Abstract

Substations’ auxiliary systems support the station’s operational loads and are crucial for grid security, often requiring backup power to ensure uninterrupted operation. A new alternative for this backup power supply is a microgrid composed of photovoltaic (PV) generation and storage. This paper proposes an electric–hydrogen microgrid as backup power supply for substation auxiliary systems. This microgrid ensures power supply during emergencies, provides clean and stable energy for daily operations, and enhances environmental friendliness and profitability. Firstly, using a 220 kV substation as an example, the construction principles of the proposed backup power microgrid are introduced. Secondly, operation strategies under different scenarios are proposed, considering time-sharing tariffs and different weather conditions. Following this, the capacity configuration optimization model of the electric–hydrogen microgrid is proposed, incorporating critical thresholds for energy reserves to ensure system robustness under fault conditions. Finally, the Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm is used to solve the problem, and a sensitivity analysis is performed on hydrogen market pricing to evaluate its impact on the system’s economic feasibility. The results indicate that the proposed electric–hydrogen microgrid is more economical and provides better fault power supply time than battery-only power supply. With the development of hydrogen energy storage technology, the economy of the proposed microgrid is expected to improve further in the future.

1. Introduction

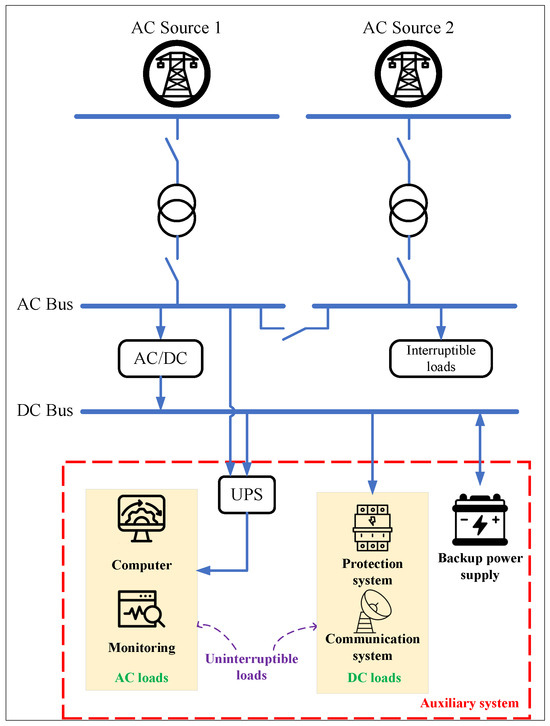

The substation serves as the core of the power grid, ensuring the normal operation of the power transmission [1]. In a substation, there are some critical loads used to support its operation, known as auxiliary systems, consisting of protection systems, communication systems, computers, and monitoring systems [2]. When a fault occurs in the upper power grid, the relay protection and communication systems need to act in time to prevent the fault from spreading, so the auxiliary system of the substation has strict requirements for uninterrupted energy supply [3,4]. Therefore, it is imperative to install backup power systems at substations to mitigate risks such as grid faults or internal station short circuits. The auxiliary system structure of a 220 kV substation is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

220 kV substation with auxiliary system.

At present, backup power for substation auxiliary systems is widely provided by diesel generators and lead–acid batteries [5,6]. However, diesel generators raise environmental concerns, while lead–acid batteries face challenges in terms of energy density, charging rate, and environmental concerns [7]. Lithium batteries are often considered as potential substitutes. Costa et al. [8] demonstrated that integrating both lithium batteries and lead–acid batteries as backup power for the substation auxiliary system is more cost-effective and performs better than lead–acid batteries solely. However, lithium batteries are not suitable for prolonged float charging, which restricts their performance as a long-term backup power source.

Compared with batteries, hydrogen energy storage offers longer lifespan, smaller size and upper long-term storage capabilities. These features can substantially extend the power supply duration and enhance reliability when serving as a backup power source [9]. Moreover, it has been investigated for use as a long-term energy storage solution in microgrids [10,11]. In [12], a comprehensive hydrogen–electric energy system is established to generate electricity, produce hydrogen, and supply hydrogen load, improving the system’s revenue. The application of hydrogen energy storage in substations has already been started. Yang et al. [13] incorporated wind power and hydrogen energy storage into a railway substation to enhance power supply capacity and reduce electricity costs. Obara et al. [14] installed a hydrogen storage device in a substation to supplement the lower feeder power supply. In [15], hydrogen fuel cells were used as backup power for the auxiliary system in substations with a small portion of lead–acid batteries. However, the paper did not analyze where the fuel of hydrogen cells come from, and the extended power supply time and reduced cost of hydrogen fuel cells were not quantified.

Furthermore, besides energy storage, photovoltaic (PV) power generation, as a clean alternative energy source, can also serve as a generation unit for substation auxiliary system [16]. In 1995, a substation in California, USA, added PV power generation to reduce line losses and enhance the reliability of the distribution system [17]. De Araujo Silva Júnior et al. [18] established a substation microgrid comprising a hybrid PV and Li-PbC energy storage system, evaluating its roles in supporting daily operations and emergency response. The study highlights that a PV–storage hybrid microgrid can serve as a novel approach to providing uninterrupted power to substation auxiliary systems. Properly matching the two components enables the system to harness the advantages of both renewable energy generation and energy storage.

Due to the high cost of batteries, a more comprehensive approach is necessary. Reasonable capacity configuration can maximize normal operational benefits for the substation while also meeting demand for backup power during faults and emergencies. Tabares et al. [19] built a micro-grid with PV power and lead–acid batteries to supply auxiliary services during a contingency for a substation. They used Monte Carlo simulation and exhaustive search to determine the required emergency power supply capacity, considering battery costs. Ribic et al. [20] presented a capacity configuration model for lead–acid battery backup power in a substation auxiliary system using the differential evolution method. The model considered building and maintenance costs, temperature retention costs, and system reliability. In [21], a multi-objective optimization model is proposed for a PV–battery system in substation. This model considers investment costs and contingency availability indicators to configure energy storage capacity, which offers valuable insights for configuring emergency power supply in substation auxiliary systems. However, these literatures only utilize energy storage for emergency power supply, failing to fully exploit its potential such as peak shaving and valley filling.

