Methodology for Evaluating and Comparing Different Sustainable Energy Generation and Storage Systems for Residential Buildings—Application to the Case of Spain

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Sustainable Energy Generation and Storage Systems for Residential Buildings

2.1. Solar Panels

2.2. Electrochemical Storage Technologies

2.3. Hydrogen Energy Systems for Residential Applications

2.4. Combined Heat and Power Systems for Residential Buildings

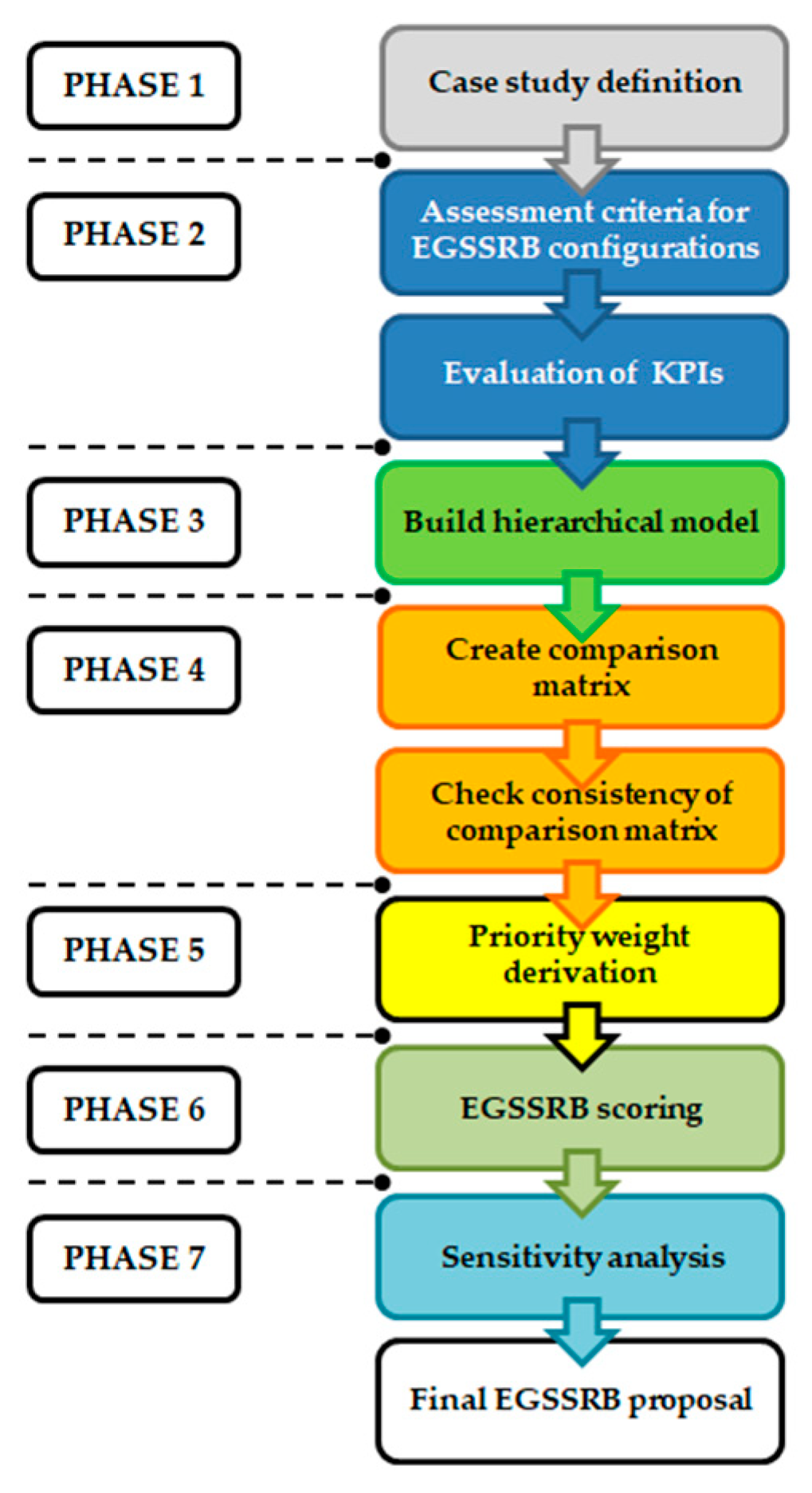

3. Methodology

- Phase 1. Case study definition. Clearly articulates the decision-making objective.

- Phase 2. Identification of the assessment criteria for EGSSRB configurations. These criteria should be well-defined, measurable, and suitable for the decision-making objective. The measurement of the criteria is conducted by the evaluation of KPIs.

- Phase 3. Build a hierarchical model. Develop a hierarchical structure that visually organizes the decision elements by levels.

- Phase 4. Pairwise comparisons. Conduct pairwise assessments of criteria and alternatives using several comparison matrices.

- Phase 5. Priority weight derivation. Calculate the relative weights of criteria and the alternatives by solving fuzzy linear equations derived from the pairwise comparisons. These weights express the relative significance of each element.

- Phase 6. Overall score computation. Combine the weights with the performance values to calculate an aggregate score for each alternative, indicating the extent to which it meets the defined criteria.

- Phase 7. Sensitivity analysis: evaluate the stability of the results by analyzing how variations in input values or priority weights affect the final rankings, thereby testing the robustness of the decision model.

