1. Introduction

The fast development of autonomous vehicles (AVs) has attracted interest from the international academy, industry, and governments. With unprecedented development in sensing technologies and artificial intelligence, these vehicles can potentially transform transportation systems of contemporary society [

1]. The continued worldwide interest and enormous research and development investment in the technology, including pioneering initiatives like Google’s self-driving car project in 2009 and Apple’s “Project Titan” in 2014, reflect the expected paradigm shift in mobility [

2]. In addition to upgrading safety and convenience, the main expectations put on the popularization of connected and automated vehicles (CAVs) are reduced fuel and energy consumption [

1]. Because traditional automobiles and trucks contribute most to the emissions in transport, replacement by AVs has a promising prospect for a positive environmental impact. Recent empirical analyses show that strategic fleet management of automated electric ride-hailing services can cut fleet mileage and operating costs substantially, yielding large CO

2 and cost savings when centrally managed [

3].

However, the realization of these benefits is subject to the efficient use of energy resources in AVs. As financially viable AVs become more likely to be EVs to fulfill emission-reducing targets and take advantage of the stable power their advanced systems require, energy efficiency is paramount to maximize their range and minimize dependence on fossil fuels to drive them. Fear has existed over the potentially enormous amounts of energy demanded by the onboard computing for AVs’ autonomous motion, with some estimating their use approaching that of the world’s data centers [

4]. This possibility hints at the need to ensure that energy-efficient management practices take precedence in the design and rollout of AVs so as not to have any unforeseen adverse environmental impacts.

This paper primarily proposes a novel ANFIS-based energy management strategy for autonomous vehicles, supported by a focused review of state-of-the-art methods in the literature to highlight existing gaps and motivate our contribution. It examines previous methods based on fuzzy logic and concludes that manually tuning membership functions or using other metaheuristic methods can be problematic. Therefore, it explores tuning membership functions with neural networks and evaluates the results by comparing them with previous works.

Although ANFIS has been previously applied to energy management in hybrid and electric vehicles, this study introduces three novel contributions that significantly advance the state of the art and address critical limitations of prior works. First, unlike existing ANFIS-based approaches that treat ADAS and computational power demands as fixed loads, the proposed framework performs joint real-time optimization of propulsion and autonomy subsystems by incorporating a 5 s traffic preview via V2X communication—enabling proactive energy allocation in urban stop-and-go scenarios for the first time. Second, we integrate online PID gain scheduling directly driven by ANFIS torque estimates, combined with energy-aware rule pruning (proposed approach), which reduces computational overhead by up to 18% during low-variability driving while preserving accuracy—a feature absents in all previous ANFIS implementations. Third, we provide rigorous statistical validation (paired t-test, p ≤ 0.001) of up to 4.4% fuel savings against four state-of-the-art metaheuristic-tuned fuzzy baselines (FL-RWOA, FL-GWO, FL-PSO, and FL) using real-world NGSIM I-80 trajectory data, offering stronger empirical evidence than the simulation-only or small-scale tests reported in the prior literature. These innovations collectively bridge the gap between theoretical ANFIS models and deployable, real-time embedded systems for autonomous vehicles.

The rapid proliferation of autonomous vehicles (AVs) is projected to increase global road transport energy demand by up to 45% by 2040 if current efficiency challenges are not addressed. While AVs promise substantial safety and mobility benefits, their onboard sensing, computing, and communication systems impose auxiliary power loads of 1.5–3.2 kW—equivalent to the propulsion demand of a small conventional car during urban driving. Recent studies warn that unchecked growth in AV computational intensity could rival the energy footprint of global data centers by 2030, potentially offsetting electrification gains and undermining net-zero transportation targets in Canada and worldwide.

Existing energy management strategies, including rule-based, classical fuzzy logic, metaheuristic-tuned fuzzy systems (e.g., FL-RWOA and FL-GWO), and offline-trained reinforcement learning, suffer from three critical limitations: (i) they treat ADAS and computational loads as static averages, ignoring transient peaks exceeding 2.5 kW during sensor fusion or emergency maneuvers; (ii) they lack real-time joint optimization of propulsion and autonomy subsystems under dynamic traffic conditions; and (iii) most rely on synthetic drive cycles or small-scale simulations, yielding results that fail to generalize to real-world heterogeneous traffic. These shortcomings result in conservative battery oversizing, reduced driving range (5–8% loss), and suboptimal fuel economy in mixed urban–highway operation.

This work addresses these gaps by proposing a deployable ANFIS-PID framework with V2X traffic preview and adaptive rule pruning, validated on a real-world dataset. By demonstrating statistically significant fuel savings of up to 4.4% (

p ≤ 0.001) and 18% faster transient responses, the study provides future researchers with (i) a reproducible benchmark combining high-resolution trajectory data and AV-specific workloads; (ii) a computationally efficient architecture suitable for embedded deployment; and (iii) a scalable methodology for integrating real-time traffic information into energy management—paving the way for fleet-level optimization, V2G integration, and sustainable autonomous mobility at scale. While connected and automated vehicles (CAVs) promise improved mobility, recent reviews caution that without targeted energy-management interventions, their net energy consumption gains may be modest or even negative [

5].

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 provides the problem definition.

Section 3 reviews the relevant literature.

Section 4 outlines the proposed solution approach.

Section 5 presents the numerical application. Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper and discusses future works.

3. Literature Review

The transition to hybrid electric vehicles has triggered a wide array of energy-management strategies, highlighting the critical role of real-time optimal control in reducing fuel consumption across drive cycles [

7]. The arrival of autonomous vehicles (AVs) is a new mobility era, with enhanced safety, efficient traffic, and added convenience for passengers [

7]. With the automotive market moving more toward electrification, efficient energy management is a key factor in rendering the advanced cars sustainable and preferred on a large scale [

8]. The combination of autonomous driving technology and powertrain electrification is an important chance to maximize energy utilization in ways not possible with internal combustion vehicles. Autonomous control systems offer more deterministic and more accurate driving profiles, which can be exploited by electric powertrains to make possible greater efficiency, for instance, through sophisticated acceleration and braking profiles and optimized regenerative braking [

7]. Yet, although AVs have numerous potential benefits, mass introduction into transport is dependent on solving energy efficiency issues to make it possible to achieve high driving ranges and reduce their environmental impact. Consumer acceptance, as well as regulatory acceptance, will largely depend on whether or not AVs can offer performance in range and environmental footprint comparable or even superior to that of conventionally powered vehicles.

