Abstract

Approximately half of the new EU buses are zero-emission. However, electric buses (BEBs) are highly sensitive to traffic conditions because their battery capacity determines their effective operational range. The primary objective of this article is to examine the influence of traffic conditions on the operation of electric buses in urban transportation systems, as well as the associated economic and managerial implications. Particular attention is given to the thesis that prioritizing BEB traffic in urban transport systems can reduce the need for larger, more expensive batteries, thereby lowering the total cost of ownership (TCO). Moreover, congestion limits the range of feasible battery technologies, such as excluding the use of lighter, longer-lasting lithium-titanium-oxide batteries (LTO), which could otherwise be applied under optimal traffic conditions. Traffic congestion also necessitates the deployment of additional vehicles to maintain service reliability, further increasing system cost. The analysis incorporates theoretical analysis, simulation analysis, and vehicle real operation data analysis. The results demonstrate that current efforts to maximize the battery capacity used in buses are not optimal from both cost efficiency and environmental impact perspectives. The impact of traffic conditions on electric buses varies depending on the specific charging methods used. Road traffic conditions have the most negligible impact on In Motion Charging electric buses. The findings have also demonstrated that road conditions are a significant cost-driving factor affecting the total costs of purchasing and operating electric buses.

1. Introduction

In response to the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve air quality and residents’ quality of life in cities, interest in electromobility in public transport is growing [1,2]. Battery electric buses (BEBs) are an important element of the ongoing transformation towards sustainable urban transportation systems, yet their implementation poses numerous challenges, particularly regarding the optimization of operational costs [2,3,4,5]. One of the key factors affecting the operating costs of BEBs is the battery size, which directly influences both the initial purchase cost and the expenses associated with its replacement during the vehicle’s operational lifespan [6,7]. An oversized battery increases the purchase cost of the vehicle, while an undersized one may lead to frequent planned and unplanned operational interruptions [8,9]. Moreover, a battery with insufficient capacity is likely to experience accelerated degradation due to intensive use, leading to the need for earlier replacement [10,11]. This, in turn, will contribute to increased costs over the vehicle’s entire life cycle. BEBs’ battery capacity is also closely tied to the costs of building the necessary charging infrastructure and the chosen charging strategy (Opportunity Charging, Overnight Charging, or In Motion Charging).

Implementing measures to optimize battery capacity in newly procured electric buses is a critical priority. The literature indicates that one transport-management instrument conducive to this goal is prioritizing bus traffic over private cars. Granting buses priority in mixed traffic, through dedicated lanes, contraflow lanes, and intelligent traffic signal control, reduces energy consumption (by lowering the frequency of braking and acceleration) and enables more efficient fleet utilization by optimizing charging windows and increasing average operational speed.

At the same time, the literature still offers relatively few well-documented case studies that capture the real-world effects of road congestion on urban bus systems. Numerous local and regional determinants, such as ambient temperature, route elevation profile, line length, and the maturity of charging infrastructure, limit the external validity of individual studies. This creates a clear research gap that calls for a broad set of analyses across diverse BEB systems in different cities and regions. This gap is also driven by the scarcity of studies that complement operational analyses with economic perspectives. Consequently, there is a lack of contributions that, beyond determining the effect of congestion on the required battery capacity of electric buses, also identify the ensuing economic implications.

The article aims to analyze the impact of road traffic congestion on the charging process of BEBs and to estimate the economic consequences of this impact. The thesis is that prioritizing BEB traffic can reduce the need for larger, more expensive batteries, thus lowering the total cost of ownership (TCO) for BEBs. This concept is further explored through the following research questions:

RQ1: To what extent is it possible to reduce battery capacity when the best possible traffic conditions are ensured?

RQ2: How much additional battery-related cost is generated in the operation of electric buses under traffic congestion compared to optimal traffic conditions?

To achieve the primary objective of the article and to address the formulated research questions, empirical data obtained during the operation of BEBs within the public transportation system of Gdynia (Poland) were utilized.

2. Literature Review

The Impact of Congestion on the Functioning of Electric Bus Systems

Unlike diesel buses (DBs), full-scale operation of BEBs requires taking into account the limitations resulting from the maximum range determined by the capacity of their traction batteries [12], location and parameters of the charging infrastructure [13], charging costs resulting from the high and possibly irregular demand for charging power [14] and the adopted operational model (ONC, OPP, and IMC). Considering these parameters, traffic congestion can play a decisive role in the stability of the e-bus operational concept. Among the 25 factors analyzed, the congestion index (together with HVAC, temperature outside, average speed, and average acc pedal) was found to be one of the most significant determinants of BEB’s electricity consumption [15]. Moreover, the increase in energy consumption by BEBs caused by traffic congestion reduces the environmental benefits typically associated with electric traction [16].

The cost of purchasing and replacing the traction battery is a significant part of the vehicle’s TCO [5,17,18,19]. Reducing the battery capacity not only reduces costs and increases the passenger-carrying capacity of buses but also reduces greenhouse gas emissions associated with the manufacturing process of batteries [20]. The electrification of bus lines involves the need to charge vehicles. This process often occurs at the end terminals of bus lines during scheduled layovers, which requires ensuring sufficient time for effective vehicle charging. Depending on traffic parameters, this may involve the need to provide additional vehicles due to extended stop times required to charge the batteries [21]. It is highly dependent on the type of charging method used, as more frequent charging can reduce battery-related costs. Charging vehicles while in motion and increasing the number of charging points can both lead to significant reductions in battery capacity, especially for IMC systems, and to a lesser extent for OPP systems [22]. However, charging at charging points is sensitive to traffic disruptions. In the event of traffic disruptions caused by congestion, vehicles may arrive delayed at the final stop, which consequently reduces the available time for battery charging. As a result, the vehicle might start the next leg of its journey with its battery incompletely charged. This entails the need to increase the number of vehicles in operation or to use batteries with higher capacity [12,23,24]. Even with a high number of bus charging stations, insufficient battery charging may occur [7,25], potentially causing transport system disruptions, including the need to deploy additional vehicles or delayed departure from the charging station. When charging batteries using chargers placed at end stops, the battery capacity must be sufficient to cover the distance between the two chargers, meaning the length of the bus line (if chargers are installed at both termini) or twice the length of the line (if only one charger is available). However, traffic delays caused by congestion may lead to a situation where charging is impossible. If such situations occur repeatedly, the required battery capacity may need to be increased several times over to maintain operational reliability. Consequently, in many cases, transport system operators tend to mitigate this risk by intentionally oversizing the traction batteries’ capacity.

