1. Introduction

In recent years, wind energy has emerged as a key solution for achieving carbon neutrality, especially following the 2015 Paris Agreement [

1]. By 2023, global wind capacity exceeded 1047 GW, with offshore wind driving most new growth [

2]. Due to spatial limitations and resource saturation on land, the focus has shifted from shallow nearshore areas to deep-sea regions [

3,

4,

5]. Fixed-bottom wind turbines (FBWTs) are effective in shallow waters but face economic and technical challenges beyond 50–60 m depth [

6]. To overcome it, floating offshore wind turbines have been developed. Supported by mooring systems and various platform types (i.e., spar, semi-submersible and TLP), floating offshore wind turbines enable deep-water deployment and offer benefits such as modularity, rapid installation and reduced environmental impact [

7,

8,

9].

The commercial viability of floating offshore wind turbines was first demonstrated by the Hywind Pilot Plant in the UK (2017), featuring 30 MW capacity [

10]. In 2023, the world’s largest floating wind farm, Hywind Tampen (Norway), became operational, comprising eleven 8.6 MW turbines at 260–300 m water depths [

11]. As floating farms scale up, wake interactions among turbines impacting performance, loads and energy output have become critical. Prior studies emphasize the need to account for wake effects in wind farm design beyond individual turbine analysis [

8,

12].

Recent studies have increasingly focused on the coupling mechanisms between floating offshore wind turbine platform motion and the wake flow field. However, the majority of these works has concentrated on surge motion, while investigations of pitch motion have largely been confined to simplified, periodic excitations under steady inflow conditions [

8,

13]. Among the 6-DOFs (Six Degrees Of Freedom), pitch motion (longitudinal rotation about the platform’s lateral axis) plays a particularly critical role in influencing rotor aerodynamics and wake topology. From a fluid-dynamics standpoint, pitch motion cyclically alters the rotor disk’s inclination relative to the incoming flow, thereby modulating the blade’s effective angle of attack. This variation directly affects blade lift and drag forces, inducing periodic fluctuations in rotor thrust and conversion efficiency [

14,

15]. Fu et al. [

16] analyzed the effects of pitch amplitude and frequency on both aerodynamic loads and wake behavior. More recently, Kadum et al. [

17] employed large-eddy simulation (LES) to show that high-amplitude pitch motion enhances the non-uniformity of vorticity in the wake core and promotes early shear-layer breakdown. These periodic disturbances were found to amplify unsteady loading and fatigue stress on downstream turbines. However, when the pitch frequency approaches structural modes such as the blade-passing frequency (1P, 3P), wake disturbances can resonate with downstream turbines, exacerbating unsteady loads and fatigue accumulation. Wen et al. [

18] further identified strong frequency dependence in pitch-induced wake effects. Low-frequency pitch was shown to alter the global wake morphology, while high-frequency oscillations promoted small-scale vortex disintegration, influencing enstrophy transfer and dissipation dynamics. Despite these insights, the current literature still lacks a comprehensive understanding of how pitch motion governs the temporal wake modulation, aerodynamic loading of downstream turbines, and the overall aerodynamic coherence across floating offshore wind turbines arrays.

Floating wind turbine platforms such as spar, semi-submersible, and tension-leg platforms (TLPs) exhibit markedly different motion characteristics due to inherent differences in hydrostatic stability, natural frequencies and damping properties. These variations give rise to significant disparities in motion amplitudes, dominant modal frequencies, and coupling behavior across the 6-DOFs. Consequently, the spectral content of wake disturbances, the structure of energy dissipation pathways, and the downstream wake propagation patterns can differ substantially among platform types. While these motion-induced differences affect the wake morphology behind a single turbine, they become more pronounced in multi-turbines arrays, where wake–wake interactions can amplify the platform-specific flow signatures. This has direct implications for the overall stability, coherence, and energy yield of floating wind farms. Previous studies, for instance, Duan et al. [

19] have examined semi-submersible platforms and shown that periodic surge motion introduces coherent wake structures that propagate downstream, leading to cyclic variations in the power output of trailing turbines. Despite these findings, research into how different platform types respond to 6-DOFs excitation and how these responses influence wake dynamics across an array remains limited. Most existing work assumes homogeneous platform configurations and does not account for cross-platform variability in wake evolution. However, from an engineering perspective, a shift transitioning into hybrid arrays is already underway. As the commercial deployment of floating offshore wind turbines accelerates, heterogeneous turbine layouts combining spar, semi-submersible, and TLP systems are likely to become the norm. Understanding how the performance of such mixed-platform farms evolves under realistic ocean conditions is crucial for guiding array layout design and developing robust coordinated control strategies. Recent advances in wind farm control, including yaw-based wake steering, flow-aware turbine dispatch, and predictive control algorithms, have demonstrated improvements in energy capture and wake mitigation [

20,

21,

22]. However, these methods are typically developed under the assumption of identical turbine behavior and overlook the consequences of platform-induced motion diversity. As a result, there is a lack of physical modeling frameworks that couple platform-specific unsteady motions with aerodynamic interactions at the farm scale. Addressing this gap is essential to support next-generation control strategies that can fully account for the complex, dynamic wake behavior in mixed-platform floating wind farms.

Motivated by the observed influence of platform pitch motion on wake periodicity and its downstream effects on turbine power generation and aerodynamic loading, this study aims to systematically evaluate the interplay between wake dynamics, aerodynamic response, and energy yield across four representative FOWT platform types. By accounting for both power production efficiency and fatigue-inducing flow fluctuations, we examine how platform-specific motion responses shape the near and far wake behavior, inflow velocity profiles, and downstream rotor performance within array configurations. This investigation provides a detailed characterization of free-motion responses in floating wind farms and elucidates their physical origins.

In

Section 2, high-fidelity computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations are employed to analyze the wake dynamics of a floating wind turbine subjected to prescribed pitch motion. The results reveal how platform-induced kinematics modulate wake unsteadiness and vortex evolution at the single-turbine scale. In

Section 3, it performs a comparative study across four typical platform configurations, including spar, semi-submersible, TLP, and monopile (Mnpl) to quantify differences in 6-DOFs motion signatures and resulting wake behavior. Specific focus is placed on rotor displacement, wake centerline trajectories, velocity deficit characteristics, and downstream aerodynamic loading. Together, these analyses offer mechanistic insights into motion -wake coupling and inform the development of optimized array layouts and coordinated control strategies for floating offshore wind farm.

2. Methodology

This study employs Large-Eddy Simulation (LES) to investigate the unsteady aerodynamic and wake dynamics of a tandem-arranged floating offshore wind farm. In LES, the large-scale turbulent structures are directly resolved across the computational domain, while the smaller subgrid-scale (SGS) eddies are modeled using dedicated closure approaches. Unlike Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) methods, which rely on statistical averaging of the governing equations, LES adopts spatial filtering techniques that preserve transient and three-dimensional features of turbulent flow—making it more suitable for capturing dynamic wake evolution and flow–structure interactions in wind energy applications [

23,

24,

25]. A comparative analysis was conducted between the classical Smagorinsky model and more advanced subgrid-scale (SGS) formulations, such as the Dynamic Smagorinsky model, dynamic Lagrangian (DL) and WALE (Wall-Adapting Local Eddy-viscosity) model [

26]. While these alternatives offer enhanced adaptability and improved accuracy in wall-bounded flows or highly anisotropic turbulence, they generally demand significantly greater computational resources and exhibit increased sensitivity to local mesh resolution. Given the scope and resolution of the current floating wind farm simulations, the Smagorinsky model was selected as a pragmatic trade-off between physical realism and computational cost. The associated limitations, such as potential over-diffusivity in wake shear layers, are duly acknowledged, and future investigations will explore the integration of dynamic SGS models to more accurately resolve localized wake behavior and rotor–wake interaction dynamics.

For any instantaneous flow variable

, LES decomposes the solution into a resolved (filtered) component

and a sub-filter (or subgrid-scale) component

, as follows:

Here, denotes a general flow variable, such as a velocity component, pressure, energy, or scalar concentration.

