Simulation Analysis of Cu2O Solar Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

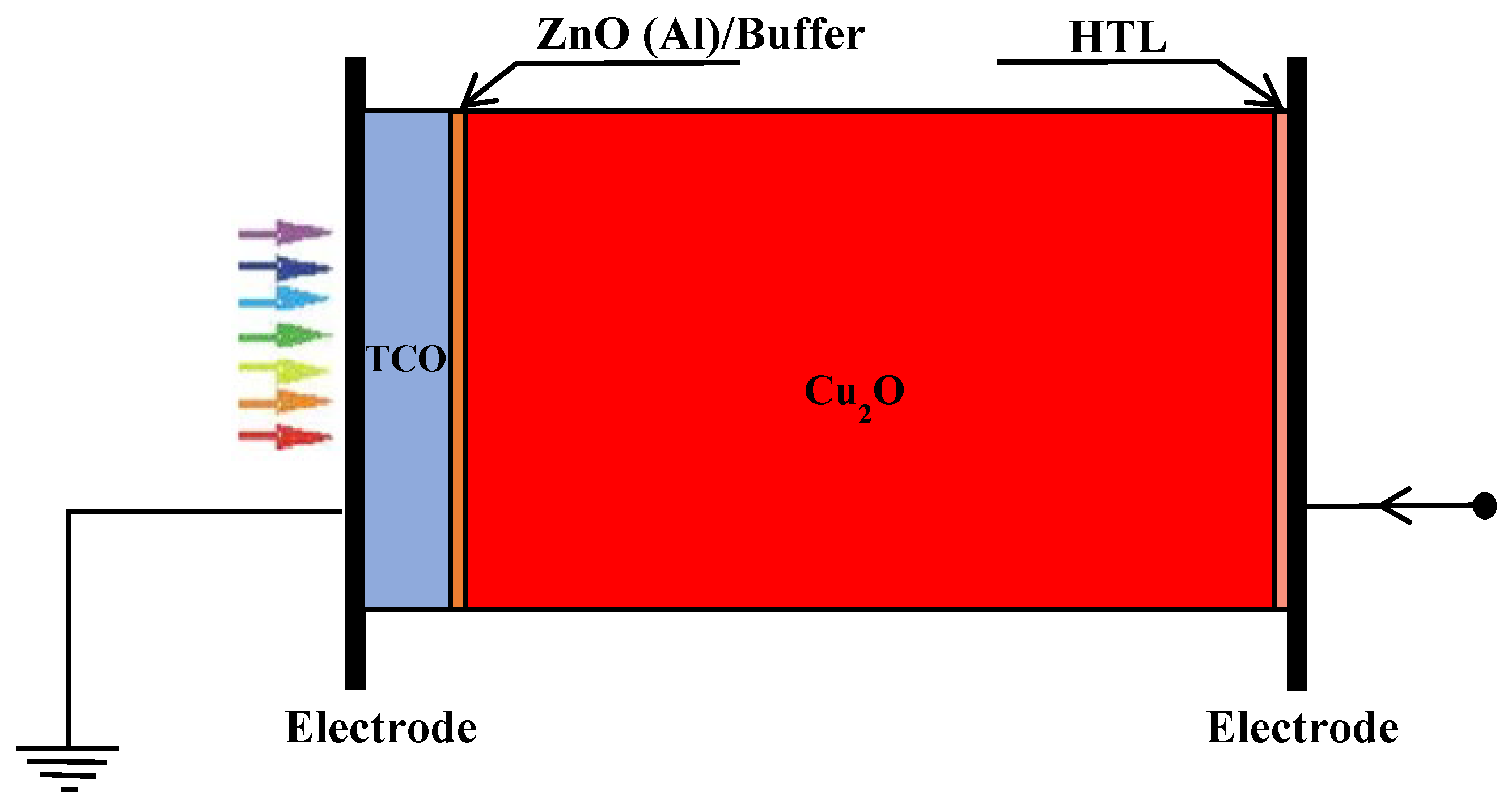

2. Simulation Methods

3. Results and Discussion

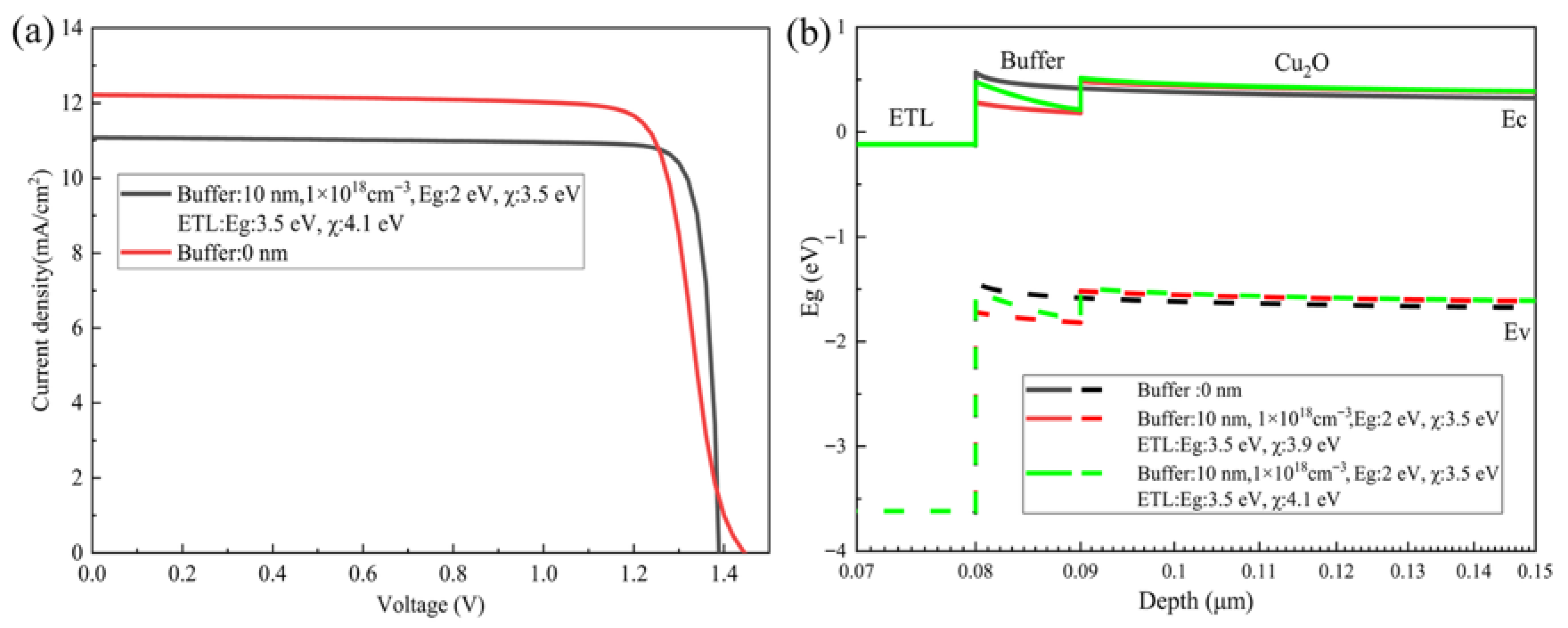

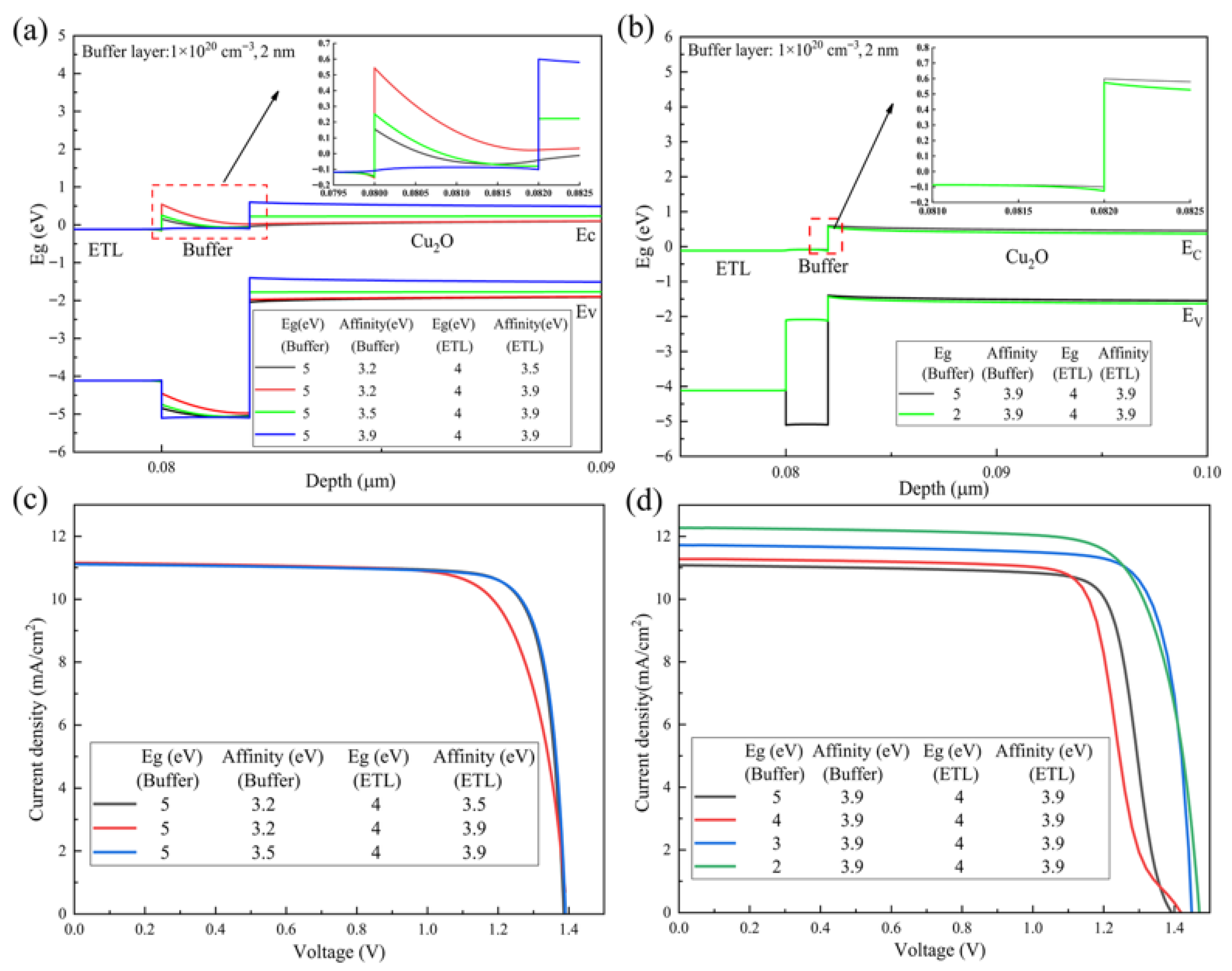

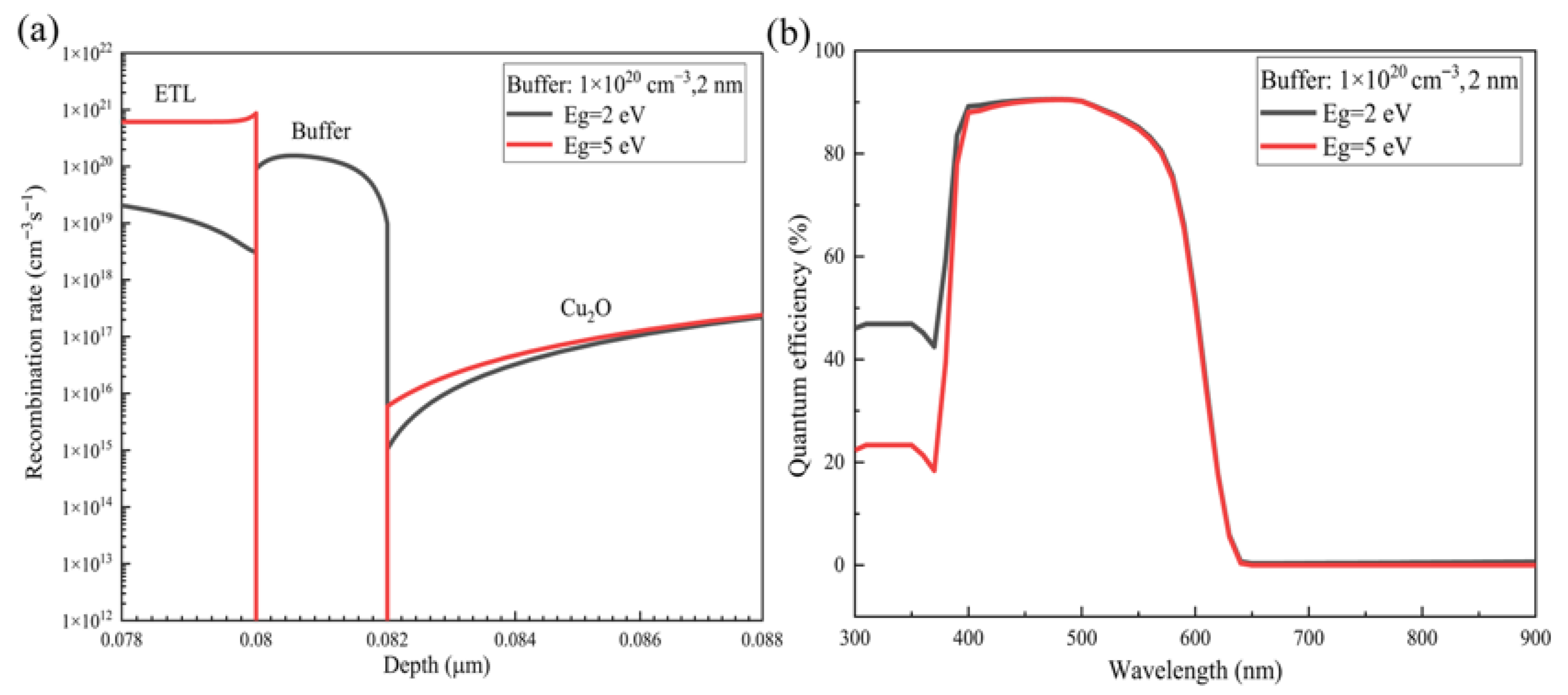

3.1. The Effect of Bandgap and Electron Affinity of the ETL and Buffer Layers

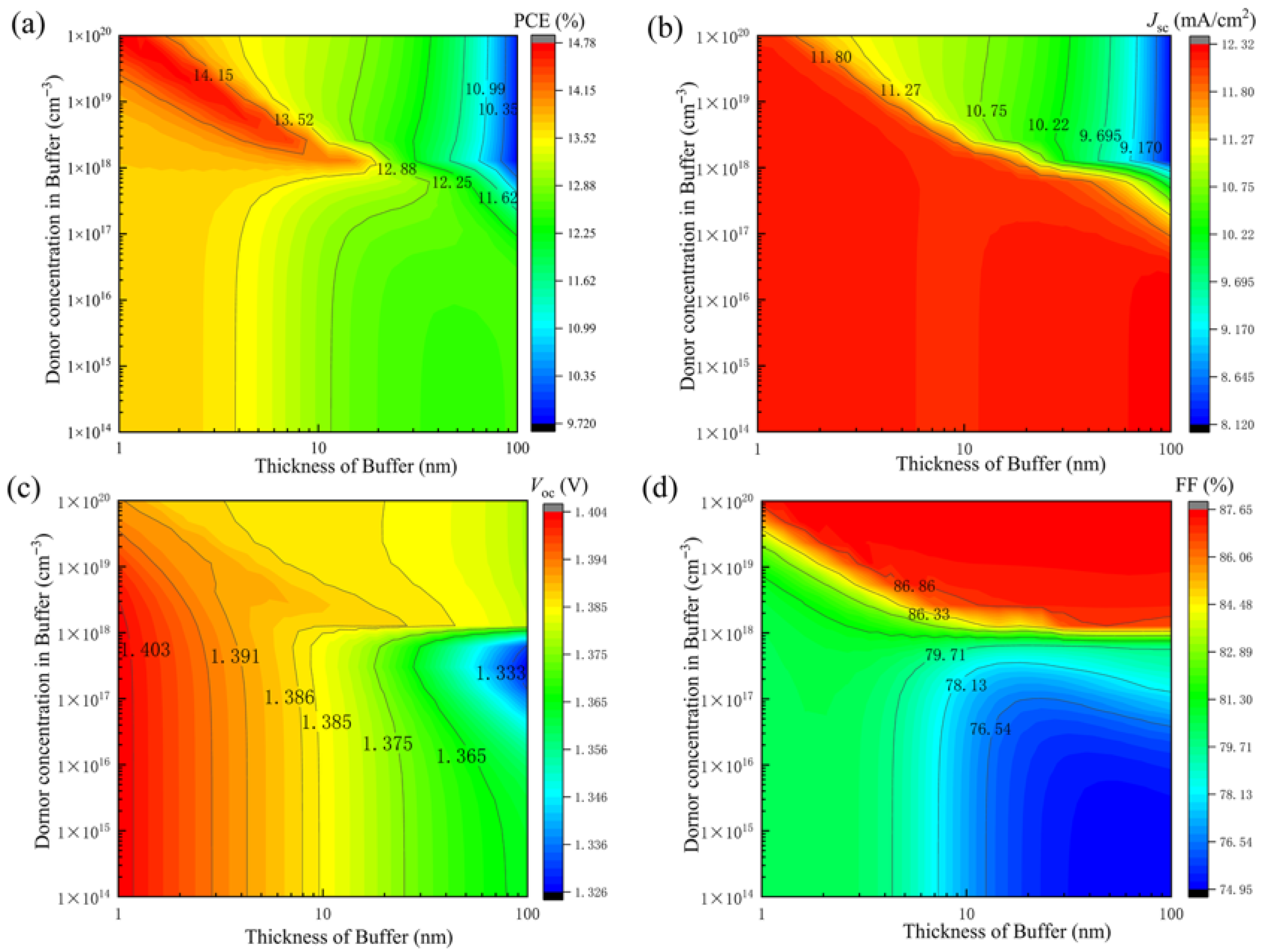

3.2. Influence of Buffer Thickness and Doping Concentration

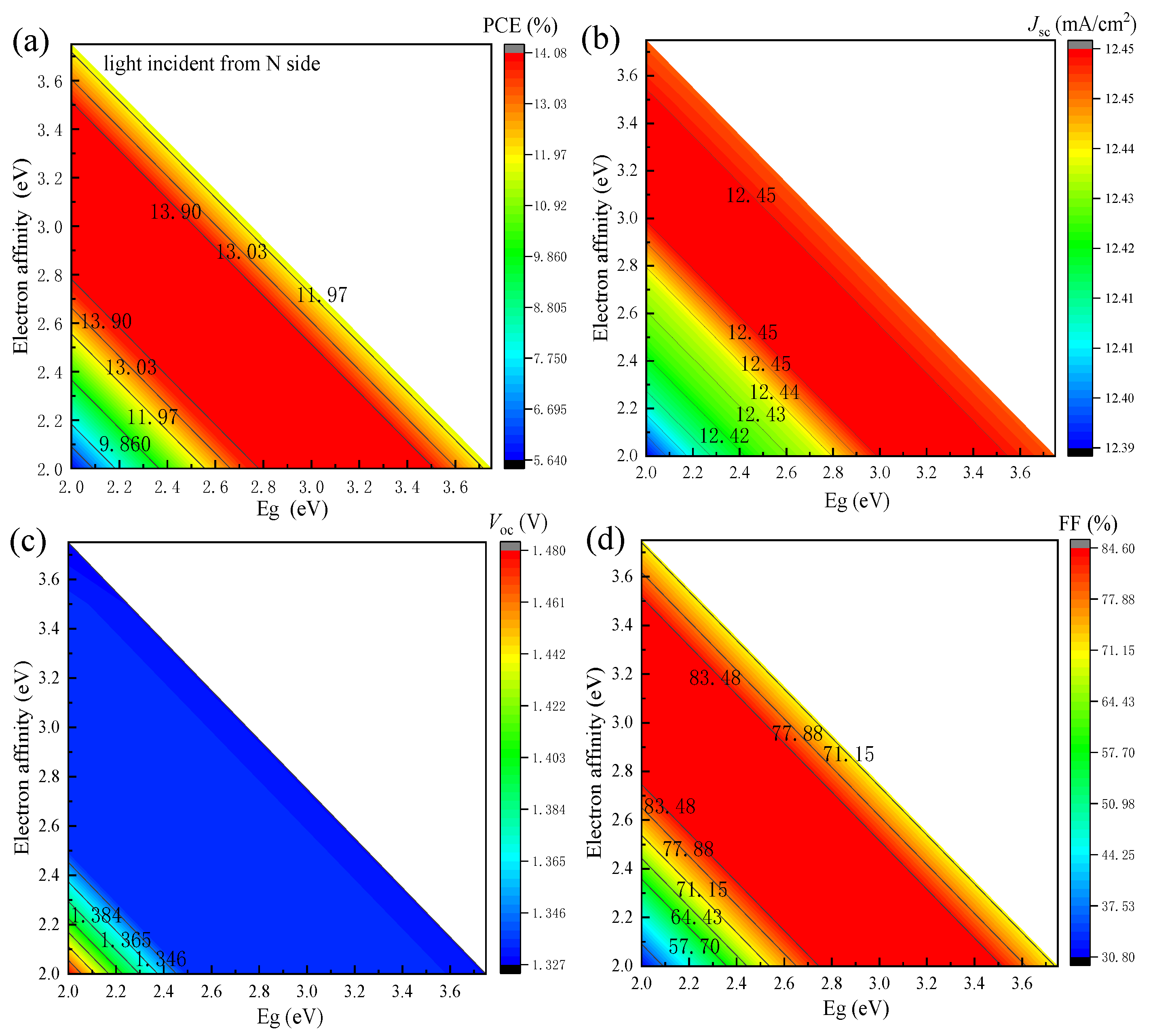

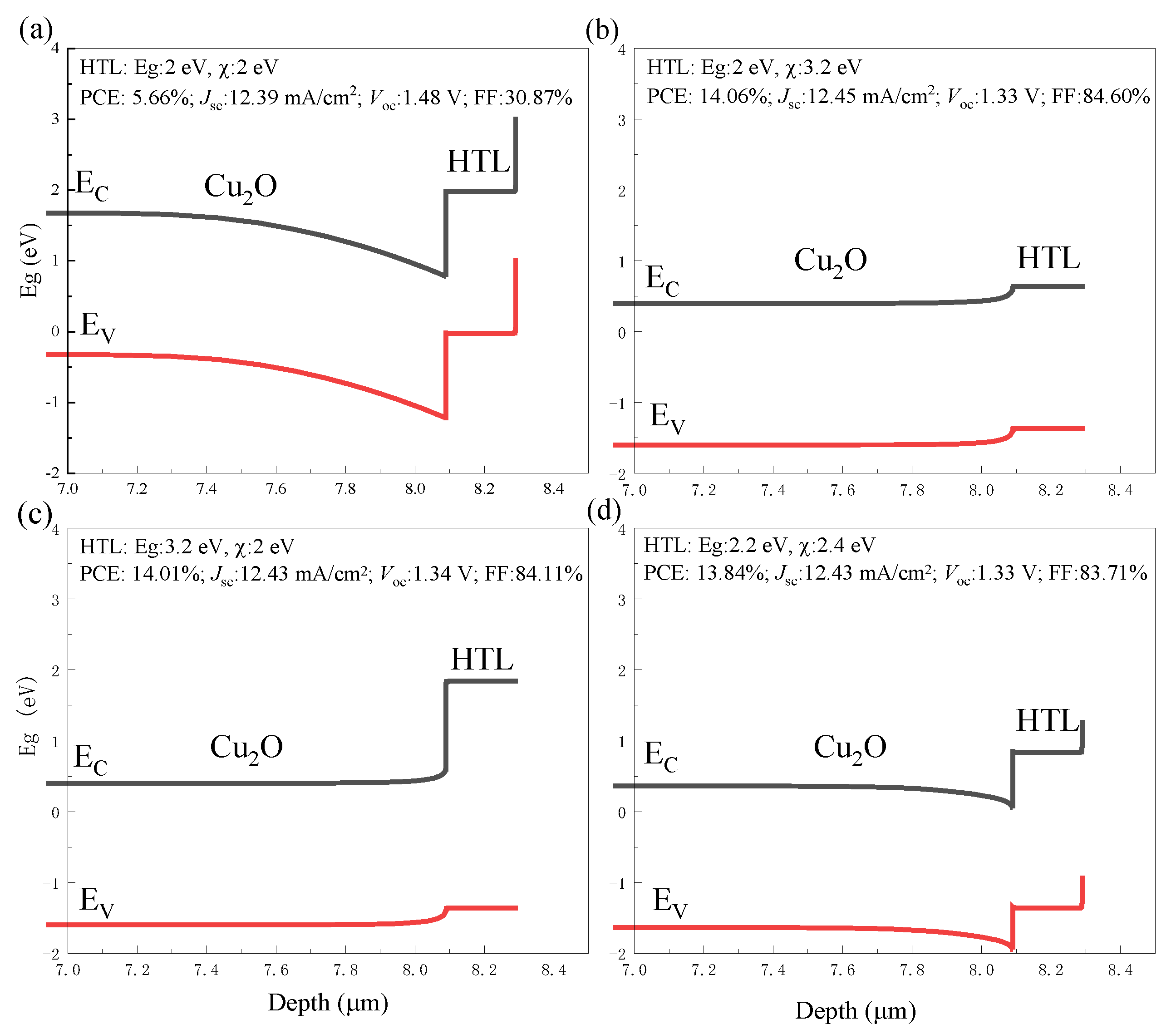

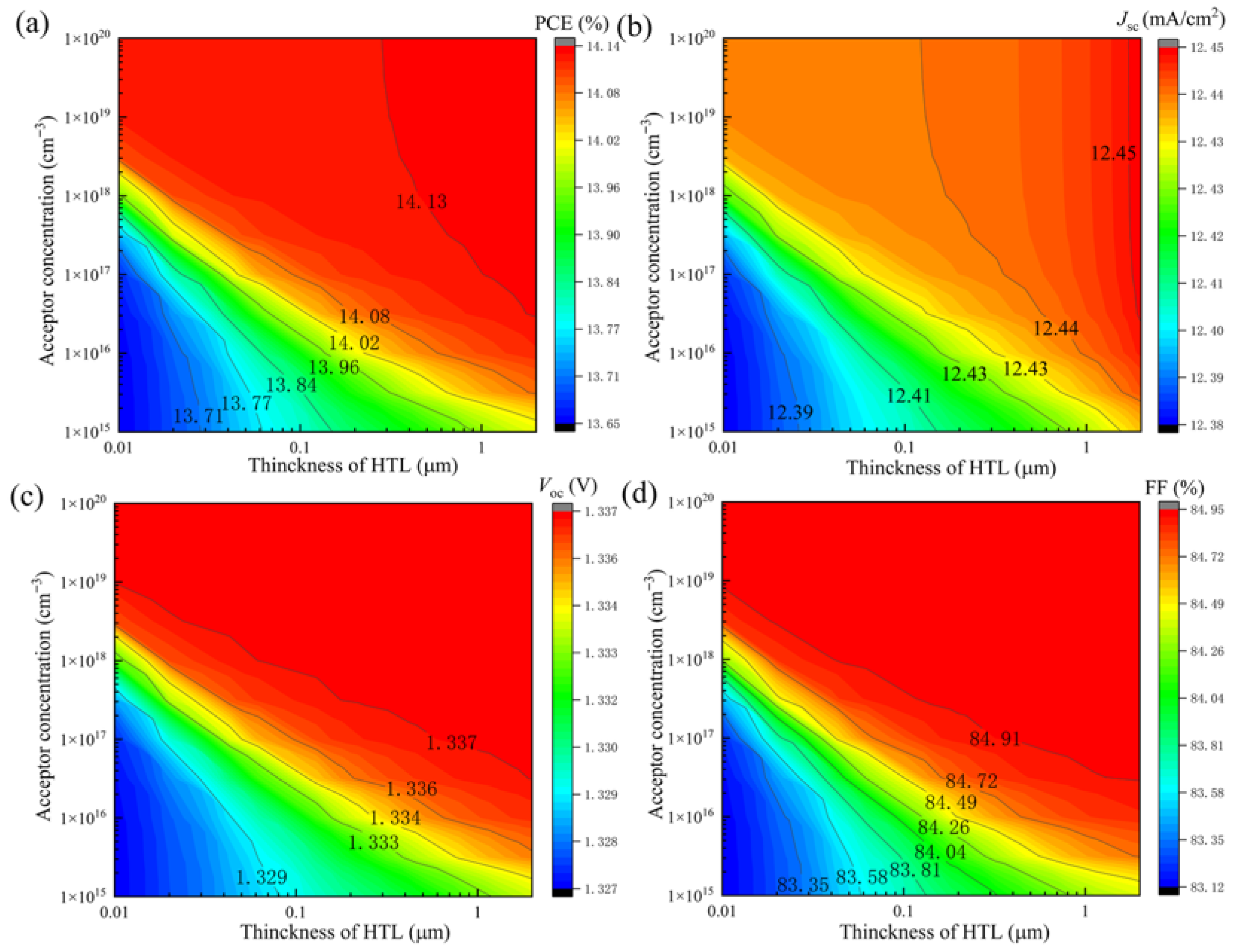

3.3. The Impact of the Bandgap, Electron Affinity, Thickness, and Doping Concentration of the HTL Layer

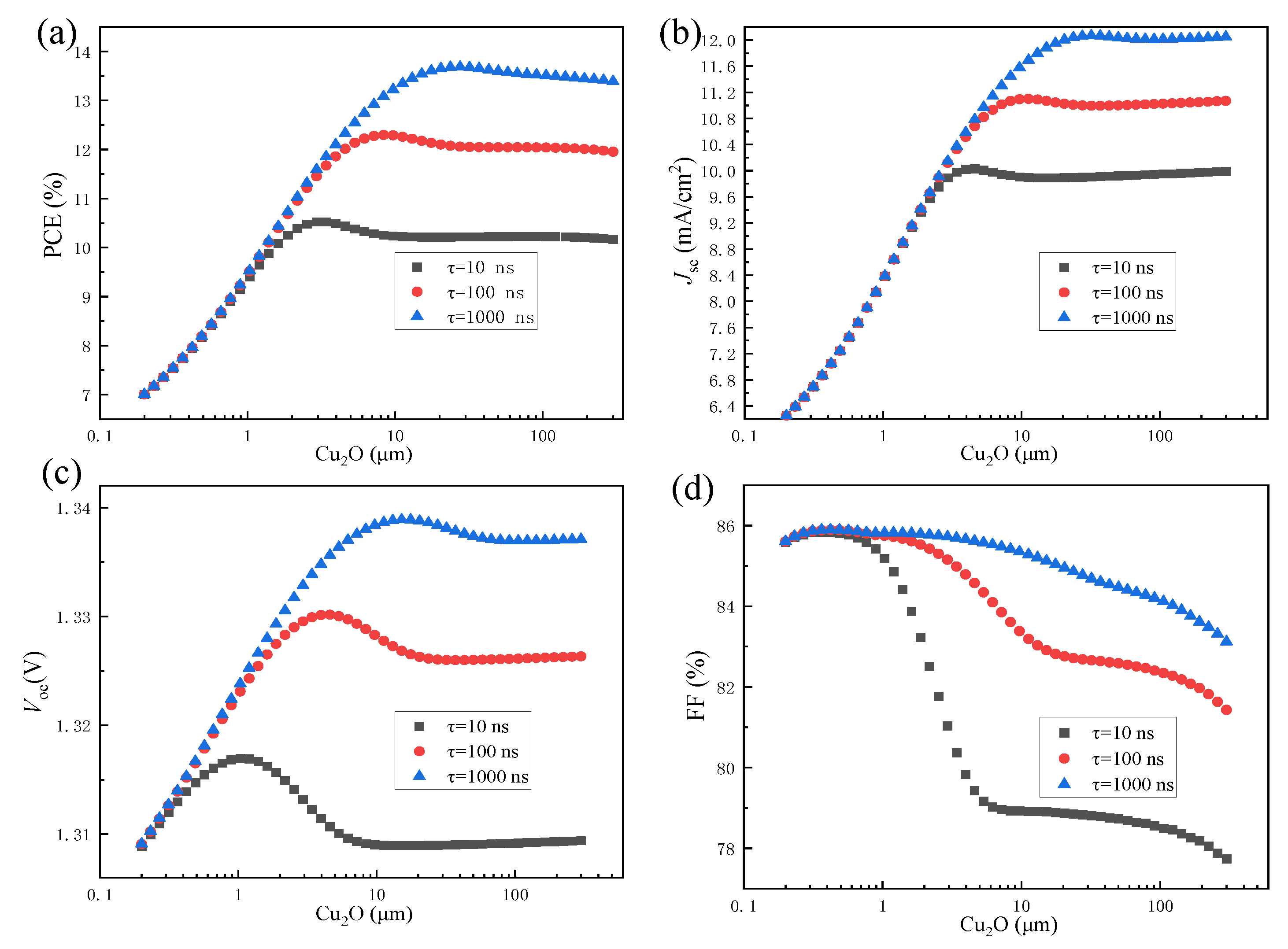

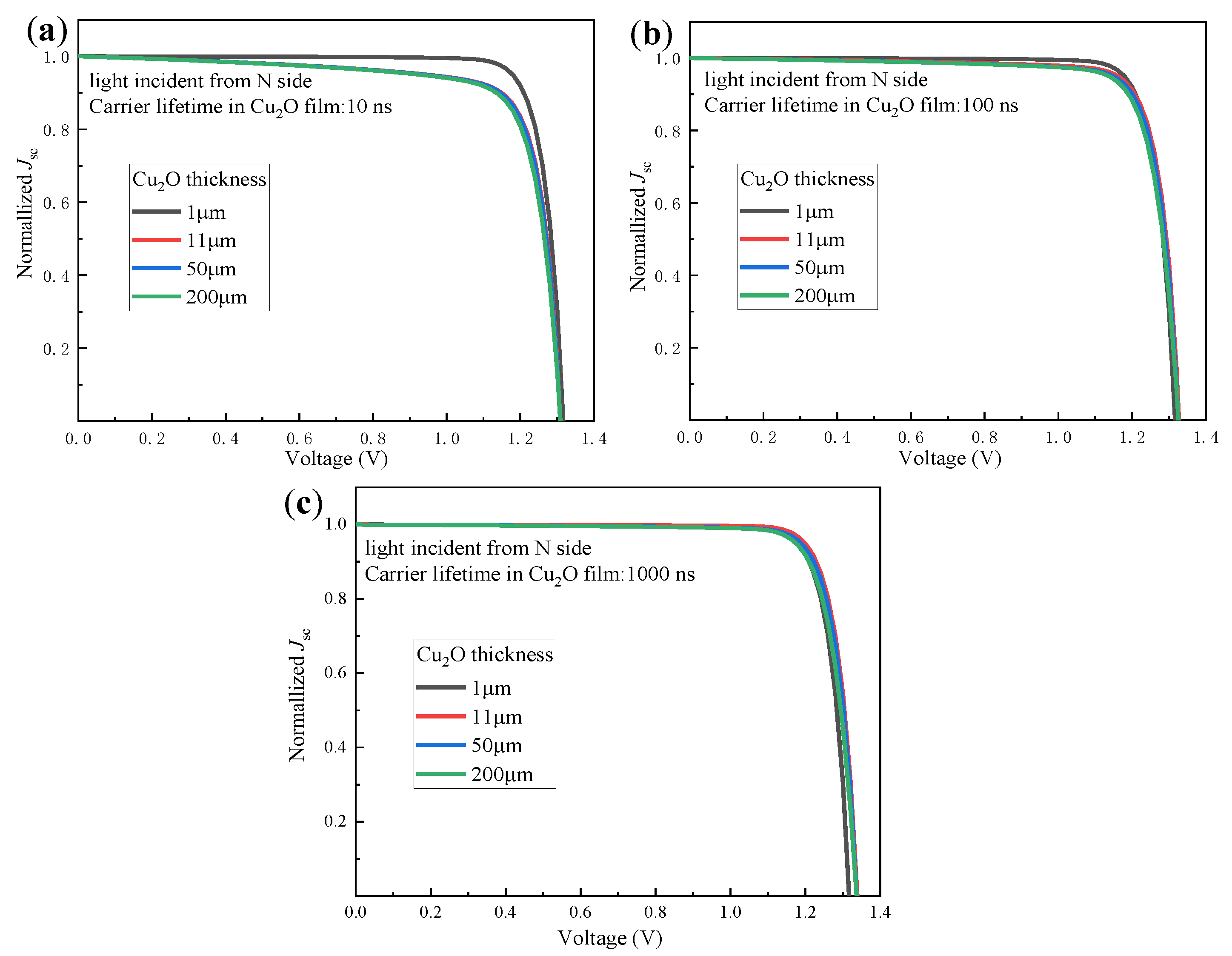

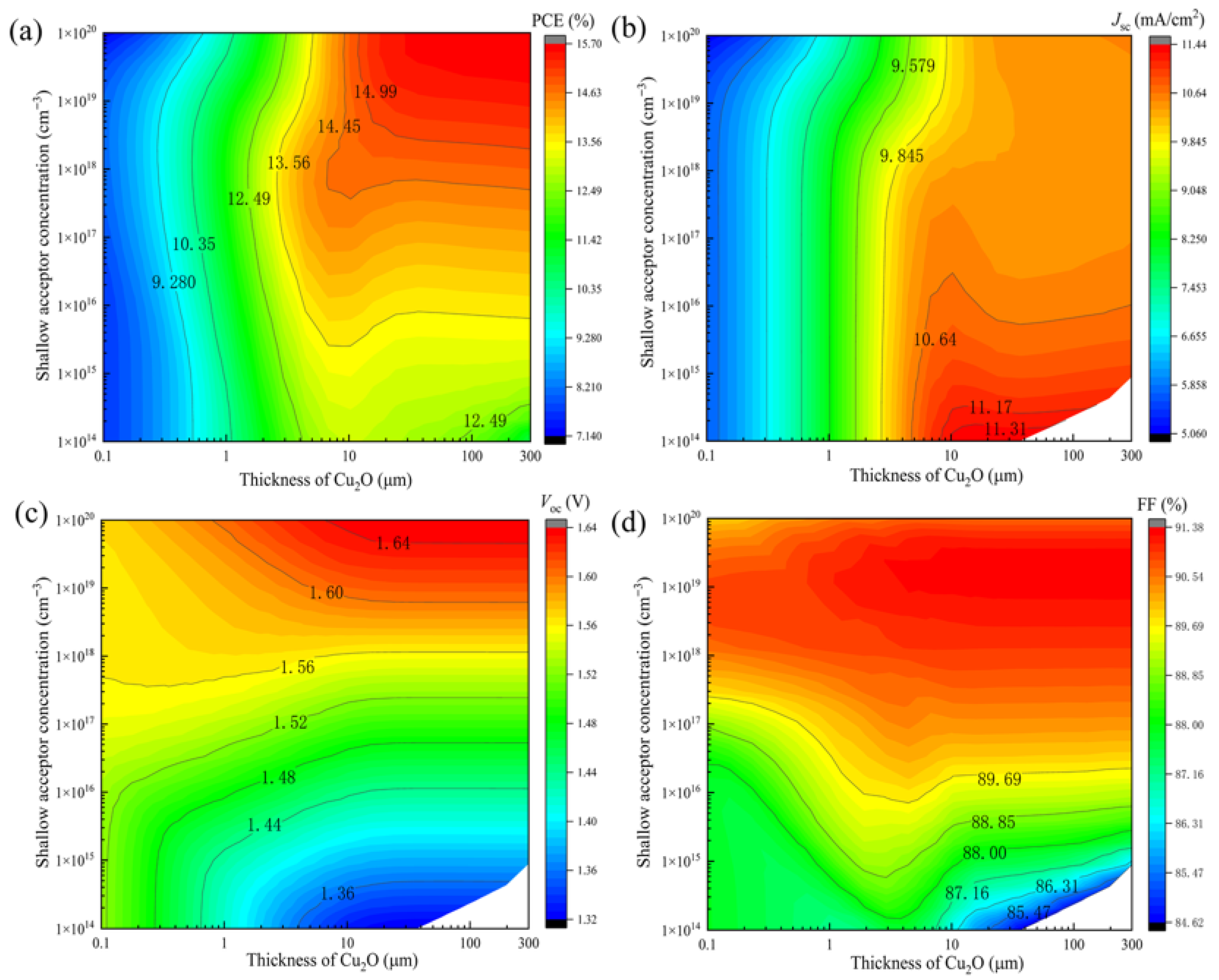

3.4. The Effect of Carrier Lifetime, Thickness, and Doping Concentration of the Cu2O Absorber Layer