Additionally, the backup power microgrid discussed in the aforementioned article has no operating strategies besides charging when connected to the grid, whereas control strategies are essential for optimizing performance and efficiency. Microgrid scheduling methods are divided into optimization-based methods and rule-based methods. Optimization-based methods aim to minimize system operating costs and power fluctuations over a given period (usually from several hours to several days) to find a global optimal solution [22]. Ji et al. [23] employ non-dominated sorting to study multi-objective optimization strategies for active distribution networks, achieving global optimization of system output, operation times, network loss, and node voltage deviation. Rule-based methods determine microgrid power distribution rules based on human experience and expert knowledge. Yuan et al. [24] propose a rule-based real-time environmental management system for fuel cell/battery hybrid power systems, optimizing power distribution between fuel cells and batteries. Lopez et al. [25] present a rule-based power management system for a hydrogen-supercapacitor hybrid generator, managing various power sources. Optimization-based methods require significant computational power for real-time global optimization, which is challenging due to the limited resources of microcontrollers and the aging equipment in substations. In contrast, rule-based strategies are simple, robust, and have low computational complexity, making them effective for stable and reliable power distribution even with limited resources.

Therefore, this paper proposes a PV-based electric–hydrogen microgrid solution for substations, which not only meets emergency backup supply requirements but also enhances profitability during routine operations. The main contributions of the paper are as follows:

- We propose a dual-purpose electric–hydrogen microgrid solution for substation auxiliary systems, leveraging idle rooftop and ground space for PV and hydrogen equipment. This approach is shown to not only meet critical emergency backup requirements but also enhance daily operational profitability by enabling services such as peak shaving and valley filling.

- We formulate detailed operational strategies for both normal and fault scenarios, addressing a key gap in the literature which often lacks strategies beyond simple grid charging. The normal operation strategy optimizes energy distribution based on time-of-use tariffs and weather conditions, while the fault strategy details the critical coordination of the hybrid storage system. In particular, it uses the lithium battery’s rapid response to bridge the fuel cell’s startup time, ensuring a truly seamless power supply to critical loads.

- We introduce an optimization model that mathematically embeds the fault strategy as a hard constraint. Unlike conventional models that primarily optimize for daily economics, our approach first calculates the non-negotiable backup energy required during faults, defining it as a ’safety-first’ operational boundary. This methodology ensures the system’s robustness is mathematically guaranteed, while the remaining capacity is then optimized for daily profitability.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows: The principle and theoretical analysis are presented in Section 2. The rule-based scheduling strategy for normal and fault conditions are presented in Section 3. The modeling and algorithm for capacity configuration are detailed in Section 4. A case study is provided in Section 5. The conclusions of this work are drawn in Section 6.

2. Principle and Theoretical Analysis

2.1. Auxiliary System Structure of a Conventional Substation

Figure 1 illustrates the main wiring diagram of a 220 kV substation and its auxiliary system. The auxiliary system comprises an uninterruptible power system (UPS), a backup power supply system and uninterruptible loads within the substation [26]. These uninterruptible loads are critical for maintaining substation operation during normal and fault conditions [27], categorized into regular loads and emergency response loads (Table 1).

Table 1.

Uninterruptible loads for an auxiliary system in a 220 kV substation.

- Regular loadsIn normal scenarios, the microgrid supplies power to various components within the auxiliary system. These include protection devices, communication equipment, control devices, fire alarm systems, and other essential operational devices.

- Emergency response loadsDuring fault scenarios, when the substation loses power from the upper grid, additional critical loads are activated. These include emergency lighting, UPS loads, circuit breaker tripping, and switch closing equipment, all requiring uninterrupted power supply.

In normal operation scenarios, the auxiliary system is primarily supplied by the upper power grid, and backup power supply batteries will be charged. When the upper power grid or the station power supply transformer fails, the auxiliary system will be disconnected from the grid to avoid fault expansion. At this time, uninterruptable DC loads and the UPS are supplied by the backup power system [28], while the uninterruptable AC loads are powered by the UPS [29]. Other loads within the station will be disconnected, and power delivery to the lower grid will be stopped.

2.2. Electric–Hydrogen Microgrid Structure for Substation Power System

The unused rooftop space of a substation can be used to install PV system, supplying power to internal auxiliary loads and reducing grid dependency. This decreases line losses and enhances the utilization of the substation’s space. For a 220 kV substation, the rooftop area available for solar panel installation is approximately 600 m2. After accounting for rooftop pathways and gaps between the panels, around 100 solar panels, each measuring 1956 × 992 × 50 mm, can be installed. Each panel has a peak power of 300 W, resulting in a total peak power of 30 kW for the PV system.

High-voltage substations are typically located far from urban areas and are surrounded by open space. By constructing a hydrogen storage system on unused land within the substation or externally, excess electricity generated during peak photovoltaic production periods can be used to produce green hydrogen. While the application of hydrogen energy storage in substations, as proposed here, follows an emerging trend with prior examples [13,14,15], co-locating hydrogen production and storage systems within a high-voltage environment necessitates strict adherence to safety protocols, such as sufficient physical separation and protective barrier walls [30], to mitigate risks. Hydrogen storage offers high energy capacity, while lithium batteries provide rapid power response. Together, their complementary strengths can ensure a stable power supply to the load.

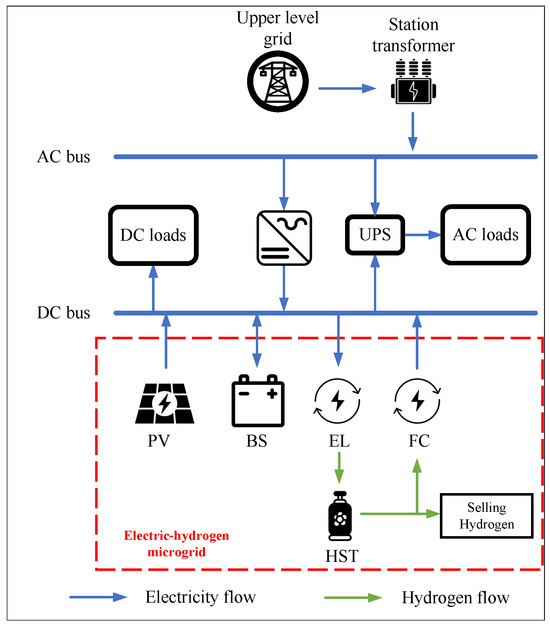

Figure 2 illustrates the structure of the microgrid, which includes a PV system, lithium battery storage (BS), electrolyzer (EL), hydrogen storage tank (HST), and fuel cell (FC). The PV system serves as the primary energy source, supplying electricity to the substation. The battery and hydrogen storage system together form a Hybrid Energy Storage System (HESS). The battery helps reduce system costs during normal grid operation while ensuring uninterrupted power to critical loads during grid failures. Excess PV power or off-peak electricity is used by the electrolyzer to generate hydrogen, which can be stored and sold for profit. The fuel cells remaining inactive in normal scenarios, while provide backup power to critical loads for a long-time during fault scenarios.

