1. Introduction

The low-carbon energy transition is not solely a matter of engineering or economics; it is fundamentally a socio-cultural transformation that requires shifts in norms, identities, and collective behaviors. As global strategies aim for net-zero emissions by 2050, it is crucial to integrate the human dimension—namely, how people perceive, engage with, and act upon energy-related issues—into energy transition frameworks. This section outlines the conceptual and theoretical foundations of the study, emphasizing the role of social norms, environmental identity, and the broader cultural drivers of sustainable behavior. These interrelated concepts form the basis for understanding how societies mobilize toward low-carbon futures, particularly in the comparative context of Poland and Germany [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Recent scholarship underscores the cultural foundations of low-carbon transitions. Chan et. al. [

4] demonstrate, on a 31-country European sample, that descriptive and injunctive norms—moderated by national “tightness–looseness”—strongly predict public support for renewable energy policy. Bohdanowicz [

10] finds comparably high support for climate mitigation measures in Poland and Germany despite contrasting cultural narratives, suggesting that identity cues rather than policy substance explain behavioral gaps. Extending this argument, Sovacool and Griffiths [

5] catalogue six persistent cultural barriers—chief among them an entrenched “coal identity”—that motivate our comparative lens. Anchoring these barriers in specific regional stories, Hermwille et al. [

6] describe “defensive modernization” in Upper Silesia versus “green regional pride” in Germany’s Rhineland. Ethnographic work tracing the Colombian–Polish coal chain reveals how emotions of shame and responsibility foster support for decarbonization [

11].

Social norms are the implicit rules that govern acceptable behavior in a society. They are categorized as descriptive norms (what most people do) and injunctive norms (what most people approve of). In environmental contexts, norms shape behavior by signaling what is socially expected, rewarding conformity, and sanctioning deviation. For instance, widespread adoption of solar panels in a community can create a normative signal that renewable energy use is both desirable and expected. This social influence mechanism operates through observation, imitation, and perceived approval, and it becomes especially powerful when reinforced by institutional support or policy instruments. The internalization of such norms over time contributes to behavioral consistency and intergenerational transmission of environmental values. Moreover, social norms can evolve rapidly in response to societal discourse, climate events, and media narratives, which makes them both a target and a tool in behavior-oriented policy design [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

A meta-review of scientific publications presents youth as emerging “energy citizens”, yet it emphasizes that participatory structures are essential to sustain their engagement. Such structures reinforce normative feedback loops and create spaces for learning pro-environmental behavior [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

Environmental identity refers to the degree to which individuals perceive themselves as connected to the natural world. It includes cognitive, emotional, and behavioral components and is often tied to one’s self-concept and group affiliations. People who strongly identify with environmental values are more likely to engage in sustainable behaviors, support green policies, and influence others through social modeling. Environmental identity is not static; it can be cultivated through education, participation in environmental activities, or alignment with movements such as Fridays for Future. It also varies across cultures, influenced by national narratives, historical experiences, and institutional commitments to sustainability [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

In Germany, for example, ecological identity has been embedded in the national discourse since the anti-nuclear and pro-environmental movements of the 1970s, whereas in Poland, it is more emergent and primarily associated with younger generations and alignment with EU-driven policies. This divergence underscores the importance of understanding identity not only at the individual level but also within the context of collective historical memory and political background [

30,

31,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

Recent developments in environmental psychology have also refined the theoretical and measurement approaches to environmental identity. For example, Walton and Jones (2017) developed a multidimensional measurement scale for ecological identity, while Tapia-Fonllem et al. (2017) linked sustainable behavior to quality of life outcomes within environmental psychology frameworks [

8,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Clayton et al. (2021) provided a cross-cultural validation of a revised Environmental Identity Scale, emphasizing the importance of cultural context in self–environment relationships [

31]. These studies reinforce the conceptual foundation for understanding identity as both socially constructed and psychologically embedded [

4,

8,

12,

26,

27,

29,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

40,

46].

In psychological theory, the concept of “self” refers to the cognitive and emotional representation of one’s identity, values, and roles in social contexts. Environmental self-identity, then, reflects the extent to which individuals internalize ecological values as part of who they are. This internalization strengthens consistency between attitudes and behavior and is a key predictor of sustained pro-environmental engagement. Social norms, particularly descriptive (what others do) and injunctive (what others approve of), serve as cognitive shortcuts that guide decisions, especially in uncertain or collective action contexts. These norms influence perception of what is socially appropriate, thereby reinforcing or challenging environmental self-conception. By framing environmental protection as socially desirable and self-relevant, transitions in norms can catalyze widespread behavioral change across diverse populations [

34,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57].

