid, indicating that the households could improve economic performance. The feed-in tariff is reduced, hence economic gains are decreased, undermining economic performance.

- Utilizing higher-yield panels can optimize roof space, allowing for greater power generation from fewer panels.

- Battery storage is limited to 21% of total consumption, further emphasizing the need to analyse supply performance.

- The economic performance of the systems is increasingly intertwined with their operational performance, necessitating a forward-looking analysis. More robust economic analysis can provide a deeper understanding of the benefits.

- Understanding household behaviour regarding demand management is critical to accurately estimating potential operational performance.

- Historical data linking climate conditions to operational performance and associated emissions reductions indicate a potential decrease of 12.3 to 11.41 tons of CO2 annually. However, this approach has its limitations: it does not account for the impact of occupant demand management practices, and these practices must consider local microclimatic conditions along with both passive and active strategies [28].

- A recent EIA study on the life cycle assessment (LCA) of photovoltaic (PV) systems shows that emissions mainly occur during manufacturing. However, PV systems produce significantly lower carbon emissions compared with fossil fuels. Since 2015, environmental impacts have improved, particularly in payback times for non-renewable energy sources. Key updates include enhanced efficiency in Mono-Si PV panels, which minimize material waste and decrease demand for poly-Si, as well as higher efficiency in CdTe PV panels. Overall, the assessment indicates only minor deviations in environmental impacts across all evaluated technologies [29].

- Challenges for emissions abatement arise under extreme weather conditions. For example, specific days when external temperatures reach 37 degrees Celsius or higher lead to overheating and occupant discomfort, increasing energy demand and environmental impacts. Households can mitigate these effects if solar systems maintain comfort through careful demand management and the use of passive systems, which warrants additional exploration.

5. Detailed Study Results

5.1. Site System Upgrade and Technical Advancement

- How do the solutions revolve around the existing active and passive systems, the site, and the climate?

- How do the solutions achieve a balance between the demand for and supply of energy in the context of climate variability?

5.2. Solar Electric Systems

5.3. Solar Thermal Systems

5.4. Candidate System Features and Performance

5.4.1. System Features

5.4.2. System Usage

5.4.3. Energy Outcomes and System Performance

5.5. Economic Performance, Cost Effectiveness, and Discounted Cash Flow

5.5.1. Economic Performance and Cost Effectiveness

5.5.2. Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) and Net Present Value (NPV)