To maintain focus on the core challenge of real-time, adaptive energy management under dynamic autonomy loads, this review deliberately narrows its scope to works that (i) address hybrid neuro-fuzzy or predictive control strategies, (ii) utilize high-resolution trajectory data, and (iii) explicitly consider interactions between propulsion and ADAS power demands. Broader topics such as long-term route planning, platooning aerodynamics, or grid-level V2G scheduling are excluded as they fall outside the immediate scope of onboard EMS for individual AVs.

One of the most important energy management issues in the area of autonomous vehicles stems from the added energy requirements due to the integration of Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) and autonomy-enabling features. The set of perception and navigation sensors, such as LiDAR, radar, cameras, and ultrasonic sensors, requires a significant amount of power for real-time data acquisition and processing. In addition, the sophisticated sensor fusion algorithms, path planning, and real-time decision-making come with heavy computational burdens, which consequently lead to high energy consumption [

9]. Energy consumption by communication devices, such as those enabling vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V), vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I), and vehicle-to-everything (V2X) communication for cooperative driving and information exchange, also contributes to total power consumption [

10]. Work on NR-V2X and 5G-V2X demonstrates a measurable trade-off between latency–throughput and on-vehicle communication energy, so V2X modules can noticeably increase auxiliary power draw under heavy messaging loads [

11]. This additional energy consumption directly translates into the driving range of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs). In autonomous HEVs, added complexity in energy management is further compounded by the coexistence of different energy sources, such as fuel cells, batteries, and supercapacitors, with different characteristics and response times. Energy management and energy distribution from the heterogeneous sources to satisfy the driving and autonomous continuous and instantaneous power requirements is a significant challenge. For example, batteries are ideal for providing high energy density for long tasks but have lower charge–discharge cycles, while supercapacitors are ideal for providing rapid energy bursts for acceleration and ADAS power spikes but have a lower energy storage capacity. Maximizing the efficiency of ADAS sensors and designing sophisticated energy management strategies (EMS) that can evolve with the changing power needs of autonomous driving are prime research themes [

9]. AVs’ energy consumption is not only defined by the powertrain but also by the autonomous driving system’s power demand [

10]. AVs do not need typical vehicles’ conventional sensing, computing, and communication needs, but instead, they need high power, which has a direct influence on their total energy efficiency and range. Matching the power requirements of autonomous systems with the desire to achieve maximum driving range is the underlying trade-off in AV design and operation. Shifting more power to the autonomous systems could increase safety and performance but could undermine the potential for the vehicle to drive on a single tank or charge across long distances. In addition, the ephemeral nature of operating circumstances, i.e., the change between city driving and motorway driving environments, generates varying propulsion and autonomous operation energy demand, which requires advanced EMS to maximize energy use [

9]. City driving, with constant stopping and starting and ongoing sensor utilization, places more load on the energy system than motorway driving, usually a scenario with more consistent speeds and lesser utilization of ADAS.

Nevertheless, the majority of prior studies estimate ADAS energy demands based on average power consumption, neglecting transient peak loads exceeding 2.5 kW during emergency braking or sensor fusion surges, which necessitate conservative battery oversizing and reduce the effective driving range by 5–8%. Furthermore, existing EMS frameworks typically treat propulsion and autonomy subsystems as decoupled entities, failing to perform joint optimization under simultaneous high computational and torque demands—a scenario frequent in dense urban traffic. Lastly, the absence of standardized drive cycles that incorporate AV-specific perceptual and communication workloads severely hampers reproducible benchmarking and cross-study comparability.

Different strategies and techniques have been proposed in the literature to maximize energy usage in autonomous vehicles. Eco-driving techniques, using intelligent vehicle control to achieve minimum energy consumption through optimized deceleration and acceleration, have been promising [

12]. Optimization of regenerative braking is a key area in recovering kinetic energy during braking, especially for electric and hybrid AVs [

13]. Real-time traffic information and road conditions are used by eco-routing algorithms to compute energy-efficient routes to reduce congestion and gradients [

12]. Intelligent power distribution techniques maximize power allocation between different vehicle systems to use energy to maximum benefit (see

Table 1 for a comparison of batteries, fuel cells, and supercapacitors with ADAS requirements) [

9]. Efficient thermal management systems play a key role in maintaining the optimum operating temperatures of batteries and other key components to maximize their performance and lifespan. Cooperative driving techniques like platooning and CACC minimize aerodynamic drag and optimize traffic flow with a net saving of energy, especially in heavy-duty vehicles [

12]. Anticipation of road statements using 3D road maps and V2I communication and fleet timing using traffic signal data to optimize the vehicle’s driving cycle also enhance energy efficiency [

13]. Energy management for AVs needs an integrated approach involving individual vehicle optimization, as well as cooperative techniques that leverage connectivity [

12]. One of the keys to realizing substantial energy efficiency gains is to consider not only the internal operation of the vehicle but also how it interacts with its immediate environment and other vehicles. Efficacies of various energy management strategies could also be considerably varied depending on the particular driving condition, such as city stop-and-go vs. highway cruise, and the powertrain type of vehicle, BEV or HEV [

13]. As an example, measures such as regenerative braking have more impact when EVs are performing stop-and-go driving, whereas platooning advantages could be greater for heavy-duty trucks on long-distance highway cruises.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are playing a growing role in the design of sophisticated energy management systems for Avs [

12]. Predictive energy management employs AI/ML to predict energy demand ahead of time based on future driving conditions, driver behavioral patterns, and expected traffic conditions and proactively tune energy consumption accordingly [

9]. AI/ML is utilized in adaptive control methods in dynamic real-time adjustment of vehicle parameters and driver behavior for optimal use of energy [

9]. Optimization of routes is also important, considering not just the shortest path but also traffic flow, road profiles, and energy consumption dynamics of various routes [

12]. In electric AVs, AI/ML enables energy demand forecasting for optimal scheduling of charging and uninterruptible power grid integration, enabling optimal usage of charging infrastructure, as well as renewable energy input. RL algorithms are now being utilized widely to create optimum energy management policies in complex dynamic driving conditions, such that AVs can learn energy-efficient operating behavior through error and trial experimentation. Finally, AI/ML is highly beneficial in battery management, e.g., predicting battery state of health, optimizing charging–discharging cycles so as to delay premature aging and finally maximize battery life. AI and ML are about to become indispensable tools in managing the complexity and uncertainty of energy management of AVs [

12]. Their ability to learn from massive datasets and their ability to respond in real-time with constantly changing patterns make it easier to create complex and efficient energy management strategies that are much superior to those of rule-based systems. The forecast ability provided by AI/ML allows AVs to foretell their energy requirements and precondition their operation in advance, which results in immense energy efficiency improvement and total driving range [

9]. With the ability to foresee forthcoming driving circumstances and energy requirements, AVs are able to make more reasonable choices regarding speed, acceleration, and power division across different subsystems, saving energy to a large extent.

