1. Introduction

The promotion of electric vehicles (EVs) is a key initiative to reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions, with lithium-ion battery technology at its core [

1,

2]. High-energy-density batteries enhance driving range, while fast-charging technology shortens charging time [

3]. However, frequent fast charging can trigger side reactions: increased battery temperature accelerates the growth of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) on the anode, making it structurally unstable and increasing lithium-ion (Li

+) transport resistance [

4]. Simultaneously, Li

+ accumulation on the anode surface promotes lithium plating, leading to dendrite formation, which damages battery structure and shortens lifespan [

5]. Thus, a balance must be struck between charging speed and battery longevity. The current mainstream solution involves optimizing battery management systems (BMS) with intelligent charging control strategies to balance performance and durability.

Numerous studies have highlighted that lithium deposition serves as the predominant aging mechanism leading to accelerated capacity degradation in lithium-ion batteries (LiB) under fast-charging conditions [

6]. Consequently, monitoring lithium deposition during the charging process is essential for mitigating or preventing its effects. Although in situ detection methods—such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [

7] and inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICPOES) [

8]—have been developed to identify lithium deposition, these techniques typically require battery disassembly for evaluation. As a result, such destructive approaches are unsuitable for integration into real-time charging control systems.

Several online lithium deposition detection methods have also been proposed. For example, the framework developed in [

9], based on incremental capacity (IC) analysis and mechanical model simulation, is used to assess lithium deposition phenomena. Incremental capacity analysis effectively identifies and tracks the position of the reversible lithium plating layer. The study findings suggest that the significant loss of active material (LAM) on the anode is the primary cause of lithium deposition. Furthermore, the occurrence of lithium deposition increases the loss rate of the lithium inventory by a factor of four. In Ref. [

10], the lithium deposition phenomenon in LIB was studied using voltage relaxation and online neutron diffraction methods. The study found that the rate of lithium insertion during deposition appeared to be constant and was not influenced by the amount of deposition.

In Ref. [

11], a novel approach was introduced for detecting, characterizing, and quantifying lithium plating in commercial graphite/LiFePO

4 LiBs. This method utilizes the voltage plateau that appears on charge–discharge curves under electroplating conditions—a phenomenon associated with the detachment of deposited lithium from the graphite surface. The study demonstrated that differential analysis of the voltage profile allows quantitative estimation of lithium plating. Separately, Ref. [

12] presented a technique that integrates voltage relaxation and impedance spectroscopy to identify lithium plating layers in commercial LiBs featuring graphite anodes. This approach can monitor impedance variations resulting from the concurrent depletion of reversibly plated lithium. The findings revealed that similarities in the fundamental physicochemical mechanisms can be discerned by comparing voltage relaxation behavior and lithium stripping processes during discharge. As a result, the amount of lithium deposited during relaxation conditions could be quantified. However, the methods mentioned above all require specific test conditions. For instance, the differential voltage (DV) method necessitates a constant discharge current, while the voltage relaxation profile (VRP) method requires a considerable relaxation period after the charging event, which limits their applicability in real-time applications.

Many researchers have also employed electrochemical modeling approaches to quantitatively detect lithium deposition for optimizing fast charging protocols. In Ref. [

13], based on the Newman model, a variable current charging method was applied by controlling the anode potential, allowing LIBs to charge at rates ranging from 4.5 C to 7.5 C at 80% capacity without reaching the thermodynamic conditions for lithium metal deposition on the anode. Results indicate that a 7 C charging rate can be applied without inducing lithium deposition when operating at 45 °C or when using thinner electrodes. Ref. [

14] employed an electrothermal-coupled model to evaluate three distinct thermal management strategies for fast charging, examining the resulting temperature dynamics and cooling demands in LiBs. It was demonstrated that integrating a preheating phase with adiabatic rapid charging can optimally address both lithium plating suppression and thermal regulation requirements. Meanwhile, Ref. [

15] introduced a health-conscious fast-charging protocol founded on an enhanced single-particle model (SPM) that incorporates degradation mechanisms and dynamic programming optimization. This method considerably reduces charging duration while preserving long-term battery health.

