Improved Coordinated Control Strategy for Auxiliary Frequency Regulation of Gas-Steam Combined Cycle Units

Abstract

1. Introduction

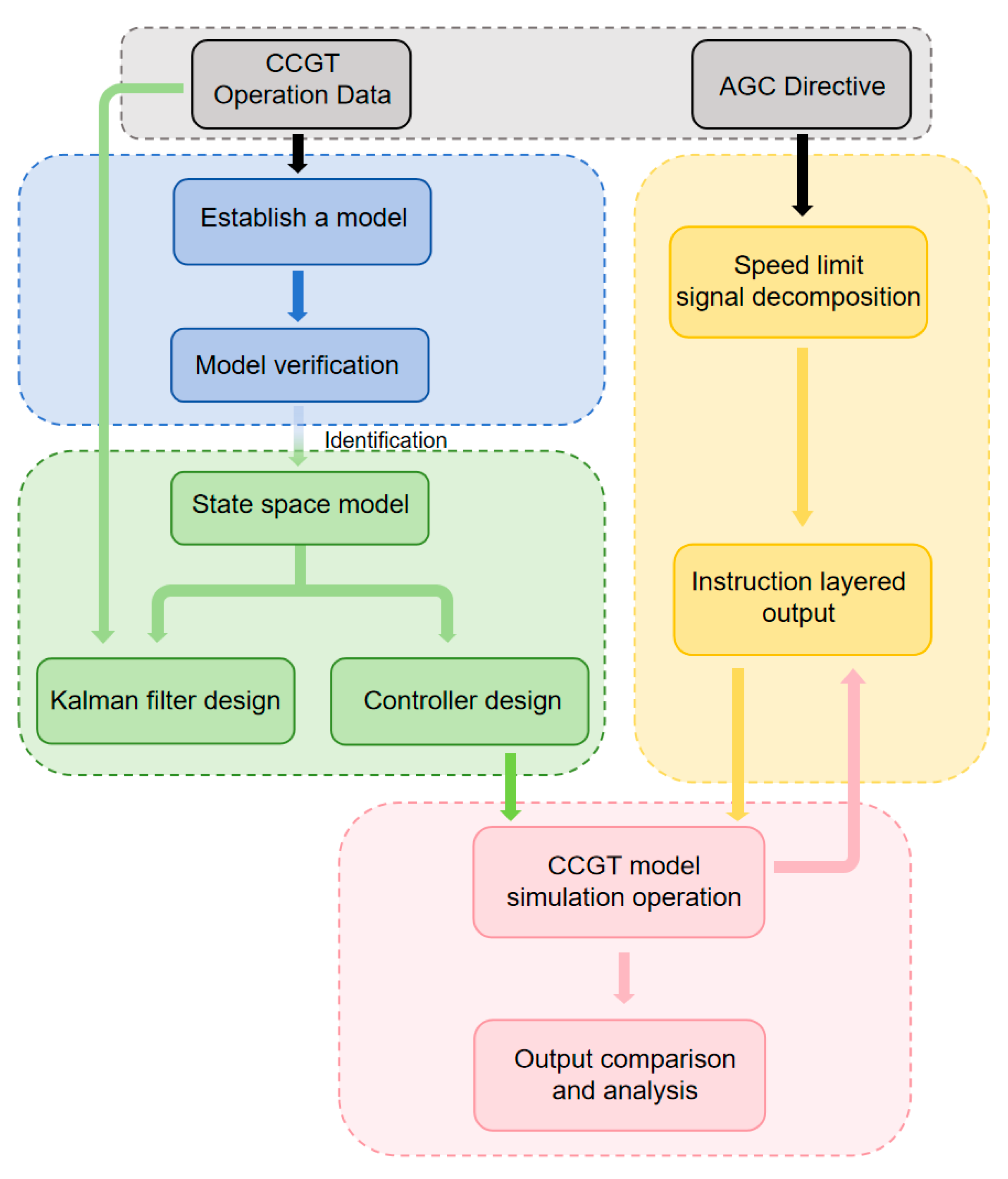

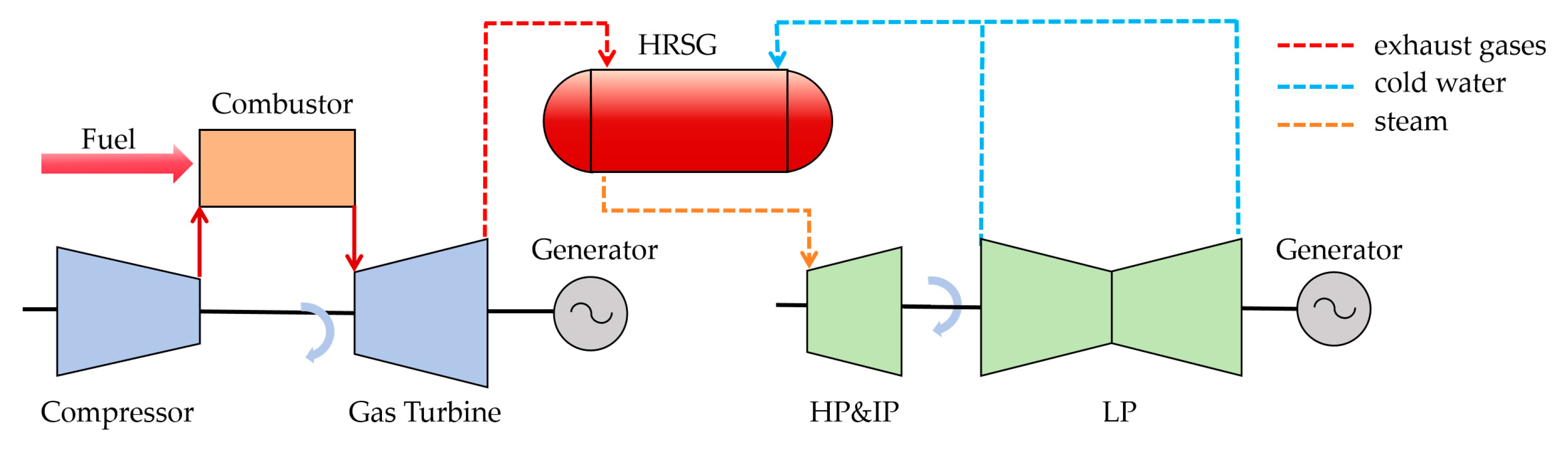

2. Control-Oriented Dynamic Modeling of F-Class Combined Cycles

2.1. Introduction to the F-Class Gas–Steam Combined Cycle Units

2.2. Combined Cycle Modeling Method

2.2.1. GT Modeling

2.2.2. HRSG Modeling

2.2.3. ST Modeling

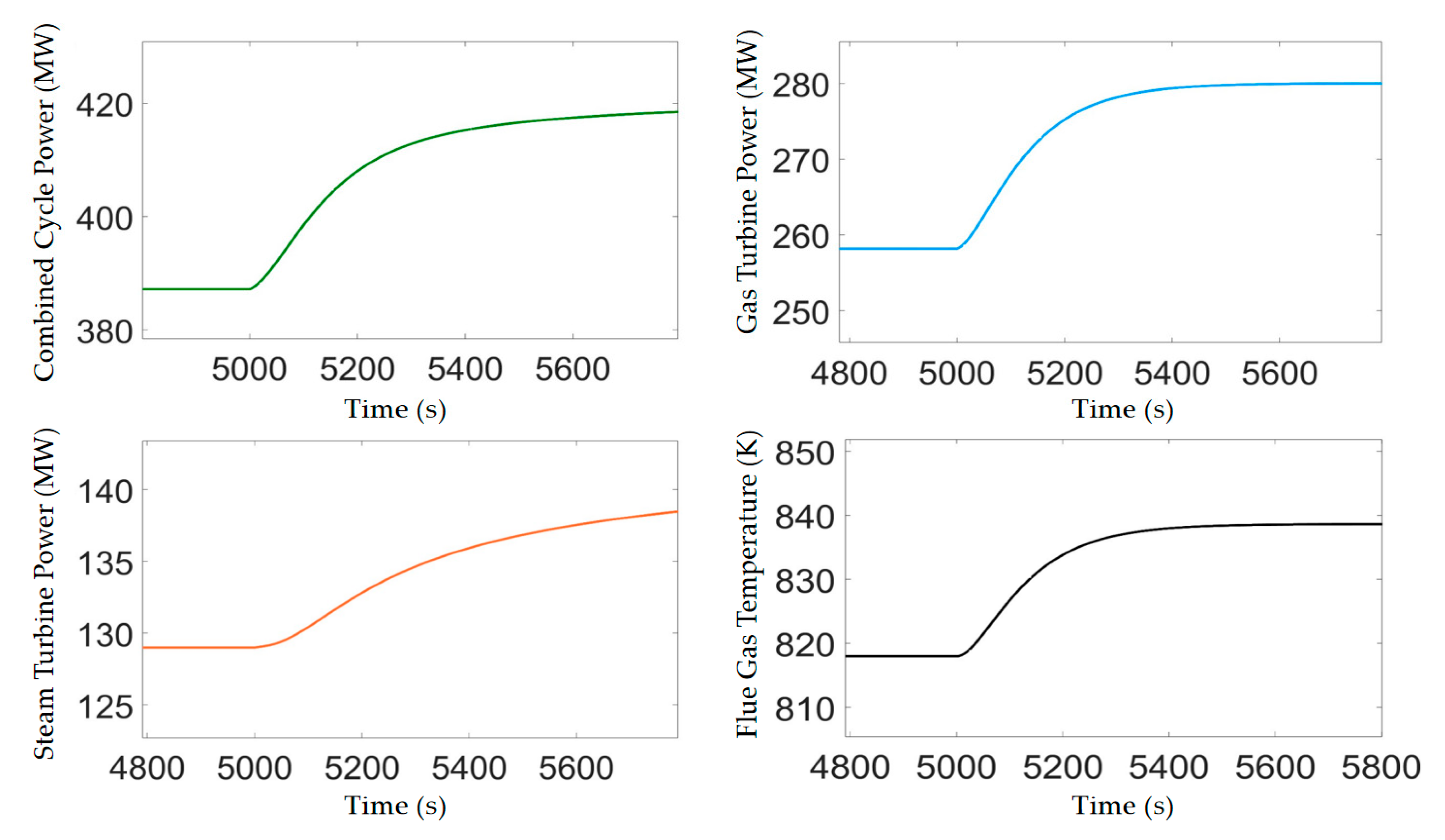

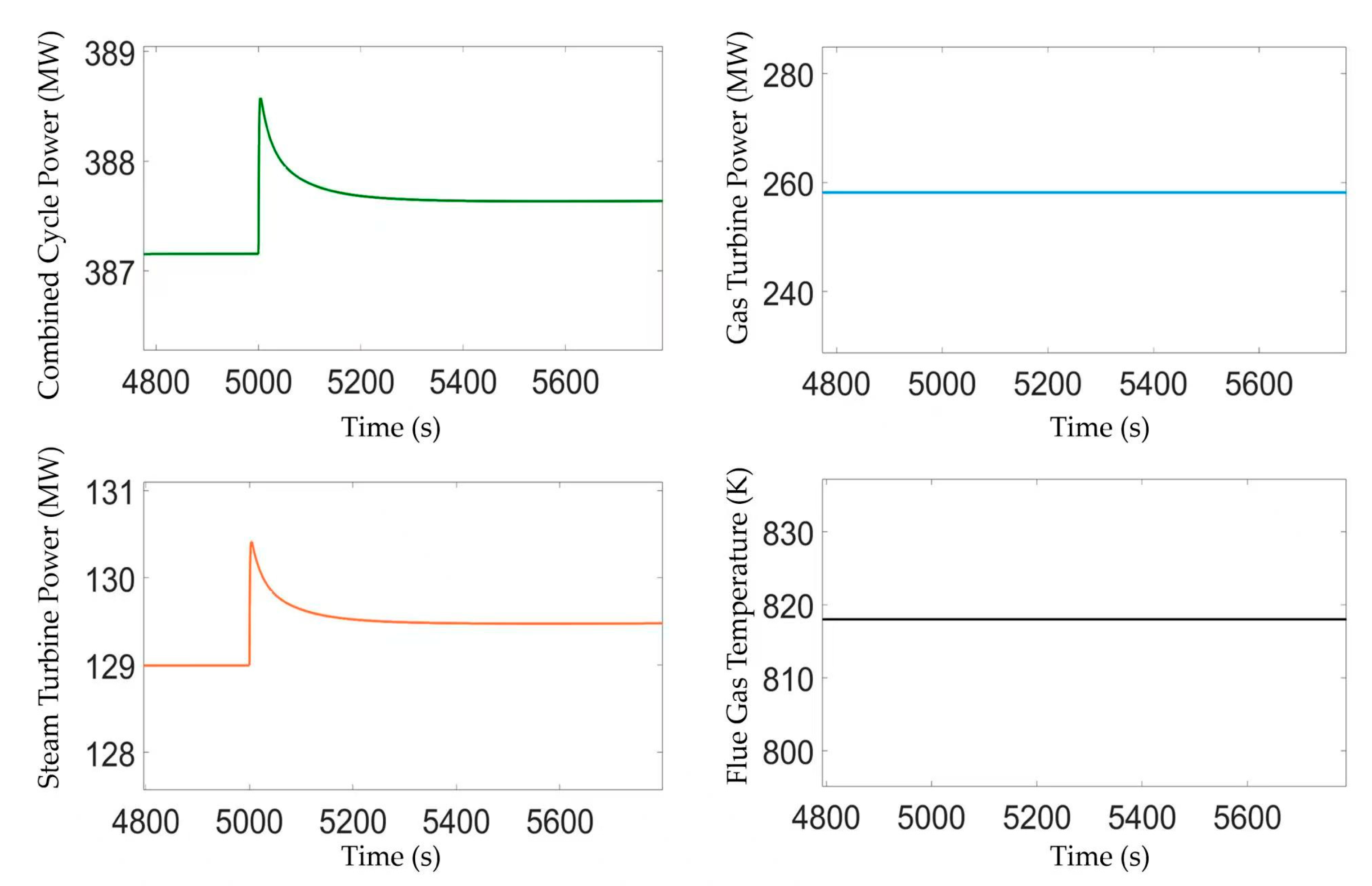

2.3. Dynamic Characteristics Analysis of Combined Cycle Units