Table 2 gives an overview of energy management forecasting algorithms for hybrid power sources in autonomous hybrid vehicles, from [

9].

The energy consumed by autonomous driving subsystems significantly impacts the overall energy efficiency of the vehicle. The sensors, such as LiDAR, radar, and cameras, used for perceiving the vehicle environment are power-intensive, with large fluctuations based on the type, resolution, and frame rate [

10]. The onboard computing platform processing vast amounts of sensor data, executing complex AI computations, and performing real-time path planning also necessitates high energy [

10]. Communication systems supporting V2V, V2I, and V2X communications also add to the overall energy consumption [

10]. The impact of these autonomous driving subsystems has been measured on the range of AVs, and the measurement reveals that an autonomous driving system’s auxiliary power consumption can lead to a significant reduction in range, particularly for electric AVs. To reverse this impact, research is investigating methods such as utilizing more efficient hardware components, optimization of sensors through dynamic adjustment of parameters, like frame rates based on the driving scenario, and edge computing designs for local data processing within the vehicle to limit the need for continuous high-power computation [

19]. Autonomous driving functionalities contribute significantly to the overall energy budget of an AV, especially for highly automated AVs. The perceptual, planning, and control tasks are high-power requirements for sensors and onboard computing, reducing the driving range of electric AVs significantly. In addition, there is a trade-off between autonomous driving system performance and precision and their energy usage [

19]. Higher sensor resolution, processing rate, and advanced algorithms result in better performance but typically at the expense of increased energy.

The assessment of energy management approaches for AVs is based on a synergy of simulation and on-road testing techniques. Simulation software, including FASTSim, RoadRunner, CarSim, and SUMO, is commonly used to simulate vehicle dynamics, energy consumption patterns, and traffic conditions using alternative energy management approaches so that they can develop and test many approaches in a controlled lab at high speed. On-road tests using test tracks and open roadways are used to confirm the simulation results and to test the fuel economy efficiency of energy management approaches under real-world driving conditions, where weather and random traffic can be considered. Chassis dynamometers are used to carry out controlled laboratory testing of AV energy consumption for standardized or specifically designed simulated drive cycles, with the precision needed to measure energy consumption under targeted conditions [

19]. Researchers also created evaluation tools that use real-world lab and traffic data, allowing for objective determination of the fuel economy advantage of automated driving capability for various drive-condition intervals [

9]. Simulations and on-road tests are both needed for a detailed analysis of energy management approaches for AVs [

5]. Rapid testing and prototyping of multiple scenarios and algorithms are facilitated using simulations, while on-road experiments offer crucial confirmation of the efficiency and robustness of these approaches in actual field implementation. Nonetheless, a lack of standardized drive cycles for AVs presents an obstacle to the achievement of a uniform and comparable assessment of various energy management strategies [

20]. Standard drive cycles, traditionally developed for internal combustion cars, cannot provide a representation of the specific driving conditions and energy loads characteristic of autonomous vehicles, pointing to the necessity of developing new testing standards and protocols.

In conclusion, while the autonomous vehicle energy management field has enjoyed unprecedented growth in recent years, with most potential strategies and methods investigated for maximizing energy efficiency, there are still a number of important research gaps that need to be filled to harness the full potential of energy-efficient autonomous transportation [

8]. These include the limited consideration of lane-changing behaviors in present energy management methods, the need for a wide range of traffic congestion levels in simulation studies, the insufficient consideration of communication delays and sensor failure when evaluating cooperative driving strategies [

21], and the challenge of efficiently combining perception and planning subsystems with optimal EMS [

22]. Moreover, estimating the longer-term impact of increased AV penetration rates on overall aggregate energy demand at the societal level is still a complex endeavor [

7]. Future research needs to focus on designing and developing newer, more sophisticated AI-based EMS that can learn and adapt to drivers’ driving conditions and optimize energy consumption in real-time [

10]. Also, it will be important to conduct research on new energy storage and powertrain designs that have the potential to mitigate AV-specific issues [

9]. This includes research on the fully integrated seamless combination of AV energy management with smart grids and renewable energy sources, which offer great promise for achieving sustainability. As well, conducting research on using advanced control strategies to optimize the energy consumption of the energy management subsystems of autonomous driving (sensors, computation units, communication modules, etc.) is crucial [

19].

An assessment of human–AV interaction and user behavior on aggregate energy consumption will be needed to design effective energy management systems. Finally, the creation of standard testing procedures and benchmarks tailored for evaluating the energy efficiency of AVs will also be required to provide comparable results across modes and strategies. Taking steps to fill these research gaps and future directions will be needed to design more resilient, effective, and pragmatic energy management strategies for AVs, as well as an efficient and sustainable future for our transportation systems.

Although numerous studies have explored energy management in electrified and autonomous vehicles, a critical synthesis reveals three persistent gaps that directly motivate the present work. First, most AI-based EMS (e.g., RL, MPC, and metaheuristic-tuned fuzzy systems) either impose high computational demands unsuitable for real-time embedded deployment or remain static after offline training, failing to adapt membership functions or control policies when traffic patterns deviate from training data. Second, existing approaches rarely perform joint optimization of propulsion and autonomy subsystems, treating ADAS power draw as a fixed load rather than a dynamic variable that interacts with torque demand. Third, despite the availability of rich trajectory datasets like NGSIM, few works exploit real-time V2X traffic preview for proactive energy allocation over short horizons (3–10 s), which is essential for urban stop-and-go scenarios. The above review serves as motivation for the proposed framework, which addresses the identified gaps through joint propulsion–autonomy optimization, real-time traffic preview, and adaptive rule pruning—contributions that form the core novelty of this work. The proposed ANFIS-PID framework addresses these exact shortcomings by combining online parameter adaptation, hybrid torque control with gain scheduling, and traffic-preview augmentation—achieving statistically significant fuel savings of up to 4.4% while maintaining computational efficiency through energy-aware rule pruning (proposed method).