In Ref. [

16], a multi-stage fast charging protocol for LiBs was optimized using a pseudo-two-dimensional (P2D) electrochemical-thermal degradation model and a dynamic programming (DP) algorithm. This approach markedly suppresses SEI layer formation and reduces lithium plating by elevating the SEI formation potential. Ref. [

17] employed a physics-based aging model integrating both SEI growth and lithium deposition to analyze their competitive interaction, as well as variations in the ideal charging temperature with C-rate and energy density. It was found that the optimal charging strategy is highly dependent on both temperature and energy density conditions. Ref. [

18] introduced an online closed-loop charging framework using Bayesian optimization and the Doyle-Fuller-Newman (DFN) model, aiming to minimize lithium inventory loss resulting from SEI growth and lithium plating. Results show that the optimal charging current follows a gradually decreasing profile, which is more evident at lower temperatures and less pronounced at higher ones. Comprehensive studies confirm that irreversible lithium dendrite formation during fast charging considerably accelerates capacity fade and leads to permanent electrochemical degradation, representing a key failure mode that limits cycle life. Therefore, for practical lithium battery applications, it is essential to establish fast-charging optimization methods incorporating non-invasive sensing to enable real-time diagnosis and dynamic control of lithium dendrite nucleation.

To overcome these technical challenges, this paper develops a health-aware FCS based on a high-fidelity digital twin model of the battery. First, the battery’s electro-thermal aging behavior under different health factors is analyzed using the developed health-aware FCS. The results show that charging protocols with higher health factors lead to smaller battery capacity loss. Specifically, the charging protocol with a 20% health factor results in a capacity loss that is 12% less than that observed in the aging results with a 5% health factor, demonstrating a significant improvement in the suppression of battery aging. Next, this paper analyzes the impact of the number of charging protocol steps on battery aging. It was found that as the number of charging protocol steps increases, the capacity loss caused by side reactions gradually increases, although fast charging can be completed in a shorter time. To address this, the number of charging steps is extended to infinity, and a real-time health-aware FCS is developed. Finally, the impact of the proposed FCS on battery aging is evaluated. It is found that, compared to the 2 C constant current charging strategy, the health-aware variable current profile (VCP) charging strategy with a 20% health factor can effectively reduce capacity loss caused by lithium deposition by up to 17.59% and significantly reduce capacity loss caused by side reactions by up to 15.4%. This demonstrates that the health factor-based FCS proposed in this paper can significantly mitigate the battery aging while effectively preventing or suppressing the lithium deposition.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the relevant parameters of LIBs and the process for extracting the lithium deposition point.

Section 3 provides a brief overview of the electrochemical mechanism model of LIBs, the thermal model, and the proposed health-aware online fast charging optimization framework for suppressing lithium plating.

Section 4 presents the analysis and discussion of the results. Finally,

Section 5 provides the conclusion.

4. Results and Discussion

This paper develops a health-conscious FCS capable of charging the battery from 0% to 60% SOC in approximately 0.4 h. Considering practical driving conditions, the discharge current is set to 0.5 C for the experiments. Additionally, it is assumed that the battery will remain stationary for half an hour after both charging and discharging. Unless otherwise specified, all experimental tests in this study are conducted at an ambient temperature of 25 °C.

Figure 3 shows the safe fast charging curve under different health factors and the multi-stage constant current (MCC) fast charging protocol designed based on the safe fast charging curve, divided into four stages. The safe fast charging curve for a health factor of 5% is represented by a blue dashed line, while the corresponding MCC fast charging protocol is represented by a blue solid line. The representation of charging protocols for other health factors follows a similar format. Given that the battery employed in this study is of the energy type and operational safety is a priority, a 3 C charging current is chosen as the initial value. This current is subsequently divided into four equal intervals according to the current differential derived from each safe fast-charging profile. This ensures that at different stages, the current change is uniform and gradually decreases.

