AI-Based Mapping of Offshore Wind Energy Around the Korean Peninsula Using Sentinel-1 SAR and Numerical Weather Prediction Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

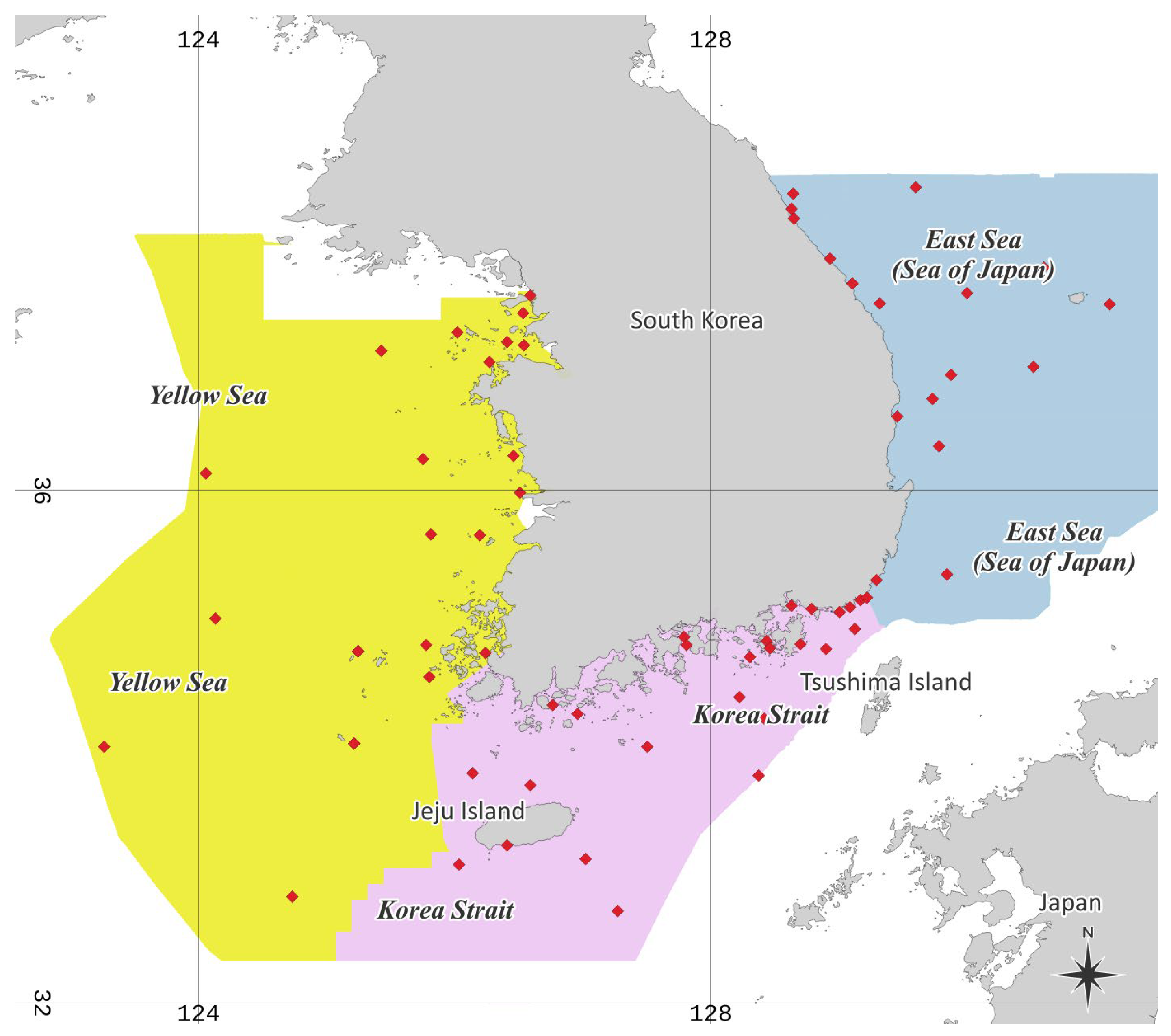

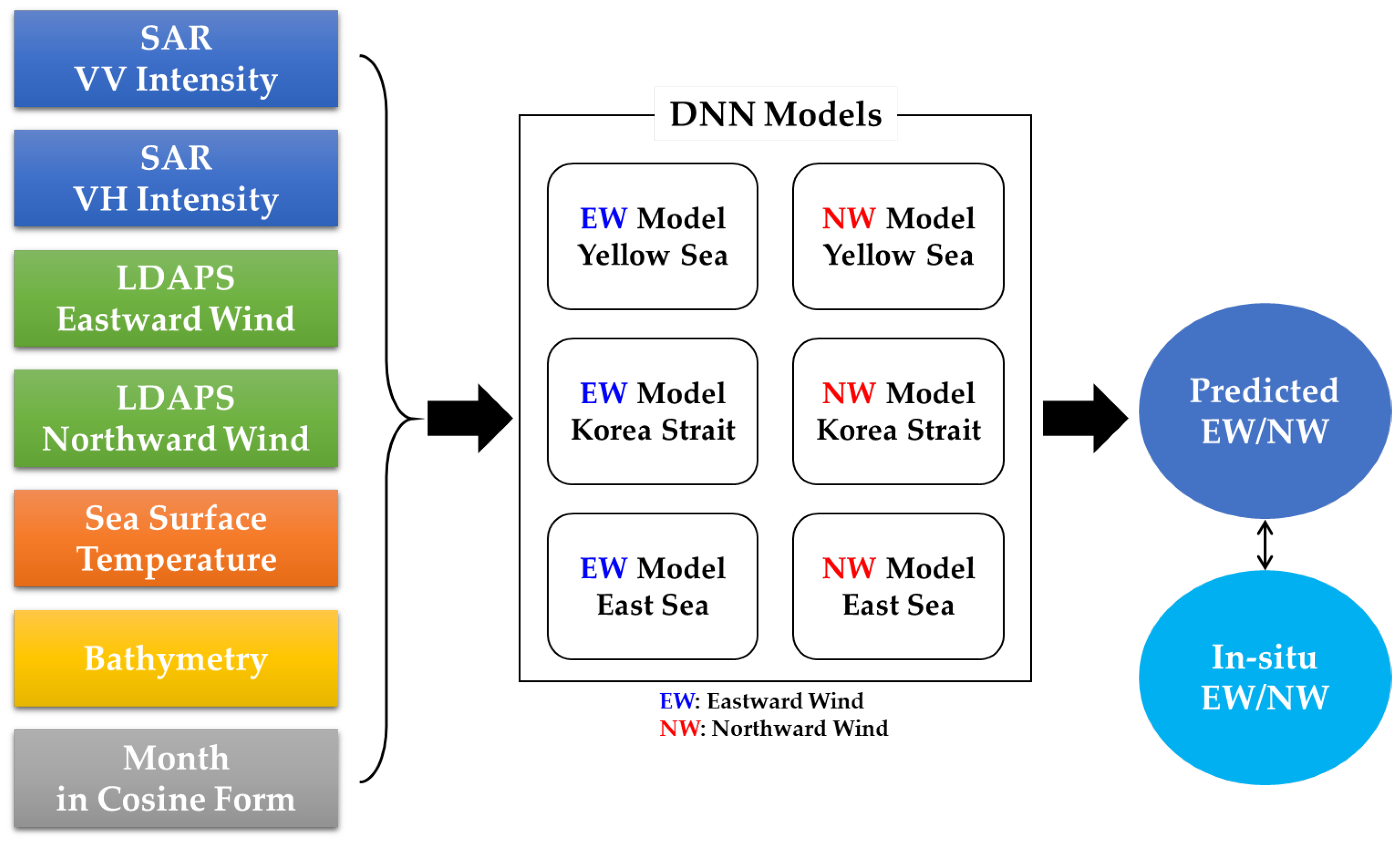

