Advancing Hybrid AC/DC Microgrid Converters: Modeling, Control Strategies, and Fault Behavior Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- The control–hardware dependency, where advanced controller designs such as MPC, virtual inertia, or adaptive droop are constrained by semiconductor limits and computational cost.

- The survivability–resilience linkage, in which software-based fault ride-through capabilities fundamentally rely on ultra-fast hardware protection such as SSCBs to prevent destructive VSC capacitor discharge.

- The application-driven bifurcation between LV and MV systems, where different operational requirements lead to divergent trade-offs in semiconductor technology (GaN vs. SiC), control bandwidth, and protection philosophy.

2. Power Converters Utilized in AC/DC MGs

2.1. An Introduction to Power Converter Selection

- Low impedance: This reduces power losses and enhances voltage regulation, improving overall system efficiency [12].

- Bidirectional power flow: Enables efficient energy exchange between AC and DC sub-grids, ensuring seamless operation [13].

- Stable voltage and frequency regulation: Maintains consistent voltage and frequency levels, ensuring the reliability of the MG [14].

- Grid-forming power converter (GFPC)

- 2.

- Grid-following power converter (GFLPC)

- 3.

- Grid-supporting power converter (GSPC)

- 4.

- Interlinking power converter (IPC)

2.2. Different Types of Converters in Hybrid AC/DC MGs

2.2.1. AC-DC and DC-AC Converters (Rectifiers and Inverters)

2.2.2. DC-DC Converters

2.2.3. Control of Interlinking Converters

2.2.4. Multilevel Converters (MLCs)

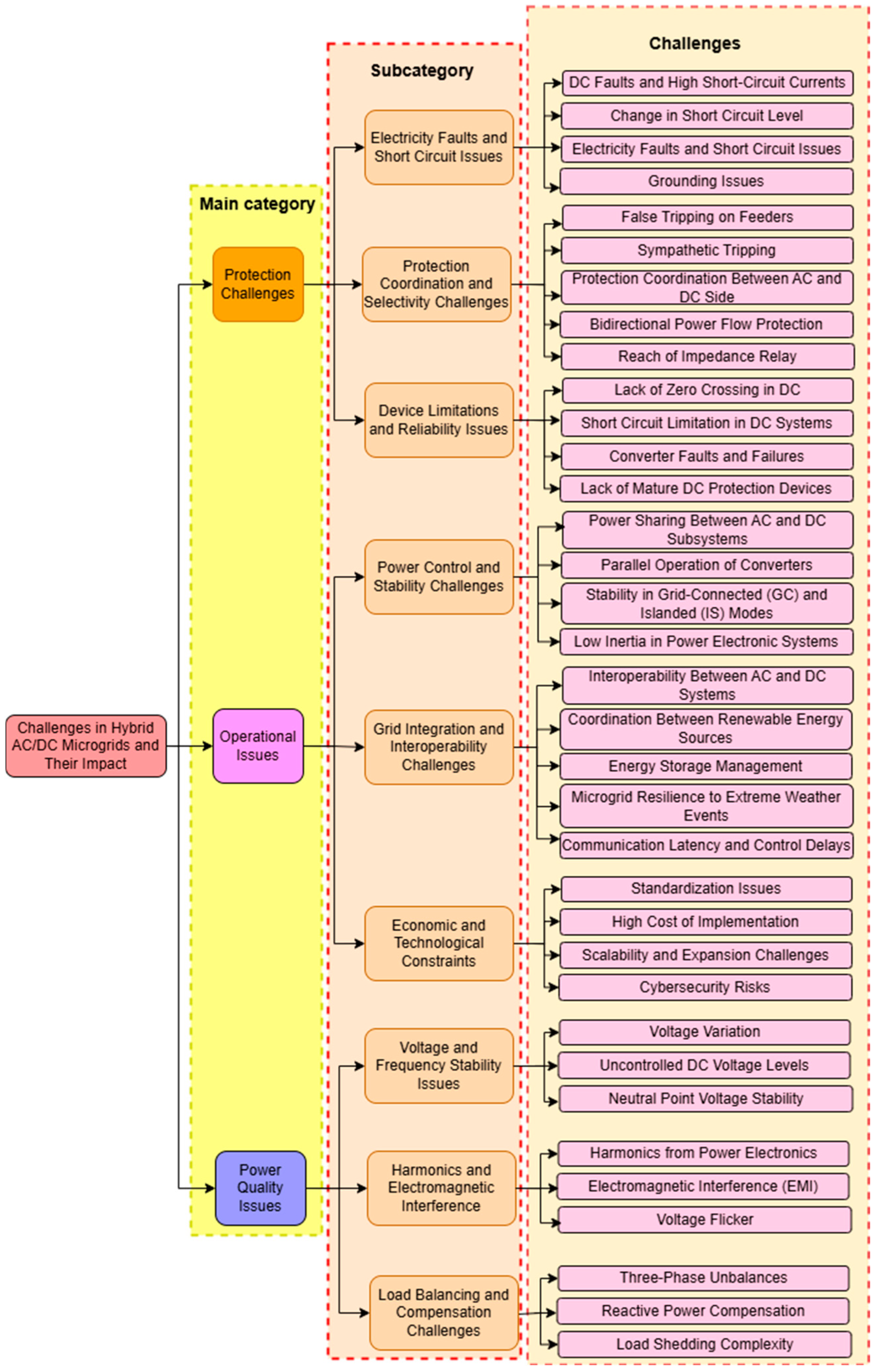

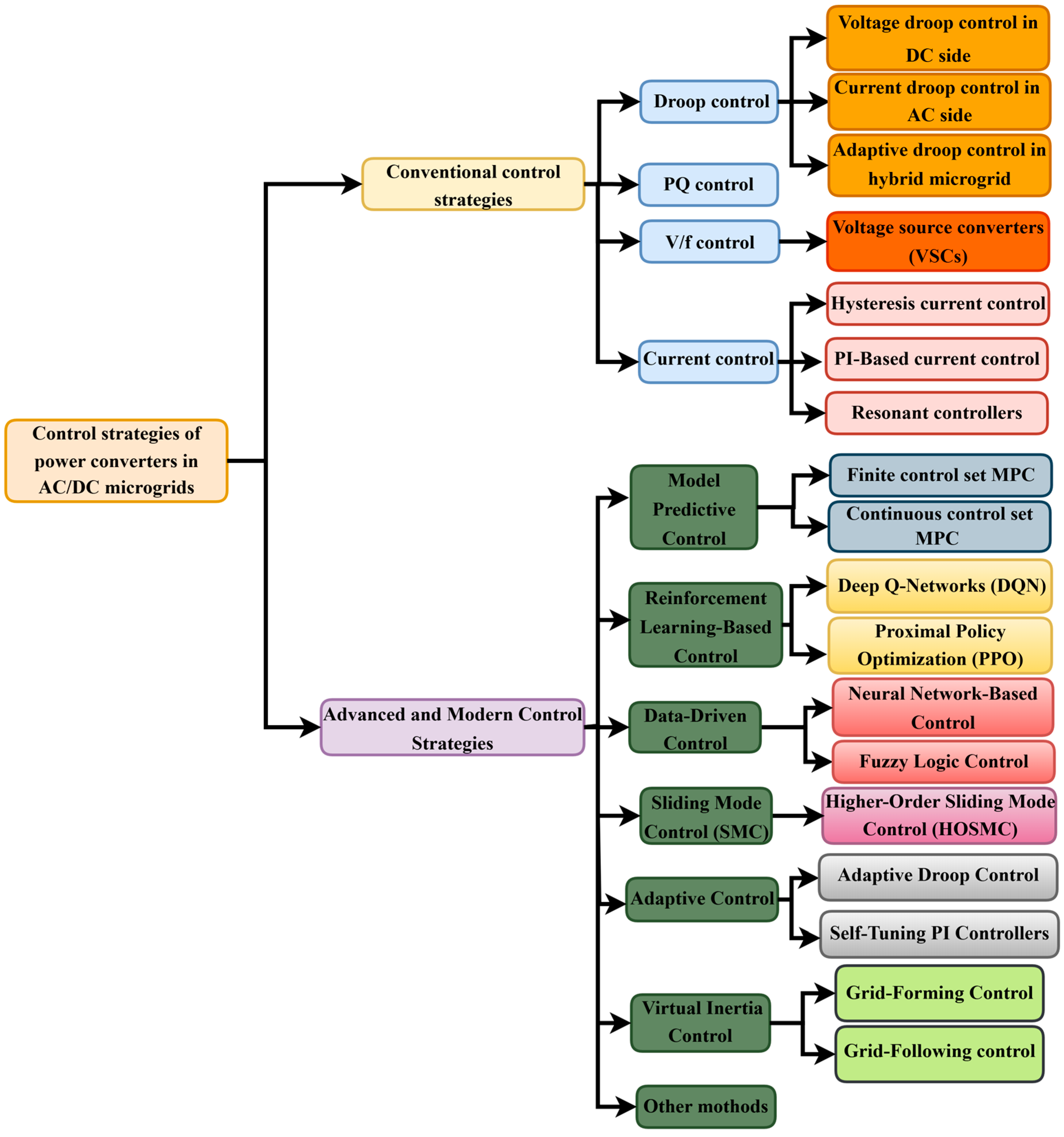

3. Control Strategies for Power Converters in AC/DC MGs

3.1. Hierarchical Control Architecture and Resiliency

- Primary (Local) Control: Operating at millisecond scale, it handles inner current loops, voltage/frequency formation and stabilization, and fast transients. At this layer, converters are categorized by function:

- GF set V/f references

- GFL inject current to track the grid

- IPCs manage bidirectional AC/DC power exchange

- Secondary and Tertiary Control: Running at seconds–minutes, these layers use communication (for instance, IEC 61850 [89], TCP/IP) to restore nominal V/f (secondary) and execute optimal power flow and economic dispatch (tertiary).