3.1. Phase 1: Case Study Definition

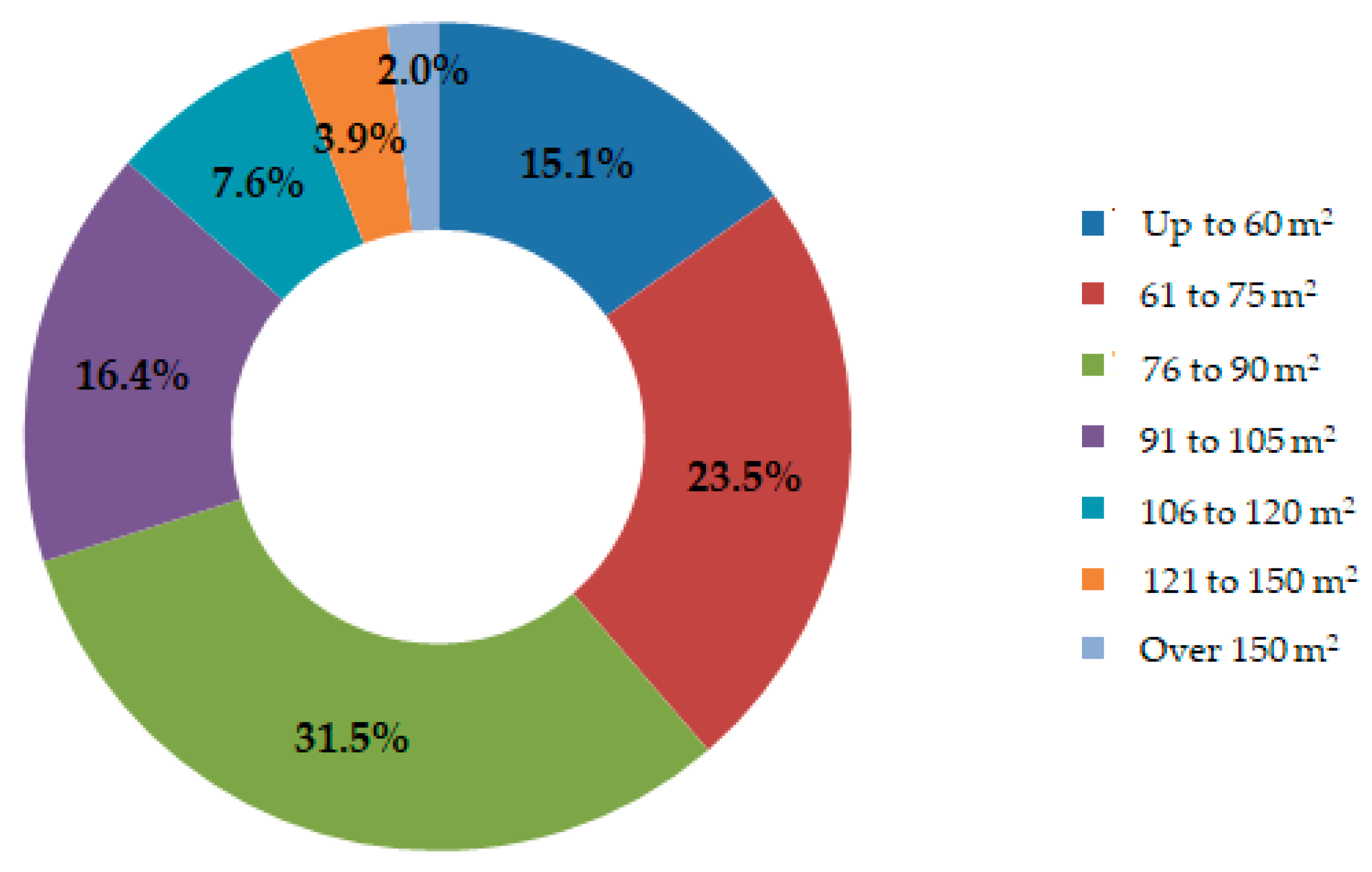

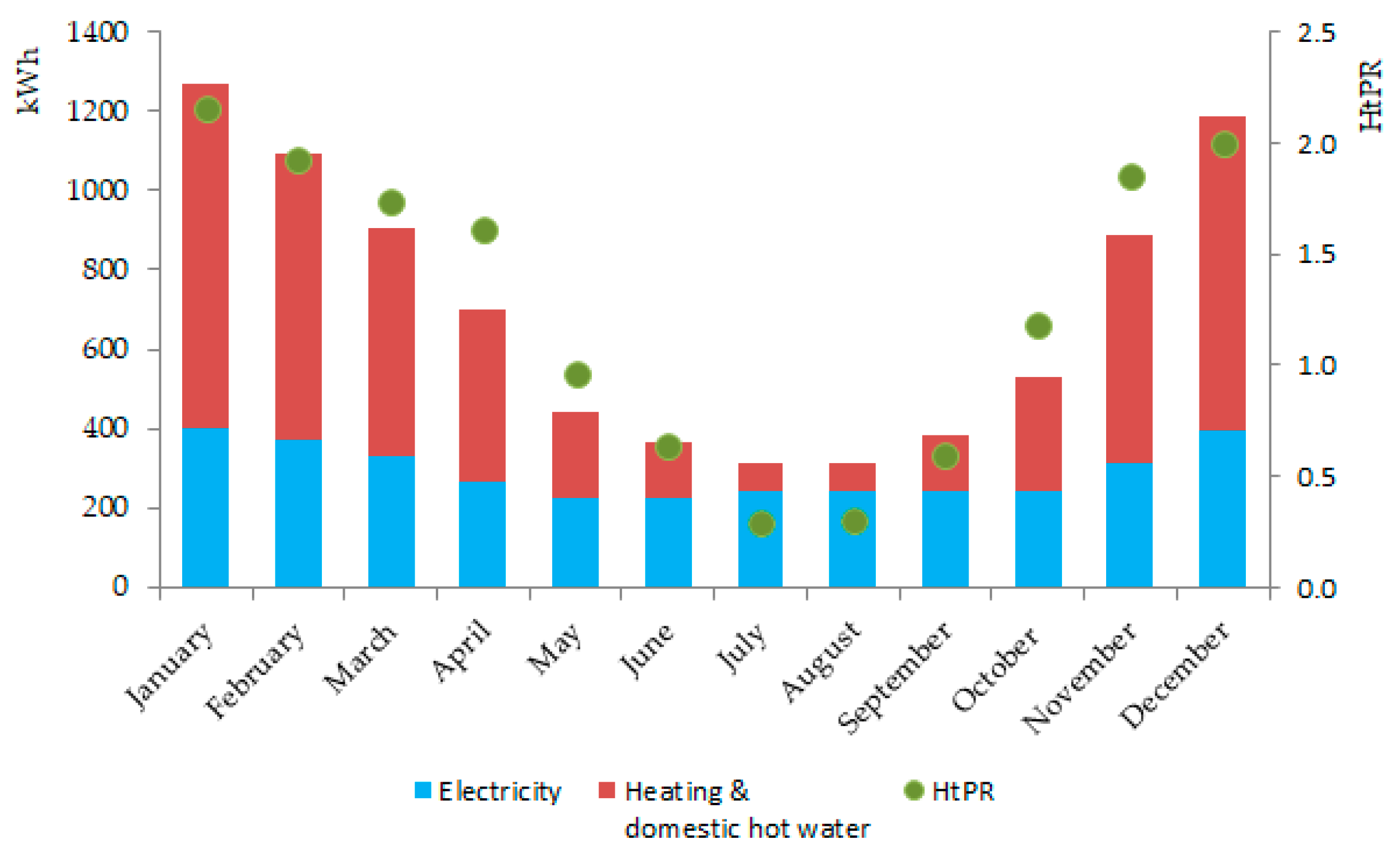

3.1.1. Residential Building Characteristics

3.1.2. EGSSRB System Layouts Description

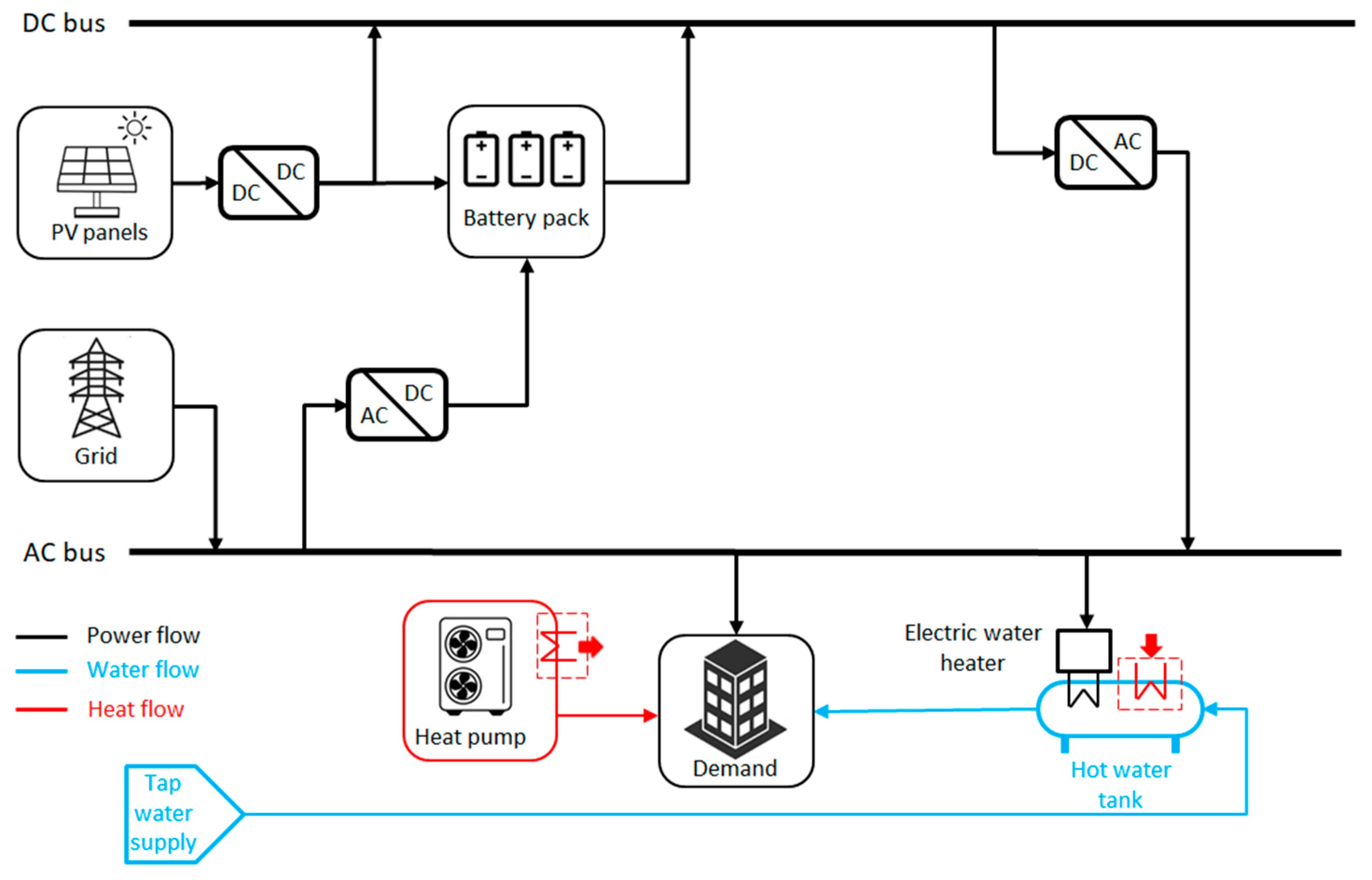

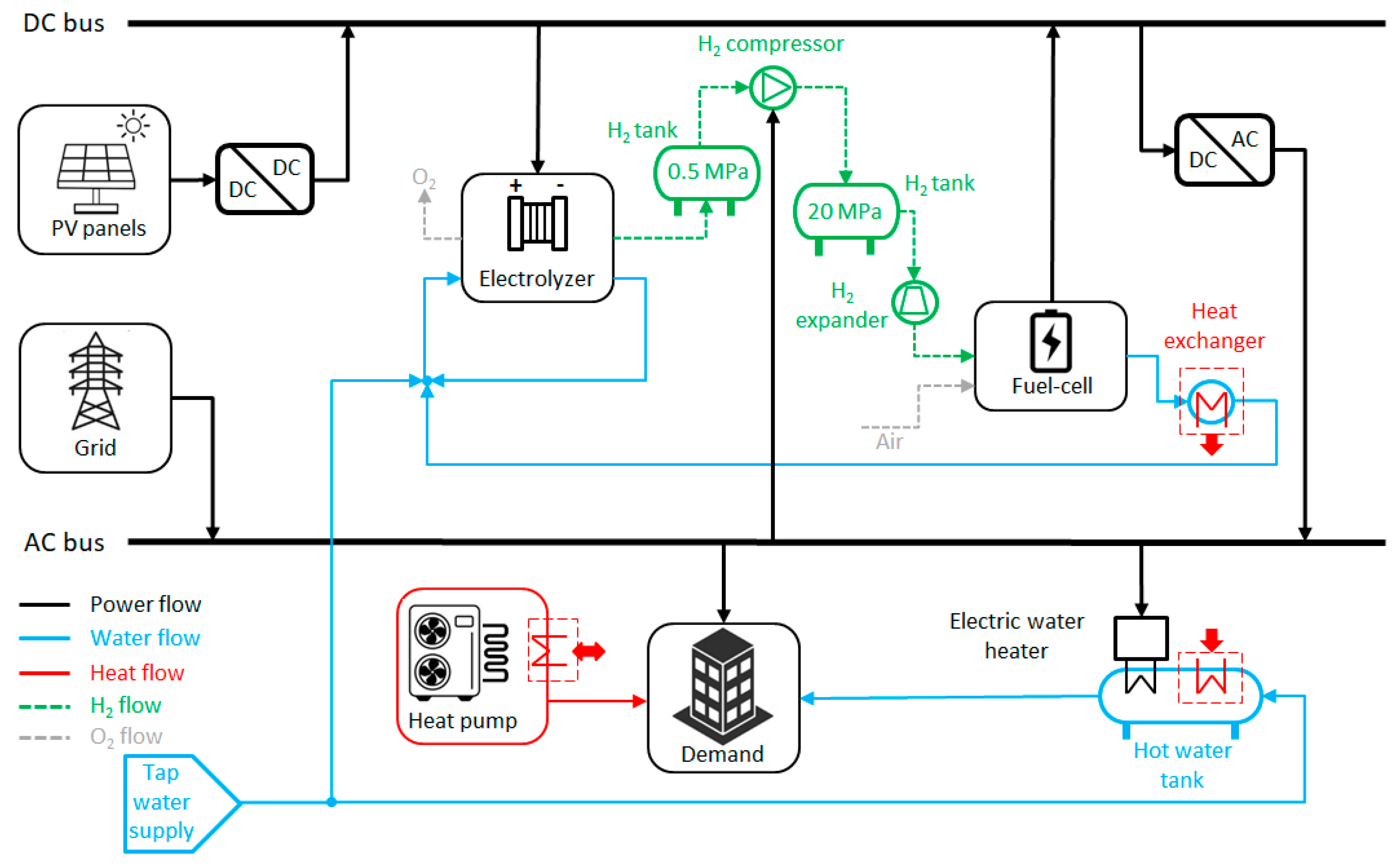

- Photovoltaic System with Battery Backup (PSBB); see Figure 5. The PV system generates electricity that is consumed by the building or stored in the battery pack. When the electricity demand exceeds the PV output, the battery acts as a backup system and, if there is a deficit, it is covered by drawing power from the electrical grid. The hot water is produced by a combination of a heat pump water heater and a backup electric water heater. The space heating demand is provided by a heat pump.

- Photovoltaic System with Hydrogen Storage Backup (PSHB); see Figure 6. The PV system generates electricity that is consumed by the building or used to generate hydrogen that is stored in a pressure vessel at 20 MPa. When the household demands electricity that exceeds the PV output, the electricity demand is covered by the fuel cell system output and/or the grid. The heat generated by the fuel cell is used to produce hot water, which is stored in a tank. When the stored thermal energy is insufficient, the additional heating requirements are completed with a combination of a heat pump water heater and a backup electric water heater. The space heating demand is met by a heat pump cogeneration system that utilizes the residual heat generated in the fuel cell.

