Application of IoT in Monitoring Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Anaerobic Reactors

Abstract

1. Introduction

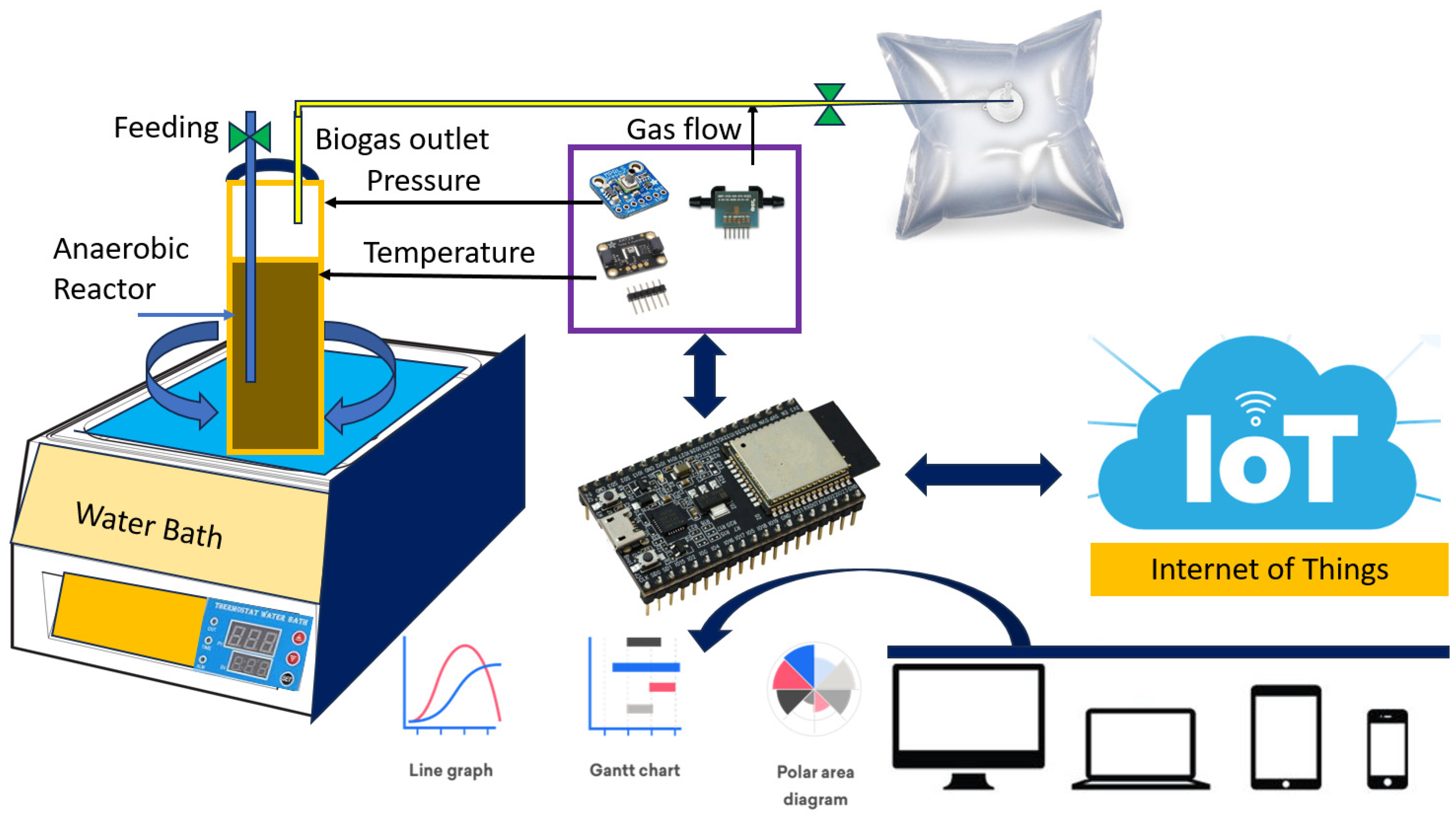

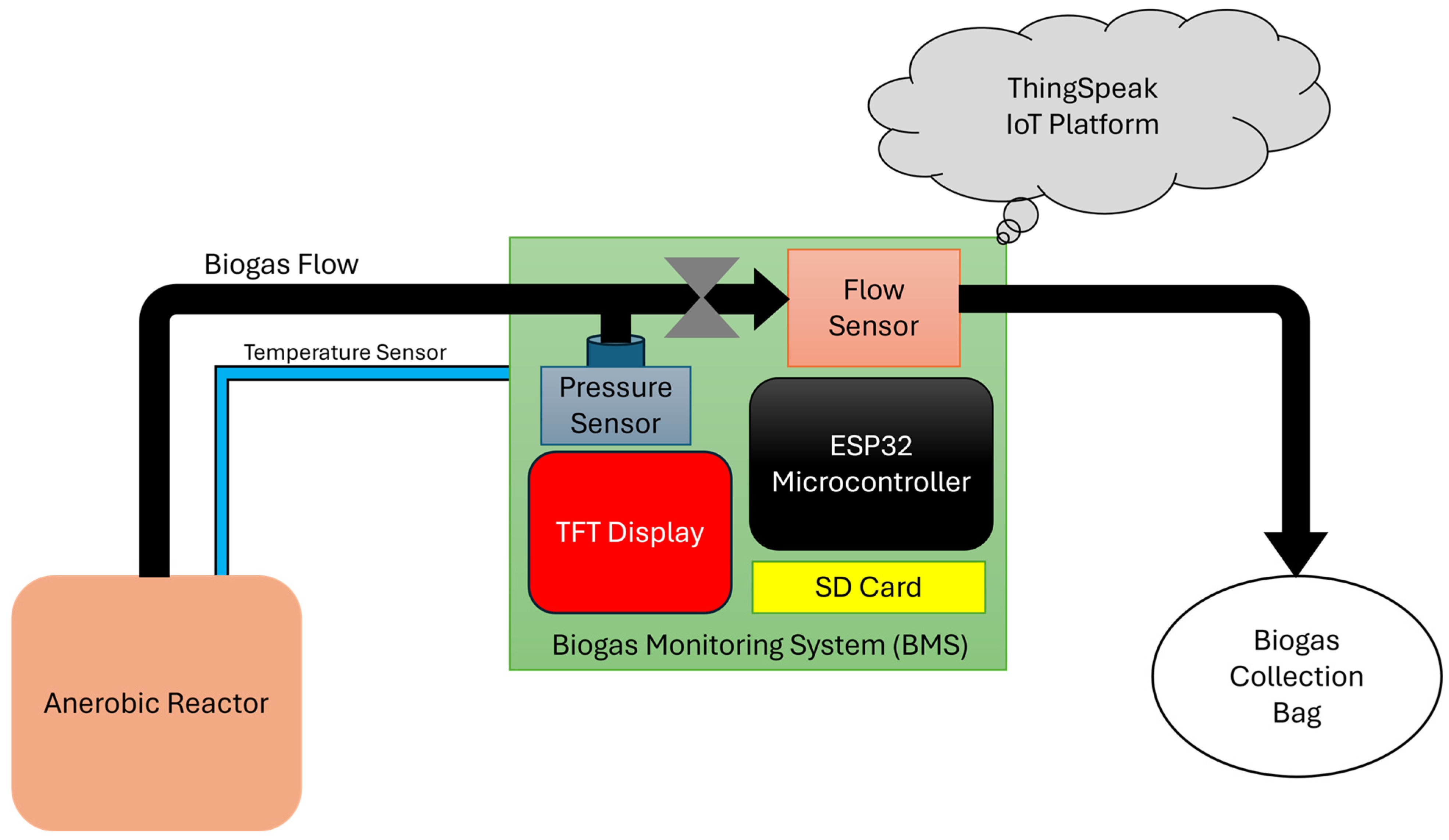

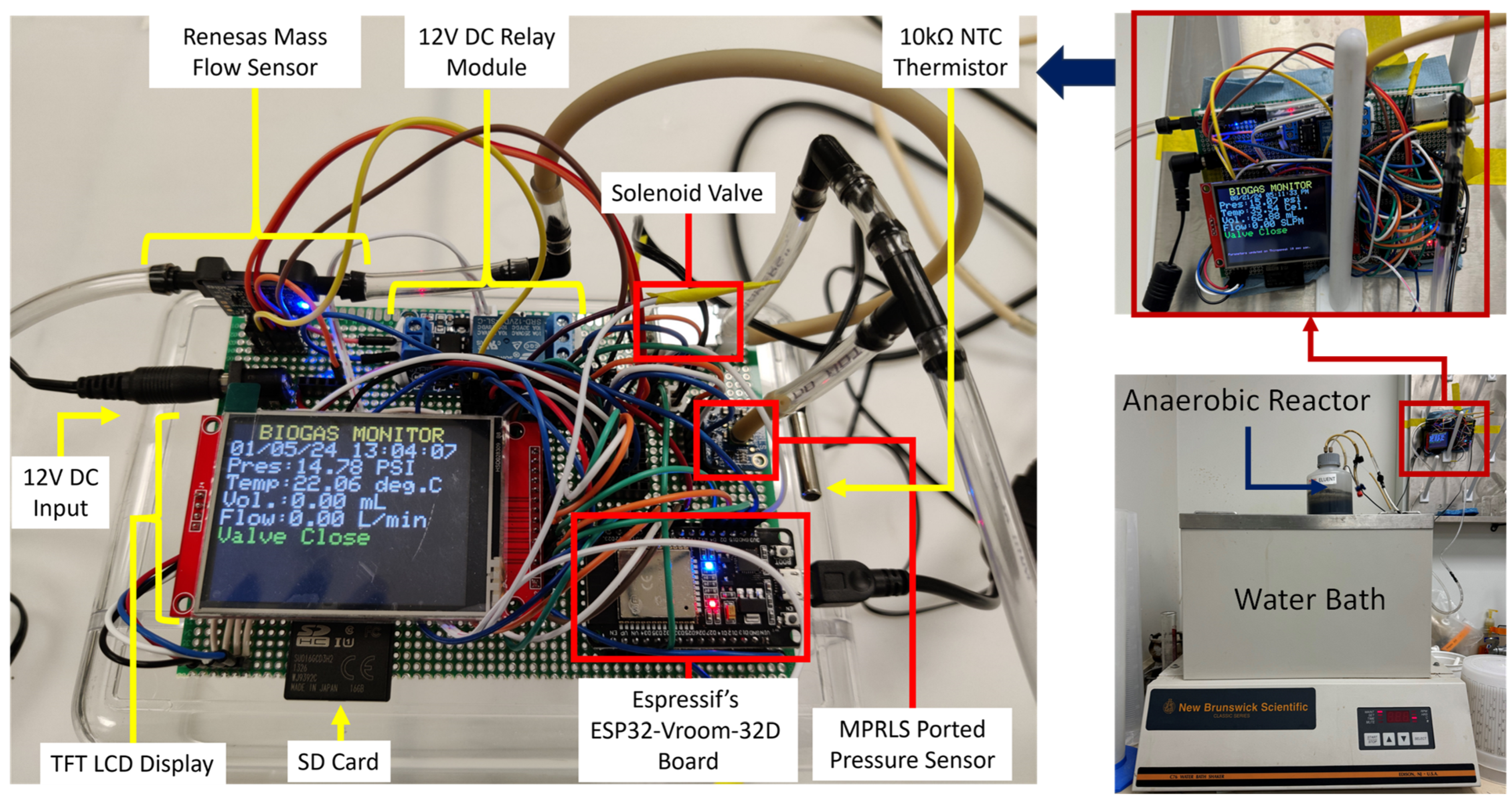

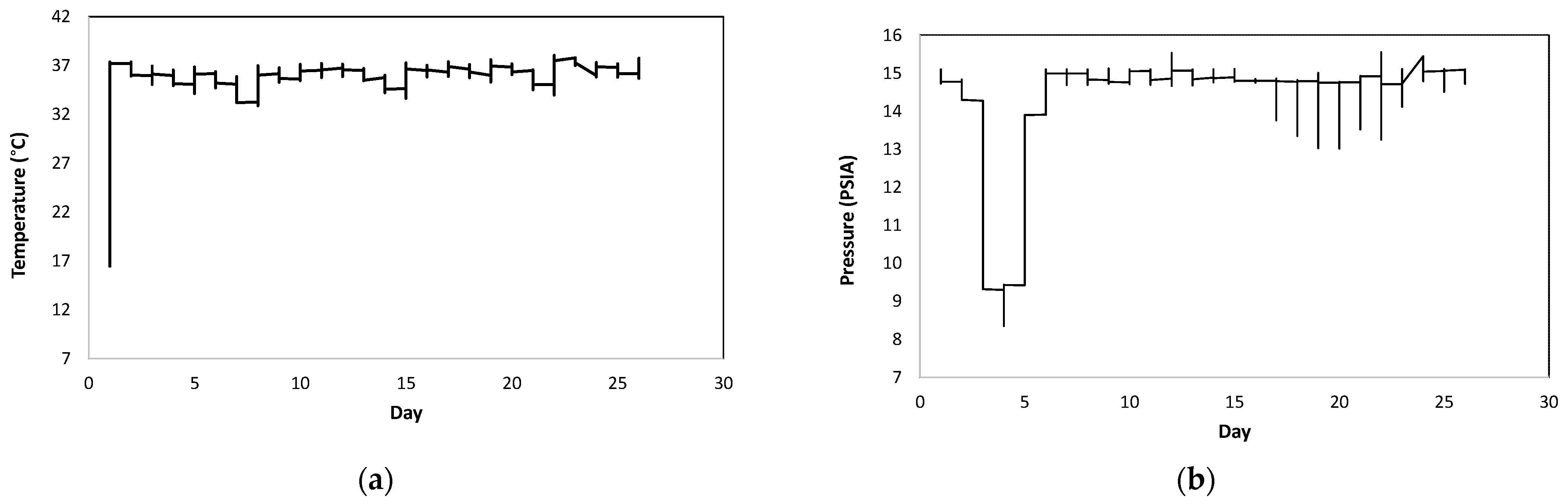

2. Materials and Methods

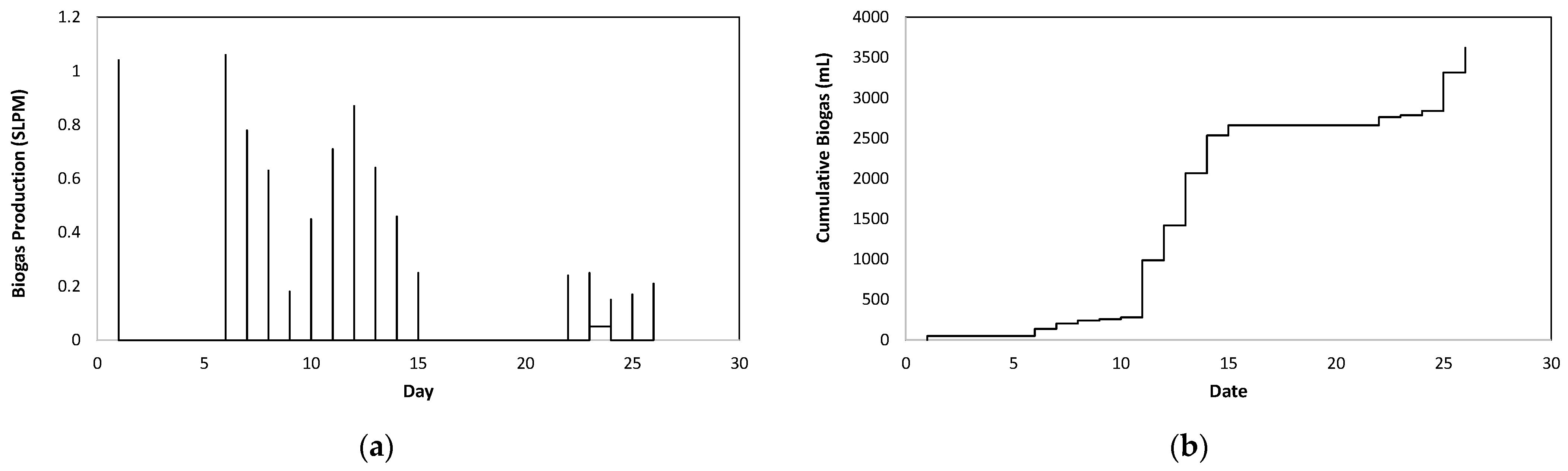

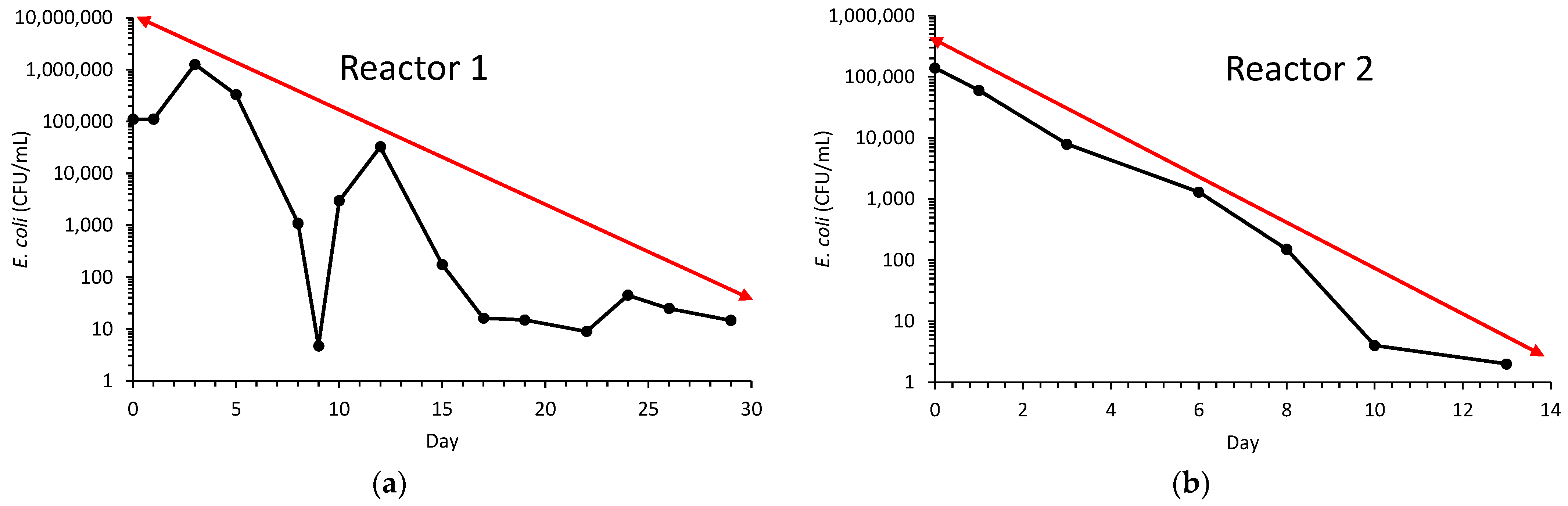

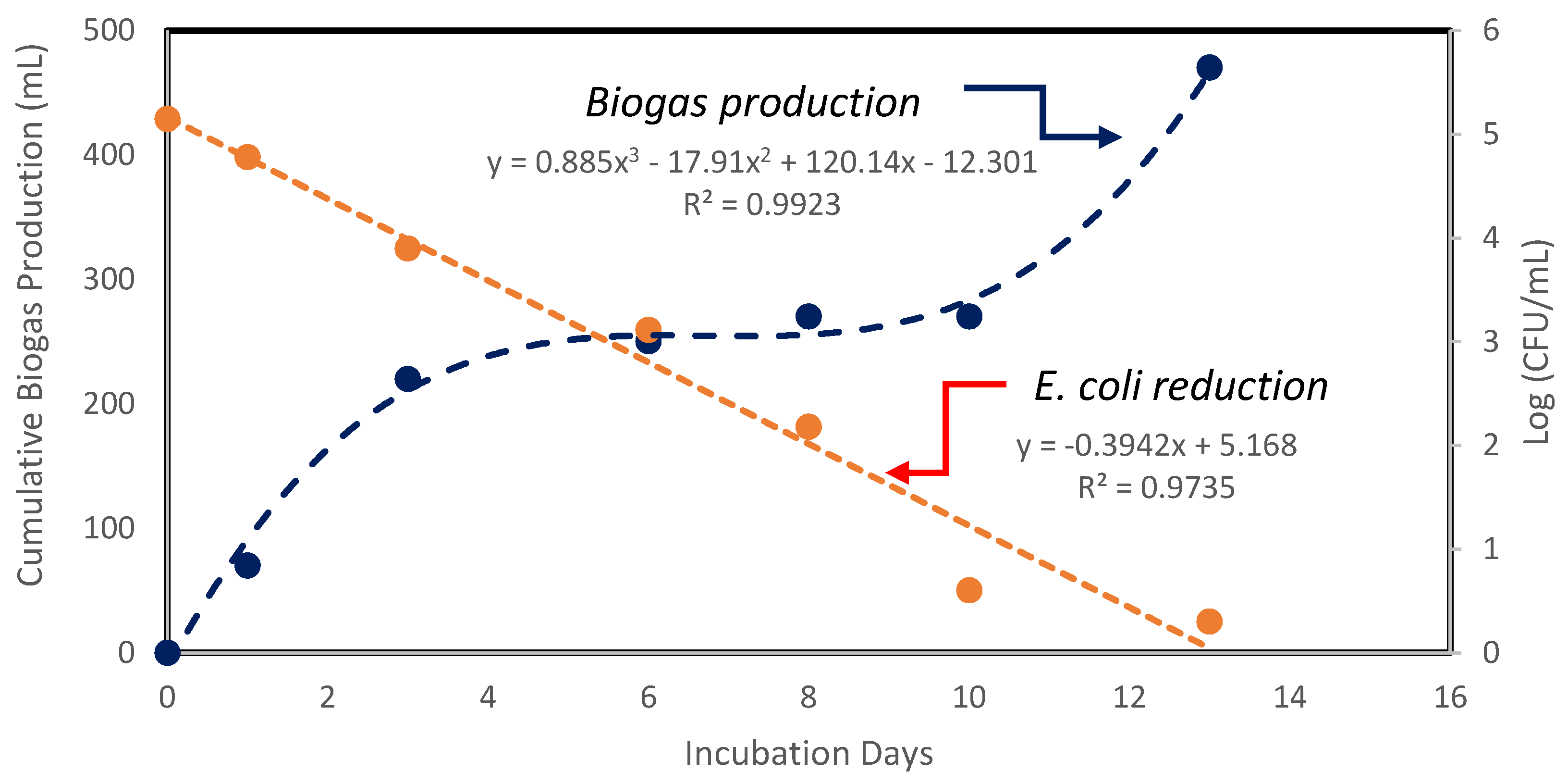

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bellarby, J.; Tirado, R.; Leip, A.; Weiss, F.; Lesschen, J.P.; Smith, P. Livestock greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation potential in Europe. Glob. Change Biol. 2013, 19, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massé, D.I.; Talbot, G.; Gilbert, Y. On farm biogas production: A method to reduce GHG emissions and develop more sustainable livestock operations. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 2011, 166, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Deng, S.; Dunn, J.; Smith, P.; Sun, W. Animal waste use and implications to agricultural greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 064079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Kass, P.; Soupir, M.; Biswas, S.; Singh, V. Contamination