Energy Transition in Greece: A Regional and National Media Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

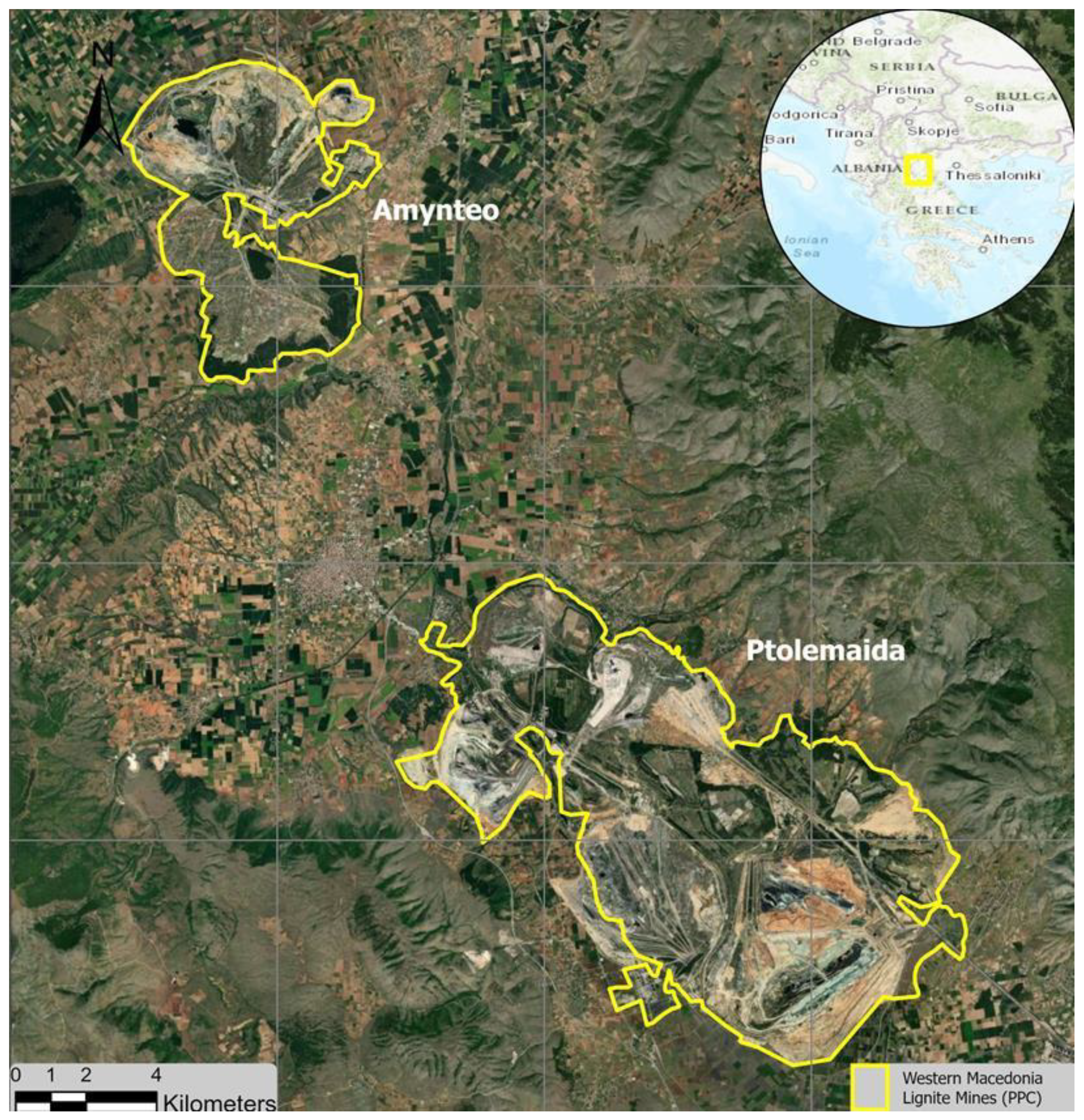

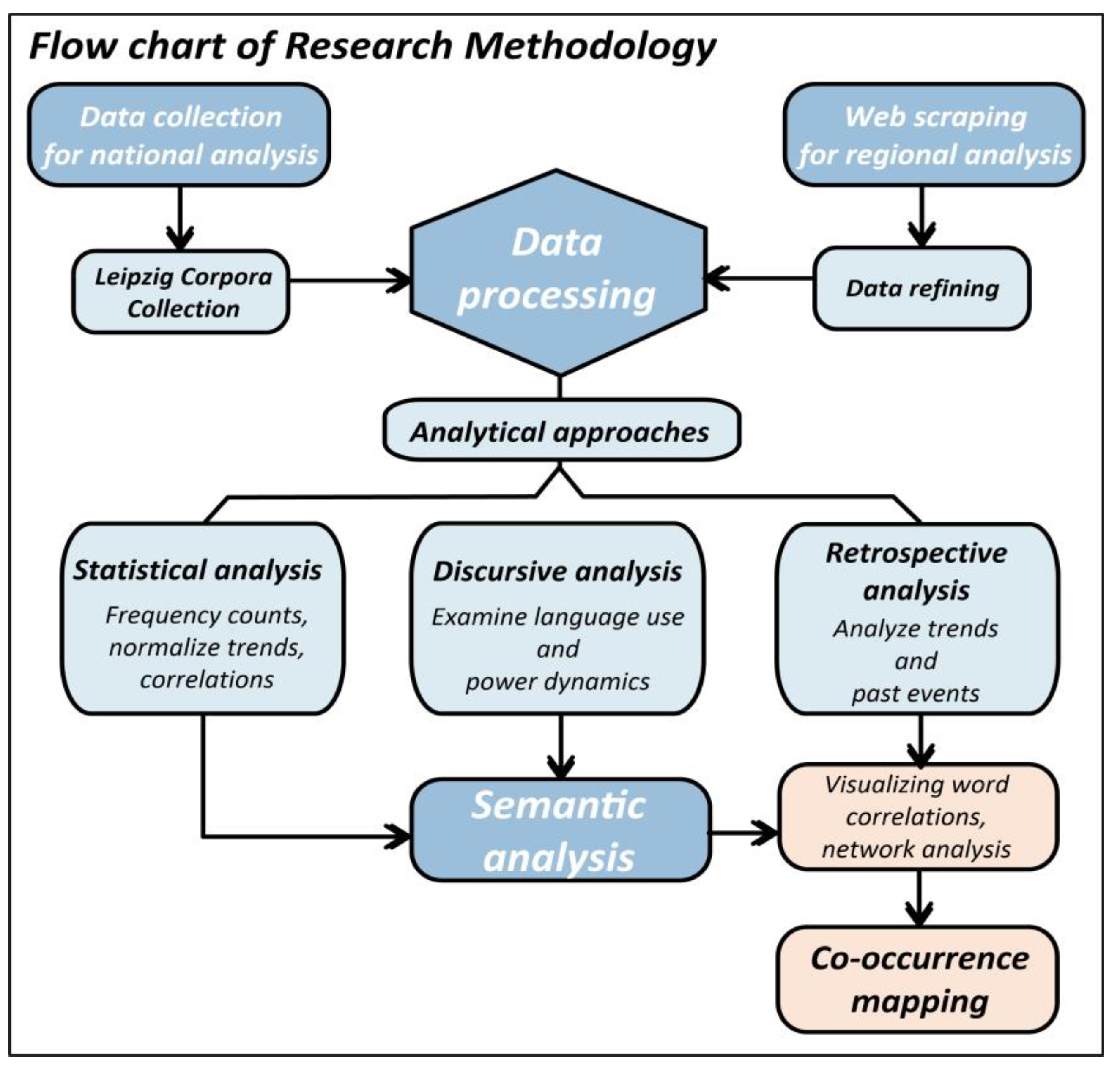

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Framework

2.2. Media Landscape and Theoretical Basis

2.3. Data Source for National Media Analysis: Leipzig Corpora Collection

2.4. Web Scraping of Regional Greek News Sources and Definition of Media Attributes

3. Results

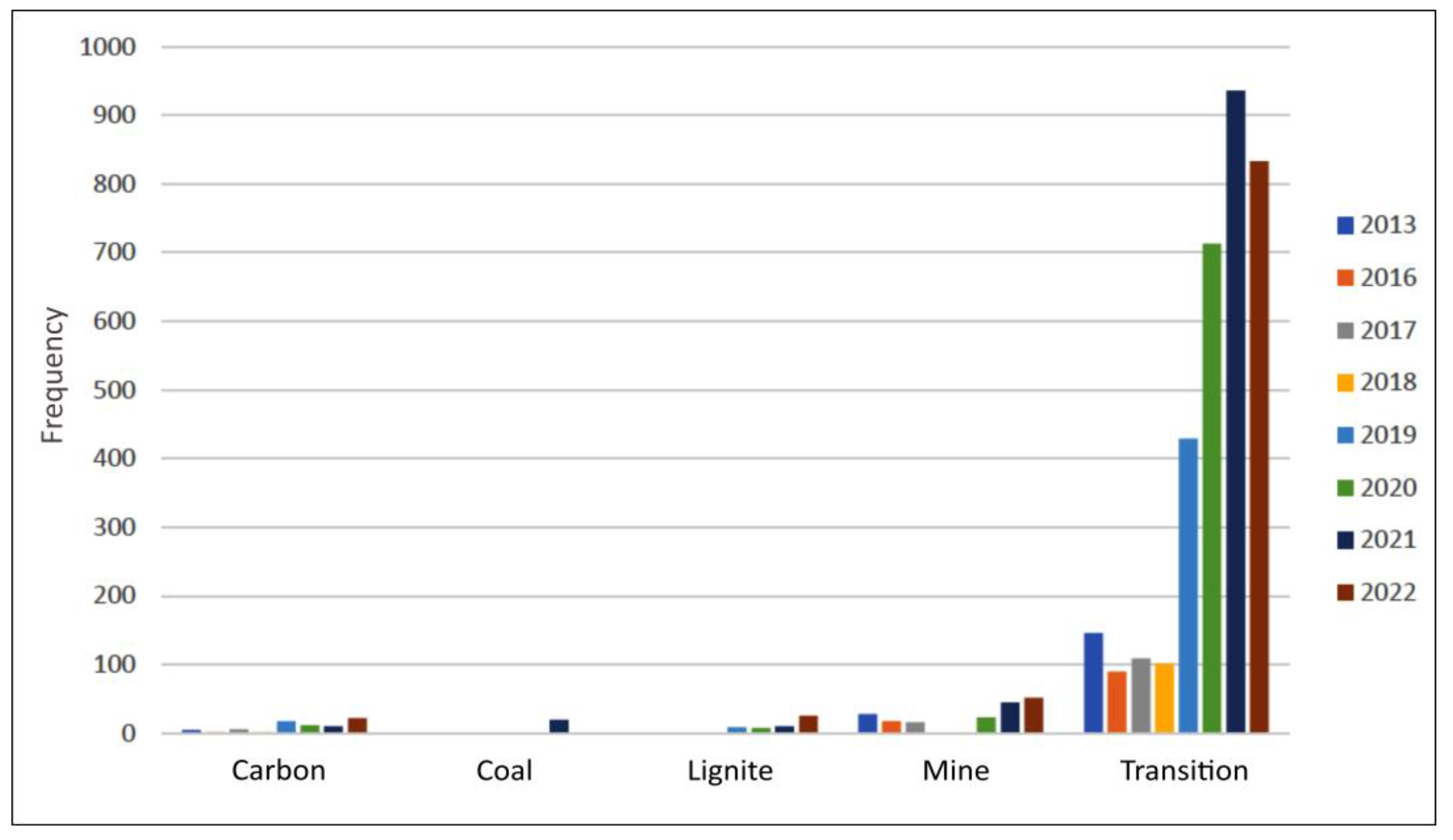

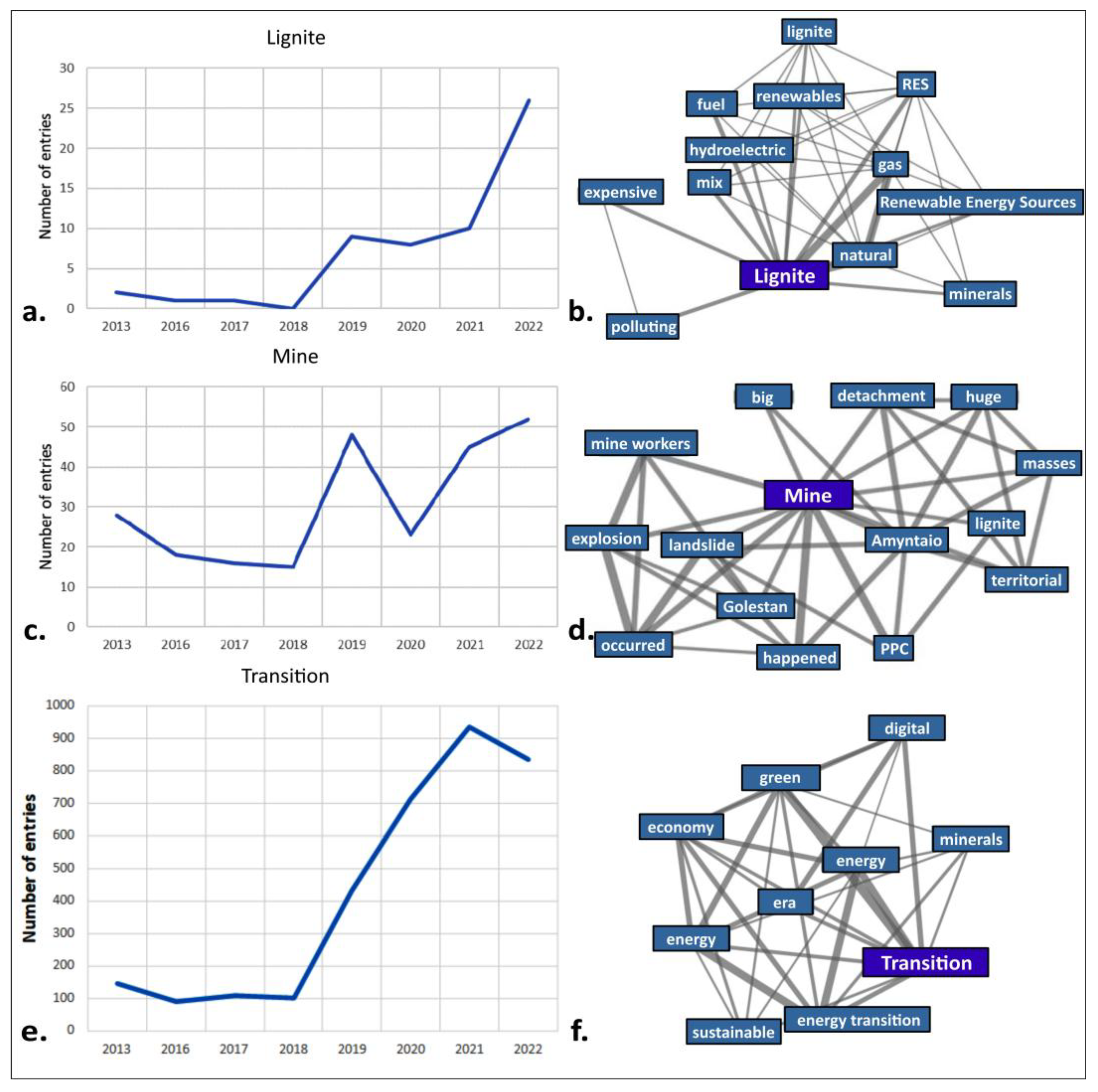

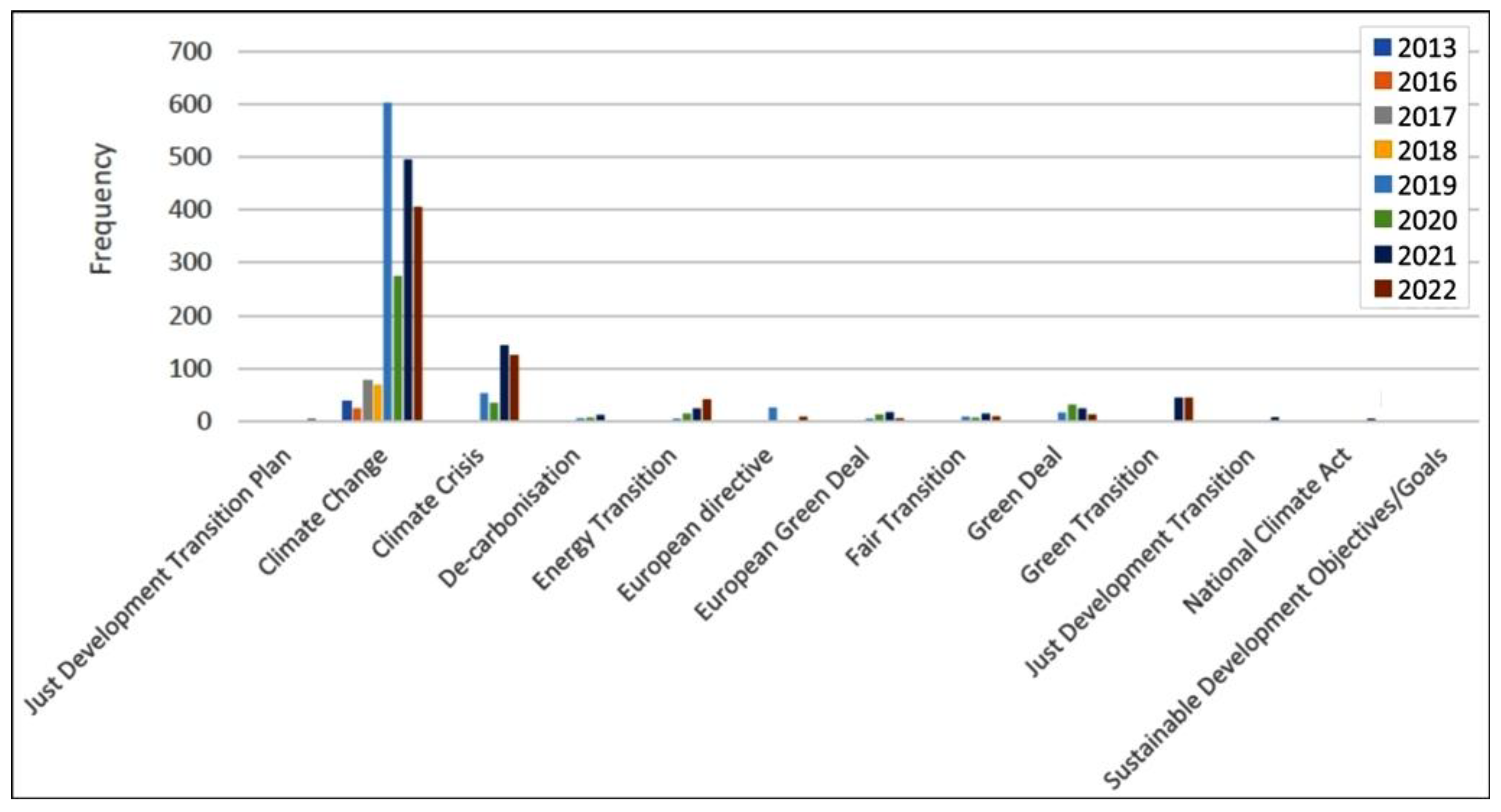

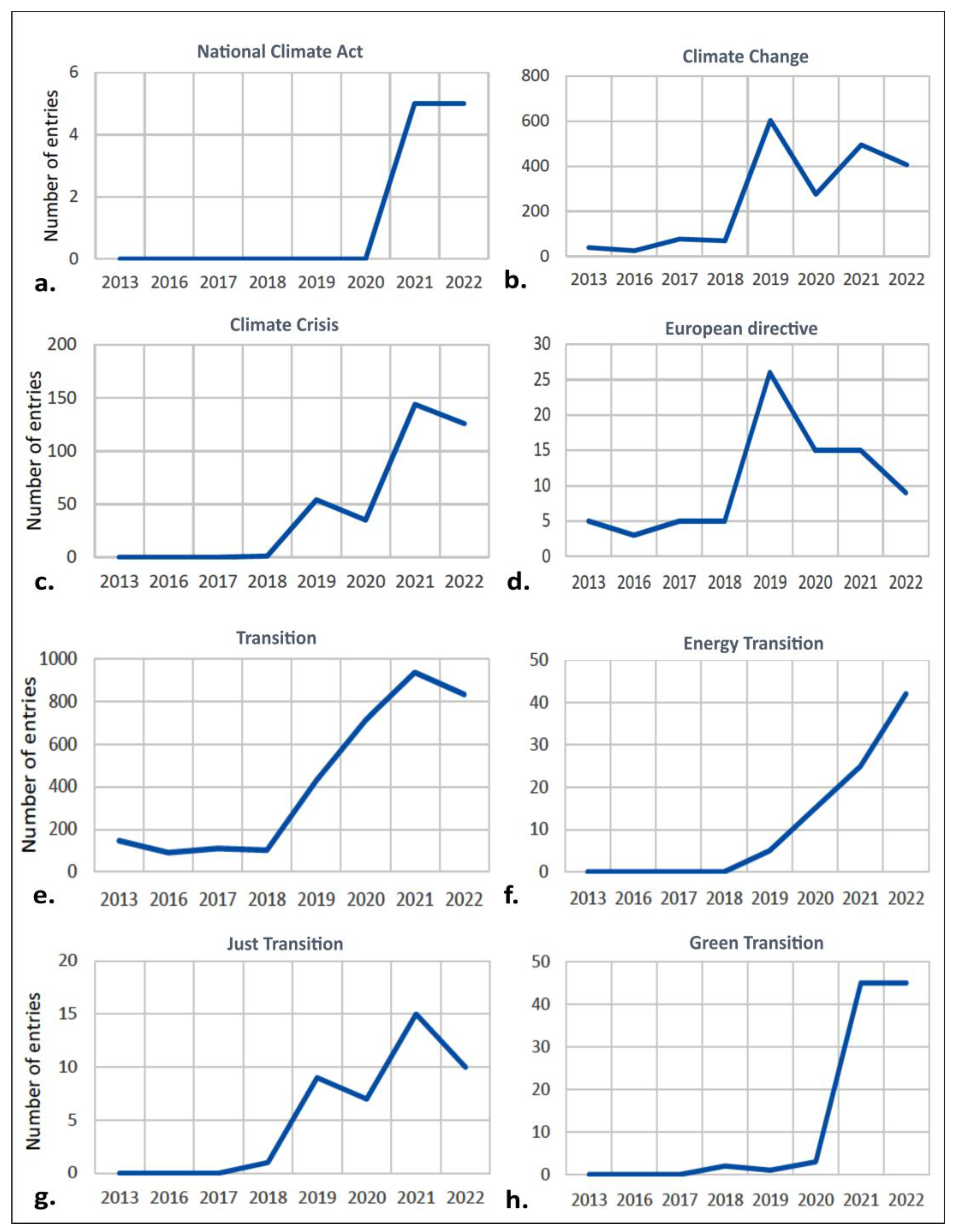

3.1. National Level Media Analysis

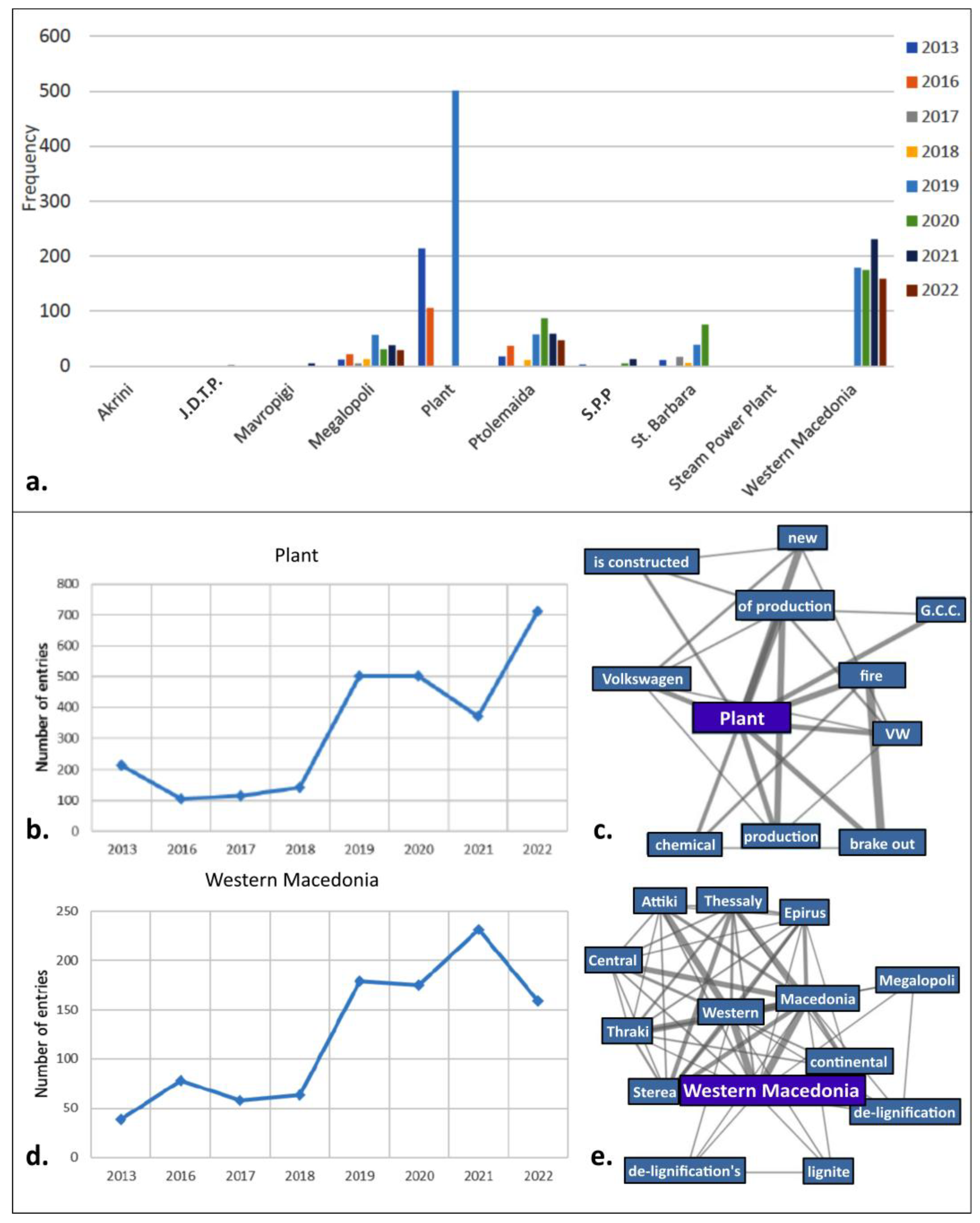

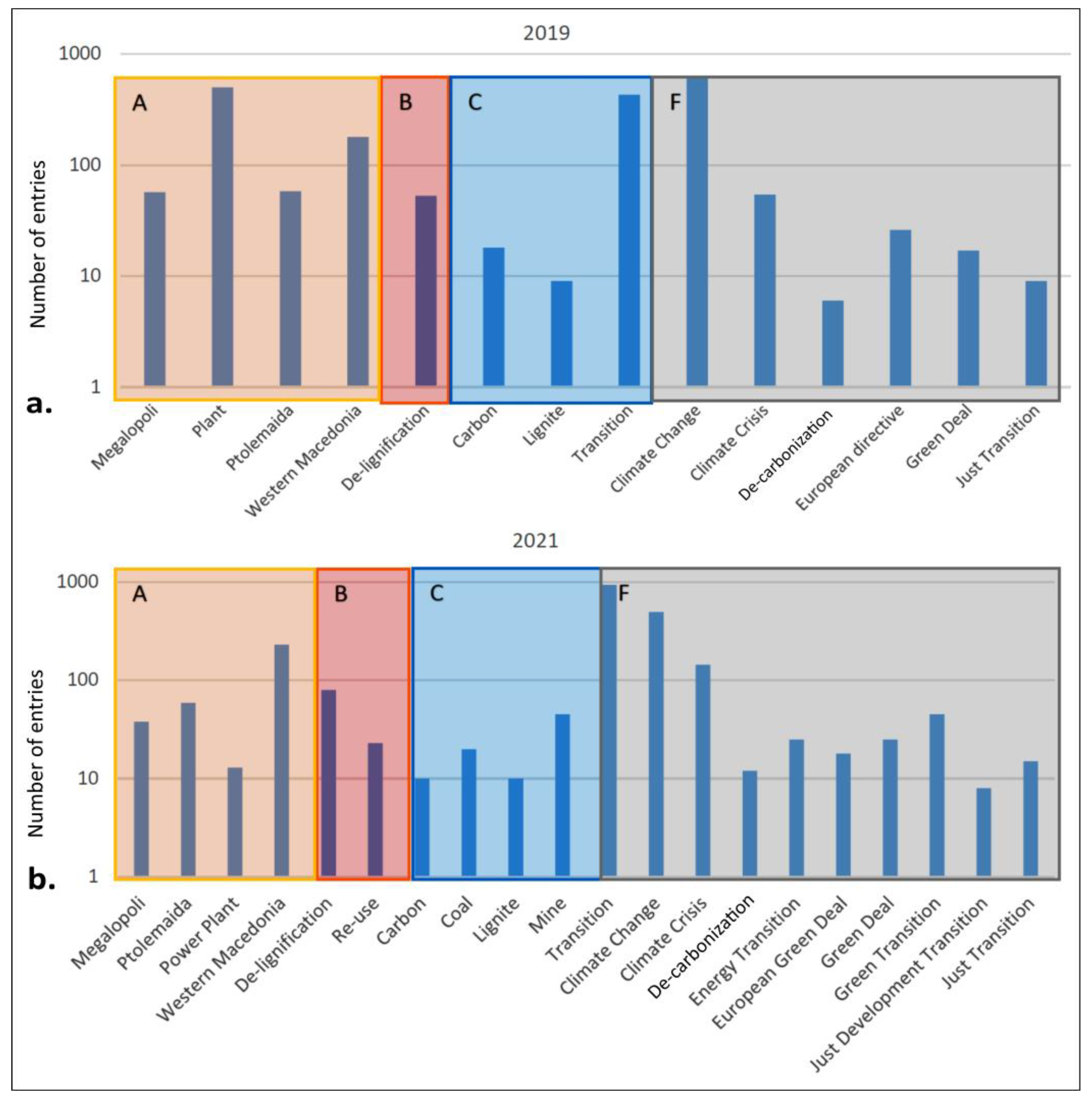

3.1.1. Solidarity/Identity (Category A)

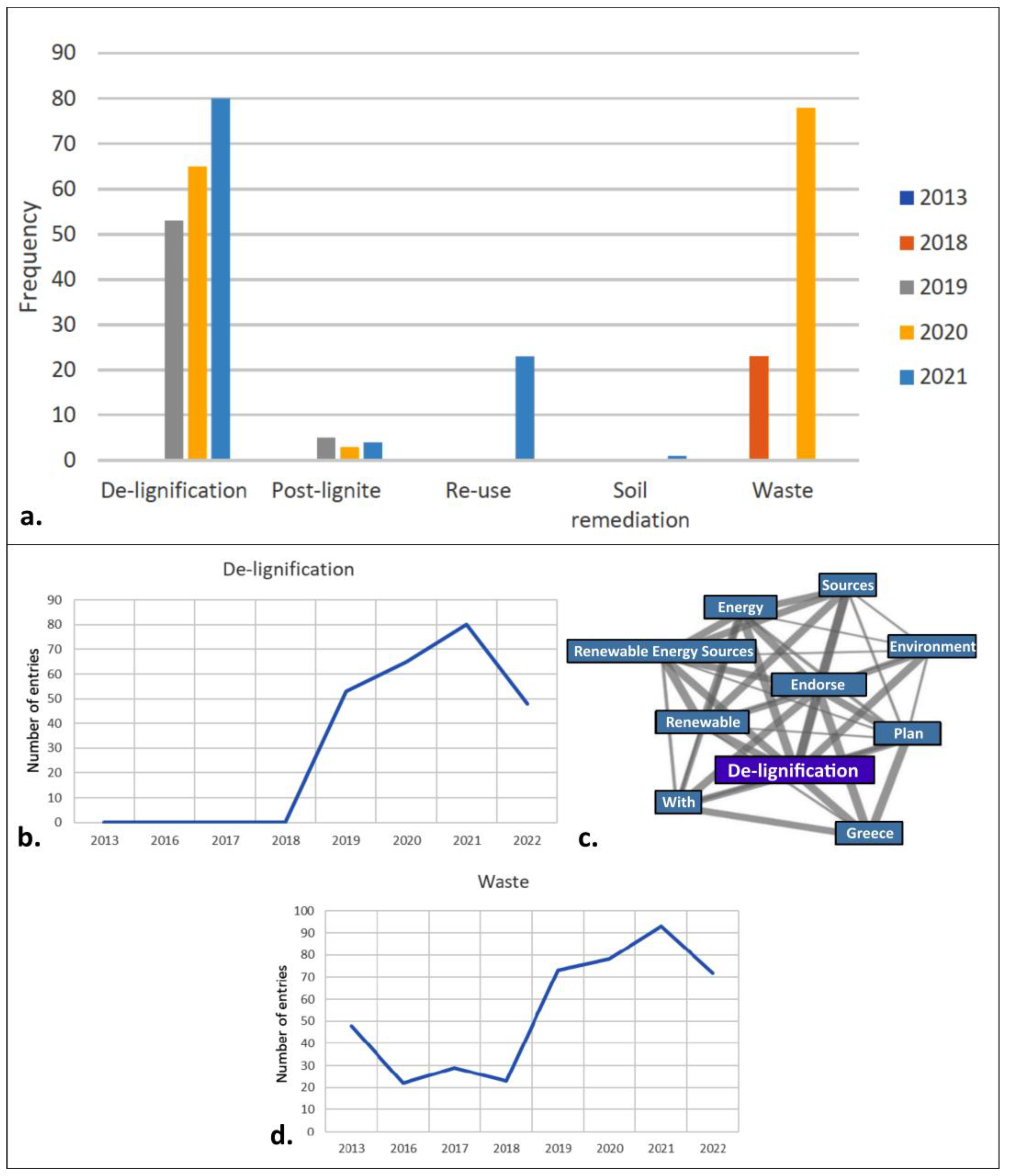

3.1.2. Site Development (Category B)

3.1.3. Regional Development (Category C)

3.1.4. Technical Tasks (Category D)

3.1.5. Landscape Zone (Category E)