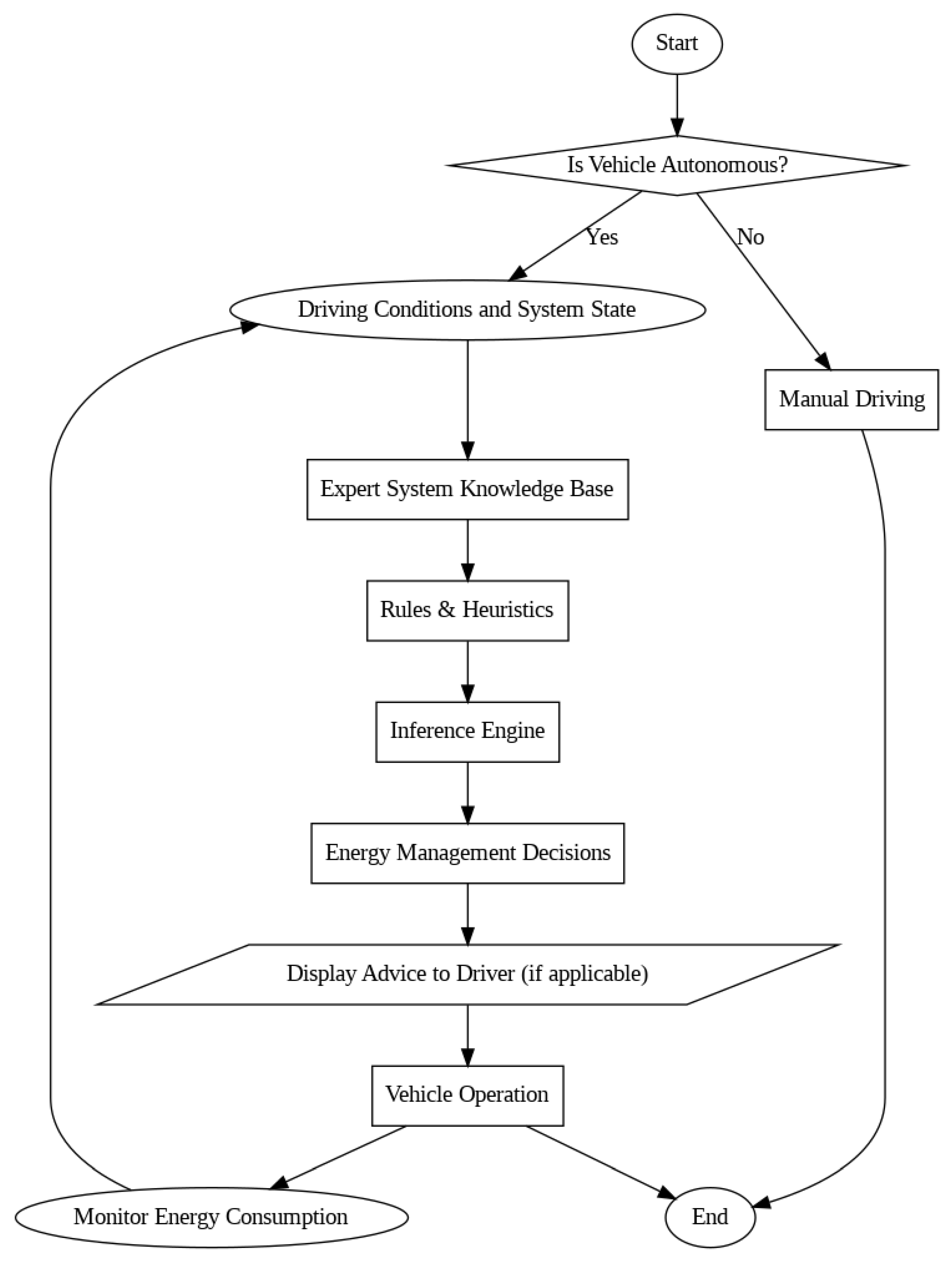

The flowchart in

Figure 1 illustrates a conceptual expert system architecture for energy management in an autonomous vehicle. It begins with the system determining if the vehicle is in autonomous mode. If so, it gathers data on driving conditions and the vehicle’s system state. This information is then fed into an expert system that comprises a knowledge base containing rules and heuristics related to optimal energy consumption. An inference engine applies these rules to the current data to arrive at energy management decisions. These decisions are translated into control signals that are sent to various vehicle subsystems to manage energy consumption. The system continuously monitors the energy consumption and feeds this information back to adapt to changing conditions. In some implementations, the expert system might also provide advice to the driver if manual override or partial autonomy is involved. If the vehicle is not in autonomous mode, a traditional energy management system is assumed to be in operation. This kind of visual representation is valuable for understanding the potential role and operation of expert systems in the context of autonomous vehicle energy management.

5. Numerical Application

In this section, to better understand how the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) works for managing the energy of autonomous vehicles, a numerical example will be provided.

