Thermal Performance Assessment of Heat Storage Unit by Investigating Different Fins Configurations

Abstract

1. Introduction

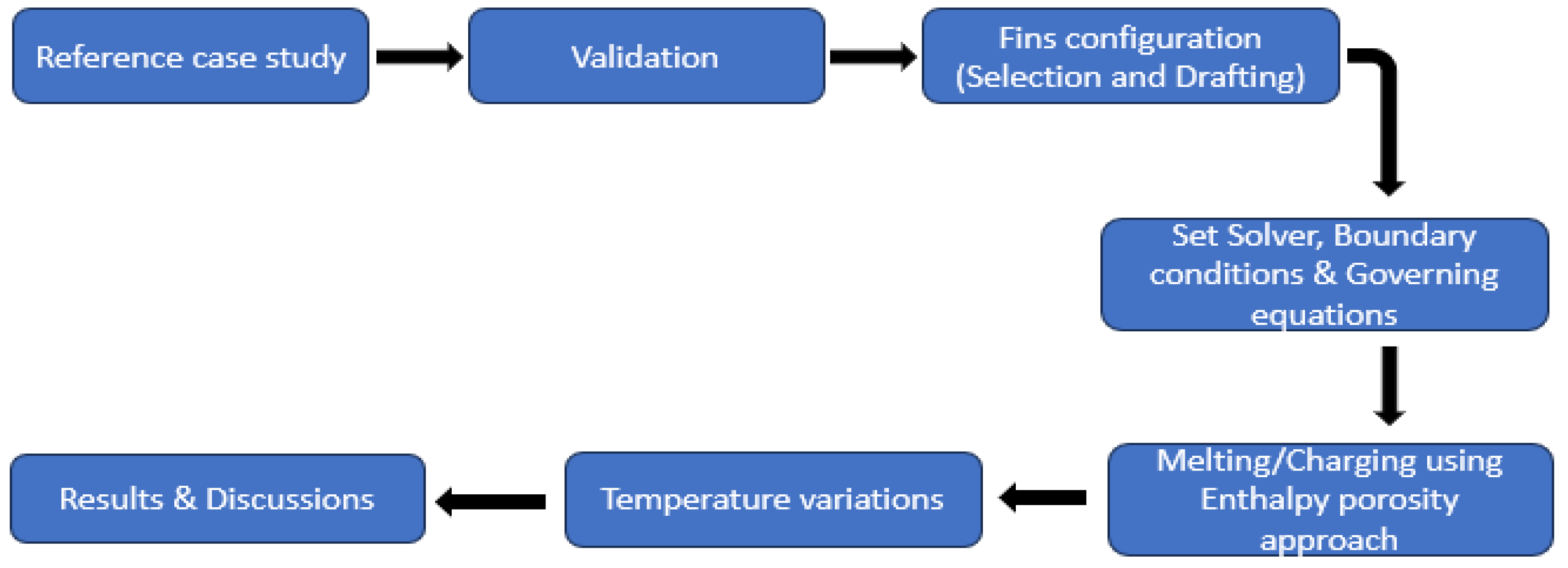

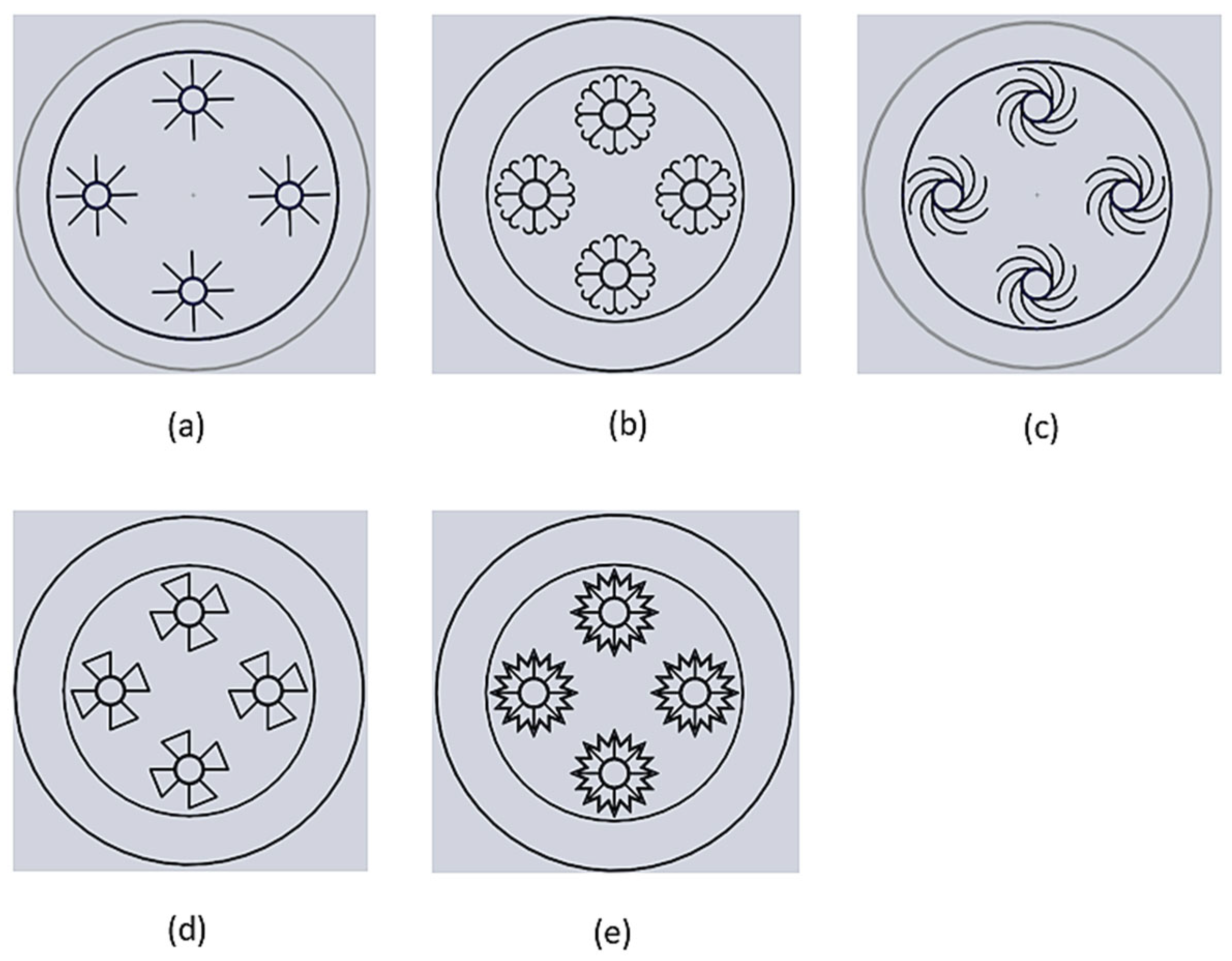

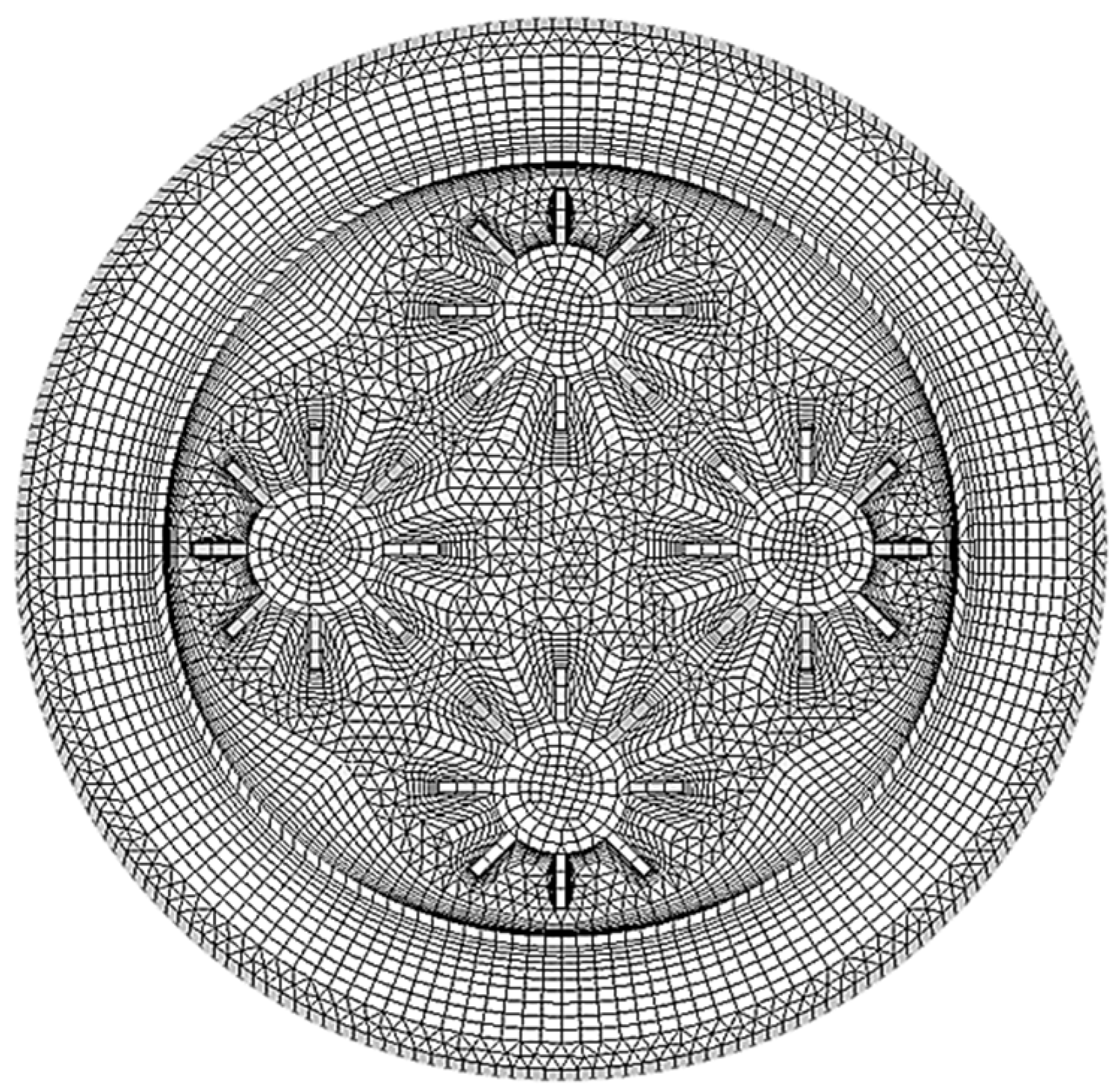

2. Materials and Methods

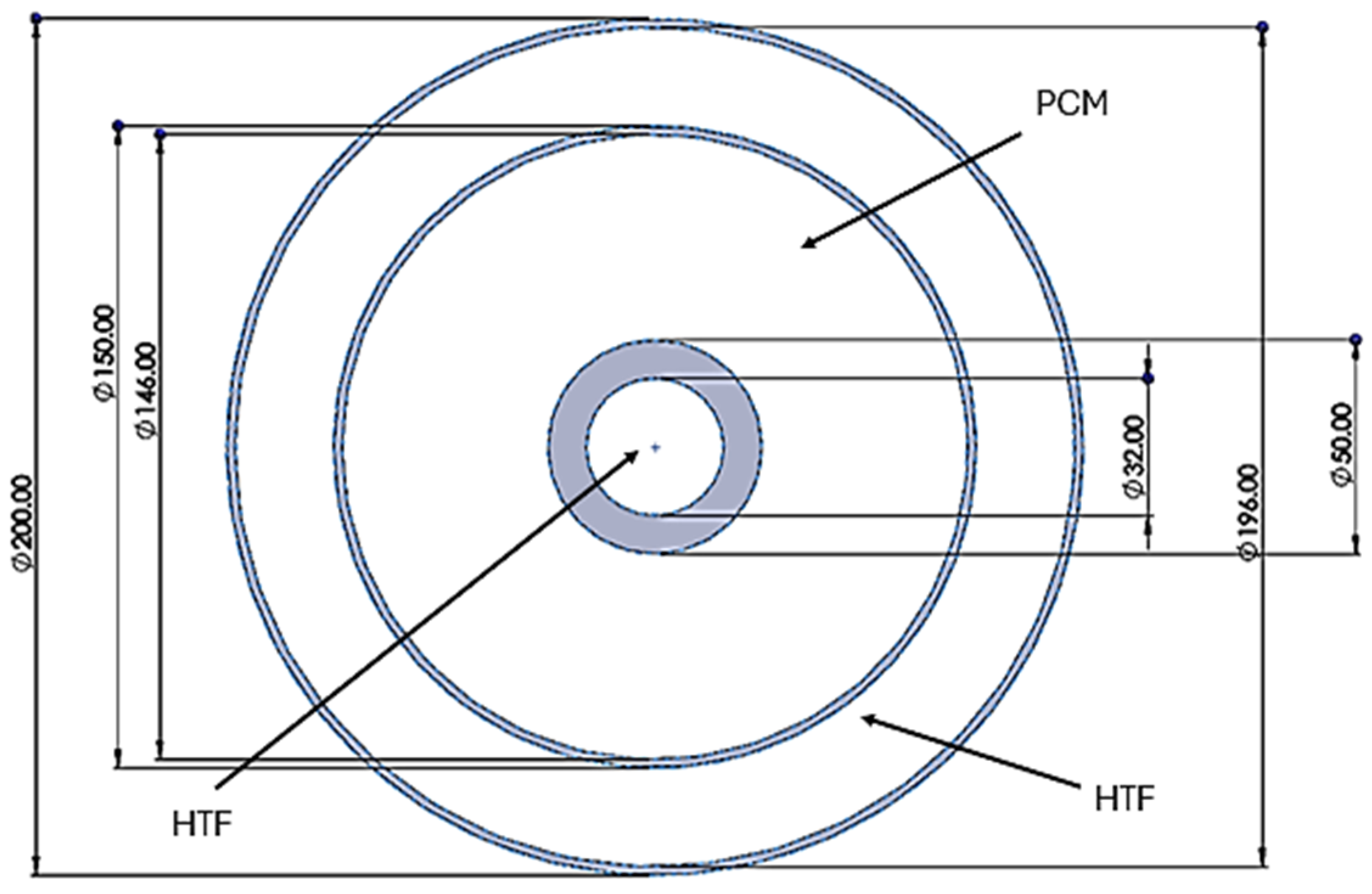

2.1. Geometric Configuration

2.2. Boundary Conditions

- Internal heating of HTF pipe:

- External heating of HTF pipe:

- Internal and external heating:

- Initial temperature:

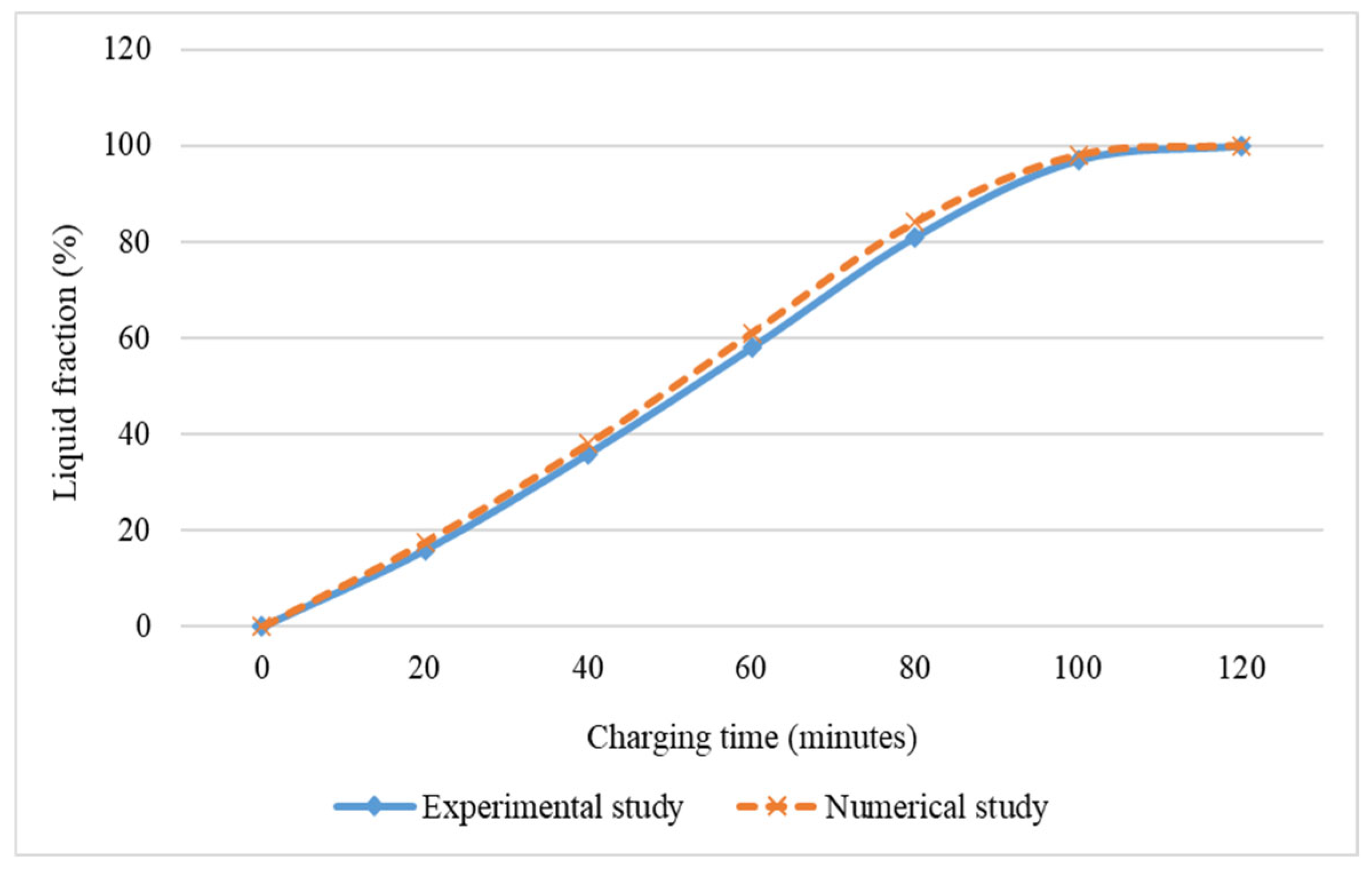

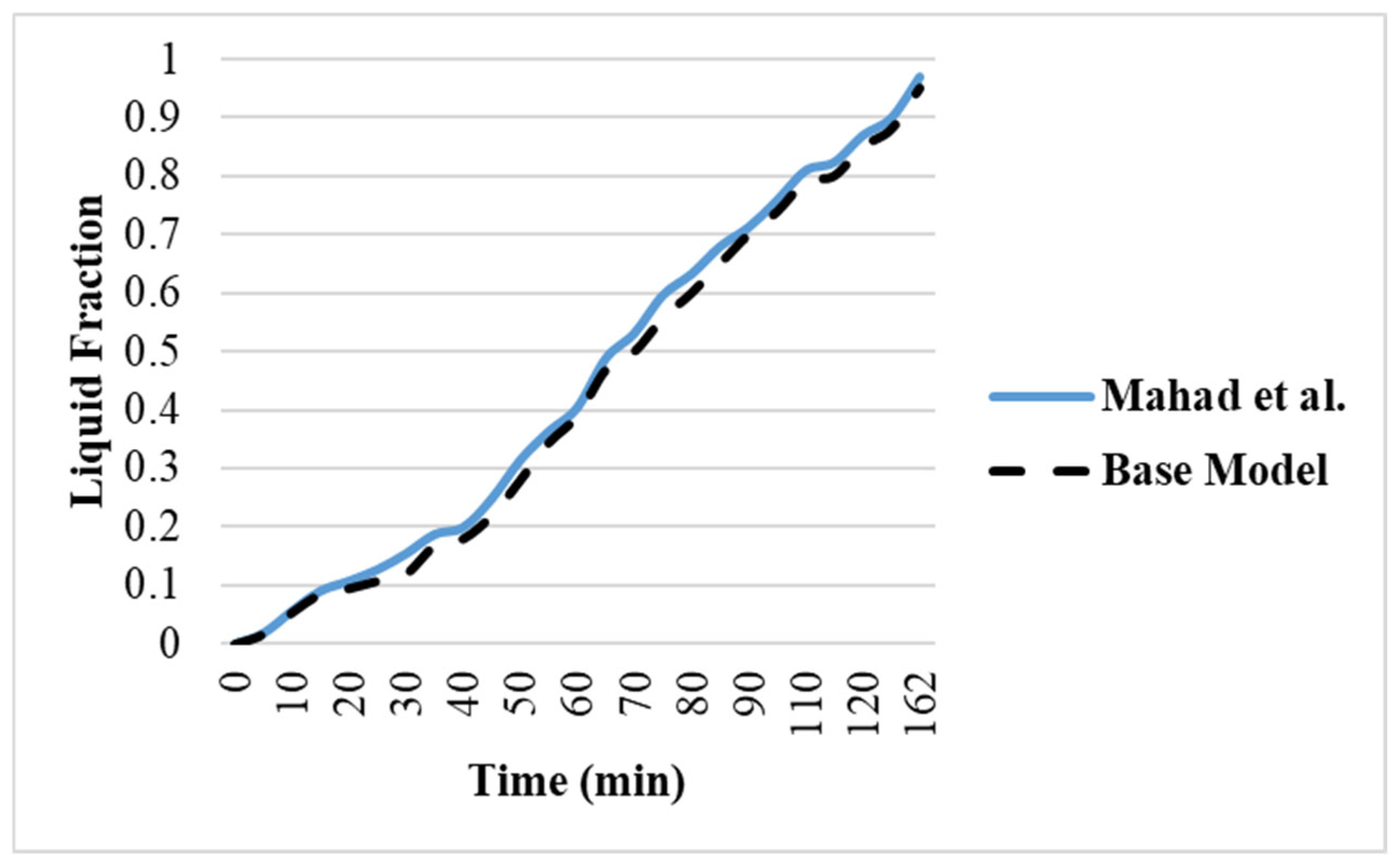

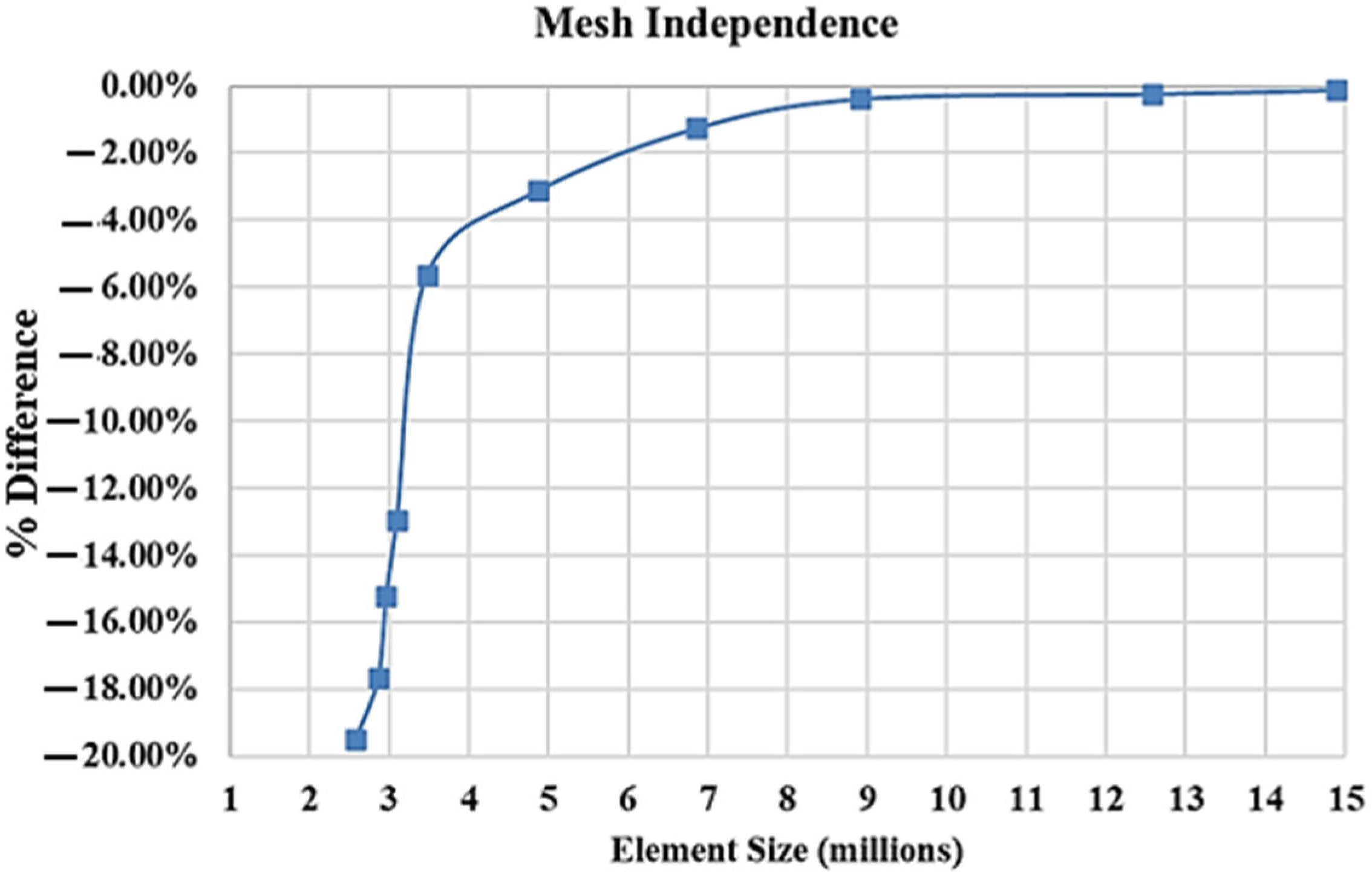

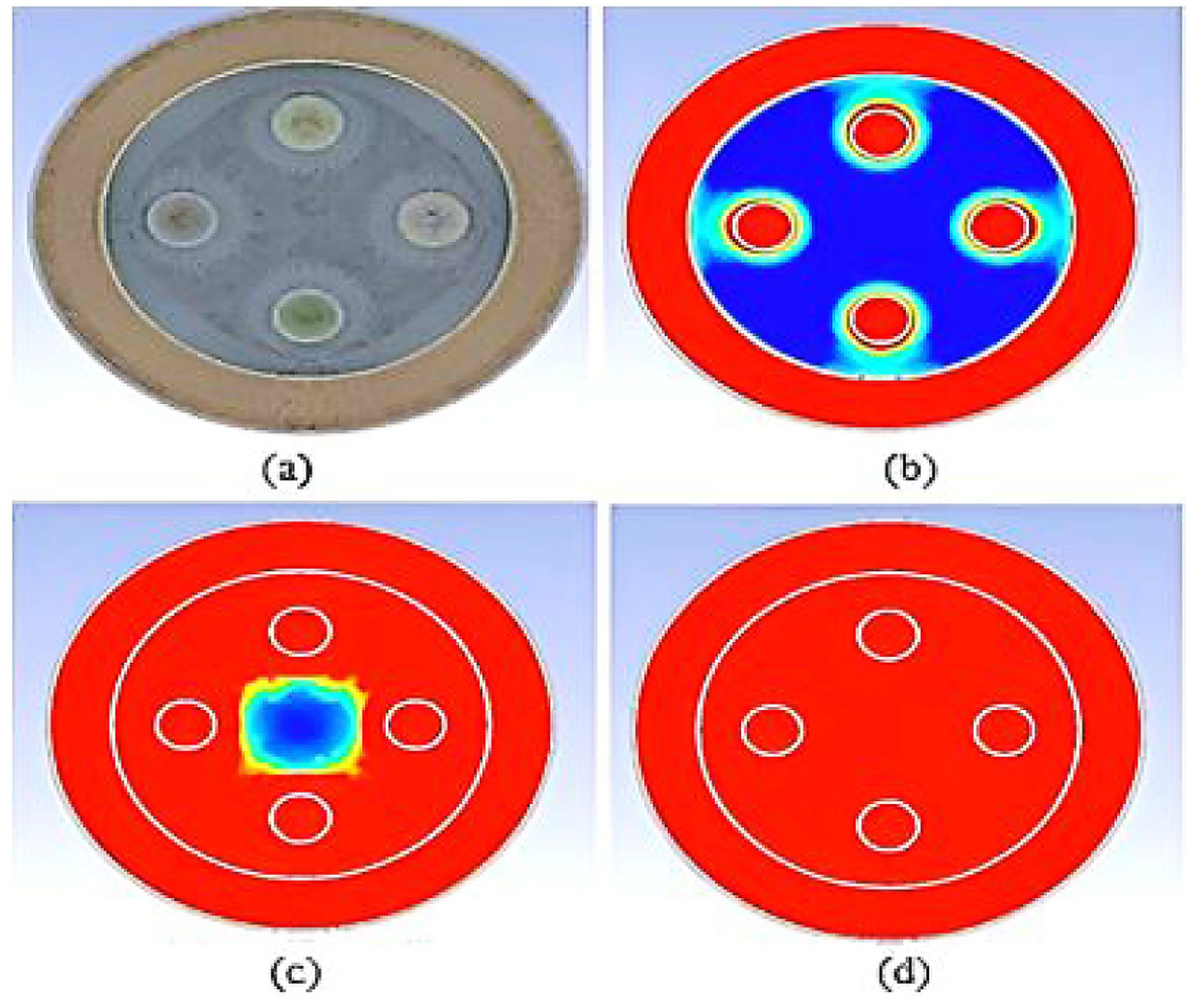

2.3. Validation of Current Study with Experimental and Numerical Studies

2.4. Governing Equations

- i.

- Laminar flow approach

- ii.

- Navier–Stokes and thermal energy equations are recommended for incompressible viscous flow and heat dissipation in circular area due to very low value of viscous dissipation

- iii.

- Incompressible and unsteady flow

- iv.

- Pressure drops assumed to be negligible because of no resistance offered to HTF flow as pipe internal area is free from any obstacles

- v.

- Boussinesq approximation for melting due to convection (natural). This approximation is expressed as Equation (8).

- ➢

- Continuity Equation:

- ➢

- Momentum Equation:

- ➢

- Equation (12) is used as the energy equation:

3. Results

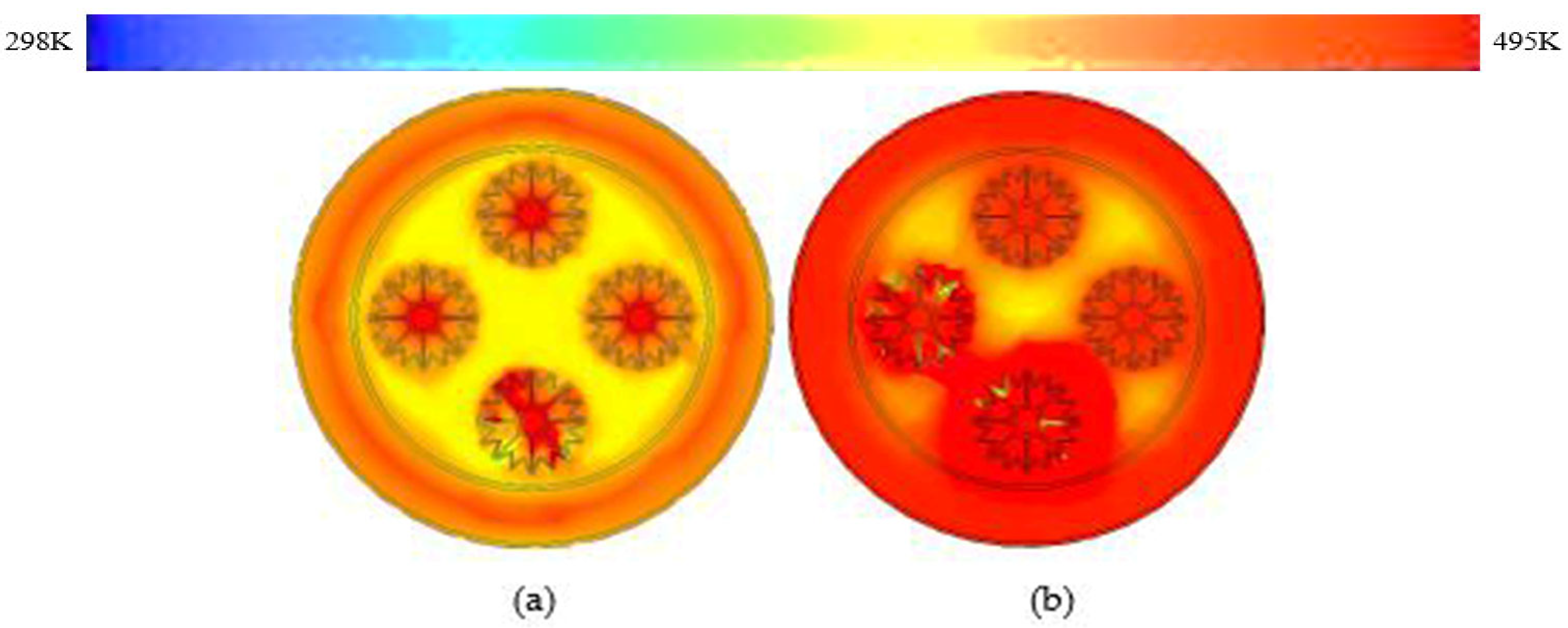

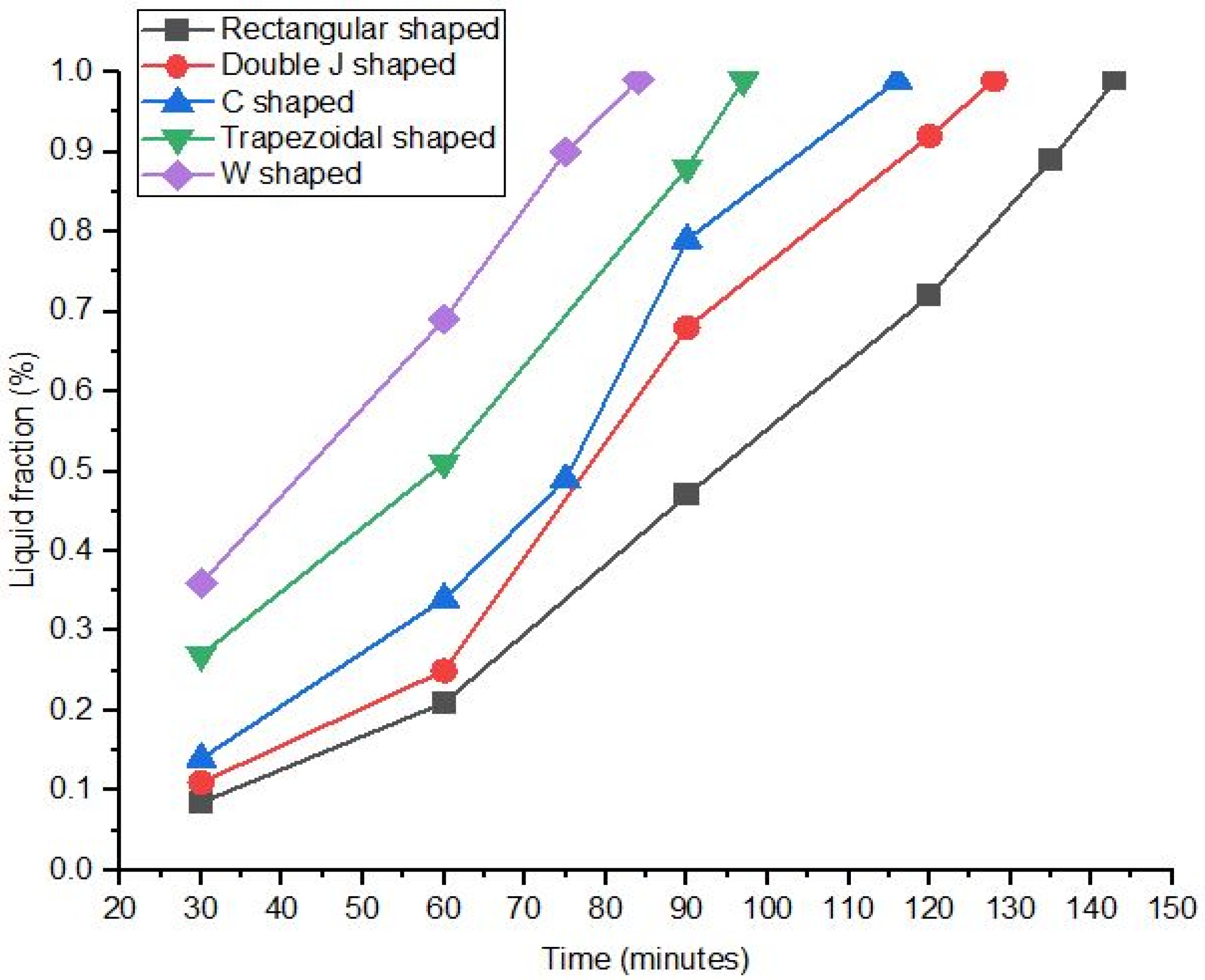

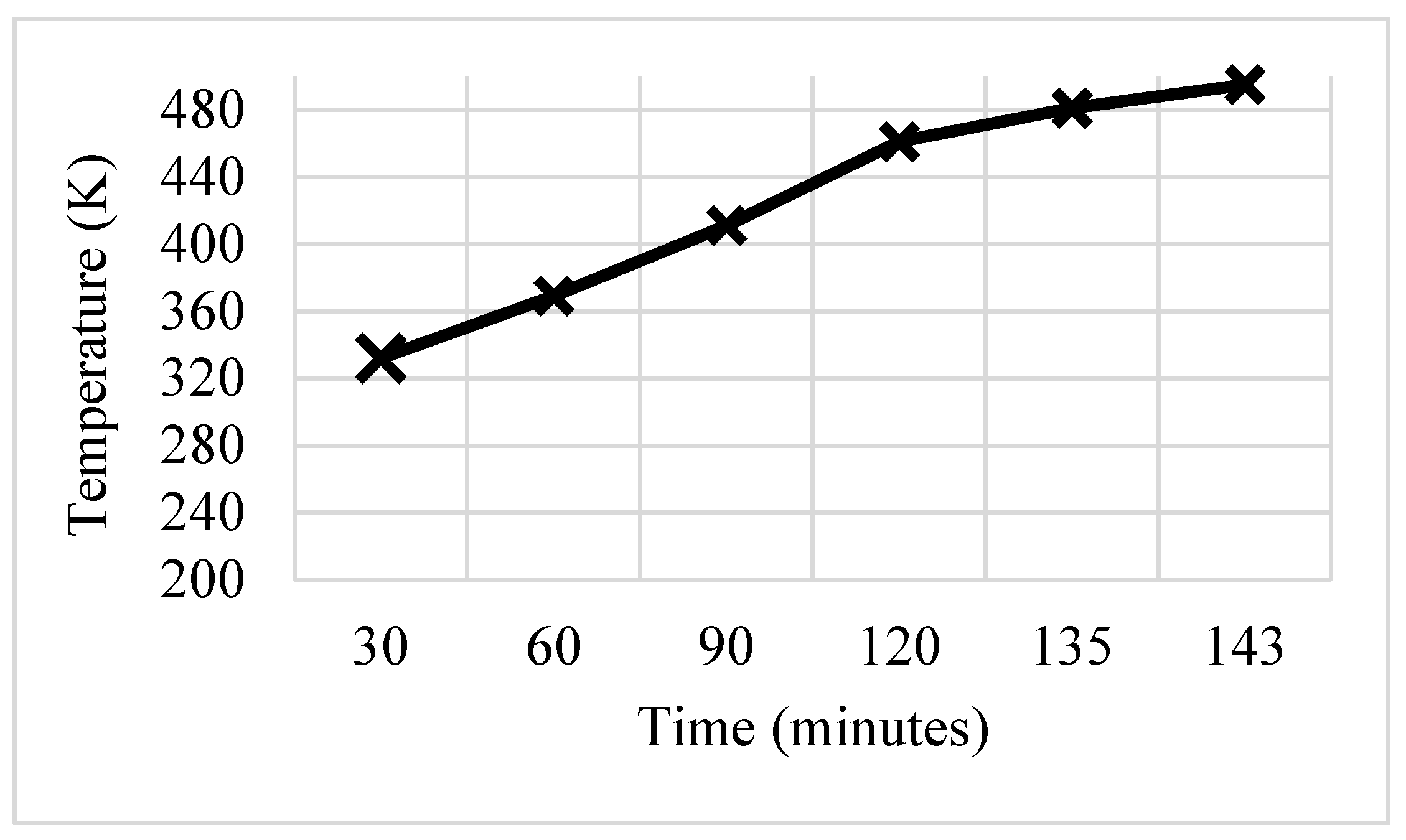

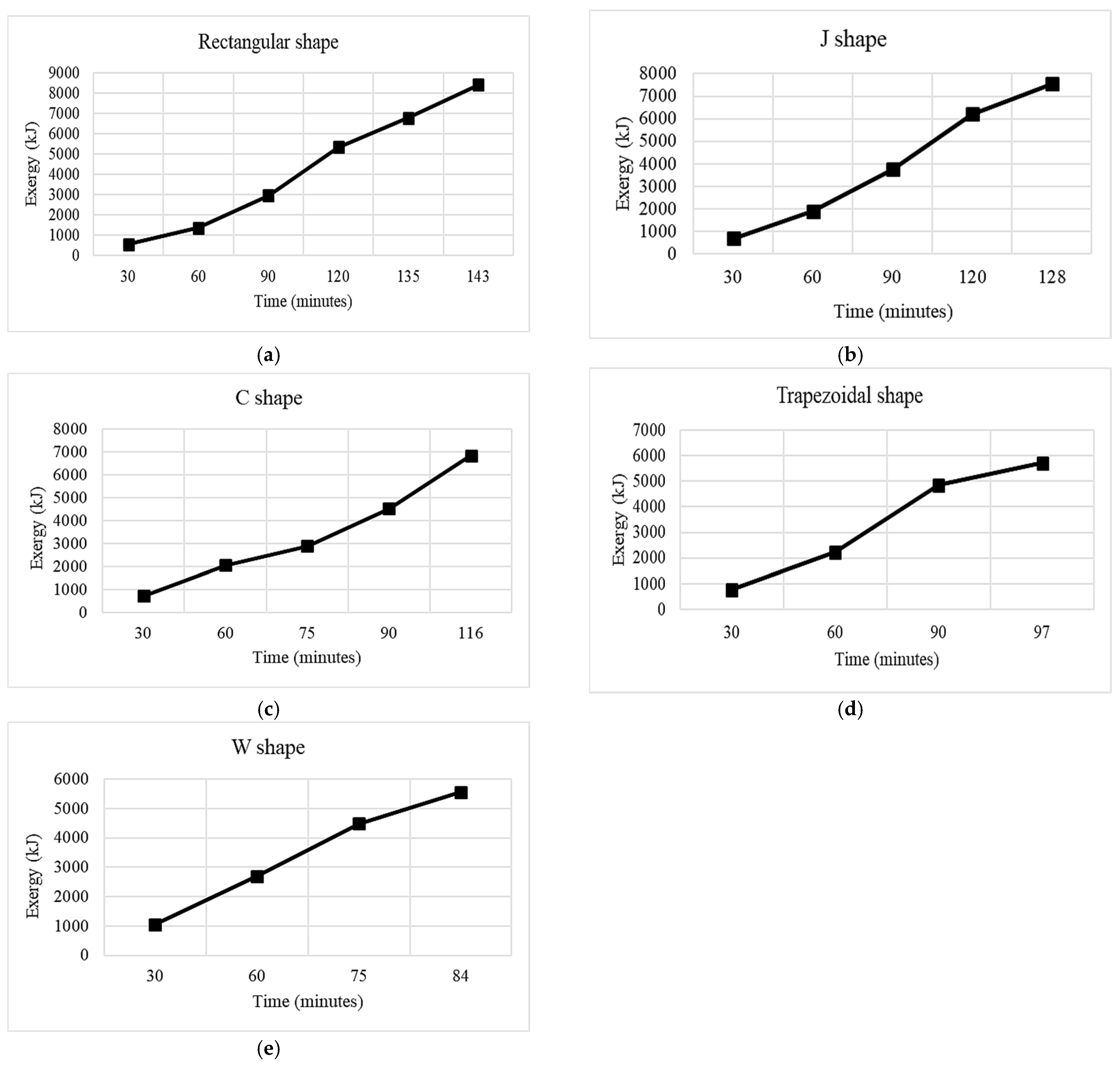

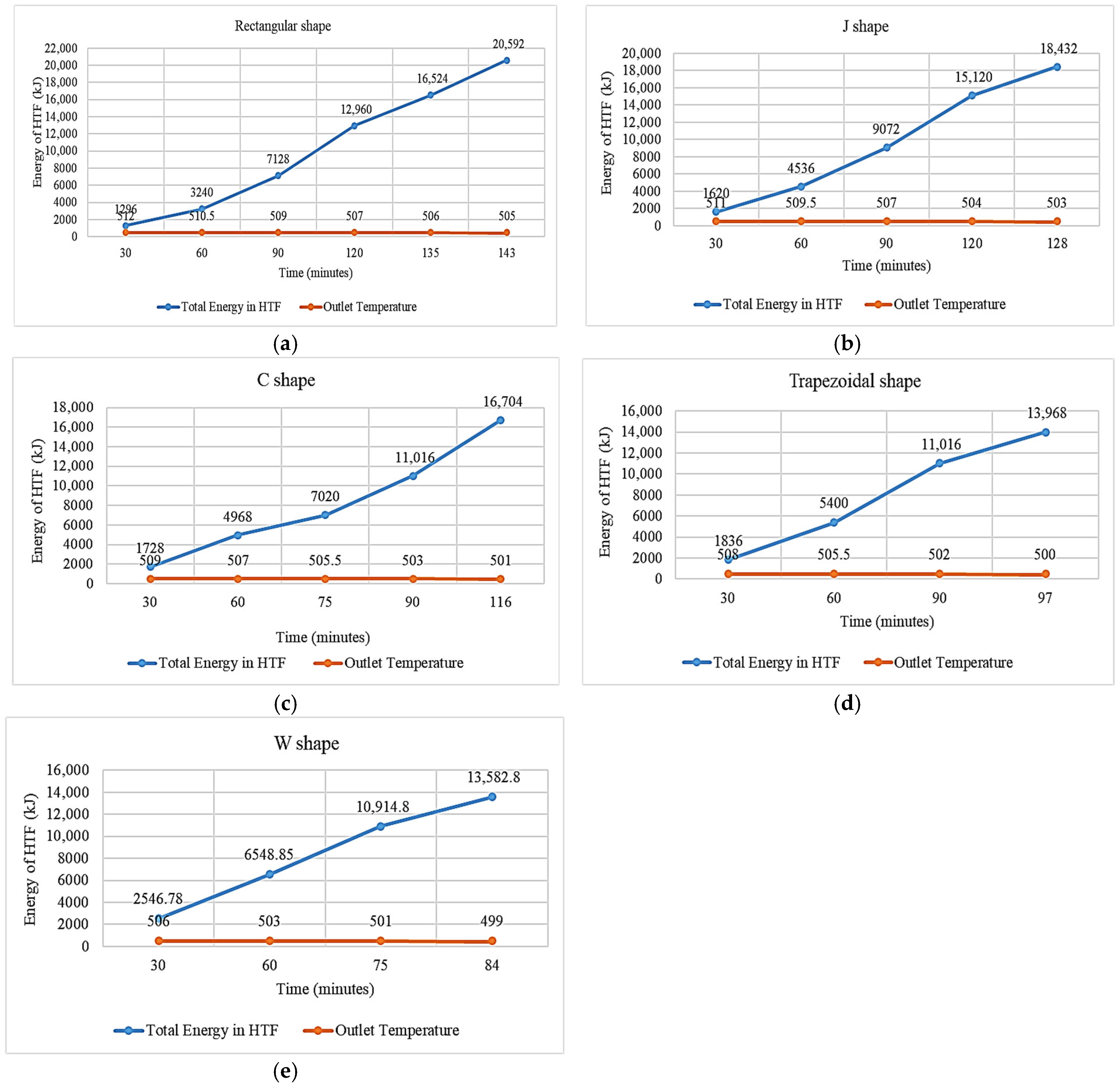

