1. Introduction

In modern power systems, ensuring stability under small disturbances is a critical requirement for maintaining the secure and continuous operation of the grid. As renewable generation, power electronics, and distributed resources continue to reshape the grid, the challenge of guaranteeing reliable operation has grown considerably. Small-signal stability (SSS) analysis has therefore become a cornerstone methodology for evaluating the ability of the system to withstand perturbations around its operating point. Within this framework, modal analysis plays a fundamental role; it enables the identification of poorly damped oscillatory modes and provides insight into their dynamic impact on the grid [

1]. A particularly valuable complement to this analysis is the computation of modal residues, which quantify the relative influence of each mode on the system variables [

2]. Residues have been shown to guide the design, placement, and tuning of damping controllers such as Power System Stabilizers (PSSs) [

3] and Static Frequency Converters (SFCs) [

4,

5].

In recent years, the growing penetration of inverter-based renewable energy sources has significantly altered the dynamic behavior of power systems. The displacement of conventional synchronous machines has reduced overall system inertia, leading to faster frequency excursions and the emergence of new oscillatory phenomena. Real-world observations have confirmed that these effects can manifest as low-frequency inter-area oscillations. For instance, the Nordic power system experienced an oscillation around 0.3 Hz in June 2021, which was linked to variations in kinetic energy associated with a high share of renewable generation [

6].

Similar behaviors have been reported in hydrothermal systems. For instance, in the Ecuador–Colombia interconnected grid, a persistent inter-area oscillation in the 0.4–0.5 Hz range has been observed under weakly damped conditions. During an event in September 2011, the disconnection of 230 kV tie lines triggered oscillations in active power, frequency, and phase angles, highlighting the sensitivity of the system to large disturbances [

7]. These examples illustrate that the transition toward low-inertia, renewable-dominated systems increases the likelihood of poorly damped electromechanical modes, reinforcing the need for systematic modal analysis and control-oriented indices such as residues.

The increasing complexity of power systems is accompanied by a proliferation of monitoring and control devices in both real-time operation and simulation environments. As a result, the analysis of high-dimensional datasets has become indispensable, requiring the use of advanced matrix-based techniques [

1,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. Complementary to these matrix-based approaches, advanced signal decomposition methods have also been proposed for real-time oscillation mode estimation from synchrophasor data [

14]. In interconnected grids, inter-area oscillations often emerge in the 0.1–3 Hz frequency range, and these modes are typically weakly or negatively damped [

8,

15]. Such oscillations may be triggered by faults, switching events, or sudden variations in load and generation, and are frequently associated with insufficient damping, improper control tuning, or inadequate system design [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Identifying and mitigating these critical oscillations is therefore a priority for Independent System Operators (ISOs), as grid codes generally require all oscillatory modes to be adequately damped, often with a minimum damping ratio of 10% [

11].

From a technical perspective, small-signal stability is evaluated by linearizing the differential-algebraic equations (DAEs) of the system around a steady-state operating point. The resulting state matrix, or Jacobian, provides the eigenvalues and eigenvectors that define oscillation frequencies and damping ratios. While participation factors indicate which state variables are most involved in a given mode, residues go further by combining the information of left and right eigenvectors with input–output mappings. This property makes residues particularly effective for assessing both controllability and observability, which is crucial for residue-based PSS tuning [

1,

11].

In this context, DIgSILENT PowerFactory has emerged as one of the most widely used platforms for modeling, simulating, and analyzing power systems [

21]. Beyond standard functions such as power flow and time-domain simulations, it offers advanced capabilities for modal analysis and SSS assessment. Its scripting environment, the DIgSILENT Programming Language (DPL), enables automation of studies and direct access to internal matrices, creating opportunities for advanced applications such as residue computation [

21]. Nevertheless, PowerFactory does not directly compute residues, and while exporting data for external processing (e.g., MATLAB version R2024a) is possible, this approach lacks the efficiency and integration needed for systematic scenario-based studies.

This paper addresses these gaps by proposing a residue-based methodology that directly exploits the internal analysis matrices of PowerFactory through the DPL. The contributions of this work can be summarized as follows:

A DPL-based framework is developed to automate the computation of modal residues, eliminating the need for external data processing and ensuring seamless integration into PowerFactory workflows.

The framework enables efficient and systematic small-signal stability assessments under diverse operating conditions, providing quantitative indices of controllability and observability for oscillatory modes.

The methodology is applied to residue-guided tuning of PSSs, demonstrating its ability to displace critical eigenvalues into the stable region and significantly enhance damping performance in both benchmark and large-scale interconnected systems.

By embedding residue analysis directly into PowerFactory workflows, the proposed approach eliminates the reliance on external processing tools, streamlines the execution of modal studies, and enhances the reproducibility of results. In doing so, it equips both system operators and researchers with a practical and scalable framework for designing and optimizing control strategies, thereby addressing the growing challenges of ensuring stability in increasingly complex and interconnected power systems.

In recent years, several studies have highlighted the increasing relevance of modal analysis for enhancing power system damping and optimizing control allocation. Works such as [

22,

23] have emphasized the need to automate critical stages of power system dynamic analysis, reducing reliance on manual and ad hoc procedures. Building upon this line of research, the present study advances toward the integrated computation of modal residues directly within DIgSILENT PowerFactory, thereby enabling the systematic translation of modal indices into practical, scalable decisions for oscillation damping and controller placement.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents the mathematical framework for residue computation, including the state-space formulation and the definition of controllability, observability, and modal residues.

Section 3 introduces the methodology for automating residue computation within DIgSILENT PowerFactory.

Section 4 reports simulation results from the Two-Area Kundur Test System and the reduced New York–New England power grid, validating the effectiveness and scalability of the approach.

Section 5 examines the implications of the results, and

Section 6 summarizes the main contributions and outlines future research directions.

2. Mathematical Framework for Residue Computation

This section introduces the mathematical framework for residue computation in power systems. Starting from the characterization of oscillatory modes, the system is represented in a linearized state-space form, where eigenvalues and eigenvectors define modal frequencies and damping. Based on controllability and observability indices, residues are then formulated as quantitative measures of a mode’s sensitivity to control, providing the theoretical foundation for the methodology proposed in this work.

During the operation of power systems, low-frequency oscillations frequently arise and are typically classified into two main categories: local modes and inter-area (or wide-area) modes. These phenomena have been extensively studied in the literature and can be summarized as follows [

1,

8,

9,

10].