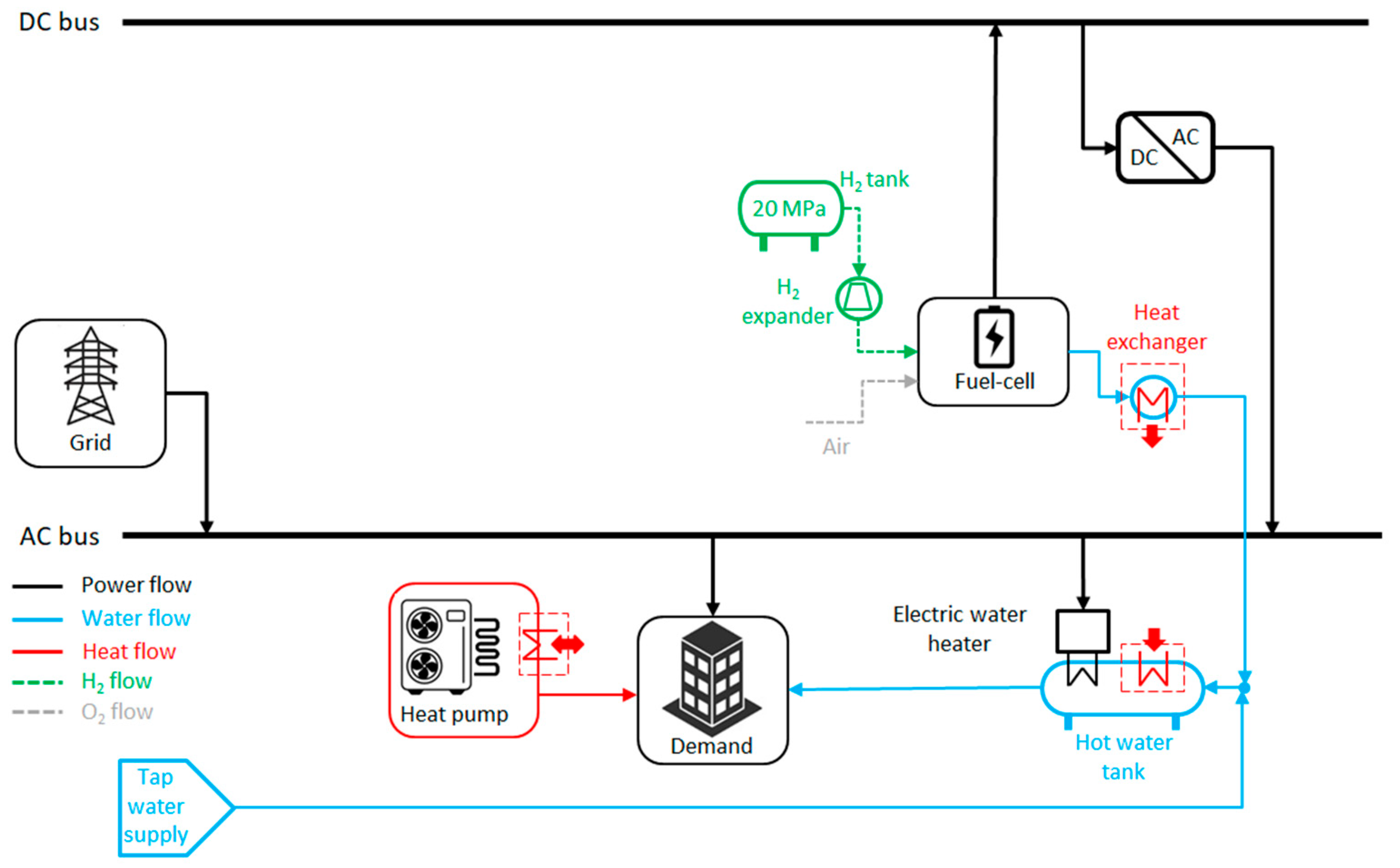

- Grid-Based System with Renewable Hydrogen Contribution (GSHC); see Figure 7. The electric demand of the building is covered with electricity from the grid. However, in specific cases, the power demand could be totally or partially met by the electricity supplied by the fuel cell. The hydrogen to feed the fuel cell system is provided by a gas supplier in high-pressure cylinders at pressures up to 20 MPa as standard. The heat generated by the fuel cell is used to produce hot water, which is stored in a tank. When the stored thermal energy is insufficient, the additional heating requirements are completed with a combination of a heat pump water heater and a backup electric water heater. The space heating demand is met by a heat pump cogeneration system that utilizes the residual heat generated in the fuel cell.

- The PV system must cover at least 25% of energy demand, considering that the PSH coefficient can vary between 2.5 and 8 values.

- The battery pack capacity must fulfill the demand and provide an energy reserve for one day, considering a maximum depth of discharge of 80%.

- The fuel cell and the electrolyzer for the PSHB system are designed to use the excess of energy generated by solar panels in the form of pressurized hydrogen at 200 bar for later reuse. The electrolyzer is powered only by the excess electricity produced by the solar panels. In this case, the solar panels focused on covering the electricity demand from the electrical load (3500 kWh per year).