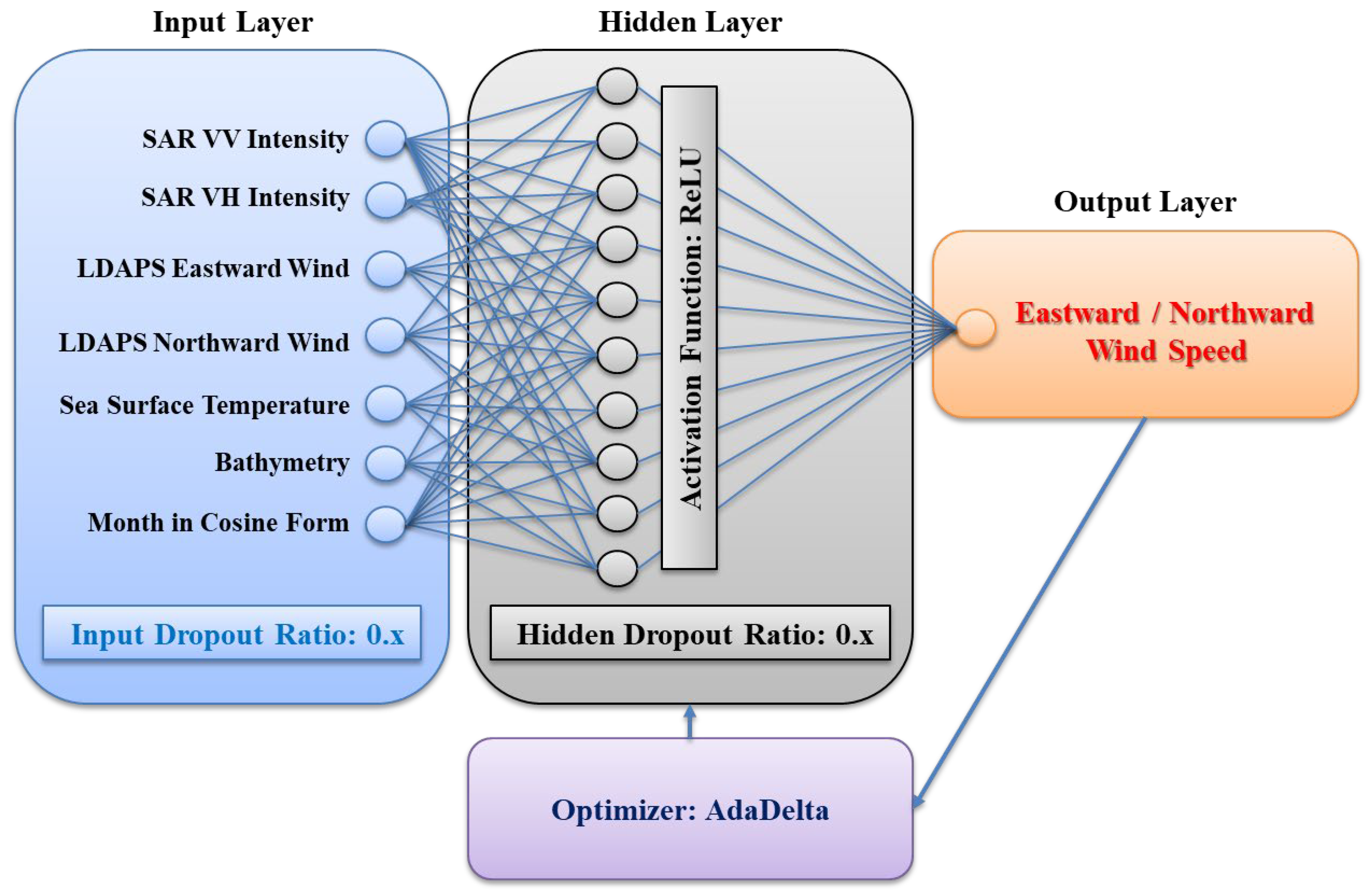

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

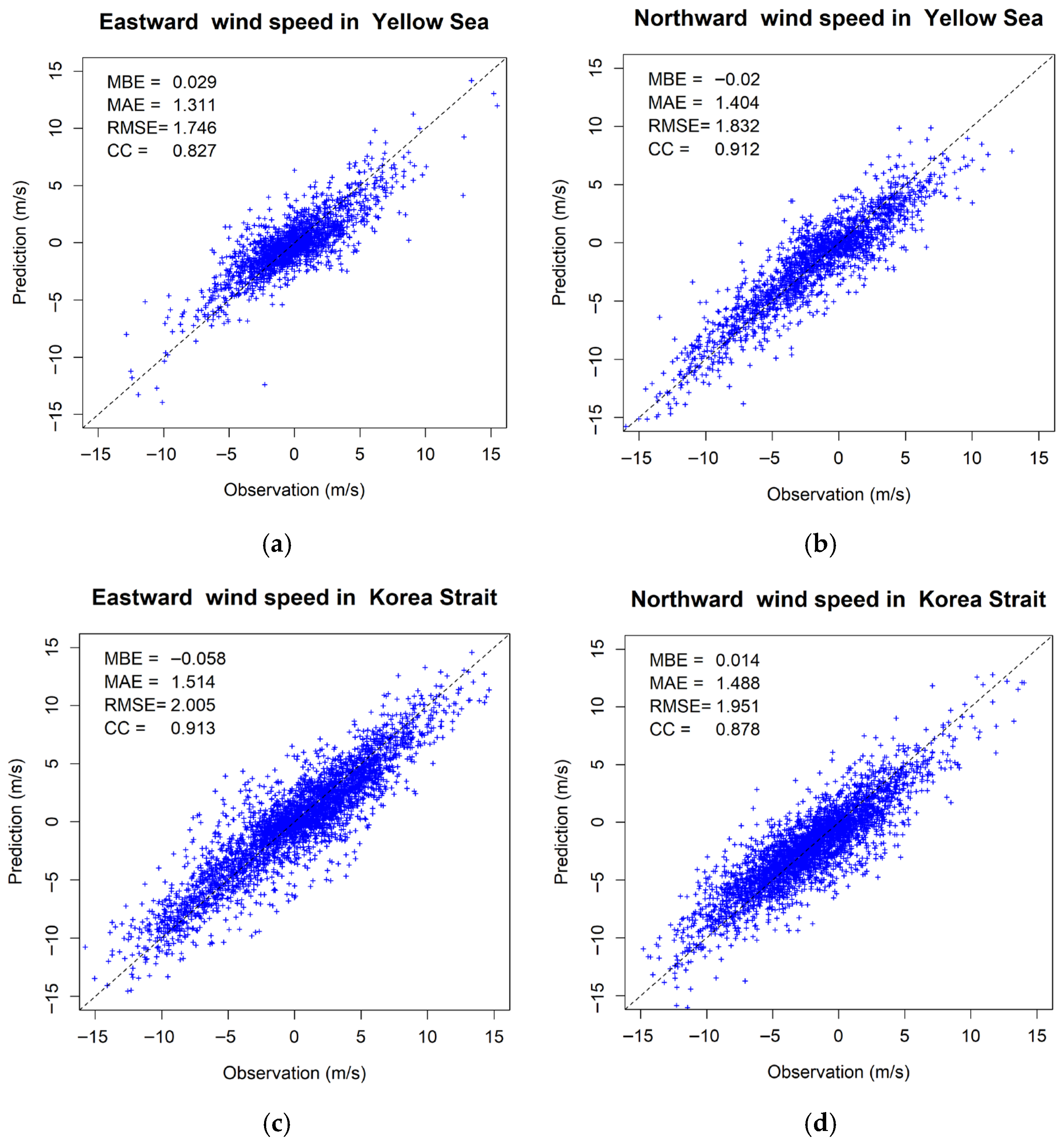

3.1. Accuracy of the DNN Models for Wind Speed

3.2. Feature Importance in the DNN Models for Wind Speed

3.3. Offshore Wind Energy Maps Using DNN Models

3.3.1. Spatial Distribution of Surface Wind Speed over the Korean Seas

3.3.2. Monthly Variation in Surface Wind Speed over the Korean Seas

4. Discussions

4.1. Comparisons with Previous Studies

4.2. Regional Characteristics

4.3. Seasonal Characteristics

4.4. Wind Energy Development

4.5. Application to Other Regions

4.6. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Draxl, C.; Hodge, B.-M.; Clifton, A. Overview and Meteorological Validation of the Wind Integration National Dataset Toolkit; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2015.