3.1.6. Perception EU (Category F)

3.2. Regional Level Media Analysis

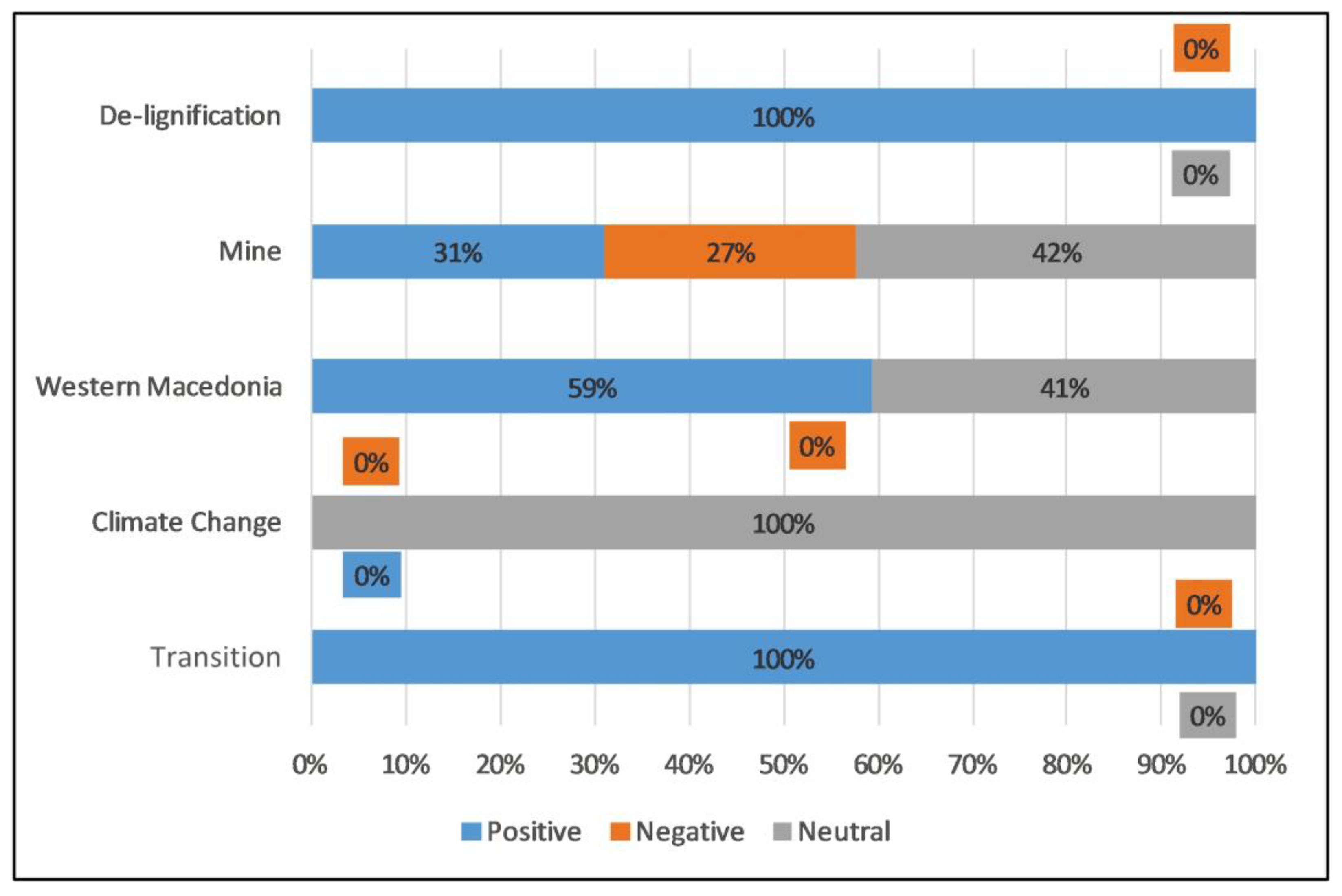

3.2.1. Solidarity/Identity (Category A)

3.2.2. Site Development (Category B)

3.2.3. Regional Development (Category C)

3.2.4. Technical Tasks (Category D)

3.2.5. Landscape Zone (Category E)

3.2.6. Perception EU (Category F)

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Analysis: National vs. Regional Media

4.2. Framing the Transition: Political Narratives and Community Perception

5. Conclusions

- National and regional media outlets frame the energy transition from distinct perspectives: national media emphasize policy, investment, and EU alignment, whereas regional outlets provide more immediate, community-centric viewpoints focused on local livelihoods and direct socio-economic impacts.

- A temporal divergence is evident, with regional media often addressing transition-related issues such as “post-lignite” earlier and with greater frequency than national outlets, reflecting the urgency felt in lignite-dependent areas.