Figure 2.

Substation auxiliary system with electric–hydrogen microgrid as backup power.

Compared to traditional lead–acid battery or diesel generator backup systems, it is cleaner and more cost-effective. After a fault, the PV power and remaining electricity of batteries can be used to provide reverse power to the substation, enabling a black start. For some substations, the backup power supply for auxiliary systems needs to utilize external substation feeders. By adding this microgrid, the voltage level of the external backup power can be lowered, thus reducing construction costs.

2.3. Backup Power Microgrid System Model

In this section, the mathematical model of the electric–hydrogen microgrid is provided.

- PV panelThe output power of PV panels depends on solar irradiance and temperature. A standard and computationally efficient empirical model is adopted [31], suitable for this system-level capacity configuration study. The operating temperature is first estimated from the ambient temperature (Equation (1)), which is then used to calculate the final PV power (Equation (2)).where is the PV cell operating temperature, is the ambient temperature, and G is the solar irradiance received by the PV cell. is the maximum power under standard test conditions (irradiance of 1000 W/m2, cell temperature of 25 °C), is the actual irradiance, is the reference irradiance, is the power temperature coefficient, and is the reference temperature.

- BatteryThe state of charge (SOC) of the battery indicates the proportion of the remaining power to the total power. The formulas for calculating battery SOC are as follows [32]:and denote the charge/discharge power of the battery during the time interval , respectively. and denote the charge/discharge efficiency, respectively. is the battery capacity, and is the sampling interval.

- Hydrogen energy storageHydrogen is produced by the electrolyzer, stored in the hydrogen storage tank, and converted into electricity by the fuel cell or sold to other factories. The energy conversion relationships are as follows [33]:and refer to the minimum starting power and the rated power of the electrolyzer, respectively. is the ratio between them, typically ranging from 10% to 20%. The hydrogen substance contents entering and leaving the storage tank are denoted by and , respectively. represents the amount of hydrogen produced per unit of electrical energy. The efficiencies of the electrolyzer and the fuel cell are indicated by and , respectively. The hydrogen production power of the electrolyzer is , and the hydrogen consumption power of the fuel cell is . denotes the ratio of stored hydrogen to the maximum storage capacity of the tank. The efficiencies of hydrogen compression and release are and . represents the storage tank capacity. The hydrogen quantity sold at time k is , with hydrogen being sold every 10 days.

3. Rule-Based Scheduling Strategy for Normal and Fault Conditions

3.1. Three Operating Modes in Normal Scenarios

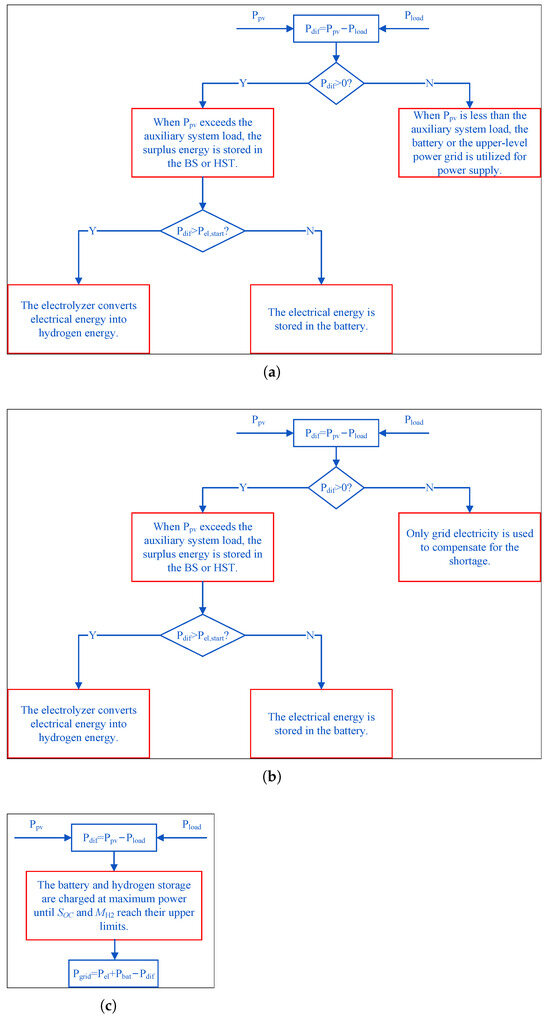

Meteorological data exhibit a wide range of variations throughout the year with a high degree of regularity. Therefore, according to the weather forecast and time of use (TOU) electricity prices, three operational modes are established for normal operation, as depicted in Figure 3 and summarized in Table 2. is defined as the difference between PV output and load demand. Sunny and cloudy days are classified based on whether the maximum value of exceeds 0 (sunny) or falls below 0 (cloudy) during the scheduling cycle.

Figure 3.

Three operating modes in normal scenarios: (a) Mode 1: peak or flat power periods on sunny days, or during peak periods on cloudy days; (b) Mode 2: cloudy flat electricity periods; (c) Mode 3: valley electricity price periods.

Table 2.

Operating modes under various conditions.

Mode 1:

During peak or flat periods on sunny days, or during peak periods on cloudy days, when PV output exceeds the load demand, the excess PV power is supplied to the HESS. When , the PV power is directed to the electrolyzer. Otherwise, it charges the battery. When PV power is insufficient, both the battery and the grid are used to compensate for the shortage.

