1. Introduction

For interconnected power grid secondary frequency regulation or automatic generation control (AGC), appropriate evaluation standards are required to assess and standardize the performance of control areas, and they can ensure both system reliability and equitable sharing of benefits from grid interconnection [

1,

2,

3]. The A1 and A2 standards (collectively known as the A standard) were introduced in North America’s power grids during the 1960s. They represent early evaluation benchmarks for interconnected grid control performance. China’s regional grids began adopting A standard for grid interconnection control performance evaluations in the mid-to-late 1980s, with the North China power grid continuing their use to this day. However, years of practical application have revealed shortcomings in the A standard: it fails to account for smooth (positive) effects between area control error (ACE) and it lacks long-term consideration of frequency control quality [

4,

5,

6]. The A1 standard requires the ACE’s frequent zero-crossing, which unnecessarily increases unnecessary unit adjustments. The A2 standard strictly limits the average ACE over specific time periods, making it ineffective in utilizing mutual support among control areas during disturbances.

In 1997, the North American Electric Reliability Council (NERC) introduced the control performance standard (CPS) [

7]. In 2001, the East China power grid became the first to adopt the CPS as an alternative to the original A standard, with modifications made [

8]. Subsequently, power grids in Central China and Northeast China also began implementing the CPS for regional control performance evaluations, developing and establishing corresponding evaluation criteria [

9]. Since its introduction, the CPS has been widely adopted both domestically and internationally. It has achieved significant success and has served as the mainstream evaluation benchmark for interconnected power system operations in China [

10,

11,

12].

Compared to the A standard that was developed based on operational experience, the CPS has a more solid theoretical foundation, with its derivation grounded in rigorous statistical theories [

13,

14]. Unlike the A standard’s bottom-up design approach, the CPS focuses on achieving qualified frequency control. During the design process, it examines the relationship between ACE and frequency in control areas, following a logical sequence: “system frequency reaching qualified target values → considering the relationship between overall system ACE and frequency → analyzing the relationships between ACE and frequency in individual control area → setting ACE control requirements for each area”. This methodology incorporates three principles: “fairness and scientific rigor”, “balancing economic considerations”, and “reasonable allocation of frequency regulation responsibilities”. Therefore, it can scientifically guide the operational behaviors of control areas [

15].

Under the traditional tie-line power and frequency bias control (TBC) model, the CPS assumes that the entire power grid can be divided into roughly identical units with essentially similar configurations between control areas, differing only in scale. This allows the determining of evaluation thresholds for control areas through frequency deviation coefficients and the clarifying of their frequency regulation responsibilities [

16,

17]. However, with the increasing integration of high-proportion new-energy sources, differences in the power source mix across control areas within interconnected systems have grown significantly [

18,

19]. Some control areas now feature substantial increases in new-energy installations while conventional generation units decrease. This has led to the original assumption of uniform power structure across control areas in the CPS no longer being valid. When calculating evaluation thresholds for these control areas based on this assumption, the CPS fails to account for the variations in frequency regulation demands and control capabilities caused by differing power structures. So, it is inadequate for control areas with high-proportion new energy.

The CPS was originally designed to evaluate active power control performance in interconnected grids dominated by conventional, controllable generation sources. Its framework is based on traditional power systems where dispatchable generation tracks load variations. And it does not account for the rapidly increasing heterogeneity in generation mix among control areas following the integration of a high proportion of new energy. This oversight compromises the standard’s original evaluation effectiveness.

Some modifications have been proposed to address the shortcomings of CPS in high-proportion new-energy power systems. For instance, in the context of large-scale centralized wind power integration, an enhanced CPS (ECPS) model is proposed [

20]. It considers the uneven distribution of frequency regulation resources across interconnected grids. In [

21], an adaptive standard with dynamically adjustable thresholds is proposed. It allows for adapting the frequency response responsibility factor of control areas to adjust the evaluation threshold. These improved methods aim to mitigate the impact of unevenly distributed regulation resources on the evaluation standard. However, they do not explicitly and sufficiently incorporate the inherent objective differences in the generation mix of control areas into the direct determination of evaluation thresholds. Furthermore, it is worth noting that in practical power grid operation, the CPS evaluation threshold should not be adjusted frequently. Frequent changes would pose significant challenges to the consistent implementation of an evaluation standard.

To address the incompatibility of existing CPS in high-proportion new-energy power systems, this paper proposes an improved version of the CPS. It determines evaluation thresholds based on objective power source structures in control areas. This study first analyzes the assumptions and principles of the existing CPS, revealing its limitations in high-proportion new-energy systems. Subsequently, the concept of inherent area control error (ACE) standard deviation is proposed to determine evaluation thresholds, forming an improved CPS methodology. Then, the proposed improvement method is compared with the original CPS, with detailed comparisons of frequency regulation responsibility allocation between the two standards. Finally, the case studies show that the refined approach ensures greater fairness and rationality compared with the original CPS.

2. The Assumption and Inadaptability of CPS

2.1. Introduction of CPS

The CPS consists of two sub standards, CPS1 and CPS2, which are derived based on strict statistical theories. In the derivation of the CPS, ACE is a random variable, and the derivation of the domestic CPS is based on the following four assumptions.

- (1)

The mean value of ACE in each control area is 0;

- (2)

The correlation coefficient between ACE in each control area is 0;

- (3)

ACE in each control area is normally distributed;

- (4)

Each control area is homogeneous; the power supply structure and load composition are basically the same.

The CPS requires that the root mean square value of the frequency deviation in the interconnected grid be within the control target range:

is the frequency deviation; is the control target value of the interconnection grid frequency deviation, unit of Hz; is the function to calculate the root mean square; and is the function to calculate the average.

To ensure fair regulation of the root mean square value of frequency deviation within control targets, CPSs classify interconnected systems into M homogeneous units under assumption 4, where each unit shares identical characteristics. Control areas are then composed of multiple homogeneous units, differing only in scale. For each homogeneous unit,

In (2), M represents the number of homogeneous units the interconnected system is divided into; is the frequency deviation coefficient for the -th unit, which is taken as positive in this paper, reflecting the frequency regulation characteristics of primary frequency regulation in control areas or homogeneous units. This coefficient encompasses both generators’ set primary frequency regulation and load frequency regulation effects, with unit in MW/Hz.

In this case, the requirement of (1) can be converted to the following:

In (3), is the sum of the frequency deviation coefficients of all homogeneous units, and is the ACE of the -th unit.

Since each unit is homogeneous, combined with the assumption that the mean value of ACE in the control area is 0, the total mean value of ACE in the system and the mean value of ACE in each homogeneous unit are also 0. Therefore, the control requirements for the system frequency can be evenly distributed to each unit:

Suppose the system has N control areas. Taking a sub-control area

which contains L homogeneous units (L < M) as an example, the ACE of the control area is the sum of the ACE of the L units, and the frequency control requirement of the control area

can be obtained by superimposing the frequency requirements of the L units:

In (4), is the frequency deviation coefficient of the control area , which is equal to the sum of the frequency deviation coefficients of L homogeneous units; is the regional control deviation of the control area, which is equal to the sum of the regional control deviations of L homogeneous units.

