Effective Heat Transfer Mechanisms of Personal Comfort Systems for Thermal Comfort and Energy Savings: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

1.2. PCS Performance and Heat Transfer Mechanisms (HTMs)

1.3. Research Gap and Objectives

| Study | Number of Included Studies | Main Focus | Heat Transfer Mechanisms | Effect Size | TSV | OC | CP | CEP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Song et al. [9] | 34 | Effects of PCSs on occupants’ perceptual responses. | Discussed superficially. Did not analyze HTMs category-wise | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Xu et al. [28] | 25 | Effects of PCSs on sleep. | Discussed qualitatively | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Du and Ghahramani [29] | 83 | PCS performance and experiment design. | Discussed with TSV differences | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Rawal et al. [8] | 184 | Effectiveness, energy savings, and cost of PCSs. | Discussed qualitatively | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Cao and Xie [32] | 52 | Wearable device types and factors affecting user satisfaction. | Discussed qualitatively | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Warthmann et al. [33] | 59 | Summarized personal climatization systems’ research. | Discussed qualitatively | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Zhang et al. [25] | 41 | Quantifying ability of PCSs in providing comfort in various ambient temperatures. | Discussed qualitatively | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Luo et al. [4] | 32 | Effects of PCSs on local body segments in office settings. | Discussed qualitatively | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Exss et al. [16] | 120 | Classifying PCSs based on post-phenomenological mediation categories. | Discussed qualitatively | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Shahzad et al. [34] | 16 | PCSs’ ability to reduce energy, maintain comfort, and improve air quality. | Not discussed | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Search and Selection Criteria

- Human trials were conducted in laboratory settings under steady-state thermal conditions or lower thermal conditions on varying field studies.

- PCSs had to be implemented in indoor environments where participants were sitting, standing, or engaging in low-intensity activities (i.e., metabolic rate < 2.1 met).

- PCSs were required to be used in environments with high or low air temperatures, primarily aimed at achieving thermal comfort.

- Studies were required to be randomized controlled trials, where participants were assigned to either cooling/heating interventions or control trials.

- Studies had to report participants’ overall perceptual responses in thermal sensation vote, overall comfort, or thermal acceptability using widely accepted scales based on the body thermal state.

- Studies with a number of subjects higher than four people.

- Studies had to report thermal sensation, overall comfort, or thermal acceptability values in graphs on an accurate scale or in numbers with relevant and the same indoor air temperatures for conditions with and without PCSs.

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Classification of Heat Transfer Mechanisms (HTMs)

2.4. Thermal Comfort and Energy Performance

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Description of Data Analyzed