Mode 2:

During flat periods on cloudy days, only grid electricity is used to compensate for the shortages. The battery retains energy for peak demand, reducing grid purchases.

Mode 3:

During valley periods, both on sunny and cloudy days, the grid is used to charge batteries and produce hydrogen to realize “valley filling”. This approach leverages the lower electricity prices during off-peak times compared to peak periods. The hydrogen produced can be sold, thereby potentially increasing economic benefits through revenue from hydrogen sales.

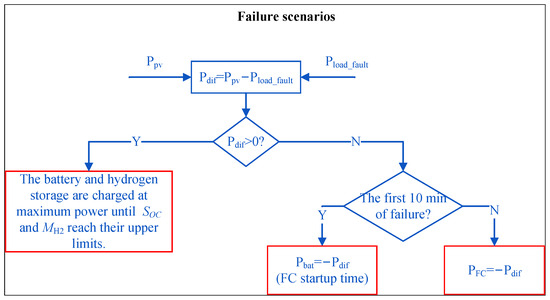

3.2. Operating Mode in Fault Scenarios

In the event of a fault, the microgrid operates off-grid to ensure uninterrupted power to the substation’s critical loads (Figure 4). The priority is to utilize PV power first, followed by the Hybrid Energy Storage System (HESS) for continued supply. Fuel cells typically require about 10 min to start and reach optimal operating conditions. During this startup period, the lithium battery discharges to provide the necessary power. This 10-min discharge window is crucial as it bridges the gap before the fuel cells become fully operational. Once the fuel cells are ready, they are activated to generate power, ensuring a seamless transition and sustained energy supply to the critical loads. This coordinated approach leverages the quick response time of lithium batteries and the long-term stability of fuel cells to maintain continuous power.

Figure 4.

Operating mode in fault scenarios.

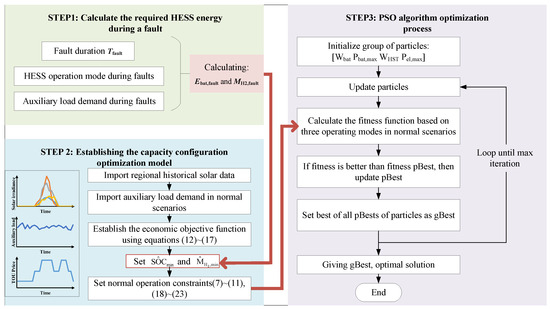

4. Modeling and Algorithm for Capacity Configuration

This section proposes the capacity configuration optimization model for the electric–hydrogen microgrid, incorporating critical thresholds for energy reserves to ensure system robustness under fault conditions. The goal is to design a model that minimizes the total net present value cost of microgrid substation investment while ensuring reliable operation. The section is divided into three steps.

4.1. STEP 1: Calculate the Required HESS Backup Energy During a Fault

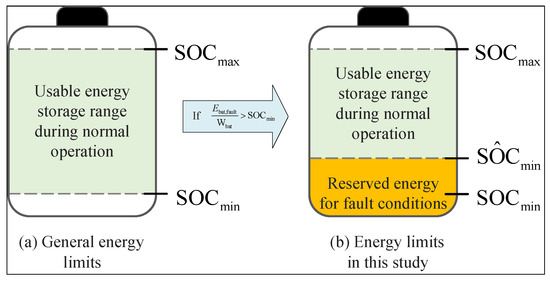

When a sudden fault causes the substation to lose external power, the HESS must have enough energy to support the substation auxiliary loads. Considering the worst-case scenario of zero PV power, only energy storage is used to ensure power supply. According to Figure 5, the required energy calculations for the lithium battery and hydrogen storage tank are as follows:

where and represent the overall safety margin of HESS and the safety margin of lithium batteries, respectively, with values greater than 1. denotes the required fault support duration, and denotes the fuel cell startup time. and represent the required storage energy for the lithium battery and hydrogen storage tank during fault conditions.

Figure 5.

Proposed energy management strategy for the battery storage system.

Therefore, during normal operation, the lithium battery’s SOC and the hydrogen storage tank’s should not fall below the required levels for fault conditions.

where and denote the original lower limit SOC of the battery and lower limit of the hydrogen pressure percentage in the tank to ensure operational performance. and denote the lower limits under this capacity configuration strategy.

4.2. STEP 2: Establishing the Capacity Configuration Optimization Model

The energy storage configuration optimization model is designed from an economic perspective; both objective functions and constraints of the model are provided in this step.

4.2.1. Objective Function

The proposed configuration model is designed to minimize the total net present value cost of microgrid substation investment. This is a comprehensive economic calculation summing all capital expenditures (CapEx) and operational expenditures (OpEx), while subtracting revenues from hydrogen sales over the project’s planning horizon.

where , , , , and represent the equipment purchase costs, equipment replacement costs, operation and maintenance costs, power purchase costs and income from electricity and hydrogen sales in year i, respectively. r denotes the discount rate, and Y symbolizes the economic life cycle of the project. The five economic indicators are calculated as follows:

where N denotes the number of equipment. indicates the purchase cost per unit of equipment j, and defines the installed capacity of equipment j. indicates the replacement cost per unit of equipment j, indicates the number of replacements, determined by the service life of equipment j. symbolizes the operation and maintenance cost per unit capacity of equipment j. denotes the electricity price at time k. represents the grid power at time k, indicates the selling price of hydrogen, and means the volume of hydrogen sold at time k.

4.2.2. Constraints

In order to ensure the energy balance and meet the requirements of stable operation, the following are the remaining constraints of the optimization model. These constraints model the physical and operational limits of the microgrid. Equation (19) represents the primary power balance constraint, ensuring generation matches demand at all times. Equations (20)–(22) enforce the physical operating limits of the microgrid components, including the critical fault-reserve energy thresholds (, ) derived in Section 4.1. Finally, Equations (23) and (24) model the grid connection constraints and the renewable energy efficiency limits.

where and are the minimum and maximum output power of equipment i, respectively. In addition, represents the actual power of the equipment i, and and denote the upper limit SOC of the battery and the upper limit of the percentage of hydrogen pressure in the tank, respectively. denotes the upper limit of power exchanged with the main grid. defines the abandoned PV power, denotes total PV power generation, and indicates the maximum allowable PV power abandonment rate.