- The hydrogen pressure vessel capacity in the PSHB system is designed to store the PV system’s excess production during the year and to cover peak energy demands.

- The fuel cell in the GSHC system is selected to cover most of the space heating and hot-water demand, provided that the electricity produced is at most equal to the demand.

- The heat pump coefficient of performance (COP) is 4, meaning that for each kWh of electricity consumed, the system provides 4 kWh of heating or cooling energy.

- The energy density of hydrogen is determined based on the lower heating value (LHV) of 33.3 kWh/kg.

- The cost of electricity and hydrogen acquired is EUR 0.135/kWh and EUR 0.3/kWh (EUR 10/kgH2), respectively. The excess of energy generated by the system is transferred to the electrical grid, yielding a profit of EUR 0.05/kWh.

3.2. Phase 2: Identification of the Assessment Criteria for EGSSRB Configurations

3.2.1. Definition of the Key Performance Indicators

3.2.2. Evaluation of KPIs

- System Cost (SC). Costing for a configuration is determined by summing up the LCOE and LCOS of its components, as expressed in Equation (1).

- Commercial Deployment (CD). It is a qualitative indicator that is evaluated using the quantization scaling that considers the supplier availability and after-sales service: 1 (very low), 2 (low), 3 (moderate), 4 (high), and 5 (very high).

- Fail-safety (FS). It is a qualitative indicator that is evaluated using the quantization scaling that considers the level of certification requirements: 5 (very low), 4 (low), 3 (moderate), 2 (high), and 1 (very high).

- Global Efficiency (EF). Efficiency evaluation for a configuration is determined by the ratio between the useful energy output (Eg) and the external energy consumed (Ec), as expressed in Equation (3). The external energy consumed is provided by the electrical grid (Ece) or a green hydrogen supplier (EcH2).

- Capacity Factor (CF). This is defined as the ratio between the energy acquired from the (Ece) and the household energy demand (Ed), as expressed in Equation (4).

- System’s Reliability (SR). Reliability for a configuration is determined with its system component characteristic lifespan (CCL) referenced to a system life expectancy (SLE) of 25 years using a Weibull model [61] with a shape parameter value (β) of 2; Equation (5).

- Use Phase Emissions (UPE). Emissions during the operation of the system depend on the energy consumption of the system, electricity and hydrogen, and the emission factor (EM) measured in kg CO2eq per kWh associated; see Equation (6).

- System Footprint (SF). The system space requirements are estimated using commercially available systems as a reference. It is calculated as the ratio of the sum of the space used by the components of the system (SpRej) and the useful energy output (Eg) (Equation (7)).