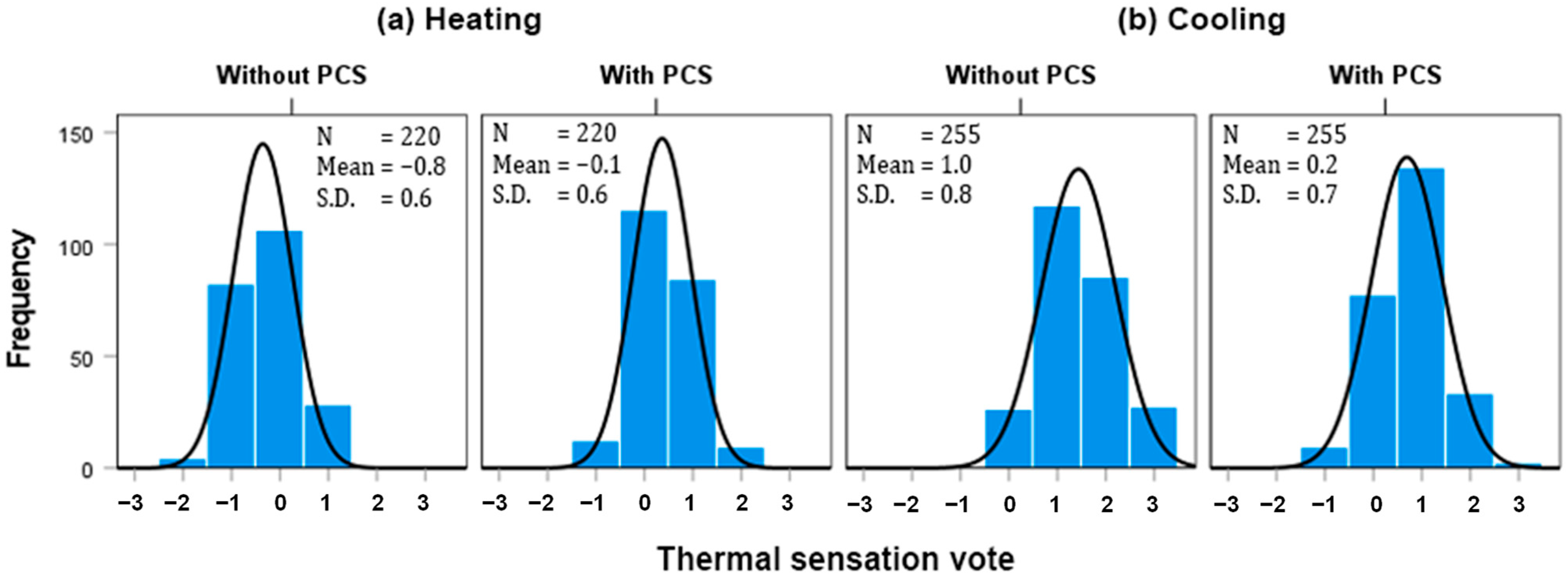

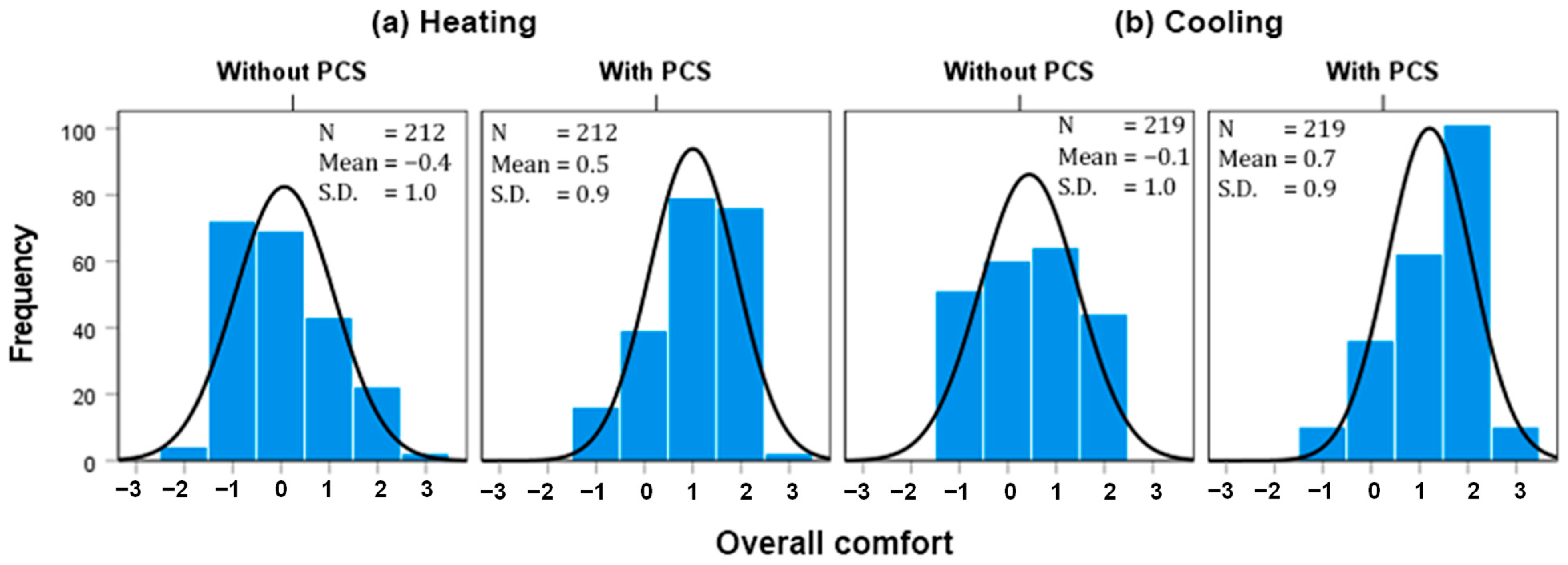

3.2. Overall Impact of PCSs on Perceptual Responses

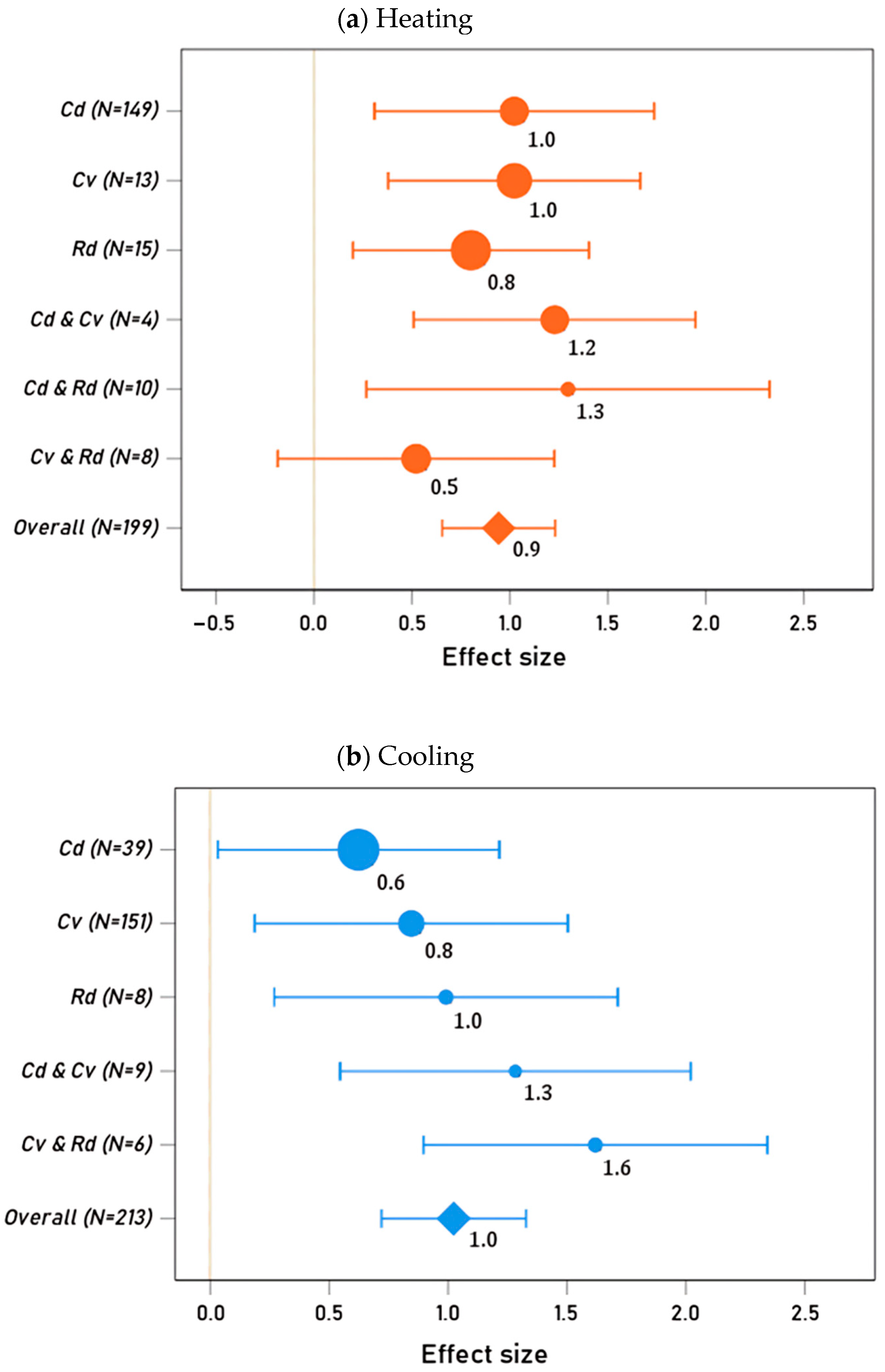

3.3. HTMs’ Impact on Thermal Comfort

3.3.1. Impact on TSV

3.3.2. Impact on OC

3.3.3. Relation Between TSV and OC Impact

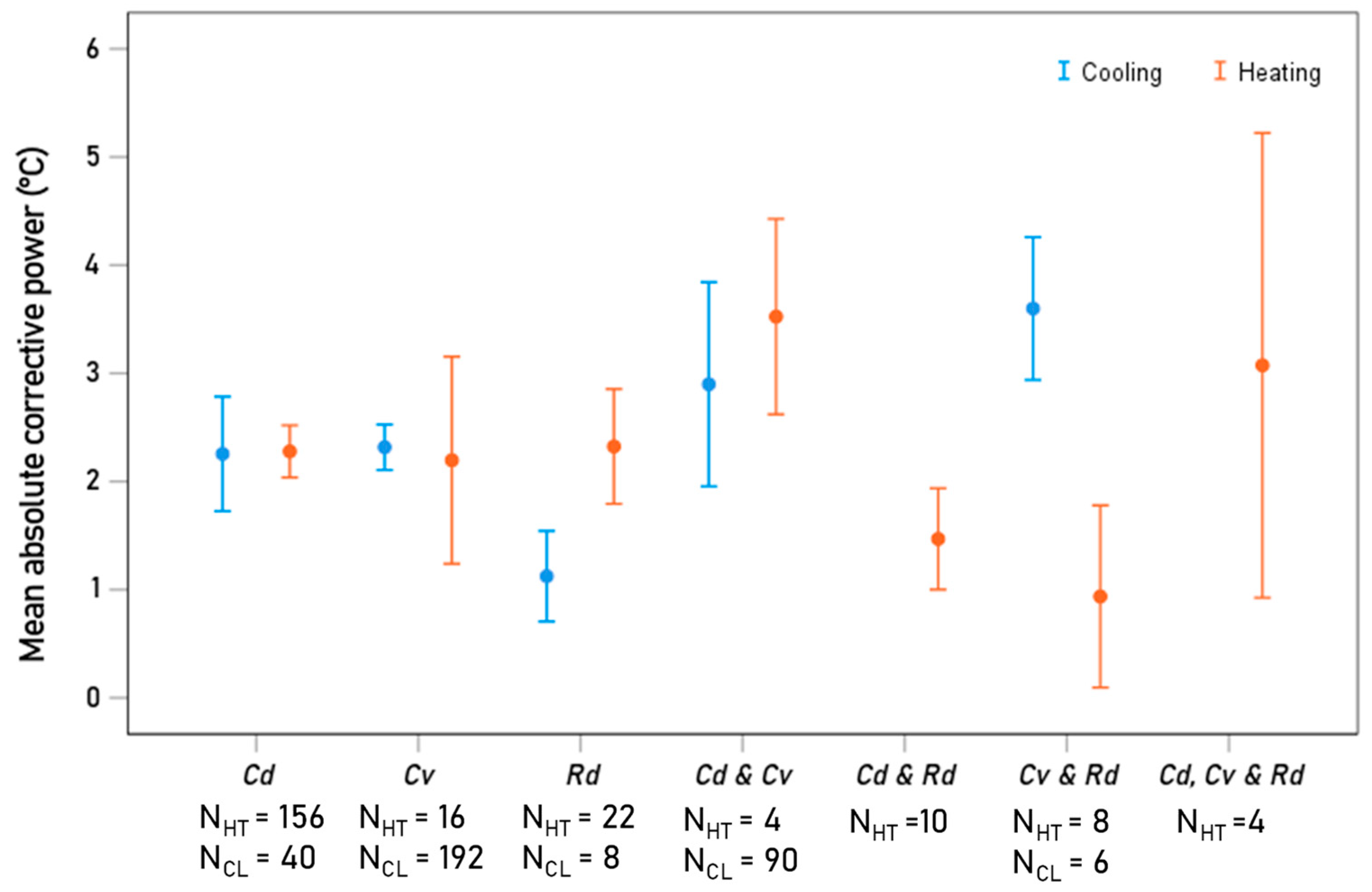

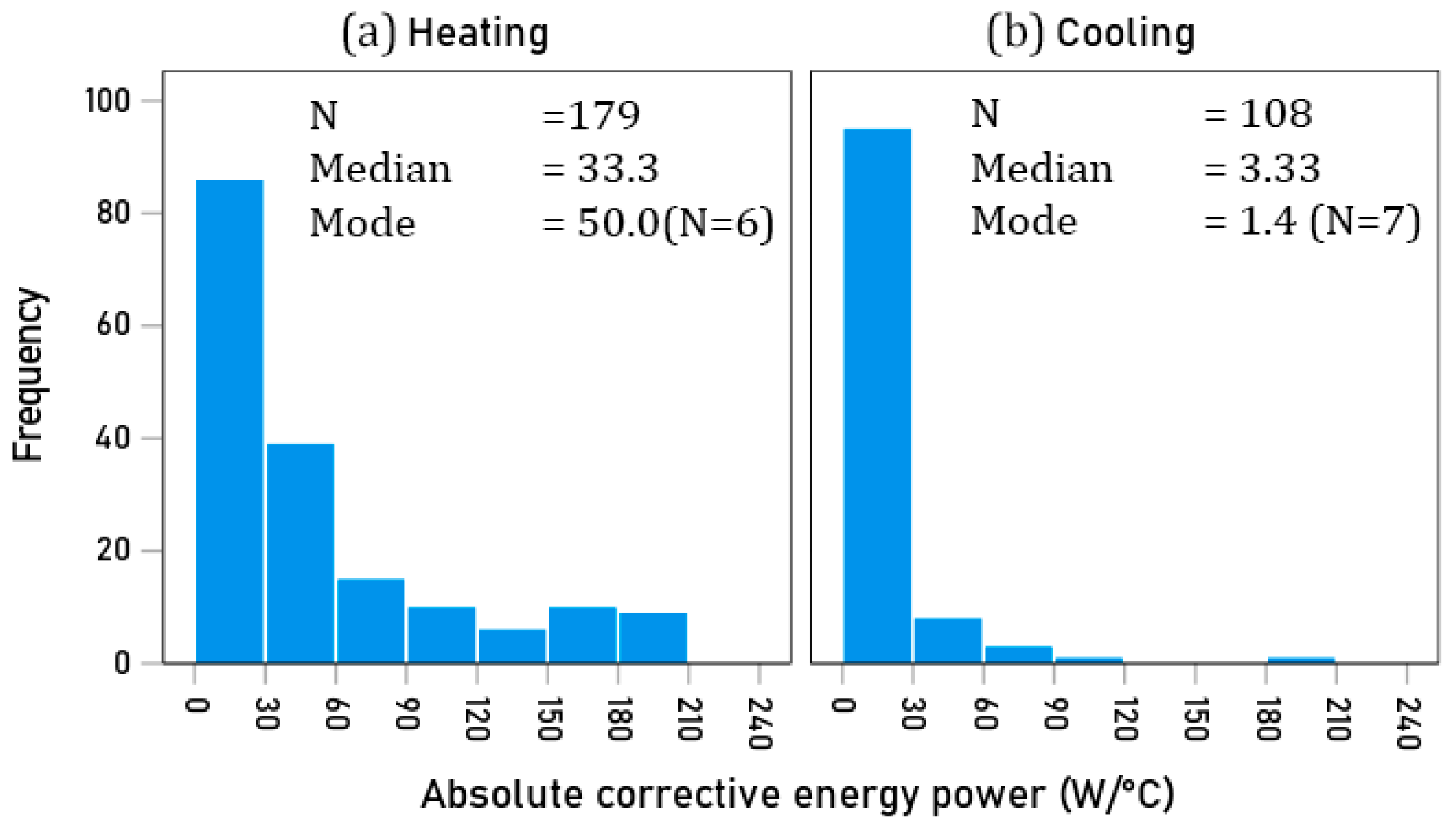

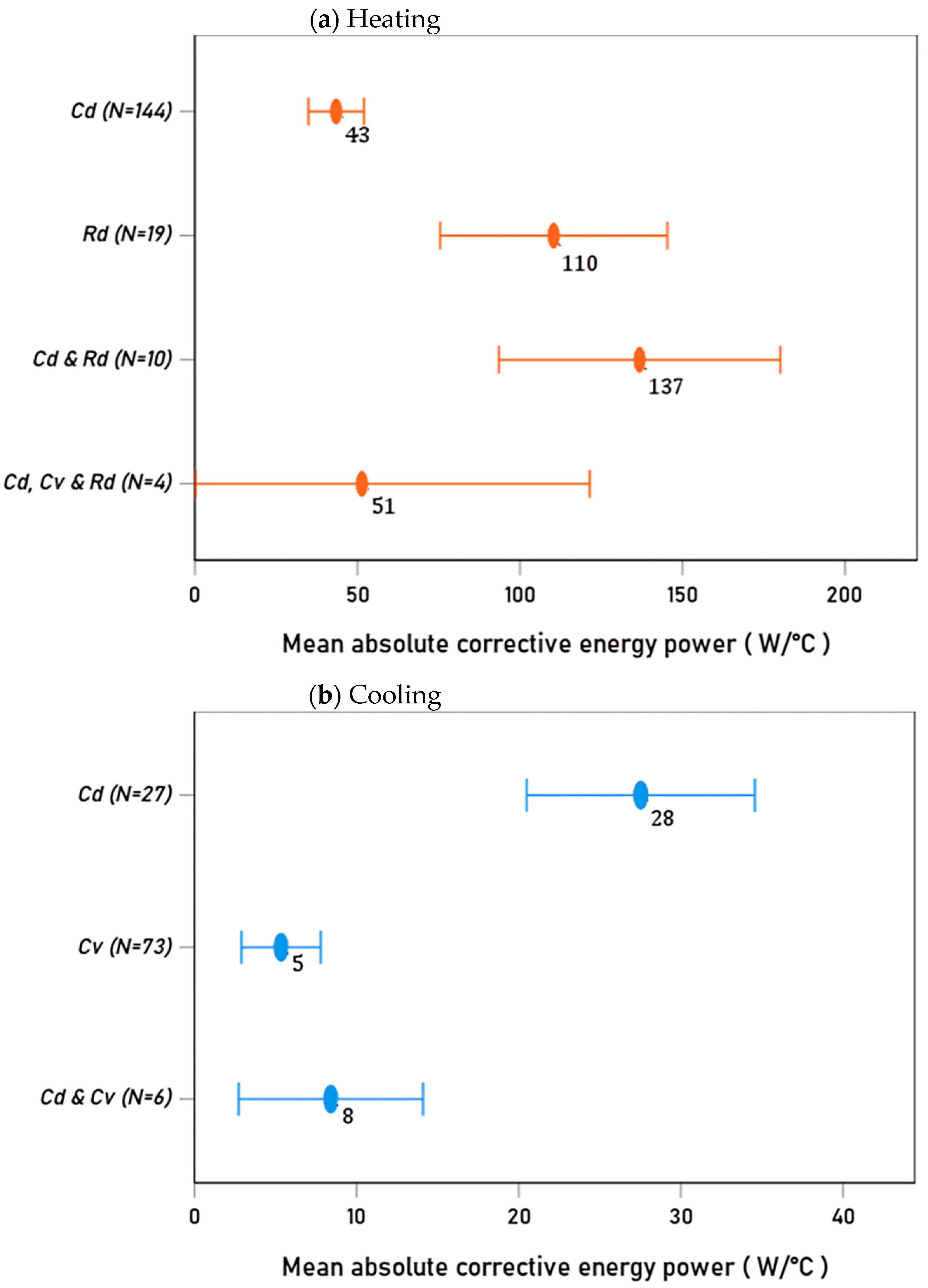

3.4. HTMs’ Impact on Corrective Powers of PCSs

3.5. HTMs’ Impact on Energy Performance

4. Overall Discussion and Future Work

5. Conclusions

- PCSs improve thermal sensations and overall comfort by approximately 1 scale unit in both heating and cooling modes. Hence, PCSs are effective in enhancing occupant comfort across both heating and cooling modes.

- The highest impactful individual heat transfer mechanism for both heating and cooling modes was Rd. Among the combined mechanisms, the highest impactful heat transfer mechanism was the Cd and Cv mechanism. The least effective individual heat transfer mechanism was Cv for heating and Cd for cooling. Combined mechanisms have performed constructively in the cooling mode, but the Cv and Rd mechanism has the lowest impact in the heating mode. Hybrid heat transfer mechanisms in PCSs should be applied judiciously, as the system’s effectiveness depends on selecting mode-specific mechanisms. For maximizing occupant comfort, radiative heat transfer is the most effective when used individually for both heating and cooling.

- Most of the PCSs consumed less energy (<200 W/°C) to improve thermal perception in both modes while most of the HTMs in the heating mode had higher CEP values compared to the cooling mode. Cd for heating and Cv for cooling are recommended as the most comfort-improving and energy-efficient HTMs.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Reference | Type | Targeted Body Parts | Mode | Heat Transfer Method | Number of Subjects | Power Values (W) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhai et al. [91] | Floor fan | Head/face/neck, arms/wrists/hands, torso | CL | Cv | 16 | 2.8, 3.3, 4.8, 5.7, 7.9, 10.3 |