3.1. Rectangular Fins

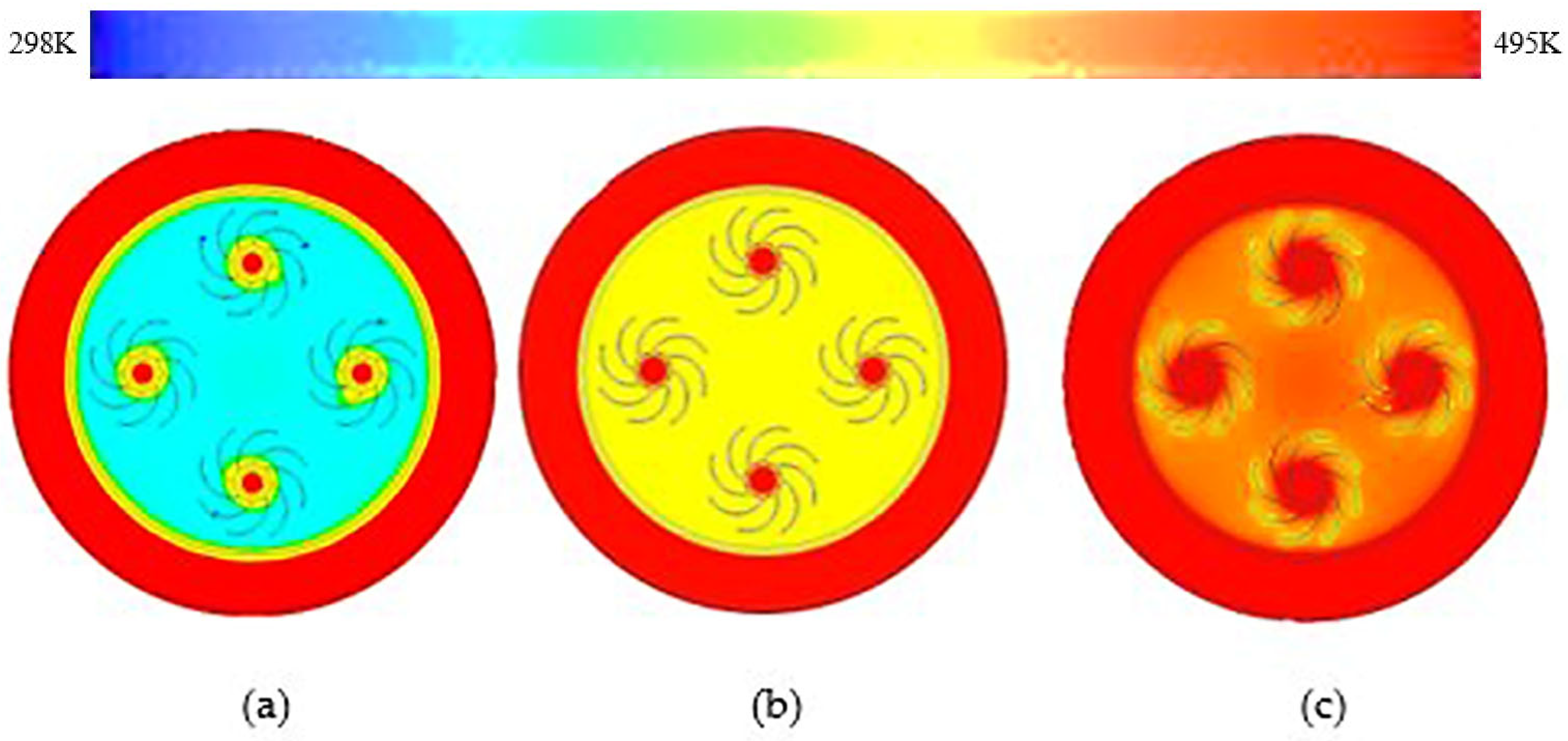

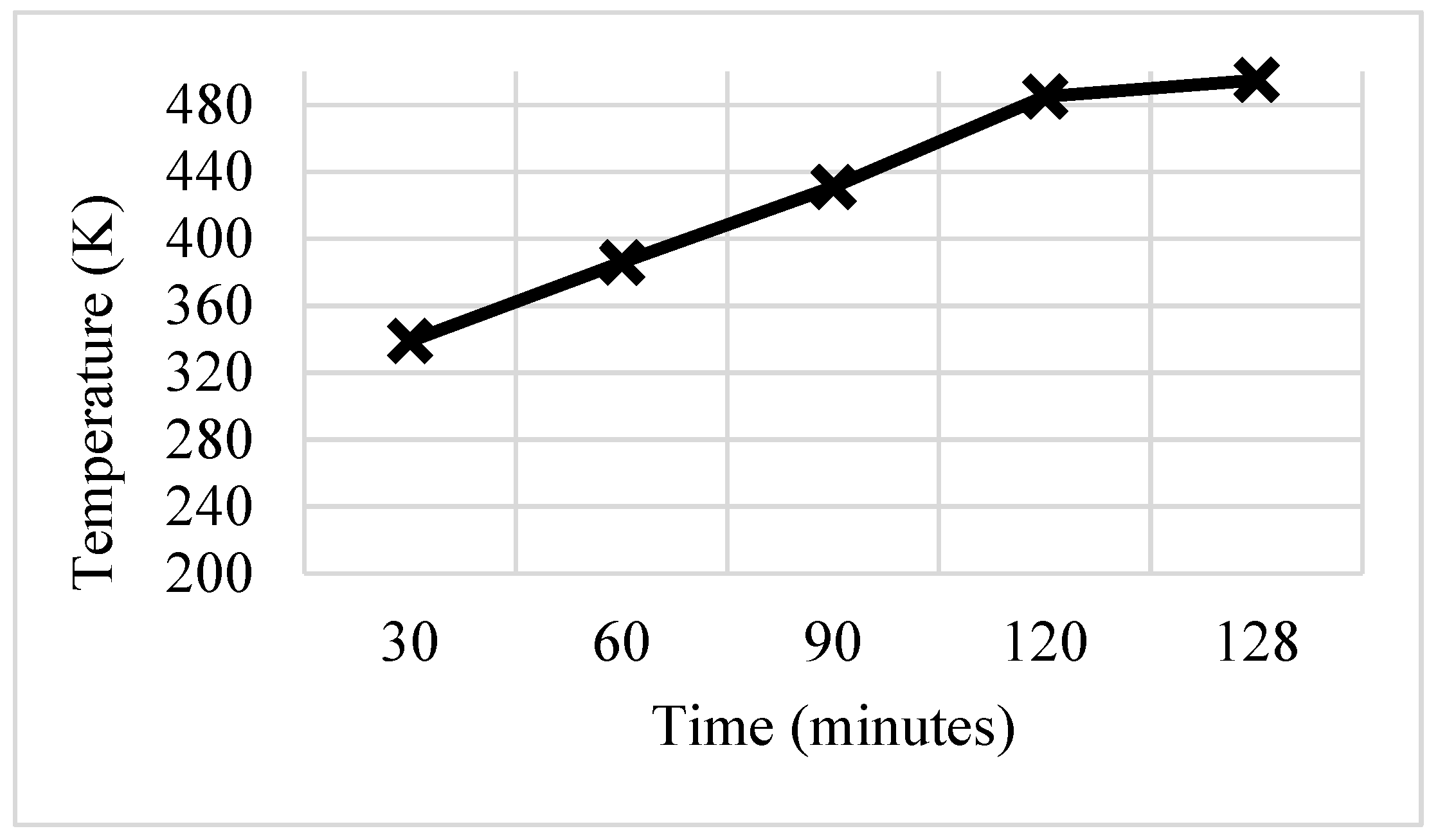

3.2. Double J-Shaped Fins

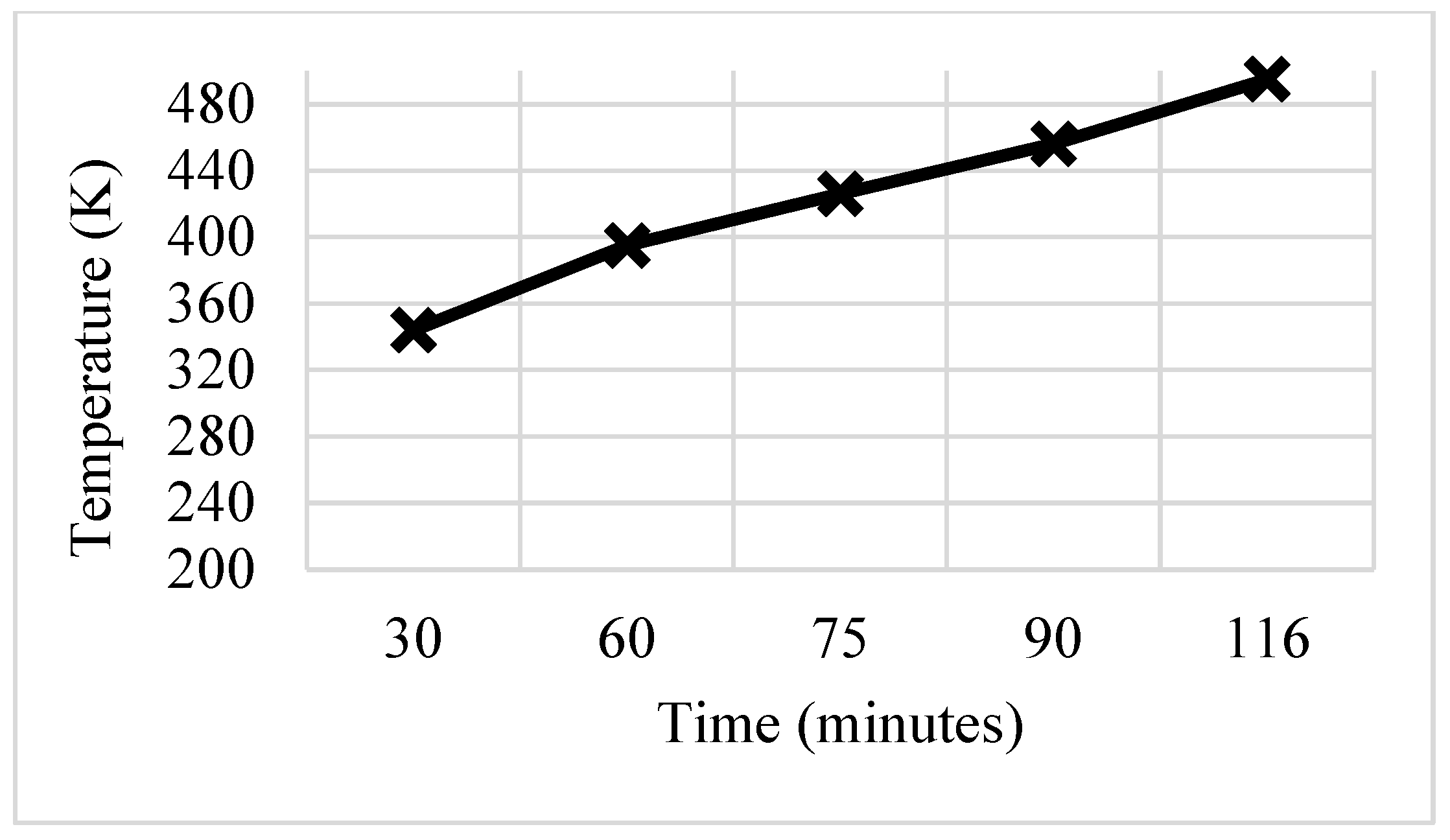

3.3. C-Shaped Fins

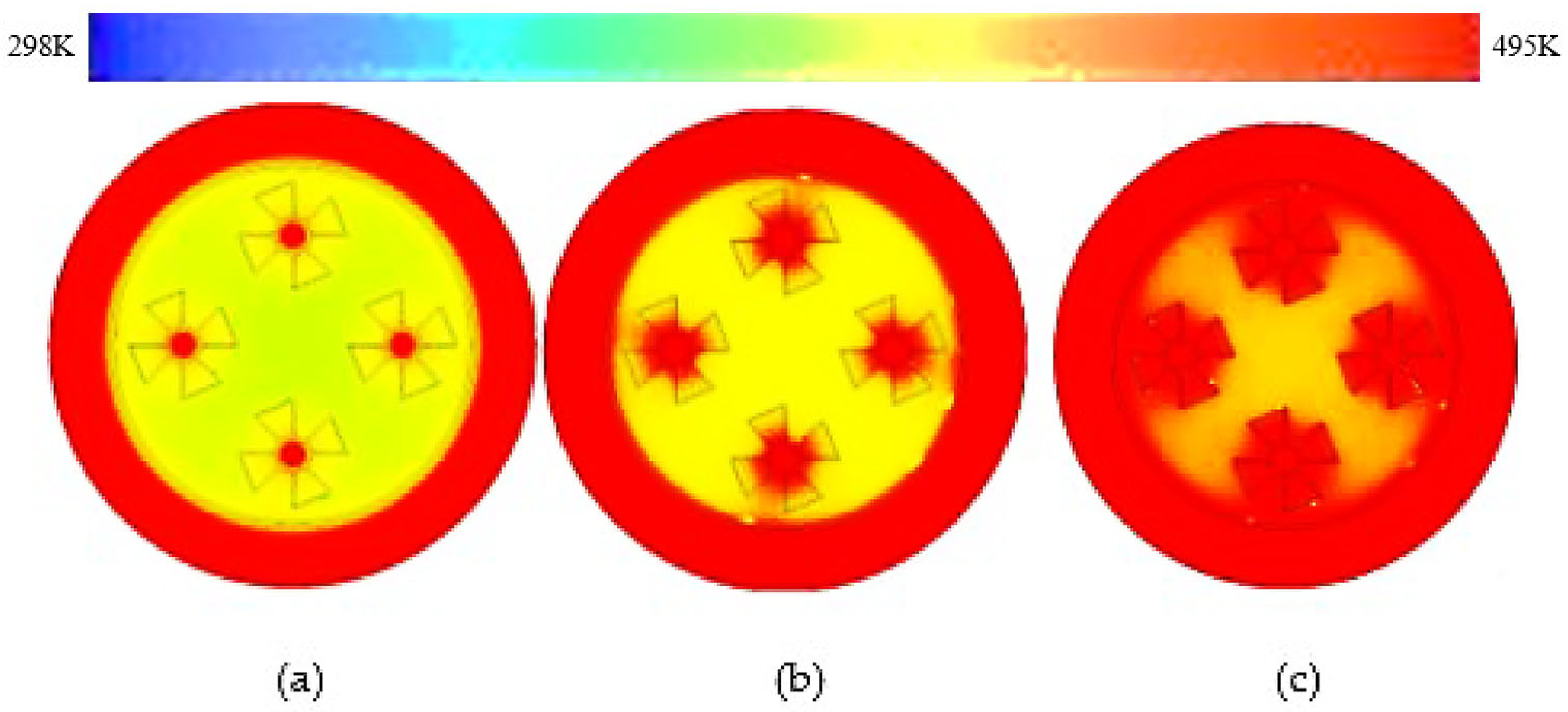