3.2. Conventional Limitations and the Need for Virtualization

3.2.1. Limitations of Classical Droop Control

3.2.2. Adaptive and Virtualization Techniques

- Adaptive Droop Control: This technique dynamically adjusts droop coefficients based on real-time system states (for instance, voltage deviation), overcoming the static nature of classical droop. Adaptive methods demonstrate significant improvements in current and power sharing accuracy, stability margins, and faster transient response times compared to static methods [96].

- Virtual Impedance: The most direct solution to impedance mismatch is the Adaptive Virtual Impedance Droop Control (AVIDC). This mechanism dynamically introduces a synthetic (usually inductive) impedance into the control loop. This action effectively decouples and control, ensuring accurate reactive power sharing by balancing the converter’s output with the virtual line drop [97].

- Virtual Inertia Control (VIC): To enhance damping and mitigate rapid frequency deviations, the Virtual Synchronous Machine (VSM) or Virtual Synchronous Generator (VSG) is implemented in GFCs and IPCs. VSM algorithms digitally emulate the mechanical inertia of traditional generators, providing active support to the AC bus frequency and DC bus voltage stability.

3.3. Modern Predictive and Optimized Control

3.3.1. Model Predictive Control (MPC)

- Performance: MPC, particularly Finite Control Set MPC (FCS-MPC), demonstrates improved transient and steady-state voltage/frequency responses, along with reduced Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) compared to conventional methods [98].

- Limitation: MPC’s main barrier to widespread scalability is its high online computational burden, which often involves solving complex mixed-integer linear/quadratic programs (MILP/MIQP) in real-time.

3.3.2. Data-Driven and Hybrid Learning

3.4. Robust Control and Resilience

- Robust non-linear control: Methodologies like control mathematically guarantee performance by minimizing the maximum possible effect of disturbances, a critical requirement for coordinating complex IPCs under uncertainty [101]. Passivity-Based Control (PBC) ensures stability by leveraging the inherent energy conservation properties of the physical system.

- Sliding mode observer (SMO) for fault-tolerance: A key resilience application is integrating observers into the secondary control layer. A Sliding Mode Observer (SMO) can accurately reconstruct sensor or actuator faults (for instance, magnitude or harmonics) in real-time, functioning as a diagnostic tool. This Fault-Tolerant Control (FTC) architecture uses the reconstructed fault value to actively offset the influence of the fault, ensuring the system maintains operational performance, restores voltage, and maintains proportional current sharing even when components or communication links are compromised [92].

3.5. Specialized Interlinking Converter (IPC) Control

- Coordinated control and mitigation: IPCs must manage smooth, bidirectional power transfer and seamless mode transition between grid-tied and islanded operation (for instance, rapid islanded detection within 1.5 cycles). Research has developed solutions for highly coordinated systems, such as employing a superimposed frequency on the DC sub-grid to achieve autonomous, proportional power sharing in systems with multiple IPCs, effectively mitigating circulating power flows caused by line resistance [95].

- Power quality: IPC control also integrates selective controllers (for instance, Multi-resonant, Repetitive Controllers) with primary control to actively track and eliminate harmonic distortions (documented THD reduction from 12.10% to 3.51%), ensuring the entire system meets power quality standards.

3.6. Quantitative Synthesis of Performance

4. Converters for Low Voltage (LV) and Medium Voltage (MV) Applications

4.1. Case Studies in Application

4.1.1. LV Residential PV Micro Inverter

4.1.2. MV Converter for Offshore Wind Farm Collection

5. Fault Behavior and Advanced Protection Schemes

5.1. Fault Characteristics in HMGs

5.1.1. Classification of Fault Types

- Pole-to-Pole (PP) Faults: A pole-to-pole fault is a low-impedance, or bolted, short circuit that occurs directly between the positive and negative DC conductors. This is the most severe type of DC fault. Upon fault inception, the large DC-link capacitors associated with the power converters discharge rapidly and uncontrollably into the fault path. This results in an extremely high-current surge with a very steep rate of rise , capable of causing catastrophic damage to semiconductor devices within microseconds if not interrupted swiftly [130].

- Pole-to-Ground (PG) Faults: A pole-to-ground fault occurs when either the positive or the negative conductor makes an unintended connection to the system ground. These faults are typically of higher impedance than PP faults, as the fault path may include resistive elements. While the resulting fault current is generally lower, PG faults can be more difficult to detect, particularly in ungrounded or high-resistance grounded systems [131]. The ability to detect these faults is critical for personnel safety and to prevent the evolution of a PG fault into a more severe PP fault.

5.1.2. Inherent Converter Fault Response

- Voltage Source Converters (VSCs): VSCs, which are ubiquitous in modern Mgs due to their flexible control capabilities, are exceptionally vulnerable to DC faults. A VSC topology includes a large DC-link capacitor bank and uses switches (like IGBTs) with anti-parallel diodes. During a DC-side fault, even if the IGBTs are immediately turned off, the fault creates a direct path for the DC-link capacitors to discharge through the anti-parallel diodes of the converter bridge [130]. This process is completely uncontrolled, leading to a massive current spike that can easily exceed the surge current rating of the diodes, causing their destruction. The fault current rises extremely rapidly, driven by the low impedance of the capacitor discharge path [132]. This makes the protection of VSCs one of the most critical challenges in DC MG design.

- Current Source Converters (CSCs): In contrast, CSCs are inherently more robust to DC faults. The defining feature of a CSC is the large DC-link inductor connected in series with the DC source. This inductor serves to maintain a relatively constant DC current. During a fault, this inductor naturally opposes any rapid change in current, thereby significantly limiting the rate of rise of the fault current [132]. This inherent current-limiting behavior provides a crucial time window, typically milliseconds instead of microseconds for the protection system to detect the fault and actuate a breaker, preventing the fault current from reaching destructive levels. This characteristic makes CSCs a more fault-tolerant option, though they are often less flexible in control and have higher conduction losses compared to VSCs.

5.2. Advanced Protection Devices and Control Actions

5.2.1. The Rise of Solid-State Circuit Breakers (SSCBs)

5.2.2. Control Actions from Protection to Resilience

6. Discussion

- Virtual Inertia: The inherent lack of mechanical inertia in converter-dominated grids is a primary source of frequency instability. The implementation of VSM or VIC in grid-forming and interlinking converters is a direct software-based solution, synthesizing the stabilizing properties of a rotating mass where none physically exists.

- Virtual Impedance: Classical droop control, while appealing for its autonomy, fundamentally fails in the resistive LV/MV lines common in HMGs, leading to power-sharing inaccuracies. AVIDC acts as a software-based fix, digitally reshaping the converter’s perceived output impedance to effectively decouple active and reactive power control and force the system to behave as the classical inductive model predicts.

- The Computational Barrier: The superior performance of MPC is consistently hampered by its high computational burden, which is often untenable for the microsecond-level execution required for converter switching. The true research gap is not just faster algorithms, but the co-design of control algorithms and dedicated hardware accelerators (for instance, FPGAs, Systems-on-a-Chip) to make real-time optimization viable at the speed of power electronics.

- The Economic Barrier: The proliferation of advanced hardware (MMCs, SiC devices, SSCBs) identified in Section 3 and Section 5 creates a significant economic barrier to entry. The field urgently requires the development of robust techno-economic models and lifecycle cost analyses to quantify the long-term operational benefits (for example, higher efficiency, reduced downtime, ancillary service revenue) against the immediate capital expenditure (CAPEX), thereby justifying their adoption.

- The Standardization Barrier: The very success of proprietary virtual controls (VSM, AVIDC) creates a new, pressing challenge interoperability. As different vendors implement their own virtual inertia algorithms, the risk of negative control interactions and system-wide instability in multi-vendor HMGs becomes significant. A critical future direction is the development of new industry standards (akin to IEEE 1547) to define the external behavior and communication protocols of these virtualized functions, ensuring plug-and-play stability and moving the field from bespoke projects to a standardized, scalable industry.

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

- The software-defined hardware paradigm, where virtualization techniques like VSM and AVIDC are essential for stability

- The fundamental design bifurcation between LV (cost/density-driven) and MV (reliability-driven) applications

- The non-negotiable, synergistic pairing of ultra-fast hardware protection SSCBs for survivability with advanced software FRT for resilience.