| Huang et al. [92] | Frontal desk fan | Head/face/neck, arms/wrists/hands, torso | CL | Cv | 30 | - |

| Cui and Cao [93] | Fan simulated natural wind/constant mechanical wind | Head/face/neck, arms/wrists/hands, torso | CL | Cv | 18 | - |

| Arens et al. [94] | Opposing air jets | Head/face/neck | CL | Cv | 18 | - |

| Atthajariyakul and Lertsatittanakorn [95] | Desk fan | Head/face/neck | CL | Cv | 15 | - |

| Zhang and Zhao [96] | Local airflow | Head/face/neck | CL | Cv | 30 | - |

| Amai et al. [97] | Task conditioning system/personal environmental module/under-desk task unit/remote control unit/remote control unit + mesh four terminal devices | Head/face/neck, arms/wrists/hands, front/back torso | CL | Cv | 24 | - |

| Zhai et al. [98] | Ceiling fan | Head/face/neck, arms/wrists/hands, front/back torso | CL | Cv | 16 | - |

| Kubo et al. [99] | Uniform airflow on whole body | Front of whole body | CL | Cv | 4, 9, 8, 6 | - |

| Zhang et al. [15] | Foot warmer | Head/face/neck, L=legs/feet | HT | Rd | 12 | 11, 5 |

| Watanabe et al. [100] | Cooling chair | Back of torso, buttocks | CL | Cv | 7 | - |

| Brooks and Parsons [101] | Heated seat | Back of torso, buttocks | HT | Cd | 8 | - |

| Su et al. [12] | Convection and radiation combined terminal device: Fixed/User control | Head/face/neck, legs/feet, front torso | HT | Cv and Rd | 16 | - |

| Shahzad et al. [102] | Thermal chair | Back of torso, buttocks | HT | Cd | 44 | - |

| Du et al. [43] | Local warm air supplier: Supply air temperature 32, 42, 52, 28, 34, 40, 26, 30, 34, 22 °C | Legs/feet | HT | Cv | 20 | - |

| Zhu et al. [27] | Radiant panel (low/high)/heating plate/fan heater | Legs/feet | HT | Rd/Cd/Cv | 20 | 230, 170, 450, 230 |