Spatial filtering removes small-scale eddies associated with high-frequency fluctuations, thereby reducing the range of turbulent scales that must be directly resolved. This allows LES to capture the energy-containing structures of turbulence while modeling subgrid-scale effects. The filtering operation in LES can be either explicit or implicit. In explicit LES, a specified filter kernel (e.g., a box or Gaussian function) is applied directly to the discretized Navier–Stokes equations. The filtered variable

is defined by the spatial convolution:

Here, is the filter function, characterized by the filter width , which represents the local grid scale.

Filtering in LES can be implemented in two ways: explicitly, by applying a predefined filter kernel, or implicitly, where the computational grid itself determines the smallest resolvable scales. In implicit filtering, the grid resolution effectively acts as the filter, eliminating the need for an additional filtering operation. This approach is widely adopted in practical CFD solvers due to its simplicity and lower computational cost compared to explicit filtering.

By substituting the decomposed flow variables into the Navier–Stokes equations, one obtains the filtered governing equations, which describe the evolution of the resolved flow field. The filtered continuity, momentum, and energy equations take the following form:

Here, is the fluid density, is the filtered velocity vector, is the filtered pressure, is the identity tensor, is the filtered viscous stress tensor, and represents the body force per unit volume (e.g., gravitational and centrifugal forces). denotes the filtered total energy per unit mass, and is the filtered heat flux vector.

The filtered equations can be rearranged to resemble the form of the unsteady Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations. However, in LES, the turbulent stress terms now represent subgrid-scale (SGS) stresses, which arise from interactions between the resolved large-scale eddies and the unresolved smaller-scale motions. These subgrid-scale stresses are commonly modeled using the Boussinesq approximation, which assumes an eddy-viscosity relationship of the form:

Here, denotes the strain-rate tensor, defined as: , where is the mean velocity field. The strain-rate tensor characterizes local flow deformation and is used in turbulence modeling to link eddy viscosity to velocity gradients.

Unlike fixed-bottom wind turbines, floating offshore wind turbines operate under complex conditions and inevitably experience 6-DOFs motion. Among these, pitch motion is particularly critical, as it directly alters the effective inflow velocity relative to the rotor plane, especially under non-pitch-regulated conditions. Changes in inflow direction and magnitude strongly affect blade aerodynamic loading (lift and drag) and thereby influence rotor thrust and wake development. In this study, it focus on modeling the effects of forced pitch motion imposed on the upstream turbine. The motion is idealized as a deterministic, sinusoidal oscillation, which allows for isolating its physical impact on rotor dynamics, wake evolution, and array-level aerodynamic coupling. Stochastic disturbances introduced by ocean waves or turbulent wind–wave interactions are not considered, in order to better isolate the role of platform-induced motion.

The prescribed pitch motion is implemented as a sinusoidal forcing function of the form [

25,

27]:

where

is the instantaneous pitch angle, A is the oscillation amplitude, and

is the pitch motion frequency. However, it is fully acknowledged that in real-world operating conditions, floating platforms are subjected to complex, stochastic motion responses driven by coupled wave–wind–current interactions. To address this limitation, future work will extend the present framework by incorporating fully coupled time-domain platform responses using co-simulation tools. This will allow for evaluating wake evolution, power fluctuations, and fatigue loading under more realistic sea states and turbulent inflows. The instantaneous angle of attack,

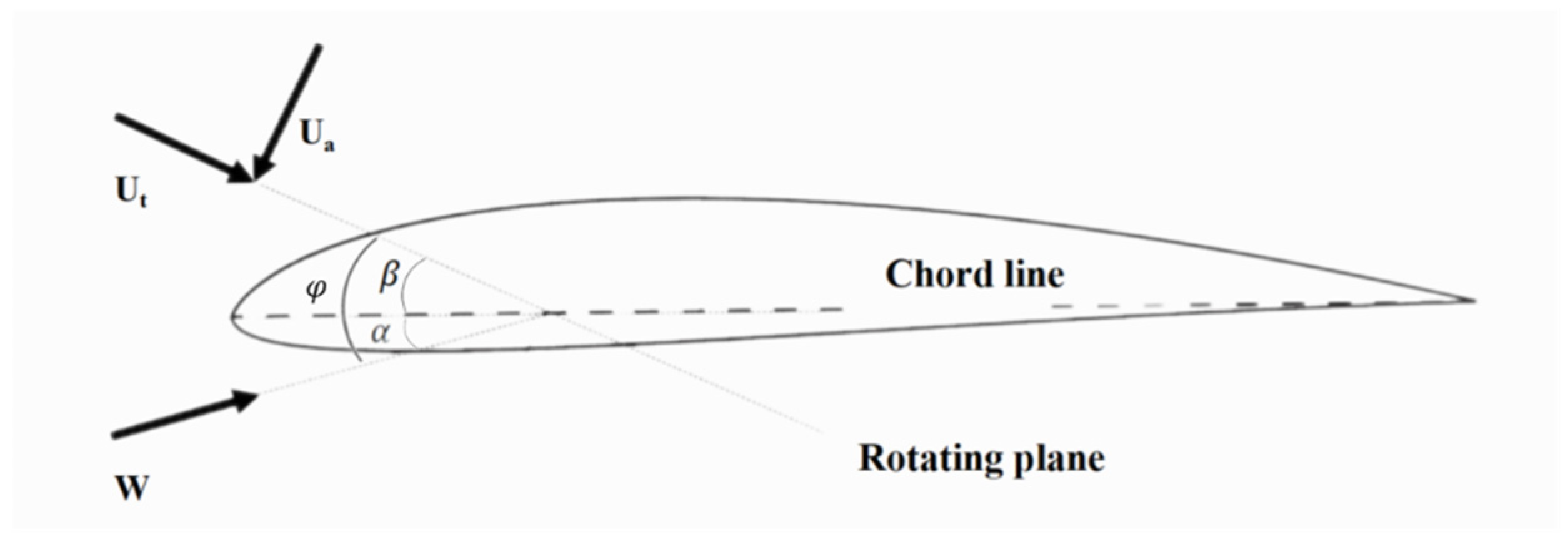

which governs rotor aerodynamic loading, is dynamically modulated by platform-induced motion. Its temporal evolution is described as follows:

where

is the attack angle of blade element,

is the inflow angle of blade element,

is the blade element twist angle, the axial wind speed represented by

,

represents the tangential wind speed at the position of blade element,

is the radius of blade element,

is resultant wind speed, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The imposed pitch oscillation of the floating platform causes the inflow angle

to vary periodically, which in turn drives time-varying fluctuations in

. These oscillations directly modulate the blade’s aerodynamic lift and drag characteristics, leading to unsteady thrust generation and dynamic wake behavior downstream [

27].

Subsequently, the simulation of wake interactions within the wind farm is carried out using FAST.Farm v3.1.0, a high-fidelity tool designed for floating wind turbine arrays. The wake dynamics are modeled using the Dynamic Wake Meandering (DWM) framework. This model accurately captures power performance by resolving the essential wake excitation mechanisms, including velocity deficit decay, wake meandering, and turbulence-induced diffusion. The DWM model employs a scale-separation approach, in which turbulent structures are categorized by size relative to the rotor diameter. Small-scale turbulence (scales less than 2D) primarily governs wake recovery, while large-scale eddies (greater than 2D) are responsible for wake meandering, as illustrated in

Figure 2(red indicates regions of freestream recovery and shear-layer activity, blue shows the velocity deficit induced by the rotor, purple highlights coherent vortex structures like tip and hub vortices, and orange lines trace the wake centerline and meandering).