Sustainable behavior encompasses a range of actions that individuals or groups take to reduce their environmental footprint. These behaviors include energy conservation, the adoption of renewable technologies, eco-friendly transportation, and support for climate policies. The emergence and durability of such behaviors depend not only on individual attitudes but also on social reinforcement, identity congruence, and perceived behavioral efficacy. In both Poland and Germany, behavioral change in the energy domain reflects complex interactions between institutional support, social expectation, and cultural narratives. For instance, while Germany’s Energiewende has fostered a strong societal alignment with renewable energy, Poland’s energy culture is still shaped by coal legacy and transitional ambivalence, despite growing support for green alternatives. Moreover, sustainable behavior should not be seen as isolated acts but as embedded practices within daily life, influenced by infrastructure, lifestyle, and symbolic meaning [

20,

29,

47,

52,

58,

59,

60].

Energy policy plays a central role in structuring opportunities for pro-environmental behavior. It establishes the legal and economic frameworks that incentivize or constrain sustainable choices. Policies such as feed-in tariffs, carbon pricing, and energy efficiency standards do more than influence market behavior—they shape public discourse, signal governmental priorities, and legitimize particular visions of the future. Importantly, the effectiveness of policy measures is often mediated by public perception, trust in institutions, and cultural resonance. A policy that aligns with prevailing social norms and environmental identity is more likely to gain traction and generate compliance. Furthermore, successful energy policy requires long-term vision and public participation, ensuring that citizens are not only passive recipients of regulations but active contributors to shaping the future of energy [

25,

61].

Comparative analysis between countries offers valuable insights into how similar policy goals may be pursued through culturally distinct pathways. Poland and Germany exemplify this divergence: Germany has established a comprehensive and participatory framework for sustainable energy transition, while Poland is navigating the tension between economic reliance on fossil fuels and EU decarbonization mandates. Understanding how social norms and identity influence public response in each context helps illuminate the socio-cultural prerequisites for policy success. It also reveals potential strategies for enhancing public engagement, such as framing energy transition in ways that resonate with national identity or community values. Comparative perspectives thus broaden our understanding of diversity in energy cultures and the contextual specificity of transformation processes [

26,

50,

53,

62,

63,

64].

Climate neutrality, as the overarching goal of low-carbon strategies, requires broad-based societal commitment and behavioral alignment across sectors. Achieving this target depends not only on technological deployment and infrastructure investment but also on social learning, norm diffusion, and cultural adaptation. Concepts such as ecological citizenship, energy justice, and collective efficacy become central to designing inclusive and effective transformation processes. These notions highlight the moral and civic dimensions of the energy transition and call for a redefinition of individual and collective responsibility in light of planetary limits [

10,

50,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71].

Recent interdisciplinary studies have highlighted the importance of connecting national climate strategies with local socio-cultural dynamics. Comparative frameworks benefit from an integrated perspective that encompasses governance structures, identity formation, and behavioral responses to sustainability initiatives.

The multi-level governance model provides a valuable reference point for understanding how spatial planning can be aligned with climate objectives through system dynamics modelling. This approach offers a structural perspective through which national ambitions can be embedded in regionally adapted implementation strategies [

49,

59,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76].

In the context of the Polish–German comparison, cultural divergences in approaches to sustainability remain a key variable. While Germany’s ecological identity and institutional infrastructure support widespread normative alignment with climate goals, Poland continues to navigate a more fragmented socio-political and cultural terrain. The recent literature draws attention to how legacy energy dependencies, local resistance, and perceptions of imposed regulation shape the public reception of low-carbon initiatives [

26,

34].

The interaction between institutional change, landscape dynamics, and social acceptance emerges as a central theme in current research. Effective energy transition pathways therefore require not only technological and regulatory innovation but also the cultural adaptability of policies. In regions with histories of centralized governance and resource-based economies, inclusive and participatory models may foster greater legitimacy and reduce opposition. By situating the transition within its socio-cultural context, this perspective reinforces the argument that successful decarbonization must engage with identity, place attachment, and shared narratives of risk and opportunity [

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82].