4.1. Battery Aging Under Different Health Factors

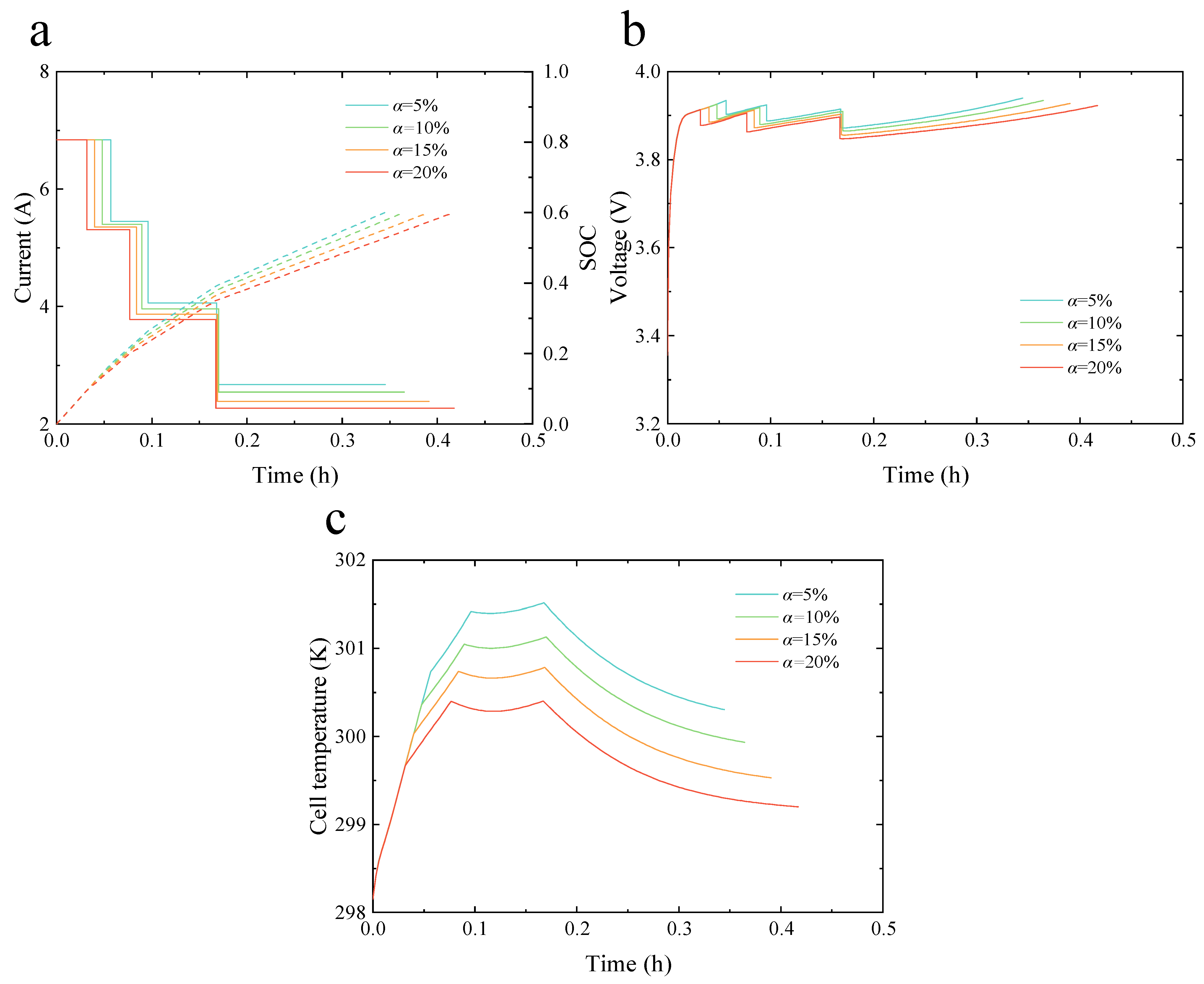

Figure 4a–c present an evaluation of the electro-thermal behavior of the battery under different health factors and the four-step MCC, based on the health-conscious FCS introduced in this study.

Figure 4a shows the variations in current and SOC with time during the fast charging of a LIB. When the cutoff SOC for charging is 0.6, the four-step MCC fast charging time is shortest at a health factor of 5%, while it is longest at a health factor of 20%. Notably, the largest difference in charging time occurs during the fourth step of the four-step MCC under different health factors.

Figure 4b,c show the variations in voltage and battery temperature with time, respectively. When the health factor is 5%, the charging current in each step of the four-step MCC is larger than in other health factors, resulting in corresponding voltage and temperature curves that rise faster than those under other health factors.

As widely recognized, variations in the electrolyte ion concentration alter the potential distribution within the electrolyte, subsequently affecting the anode potential and ultimately influencing the lithium plating reaction.