The rotor of a wind turbine induces a velocity deficit and a corresponding pressure rise immediately upstream of the rotor disk. In the near-wake region downstream, coherent vortex structures begin to break down, pressure relaxes toward ambient levels, and the velocity deficit deepens, accompanied by radial wake expansion. Further downstream, the velocity deficit in the far-wake region evolves into a structure that is approximately Gaussian in shape. Here, wake recovery occurs via momentum exchange through the shear layer, where turbulent mixing transports momentum from the surrounding freestream into the wake core. This gradual recovery of flow speed toward freestream conditions is known as wake decay. In most implementations of the Dynamic Wake Meandering (DWM) model, the evolution of the wake deficit is governed by a thin shear layer approximation of the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes equations under axisymmetric and quasi-steady assumptions. Turbulent mixing is captured using a turbulent eddy-viscosity formulation that depends on local small-scale vorticity. It is important to note that this wake decay formulation is primarily valid in the far-wake region. This zone is particularly critical for wind farm performance assessment, as turbines in utility-scale arrays are generally spaced far enough apart that downstream units predominantly operate within the far wake of upstream machines.

Accurate simulation of wind farm wake behavior requires high-fidelity computational tools capable of resolving fine-scale flow structures. In this study, the STAR-CCM+ v18.04.008 software package is employed to simulate forced high-frequency pitch oscillations in a floating wind farm environment. The turbine model used is the NREL 5MW reference wind turbine [

28], as illustrated in

Figure 3. The computational domain is defined as 3D × 3D × 9D (D is the rotor diameter). To facilitate a focused comparison of platform-induced wake dynamics, a uniform steady inflow of 11.4 m/s was used in this study. In future work, the inflow profile will be extended to include more realistic atmospheric boundary layer characteristics (e.g., logarithmic wind profiles) to better reflect operational wind farm conditions. The boundary conditions are set as a velocity inlet and a pressure outlet for the downstream boundary. To ensure adequate resolution of the blade aerodynamics and wake development, mesh refinement is applied around the blades and the hub region, as shown in

Figure 4. In addition, a refined downstream wake zone is introduced to improve the accuracy of wake trajectory tracking, as depicted in

Figure 5. This localized mesh refinement ensures reliable capture of wake dynamics under unsteady platform motion.

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of the numerical results, a grid independence examination was conducted. This verification assesses the sensitivity of blade power output to mesh resolution by comparing results across grids of varying densities. As shown in

Figure 6, three computational meshes were generated using a global refinement strategy, containing approximately 5.5 million (G1), 8.55 million (G2), and 16.0 million (G3) cells, respectively. The turbine power output under identical operating conditions was used as the primary comparison metric to evaluate convergence behavior. As shown in

Figure 5, the simulation results were benchmarked against the NREL 5MW reference turbine data [

29], demonstrating good agreement and validating the mesh fidelity for subsequent wake flow analysis.

When using the coarsest mesh (5.5 million cells, G1), the power output deviated by 11.5% compared to the references data, indicating insufficient resolution. Upon refining the mesh to 8.55 million cells (G2), the power deviation significantly decreased to 4.4%. Further refinement to 16.0 million cells (G3) resulted in a marginal improvement shows 2.3%, with a power deviation of 3% relative to G2, suggesting that the results had effectively converged.

Considering the trade-off between computational accuracy and cost, the G2 mesh with 8.55 million cells was selected for all subsequent simulations. It offers a good balance between numerical precision and computational efficiency. In the selected G2 grid, the minimum cell size on the blade surface is set to 0.05D. The time step corresponds to a 1° azimuthal rotation of the turbine blade, i.e., 0.013774 s, ensuring that the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL) number remains below 1, which is essential for temporal stability and resolution in unsteady flow simulations.

To further explore the influence of 6-DOFs platform motions on the aerodynamic coherence of floating wind farms, an additional set of simulations was conducted using a simplified modeling approach. As this part of the study focuses on capturing the overall flow dynamics and wake interactions among the wind farm rather than resolving high-fidelity flow structures, the computational cost was significantly reduced by employing the FAST.Farm tool. The tool operates under steady inflow conditions with a constant wind speed of 11.4 m/s and incorporates the DWM model to simulate wake behavior. This allows for the real-time coupling of rotor aerodynamics with wake propagation characteristics, enabling dynamic evaluation of the effects of platform motion on wake deflection, velocity deficit, and turbulence intensity evolution [

30].

The 6-DOFs motion amplitudes and frequencies used for each platform type (Semi-submersible, Spar, TLP, and Mnpl) were derived from the NREL OC3, OC4, and OC5 benchmark studies [

31,

32,

33]. All turbines in the simulation array are modeled using the NREL 5MW reference turbine, with relevant specifications summarized in

Table 1.

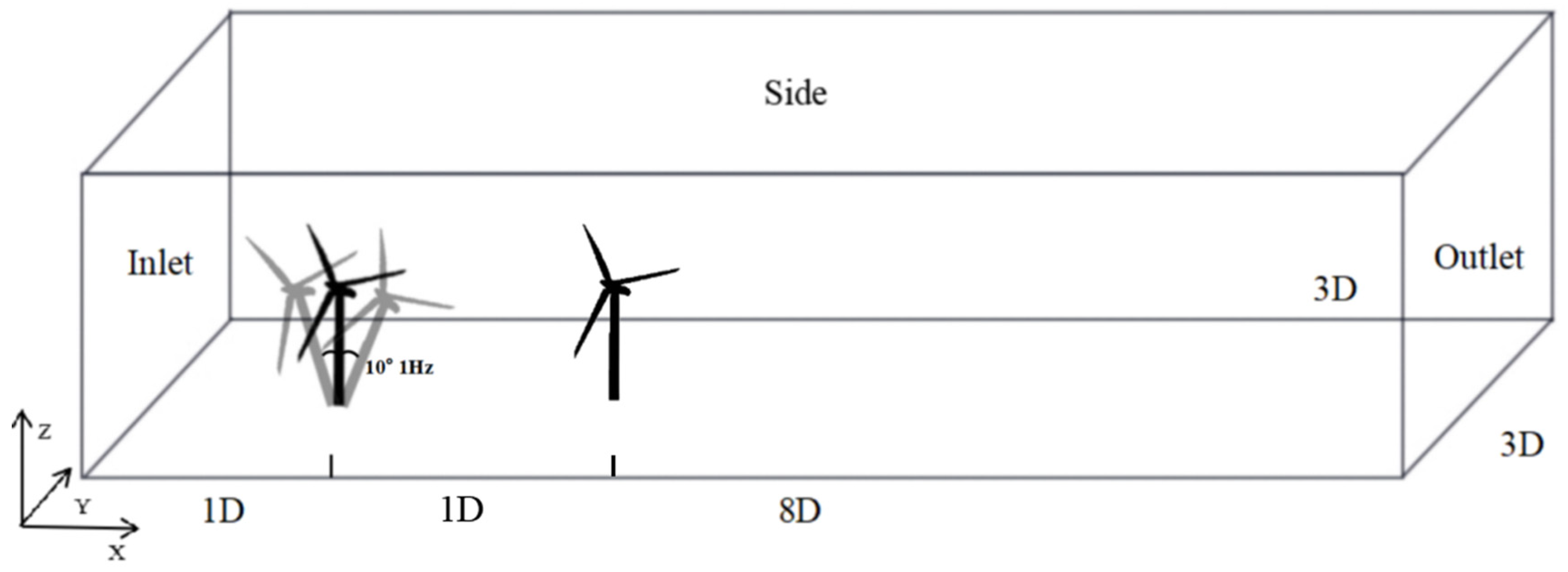

As illustrated in

Figure 7, the computational domain in FAST.Farm spans 3D × 3D × 19D. A steady inflow wind speed of 11.4 m/s (the rated wind speed of the NREL 5MW turbine) is applied along the X-direction, which corresponds to the wind flow direction. Two levels of mesh resolution were adopted: a coarse mesh with a grid size of 10 m and a fine mesh with 5 m resolution in regions requiring enhanced accuracy. The time step is set to 0.0125 s, ensuring adequate temporal resolution of the wake dynamics. In the simulation setup, the upstream turbine is configured as one of four floating platforms (Semi-submersible, Spar, TLP, and Mnpl) each with characteristic 6-DOF motions. The downstream turbine is a fixed turbine aligned in tandem with the upstream rotor. The streamwise spacing between the turbines is 8D, providing sufficient wake development while enabling wake–wake interaction studies.