4.3. STEP 3: Solving It Using PSO

The rule-based operation strategy cannot be simply translated into mathematical constraints because it involves complex timing logic judgments and computational models. To address this challenge, we employ the PSO (Particle Swarm Optimization) algorithm to optimize this model. The PSO algorithm searches for an optimal solution by simulating the behavior of a flock of birds, which provides us with an effective way to solve this type of problem. The particle swarm consists of four decision variables: battery capacity (), battery power (), hydrogen storage tank capacity (), and electrolyzer power (). pBest represents the best remembered fitness value for each particle, and gBest represents the globally best fitness value across the entire swarm. The particle size is 100, and the maximum iteration is 50. The PSO algorithm is thus utilized to find the optimal set of decision variables that minimizes the objective function, while respecting all constraints, including the fault-reserve thresholds (Figure 6). For details on the PSO algorithm, please refer to Ref. [34].

Figure 6.

Flowchart of the capacity configuration algorithm.

5. Case Study

To demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed microgrid, the case study takes a 220 kV substation as an example to construct an electric–hydrogen backup power microgrid and calculate its capacity configuration. The unit capacity of photovoltaic power is 30 kW, with a maximum allowable abandonment rate of photovoltaic power set at 3% according to experience. Meteorological data, including sunlight radiation and temperature for a typical year in a specific region of Northwest China, are obtained from Meteonorm software (version 8.0). During normal operations, hydrogen is transported and sold every 10 days. The economic parameters of the electric hydrogen backup power microgrid are presented in Table 3, while the electricity prices by time of use are shown in Table 4. Detailed technical parameters are listed in Appendix A.

Table 3.

Economic parameters of the electric–hydrogen backup power microgrid.

Table 4.

Time-of-use grid electricity price.

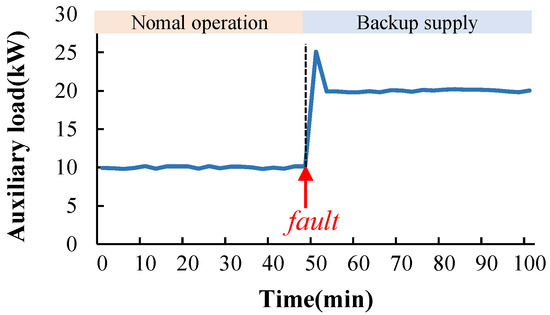

According to Table 1, under normal conditions, the auxiliary load is stable at around 10 kW throughout the day, with slight fluctuations. In the event of a fault, the uninterrupted load increases to approximately 20 kW, including additional loads like UPS and emergency lighting. At the moment of failure, the breakers and switches require temporary power from the microgrid, with a potential peak power demand of up to 25 kW (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Auxiliary load demand during normal and fault condition.

5.1. Calculation of HESS Capacity Required for Fault Support

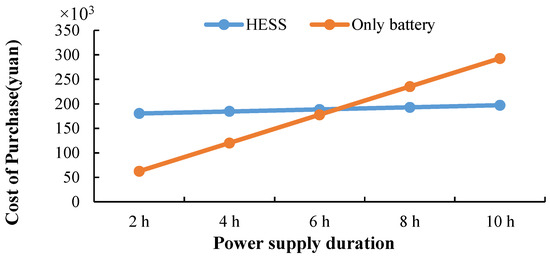

Typically, the specified fault support time for a substation is 2 h. However, due to uncertainty in the duration of the fault, this study assumes a 10-h support time for critical loads and evaluates scenarios ranging from 2 to 10 h for economic analysis. This approach prevents the substation load from being affected by prolonged faults, which could lead to more extensive failures. A comparison is made between the battery-only power supply and the electric–hydrogen HESS microgrid power supply.

To ensure the system has sufficient margin to handle uncertainties in actual use, both energy storage systems are configured at 1.2 times the required capacity. Furthermore, in the HESS scenario, lithium batteries are configured at 2.5 times the required capacity. The calculations are performed using Equation (7)–(10). To ensure the responsiveness of the backup power source, the short-term power from relay protection is handled by the battery, thus the fuel cell only needs 20 kW. The configuration and economic results are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

The configuration results of different power supply time requirements in fault scenarios.

Figure 8 shows the comparison of purchasing costs for two energy storage strategies. The results indicate that when the power supply duration exceeds 7 h, using HESS is more cost-effective than using only batteries. In particular, for 8-h and 10-h power supply durations, the cost of using HESS is 17.96% and 32.63% lower, respectively, compared to batteries. This demonstrates that as power supply time increases, the cost advantage of HESS over batteries grows, leading to better overall economy.

Figure 8.

Purchasing cost at different power supply durations.

Additionally, since the energy storage components (hydrogen storage tank) and energy supply components (fuel cells) of hydrogen energy storage are independent, expanding the capacity of hydrogen storage is more convenient. Given that hydrogen storage tanks are much cheaper than fuel cells and batteries, this significantly reduces costs. Furthermore, with advancements in hydrogen storage technology, HESS will become increasingly competitive for large-capacity emergency energy storage in the future.

5.2. Optimized Configuration Results for HESS Capacity

To confirm the advantages of the proposed microgrid backup power system, three substation backup power system scenarios are designed:

- No microgrid, relying solely on a lithium battery for backup power.

- No PV system, relying on a combination of lithium batteries and hydrogen storage for backup power.

- Integrates both PV and HESS, representing the proposed backup power system in this paper.

In comparing the optimization results of the three backup power systems (Table 6), the battery rated power is 25 kW in all cases, matching the power required in fault scenarios. This is because the difference between the photovoltaic output (maximum 30 kW) and the auxiliary load power (around 10 kW during normal operation) is less than 25 kW, so the battery charging and discharging power needed for daily operations is not high.

Table 6.

Comparison of optimization results for substation backup power system scenarios.

Scenario I: To ensure 10 h of power supply during a fault, a large battery capacity is required, significantly increasing the equipment purchase cost. Although lithium batteries provide peak shaving and valley filling during normal operations, reducing the system’s grid power purchase cost, their peak-valley arbitrage income is limited due to the station transformer capacity, leading to wasted battery capacity.