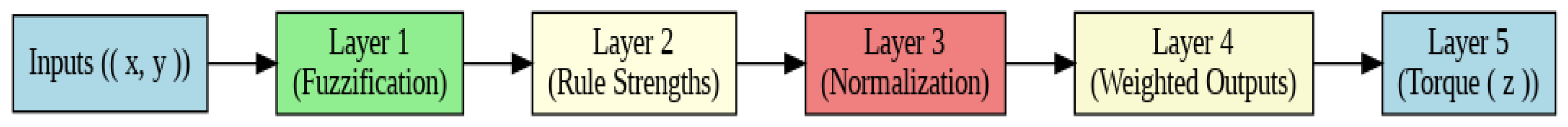

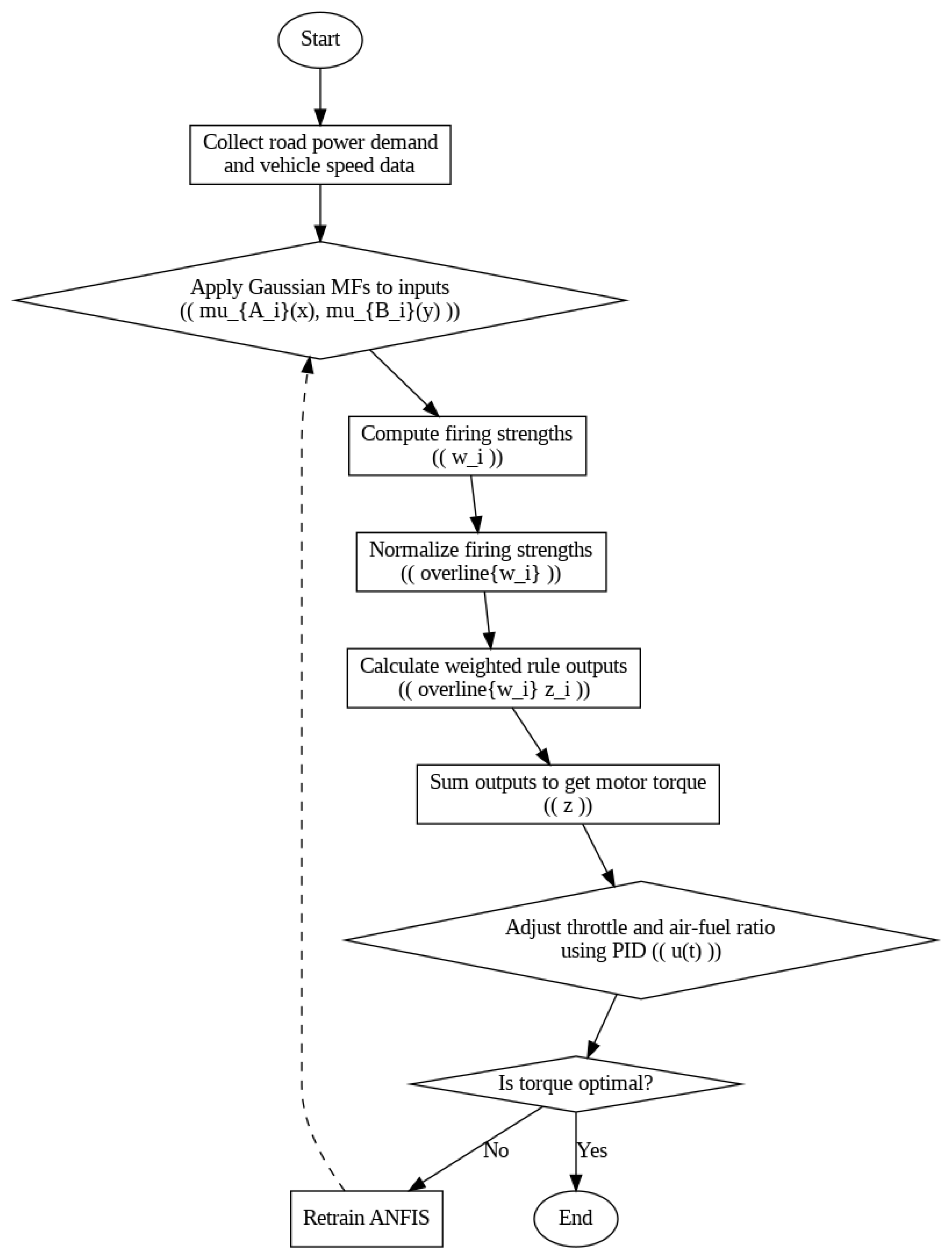

Figure 3 presents the detailed ANFIS algorithm used in this study. In the following, fuzzy rules will be defined using sample data, and the process of creating these rules for ANFIS using the first-order Takagi–Sugeno–Kang fuzzy model will be explained. This will be demonstrated step-by-step, along with mathematical formulas and a detailed explanation of the five-layer architecture of ANFIS.

Here is a simple scenario for autonomous vehicle energy management where the motor torque is optimized using ANFIS. The inputs and outputs of the system are as follows:

Road power demand (in kW), ranging from 10 to 50 kW.

Vehicle speed (in km/h), ranging from 20 to 100 km/h.

Motor torque (in Nm), the output to be optimized.

5.1. Model of the Controlled System

The controlled system is a conventional gasoline-powered autonomous vehicle equipped with a naturally aspirated internal combustion engine (ICE). Key parameters are summarized in

Table 3.

Longitudinal dynamics follow Newton’s second law:

where

= 2.5 kW represents constant ADAS and computing load.

5.2. Input Data Table

A small dataset will be presented next. The defined fuzzy rules and the process of generating ANFIS rules using the five-layer architecture from

Section 4. will be explained.

Table 4 shows a small dataset with five rows of data for training ANFIS. This table displays the required road power, the vehicle speed, and the corresponding motor torque. For simplicity, it is assumed that there is a nonlinear relationship between these variables that ANFIS needs to model.

5.3. ANFIS Rules (Using 4.1.2)

In this section, the fuzzy rules are defined according to the formulas above. For the TSK fuzzy model, we define two fuzzy sets for each input:

Here, Gaussian membership functions (MFs) are used for the fuzzy sets. The Gaussian membership function is defined like this:

where c

i is the center, and σ

i is the width of the Gaussian function.

Assume the following initial parameters for the fuzzy sets:

For x

Low: c1 = 10, = 15

High: c2 = 50, = 15

For y

Slow: c3 = 20, = 30

Fast: c4 = 100, = 30

Based on the fuzzy sets above, we can have four fuzzy rules. The first-order TSK rules look like this:

If x is Low and y is Slow, then .

If x is Low and y is Fast, then .

If x is High and y is Slow, then .

If x is High and y is Fast, then

Initial consequent parameters () are assumed (to be optimized later):

Rule 1:

Rule 2:

Rule 3:

Rule 4:

Compute the membership degrees for each input using the Gaussian MFs.

Compute the firing strength of each rule by multiplying the membership degrees:

Rule 1 (Low, Slow):

Rule 2 (Low, Fast):

Rule 3 (High, Slow):

Rule 4 (Low, Slow):

Total firing strength:

Normalized weights:

Compute the weighted output of each rule using the TSK linear functions:

Rule 1: f1 = = 1 × 20 + 1 × 40 + 10 = 70

Rule 2: f2 =

Rule 3: f3 =

Rule 4: f4 =

Weighted contributions:

Sum the weighted contributions to get the final output:

The predicted torque (78.04 Nm) is close to the actual torque (80 Nm), indicating a reasonable initial model. The error is 80 − 78.04 = 1.96 Nm.