Traffic congestion affects not only the required battery capacity but also significantly influences the choice of battery technology, which is closely related to that capacity (Table 1). In the case of BEBs charged in overnight mode (ONC), it is necessary to use batteries with very large capacity, which represent a significant part of the vehicle’s total price. Due to the high required capacity, NMC batteries are most often used in buses charged overnight. In contrast, OPP systems require smaller battery capacity, providing greater flexibility in the selection of battery technologies. In many cases, LTO batteries can be an attractive option, as they offer a service life comparable to that of the vehicle itself (up to 15 years) [26]. However, their limited capacity may restrict their applicability in BEBs [26,27]. Additionally, due to the risks associated with road traffic congestion, which can directly lead to difficulties in completing the charging process, this technology is often avoided despite its exceptional longevity.

Table 1.

Types of Batteries Used in Electric Buses.

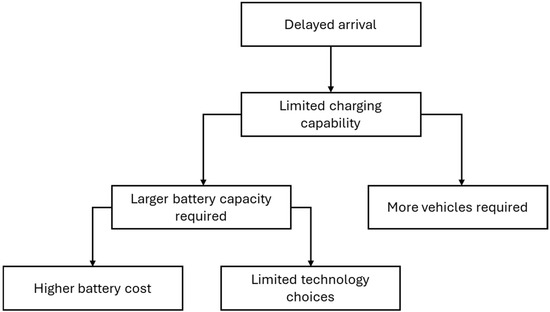

Figure 1 summarizes how traffic congestion directly causes delays in schedule adherence for urban buses and how this congestion, along with the resulting delays, impacts the operation of electric bus systems and their batteries. The figure indicates that:

Figure 1.

Diagram of the impact of congestion on the operation of batteries in electric buses. Source: Own elaboration.

- Delayed arrival is a consequence. Longer travel times due to congestion mean buses spend more time on the road, potentially increasing energy consumption per trip and reducing the time available for charging.

- This situation can lead to a limited charging capability, possibly because the reduced turnaround time due to delays does not allow for sufficient charging time between routes.

- To maintain service frequency despite delays caused by congestion, more vehicles may be required. This increases the overall number of electric buses in the fleet and, consequently, the total battery requirement.

- The increased time on the road and potential energy use due to delays might necessitate a larger battery capacity for each bus to ensure it can complete its route reliably.

- Requiring larger battery capacity typically results in higher battery cost, as larger batteries are generally more expensive.

- The specific demands on the battery system imposed by conditions like congestion (e.g., need for high capacity, specific charging profiles) may also lead to a limited choice of technologies available for the batteries (e.g., no possibility of using LTO batteries).

Congestion has been one of the most significant challenges to urban area development for many years. Public transport can be regarded as a sustainable alternative to private motorization, but it struggles with the far-reaching congestion effects [29]. Existing studies highlight various impacts of congestion on public transport, such as delays, decreased reliability, extended travel time and the need for more vehicles to maintain the timetable. BEBs are particularly sensitive to the effects of traffic congestion, which is why travel time uncertainty must be considered when planning their timetables [30]. Due to its limited range, determined by the battery and charging system parameters, a BEB is much more exposed to the effects of congestion than a DB.

The conducted literature review reveals a significant gap. There is little evidence available to fully understand the influence of congestion on the operation of electric public transport vehicles, which opens up opportunities for further research and real-case study analysis. Furthermore, the current literature lacks discussion on the importance of considering road traffic conditions in BEBs’ technical specifications from the perspective of economic efficiency.

The presented considerations lead to the conclusion that, in conditions of road traffic congestion, bus operators must consider purchasing larger batteries for their electric vehicles. This necessity stems from the increased energy consumption associated with more frequent stops and starts in congested traffic. Additionally, congestion affects both the duration and predictability of charging opportunities. In unfavorable scenarios, operators may be forced to skip a planned charging cycle in order to maintain schedule adherence. It can therefore be argued that under optimal traffic conditions, characterized by free-flowing traffic and bus priority measures, a smaller battery capacity would be sufficient to meet operational needs. However, such ideal road conditions are rarely achieved in practice. Therefore, operators must adjust their battery capacity requirements to reflect real-world traffic conditions, which can significantly impact both operational costs and the vehicle purchase price. In the authors’ opinion, this relationship has not received sufficient attention in the existing scientific literature and warrants further research.

3. Materials and Methodology

3.1. Methodology: Impact of Delays on Electric Bus Charging–Theoretical Background

The following presents a theoretical framework for assessing the impact of delays on the current operations of two types of electric vehicles: battery electric buses (BEBs) and trolleybuses equipped with traction batteries. For the purposes of this analysis, it is assumed that BEBs are charging using stationary opportunity charging (OPP charging), with the OPP station being the sole source of stationary charging during the day.

In the case of pure stationary charging, the total energy delivered to the vehicle is equal to the product of the charging power POPP, charging time tOPP and efficiency η:

In the event of an extension of the travel time due to congestion by the value δ, arrival at the final stop is delayed. Assuming the need to adhere to the timetable, i.e., a scheduled departure from the initial stop, the time available for charging is reduced analogously, which results in less energy being supplied during charging.

If the delay δ in movement occurs several k times, then it will result in insufficient battery charging. This will repeat k times and cause the ΔEch battery charge level to drop:

As indicated by the data, under extremely unfavorable conditions characterized by prolonged and significant delays, the minimum battery capacity required to ensure the reliable operation of a BEB may need to be more than three times higher compared to optimal conditions.

3.2. Case Study of Electric Buses and Trolleybuses in the Public Transport System of Gdynia

Gdynia is a medium-sized city in Poland (approx. 241,000 inhabitants) [31] located on the Baltic Sea. The public transport system in Gdynia consists of railway transport (managed by the regional authorities) and urban transport (managed by the city authorities). The latter supply includes the bus and trolleybus subsystems. Trolleybus transport has been operating in Gdynia since 1943 (linking the neighboring city of Sopot), and since 2015, it has been developed in the IMC model [32,33]. The first BEBs operating in a mixed model (OPP and ONC) were implemented in 2022. Table 2 presents the characteristics of particular urban transport subsystems in Gdynia. Still, DBs provide most of the public transport supply, although the share of electrified road public transport rose to 44% in 2023.

Table 2.

Features of the municipal public transport subsystems.

The increasing motorization rate has made congestion one of Gdynia’s most significant challenges for public transportation. Despite the steady expansion of bus lanes throughout the city, the public transport system continues to be adversely impacted by the rising number of private vehicles. Between 2012 and 2022, this number rose by 37%, and the motorization index in 2022 amounted to 678 cars per 1000 inhabitants [31]. As a result, the average speed of public transport vehicles between 2012 and 2021 decreased by 16% (from 15.7 km/h to 13.6 km/h). Notably, the supply of urban transport did not change significantly in the analyzed period (an increase of 1%). The vehicle-hours required to perform the timetable increased by 16%.