of water resources by pathogenic bacteria. AMB Express 2014, 4, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, R.; Gordon, R.; Joy, D.; Lee, H. Assessing microbial pollution of rural surface waters: A review of current watershed scale modeling approaches. Agric. Water Manag. 2004, 70, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallin, M.A.; Cahoon, L.B. Industrialized animal production—A major source of nutrient and microbial pollution to aquatic ecosystems. Popul. Environ. 2003, 24, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.K.; Ndegwa, P.M.; Soupir, M.L.; Alldredge, J.R.; Pitts, M.J. Efficacies of inocula on the startup of anaerobic reactors treating dairy manure under stirred and unstirred conditions. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 2705–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakar, S.; Yetilmezsoy, K.; Kocak, E. Anaerobic digestion technology in poultry and livestock waste treatment—A literature review. Waste Manag. Res. 2009, 27, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, I.M.; Mohd Ghazi, T.I.; Omar, R. Anaerobic digestion technology in livestock manure treatment for biogas production: A review. Eng. Life Sci. 2012, 12, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wei, L.; Duan, Q.; Hu, G.; Zhang, G. Semi-continuous anaerobic co-digestion of dairy manure with three crop residues for biogas production. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 156, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amon, T.; Amon, B.; Kryvoruchko, V.; Zollitsch, W.; Mayer, K.; Gruber, L. Biogas production from maize and dairy cattle manure—Influence of biomass composition on the methane yield. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2007, 118, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Pandey, A.; Yan, L.; Wang, D.; Pandey, V.; Meikap, B.C.; Huo, J.; Zhang, R.; Pandey, P.K. Dairy waste and potential of small-scale biogas digester for rural energy in India. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 10671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Shahazi, R.; Nova, S.N.B.; Uddin, M.R.; Hossain, M.S.; Yousuf, A. Biogas production from anaerobic co-digestion using kitchen waste and poultry manure as substrate—Part 1: Substrate ratio and effect of temperature. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2023, 13, 6635–6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilgert, J.E.; Herrmann, C.; Petersen, S.O.; Dragoni, F.; Amon, T.; Belik, V.; Ammon, C.; Amon, B. Assessment of the biochemical methane potential of in-house and outdoor stored pig and dairy cow manure by evaluating chemical composition and storage conditions. Waste Manag. 2023, 168, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mashad, H.M.; Zhang, R. Biogas production from co-digestion of dairy manure and food waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 4021–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adekunle, K.F.; Okolie, J.A. A review of biochemical process of anaerobic digestion. Adv. Biosci. Biotechnol. 2015, 6, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlostathis, S.; Giraldo-Gomez, E. Kinetics of anaerobic treatment: A critical review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1991, 21, 411–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dev, S.; Saha, S.; Kurade, M.B.; Salama, E.-S.; El-Dalatony, M.M.; Ha, G.-S.; Chang, S.W.; Jeon, B.-H. Perspective on anaerobic digestion for biomethanation in cold environments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 103, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meegoda, J.N.; Li, B.; Patel, K.; Wang, L.B. A review of the processes, parameters, and optimization of anaerobic digestion. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, K.; Jang, A.; Yim, S.; Kim, I.S. The effects of digestion temperature and temperature shock on the biogas yields from the mesophilic anaerobic digestion of swine manure. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rico, C.; Rico, J.L.; Tejero, I.; Muñoz, N.; Gómez, B. Anaerobic digestion of the liquid fraction of dairy manure in pilot plant for biogas production: Residual methane yield of digestate. Waste Manag. 2011, 31, 2167–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, L.; Bartha, I. High solids anaerobic fermentation for biogas and compost production. Biomass 1988, 16, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhorhoro, E.K.; Ebunilo, P.O.; Sadjere, G.E. Experimental determination of effect of total solid (TS) and volatile solid (VS) on biogas yield. Am. J. Mod. Energy 2017, 3, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeng, D.; Sutaryo, S.; Purnomoadi, A.; Susanto, S.; Purbowati, E.; Adiwinarti, R.; Purwasih, R.; Widiharih, T. Optimization of methane production from dairy cow manure and germinated papaya seeds using response surface methodology. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 10, 100927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Induchoodan, T.; Haq, I.; Kalamdhad, A.S. Factors affecting anaerobic digestion for biogas production: A review. Adv. Org. Waste Manag. 2022, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobre, P.; Nicolae, F.; Matei, F. Main factors affecting biogas production-an overview. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2014, 19, 9283–9296. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, I.A.; Andrade, L.R.; Bharagava, R.N.; Nadda, A.K.; Bilal, M.; Figueiredo, R.T.; Ferreira, L.F. An overview of process monitoring for anaerobic digestion. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 207, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsapekos, P.; Khoshnevisan, B.; Zhu, X.; Treu, L.; Alfaro, N.; Kougias, P.G.; Angelidaki, I. Lab-and pilot-scale anaerobic digestion of municipal bio-waste and potential of digestate for biogas upgrading sustained by microbial analysis. Renew. Energy 2022, 201, 344–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Raw Manure Under the FSMA Final Rule on Produce Safety; U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020.