2.3.1. Verification on the CCGT Model

2.3.2. Analysis on Dynamic Coupling Characteristics

3. Design of Distributed Predictive Controllers

3.1. Introduction to Controller Design

3.2. Model Predictive Control Method

3.2.1. Predictive Model

3.2.2. Optimization Objective

3.2.3. CCGT Operational Constraints

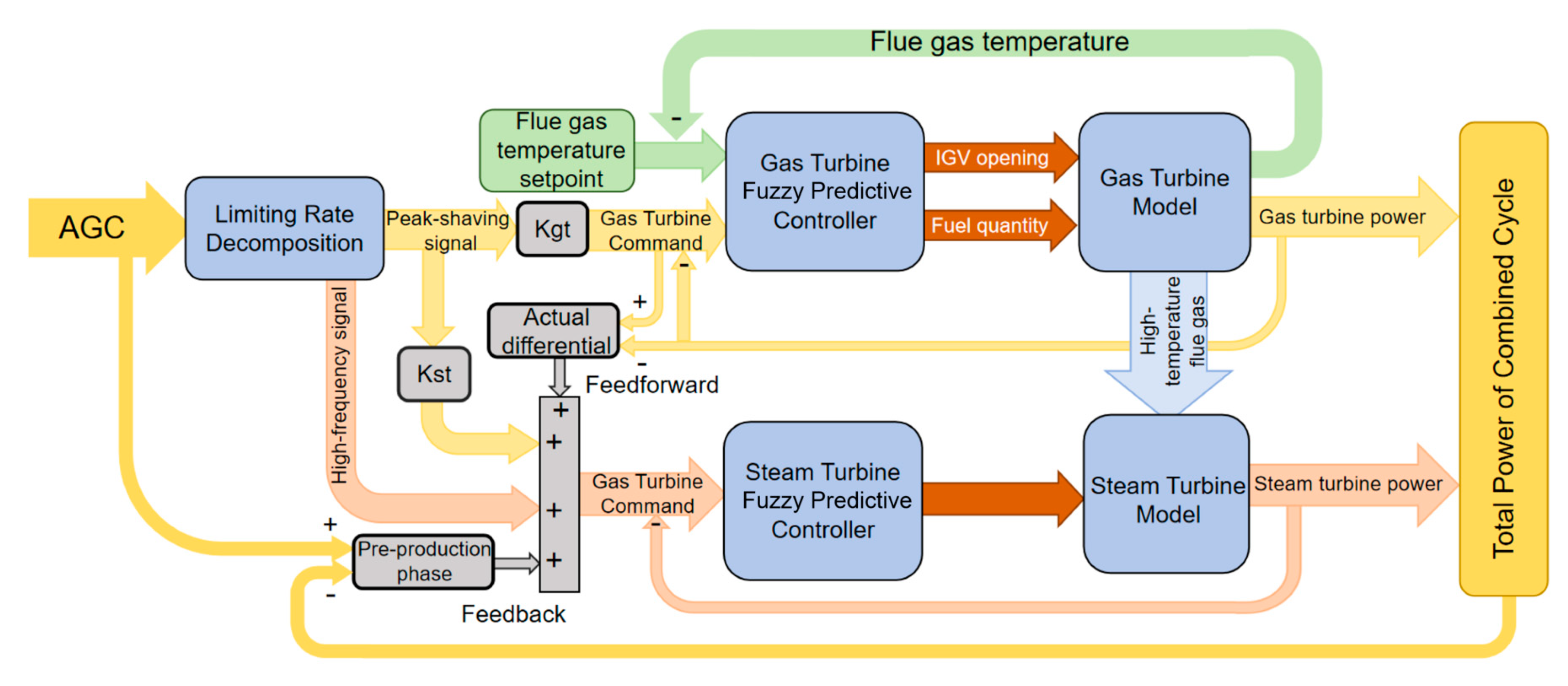

4. Strategy for Frequency Modulation: Improved Coordinated Control

4.1. Basic Control Strategy for Gas Turbine-Steam and Turbine Systems

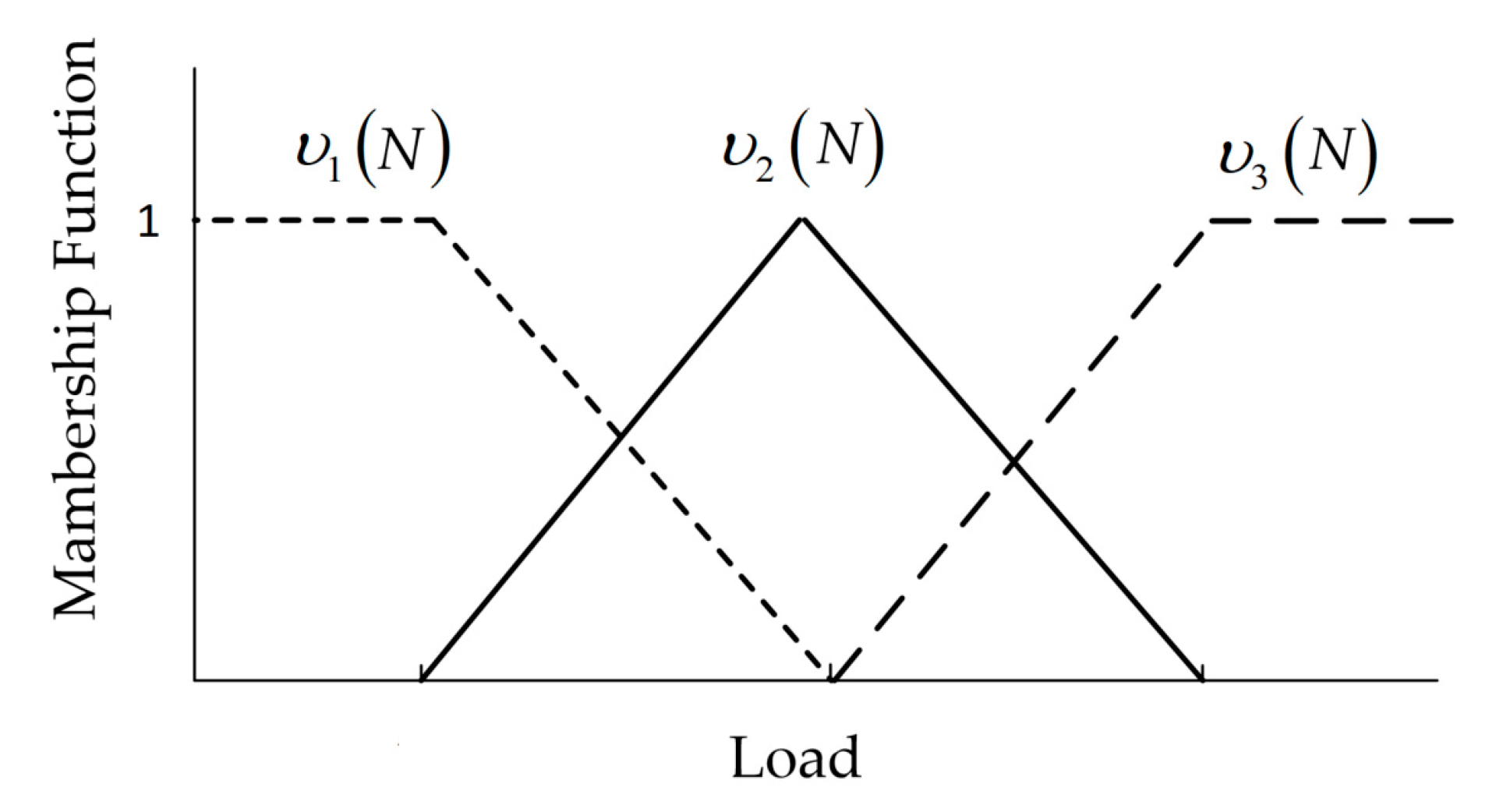

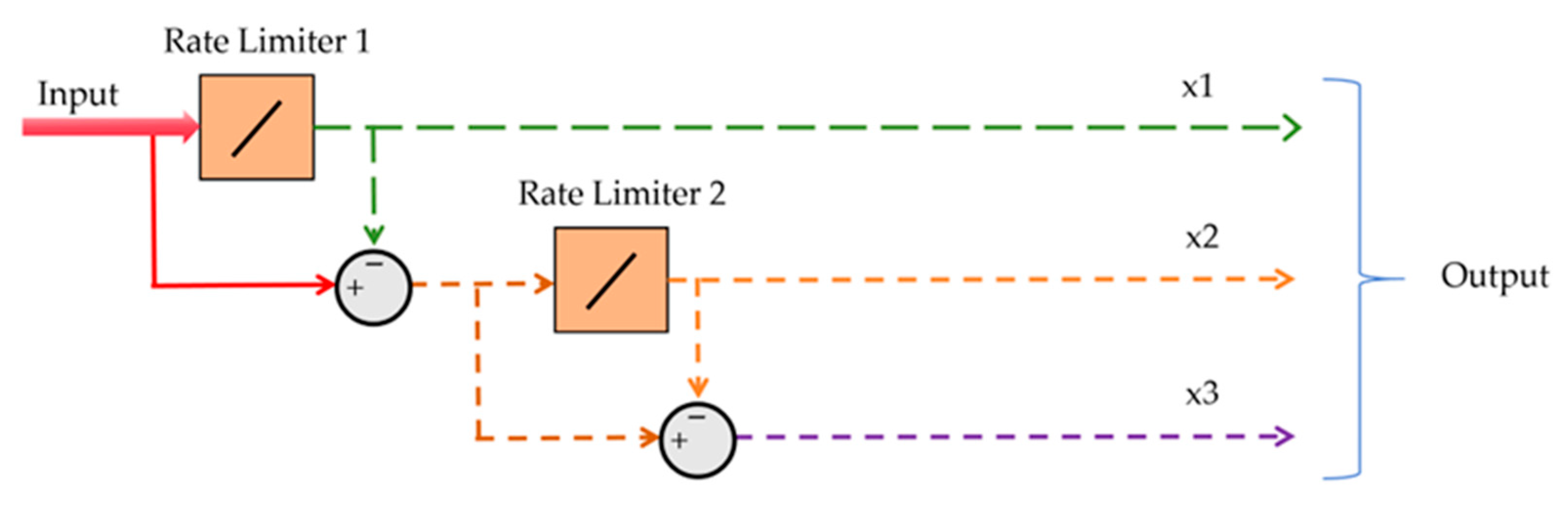

