4.1. Determination of the Functional Relationship Between Crossarm Strain and Conductor Displacement

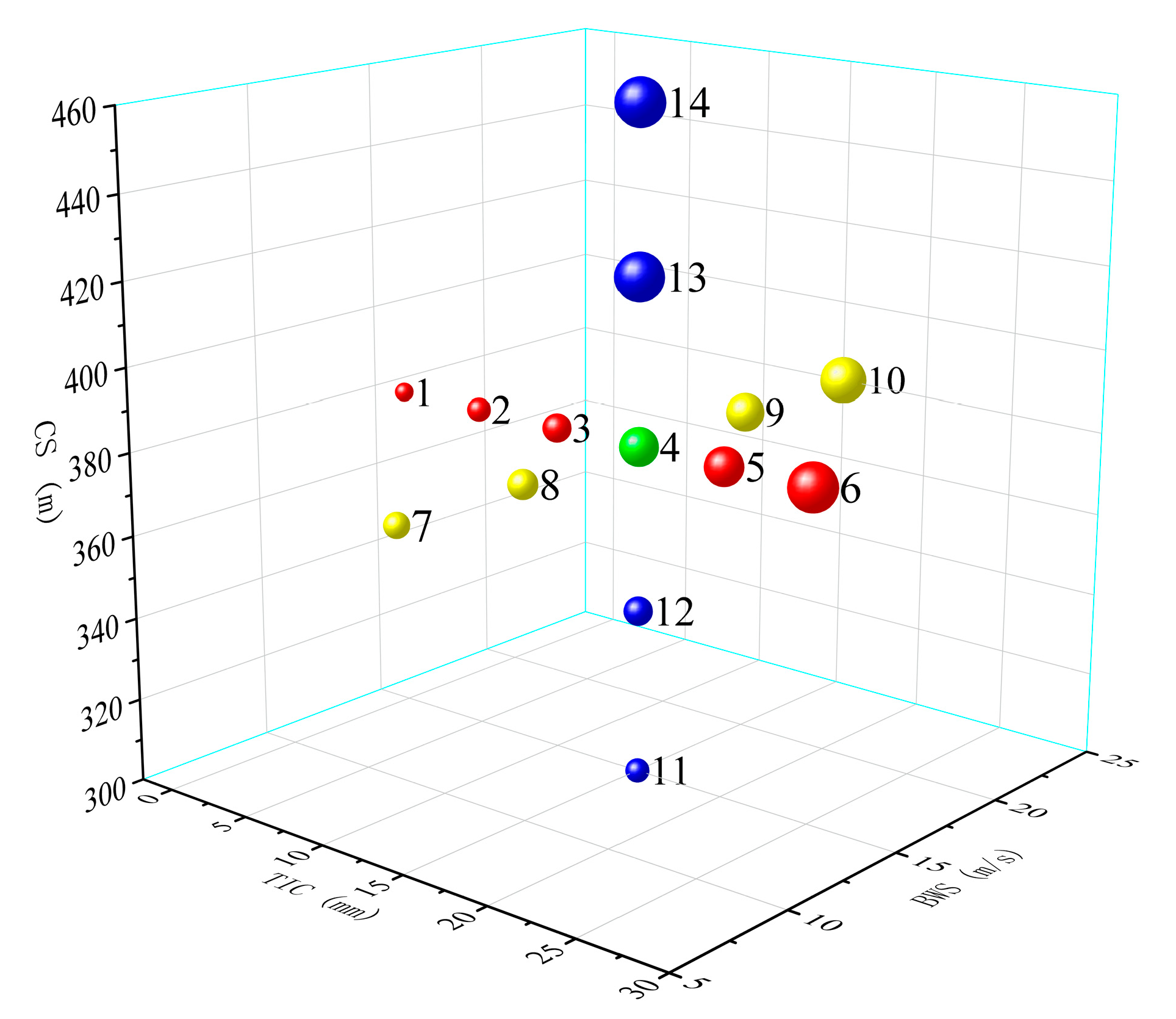

Through the previous analyses, it can be found that, under different working conditions, there is a strong correlation between conductor displacement and crossarm strain in a transmission tower–line system with external loads. The correlation coefficients between the crossarm strain and conductor displacement under various working conditions are shown in

Table 12. Based on this, it can also be concluded that a functional relationship exists between these two variables.