3. Influence of Pitch Motion on Downstream Turbines

When a floating wind turbine undergoes dynamic pitch motion, the inflow conditions at the rotor plane differ significantly from those of a fixed-bottom turbine. As the pitch angle changes over time, the inflow conditions at the rotor plane also vary, particularly within the atmospheric boundary layer. These time-dependent inflow variations influence the aerodynamic loads on the rotor, affect power generation, and modify the downstream wake structure. In this section, we perform a theoretical analysis to investigate how periodic pitch oscillations influence the wake evolution and the aerodynamic response of downstream turbines. The aim is to clarify the impact of platform-induced motions on wind farm performance, including power fluctuations, aerodynamic coherence, and wake recovery dynamics.

To investigate the influence of platform pitch motion on the wake field of floating offshore wind turbines, a comparative CFD study was conducted under a turbulent wind inflow of 11.4 m/s and a rated rotor speed of 12.1 rpm. The simulations included a fixed-bottom wind turbine and a floating turbine subjected to a sinusoidal platform pitch motion with an amplitude of 10° and frequency of 1 Hz. As shown in

Figure 8, the wake patterns at the XY plane reveal distinct differences between the two cases. The wake behind the fixed-bottom turbine exhibits a relatively symmetric and organized shear flow structure. The velocity deficit is concentrated, and the wake remains stable with a narrow, quasi-axisymmetric core. The core region extends downstream with a gradual recovery in velocity, indicating low turbulence and minimal perturbations introduced into the flow. In contrast, the floating turbine wake displays a highly fragmented structure, with evident distortion, deflection, and velocity fluctuations. The shear layers deviate from their parallel development, suggesting that the platform motion introduces significant unsteady disturbances. From 2D to 5D downstream, the wake expands rapidly, indicating that pitch-induced lateral motion enhances wake width and unsteadiness. The low-velocity core spreads faster downstream, leading to accelerated momentum recovery, albeit accompanied by stronger velocity oscillations and unstable structures. The periodic pitch motion causes the entire wake trajectory to oscillate, resulting in rapid wake broadening, especially between 3D and 4D, where a fan-shaped expansion becomes pronounced. This enhanced diffusion is attributed to increased lateral vorticity generated by platform motion. The floating turbine wake is characterized by stronger three-dimensional disturbances and a more chaotic velocity vector distribution, reflecting the coupling between pitch-induced blade–flow interactions and shear-layer instabilities. The high-frequency pitch motion modulates the relative angle of attack cyclically at the rotor, inducing wake velocity fluctuations and coherent wake structures downstream. These oscillations give rise to streamwise banded structures and wake meandering, emphasizing the critical role of pitch dynamics in shaping wake morphology.

Figure 9 presents the time-averaged velocity distributions across the YZ plane at downstream locations from 0 D to 8 D. Compared to the fixed-bottom turbine, the wake of the floating turbine exhibits pronounced instability, with the central velocity deficit core undergoing periodic fluctuations. Wake symmetry is visibly disrupted, accompanied by enhanced lateral and vertical spreading of the low-velocity region. These effects are attributed to platform-induced oscillations in inflow velocity and dynamic displacement of the wake transport path. The periodic motion intensifies shear non-uniformity and turbulence in the near-wake vortex core, accelerating wake diffusion and energy recovery. This behavior has important implications for downstream turbine loading and fatigue response, and should be considered in array layout and control strategy design.

To quantitatively assess whether the wake field carries periodic disturbances and how these disturbances influence downstream turbines, power spectral density (PSD) analysis was conducted on the power output of the upstream turbine (T1) and downstream turbine (T2).

Figure 10a presents the PSD spectra for the generator torque of T1 (red curve), T2 (blue curve), and the imposed pitch motion on T1 (green curve), spanning a frequency range from 0 to 2 Hz. As shown in

Figure 10a, the imposed pitch signal exhibits a pronounced spectral peak near the input frequency of 1 Hz, indicating that this frequency dominates the actuation. The generator torque of T1 also shows a strong spectral peak at the same frequency, confirming that the forced pitch oscillation substantially modulates the relative angle of attack on the blades. This modulation cyclically alters the aerodynamic loading on the rotor, producing torque fluctuations synchronized with the pitch input. Notably, the torque signal of the downstream turbine T2 exhibits a significant increase in spectral energy at 1 Hz as well. This finding indicates that the periodic aerodynamic excitation induced by the pitch motion of T1 is effectively transferred through the wake, causing T2 to exhibit power fluctuations phase-aligned with the upstream excitation. Further validation is provided by

Figure 10b, which illustrates the PSD analysis of the rotor thrust on T2 when operating under free motion in the wake of a pitching T1. A distinct spectral peak at 1 Hz is again observed, confirming that the 1 Hz periodic energy embedded in the wake has propagated downstream and manifests in the aerodynamic response of the following turbine. Together, these results conclusively demonstrate that pitch motion imposed on the upstream turbine introduces a coherent periodic disturbance into the wake flow. This disturbance affects both the aerodynamic behavior of the upstream rotor and produces frequency-specific features in the power and loading responses of downstream turbines. These findings underscore the necessity of accounting for platform-induced dynamic motion when modeling wake evolution and evaluating the performance of downstream units in floating wind farms.

Under an inflow velocity of 11.4 m/s and a rotor speed of 12.1 rpm, a sinusoidal pitch motion with a frequency of 1 Hz and an amplitude of 10° was imposed on the upstream turbine (T1). Frequency-domain analysis successfully identified distinct spectral peaks at 1 Hz in both the torque and thrust responses of the upstream (T1) and downstream (T2) turbines. This confirms the ability of the imposed pitch motion to modulate aerodynamic loads and demonstrates the existence of periodic disturbances within the wake that propagate downstream and influence the dynamic responses of following turbines. These findings provide critical insight for the design of wake control and array-level coordination strategies.

In summary, both time-averaged flow fields and spectral energy analyses reveal the modulation mechanisms through which platform-induced pitch motion alters wake structure and its downstream propagation characteristics. The results indicate that periodic pitching not only disrupts wake symmetry, accelerates velocity recovery, and enhances unsteady diffusion, but also generates flow structures that retain the disturbance frequency and transmit coherent energy downstream throughout the wind farm array.

4. Analysis of Wake Characteristics Across Different Floating Wind Turbine Types

The preceding analysis demonstrated that periodic pitch motion in upstream turbines introduces corresponding periodic disturbances into the wake field, which subsequently affects the inflow conditions experienced by downstream turbines. These changes modulate the aerodynamic performance and induce periodicity in the response of the downstream turbines. To further investigate these effects, this section extends the study from single-degree-of-freedom (pitch) motion to full 6-DOFs free motion. The scope is expanded from semi-submersible floating wind farms to mixed configurations composed of four different upstream turbine types: semi-submersible (Semi), tension-leg platform (TLP), spar-buoy (Spar), and monopile (Mnpl, representing fixed-bottom turbines). The simulation setup for each scenario is summarized in

Table 2, with all cases operating under a uniform inflow velocity of 11.4 m/s and a rotor rotational speed of 12.1 rpm. In all cases, the downstream turbine (T2) remains a fixed-bottom monopile turbine, while the upstream turbine (T1) varies in platform type. The spatial layout of the tandem arranged turbines is shown in

Figure 7. Each case is named after the T1-T2 configuration. The aim is to assess how different upstream platform dynamics—specifically pitch, roll, and yaw motions—affect wake evolution, inflow conditions for downstream turbines, aerodynamic performance, and overall power generation.