When the ACE control in each control area satisfies (5), it can be concluded that the system’s frequency control complies with (1), which holds strictly mathematically. Based on this premise that the correlation coefficients between ACE in different control areas are zero, as stated in assumption 2, the range requirements for the ACE in the control area

can be derived from (5) as follows:

According to assumption 1, the root mean square value and standard deviation of ACE in each control area are equal. Combined with assumption 3 that ACE in the control area is normally distributed, the target value of ACE qualification rate meeting the requirement of more than 90% is obtained as follows:

Because the architecture of China’s power grid is different from that of North America’s, some modifications are made to the above derivation results when introducing CPS1 and CPS2 standards. China’s CPS1 standard formula adopts a short-term average of 10 min or 15 min. Taking 15 min as an example, the CPS1 standard requires that the indicators in the control area

of the interconnected power grid meet:

In (8), the subscripts 1 min and 15 min, respectively, represent the average values of the corresponding data within 1 min and 15 min in this paper; is the average value of ACE in the control area within 1 min; is the average frequency deviation of 1 min, which is the control target value of the root mean square of the annual average frequency deviation of the interconnected power grid, and the unit is Hz.

The CPS2 standard is used to evaluate the ability of a control area to control the power flow deviation of the contact line. The domestic CPS2 standard requires that each control center should control the real-time generation power in its own area, so that the average value of ACE every 15 min must be controlled within the specified range:

In (9), is the 15 min average value of ACE in the control area ; is the control target value of the root mean square of the annual 15 min average frequency deviation of the interconnected power grid, the unit is Hz; is the evaluation threshold of the 15 min average of ACE.

2.2. Inadaptability of CPS

As established in the previous section, the mathematical derivation of the CPS is grounded in specific assumptions. Both sub-standard derivations utilize assumption 1, while CPS2 extends this by incorporating assumption 2 and 3. Assumption 4 serves as a prerequisite ensuring the equitable distribution of frequency regulation responsibilities across control areas. The CPS derives from frequency target values, allocating frequency regulation responsibilities to control areas based on their deviation coefficients under assumption 4. Provided that the ACE in each control area meets the CPS requirements, the system’s frequency can achieve the desired targets.

However, in high-proportion new-energy power systems, control areas face dual challenges. On one hand, their power structures exhibit significant variations. Some control areas have higher new-energy installations and lower conventional unit capacity, requiring substantial regulation demands but lacking sufficient control capabilities. On the other hand, the inherent volatility of new-energy and its unpredictable nature leads to increasingly severe frequency fluctuations in both systems and transmission line power variations. These two hands pose substantial challenges for frequency control and tie-line power regulation. Traditional evaluation standards under TBC mode still operate under a siloed evaluation framework. Therefore, they fail to adequately address the mismatch between control areas’ capabilities and actual frequency regulation demands caused by structural differences in power sources. It may be effective when the control areas have sufficient regional control resources and minor system imbalances. However, these approaches prove inadequate for guiding optimal resource allocation across interconnected systems or fairly distributing frequency regulation responsibilities among control areas in high-proportion new-energy scenarios. So, their limitations become increasingly apparent. Specifically, regarding CPSs, the growing structural disparities among control areas render the homogeneity assumption (assumption 4) invalid, severely compromising the fairness of existing CPSs when establishing evaluation thresholds and distributing frequency regulation responsibilities.

To demonstrate the inadequacy of CPSs, consider a two-area interconnected power system in

Figure 1, where both control areas employ TBC mode. Initially, control area A and control area B are identical in structure, load supply configurations, and control levels, resulting in identical evaluation outcomes under CPS. Building on this foundation, two scenarios are developed:

(1) The control area A has increased its installed capacity of new-energy sources by a significant amount. Due to the random fluctuations and large prediction errors in new-energy generation, the unbalanced power in the control area A has increased, leading to a rise in the standard deviation of the ACE. However, the frequency deviation coefficient in the control area A remains unchanged, and the evaluation threshold under CPSs stays consistent. This indicates that the evaluation results for the control area A have deteriorated. However, this deterioration is not due to a decline in the control level of the control area A, but rather stems from inherent changes in the power supply structure.

(2) Building upon the previous scenario, we further shut down some conventional units in control area A (all AGC units). With the reduction in AGC units, the frequency regulation capability of control area A decreases, leading to a further increase in the ACE’s standard deviation. However, due to the reduced frequency deviation coefficient in control area A, the evaluation threshold under CPSs actually becomes lower. The combined effect of these two factors results in a significant deterioration of control area A’s evaluation outcomes. Similarly, this performance decline is not caused by reduced control levels, indicating that CPS is clearly unfair to control area A.

In summary, when a high-proportion of new-energy sources are integrated, some control areas may exhibit significantly higher installed new-energy capacity compared to others, yet with smaller AGC-regulated unit capacities. This situation invalidates assumption 4. The original CPS failed to account for differences in power source structures when setting evaluation thresholds. A fair and reasonable evaluation metric should fully consider objective and inherent variations in power source structures, focusing on evaluating the effectiveness of active power balance control in control areas. To address this issue, this paper introduces the concept of inherent ACE standard deviation and improves the CPS.

3. The Inherent ACE Standard Deviation

When all control areas in an interconnected system adopt TBC mode, the static analysis shows that the ACE represents regional area power imbalance. This coefficient reflects the power control imbalance after the system’s primary frequency regulation response stabilizes sufficiently, with its steady-state value being solely related to secondary frequency regulation. In cases where control areas are not interconnected or operate asynchronously, imbalance primarily stems from fluctuations in load and new-energy sources within the control area, which are compensated by secondary frequency regulation from conventional units the control area.

The inherent ACE standard deviation is defined as the standard deviation of ACE determined by the inherent conditions of power supply structures across control areas under identical active power balance control levels (including load forecasting, new-energy forecasting, AGC, and AGC unit ramping capability), which is denoted as in this paper. The following section details the specific formula derivation.

First, we analyze the disturbances in control areas, which are primarily generated by fluctuations from three components: load, wind power, and photovoltaic power. The magnitude of these disturbances is mainly influenced by the level of power forecasting accuracy. Other factors such as deviations in scheduled unit execution and planned interpolation of interconnection lines also contribute to disturbances, but are not considered primary influencing factors in this study. We assume that the power disturbances from these three components follow normal distributions with zero mean and are mutually independent. Consequently, the total variance of disturbances equals the sum of individual variances. The magnitude of disturbances in one control area can be regarded as a random variable conforming to a normal distribution with zero mean and positive standard deviation as

, denoted as

. Take the control area

, for example, where the calculation formula is as follows:

In (10), , , are the disturbance standard deviations of wind power, photovoltaic power, and load, respectively, with the unit in MW; , , represent the prediction error coefficients for wind power, photovoltaic power, and load, which maintain consistent values across all control areas within the interconnected system. These coefficients reflect the same control requirements, calculated by dividing the variance of wind power, photovoltaic power, and load prediction errors per minute from the previous year by the system’s total wind power generation, photovoltaic power generation, and load consumption from the previous year. Measured in MW2/100 million kWh, these coefficients indicate the average prediction accuracy of new-energy sources and load in the interconnected system. , , represent the wind power generation, photovoltaic power generation, and load power of the control area from the previous year, measured in 100 million kWh. These values reflect the objective natural conditions inherent to the control area.

The inherent disturbance in a control area (e.g., the control area ) is modeled as a zero-mean normal random variable, whose standard deviation is given in (10). In (10), , , and are inherent parameters of the control area , capturing the objective, innate power generation and load power within the control area. The magnitude settings of , , across all control areas remain consistent. These three prediction error coefficients ensure that the requirement for the wind power, photovoltaic power, and load prediction accuracy is consistent across all control areas in the interconnected power grid. Here, the inherent disturbance standard deviation of each control area is solely determined by its own objective new-energy generation and load consumption. Consequently, the coefficients for each control area can fully reflect the inherent disturbance magnitudes caused by differences in new-energy generation and load power, while maintaining consistent prediction performance requirements for the interconnected system across all control areas.