- Research Direction 1: The Computational Frontier

- Research Direction 2: The Economic Frontier

- Research Direction 3: The Standardization Frontier

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HMGs | Hybrid AC/DC microgrids |

| LV | Low voltage |

| MV | Medium voltage |

| GaN | Gallium Nitride |

| SiC | Silicon carbide |

| VIC | Virtual inertia control |

| AVIDC | Adaptive virtual impedance control |

| SSCBs | Solid-state circuit breakers |

| VSCs | Voltage source converters |

| FRT | Fault ride-through |

| DGs | Distributed energy generators |

| RESs | Renewable energy sources |

| MGs | Microgrids |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| EVs | Electric vehicles |

| ESS | Energy storage systems |

| GFPC | Grid-forming power converter |

| GFLPC | Grid-following power converter |

| GSPC | Grid-supporting power converter |

| IPC | Interlinking power converter |

| IS | Islanded |

| GC | Grid connected |

| CSCs | Current source converters |

| 3RC | Multi-resonant controller |

| RC | Repetitive controller |

| MCUs | Microcontrollers |

| DSPs | Digital signal processors |

| PLL | Phase locked loop |

| BIC | Bidirectional interface converter |

| VSG | Virtual synchronous generator |

| VSI | Voltage source inverter |

| SIN | Symmetrical impedance network |

| LBTLC | Large-bandwidth triple-loop control |

| LVRT | Low-voltage ride-through |

| PBC | Passivity-based control |

| VSM | Virtual synchronous machine |

| OPF | Optimal power flow |

| HIL | Hardware-in-the-Loop |

| APF | Active power filtering |

| RTDS | Real-time digital simulator |

| MLCs | Multilevel converters |

| NPC | Neutral point clamped |

| FC | Flying capacitor |

| FCDO | Flying capacitor dual output |

| CHB | Cascaded H-Bridge |

| MMCs | Modular multilevel converters |

| 2-DOF | Two-degree-of-freedom |

| PSO | Particle swarm optimization |

| MVDC | Medium-voltage DC |

| HVDC | High-voltage DC |

| SEPIC | Single-ended primary-inductor converter |

| PWM | Pulse width modulation |

| DQN | Deep–Q network |

| FDI | False data injection |

| MPC | Model predictive control |

| FCS-MPC | Finite control Set MPC |

| THD | Total harmonic distortion |

| MILP | Mixed-integer linear program |

| PPO | Proximal policy optimization |

| HOSMC | Higher-order sliding mode control |

| SMC | Sliding mode control |

| RL | Reinforcement learning |

| SMO | Sliding mode observer |

| FTC | Fault-Tolerant control |

| KPIs | Key performance indicators |

| UPS | Uninterruptible power supplies |

| EVCs | Electric vehicle charging stations |

| BESS | Battery energy storage systems |

| IEC | International electro technical commission |

| ANSI | American national standards institute |

| MCCBs | Molded case circuit breakers |

| MCBs | Miniature circuit breakers |

| WBG | Wide bandgap |

| MLPE | Module-level power electronics |

| MPPT | Maximum power point tracking |

| PR | Performance ratio |

| IGCTs | Integrated gate-commutated Thyristors |

| PP | Pole-to-Pole |

| PG | Pole-to-Ground |

| CAPEX | Capital expenditure |

Appendix A

| Performance Comparison of Power Converter Types Under Dynamic Operating Conditions | |||||

| Converter Type | Ref. | Performance in Load Changes | Performance Under Distribution | Harmonic Mitigation | Voltage Stability |

| Current Source Converter (CSC) | [46] | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| [48] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [49] | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | |

| Voltage Source Converter (VSC) | [50] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [51] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [52] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [53] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| [54] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| [55] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| Boost Converter | [56] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| [57] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [58] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| Bidirectional DC-DC Converter | [59] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| [60] | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | |

| [61] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [62] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [63] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [64] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [65] | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | |

| Neutral Point Clamped (NPC) Converter | [66] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [67] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| [68] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| [42] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| [41] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| [69] | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | |

| Flying Capacitor (FC) Converter | [70] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| [71] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [72] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [73] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [74] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [75] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| Cascaded H-Bridge (CHB) Converter | [76] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| [77] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [78] | Yes | N/A | N/A | Yes | |

| [79] | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | |

| [80] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| [81] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Modular Multilevel Converter (MMC) | [82] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [83] | N/A | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [84] | Yes | N/A | Yes | Yes | |

| [85] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| [86] | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes | |

| [87] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Operational Capabilities, Fault Tolerance, and Key Functional Features of Power Converter Types | |||||

| Converter Type | Ref. | Bidirectional Capability | Fault Tolerance | Sim. Or Exp. | Key Features |

| Current Source Converter (CSC) | [46] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

|

| [48] | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [49] | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| |

| Voltage Source Converter (VSC) | [50] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

|

| [51] | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [52] | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| |

| [53] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [54] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| |

| [55] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| |

| Boost Converter | [56] | Yes | N/A | Yes |

|

| [57] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [58] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| |

| Bidirectional DC-DC Converter | [59] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

|

| [60] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [61] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [62] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [63] | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| |

| [64] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [65] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| |

| Neutral Point Clamped (NPC) Converter | [66] | N/A | Yes | Yes |

|

| [67] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| |

| [68] | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| |

| [42] | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| |

| [41] | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| |

| [69] | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| |

| Flying Capacitor (FC) Converter | [70] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

|

| [71] | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| |

| [72] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [73] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| |

| [74] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| |

| [75] | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| |

| Cascaded H-Bridge (CHB) Converter | [76] | Yes | N/A | Yes |

|

| [77] | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [78] | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [79] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [80] | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [81] | N/A | Yes | Yes |

| |

| Modular Multilevel Converter (MMC) | [82] | Yes | N/A | Yes |

|

| [83] | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [84] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| |

| [85] | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| |

| [86] | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| |

| [87] | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| |

References

- Dalei, N.N.; Gupta, A. Adoption of Renewable Energy to Phase down Fossil Fuel Energy Consumption and Mitigate Territorial Emissions: Evidence from BRICS Group Countries Using Panel FGLS and Panel GEE Models. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomin, N.; Kurbatsky, V.; Panasetsky, D.; Sidorov, D.; Zhukov, A. Voltage/VAR Control and Optimization: AI Approach. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibi, S.; Rahimi, R.; Shamsi, P.; Ferdowsi, M. Efficiency Assessment of a Residential DC Nanogrid with Low and High Distribution Voltages Using Realistic Data. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Green Technologies Conference (GreenTech), Denver, CO, USA, 7–9 April 2021; pp. 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok Kumar, A.; Amutha Prabha, N. A Comprehensive Review of DC Microgrid in Market Segments and Control Technique. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moh, M.G. An Overview of AC and DC Microgrid Energy Management Systems. AIMS Energy 2023, 11, 1031–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unamuno, E.; Barrena, J.A. Hybrid Ac/Dc Microgrids—Part I: Review and Classification of Topologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 1251–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eajal, A.A.; Muda, H.; Aderibole, A.; Al Hosani, M.; Zeineldin, H.; El-Saadany, E.F. Stability Evaluation of AC/DC Hybrid Microgrids Considering Bidirectional Power Flow through the Interlinking Converters. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 43876–43888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwani, M.I.; Elmezain, M.I. A comprehensive review of hybrid AC/DC networks: Insights into system planning, energy management, control, and protection. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 17961–17977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.M.; Vasquez, J.C.; Matas, J.; de Vicuna, L.G.; Castilla, M. Hierarchical control of droop-controlled AC and DC microgrids—A general approach toward standardization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2010, 58, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.Y.A.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Hybrid AC/DC microgrid: Systematic evaluation of interlinking converters, control strategies, and protection schemes: A review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 160097–160132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirsaeidi, S.; Dong, X.; Shi, S.; Tzelepis, D. Challenges, advances and future directions in protection of hybrid AC/DC microgrids. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2017, 11, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buraimoh, E.; Aluko, A.O.; Oni, O.E.; Davidson, I.E. Decentralized virtual impedance-conventional droop control for power sharing for inverter-based distributed energy resources of a microgrid. Energies 2022, 15, 4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakeer, A.; Chub, A.; Abid, A.; Zaid, S.A.; Alghamdi, T.A.H.; Salama, H.S. Enhancing grid-forming converters control in hybrid AC/DC microgrids using bidirectional virtual inertia support. Processes 2024, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajube, A.; Omiloli, K.; Vedula, S.; Anubi, O.M. Decentralized Droop-based Finite-Control-Set Model Predictive Control of Inverter-based Resources in Islanded AC Microgrid. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2024, 58, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalla, S.; Ernst, P.; Lens, H.; Schaupp, T.; Schöll, C.; Singer, R.; Ungerland, J. Grid-forming converters in interconnected power systems: Requirements, testing aspects, and system impact. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2024, 18, 3053–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarrah, R.; Fawaz, B.B.; Salem, Q.; Karimi, M.; Marzooghi, H.; Azizipanah-Abarghooee, R. Issues and challenges of grid-following converters interfacing renewable energy sources in low inertia systems: A review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 5534–5561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmal, C.; Zhang, Z.; Renner, H.; Schürhuber, R. Enhancing Stability of Grid-Supporting Inverters from an Analytical Point of View with Lessons from Microgrids. Energies 2023, 16, 8054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Deng, C.; Li, G. Control Strategy of Interlinking Converter in Hybrid Microgrid Based on Line Impedance Estimation. Energies 2022, 15, 1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.; Barakati, S.M. Interlinking converter of hybrid AC/DC microgrid as an active power filter. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Renewable Energy and Power Engineering (REPE), Toronto, ON, Canada, 2–4 November 2019; pp. 95–99. [Google Scholar]

