1. Introduction

With the rapid development of technology, energy consumption has grown dramatically, and carbon emissions from traditional fossil fuels have caused numerous environmental problems [

1]. As a major energy consumer in the transportation industry, the rail transit system is required to consume green energy. In recent years, the decarbonization of railway systems has also become a hot topic of research [

2]. Hydrogen energy has obvious advantages, such as low carbon emissions and high calorific value, and has become the ideal solution for decarbonization in many fields [

3]. Therefore, in rail transportation, hydrogen energy-based locomotives have become the preferred choice for the energy transition away from traditional diesel locomotives [

4].

The railway hydrogen energy self-sufficient supply is an important component in the large-scale application of hydrogen energy in the railway system [

5]. Currently, more than 1600 hydrogen refuelling stations have been deployed worldwide, and green hydrogen stations are increasing rapidly. Germany has combined wind power, electrolysis, and liquefaction processes to reduce the production cost of green hydrogen to 3.5 euros per kg. Its 200 MW-scale green hydrogen plant has achieved continuous and stable operation, validating the feasibility of large-scale production of green liquefied hydrogen. Meanwhile, Toyota Motor Corporation has established a hydrogen energy supply to demonstrate the commercial application level [

6,

7]. Meanwhile, the Sixth Academy of China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation, Zhongke Hydrogen Technology Co., Ltd., and the Chinese Academy of Sciences have developed renewable energy hydrogen production, hydrogen energy conversion, and system integration [

8]. Yet, the real hydrogen energy-based self-consistent hydrogen energy system faces numerous challenges [

9]. On the renewable energy side, wind and solar power output are subject to significant fluctuations due to environmental conditions. On the energy consumption side, the complexity of system coupling is amplified by the time-varying industrial energy consumption and environmental conditions. With the introduction of hydrogen-powered rail systems, the energy consumption requirements of large-scale hydrogen-powered rail systems will further increase dynamic coupling characteristics [

10,

11,

12]. To achieve cost-effective hydrogen-powered railways, integrating the energy generation, storage, and utilization within a self-consistent hydrogen energy system to achieve multi-energy flow coordination optimization, has become a focus of transportation-energy integration research [

13,

14,

15].

Therefore, a multi-energy flow coordination optimization system for industrial parks has been constructed. The comprehensive multi-energy flow system utilizes fluctuating power sources, such as wind and solar energy, along with the flexible adjustment capabilities of gas turbines and energy storage, to enhance energy utilization efficiency and increase renewable energy penetration rates [

16]. However, the energy system fails to consider the hydrogen-powered railway systems. For hydrogen-powered railway systems, it is necessary to combine the characteristics of hydrogen-powered locomotives [

17]. Hence, a hydrogen energy-based locomotive system was designed with economic considerations to improve the efficiency of the system [

18]. From the analysis, incorporating a multi-energy flow system in hydrogen-based locomotives would enhance their efficiency and environmental performance. The PEM fuel cell with ammonia–water cooling cycle system is integrated into the multi-energy system [

19]. However, as the energy demand for hydrogen energy-based locomotives gradually increases, large-scale hydrogen use will require the introduction of tank cars and pipelines [

20]. Tank cars have become the solution for self-consistent hydrogen energy parks for hydrogen energy-based railways due to their flexibility, adaptability, and cost-effectiveness [

21]. Nevertheless, the tank car, as an important mobile energy storage device, faces increased system uncertainty and complexity due to differences in hydrogen locomotive scheduling tasks and mileage, as well as vehicle type and charging time. To address uncertainties in arrival times and charging demands, Ren et al. considered an adaptive data-driven set to describe the randomness [

22]. In addition, the artificial intelligence-based control was also introduced for the vehicle-to-grid system [

23]. This effectively captured the multimodal characteristics of the data and optimized charging strategies, thereby achieving optimization for industrial parks at the electric vehicle charging level. A comprehensive energy system model was established that incorporates tank cars, treating them as part of a multi-energy flow system, thereby further optimizing the energy demand within the park [

24]. Nevertheless, the introduction of tank car coupling of complex hydrogen park units would result in the curse of dimensionality, uncertainty, and high nonlinearity.

A flexible optimization method is proposed for electric vehicles based on a charge–discharge model and conducted simulation analyses in conjunction with a power system day-ahead optimization model [

25]. The results indicate that accurate modelling with rule-based optimization can achieve optimization results. Given that the operation of tank cars is highly correlated with the scheduling of hydrogen-powered locomotives and is also influenced by the tank car, the complexity and uncertainty are even more diverse [

26]. Hence, the metaheuristic optimization is introduced to operate the schedule of a multi-energy system [

27]. However, the metaheuristic optimization is complex, which results in a lack of adaptability for the reliability and economic efficiency of the system. With the development of artificial intelligence in recent years, intelligent optimization algorithms have been introduced for complex and uncertain multi-energy flow systems in industrial parks. The genetic algorithms, particle swarm algorithms, and simulated annealing algorithms are introduced for the optimization [

28,

29]. However, the above methods are affected by parameters and are prone to local optima. Therefore, the Grey Wolf algorithm is introduced into system optimization due to its stronger global search capabilities and fewer parameters, which is desirable for the uncertain and nonlinear hydrogen-powered railway energy park system [

30]. Given that the self-consistent hydrogen energy park system for hydrogen energy-based rail tank car is more complex and dynamic, designing a hydrogen energy park-based grey wolf algorithm that integrates adaptive adjustment mechanisms has become an effective way to improve reliability and efficiency.