Scenario II: After introducing the hydrogen storage system, hydrogen storage can produce hydrogen in large quantities during off-peak electricity prices, providing peak shaving, valley filling, and hydrogen sales revenue. Because the unit capacity cost of hydrogen storage tanks is much lower than that of lithium batteries, the battery capacity is reduced to the minimum needed to ensure power during faults, 10 kWh. The capacity of the hydrogen storage tank far exceeds the energy required by the system during faults, demonstrating that producing green hydrogen not only benefits the system economically but also ensures power supply during faults without conflict.

Scenario III: Adding a PV system enables the substation auxiliary system to achieve self-sufficiency through photovoltaic power generation. Excess photovoltaic energy can be used to produce green hydrogen, reducing the required grid power while significantly protecting the environment.

In all three scenarios, as the electric–hydrogen backup power microgrid becomes more complete, the total net present value cost gradually decreases. The total net present value cost in Scenario III is reduced by 46.55% compared to Scenario I and by 36.51% compared to Scenario II. This indicates that combining hydrogen storage and PV systems in the microgrid design not only optimizes battery capacity allocation and reduces overall costs but also achieves a win-win situation for environmental protection and economic benefits, and ensures long-term power supply for the substation auxiliary system in emergency situations.

In conclusion, microgrid application has significant advantages regarding environmental and economic benefits.

5.3. Microgrid Operation Analysis

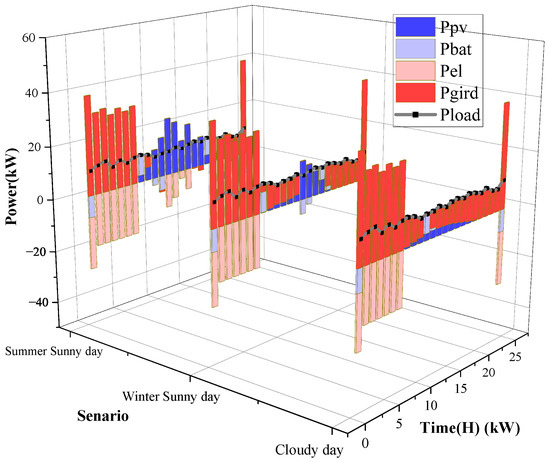

This section analyzes the daily operation of the microgrid based on the optimal capacities (e.g., 13 kWh battery and 2836 kWh H2 tank) obtained in Section 5.2. The final and are calculated as defined by Equations (11) and (12). This calculation results in an enforced battery SOC range of (0.769, 0.9), which is significantly higher than the physical limit of (0.2, 0.9), and a range of (0.2, 0.8). With these specific operational constraints now defined, three typical days were chosen to simulate daily operations, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Power distribution results for three scenarios.

During valley grid electricity price hours (23:00–7:00), the electrolyzer operates at full power to produce hydrogen as the revenue from hydrogen production exceeds the cost of purchasing electricity. During other periods, surplus photovoltaic energy is used to produce green hydrogen if it exceeds the starting power of the electrolyzer. Due to the limited capacity of the lithium batteries and the requirement to maintain sufficient minimum storage capacity for fault demand, they only provide a limited capacity for peak shaving.

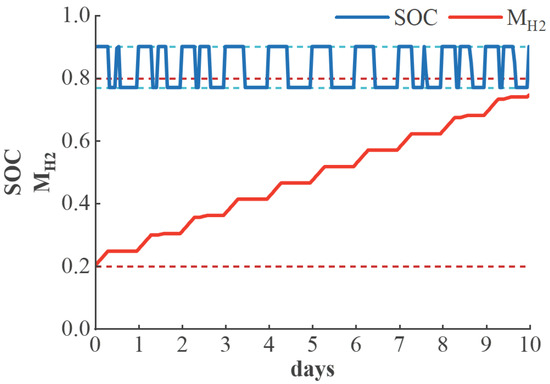

Figure 10 shows the SOC and results over a 10-day normal operation period. The dotted lines indicate the operational limits constrained by the fault backup requirements. The results confirm that both fall within these enforced ranges, with hydrogen being sold on the 10th day.

Figure 10.

SOC and results over a 10-day normal operation period.

This strategy maintains lithium batteries at a lower Depth of Discharge (DoD), thereby reducing stress and enhancing durability and reliability of the battery cells [35,36]. It enables the system to withstand unexpected disruptions while optimizing the longevity and performance of the energy storage components.

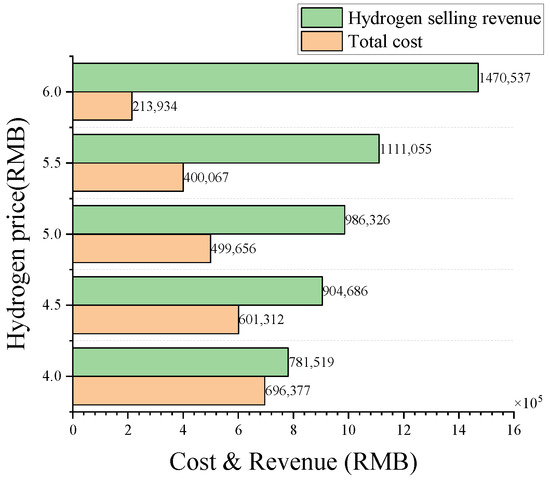

5.4. Influence of Hydrogen Pricing

To further analyze the impact of hydrogen market price on the substation auxiliary system, a sensitivity analysis is provided in this section. The price of hydrogen at the hydrogen refueling station is set at 6.25 yuan/m3, which establishes the upper limit for the microgrid’s selling price. Five hydrogen price levels are selected for economic calculation in the entire life cycle, as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

The relationship between hydrogen pricing and yield.

The results suggest that as the hydrogen price increases, the total cost decreases while the hydrogen selling revenue increases. In particular, for every 0.5 yuan increase in hydrogen price, the net present value total cost decreases successively by 15.47%, 31.29%, 47.11%, and 62.94%. From an economic perspective, a higher hydrogen price results in greater benefits. However, from the perspective of the microgrid itself, the price of hydrogen should not be set too high to improve market competitiveness.

Based on the analysis of hydrogen production, storage, and transportation costs, a price of 5 yuan/m3 appears appropriate. Increasing the hydrogen price beyond this point is unlikely to yield substantial benefits. Furthermore, this price is lower than the market price, enhancing the feasibility of selling hydrogen to nearby refueling stations.