- Phan, D.-M.; Lee, H.-H. Interlinking converter to improve power quality in hybrid AC–DC microgrids with nonlinear loads. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2018, 7, 1959–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Narasimharaju, B.; Kumar, N.R. Performance analysis of AC-DC power converter using PWM techniques. Energy Procedia 2012, 14, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodwong, B.; Guilbert, D.; Phattanasak, M.; Kaewmanee, W.; Hinaje, M.; Vitale, G. AC-DC converters for electrolyzer applications: State of the art and future challenges. Electronics 2020, 9, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvi, M.; Zohdi, H.Z. A comprehensive overview of DC-DC converters control methods and topologies in DC microgrids. Energy Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 2017–2036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solsona, J.A.; Gomez Jorge, S.; Busada, C.A. Modeling and nonlinear control of DC–DC converters for microgrid applications. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahesh, G.S.; Puskar, A.; Krishna, P.M.; Rajashekhar, S. Energy management with bi-directional converters in DC microgrids. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1473, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Su, C.Y. Data-Driven Control for Three-Phase AC–DC Power Converters Modeled by Switched Affine Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 11875–11884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaabjerg, F.; Teodorescu, R.; Liserre, M.; Timbus, A.V. Overview of control and grid synchronization for distributed power generation systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2006, 53, 1398–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brahmi, H.; Dhifaoui, R. A study of a DC/AC conversion structure for photovoltaic system connected to the grid with active and reactive power control. Complexity 2021, 2021, 9967577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Sun, X.; Sun, Y.; Shi, K.; Xu, P. A virtual inertial control strategy for bidirectional interface converters in hybrid microgrid. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 153, 109388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Blaabjerg, F. An interlinking converter for renewable energy integration into hybrid grids. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 36, 2499–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Caldognetto, T.; Buso, S. Flexible control of interlinking converters for DC microgrids coupled to smart AC power systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 66, 3477–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.D.; Lestas, I. Control of interlinking converters in hybrid AC/DC grids: Network stability and scalability. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 36, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsiraji, H.A.; ElShatshat, R.; Radwan, A.A. A novel control strategy for the interlinking converter in hybrid microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting, Chicago, IL, USA, 16–20 July 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Pullaguram, D.; Madani, R.; Altun, T.; Davoudi, A. Optimal power flow in AC/DC microgrids with enhanced interlinking converter modeling. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Ind. Electron. 2022, 3, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-W.; Moon, S.-I.; Lee, G.-S.; Hwang, P.-I. A new local control method of interlinking converters to improve global power sharing in an islanded hybrid AC/DC microgrid. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2020, 35, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharizadeh, M.; Karshenas, H.R.; Esfahani, M.S.G. Control method for improvement of power quality in single interlinking converter hybrid AC-DC microgrids. IET Smart Grid 2021, 4, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.; Bai, Y.; Xu, P.; Sun, Y. Dual-side virtual inertia control for stability enhancement in islanded AC-DC hybrid microgrids. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2025, 241, 111396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shravan, R.; Vyjayanthi, C. Active power filtering using interlinking converter in droop controlled islanded hybrid AC-DC microgrid. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2020, 30, e12333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahrabi, R.R.; Li, Y.W.; Nejabatkhah, F. Hybrid AC/DC network with parallel LCC-VSC interlinking converters. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 36, 722–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, B.P.; Selvakumar, A.I.; Mathew, F.M. Integrating multilevel converters application on renewable energy sources—A survey. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2018, 10, 065502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, J.D.; Rocha, L.; Silva, J.F. Backstepping predictive control of hybrid microgrids interconnected by neutral point clamped converters. Electronics 2021, 10, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, J.D.; Rocha, L.; Silva, J.F. Backstepping control of NPC multilevel converter interfacing AC and DC microgrids. Energies 2023, 16, 5515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, C.; Padmanaban, S.; Zbigniew, L. Multiple modulation strategy of flying capacitor DC/DC converter. Electronics 2019, 8, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayan, V.; Ghias, A.M.Y.M. Computationally-efficient model predictive control of dual-output multilevel converter in hybrid microgrid. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 5898–5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, O.; Sanchis, P.; Gubia, E.; Marroyo, L. Cascaded H-bridge multilevel converter for grid connected photovoltaic generators with independent maximum power point tracking of each solar array. In Proceedings of the IEEE 34th Annual Conference on Power Electronics Specialist (PESC’03), Acapulco, Mexico, 15–19 June 2003; Volume 2, pp. 731–735. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, S.; Darwish, A. Modular multilevel converters for large-scale grid-connected photovoltaic systems: A review. Energies 2021, 14, 6213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.P.F.; Rodrigues, A.; Pedrosa, D.; Afonso, J.L.; Monteiro, V.D.F. A current-source converter with a hybrid dc-dc converter interfacing an electric vehicle and a renewable energy source. EAI Endorsed Trans. Energy Web 2023, 9, e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, A.; Khouri, I.; Jiang, X. Modeling and control of current-source converter-based AC microgrids. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 8th International Conference on Smart Energy Grid Engineering (SEGE), Oshawa, ON, Canada, 12–14 August 2020; pp. 97–101. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Tu, R.; Wang, K.; Lei, J.; Wang, W.; Feng, S.; Wei, C. A hybrid predictive control for a current source converter in an aircraft DC microgrid. Energies 2019, 12, 4025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhasnawi, B.N.; Jasim, B.H.; Issa, W.; Esteban, M.D. A novel cooperative controller for inverters of smart hybrid AC/DC microgrids. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Meegahapola, L.; Datta, M.; Vahidnia, A. A novel hybrid AC/DC microgrid architecture with a central energy storage system. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 37, 2060–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Gao, F.; Liao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D. Distributed AC–DC coupled hierarchical control for VSC-based DC microgrids. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 39, 2180–2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachichi, A.; Green, A.J.-F.T. Power converters design for hybrid LV ac/dc microgrids. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 6th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), San Diego, CA, USA, 5–8 November 2017; pp. 850–854. [Google Scholar]

- Davari, M.; Mohamed, Y.A.-R.I. Robust multi-objective control of VSC-based DC-voltage power port in hybrid AC/DC multi-terminal micro-grids. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2013, 4, 1597–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, F.; Ashfaq, M.; Zaidi, S.S.; Memon, A.Y. Robust droop control design for a hybrid AC/DC microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2016 UKACC 11th International Conference on Control (CONTROL), Belfast, UK, 31 August–2 September 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Alharbi, Y.; Badawy, A.D.; Ma, X. A Hybrid Controller for Novel Cascaded DC-DC Boost Converters in Residential DC Microgrids. In Proceedings of the 2024 29th International Conference on Automation and Computing (ICAC), Sunderland, UK, 28–30 August 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Samanta, H.; Pramanik, M.; Das, A.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Das Bhattacharya, K.; Deb, N.K.; Sengupta, S.; Saha, H. Development of a novel controller for DC-DC boost converter for DC Microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), Kochi, India, 17–20 October 2019; pp. 1124–1129. [Google Scholar]