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lakshmanan, A.; Alex, Z.C.; Meher, S.R. Recent advances in cuprous oxide thin film based photovoltaics. Mater. Today Sustain. 2022, 20, 100244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhad, S.F.U.; Hossain, A.; Tanvir, N.I.; Akter, R.; Patwary, A.M.; Shahjahan, M.; Rahman, M.A. Structural, optical, electrical, and photoelectrochemical properties of cuprous oxide thin films grown by modified silar method. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2019, 95, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.-K.; Wu, J.-R.; Chen, M.-H.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lin, Y.-G. Fabrication of homojunction Cu2O solar cells by electrochemical deposition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 354, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Gibson, U.J. A simple two-step electrodeposition of Cu2O/ZnO nanopillar solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 6408–6412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitroi, M.R.; Ninulescu, V.; Fara, L. Tandem solar cells based on Cu2O and c-si subcells in parallel configuration: Numerical simulation. Int. J. Photoenergy 2017, 2017, 7284367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, N.; Shibasaki, S.; Honishi, Y.; Yamazaki, M.; Hiraoka, Y.S.; Yamamoto, K. Development of a zn-based n-layer in cuprous oxide top cells for high-efficiency tandem photovoltaics. In Proceedings of the 2020 47th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference (PVSC), Calgary, ON, Canada, 15 June–21 August 2020; pp. 0983–0985. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Wang, L.; Zhou, C.; Yang, J. A review of Cu2O solar cell. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2023, 15, 062701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhu, L.; Li, Y.; Cao, L.; Guo, Y. Asymmetric interface band alignments of Cu2O/ZnO and ZnO/Cu2O heterojunctions. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 578, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Botchkarev, A.; Rockett, A.; Morkoc, H. Valence-band discontinuities of wurtzite gan, aln, and inn heterojunctions measured by x-ray photoemission spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1996, 68, 2541–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.J.; Yu, W.X.; Xu, M.; Cao, J.J.; Chen, C.; Yu, W.W.; Wang, Y.D. Valence band offset of Cu2O/in2o3 heterojunction determined by x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramm, B.; Laufer, A.; Reppin, D.; Kronenberger, A.; Hering, P.; Polity, A.; Meyer, B.K. The band alignment of Cu2O/ZnO and Cu2O/gan heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 100, 094102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.M.; Zhu, L.P.; Jiang, J.; Hu, L.; Ye, C.L.; Ye, Z.Z. Valence band offset of n-ZnO/p-mgxni1-xo heterojunction measured by x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 052109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Cao, C.; Nabi, G.; Khan, W.S.; Usman, Z.; Mahmood, T. Effect of electrodeposition and annealing of ZnO on optical and photovoltaic properties of the p-Cu2O/n-ZnO solar cells. Electrochim. Acta 2011, 56, 8342–8346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Z. Efficiency enhancement of ZnO/Cu2O solar cells with well oriented and micrometer grain sized Cu2O films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2018, 112, 042106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittiga, A.; Salza, E.; Sarto, F.; Tucci, M.; Vasanthi, R. Heterojunction solar cell with 2% efficiency based on a Cu2O substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 163502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koda, D.S.; Bechstedt, F.; Marques, M.; Teles, L.K. Trends on band alignments: Validity of anderson’s rule in sns 2-and snse 2-based van der waals heterostructures. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 165402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiel, H.; Hutter, O.S.; Phillips, L.J.; Swallow, J.E.; Jones, L.A.; Featherstone, T.J.; Smiles, M.J.; Thakur, P.K.; Lee, T.L.; Dhanak, V.R.; et al. Natural band alignments and band offsets of Sb2Se3 solar cells. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 11617–11626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toshiba. Toshiba Boosts Transparent Cu2O Tandem Solar Cell to a New High. Available online: https://www.global.toshiba/ww/technology/corporate/rdc/rd/topics/22/2209-02.html (accessed on 22 October 2025).

- Yoshio, S.; Wada, A.; Shibasaki, S.; Nakagawa, N.; Mizuno, Y.; Honishi, Y.; Wakamatsu, K.; Toyota, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Sano, J.; et al. Thermal stability of cuprous oxide top cells for high-efficiency Cu2O/si tandem solar cells. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 52nd Photovoltaic Specialist Conference (PVSC), Seattle, WA, USA, 9–14 June 2024; pp. 0149–0151. [Google Scholar]

- Shockley, W.; Queisser, H.J. Detailed balance limit of efficiency of p-n junction solar cells. J. Appl. Phys. 1961, 32, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, M.; Nollet, P.; Degrave, S. Modelling polycrystalline semiconductor solar cells. Thin Solid Film. 2000, 361, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemegeers, A.; Burgelman, M. Numerical modelling of ac-characteristics of cdte and cis solar cells. In Proceedings of the Conference Record of the Twenty Fifth IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference-1996, Washington, DC, USA, 13–17 May 1996; pp. 901–904. [Google Scholar]

- Verschraegen, J.; Burgelman, M. Numerical modeling of intra-band tunneling for heterojunction solar cells in scaps. Thin Solid Film. 2007, 515, 6276–6279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degrave, S.; Burgelman, M.; Nollet, P. Modelling of polycrystalline thin film solar cells: New features in scaps version 2.3. In Proceedings of the 3rd World Conference onPhotovoltaic Energy Conversion, Osaka, Japan, 11–18 May 2003; pp. 487–490. [Google Scholar]

- Decock, K.; Khelifi, S.; Burgelman, M. Modelling multivalent defects in thin film solar cells. Thin Solid Film. 2011, 519, 7481–7484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, M.; Marlein, J. Analysis of graded band gap solar cells with scaps. In Proceedings of the 23rd European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference, Valencia, Spain, 1–5 September 2008; pp. 2151–2155. [Google Scholar]