- Narrative tensions emerge between the top-down, optimistic framing of the transition in national coverage and the more apprehensive regional discourse that highlights concerns over employment security and cultural heritage.

- Since 2018, the evolution of Greek energy policy, punctuated by milestones such as the Just Transition Development Plan, has acted as a major driver of media attention and shifts in the public debate.

- While renewable energy projects, particularly “solar parks”, are portrayed positively, there is limited coverage of long-term environmental challenges such as land re-use, soil remediation, and waste management, issues that remain underrepresented in public discourse.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pavloudakis, F.; Karlopoulos, E.; Roumpos, C. Just transition governance to avoid socio-economic impacts of lignite phase-out: The case of Western Macedonia, Greece. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2023, 14, 101248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziouzios, D.; Karlopoulos, E.; Fragkos, P.; Vrontisi, Z. Challenges and opportunities of coal phase-out in western Macedonia. Climate 2021, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavloudakis, F.; Roumpos, C.; Karlopoulos, E.; Koukouzas, N. Sustainable rehabilitation of surface coal mining areas: The case of Greek lignite mines. Energies 2020, 13, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lypiridi, D. Just Transition Mechanism and Lignite Phase-Out in Greece: Challenges and Prospects. HAPSc Policy Briefs Ser. 2021, 2, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikas, A.; Neofytou, H.; Karamaneas, A.; Koasidis, K.; Psarras, J. Sustainable and socially just transition to a post-lignite era in Greece: A multi-level perspective. Energy Sources Part B Econ. Plan. Policy 2020, 15, 