3.3. Phase 3: Hierarchical Model

3.4. Phase 4: Pairwise Comparisons

3.4.1. Create Comparison Matrix

3.4.2. Consistency of the Comparison Matrix

3.5. Phase 5: Priority Weight Derivation

3.6. Phase 6: Overall Score Computation

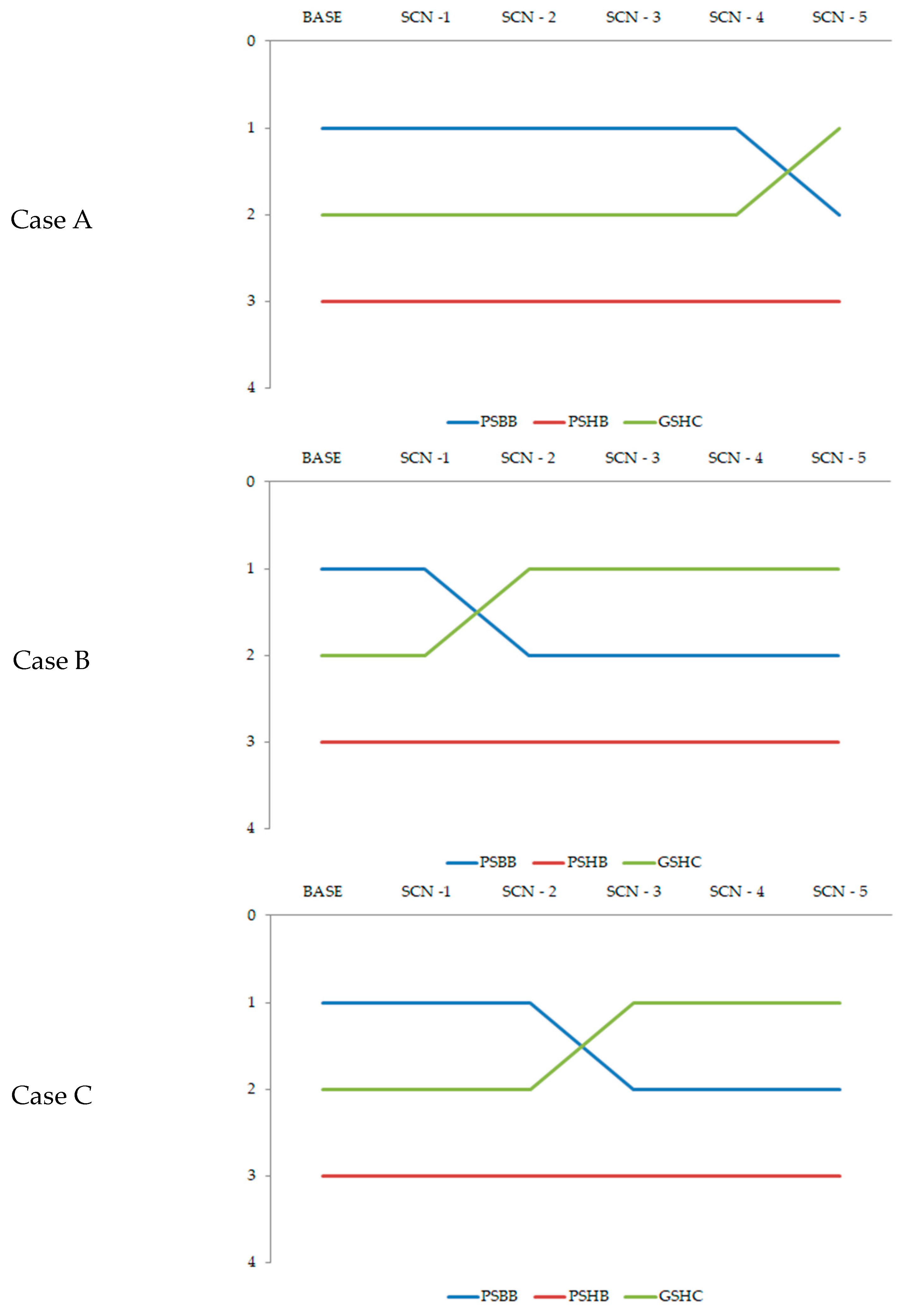

3.7. Phase 7: Sensitivity Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Evaluation of EGSSRB Configurations

4.2. AHP Analysis

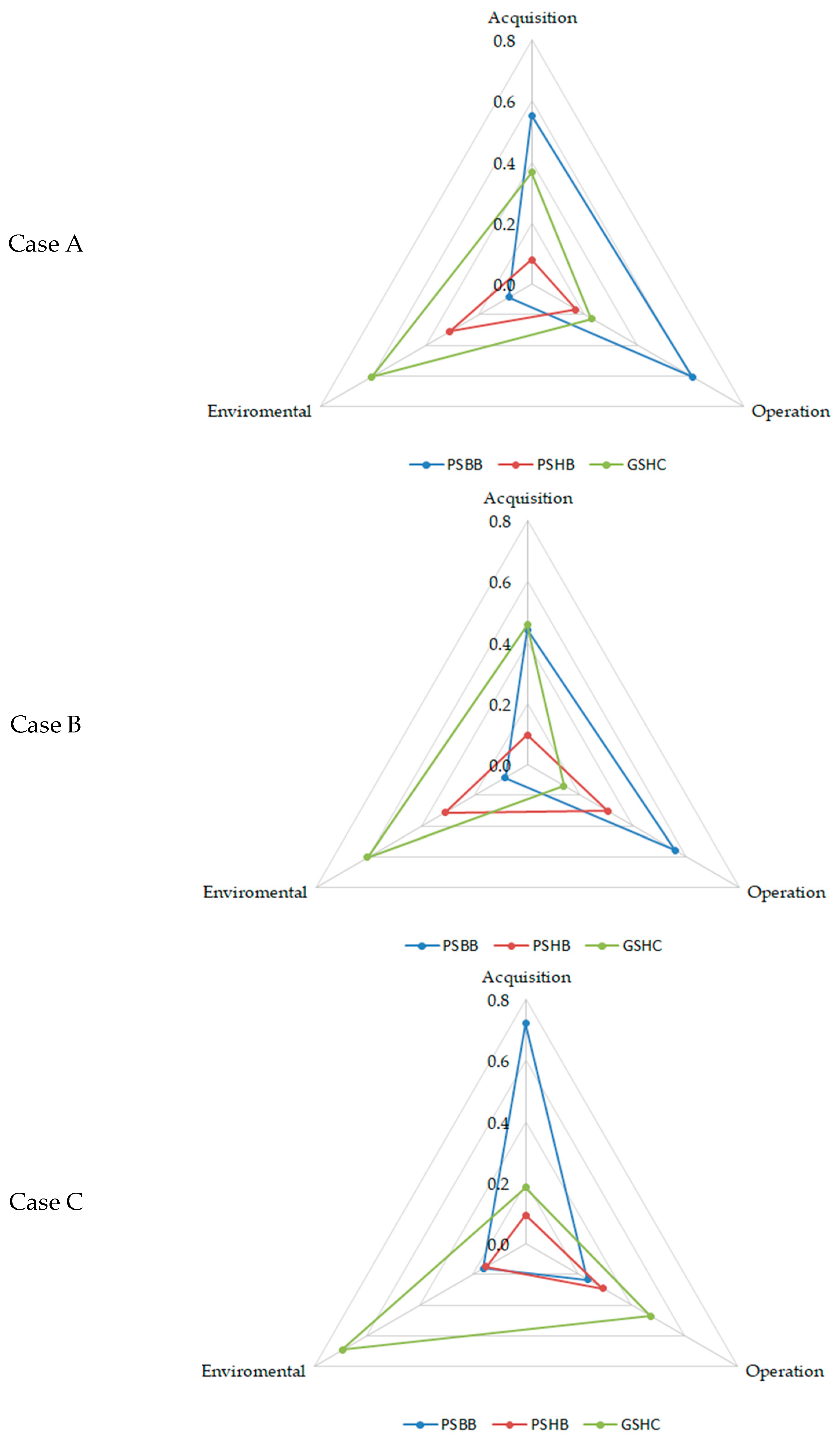

- Case A. It has been considered that the most important sub-criteria are the fail-safety, the system’s reliability, and the use phase emissions.

- Case B. In this case, system cost, efficiency, and use phase emissions are the most influential sub-criteria.

- Case C. Finally, this case considers that commercial deployment, capacity factor, and system footprint are the most relevant sub-criteria.

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFC | Alkaline Fuel Cell |

| AHP | Analytical Hierarchy Process |

| CD | Commercial Deployment |

| CDM | Comparison Decision Matrix |

| CHP | Combined Heat and Power systems |

| CI | Consistency Index |

| CR | Consistency Ratio |

| EF | Global Efficiency |

| EGSSRB | Energy Generation and Storage System for Residential Buildings |

| EMS | Energy Management System |

| FAHP | Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process |

| FDM | Final Decision Matrix |

| FS | Fail-safety |

| GSHC | Grid-Based System with Renewable Hydrogen Contribution |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicators |

| LCOE | Levelized Cost of Energy |

| LCOS | Levelized Cost of Storage |

| LHW | Lower Heating Value |

| MCDM | Multi-criteria Decision-making Method |

| PEMFC | Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell |

| PSH | Peak Sun Hour |

| PSHB | Photovoltaic System with Hydrogen Storage Backup |

| PSBB | Photovoltaic System with Battery Backup |

| PV | Photovoltaic panels |

| PWR | Power Rating |

| SC | System Cost |

| SF | System Footprint |

| SESS | Stationary Energy Storage Systems |

| SMR | Steam Methane Reforming |

| SOFC | Solid Oxide Fuel Cell |

| SR | System’s Reliability |

| STC | Solar Thermal Collectors |

| TFN | Triangular Fuzzy Numbers |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Levels |

| UPE | Use Phase Emissions |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid technology |

Appendix A

| Parameter | Units | Value | Considerations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment cost | EUR/household | 2730 | Considering six solar panels per household | [34,71] |

| Maintenance cost | EUR/household | 27.3 | 1% of the investment cost | Own assumption |

| Electric efficiency | % | 20.7 | Standard panel dimensions 1.69 m × 1 m (length × width) and 1000 W/m2 of incident solar power (standard solar irradiance) | Own calculation |

| Peak power | kWp | 0.35 | Peak power output per panel | Own assumption |

| Rated energy output | kWh | 1.60 | Rated energy output per panel PSH ratio is between 2.5 to 8 | Own calculation |

| System lifespan | year | 20 | [34,71] | |

| System reliability | unitless | 0.94 | Own calculation | |

| Space requirements | m2/household | 11.2 | Standard panel dimensions 1.69 m × 1 m (length × width), optimum inclination angle of 40 degrees and minimum solar irradiation angle to the horizontal of 23.5 degrees | Own calculation |

| Parameter | Units | Value | Considerations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment cost | EUR/household | 10,476 | 25 kWh of net usable capacity | Own calculation |

| Maintenance cost | EUR/household | 104.76 | 1% of the investment cost | [71] |

| Electric efficiency | % | 95 | Charge and discharge cycles | [34] |

| Peak power | kWp | 17.5 | C-rate of 0.5 C | Own calculation |

| Rated energy output | kWh | 25 | Own calculation | |

| System lifespan | year | 16 | Considering 6000 cycles of service life and one cycle per day | [34,50] |

| System reliability | unitless | 0.73 | Own calculation | |

| Space requirements | m2/household | 0.49 | Floor-standing cabinet (modular stacks) 0.3–0.4 m2 per 25 kWh (gross capacity) | Own calculation |

| Parameter | Units | Value | Considerations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment cost | EUR/household | 9400 | Fuel cell power output of 2.9 kW, considering that fuel cell stacks operate more efficiently at partial loads (25%), leading to higher overall electrical efficiency | [34,49,51,70,71] |

| Maintenance cost | EUR/household | 93.7 | 1% of the investment cost | Own calculation |

| Electric efficiency | % | 50 | [34,49,51,70,71] | |

| Thermal efficiency | % | 40 | [34,49,51,70,71] | |

| Peak power | kWp | 2.9 | Considering a peak electricity demand of 16 kWh per day and partial load (25%) operation | Own calculation |

| Rated energy output | kWh | 0.7 | Considering 22 operating hours per day | Own calculation |

| System lifespan | year | 12 | [46,71] | |

| System reliability | unitless | 0.31 | Own calculation | |

| Space requirements | m2/household | 0.4 | Own assumption |

| Parameter | Units | Value | Considerations | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment cost | EUR/household | 2345 | Own calculation | |

| Maintenance cost | EUR/household | 350 | 1% of the investment cost | Own calculation |

| Electric efficiency | % | 50 | [34,49,51,70,71] | |

| Thermal efficiency | % | 40 | [34,49,51,70,71] | |

| Peak power | kWp | 0.3 | Considering a peak electricity demand of 1.8 kWh per day and partial load (25%) operation | Own calculation |

| Rated energy output | kWh | 0.08 | Considering 22 operating hours per day | Own calculation |

| System lifespan | year | 12 | [46,71] | |

| System reliability | unitless | 0.31 | Own calculation | |

| Space requirements | m2/household | 0.19 | Own assumption |

| Parameter | Units | Value | Comments | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment cost | EUR/household | 6600 | [49,71] | |

| Maintenance cost | EUR/household | 66 | 5% of the investment cost | Own calculation |

| Electric efficiency | % | 75 | [51,71] | |

| Thermal efficiency | % | 15 | [71] | |

| Peak power | kW | 0.8 | Considering a peak production of 0.17 kgH2 per day. | Own calculation |

| Rated energy output | kWh | 9.2 0.24 | Considering 7 operating hours per day | Own calculation |

| System lifespan | year | 15 | [71] | |

| System reliability | unitless | 0.64 | Own calculation | |

| Space requirements | m2/household | 1.0 | Own calculation |

| Parameter | Units | Value | Comments | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment cost | EUR/household | 12,100 | 20 kg of hydrogen tank capacity (20 MPa) | [50,71] |

| Maintenance cost | EUR/household | 121 | 1% of the investment cost | Own assumption |

| System lifespan | year | 25 | [71] | |

| System reliability | unitless | 1.00 | Own calculation | |

| Space requirements | m2/household | 1.03 | Compressed gas cylinders at 200 bar and 298 K have a nominal volume of 250 L | Own calculation |

| Parameter | Units | Value | Comments | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment cost | EUR/household | 8500 | Hydrogen compressor of 0.5 Nm3/h @ 200 bar | Own assumption |

| Maintenance cost | EUR/household | 340 | 4% of the investment cost | Own assumption |

| Electric efficiency | % | 85 | Own assumption | |

| System lifespan | year | 20 | [71] | |

| System reliability | unitless | 0.94 | Own calculation | |

| Space requirements | m2/household | 0.5 | Own calculation |

| Parameter | Units | Value | Comments | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment cost | EUR/household | 7056 | Own assumption | |

| Maintenance cost | EUR/household | 105.8 | 1.5% of the investment cost | Own assumption |