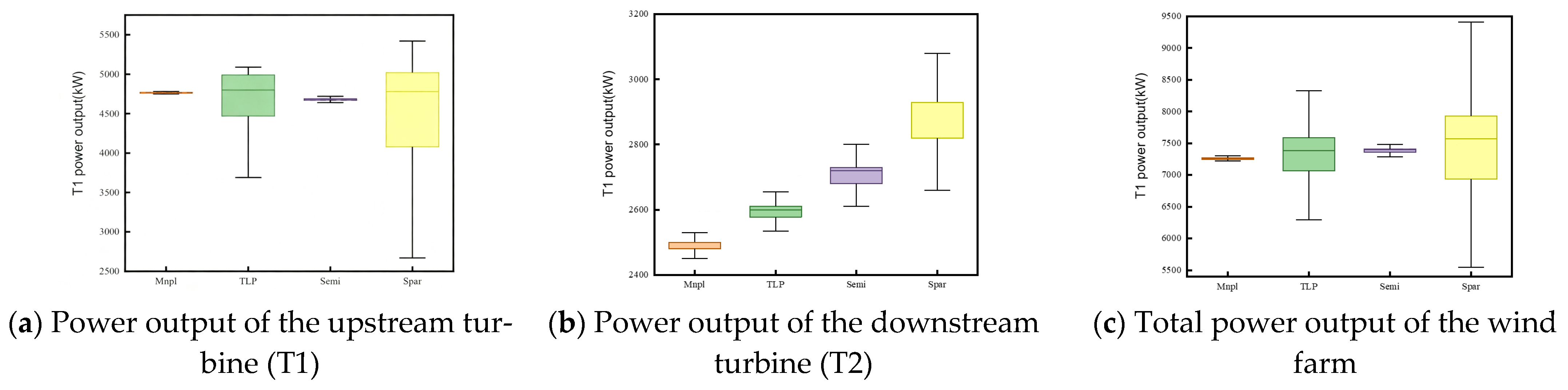

In

Figure 11a, Case1 (Mnlp-Mnlp) yields the highest median power output for T1, suggesting superior energy conversion efficiency and operational stability. Its compact box length further implies minimal power variability. In contrast, T1 in Case4 (Spar-Mnlp) displays the lowest median and the widest distribution, highlighting poorer efficiency and increased unsteadiness. Case3 (Semi-Mnlp) shows better performance stability than Case4 due to its higher hydrodynamic damping and improved platform stability, with slightly higher median values. Case2 (TLP-Mnlp) displays similar median output to Case1 but with greater variability, indicating reduced consistency. In

Figure 11b, an inverse trend is observed for the downstream turbine T2. Despite T1 in Case1 (Mnlp-Mnlp) producing the highest power, T2 exhibits the lowest median output. In contrast, T2 in Case4 (Spar-Mnlp) records the highest values among all cases. This suggests that the periodic motion of the upstream floating platform introduces additional wake mixing that enhances the inflow condition for the downstream turbine. The Case3 (Semi-Mnlp) falls between these extremes.

Figure 11c illustrates the total wind farm power output for all cases. The results indicate that Case4 (Spar-Mnlp) achieves the highest total mean and peak values, despite its upstream instability. This outcome underscores the complex interplay between upstream platform motion, wake diffusion, and downstream power recovery. Overall, the comparative box plot analysis reveals that platform-induced dynamics in the upstream turbine significantly influence wind farm-level performance. Even under identical rated inflow conditions and identical downstream turbines, the upstream platform type leads to notable differences in both power generation efficiency and stability across the wind farm.

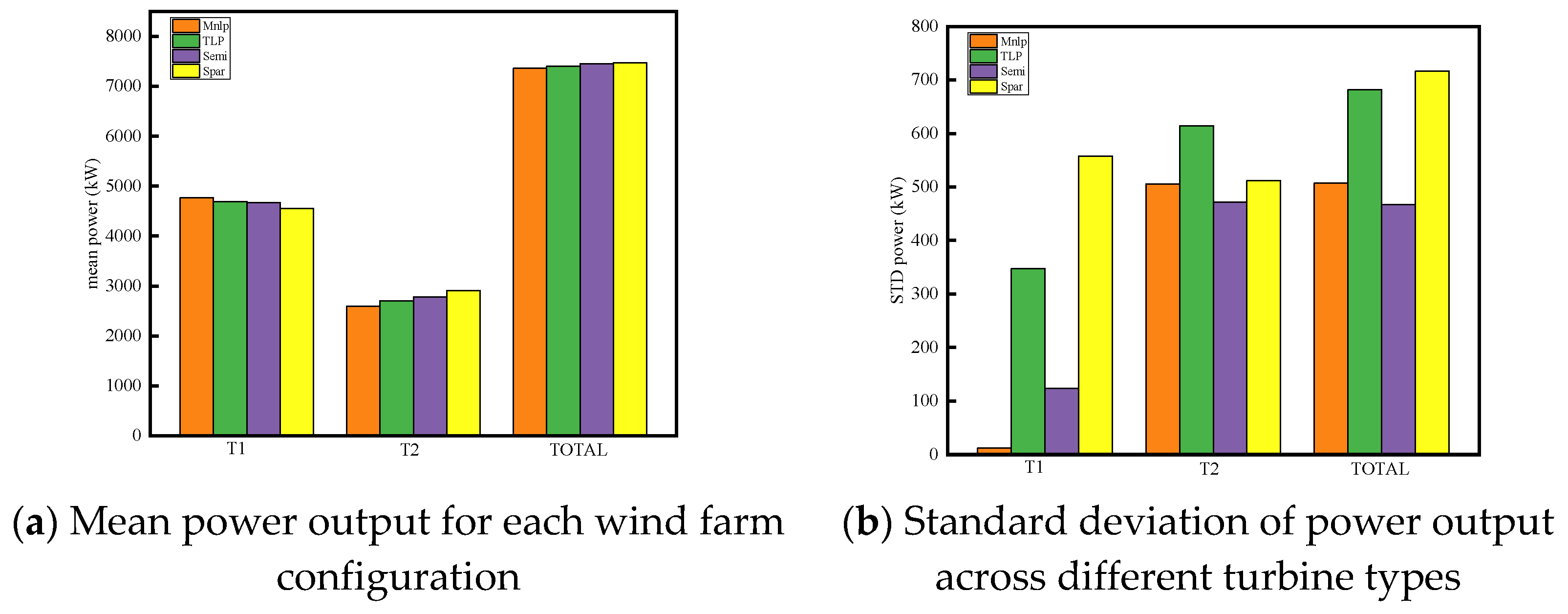

To further evaluate the impact of platform type on wind farm performance, statistical analyses of the mean and standard deviation of power output were conducted for all four wind farm configurations, as shown in

Figure 12. Consistent across all cases, the upstream turbine (T1) exhibits higher average power output than the downstream turbine (T2). This disparity is attributed to the well-known wake effect, where the upstream turbine extracts a portion of the incoming wind energy, thereby reducing the wind speed and increasing turbulence intensity in the downstream region. As a result, the aerodynamic conditions experienced by the downstream turbine deteriorate, leading to power deficits.

Figure 12a presents the mean power output for each configuration. Notably, the downstream turbine in Case 4 (Spar-Mnlp) exhibits the highest mean power output among all cases, suggesting a faster wake recovery rate for Spar type floating wind turbine. This improved performance is likely due to the larger amplitude of platform motion associated with Spar-type floating wind turbines, which enhances wake mixing and turbulence diffusion, thereby facilitating energy recovery in the wake region. The Semi-submersible configuration (Case 3) follows closely, outperforming both the Monopile (Case 1) and TLP (Case 2) configurations in terms of downstream turbine output. These findings suggest that, under certain conditions, floating platforms with larger motion amplitudes may enhance wake mixing, leading to improved downstream flow conditions and greater power extraction by downstream turbines.