513–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmaki, P.; Tranoulidis, A.; Kouletsos, T.; Giourka, P.; Katarachia, A. Mining transition and hydropower energy in Greece—Sustainable governance of water resources management in a post-lignite era: The case of western Macedonia, Greece. Water 2021, 13, 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlassopoulos, C. Persistent lignite dependency: The Greek energy sector under pressure. Energy Policy 2020, 147, 111825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouzas, C.; Koukouzas, N. Coals of Greece: Distribution, quality and reserves. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 1995, 82, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavouridis, K. Lignite industry in Greece within a world context: Mining, energy supply and environment. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 1257–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouzas, N.; Kakaras, E.; Grammelis, P. The lignite electricity-generating sector in Greece: Current status and future prospects. Int. J. Energy Res. 2004, 28, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Production of Lignite in the EU—Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Production_of_lignite_in_the_EU_-_statistics (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; COM (2019) 640 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 Establishing the Framework for Achieving Climate Neutrality (European Climate Law). Off. J. Eur. Union 2021, L 243, 1–17. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2021/1119/oj (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Mantzaris, N. Conflicting policies threatening the sustainability of Greece’s electricity model: Short history and lessons learnt. Reg. Integr. 2024, 18, 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Dousis, E. The bumpy road to climate neutrality and just transition and the case of Greece. Reg. Integr. 2024, 18, 59–79. [Google Scholar]