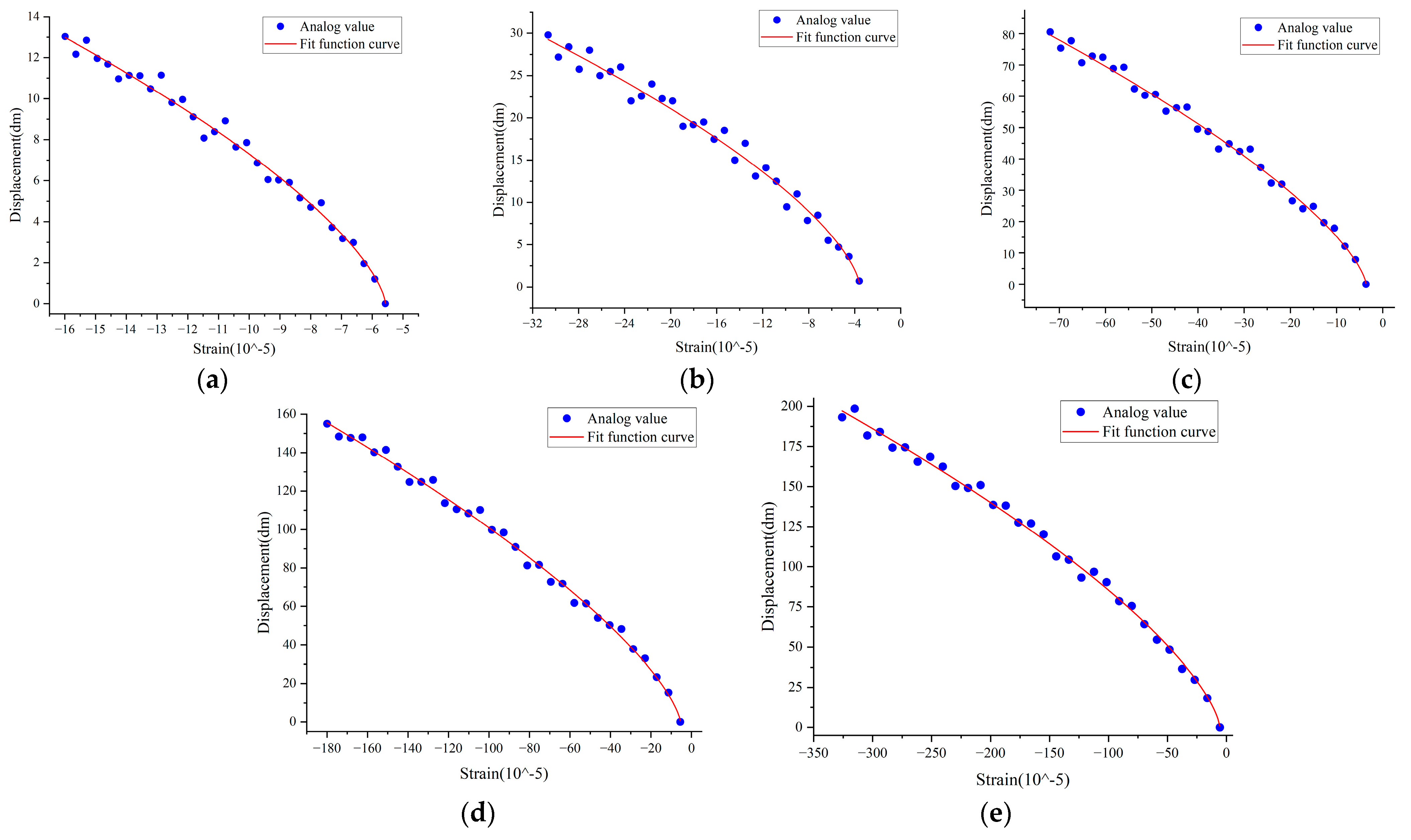

When constructing the functional relationship, the crossarm strain is selected as the independent variable, and the resultant displacement at the midpoint of the conductor is chosen as the dependent variable. First, a dataset of crossarm strain-conductor midpoint displacement is established. Based on the strain amplitude, the data is uniformly divided into 30 numerical intervals. Since this study focuses on time-domain analysis of crossarm strain and conductor displacement, each crossarm strain value has a corresponding conductor midpoint displacement value at the same moment. Therefore, the median of the strain values in each interval and the average of the corresponding conductor midpoint displacements at those moments are calculated to establish strain-displacement ordinal pairs. These ordinal pairs are then plotted as scatter points. Finally, function relationships are fitted for the displacement-strain scatter plots of each working condition, thereby establishing the functional