The following analyzes the secondary frequency regulation compensation in the inherent ACE standard deviation, that is, the effect of AGC unit action on the reduction in power imbalance in a control area. This part is affected by the installed capacity of conventional units in the control area. According to the actual data analysis results, the conventional unit secondary frequency regulation compensation amount has little relationship with the AGC command size and is mainly determined by the generation unit ramping rate limit. The regulation rates are distinguished by hydro and thermal power units. The ramping rate of hydroelectric and thermal power are defined as

and

, and they are the regulation-rate-required coefficient for hydroelectric units and thermal power units, in units of %/min, which can be given according to the requirements of two rules as 20% and 2%. When both hydro and thermal units are responding, the specific definition of the total regulation rate

of the units in control area

is as follows:

In (11), with the unit in MW, and represent the thermal power and hydroelectric installed capacity of AGC units in control area ; and denote the annual adjustable ratio coefficients for thermal and hydroelectric AGC units, indicating the proportion of operational time during the whole year when these units can be adjusted. The total AGC unit regulation rate in control areas is solely determined by the installed capacity as an inherent objective condition. Other coefficients (including , , , ) remain uniform across all control areas, implying that different control areas should achieve equivalent AGC unit management requirements.

The area imbalance and one-unit actual-second frequency regulation compensation is shown in

Figure 2. To facilitate a rough estimation of the AGC unit response, a simplification is made. For long-term statistical analysis, the aggregate effect of random power disturbances can be represented by step signals with random magnitudes. The duration of these step signals should also be randomized; however, this would introduce significant complexity into the computational analysis. Therefore, this paper assumes a uniform step duration, denoted as

. When a power disturbance occurs in the system, it is simplified as a step disturbance. At this time, the unit will receive ramping instructions from the AGC system, and the unit will adjust its output power to reduce the system’s power imbalance. Taking control area

as an example, let

denote the inherent ACE standard deviation over a given period. This coefficient reflects the mean value of the ACE after secondary frequency regulation has compensated for the power imbalance in the control area during that period. By subtracting the average response of conventional units from the actual power disturbance, the inherent ACE standard deviation

of control area

can be calculated, as shown in (12):

In (12), the inherent ACE standard deviation of control area is solely determined by the inherent objective condition (, , , , ). Other coefficients (including , , , , , , ) remain uniform across all control areas, implying that different control areas should achieve equivalent AGC unit management requirements. Consequently, the magnitude of the control area’s inherent ACE standard deviation is solely determined by the objective and inherent conditions of each control area’s generation mix.

4. Improvement Method of CPS

To address the incompatibility of CPS, this section proposes an improvement method for CPS based on inherent ACE standard deviation. The modified CPS maintains the original derivation approach: firstly, given the interconnected power system frequency control objective in (1), derive the ACE control requirements for each control area. Starting from (1), a straightforward derivation shows that this requirement is equivalent to the following formula:

If all control areas satisfy (13), the system frequency control requirements are achieved. When determining the control requirements for each control area in (13), the assumption of homogeneous distribution in the original CPS (assumption 4) no longer holds. Consequently, the frequency control requirements can no longer be allocated proportionally based on the frequency deviation coefficients of each control area relative to the total network. The improved method instead allocates system frequency control requirements to each control area during the distribution process based on the inherent ACE standard deviation. From (13), we can obtain the evaluation threshold of the control area

:

The evaluation threshold for improving the CPS1 standard is determined below. Starting from (14) and considering the relationship between system frequency and ACE in each control area, the frequency control requirement for the control area

is obtained as follows:

Based on (14), the evaluation threshold of the improved CPS2 can be further determined according to assumptions 1 and 3, and the range requirement of ACE in the control area

is obtained as follows:

According to (15) and (16), the evaluation requirements of the improved CPS for the control area

are shown in

Table 1:

Compared with the original CPS, the improved CPS according to the proposed improvement method has the following characteristics:

(1) The revised CPS maintains its original development framework. While the updated methodology retains the ACE calculation mechanism under TBC mode and AGC principles, it just introduces improvements to the evaluation threshold determination process. The revised CPS continues to follow the established logic: “system frequency reaching qualified target values → control requirements for ACE in respective areas”. The key distinction lies in the updated approach: since the homogeneous assumption for each control area no longer holds, the revised standard now allocates frequency regulation responsibilities based on inherent ACE standard deviation, thereby determining evaluation thresholds for each control area.

(2) The enhanced CPS comprehensively addresses the inherent power structure variations across control areas, with a primary focus on evaluating the effectiveness of active power balance control. By establishing evaluation thresholds based on the inherent ACE standard deviation, the revised standard maintains uniform requirements for all control areas regarding active power balance control capabilities, including load forecasting, new-energy power prediction, AGC, and AGC unit performance management. This refined standard fully accommodates the natural power structure differences among control areas while guiding them to enhance control performance under consistent active power balance evaluation criteria.

5. Case Analysis

5.1. Data and Calculation Explanation

The main work of this paper focuses on the improvement of evaluation and evaluation criteria. The purpose of the case study analysis is to verify that the proposed improved standard is fairer and more reasonable, which aligns with the statement: “A fair and reasonable evaluation standard should fully consider the objective and inherent differences in power source structures, and focus on assessing the quality of active power balance control performance of control areas.”