- Barui, T.; Goswami, S.; Mondal, D. Design of digitally controlled DC-DC boost converter for the operation in DC microgrid. J. Eng. Sci. 2020, 7, E7–E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemakesavulu, O.; Lalitha, M.P.; Reddy, L.B.; Harshitha, S. Design and Implementation of a Hybrid AC-DC Micro Grid for Voltage and Frequency Stabilization by using Advanced Control Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 12th International Conference on Smart Grid (icSmartGrid), Setúbal, Portugal, 27–29 May 2024; pp. 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Kulasekaran, P.S.; Dasarathan, S. Design and analysis of interleaved high-gain bi-directional DC–DC converter for microgrid application integrated with photovoltaic systems. Energies 2023, 16, 5135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarzi, M.D.; Ali, M.H. A novel bidirectional dc-dc converter for dynamic performance enhancement of hybrid AC/DC microgrid. Electronics 2020, 9, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, R.; Rani, P.U. Bidirectional DC-DC converter for microgrid in energy management system. Int. J. Electron. 2021, 108, 322–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimitti, F.G.; Andrade, A.M.S.S. Bidirectional converter based on boost/buck DC-DC converter for microgrids energy storage systems interface. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2022, 50, 4376–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeggegn, D.B.; Nyakoe, G.N.; Wekesa, C. ANFIS-Controlled Boost and Bidirectional Buck-Boost DC-DC Converters for Solar PV, Fuel Cell, and BESS-Based Microgrid Application. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2024, 2024, 6484369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Wu, W.; Chen, Z.; Orabi, M. A new buck-boost AC/DC converter with two switches for DC microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 2nd International Power Electronics and Application Symposium (PEAS), Guangzhou, China, 10–13 November 2023; pp. 1038–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Tian, H.; Ding, L.; Wu, X.; Kish, G.J.; Li, Y.R. An improved three-level neutral point clamped converter system with full-voltage balancing capability for bipolar low-voltage DC Grid. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 15792–15803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, H.-S.; Baek, J.-W.; Jeong, D.-K. Analysis of effective three-level neutral point clamped converter system for the bipolar LVDC distribution. Electronics 2019, 8, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, J.D.; Silva, J.F.A.; Rocha, L. New backstepping controllers with enhanced stability for neutral point clamped converters interfacing photovoltaics and AC microgrids. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 153, 109332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, J.; Karshenas, H.; Eren, S.; Bakhshai, A. An optimized capacitor voltage balancing control for a five-level nested neutral point clamped converter. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 36, 2154–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, H.M.; Dash, S.K. Renewable energy-based DC microgrid with hybrid energy management system supporting electric vehicle charging system. Systems 2023, 11, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayan, V.; Ghias, A.M.Y.M. A single-objective modulated model predictive control for a multilevel flying-capacitor converter in a DC microgrid. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 37, 1560–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayan, V.; Ghias, A.; Merabet, A. Modeling and Control of Three-level Bi-directional Flying Capacitor DC-DC converter in DC microgrid. In Proceedings of the IECON 2019—45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 October 2019; Volume 1, pp. 4113–4118. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Dong, D. A flying capacitor hybrid modular multilevel converter with reduced number of submodules and power losses. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 70, 3293–3302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.W. A new current source converter using AC-type flying-capacitor technique. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 10307–10316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, K.; Lv, H.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, W.; Fan, Q. A model predictive controlled bidirectional four quadrant flying capacitor DC/DC converter applied in energy storage system. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 7705–7717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavanya, G.L.; Devi, P.P. Design and Implementation of Three-Terminal and Five-Terminal Hybrid AC/DC Micro Grid with an Improved Grid Current and DC Capacitor Voltage Balancing Method. Available online: https://ijaem.net/issue_dcp/Design%20and%20Implementation%20of%20Three-Terminal%20and%20FiveTerminal%20Hybrid%20AC%20DC%20Micro%20Grid%20with%20an%20Improved%20Grid%20Current%20and%20DC%20Capacitor%20Voltage%20Balancing%20Method.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Jia, H.; Xiao, Q.; He, J. An improved grid current and DC capacitor voltage balancing method for three-terminal hybrid AC/DC microgrid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2018, 10, 5876–5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavilapalli, S.; Umashankar, S.; Sanjeevikumar, P.; Fedák, V.; Mihet-Popa, L.; Ramachandaramurthy, V.K. A buck-chopper based energy storage system for the cascaded H-bridge inverters in PV applications. Energy Procedia 2018, 145, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, R.; John, R.V.; Kumar, M. Cascaded H-Bridge Multilevel Inverter Based Solar PV Power Conversion System. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Students Conference on Engineering and Systems (SCES), Prayagraj, India, 1–3 July 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chindamani, M.; Ravichandran, C. A hybrid DDAO-RBFNN strategy for fault tolerant operation in fifteen-level cascaded H-bridge (15L-CHB) inverter with solar photovoltaic (SPV) system. Sol. Energy 2022, 244, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, H.; Hatua, K.; Bhattacharya, S. Hybrid Modulation Technique of MV Grid Connected Cascaded H-Bridge based Power Electronic Transformer Technology. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 2864–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kish, G.J. On the emerging class of non-isolated modular multilevel DC–DC converters for DC and hybrid AC–DC systems. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 10, 1762–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motwani, J.K.; Liu, J.; Burgos, R.; Zhou, Z.; Dong, D. Hybrid modular multilevel converters for high-AC/low-DC medium-voltage applications. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2023, 4, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Huang, W.; Tai, N.; Liang, S. A novel design of architecture and control for multiple microgrids with hybrid AC/DC connection. Appl. Energy 2018, 210, 1002–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandla, K.C.; Padhy, N.P. A Multilevel Dual Converter fed Open end Transformer Configuration for Hybrid AC-DC Microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Portland, OR, USA, 5–10 August 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Castelli Dezza, F.; Toscani, N.; Benvenuti, M.; Tagliaretti, R.; Agnetta, V.; Amatruda, M.; De Maria, S. Design and Simulation of a Novel Modular Converter-Transformer for AC/DC, DC/AC and DC/DC Operations. Energies 2024, 17, 6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.; Mu, Y.; Jia, H.; Jin, Y.; Hou, K.; Yu, X.; Teodorescu, R.; Guerrero, J.M. Modular multilevel converter based multi-terminal hybrid AC/DC microgrid with improved energy control method. Appl. Energy 2021, 282, 116154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulou, M.; Rakopoulos, D.; Trigkas, D.; Stergiopoulos, F.; Blanas, O.; Voutetakis, S. State of the art of low and medium voltage direct current (Dc) microgrids. Energies 2021, 14, 5595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61850; Communication Networks and Systems for Power Utility Automation. TC57, International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Liu, Y.; Du, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhan, H. Resilient distributed control of islanded microgrids under hybrid attacks. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1320968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, E.D.; Gonzalez, J.F.; Teeuw, W.B. Enhancing cybersecurity in distributed microgrids: A review of communication protocols and standards. Sensors 2024, 24, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, M. Multiple Fault-Tolerant Control of DC Microgrids Based on Sliding Mode Observer. Electronics 2025, 14, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Yin, X.; Chung, C.Y.; Rayeem, S.K.; Chen, X.; Yang, H. Managing Massive RES Integration in Hybrid Microgrids: A Data-Driven Quad-Level Approach With Adjustable Conservativeness. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 7698–7709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, T.; Cheng, Z.; Hu, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Huang, J.; Hou, X. A unified droop control of ac microgrids under different line impedances: Revisiting droop control and virtual impedance method. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1190833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyghami, S.; Mokhtari, H.; Blaabjerg, F. Autonomous operation of a hybrid AC/DC microgrid with multiple interlinking converters. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 9, 6480–6488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammad Saeed, M.; Iqbal, S.; Sohail, M.; Akram, U. An optimal adaptive control of DC-Microgrid with the aim of accurate current sharing and voltage regulation according to the load variation and gray-wolf optimization. Adv. Eng. Intell. Syst. 2023, 2, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Sun, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Guo, L.; Zhou, G.; Lyu, H. Adaptive Virtual Impedance Droop Control of Parallel Inverters for Islanded Microgrids. Sensors 2025, 25, 5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, A.; Yusupov, Z. Real-Time Capable MPC-Based Energy Management of Hybrid Microgrid. Processes 2025, 13, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, S.; Lei, Y.; Chong, A. Comparing model predictive control and reinforcement learning for the optimal operation of building-PV-battery systems. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 396, 04018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.F.O.; Dabiri, A.; De Schutter, B. Integrating reinforcement learning and model predictive control with applications to microgrids. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.11267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvizi, P.; Amidi, A.M.; Zangeneh, M.R.; Riba, J.R.; Jalilian, M. A Taxonomy of Robust Control Techniques for Hybrid AC/DC Microgrids: A Review. Eng 2025, 6, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.B.; Ismail, A.A.A.; Elnady, A.; Farag, M.M.; Hamid, A.K.; Bansal, R.C.; Abo-Khalil, A.G. Modular multilevel converter-based microgrid: A critical review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 65569–65589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, N.; Strickland, D. Control of cascaded DC–DC converter-based hybrid battery energy storage systems—Part I: Stability issue. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2015, 63, 2340–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavon, W.; Inga, E.; Simani, S.; Armstrong, M. Optimal Hierarchical Control for Smart Grid Inverters Using Stability Margin Evaluating Transient Voltage for Photovoltaic System. Energies 2023, 16, 2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goud, B.S.; Kalyan, C.N.S.; Rao, G.S.; Mohapatra, B.; Kuppireddy, N.R.; Pulluri, H.; Reddy, C.R.; Shorfuzzaman, M.; Abu Zneid, B.; Pushkarna, M. GRU controller-based UPQC compensator design for improving power quality in grid-integrated non-linear load system. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaram, J.; Srinivasan, M.; Prabaharan, N.; Senjyu, T. Design of decentralized hybrid microgrid integrating multiple renewable energy sources with power quality improvement. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, R.A. Power Electronics Solutions and Architectures for Industrial and High-Power Applications. Doctor Thesis, Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna, Bologna, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, R.; Rafin, S.S.H.; Mohammed, O.A. Comprehensive review of power electronic converters in electric vehicle applications. Forecasting 2022, 5, 22–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korompili, A.; Monti, A. Review of modern control technologies for voltage regulation in DC/DC converters of DC microgrids. Energies 2023, 16, 4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, G.; Alsokhiry, F.; Al-Turki, Y.; Ajangnay, M.; Amogpai, A. DC-DC Converters for Medium and High Voltage Applications. In Proceedings of the IECON 2019—45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 October 2019; Volume 1, pp. 3337–3342. [Google Scholar]

- Sutikno, T.; Aprilianto, R.A.; Purnama, H.S. Application of non-isolated bidirectional DC–DC converters for renewable and sustainable energy systems: A review. Clean Energy 2023, 7, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, T.; Maklakov, A.S. A review of voltage source converters for energy applications. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Ural Conference on Green Energy (UralCon), Chelyabinsk, Russia, 4–6 October 2018; pp. 275–281. [Google Scholar]

- Migliazza, G.; Buticchi, G.; Carfagna, E.; Lorenzani, E.; Madonna, V.; Giangrande, P.; Galea, M. DC current control for a single-stage current source inverter in motor drive application. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 36, 3367–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.A.; Ceballos, S.; Konstantinou, G.; Pou, J.; Aguilera, R.P. Modular multilevel converters: Recent achievements and challenges. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2021, 2, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyond. Difference Between LV and MV Switchgear: Design, Safety & TCO. Available online: https://www.liyond.com/blog/difference-between-lv-and-mv-switchgear/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Pineele. What Is MV vs LV? Understanding Medium Voltage vs Low Voltage. Available online: https://pineele.com/what-is-mv-vs-lv-understanding-medium-voltage-vs-low-voltage (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Ding, X.; Zhou, Y.; Cheng, J. A review of gallium nitride power device and its applications in motor drive. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2019, 3, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q. Comparative analysis of SiC and GaN: Third-generation semiconductor materials. Highlights Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 81, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, G.; Di Fatta, A.; Rizzo, G.; Ala, G.; Romano, P.; Imburgia, A. Comprehensive Review of Wide-Bandgap (WBG) Devices: SiC MOSFET and Its Failure Modes Affecting Reliability. Physchem 2025, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafran, A.S. A feasibility study of implementing IEEE 1547 and IEEE 2030 standards for microgrid in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Energies 2023, 16, 1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leloux, J.; Narvarte, L.; Trebosc, D. Review of the performance of residential PV systems in Belgium. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, T. IEEE 1547 and 2030 Standards for Distributed Energy Resources Interconnection and Interoperability with the Electricity Grid; No. NREL/TP-5D00-63157; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2014.