Figure 12b illustrates the standard deviation of power output. As expected, Case 1 (Monopile) shows the lowest power fluctuations, owing to motion stability of fixed-bottom turbines. In contrast, the Spar configuration (Case 4) exhibits the highest power variability for the upstream turbines, a consequence of its pronounced 6-DOFs motion. Overall, the Spar wind farm displays the greatest total power variability, whereas the Monopile and Semi-submersible configurations exhibit relatively moderate fluctuations. From an engineering perspective, both power efficiency and output stability must be considered, as excessive variability may lead to intensified structural fatigue and reduced wind farm lifespan.

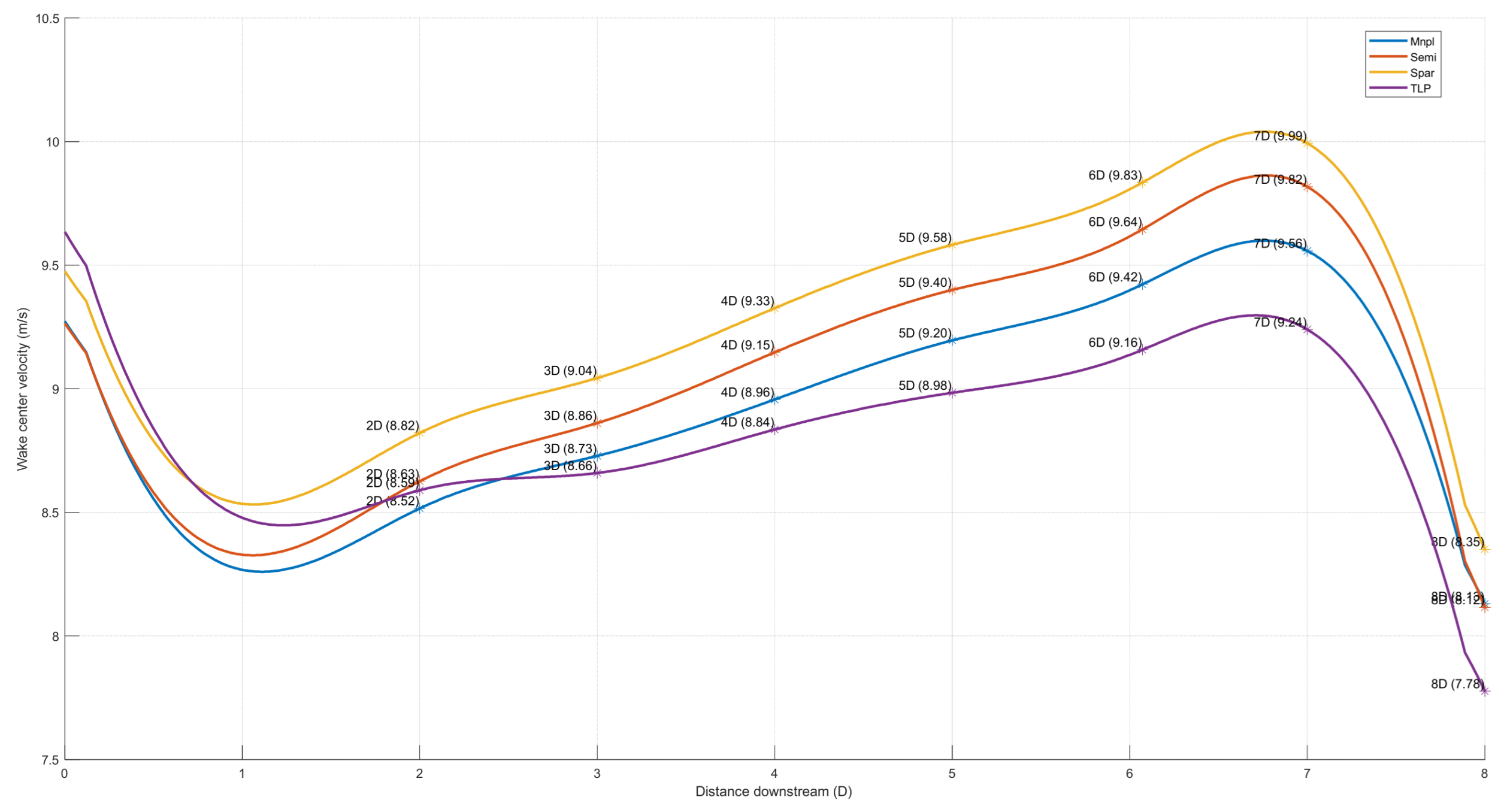

To quantitatively assess the wake evolution associated with each platform type,

Figure 13 presents the streamwise variation of centerline velocity. The general trend exhibits a characteristic single-peak profile, wherein the wake velocity initially decreases and subsequently recovers downstream. A local maximum is observed near 7D, followed by a slight decline attributed to the influence of the downstream turbine. In the near-wake region (0–2D), all configurations show a pronounced velocity deficit, primarily caused by rotor-induced kinetic energy extraction. This is followed by progressive velocity recovery beginning beyond 1D, driven by enhanced turbulent diffusion within the shear layer. Among the platform types, the Semi-submersible and Spar-buoy configurations exhibit superior wake recovery behavior. From 2D to 7D, they consistently maintain higher centerline velocities compared to the Monopile and TLP designs. The Spar platform, in particular, achieves a peak wake velocity of 9.9 m/s at 6D–7D, suggesting a more favorable inflow environment for downstream turbines. This improved recovery is likely due to enhanced asymmetric wake dispersion triggered by its characteristic platform motion. In contrast, the Monopile and TLP configurations display delayed recovery, with centerline velocities remaining below 9.2 m/s at 6D. Notably, the TLP wake speed decreases to 7.76 m/s at 8D—the lowest observed among all cases—indicating greater wake energy loss and a potentially more adverse impact on downstream turbine performance. These differences underscore the significant role of platform motion dynamics in modulating wake behavior. These findings indicate that platform motion characteristics play a critical role in wake evolution. Fixed-bottom turbines, constrained by the absence of platform degrees of freedom, tend to generate more concentrated and persistent wake deficits, leading to delayed velocity recovery. In contrast, floating turbines introduce additional flow disturbances through platform motion, which can promote enhanced wake dispersion and facilitate energy redistribution, thereby improving inflow quality for downstream turbines. Furthermore, a slight velocity dip is observed near 7D across all configurations. This secondary decline is attributed to reverse flow perturbations induced within the induction zone of the downstream turbine, resulting in a localized blockage effect. The presence of this feature underscores the importance of accurately evaluating the spatial overlap between upstream wakes and downstream induction zones in array layout design, particularly for optimizing inter-turbine spacing. In summary, the Semi-submersible and Spar platforms demonstrate superior wake mitigation and downstream compatibility, suggesting inherent advantages for array configuration and overall wind farm performance.

Figure 14 further investigates the spatial trajectory of wake centers under different turbine platform configurations to elucidate the underlying factors influencing wake dispersion. The X-axis corresponds to the primary flow direction, along which wake centers advance while gradually deviating in both the lateral (Y) and vertical (Z) planes. In the near-wake region (0–4D), the wake centerlines remain relatively concentrated. However, from 4D to 8D, wake dispersion intensifies due to cumulative perturbations. For the fixed-bottom turbine (blue), the wake centerline exhibits minimal deviations in both lateral and vertical directions, maintaining a relatively organized jet-like profile. This stability is likely attributable to the absence of platform degrees of freedom, which restricts motion-induced disturbances. The overall wake behavior observed here aligns with the recovery trend previously shown in

Figure 13. In contrast, the Tension Leg Platform (TLP, purple) displays intermittent large vertical excursions in the near-wake region (0–2D), indicating transient instability. However, beyond 2D, its wake centerline becomes less dispersed than that of the fixed-bottom case. The Semi-submersible (orange) platform produces even greater deviations, and the Spar platform (yellow) exhibits the strongest wake meandering, with substantial lateral and vertical displacement throughout the wake development. This pronounced instability suggests weaker suppression of platform-induced perturbations, potentially linked to the flexible structural response and intensified fluid–structure interactions inherent to Spar-type designs. These findings complement the results from

Figure 13, wherein enhanced wake diffusion correlates with accelerated mixing and velocity recovery—beneficial for reducing the length of low-speed wake zones and enabling downstream turbines to regain inflow quality earlier. However, such wake broadening also increases turbulence intensity within the wake region, elevating the risk of fatigue loading on downstream turbines due to more frequent velocity fluctuations. This dynamic is reflected in the power variability observed in

Figure 11. Therefore, while wake dispersion may enhance mean power capture, it also poses structural challenges. Optimizing turbine arrangement thus requires a balanced assessment of both power performance and fatigue implications to identify the most effective platform combination.