Local oscillation modes: Local oscillations occur when individual synchronous machines within the same area swing against each other, usually within the frequency range of 1–2 Hz. Since they are concentrated in a limited geographical region, they can often be effectively monitored using local measurements. In practice, relatively simple control strategies are sufficient to mitigate them. A widely adopted solution is the deployment of PSSs, which provide supplementary control signals to generator excitation systems, thereby increasing the effective damping of these modes.

Inter-area oscillation modes: Inter-area oscillations, in contrast, emerge when coherent groups of synchronous machines in one region oscillate against groups in another. These modes are generally associated with heavily loaded or congested transmission corridors and typically occur at lower frequencies, usually between 0.1 and 1 Hz. The larger equivalent inertia of aggregated machine groups and the higher electrical impedance separating them contribute to their slow oscillatory behavior. Inter-area oscillations pose a more severe threat to system stability, particularly in large interconnected grids.

Compared to local modes, inter-area oscillations are more challenging to detect and control. Their low observability and limited controllability make damping improvement a significant technical hurdle. Since they originate from the dynamic interactions of large groups of generators across wide geographical areas, these oscillations can compromise both system reliability and security. Moreover, without a comprehensive system-wide perspective, operators may find it difficult to implement effective strategies, not only to suppress local oscillations but also to guarantee sufficient damping of inter-area modes.

From a control theory perspective, the dynamic behavior of nonlinear systems depends on their parameters, particularly those associated with energy storage, energy transfer, and the magnitude of external disturbances. Power systems, being inherently large-scale and nonlinear, are therefore prone to recurrent low-frequency oscillations during normal operation. To study small-signal stability, the system can be linearized around an equilibrium point. Assuming the state vector can be expressed as

, where

is the steady-state operating point and

is a small deviation, the resulting linearized model takes the following state-space form [

8]:

where

is the state vector as a function of time (e.g., rotor angles, rotor speeds, excitation states),

is the input vector representing time-varying system inputs (e.g., control actions or disturbances), and

is the output vector containing measurable signals (e.g., bus voltages or monitored quantities). The notation

denotes the time derivative of the state vector. The matrices

,

,

, and

represent the system dynamics (state matrix), input controllability, output observability, and direct input–output feedthrough, respectively.

The eigenvalues of the state matrix

, denoted as

, are obtained by solving the following equations:

and they are fundamental to the analysis of system stability and dynamic performance. For each eigenvalue

, there exist two associated eigenvectors: the right eigenvector

, which is a column vector with the same dimension as the state vector, and the left eigenvector

, usually represented as a row vector. These eigenvectors enable the decomposition of system dynamics into independent modal components and thus play a central role in modal analysis [

1].

Each eigenvalue in (

2) and (

3) has the form

, where the real part

defines the modal damping and the imaginary part

defines the oscillation frequency. From these quantities, the damping ratio,

, and the oscillation frequency in Hertz,

, are obtained, respectively, as [

1,

10]

The left and right eigenvectors, combined with the input matrix

and the output matrix

, allow the evaluation of modal controllability and observability. Specifically, the controllability index of the

k-th mode with respect to the

p-th input is defined as [

24,

25]

where

is the left eigenvector of the

k-th mode and

is the

p-th column of the input matrix

. Physically,

expresses how effectively the control input

p can excite the mode

k; higher magnitudes indicate stronger controllability.

Similarly, the observability index of the

k-th mode with respect to the

q-th output is given by

where

is the right eigenvector associated with the

k-th mode and

is the

q-th row of the output matrix

. This coefficient quantifies how strongly the dynamics of mode

k appear in the output signal

q; thus, large values denote high observability.

Under these definitions, the residue associated with the

k-th mode—for the transfer function between the

p-th input and the

q-th output—is expressed as

The complex residue

represents the combined effect of controllability and observability. A high magnitude

implies that mode

k is both easily excited and easily detected, making it highly sensitive to feedback control. Conversely, if

, the mode is uncontrollable, unobservable, or both.

The residue can be expressed in polar form as

where

is the phase angle of the residue. This angle indicates the departure direction of the root locus from the pole and defines the required phase compensation for effective damping.

Under feedback, the displacement of the

i-th eigenvalue can be approximated as [

26]

where

is the complex loop gain,

is the open-loop eigenvalue, and

is the shifted eigenvalue after feedback. Decomposing the shift into its real and imaginary parts gives

where

and

represent the changes in damping and oscillation frequency, respectively. For negative feedback with

, choosing the controller phase

ensures that the eigenvalue moves leftward in the complex plane, thereby increasing the damping ratio of the mode.