3.3. Characterization of Bus Line 150 as the Subject of the Case Study

Bus line 150 is one of the most important bus lines in Gdynia’s public transport network. The line is 15 km long, includes 26 stops and runs through the central part of the city. It operates seven days a week. BEBs were introduced on this line in 2022 and currently provide full service on the route. Table 3 presents the main features of the 150 line.

Table 3.

Key parameters of the e-bus 150 line in Gdynia.

The datasets obtained from the e-buses, mainly the State of Charge (SoC) information, made it possible to analyze the charging process over a broad time range. Another crucial data source in this respect is the intelligent transport system Tristar, which provides actual arrival and departure times for all stops. The Tristar data helped to identify traffic delays and quantify road traffic congestion. Integrating these two data sources made examining the relationship between road traffic congestion and battery charge levels possible. An important aspect of the analysis was the variability of traffic and energy conditions throughout the year. This variability was driven by seasonal differences in traffic patterns and significant variations in energy consumption between seasons, primarily due to the impact of vehicle heating.

4. Results

4.1. The Impact of Traffic Congestion on the Charging Process of Electric Buses Based on the Case Study

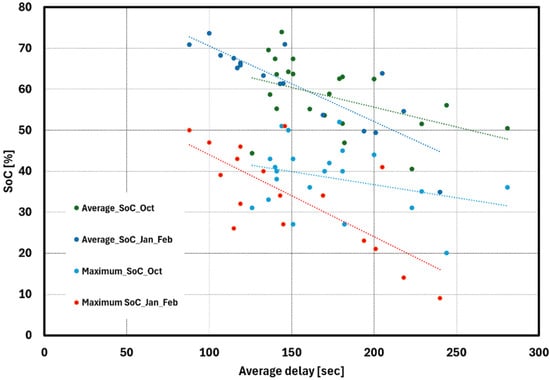

Figure 2 shows the relationship between the average daily SoC value of the batteries in buses in Gdynia (Poland) and the average traffic delay for October 2023 and the winter period January–February 2024. In winter, electricity consumption is much higher than in early autumn. This results in a greater degree of battery discharge during driving, and road traffic congestion has a much greater impact on this discharge level, as reflected in the average delay.

Figure 2.

Comparison of battery discharge characteristics for two periods: October and January-February. Source: own study based on the data collected from the bus operator in Gdynia (PKA sp. z.o.o., Gdynia, Poland).

Although the linear regression presented in Figure 2 demonstrates a clear statistical relationship between traffic delays and battery discharge levels, it is important to emphasize that this relationship is not deterministic. The depth of battery discharge is influenced by multiple operational and environmental factors beyond traffic congestion alone. These include ambient temperature, passenger load, HVAC usage, driving behavior, terrain profile, and battery aging. As a result, certain data points deviate from the regression line, reflecting the multifactorial nature of energy consumption in electric buses. The purpose of the regression analysis is not to provide a precise predictive model, but rather to illustrate the significant role that traffic congestion plays in shaping battery performance. Future work will aim to incorporate these additional variables into more advanced modeling frameworks.

The linear nature of the relationship between the average traffic delay and the battery SoC is evident, as shown in Figure 2. It is possible to determine the linear regression coefficient describing the relationship between the traffic delay value and the battery’s state of charge.

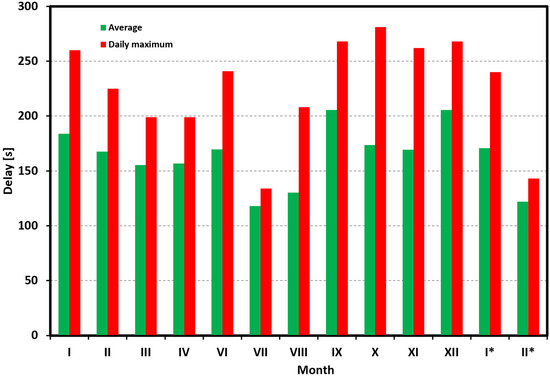

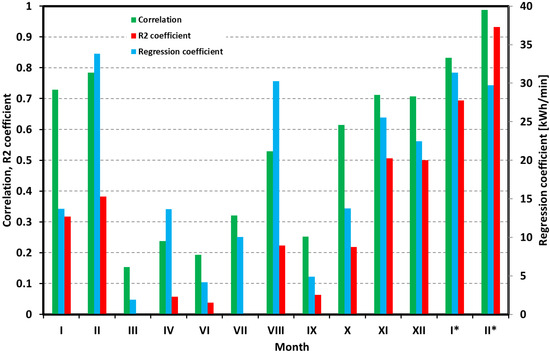

When analyzing the course of battery discharge annually, attention should be paid to the variability of road traffic congestion (Figure 3). In the case of line 150 since September 2023, road traffic conditions have deteriorated, increasing road traffic delays. As a consequence, the impact of the delay on the degree of battery discharge increased (Figure 4). An increase in the correlation and the R2 coefficient of linear regression is also visible with the deterioration of traffic conditions (Figure 4). This indicates an increase in the impact of traffic congestion on battery discharge with increasing traffic disruptions. Considering the battery’s nominal capacity, the relationship between the average traffic delay and the resulting necessary increase in battery capacity can also be determined (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Delay statistic of the BEB route 150 for the entirety of 2023 and the beginning of 2024. * data from 2024. Source: own study based on the data collected from the bus operator in Gdynia (PKA sp. z.o.o.).

Figure 4.

Linear regression coefficient between average delay and battery SoC, correlation coefficient and regression coefficient r2 between battery SoC and delay, January 2023–February 2024 (BEB, line 150). * data from 2024. Source: own study based on the data collected from the bus operator in Gdynia (PKA sp. z.o.o.).

The linear regression constant factor B determines the regression estimate value for a traffic delay equal to zero, i.e., in the absence of disruptions caused by road traffic congestion (regression model y = Ax + B). Based on factor B, it is possible to estimate the battery capacity in the case of delays caused by traffic congestion. For analysis, values from December can be taken as the month with the most significant energy consumption and dependence between delay and battery discharge. For this month, we can obtain the following values of the B coefficient:

- for average daily discharge: 44 kWh,

- for maximum daily discharge: 116 kWh.

It should be taken into account that, apart from congestion, other factors make it difficult to charge batteries, so without traffic delays, there may be a lack of battery charging at the end loops. Among the most important factors are limited layover times due to tight schedules, technical issues with charging stations, energy supply limitations, adverse weather conditions affecting charging efficiency, and operational constraints such as vehicle rotations or unexpected service changes [36,37,38,39]. Based on this and assuming the reserve of battery capacity, the following minimum battery capacities can be assumed for line 150 in the absence of congestion:

- 90 kWh if the certainty of charging at the end stops is guaranteed,

- 150 kWh if other difficulties in charging, besides congestion, are allowed.