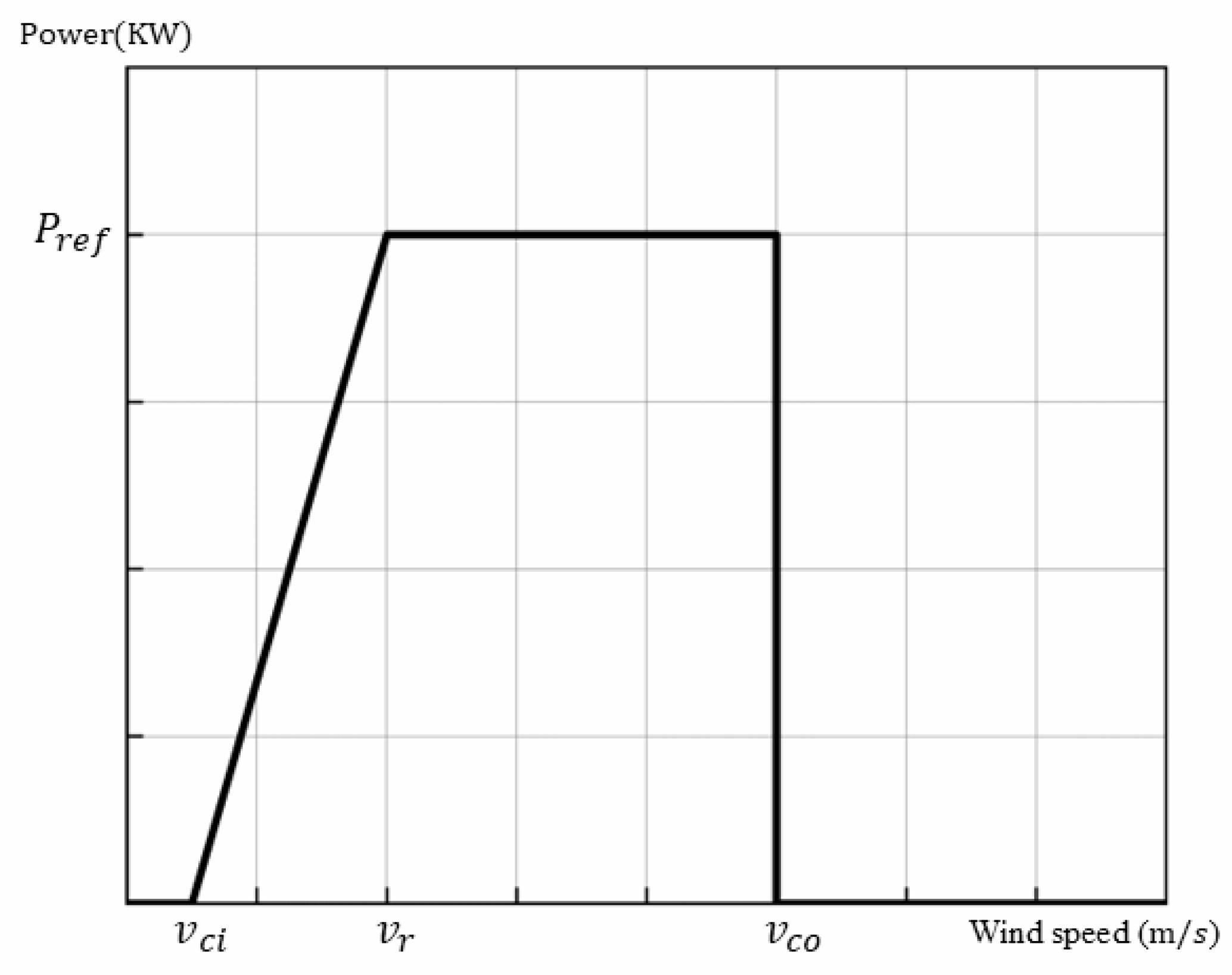

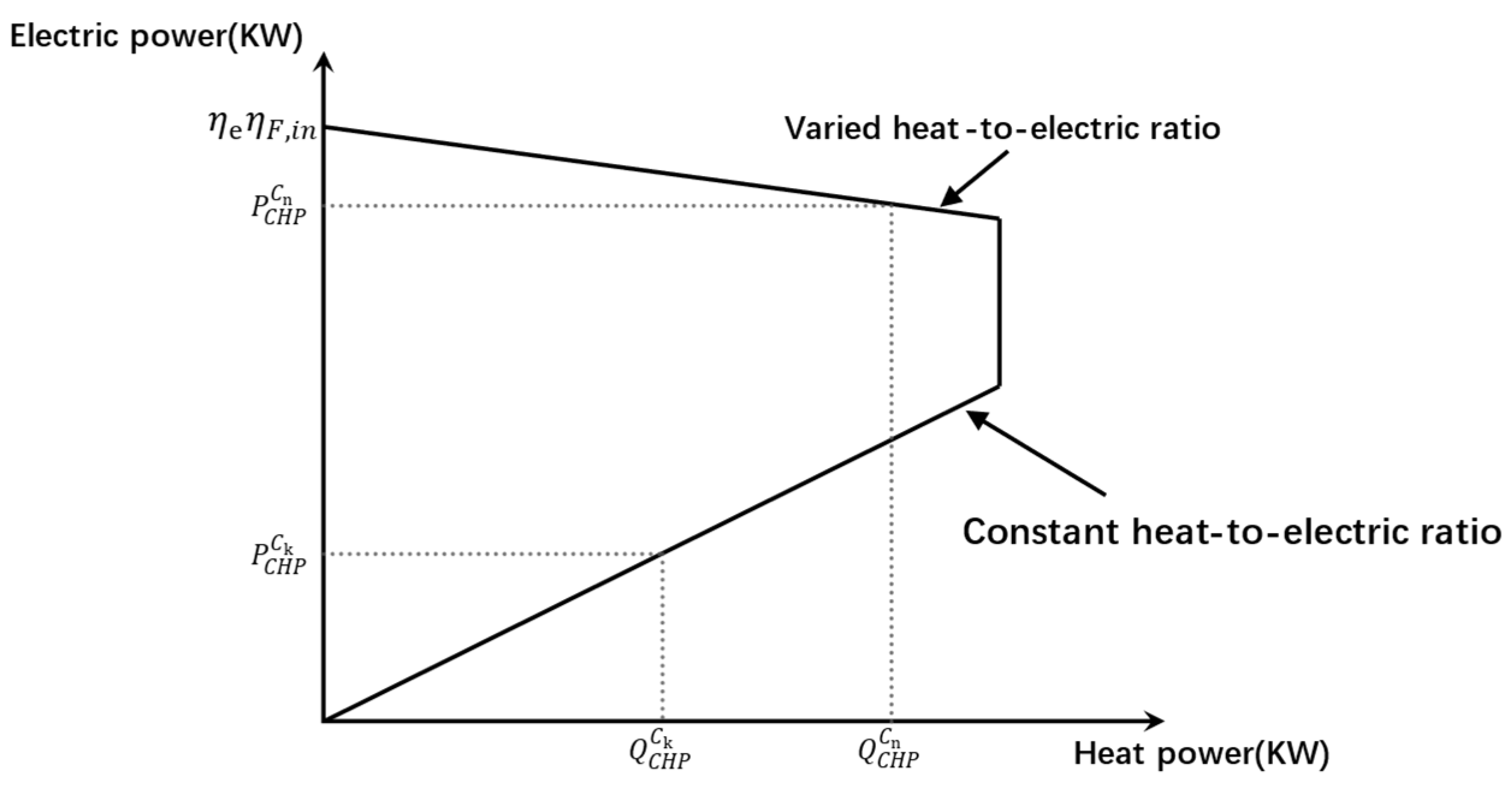

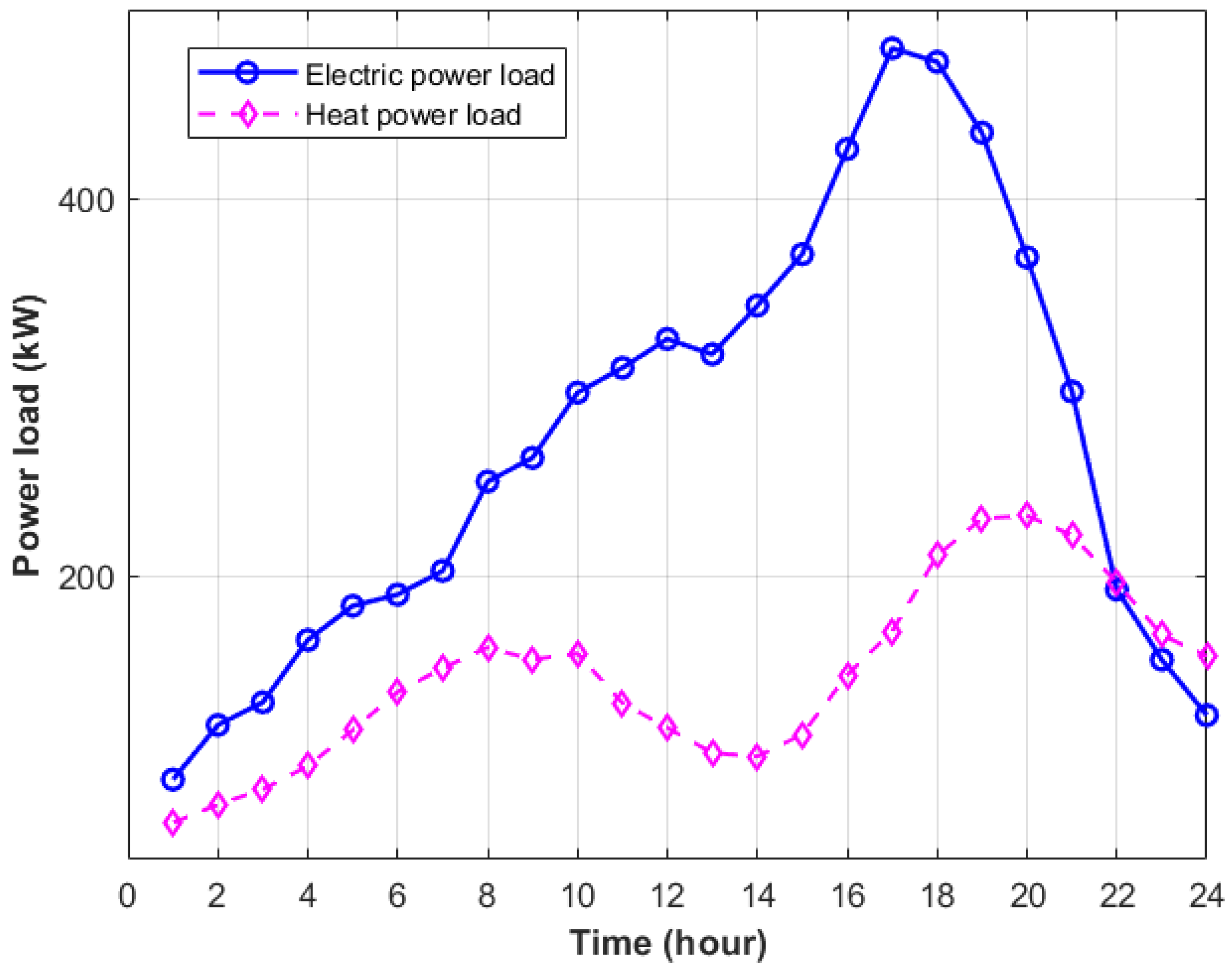

In this paper, we present a self-consistent multi-energy flow coordination optimization method for hydrogen-powered railway tank car transportation in hydrogen energy parks. First, a multi-energy flow system integration model was established for the hydrogen-powered railway system, encompassing green non-dispatchable units such as wind power and photovoltaic systems, as well as dispatchable units such as fuel cells, gas boilers, and combined heat and power (CHP) units. An optimization scheduling model was developed to minimize the daily operating costs, incorporating hydrogen-powered railway tank car transportation. The model parameters were then optimized based on actual operational data. Given the diversity and complexity of actual tank car operations, a probabilistic model of daily charging behaviour was constructed using a Monte Carlo simulation to simulate actual tank car operations. For the multi-energy flow system of self-consistent hydrogen energy parks for hydrogen energy-based railways, we developed a Dynamic Adaptive Grey Wolf Optimization (DA-GWO) algorithm. Through a parameter self-adaptive adjustment mechanism, the algorithm’s global optimization capabilities have optimized the whole system. The innovations of this paper are as follows:

- (1)

The tank car loads were first introduced into a self-consistent hydrogen energy park, multi-energy flow coordinated optimization, and an innovative multi-energy flow coordinated optimization for hydrogen railways.

- (2)

A multi-energy flow optimization model for hydrogen energy-based railways was constructed, and parameters were optimized for actual scenarios.

- (3)

A dynamic adaptive grey wolf algorithm was proposed for hydrogen energy-based railways, optimizing system costs and improving the reliability of system optimization.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 establishes an optimization scheduling model with the consideration of hydrogen energy-based railways.

Section 3 introduces the proposed DA-GWO algorithm.

Section 4 verifies the effectiveness of the optimization method for optimization scheduling.

Section 5 presents the conclusions.

3. Multi-Energy Flow Park Dynamic Adaptive Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm for Hydrogen-Powered Rail Tank Car Transportation

3.1. Grey Wolf Algorithm

The Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) is a swarm intelligence optimization algorithm inspired by the hunting behaviour of grey wolf packs in nature [

33]. The hunting behaviour, the strict hierarchical structure (

α,

β,

δ wolf), and collaborative hunting mechanisms (encirclement, pursuit, and attack) within a grey wolf society inspired the efficient search for the optimal solution of a function. Compared to the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and genetic algorithm (GA), the grey wolf algorithm has the advantages of fewer parameters, faster convergence speed, and a strong balance between global exploration and local exploitation. It can better balance local optimization and global search, and has performed excellently in power system economic dispatch, wind–solar storage optimization configuration, and power plant combination problems.