| Song et al. [14] | Hybrid personal cooling garment | Front/back torso, buttocks | CL | Cd and Cv | 11 | - |

| Verhaart et al. [103] | Personalized air movement: 23, 26 °C supply temperature | Head/face/neck | CL | Cv | 12 | - |

| Kaczmarczyk et al. [104] | Personal ventilation supply temperature 21, 26 °C | Head/face/neck | CL | Cv | 32 | - |

| Li et al. [44] | Foot heating pad—constant heating 30 W, 90 W, high and low fluctuating frequency heating | Legs/feet | HT | Cd | 16 | 52, 56, 60 |

| Pasut et al. [65] | Ceiling fan: 2/3 oscillating/fixed front/side/below | Head/face/neck, arms/wrists/hands, front/back torso | CL | Cv | 16 | 2, 3 |

| Luo et al. [13] | Heating desk, heating mat and ventilation fans | Head/face/neck, arms/wrists/hands, front torso, legs/feet | HT | Cd and Cv | 18 | - |

| Tang et al. [81] | Warm air blower/radiant heater/heated cushion/desk/floor fan, ventilated cushion | Head/face/neck, arms/wrists/hands, front/back torso, legs/feet | HT/CL | Cv/Cd/Rd | 28 | 3.3, 10.1, 29.9, 43, 420, 630 |

| Lee et al. [105] | Ventilation seat/cold water seat/electric heating/hot water | Back of torso, buttocks | CL/HT | Cv | 20 | - |

| Pallubinsky et al. [106] | Face cooling/back cooling/foot sole cooling/face underarm cooling | Head/face/neck | CL | Cv | 16 | - |

| Veselý et al. [23] | Heated chair/desk mat/floor mat/combination: user controlled/fixed/automated | Arms/wrists/hands, back torso, buttocks, legs/feet | HT | Cd | 13 | 36, 80, 100, 216 |

| Udayraj et al. [107] | Radiant heating panel with table pad/heated chair with heated floor mattress/heated jacket and heated trousers/radiant heating panel with table pad | Arms/wrists/hands, front/back torso, buttocks, legs/feet | HT | Rd and Cd/Cd | 14 | 16, 133, 325 |

| Yang et al. [66] | Footwarmer normal shoes/sandals | Legs/feet | HT | Rd | 32 | 125 |

| Wang et al. [108] | Radiant/wrist/ankle/torso/combined heating | Face, torso, ankles, wrists/hands | HT | Rd/Cd | 20 | 450, 16, 20, 60, 36, 80, 76 |