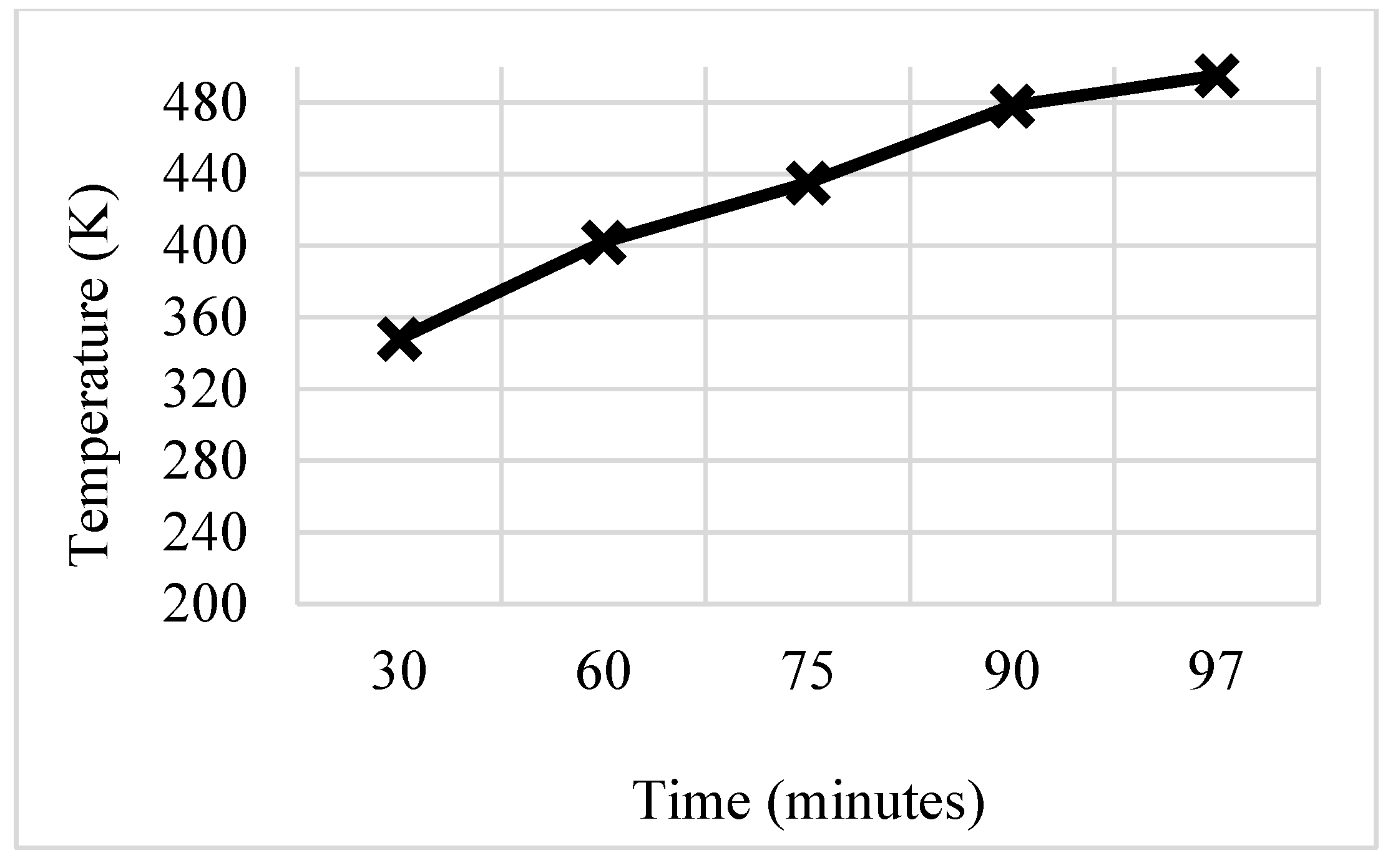

3.4. Trapezoidal Fin

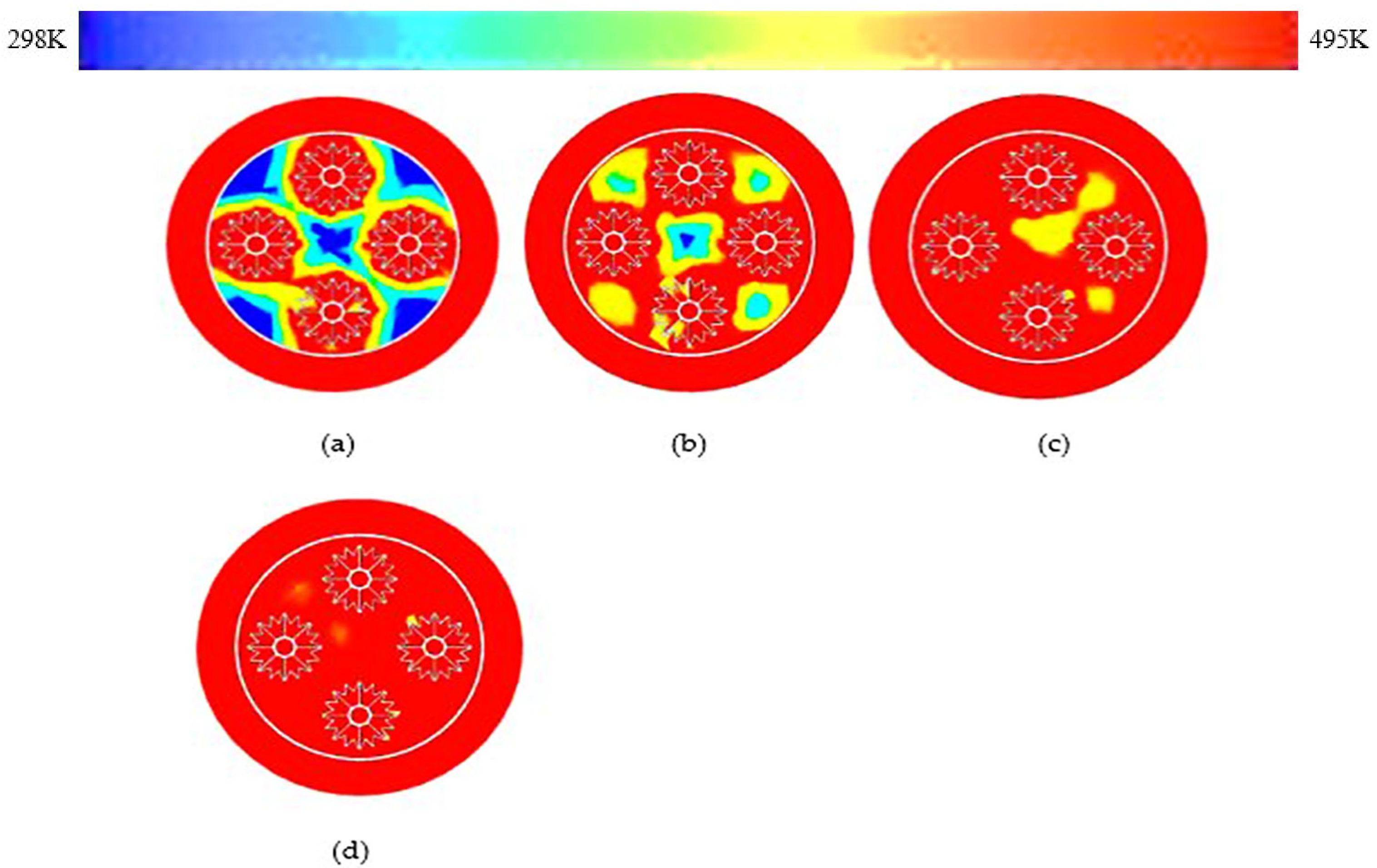

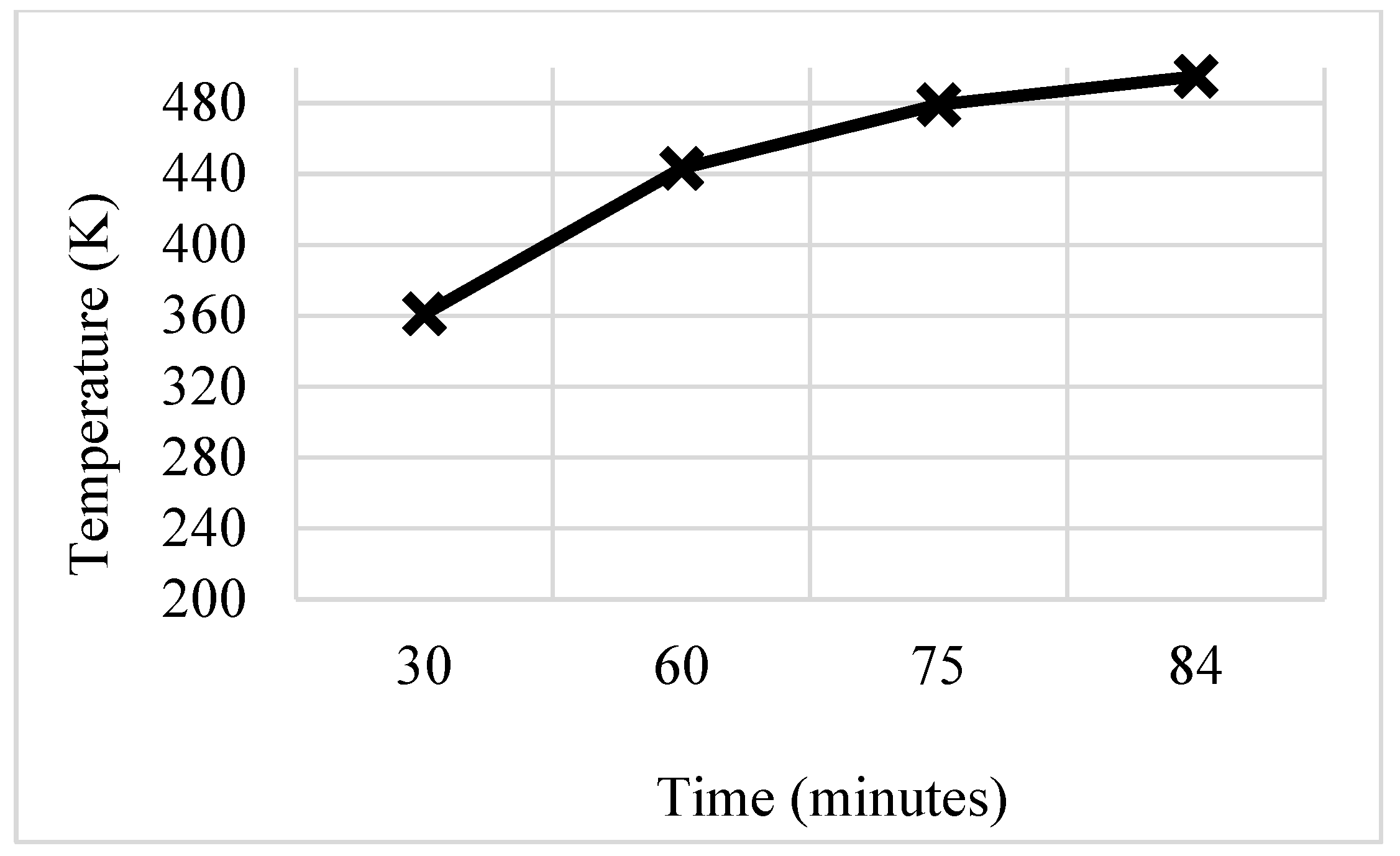

3.5. W-Shaped Fin

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