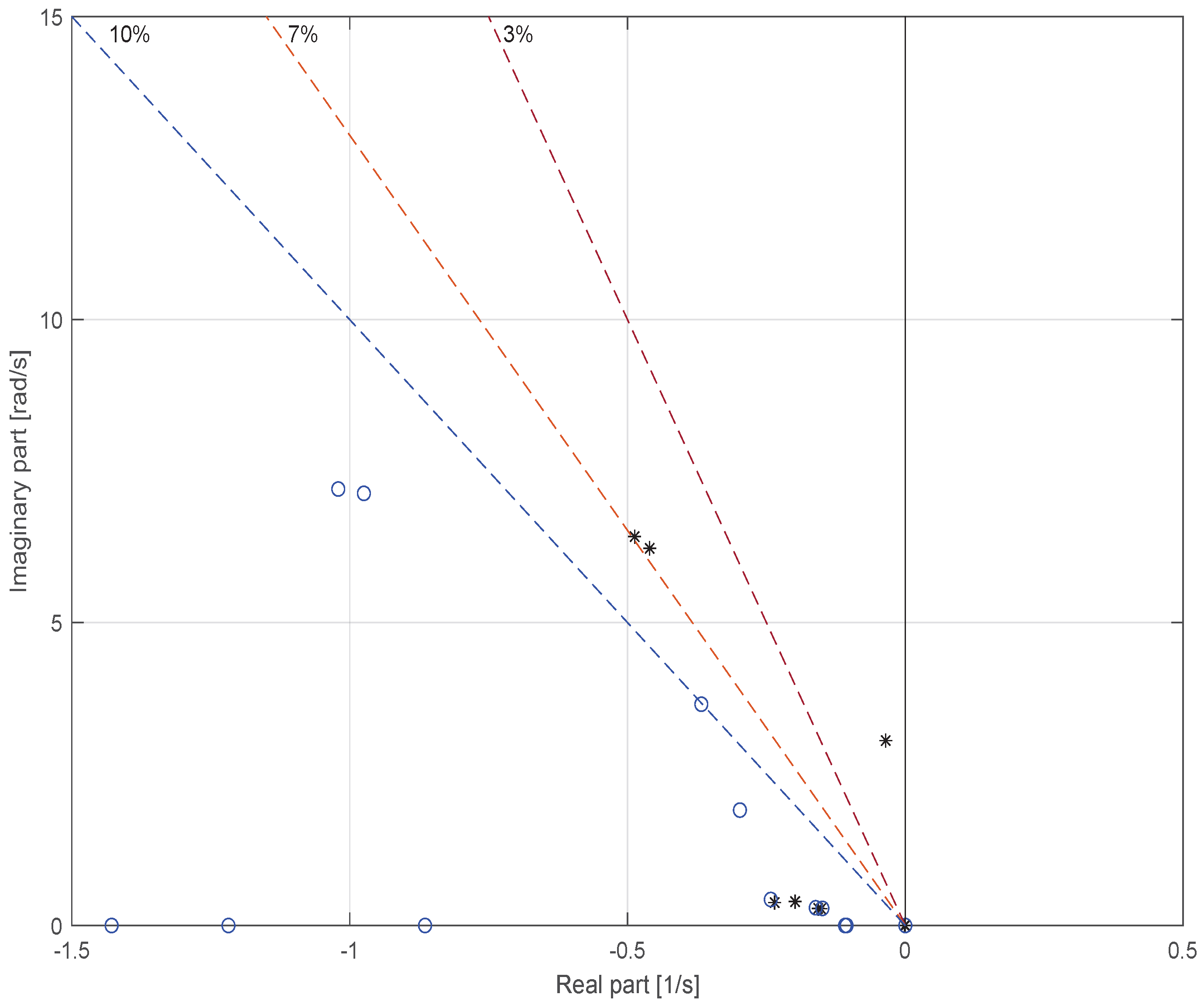

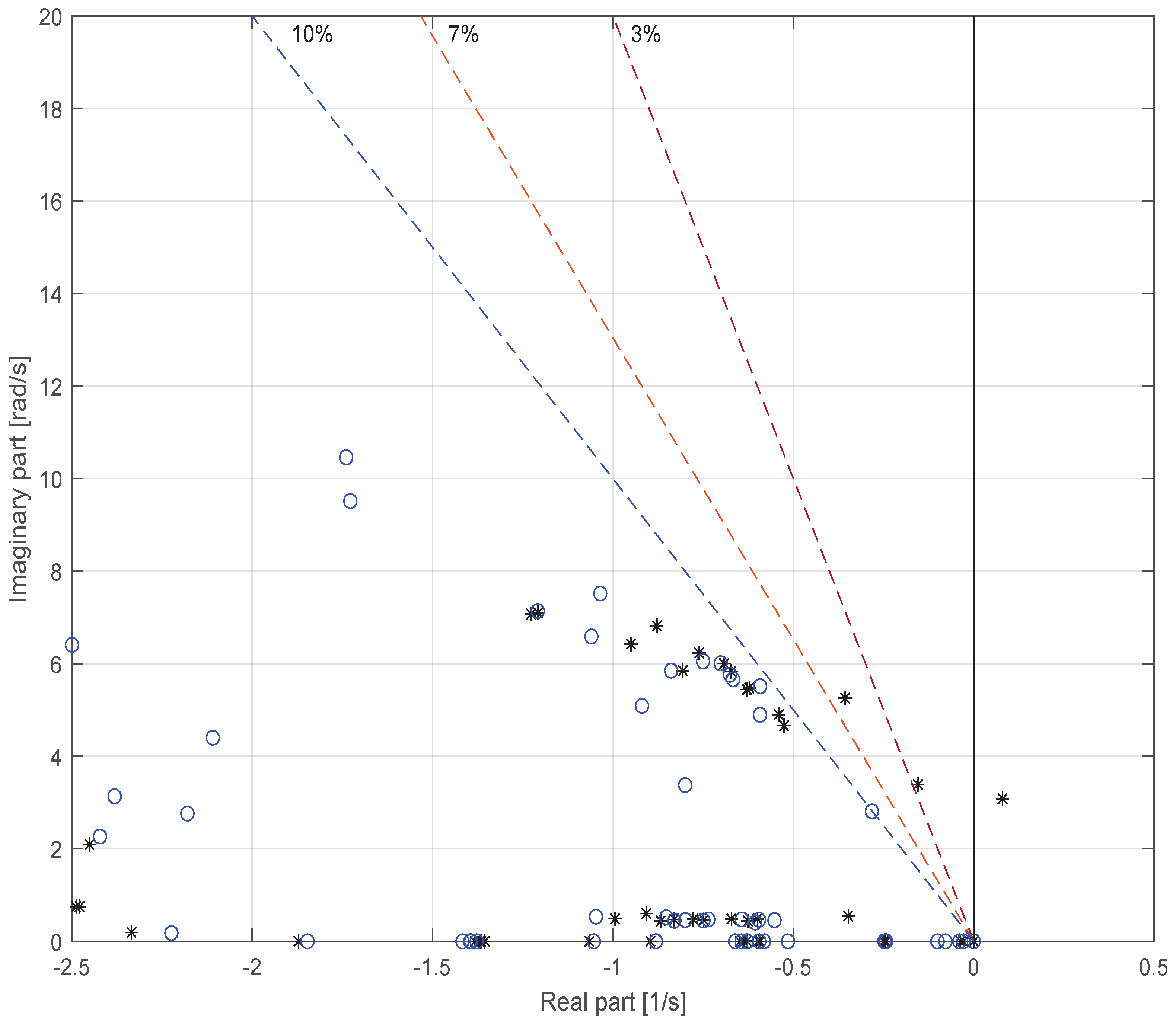

This behavior is illustrated in

Figure 1, where the phase compensation modifies the eigenvalue trajectory of the oscillatory mode, displacing it into the stable region and thereby improving the damping ratio [

26].

From (

8), it follows that the residue

quantifies the sensitivity of the eigenvalue associated with the state matrix

to specific input–output channels. This information is valuable for identifying which inputs are most effective for control action and feedback, thereby guiding the design and placement of stabilizing devices. In commercial power system analysis tools, such as DIgSILENT PowerFactory, the state matrix

, its eigenvalues, and the corresponding eigenvectors are typically available; however, the input and output matrices

and

are not directly accessible.

To overcome this limitation, ref. [

17] proposed a methodology for constructing the matrices

and

within the DPL environment. By reconstructing these matrices, it becomes possible to compute residues directly from the available modal information, enabling the evaluation of system controllability from relevant inputs such as generators equipped with PSS devices.

To construct the matrices and , the first step is to extract the state matrix from the modal analysis results. Unlike , which is unique for a given operating point, the matrices and depend on the choice of system inputs and outputs.