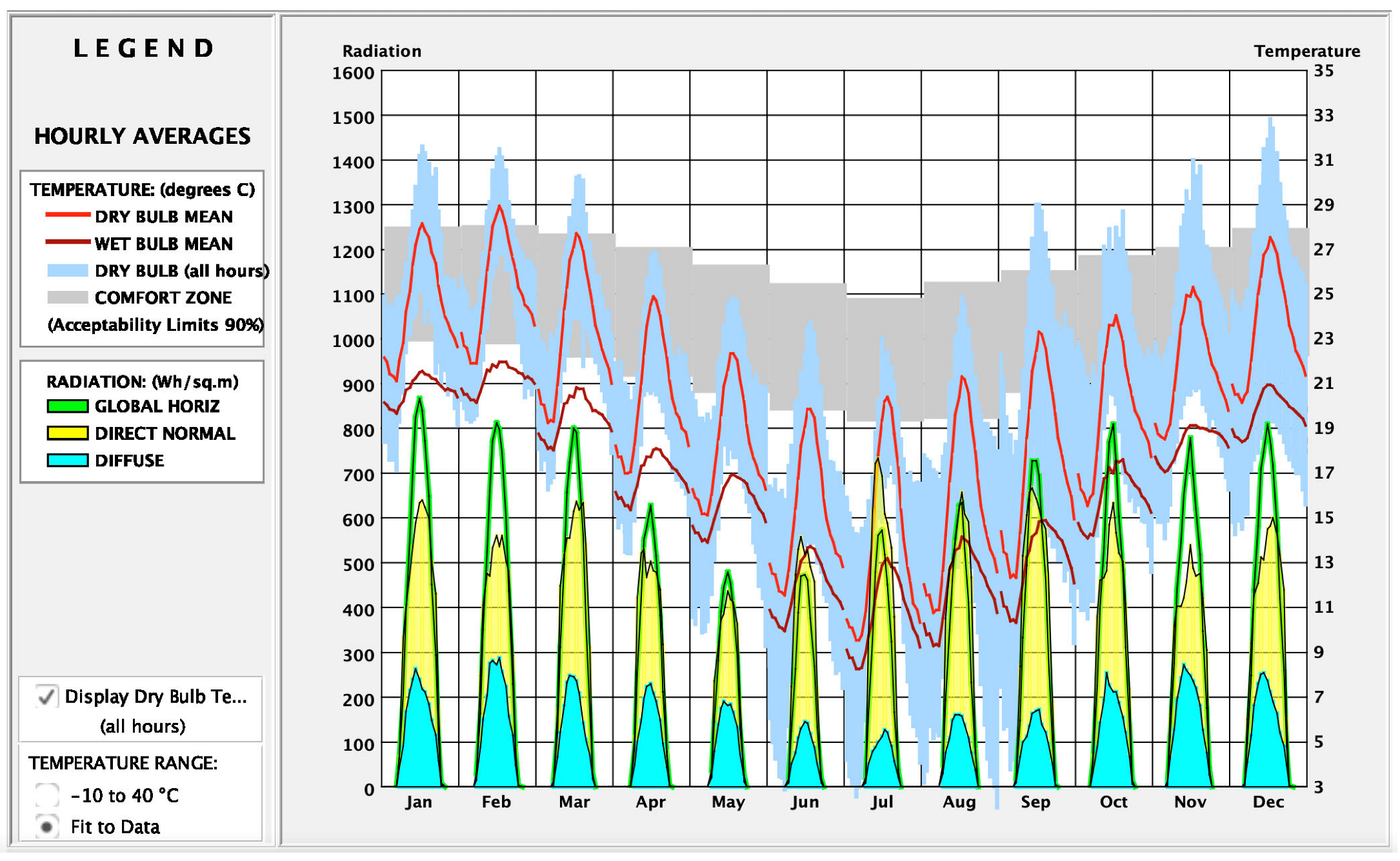

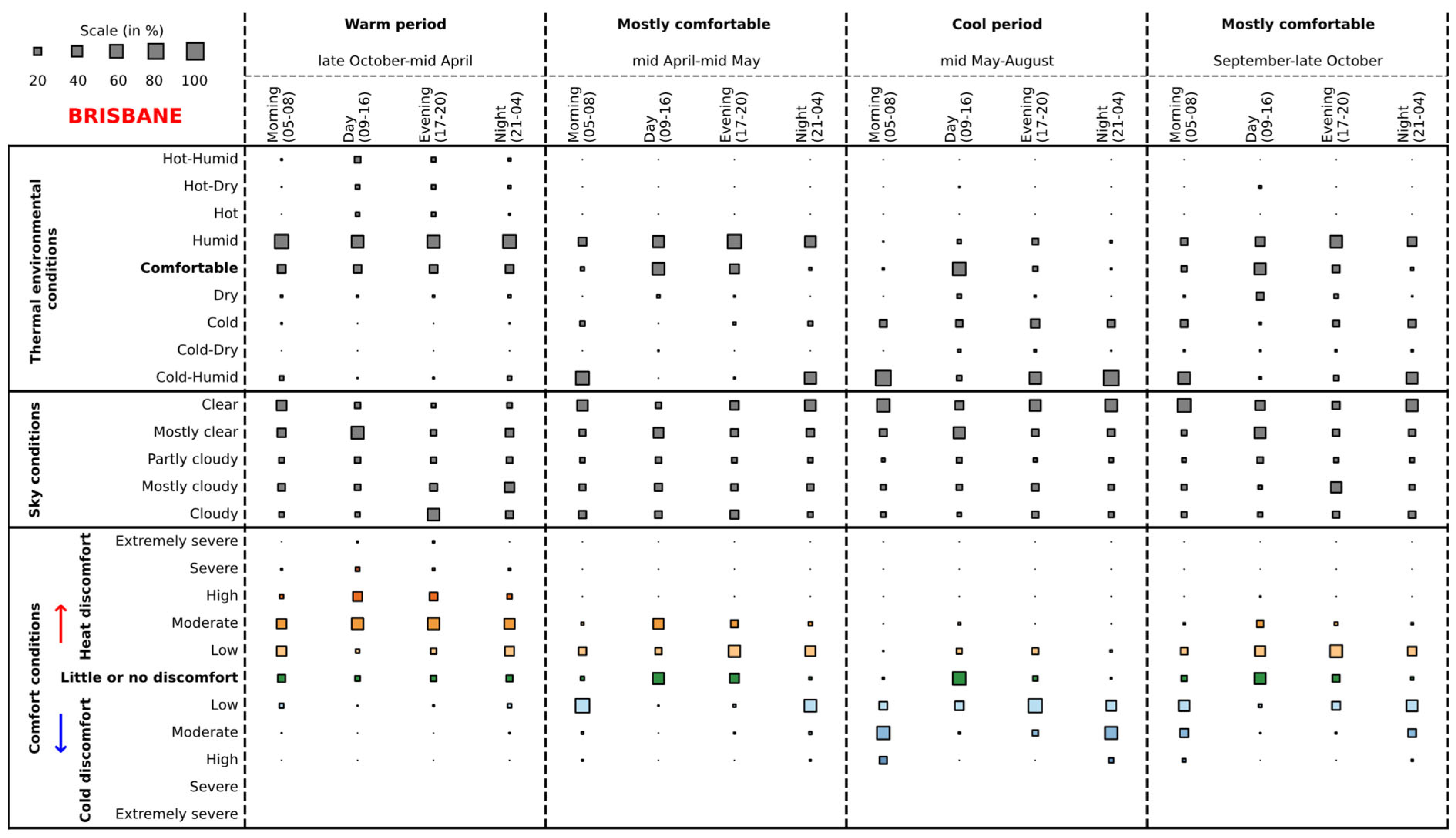

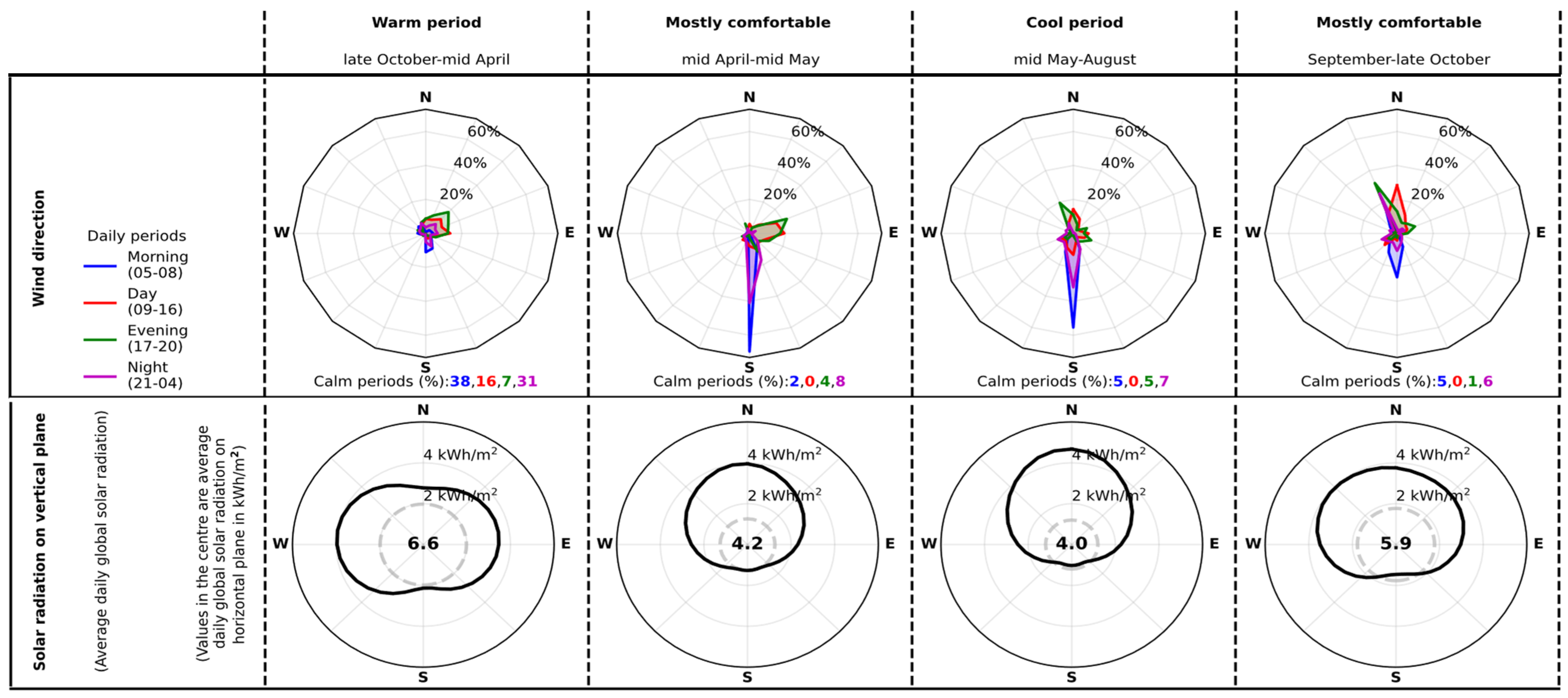

5.6. Climate Classification, Comfort, and System Performance

5.6.1. Climate Data and Climate Zones

5.6.2. Environmental Conditions and Seasonal Variation

- PV Systems: Fixed solar panels with optimal winter tilt angles to maximize energy supply in winter. Demand management, passive systems to reduce energy demand, and battery storage systems account for potential shading from cloud cover during the wet season and optimize output to service HVAC cooling loads and daily variations.