- Radhiah, R. Inverter Performance in Grid-Connected Photovoltaic System. J. Litek J. List. Telekomun. Elektron. 2021, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trubitsyn, A.; Pierquet, B.J.; Hayman, A.K.; Gamache, G.E.; Sullivan, C.R.; Perreault, D.J. High-efficiency inverter for photovoltaic applications. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition, Atlanta, GA, USA, 12–16 September 2010; pp. 2803–2810. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE 1547; Standard for Interconnection and Interoperability of Distributed Energy Resources with Associated Electric Power Systems Interfaces. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018.

- Chen, W.; Huang, A.Q.; Li, C.; Wang, G.; Gu, W. Analysis and comparison of medium voltage high power DC/DC converters for offshore wind energy systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2012, 28, 2014–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, R.; Ebner, S.; Apeldoorn, O. Reliability in Medium Voltage Converters for Wind Turbines; The European Wind Energy Association (EWEA): Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Beheshtaein, S.; Cuzner, R.M.; Forouzesh, M.; Savaghebi, M.; Guerrero, J.M. DC microgrid protection: A comprehensive review. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea-Mena, B.; Valencia-Velasquez, J.A.; López-Lezama, J.M.; Cano-Quintero, J.B.; Muñoz-Galeano, N. Circuit breakers in low-and medium-voltage DC microgrids for protection against short-circuit electrical faults: Evolution and future challenges. Appl. Sci. 2021, 12, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzari, R.; Piegari, L. Short-Circuit Protection Schemes for LVDC Microgrids Based on the Combination of Hybrid Circuit Breakers and Mechanical Breakers. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2023, 2023, 9403058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayati, N.; Hajizadeh, A.; Soltani, M. Protection in DC microgrids: A comparative review. IET Smart Grid 2018, 1, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Han, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L. Study on fault current characteristics and current limiting method of plug-in devices in VSC-DC distribution system. Energies 2019, 12, 3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banavath, S.N.; Pogulaguntla, A.; De Carne, G.; Joševski, M.; Singh, R. Transformative role of solid-state circuit breakers in advancing DC systems for a sustainable world. IEEE Power Electron. Mag. 2025, 11, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.L.; Antoniazzi, A.; Raciti, L.; Leoni, D. Design of solid-state circuit breaker-based protection for DC shipboard power systems. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2016, 5, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moheb, A.M.; El-Hay, E.A.; El-Fergany, A.A. Comprehensive review on fault ride-through requirements of renewable hybrid microgrids. Energies 2022, 15, 6785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottrell, N.; Green, T.C. Investigation into the post-fault recovery time of a droop controlled inverter-interfaced microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE 6th International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems (PEDG), Aachen, Germany, 22–25 June 2015; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Chouhan, S.; Mohammadi, F.D.; Feliachi, A.; Solanki, J.M.; Choudhry, M.A. Hybrid MAS fault location, isolation, and restoration for smart distribution system with microgrids. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), Boston, MA, USA, 17–21 July 2016; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Latorre, A. Protection of Shipboard DC Systems: From Capacitors to Ultrafast Devices. Doctoral Dissertation, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkavanoudis, S.I.; Oureilidis, K.O.; Demoulias, C.S. Fault ride-through capability of a microgrid with wtgs and supercapacitor storage during balanced and unbalanced utility voltage sags. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Madrid, Spain, 20–23 October 2013; pp. 231–236. [Google Scholar]

| Features | Grid-Forming Converter | Grid-Following Converter | Grid-Supporting Converter | Interlinking Converter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source type | Controlled voltage source | Controlled current source | Controlled voltage/current source | Controlled voltage/current source |

| Output impedance | Low | High | Medium | Medium |

| Control strategy | Constant V/f (AC), Constant Voltage (DC) | PQ control (AC), Current control (DC) | Droop control (P/f, Q/V for AC; V-I or V-P for DC) | Bidirectional droop control |

| Associated sources | Dispatchable (ESS) | Renewable (Solar, Wind) | Dispatchable DGs/ESS | Both AC and DC grids |

| Voltage and frequency stability | Fixed | Synchronized with the grid | Regulated | Regulated |

| Operational modes | Islanded (IS) | Grid-connected (GC) | Both IS/GC | Both IS/GC |

| Power flow control | Two-way | One-way | Mostly two-way | Two-way |

| Converter Type | Description | Advantage | Disadvantage | Direction | Power Control Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diode Rectifier (Uncontrolled) | Uses diodes for AC-DC conversion | Simple, robust | No voltage control | One-way (Unidirectional) | Grid-Following |

| Thyristor Rectifier (Controlled) | Uses thyristors for controlled rectification | Voltage control possible | Generates harmonics | One-way (Unidirectional) | Grid-Following, Limited Grid-Supporting |

| Pulse width modulation (PWM) Rectifier (Active Rectifier) | Uses IGBTs/MOSFETs for controlled rectification | High efficiency, low harmonics, bidirectional | Complex control system | Two-way (Bidirectional) | Interlinking, Grid-Supporting |

| Inverter (DC-AC Converter) | Converts DC to AC | High efficiency in power conversion | Generate harmonics if not properly controlled | One-way (Unidirectional) | Grid-Following |

| Bidirectional AC-DC Converter | AC to DC and DC to AC | Supports grid-tied energy storage | High control complexity | Two-way (Bidirectional) | Interlinking, Grid-Supporting |

| Converter Type | Description | Advantage | Disadvantage | Direction | Power Control Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buck Converter | Steps down DC voltage | Simple, efficient | Cannot boost voltage | One-way (Unidirectional) | Grid-Following |

| Boost Converter | Steps up DC voltage | Increases voltage efficiently | Sensitive to load variations | One-way (Unidirectional) | Grid-Following |

| Bidirectional DC-DC Converter | Allows bidirectional power flow | Ideal for battery charging/discharging | Complex control | Two-way (Bidirectional) | Interlinking and Grid-Supporting |

| Converter Type | Description | Advantage | Disadvantage | Direction | Power Control Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage Source Converter (VSC) | Converts between AC and DC | High efficiency, power quality control | Requires complex control | Two-way (Bidirectional) | Always Interlinking, Grid-Supporting |

| Current Source Converter (CSC) | Uses inductors for energy storage | High reliability | Requires large inductors | Two-way (Bidirectional) | Interlinking, Grid-Supporting |

| (a) | |||||

| Ref. | Converter Topology | Control Strategies | Power Rating | THD | Response Time |

| [20] | LCL filter-based voltage source converter (VSC) | Multi-resonant (3R) Controller-Repetitive Controller (RC)-Droop Control-PI Controller-Phase-Locked Loop (PLL) | 1.35 kW (for nonlinear load condition) | Reduced from 12.10% to 3.51% after compensation | Approximately 5 cycles |

| [29] | Bidirectional Interface Converter (BIC) | Virtual Inertial Control Strategy based on Virtual Synchronous Generator (VSG) | 40 kW (DC load) and 30 kW (AC load) | N/A | N/A |

| [30] | Interlinking Converter (IC) with Voltage Source Inverter (VSI) | Symmetrical Impedance Network (SIN) and Dedicated Modulation Scheme | 1.4 kW total | N/A | Not mentioned |

| [31] | Interlinking Converter (IC) with Voltage Source Inverter (VSI) | Large-Bandwidth Triple-Loop Control (LBTLC) | approximately 2.4 kW | N/A | Islanded mode detection within 1.5 cycles |

| [32] | Interlinking Converter (ILC) with Hybrid AC/DC Grid | Passivity-Based Control (PBC) with Dual-Droop Control | 4 MVA Synchronous Generator, 1 MW & 3 MW DC Sources | N/A | N/A |

| [33] | Interlinking Converter (ILC) for Hybrid MG | Virtual Synchronous Machine (VSM) Based Droop Control | 50 kW hybrid MG system | N/A | N/A |

| [34] | voltage Source Converter (VSC)-based Interlinking Converter (IC) | Parabolic Relaxation Method for Optimal Power Flow (OPF) | 1 MW (DC), 1 MVA (AC) hybrid MG | N/A | Sequential penalization takes 7.34 s; real-time OPF updates occur every 10 s |

| [35] | Interlinking Converter (VSC) | Local Control Method, Normalized Droop Control | 16 kW | N/A | N/A |