In the second step, the columns of

are determined by evaluating the variation of the state vector

in response to perturbations in selected inputs. Specifically, the

i-th column

of

can be obtained by applying a perturbation in active power injection at bus

i. The perturbed system dynamics can be expressed as [

27]

where

is the deviation in state variables and

is the perturbation at the

i-th input channel.

Assuming a unit-step input

applied at

with

for

, the solution of (

12) using Euler’s forward approximation is obtained as

Since and , a sufficiently small time step (e.g., s) ensures that the approximation error is negligible. This step size was selected through a trial-and-error comparison between the responses of the full nonlinear model and its linearized counterpart.

In the third step, the output matrix is constructed according to the selected system outputs. Each row corresponds to a monitored generator, with zeros in all positions except for a single entry equal to one in the column associated with the generator’s output variable (e.g., rotor speed). This formulation enables the mapping of the full state vector to the measured outputs .

Once and are obtained, and the left and right eigenvectors associated with the critical mode are identified, the corresponding residues can be computed accurately, thereby allowing the assessment of controllability and observability of oscillatory modes from relevant inputs such as generators equipped with PSS devices.

3. Automated Residue Computation for Modal Analysis in PowerFactory

This section presents the proposed methodology for computing residues from the modal analysis results of a power system model implemented in DIgSILENT PowerFactory.

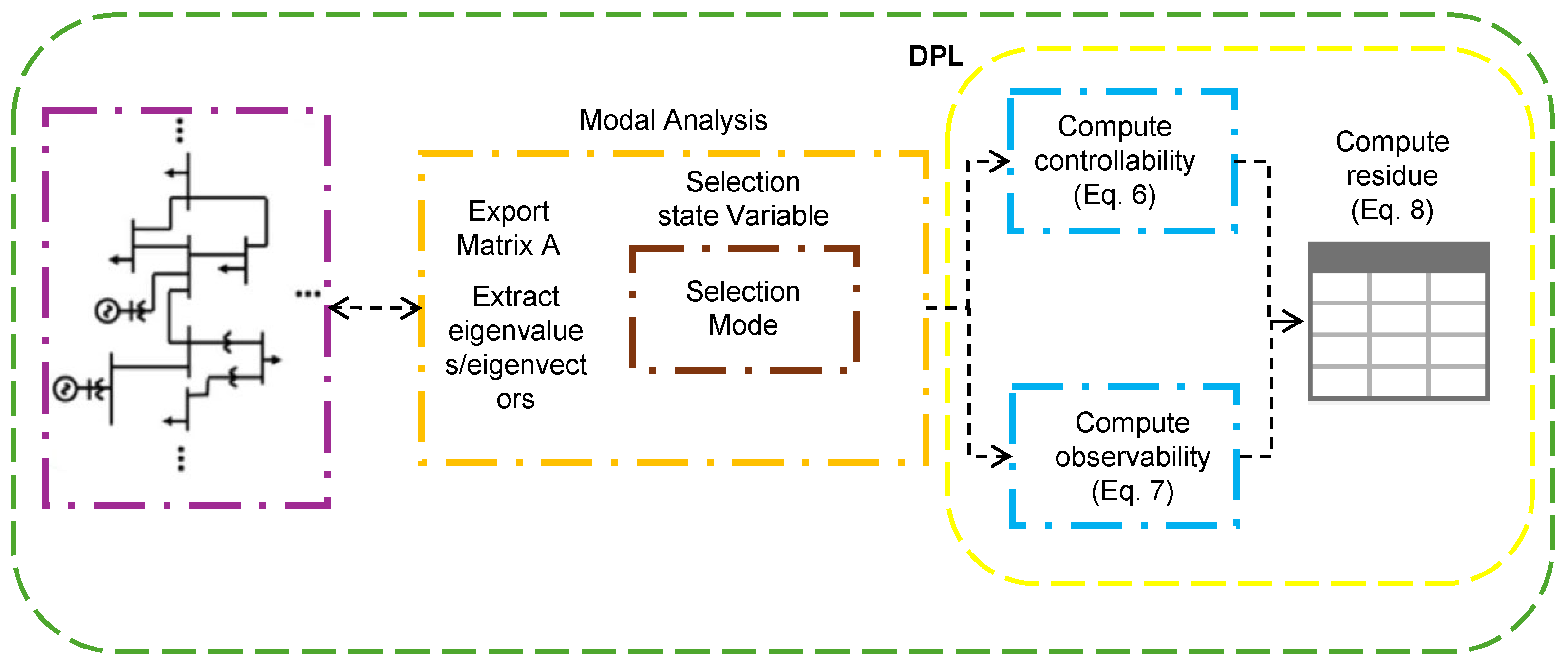

As discussed in the previous section, the computation of residues requires access to the state matrix

together with the associated eigenvalues, left eigenvectors, and right eigenvectors. Although DIgSILENT PowerFactory does not directly provide residue calculations, it offers all the necessary components to implement them through its scripting environment. The developed procedure leverages PowerFactory’s internal data export and modal analysis capabilities, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

The process begins by extracting the state matrix from the small-signal model using PowerFactory’s Modal Analysis tool. The matrix is exported in .mtl format, accompanied by an index file (VariableToIdx_Amat.txt) that maps each state variable to its matrix position. Simultaneously, the eigenvalues and eigenvectors are retrieved from the modal analysis module. These quantities constitute the mathematical foundation for modal controllability, observability, and residue evaluation.

A dedicated DPL (DIgSILENT Programming Language) script automates the subsequent steps, as outlined in the flowchart. First, the script selects the desired oscillation mode and corresponding state variables. It then computes the controllability coefficients and observability coefficients . Finally, residues are computed for each input–output pair and stored in a structured data table for post-processing. This implementation avoids external data manipulation, providing an integrated, repeatable, and scalable residue analysis workflow directly within PowerFactory.

Figure 2 summarizes the overall algorithm: from matrix and eigenvector extraction, through DPL-based computation of controllability and observability, to automated residue assembly. The process serves as a foundation for residue-guided controller tuning, enabling systematic analysis of mode controllability and damping effectiveness within the same simulation environment.

Building on these capabilities, a custom script was developed in the DPL to automate residue computation.

To perform modal analysis and extract the required data, the PowerFactory objects ComMod* and ComInc* must be configured. These objects manage the export of state-space matrices (such as ), eigenvalues, and eigenvectors to a user-defined script (Algorithm 1). The algorithm initializes the study case by opening the project folder, retrieving cases, and activating the selected one. Next, ComInc computes the initial operating point, while ComMod is set to run the modal analysis. Export flags are then defined; for example, Modal.iSysMatMat=1 exports , Modal.iEvMat=1 and Modal.iREVMat=1 export right and left eigenvectors, and Modal.dirMat=path specifies the output directory. Finally, Initial.Execute() and Modal.Execute() are called to obtain the numerical data needed for residue computation.