| Song et al. [109] | Electrically heated/chemically ensemble | Torso and legs | HT | Cd | 8 | 15.9 |

| Tang et al. [110] | Cooling air towards the breathing zone/chest and back/combined | Face and torso | CL | Cv | 28 | - |

| Zhao et al. [111] | Ventilation cooling shirt | Torso | CL | Cv | 8 | - |

| He et al. [11] | Radiant cooling desk/local airflow: 1.6, 2.2 m/s/combined | Head/face/neck, arms/wrists/hands, front torso | CL | Rd/Cv/Rd and Cv (Cd *) | 20 | 2, 3 |

| Verhaart et al. [112] | Personalized air movement: Supply temperature 23, 25, 26 °C, | Head/face/neck | CL | Cv | 11 | - |

| Yu et al. [113] | Heated floor panel and insulated chair | Arms/wrists/hands, legs/feet | HT | Cd | 10 | 30 |

| Yang al. [74] | Table pad, backrest, cushion heaters, and leg warmer | Arms/wrists/hands, back torso, buttocks, legs/feet | HT | Cd and Rd | 8 | 145 |

| Kimmling and Hoffmann [67] | Thermoelectric cooling partition 50, 100% cooling power | Head, lower/upper body from side | CL | Rd | 7 | 60 |

| Sun et al. [114] | Displacement ventilation system | Whole body | CL | Cv | 32 | 23 |

| He et al. [115] | Desk fan 1.5, 2.3 m/s, user controlled | Head/face/neck | CL | Cv | 24 | 0.8, 1.5, 1.8, 2, 3 |

| Ren et al. [116] | Heating plates 1–4/2–4 | Legs/feet | HT | Rd | 20 | 156.5, 170.1, 208.4, 226.8 |

| Li et al. [63] | Under-floor air distribution 22.18 °C + personalized ventilation 26.22 °C: 5/10 L/s | Face and whole body | CL | Cv | 30 | - |

| Akimoto et al. [117] | Task ambient system | Whole body | CL | Cv | 20 | - |

| Schiavon et al. [45] | Stand fan | Face and upper body from side | CL | Cv | 56 | 4, 7.6 |

| He et al. [46] | Radiant cooling desk | Upper body, hand, wrist | CL | Rd (Cd *) | 20 | - |

| Wang et al. [108] | Local heating floor mat small/large—low/high power | Feet | HT | Cd | 16 | 60, 110 |

| Oi et al. [59] | Seat/foot warmer/combined | Back torso, buttocks, Legs/feet | HT | Cd | 8 | 10, 48, 58 |

| He et al. [24] | Retrofitted Huotong | Buttocks, legs, whole body | HT | Cd, Cv, and Rd | 16 | 49.4, 104.1, 140.3, 165.7 |

| Yang et al. [118] | Heated chair equipped with backrest and seat-heating cushions | Back torso and buttocks | HT | Cd | 13 | 90 |

| He et al. [60] | Heating chair/heating chair with leg warmer | Back torso, buttocks, legs | HT | Cd | 12 | 19.4, 25.3, 25.4, 34.1, 34.9, 41.1 |

| Pasut et al. [119] | Heated/cooled chair + cover/clothing/fan | Back torso, buttocks | HT/CL | Cd | 23 | 3.6, 16 |

| Zhang et al. [68] | Task/ambient conditioning (TAC) system | Face/head, legs/feet, hands/wrists/palms | HT/CL | Cd, Cd and Cv | 18 | 59,41, |

| Luo et al. [10] | Heating insoles/wrist pad/chair heating/combined/fan/chair cooling/combined | Feet/leg, buttocks, back torso, hand, wrists, face | HT/CL | Cd/Cv/Cv and Cd | 20 | 2.4, 7, 9.4, 16.4, 21, 23.4, 4.4, 5.6, 8 |

| Pasut et al. [120] | Thermoelectric chair | Back torso and buttocks | HT/CL | Cd | 30 | 42, 74 |

| Yang et al. [61] | Back, buttocks, combined cooling | Back torso and buttocks | CL | Cd | 16 | 54.5, 54.8, 66.2, 61.9, 64.6, 83.2, 72.5, 73.3, 97.7 |

| He et al. [121] | Desk fans/desk fans+ air conditioning | Face and upper body | CL | Cv | 16 | 0.7, 1.1, 1.2, 1.4, 1.9, 2.2, 2.4, 2.9 |

| Ke et al. [122] | Nanoporous polyethylene clothing | Front/back torso, arms | CL | Cd | 18 | - |

| H Yang et al. [123] | Chest/abdomen/upper back/lower back cooling | Front and back torso | CL | Cd | 20 | 45 |

| Udayraj et al. [64] | Ventilation clothing/desk fan | Torso cooling, forehead/hand cooling | CL | Cv | 14 | 5.2, 40 |

| Liu et al. [52] | Neck cooler, fan | Neck/face/head | CL | Cd, Cv | 14 | - |

| Wu et al. [124] | Fan | Head/face/hands | CL | Cv | 12 | 3 |

| Ilmiawan et al. [125] | Fan: Different directions | Face/head/upper body | CL | Cv | 20 | 15 |

| Wu et al. [126] | Heating pad with and without air condition | Front/back torso, feet | HT | Cd | 12 | 20.9 |

| Yang et al. [82] | Wristband, leg band, insole, warm air blower, radiant heater, combined heating | Wrist, legs, feet | HT | Cd | 26 | 4, 5, 10, 19 |

| Belyamani et al. [62] | Thermoelectric heat pump module | Upper back torso | CL | Cd | 60 | 8 |

| Heat Transfer Mechanism (HTM) | TSV | OC | CEP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heating | Cooling | Heating | Cooling | Heating | Cooling | |

| Cd | 156 | 40 | 149 | 39 | 144 | 27 |

| Cv | 16 | 192 | 13 | 151 | 2 | 73 |

| Rd | 22 | 8 | 15 | 8 | 19 | 2 |

| Cd and Cv | 4 | 9 | 4 | 9 | - | 6 |

| Cd and Rd | 10 | - | 10 | - | 10 | - |

| CV and Rd | 8 | 6 | 8 | 6 | - | - |

| Cd, Cv and Rd | 4 | - | - | - | 4 | - |

| Total | 220 | 255 | 199 | 213 | 179 | 108 |

References

- Tanaka, N. Technology roadmap energy-efficient buildings: Heating and cooling equipment. Int. Energy Agency 2011, 5, 6–8. [Google Scholar]