3.1.1. Hierarchy

Grey wolves are social animals in the wild, with a strict social hierarchy. The wolf pack is divided into four ranks: alpha wolf (α), beta wolf (β), delta wolf (δ), and omega wolf (ω). The alpha wolf is responsible for leading the pack in hunting and decision-making activities and holds the highest status within the pack, representing the current optimal solution. The beta wolf assists the alpha wolf and can replace the alpha wolf when necessary, representing the second-best solution. The base wolves follow the commands of the alpha and beta wolves, representing the third-best solution, while the ordinary wolves occupy the lowest rank in the pack hierarchy. They follow the leadership of other ranks during hunting and execute corresponding tasks.

3.1.2. Surround the Prey

During the pursuit, the grey wolf pack typically surrounds the prey first. The mathematical model of this behaviour can be expressed as:

where

t indicates the number of iterations in the current iteration.

A and

C are the cooperation coefficient vectors, and

D is the distance between the grey wolf and the prey.

represents the position of the prey in the

t iteration, and

represents the position vector of the grey wolf in the

t iteration. The formulas for calculating the coefficient vectors

A and

C are as follows:

where

decreases linearly from 2 to 0 with the number of iterations,

and

are random vectors,

is a vector with each dimension equal to 1, and each dimension follows a uniform distribution U (0,1).

3.1.3. Pursuit

Grey wolves are capable of identifying the location of prey and surrounding them. Hunting is typically led by the alpha wolf, with beta and delta wolves occasionally participating as well. In each iteration, the three optimal solutions obtained so far are saved, forcing other wolves (including gamma) to update their positions according to the optimal search location using the following formula:

where

,

, and

represent the position vectors of

α,

β, and

δ in the current iteration, respectively,

is the position vector of the individual in the

t iteration,

,

, and

are random vectors,

,

, and

represent the distances between other individuals in the population and

α,

β, and

δ, respectively,

is the updated position vector of the individual.

The figure below shows how

ω wolf or other wolves (candidate wolves) update their positions based on the positions of

α,

β, and

δ wolves in the two-dimensional search space. As shown in

Figure 5, the final position will be a random position within the circle defined by the positions of the

α,

β, and

δ wolves in the search space. In other words, the

α,

β, and

δ wolves estimate the prey’s position, and the other wolves randomly update their positions around the prey.

3.1.4. Attack the Prey

Grey wolves complete their hunt by attacking their prey when it stops moving. Attacking the prey determines its location. This process is mainly achieved through the iterative process of decreasing the convergence factor a from 2 to 0. Thus, after the iteration is complete, the group obtains the optimal solution.