4.2. Influence of Traffic Congestion on the Required Fleet Size of Urban Buses

In Gdynia, electric buses are fitted with a system that logs energy data, capturing key electrical and mechanical parameters of each journey on a per-second basis. Among the recorded metrics are vehicle speed, current demand from the traction system, total current consumption, and GPS coordinates.

An additional dataset used in the analysis comes from the Tristar system, which operates across the Tri-City area (Gdańsk, Sopot, Gdynia) as an intelligent urban traffic management platform. Tristar continuously monitors traffic flow and records various parameters, including the exact arrival and departure times of buses and trolleybuses at each stop.

This data enables precise determination of charging durations at terminal stations and under overhead catenary lines, even under real-world traffic congestion conditions.

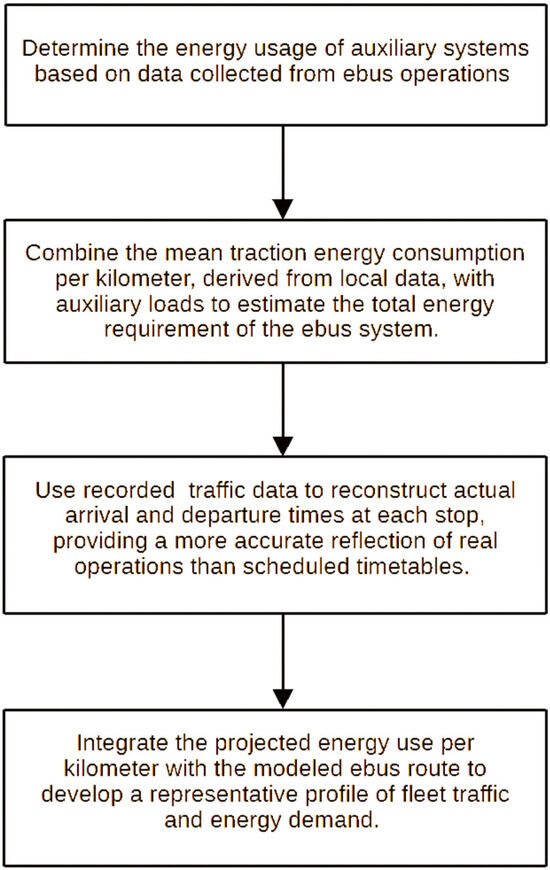

Energy consumption estimates are derived from Tristar’s records of stop-to-stop arrival and departure times for line 150, combined with the distances between stops. This information is used to calculate the discharge of traction batteries during travel between stops. The overall process, decomposed into individual steps, is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Procedure for deriving detailed operational and energy usage profiles from measurement data to support the case study analysis. Source: own study based on the data collected from the bus operator in Gdynia (PKA sp. z.o.o.).

To validate the relevance of the applied linear regression model, a comparison with selected state-of-the-art approaches was considered. For instance, the study by Zhang et al. [1] on hydrogen systems emphasizes the importance of systemic integration and multi-factor modeling in sustainable transport, while the work by Liu et al. [2] presents a stochastic optimization framework for multi-energy ship microgrids under uncertainty. Although these models address different transport modalities, they highlight the complexity of energy systems and the need for robust modeling approaches. In contrast, the simplified linear model used in this paper serves primarily as an introductory analytical tool to isolate and illustrate the specific impact of traffic congestion on battery discharge in electric buses. Future research will aim to incorporate multi-factor and stochastic modeling techniques to enhance analytical depth and generalizability.

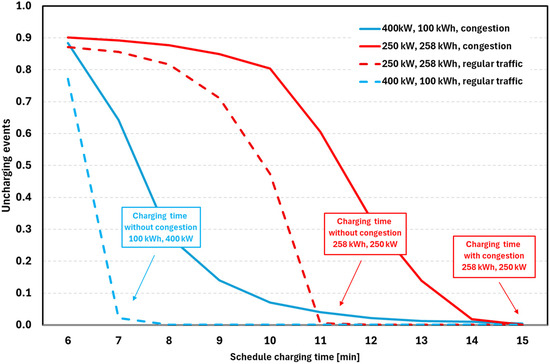

Based on the energy consumption data on line 150 and delay recording from the Tristar system, simulations of the bus charging process were performed for various scheduled charging times. To quantitatively assess the impact of road traffic congestion on the charging process, the impact of traffic disturbances, including ambient temperature changes, on the traction battery charging process has been analyzed. For the analysis, the operational parameters of bus line 150 were used. Calculations were made for two variants of batteries:

- NMC 258 kWh capacity, 250 kW charging power.

- LTO 150 kWh capacity, 400 kW charging power.

The calculations assumed a scheduled charging window at the terminal of 6–15 min, with the dwell time at the terminus calibrated to traffic-delay data from the Tristar system.

Because traffic delays reduce the time available for charging, the batteries may not reach full charge. Figure 6 presents the modeled frequency of instances in which the battery state of charge during operation fell below the acceptable threshold. The minimum discharge level for a battery is 30% of its rated capacity. A drop in charge below this value is considered an “uncharging event”. Such a situation requires using a reserve vehicle to operate a given line. Based on calculations, it can be concluded that in the case of scheduled traffic, it would be possible to reduce the number of vehicles necessary to service line 150 by one.

Figure 6.

Number of battery undercharging cases as a function of scheduled charging time for two battery solutions. Source: own study based on the data collected from the bus operator in Gdynia (PKA sp. z.o.o.).

4.3. Modeling Battery Degradation as a Cost Driver in Electric Buses

An important element affecting the operating costs over the entire life of an electric bus is the cost of replacing the battery. This is due to the battery degradation process, which consists of both cyclic aging and calendar aging. The battery aging calculations in this paper were performed in the Open-SESAME-Battery 1.2.0 simulation package. This package was developed by the Bern University of Applied Science (BFH) in Switzerland with contributions from Centre Suisse d’Electronique et de Microtechnique (CSEM) within the framework of the IEA task 32 funded by the Swiss Federal Office of Energy (SFOE). The Open-SESAME Battery package is an open-source battery simulation tool based on semi-empirical models.

The model inputs are, among others:

- Battery type;

- Battery size;

- Charge and discharge profiles (per second);

- Operating temperature.

The model outputs are, among others:

- Battery State of Health (SoH);

- Battery State of Resistance.

The total aging is then calculated from the sum of the calendric and the cyclical aging using a semi-empirical model that reproduces the aging measurements from experimental tests and/or literature data.