- Luna, S. Outbreak of E. coli O157: H7 infections associated with exposure to animal manure in a rural community—Arizona and Utah, June–July 2017. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2018, 67, 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Z.; Balta, I.; Black, L.; Naughton, P.J.; Dooley, J.S.; Corcionivoschi, N. The fate of foodborne pathogens in manure treated soil. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 781357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegbeleye, O.O.; Sant’Ana, A.S. Manure-borne pathogens as an important source of water contamination: An update on the dynamics of pathogen survival/transport as well as practical risk mitigation strategies. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2020, 227, 113524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, S.P.; Jayarao, B.M.; Almeida, R.A. Foodborne pathogens in milk and the dairy farm environment: Food safety and public health implications. Foodbourne Pathog. Dis. 2005, 2, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzhauer, M.; Wennink, G.J. Zoonotic risks of pathogens from dairy cattle and their milk-borne transmission. J. Dairy Res. 2023, 90, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leach, K.A.; Archer, S.C.; Breen, J.E.; Green, M.J.; Ohnstad, I.C.; Tuer, S.; Bradley, A.J. Recycling manure as cow bedding: Potential benefits and risks for UK dairy farms. Vet. J. 2015, 206, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, F.; Chambers, B.; Moore, A.; Nicholson, R.; Hickman, G. Assessing and managing the risks of pathogen transfer from livestock manures into the food chain. Water Environ. J. 2004, 18, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaimat, A.N.; Holley, R.A. Factors influencing the microbial safety of fresh produce: A review. Food Microbiol. 2012, 32, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandrell, R.E. Enteric Human Pathogens Associated with Fresh Produce: Sources, Transport, and Ecology. In Microbial Safety of Fresh Produce; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, A.; Momeni, O.; Pandey, P. Design and Implementation of IoT-Enabled Device for Real-Time Monitoring of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, and Pressure in Anaerobic Reactors. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 133848–133862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capri, M.G.; Marais, G.v.R. pH adjustment in anaerobic digestion. Water Res. 1975, 9, 307–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Qiao, W.; Wang, Y.; Zou, T.; Lin, M.; Dong, R. Balancing acidogenesis and methanogenesis metabolism in thermophilic anaerobic digestion of food waste under a high loading rate. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 824, 153867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Pandey, P.K.; Farver, T.B. Assessing the impacts of temperature and storage on Escherichia coli, Salmonella, and L. monocytogenes decay in dairy manure. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2016, 39, 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.K.; Soupir, M.L. Escherichia coli inactivation kinetics in anaerobic digestion of dairy manure under moderate, mesophilic and thermophilic temperatures. AMB Express 2011, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhou, B.; Yang, L.; Zhuang, J.; Chen, X. Assessing the risk of E. coli contamination from manure application in Chinese farmland by integrating machine learning and Phydrus. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 356, 124345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter Taylor, K.S.; Kauffman, M.; Mammel Mark, K.; Lacher David, W.; Rajashekara, G.; Leonard Susan, R. Long-term impacts of untreated dairy manure on the microbiome and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli persistence in agricultural soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e00447-25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Adhikari, D.; Su, X.; Palmieri, F.; Wu, C.; Choi, C. Integration of data science with the intelligent IoT (IIoT): Current challenges and future perspectives. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2025, 11, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wan, Y.; Wu, Z.; Fang, Z.; Li, Q. A survey on privacy and security issues in IoT-based environments: Technologies, protection measures and future directions. Comput. Secur. 2025, 148, 104097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Navimipour, N.J. A comprehensive and systematic review of the IoT-based medical management systems: Applications, techniques, trends and open issues. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 82, 103914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakili, A.; Bakkali, S. Internet of Things in healthcare: An adaptive ethical framework for IoT in digital health. Clin. eHealth 2024, 7, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullo, S.L.; Sinha, G.R. Advances in Smart Environment Monitoring Systems Using IoT and Sensors. Sensors 2020, 20, 3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Singh, K.J.; Kapoor, D.S.; Thakur, K.; Mahajan, S. The Role of IoT in Environmental Sustainability: Advancements and Applications for Smart Cities. In Mobile Crowdsensing and Remote Sensing in Smart Cities; Kerrache, C.A., Sahraoui, Y., Calafate, C.T., Vegni, A.M., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiki, S.Y.A.; Uddin, M.N.; Mofijur, M.; Fattah, I.M.R.; Ong, H.C.; Lam, S.S.; Kumar, P.S.; Ahmed, S.F. Theoretical calculation of biogas production and greenhouse gas emission reduction potential of livestock, poultry and slaughterhouse waste in Bangladesh. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Deng, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F. Livestock greenhouse gas emission and mitigation potential in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hörtenhuber, S.J.; Seiringer, M.; Theurl, M.C.; Größbacher, V.; Piringer, G.; Kral, I.; Zollitsch, W.J. Implementing an appropriate metric for the assessment of greenhouse gas emissions from livestock production: A national case study. Animal 2022, 16, 100638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, D.; Ravikumar, A.; Tullos, E. Scientific Challenges of Monitoring, Measuring, Reporting, and Verifying Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Natural Gas Systems. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2024, 1, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalehe Kankanamge, E.; Ramilan, T.; Tozer, P.R.; de Klein, C.; Romera, A.; Pieralli, S. Greenhouse gas mitigation in pasture-based dairy production systems in New Zealand: A review of mitigation options and their interactions. Clim. Smart Agric. 2025, 2, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nleya, Y.; Young, B.; Nooraee, E.; Baroutian, S. Anaerobic digestion of dairy cow and goat manure: Comparative assessment of biodegradability and greenhouse gas mitigation. Fuel 2025, 381, 133458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Reactor 1 | Reactor 2 | Average [Reactors 1 and 2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli (CFU/mL) | Average | 123,125 | 29,908 | 76,517 |