- HVAC Systems: Given the variability in temperature and humidity, HVAC systems should adjust for seasonal changes, with a focus on energy efficiency.

- Building Orientation: Buildings should ideally align east–west to maximize exposure to northern sunlight, particularly in winter months, but also shade against high summer sun angles.

- Water Management: Implement rainwater-harvesting systems to capitalize on the wet season and ensure water availability during drier months.

- Insulation and Ventilation: Adequate insulation will reduce heating and cooling costs, with natural ventilation utilized to maintain comfort during milder months.

5.6.3. Overheating and System Implications

5.7. Managing Energy Demand: Steps for Optimization

- Integrate Systems. Combining solar, passive, and active systems to optimize energy use by managing demand and supply is needed. A nuanced integration of environmental conditions among solar, passive, and active systems optimizes energy use by managing demand and supply fluctuations.

- Explore Scenarios: We examined solar energy supply scenarios based on thermal conditions, primarily categorized as ‘comfortable’:

- Self-sufficiency scenario: Maximize solar self-consumption and use of active systems during the day.

- Energy efficiency scenario: Improve system efficiency by replacing older appliances.

- Energy sufficiency scenario: Minimize active system usage and optimize operational timing based on climatic factors to avoid peak loads.

- Adjust System Usage: Managing end-use demand involves adjusting system usage between day and night (Table 9). For example, during the summer, self-sufficiency can be increased by operating all HVAC and water heating systems while reducing the usage of half the appliances and some cooking activities during daylight hours. This strategy can create a demand of 21.95 kW during those hours, with a smaller load at night. Ceiling fans and other passive cooling methods, such as open windows and flow-through ventilation, can likewise provide comfort at night.

- Implement passive cooling: Improving energy efficiency by utilizing passive cooling systems during the day can help reduce overall energy demand. However, the effectiveness of this approach relies on optimizing passive systems in a solar retrofit.

- Optimize solar retrofits; Additionally, retrofitting solar HWSs can enhance energy efficiency while drawing very little power, especially in the colder winter months. Although a heat pump water system would consume more energy than a standard electric storage hot water system, it still uses less energy overall [46].

5.8. Occupant Lifestyle Influences: Steps for Sustainable Design

- Consider Climate and Lifestyle: Queensland climate and outdoor living create opportunities that are mirrored in the design of pre-war houses. They return to past strategies, whereby people lived more closely and were more attuned to natural phenomena. From the evidence in this study, solar retrofitting with active and passive systems is a normal progression.

- Utilize Passive Systems: Leverage the natural airflow designs of pre-war Queensland homes for effective solar retrofitting and avoid deviating from this design to minimize reliance on energy-consuming air conditioning. The original design of these pre-war Queensland houses is inherently conducive to solar retrofitting in a subtropical climate. The layout, with living spaces on the upper floor, ground floor storage, cellular spaces, and semi-external areas like verandas, is a thoughtful response to the climate, maximizing airflow and solar control through the roof using minimal materials [47].

- Adopt Sustainable Retrofitting Strategies: In the case study situation, subsequent renovation of the house’s facade moved away from this design, potentially leading to the need for air conditioning. A sustainable solar retrofitting strategy should aim to minimize air conditioning since it is the largest end use of energy. The following strategies apply (Figure 9).

- East zone: Adding roof insulation is recommended. The lightweight construction of the house responds quickly to external temperatures and requires natural ventilation for cooling and solar control through roof insulation.

- North zone: Adapting the ground floor for storage and rumpus space is a feasible use.

- South zone: Changing the kitchen layout would result in a less complex interior, and more operable windows could be added for ventilation. Adding external semi-enclosed spaces, such as a pergola, could enhance the experience of the garden.

- Return to the Original Design: Revive the north–south orientation which enhances cross-ventilation and enables independence from active systems. Extend the roof to create shading and space for solar panels, improving daylighting, which includes a north–south axis and could lead to microclimatic adaptations. Retaining this form is a relevant conservation strategy and could simplify planning while improving cross-ventilation, enhancing the building’s capability to operate without active systems. Extending the roof area to the east for verandas and shading to reduce the morning sun in summer would also be beneficial. This approach would increase space for solar thermal panels for water heating. Adding skylights would add more daylight indoors. The current east–west orientation of the roof reduces solar panel efficiency by 10–20%, highlighting the importance of retrofitting for the microclimate [48].

5.9. Active Systems: Steps in Design Management

- Manage HVAC and Water Heating: Use HVAC systems during peak months to manage discomfort and schedule water heating during the day. A focus on demand management centres on controlling the operation of the two main end-use items: HVAC and water heating. The typical pattern for use in the existing house is to operate the HVAC system to alleviate severe discomfort in the three months of winter and summer. Water heating takes place during the night with off-peak electricity. Experimenting with alternative demand management scenarios revealed the significant impact of three distinct energy usage schedules to better integrate solar, active, and passive systems in the building.

- Increase Self-Sufficiency: This involves scheduling all HVAC and water heating usage, half of the appliances’ usage, and some cooking during daylight hours. Low-energy technologies, such as ceiling fans, can provide comfort at night. The daily daytime demand of 21.95 kWh is met by solar power; the nighttime demand of 4.66 kW is met by grid or battery power (Table 9).

- Enhance Energy Efficiency: Replacing the current electric HWS with a solar hot water system significantly reduces power demand to 4 kW [33,46]. An important energy efficiency measure is to prioritize replacing existing systems that are consciously and extensively used, i.e., fridges and HWSs Replacing and improving the efficiency of HVAC systems and appliances would further reduce demand (assume 30%). Daily daytime demand is reduced to 14.1 kWh, which is met by solar power, and the nighttime demand is 3.67 kWh (Table 9).

- Improve Energy Sufficiency: This involves operating passive heating and cooling systems during the day and night, in the low-discomfort months of April, May, October, and November. Hence, updating the present passive systems in conjunction with the solar retrofit is central to the energy savings. Daily daytime demand is reduced to 3.4 kWh, which is met by solar power, and the nighttime demand is 3.4 kWh (Table 9).