| Electric efficiency | % | 95 | Own assumption | |

| Peak power | kWp | 16.4 | Own calculation | |

| System lifespan | year | 10 | Own assumption | |

| System reliability | unitless | 0.11 | Own calculation | |

| Space requirements | m2/household | 0.67 | Own calculation |

| Parameter | Units | Value | Comments | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment cost | EUR/household | 210 | Estimated capacity of 100 L | Own calculation |

| Maintenance cost | EUR/household | 60 | Own assumption | |

| Electric efficiency | % | 98 | [71] | |

| Thermal efficiency | % | 90 | Usual range of values 85–95% | Own assumption |

| Peak power | kWp | 1.5 | Own assumption | |

| System lifespan | year | 20 | [34,71] | |

| System reliability | unitless | 0.88 | Own calculation | |

| Space requirements | m2/household | 0.20 | Own calculation |

Appendix B

| Alternatives | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Sub-Criteria | Normalized Wi | PSBB | PSHB | GSHC |

| Acquisition | 0.52 | 0.553 | 0.080 | 0.367 | |

| System Cost | 0.23 | 0.359 | 0.108 | 0.533 | |

| Commercial Deployment | 0.07 | 0.800 | 0.100 | 0.100 | |

| Fail-safety | 0.70 | 0.590 | 0.069 | 0.341 | |

| Operation | 0.31 | 0.608 | 0.167 | 0.225 | |

| Global Efficiency | 0.23 | 0.572 | 0.369 | 0.060 | |

| Capacity Factor | 0.07 | 0.060 | 0.350 | 0.589 | |

| System’s Reliability | 0.70 | 0.675 | 0.084 | 0.242 | |

| Environmental | 0.17 | 0.085 | 0.310 | 0.605 | |

| Use Phase Emissions | 0.82 | 0.064 | 0.356 | 0.580 | |

| System Footprint | 0.18 | 0.183 | 0.096 | 0.721 | |

| 0.489 | 0.147 | 0.365 | |||

| Rank | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Alternatives | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Sub-Criteria | Normalized Wi | PSBB | PSHB | GSHC |

| Acquisition | 0.52 | 0.442 | 0.099 | 0.459 | |

| System Cost | 0.70 | 0.359 | 0.108 | 0.533 | |

| Commercial Deployment | 0.07 | 0.800 | 0.100 | 0.100 | |

| Fail-safety | 0.23 | 0.590 | 0.069 | 0.341 | |

| Operation | 0.31 | 0.559 | 0.303 | 0.138 | |

| Global Efficiency | 0.70 | 0.572 | 0.369 | 0.060 | |

| Capacity Factor | 0.07 | 0.060 | 0.350 | 0.589 | |

| System’s Reliability | 0.23 | 0.675 | 0.084 | 0.242 | |

| Environmental | 0.17 | 0.084 | 0.312 | 0.604 | |

| Use Phase Emissions | 0.83 | 0.064 | 0.356 | 0.580 | |

| System Footprint | 0.17 | 0.183 | 0.096 | 0.721 | |

| 0.416 | 0.199 | 0.385 | |||

| Rank | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Alternatives | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Sub-Criteria | Normalized Wi | PSBB | PSHB | GSHC |

| Acquisition | 0.52 | 0.734 | 0.095 | 0.171 | |

| System Cost | 0.07 | 0.543 | 0.123 | 0.334 | |

| Commercial Deployment | 0.70 | 0.800 | 0.100 | 0.100 | |

| Fail-safety | 0.23 | 0.590 | 0.069 | 0.341 | |

| Operation | 0.31 | 0.235 | 0.292 | 0.473 | |

| Global Efficiency | 0.07 | 0.572 | 0.369 | 0.060 | |

| Capacity Factor | 0.70 | 0.060 | 0.350 | 0.589 | |

| System’s Reliability | 0.23 | 0.675 | 0.084 | 0.242 | |

| Environmental | 0.17 | 0.158 | 0.189 | 0.653 | |

| Use Phase Emissions | 0.20 | 0.060 | 0.552 | 0.388 | |

| System Footprint | 0.80 | 0.183 | 0.096 | 0.721 | |

| 0.481 | 0.172 | 0.348 | |||

| Rank | 1 | 3 | 2 |

Appendix C

| Weights | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | BASE | SCN–1 | SCN–2 | SCN–3 | SCN–4 | SCN–5 |

| Acquisition | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.28 |

| Operation | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.35 |

| Environmental | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.37 |

| Alternatives | ||||||

| PSBB | 0.489 | 0.471 | 0.453 | 0.435 | 0.417 | 0.399 |

| PSHB | 0.147 | 0.156 | 0.166 | 0.176 | 0.185 | 0.195 |

| GSHC | 0.365 | 0.373 | 0.381 | 0.389 | 0.397 | 0.406 |

| Rank | ||||||

| PSBB | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| PSHB | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| GSHC | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Weights | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | BASE | SCN–1 | SCN–2 | SCN–3 | SCN–4 | SCN–5 |

| Acquisition | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.28 |

| Operation | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.35 |

| Environmental | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.37 |

| Alternatives | ||||||

| PSBB | 0.416 | 0.403 | 0.390 | 0.377 | 0.364 | 0.350 |

| PSHB | 0.199 | 0.209 | 0.219 | 0.229 | 0.239 | 0.249 |

| GSHC | 0.385 | 0.388 | 0.391 | 0.395 | 0.398 | 0.401 |

| Rank | ||||||

| PSBB | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| PSHB | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| GSHC | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Weights | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | BASE | SCN–1 | SCN–2 | SCN–3 | SCN–4 | SCN–5 |

| Acquisition | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.28 |

| Operation | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.35 |

| Environmental | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.37 |

| Alternatives | ||||||

| PSBB | 0.474 | 0.448 | 0.422 | 0.396 | 0.370 | 0.344 |

| PSHB | 0.164 | 0.168 | 0.172 | 0.176 | 0.179 | 0.183 |

| GSHC | 0.362 | 0.384 | 0.406 | 0.428 | 0.450 | 0.473 |

| Rank | ||||||

| PSBB | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| PSHB | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| GSHC | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

References

- Eurostat. Energy Consumption in Households; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2025.

- Fernández, R.A. Stochastic Analysis of Future Scenarios for Battery Electric Vehicle Deployment and the Upgrade of the Electricity Generation System in Spain. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 316, 128101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.; Bukhsh, W.; Bell, K.; Brand, C. Vehicle to Grid: Driver Plug-in Patterns, Their Impact on the Cost and Carbon of Charging, and Implications for System Flexibility. eTransportation 2022, 13, 100180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. Directive 2010/31/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 2010 on the Energy Performance of Buildings (Recast); European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- BOE. Ley 7/2021, de 20 de Mayo, de Cambio Climático y Transición Energética; Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE): Madrid, Spain, 2021; Volume 121, pp. 62009–62052.

- Morgado, H.; Erbach, G. Spain’s Climate Action Strategy; European Parliamentary Research Service: Luxembourg, 2024.

- Vieira, F.M.; Moura, P.S.; de Almeida, A.T. Energy Storage System for Self-Consumption of Photovoltaic Energy in Residential Zero Energy Buildings. Renew. Energy 2017, 103, 308–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Yildirim, M.; Bartyzel, F.; Vallati, A.; Woźniak, M.K.; Ocłoń, P. Efficient Energy Storage in Residential Buildings Integrated with RESHeat System. Appl. Energy 2023, 335, 120752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maka, A.O.M.; Chaudhary, T.N. Performance Investigation of Solar Photovoltaic Systems Integrated with Battery Energy Storage. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Hassan, M.; Bremner, S.; Menictas, C.; Kay, M. Assessment of Hydrogen and Lithium-Ion Batteries in Rooftop Solar PV Systems. J. Energy Storage 2024, 86, 111182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, L.; Berardi, U. Hybrid Solar Energy Systems with Hydrogen and Electrical Energy Storage for a Single House and a Midrise Apartment in North America. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babatunde, O.M.; Munda, J.L.; Hamam, Y. Hybridized Off-Grid Fuel Cell/Wind/Solar PV /Battery for Energy Generation in a Small Household: A Multi-Criteria Perspective. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 6437–6452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyturk, G.; Kizilkan, O.; Ezan, M.A.; Colpan, C.O. Design, Modeling, and Analysis of a PV/T and PEM Fuel Cell Based Hybrid Energy System for an off-Grid House. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 67, 1181–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, C.; Devrim, Y. Green Hydrogen Based Off-Grid and on-Grid Hybrid Energy Systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 39084–39096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, G.; Schropp, E.; Steegmann, N.; Möller, M.C.; Gaderer, M. Environmental Performance of a Hybrid Solar-Hydrogen Energy System for Buildings. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 49, 1185–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdan, P.; Zeyen, E.; Gallego-Castillo, C.; Victoria, M. Distributed Photovoltaics Provides Key Benefits for a Highly Renewable European Energy System. Appl. Energy 2024, 360, 122721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pytel, K.; Hudy, W.; Filipek, R.; Piaskowska-Silarska, M.; Depešová, J.; Sito, R.; Janiszewska, E.; Sieradzka, I.; Sulkowski, K. Evaluation of Environmental Factors Influencing Photovoltaic System Efficiency Under Real-World Conditions. Energies 2025, 18, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda-Oviedo, E.H. A Review of Operational Factors Affecting Photovoltaic System Performance. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 100942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, J.; Riesco, J.; Jiménez, C. Atlas de Radiación Solar En España Utilizando Datos Del SAF de Clima de EUMETSAT; Agencia Estatal de Meteorología: Madrid, Spain, 2014.