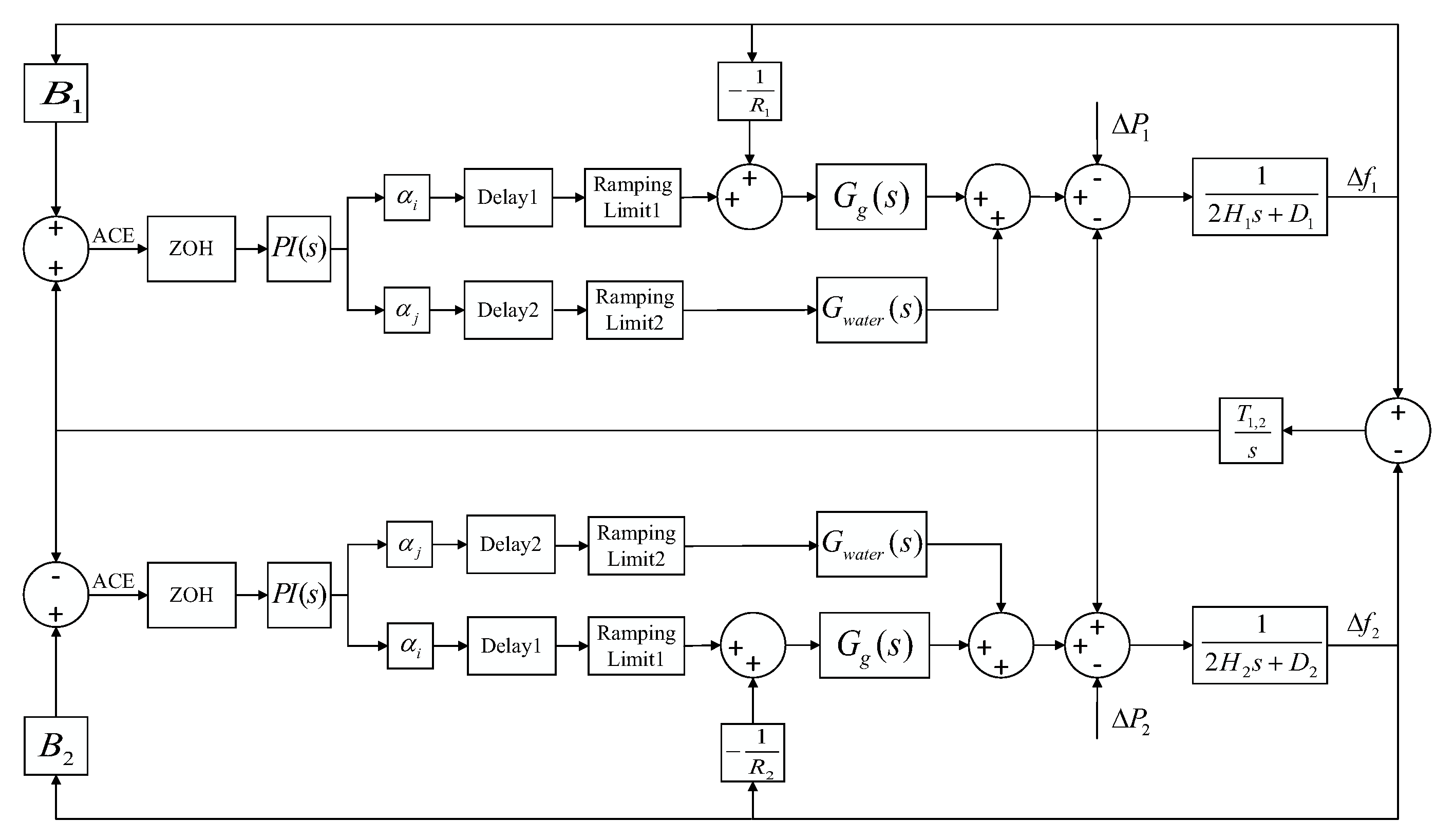

The improved CPS does not directly change the AGC modes of control areas; instead, it just guides control areas to improve their control capabilities. As a result, many aspects cannot be intuitively quantified and compared. To compare the evaluation effects of the improved CPS and the original CPS, the case study designed in this paper starts with two identical control areas (which, by definition, have the same control performance levels). Only the generation mix is subsequently altered, while all other parameters remain unchanged. Consequently, the control performance levels of both areas remain identical throughout the experiment. This setup allows us to evaluate whether the proposed improved CPS yields consistent evaluation results for both areas, thereby verifying the fairness and rationality of the proposed standard. To validate the scientific soundness and fairness of the proposed method, a two-area interconnected power system simulation model was developed in MATLAB/Simulink 2025b, as illustrated in

Figure 3. Initially, the parameters for control area A and control area B were configured to be fully identical in terms of load, generation mix, and active power balance control performance. Detailed parameters of the control areas are provided in

Table 2.

Also, this paper selects the actual evaluation results from the operation of the improved standard in the Northeast China power grid during the period from February to July 2025, and conducts analysis and calculations by combining them with the historical data of the Northeast China power grid for the corresponding period in 2024. All parameters used in this calculation are determined based on the actual parameters of the Northeast China power grid and its grid structure.

This paper’s CPS evaluation criteria are formulated in accordance with the power grid’s CPS evaluation requirements in the Northeast China power grid. The power and frequency control evaluation for interconnection lines adopts a 15 min evaluation cycle, with 96 evaluation points per day. Based on the calculation results of CPS1 and CPS2 indicators, the control performance within a single evaluation point across control areas is classified as Excellent, Good, Medium, or Poor.

- (1)

When the evaluation point satisfies CPS1 ≥ 2, the point is rated as excellent regardless of whether CPS2 is qualified or not.

- (2)

When the evaluation point satisfies 1 ≤ CPS1 < 2 and CPS2 is qualified, that is, the absolute value of the 15 min average ACE is greater than or equal to , the point is rated as good.

- (3)

When the evaluation point satisfies 1 ≤ CPS1 < 2 and CPS2 is unqualified, that is, the absolute value of the 15 min average ACE is less than or equal to , the point is rated as medium.

- (4)

When the evaluation point satisfies CPS1 < 1, the point is rated as poor regardless of whether CPS2 is qualified or not.

The calculation of a single evaluation point across control areas of the improved CPS in the Northeast China power grid is the same as the CPS. In addition, we have compiled a table of the proportion of installed power generation capacity for the Northeast China power grid in

Table 3 (data statistics as of July 2025) to illustrate that, with the integration of a high proportion of new energy, the power source structures of various provincial-level control areas under the Northeast China power grid have actually exhibited significant differences. The “homogeneous power source structure” assumption of the existing CPS no longer holds in the Northeast China power grid. Under the new circumstances, it is highly necessary and timely to study the improvement methods of the CPS. Furthermore, the improved CPS has been applied in the Northeast China power grid since 16 January 2025.

5.2. Comparison Between the Original CPS and the Improved CPS Based on Simulation

The simulation based on the model in

Figure 3 primarily includes the following five aspects:

(1) Evaluation results of the two control areas under daily inherent disturbances, when their loads, generation mix, and active power balance control performance are fully identical.