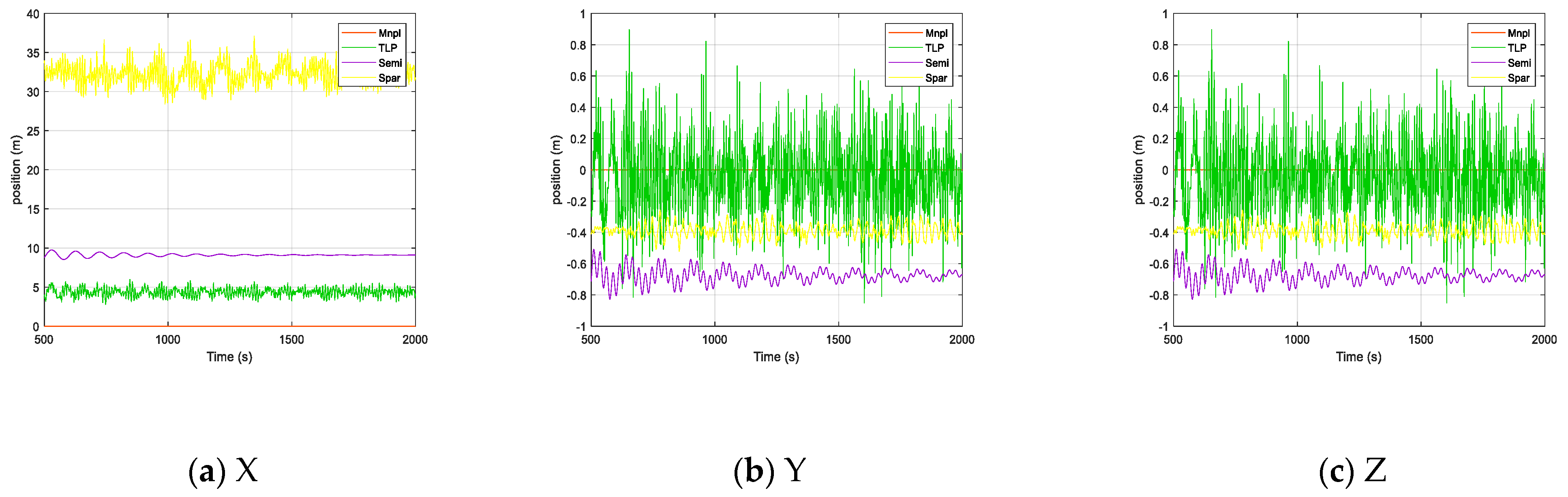

Figure 15 presents the time histories of three primary degrees of freedom—pitch, surge, and yaw—for wind turbines mounted on Mnpl, Semi-submersible, TLP, and Spar platforms, under a uniform inflow velocity of 11.4 m/s. These free-motion responses reveal the distinct dynamic characteristics of each platform type and their potential influence on rotor inflow conditions and wake development. In the pitch direction, the Spar platform exhibits the most pronounced oscillatory response, characterized by large-amplitude, high-frequency fluctuations reaching up to 6°. This indicates strong pitch motion under combined wind and wave excitation, which can lead to significant periodic variations in angle of attack, thereby modulating the near-wake structure. In contrast, the TLP platform maintains minimal pitch activity, offering stable rotor alignment. The Semi-submersible platform displays intermediate behavior, while the fixed-bottom Mnpl remains motionless, providing a steady inflow boundary. Pitch motion directly affects vertical wake perturbation, making it a key driver of wake deflection, energy dispersion, and asymmetrical wake propagation. In the surge direction, the Spar platform again demonstrates the most substantial longitudinal displacement, with amplitudes up to 25 m. The Semi-submersible platform follows with moderate oscillations, while the TLP platform shows larger amplitude but remains centered near a small mean displacement. The Mnpl platform shows no surge response. Longitudinal motion affects the relative inflow velocity and the wake’s axial evolution, introducing high-frequency velocity fluctuations that can significantly alter the loading on downstream turbines. For yaw motion, both the Spar and Semi-submersible platforms exhibit oscillations within ±0.5°, with the TLP showing higher intermittency, suggesting less stable heading control. The Spar platform displays minimal yaw response, and the Mnpl remains stationary. Although yaw motion does not directly modify the inflow speed, it perturbs blade angle of attack asymmetrically, leading to lateral wake displacement. Over time, such yaw-induced deviations can accumulate and alter the wake trajectory, especially in large wind farm arrays. Overall, each platform type introduces a distinct disturbance pattern into the wake field. The Spar platform, characterized by pronounced pitch and surge motions, induces strong vertical wake deflection and asymmetry in the near-wake region. The TLP platform primarily contributes to yaw-induced oscillatory wake deviations, while the Semi-submersible platform generates multi-directional disturbances of moderate amplitude. In contrast, the fixed-bottom Mnpl platform maintains a stable, symmetric, and concentrated wake due to its structural immobility. The structural configuration and motion characteristics of the platform fundamentally shape the dimensional scope and intensity of wake disturbances. These wake-induced variations, in turn, influence the uniformity of power output across the wind farm and impose fluctuating loads on downstream turbines. As a result, platform-induced dynamics become a critical factor that must be accounted for in the development of effective wind farm layout and array control strategies.

Figure 16 provides further analysis of the rotor displacement in the X, Y, and Z directions, clearly showing a strong correlation with the motion response of the supporting platform. Rotor movement significantly influences wake distribution and, consequently, the wake effect imposed by the upstream turbine on its downstream counterpart. Consistent with the observations from

Figure 10 and

Figure 11, Case 4 exhibits the largest rotor displacement at T1, corresponding with reduced wake interference and higher energy output for the downstream turbine. This suggests that intentionally modulating platform pitch and other motion modes, even if it slightly reduces upstream turbine efficiency, can enhance downstream turbine performance. These findings indicate that platform motion control could be a viable strategy for optimizing total wind farm power generation by managing coordinated aerodynamic interactions.