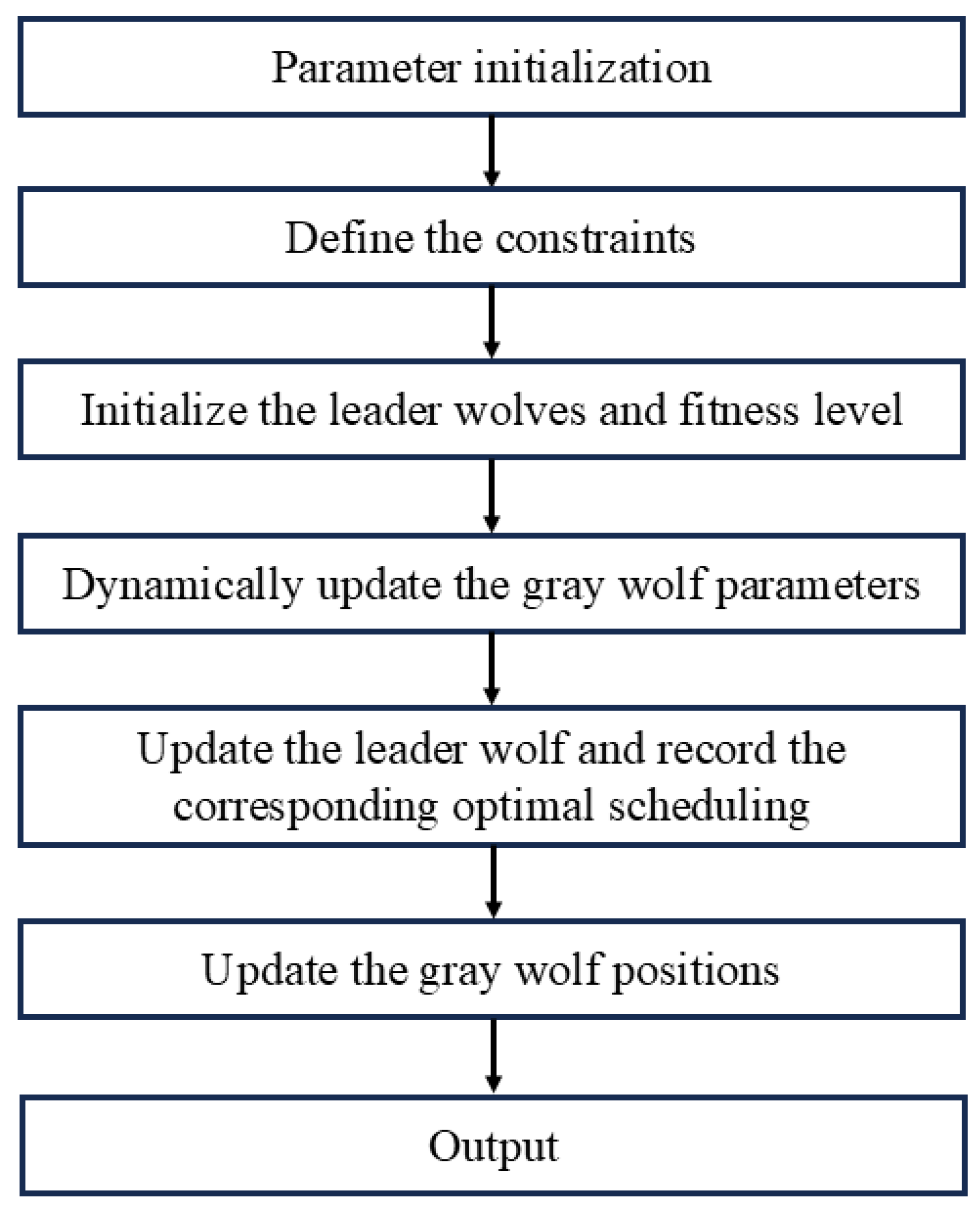

3.2. Dynamic Adaptive Grey Wolf Algorithm and Optimized Scheduling

To address the shortcomings of traditional GWO in scheduling problems, where convergence tends to occur prematurely, the GWO algorithm can be improved by increasing control parameters or changing the way control parameters are updated. On this basis, this paper combines the advantages of other algorithms to further improve the optimization and solution process of the GWO algorithm, proposing the Dynamic Adaptive GWO (DA-GWO) algorithm, which introduces the following strategies.

Nonlinear adjustment of the convergence factor α: In traditional GWO algorithms, the linear decrease in the convergence factor makes the transition from global search to local development insufficiently flexible, easily leading to early convergence to a local optimum or incomplete search in the later stages. Therefore, a Sigmoid function is used for nonlinear adjustment:

By adjusting the parameter, the initial α value can be rapidly reduced to maintain the exploratory nature of the wolf pack and avoid prematurely settling into a local optimum. In the later stages, as the α value changes more gradually, this ensures a more thorough local optimization process, thereby improving convergence accuracy. By introducing nonlinear adjustments to balance global search with local exploration, the algorithm avoids stagnating in suboptimal solutions in complex scheduling scenarios.

Implement dynamic leader weight allocation for position updates: In traditional GWO, the position update weights of

α,

β, and

δ wolves are equal, which does not fully utilize the superiority and inferiority information of leaders. Through fitness dynamic weight allocation:

By assigning a higher weight to the alpha wolf, i.e., the optimal solution, the development of high-potential areas can be accelerated. This helps to highlight the dominant role of the alpha wolf when there are large differences in fitness, while preserving diversity when differences are small.