- ADRASE. Acceso a Datos de Radiación Solar En España. Available online: http://www.adrase.es/acceso-a-los-mapas/mapa-zona-peninsula.html (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Kalogirou, S.A. Solar Thermal Collectors and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 30, ISBN 3572240646. [Google Scholar]

- Ayompe, L.M.; Duffy, A. Analysis of the Thermal Performance of a Solar Water Heating System with Flat Plate Collectors in a Temperate Climate. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2013, 58, 447–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhilipan, J.; Vijayalakshmi, N.; Shanmugam, D.B.; Jai Ganesh, R.; Kodeeswaran, S.; Muralidharan, S. Performance and Efficiency of Different Types of Solar Cell Material—A Review. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 66, 1295–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benghanem, M.; Haddad, S.; Alzahrani, A.; Mellit, A.; Almohamadi, H.; Khushaim, M.; Aida, M.S. Evaluation of the Performance of Polycrystalline and Monocrystalline PV Technologies in a Hot and Arid Region: An Experimental Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.V.; Schmidt, O.; Gambhir, A.; Few, S.; Staffell, I. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment of Lithium-Ion Battery Chemistries for Residential Storage. J. Energy Storage 2020, 28, 101230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H.; Zhang, N.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Liu, J.; Song, W.; Zhao, Y.; Miao, Z. Strategies toward the Development of High-Energy-Density Lithium Batteries. J. Energy Storage 2024, 88, 111666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.M.N.U.; Rasul, M.G.; Sayem, A.S.M.; Mandal, N. Maximizing Energy Density of Lithium-Ion Batteries for Electric Vehicles: A Critical Review. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Jiang, M.; Tao, P.; Song, C.; Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Deng, T.; Shang, W. Temperature Effect and Thermal Impact in Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Review. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2018, 28, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez Fernández, R.; Castillo Campo, O. A Method Based on Circular Economy to Improve the Economic Performance of Second-Life Batteries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes, T.; Etxandi-Santolaya, M.; Eichman, J.; Ferreira, V.J.; Trilla, L.; Corchero, C. Procedure for Assessing the Suitability of Battery Second Life Applications after EV First Life. Batteries 2022, 8, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonraksa, T.; Pinthurat, W.; Wongdet, P.; Boonraksa, P.; Marungsri, B.; Hredzak, B. Optimal Capacity and Cost Analysis of Hybrid Energy Storage System in Standalone DC Microgrid. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 65496–65506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.A. The Significance of Considering Battery Service-Lifetime for Correctly Sizing Hybrid PV–Diesel Energy Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaleem, A.; Zaman, A.; Rajakaruna, S. Hydrogen at Home: The Current and Future Landscape of Green Hydrogen in Residential Settings. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2024, 72, 104058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knosala, K.; Langenberg, L.; Pflugradt, N.; Stenzel, P.; Kotzur, L.; Stolten, D. The Role of Hydrogen in German Residential Buildings. Energy Build. 2022, 276, 112480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Energy Council. Hydrogen Demand and Cost Dynamics; World Energy Council: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2023; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2023.

- Decourt, B.; Lajoie, B.; Debarre, R.; Soupa, O. Leading the Energy Transition: Hydrogen-Based Energy Conversion; SBC Energy Institute: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Haines, M.R.; Polman, E.A.; De Laat, J.C. Reduction of CO2 Emissions by Addition of Hydrogen to Natural Gas. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.K.; Ha, S.K. A Review on the Cost Analysis of Hydrogen Gas Storage Tanks for Fuel Cell Vehicles. Energies 2023, 16, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubilay Karayel, G.; Javani, N.; Dincer, I. A Comprehensive Assessment of Energy Storage Options for Green Hydrogen. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 291, 117311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amos, W. Costs of Storing and Transporting Hydrogen; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 1998.

- Carbotainer. 200 Bar Cylinder Bundles. Available online: https://www.carbotainer.es/200-bar-cylinder-bundle.php (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Hinnells, M. Combined Heat and Power in Industry and Buildings. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4522–4526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, S.S.; Lee, W.K.H.; Chan, A.H.S.; Tsang, S.N.H. The Economic and Environmental Evaluations of Combined Heat and Power Systems in Buildings with Different Contexts: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renau, J.; García, V.; Domenech, L.; Verdejo, P.; Real, A.; Giménez, A.; Sánchez, F.; Lozano, A.; Barreras, F. Novel Use of Green Hydrogen Fuel Cell-Based Combined Heat and Power Systems to Reduce Primary Energy Intake and Greenhouse Emissions in the Building Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, P.E.; Staffell, I.; Hawkes, A.D.; Li, F.; Grünewald, P.; McDowall, W.; Ekins, P. Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies for Heating: A Review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 2065–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneda, T.; Ono, Y.; Ikegami, T.; Akisawa, A. Technological Assessment of Residential Fuel Cells Using Hydrogen Supply Systems for Fuel Cell Vehicles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 26377–26388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, A.; Kudoh, Y. Performance of Residential Fuel-Cell-Combined Heat and Power Systems for Various Household Types in Japan. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 15412–15422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLay, J.D.; Brouwer, J.; Samuelsen, G.S. Experimental Results for Hybrid Energy Storage Systems Coupled to Photovoltaic Generation in Residential Applications. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 12130–12140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokar, J.; Virtič, P. The potential for integration of hydrogen for complete energy self-sufficiency in residential buildings with photovoltaic and battery storage systems. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 34566–34578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabana, P.; Tinaut, F.V.; Reyes, M.; Domínguez, J.I. Performance Evaluation of a Fuel Cell MCHP System under Different Configurations of Hydrogen Origin and Heat Recovery. Energies 2023, 16, 6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saaty, T.; Vargas, L. Models, Methods, Concepts & Applications of the Analytic Hierarchy Process; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; ISBN 978-1-4614-3596-9. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Torres, D.; Urdaneta Urdaneta, A.J.; De Oliveira-De Jesus, P. A Hierarchical Methodology for the Integral Net Energy Design of Small-Scale Hybrid Renewable Energy Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 52, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhammadi, H.; Alghailani, M.; Alkhzaimi, N.; Alsuwaidi, D.; Mayyas, A. Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methods for Selecting the Best Energy Storage Systems in Arid Regions. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 3575–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohekar, S.D.; Ramachandran, M. Application of Multi-Criteria Decision Making to Sustainable Energy Planning—A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2004, 8, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomczewski, A.; Mikulski, S.; Szymenderski, J. Application of the Analytic Hierarchy Process Method to Select the Final Solution for Multi-Criteria Optimization of the Structure of a Hybrid Generation System with Energy Storage. Energies 2024, 17, 6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto para la Diversificacion y Ahorro de la Energia (IDAE). Análisis Del Consumo Energético Del Sector Residencial En España; Instituto para la Diversificación y Ahorro de la Energía: Madrid, Spain, 2011.

- IDAE. Estructura Del Consumo Por Usos En El Año 2023. Available online: https://informesweb.idae.es/consumo-usos-residencial/informe.php (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- REE. The Spanish Electricity System; Red Eléctrica de España: Madrid, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Green Hydrogen Organisation. Green Hydrogen Standard: The Global Standard for Green Hydrogen and Green Hydrogen Derivatives Including Green Ammonia; Green Hydrogen Organisation: Genève, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R.L. Weibull Regression Models for Reliability Data. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 1991, 34, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.Y. Applications of the Extent Analysis Method on Fuzzy AHP. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1996, 95, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprova, N.T.; Zidan, R.; Rashid, A.R.M.H. Optimal Site Selection for Solar Farms Using GIS and AHP: A Literature Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial & Mechanical Engineering and Operations Management, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 26–27 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, L.; Solangi, Y.A. Strategic Renewable Energy Resources Selection for Pakistan: Based on SWOT-Fuzzy AHP Approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 52, 101861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, M.F.A.; Shafie, S.M.; Rahim, M.K.I.A. AHP Analysis on the Criteria and Sub-Criteria for the Selection of Fuel Cell Power Generation in Malaysia. J. Adv. Res. Fluid. Mech. Therm. Sci. 2022, 98, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, X.; Zhu, Y.; Qiu, L.; Cao, S. Research on the Problem of Solar Energy Storage System Based on AHP. E3S Web Conf. 2022, 352, 02002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acha, S.; Le Brun, N.; Damaskou, M.; Fubara, T.C.; Mulgundmath, V.; Markides, C.N.; Shah, N. Fuel Cells as Combined Heat and Power Systems in Commercial Buildings: A Case Study in the Food-Retail Sector. Energy 2020, 206, 118046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napoli, R.; Gandiglio, M.; Lanzini, A.; Santarelli, M. Techno-Economic Analysis of PEMFC and SOFC Micro-CHP Fuel Cell Systems for the Residential Sector. Energy Build. 2015, 103, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Chakraborty, I.; Bohre, A.K.; Kumar, P.; Agarwala, R. Sustainable Integration of Green Hydrogen in Renewable Energy Systems for Residential and EV Applications. Int. J. Energy Res. 2024, 2024, 8258624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroutaji, A.; Arjunan, A.; Robinson, J.; Wilberforce, T.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Olabi, A.G. PEMFC Poly-Generation Systems: Developments, Merits, and Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knosala, K.; Kotzur, L.; Röben, F.T.C.; Stenzel, P.; Blum, L.; Robinius, M.; Stolten, D. Hybrid Hydrogen Home Storage for Decentralized Energy Autonomy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 21748–21763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Cost of the system i (PSBB, PSHB, GSHC) | |