- Simulation-Based Control for Energy Efficiency Building Operation and Maintenance—European Commission. Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/608981/reporting/de (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Kim, J.; Bauman, F.; Raftery, P.; Arens, E.; Zhang, H.; Fierro, G.; Anderson, M.; Culler, D. Occupant comfort and behavior: High-resolution data from a 6-month field study of personal comfort systems with 37 real office workers. Build. Environ. 2019, 148, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Kramer, R.; De Kort, Y.; Van Marken Lichtenbelt, W. Effectiveness of personal comfort systems on whole-body thermal comfort—A systematic review on which body segments to target. Energy Build. 2022, 256, 111766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Personal Comfort Systems Study Collects Data to Better Predict Occupant Thermal Comfort|Ashrae.org. Available online: https://www.ashrae.org/news/ashraejournal/personal-comfort-systems-study-collects-data-to-better-predict-occupant-thermal-comfort (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Enescu, D. Heat transfer mechanisms and contributions of wearable thermoelectrics to personal thermal management. Energies 2024, 17, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Jiang, Q. Personal thermal management strategies to reduce energy consumption: Principles and applications of new materials with bionic structures. Energy Build. 2024, 324, 114887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawal, R.; Schweiker, M.; Kazanci, O.B.; Vardhan, V.; Jin, Q.; Duanmu, L. Personal comfort systems: A review on comfort, energy, and economics. Energy Build. 2020, 214, 109858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Wang, F.; Yang, B. Thermal comfort and energy performance of personal comfort systems (PCS): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Energy Build. 2022, 256, 111747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Arens, E.; Zhang, H.; Ghahramani, A.; Wang, Z. Thermal comfort evaluated for combinations of energy-efficient personal heating and cooling devices. Build. Environ. 2018, 143, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, N.; Wang, X.; He, M.; He, D. Comfort, energy efficiency and adoption of personal cooling systems in warm environments: A field experimental study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Yang, B.; Zhou, B.; Wang, F.; Li, A. A novel convection and radiation combined terminal device: Its impact on occupant thermal comfort and cognitive performance in winter indoor environments. Energy Build. 2021, 246, 111123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Kramer, R.; Kort, Y.; Rense, P.; Marken Lichtenbelt, W. The effects of a novel personal comfort system on thermal comfort, physiology and perceived indoor environmental quality, and its health implications—Stimulating human thermoregulation without compromising thermal comfort. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e12951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Wang, F.; Wei, F. Hybrid cooling clothing to improve thermal comfort of office workers in a hot indoor environment. Build. Environ. 2016, 100, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Arens, E.; Taub, M.; Dickerhoff, D.; Bauman, F.; Fountain, M.; Pasut, W.; Fannon, D.; Zhai, Y.; Pigman, M. Using footwarmers in offices for thermal comfort and energy savings. Energy Build. 2015, 104, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exss, K.; Wegertseder-Martínez, P.; Trebilcock, M. A systematic review of Personal Comfort Systems from a post-phenomenological view. Ergonomics 2025, 68, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, J.; Kim, J. Effect of different HVAC control strategies on thermal comfort and adaptive behavior in high-rise apartments. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, B.; Biju, A.; Vanshita Rastogi, A.; Dahiya, K.; Kala, S.M.; Hagishima, A. The challenge of multiple thermal comfort prediction models: Is TSV enough? Buildings 2023, 13, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Luo, A.; Lu, Y.; Zhen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Bian, G. Research on indoor thermal comfort of orthopedic patients in hospital. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). ASHRAE Handbook: Fundamentals; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.; Hu, X.; Sani, S.N.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Chai, L.; Li, D. Outdoor thermal comfort at a university campus: Studies from personal and long-term thermal history perspectives. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Hou, H.; Tsang, T.W.; Mui, K.W.; Wong, L.T. Predicting students’ thermal sensation votes in university libraries taking into account their mood states. Indoor Built Environ. 2024, 33, 859–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselý, M.; Molenaar, P.; Vos, M.; Li, R.; Zeiler, W. Personalized heating—Comparison of heaters and control modes. Build. Environ. 2017, 112, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, N.; Zhou, L.; Wang, K.; Zhang, W. Thermal comfort and energy consumption in cold environment with retrofitted Huotong (warm-barrel). Build. Environ. 2017, 112, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Arens, E.; Zhai, Y. A review of the corrective power of personal comfort systems in non-neutral ambient environments. Build. Environ. 2015, 91, 15–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Wang, M.; Feng, S.; Peng, Z.; Huang, X.; Song, Y. Study on the coupled heat transfer of conduction, convection, and radiation in foam concrete based on a microstructure numerical model. Buildings 2024, 14, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, H.; He, M.; Wu, Y.; Xiong, F.; Li, B. Comparing the improvement of occupant thermal comfort with local heating devices in cold environments. Build. Environ. 2025, 268, 112350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, H.; Schiavon, S.; Lian, Z.; Parkinson, T.; Lo, J.C. The effects of personal comfort systems on sleep: A systematic review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 213, 115474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Ghahramani, A. Evaluating personal comfort systems performance—A design of experiments based review. Build. Environ. 2025, 283, 113415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Aloe, A.M. Evaluation of various estimators for standardized mean difference in meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2021, 40, 403–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfo, P.; Okyere, G.A. The accuracy of effect-size estimates under normals and contaminated normals in meta-analysis. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xie, K. Mature but nascent—A scoping review for wearable thermoregulating devices. Energy Build. 2024, 318, 114438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warthmann, A.; Wölki, D.; Metzmacher, H.; Van Treeck, C. Personal climatization systems—A review on existing and upcoming concepts. Appl. Sci. 2018, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, S.; Calautit, J.K.; Calautit, K.; Hughes, B.; Aquino, A.I. Advanced personal comfort system (APCS) for the workplace: A review and case study. Energy Build. 2018, 173, 689–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Yildirim, I. A Tutorial on how to conduct meta-analysis with IBM SPSS Statistics. Psych 2022, 4, 640–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LabPlot—Scientific Plotting and Data Analysis. Available online: https://labplot.org/ (accessed on 30 April 2025).