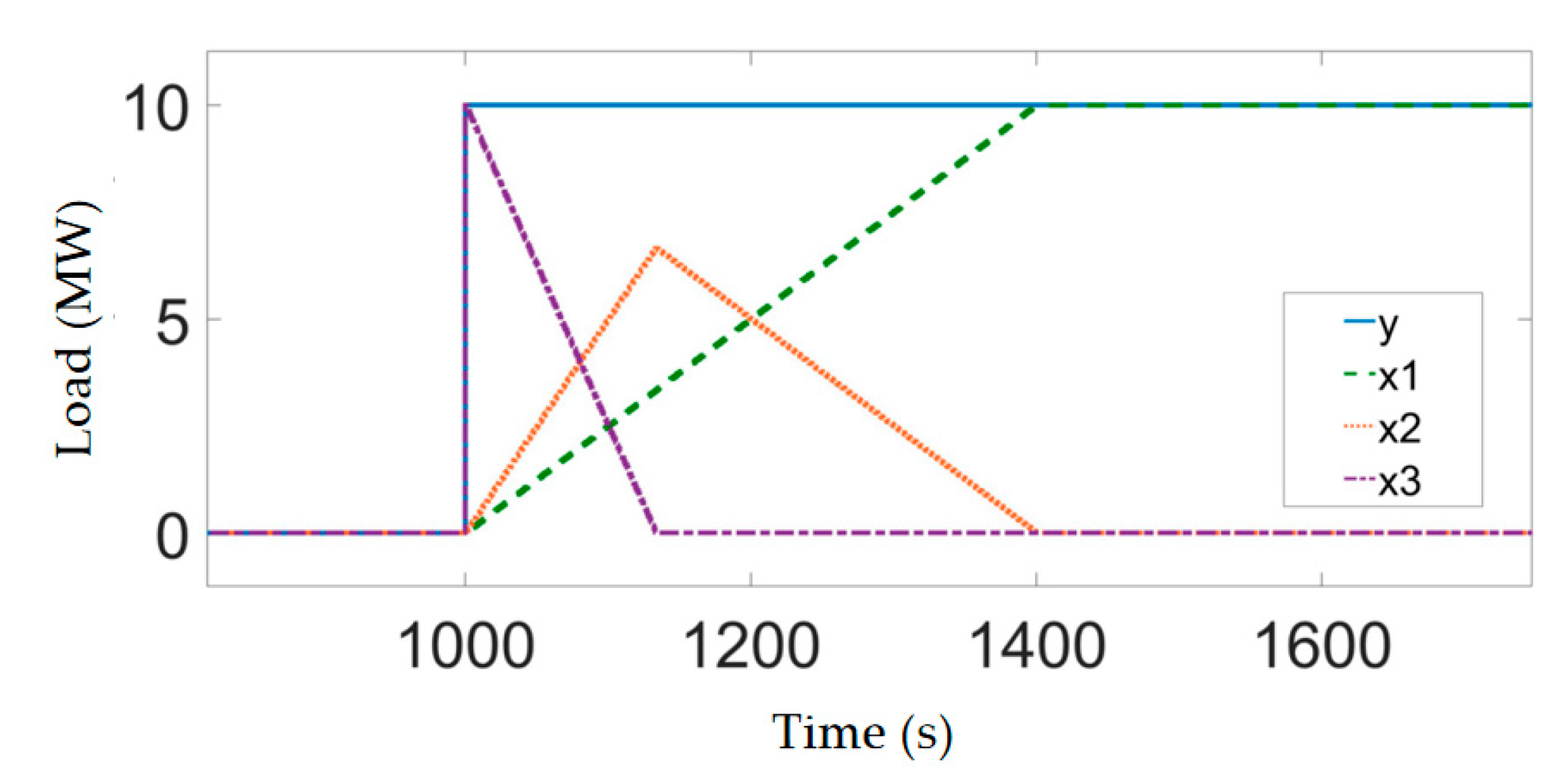

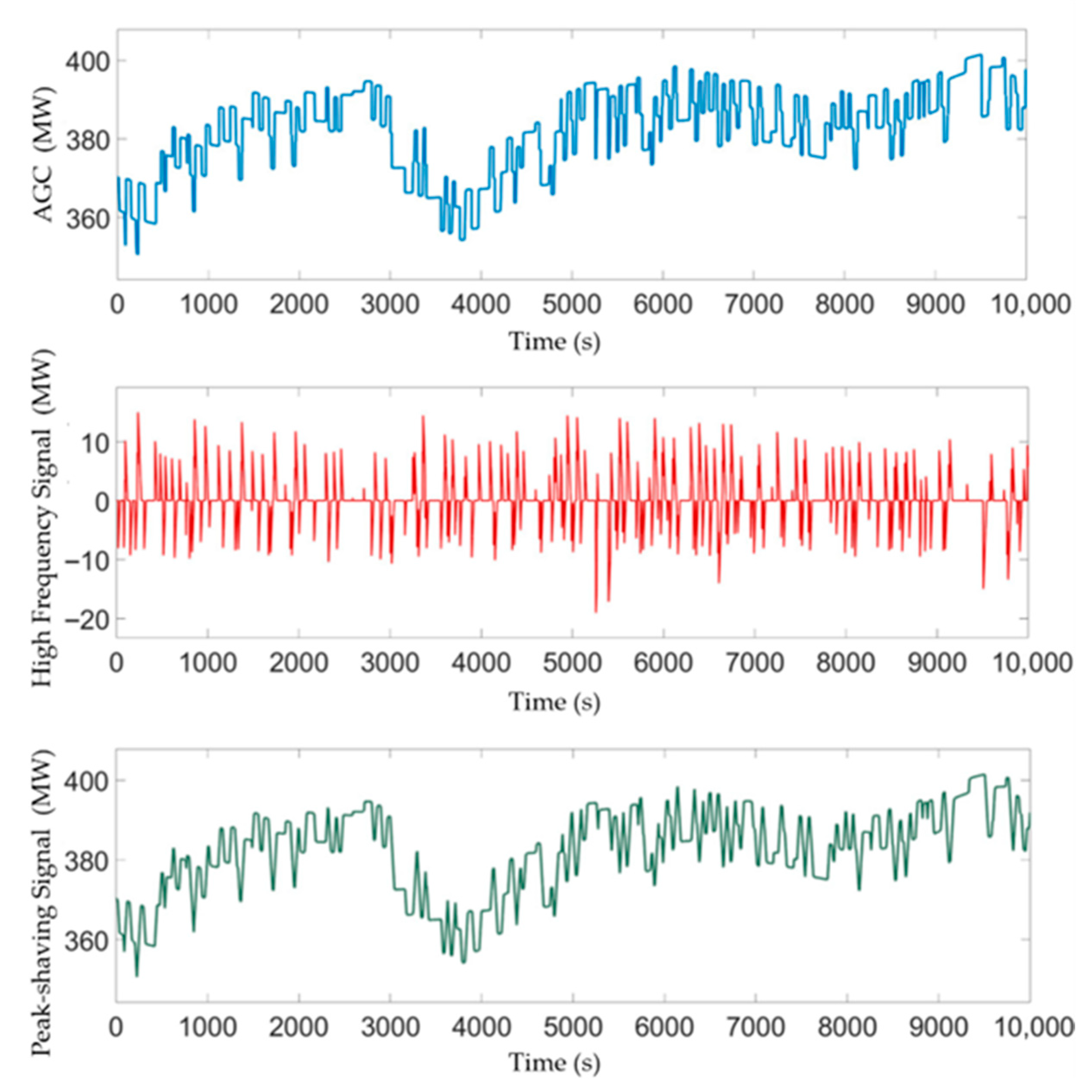

4.2. Signal Generation Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Rate-limiting Decomposition | |

| Input: | AGC instructions, sampling period and rate limiting threshold. |

| Output: | High-frequency signal and peak-shaving signal. |

| Algorithm process: | |

| 1 | Initialization: Set the reference value and the value of the slow-varying component accumulator at the previous moment to 0 |

| 2 | Calculate the change in the reference value so that the change in the reference value is equal to the difference between the AGC reference value at the current moment and that at the previous moment. |

| 3 | Calculate the maximum allowable variation as the product of the rate-limiting threshold and the sampling period |

| 4 | If the absolute value of the change in the reference value is greater than or equal to the maximum allowable change, the change after limiting is the maximum allowable change in the same direction as the change. Otherwise, the change after limiting is equal to the change of the reference value |

| 5 | Let the slow-varying component at the current moment be the sum of the slow-varying component accumulator and the variation after limiting. Then update the slow-varying component accumulator to the slow-varying component at the current moment. |

| 6 | Calculate the fast-varying component at the current moment as the AGC instruction at the current moment minus the slow-varying component at the current moment. |

| 7 | Update the reference value of the previous moment to the AGC reference value of the current moment, and output high-frequency signal and peak-shaving signal in real time. |