| [36] | Interlinking Converter (VSC) | Voltage-Controlled Method (VCM) with PR Controllers | 15 kW | N/A | N/A |

| [37] | Bidirectional Interface Converter (BIC) | Dual-Side Virtual Inertia Control with Virtual Inductors | 1.167 MW (DC MG) and 2 MW (AC MG) | N/A | N/A |

| [38] | Interlinking Converter (VSC) | Droop Control with Active Power Filtering (APF) | 10 kW | Reduced from 13.08% to 4.09% | Improved dynamic response with reduced overshoot |

| [39] | Parallel LCC-VSC Interlinking Converter | Unified Control with Droop-Based Coordination | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| (b) | |||||

| Ref. | limitations | Experimental or Simulation | Goal | ||

| [20] | The IC controller requires precise tuning to effectively eliminate harmonics. High-order harmonics (above 18th) may not be fully. | Both Simulation and Experiment | Improve Power Quality-Enhance power flow management | ||

| [29] | The effectiveness of virtual inertia control is dependent on the tuning of virtual capacitance parameters. High virtual capacitance values may slow down dynamic response. Implementation may require high computational effort for parallel BICs. | Simulation | Improving AC bus frequency and DC bus voltage inertia to enhance stability of AC-DC hybrid MG | ||

| [30] | Requires precise tuning of impedance network parameters. Leakage current suppression is limited to the low-voltage DC side. Power decoupling strategies may be needed for stable operation. | Experimental | Flexible integration of renewable energy into hybrid AC/DC grids with high power density, low leakage currents, and controllable power flow | ||

| [31] | Requires precise tuning for seamless transitions between grid-tied and islanded modes. Low-voltage ride-through (LVRT) capabilities depend on predefined threshold settings. Complex control structure may increase implementation difficulty. | Experimental | Achieving multifunctional flexible control of interlinking converters for hybrid AC/DC MGs, ensuring power quality, seamless mode transitions, and low-voltage ride-through capability. | ||

| [32] | The passivity-based approach is a sufficient condition but may not always be necessary for stability. Requires accurate modeling of AC and DC bus dynamics. Control tuning is complex due to decentralized nature. | Simulation | Ensuring stable power sharing and voltage/frequency regulation in hybrid AC/DC grids | ||

| [33] | Virtual inertia parameter tuning affects system stability and dynamic response. High computational requirements for real-time implementation. Effectiveness under large disturbances needs further validation. | Simulation | Enhancing frequency stability and voltage regulation in hybrid MG systems | ||

| [34] | Nonconvex nature of OPF requires sequential penalization for feasible solutions. Voltage phase-angle constraints must be carefully tuned to ensure accuracy. Computational complexity increases for large-scale systems. | Simulation and Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) validation | Enhancing computational efficiency of OPF in hybrid AC/DC MGs while ensuring power balance and voltage regulation. | ||

| [35] | Normalized droop control has limitations in achieving accurate GPS; Large droop constants may cause instability | Simulation and Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) Experiments | Improve power sharing accuracy, enhance system stability | ||

| [36] | Requires precise tuning of PR controllers; Complexity increases with additional MGs | Both Simulation and Experiment | Improve power quality by reducing frequency deviation and voltage unbalance | ||

| [37] | Requires precise tuning of virtual inertia parameters; Complex implementation for real-world deployment | Simulation-based study with small-signal modeling | Enhance stability of hybrid AC-DC MGs by mitigating frequency fluctuations and voltage dips | ||

| [38] | Requires precise tuning of droop coefficients; Performance is affected by nonlinear load variations | Simulation and Real-Time Digital Simulator (RTDS) Experiments | Improve power quality by mitigating harmonics and ensuring stable power sharing | ||

| [39] | Requires precise droop coefficient tuning; Complex implementation for hybrid AC/DC networks. | Real-Time Simulation | Improve power sharing, enhance stability, mitigate commutation failure in LCC | ||

| Converter Type | Description | Advantage | Disadvantage | Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutral Point Clamped (NPC) Converter | Uses diodes to create multiple voltage levels | Lower switching losses | Requires additional components | Two-way (Bidirectional) |

| Flying Capacitor (FC) Converter | Uses capacitors for voltage levels | Better voltage balancing | More complex | Two-way (Bidirectional) |

| Cascaded H-Bridge (CHB) Converter | Uses series-connected H-bridges | Modular, scalable | Requires isolated power sources | Two-way (Bidirectional) |

| Modular Multilevel Converter (MMC) | Uses multiple submodules | High efficiency, reduced harmonics | High cost, complexity | Two-way (Bidirectional) |

| Converter Type | Load Dynamics | Distribution Performance | Harmonic Mitigation | Voltage Stability | Bidirectional Capability | Fault Tolerance | Validation | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSC [46] | √ | ✗ | √ | √ | ✗ | ✗ | Sim | Power stability |

| VSC [53] | √ | √ | √ | √ | ✗ | √ | Both | High quality |

| Boost [56] | √ | √ | ✗ | √ | √ | ✗ | Sim | PV extraction |

| Bidirectional DC-DC [59] | √ | √ | ✗ | √ | √ | ✗ | Sim | Power management |

| NPC [66] | √ | √ | √ | √ | ✗ | √ | Both | Voltage balancing |

| FC [73] | √ | √ | √ | √ | ✗ | √ | Both | DC-link quality |

| CHB [75] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ✗ | Sim | Voltage balancing |

| MMC [82] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Sim | Modular stability |

| Control Layer | Function and Scope | Typical Variables Controlled | Control Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary (Local) Control | Voltage/frequency formation, current/power injection, transient response. | Active/Reactive Power (P/Q), Local Voltage (V), Current (I). | Milliseconds |

| Voltage/frequency formation, current/power injection, transient response. | Voltage/frequency restoration, accurate power sharing, error elimination. | Voltage Reference Adjustments, Frequency Correction Signal. | Seconds |

| Active/Reactive Power (P/Q), Local Voltage (V), Current (I). | Optimal power flow (OPF), economic dispatch, inter-MG power trading. | Real/Reactive Power Flow Reference to Main Grid/Utility. | Minutes/Hours |

| Strategy | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation | Computational Burden | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Predictive Control (MPC) | Excellent dynamic response, handles constraints naturally, low THD [98] | High computational complexity, sensitivity to model accuracy | High | High-power VSCs, stringent power quality demands |

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) | Highly adaptive, quick decision-making post-training [99] | Requires extensive training data, lack of guaranteed stability | High (Training), Medium (Online) | Energy management, complex systems where scalability is prioritized |

| Sliding Mode Control (SMC) | High robustness against uncertainties and disturbances | Chattering phenomenon (rapid switching), requires detailed system knowledge | Medium | Fault-tolerant control, systems with high parameter variations |

| (a) | ||||

| Ref. | Converter Topology/Application | Control Strategy | Rated Power (kW/MVA) | Voltage Level (V/kV) |

| [13] | Bidirectional Interlinking Converter (BIC) | Virtual Inertia Emulation | Not Specified | Weak Grid Conditions |

| [36] | Single Interlinking Converter (IC) | PLL-less Voltage Controlled Method (VCM) | ~5 kVA (simulation) | 220 V (AC), 400 V (DC) |

| [103] | High Step-Up DC-DC Converter (SISO) | Dynamic Modeling, Control Strategy | 500 W (prototype) | Not Specified |

| [104] | Smart Grid Inverter | Hierarchical Control Strategy (HCS) | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| [105] | Unified Power Quality Conditioner (UPQC) | Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) Controller | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| [106] | Bidirectional Interlinking Converter (IC) | Decentralized Control with APF | 100 kVA (simulation) | 415 V (AC), 700 V (DC) |

| [107] | Modular Multilevel Converter (MMC) | Interleaved Half-Bridge Sub-Modules | Not Specified | Low/Medium Voltage |

| [6] | Solid-State Transformer (SST) | Not Specified | 1000 kVA | MV/LV |

| (b) | ||||

| Ref. | Efficiency (%) | THD (%) | Response/Settling Time (ms) | Switching Frequency (kHz) |

| [13] | >97% (implied) | <5% (implied) | >45% improvement in frequency deviation | Not Specified |

| [36] | Not Specified | <2% (under load transient) | ~20 ms | 10 |

| [103] | 96.4% (at 200 W) | Not Applicable | Not Specified | 50 |

| [104] | Not Specified | <5% (oscillation) | <400 | Not Specified |

| [105] | Not Specified | 0.04, 0.25, 0.98 | Not Specified | Not Specified |

| [106] | Not Specified | <5% (as per IEEE 519) | ~20 ms (for THD correction) | 10 |

| [107] | >98% (typical for MMC) | <3% (typical for MMC) | Not Specified | Varies (low effective freq.) |

| [6] | Slightly lower than passive transformer | Not Specified | Not Specified | High (for HF transformer) |

| Control Strategy | Primary Use Case | When Is It Preferable? | Key Trade-Off |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptive Droop Control | Power sharing in systems with varying load conditions or line impedances. | Preferable when high sharing accuracy is needed without complex communication infrastructure. | Requires careful tuning of adaptation gains to avoid instability during large transients. |

| Adaptive Virtual Impedance (AVIDC) | Low-voltage (resistive) microgrids where P/Q coupling is an issue. | Preferable for decoupling active/reactive power control and ensuring accurate reactive power sharing in resistive lines | Can slightly reduce the effective voltage range at the point of common coupling. |