5.10. Export Opportunities

- Fixed energy exporting to the grid is limited for safety and security reasons;

- Flexible connection permits variability (e.g., quantity requirements and time of day considerations) in export limiting and can be used for grid safety and security reasons;

- DC coupling, batteries, and panels can be connected before conversion to AC (as seen in residential System 2).

- How efficient will the new technical advance be for households?

- How much of this power can displace fossil generation in the supply chain, or will it be sold back to households?

5.11. Emissions, Carbon Abatement, and Tariff Plans

- The difference between the FIT and Peak tariff costs. This is an indicator of the business case for PV and reduction in emissions.

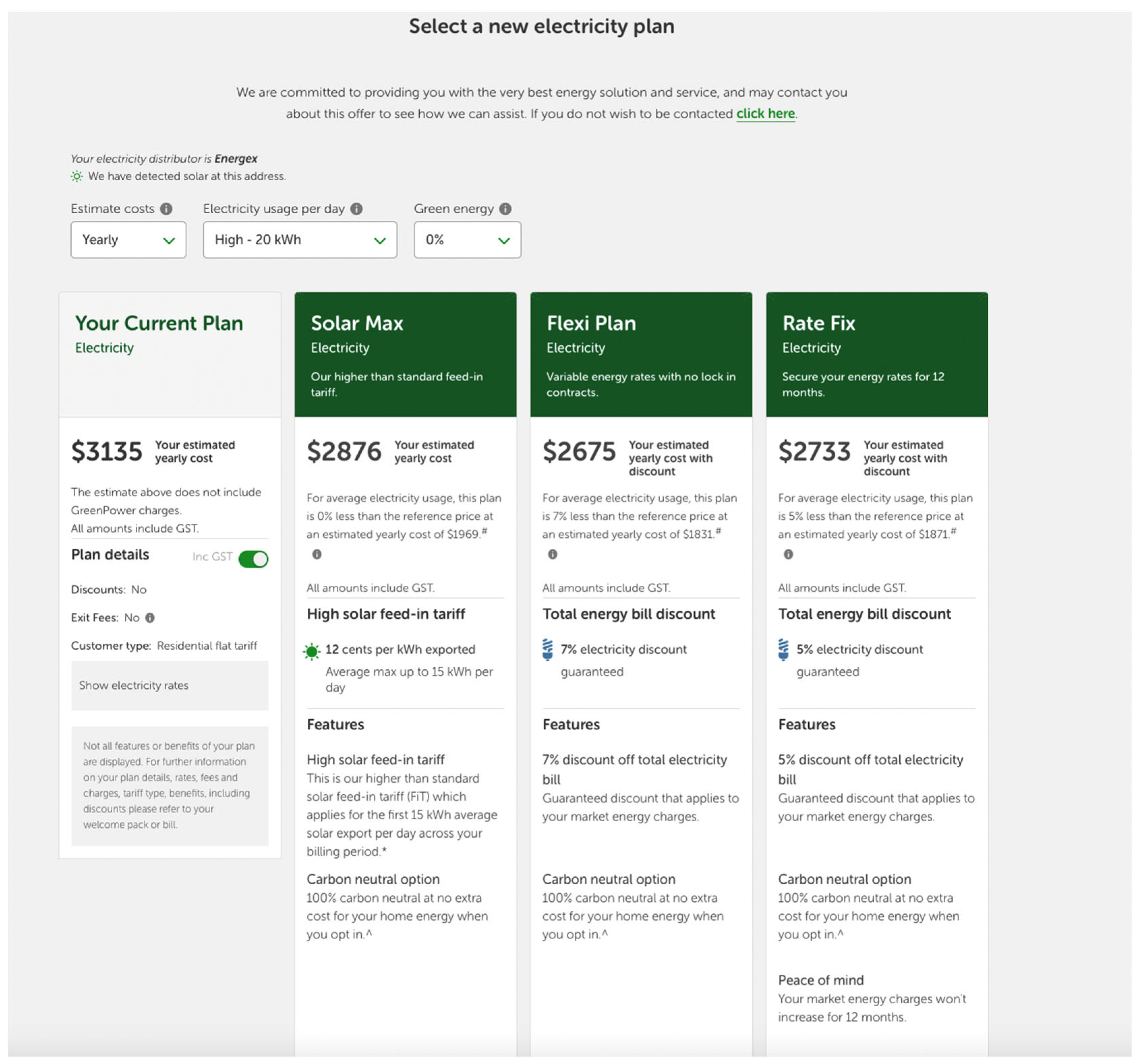

- The tariff plans offered are very similar; the Solar Max system could better model the potential costs, factor in self-consumption, or acknowledge that self-consumption is not included.

- Illustration of a more realistic comparison is shown from this study.

- The servicing from the grid with green power costs AUD 480.60, bringing the total cost to 4085.08 AUD per annum. System 1, the servicing from panels, reduces the cost to 34% of the amount quoted above. Green power costs AUD 218, reducing cash flow for payback on the solar system. Some households could regard this trade-off as a contradiction. As shown for System 3, the panel and battery combination reduces household electricity costs to 342 AUD per annum.

- The emissions calculations are no longer provided nor historical data on household performance.

6. Discussion

- System characteristics: uncertainty about solutions, performance, and benefits.

- Affordability: related to a high cost of living and tight cash flow.

- Supply: perceptions of a high cost of energy and low environmental impact, i.e., little reduction in emissions (system service maintenance requirements or costs are not included; all benefits must, therefore, be assumed as gross figures).

- Technology: the view that new technologies have little benefit and are too expensive and capital costs are too high.

7. Conclusions

8. Research Limitations/Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| HWS | Hot water system |

| HVAC | Heating ventilation and air conditioning |

| HP | Heat pump |

| AC, DC | Alternating current, direct current |

Appendix A. Energy and Cost Balance

| Case 0: Servicing from Grid | |||

| Daily consumption, kWh | Annual consumption | Annual cost at 0.331386 AUD per kWh | |

| 26.6 | 9709 | AUD 3217.43 | |

| Supply charge | Supply charge at 1.060400 AUD per day | ||

| 365 | AUD 387.05 | ||

| Green power | Annual cost at 0.0495 AUD per kWh | ||

| AUD 480.60 | Balance | ||

| Total debits | AUD 4085.08 | 0 | |

| Case 1: Existing System, serviced by off-peak electricity | |||

| Average daily consumption | Annual grid consumption | Annual cost at 0.331386 AUD per kWh | |

| 19.95 | 7281.75 | AUD 2402.98 | |

| Supply charge per day | Supply charge at 1.060400 AUD per day | ||

| 365 | AUD 387.05 | ||

| Existing water heater | Annual cost at 0.15 AUD per kWh | ||

| 6.65 | 2427.25 | AUD 364.08 | |

| Green power | Annual cost at 0.0495 AUD per kWh | ||

| 7281.75 | AUD 360.45 | ||

| Total debits | AUD 3514.56 | Balance | |

| Total credits | AUD 0.00 | −AUD 3514.56 | |

| Case 2: System 1, servicing from 10 kW solar electric panels and heat pump water heater | |||