relationships between conductor displacement and crossarm strain under various working conditions. The fitted functional relationships between conductor resultant displacement and crossarm strain under each working condition are shown in

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16.

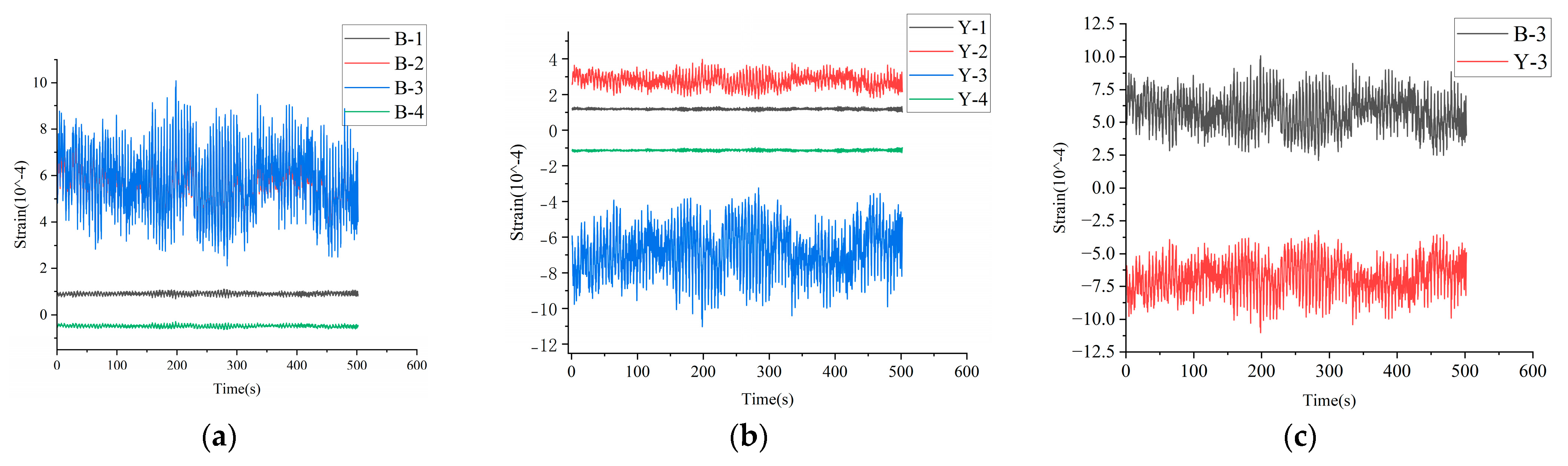

In

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16, the functional relationships between the crossarm strain and midpoint displacement of the conductor under three types of operating conditions (i.e., based on different ice thicknesses, wind speeds, and conductor spans) are presented. In these figures, blue dots represent simulated values, with the horizontal coordinate indicating the median value of each strain interval, and the vertical coordinate representing the average midpoint displacement of the conductor at the corresponding crossarm strain interval. The numerous simulated value points form a scatter plot, and the red curve is the fitting function generated based on this.