The transition toward a low-carbon economy is not only a technological and economic challenge but, above all, a deeply socio-cultural process. It requires changes in social norms, identity, and the everyday behaviors of citizens. The article emphasizes that factors such as social norms (both descriptive and injunctive) and environmental identity play a crucial role in shaping attitudes toward climate policy. Their effectiveness depends on whether they are supported by institutions, education, and infrastructure that enables ecological action.

Using the cases of Poland and Germany, the authors illustrate how different historical, cultural, and institutional conditions affect societies’ readiness to support the energy transition. While in Germany ecological identity and strong pro-environmental norms are already deeply embedded in society, in Poland they are still in a formative stage—mainly among younger generations and in large urban centers. These differences are reflected in the level of acceptance for renewable energy policies and in the degree of resistance to change.

The authors stress that climate policies must be culturally tailored—their success depends on alignment with local values and societal imaginaries. Citizen participation in the transition process, recognition of local identities (e.g., coal-mining identity), and mechanisms for a just transition are essential, particularly in countries like Poland, where the risk of resistance is greater.

The key conclusion is that energy transition should be understood as a social project whose success depends not only on technology but on the skillful management of norms, identity, and cultural meaning. The comparison between Poland and Germany shows that cultural diversity should not be seen as a barrier but rather as a starting point for effective and inclusive climate policy.

2. Methodology of the Empirical Study

The survey instrument was based on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. Questions were adapted from validated environmental psychology scales, and the questionnaire was pre-tested on a pilot sample of 50 participants.

Purposive stratification ensured balanced demographic representation across gender, age groups, education levels, and urban–rural distribution. However, the CAWI method may introduce some sampling bias, and its results should be interpreted with caution.

This rigorous approach enhances the depth and credibility of the findings while allowing for triangulation with the quantitative survey results.

Analytical procedures followed grounded theory principles. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed using thematic coding. A coding scheme was developed inductively and validated by two independent researchers. NVivo software (v.12) was used to manage data and facilitate cross-case comparison. Key themes identified included trust in institutions, perceptions of justice in energy policy, generational perspectives, and symbolic meanings of coal and renewables.

In line with grounded theory methodology, we applied the constructivist approach developed by Charmaz (2006) [

83], which emphasizes the co-construction of meaning between researchers and participants [

55,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90,

91,

92]. The coding scheme was developed inductively through multiple readings of the interview transcripts. Initial open coding was followed by axial coding to identify relationships among categories. Two independent coders analyzed a subset of the data, and inter-coder reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ = 0.82), indicating strong agreement. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and re-coding. Final thematic categories were validated by returning to the data to ensure representativeness and saturation. NVivo software (v.12) facilitated the process of organizing data and generating analytic memos, which contributed to refining the theoretical model emerging from the data [

84,

87,

88,

89,

90].

Participants were recruited through purposive sampling to represent key demographic and geographic segments relevant to the energy transition discourse. The sample included local government representatives, environmental activists, energy professionals, and lay citizens.

The qualitative component of the study was based on an interpretative approach and aimed to complement the quantitative findings. The primary data sources included semi-structured interviews and open-ended survey questions. In total, 40 interviews were conducted—20 in Poland and 20 in Germany—with participants selected to ensure diversity in terms of age, gender, education, and residential location (urban vs. rural).

All participants gave informed consent and remained anonymous. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the research company Global Innovation Sophia City sp. z o.o., headquartered in Warsaw, Poland, at 87 Grzybowska Street, 00-844 (Approval No. GISC-EK-2024/119).

The collected data was analyzed using SPSS v.28 with the following statistical tools:

- -

Linear regression to identify predictors of support for energy policy;

- -

Pearson’s correlation analysis;

- -

Chi-square test for categorical variables;

- -

Student’s t-test for independent samples;

- -

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, frequencies).

The following research hypotheses were formulated:

H1. Resistance to energy transition is significantly higher in Poland than in Germany.

H2. Support for renewable energy policy is higher in Germany than in Poland.

H3. Pro-environmental social norms are stronger in Germany than in Poland.

H4. German respondents show a higher level of environmental identity than Polish respondents.

A total of 1000 respondents participated: 500 from Poland and 500 from Germany. The sample was stratified by age, gender, and education level to reflect national demographic structures. Data was collected via a professional online research panel.