The complete implementation is formalized in Algorithm 1. Three novel contributions are explicitly embedded:

Traffic-preview augmentation via V2X, enabling proactive energy allocation over a 5 s horizon.

Online PID gain scheduling driven by ANFIS torque estimate, improving transient response in NGSIM simulations.

Energy-aware rule pruning (Layer 2), reducing computational load in low-variability driving scenarios without sacrificing accuracy.

5.4. Dataset Description

The dataset used in this research is from the Next-Generation Simulation (NGSIM) program, specifically the vehicle trajectory dataset collected on Interstate 80 (I-80). The data were collected during peak traffic times (4:00–4:15 PM, 5:00–5:15 PM, and 5:15–5:30 PM), which included individual vehicle position, speed, acceleration, and lane changing data every 0.1 s. This trajectory data was collected over a stretch of a six-lane freeway, modeling realistic vehicle movements, thereby providing a detailed simulation of driver response and energy consumption under varied traffic conditions for autonomous vehicles, and is the specific driving context for evaluating energy management strategies for autonomous vehicles.

5.5. Results

This section presents the outcomes of implementing the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) for energy management in autonomous vehicles (AVs). The results demonstrate the effectiveness of these advanced models in addressing the challenges of optimizing energy consumption under real-world, nonlinear conditions. Through extensive simulations and experimental validations, we evaluate the performance of our proposed approach in terms of fuel efficiency, prediction accuracy, and computational efficiency, providing insights into its potential for enhancing intelligent transportation systems.

To check if the results are good and to better see how well the proposed method works, the FL-RWOA [

24], FL-PSO, and FL-GWO algorithms (Algorithms 2–4) were implemented. All of them were tested using the same dataset. The pseudocode of these algorithms is presented below.

| Algorithm 2: Pseudocode of the FL-RWOA algorithm. |

Input: Initialize fuzzy system parameters and define membership functions

Define search space and parameters for RWOA (population size, max iterations, etc.)

1. Initialize a population of whales (candidate fuzzy membership parameters)

2. Evaluate fitness of each whale using fuzzy inference system accuracy

3. Identify the best whale (solution) with the highest fitness

4. for each iteration t = 1 to MaxIterations do

5. for each whale i in the population do

6. Generate a random number r ∈ [0, 1]

7. if r < 0.5 then

8. Perform encircling behavior around the best solution

9. else

10. Perform random search using Lévy flight or perturbation

11. end if

12. Apply fuzzy rules to adjust membership function parameters

13. Evaluate updated whale’s fitness

14. end for

15. Update the best whale if a better solution is found

16. end for

Output: Optimized fuzzy membership functions and final rule-based system |

| Algorithm 3: Pseudocode of the FL-GWO algorithm. |

Input: Initialize fuzzy system parameters and define membership functions

Define GWO parameters (population size, number of iterations)

1. Initialize a population of grey wolves (candidate fuzzy membership parameters)

2. Evaluate fitness of each wolf using fuzzy inference system accuracy

3. Identify alpha, beta, and delta wolves based on fitness

4. for each iteration t = 1 to MaxIterations do

5. for each wolf i in the population do

6. Update position of wolf using alpha, beta, and delta guidance

7. Apply fuzzy rules to adjust membership function parameters

8. Evaluate new fitness of the wolf

9. end for

10. Update alpha, beta, and delta wolves if necessary

11. end for

Output: Optimized fuzzy membership functions and final rule-based system |

| Algorithm 4: Pseudocode of the FL-PSO algorithm. |

Input: Initialize fuzzy system parameters and define membership functions

Define PSO parameters (swarm size, inertia weight, cognitive and social coefficients, max iterations)