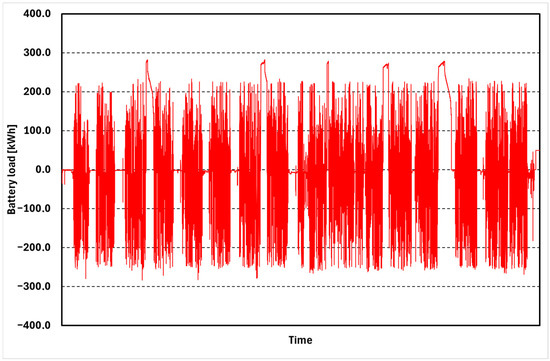

Figure 7 shows the recording of the traction battery load during service on line 150. On this basis, calculations of battery degradation were made. The following battery lifespans were achieved:

Figure 7.

An example of daily battery load on the bus serving the 150 route. Source: own study based on the data collected from the bus operator in Gdynia (PKA sp. z.o.o.).

- Battery 258 kWh NMC: 4.36 years;

- Battery 100 kWh LTO: 9.9 years.

Over the entire life cycle of an urban bus, it can be assumed that the use of NMC technology would necessitate two battery replacements, whereas LTO technology would typically require only one replacement.

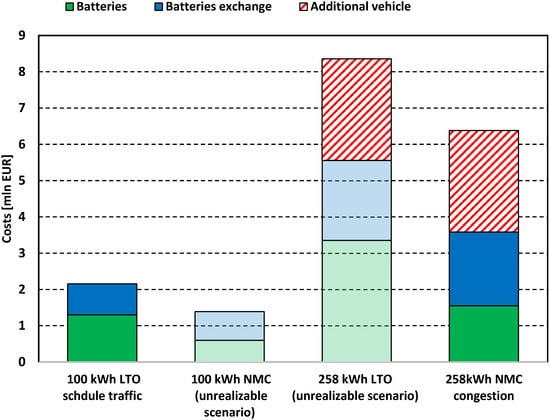

4.4. Impact of Road Traffic Congestion on Battery Costs in Electric Buses

The foregoing analysis leads to the conclusion that the road conditions under which urban buses are operated exert measurable and quantifiable financial effects on the total operating costs of bus systems. Figure 1 illustrates the multidimensional nature of this impact. The subsequent discussion focuses on a single aspect of this issue, namely, the costs of purchasing and replacing traction batteries. An analytical ceteris paribus assumption is adopted to isolate the phenomenon under study from other variables, which are treated as constant. To quantify the consequences of congestion, the TCO of batteries was estimated for two scenarios:

Scenario 1. Operation of buses under road congestion, necessitating the use of higher-capacity batteries, i.e., 258 kWh in NMC technology. In this scenario, deploying LTO batteries is irrational due to their relatively low energy density which, at high capacities (e.g., 258 kWh), results in excessive pack mass and volume, potentially leading to axle load limit exceedances, installation space constraints, and reduced passenger capacity.

Scenario 2. Operation of buses under priority traffic conditions, i.e., without road congestion (e.g., on designated bus lanes). In this scenario, it is feasible to use lower-capacity batteries, i.e., 100 kWh (and thus lower mass) while delivering the same level of operational work as in Scenario 1. In addition, this scenario allows for the use of LTO batteries which, compared with NMC, feature higher specific power, very high cycle life, high allowable charge/discharge currents (high C-rate), superior thermal stability, and a wider operating temperature range.

The TCO of traction batteries in both scenarios was calculated using the formula presented below.

- N—number of busesr—annual discount rateα—annual battery price decline ratebattery pack price today (EUR),—current battery price per kWh (EUR/kWh).C—battery capacity (kWh).

The TCO calculation results for both scenarios are presented in Figure 8. It should be noted that in the non-optimal scenario (assuming the use of 258 kWh NMC batteries), the total battery cost is more than twice as high as in the optimal scenario, which allows for 100 kWh LTO batteries. The figure also shows the cost of an additional vehicle required to maintain service on the route due to congestion-induced delays. The results unambiguously demonstrate that road traffic conditions materially affect the operating costs of urban bus transport systems. The analysis indicates that even for a single route operated by only 10 battery-electric buses (BEBs), differences in total cost of ownership (TCO), attributable to battery cost differentials with other variables held ceteris paribus, may amount to several million euros. These differences would be even larger if the analysis encompassed all bus routes for which bus-priority measures over private cars can be implemented.

Figure 8.

Costs of batteries for 10 vehicles in operation (assumed, NMC and LFP battery price 600 €/kWh, LTO battery price 1300 €/kWh). Source: own study based on the data collected from the bus operator in Gdynia (PKA sp. z.o.o.) and [28].

The figure further depicts results for two theoretical scenarios (i.e., 100 kWh NMC and 258 kWh LTO). Although these scenarios are not feasible in practice—due to the excessively rapid degradation of low-capacity NMC batteries necessitating frequent charging and the prohibitive price, mass, and volume of 258 kWh LTO batteries—they help visualize the influence of individual variables on the final outcome. They thus enable a clearer understanding of the extent to which changes in battery technology and capacity, considered separately, shape the results for the two baseline scenarios (100 kWh LTO and 258 kWh NMC) that are feasible for real-world implementation.

From the standpoint of costs associated with purchasing and replacing traction batteries after their first life cycle, beyond capacity, the key determinant is the unit price (per 1 kWh) specific to each battery technology. This parameter varies over time and across regions due to country-specific economic, technological, and regulatory conditions. In practice, battery prices are also influenced by order size (procurement scale), payment terms, delivery lead times, and other contractual factors.