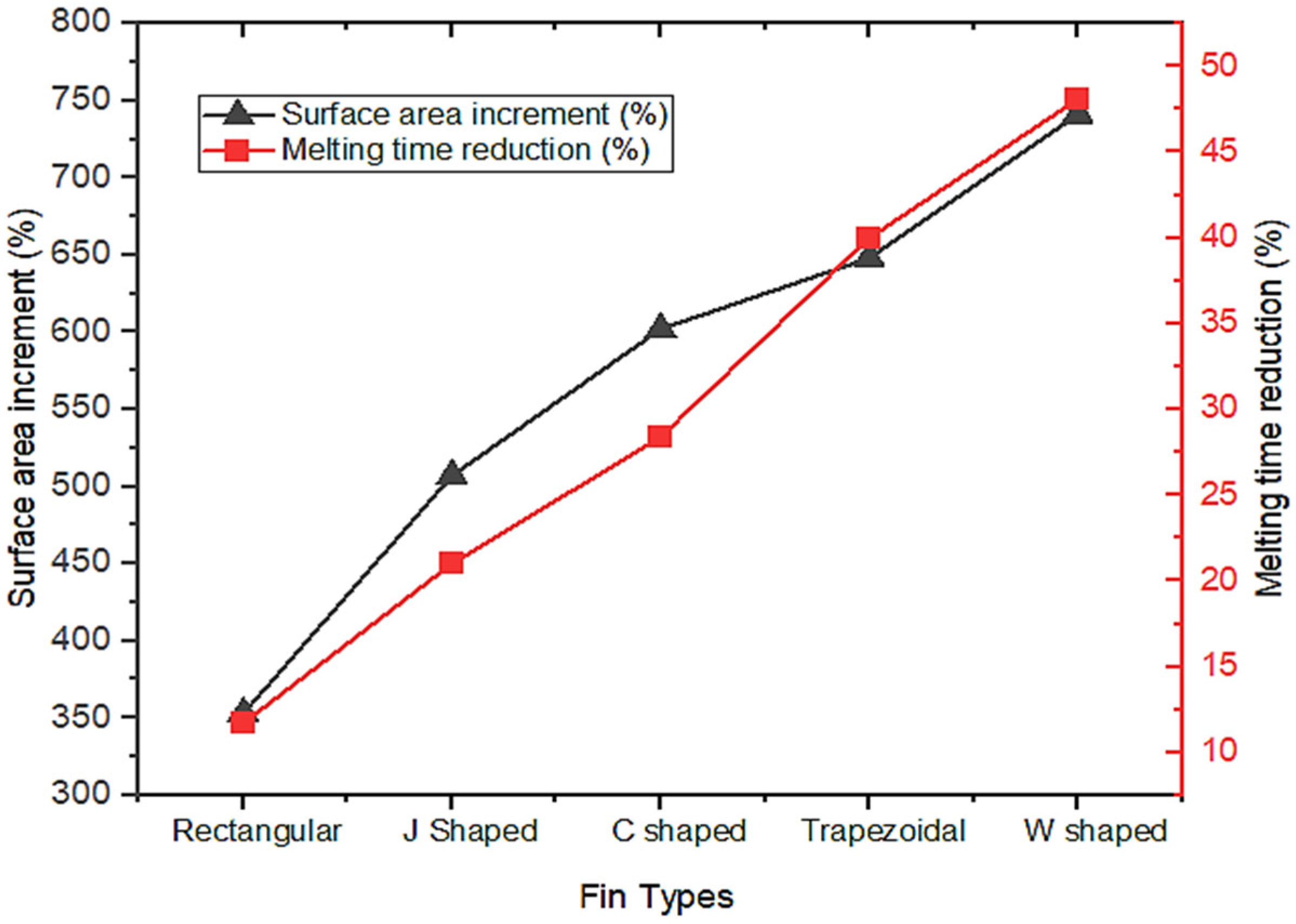

- The results showed that, in comparison with base model from a referenced study, rectangular fins reduced the charging time from 162 min to 143 min, enhancing the system’s efficiency by 11.8%.