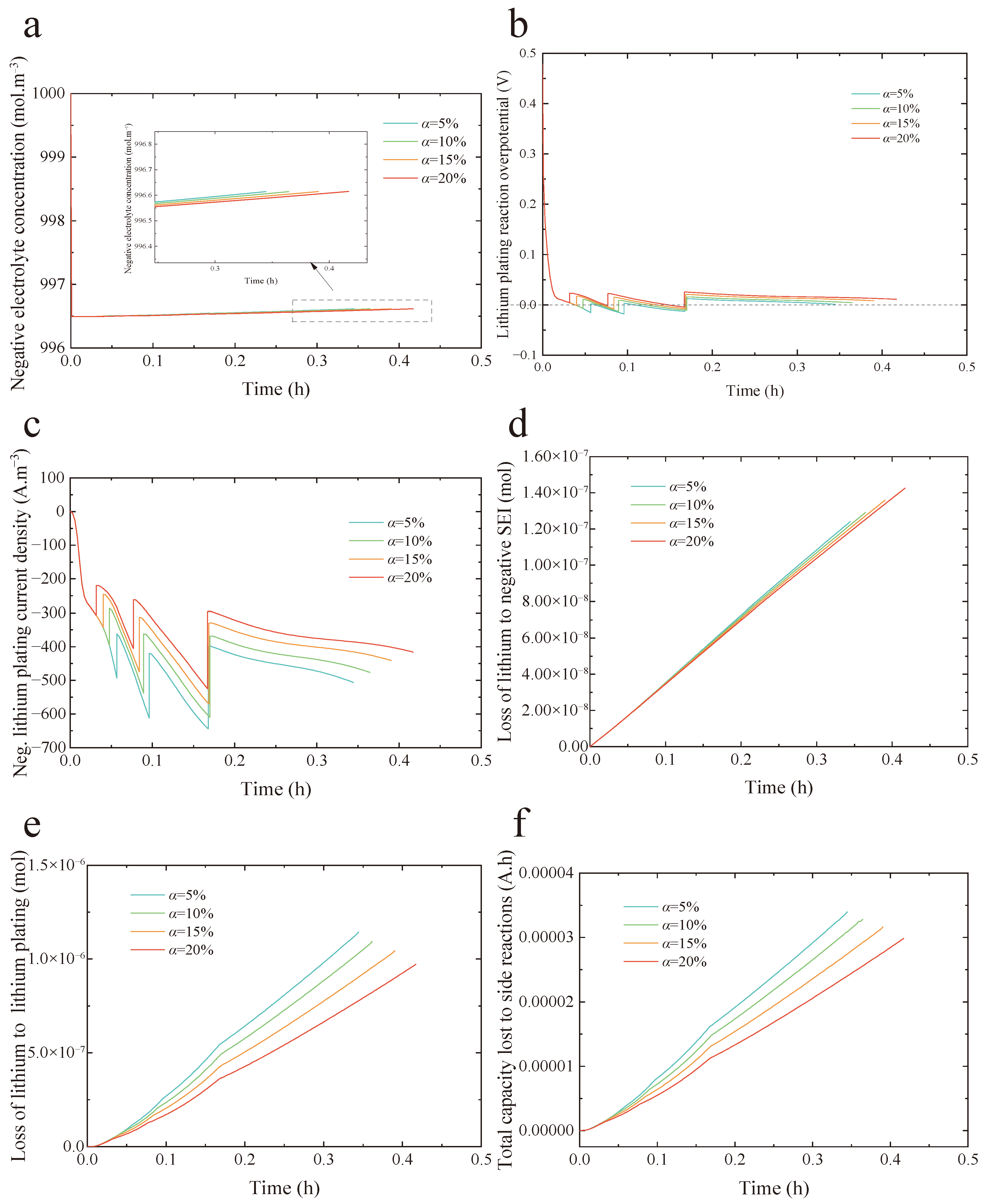

Figure 5 demonstrates how the electrolyte concentration gradient impacts the anode lithium plating potential, the corresponding plating current density, and the internal aging mechanisms of the battery under a four-step MCC protocol and various health conditions.

Figure 5a displays the changes in electrolyte concentration adjacent to the anode side of the separator. The charging protocols differ with varying health factors, which further lead to different electrolyte concentration gradients. As shown in

Figure 5a, a smaller health factor results in a larger electrolyte concentration gradient, which consequently raises the electrolyte potential. The overpotential for the lithium plating reaction, as defined in Equation (7), is denoted as

. According to the definition, a rise in electrolyte potential results in a reduction in the overpotential associated with the lithium plating reaction, as illustrated in

Figure 5b. At low SOC, due to the maximum charging currents determined by the charging protocol with a 5% health factor, and the longer charging times during the first and second steps, the lithium plating potential becomes lower than 0 V vs. Li/Li

+ earlier compared to other health factors, and the duration below 0 V is also the longest.