| Range | 1,259,991 | 139,998 | 699,995 | |

| Std. Dev. | 326,712 | 53,233 | 189,973 | |

| pH | Average | 6.97 | 6.97 | 6.97 |

| Range | 0.40 | 0.80 | 0.60 | |

| Std. Dev. | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.29 | |

| Sodium (ppm) | Average | 30.24 | 301.43 | 165.84 |

| Range | 30.24 | 80.00 | 55.12 | |

| Std. Dev. | 30.24 | 25.45 | 27.85 | |

| Potassium (ppm) | Average | 368.00 | 417.14 | 392.57 |

| Range | 190.00 | 150.00 | 170.00 | |

| Std. Dev. | 53.88 | 58.23 | 56.06 | |

| Calcium (ppm) | Average | 115.87 | 131.43 | 123.65 |

| Range | 78.00 | 60.00 | 69.00 | |

| Std. Dev. | 24.20 | 19.52 | 21.86 | |

| Salts (%) | Average | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Range | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| Std. Dev. | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | |

| E.C. (mS/cm) | Average | 5.71 | 5.96 | 5.84 |

| Range | 1.40 | 2.85 | 2.13 | |

| Std. Dev. | 0.73 | 1.15 | 0.94 |

| Changes in Startup Phase | Reactor 1 | Reactor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Total biogas production (mL) | 1260 | 470 |

| Initial total solid (%) | 2.31 | 2.63 |

| Total solid reduction (%) | 0.37 | 0.22 |

| Initial E. coli (log) | 5.04 | 5.14 |

| E. coli reduction (log) | 1.63 | 4.84 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, A.; Pandey, A.; Pandey, P. Application of IoT in Monitoring Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Anaerobic Reactors. Energies 2025, 18, 6191. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236191

Li A, Pandey A, Pandey P. Application of IoT in Monitoring Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Anaerobic Reactors. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6191. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236191

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Angela, Aditya Pandey, and Pramod Pandey. 2025. "Application of IoT in Monitoring Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Anaerobic Reactors" Energies 18, no. 23: 6191. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236191

APA StyleLi, A., Pandey, A., & Pandey, P. (2025). Application of IoT in Monitoring Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Anaerobic Reactors. Energies, 18(23), 6191. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236191