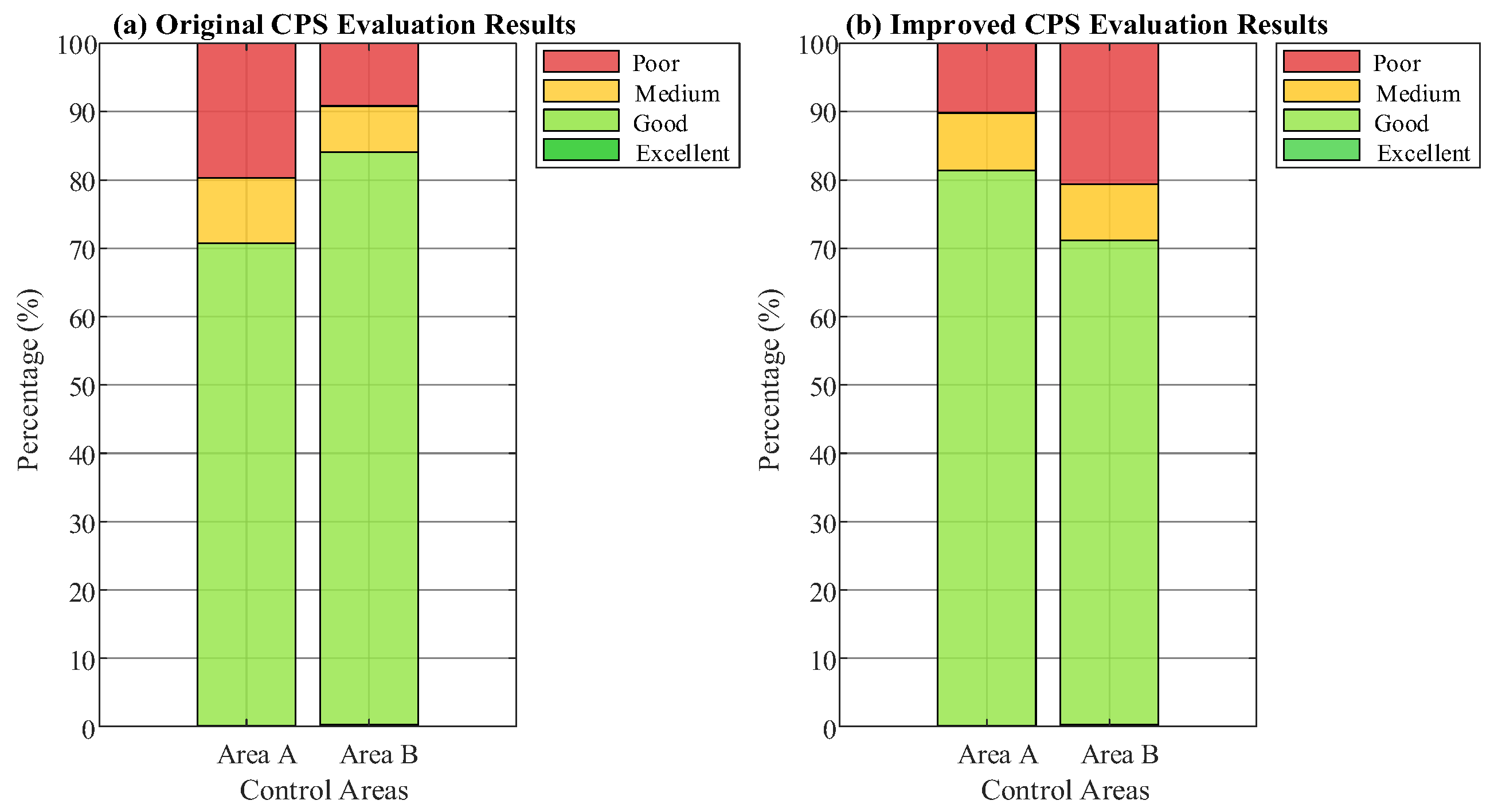

The one-month CPS evaluation results for control areas A and B are shown in

Table 4, under the condition that their load, power supply structures, and active power balance control levels are identical, and a daily inherent random normal disturbance is applied to both areas (the standard deviation of the random normal disturbance in this simulation is calculated based on the power supply structure of the control areas using Equation (10)). The evaluation thresholds for both control areas are set consistently. As shown in

Table 4, the evaluation results for the two control areas under random disturbances differ only slightly, and the results of the improved CPS are entirely consistent with those of the original CPS.

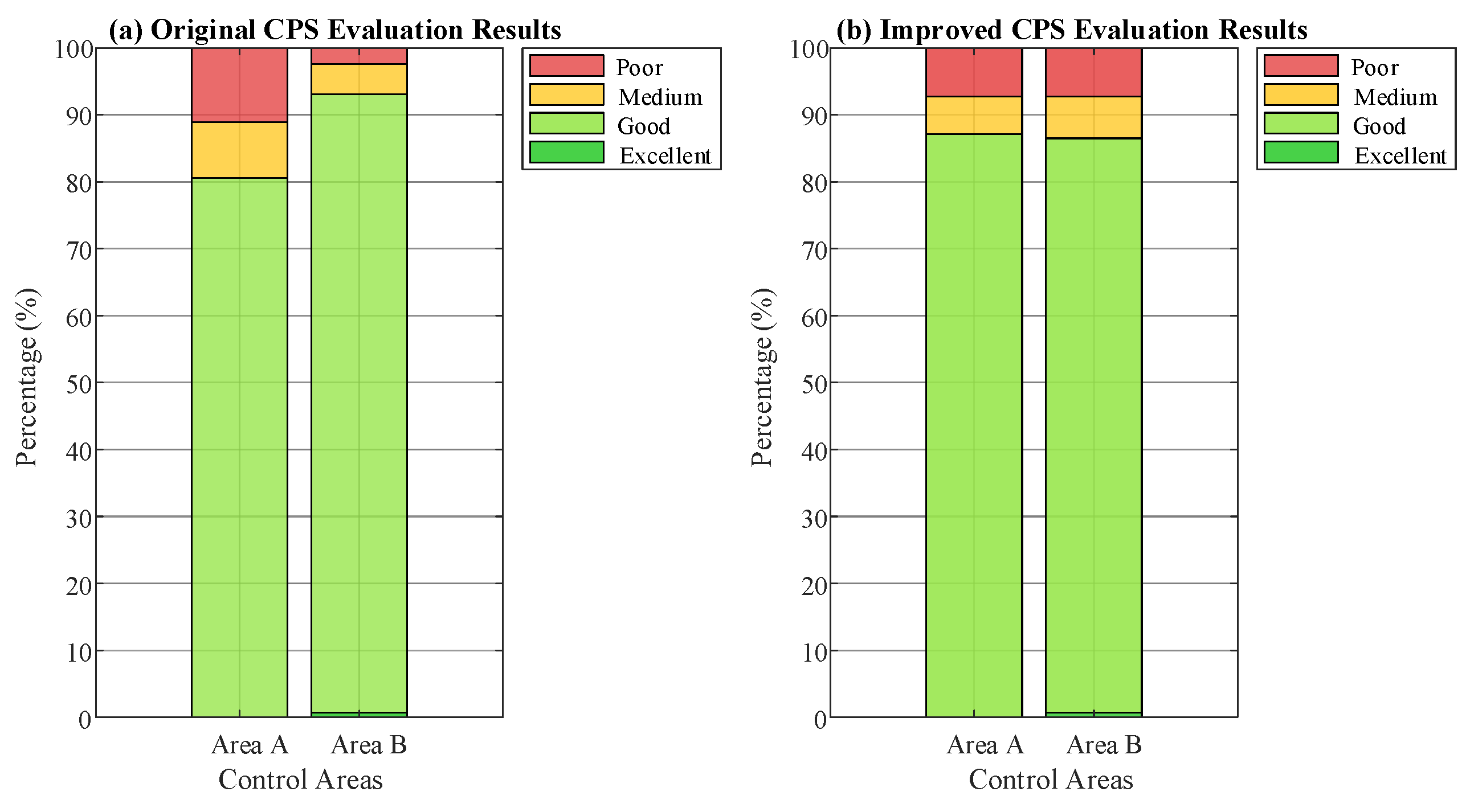

(2) When the proportion of wind power generation and photovoltaic power generation in control area A both increase by 10%, respectively, in the total power generation, with other conditions remaining unchanged, compare the evaluation effects of the improved CPS and the original CPS.

The one-month evaluation results of the original CPS and the improved CPS for the two control areas are shown in

Figure 4. After the increase in new-energy power generation in control area A, the randomness and volatility of new-energy power output leads to an increase in disturbance in control area A, and the regional imbalance also rises accordingly. Compared with the data in

Table 4, the evaluation results of control area A under the original CPS deteriorate significantly. This is because the original CPS does not account for the changes in the power supply structure of control area A and still evaluates both control areas A and B using the same evaluation threshold.

Comparing the evaluation results of the improved CPS and the original CPS in

Figure 4, when the differences in new-energy generation between the two control areas are considered, the proportions of “Medium” and “Poor” evaluation points for control area A under the improved CPS are significantly reduced, becoming largely consistent with the proportions for control area B. Meanwhile, the reward proportion for “Excellent” in control area B remains unchanged. After recalculating the evaluation thresholds for the control areas based on the inherent ACE standard deviation, the evaluation results of the two control areas are essentially consistent.