Figure 5c shows the distribution of anode lithium plating current density. It can be observed that the lithium plating current density for a 5% health factor is approximately 1.3 times higher than that for a 20% health factor. Moreover, the increase in the ion concentration gradient accelerates the diffusion of lithium ions from the electrolyte to the anode, while the lower anode potential enhances the electrochemical driving force between the electrode and the electrolyte. The combined effect of these two factors leads to a significant increase in the anode lithium plating current density, further promoting the Li

+ deposition process.

Figure 5d–f assess the influence of the fast-charging protocol on internal aging mechanisms in LiBs under varying health factors.

Figure 5d presents the lithium loss resulting from SEI layer growth. As the health factor rises, the amount of lithium consumed by SEI formation also increases progressively. Nevertheless, the rate of lithium loss exhibits a negative correlation with the health factor. This occurs mainly because a lower health factor corresponds to a higher current in the charging protocol, which elevates the average battery temperature and thereby accelerates SEI layer development. Conversely, higher charging currents reduce the time needed to reach 60% SOC. Thus, before 0.35 h, the lithium loss rate due to SEI growth is highest at a health factor of 5%. However, by the end of the charging process to 60% SOC, the total lithium loss attributed to SEI formation is greatest for LiBs with a 20% health factor. This can be explained by the strong dependence of SEI growth on both time and temperature, as described by Equation (5).

Figure 5e illustrates the lithium loss caused by lithium deposition. The results indicate that, under the four different health factors, the rate of lithium loss is highest during the early charging stages, and it gradually slows down over time. This trend is similar to the change in lithium plating current density shown in

Figure 5c, as the plating rate is highly correlated with the plating current density. Additionally, although the charging protocol with a health factor of 5% requires 0.07 h less to charge the battery to 60% SOC compared to the protocol with a health factor of 20%, the lithium loss caused by the former when reaching 60% SOC is 1.15 times greater than that of the latter. This highlights the critical importance of optimizing the charging protocol to prevent and reduce lithium deposition. It is widely recognized that both SEI layer growth and lithium deposition contribute to the loss of reversible lithium, which in turn directly causes a decline in battery capacity.

Figure 5f displays the capacity fade resulting from side reactions. As shown, the charging protocol with a 20% health factor yields the least capacity loss. Compared to protocols with health factors of 5%, 10%, and 15%, this approach reduces battery aging by 12%, 8.9%, and 5.6%, respectively. Moreover, given that lithium plating is the dominant aging mechanism under fast-charging conditions, the capacity fade trends in

Figure 5f align closely with the lithium loss profiles attributed to plating in

Figure 5e.

4.2. Analysis of the Impact of Charging Protocol Steps on Battery Aging

Considering both the charging time and the effect on suppressing battery aging, the charging protocol determined with a health factor of 15% is chosen as the standard charging protocol. Additionally, although multi-step charging protocols offer more advantages compared to conventional constant current constant voltage charging, the optimal combination has not yet been determined. Therefore, under the condition of a health factor of 15%, this study analyzes the impact of the number of charging steps on the electro-thermal behavior of LiBs, as shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 6a illustrates the current variation over time during the fast-charging process of the lithium-ion battery. With an increasing number of charging steps, the average current of the protocol rises, leading to a gradual reduction in the time required to reach 60% state of SOC.

Figure 6b presents the voltage profile versus time. Although the peak voltages for the three step counts are comparable, the average voltage reaches its highest value when using six steps.

Figure 6c displays the temperature change over time. Both the maximum and average battery temperatures increase as the number of steps grows.