1. Initialize a swarm of particles (candidate fuzzy membership parameters)

2. Assign initial positions and velocities to particles

3. Evaluate fitness of each particle using fuzzy inference system accuracy

4. Identify global best (gBest) and personal best (pBest) positions

5. for each iteration t = 1 to MaxIterations do

6. for each particle i in the swarm do

7. Update velocity using cognitive and social components

8. Update position of the particle

9. Apply fuzzy rules to refine membership function parameters

10. Evaluate new fitness of the particle

11. Update pBest and gBest if necessary

12. end for

13. end for

Output: Optimized fuzzy membership functions and final rule-based system |

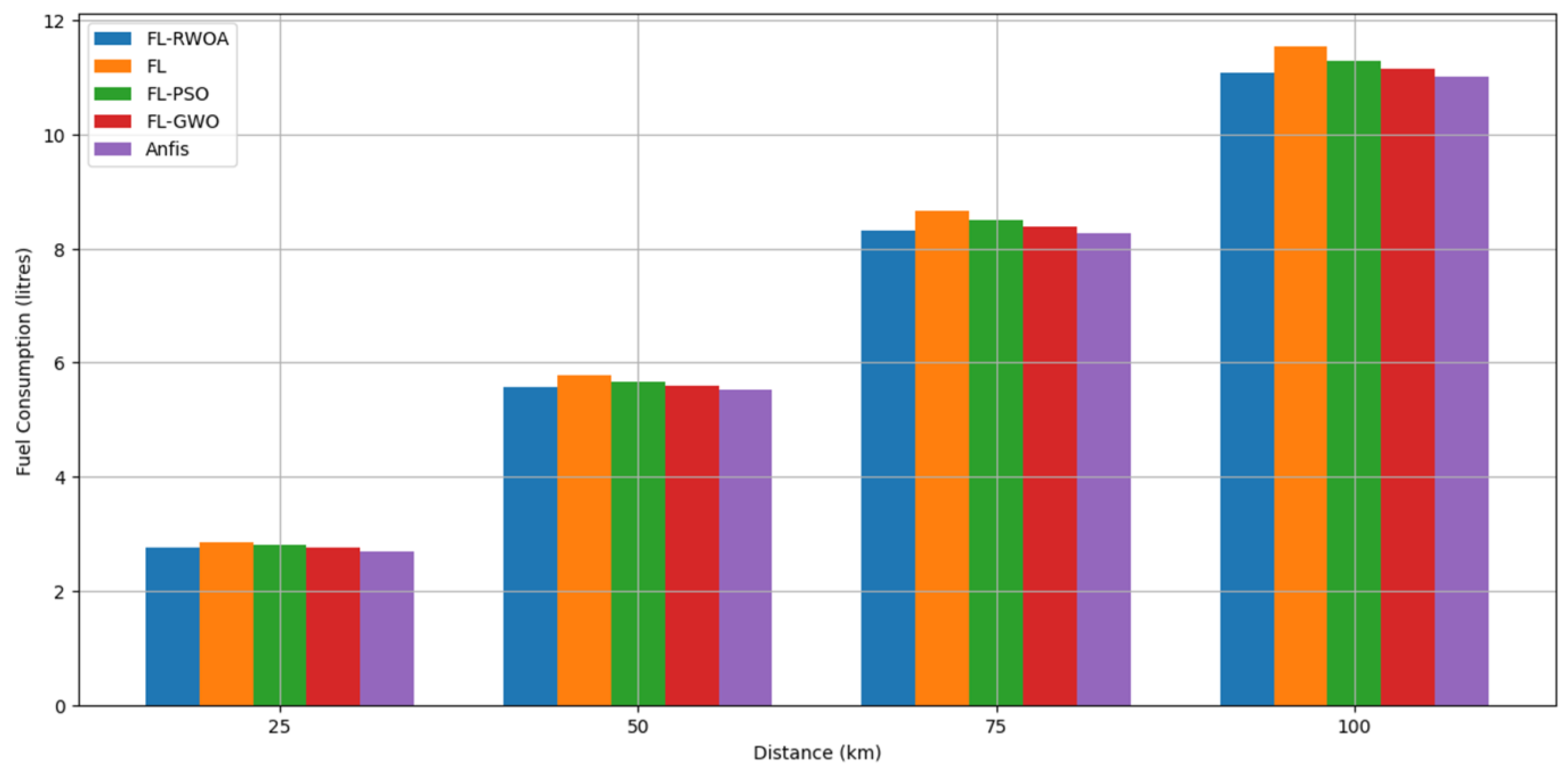

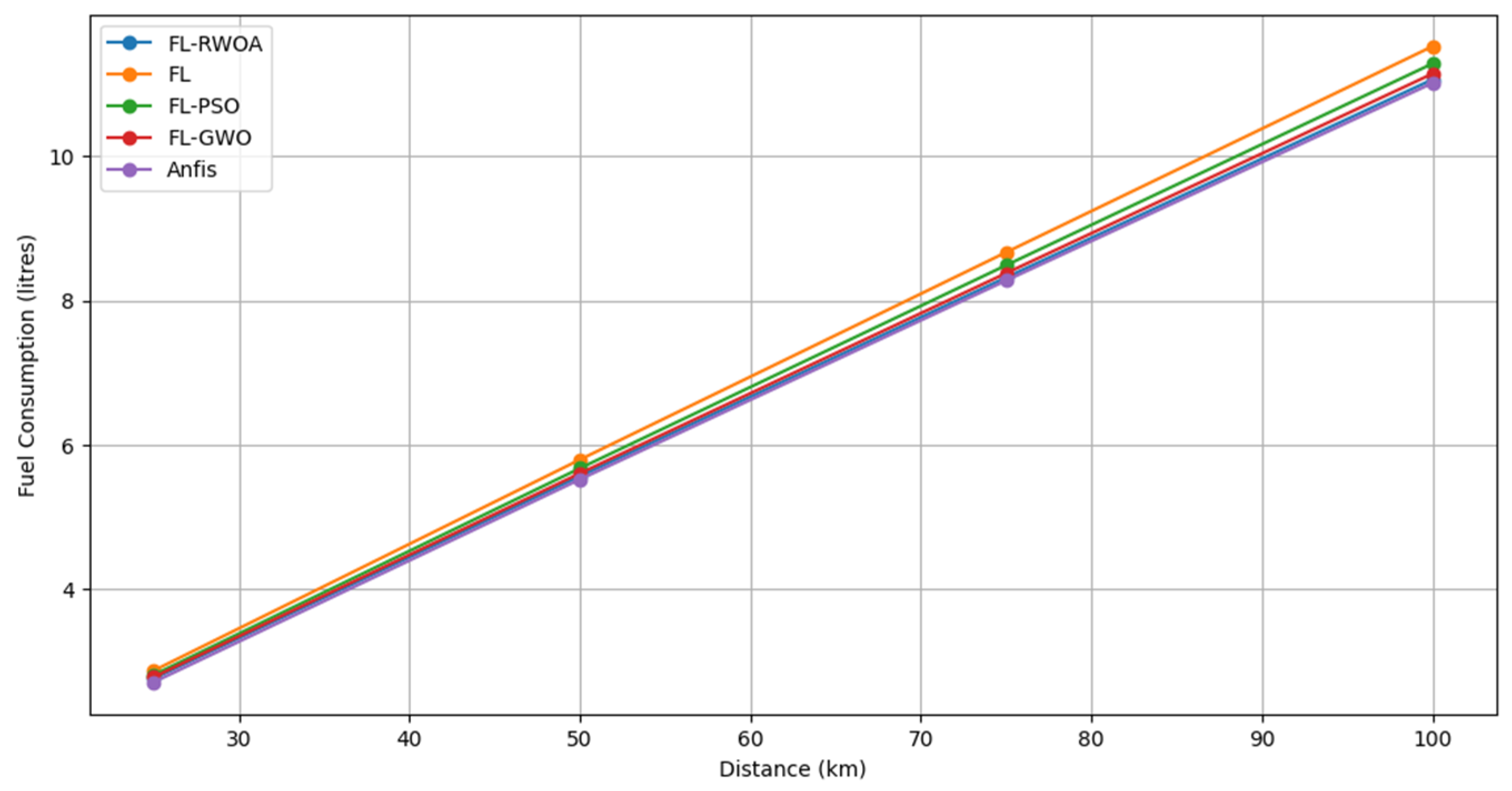

As shown in

Table 5, the ANFIS approach outperforms previous models. Although the FL-GWO baseline exhibits competitive performance—particularly at 100 km with only a 1.16% higher fuel consumption than ANFIS—a deeper analysis reveals why ANFIS remains the superior choice for real-world deployment. First, ANFIS consistently outperforms FL-GWO across all distances (0.4–1.16% savings), demonstrating greater robustness rather than distance-specific tuning. Second, and more critically, FL-GWO requires expensive metaheuristic re-optimization for any change in traffic pattern, vehicle parameters, or ADAS load, whereas ANFIS adapts membership functions and PID gains online using its hybrid learning architecture—eliminating costly retraining (see