| Daily consumption | Annual consumption | Annual cost at 0.331386 AUD per kWh | |

| 10.91 | 3982.15 | AUD 1314.11 | |

| Supply charge per day | Supply charge at 1.060400 AUD per day | ||

| 365 | AUD 387.05 | ||

| 10 kW solar production | Annual generation | Debits | AUD 1701.16 |

| 42.5 | 15,512.5 | ||

| Self-consumption | |||

| 9.04 | 3299.6 | AUD 1088.87 | |

| Heat pump water heater | |||

| 6.65 | 2427.25 | AUD 800.99 | |

| Solar power exported | Annual energy balance | Buy back at 0.066 AUD per kWh | |

| 26.81 | 9785.65 | AUD 645.85 | |

| Green power | Annual cost at 0.0495 AUD per kWh | ||

| AUD 197.12 | |||

| 26.6 | Total debits | AUD 1898.28 | Balance |

| Total credits | AUD 2535.71 | AUD 637.44 | |

| Case 3: System 2, servicing from 10.kW kW solar electric panels and 9.6 kW battery | |||

| Daily consumption | Annual consumption | Annual cost at 0.331386 AUD per kWh | |

| 1.31 | 478.15 | AUD 157.79 | |

| Supply charge per day | Supply charge at 1.060400 AUD per day | ||

| 365 | AUD 387.05 | ||

| 10 kW PV generation | Annual generation | ||

| 42.5 | 15,512.5 | ||

| Self-consumption | |||

| 9.04 | 3299.6 | AUD 1088.87 | |

| Existing hot water system | |||

| 6.65 | 2427.25 | AUD 800.99 | AUD 1889.86 |

| 9.6kW battery | |||

| 9.6 | 3504 | AUD 1156.32 | |

| Remaining PV generation | Annual energy balance | Buy back rate at 0.066 AUD per kWh | |

| 23.86 | 8708.9 | AUD 574.79 | |

| Total debits | AUD 544.84 | Balance | |

| Total credits | AUD 2819.98 | AUD 2275.14 | |

| Case 4: System 3, servicing from 10 kW solar electric panels and HP water heater | |||

| Daily consumption | Annual consumption | Annual cost at 0.331386 AUD per kWh | |

| 10.91 | 3982.15 | AUD 1314.11 | |

| Supply charge per day | Supply charge at 1.060400 AUD per day | ||

| 365 | AUD 387.05 | ||

| 9.6kW PV generation | Annual generation by PVs | ||

| 42.8 | 15,622 | ||

| Self-consumption | |||

| 9.04 | 3299.6 | AUD 1088.87 | |

| Heat pump water heater | |||

| 6.65 | 2427.25 | AUD 800.99 | |

| Remaining PV generation | Annual energy balance | Buy back rate at 0.066 AUD per kWh | |

| 27.11 | 9895.15 | AUD 653.08 | |

| Green power | Annual cost at 0.0495 AUD per kWh | ||

| AUD 197.12 | |||

| Total debits | AUD 1701.16 | Balance | |

| Total credits | AUD 2542.94 | AUD 841.78 | |

References

- Welch, S.E.; Memari, A.M. A review of the previous and current challenges of passive house retrofits. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion Homes, Knockdown and Rebuild. Available online: https://www.championhomes.com.au/knockdown-rebuild (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Levin, H. Systematic Evaluation and Assessment of Building Environmental Performance; SEABEP: Washington, DC, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Queensland Government. Queensland Development Code, Mandatory Part 4.1—Sustainable Buildings. 2025a. Available online: https://www.housing.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0019/36064/QDCMP4.1SustainableBuildings.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Ali, H.M. (Ed.) Advances in Nanofluid Heat Transfer; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Government. Australian National Greenhouse Accounts Factors, for Individuals and Organizations Estimating Greenhouse Gas Emissions. 2024b. Available online: https://www.dcceew.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/national-greenhouse-accounts-factors-2022.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Sorrell, S.; Gatersleben, B.; Druckman, A. The limits of energy sufficiency: A review of the evidence for rebound effects and negative spillovers from behavioural change. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 64, 101439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KR Foundation. Energy Sufficiency. Available online: https://www.energysufficiency.org/about/contact-and-about/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Smappee. How Are Self-Consumption and Self-Sufficiency Calculated? Available online: https://support.smappee.com/hc/en-gb/articles/360044277371-How-is-Self-Consumption-and-Self-Sufficiency-calculated-#:~:text=Self%2Dsufficiency%20is%20the%20percentage,%2D%20Import)%20%2F%20Total%20consumption (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Hauberg, J. Research by Design: A Research Strategy. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Jorgen-Hauberg-2/publication/279466514_Research_by_design_a_research_strategy/links/6055b61492851cd8ce52b3cb/Research-by-design-a-research-strategy.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Roggema, R. Research by design: Proposition for a methodological approach. Urban Sci. 2016, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvimaki, M. Case Study Strategies for Architects and Designers: Integrative Data Research Methods; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nnaemeka, C.N. Case Study as a Tool for Architectural Research. Acad. Edu. 2015, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde, R.; Watson, S.; Cheshire, W.; Thomson, M. The Environmental Brief: Pathways for Green Design; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, S. Front-Loading the Building Design Process for Environmental Benefit. Available online: https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:10116/Watson_paper_CRC.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- QHES, Queensland Household Energy Survey. Available online: https://qhes.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/2023-QHES-Report.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Australian Government. Solar Consumer Guide; Department of Climate Change, Energy, Environmental and Water: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2025. Available online: https://www.energy.gov.au/solar (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Australian Energy Regulator. Residential Energy Consumption Benchmarks. Final Report for the Australian Energy Regulator. Available online: https://www.aer.gov.au/system/files/Residential%20energy%20consumption%20benchmarks%20-%209%20December%202020_0.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Wingrove, K.; Heffernan, E.; Daly, D. Increased home energy use: Unintended outcomes of energy efficiency focused policy. Build. Res. Inf. 2024, 52, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campey, T.; Bruce, S.; Yankos, T.; Hayward, J.; Graham, P.; Reedman, L.; Brinsmead, T.; Deverell, J. Low Emissions Technology Roadmap; CSIRO: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2017.