Subsequently,

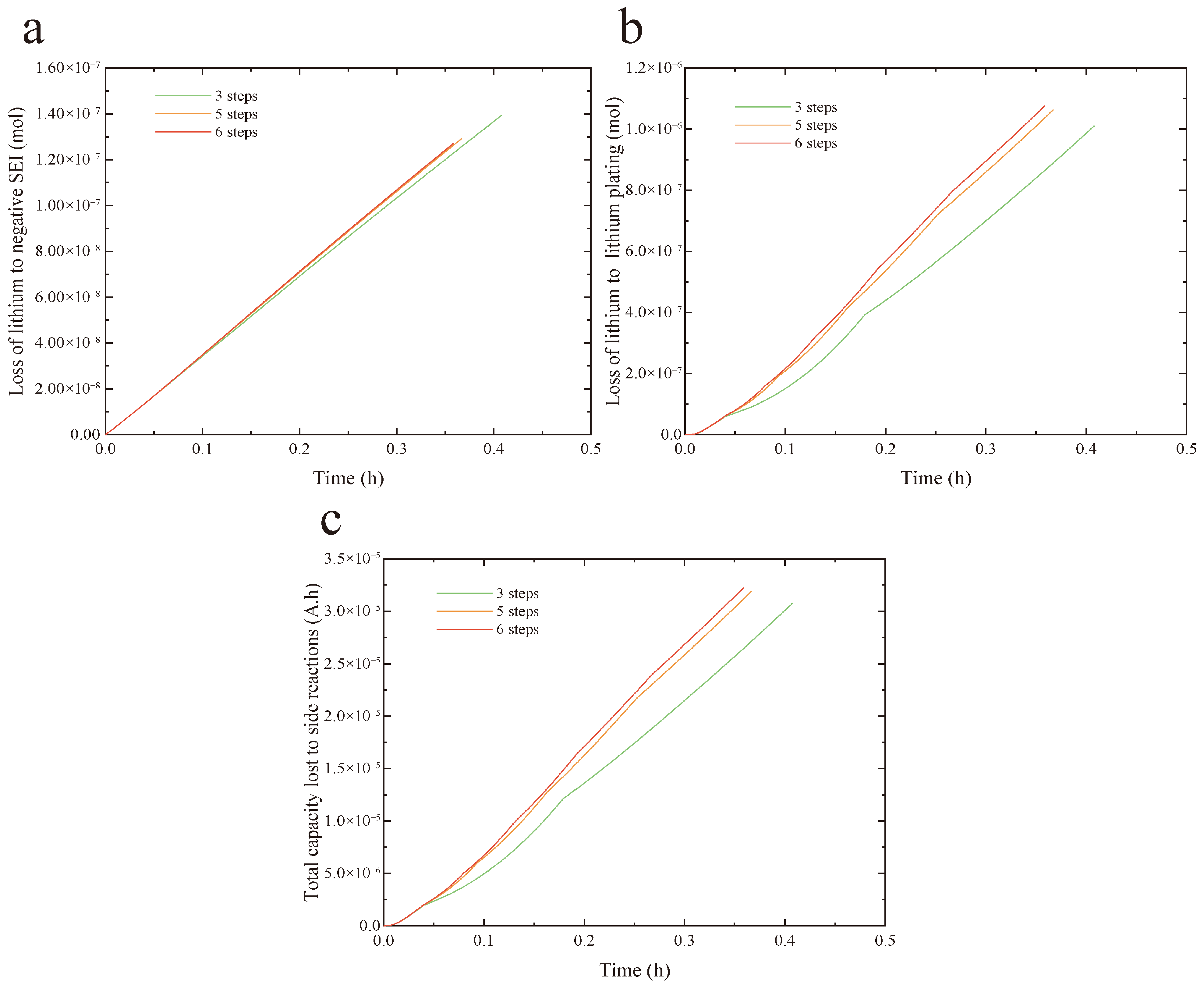

Figure 7 analyzes the impact of the number of charging steps on the aging behavior of LIBs.

Figure 7a shows the lithium loss caused by SEI layer growth. As the number of charging steps is reduced, the lithium loss attributed to SEI layer growth increases gradually, although the rate of loss declines. In comparison to the 6-step protocol, the 3-step protocol leads to a 9.4% greater lithium loss.

Figure 7b illustrates the lithium loss resulting from lithium deposition. With more charging steps, both the amount and the rate of lithium loss due to plating rise. The 6-step protocol causes a 6.6% higher lithium loss relative to the 3-step protocol.

Figure 7c presents the capacity fade caused by side reactions. As the step count increases, both the capacity loss and its rate progressively grow. The capacity degradation under the 6-step protocol is comparable to that of the 5-step protocol, yet it exhibits a 4.7% increase compared to the 3-step protocol.

Based on the previous experimental results, it is evident that while an increase in the number of charging steps leads to battery aging, fast charging can be completed in a shorter time. It is envisioned that by balancing the battery’s health and the fast charging time, a healthy FCS can be developed. Accordingly, this study increases the number of charging steps to an infinite level, implying that the FCS becomes dynamically adjustable and continuously follows the lithium deposition boundary across varying health conditions. To assess the performance of the health-aware FCS developed herein, a charging performance test was designed. During the test, the lithium-ion battery is first charged to 10% SOC at a 2 C rate and 25 °C, after which the proposed variable current profile (VCP)-based FCS is applied to charge the battery up to 60% SOC.