- Metaxas, A.; Karageorgiou, D.E.; Varvarousis, G.; Kotis, T.; Ploumidis, M.; Papanikolaou, G. Geological evolution-stratigraphy of Florina, Ptolemaida, Kozani and Saradaporo graben. Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece 2007, 40, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouzas, N.; Ward, C.R.; Li, Z. Mineralogy of lignites and associated strata in the Mavropigi field of the Ptolemais Basin, northern Greece. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2010, 81, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouzas, N. Mineralogy and geochemistry of diatomite associated with lignite seams in the Komnina Lignite Basin, Ptolemais, Northern Greece. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2007, 71, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trachanas, G.P.; Mantzaris, N.; Marinakis, V.; Doukas, H. Multicriteria evaluation of power generation alternatives towards lignite phase-out: The case of Ptolemaida V. Int. J. Multicriteria Decis. Mak. 2022, 9, 17–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarogiannis, T.; Pyrgaki, K.; Krassakis, P.; Koukouzas, N.; Mollerherm, S.; Rogosz, B. Deliverable 1.1, Comprehensive Overview of the Project Report, Web INTEractive Management Tool for Coal Regions in Transition. December 2022, p. 23. Available online: https://winter-project.eu/deliverables/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Ellerman, A.D.; Marcantonini, C.; Zaklan, A. The European Union Emissions Trading System: Ten Years and Counting. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2016, 10, 89–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachou, A.; Pantelias, G. The EU emissions trading system in crisis-ridden Greece: Climate under neoliberalism. Rev. Radic. Political Econ. 2021, 53, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanaki, E.A.; Koroneos, C.J.; Xydis, G.A. Environmental impact assessment of electricity production from lignite. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2016, 35, 1868–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigas, K.; Giannakidis, G.; Mantzaris, J.; Lalas, D.; Sakellaridis, N.; Nakos, C.; Vougiouklakis, Y.; Theofilidi, M.; Pyrgioti, E.; Alexandridis, A.T. Wide scale penetration of renewable electricity in the Greek energy system in view of the European decarbonization targets for 2050. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 42, 158–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manolopoulos, D.; Kitsopoulos, K.; Kaldellis, J.K.; Bitzenis, A. The evolution of renewable energy sources in the electricity sector of Greece. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 12659–12671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment and Energy. National Energy and Climate Plan of Greece; Hellenic Republic: Athens, Greece, 2019. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-03/el_final_necp_main_en_0.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Karasmanaki, E.; Ioannou, K.; Katsaounis, K.; Tsantopoulos, G. The attitude of the local community towards investments in lignite before transitioning to the post-lignite era: The case of Western Macedonia, Greece. Resour. Policy 2020, 68, 101781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Rowlands, I.H. The socio-political context of energy storage transition: Insights from a media analysis of Chinese newspapers. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 84, 102348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, M.; Karhunmaa, K. The German energy transition in the British, Finnish and Hungarian news media. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żuk, P. Soft power and the media management of energy transition: Analysis of the media narrative about the construction of nuclear power plants in Poland. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsbøl, A. Energy transition in and by the local media. Nord. Rev. 2013, 34, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neresini, F.; Giardullo, P.; Di Buccio, E.; Cammozzo, A. Exploring socio-technical future scenarios in the media: The energy transition case in Italian daily newspapers. Qual. Quant. 2020, 54, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Yang, S.; Kim, H. Voices of transitions: Korea’s online news media and user comments on the energy transition. Energy Policy 2024, 187, 114020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szwaja, A.; Rogosz, B.; Szczepiński, J.; Bajcar, A.; Pyrgaki, K.; Krassakis, P.; Karavias, A. The WINTER project: Integrating geospatial technology for sustainable energy transitions in coal regions. Gór. Odkryw. 2024, 65, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrgaki, K.; Krassakis, P.; Karavias, A.; Zarogiannis, T.; Zygouri, E.; Mpatsi, A.; Koukouzas, N. Spatiotemporal Evolution and Renewable Energy Potential in Coal Regions in Transition. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2024, Vienna, Austria, 14–19 April 2024. EGU24-19829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasztelewicz, Z.; Frydrychowicz, D.; Galantkiewicz, E.; Widera, M. The past, present and future of Konin Lignite Mine in central Poland. Geologos 2025, 31, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, J.; David, M. How Germany is phasing out lignite: Insights from the Coal Commission and local communities. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2024, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esiri, A.E.; Kwakye, J.M.; Ekechukwu, D.E.; Benjamin, O. Public perception and policy development in the transition to renewable energy. Magna Sci. Adv. Res. Rev. 2023, 8, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A.; Parks, P. Media and partisanship in energy transition: Towards a new synthesis. Energy Res. Soc. Sci 2024, 108, 103368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; He, P.; Qiu, Y.L. Energy transition, public expressions, and local officials’ incentives: Social media evidence from the coal-to-gas transition in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmeier, Y. Towards a conceptualization and operationalization of agenda-cutting: A research agenda for a neglected media phenomenon. J. Stud. 2020, 21, 2007–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldhahn, D.; Eckart, T.; Quasthoff, U. Building Large Monolingual Dictionaries at the Leipzig Corpora Collection: From 100 to 200 Languages. In Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’12), Istanbul, Turkey, 23–25 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Leipzig Corpora Collection: Greek Newspaper Corpus Based on Material from 2013. Leipzig Corpora Collection, 2013. Available online: https://corpora.uni-leipzig.de/en?corpusId=ell_news_2013 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Leipzig Corpora Collection: Greek Newspaper Corpus Based on Material from 2022. Leipzig Corpora Collection, 2022. Available online: https://corpora.uni-leipzig.de/en?corpusId=ell_news_2022 (accessed on 15 June 2025).