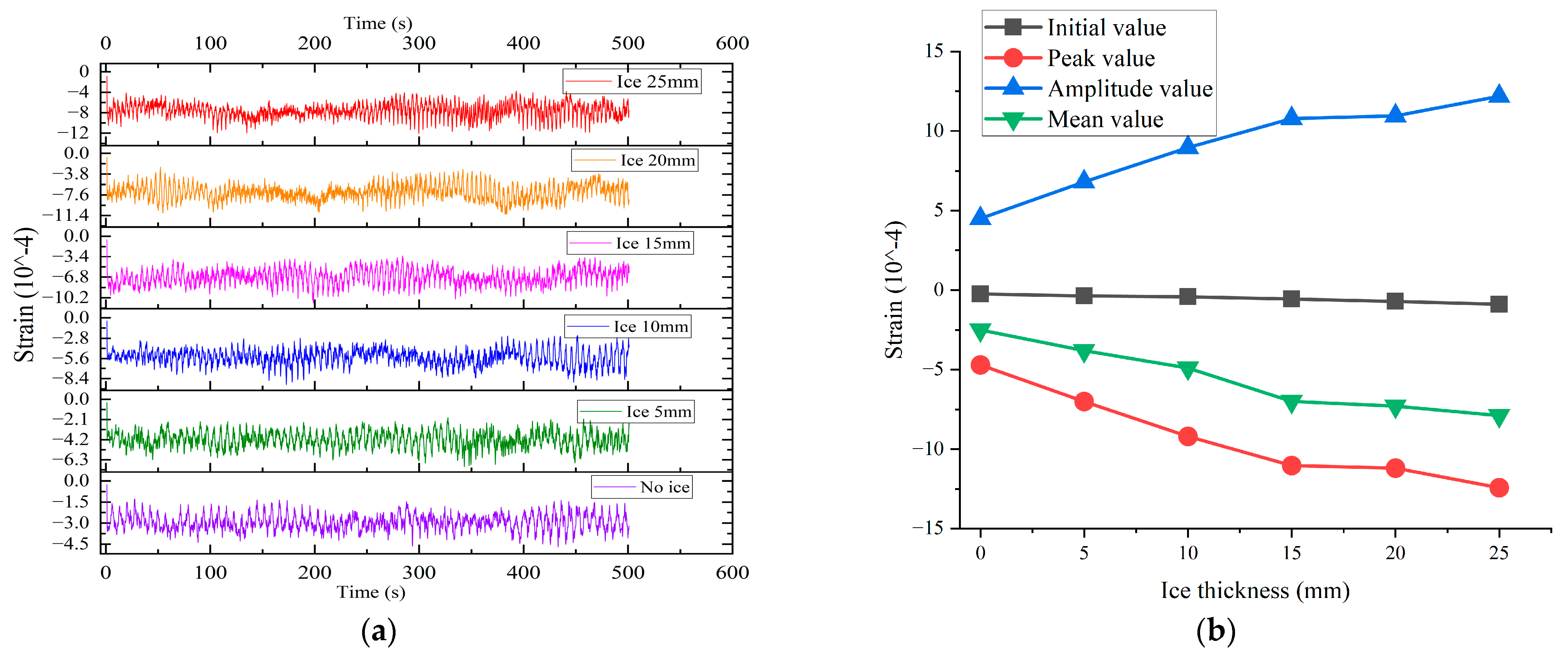

- (1)

The first type of working conditions

In the first type of operating conditions, the span of the conductor and the wind speed of the tower–line system remain unchanged, while the ice thickness gradually increases. When the ice thickness is small, the displacement of the conductor under wind load based on the same wind speed increases significantly. In this scenario, the gravitational effect of the ice directly increases the vertical load (dead load) of the conductor, leading to an increase in sag. The ice thickness and load increase linearly. However, within the elastic range of the material, the increase in sag is nonlinear, usually accelerating with the increase in load. When the ice thickness exceeds a certain level (15 mm in the simulation results of this study), inertial effects become dominant, and the mass of the conductor system increases sharply. Under the same external force (wind load), objects with greater mass exhibit smaller acceleration, and the huge inertial force suppresses the movement of the conductor.

According to

Figure 14,

Figure 15 and

Figure 16, the basic formula for the functional relationship between conductor displacement and crossarm strain is as follows:

In the above formula, x represents the crossarm strain, with units of 10−5; y denotes the resultant displacement at the midpoint of the conductors, with units of dm; A is the comprehensive coefficient of the fitting function; b signifies the initial strain of the crossarm; and p is the fitting parameter, set as 0.7.