6. Conclusions

This paper introduces a microgrid for substation auxiliary systems, serving as a backup power source with a PV system, battery storage, and hydrogen storage, replacing traditional lead–acid battery or diesel generator approaches. According to calculations, for a 220 kV substation, the available rooftop area can be utilized to install 30 kW of PV panels. This improvement maximizes substation space with solar and hydrogen equipment, generating profits and cleaner energy. It also smooths electricity demand patterns and enables black start capability during faults.

Then, energy dispatch strategies for normal and fault scenarios were formulated for the microgrid, considering the startup power of electrolyzers and the startup time of fuel cells. Based on this, an optimization model for capacity configuration was established to simultaneously meet fault demand and daily operational needs. The process involves three key steps: Step 1 calculates the required HESS backup energy during a fault, Step 2 establishes the capacity configuration optimization model from an economic perspective, and Step 3 utilizes the PSO algorithm to solve the model and investigate parameter sensitivity.

The results indicate that for fault support alone, when the required support duration exceeds 7 h, using HESS is more cost-effective than relying solely on batteries. In particular, for support durations of 8 h and 10 h, the cost using HESS is 17.96% and 32.63% lower, respectively, compared to batteries. When considering daily operational economics, the proposed microgrid backup power system results in a 46.55% reduction in total net present value cost compared to a lithium battery-only system and a 36.51% reduction compared to a system with hydrogen storage but no PV. Under the proposed capacity constraints to ensure the required energy during faults, the SOC range for the battery during normal operation is restricted to (0.769, 0.9). This maintains a lower Depth of Discharge (DoD), enhancing durability of the battery cells. This design provides significant environmental benefits by producing green hydrogen and reducing grid power consumption, and it ensures long-term power supply reliability for substation auxiliary systems. Therefore, the microgrid application demonstrates clear advantages in both economic and environmental aspects.

Furthermore, by establishing the proposed microgrid at the substation, it is possible to integrate distributed energy sources scattered throughout cities, thereby enhancing the flexibility of the power system. Additionally, utilizing substations as hydrogen refueling stations offers significant advantages. These sites are not only widely distributed but, crucially, they are already staffed by professional maintenance personnel. This existing technical expertise in managing complex energy systems provides a strong foundation for safely overseeing the physical and cyber–physical security of new hydrogen infrastructure [37]. Consequently, the configuration methods discussed in this paper hold significant potential for widespread application, as they are applicable to any substation equipped with auxiliary systems, with the configuration outcomes primarily influenced by the scale and safety requirements of the specific auxiliary system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.S.; Methodology, Y.B.; Software, Y.B. and Q.X.; Validation, Q.X. and J.M.; Formal analysis, Q.X. and J.M.; Investigation, Q.X. and Z.S.; Resources, Z.S.; Data curation, Q.X. and J.M.; Writing—original draft, Y.B.; Writing—review & editing, K.Y.; Visualization, Y.B.; Supervision, K.Y.; Project administration, K.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Development Plan of the Urumqi-Changji-Shihezi National Independent Innovation Demonstration Zone within the Silk Road Economic Belt Innovation-Driven Development Pilot Zone, grant number 2023112806.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

The parameters of the electric–hydrogen backup power microgrid are shown in Table A1.

Table A1.

Parameters of the electric–hydrogen backup power microgrid.

Table A1.

Parameters of the electric–hydrogen backup power microgrid.

| NAME | VALUE |

|---|---|

| PV panel lifetime (years) | 25 |

| Lithium battery lifetime (years) | 10 |

| Electrolyzer lifetime (years) | 20 |

| Hydrogen storage tank lifetime (years) | 25 |

| Fuel cell lifetime (years) | 20 |

| Lithium battery charge/discharge efficiency | 0.95/0.95 |

| Electrolyzer efficiency | 0.7 |

| Fuel cell efficiency | 0.5 |

| Hydrogen storage tank efficiency | 0.98 |

| Maximum SOC of lithium battery | 0.9 |

| Minimum SOC of lithium battery | 0.2 |

| Maximum of hydrogen storage tank | 0.9 |

| Minimum of hydrogen storage tank | 0.2 |

| Electrolyzer minimum starting power ratio | 0.1 |

| Fuel cell startup time | 10 min |

References

- Huang, Q.; Jing, S.; Li, J.; Cai, D.; Wu, J.; Zhen, W. Smart Substation: State of the Art and Future Development. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2017, 32, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wu, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; Mu, J. Research on the Architecture of Integrated Platform of Intelligent Substation Auxiliary Monitoring System. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2095, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, P. Micro-grid System in Auxiliary Power System of Substation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics 2019; Hassanien, A.E., Shaalan, K., Tolba, M.F., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1065–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss, C.R.; Hardy, B.J. (Eds.) Chapter 4—Substation Auxiliary Power Supplies. In Transmission and Distribution Electrical Engineering, 4th ed.; Newnes: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 121–156. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Yang, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, X.; Ma, M.; Zeng, G. A new dynamic SOH estimation of lead-acid battery for substation application. Int. J. Energy Res. 2017, 41, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancauskas, J.R.; Shook, D.A. Optimization of station battery replacement [nuclear plant]. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 1994, 41, 1384–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Song, W.; Son, D.-Y.; Ono, L.K.; Qi, Y. Lithium-ion batteries: Outlook on present, future, and hybridized technologies. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 2942–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.; Arcanjo, A.; Vasconcelos, A.; Silva, W.; Azevedo, C.; Pereira, A.; Jatobá, E.; Filho, J.B.; Barreto, E.; Villalva, M.G.; et al. Development of a Method for Sizing a Hybrid Battery Energy Storage System for Application in AC Microgrid. Energies 2023, 16, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukumar, P.; Kumar, A.; Afzal, M.; Bhogilla, S.; Sharma, P.; Parida, A.; Jana, S.; Kumar, E.A.; Pai, R.K.; Jain, I.P. Review on large-scale hydrogen storage systems for better sustainability. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 33223–33259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Cruz-Soto, J.; Azkona-Bedia, I.; Velazquez-Limon, N.; Romero-Castanon, T. A techno-economic study for a hydrogen storage system in a microgrid located in baja California, Mexico. Levelized cost of energy for power to gas to power scenarios. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 30050–30061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, S.; Gunduz, H.; Yildirim, B.; Özdemir, M. An islanded microgrid energy system with an innovative frequency controller integrating hydrogen-fuel cell. Fuel 2022, 326, 125005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Li, T.; Xu, W.; Xiang, Y.; Su, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, F. Chance-constrained energy-reserve co-optimization scheduling of wind-photovoltaic-hydrogen integrated energy systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 6892–6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Pouget, J.; Letrouvé, T.; Jecu, C.; Joseph-Auguste, L. Techno-economic design methodology of hybrid energy systems connected to electrical grid: An application of hybrid railway power substation. Math. Comput. Simul. 2019, 158, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obara, S. Resilience of the microgrid with a core substation with 100% hydrogen fuel cell combined cycle and a general substation with variable renewable energy. Appl. Energy 2022, 327, 120060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, B.; Zhang, J. Study on the application of hydrogen fuel cell in substation. Autom. Appl. 2018, 108–109. [Google Scholar]