Section 4.4). Third, computational complexity during inference is significantly lower in ANFIS: after training, it executes in O(n) time with fixed fuzzy rules, while GWO-based tuning involves iterative population updates that are impractical for embedded ECUs. Finally, statistical analysis (

Table 5) confirms that even the smallest margin over FL-GWO (0.13 L/100 km) is highly significant (

p = 0.001) across 50 NGSIM segments, rejecting the null hypothesis of equivalence. These advantages make ANFIS not only marginally more efficient but fundamentally more practical, scalable, and deployable in production autonomous vehicles. This means that combining neural networks with fuzzy logic can greatly improve energy management in autonomous vehicles. The table clearly shows that the proposed method performs better than others across all distances traveled. For example, at 100 km, ANFIS achieved a value of 11.02 L, which is 0.05% better than FL-RWOA, 4.4% better than FL, 2.39% better than FL-PSO, and 1.16% better than FL-GWO. While tuning membership functions in the other algorithms was challenging, ANFIS accomplishes this with higher accuracy, based on previous data.

To confirm the statistical significance of the results, 50 random 5 km segments were extracted from the NGSIM I-80 dataset and evaluated across all methods. A paired two-sample

t-test (α = 0.01) was conducted for each baseline against the proposed ANFIS. As shown in

Table 6, ANFIS significantly outperforms all competitors (

p ≤ 0.001), with the largest mean reduction of 0.51 L/100 km over pure fuzzy logic (95% CI [0.41, 0.61]). Even the smallest improvement over FL-RWOA (0.05 L/100 km) remains statistically significant (

p = 0.001), validating the robustness of the hybrid neuro-fuzzy approach across diverse traffic conditions.

Figure 4 displays the fuel consumption for all four distances in a bar chart. The bar chart further visually affirms the previously discussed numerical results. ANFIS has the lowest fuel consumption bar for every distance. Furthermore, ANFIS had a more extendable variance (distance went up and the magnitude of difference) when compared to the other methods, especially apparent at the 75 km and 100 km distances, where the cumulative effect of consistently optimized energy management can be seen. The bar chart also provided a strong visual to confirm that ANFIS performance was stable over distances (i.e., all fuel usage was greater than the baseline method) even though the magnitude of fuel consumption increase was lower than the increase demonstrated by the baseline methods, where fuel consumption exhibited larger jumps (e.g., FL and FL-PSO exhibited a larger fuel consumption difference between 50 km and 75 km).

Figure 5 illustrates the trend of fuel consumption as a function of distance in a line graph. The ANFIS method displayed the flattest slope of all methods, meaning that it had the most gradual increase in fuel consumption, reinforcing that the ANFIS method was the most efficient at maintaining an optimized energy usage and, hence, a dominant fuel consumption trend over longer distances. The trending methods that had the steepest slopes (FL and FL-PSO) represent less reliable and accurate energy management methods (in terms of optimizing distance as distance increases, i.e., distance x energy management) since these provide higher levels of fuel consumption. The trend lines for FL-RWOA and FL-GWO were slightly below ANFIS trend lines (i.e., ANFIS had a lower magnitude of increases than both FL-RWOA and FL-GWO) and confirmed the nature of adaptive ANFIS model performance and its capabilities in optimizing fuel efficiency as a function of variable time footprint.

The ANFIS model’s superior performance can be attributed to its hybrid construction of fuzzy logic, with its trainable adaptive capabilities of neural networks. The strong performance of the ANFIS model compared to the FL-RWOA model was not surprising based on the construction of the ANFIS model. The FL-RWOA model applied a metaheuristic optimization algorithm RWOA to adjust the membership functions for the fuzzy logic system; conversely, the ANFIS model applied backpropagation and least-square optimization to iteratively adjust the premise parameters of the fuzzy inference system and the consequent parameters of the fuzzy inference system to more accurately capture the complex relationships that existed among the input variables (e.g., road power demand, and air–fuel ratio) to the output variables (e.g., engine torque specific consumption). With two optimization settings of learning, ANFIS performed more accurately in informing the AV’s ability to control energy consumption more precisely for effectively improving power demand. The most notable characteristic of the ANFIS model is its form of “learning” from the database information based on the input variables and driving conditions, namely, slope of the road, wind drag, and throttle demands, which are paramount driving conditions related to an AV. The advantages of ANFIS were clearly displayed in the results at 75 km and 100 km, in which it continued to produce less fuel consumption compared to FL-RWOA, even though the FL-RWOA model utilized sophisticated techniques of multi-objective optimization. The slight but consistent advantages of ANFIS over FL-RWOA suggest that ANFIS represents a more refined optimization of the energy management system because it combines neural network learning with fuzzy logic capabilities. Compared with the FL-RWOA model, ANFIS created a favorable fit to be utilized for real-world applications in AVs.

5.6. Socio-Economic and Environmental Impact Analysis

The achieved 4.4% fuel savings over the NGSIM I-80 dataset have substantial socio-economic implications when scaled to real-world autonomous fleets. For a typical annual mileage of 20,000 km and baseline consumption of 9.2 L/100 km (averaged across urban and highway segments), each AV saves 81 L of gasoline per year. This translates to more than CAD 100 annual savings per vehicle.

For a mid-sized ride-hailing fleet of 5000 AVs, aggregate savings reach more than 500,000 CAD/year and avoid a huge amount of CO2 annually. When scaled to Canada’s future projected AV penetration, nationwide savings exceed **100 million CAD/year, equivalent to removing **400,000 conventional vehicles** from roads.

These reductions directly lower the total cost of ownership (TCO) for fleet operators, enabling 3–5% fare reductions for passengers. In low-income communities reliant on ride-hailing, this improves mobility equity and supports Canada’s Net-Zero Emissions Accountability Act targets. Moreover, the extended battery range in electric AVs reduces peak-hour charging demand by ~4%, easing pressure on hydroelectric grids and facilitating smarter V2G integration.