4.3. Design of Combined Cycle Frequency Modulation Control System

4.3.1. AGC Command Allocation Mechanism

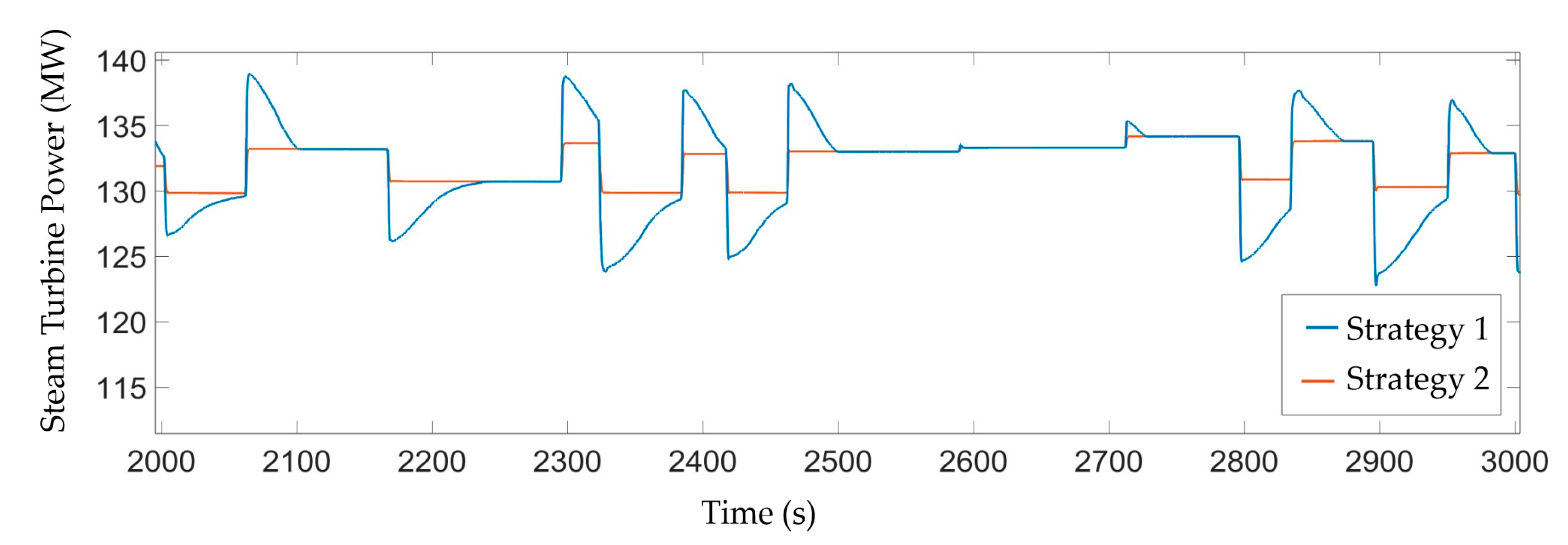

4.3.2. Dynamic Feedforward Compensation on the Steam Turbine Side

4.3.3. Lead Compensation for AGC Error Feedback

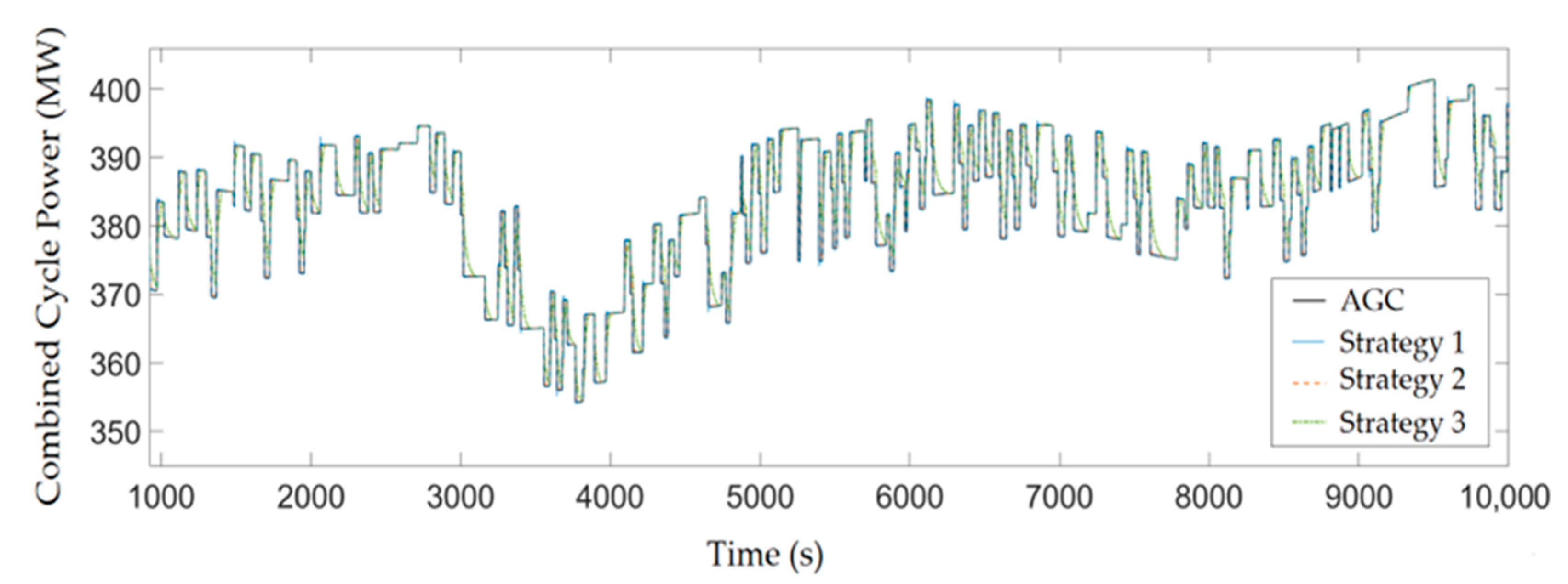

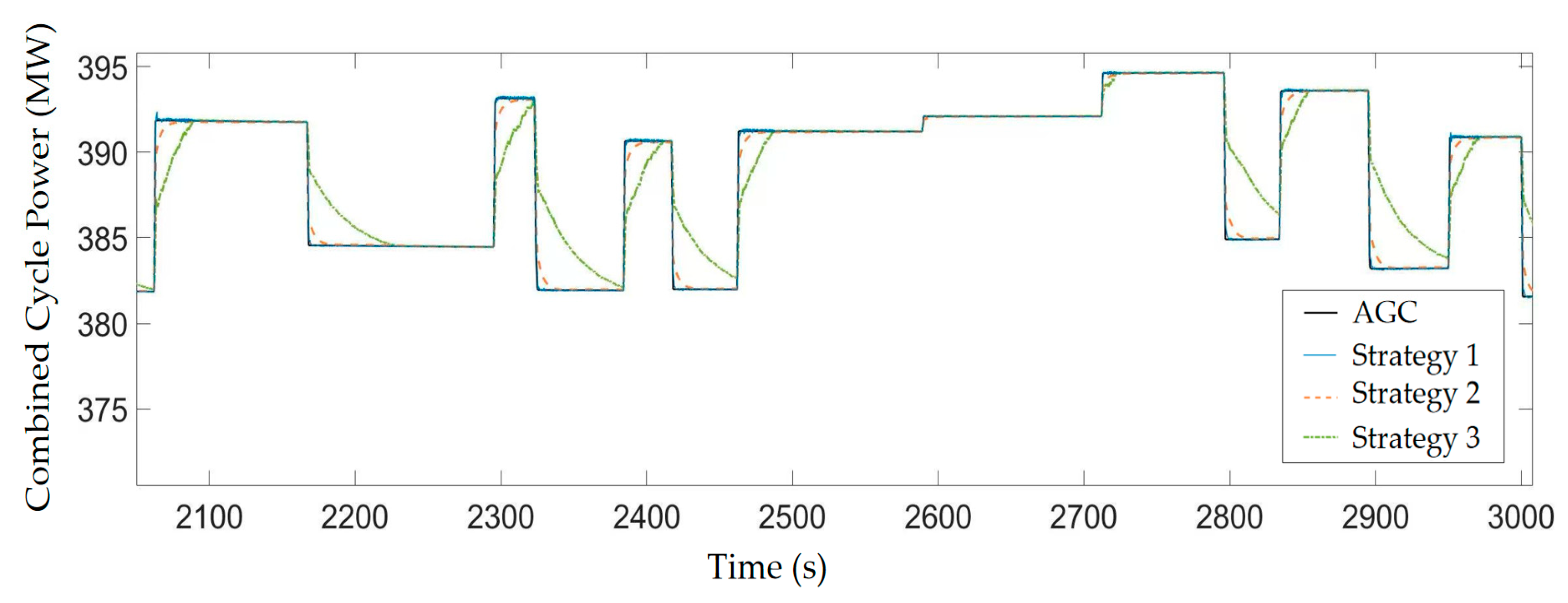

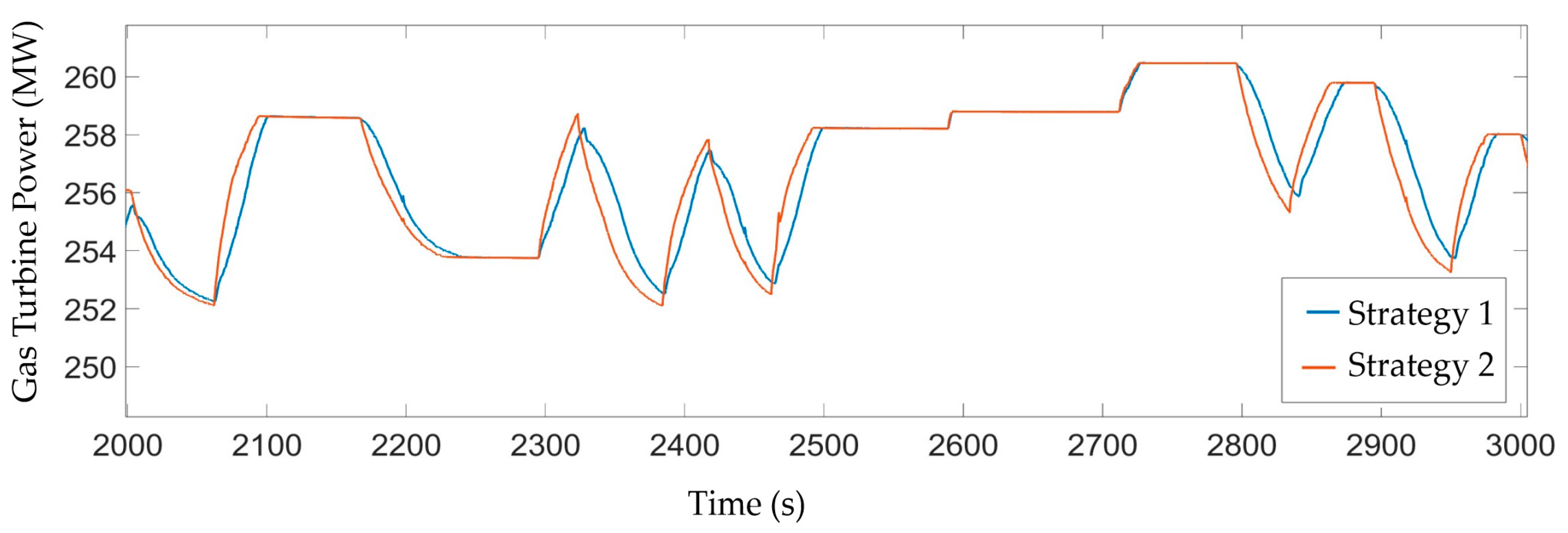

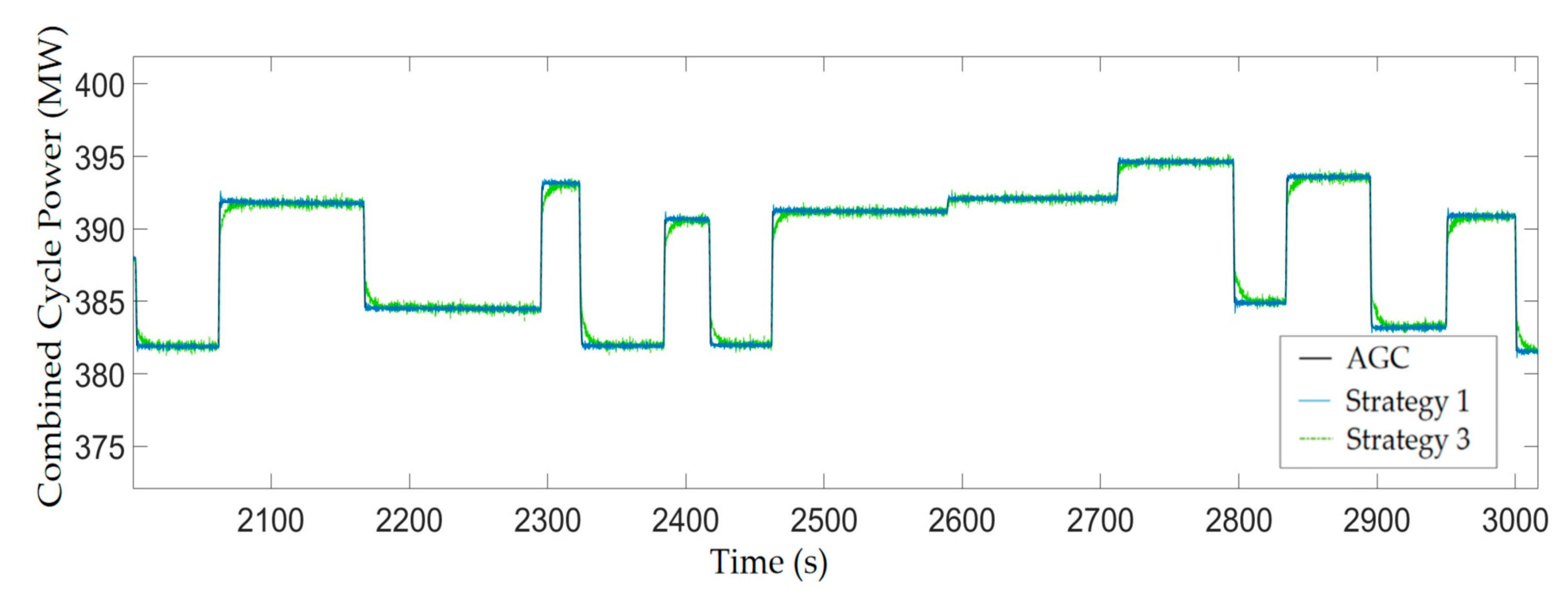

4.4. Control Performance Comparison

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, C.; Liu, H.X.; Wang, P.; Fan, K.L.; Huang, Z.F.; Ma, X.Q. Economic Analysis on Peak-regulation of GTCC Cogeneration Unit with Extraction Heating. CSEE J. Power Energy 2020, 40, 592–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Garcia, A.; Bouffard, F.; Kirschen, D.S. Decentralized Demand-Side Contribution to Primary Frequency Control. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2011, 26, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.H.; Ma, L.Q.; He, J.; Zhao, S.F. Study on Load Characteristics of Multiple Operation Modes of Gas-steam Combined Cycle Cogeneration Unit. CSEE J. Power Energy 2020, 40, 2587–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudu, K.; Igie, U.; Roumeliotis, I.; Hamilton, R. Impact of gas turbine flexibility improvements on combined cycle gas turbine performance. Appl. Therm. Eng. Des. Process. Equip. Econ. 2021, 189, 116703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rúa, J.; Bui, M.; Lars, O.N.; Niall, M.D. Does CCS reduce power generation flexibility? A dynamic study of combined cycles with post-combustion CO2 capture. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2020, 95, 102984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haakana, J.; Tikka, V.; Lassila, J.; Partanen, J. Methodology to analyze combined heat and power plant operation considering electricity reserve market opportunities. Energy 2017, 127, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.C.; Li, X.D.; Luo, X.; Chen, Y.P.; Wang, B.Y.; Lai, F.; Cao, X.; Chu, G.H.; Chai, S.K.; Wu, T.; et al. Performance analysis and diagnosis system of gas-steam combined cycle unit based on big data. Therm. Power Gener. 2020, 49, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Cao, Y.; Dai, Y.P. Mathematical Modeling and Dynamic Simulation Study Based on 300MW Heavy-Duty Gas Turbine. Gas Turbine Technol. 