- Loupasakis, C. Contradictive mining–induced geocatastrophic events at open pit coal mines: The case of Amintaio coal mine, West Macedonia, Greece. Arab. J. Geosci. 2020, 13, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrgaki, K.; Zarogiannis, T.; Maraslidis, G.; Zygouri, E.; Batsi, A.; Krassakis, P.; Karavias, A.; Koukouzas, K.; Szwaja, A.; Błachowicz, M.; et al. Deliverable 3.3, Report on the Media Analyses, Web INTEractive Management Tool for Coal Regions in Transition. September 2023, p. 77. Available online: https://winter-project.eu/deliverables/ (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Papathanassopoulos, S.; Karadimitriou, A.; Kostopoulos, C.; Archontaki, I. Greece: Media concentration and independent journalism between austerity and digital disruption. In The Media for Democracy Monitor 2021: How Leading News Media Survive Digital Transformation; Trappel, J., Tomaz, T., Eds.; Nordicom, University of Gothenburg: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 177–230. [Google Scholar]

- Veneti, A.; Karadimitriou, A. Policy and regulation in the media landscape: The Greek paradigm concentration of media ownership versus the right to information. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2013, 1, 439–458. [Google Scholar]

- Tranoulidis, A.; Sotiropoulou, R.E.P.; Bithas, K.; Tagaris, E. Decarbonization and transition to the post-lignite era: Analysis for a sustainable transition in the region of Western Macedonia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldellis, J.K.; Boulogiorgou, D.; Kondili, E.M.; Triantafyllou, A.G. Green Transition and Electricity Sector Decarbonization: The Case of West Macedonia. Energies 2023, 16, 5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolkersdorfer, C.; Walter, S.; Mugova, E. Perceptions on mine water and mine flooding—An example from abandoned West German hard coal mining regions. Resour. Policy 2022, 79, 103035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holum, M. Citizen participation: Linking government efforts, actual participation, and trust in local politicians. Int. J. Public Adm. 2023, 46, 915–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zillich, A.F.; Schlütz, D.; Roehse, E.M.; Möhring, W.; Link, E. Populism, research integrity, and trust. How science-related populist beliefs shape the relationship between ethical conduct and trust in scientists. Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 2024, 36, edae038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N.; Rodriguez, C.; Bolin, G.; Cohen, J.; Goggin, G.; Kraidy, M.M.; Iwabuchi, K.; Lee, K.; Qiu, J.; Volkmer, I.; et al. Inequality and Communicative Struggles in Digital Times: A Global Report on Communication for Social Progress. In CARGC Strategic Documents; Center for Advanced Research in Global Communication (CARGC), Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2018; p. 84. [Google Scholar]

| Corpora Year | Greek Sentences (in Millions) |

|---|---|

| 2013 | 0.6 |

| 2016 | 0.8 |

| 2017 | 0.9 |

| 2018 | 0.6 |

| 2019 | 1.2 |

| 2020 | 2.2 |

| 2021 | 1.9 |

| 2022 | 1.9 |

| Total size | 10.1 |

| Category | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| A | Solidarity/ Identity | Terms reinforcing regional or industrial identity and solidarity. Keywords: St. Barbara, socially acceptable, Mavropigi, Akrini, steam power plant, Megalopoli, Ptolemaida, Western Macedonia, plant, S.P.P. *, J.D.T.P. * |

| B | Site Development | Language describing redevelopment of former coal infrastructure. Keywords: Re-use, Waste, Regeneration, Post-lignite, De-lignification, Post-lignite era, Soil remediation, Deposits/dumps. |

| C | Regional Development | Terms referring to regional socio-economic progress post-transition. Keywords: Transition, Lignite, Carbon, Mine, Coal. |

| D | Technical Tasks | Technical terminology around energy transition and decommissioning. Keywords: Perpetual obligations, drainage, geotechnical. |

| E | Landscape Zone | Lexicon describing geographical and environmental features. Keywords: Productive landscape, solar park, regeneration, territorial plans |

| F | Perception EU | Terms reflecting EU-level framing or policy perception. Keywords: Just Transition, Green Transition, Energy Transition, De-carbonization, Green Deal, Green Fund, European Green Deal, Climate Change, Climate Crisis, SDG, Just Development Transition, Just Development, Transition Plan, National Climate Act, European Directive, Energy Crisis |

| Ν. | URLs | Locality | Number of Headlines | Start Date | End Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | * https://kozan.gr/ | Kozani | 84,110 | 3 December 2016 | 15 August 2023 |

| 2 | * https://e-ptolemeos.gr/ | Ptolemaida | 99,374 | 19 September 2016 | 15 August 2023 |

| 3 | * http://eordaia.org/ | Eordaia | 42,603 | 30 November 2016 | 1 September 2023 |

| 4 | https://eordaialive.com/ | Eordaia | - | - | - |

| 5 | https://www.ptolemaidanews.gr/ | Ptolemaida | - | - | - |

| 6 | https://kozani.tv/ | Kozani | - | - | - |

| 7 | https://neaflorina.gr/ | Florina | - | - | - |

| 8 | https://www.florinapress.gr/ | Florina | - | - | - |

| 9 | https://amyntaionews.gr/ | Florina | - | - | - |

| 10 | https://greveniotis.gr/ | Grevena | - | - | - |

| 11 | https://grevenapress.gr/ | Grevena | - | - | - |

| 12 | https://grevenamedia.gr/ | Grevena | - | - | - |

| 13 | https://kastoria.news/ | Kastoria | - | - | - |

| 14 | https://www.svouranews.gr/ | Kastoria | - | - | - |

| 15 | https://fouit.gr/ | Kastoria | - | - | - |

| 16 | https://sentra.com.gr/ | Kastoria | - | - | - |

| 17 | https://kastoria365.gr/ | Kastoria | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koukouzas, N.; Maraslidis, G.S.; Stergiou, C.L.; Zarogiannis, T.; Manoukian, E.; Haske, J.; Möllerherm, S.; Rogosz, B. Energy Transition in Greece: A Regional and National Media Analysis. Energies 2025, 18, 4595. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18174595

Koukouzas N, Maraslidis GS, Stergiou CL, Zarogiannis T, Manoukian E, Haske J, Möllerherm S, Rogosz B. Energy Transition in Greece: A Regional and National Media Analysis. Energies. 2025; 18(17):4595. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18174595

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoukouzas, Nikolaos, George S. Maraslidis, Christos L. Stergiou, Theodoros Zarogiannis, Eleonora Manoukian, Julia Haske, Stefan Möllerherm, and Barbara Rogosz. 2025. "Energy Transition in Greece: A Regional and National Media Analysis" Energies 18, no. 17: 4595. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18174595

APA StyleKoukouzas, N., Maraslidis, G. S., Stergiou, C. L., Zarogiannis, T., Manoukian, E., Haske, J., Möllerherm, S., & Rogosz, B. (2025). Energy Transition in Greece: A Regional and National Media Analysis. Energies, 18(17), 4595. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18174595