| Levelized cost of energy for the component j (solar panel, electrolyzer, fuel cell, hydrogen compressor, heat pump and power converters) in the system i | |

| Levelized cost of storing energy for the component j (battery pack, hydrogen storage and heat accumulator) in the system i | |

| r | Discount rate |

| T | System lifetime |

| Egt | Useful energy output per year t |

| EFi | Efficiency of the system i |

| Ect | Energy consumption from an external supplier per year t |

| Ece | Electrical energy consumption from the grid |

| EcH2 | Green hydrogen consumption from an external supplier |

| Ed | Household energy demand |

| Capacity factor of the system i | |

| Reliability of the system i. | |

| Characteristic lifespan of the component j in the system i | |

| System life expectancy | |

| β | Weibull model shape parameter |

| Use phase emissions of system i | |

| EMe | Emission factor of the electricity acquired from the grid |

| EMH2 | Emission factor of the green hydrogen acquired |

| SFi | Footprint ratio of the system i configuration |

| Footprint of the component j of the system i | |

| x | KPI value |

| Normalized KPI value | |

| Fuzzy number assigned to a KPI value | |

| l, m, u | The triplet l, m and u denote the smallest possible value, the most likely value, and the upper potential value, respectively, of a fuzzy number |

| M | Comparison matrix |

| CR | Consistency ratio of a comparison matrix M |

| CI | Consistency index |

| λmax | Maximum eigenvalue of comparison matrix |

| RI | Random index |

| W | Priority vector with components wi |

| T | Criteria matrix |

| Fuzzy priority vector | |

| Fuzzy comparison matrix | |

| De-fuzzy weight vector with components | |

| Sa | Overall score of the alternative a |

| Component | Type—Technology |

|---|---|

| Solar panels | Polycrystalline |

| Fuel cell | Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell—PEMFC |

| Electrolyzer | Unipolar Alkaline Electrolyzer |

| Hydrogen compressor | Diaphragm Compressor |

| Hydrogen storage | Type III—High-strength alloys of steel or aluminum fully wrapped with a composite liner |

| Battery pack | Li-ion (Lithium Iron Phosphate/Carbon—LFP/C) |

| DC—DC power converter | Buck-Boost Converter |

| DC—AC power converter | Bidirectional voltage source inverter (VSI) |

| Heat accumulator | Hot water tank |

| Heat exchanger | Liquid–liquid plate heat exchanger counterflow |

| Electric water heater | Electric immersion on-demand water heater |

| Criteria | KPI | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition | System Cost (SC) | The SC is evaluated using the Levelized Cost of Energy (LCOE) and Levelized Cost of Storage (LCOS) metrics. LCOE and LCOS express the lifetime cost of energy systems in terms of the cost per unit of energy delivered over their service life. Both are standardized metrics used to consistently evaluate and compare different energy generation and storage technologies. SC includes CapEx and OpEx. |

| Commercial Deployment (CD) | CD refers to the technology market availability and penetration, the number of competing suppliers in the market, technical support, and after-sales service. | |

| Fail-safety (FS) | FS refers to the measures put in place to guarantee the secure functioning of the system while reducing potential hazards to individuals, infrastructure, and the environment, based on the maturity of certifications and standards. | |

| Operation | Global Efficiency (EF) | EF refers to the ratio of useful energy output to the total energy consumed. EF considers the electric (EFe) and thermal efficiency (EFth). EFe refers to the ratio of useful electrical output power to the total electrical power consumed. Moreover, EFth measures the effectiveness of converting thermal energy (heat) into useful work. |

| Capacity Factor (CF) | CF represents the proportion of household energy demand is covered by the system. A higher capacity factor indicates that the system delivers power consistently to the load, reducing energy dependence on the electricity grid. | |

| System’s Reliability (SR) | SR refers to the expected probability that the system will perform within acceptable performance standards without failure over a specified period. | |

| Environmental | Use Phase Emissions (UPE) | UPE refers to the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions generated during the system’s operation. |

| System Footprint (SF) | SF takes into account the system dimensions. It is directly related to the system power and energy density. It is important to consider that it will be necessary to provide dedicated spaces in the building for all the components of the EGSSRB, depending on the system configuration. |

| Importance Level | Definition | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equal importance | Both nodes contribute equally to the objective |

| 3 | Weak importance of one over another | Slightly favors one node over another |

| 5 | Essential importance | Moderate favor one node over another |

| 7 | Strong or demonstrated importance | A node is favored strongly over another. Its dominance is demonstrated in practice. |

| 9 | Absolute importance | The evidence that favors one node over another is of the highest possible order of affirmation. |

| 2, 4, 6, 8 | Intermediate values between adjacent scales values | Intermediate values are used if necessary to refine the comparison. |

| AHP Scale | Fuzzy AHP Scale |

|---|---|

| 1 | (1, 1, 1) |

| 3 | (2, 3, 4) |

| 5 | (4, 5, 6) |

| 7 | (6, 7, 8) |

| 9 | (9, 9, 9) |

| Matrix Dimensions | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RI | 0 | 0 | 0.58 | 0.9 | 1.12 | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.41 |

| Configurations 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPI | Units 2 | PSBB | PSHB | GSHC |

| System cost | EUR/kWh | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.9 |

| Commercial deployment | unitless | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Fail-safety | unitless | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Global efficiency | % | 89.9 | 74.8 | 48.9 |

| Capacity factor | % | 72.5 | 82.5 | 84.8 |

| System reliability | % | 16 | 12 | 12 |

| Use phase emissions | kgCO2e/kWh | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.06 |

| System footprint | m2/kWh | 0.0042 | 0.0045 | 0.0004 |

| Configurations 1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| KPI | PSBB | PSHB | GSHC |

| System Cost | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| Commercial Deployment | 9 | 1 | 1 |

| Fail-safety | 9 | 1 | 5 |

| Global Efficiency | 9 | 6 | 1 |

| Capacity Factor | 1 | 7 | 9 |

| System reliability | 9 | 1 | 3 |

| Use Phase Emissions | 1 | 6 | 9 |

| System Footprint | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| PSBB | PSHB | GSHC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case A (Ranking) | 0.489 (1) | 0.147 (3) | 0.365 (2) |

| Case B (Ranking) | 0.416 (1) | 0.199 (3) | 0.385 (2) |

| Case C (Ranking) | 0.474 (1) | 0.164 (3) | 0.362 (2) |

| Criteria | Weights | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASE | SCN–1 | SCN–2 | SCN–3 | SCN–4 | SCN–5 | |

| Acquisition | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.33 | 0.28 |

| Operation | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.35 |

| Environmental | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.37 |

| PSBB | PSHB | GSHC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case A (Ranking) | 0.481 (1) | 0.141 (3) | 0.378 (2) |

| Case B (Ranking) | 0.391 (2) | 0.210 (3) | 0.399 (1) |

| Case C (Ranking) | 0.471 (1) | 0.169 (3) | 0.359 (2) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Castillo Campo, O.; Fernández, R.Á. Methodology for Evaluating and Comparing Different Sustainable Energy Generation and Storage Systems for Residential Buildings—Application to the Case of Spain. Energies 2025, 18, 5863. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215863

Castillo Campo O, Fernández RÁ. Methodology for Evaluating and Comparing Different Sustainable Energy Generation and Storage Systems for Residential Buildings—Application to the Case of Spain. Energies. 2025; 18(21):5863. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215863

Chicago/Turabian StyleCastillo Campo, Oscar, and Roberto Álvarez Fernández. 2025. "Methodology for Evaluating and Comparing Different Sustainable Energy Generation and Storage Systems for Residential Buildings—Application to the Case of Spain" Energies 18, no. 21: 5863. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215863

APA StyleCastillo Campo, O., & Fernández, R. Á. (2025). Methodology for Evaluating and Comparing Different Sustainable Energy Generation and Storage Systems for Residential Buildings—Application to the Case of Spain. Energies, 18(21), 5863. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215863