2016, 29, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.M.; Zhang, Z.J.; Lin, Y.; Wu, Y.L. Research of fuzzy control of the fuel pressure system for micro gas turbine. Microcomput. Its Appl. 2012, 31, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Saikia, L.C. Automatic generation control of an interconnected CCGT-thermal system using stochastic fractal search optimized classical controllers. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2018, 28, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Y.; Saikia, L.C. Automatic generation control of a multi-area ST—Thermal power system using Grey Wolf Optimizer algorithm based classical controllers. Int. J. Electr. Power 2015, 73, 853–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, B. Multiple model based predictive control for single shaft gas turbine. Gas Turbine Technol. 2009, 22, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Pan, L.; Pedersen, S.; Arabkoohsar, A. A two-dimensional design and synthesis method for coordinated control of flexible-operational combined cycle of gas turbine. Energy 2023, 284, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, V.H.; Fekih, A.; Monje, C.A.; Asfestani, R.F. Adaptive model predictive control design for the speed and temperature control of a V94.2 gas turbine unit in a combined cycle power plant. Energy 2020, 207, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, T.S.; Cruz, M.E.; Colaco, M.J.; Alves, M.A.C. Application of nonlinear multivariable model predictive control to transient operation of a gas turbine and NO X emissions reduction. Energy 2018, 149, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Pan, L.; Arabkoohsar, A.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Pedersen, S. Power-heat conversion coordinated control of combined-cycle gas turbine with thermal energy storage in district heating network. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 220, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, T.Y. Characteristic Analysis on Energy Storage and Control Methods of Rapid Load Change for Heat Supply Units. Ph.D. Thesis, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Parameters | On-Site Data | Simulation Data | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outlet pressure of the compressor (MPa) | 1.97 | 1.904 | −3.35 |

| Compressor outlet temperature (K) | 699.28 | 702.05 | 0.65 |

| Turbine outlet temperature (K) | 835.67 | 844.5 | 1.06 |

| GT power (MW) | 296.6 | 283.7 | −4.35 |

| ST power (MW) | 149.2 | 146.5 | −1.81 |

| Parameters | On-Site Data | Simulation Data | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outlet pressure of the compressor (MPa) | 1.51 | 1.581 | 4.7 |