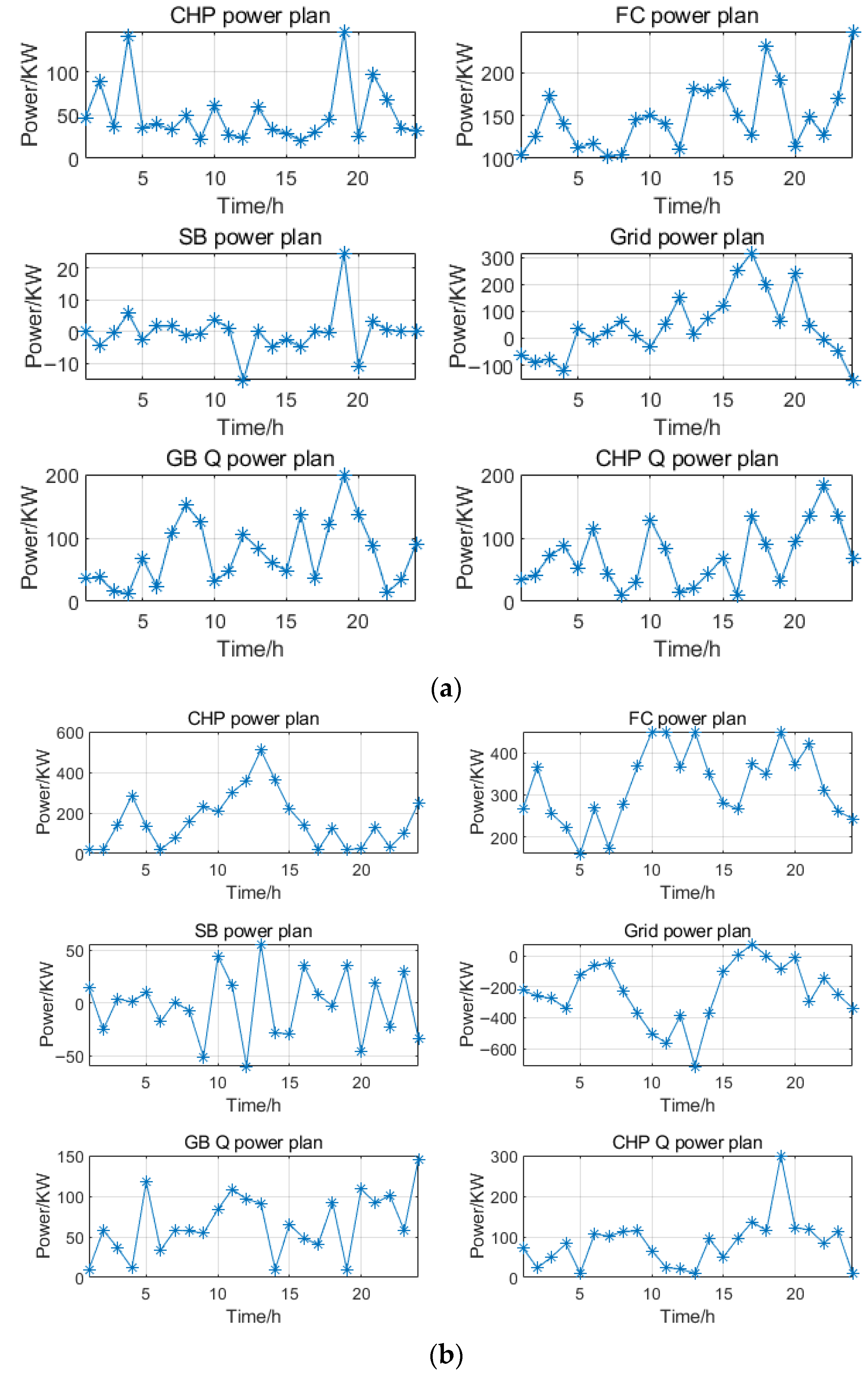

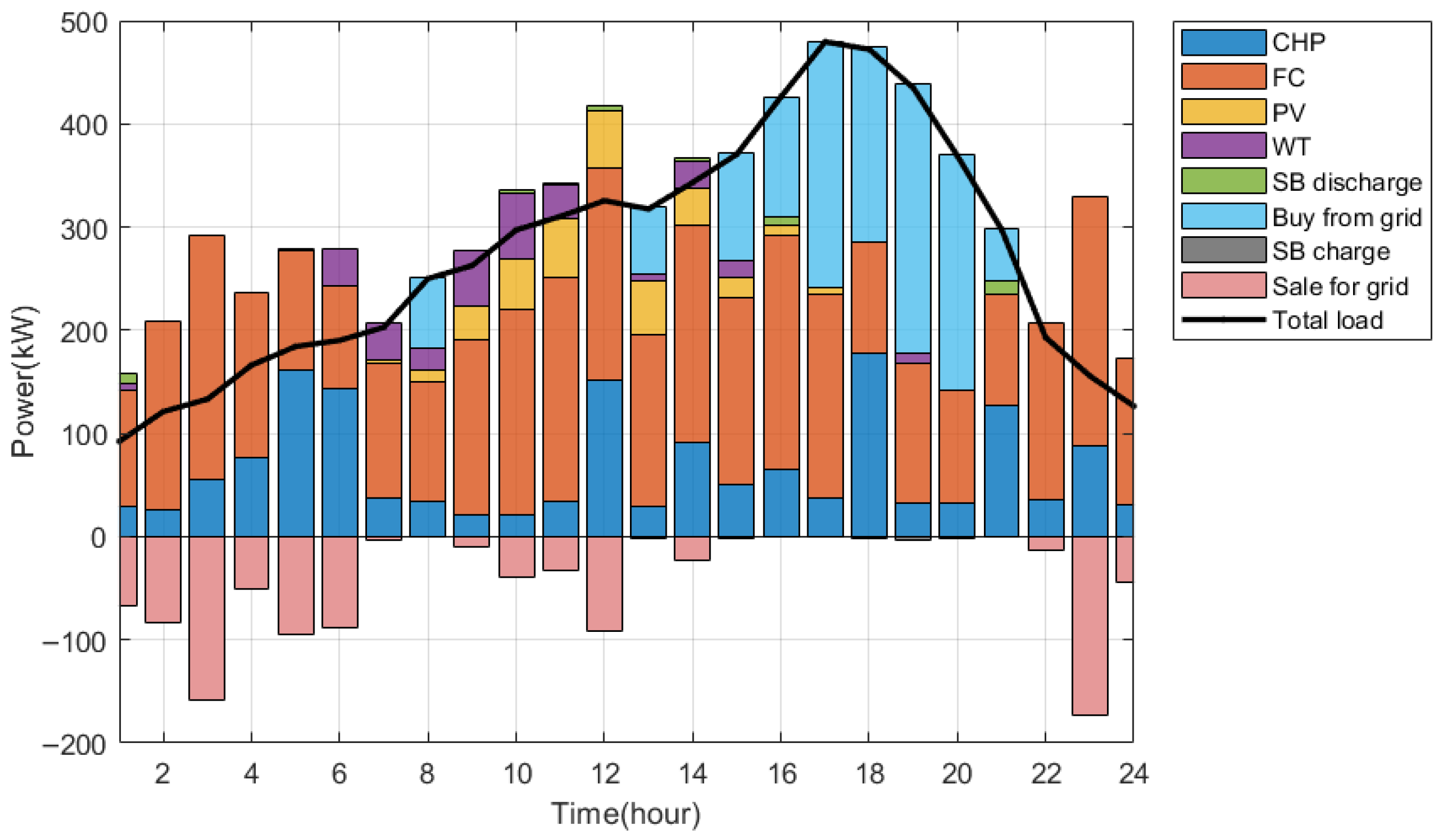

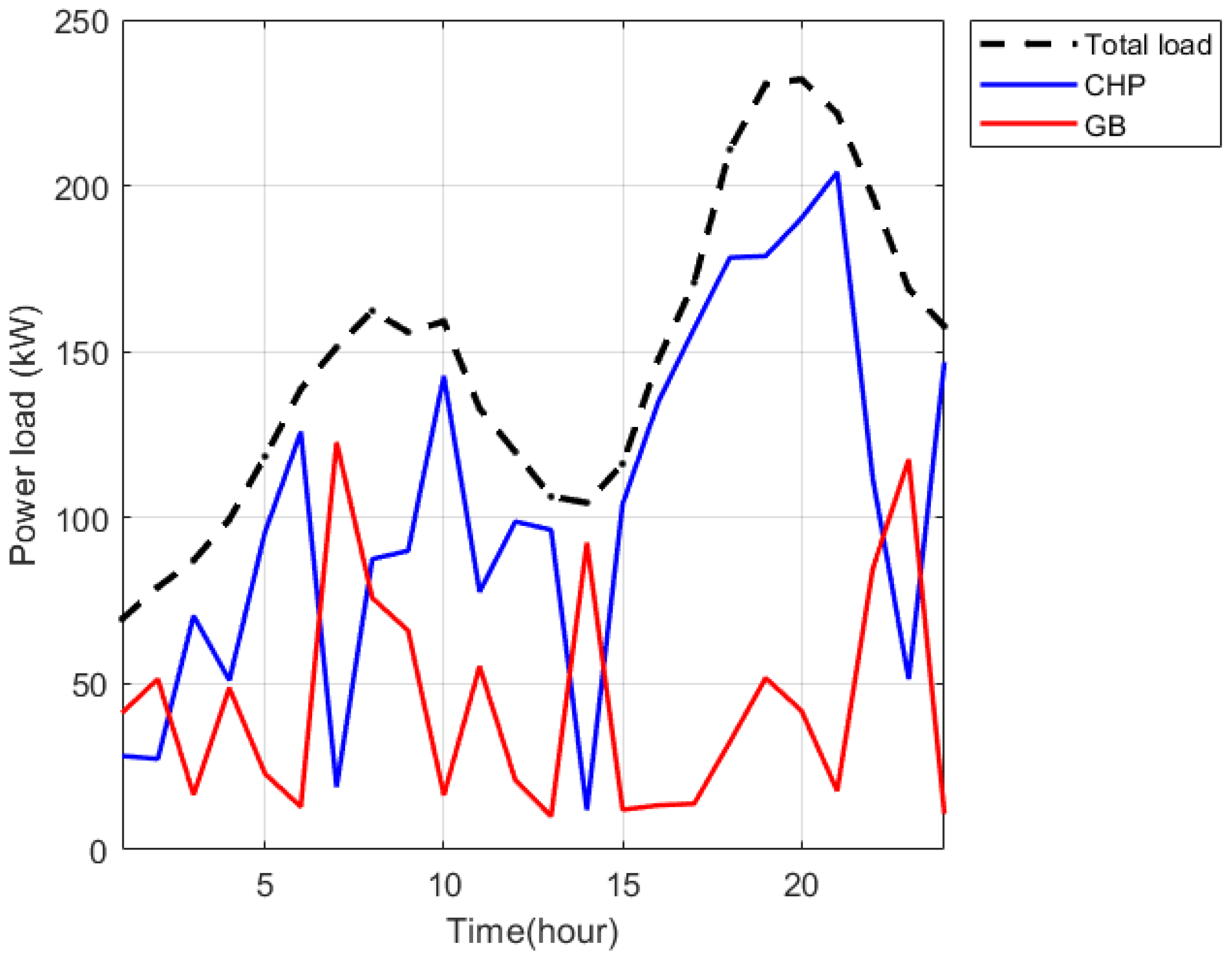

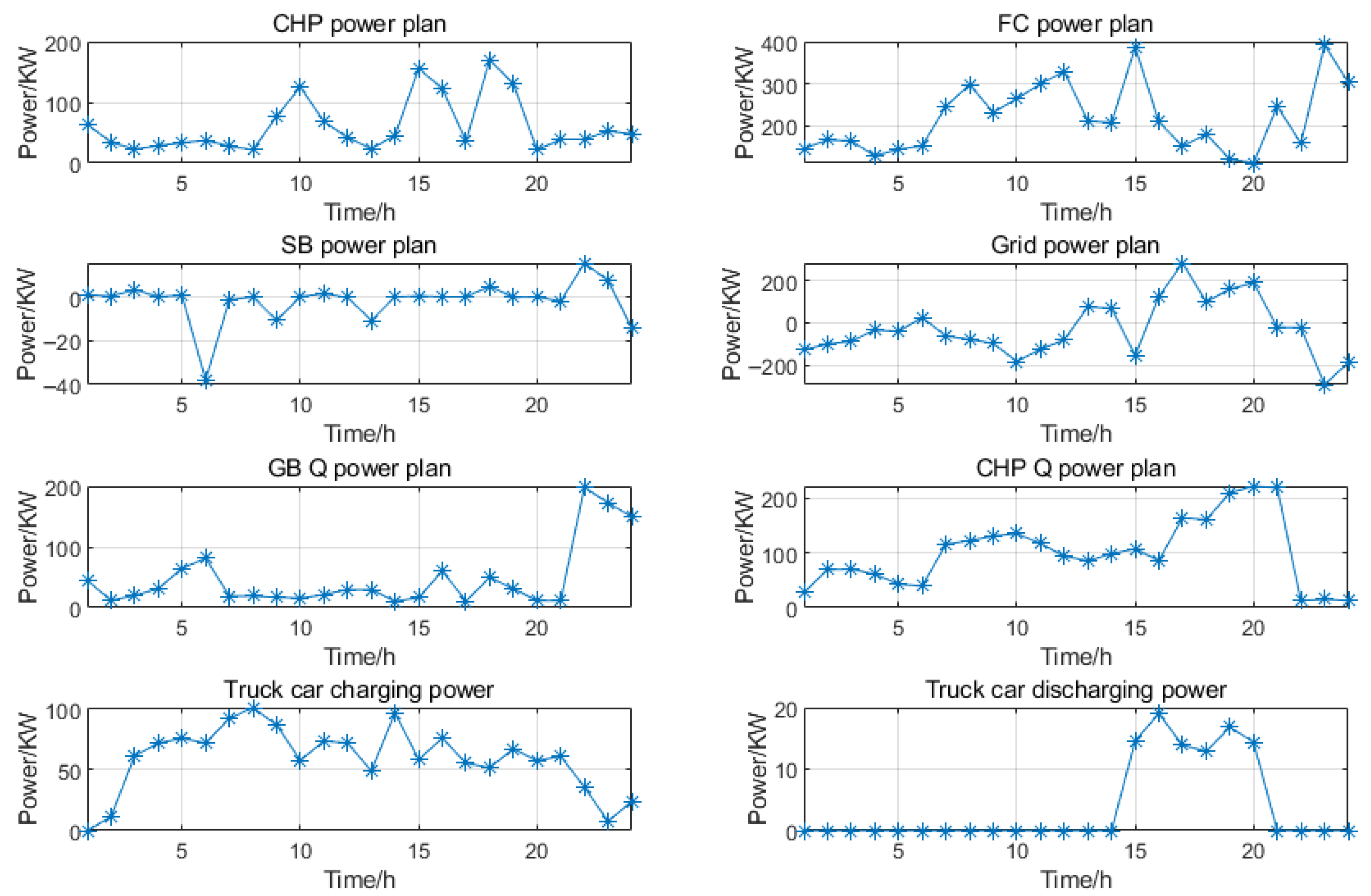

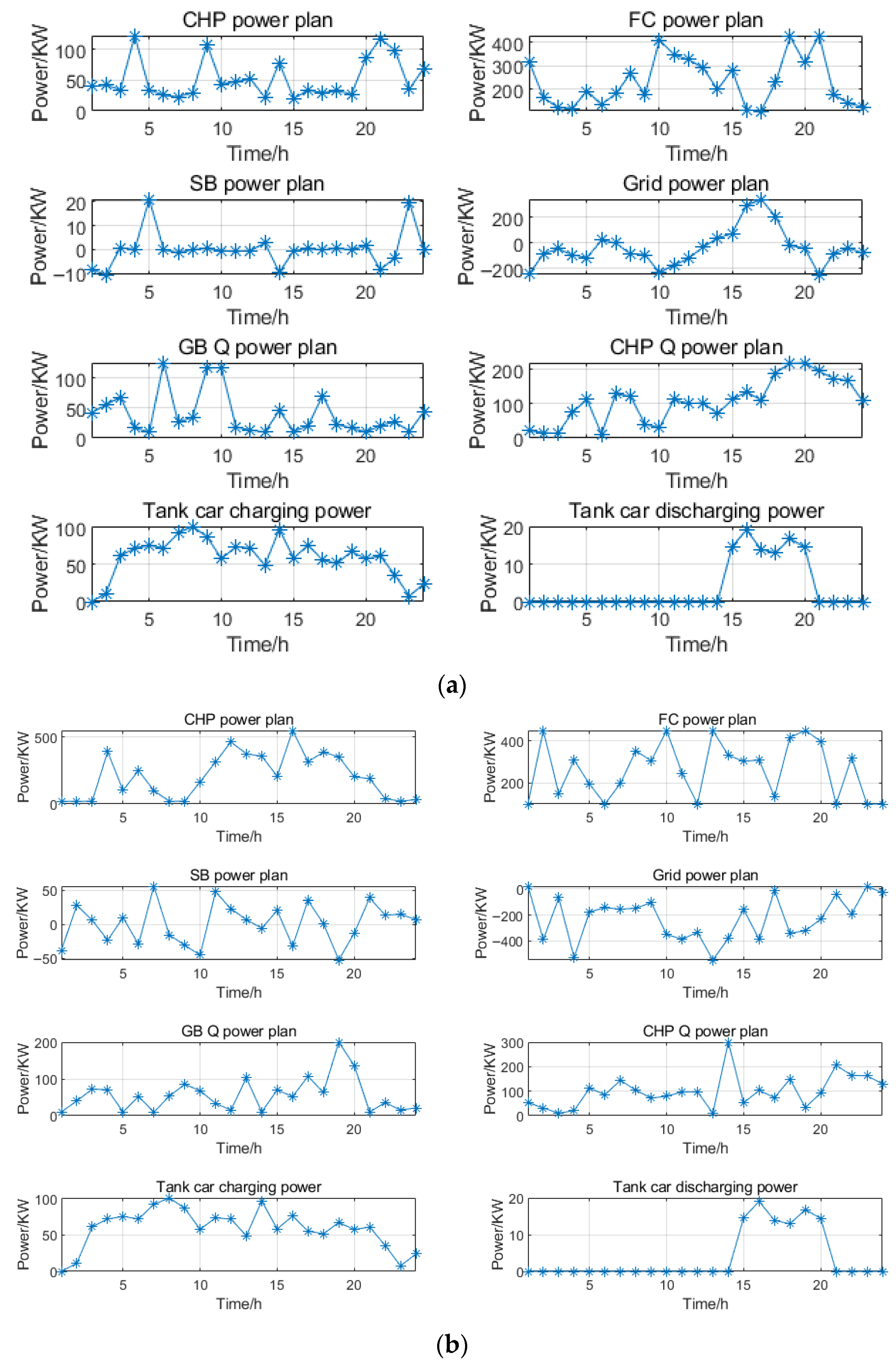

For the optimization scheduling of multi-energy flow systems in industrial parks targeting hydrogen-powered railway tank cars, it is first necessary to define a fitness function to calculate the fitness value of each candidate solution (wolf position) in the grey wolf algorithm. The calculated fitness value corresponds to the minimized total cost of the optimization scheduling model, which includes direct costs and penalty terms. Direct costs include CHP power generation and heating costs, fuel cell costs, grid power purchase and sale costs, and gas boiler costs. Penalty costs include penalty terms for ramping constraints of each equipment unit and penalty terms composed of thermal decay and thermal waste.