- Hahmann, A.N.; Sīle, T.; Witha, B.; Davis, N.N.; Dörenkämper, M.; Ezber, Y.; García-Bustamante, E.; González-Rouco, J.F.; Navarro, J.; Olsen, B.T.; et al. The Making of the New European Wind Atlas—Part 1: Model Sensitivity. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 5053–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörenkämper, M.; Olsen, B.T.; Witha, B.; Hahmann, A.N.; Davis, N.N.; Barcons, J.; Ezber, Y.; García-Bustamante, E.; González-Rouco, J.F.; Navarro, J.; et al. The Making of the New European Wind Atlas—Part 2: Production and Evaluation. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 5079–5102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, N.N.; Badger, J.; Hahmann, A.N.; Hansen, B.O.; Mortensen, N.G.; Kelly, M.; Larsén, X.G.; Olsen, B.T.; Floors, R.; Lizcano, G.; et al. The Global Wind Atlas: A High-Resolution Dataset of Climatologies and Associated Web-Based Application. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2023, 104, E1507–E1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, C.; Hemer, M.; Howard, P.; Langdon, R.; Marsh, P.; Teske, S.; Carrascosa, D. Offshore Wind Energy in Australia; Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre: Newnham, Australia, 2021; p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.; Kim, Y.; Choi, H. Analyses of the Meteorological Characteristics over South Korea for Wind Power Applications Using KMAPP. Atmosphere 2021, 31, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaucage, P.; Bernier, M.; Lafrance, G.; Choisnard, J. Regional Mapping of the Offshore Wind Resource: Towards a Significant Contribution from Space-Borne Synthetic Aperture Radars. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2008, 1, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Xu, Q.; Zheng, Q. An Overview on SAR Measurements of Sea Surface Wind. Prog. Nat. Sci. 2008, 18, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caligiuri, C.; Stendardi, L.; Renzi, M. The Use of Sentinel-1 OCN Products for Preliminary Deep Offshore Wind Energy Potential Estimation: A Case Study on the Ionian Sea. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2022, 35, 101117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachatrian, E.; Asemann, P.; Zhou, L.; Birkelund, Y.; Esau, I.; Ricaud, B. Exploring the Potential of Sentinel-1 Ocean Wind Field Product for Near-Surface Offshore Wind Assessment in the Norwegian Arctic. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.M.; Qin, T.; Wu, K. Retrieval of Sea Surface Wind Speed from Spaceborne SAR over the Arctic Marginal Ice Zone with a Neural Network. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joh, S.U.; Ahn, J.; Lee, Y. Estimation of High-Resolution Sea Wind in Coastal Areas Using Sentinel-1 SAR Images with Artificial Intelligence Technique. Korean J. Remote Sens. 2021, 37, 1187–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joh, S.U.; Lee, Y. Seasonal and Geographical Differences of Accuracy for SAR Sea Wind Retrieval Using Deep Neural Networks in Coastal Waters of Korea. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th Asia-Pacific Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar (APSAR), Bali, Indonesia, 23–27 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- North Pacific Marine Science Organization (PICES). The Yellow Sea and East China Sea: A Scientific Summary; PICES Scientific Report No. 62; PICES: Sidney, BC, Canada, 2019; Available online: https://meetings.pices.int/publications/scientific-reports/Report62/Rpt62.pdf (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Johnson, D.R.; Teague, W.J. Observations of the Korea Strait Bottom Cold Water. Cont. Shelf Res. 2002, 22, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K.; Seung, Y.H.; Kim, Y.B.; Kim, Y.H.; Shin, H.R.; Shin, C.W.; Chang, K.L. Circulation. In Oceanography of the East Sea (Japan Sea); Chang, K.L., Zhang, C.-I., Park, C., Kang, D.-J., Ju, S.-J., Lee, S.-H., Wimbush, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASF DAAC. Sentinel-1 SAR Data. NASA Earthdata, Alaska Satellite Facility Distributed Active Archive Center (ASF DAAC). Available online: https://search.asf.alaska.edu/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- ESA (European Space Agency). Sentinel Application Platform (SNAP). Available online: https://step.esa.int/main/toolboxes/snap/ (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA). Local Data Assimilation and Prediction System (LDAPS). Available online: https://data.kma.go.kr/data/rmt/rmtList.do?code=340&pgmNo=65 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- KMA. Open MET Data Portal. Available online: https://data.kma.go.kr/data/sea/selectBuoyRltmList.do?pgmNo=52 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- KHOA (Korea Hydrographic and Oceanographic Agency). Ocean Data in Grid Framework. Available online: http://www.khoa.go.kr/oceangrid/gis/category/reference/distribution.do (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- GHRSST. Operational Sea Surface Temperature and Sea Ice Analysis (OSTIA); Met Office. Available online: https://ghrsst-pp.metoffice.gov.uk/ostia-website/index.html (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- KHOA. BADA2024, Bathymetric Data 2024. Available online: http://www.khoa.go.kr/oceangrid/gis/category/observe/observeSearch.do?type=EYS#none (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Kim, J.