| Compressor outlet temperature (K) | 649.18 | 652.75 | 0.55 |

| Turbine outlet temperature (K) | 824 | 854.6 | 3.71 |

| GT power (MW) | 199.56 | 200.3 | 0.37 |

| ST power (MW) | 100.8 | 101.5 | 0.69 |

| Parameters | On-Site Data | Simulation Data | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outlet pressure of the compressor (MPa) | 1.9 | 1.9 | 0 |

| Compressor outlet temperature (K) | 712.45 | 719.4 | 0.98 |

| Turbine outlet temperature (K) | 848.53 | 853.9 | 0.63 |

| GT power (MW) | 281.16 | 277 | −1.48 |

| ST power (MW) | 141.8 | 139.5 | −1.62 |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Fuel flow rate (kg/s) | 19.44 |

| IGV Opening (%) | 80 |

| Main Steam Valve Opening (%) | 40 |

| CCGT Power (MW) | 387.2 |

| Gas Turbine Power (MW) | 258.2 |

| Steam Turbine Power (MW) | 129 |

| Flue Gas Temperature (K) | 810.96 |

| Total Powers of CCGT (MW) | GT Power (MW) | ST Power (MW) |

|---|---|---|

| 303.5 | 205 | 98.5 |

| 334.6 | 224.8 | 109.8 |

| 366 | 244.8 | 121.2 |

| 376.8 | 251.8 | 125 |

| 391.8 | 260.8 | 131 |

| Rising Time (s) | Overshoot (%) | Steady-State Deviation (%) | IAE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy 1 | 0.7 | 0.027 | 0.00 | 786.6 |

| Strategy 2 | 21.8 | 0.015 | 0.005 | 15,090 |

| Strategy 3 | 15.2 | 0 | −0.005 | 2689 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Xiao, X.; Sun, L.; Pan, L. Improved Coordinated Control Strategy for Auxiliary Frequency Regulation of Gas-Steam Combined Cycle Units. Energies 2025, 18, 5997. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225997

Hu Z, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Xiao X, Sun L, Pan L. Improved Coordinated Control Strategy for Auxiliary Frequency Regulation of Gas-Steam Combined Cycle Units. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5997. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225997

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Zunmin, Yilin Zhang, Tianhai Zhang, Xinyu Xiao, Li Sun, and Lei Pan. 2025. "Improved Coordinated Control Strategy for Auxiliary Frequency Regulation of Gas-Steam Combined Cycle Units" Energies 18, no. 22: 5997. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225997

APA StyleHu, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhang, T., Xiao, X., Sun, L., & Pan, L. (2025). Improved Coordinated Control Strategy for Auxiliary Frequency Regulation of Gas-Steam Combined Cycle Units. Energies, 18(22), 5997. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225997