| Model Predictive Control (MPC) | High-performance VSCs requiring fast dynamic response and constraint handling. | Preferable when the system has strict operational constraints such as, current limits and requires excellent transient response and low THD. | High computational burden; performance is highly sensitive to parameter mismatches in the internal model. |

| Hybrid Learning (RL + MPC) | Complex, large-scale systems where standard MPC is too slow. | Preferable for real-time implementation of optimal control where online optimization such as MILP is computationally prohibitive. | Requires extensive offline training data and a robust training phase before deployment. |

| Converter Type | LV Applications (≤1 kV) | MV Applications (1 kV–35 kV) |

|---|---|---|

| AC-DC Converters (Rectifiers) | Used in LV MGs, battery chargers, power supplies | Used in MV substations, industrial applications |

| DC-AC Converters (Inverters) | Used in solar inverters, UPS, motor drives | Used in MV grid-tied renewable systems, industrial motor drives |

| DC-DC Converters | Used in LV battery storage, EVs, MGs | Rare, but sometimes used in MV DC grids |

| Bidirectional DC-DC Converters | Used in energy storage (batteries, super capacitors), EVs | Rare, as MV systems typically use transformers for power conversion |

| Voltage Source Converters (VSCs) | Used in LV MG interlinking, UPS, and PV inverters | Used in MV FACTS (Flexible AC Transmission Systems), HVDC links |

| Current Source Converters (CSCs) | Rare in LV applications | Used in MV motor drives, grid control |

| Multilevel Converters (MLCs) | Rarely used in LV | Common in MV applications (HVDC, STATCOM, industrial motor drives) |

| Modular Multilevel Converter (MMC) | Not typically used in LV | Used in HVDC, STATCOM, large MV drives |

| Parameter | Low-Voltage (LV) Systems | Medium-Voltage (MV) Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Voltage Class (IEC/ANSI) | Up to 1 kV AC/1.5 kV DC [116] | 1 kV to 36 kV (up to 72.5 kV in some standards) [115] |

| Typical Power Ratings | Watts to ~250 kW (e.g., residential/commercial) [116] | >250 kW to Multi-MVA (e.g., industrial, utility-scale) [115] |

| Dominant Semiconductor Tech. | Si-MOSFET/IGBT. Increasingly Gallium Nitride (GaN) for high-frequency, high-efficiency applications [117] | Si-IGBT/GTO. Increasingly Silicon Carbide (SiC) for higher voltage/temperature and IGCTs for high power [119] |

| Key Interconnection Standards | IEEE 1547 for Distributed Energy Resources (DERs) interconnected with distribution networks [120] | Utility-specific transmission and distribution grid codes (e.g., BDEW, ENTSO-E); IEEE C37 series for switchgear [116] |

| Insulation Requirements | Primarily air-insulated with standard component clearances. Focus on user safety and accessibility [116] | Requires specialized insulation media (SF6, vacuum, oil) and larger creepage/clearance distances to manage high electric fields [116] |

| Primary Protection Devices | Fuses, Miniature Circuit Breakers (MCBs), Molded Case Circuit Breakers (MCCBs) [116] | Vacuum/SF6 Circuit Breakers, advanced digital protection relays, high-rupturing capacity fuses [115] |

| Design Philosophy | Focus on modularity, cost-effectiveness, high power density, and compliance with standardized interconnection rules for mass deployment. | Focus on high reliability, robustness, operational safety, and bespoke engineering for critical, high-power infrastructure. |

| Fault Type | Affected Component(s) | Inherent Fault Response/Key Challenge | Primary Protection Device | Device Technology | Typical Control Action | Reported Clearing Time (µs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC Pole-to-Pole (Low Impedance) | VSC-based Converters, DC Bus Capacitors | Uncontrolled capacitor discharge through anti-parallel diodes; extremely high di/dt [130] | Solid-State Circuit Breaker (SSCB) | SiC MOSFET, IGBT, IGCT | Ultra-fast Isolation | 0.2 (200 ns) [138], 3.6, 10 and160 [134] |

| DC Pole-to-Pole (Low Impedance) | CSC-based Converters | Inherent fault current limiting due to large DC-link inductor; slower di/dt [133]. | Mechanical DC Circuit Breaker (MCB) or Hybrid CB | Mechanical/Solid-State Hybrid | Isolation | >1000 (ms range) |

| DC Pole-to-Ground (High Impedance) | DC Bus, Grounding System | Low fault current magnitude; difficult to detect in ungrounded/high-Z grounded systems [131]. | Ground Fault Detector, Differential Protection Relay | Digital Relay | Alarm/Coordinated Trip | Detection-dependent |

| AC Symmetrical Fault (3-Phase) | Grid Interface, AC-side of ILC | Causes severe voltage sag at PCC, potential for VSC overcurrent and DC-link overvoltage [139] | STATCOM, DVR, Fault Current Limiter (FCL) [135] | FACTS Devices, Superconductors | Fault Ride-Through (FRT): Reactive power injection to support grid voltage [135] | N/A (Support Action) |

| AC Asymmetrical Fault (L-G, L-L) | Grid Interface, AC-side of ILC | Creates negative sequence voltage/current, causing torque pulsations in machines and DC-link voltage ripple [139] | Crowbar Circuit, Series Dynamic Resistor (SDR) [135] | Thyristor, Resistor Grid | FRT: Negative sequence current injection to balance grid voltages [139] | N/A (Support Action) |

| Post-Fault Recovery | Entire Microgrid | System oscillations, voltage/frequency instability post-clearance. Recovery time is sensitive to line impedance [136] | Microgrid Central Controller (MGCC) | Multi-Agent System (MAS) | Coordinated restoration, load shedding, resynchronization [137] | Seconds to minutes |

| Fault Type | Affected Component(s) | Inherent Fault Response/Key Challenge | Primary Protection Device | Device Technology | Typical Control Action | Reported Clearing Time (µs) |

| DC Pole-to-Pole (Low Impedance) | VSC-based Converters, DC Bus Capacitors | Uncontrolled capacitor discharge through anti-parallel diodes; extremely high di/dt [130] | Solid-State Circuit Breaker (SSCB) | SiC MOSFET, IGBT, IGCT | Ultra-fast Isolation | 0.2 (200 ns) [137], 3.6, 10 and160 [134] |

| DC Pole-to-Pole (Low Impedance) | CSC-based Converters | Inherent fault current limiting due to large DC-link inductor; slower di/dt [133]. | Mechanical DC Circuit Breaker (MCB) or Hybrid CB | Mechanical/Solid-State Hybrid | Isolation | >1000 (ms range) |

| DC Pole-to-Ground (High Impedance) | DC Bus, Grounding System | Low fault current magnitude; difficult to detect in ungrounded/high-Z grounded systems [131]. | Ground Fault Detector, Differential Protection Relay | Digital Relay | Alarm/Coordinated Trip | Detection-dependent |

| AC Symmetrical Fault (3-Phase) | Grid Interface, AC-side of ILC | Causes severe voltage sag at PCC, potential for VSC overcurrent and DC-link overvoltage [139] | STATCOM, DVR, Fault Current Limiter (FCL) [135] | FACTS Devices, Superconductors | Fault Ride-Through (FRT): Reactive power injection to support grid voltage [135] | N/A (Support Action) |

| AC Asymmetrical Fault (L-G, L-L) | Grid Interface, AC-side of ILC | Creates negative sequence voltage/current, causing torque pulsations in machines and DC-link voltage ripple [139] | Crowbar Circuit, Series Dynamic Resistor (SDR) [135] | Thyristor, Resistor Grid | FRT: Negative sequence current injection to balance grid voltages [139] | N/A (Support Action) |

| Post-Fault Recovery | Entire Microgrid | System oscillations, voltage/frequency instability post-clearance. Recovery time is sensitive to line impedance [136] | Microgrid Central Controller (MGCC) | Multi-Agent System (MAS) | Coordinated restoration, load shedding, resynchronization [137] | Seconds to minutes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jabari, M.; Ghoreishi, M.; Bragatto, T.; Santori, F.; Cresta, M.; Geri, A.; Maccioni, M. Advancing Hybrid AC/DC Microgrid Converters: Modeling, Control Strategies, and Fault Behavior Analysis. Energies 2025, 18, 6302. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236302

Jabari M, Ghoreishi M, Bragatto T, Santori F, Cresta M, Geri A, Maccioni M. Advancing Hybrid AC/DC Microgrid Converters: Modeling, Control Strategies, and Fault Behavior Analysis. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6302. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236302

Chicago/Turabian StyleJabari, Mostafa, Mohammad Ghoreishi, Tommaso Bragatto, Francesca Santori, Massimo Cresta, Alberto Geri, and Marco Maccioni. 2025. "Advancing Hybrid AC/DC Microgrid Converters: Modeling, Control Strategies, and Fault Behavior Analysis" Energies 18, no. 23: 6302. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236302

APA StyleJabari, M., Ghoreishi, M., Bragatto, T., Santori, F., Cresta, M., Geri, A., & Maccioni, M. (2025). Advancing Hybrid AC/DC Microgrid Converters: Modeling, Control Strategies, and Fault Behavior Analysis. Energies, 18(23), 6302. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236302