Figure 8 compares the electro-thermal aging behavior of batteries under the VCP strategy with four different health factors.

Figure 8a shows the current variation over time. The VCP charging curves under different health factors exhibit typical exponential decay, with a higher rate of decrease in the early stages of charging. However, as time progresses, the rate of decrease slows down, and the curve gradually flattens. Additionally, the lower the health factor, the higher the VCP charging current.

Figure 8b illustrates the voltage variation over time. Throughout the constant-current charging phase, the voltage increases sharply. However, owing to abrupt changes in current, the voltage rises most rapidly at a health factor of 5%. During the later charging stage, batteries with higher health factors exhibit more pronounced voltage increases, suggesting improved charging efficiency.

Figure 8c shows the temperature variation over time. When the VCP charging strategy is applied with a health factor of 5%, the battery temperature increases more rapidly, and the final temperature is higher than that of other health factors. In contrast, when the health factor is 20%, the VCP charging strategy results in better temperature control, with relatively less heat generation.

Figure 8d presents the lithium loss resulting from SEI layer growth. Under the VCP charging strategy with a 20% health factor, the rate of lithium loss due to SEI formation is the slowest. Nevertheless, owing to the comparatively extended charging duration, the total lithium loss from SEI growth is 11.2% higher than that observed with the 5% health factor VCP strategy.

Figure 8e depicts the lithium loss attributable to lithium plating. For the VCP strategy with a 5% health factor, the rate of lithium loss caused by deposition is the fastest. Despite having the shortest charging time, the total lithium loss from plating is 13.7% greater compared to the VCP approach with a 20% health factor. This indicates that optimizing the health factor can effectively mitigate aging induced by lithium deposition.

Figure 8f illustrates the overall capacity fade due to side reactions. A higher health factor corresponds to a reduced adverse effect of side reactions on the battery. For the VCP charging strategy with a health factor of 20%, the capacity loss is reduced by 9.78%, 7.03%, and 4.30% compared to the VCP charging strategies with health factors of 5%, 10%, and 15%, respectively. This further demonstrates that increasing the health factor helps reduce battery aging caused by side reactions.

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Different Fast Charging Strategies

To conclude, a cycle life test was carried out to examine the effect of the proposed fast-charging strategy on battery aging. During the aging experiment, the lithium-ion battery is initially charged to 10% SOC at a 2 C rate and 25 °C, then charged to 60% SOC using the chosen VCP fast-charging method. After a 30 min rest period, the battery is discharged to the lower cutoff voltage at a constant current of 0.5 C, followed by an additional 30 min pause. This aging procedure was repeated for 100 cycles. The constant current charging method, a widely used protocol, served as the control group with 2 C constant current charging in this study. For comparison, VCP strategies with health factors of 5% and 20%, along with an MCC strategy at a 5% health factor, were also applied to demonstrate the advantages of the proposed approach.