- Solar Run. How to Increase Your Solar Self-Consumption. 2023. Available online: https://www.solarrun.com.au/how-to-increase-your-solar-self-consumption/#Purchase_an_electric_car (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Vorrath, S. Rooftop Solar Saves Money, and Batteries Can Wipe Out Bills: Labor Pushes Household Savings, Renew Economy. Available online: https://reneweconomy.com.au/rooftop-solar-saves-money-and-batteries-can-wipe-out-bills-labor-pushes-household-savings/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Office of Renewable Efficient and Renewable Energy. End-of-Life Management for Solar Photovoltaics, USA. Available online: https://www.energy.gov/eere/solar/end-life-management-solar-photovoltaics (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Kiran, D.R. (Ed.) Chapter Twenty-Two—Machinery Replacement Analysis. In Principles of Economics and Management for Manufacturing Engineering; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 259–267. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780323998628000029 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Torcellini, P.; Pless, S.; Deru, M.; Crawley, D. Zero Energy Buildings: A Critical Look at the Definition; No. NREL/CP-550-39833; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2006.

- Clean Energy Council, Costs and Savings. Available online: https://www.cleanenergycouncil.org.au/consumers/buying-solar/costs-and-savings (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Sustainability Victoria, Comprehensive Energy Efficient Retrofits to Existing Victorian Houses. Available online: https://assets.sustainability.vic.gov.au/susvic/Report-Energy-Comprehensive-Energy-Efficiency-Retrofits-to-Existing-Victorian-Houses-PDF.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Climate Change Portal—For Development Practitioners and Policy Makers. Available online: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/climate-change-overview#:~:text=High%2Dend%20emissions%20scenario%20(RCP8,to%20pre%2Dindustrial%20temperature%20levels (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- IEA PVPS Programme, Fact Sheet: Environmental Life Cycle Assessment of Electricity from PV Systems. Available online: https://iea-pvps.org/fact-sheets/fact-sheet-environmental-life-cycle-assessment-of-electricity-from-pv-systems/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Solar Choice, Tilting Solar Panels. Available online: https://www.solarchoice.net.au/blog/solar-panel-tilt-and-orientation-in-australia/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- BOM. Average Annual and Monthly Heating and Cooling Degree Days. 2023a. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/maps/averages/degree-days/?maptype=hdd18&period=an. (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- University of Queensland, Local Weather Can Have a Dramatic Effect on the Electricity Production from a PV Array. Available online: https://solar-energy.uq.edu.au/about/weather-and-local-environment (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Sustainability Victoria. Compare Water Heating Running Costs. Available online: https://www.sustainability.vic.gov.au/energy-efficiency-and-reducing-emissions/save-energy-in-the-home/water-heating/calculate-water-heating-running-costs (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Your Home, Hot Water Systems. Available online: https://www.yourhome.gov.au/energy/hot-water-systems (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Sigenergy. How Hybrid Inverters Optimize Energy Efficiency for Homes. Available online: https://www.sigenergy.com/en/news/info/1693.html (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Harvard Business School, Discounted Cash Flow (dcf) Formula: What It Is & How to Use It. Available online: https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/discounted-cash-flow (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- BOM. Climate Classification Maps. Available online: https://www.bom.gov.au/jsp/ncc/climate_averages/climate-classifications/index.jsp. (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Brisbane Climate. Adapted from Wki. 2024. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Climate_of_Brisbane#cite_note-1 (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Climate Consultant. Available online: https://climate-consultant.informer.com/6.0/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Upadhyay, A.K. Climate information for building designers: A graphical approach. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2017, 61, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Change Committee. Risks to Health, Wellbeing and Productivity from Overheating in Buildings. Available online: https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Risks-to-health-wellbeing-and-productivity-from-overheating-in-buildings.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- McArdle, P. Queensland Electricity Demand Climbs Higher Still, on Friday 29th December 2023, WattClarity. Available online: https://wattclarity.com.au/articles/2023/12/29dec-qld-demand-higher-still/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- BOM, Greater Brisbane in Summer 2022-23: Below Average Rainfall, Cooler Nights. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/current/season/qld/archive/202302.brisbane.shtml#:~:text=The%20mean%20daily%20maximum%20temperature,temperature%20reached%2022.3%20°C (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Engel, P. How to Save Money on Your Home Heating and Cooling Costs|Choice. Available online: https://www.choice.com.au/home-and-living/cooling/air-conditioners/articles/air-conditioner-energy-saving-tips#:~:text=%22But%20generally%2C%20for%20the%20best,cooler%20than%20the%20outside%20temperature.&text=%22So%20if%20it%27s%20a%20sweltering,%27ll%20cost%20you%20less.%22 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Worrol, P. Queensland Experts Advise on Heatwave-Proof Housing Amid AC Use. Available online: https://www.miragenews.com/queensland-experts-advise-on-heatwave-proof-1150355/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Sustainability Victoria. Heat-Pump Hot Water Systems. Available online: https://www.sustainability.vic.gov.au/energy-efficiency-and-reducing-emissions/save-energy-in-the-home/water-heating/choose-the-right-hot-water-system/heat-pump-water-heaters (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Evans, I. The Queensland House; Flannel Flower Press: Mullumbimby, NSW, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Solar Calculator. What If Your Panels Don’t Face North? Available online: https://solarcalculator.com.au/solar-panel-orientation/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Wazed, S. NCC2025 Energy Efficiency-Advice on the Technical Basis. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/12289823/ncc2025-energy-efficiency/13183863/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- UPEC. What Does Traditional and Character Housing Look Like? The Urban and Regional Planning Education Centre. Available online: https://urpec.com.au/what-does-traditional-and-character-housing-look-like/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Bennett, A. Understanding Australian Solar in 2024: Three Key Concepts to Master. Available online: https://www.solarquotes.com.au/blog/three-key-concepts-2024/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Queensland Competition Authority. Draft Determination—Solar Feed-In Tariff for Regional Queensland 2023–24. Available online: http://www.qca.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/solar-feed-in-tariff-2023-24-draft-determination-draft-determination-final.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Energex. Dynamic Connections for Energy Exports. Available online: https://www.energex.com.au/our-services/connections/residential-and-commercial-connections/solar-connections-and-other-technologies/dynamic-connections-for-energy-exports (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Sujeetha, S.; Erik, O.; Ahlgren, E. Determining the factors of household energy transitions: A multi-domain study. Technol. Soc. 2019, 57, 54–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, M.; James, M.; Law, A.; Osman, P.; White, S. The Evaluation of the 5-Star Energy Efficiency Standard for Residential Buildings; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Household System | Type | Water (Litres) | Daily Electricity Use (kW) | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HVAC | Air conditioning | 7 | Kitchen | |

| HVAC | Heat pump | 8.3 | Kitchen | |

| Lighting | Lighting and ceiling fans | 0.015–0.09 | Bedrooms and living room | |

| HWS | Electric storage | 80 (small unit) | 1.8 | Interior or exterior |

| Appliances | Electric stove, fridge, television, and computers | Kitchen and other locations |