Under the first working condition, since the magnitude of the wind speed and the horizontal span of the conductors are specified, only the influence of the ice’s thickness on the crossarm strain is analyzed. The comprehensive coefficient

A is solely related to the thickness of the ice. The impact function is defined as

, where

t represents the ice thickness in mm. Based on the fitting function relationships for the first type of working conditions (described earlier),

can be expressed as follows:

The thickness of the ice coating on the conductors directly affects the initial strain of the crossarm, which is set as

:From the above fitting function, the final expression of the fitting function based on the first type of working conditions can be obtained as follows:

- (2)

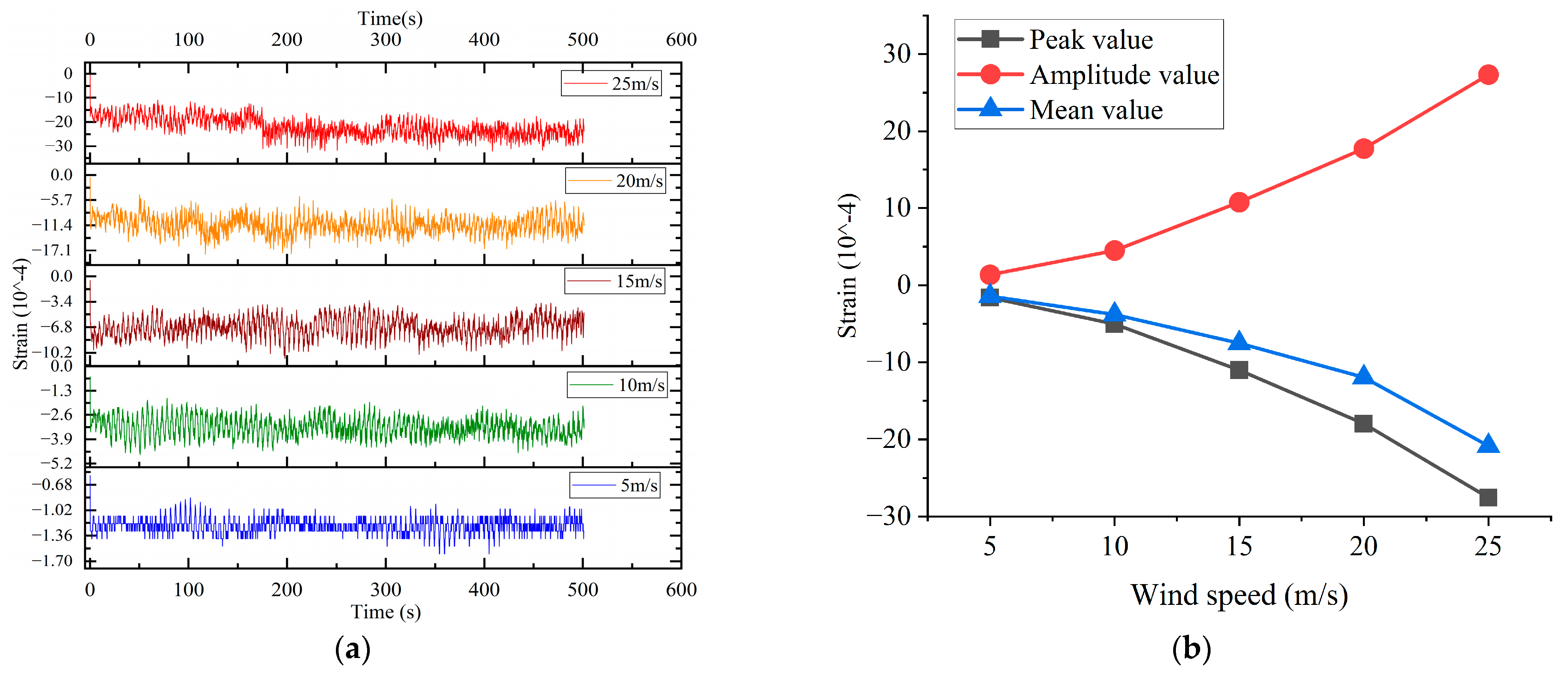

The second type of working condition

Under the second type of operating conditions, the ice thickness on the conductor and the conductor’s own span remain unchanged, while the simulated wind speed increases uniformly. When the wind speed is in a relatively low range, the displacement response of the conductor begins to appear and increases relatively gently. This is because at low wind speeds, the energy that is provided by the wind load is limited, mainly exciting low-order motion of the line, and the displacement response is primarily quasi-static. When the wind speed reaches a higher level, the displacement response increases sharply or even reaches a peak. This is because when the wind speed reaches a certain critical value, the excitation frequency of the wind load approaches a certain natural frequency of the tower–conductor system (especially the fundamental frequency), causing resonance to occur and leading to the response being sharply amplified.