The fitness value in the DA-GWO algorithm is determined by the position vector of the grey wolf algorithm. The 96 dimensions of the position vector are defined as the power scheduling plan for four types of equipment over a 24 h period. By solving the position vector of the grey wolf using the DA-GWO algorithm, the power scheduling plan corresponding to the minimum cost can be determined. As shown in the operational cost calculations, as the aforementioned, an optimized scheduling scheme must not only meet electricity and heat power demands but also be constrained by unit operational constraints. Therefore, during the solution process, it is necessary to set position boundaries for the DA-GWO algorithm and impose constraints on the units via penalty terms. First, the 96-dimensional position boundaries are set to directly constrain the range of the solution vector, corresponding to the upper and lower limits for each unit. After each position update of the DA-GWO algorithm, a position check is performed, and any values exceeding the boundaries are forcibly truncated to ensure that the units operate within a reasonable range.

In summary, the steps for solving a multi-energy flow system using the DA-GWO algorithm are as follows.

Perform parameter initialization: Define the scheduling cycle, define the number and type of devices, define cost parameters, grid electricity purchase and sale price tables, and penalty costs; define constraints: device power upper and lower limits, ramp rate limits, and energy storage limits.

Grey wolf algorithm initialization: initialize grey wolf parameters, including maximum iteration count, wolf pack size, solution vector dimension dim = 96 (4 devices × 24 h), and define upper and lower bounds; generate initial population satisfying upper and lower bound constraints; initialize leader wolves (α, β, and δ) and their fitness values (set to infinity).

Iterative optimization: When the number of iterations is less than a given value, dynamically update the grey wolf parameters. By calculating the fitness (total cost) of each wolf, force the solution vector Positions [i] to be truncated within the range [lb, ub]. Call the fitness function fitness1 (Positions [i]) to calculate the total cost, including the costs of each unit, GB, and waste heat, as well as the penalty term. Update the leader wolf and record the corresponding optimal scheduling results. Simultaneously update the grey wolf positions (moving toward α, β, and δ) and record the current optimal cost for plotting the convergence curve.

Output results: Output the minimum cost αscore; output the optimized scheduling results for each unit, including CHP electrical power, FC power, SB charging/discharging power, and GB thermal power.

The algorithmic flowchart is shown in

Figure 6.