PowerFactory uses a color-coded syntax in DPL: black for user-defined variables, green for comments, red for user input text and commands, and blue for internal DPL functions. Each instruction must be terminated with a semicolon (;) to ensure proper execution.

| Algorithm 1 DPL script for modal analysis and selection of output matrices |

- 1:

! Section defined type variables - 2:

string path; - 3:

set StudyCases; - 4:

object Folder,Case,Initial,Modal;

- 5:

! Section defined study case of grid - 6:

Folder = GetProjectFolder(study); - 7:

StudyCases = Folder.GetContents(*.IntCase); - 8:

StudyCases.SortToName(0); - 9:

Case = StudyCases.First(); - 10:

Case.ShowFullName(); - 11:

Case.Activate(); - 12:

Case.ShowFullName();

- 13:

! Defined object by - 14:

Initial = GetCaseCommand(ComInc); ▹ !calculation initial conditions - 15:

Modal = GetCaseCommand(ComMod); ▹ !modal analysis - 16:

path =’D:\Taller Small-Signal\Clase Residuo’;

- 17:

! Section by vector and matrix of modal analysis - 18:

Modal:iLeft = 0; - 19:

Modal:iRight = 0; - 20:

Modal:iPart = 0; - 21:

Modal:iSysMatMat = 1; - 22:

Modal:iEvMat = 1; - 23:

Modal:iREVMat = 1; - 24:

Modal:iEVMat = 1; - 25:

Modal:iPartMat = 0; - 26:

Modal:dirMat = path;

- 27:

! Execution of simulation of modal analysis - 28:

Initial.Execute(); - 29:

Modal.Execute();

|

Once the modal analysis data has been exported, the input matrix

is built by simulating active power injections at selected buses. The target bus is specified with the general selection command

SetSelect*. The

i-th column of

is obtained by applying a unit step in active power—modeled as a 100 MW load increase—at the corresponding bus, as defined in (

13). This perturbation is introduced through a manually created

EvtSwitch* event linked to a mobile load connected to the selected terminal element (

ElmTerm*). After linking the load, the initial conditions (

ComInc*) and the dynamic simulation (

ComSim*) are executed to capture the system response. By superposition, the full matrix

is assembled by repeating this procedure for each bus in the system.

Algorithm 2 shows the implementation of this process in DPL. The first section declares the required variables and initializes objects such as study cases, events, and results containers. Then, the script imports the mapping file VariableToIdx_Amat.txt, which links state variables to the indices of matrix , and configures simulation parameters. Next, the Algorithm defines the switching event used to apply the power perturbation and retrieves the network terminals (ElmTerm*) that serve as candidate buses. In the construction phase, the script iteratively reads variable indices, extracts simulation results, and computes incremental changes in the state vector caused by the perturbation. Finally, these increments are normalized with respect to the applied step and stored as entries of through the MatrixB.Set command. This procedure guarantees that each column of accurately represents the controllability of the system with respect to active power injections at the corresponding bus.

For large-scale systems, the construction of matrix through per-input perturbations should be restricted to a filtered subset of candidate actuators. In such cases, normalization of the resulting controllability and observability terms is recommended to enhance numerical robustness across states and operating points.

To ensure dimensional consistency between the simulated perturbations and the linearized state-space formulation in (

1), each column of the input matrix

was explicitly normalized by the amplitude of the applied active-power step. The formulation adopted is

where

represents the incremental state deviation and

corresponds to the temporary active-power increase applied at the selected bus. This normalization guarantees that

preserves the correct physical units and remains compatible with the state-space model

.

The 100 MW perturbation was chosen as a practical compromise between ensuring numerical observability and maintaining operation within the linear region around the steady-state point. Across all buses tested in the benchmark systems, the induced rotor-angle deviations remained below , and rotor-speed deviations were less than p.u., confirming that the system response lies firmly within the small-signal regime. Consequently, the linearization underlying the modal formulation remains valid, and the computed entries faithfully represent the system’s controllability coefficients.

To validate the linearity assumption, a sensitivity analysis was performed using smaller perturbations of 10 MW and 20 MW. The resulting columns of exhibited nearly proportional scaling with the applied step magnitude, with deviations below 1% across all tested buses. The corresponding eigenvalues showed frequency variations smaller than 0.01 Hz and damping-ratio deviations below 0.001%, confirming that the system dynamics scale linearly within this range.

These results demonstrate that the 100 MW perturbation is sufficiently small to preserve linearity, yet large enough to overcome numerical precision limits within the DPL environment. Therefore, the resulting input matrix

is dimensionally consistent, numerically stable, and representative of the system’s controllability characteristics under small disturbances.

| Algorithm 2 DPL Script for Matrix B Construction |

- 1:

! Section defined type variables - 2:

string path,str,input description,s,file1; - 3:

set terms,events; - 4:

object event,term,node,switch,Results,inicial,sim,inputs,MatrixB;

- 5:

! Selection elements - 6:

file1 = ‘VariableToIdx_Amat.txt’; - 7:

s = sprintf(‘%s\\%s’,path,file1); - 8:

inicial = GetCaseCommand(‘ComInc’); - 9:

sim = GetCaseCommand(‘ComSim’); - 10:

MatrixB = GetCaseObject(‘MatrixB.IntMat’); - 11:

MatrixB.Init(1,1);

- 12:

! Calculations - 13:

inicial:p resvar = Results; - 14:

inicial:dtgrd = 0.0001; - 15:

inicial:tstart = 0; - 16:

inicial:dtout = 0.0001; - 17:

sim:stop = 0.0001; - 18:

events = inputs.GetContents(); - 19:

event = events.First(); - 20:

event:time = 0; - 21:

event:i switch = 1; - 22:

terms = SEL.GetAll(’ElmTerm’); - 23:

terms.SortToName(0); - 24:

term = terms.First();

- 25:

! Construction matrix B - 26:

MatrixB = GetCaseObject(’MatrixB.IntMat’); - 27:

fopen (s,‘r’,0); - 28:

while (ierr > −1) { - 29:

if(count = 1){ - 30:

ierr = fscanf(0,‘%d’,index); - 31:

count = count + 1 ;}

- 32:

if (count > 1) { - 33:

while(count > 1.and.count < 4.and.ierr > −1) { - 34:

ierr = fscanfsep(0,‘%s’,path,”,0); - 35:

if (count < 3) { - 36:

count = count + 1; - 37:

i1 = strstr(path,‘Grid Name’); - 38:

str1 = strcpy(path,i1,120); - 39:

i2 = strstr(str1,‘ ’); - 40:

str2 = strcpy(str1,0,i2); - 41:

Filter.objset = str2; - 42:

elements = Filter.Get(); - 43:

element = elements.First(); - 44:

} - 45:

else { - 46:

count = 1; - 47:

var = sprintf(s,‘%s’,path); - 48:

col = ResIndex(Results,element,var); - 49:

GetResData(aux_ini,Results,row,col); - 50:

GetResData(aux end,Results,nval-1,col); - 51:

aux = (aux end-aux ini)/txx; - 52:

MatrixB.Set(index,column,aux); - 53:

Results.Flush(); }}}}

- 54:

fclose(0);

|

The integration time step was fixed at s with a total simulation horizon of 0.1 ms. This setting was selected after convergence tests in which decreasing by one order of magnitude produced eigenvalue and damping-ratio variations below 0.05%.

The chosen step size therefore provides sufficient numerical resolution for all generator buses and operating points while avoiding unnecessary computational cost.

Because the modal residue computation relies on the linearized Jacobian matrices exported by ComMod, the integration step primarily affects transient verification runs and not the modal results themselves. Across all test cases, no stiffness-related divergence or integration failure was observed.

For the output matrix , the system considers the rotor speed of all synchronous machines as the primary output variables, since PSSs are implemented within the generator excitation systems. Each row of corresponds to a generator and contains only zeros, except for a single entry with value “1” at the position associated with the generator’s speed state. This assignment is illustrated in Algorithm 3.

In Algorithm 3, the script reads the file VariableToIdx_Amat.txt, which maps state variables to their indices, and scans each entry until it identifies those labeled as speed. When such a variable is found, the index is stored in the auxiliary matrix Cindex, and the association between generator and state variable is reported through the fprintf command. Once all relevant variables are identified, the script initializes the output matrix with the appropriate dimensions, and each speed state is assigned a unit entry in the corresponding row, while the rest of the elements remain zero. This procedure ensures that correctly maps the system states to measurable outputs, enabling the analysis of modal observability from generator speeds. Nevertheless, other output variables may be selected depending on the specific application or analysis requirements.

The same procedure applies to non-generator actuators (FACTS/HVDC/IBR): construct matrix B from the device’s control inputs and define matrix with measurements aligned to the targeted oscillation that permit computation for residue.

In DIgSILENT PowerFactory, modal module (ComMod) exports the state-to-index map in the text file VariableToIdx_Amat.txt. In our implementation, the output vector y selects rotor speed for each synchronous generator by matching the literal state label speed in that file. During execution, it records the full object name of each machine and exact speed state index used to place the unit entry in C. Example of Kundur system: G1.speed, G2.speed, G3.speed, G4.speed. This guarantees that any user can reconstruct our row selectors directly from PowerFactory users’ exported names without ambiguity.

The residue is then computed following the relationships defined in (

6)–(

8), with Algorithm 4 implementing these operations explicitly. First, the script reads the file

EVals.mtl, which contains the system eigenvalues, and calculates their damping ratios, storing them in

MEdamp. Modes with insufficient damping (e.g.,

) are identified and indexed in

Mindx as critical modes of interest. For each selected mode, the corresponding left and right eigenvectors are retrieved from the files

lEV.mtl and

rEV.mtl, respectively, and their real and imaginary components are stored in

Mreal and

Mimag.

With the input matrix

and the output matrix

already constructed as described in

Section 2, the script proceeds to evaluate modal controllability and observability by multiplying the eigenvectors with the appropriate columns of

and rows of

. These calculations directly implement the definitions in (

6) and (

7), with the magnitude and angle of each term stored in

Mctrl_m/

Mctrl_ang and

Mobser_m/

Mobser_ang, respectively. Finally, the residue for each mode and input–output pair is obtained by combining the controllability and observability results according to (

8), with the residue magnitude recorded in

MResidue_m and its phase in

MResidue_ang. This systematic procedure not only ensures a consistent link between modal theory and practical implementation in PowerFactory, but also provides the necessary data for residue-based analysis and controller tuning in power system stability studies.

| Algorithm 3 DPL Script for Matrix C Construction |

- 1:

! Section defined type variables - 2:

string var,str1,str2,output description,s,file1,s2,file2; - 3:

set elements; - 4:

object element,Cindex,MatrixC; - 5:

int ierr,count,i1,i2,comp,a,m,row,col; - 6:

double index,aux;

- 7:

! Selection elements - 8:

ier = −1; - 9:

count = 1; - 10:

aux = 1; - 11:

file1 = ‘VariableToIdx_Amat.txt’; - 12:

s = sprintf(‘%s\\%s’,path,file1); - 13:

Cindex = GetCaseCommand(‘Cindex.IntMat’); - 14:

Cindex.Init(1,1);

- 15:

! Construction matrix C - 16:

fopen(s,‘r’,0); - 17:

while (ierr > −1) { - 18:

if(count = 1){ - 19:

ierr = fscanf(‘0,%d’,index); - 20:

count = count + 1;}

- 21:

if(count > 1) { - 22:

while(count > 1.and.count < 4.and.ier > −1) { - 23:

ier = fscanfsep(0,‘%s’,path,“”,0); - 24:

if(count < 3) { - 25:

count = count + 1; - 26:

i1 = strstr(path,‘Grid Name’); - 27:

str1 = strcpy(Dpath,i1,120); - 28:

i2 = strstr(str1,‘ ’); - 29:

str2 = strcpy(str1,0,i2); - 30:

} - 31:

else { - 32:

comp = strcmp(path,‘speed’); - 33:

if(comp = 0){ - 34:

Cindex.Set(aux,1,index); - 35:

fprintf(1,‘Output %d is state variable number %d from%s’,aux,index,str2); - 36:

aux = aux + 1;}}}}}

- 37:

fclose(0); - 38:

MatrixC = GetCaseCommand(‘MatrixC.IntMat’); - 39:

row = Cindex.NRow(); - 40:

col = index − 2; - 41:

MatrixC.Init(row,col); - 42:

for(m = 1; m <= row + 1; m = m + 1){ - 43:

a = Cindex.Get(m,1); - 44:

MatrixC.Set(m,a,1); - 45:

}

|

| Algorithm 4 DPL Script for Residue Calculation (Part I) |

- 1:

! Section defined type variables - 2:

double b, real, imag, damp, ar, ai, sumr, sumi, ctl_m, ctl_ang, obser_m, obser_ang,res_m, double res_ang; - 3:

int h, error, mode, x, y, colum, row, count, ierr, n, nE, nI, nL, nb, nC, col, rowI, rin; - 4:

object B, C, Mindex, MEdamp, Mreal, Mimag, Mctrl_m, Mctrl_ang, Mobser_m, Mobser_ang, MResidue_m, MResidue_ang;

- 5:

! Selection elements - 6:

file1 = ‘EVals.mtl’; file2 = ‘lEV.mtl’; file3=‘rEV.mtl’; EVals = sprintf(‘%s\\%s’,path,file1); 1EV = sprintf(‘%s\\%s’,path,file2); rEV = sprintf(‘%s\\%s’,path,file3); - 7:

B = GetCaseCommand(‘MatrixB.IntMat’); - 8:

C = GetCaseCommand(‘Cindex.IntMat’); - 9:

Mindx = GetCaseCommand(‘Mindx.IntMat’); - 10:

MEdamp = GetCaseCommand(‘MEdamp.IntMat’); - 11:

Mreal = GetCaseCommand(‘Mreal.IntMat’); - 12:

Mimag = GetCaseCommand(‘Mimag.IntMat’); - 13:

Mctrl_m = GetCaseCommand(‘Mctrl_m.IntMat’); - 14:

Mctrl_ang = GetCaseCommand(‘Mctrl_ang.IntMat’); - 15:

Mobser_m = GetCaseCommand(‘Mobser_m.IntMat’); - 16:

Mobser_ang = GetCaseCommand(‘Mobser_ang.IntMat’); - 17:

MResidue_m = GetCaseCommand(‘MResidue_m.IntMat’); - 18:

MResidue_ang = GetCaseCommand(‘MResidue_ang.IntMat’);

- 19:

! Selection respective eigenvalue - 20:

fopen(EVals,‘r’,0); - 21:

while(ierr > −1) { - 22:

if (colum = 1){ierr = fscanf(0,‘%d’,x); colum = 2; } - 23:

if (colum = 2){ierr = fscanf(0,‘%d’,y); colum = 3;} - 24:

if (colum = 3){ierr = fscanf(0,‘%d’,real); colum = 4;} - 25:

if (colum = 4){ierr = fscanf(0,‘%d’,imag); colum = 1;} - 26:

if (ierr > −1) { damp=real/sqrt(real*real+imag*imag); - 27:

MEdamp.Set(n,1,damp); n = n + 1;}} - 28:

fclose(0);

- 29:

nE = MEdamp.NRow(); n = 1; - 30:

for (row=1; row < (nE + 1); row = row + 1){ - 31:

damp = MEdamp.Get(row,1); - 32:

if (abs(damp) > 0 .and. abs(damp) < 0.1){ - 33:

Mindx.Set(n,1,row); n = n + 1;}}

- 34:

! Controllability - 35:

nI = Mindx.NRow(); - 36:

for (rowI = 1; rowI < (nI + 1); rowI = rowI + 1){ - 37:

mode = Mindx.Get(rowI,1); - 38:

fopen(IEV,‘r’,0); count = 1; ierr = 1; - 39:

while (ierr > −1){ - 40:

if (count = 1) {ierr = fscanf(0,‘%d’,x); count = 2;} - 41:

if (count = 2) {ierr = fscanf(0,‘%d’,y); count = 3;} - 42:

if (count = 3) {ierr = fscanf(0,‘%d’,real); count = 4;} - 43:

if (count = 4) {ierr = fscanf(0,‘%d’,imag); count = 1;} - 44:

if (y = mode) {Mreal.Set(1,x,real); Mimag.Set(1,x,imag);}} - 45:

fclose(0);

- 46:

nL = Mreal.NCol(); nb = B.NCol(); - 47:

for (col = 1; col < (nb+1); col = col + 1){ - 48:

sumr = 0; sumi = 0; - 49:

for (row = 1; row < (nL + 1); row = row + 1){ - 50:

ar = Mreal.Get(1,row); ai = Mimag.Get(1,row); b = B.Get(row,col); - 51:

sumr = sumr + ar*b; sumi = sumi + ai*b;} - 52:

ctrl_m = sqrt(sumr*sumr+sumi*sumi); ctrl_ang = atan2(sumi/sumr); - 53:

Mctrl_m.Set(rowI,col,ctrl_m); Mctrl_ang.Set(rowI,col,ctrl_ang);}

|

| Algorithm 4 DPL Script for Residue Calculation (Part II) |

- 1:

! Observability - 2:

! .......... Similar to controllability - 3:

! Construction of Residue - 4:

nI = Mobser_m.NRow(); - 5:

nC = Mobser_m.NCol(); - 6:

for (row = 1; row < (nI + 1); row = row + 1){ - 7:

for (col = 1; col < (nc + 1); col = col + 1){ - 8:

ar = Mobser_m.Get(row,col); - 9:

ai = Mctrl_m.Get(row,col); - 10:

res_m = ar*ai; - 11:

MResidue_m.Set(row,col,res_m); - 12:

ar = Mobser_ang.Get(row,col); - 13:

ai = Mctrl_ang.Get(row,col); - 14:

res_ang = ar+ai; - 15:

MResidue_ang.Set(row,col,res_ang);}}

|

5. Discussions

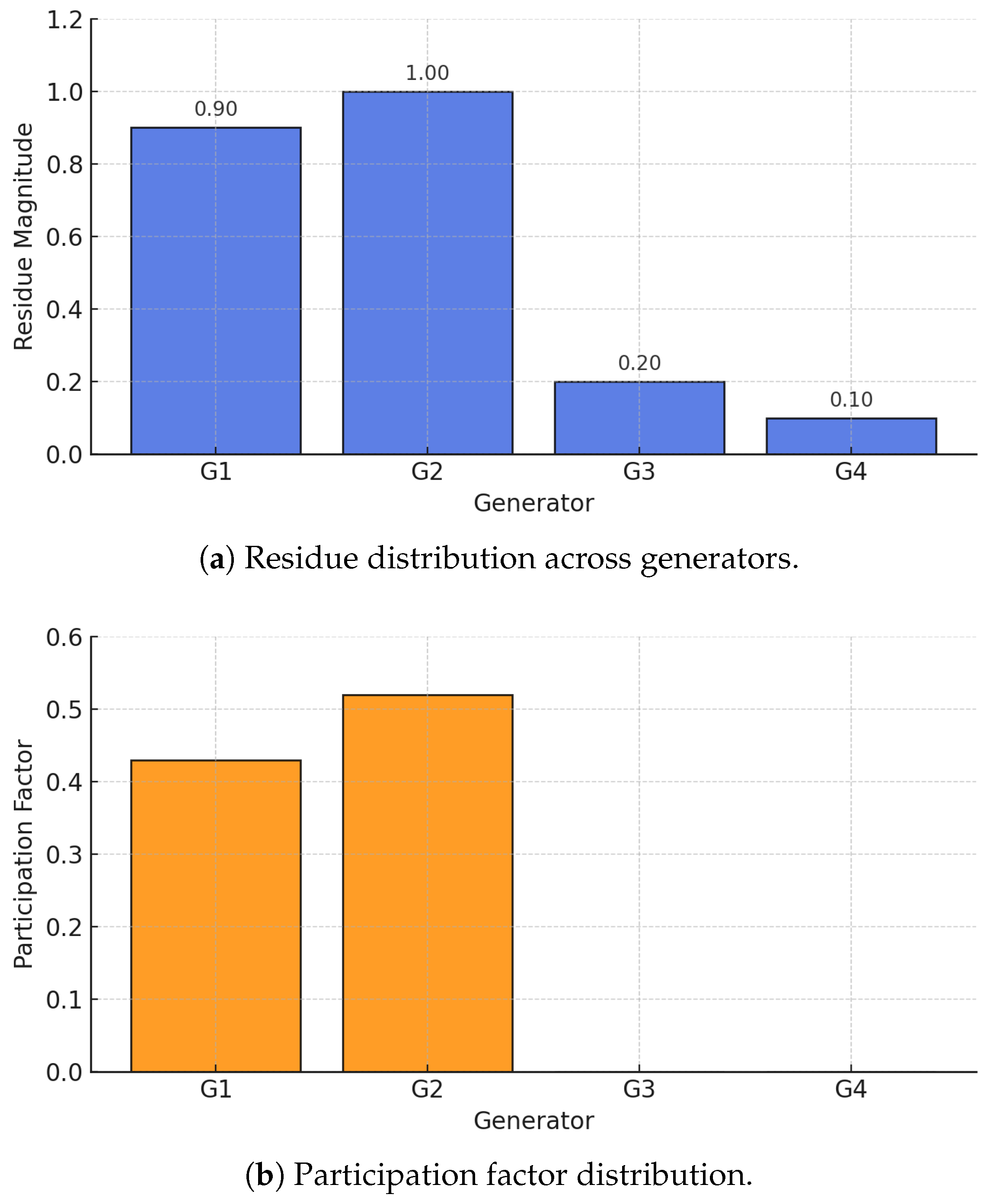

The results obtained in this work highlight the relevance of modal residues as a practical and informative tool for analyzing and mitigating oscillatory modes in power systems. A key observation is that residue-based indices provide a richer interpretation than classical participation factors. While participation factors indicate which state variables are most involved in a given oscillation, residues quantify both controllability and observability, thereby linking eigenvalue dynamics directly to potential control actions. This dual characterization explains why residues consistently identified the most effective generators for damping enhancement, even in cases where participation factors alone offered ambiguous guidance.

The choice of output variables in matrix plays a crucial role in determining which modes are most observable and, consequently, which controllers are most effective. Although generator rotor speed was selected in this study—since it aligns directly with the frequency-power dynamics addressed by PSS tuning—other outputs can be adopted to target different oscillation phenomena. For example, rotor angle or tie-line active power can improve inter-area mode observability, being relevant for HVDC links; terminal voltage magnitude and reactive power emphasize voltage-related dynamics suitable for SVC or STATCOM devices; and electrical torque enhances machine-level observability for excitation or governor control. In all cases, interpreting residues through their controllability and observability components ensures alignment between the selected sensing variable and the intended actuation path.

Another key aspect demonstrated by the results is the scalability of the methodology. In the Two-Area Kundur Test System, residues clearly pointed to and as the optimal PSS locations, in agreement with established results in the literature. When applied to the reduced New York–New England system, the methodology successfully revealed an unstable inter-area mode and identified different generators ( and ) as dominant for its mitigation. This demonstrates that residue-based analysis adapts naturally to systems of varying complexity while maintaining interpretability and providing mode-specific control recommendations.

In very large-scale networks, practical considerations emerge. First, the completeness and consistency of dynamic models, along with access to the full state-space representation, are prerequisites for reliable computation. Second, the computational cost of eigenanalysis increases rapidly with system order, requiring the use of sparse representations, iterative eigensolvers, or selective mode targeting to maintain tractability. Third, constructing the input matrix via perturbation-based sensitivities can be computationally demanding and numerically sensitive when numerous candidate inputs are considered. Finally, large-scale systems often exhibit ill-conditioning and parameter uncertainty; thus, normalization of controllability and observability components, together with selective filtering of dominant inputs and outputs, improves comparability across devices. These considerations have been discussed in the manuscript as pragmatic measures to preserve efficiency and accuracy when extending the method to realistic large-scale systems.

A further consideration arises when residue magnitudes for a particular mode are very similar across several generators, making the identification of a single dominant unit less straightforward. In such cases, decomposing the residues into their normalized controllability and observability components mitigates scaling effects and enables a relative assessment of modal influence. This approach enhances the discriminatory power of the analysis, ensuring that generators contributing proportionally to mode excitation or observation are accurately identified.

The implementation of the proposed framework directly within DIgSILENT PowerFactory offers significant practical advantages. Unlike approaches requiring external data exchange or user-built state-space models, this integration leverages PowerFactory’s native modal analysis and scripting capabilities, enabling automated, repeatable, and traceable workflows. This minimizes user intervention, reduces data handling errors, and makes the analysis more accessible to practitioners. Nevertheless, as with any small-signal method, the approach depends on linearized system models and full access to state-space matrices, which may limit its direct application in cases where such information is incomplete or proprietary.

Finally, although this study focused on PSS tuning, the underlying framework is general and can be extended to other damping controllers. By redefining the input and output channels in matrices and , the same residue-based procedure can guide the placement and tuning of FACTS devices, HVDC controllers, or inverter-based resources. Extending the analysis to these technologies—along with nonlinear and time-domain validation—remains an important avenue for future research, which has been explicitly emphasized in the conclusions.

Overall, the discussion confirms that residue-based analysis not only offers theoretical insight into the controllability and observability of oscillatory modes but also provides actionable guidance for controller allocation and tuning. By integrating this framework into PowerFactory and validating it across multiple benchmark systems, the proposed approach proves to be both robust and scalable, bridging the gap between theoretical modal analysis and practical control design for small-signal stability enhancement.