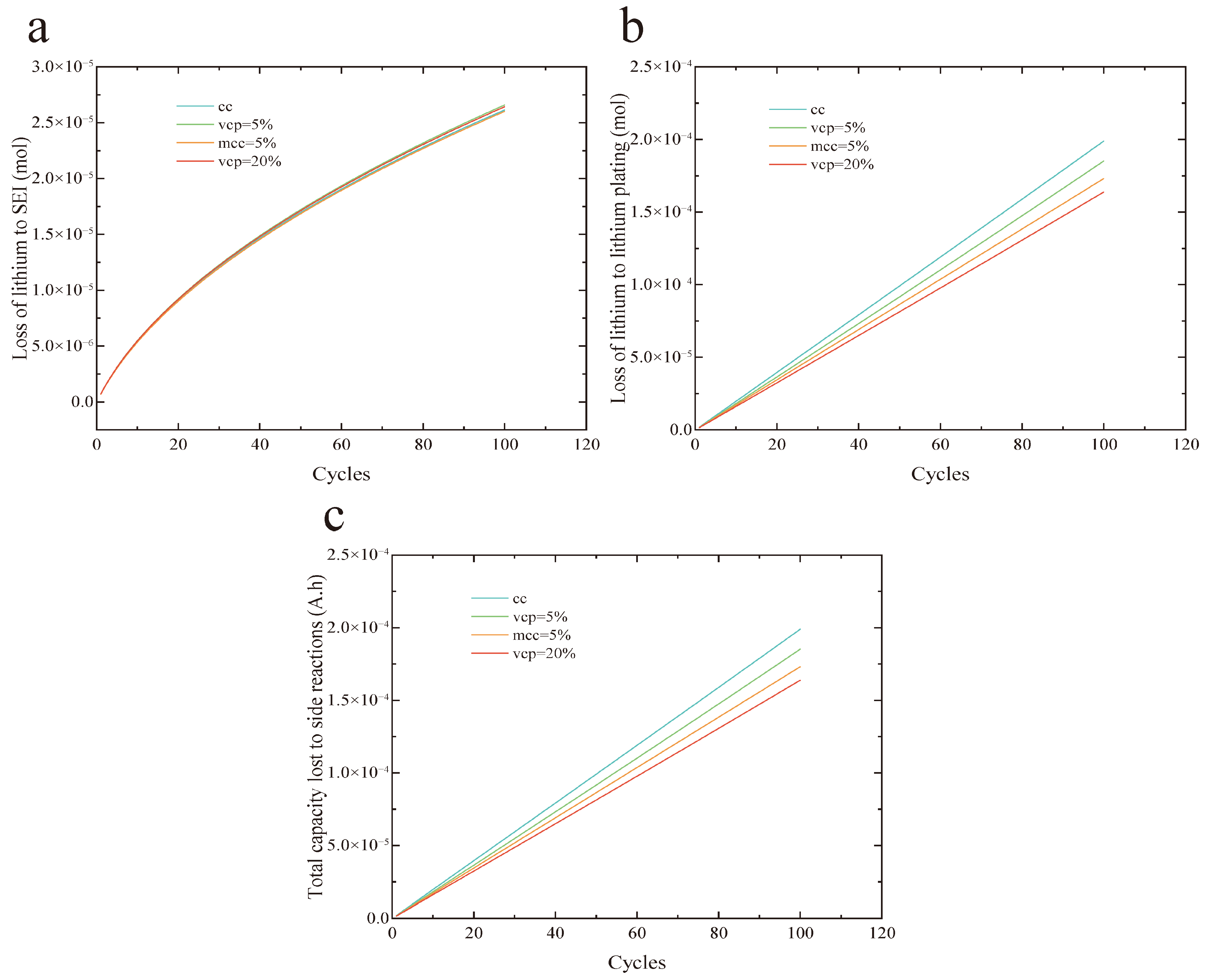

Figure 9 compares the outcomes of the 100-cycle test for the proposed fast-charging strategy.

Figure 9a displays the lithium loss attributed to SEI layer growth. The curves demonstrate a nonlinear upward trend, with particularly rapid lithium loss occurring in the early cycles. As cycling continues, however, the rate of capacity fade gradually decelerates. This pattern suggests that SEI formation is more aggressive initially, accompanied by heightened surface reactivity. As the layer stabilizes over time, its growth rate diminishes. The lithium losses resulting from SEI growth are 2.66 × 10

−5, 2.64 × 10

−5, 2.60 × 10

−5, and 2.62 × 10

−5 for the VCP strategies with 5% and 20% health factors, the MCC strategy with 5% health factor, and the 2 C constant current strategy, respectively. These values indicate that the lithium loss due to SEI growth is highly consistent across the different charging protocols.

Figure 9b depicts the lithium loss resulting from lithium plating. All curves indicate a gradual increase in lithium loss due to plating as the number of cycles rises. The lithium plating losses for the VCP strategies with health factors of 5% and 20%, the MCC strategy with a 5% health factor, and the 2 C constant current strategy are 1.85 × 10

−4, 1.64 × 10

−4, 1.73 × 10

−4, and 1.99 × 10

−4, respectively. Relative to the 2 C constant current method, the VCP strategy with a 20% health factor reduces lithium plating-induced capacity loss by up to 17.59%.

Figure 9c presents the capacity fade caused by side reactions. The capacity losses for the same set of strategies are 5.68 × 10

−3, 5.1 × 10

−3, 5.34 × 10

−3, and 6.03 × 10

−3, respectively. Notably, the VCP strategy with a 20% health factor achieves a reduction in capacity loss of up to 15.4% compared to the 2 C constant current approach. These results demonstrate that the health-aware fast-charging strategy proposed in this study effectively mitigates battery aging by suppressing lithium deposition.