- The thermal response of the TES unit was further analyzed using double J fins and C fins. About 85% phase transition from solid to viscous liquid was noted under 115 min duration due to double J fins.

- As localized regions transition to liquid, convection begins in the molten salt near HTF tubes. Orientation of fins from rectangular fins to C-shaped rapidly transforms heat and reduces thermal gradients due to proper thermal mixing and localized vortexes because of natural swirl effect.

- Convection mode of heat transfer was dominant in most cases due to temperature driven buoyancy effects, leading to the development of natural convectional currents and minute vortexes. To further enhance conduction mode, trapezoidal and W-shaped fins were employed possessing large heat transfer area.

- These modifications led to further significant reductions in charging time from 143 min to 97 min and 84 min for trapezoidal and W-shaped fins, respectively.

- The performance-to-area ratio was augmented from basic rectangular shape to W-shaped fin; these results are reinforced by rapid thermal distribution.

- This notable enhancement in heat transfer efficiency was attributed equally to conduction mode in initial stages, then promotion of convective component of heat transfer. Localized vortices generation and enhancement in natural convection because of buoyancy effect definitely improved the thermal performance of the TES tank.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations & Nomenclature

| Specifications | Units | Symbols |

| Specific heat capacity | kJ/kg·K | Cp |

| Thermal conductivity | W/m·K | K |

| Latent heat energy | J/g | L |

| Useful heat energy | J | Qu |

| Reynold number | - | Re |

| Nusselt number | - | Nu |

| Density | Kg/m3 | ρ |

| Thermal expansion coefficient | °C−1 | ᵅ |

| Radius | mm | r |

| Inner radius | mm | ri |

| Radius of HTF pipe (Inner) | mm | r1 |

| Radius of central pipe (outer) | mm | r2 |

| Radius of outer piper | mm | r3 |

| Mean radius | mm | rm |

| Temperature | K | T |

| Initial | - | ini |

| Heat transfer fluid tube temperature | K | THTFT |

| Density at specific temperature | Kg/m3 | ρ1 |

| expansion coefficient | 1/K | |

| Reference temperature | K | Tref |

| Dynamic viscosity | Pa·s | |

| Liquid fraction | - | |

| Inlet | - | in |

| Mushy zone | - | mush |

| Reference state | - | ref |

| Initial/reference temperature | K | T1 |

| Final/desired temperature | K | T2 |

| Initial | - | i |

| Time | s | t |

| Velocity vector | m/s | |

| Mushy zone constant | kg/s·m3 | Zmush |

| Inner diameter | m | |

| Velocity of fluid | m/s | U |

| Diameter of pipe | m | Dp |

| Length of pipe | m | Lp |

| Friction factor | - | |

| Height difference between the top and the bottom of the system | - | hs |

| Mass flow | kg/s | Mv |

| Gravity | m/s2 | g |

| Sensible enthalpy | J/kg | h |

| Total enthalpy | J | H |

| Source term | - | |

| Pressure | Pa | P |

References

- Shazad, A.; Uzair, M. Utilization of Solar Energy for Cooling Applications: A Review. Mem. Investig. Ing. 2023, 24, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazad, A.; Tufail, M.; Uzair, M. Trends in research on latent heat storage using PCM, a bibliometric analysis. Trans. Can. Soc. Mech. Eng. 2024, 48, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, A.; Akbari, A.D.; Rosen, M.A. A novel combination of absorption heat transformer and refrigeration for cogenerating cooling and distilled water: Thermoeconomic optimization. Renew. Energy 2022, 194, 978–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figaj, R.; Szubel, M.; Przenzak, E.; Filipowicz, M. Feasibility of a small-scale hybrid dish/flat-plate solar collector system as a heat source for an absorption cooling unit. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 163, 114399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, M.; Uzair, M.; Raza, S.A. Optimization of thermal storage using different materials for cooking with solar power. Trans. Can. Soc. Mech. Eng. 2022, 46, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazad, A.; Uzair, M.; Tufail, M. Impact of blending of phase change material for performance enhancement of solar energy storage. Renew. Energy 2024, 227, 120530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, M.; Uzair, M. Performance comparison of solid-state and fluid-driven thermal storage system. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 3247–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.J.; Ranjbar, A.A.; Sedighi, K.; Rahimi, M. A combined experimental and computational study on the melting behavior of a medium temperature phase change storage material inside shell and tube heat exchanger. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2012, 39, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.J.; Rahimi, M.; Bahrampoury, R. Experimental and computational evolution of a shell and tube heat exchanger as a PCM thermal storage system. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2014, 50, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, K.A.; Lino, F.A.; Da Silva, R.C.; De Jesus, A.B.; Paixao, L.C. Experimentally validated two dimensional numerical model for the solidification of PCM along a horizontal long tube. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2014, 75, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathelt, A.G.; Viskanta, R. Heat transfer at the solid-liquid interface during melting from a horizontal cylinder. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 1980, 23, 1493–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başal, B.; Ünal, A. Numerical evaluation of a triple concentric-tube latent heat thermal energy storage. Sol. Energy 2013, 92, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürtürk, M.; Kok, B. A new approach in the design of heat transfer fin for melting and solidification of PCM. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 153, 119671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowski, M.; Andrzejczyk, R. Recent advances of selected passive heat transfer intensification methods for phase change material-based latent heat energy storage units: A review. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 144, 106795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalaiselvam, S.; Veerappan, M.; Aaron, A.A.; Iniyan, S. Experimental and analytical investigation of solidification and melting characteristics of PCM’s inside cylindrical encapsulation. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2008, 47, 858–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mo, S.; Zhou, Z.; Du, Y.; Jia, L.; Chen, Y. Nanoparticle-enhanced phase change materials for thermal energy storage: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 223, 116040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettawee, S.; Assassa, G.M. Thermal conductivity enhancement in a latent heat storage system. Sol. Energy 2007, 81, 839–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadi, J.M.; Hosseini, S.F. Nanoparticle-enhanced phase change materials (NEPCM) with great potential for improved thermal energy storage. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2007, 34, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Ranjbar, A.A.; Ganji, D.D.; Sedighi, K.; Hosseini, M.J.; Bahrampoury, R. Analysis of geometrical and operational parameters of PCM in a fin and tube heat exchanger. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2014, 53, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, M.; Ranjbar, A.A.; Ganji, D.D.; Sedighi, K.; Hosseini, M.J. Experimental Investigation of Phase Change inside a Finned-Tube Heat Exchanger. J. Eng. 2014, 2014, 641954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat, S.; Al-Abidi, A.A.; Sopian, K.; Sulaiman, M.Y.; Mohammad, A.T. Enhance heat transfer for PCM melting in triplex tube with internal–external fins. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 74, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abidi, A.; Mat, S.; Sopian, K.; Sulaiman, M.Y.; Mohammad, A.T. Experimental study of melting and solidification of PCM in a triplex tube heat exchanger with fins. Energy Build. 2014, 68, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyenim, F.; Eames, P.; Smyth, M. Heat transfer enhancement in medium temperature thermal energy storage system using a multitube heat transfer array. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornarelli, F.; Ceglie, V.; Fortunato, B.; Camporeale, S.M.; Torresi, M.; Oresta, P.; Miliozzi, A. Numerical simulation of a complete charging-discharging phase of a shell and tube thermal energy storage with phase change material. Energy Procedia 2017, 126, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddegh, S.; Wang, X.; Henderson, A.D. A comparative study of thermal behaviour of a horizontal and vertical shell-and-tube energy storage using phase change materials. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 93, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozafari, M.; Hooman, K.; Lee, A.; Cheng, S. Numerical study of a dual-PCM thermal energy storage unit with an optimized low-volume fin structure. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 215, 119026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, L.B.; Zhang, K.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W.W. Prediction of the main characteristics of the shell and tube bundle latent heat thermal energy storage unit using a shell and single-tube unit. Appl. Energy 2022, 323, 119633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Rong, J.; Wang, D.; Zhao, X.; Meng, L.; Arıcı, M.; Li, D. Synergistic enhancement of heat transfer and thermal storage characteristics of shell and tube heat exchanger with hybrid nanoparticles for solar energy utilization. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, Q.; Ge, R. Comparative investigation of charging performance in shell and tube device containing molten salt-based phase change materials for thermal energy storage. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2023, 43, 102804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazad, A.; Uzair, M.; Tufail, M. Thermal performance enhancement of latent heat energy storage unit. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2025, 150, 7767–7777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, M.; Uzair, M.; Allauddin, U. Effect of geometric configurations on charging time of latent-heat storage for solar applications. Renew. Energy 2021, 179, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abidi, A.; Mat, S.; Sopian, K.; Sulaiman, M.Y.; Mohammad, A.T. Numerical study of PCM solidification in a triplex tube heat exchanger with internal and external fins. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 61, 684–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dimensions of Storage Tank (mm) | |

|---|---|

| Length | 1000 |

| Outer Diameter | 200 |

| Diameter of central pipe | 150 |

| Diameter of HTF pipe | 15 |

| Maximum height of fin | 15 |

| Properties | Values |

|---|---|

| Density | 1796 kg/m3 |

| Thermal Conductivity | 0.55 W/(m.K) |

| Thermal Expansion Coefficient | 54.7 × 10−6 °C−1 |

| Cp | 0.75 if T ≤ 383 K 4.1 if 383 < T ≤ 388 K 1.4 if 388 < T ≤ 488 K 12 if 488 < T ≤ 498 K 1.6 if T > 498 K |

| Liquidus Temperature | 495 K |

| Solidus Temperature | 487 K |

| Pure Solvent Melting Heat | 102 kJ/kg |

| Properties | Value | Temperature Range |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Expansion Coefficient | 0.001012 °C−1 | - |

| Thermal Conductivity | 0.143–0.13 W/m·K | 298 K–500 K |

| Density | 0.684 d/mL | - |

| Specific Heat | 1.9–2.90 kJ/kg·K | 308 K–580 K |

| Serial. No | Fin Configuration | Effective Surface Area for Single Fin (mm2) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rectangular | 17,030 |

| 2 | Double J-shaped | 22,880 |

| 3 | C-shaped | 26,400 |

| 4 | Trapezoidal-shaped | 28,160 |

| 5 | W-shaped | 31,680 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shazad, A.; Akhtar, M.; Hussain, A.; Alsaleh, N.; Haldar, B. Thermal Performance Assessment of Heat Storage Unit by Investigating Different Fins Configurations. Energies 2025, 18, 5920. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225920

Shazad A, Akhtar M, Hussain A, Alsaleh N, Haldar B. Thermal Performance Assessment of Heat Storage Unit by Investigating Different Fins Configurations. Energies. 2025; 18(22):5920. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225920

Chicago/Turabian StyleShazad, Atif, Maaz Akhtar, Ahmad Hussain, Naser Alsaleh, and Barun Haldar. 2025. "Thermal Performance Assessment of Heat Storage Unit by Investigating Different Fins Configurations" Energies 18, no. 22: 5920. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225920

APA StyleShazad, A., Akhtar, M., Hussain, A., Alsaleh, N., & Haldar, B. (2025). Thermal Performance Assessment of Heat Storage Unit by Investigating Different Fins Configurations. Energies, 18(22), 5920. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18225920