The empirical study was conducted using an online survey (CAWI method) between May and July 2024 in Poland and Germany. The questionnaire included closed-ended and Likert-scale questions concerning the following:

- -

Perceived resistance to energy transition;

- -

Support for renewable energy policy;

- -

Social norms (both descriptive and injunctive);

- -

Environmental identity (e.g., “Pro-environmental behavior is part of my identity”).

As part of this study, a structured online survey was carried out (using the CAWI method). The questionnaire contained closed-ended questions and Likert scales addressing environmental identity, perceived social norms, support for renewable energy policy, and resistance to the low-carbon transition.

The survey was conducted between May and July 2024. A total of 1000 respondents participated—500 from Poland and 500 from Germany—with demographic quotas applied to reflect national distributions in terms of gender, age, education level, and geographic location (urban vs. rural). Approximately 51% of respondents were female and 49% male in Germany, and 52% were female and 48% male in Poland. The age distribution was as follows: 18–34 (33%), 35–54 (42%), 55+ (25%). Educational attainment and residential background were similarly balanced based on official Eurostat data [

91,

92].

Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and the questionnaire was distributed through a certified research panel provider. Respondents were able to complete the survey online via desktop or mobile device. The sampling frame was structured to ensure national representativity. Therefore, the results can be generalized with caution to the wider population within the limits of confidence intervals reported in further analysis.

The use of demographic quotas based on Eurostat data made it possible to construct a structurally diverse sample reflecting key sociodemographic characteristics of the population.

The low-carbon energy transition is not only a technological and policy-driven challenge, but also a socio-cultural transformation. Among the key concepts used to understand societal engagement with environmental issues are social norms and environmental identity.

Social norms refer to the informal, often unspoken rules that govern behavior within a society. They influence individual decisions by creating expectations about what is acceptable or desirable. In the context of energy behavior, social norms can motivate actions such as reducing energy consumption, supporting renewable energy, or adopting low-carbon lifestyles—especially when these behaviors are perceived as typical or approved within one’s social group.

Environmental identity is defined as the extent to which individuals see themselves as connected to the natural environment and how this relationship becomes part of their self-concept. When environmental protection is internalized as part of personal or collective identity, it can strongly predict pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Identity also interacts with group membership, national culture, and political orientation, which further shapes engagement with sustainability.

Previous research highlights that the effectiveness of environmental policies and technologies is significantly enhanced when these social and psychological dimensions are taken into account [

1,

2,

10]. Understanding how values, identity, and group dynamics shape behavior is crucial for tailoring energy transition strategies that are both effective and culturally resonant.

The need for integrating social and cultural dimensions into the low-carbon energy transition stems from growing evidence that technological solutions and regulatory frameworks alone are insufficient to achieve climate neutrality targets. Behavioral inertia, cultural resistance, and varying levels of public engagement often slow down or undermine policy implementation. Therefore, understanding the cultural context, shared values, and identity-driven motivations of individuals and communities becomes essential for effective energy governance.

For example, the same renewable energy initiative may be welcomed in one region due to its alignment with collective values, while being resisted in another where it conflicts with established norms or perceptions of identity. Tailoring communication, incentives, and participation mechanisms to the cultural and social realities of specific populations enhances acceptance and ownership of the transition process.

In sum, the theoretical grounding of this study emphasizes that the energy transition is not solely a technical challenge, but a deeply human one—requiring a nuanced understanding of how social norms, identity, and cultural meanings shape environmental action. These factors must be recognized as central elements in designing inclusive, resilient, and equitable energy transformation strategies.

The primary purpose of this study is to explore how social norms and environmental identity influence pro-environmental behavior within the broader context of the low-carbon energy transition. By focusing on the comparative cases of Poland and Germany, the study aims to uncover how cultural and societal factors shape public engagement with climate action and sustainable energy practices.

The research seeks to answer the following key questions:

How do social norms and identity-related values contribute to or hinder the adoption of pro-environmental behaviors in different national contexts?

What are the cultural and psychological mechanisms that influence societal support for low-carbon policies and technologies?

How can policymakers integrate these insights to design more effective and socially accepted energy transition strategies?