-Y.; Kim, H.-G.; Kang, Y.-H. Offshore Wind Speed Forecasting: The Correlation between Satellite-Observed Monthly Sea Surface Temperature and Wind Speed over the Seas around the Korean Peninsula. Energies 2017, 10, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurman, H.V.; Trujillo, A.P. Essentials of Oceanography, 7th ed.; Chapter 8: Waves and Water Dynamics; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; Available online: http://www.prenhall.com/thurman (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development Environment for R, Version 2024.12.1 Build 563; [Computer Software]; Posit Software, PBC: Boston, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://posit.co (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- H2O. ai. H2O: Scalable Machine Learning and Deep Learning Platform, Version 3.42.0.2; H2O.ai: Mountain View, CA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.h2o.ai (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Horstmann, J.; Koch, W. Measurement of Ocean Surface Winds Using Synthetic Aperture Radars. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2005, 30, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Yang, S.; Xu, D. On Accuracy of SAR Wind Speed Retrieval in Coastal Area. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 95, 102012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Montera, L.; Remmers, T.; O’Connell, R.; Desmond, C. Validation of Sentinel-1 Offshore Winds and Average Wind Power Estimation around Ireland. Wind Energy Sci. 2020, 5, 1023–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.S.; Park, K.A.; Moon, W.I. Wind Vector Retrieval from SIR-C SAR Data off the East Coast of Korea. J. Korean Earth Sci. Soc. 2010, 31, 475–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, H.; Pang, I.; Kim, T. Relations between Wave and Wind at Five Stations around the Korean Peninsula. J. Korean Earth Sci. Soc. 2005, 26, 240–252. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y.; Seuk, H.; Bang, J.; Kim, Y. Seasonal Characteristics of Sea Surface Winds and Significant Wave Heights Observed by Marine Meteorological Buoys and Lighthouse AWSs near the Korean Peninsula. J. Environ. Sci. Int. 2015, 24, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.K.; Niiler, P.P. Eddies in the Southwestern East/Japan Sea. Deep Sea Res. 2010, 57, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Nam, S.; Kim, Y.-G. Statistical Characteristics of East Sea Mesoscale Eddies Detected, Tracked, and Grouped Using Satellite Altimeter Data from 1993 to 2017. J. Korean Soc. Oceanogr. 2019, 24, 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Choi, B.; Lee, S.; Son, Y. Response of the Thermohaline Front and Associated Submesoscale Features in the Korea Strait to Wind Variation during Autumn. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1571360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, C. Rapid Surface Warming of the Pacific Asian Marginal Seas Since the Late 1990s. J. Geophys. Res. 2022, 127, e2022JC018744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Choi, B. Vertical structure and variation of currents observed in autumn in the Korea Strait. Ocean Sci. J. 2015, 50, 163–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Meteorological Society (AMS). Deacon Wind Profile Parameter. In Glossary of Meteorology; American Meteorological Society (AMS): Boston, MA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://glossary.ametsoc.org/wiki/Deacon_wind_profile_parameter (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Son, J.-H.; Heo, K.-Y.; Choi, J.-W.; Kwon, J.-I. Long-Lasting Upper Ocean Temperature Responses Induced by Intense Typhoons in Mid-Latitude. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEBCO Compilation Group. The GEBCO_2023 Grid—A Continuous Terrain Model of the Global Ocean and Land; British Oceanographic Data Centre, National Oceanography Centre: Liverpool, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA National Data Buoy Center (NDBC). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Available online: https://www.ndbc.noaa.gov (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA). Wind and Solar Meteorological Resources. Available online: http://www.greenmap.go.kr/kr/inquiry.do?NUM=1 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Vogelzang, J.; Stoffelen, A. A Land-Corrected ASCAT Coastal Wind Product. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Name | Mean | SD | Unit | SR | TR | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In situ observation with marine buoys | Wind speed | 5.38 | 3.39 | m/s | Point | 1 to 30 min | KMA and KHOA |