- Yang, W.; Moon, H.J.; Jeon, J.Y. Comparison of response scales as measures of indoor environmental perception in combined thermal and acoustic conditions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiker, M.; Fuchs, X.; Becker, S.; Shukuya, M.; Dovjak, M.; Hawighorst, M.; Kolarik, J. Challenging the assumptions for thermal sensation scales. Build. Res. Inf. 2017, 45, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantavou, K.; Koletsis, I.; Lykoudis, S.; Melas, E.; Nikolopoulou, M.; Tsiros, I.X. Native influences on the construction of thermal sensation scales. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 64, 1497–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Humphreys, M.A.; Nicol, J.F.; Raja, I.A. Field studies of indoor thermal comfort and the progress of the adaptive approach. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2007, 1, 55–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, M.; Nicol, F.; Roaf, S. Adaptive Thermal Comfort: Foundations and Analysis, 1st ed.; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, R. Overall thermal sensation, acceptability and comfort. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Liu, H.; Li, C.; Xiong, J.; Li, B.; Li, G.; Xi, Z. Demand and efficiency evaluations of local convective heating to human feet and low body parts in cold environments. Build. Environ. 2020, 171, 106662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Kosonen, R.; Li, B. Effects of constant and fluctuating temperature modes of foot heating on human thermal responses in cold environments. Build. Environ. 2023, 238, 110364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavon, S.; Yang, B.; Donner, Y.; Chang, V.W.C.; Nazaroff, W.W. Thermal comfort, perceived air quality, and cognitive performance when personally controlled air movement is used by tropically acclimatized persons. Indoor Air 2017, 27, 690–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, N.; He, M.; He, D. Using radiant cooling desk for maintaining comfort in hot environment. Energy Build. 2017, 145, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L.V. Distribution theory for glassf s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J. Educ. Stat. 1981, 6, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melsen, W.G.; Bootsma, M.C.J.; Rovers, M.M.; Bonten, M.J.M. The effects of clinical and statistical heterogeneity on the predictive values of results from meta-analyses. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buck, R.J.; Fieberg, J.; Larkin, D.J. The use of weighted averages of Hedges’ d in meta-analysis: Is it worth it? Methods Ecol. Evol. 2022, 13, 1093–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedges, L.V.; Olkin, I. Statistical Methods for Meta-Analysis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Xin, J.; Liu, Z.; Zeng, W.; Li, Q.; Jin, L.; You, R.; Liu, M.; Liu, H. Are wearable local cooling devices effective in Chinese residential kitchens during hot summer? Build. Environ. 2024, 257, 111532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Warren, K.; Luo, M.; He, X.; Zhang, H.; Arens, E.; Chen, W.; He, Y.; Hu, Y.; Jin, L.; et al. Evaluating the comfort of thermally dynamic wearable devices. Build. Environ. 2020, 167, 106443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanger, P.O. Thermal Comfort: Analysis and Applications in Environmental Engineering; Danish Technical Press: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1970; 244p. [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, R.F.; Parkinson, T.; Kim, J.; Toftum, J.; De Dear, R. The impact of occupant’s thermal sensitivity on adaptive thermal comfort model. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, R.F.; Kim, J.; Ghisi, E.; de Dear, R. Thermal sensitivity of occupants in different building typologies: The Griffiths constant is a variable. Energy Build. 2019, 200, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Xuan, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, W. The thermal sensitivity (Griffiths constant) of occupants for naturally ventilated buildings in China. Energy Build. 2025, 341, 115786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartarini, F.; Schiavon, S.; Cheung, T.; Hoyt, T. CBE Thermal comfort tool: Online tool for thermal comfort calculations and visualizations. SoftwareX 2020, 12, 100563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oi, H.; Yanagi, K.; Tabata, K.; Tochihara, Y. Effects of heated seat and foot heater on thermal comfort and heater energy consumption in vehicle. Ergonomics 2011, 54, 690–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, N.; He, M.; He, D. Heating chair assisted by leg-warmer: A potential way to achieve better thermal comfort and greater energy conservation in winter. Energy Build. 2018, 158, 1106–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Deng, Y.; Cao, B.; Zhu, Y. Study on the local and overall thermal perceptions under nonuniform thermal exposure using a cooling chair. Build. Environ. 2020, 176, 106864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyamani, M.A.; Hurley, R.F.; Djamasbi, S.; Somasse, G.B.; Strauss, S.; Zhang, H.; Smith, M.J.; Dessel, S.V.; Liu, S. Local wearable cooling may improve thermal comfort, emotion, and cognition. Build. Environ. 2024, 254, 111367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Sekhar, S.C.; Melikov, A.K. Thermal comfort and IAQ assessment of under-floor air distribution system integrated with personalized ventilation in hot and humid climate. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 1906–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayraj Li, Z.; Ke, Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, B. Personal cooling strategies to improve thermal comfort in warm indoor environments: Comparison of a conventional desk fan and air ventilation clothing. Energy Build. 2018, 174, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasut, W.; Arens, E.; Zhang, H.; Zhai, Y. Enabling energy-efficient approaches to thermal comfort using room air motion. Build. Environ. 2014, 79, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Li, Z.; Zhou, B.; Olofsson, T.; Li, A. Enhanced effects of footwarmer by wearing sandals in winter office: A Swedish case study. Indoor Built Environ. 2021, 30, 875–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmling, M.; Hoffmann, S. Preliminary study of thermal comfort in buildings with PV-powered thermoelectric surfaces for radiative cooling. Energy Procedia 2017, 121, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Arens, E.; Kim, D.; Buchberger, E.; Bauman, F.; Huizenga, C. Comfort, perceived air quality, and work performance in a low-power task–ambient conditioning system. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqilah, N.; Rijal, H.B.; Zaki, S.A. A Review of thermal comfort in residential buildings: Comfort threads and energy saving potential. Energies 2022, 15, 9012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peddie, K.M.; Soligo, M.J. Holistic approach to human comfort. Aust. J. Multi Discip. Eng. 2020, 16, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Z. Revisiting thermal comfort and thermal sensation. Build. Simul. 2024, 17, 185–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyt, T.; Arens, E.; Zhang, H. Extending air temperature setpoints: Simulated energy savings and design considerations for new and retrofit buildings. Build. Environ. 2015, 88, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, J. Study on personal comfort heating system and human thermal comfort in extremely low-temperature building environments. Build. Environ. 2024, 259, 111640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wu, M.; Li, Z.; Yao, H.; Wang, F. Thermal comfort and energy savings of personal comfort systems in low temperature office: A field study. Energy Build. 2022, 270, 112276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Qin, M. Field study of meeting thermal needs of occupants in old residential buildings in low-temperature environments using personalized local heating. Build. Environ. 2024, 247, 111004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Qin, Z.; Mu, T.; Ge, Z.; Dong, Y. Evaluating thermal comfort indices for outdoor spaces on a university campus. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, X.; Lei, S.; Luo, M. Energy and comfort performance of occupant-centric air conditioning strategy in office buildings with personal comfort devices. Build. Simul. 2022, 15, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugani, R.; Bernagozzi, M.; Picco, M.; Salvadori, G.; Marengo, M.; Zhang, H.; Fantozzi, F. Thermal comfort and energy efficiency evaluation of a novel conductive-radiative personal comfort system. Build. Environ. 2023, 244, 110787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuhiko, K.; Akinobu, M.; Kimiko, Y.; Kazuhiko, S.; Weisheng, Z. Study on electricity consumption for domestic refrigerators, air conditioners, and water dispenser in Guangzhou (China) urban area based on questionnaire data. J. Jpn. Inst. Energy 2011, 90, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, A.; Hoang, T.N.; Tasaki, T. Household survey on air conditioner use and energy consumption in Vietnam. Glob. Environ. Res. 2021, 25, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, K.; Niu, K.; Mao, H.; Luo, M. Thermal comfort performance and energy-efficiency evaluation of six personal heating/cooling devices. Build. Environ. 2022, 217, 109069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, N.; Zhang, R.; Zhou, H.; Ding, L.; Tao, J.; Zhang, N.; Cao, B. Study on the effect of local Heating devices on human thermal comfort in low-temperature built environment. Buildings 2024, 14, 3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Niu, J.; Gao, N. Thermal comfort models: A review and numerical investigation. Build. Environ. 2012, 47, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Jia, X.; Peng, C.; Zhu, Y.; Cao, B. Thermal comfort benefits, energy efficiency, and occupant regulation behaviour in four types of personal heating within the built environment. Build. Environ. 2024, 266, 112075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, Z.; Lin, B.; Shi, W.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, H. Comparison of thermal comfort between convective heating and radiant heating terminals in a winter thermal environment: A field and experimental study. Energy Build. 2020, 224, 110239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, T.; Rijal, H.B.; Takaguchi, H. (Eds.) Sustainable Houses and Living in the Hot-Humid Climates of Asia; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rijal, H.B.; Humphreys, M.A.; Nicol, J.F. Adaptive model and the adaptive mechanisms for thermal comfort in Japanese dwellings. Energy Build. 2019, 202, 109371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draganova, V.; Tsuzuki, K.; Nabeshima, Y. Field study on nationality differences in thermal comfort of university students in dormitories during winter in Japan. Buildings 2019, 9, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havenith, G.; Griggs, K.; Qiu, Y.; Dorman, L.; Kulasekaran, V.; Hodder, S. Higher comfort temperature preferences for anthropometrically matched Chinese and Japanese versus white-western-middle-European individuals using a personal comfort/cooling system. Build. Environ. 2020, 183, 107162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, H.; He, Y.; Luo, M.; Li, Z.; Hong, T.; Lin, B. Revisiting individual and group differences in thermal comfort based on ASHRAE database. Energy Build. 2020, 219, 110017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Pasut, W.; Arens, E.; Meng, Q. Comfort under personally controlled air movement in warm and humid environments. Build. Environ. 2013, 65, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Ouyang, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, L. A study about the demand for air movement in warm environment. Build. Environ. 2013, 61, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, W.; Cao, G.; Ouyang, Q.; Zhu, Y. Influence of dynamic environment with different airflows on human performance. Build. Environ. 2013, 62, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens, E.; Zhang, H.; Pasut, W.; Warneke, A.; Bauman, F. Thermal Comfort and Perceived Air Quality of a PEC System; Proceedings of Indoor Air: Austin, TX, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Atthajariyakul, S.; Lertsatittanakorn, C. Small fan assisted air conditioner for thermal comfort and energy saving in Thailand. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 2499–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, R. Relationship between thermal sensation and comfort in non-uniform and dynamic environments. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1386–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amai, H.; Tanabe Sichi Akimoto, T.; Genma, T. Thermal sensation and comfort with different task conditioning systems. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 3955–3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Pasut, W.; Arens, E.; Meng, Q. Human comfort and perceived air quality in warm and humid environments with ceiling fans. Build. Environ. 2015, 90, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubo, H.; Isoda, N.; Enomoto-Koshimizu, H. Cooling effects of preferred air velocity in muggy conditions. Build. Environ. 1997, 32, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, S.; Shimomura, T.; Miyazaki, H. Thermal evaluation of a chair with fans as an individually controlled system. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1392–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.E.; Parsons, K.C. An ergonomics investigation into human thermal comfort using an automobile seat heated with encapsulated carbonized fabric (ECF). Ergonomics 1999, 42, 661–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, S.; Calautit, J.K.; Aquino, A.I.; Nasir, D.S.; Hughes, B.R. Neutral thermal sensation or dynamic thermal comfort? Numerical and field test analysis of a thermal chair. Energy Procedia 2017, 142, 2189–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaart, J.; Quaas, L.; Li, R.; Zeiler, W. Comfort of cooling by personal air movement. 14th International Conference on Indoor Air Quality and Climate. Indoor Air 2016, 2016, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarczyk, J.; Melikov, A.; Sliva, D. Effect of warm air supplied facially on occupants’ comfort. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 848–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Shin, Y.; Lee, H.; Cho, H. Investigation of bio-signal changes of occupants resting in buildings using local cooling and heating seats. Energy Build. 2021, 245, 111092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallubinsky, H.; Schellen, L.; Rieswijk, T.A.; Breukel, C.M.G.A.M.; Kingma, B.R.M.; Van Marken Lichtenbelt, W.D. Local cooling in a warm environment. Energy Build. 2016, 113, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udayraj Li, Z.; Ke, Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, B. A study of thermal comfort enhancement using three energy-efficient personalized heating strategies at two low indoor temperatures. Build. Environ. 2018, 143, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, M.; Bian, C. Experimental comparison of local direct heating to improve thermal comfort of workers. Build. Environ. 2020, 177, 106884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Wang, F.; Zhang, C.; Lai, D. On the improvement of thermal comfort of university students by using electrically and chemically heated clothing in a cold classroom environment. Build. Environ. 2015, 94, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Liu, Y.; Du, H.; Lan, L.; Sun, Y.; Wu, J. The effects of portable cooling systems on thermal comfort and work performance in a hot environment. Build. Simul. 2021, 14, 1667–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Kuklane, K.; Lundgren, K.; Gao, C.; Wang, F. A ventilation cooling shirt worn during office work in a hot climate: Cool or not? Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2015, 21, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhaart, J.; Li, R.; Zeiler, W. User interaction patterns of a personal cooling system: A measurement study. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 2018, 24, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Gu, Z.; Yan, Z.; Chen, H. Investigation and comparison on thermal comfort and energy consumption of four personalized seat heating systems based on heated floor panels. Indoor Built. Environ. 2021, 30, 1252–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Cheong, K.W.D.; Melikov, A.K. Subjective study of thermal acceptability of novel enhanced displacement ventilation system and implication of occupants’ personal control. Build. Environ. 2012, 57, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Li, N.; He, Y.; He, D.; Song, C. The influence of personally controlled desk fan on comfort and energy consumption in hot and humid environments. Build. Environ. 2017, 123, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Gao, X.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Y. Thermal comfort and energy conservation of a four-sided enclosed local heating device in a cold environment. Build. Environ. 2023, 228, 109837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, T.; Tanabe Sichi Yanai, T.; Sasaki, M. Thermal comfort and productivity—Evaluation of workplace environment in a task conditioned office. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Cao, B.; Zhu, Y. Study on the effects of chair heating in cold indoor environments from the perspective of local thermal sensation. Energy Build. 2018, 180, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasut, W.; Zhang, H.; Arens, E.; Zhai, Y. Energy-efficient comfort with a heated/cooled chair: Results from human subject tests. Build. Environ. 2015, 84, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasut, W.; Zhang, H.; Arens, E.; Kaam, S.; Zhai, Y. Effect of a heated and cooled office chair on thermal comfort. HVACR Res. 2013, 19, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, N.; Li, N.; Li, J.; Yan, J.; Tan, C. Control behaviors and thermal comfort in a shared room with desk fans and adjustable thermostat. Build. Environ. 2018, 136, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, F.; Xu, P.; Yang, B. On the use of a novel nanoporous polyethylene (nanoPE) passive cooling material for personal thermal comfort management under uniform indoor environments. Build. Environ. 2018, 145, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Cao, B.; Ju, Y.; Zhu, Y. The effects of local cooling at different torso parts in improving body thermal comfort in hot indoor environments. Energy Build. 2019, 198, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Fan, J.; Cao, B. Comparison among different modeling approaches for personalized thermal comfort prediction when using personal comfort systems. Energy Build. 2023, 285, 112873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilmiawan, F.A.; Zaki, S.A.; Singh, M.K.; Khalid, W. Effect of preferable wind directions on personal thermal comfort of occupants in the air-conditioned office in hot-humid climate. Build. Environ. 2024, 254, 111390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Zhao, J.; Su, Y. Influencing assessment of different heating modes on thermal comfort in electric vehicle cabin. Energy Built Environ. 2024, 5, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Value | Thermal Sensation Vote (TSV) | Overall Comfort (OC) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | Hot | Very comfortable |