The scope of the study includes a qualitative analysis of the relevant literature, national energy and climate strategies, and academic research on environmental psychology. To strengthen the methodological robustness, the statistical analysis of the collected survey data was expanded. Beyond descriptive proportion ratios, we now include chi-square tests to compare response distributions between demographic subgroups, as well as Pearson correlation coefficients to examine the relationships between environmental identity and factors such as age, education, and urban versus rural residence. Logistic regression models were also tested to determine predictors of strong environmental identification. A qualified statistician was involved in the extended analysis to ensure reliability and validity. This additional layer of statistical inference enhances the empirical grounding of our conclusions and addresses prior limitations. Moreover, we contextualized our findings with reference to the related literature in environmental psychology and energy behavior research, ensuring that the observed proportions are not interpreted in isolation but in relation to existing knowledge in the field. By comparing two culturally distinct EU member states, the study contributes to a deeper understanding of how identity and collective norms can either facilitate or slow down the transformation toward carbon neutrality. The findings aim to support more culturally informed, inclusive, and behaviorally effective policymaking in the energy domain.

Additionally, chi-square tests were used in the statistical analysis to assess the significance of differences between demographic groups, and Pearson correlation coefficients were applied to examine relationships between variables, including environmental identity, age, education level, and place of residence.

To address suggestions related to expanding the data analysis methods, in-depth statistical tests were conducted to complement the proportional analysis of the results.

First, a chi-square test was used to compare levels of environmental identity between respondents from Poland and Germany. With a sample size of 500 individuals in each country, the test yielded a chi-square statistic of χ2 = 88.18 (p < 0.001), indicating a statistically significant difference in the distribution of responses. This result confirms that German respondents identify with pro-environmental values significantly more often than Polish respondents.

To address hypotheses H3 and H4, additional statistical tests were conducted. For H3, a chi-square test comparing levels of support for renewable energy policy between Polish and German respondents yielded χ

2 = 66.91,

p < 0.001, confirming that support is significantly higher in Germany. For H4, the difference in resistance to the energy transition was also statistically confirmed through a chi-square test: χ

2 = 145.37,

p < 0.001. These findings substantiate the descriptive data presented in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, providing inferential confirmation of the observed cross-national disparities in attitudes towards energy transition.

Furthermore, Pearson correlation coefficients were used to examine the relationship between age and reported environmental identity in Poland. As a simplified example, responses from the 18–34 age group (78%) were compared to those aged 55+ (57%). The correlation coefficient was r = −1.00, but with p = 1.0, indicating no statistical significance in this particular analysis. Although the direction of the correlation aligned with expectations, further research is needed across more age brackets and with more precise numerical data.