| Wind direction | 188.9 | 115.4 | ° | ||||

| SAR intensity of Sentinel-1A/1B | VV intensity | −18.80 | 4.99 | dB | 10 m | 12 days | ESA |

| VH intensity | −29.30 | 3.61 | dB | ||||

| LDAPS numerical weather data | Eastward wind speed | 0.55 | 4.29 | m/s | 1.5 km | 3 h | KMA |

| Northward wind speed | −1.62 | 4.46 | m/s | ||||

| Synthetic product with in situ and satellite data | Sea surface temperature | 291.05 | 5.59 | °K | 1 km | 1 day | OSTIA |

| Echo sounding | Bathymetry | 183.4 | 420.2 | meter | 150 m | N.A. | KHOA |

| Hyperparameters | Yellow Sea | Korea Strait | East Sea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EW | NW | EW | NW | EW | NW | |

| Activation function | ReLU | ReLU | ReLU | ReLU | ReLU | ReLU |

| Hidden layer neurons | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Training epochs | 5000 | 5000 | 2000 | 2500 | 5000 | 2000 |

| Learning rate decay | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.9 | 0.99 | 0.95 |

| Hidden dropout ratio | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Input dropout ratio | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.0 | 0.05 | 0.1 |

| Optimizer | AdaDelta | AdaDelta | AdaDelta | AdaDelta | AdaDelta | AdaDelta |

| Metrics | Yellow Sea | Korea Strait | East Sea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EW | NW | EW | NW | EW | NW | |

| MBE (m/s) | 0.029 | −0.020 | −0.058 | 0.014 | 0.079 | −0.100 |

| MAE (m/s) | 1.311 | 1.404 | 1.514 | 1.488 | 1.543 | 1.687 |

| CC | 0.827 | 0.912 | 0.913 | 0.878 | 0.848 | 0.861 |

| Regions | Yellow Sea | Korea Strait | East Sea | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Features | East | North | East | North | East | North | |

| SAR VV Intensity | 16.6 | 13.8 | 16.7 | 14.2 | 12.0 | 12.5 | |

| SAR VH Intensity | 11.6 | 9.8 | 6.9 | 9.7 | 8.1 | 7.9 | |

| LDAPS Eastward wind speed | 19.3 | 14.0 | 33.9 | 9.5 | 17.8 | 13.4 | |

| LDAPS Northward wind speed | 12.6 | 29.3 | 12.9 | 33.1 | 13.7 | 20.0 | |

| Sea surface temperature | 11.8 | 12.6 | 9.5 | 11.1 | 14.0 | 12.3 | |

| Bathymetry | 10.9 | 8.8 | 13.0 | 13.0 | 21.9 | 19.7 | |

| Month | 17.2 | 12.4 | 7.2 | 9.4 | 12.4 | 14.1 | |

| Accuracy | RMSE | MAE | MBE | Method | Region | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | |||||||

| Horstmann and Koch [28] | 2.11–2.85 | NA | −0.16–0.85 | GMF | Spitsbergen, Norway | NWP forecast | |

| Wei et al. [29] | 1.31–5.50 | 1.00–3.64 | −0.06–1.88 | GMF | Miami, U.S. | Marine buoy | |

| OCN Products [30] | 1.2–2.0 | NA | NA | GMF | European Seas | Marine buoy | |

| Kim et al. [31] | 1.30–1.72 | NA | NA | GMF | East Sea, South Korea | Reanalysis | |

| Ours | 1.75–2.17 | 1.31–1.69 | −0.10–0.08 | DNN | Offshore, South Korea | Marine buoy | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Joh, J.S.-u.; Nghiem, S.V.; Kafatos, M.; Liu, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, Y. AI-Based Mapping of Offshore Wind Energy Around the Korean Peninsula Using Sentinel-1 SAR and Numerical Weather Prediction Data. Energies 2025, 18, 6252. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236252

Joh JS-u, Nghiem SV, Kafatos M, Liu J, Kim J, Kim SH, Lee Y. AI-Based Mapping of Offshore Wind Energy Around the Korean Peninsula Using Sentinel-1 SAR and Numerical Weather Prediction Data. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6252. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236252

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoh, Jason Sung-uk, Son V. Nghiem, Menas Kafatos, Jay Liu, Jinsoo Kim, Seung Hee Kim, and Yangwon Lee. 2025. "AI-Based Mapping of Offshore Wind Energy Around the Korean Peninsula Using Sentinel-1 SAR and Numerical Weather Prediction Data" Energies 18, no. 23: 6252. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236252

APA StyleJoh, J. S.-u., Nghiem, S. V., Kafatos, M., Liu, J., Kim, J., Kim, S. H., & Lee, Y. (2025). AI-Based Mapping of Offshore Wind Energy Around the Korean Peninsula Using Sentinel-1 SAR and Numerical Weather Prediction Data. Energies, 18(23), 6252. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236252