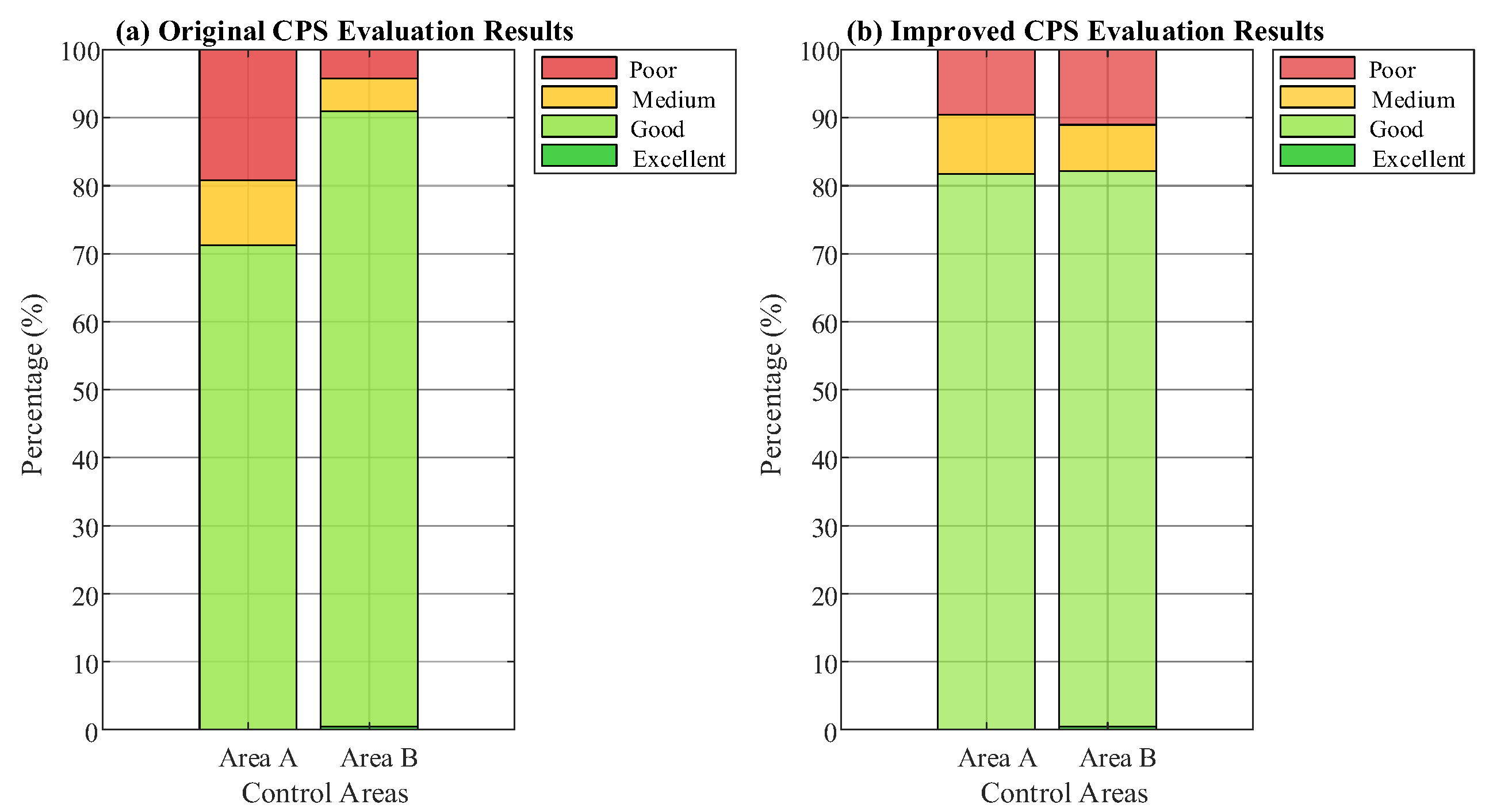

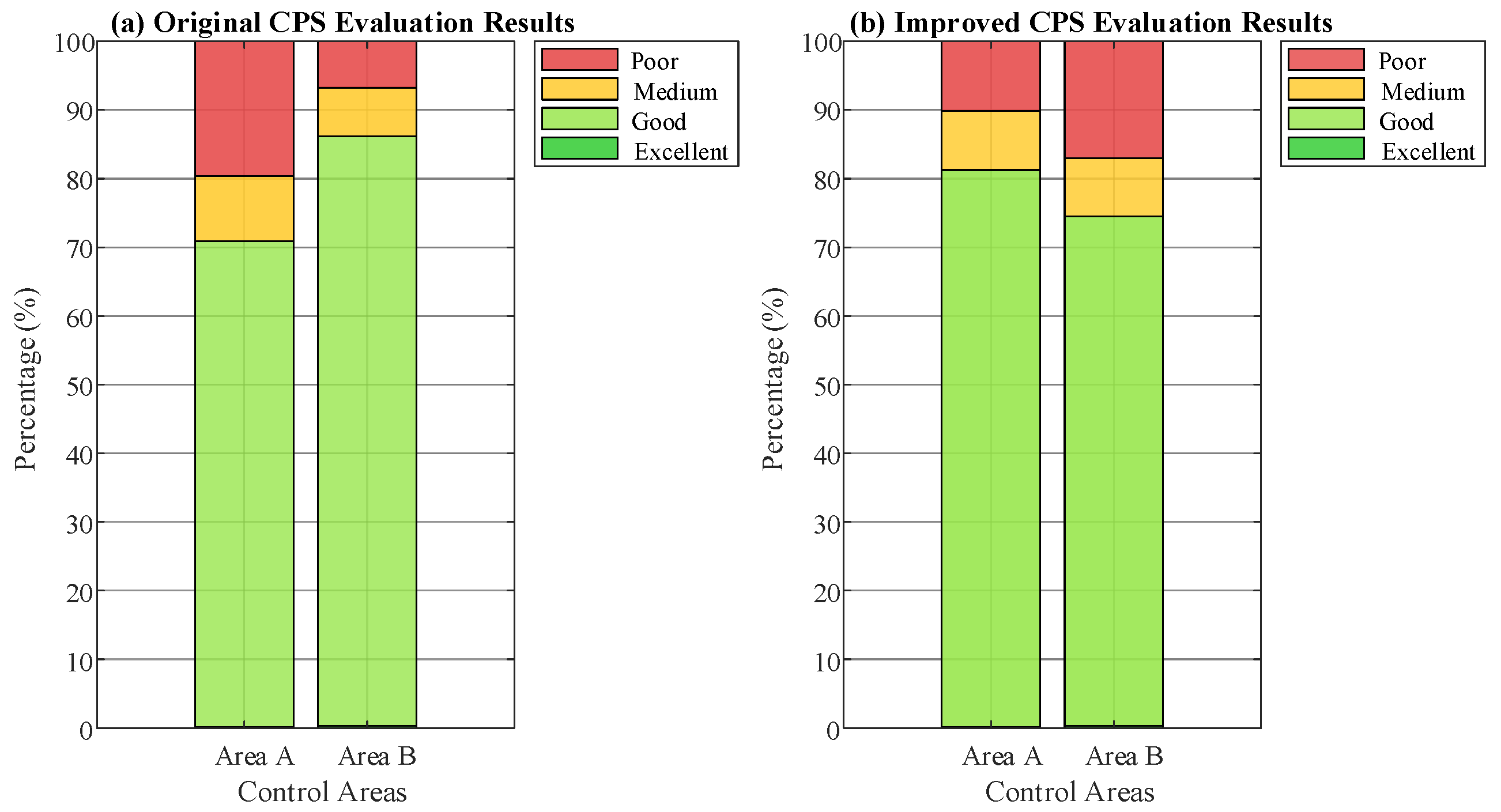

(3) When the proportion of wind power generation and photovoltaic power generation in control area A increases, respectively, by 10% in the total power generation, and the installed capacity of AGC units decreases by 10%, with other conditions remaining unchanged, compare the evaluation effects of the improved CPS and the original CPS.