5. Conclusions

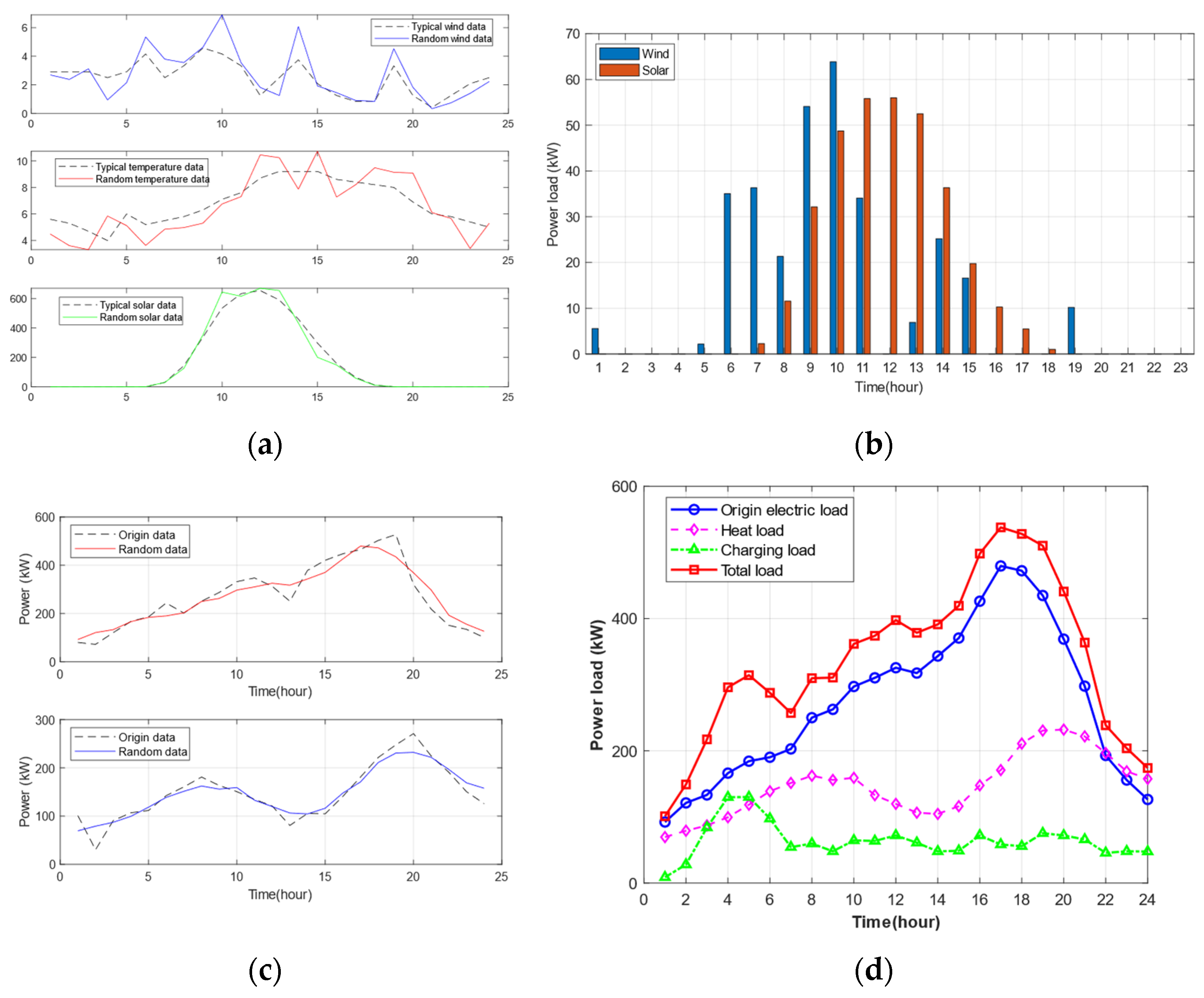

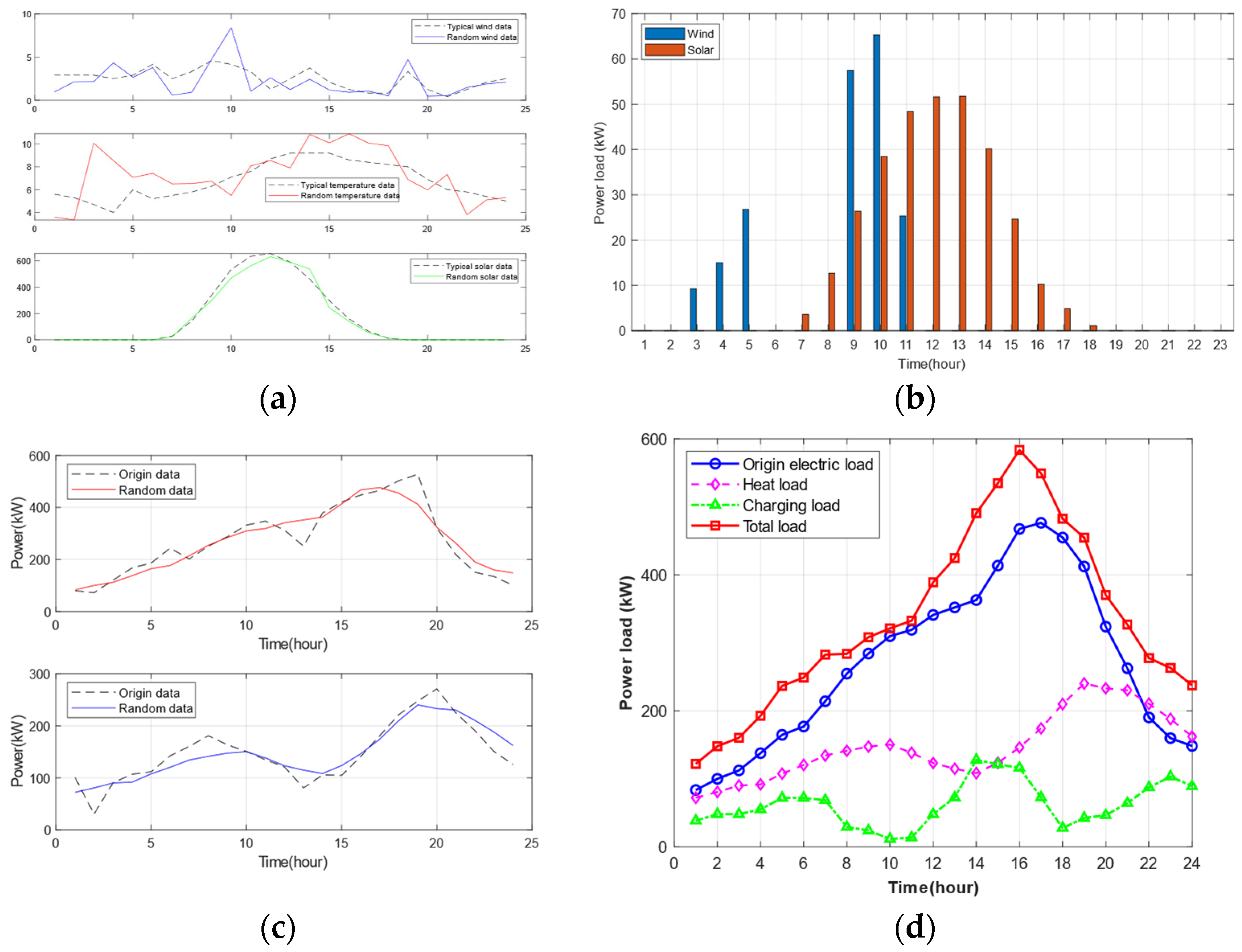

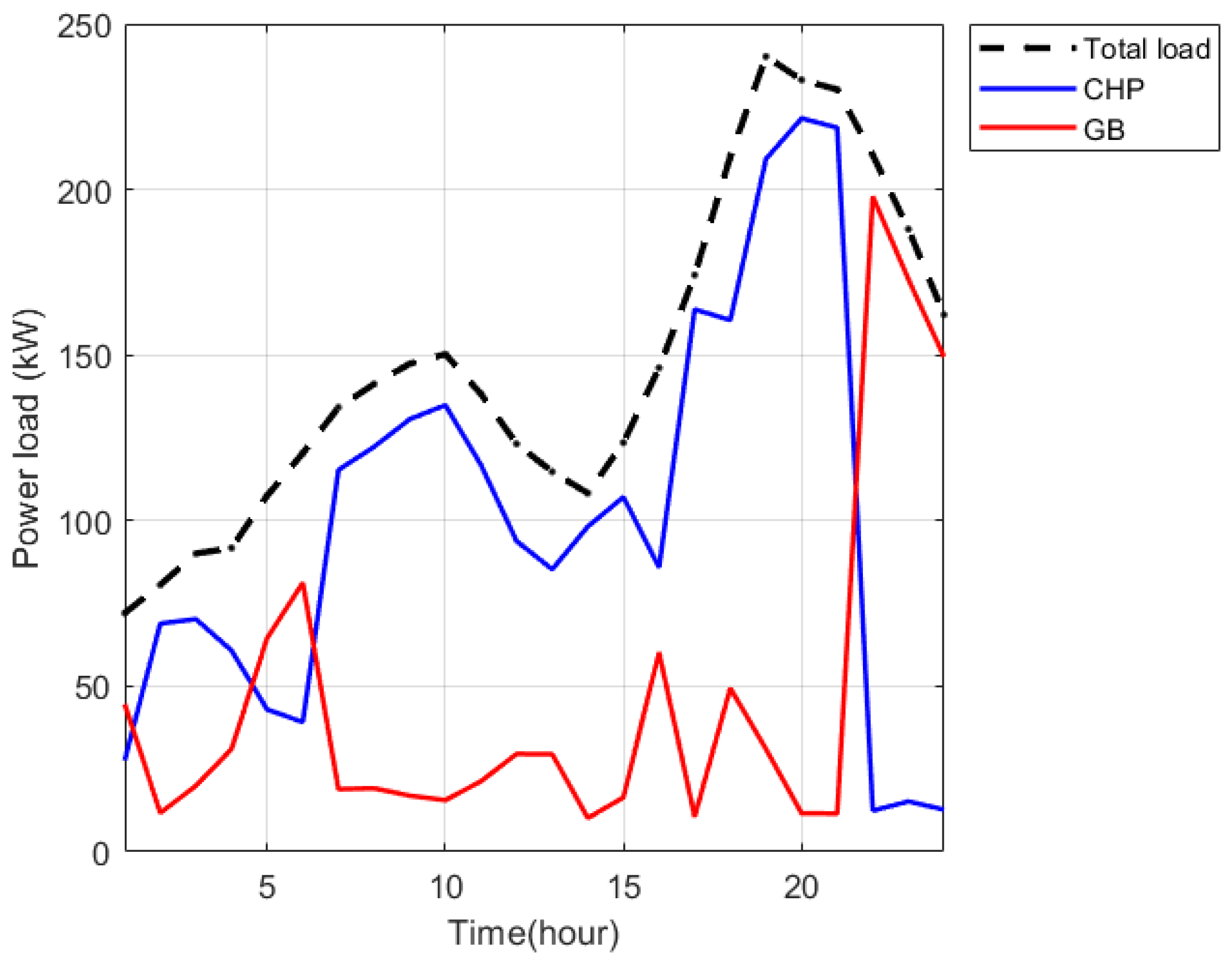

This paper investigates the problem of self-consistent multi-energy flow coordination and optimization scheduling for hydrogen-powered railway tank car transportation in hydrogen energy parks. It constructs a modelling framework based on multi-energy flow coordination optimization and an optimization scheduling method based on the DA-GWO approach. By establishing an energy flow model, the study develops basic models for non-dispatchable units such as wind power and photovoltaic systems, as well as dispatchable equipment including fuel cells, gas boilers, CHP units, and energy storage systems. Additionally, considering the characteristics of tank cars, a charging load model is proposed using the Monte Carlo simulation method, incorporating charging and discharging mechanisms, to establish an optimization scheduling model aimed at minimizing the total operating cost over a single day. Based on the constructed model, the DA-GWO method was designed to achieve optimal scheduling by comprehensively considering environmental characteristics, operating modes, and energy transfer constraints. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, this paper selected the load characteristics of electricity and heat in a coastal industrial park in China to optimize the model parameters. Based on the constructed model, this paper considered two scenarios: tank cars as load terminals and tank cars as both energy storage and load terminals. The results show that the proposed method can achieve multi-energy flow coordinated optimization scheduling in the industrial park.

In the future, we will further focus on the limitations of our study. 1. We will improve our methods to deal with the non-deterministic problem. 2. We will focus on longer periods of the park system for hydrogen-powered railways instead of single-day optimization. 3. We will improve the Monte Carlo method to adapt to more difficult operation conditions. 4. We will study energy unit modelling in detail, combining with health status, tank safety, and hydrogen constraints with the renewable energy availability (such as cloudy or less windy days) to further model the whole system. 5. We will also study the CO2 emissions for the whole system.