- A comprehensive Review of Floating Photovoltaic Systems: Tech Advances, Marine Environmental Influences on Offshore PV Systems, and Economic Feasibility Analysis. Sol. Energy 2024, 277, 112711. [CrossRef]

- Hoff, T.; Shugar, D.S. The value of grid-support photovoltaics in reducing distribution system losses. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 1995, 10, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araujo Silva Júnior, W.; Vasconcelos, A.; Arcanjo, A.C.; Costa, T.; Nascimento, R.; Pereira, A.; Jatobá, E.; Filho, J.B.; Barreto, E.; Dias, R.; et al. Characterization of the Operation of a BESS with a Photovoltaic System as a Regular Source for the Auxiliary Systems of a High-Voltage Substation in Brazil. Energies 2023, 16, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabares, A.; Martinez, N.; Ginez, L.; Resende, J.; Brito, N.; Franco, J. Optimal Capacity Sizing for the Integration of a Battery and Photovoltaic Microgrid to Supply Auxiliary Services in Substations under a Contingency. Energies 2020, 13, 6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribič, J.; Pihler, J.; Maruša, R.; Kokalj, F.; Kitak, P. Lead-Acid Battery Sizing for a DC Auxiliary System in a Substation by the Optimization Method. Energies 2019, 12, 4400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, A.; Cavalcanti, G.O.; Feitosa, M.A.F.; Dias Filho, R.F.; Pereira, A.C.; Jatobá, E.B.; de Melo Filho, J.B.; Marinho, M.H.N.; Converti, A.; Gómez-Malagón, L.A. Optimal Sizing of a Photovoltaic/Battery Energy Storage System to Supply Electric Substation Auxiliary Systems under Contingency. Energies 2023, 16, 5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Zhou, K. A distributionally robust optimization approach for optimal load dispatch of energy hub considering multiple energy storage units and demand response programs. J. Energy Storage 2024, 78, 110085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.-X.; Liu, H.-H.; Cheng, P.; Ren, X.-Y.; Pi, H.-D.; Li, L.-L. Phased optimization of active distribution networks incorporating distributed photovoltaic storage system: A multi-objective coati optimization algorithm. J. Energy Storage 2024, 91, 112093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.-B.; Zou, W.-J.; Jung, S.; Kim, Y.-B. Optimized rule-based energy management for a polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell/battery hybrid power system using a genetic algorithm. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 7932–7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, G.L.; Rodriguez, R.S.; Alvarado, V.M.; Gomez-Aguilar, J.F.; Mota, J.E.; Sandoval, C. Hybrid PEMFC-supercapacitor system: Modeling and energy management in energetic macroscopic representation. Appl. Energy 2017, 205, 1478–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dib, M.; Nejmi, A.; Ramzi, M. New auxiliary services system in a transmission substation in the presence of a renewable energy source PV. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 27, 3151–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.J.; Wilson, D. Auxiliary DC Control Power System Design for Substations. In Proceedings of the 2007 60th Annual Conference for Protective Relay Engineers, College Station, TX, USA, 27–29 March 2007; pp. 522–533. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Wang, R.; Yang, Z. Substation DC system intelligent monitor and maintenance system. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 2nd Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC), Chongqing, China, 25–26 March 2017; pp. 2068–2072. [Google Scholar]

- Pilat, N.; Perić, A.; Ban, Ž.; Šunde, V. Analysis of the uninterruptible power supply influences to the power grid. In Proceedings of the 2019 42nd International Convention on Information and Communication Technology, Electronics and Microelectronics (MIPRO), Opatija, Croatia, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 180–185. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Huang, L.; Ren, J.; Lan, Y.; Li, M.; Xiao, H. Numerical study of the effect of barrier wall on liquid hydrogen leakage and dispersion. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 142, 460–471, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Deveci, M.; Yan, J.; Liu, Y. Optimal capacity configuration of wind-photovoltaic-storage hybrid system: A study based on multi-objective optimization and sparrow search algorithm. J. Energy Storage 2024, 85, 110983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; Peng, J.; Yin, R.; Li, H.; Li, S.; Yan, J.; Yang, H. Capacity configuration of distributed photovoltaic and battery system for office buildings considering uncertainties. Appl. Energy 2022, 319, 119243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basaran, K.; Öztürk, H. Optimal expansion planning of electrical energy distribution substation considering hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 75, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonyadi, M.R.; Michalewicz, Z. Particle Swarm Optimization for Single Objective Continuous Space Problems: A Review. Evol. Comput. 2017, 25, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khizbullin, R.; Chuvykin, B.; Kipngeno, R. Research on the Effect of the Depth of Discharge on the Service Life of Rechargeable Batteries for Electric Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Industrial Engineering, Applications and Manufacturing (ICIEAM), Sochi, Russia, 16–20 May 2022; pp. 504–509. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Zhu, C.; Goetz, S.M. Fault-Tolerant Multiparallel Three-Phase Two-Level Converters with Adaptive Hardware Reconfiguration. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 3925–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xiahou, K.; Du, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Q.H. Security Assessment of Cascading Failures in Cyber-Physical Power Systems with Wind Power Penetration. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2025, 40, 4480–4492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).