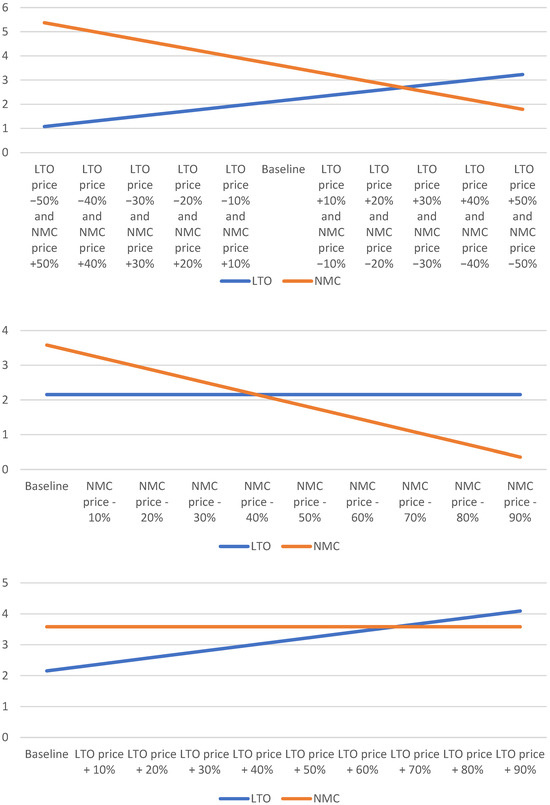

Accordingly, a sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine the magnitude of price changes in LTO and NMC batteries that would equalize costs across the two analyzed scenarios. The results are presented in Figure 9. They indicate that, for the TCO of the 100 kWh LTO and 256 kWh NMC variants to be equal, the price of NMC batteries would need to decrease by approximately 40% relative to the baseline, assuming the LTO price remains unchanged. TCO parity would also occur under a simultaneous 25% decrease in NMC prices and 25% increase in LTO prices, or under an approximate 70% increase in LTO prices with NMC prices held at the assumed level. These figures illustrate the scale of price shifts capable of reversing the preferred option, thereby eroding the savings made possible by deploying lower-capacity batteries in an alternative technology thanks to bus-priority measures in urban traffic.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity analysis of battery costs in the two analyzed scenarios with respect to the prices of individual battery technologies (€/kWh). Source: own study.

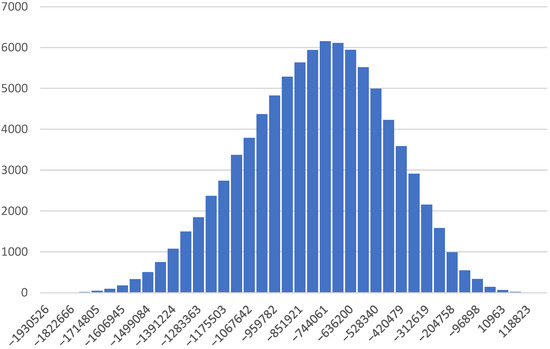

Given that the final TCO of traction batteries in the two analyzed scenarios depends on more variables than the unit battery price alone, a Monte Carlo analysis was conducted based on the assumptions presented in Table 4. Among the considered cases were scenarios anticipating a rapid and pronounced decline in NMC battery prices and, to a lesser extent, LTO prices.

Table 4.

Assumptions adopted for the Monte Carlo analyses of the total cost of ownership (TCO) of traction batteries.

The Monte Carlo approach enabled: the derivation of the probability distribution of TCO values, the estimation of TCO percentile ranges (P5–P95), and the assessment of the probability that the scenario with bus-priority operations (i.e., free-flow traffic) using 100 kWh LTO batteries yields a lower TCO than the congestion scenario employing 258 kWh NMC batteries.

The results of the Monte Carlo analyses of the TCO for traction batteries, presented in Table 5, indicate that the probability of the scenario in which operation under road congestion (286 kWh NMC) is less expensive (i.e., exhibits a lower TCO) than the alternative scenario with bus-priority operations (100 kWh LTO) is exceedingly low (0.05%). For such an outcome to materialize, all of the most favorable changes in the considered variables for the NMC scenario would need to occur simultaneously with all of the most adverse changes for the LTO scenario. This would entail, inter alia, a substantial decline in NMC battery prices with LTO prices remaining unchanged, a service life for NMC batteries longer than assumed, and a shorter-than-assumed service life for LTO batteries.

Table 5.

Results of the Monte Carlo analysis of the total cost of ownership (TCO) of traction batteries.

Conversely, the data shown in Figure 10 suggest that, under the adopted assumptions, the most probable outcome remains cost savings on the order of several hundred thousand euros per single bus route (10 buses) due to bus-priority measures. This result holds despite the adoption of assumptions relatively favorable to NMC battery prices.

Figure 10.

Distribution of Monte Carlo results for the TCO difference: LTO–NMC (€). Source: own study.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

This paper provides quantitative assessments of how road traffic congestion affects the required battery capacity and the battery TCO of BEBs using real operational data from an urban bus route. The analysis showed a significant impact of road traffic congestion on the required battery capacity. The OPP system allows for a substantial reduction in battery capacity. However, due to congestion, there are considerable delays in reaching the final stop, which shortens the stopping time and, consequently, the time available for charging. Based on the analyses conducted, it can be concluded that congestion causes the need to increase capacity even three or four times. This requirement generates significant financial consequences, both at the procurement stage and during subsequent operation, when depleted batteries must be replaced. As demonstrated, in the scenario requiring higher-capacity batteries (258 kWh), battery-related costs can be up to twice as high as in the scenario assuming the use of lower-capacity batteries (100 kWh). Under difficult road conditions, additional buses are also needed to ensure reliable service, whereas such extra vehicles are not required when traffic flows smoothly and timetables are met. The costs of acquiring these additional vehicles may be comparable to the costs of the batteries themselves.

Apart from the need to increase the battery capacity, road traffic congestion limits the choice of technology, e.g., the inability to use LTO technology. As a result, operators do not select battery systems solely based on a broad set of criteria such as price, durability (number of cycles), weight and energy density, charging rate, energy efficiency or environmental performance; instead, they must limit choices to technologies that can operate reliably under often non-optimal traffic conditions in a specific city.

One way to enhance the reliability of BEB charging is the use of dynamic charging from trolleybus traction infrastructure. In this case, road congestion has a much smaller impact on the charging process and may even increase charging opportunities if delays occur on sections equipped with overhead lines. Consequently, road traffic conditions are among the key variables that should be taken into account when designing a new traction network or extending an existing one. At the same time, numerous established measures can improve bus traffic flow in mixed traffic and on dedicated corridors, including bus lanes, signal priority, special bus corridors, dynamic traffic management systems that prioritize public transport, as well as tram and trolleybus infrastructure and bus rapid transit (BRT) systems [40,41].

In the context of the above considerations regarding the operating costs of bus systems, it is important to emphasize that these systems are generally not self-financing. In most European cities, revenues from ticket sales typically do not fully cover the costs of providing public transport services [42,43]. A further decline in revenue coverage would inevitably lead to the implementation of at least one of the following scenarios [17]:

- an increase in bus ticket prices,

- a reduction in the supply of bus transport services,

- an increase in subsidies from municipal budgets.

All of these outcomes should be considered unfavorable in terms of achieving the objectives of sustainable urban development. Minimizing operating costs, including those of zero-emission fleets, is thus an important policy objective. As shown in this article, improving bus traffic flow contributes to cost reduction in several ways: by lowering the required battery capacity, enabling the use of alternative battery technologies, increasing vehicle and driver utilization, and reducing the number of buses needed to maintain a given service frequency. Policymakers are therefore encouraged to implement measures improving urban bus traffic flow, especially on routes operated by electric vehicles.