| 2 | Warm | Comfortable |

| 1 | Slightly warm | Slightly comfortable |

| 0 | Neutral | Neutral |

| −1 | Slightly cool | Slightly uncomfortable |

| −2 | Cool | Uncomfortable |

| −3 | Cold | Very uncomfortable |

| Heat Transfer Mechanism | Heating | Cooling | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Cases | Pearson Correlation | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Number of Cases | Pearson Correlation | Sig. (2-Tailed) | |

| Cd | 156 | 0.64 | <0.001 | 40 | 0.67 | <0.001 |

| Cv | 16 | 0.51 | 0.011 | 192 | 0.48 | <0.001 |

| Rd | 22 | 0.48 | 0.033 | 8 | 0.74 | 0.037 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arachchi Appuhamilage, P.D.T.; Rijal, H.B. Effective Heat Transfer Mechanisms of Personal Comfort Systems for Thermal Comfort and Energy Savings: A Review. Energies 2025, 18, 5226. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18195226

Arachchi Appuhamilage PDT, Rijal HB. Effective Heat Transfer Mechanisms of Personal Comfort Systems for Thermal Comfort and Energy Savings: A Review. Energies. 2025; 18(19):5226. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18195226

Chicago/Turabian StyleArachchi Appuhamilage, Prabhath Dhammika Tharindu, and Hom B. Rijal. 2025. "Effective Heat Transfer Mechanisms of Personal Comfort Systems for Thermal Comfort and Energy Savings: A Review" Energies 18, no. 19: 5226. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18195226

APA StyleArachchi Appuhamilage, P. D. T., & Rijal, H. B. (2025). Effective Heat Transfer Mechanisms of Personal Comfort Systems for Thermal Comfort and Energy Savings: A Review. Energies, 18(19), 5226. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18195226