- Sekkat, A.; Bellet, D.; Chichignoud, G.; Kaminskicachopo, A. Unveiling key limitations of ZnO/Cu2O all-oxide solar cells through numerical simulations. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 5423–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka-Chudy, P.; Sibiński, M.; Wisz, G.; Rybak-Wilusz, E.; Cholewa, M. Numerical analysis and optimization of Cu2O/Tio2 CuO/Tio2, heterojunction solar cells using scaps. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1033, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fentahun, D.A.; Tyagi, A.; Kar, K.K. Numerically investigating the AZO/Cu2O heterojunction solar cell using ZnO/Cds buffer layer. Opt.—Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 2020, 228, 166228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, C.; Bose, S.; Hamady, S.O.S.; Fressengeas, N. Numerical investigations of the impact of buffer germanium composition and low cost fabrication of Cu2O on AZO/ZnGeO/Cu2O solar cell performances. Eur. Phys. J. Photovolt. 2021, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizi, M.T.; Abadi, M.S.; Ghaneii, M. Two dimensional modeling of Cu2O heterojunction solar cells based-on β-ga2o3 buffer. Optik 2018, 155, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, N.D. Modelling and numerical analysis of ZnO/CuO/Cu2O heterojunction solar cell using scaps. Eng. Res. Express 2020, 2, 025033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koné, K.E.; Bouich, A.; Soro, D.; Soucase, B.M. Insight of ZnO/CuO and ZnO/Cu2O solar cells efficiency with scaps simulator. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2023, 55, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, T.; Nishi, Y.; Miyata, T. High-efficiency Cu2O-based heterojunction solar cells fabricated using a Ga2O3 thin film as n-type layer. Appl. Phys. Express 2013, 6, 044101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, P.; Chakrabarti, P. Effect of Mg doping in ZnO buffer layer on ZnO thin film devices for electronic applications. Superlattices Microstruct. 2016, 93, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Miyata, T.; Minami, T. The impact of heterojunction formation temperature on obtainable conversion efficiency in n-ZnO/p-Cu2O solar cells. Thin Solid Film. 2013, 528, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.K.; Hanada, T.; Makino, H.; Chen, Y.; Ko, H.J.; Yao, T.; Tanaka, A.; Sasaki, H.; Sato, S. Band alignment at a ZnO/GaN (0001) heterointerface. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2001, 78, 3349–3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K.; Yamaoka, Y.; Ubukata, A.; Arimura, T.; Piao, G.; Yano, Y.; Tokunaga, H.; Tabuchi, T. Opportunities and challenges in gan metal organic chemical vapor deposition for electron devices. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2016, 55, 05FK04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zhao, B.; Yang, T.; Lai, R.; Lan, D.; Friend, R.H.; Di, D. Toward stable and efficient perovskite light-emitting diodes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2109495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shibasaki, S.; Honishi, Y.; Nakagawa, N.; Yamazaki, M.; Mizuno, Y.; Nishida, Y.; Sugimoto, K.; Yamamoto, K. Highly transparent Cu2O absorbing layer for thin film solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 119, 242102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawki, N.; Rouchdi, M.; Alla, M.; Fares, B. Simulation and analysis of high-performance hole transport material srzrs3-based perovskite solar cells with a theoretical efficiency approaching 26%. Sol. Energy 2023, 262, 111913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, D.; Patel, S.; Chander, S.; Kannan, M.; Dhaka, M. Enhanced physicochemical properties of znte thin films as potential buffer layer in solar cell applications. Solid State Sci. 2020, 107, 106346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Guo, Y.; Xie, H.; Que, W.; Kong, L.B. Nickel Oxide as Efficient Hole Transport Materials for Perovskite Solar Cells. Sol. Rrl 2019, 3, 1900001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minami, T.; Nishi, Y.; Miyata, T. Efficiency enhancement using a zn1− xgex-o thin film as an n-type window layer in Cu2O-based heterojunction solar cells. Appl. Phys. Express 2016, 9, 052301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ţălu, Ş.; Yadav, R.P.; Šik, O.; Sobola, D.; Dallaev, R.; Solaymani, S.; Man, O. How topographical surface parameters are correlated with cdte monocrystal surface oxidation. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2018, 85, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, F.; Veith-Wolf, B.; Spindler, C.; Barget, M.R.; Babbe, F.; Guillot, J.; Schmidt, J.; Siebentritt, S. Oxidation as key mechanism for efficient interface passivation in cu (in, Ga) Se2 thin-film solar cells. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2020, 13, 054004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | ETL | Buffer [28,34] | Cu2O | HTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness (μm) | 0.08 | Varied | Varied | Varied |

| Band gap (eV) | Varied | Varied | 213 | Varied |

| electron affinity (eV) | Varied | Varied | 3.233 | Varied |

| Donor concentration (cm−3) | 1.000 × 1020 | Varied | 0 | 0 |

| Acceptor concentration (cm−3) | 0 | 0 | Varied | Varied |

| Dielectric permittivity (relative) | 8.910 | 6.180 | 7.600 | 7.600 |

| CB effective density of states (cm−3) | 8.090 × 1018 | 3.718 × 1018 | 1.050 × 1019 | 1.050 × 1019 |

| VB effective density of states (cm−3) | 9.420 × 1019 | 1.137 × 1019 | 2.250 × 1019 | 2.250 × 1019 |

| Electron thermal velocity (cm/s) | 1.000 × 107 | 1.000 × 107 | 1.000 × 107 | 1.000 × 107 |

| Hole thermal velocity (cm/s) | 1.000 × 107 | 1.000 × 107 | 1.000 × 107 | 1.000 × 107 |

| Electron mobility (cm2/Vs) | 30 | 50 | 200 | 200 |

| Hole mobility (cm2/Vs) | 3 | 5 | 100 | 100 |

| Total defect density (cm−3) | 1.0 × 1018 | 1.0 × 1018 | 1.0 × 1013 | 1.0 × 1013 |

| Energy level (eV) | 0.60 | 1.20 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| Electron lifetime (ns) | 1.0 × 101 | 1.0 × 101 | 1.4 × 102 | 1.4 × 102 |

| Hole lifetime (ns) | 1.0 × 101 | 1.0 × 10−4 | 1.4 × 102 | 1.4 × 102 |

| Electron diffusion length (μm) | 2.8 × 10−1 | 5.1 × 10−1 | 8.6 × 101 | 2.7 × 101 |

| Hole diffusion length (μm) | 8.8 × 10−2 | 1.1 × 10−3 | 6.1 × 101 | 1.9 × 101 |

| Parameter | ETL | Buffer [35,36] | Cu2O | HTL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness (μm) | 0.08 | Varied | Varied | Varied |

| Band gap (eV) | Varied | Varied | 213 | Varied |

| electron affinity (eV) | Varied | Varied | 3.233 | Varied |

| Donor concentration (cm−3) | 1.000 × 1020 | Varied | 0 | 0 |

| Acceptor concentration (cm−3) | 0 | 0 | Varied | Varied |

| Dielectric permittivity (relative) | 8.910 | 6.180 | 7.600 | 7.600 |

| CB effective density of states (cm−3) | 8.090 × 1018 | 3.718 × 1018 | 1.050 × 1019 | 1.050 × 1019 |

| VB effective density of states (cm−3) | 9.420 × 1019 | 1.137 × 1019 | 2.250 × 1019 | 2.250 × 1019 |

| Electron thermal velocity (cm/s) | 1.000 × 107 | 1.000 × 107 | 1.000 × 107 | 1.000 × 107 |

| Hole thermal velocity (cm/s) | 1.000 × 107 | 1.000 × 107 | 1.000 × 107 | 1.000 × 107 |

| Electron mobility (cm2/Vs) | 30 | 50 | 200 | 200 |

| Hole mobility (cm2/Vs) | 3 | 5 | 100 | 100 |

| Bulk density (cm−3) | 1.0 × 1018 | 1.0 × 1018 | 1.0× 1013 | 1.0 × 1013 |

| Energy level (eV) | 0.60 | 1.20 | 0.60 | 0.60 |

| Electron lifetime (ns) | 1.0 × 101 | 1.0 × 101 | 1.4 × 102 | 1.4 × 102 |

| Hole lifetime (ns) | 1.0 × 101 | 1.0 × 10−4 | 1.4 × 102 | 1.4 × 102 |

| Electron diffusion length (μm) | 2.8 × 10−1 | 5.1 × 10−1 | 8.6 × 101 | 2.7 × 101 |

| Hole diffusion length (μm) | 8.8 × 10−2 | 1.1 × 10−3 | 6.1 × 101 | 1.9 × 101 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, S.; Wang, L.; Zhou, C.; Yang, J.; Jia, X. Simulation Analysis of Cu2O Solar Cells. Energies 2025, 18, 5623. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215623

Chen S, Wang L, Zhou C, Yang J, Jia X. Simulation Analysis of Cu2O Solar Cells. Energies. 2025; 18(21):5623. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215623

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Sinuo, Lichun Wang, Chunlan Zhou, Jinli Yang, and Xiaojie Jia. 2025. "Simulation Analysis of Cu2O Solar Cells" Energies 18, no. 21: 5623. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215623

APA StyleChen, S., Wang, L., Zhou, C., Yang, J., & Jia, X. (2025). Simulation Analysis of Cu2O Solar Cells. Energies, 18(21), 5623. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215623