The one-month evaluation results of the original CPS and the improved CPS for the two control areas are shown in

Figure 5. When the adjustable capacity of AGC units in control area A decreases by 10%, the frequency regulation capability of control area A declines, leading to a further increase in the ACE standard deviation. However, due to the reduction in the frequency bias coefficient of control area A, the evaluation threshold under the original CPS becomes smaller. The combined effect of these two factors results in a significantly worse original CPS evaluation result for control area A in

Figure 5 compared to the result in

Figure 4. Comparing the evaluation results of the improved CPS and the original CPS in

Figure 5, the two control areas show largely consistent outcomes under the improved CPS. Under the same active power balance control level, the improved CPS fully accounts for the differences in power supply structure when determining the evaluation thresholds. Instead of imposing penalties solely on control area A due to its higher new-energy generation and lower AGC capacity, the improved CPS demonstrates greater fairness and rationality compared to the original CPS.

(4) Based on Scenario 3, when the prediction error of wind power in control area B doubles, with other conditions remaining unchanged, compare the evaluation effects of the improved CPS and the original CPS.

The one-month evaluation results of the original CPS and the improved CPS for the two control areas are shown in

Figure 6. Based on Scenario 3, the wind power prediction error in control area B doubles due to degraded forecasting accuracy, leading to increased disturbances in control area B. As shown in

Figure 6, the original CPS evaluation result of control area B deteriorates significantly compared to that in

Figure 5. However, since the original CPS fails to properly account for differences in power supply structure between the two areas, control area A paradoxically receives a worse evaluation result than control area B, which is clearly unreasonable. In

Figure 6, the improved CPS evaluation result for control area B deteriorates noticeably compared to that in

Figure 5, while the result for control area A shows little change. Under the improved CPS, control area A now clearly outperforms control area B in the evaluation results. This demonstrates that the improved CPS, while fully considering differences in power supply structures, can still accurately reflect the impact of changes in prediction performance on evaluation outcomes.

(5) Based on Scenario 3, when the adjustment rate coefficient of AGC units in control area B is 80% of the original, with other conditions remaining unchanged, compare the evaluation effects of the improved CPS and the original CPS.

The one-month evaluation results of the original CPS and the improved CPS for the two control areas are summarized in

Figure 7. Due to the decreased regulation rate of AGC units in control area B, the original CPS evaluation result for control area B in

Figure 7 shows significant deterioration compared to that in

Figure 5. However, under the original CPS, control area A, which demonstrates better AGC ramping performance, paradoxically receives a worse evaluation result than control area B. In contrast, the improved CPS presented in

Figure 7 reflects a more rational evaluation outcome for both control areas. Combined with previous simulations, this fully demonstrates that the improved CPS, while adequately accounting for differences in power supply structures among control areas, can still accurately capture the impact of changes in control performance (such as prediction accuracy and unit ramp rates) on evaluation results.

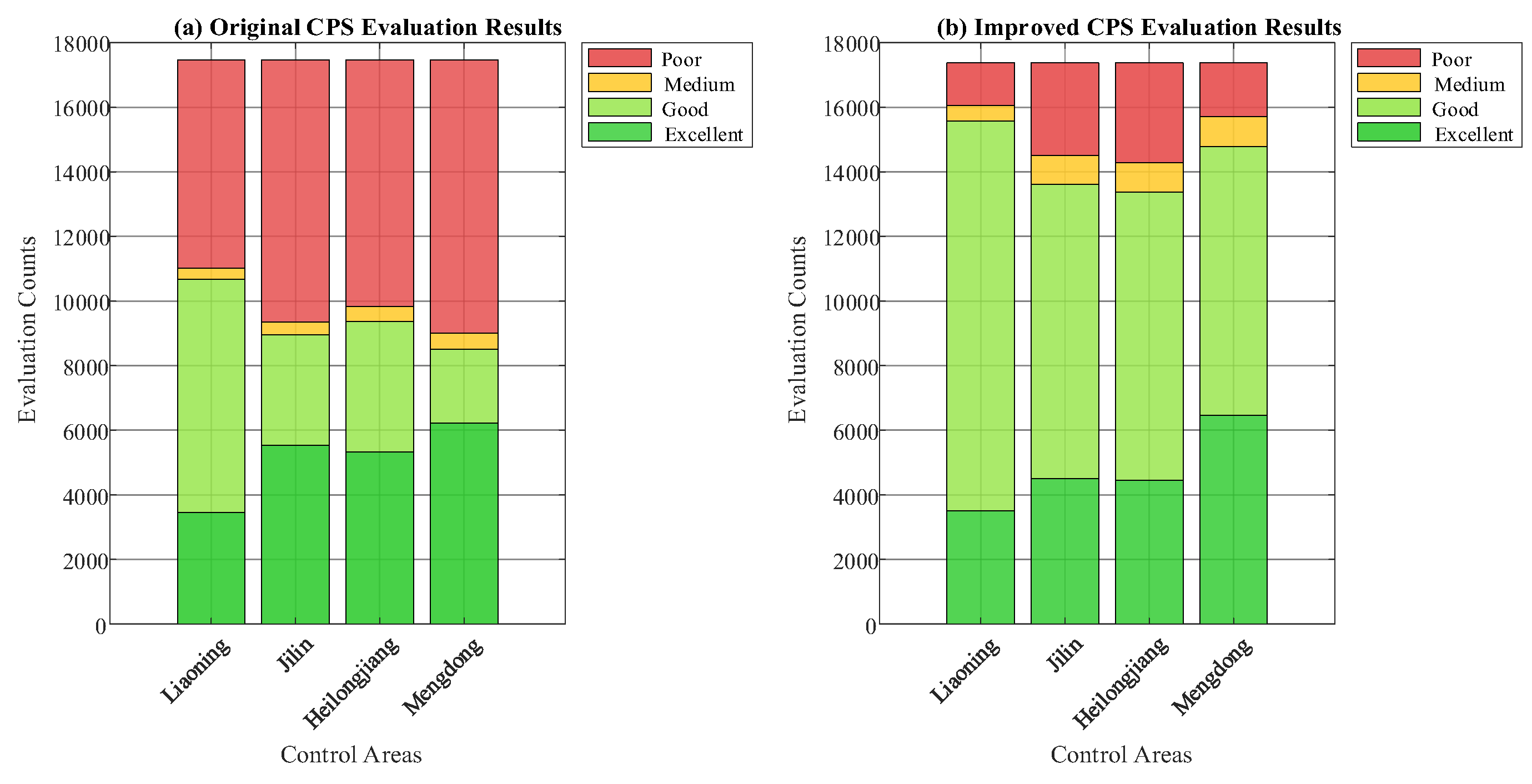

5.3. Practical Application Data Analysis

This evaluation results from various evaluation indicators for each province in the Northeast China power grid during two periods: from 1 February to 31 July 2024 (using the original CPS), and from 1 February to 31 July 2025 (using the improved CPS), presented in