The scholarly literature offers a broad discussion of how to ensure the efficient operation of BEBs under real urban conditions. Studies highlight the importance of smooth speed profiles, limited hard accelerations, effective use of regenerative braking, and maintaining vehicle speeds within a narrow band for energy efficiency and battery health [44,45]. Additional savings can be obtained through vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communication, optimized vehicle scheduling and sophisticated charging strategies that jointly reduce energy costs and battery degradation [46,47,48]. Electric bus systems operating on routes with stable passenger flows, frequent departures and limited congestion can spread fixed infrastructure and vehicle costs over more vehicle-kilometers and operating hours, lowering TCO per bus-kilometer [12,18,49]. Our findings complement this body of work by showing that congestion-driven constraints on charging time can decisively shape required battery capacity and TCO, even when energy consumption per kilometer is well managed. At the same time, methodological heterogeneity, different local cost structures and varying operational contexts make it difficult to compare results directly. Future research would benefit from a more standardized methodological framework and greater openness in data sharing, enabling more systematic cross-study comparisons.

The considerations presented in this article are subject to several limitations. First, the operational data used come from a single bus route in a single city, Gdynia (Poland). Consequently, the findings are not fully representative or universally applicable to other bus systems. This constraint warrants caution when generalizing beyond the studied context, as the calculations reflect local characteristics: road conditions, topography, weather and climate, organizational arrangements, and passenger-demand patterns.

Additional limitations arise from restricting the data source to one route, which entails a risk of selection bias: speed profiles, traffic intensity, stop spacing, passenger loads, and charging strategies may differ substantially on other lines. To mitigate this risk, the authors purposefully selected a route that does not materially and obviously deviate from the remaining lines in Gdynia’s bus network. Moreover, the temporal horizon and seasonality of the data (variation in temperature, weather, and demand) affect energy consumption and battery degradation, and thus the TCO of batteries. To limit this effect, the analysis covered the entire year 2023 and the beginning of 2024; however, it cannot be ruled out that this period does not fully reflect typical conditions.

To strengthen the validity and generalizability of future research, it is advisable to expand the sample to include multiple routes with diverse characteristics (e.g., route length, elevation profile, stop density, load levels), ideally also spanning multiple cities and countries. Such an approach would simultaneously enable the collection of operational data for a broader set of vehicle models; batteries at varying states of health; different charging-infrastructure configurations; a wider range of charging schedules; and alternative strategies regarding depth of discharge.

In sum, despite the stated limitations, the results consistently indicate that road conditions, particularly congestion reduction through bus-priority measures, are a key determinant of the TCO of batteries in electric buses. Incorporating measures that improve traffic flow into the portfolio of public-transport decarbonization interventions can yield tangible financial savings and operational benefits while enhancing service reliability and attractiveness. The resources saved could be allocated to increasing the supply of public-transport services, which may in turn stimulate further growth in demand. Further empirical studies, conducted on larger and more diverse samples and employing a standardized methodology, will help refine the magnitude of effects and produce guidance that is transferable across urban contexts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., A.J. and M.W.; methodology, M.B., A.J. and M.W.; software, M.B.; validation, M.B.; formal analysis, M.B.; investigation, M.B., A.J. and M.W.; resources, data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B., A.J. and M.W.; writing—review and editing, M.B., A.J. and M.W.; visualization, M.B.; supervision, M.B. and M.W.; project administration, A.J.; funding acquisition, M.B., All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support of these studies from Gdańsk University of Technology by the DEC-01/2/2023/IDUB/II.1/Am–‘Excellence Initiative–Research University’ program is gratefully acknowledged.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request. The datasets were obtained from the operational records of a bus transport operator and are not publicly available due to confidentiality and contractual restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to PKA sp. z.o.o. for providing access to the operational data of the electric bus fleet in service. During the preparation of this study, the author(s) used ChatGPT (OpenAI), chatgpt.com (access date: 5 October 2025) to improve English grammar, spelling, and style; no scientific conclusions were generated by the tool. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BEB | battery electric bus |