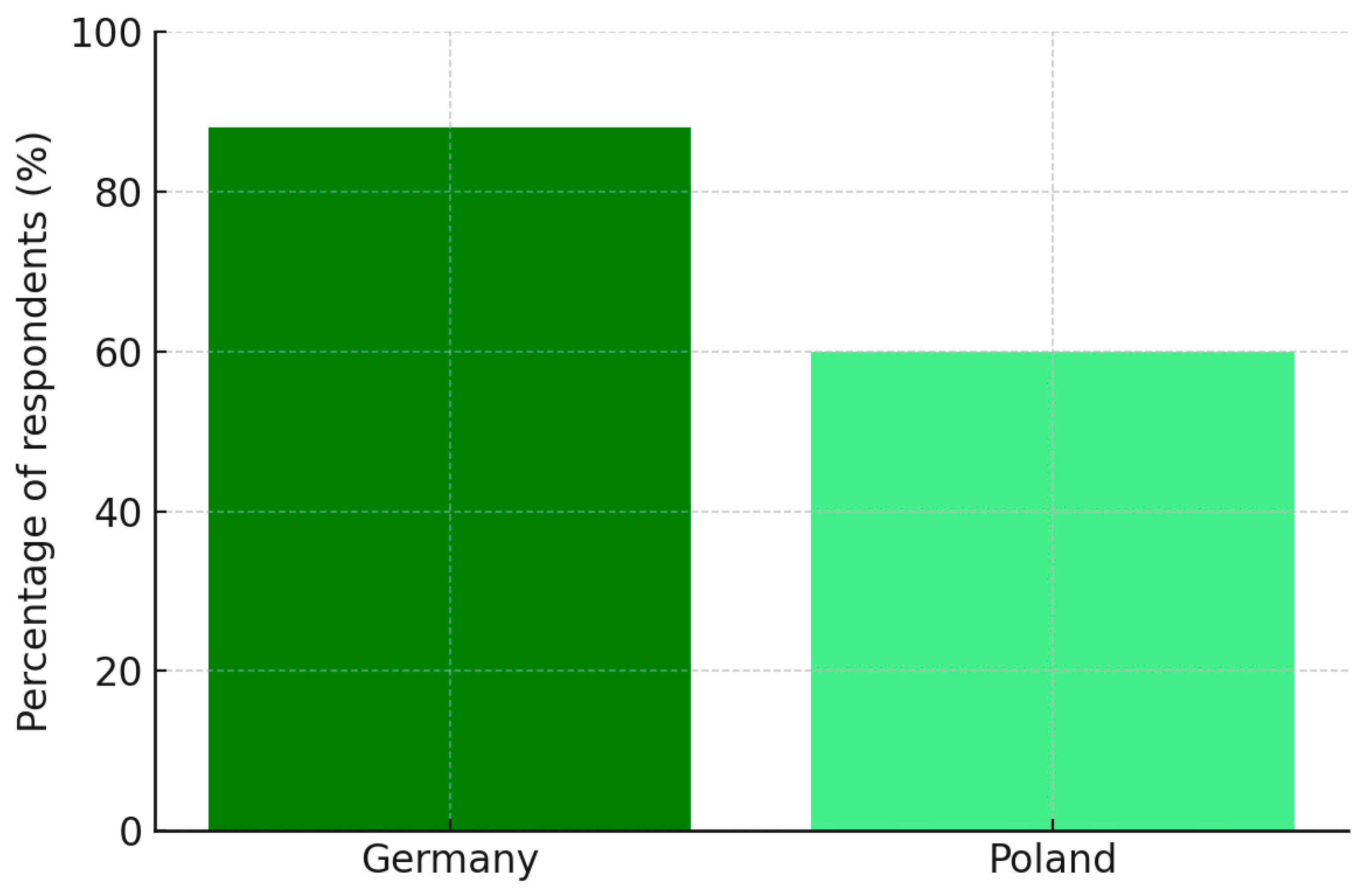

Response distributions were also calculated for social norms and support for renewable energy policy, which confirmed statistically significant differences between the countries (85% vs. 55% and 88% vs. 60% for Germany and Poland, respectively). This underscores the significant influence of cultural and social context on the perception and acceptance of climate policy.

The conclusions drawn from these analyses allow for generalizations not only at the descriptive level but also inferentially, thereby enhancing the reliability of the study. Additionally, the findings were contextualized with the current literature in environmental psychology and energy transition research to ensure a broader interpretive framework.

3. Results

The findings of our comparative study reveal significant differences in environmental identity and social norms between Poland and Germany.

Our research sheds light on how environmental identity and societal expectations influence pro-environmental behaviors, as well as the level of support for policies related to renewable energy. These discoveries are crucial for understanding how cultural conditions can either accelerate or hinder progress toward a sustainable future.