| Hardware and Performance | System 1: Residential Grid-Tied Solution with Heat Pump HWS | System 2: Residential Grid-Tied and Storage System | System 3: Residential Grid-Tied Heat Pump HWS, Battery-Ready |

|---|---|---|---|

| System hardware | |||

| System size | 10.375 kW | 10.375 kW | 9.6 kW |

| Solar panels, number and power | 25 × 415 W | 25 × 415 W | 22 × 440 W |

| Inverter types: grid-tied and hybrid | 10 kW | PV 5 kW + Hybrid 5 kW | Hybrid inverter 8 kW |

| Battery | None | 9.6 kW | None |

| HP/HWS | 270 litres | None | 270 litres |

| Economic performance | |||

| Annual electricity bill after solar | AUD 593 | AUD 468.47 | |

| Undiscounted lifetime electricity bill savings | AUD 50,919.00 | AUD 61,611.00 | AUD 23,789.00 (10 years payback) |

| System costs, including services and rebates | AUD 13,980.00 | AUD 15,999.00 | AUD 16,280.00 |

| Net nominal savings | AUD 36,939.00 | AUD 45,612.00 | AUD 7509.00 |

| System performance | |||

| Daily solar | 42.5 | 42.2 | 42.8 |

| Yearly output, kWh | 1512.5 | 1540.3 | 1562.2 |

| Grid energy imported | 21% | 21% | 30% |

| Solar energy to battery | 0% | 21% | 0 |

| Self-consumption | 21% | 42% | 30% |

| Export to the grid | 79% | 58% | 70% |

| Environmental performance | |||

| C02 removal, tons per year | 12.3 | 12.3 | 11.41 |

| Systems | Existing System | System 1 | System 2 | System 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System Demand | System Demand per Cent | Daily kWh | Day | Night | Day | Night | Day | Night | Day | Night |

| HVAC | 40% | 10.64 | 5.32 | 5.32 | 5.32 | 5.32 | 5.32 | 5.32 | 5.32 | 5.32 |

| Appliances | 23% | 6.12 | 3.06 | 3.06 | 3.06 | 3.06 | 3.06 | 3.06 | 3.06 | 3.06 |

| Battery | 9.6 | −9.60 | ||||||||

| Hot water | 25% | 6.65 | 0 | 6.65 | 6.65 | 6.65 | 6.65 | |||

| Lighting | 7% | 1.86 | 0 | 1.86 | 0 | 1.86 | 0 | 1.86 | 0 | 1.86 |

| Cooking | 5% | 1.33 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

| Total | 100% | 26.60 | 9.05 | 17.56 | 15.70 | 10.91 | 25.30 | 1.31 | 15.70 | 10.91 |

| Existing System | System 1 | System 2 | System 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily electricity consumption, kWh | 26.6 | 26.6 | 26.6 | 26.2 |

| Daily av. solar energy production, kWh | 0 | 42.5 | 42.2 | 42.8 |

| Energy imported, kWh | 0 | 10.91 | 1.9 | 11.97 |

| Solar energy consumed, kWh | 0 | 15.70 | 25.18 | 15.70 |

| Solar energy exported, kWh | 0 | 26.92 | 17.66 | 26.92 |

| Self-consumption, % | 0 | 36.% | 60% | 36% |

| Self-sufficiency, % | 0 | 59% | 98% | 59% |

| Cost-Effectiveness Methodology | Existing System | System 1 | System 2 | System 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Calculate Annual Costs and Usage | ||||

| Review the potential 12 months of electricity bills to find total kWh usage or estimate by multiplying average daily usage by 365 | 9709 | 9709 | 9709 | 9709 |

| Add total electricity debits for a typical year | −AUD 2790 | −AUD 1701.00 | −AUD 545.00 | −AUD 1701.00 |

| Add carbon offsetting costs of green power | −AUD 360.00 | −AUD 197.00 | AUD 0.00 | −AUD 197.00 |

| Add off-peak costs | −AUD 362.00 | |||

| Total | −AUD 3511 | AUD 1898.00 | −AUD 545.00 | −AUD 1898.00 |

| Step 2: Estimate Solar System Savings | ||||

| Estimate annual energy generation based on system size kW | 15,513 | 15,513 | 15,622 | |

| Calculate savings from using generated electricity instead of grid power; consider using high-energy appliances and demand management during peak solar hours (self-consumption) | AUD 1088.00 | AUD 1890.00 | AUD 1088.00 | |

| Calculate savings from solar hot water system (self-consumption) | AUD 801.00 | AUD 801.00 | ||

| Calculate savings from battery system (self-consumption) | AUD 1156.00 | |||

| Factor in any feed-in tariff for excess power sold back to the grid | AUD 646.00 | AUD 574.00 | AUD 653.00 | |

| Total | AUD 2535.00 | AUD 3465.00 | AUD 2542.00 | |

| Step 3: Calculate Net Cost | ||||

| Start with the gross cost of the system | AUD 13,980.00 | AUD 15,990.00 | AUD 16,280.00 | |

| Deduct government incentives (rebates, tax credits, etc.) | Included | Included | Included | |

| Add financing costs if applicable | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Step 4: Calculate Payback Period | ||||

| Divide the net cost by annual savings for an estimate of payback time | 21.95 | 8.33 | 25.28 | |

| Consider potential increases in energy prices and any solar incentives: deduct from annual bill savings; annual increase of 3.6% | AUD 68.33 | AUD 19.62 | AUD 68.33 | |

| Step 5: Use Online Calculators | ||||

| Utilize tools like the solar calculator for a personalized savings and payback estimate based on the specific system characteristics | ||||

| Discount Cash Flow (DCF) and Net Present Value (NPV) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| NPV adds a fourth step to the DCF calculation process. After forecasting the expected cash flows, selecting a discount rate, discounting those cash flows, and totalling them, NPV then deducts the upfront cost of the investment from the DCF. Formula: The NPV is the sum of all future cash flows (inflows minus outflows), discounted to the present. | |||

| Steps to Calculate the DCF | System 1 | System 2 | System 3 |

| 1. Estimate annual savings: Determine potential savings on the electricity bill each year. | AUD 638.00 | AUD 1920 | AUD 645 |

| 2. Consider potential increases in energy prices and any solar incentives: Add to energy costs. | 3.60% | 3.60% | 3.60% |

| 3. Choose a discount rate: Select a discount rate (r) that reflects the opportunity cost of money (the rate of return which could be earned on an alternative investment). A higher discount rate will result in a lower present value. | 5% | 5% | 5% |

| 4. Calculate the present value (PV) for each year: Use the formula to find the present value for each of the 10 years. The formula for each year is PVt = Savingst(1 + r)t | |||