| BMS | battery management system |

| DB | diesel bus |

| DoD | depth of discharge |

| IMC | in-motion charging |

| kWh | kilowatt-hour |

| LTO | lithium-titanate |

| NMC | nickel-manganese-cobalt |

| ONC | overnight charging |

| OPP | opportunity charging |

| PLN | Polish Zloty |

| SoC | state of charge |

| TCO | total cost of ownership |

References

- Manzolli, J.A.; Trovão, J.P.; Antunes, C.H. A Review of Electric Bus Vehicles Research Topics—Methods and Trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, S.S.G.; Lusby, R.M.; Larsen, J. Electric Bus Planning & Scheduling: A Review of Related Problems and Methodologies. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2022, 301, 395–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borén, S. Electric Buses’ Sustainability Effects, Noise, Energy Use, and Costs. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2020, 14, 956–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.L.P.; Seixas, S.R.C. Battery-Electric Buses and Their Implementation Barriers: Analysis and Prospects for Sustainability. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2022, 51, 101896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagiełło, A. Economic Efficiency of Sustainable Public Transport: A Literature Review on Electric and Diesel Buses. Energies 2025, 18, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Shon, H.; Papakonstantinou, I.; Son, S. Optimal Fleet, Battery, and Charging Infrastructure Planning for Reliable Electric Bus Operations. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2021, 100, 103066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basma, H.; Mansour, C.; Haddad, M.; Nemer, M.; Stabat, P. Energy Consumption and Battery Sizing for Different Types of Electric Bus Service. Energy 2022, 239, 122454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamodt, A.; Cory, K.; Coney, K. Electrifying Transit: A Guidebook for Implementing Battery Electric Buses. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/docs/fy21osti/76932.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Szürke, S.K.; Saly, G.; Lakatos, I. Analyzing Energy Efficiency and Battery Supervision in Electric Bus Integration for Improved Urban Transport Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, T.; Blades, L.; Early, J.; Harris, A. UK Battery Electric Bus Operation: Examining Battery Degradation, Carbon Emissions and Cost. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2022, 109, 103373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Meng, Q.; Ong, G.P. Electric Bus Charging Scheduling for a Single Public Transport Route Considering Nonlinear Charging Profile and Battery Degradation Effect. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2022, 159, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Lin, X.; He, F. Robust Scheduling Strategies of Electric Buses under Stochastic Traffic Conditions. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 105, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaeilnejad, S.; Kattan, L.; Wirasinghe, S.C. Optimal Charging Station Locations and Durations for a Transit Route with Battery-Electric Buses: A Two-Stage Stochastic Programming Approach with Consideration of Weather Conditions. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 156, 104327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, A.; Chen, S.; Shi, D.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C. A Review on Electric Bus Charging Scheduling from Viewpoints of Vehicle Scheduling. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, 13–16 December 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ye, B.; Wang, S.; Ma, Y. Analysis and Estimation of Energy Consumption of Electric Buses Using Real-World Data. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2024, 126, 104017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, S.P.; Mansur, E.T.; Muller, N.Z.; Yates, A.J. The Environmental Benefits of Transportation Electrification: Urban Buses. Policy 2021, 148, 111921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagiełło, A. Elektromobilność w Kształtowaniu Rozwoju Drogowego Transportu Miejskiego w Polsce; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdañskiego: Gdańsk, Poland, 2021; ISBN 978-83-8206-186-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Hartmann, N.; Zeller, M.; Luise, R.; Soylu, T. Comparative Tco Analysis of Battery Electric and Hydrogen Fuel Cell Buses for Public Transport System in Small to Midsize Cities. Energies 2021, 14, 4384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghetti, F.; Longo, M.; Bonera, M.; Libretti, M.; Somaschini, C.; Martinelli, V.; Medeghini, M.; Mazzoncini, R. Battery Electric Buses or Fuel Cell Electric Buses? A Decarbonization Case Study in the City of Brescia, Italy. Infrastructures 2023, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Z.; Song, L.; De Kleine, R.; Mi, C.C.; Keoleian, G.A. Plug-in vs. Wireless Charging: Life Cycle Energy and Greenhouse Gas Emissions for an Electric Bus System. Appl. Energy 2015, 146, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Földes, D.; Csonka, B.; Szilassy, P.Á. Urban Bus Network Electrification. In Transportation Engineering; Obregón Biosca, S.A., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Alwesabi, Y.; Liu, Z.; Kwon, S.; Wang, Y. A Novel Integration of Scheduling and Dynamic Wireless Charging Planning Models of Battery Electric Buses. Energy 2021, 230, 120806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uslu, T.; Kaya, O. Location and Capacity Decisions for Electric Bus Charging Stations Considering Waiting Times. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2021, 90, 102645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, K. Battery Electric Bus Infrastructure Planning under Demand Uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 111, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basma, H.; Haddad, M.; Mansour, C.; Nemer, M.; Stabat, P. Evaluation of the Techno-Economic Performance of Battery Electric Buses: Case Study of a Bus Line in Paris. Res. Transp. Econ. 2022, 95, 101207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itani, K.; De Bernardinis, A. Review on New-Generation Batteries Technologies: Trends and Future Directions. Energies 2023, 16, 7530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ager-Wick Ellingsen, L.; Jayne Thorne, R.; Wind, J.; Figenbaum, E.; Romare, M.; Nordelöf, A. Life Cycle Assessment of Battery Electric Buses. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2022, 112, 103498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebküchner, M.; Hans-Jörg, A. E-Bus-Strategie Schlussbericht, Zürich, Switzerland. 2019. Available online: https://www.vvl.ch/application/files/7516/1910/0474/20190404_Bericht_E-Bus-Strategie-VVL_final.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Mahmoudi, R.; Saidi, S.; Wirasinghe, S.C. A Critical Review of Analytical Approaches in Public Bus Transit Network Design and Operations Planning with Focus on Emerging Technologies and Sustainability. J. Public Transp. 2024, 26, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avishan, F.; Yanıkoğlu, İ.; Alwesabi, Y. Electric Bus Fleet Scheduling under Travel Time and Energy Consumption Uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 156, 104357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central Statistical Office Local Data Bank. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Wołek, M.; Hebel, K. Strategic Planning of the Development of Trolleybus Transportation Within the Cities of Poland. In Smart and Green Solutions for Transport Systems, Proceedings of the 16th Scientific and Technical Conference Transport Systems. Theory and Practice, Selected Papers, Katowice, Poland, 16–18 September 2019; Sierpinski, G., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-35543-2. [Google Scholar]

- Bielski, P.; Józefowicz, M.; Wyszomirski, O. Gdyńskie Trolejbusy. Rozwój Gdyńskiej Komunikacji Trolejbusowej w Latach 1943–2023; Księży Młyn: Łódź, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- BDP Gdynia. Urząd Miasta Gdyni Raport o Stanie Miasta Gdyni Za Rok 2023; BDP Gdynia: Gdynia, Poland, 2024; Available online: https://www.um.gdynia.pl/module/Files/controller/Default/action/downloadFile/hash/2600e65b4c8eb6e17bb925313a2dae21.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Wołek, M.; Wolański, M.; Bartłomiejczyk, M.; Wyszomirski, O.; Grzelec, K.; Hebel, K. Ensuring Sustainable Development of Urban Public Transport: A Case Study of the Trolleybus System in Gdynia and Sopot (Poland). J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, J.N.; Sturmberg, B.C.P. An Integrated Model of Electric Bus Energy Consumption and Optimised Depot Charging. npj Sustain. Mobil. Transp. 2024, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gairola, P.; Nezamuddin, N. Design of Battery Electric Bus System Considering Waiting Time Limitations. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2677, 1415–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, C.L.; Arbelaez, A.; Climent, L. Robust EBuses Charging Location Problem. IEEE Open J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 3, 856–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, D.; Ban, X. Optimal Locations and Sizes of Layover Charging Stations for Electric Buses. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 152, 104157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danaher, A.R. Bus and Rail Transit Preferential Treatments in Mixed Traffic. A Synthesis of Transit Practice; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, P.; Walk, M.J.; Simek, C. Transit Signal Priority: Current State of the Practice. A Synthesis of Transit Practice; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- International Transport Forum. The Future of Public Transport Funding; International Transport Forum: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- EMTA. 2024 EMTA BAROMETER on Public Transport in Metropolitan Areas; EMTA: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Lu, C.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Bi, J.; Zhao, X. Understanding the Energy Consumption of Battery Electric Buses in Urban Public Transport Systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamarikas, S.; Doulgeris, S.; Samaras, Z.; Ntziachristos, L. Traffic Impacts on Energy Consumption of Electric and Conventional Vehicles. Transp. Res. D Transp. Environ. 2022, 105, 103231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, W.D.; Wang, Y.; Malikopoulos, A.A.; Advani, S.G.; Prasad, A.K. Impact of Connectivity on Energy Consumption and Battery Life for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2021, 6, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, M. Optimal Electric Bus Scheduling Considering Battery Degradation Effect and Charging Facility Capacity. Transp. Lett. 2025, 17, 491–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Jin, K.; Qin, S. Joint Optimization of Vehicle Scheduling and Charging Strategies for Electric Buses to Reduce Battery Degradation. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2024, 16, 044704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grauers, A.; Borén, S.; Enerbäck, O. Total Cost of Ownership Model and Significant Cost Parameters for the Design of Electric Bus Systems. Energies 2020, 13, 3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).