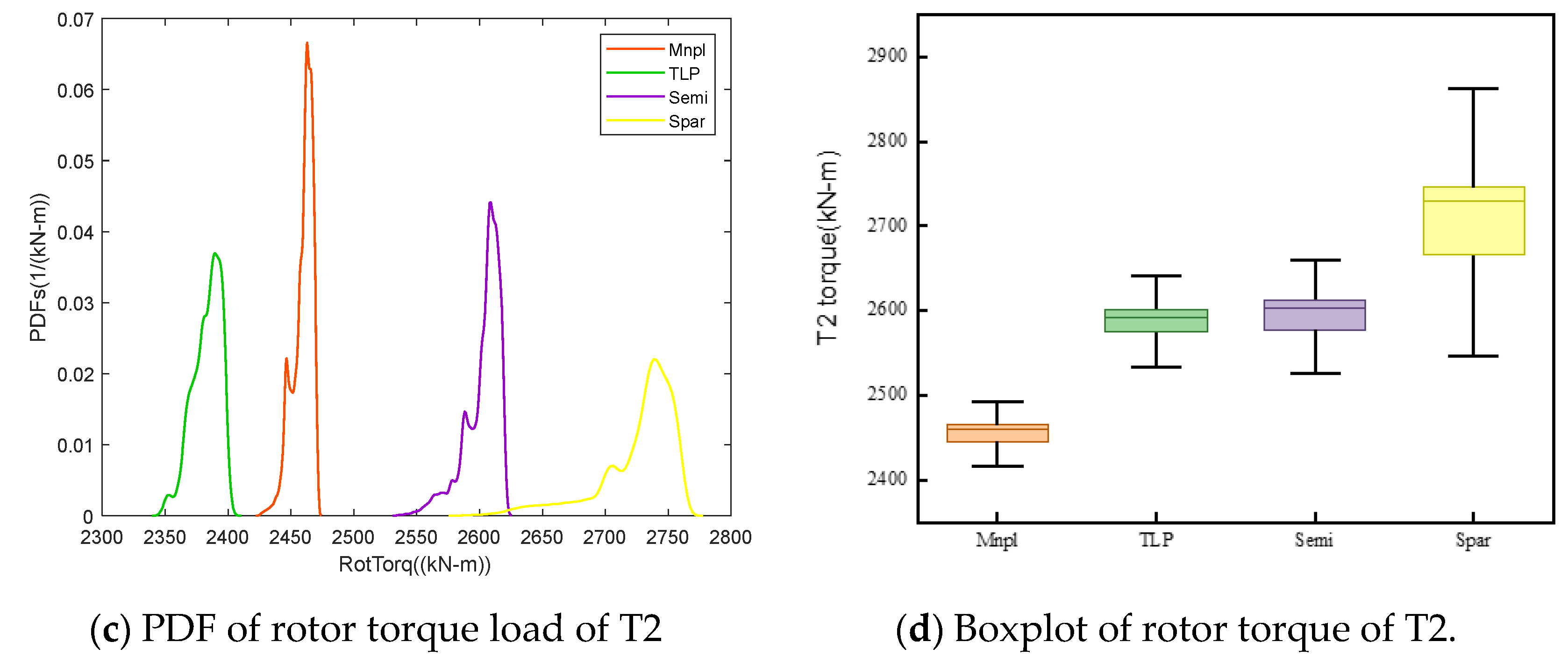

Wake effects not only lead to a substantial reduction in the mean inflow velocity experienced by downstream turbines but also amplify turbulence intensity and unsteady aerodynamic loading, thereby exacerbating structural fatigue responses. To systematically evaluate the dynamic and fatigue-driving impacts of wake-induced disturbances, this study employs key indicators including time histories of rotor thrust and torque, as well as probability density functions (PDFs) of their distributions.

Figure 17 presents a detailed analysis of rotor thrust and torque characteristics for downstream turbines across four different wind farm configurations. For clarity, each downstream turbine is referred to by the type of its corresponding upstream platform. Subplots

Figure 17a,c illustrate the probability density functions (PDFs) of thrust and torque, respectively, while subplots

Figure 17b,d provide boxplot statistics of these quantities. The four platform types are color-coded as follows: Mnpl (orange), TLP (green), Semi-submersible (purple), and Spar-buoy (yellow). As shown in

Figure 17a, the PDF of rotor thrust for the downstream turbine under the TLP platform (green curve) is positioned furthest to the left, with thrust values concentrated in the range of 4.25–4.45 × 10

5 N. Although the distribution is relatively broad, it exhibits a distinct peak, indicating that the downstream turbine experiences generally lower thrust loads with moderate variability. Similarly, the torque PDF under the TLP configuration, also situates at the very leftmost position (see

Figure 17c), centers around 2350 kN·m—the lowest among all cases—suggesting reduced energy capture. This is likely a result of the downstream rotor frequently operating within partially obstructed or deflected wake regions due to the limited but persistent motion of the upstream TLP platform. In contrast, the Mnpl (monopile) configuration (orange) shows a markedly sharper and taller thrust PDF, concentrated around 4.5–4.7 × 10

5 N, accompanied by the narrowest torque distribution centered at 2450 kN·m. These features reflect highly stable aerodynamic loading and minimal wake-induced perturbations, attributable to the platform’s rigid and fixed nature, which helps maintain consistent inflow and suppress wake meandering. For the Semi-submersible platform (purple), the downstream turbine exhibits a slightly right-shifted thrust PDF with broader distribution (4.7–5.05 × 10

5 N) and a lower peak, indicating higher variability in aerodynamic loads. Its torque PDF is also right-shifted, centered around 2600 kN·m, with a broader tail and occasional high-load outliers. These patterns are consistent with moderate platform motion, which introduces fluctuations in inflow height and local wake velocity, resulting in non-stationary torque behavior. The Spar platform (yellow) displays the most dispersed PDF characteristics. Both thrust and torque distributions are broad with long tails, low peak sharpness, and signs of multimodality. Thrust values range from 4.67 to 5.2 × 10

5 N, while the torque PDF peaks near 2700 kN·m and spans the widest interval, exhibiting significant asymmetry. These signatures point to a strong coupling of pitch and heave motions, which modulate wake altitude and velocity profiles over time. The downstream rotor therefore experiences dynamically varying flow conditions, resulting in complex, multimodal torque responses. Such behavior implies frequent cyclic loading, posing increased fatigue challenges for drivetrain components. In particular, the dominant pitch response of the Spar configuration induces vertical oscillations in the rotor plane, amplifying thrust and torque fluctuations through vertically non-uniform inflow.

Figure 17b,d further quantify the statistical distributions of rotor thrust and torque using box plots for the downstream turbines. The downstream turbine associated with the Spar platform (yellow) exhibits the highest median thrust, approaching 610 kN, along with the widest interquartile range and a maximum value nearing 660 kN. Similarly, the rotor torque boxplot shows that the Spar case features the highest median and peak values—reaching nearly 2800 kN·m—combined with the broadest distribution range. These metrics indicate the most pronounced load fluctuations and a high frequency of extreme values, consistent with the multimodal characteristics observed in its PDF distributions. This behavior is strongly attributed to the Spar platform’s pronounced coupled pitch and heave responses, which generate unsteady vertical and lateral wake deflections, resulting in periodic variations in rotor loading. The Semi platform (purple) yields a median thrust of approximately 590 kN, with a relatively compact interquartile range, indicating a moderate overall load level and reduced variability. This suggests that the platform exhibits milder motion dynamics, resulting in more controllable wake disturbances. In terms of rotor torque, the Semi platform occupies an intermediate position among the four configurations, with a median value ranging between 2600–2650 kN·m and a moderate spread. This reflects a well-balanced aerodynamic and structural response. The TLP platform (green) exhibits a median rotor thrust of approximately 545 kN, which is slightly lower than that of the Semi platform, and the range between its maximum and minimum values spans nearly 100 kN. The Mnpl platform (orange) displays the smallest interquartile range and a relatively low median thrust of approximately 555 kN in the box plots, indicating that the downstream turbine operates in the most stable inflow conditions. The thrust distribution is highly concentrated, and the load input is uniform, making it the most favorable configuration for load control. Additionally, the Mnpl platform shows the lowest median rotor torque, with the narrowest box and the smallest span between maximum and minimum values, further confirming that its torque input is the most consistent and its aerodynamic environment the most stable. In summary, the Spar platform exhibits the most intense platform-induced motions, resulting in large fluctuations and frequent extremes in downstream turbine thrust loads, thereby significantly increasing structural fatigue risks. In particular, its high-amplitude pitch motion induces vertical (Z-direction) wake deflections, generating vertically non-uniform inflow conditions that exacerbate dynamic loading. By contrast, the TLP and Mnpl platforms maintain more stable responses, leading to safer and more consistent operating conditions across the wind farm. The Semi-submersible platform offers a balanced trade-off, with moderate thrust levels and manageable variability, achieving a compromise between energy capture and load stability. Overall, the Spar platform’s complex motion characteristics cause strong wake disturbances, exposing downstream rotors to multimodal and high-amplitude torque fluctuations, making it the most critical in terms of fatigue-driven load accumulation. The Semi platform, by inducing moderate perturbations, offers a more favorable balance between structural resilience and aerodynamic performance. These findings underscore that the platform’s degrees of freedom and its wake disturbance dynamics are key determinants of downstream turbine loading behavior, and should pay attention to array layout planning and structural fatigue life design for floating offshore wind farms.