Table 5 and

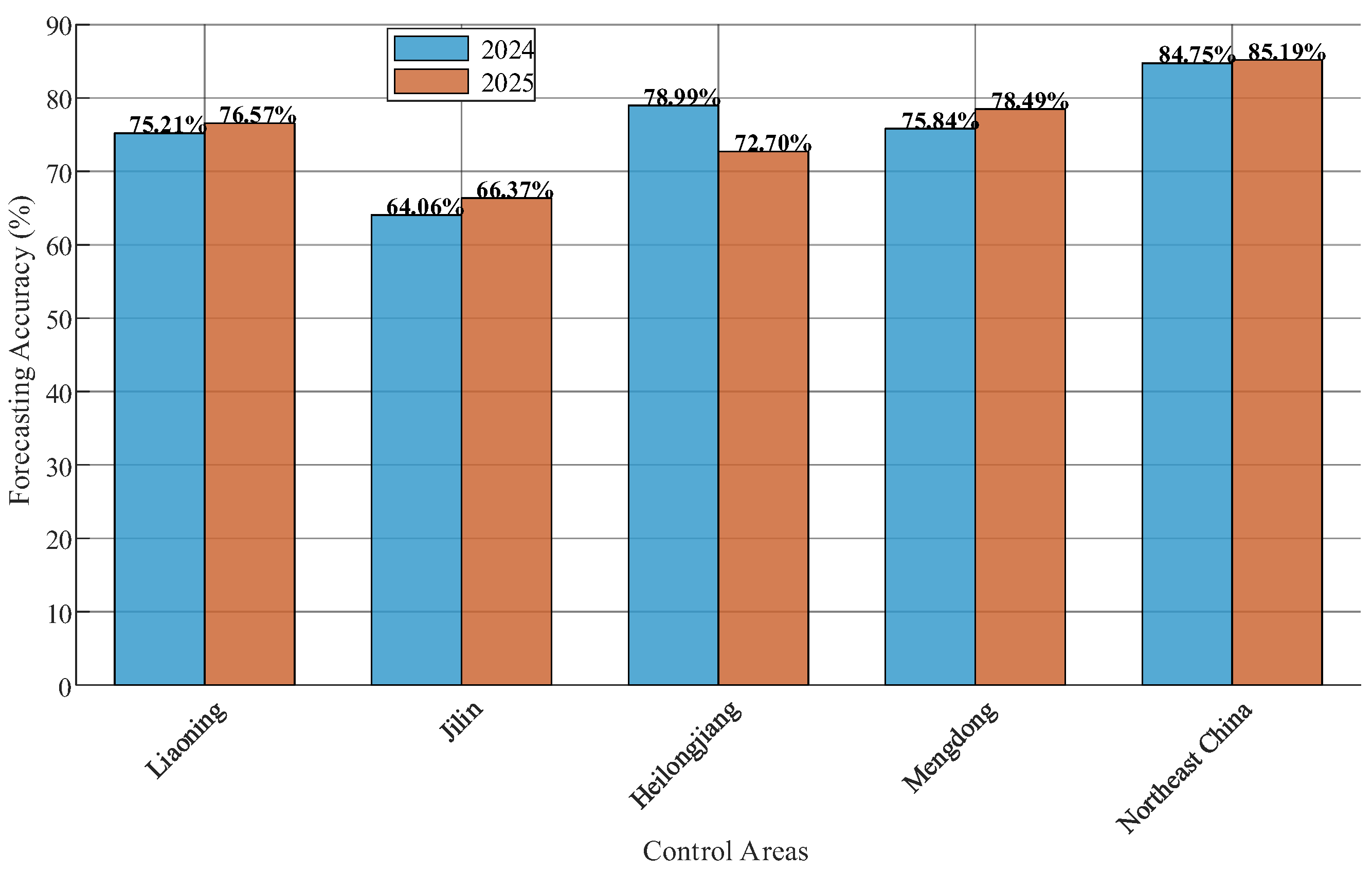

Figure 8. Meanwhile, the average new-energy forecasting accuracy of each province for the corresponding periods is shown in

Figure 9.

From

Table 2, it can be observed that the difference in the proportion of new-energy installed capacity between Mengdong and Liaoning is relatively large. Notably, Mengdong has the significantly highest proportion of “Excellent” evaluation points (According to the historical evaluation results, it has the highest AGC level). But it also has the highest proportion of “Poor” points due to its high proportion of new energy.

In contrast, Liaoning has the significantly lowest proportion of “Excellent” evaluation points (the comparatively lower AGC level). But it has the lowest proportion of “Poor” points because of its low proportion of new energy. This is obviously unfair to the Mengdong control area in terms of evaluation. However, under the improved CPS, when the differences in new-energy generation across various control areas are taken into account, the number of “Excellent” points for both the Liaoning and Mengdong control areas remains basically unchanged. However, the gap in the proportion of “Poor” points between the two narrows, and their evaluation results converge with their actual control levels. After redetermining the evaluation threshold for each control area based on the inherent ACE standard deviation, the evaluation results of all control areas essentially became consistent with their actual control capabilities.

Furthermore, the root mean square value of the 15 min average frequency deviation of the Northeast China power grid during 1 February to 31 July 2025, is calculated as 0.01731 Hz. For the same period (1 February to 31 July 2024), the value is 0.02425 Hz. It shows that the system frequency deviation has decreased significantly. Additionally, from

Figure 9, it can be seen that the new-energy forecasting accuracy of the three control areas (Liaoning, Mengdong, and Jilin) all improved compared with the same period last year. And the overall forecasting accuracy of the entire Northeast region increased from 84.75% to 85.19%. By comparing the evaluation results of the two standards, the calculated root mean square value of 15 min average frequency deviation, and the new-energy forecasting accuracy for the corresponding period, it is evident that the improved CPS has a better guiding effect on the control behaviors of control areas than the original CPS.

In summary, the improved CPS proposed in this paper determines the evaluation thresholds based on the inherent ACE standard deviation when allocating frequency regulation responsibilities among control areas. Under the same active power balance control level, the improved standard fully considers the differences in power source structures of each control area to determine the evaluation thresholds, instead of allowing control areas with large new-energy generation but small AGC unit capacity to solely bear fines caused by objective differences in power source structures. Thus, it is fairer and more reasonable compared with the original CPS. It fully considers the differences in power source structures of each control area, and is more suitable for implementation in power systems with a high proportion of new energy.

6. Conclusions

With the increasing integration of new energy sources, power supply structures across control areas in interconnected grids are becoming increasingly heterogeneous. In some regions where new-energy installations have expanded while conventional units have been phased out, this has resulted in heightened frequency regulation demands coupled with diminished control capabilities. The CPS under the traditional TBC model determines evaluation thresholds for each control area using frequency deviation coefficients, yet fails to account for the actual power source configurations within these areas. This approach has become increasingly incompatible with high-proportion new-energy systems, highlighting growing challenges in grid coordination.

This paper analyzes the prerequisites and implications of existing CPSs, revealing their incompatibility with high-proportion new-energy power systems. It subsequently proposes the concept of inherent ACE standard deviation for control areas. The inherent ACE standard deviation is defined as the standard deviation of ACE determined by the inherent conditions of power supply structures across control areas under identical active power balance control levels, with a calculation method provided. The study then establishes evaluation thresholds using this inherent ACE standard deviation, proposes improvements to CPSs, and compares them with existing versions of CPS. Case studies validate that the revised standards demonstrate greater fairness and reasonableness, fully considering objective and inherent differences in power supply structures while focusing on assessing active power balance control performance in control areas.

However, the inherent ACE standard deviation calculation method proposed in this paper only accounts for the secondary frequency regulation from conventional generators. As fast-regulating resources like energy storage play a larger role in the future, this calculation will need refinement—a direction for further research. Additionally, differences in response times among conventional units were not considered. While our analysis shows that this has minimal impact on practical implementation, it still warrants a more detailed study. So, a more reasonable and well-rounded standard still needs further research to keep pace with the evolving needs of the power system.