| Years | System 1 | System 2 | System 3 |

| 1 | AUD 587.48 | AUD 1767.96 | AUD 593.92 |

| 2 | AUD 540.95 | AUD 1627.95 | AUD 546.89 |

| 3 | AUD 498.12 | AUD 1499.03 | AUD 503.58 |

| 4 | AUD 458.67 | AUD 1380.33 | AUD 463.70 |

| 5 | AUD 416.97 | AUD 1254.84 | AUD 421.55 |

| 6 | AUD 383.95 | AUD 1155.47 | AUD 388.17 |

| 7 | AUD 353.55 | AUD 1063.97 | AUD 357.43 |

| 8 | AUD 325.55 | AUD 979.72 | AUD 329.12 |

| 9 | AUD 299.77 | AUD 902.13 | AUD 303.06 |

| 10 | AUD 276.03 | AUD 830.69 | AUD 279.06 |

| 5. Compare with the initial investment: Subtract the initial investment from the total DCF to find the net present value (NPV). A positive NPV indicates that the investment is potentially profitable. | |||

| System 1 | System 2 | System 3 | |

| Initial investment | AUD 13,980.00 | AUD 15,990.00 | AUD 16,280.00 |

| DCF | AUD 4141 | AUD 12,462 | AUD 4186 |

| NPV | −AUD 9838.95 | −AUD 3527.91 | −AUD 12,093.52 |

| Climate Variable | Monthly Average | Design Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Solar irradiance | High in summer; lower in winter, averaging 5–6 kWh/m2/day. | Optimize solar panel tilt at 27–30 degrees for efficiency; consider shading during peak summer months. |

| Temperature | Summer highs: up to 43.2 °C; winter lows: around 6 °C. | Design heating and cooling systems to handle extreme temperatures; ensure insulation for energy efficiency. |

| Humidity | High in summer (60–80%); low in winter (40–60%). | Incorporate dehumidification solutions in summer months; ensure ventilation to manage indoor air quality. |

| Precipitation | Wet season in summer; dry winter months. | Design for runoff with proper drainage; consider water catchment systems for dry months. |

| Wind speed | Velocity of 1 and 7 m/s. Strong wind conditions. | Design for natural ventilation. |

| Sky cover | High in humid period January–May. | Variable solar output during the humid period means optimum demand management. Ensure structural stability of outdoor installations. |

| Comfort | Comfortable April, May, October, and November. | Develop seasonal strategies for heating and cooling; enhance indoor comfort during milder months. |

| Grid-Tied System Solution Performance | kWh |

|---|---|

| Electricity consumption, kWh | 58.59 |

| Solar energy production, kWh | 55.10 |

| Energy imported, kWh | 4.14 |

| Solar energy consumed, kWh | 55.1 |

| Solar energy exported, kWh | 0 |

| Self-consumption | 100.00% |

| Self-sufficiency | 92.93% |

| System Demand | Self-Consumption Mode | Energy Efficiency Mode | Energy Sufficiency Mode | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategies | Maximize direct solar usage | Maximize system efficiency | Minimize system usage | |||

| Day | Night | Day | Night | Day | Night | |

| HVAC | 10.64 | 0 | 6.44 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Appliances | 3.06 | 3.06 | 2.06 | 2.06 | 2.06 | |

| Water heating | 6.65 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0. |

| Lighting and ceiling fans | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

| Cooking | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 |

| Total | 21.95 | 4.66 | 14.10 | 3.67 | 3.40 | 3.40 |

| Energy demand | 26.6 | 17.75 | 6.80 | |||

| Solar Max | Flexi Plan | Rate Fixed | Grid Service | Existing System | System 1 | System 2 | System 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usage per day | 20 kWh | 20 kWh | 20 kWh | 26.6 kWh | 26.6 kWh | 26.6 kWh | 26.6 kWh | 26.6 kWh |

| Estimated cost | AUD 2876.00 | AUD 2675 | AUD 2733.00 | AUD 4085.00 | AUD 3514.00 | AUD 1898.00 | AUD 544.00 | AUD 1701 |

| Peak | AUD 0.33 | AUD 3217.00 | AUD 2402.00 | AUD 1314.00 | AUD 158.00 | AUD 1314.00 | ||

| Supply charge/day AUD 1.55 | AUD 1.06 | AUD 387.00 | AUD 387.00 | AUD 387.00 | AUD 387.00 | AUD 387.00 | ||

| Feed-in tariff | AUD 0.06 | AUD 645.00 | AUD 0.00 | AUD 653.00 | ||||

| Green power | AUD 0.04 | AUD 480.00 | AUD 360.00 | AUD 197.00 | AUD 0.00 | AUD 187.00 | ||

| Discounts | 0% | 7% |

| System Constraints | |||

| Perception of the costs and benefits. | Uncertainty about the specific benefits of solar retrofitting for households in subtropical climates | Households unsure that the right solar system for their needs and budget is selected | Lack of awareness of key decision-making factors that households and consultants must consider when planning for solar retrofitting |

| Affordability Constraints | |||

| Households are looking at ways to reduce consumption and change behaviour as the cost of living increases. | Reduce demand through energy conservation and low energy technologies for cooling and heating | Select the energy system they can afford, and as older appliances reach their end of life, replace them with solar thermal and solar electric systems | Explore the energy plans available such as time-of-use tariff, solar max plans, and green power to offset emissions |

| Supply Constraints | |||

| Electricity suppliers are looking at issues of cost and value for money. | Explore opportunities to manage demand through energy self-sufficiency, energy efficiency, and energy sufficiency | Utilize subsidies and market discounts | Prioritize solar energy for peak demand in electricity generation to meet needs for space cooling and solar thermal power for water heating |

| Technological Constraints | |||

| Household interest in and uptake of new-energy technology has waned. | Reduce demand by using passive systems in the building | Prioritize solar electricity generation | Use low-cost systems with the ability to be extended, i.e., battery-ready, and add more panels when efficiency improves |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hyde, R.; Wadley, D.; Hyde, J. Household Challenges in Solar Retrofitting to Optimize Energy Usage in Subtropical Climates. Energies 2025, 18, 6312. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236312

Hyde R, Wadley D, Hyde J. Household Challenges in Solar Retrofitting to Optimize Energy Usage in Subtropical Climates. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6312. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236312

Chicago/Turabian StyleHyde, Richard, David Wadley, and John Hyde. 2025. "Household Challenges in Solar Retrofitting to Optimize Energy Usage in Subtropical Climates" Energies 18, no. 23: 6312. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236312

APA StyleHyde, R., Wadley, D., & Hyde, J. (2025). Household Challenges in Solar Retrofitting to Optimize Energy Usage in Subtropical Climates. Energies, 18(23), 6312. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236312