Under this working condition, the comprehensive coefficient

A takes the influence of the basic wind speed into account, and the basic fitting functions for conductor displacement and crossarm strain are as follows:

among which

In the above formula, varies, since when the wind speed exceeds 20 m/s, the coefficients in the function between the crossarm strain and conductor displacement under this type of operating condition are lower than those under the 5~20 m/s operating condition, which leads to a decrease in the overall fitting accuracy. To more accurately reflect the change in coefficients, a piecewise function is set for this expression.

- (3)

The third type of working conditions

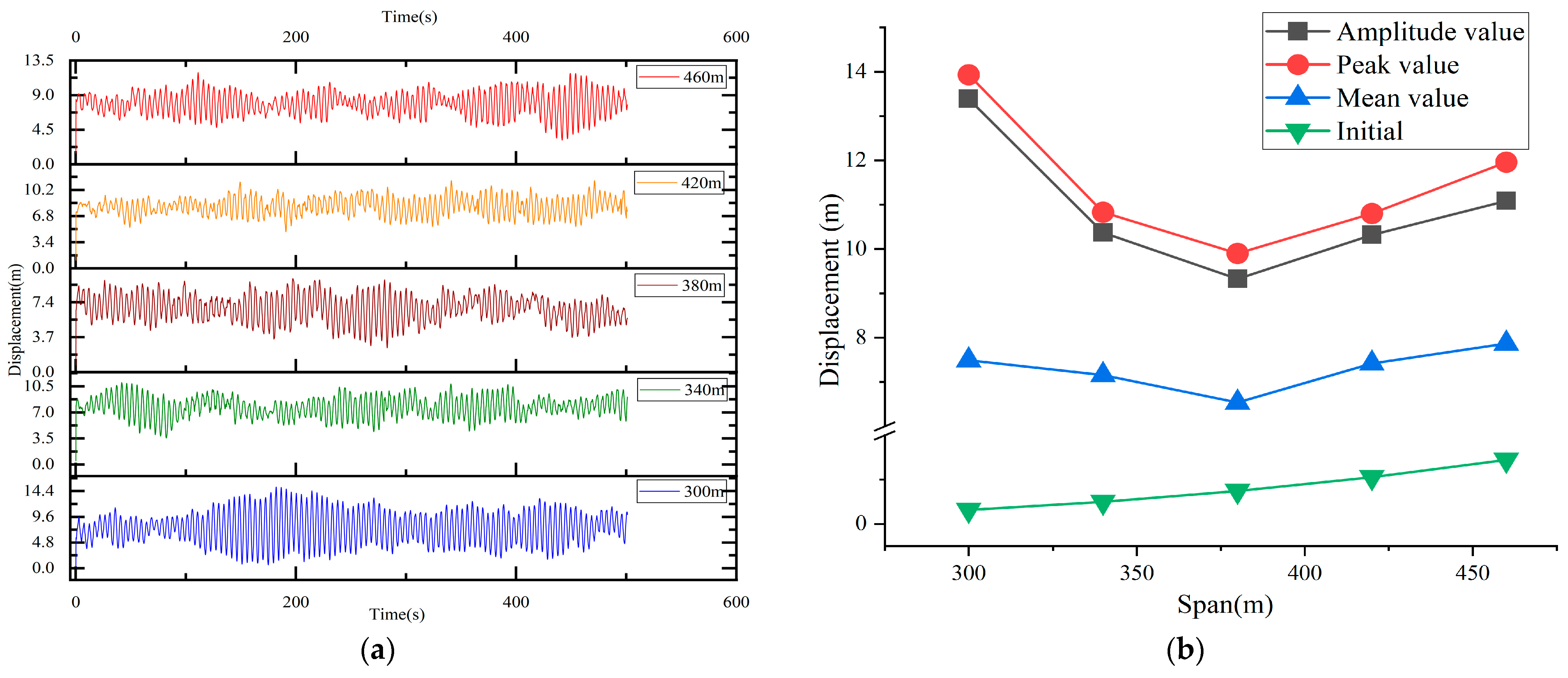

Under the third type of operating conditions, the comprehensive coefficient takes the influence of the conductor span into account. For conductors with the same sag, the smaller the conductor span is, the more relaxed the stress of the conductor is, and under the same wind load, the displacement response of the conductor is larger; in contrast, when the conductor span is too large, the tension of the conductor is greater, leading to an increase in the elongation of the conductor. In addition, an increase in conductor span has a cumulative effect on the displacement value. At the same time, due to the increase in span causing an increase in the gravitational load of the conductor, the initial strain value of the crossarm changes. Therefore, in the initial strain term, the influence of the span is added, and the coefficient of the span’s impact on the initial strain value is set as .

The basic expression of the fitting function for conductor displacement and crossarm strain under the third type of operating conditions is as follows:

where

A = . Based on the fitted function expressions under various working conditions (shown in

Figure 16), combined with the already known

under the first two types of working conditions, the expression for

is as follows:

Regarding the influence of the conductor span on the initial strain value of the crossarms, the coefficient setting for this type of working conditions is

. The fitting function between the initial strain value and the span is obtained as follows:

Based on the integration of fitting functions between the conductor displacement and crossarm strain under various working conditions, the following fitting relationship was obtained for the 2G-SZC2 tangent tower–line system with ice coating thicknesses of 0–25 mm: basic wind speed of 5–25 m/s and span of 300–460 m. Under combined ice–wind loading conditions, the fitting function between the mid-span conductor displacement and crossarm strain is established as follows:

Here, is the influence coefficient based on the ice thickness; is the influence coefficient based on the wind speed; is the influence coefficient based on different spans; is the functional relationship between the ice thickness and initial strain of the crossarm; is the functional relationship between the conductor span and initial strain of the crossarm; y is the conductor displacement value; x is the crossarm strain value; t is the average thickness of the ice on the tower and conductor, in mm, with the ice thickness range in this study being 0~25 mm; v is the basic wind speed of the pulsating wind, in m/s, with the basic wind speed range in this study being 5~25 m/s; and L is the span of the conductor, in m, with the conductor span range in this study being 300~460 m.

4.2. Analysis of Galloping of Iced Conductors Under Reference Working Conditions

By applying the aerodynamic load on the conductors, we can simulate and analyze the ice-induced galloping of the transmission conductors. Based on the operating conditions set in this paper, the coupled effect of the aerodynamic lift and aerodynamic drag of the conductor determines the vibration mode of the conductor. The time history data for the midpoint displacement of the conductors are shown in

Figure 17. Under the action of a constant external wind load, the galloping amplitude of iced transmission conductors develops gradually and finally reaches a stable state after more than 350 s. During the process of iced conductor galloping, the development trend and amplitude of the mid-span displacement of the conductor are basically consistent with those described in references [

27,

31]. Therefore, the numerical simulation results regarding conductor galloping are relatively accurate.

The time history data for the strain at the end of the crossarm under conductor galloping with ice coating are shown in

Figure 18. The time history data for the strain of the crossarm are similar to those for the displacement at the midpoint of the conductors. The crossarm strain undergoes a gradual development process and ultimately reaches a stable state after 350 s.

During the ice-induced galloping of transmission conductors, the conductors undergo large-amplitude swinging on both sides in the along-wind direction, resulting in alternating positive and negative phenomena of the crossarm strain. In the previous analysis of the wind-induced response of the transmission tower–conductor system, the conductor always undergoes displacement on one side in the along-wind direction, causing the crossarm strain to remain negative. Therefore, the negative strain interval is selected for verification under conditions of conductor galloping. Strain–displacement data points are constructed, plotted as a scatter diagram, and compared with the calculation results of Formula (21), as shown in

Figure 19.

By comparing the strain–displacement simulation values with the curve calculated using Equation (22), it can be observed that the strain–displacement data points based on conductor galloping fluctuate around the calculated values of Equation (22). Under the four working conditions—A, B, C, and D—the maximum errors are 4.75%, 6.43%, 10.58%, and 5.62%, respectively, with the overall error being controlled within 11%. This indicates that the fitting formula exhibits good applicability to the galloping of ice-covered transmission conductors.