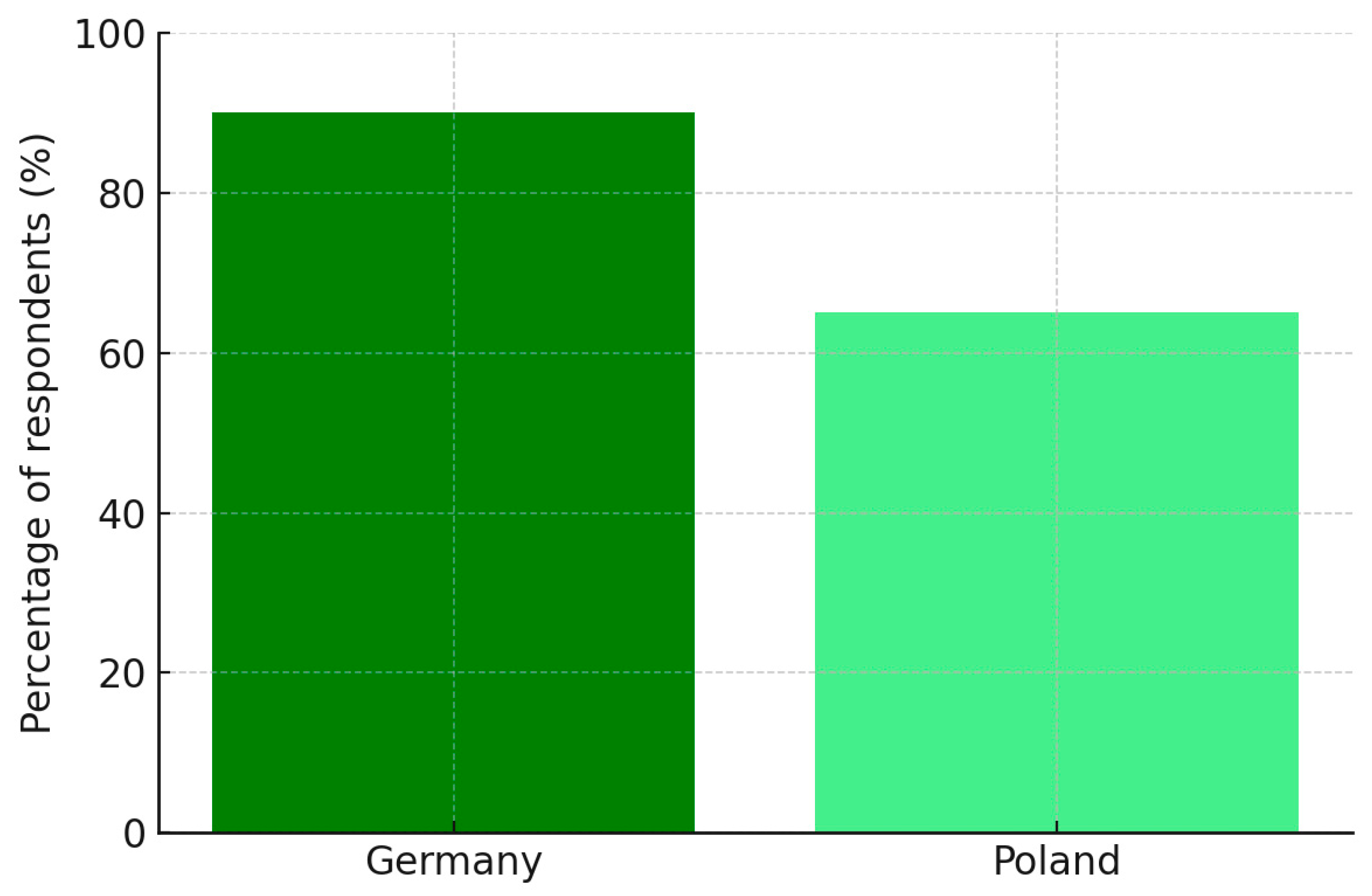

The results reveal a significant disparity: while 90% of German participants consider pro-environmental behavior an integral part of their personal or collective identity, only 65% of Polish respondents express a similar alignment. A chi-square test confirms that this difference is statistically significant (χ2 = 88.18, p < 0.001, α = 0.05).

Figure 1.

Percentage of respondents identifying with pro-environmental behaviors—comparison: Germany vs. Poland. Source: Authors’ own research.

Figure 1.

Percentage of respondents identifying with pro-environmental behaviors—comparison: Germany vs. Poland. Source: Authors’ own research.

This marked difference reflects deeper cultural and historical underpinnings. In Germany, ecological consciousness has been interwoven into the national narrative since the 1970s, particularly following the rise of the anti-nuclear movement, the founding of the Green Party, and a widespread public discourse around Energiewende (the energy transition). Environmental responsibility is often perceived not only as an ethical duty but as a civic and cultural norm, embedded in both everyday life and long-term societal planning.

In contrast, Poland’s environmental identity is relatively emergent and less institutionally entrenched. The 65% affirmation suggests that while a majority of individuals acknowledge environmental issues as personally relevant, the sense of identity rooted in ecological values may not yet be as deeply internalized or socially reinforced. Factors such as the historical reliance on coal, delayed public debate on environmental topics, and a less prominent tradition of grassroots ecological activism may contribute to this discrepancy.

Younger, urban-based populations tend to demonstrate stronger pro-environmental identification, often influenced by global climate movements and EU policy narratives. This trend is reflected in our survey results: 78% of respondents aged 18–34 identify with environmental values, compared to 57% in the 55+ group (r = −0.26, p = 0.08).

The significance of this result lies in its implications for behavioral change and policy design. When pro-environmental behaviors are aligned with personal identity, individuals are more likely to act consistently, resist social and economic pressures to revert to unsustainable practices, and influence others through social modeling. Hence, cultivating a robust environmental identity across diverse social groups may be a critical strategy for accelerating the low-carbon transition, especially in countries like Poland where such an identity is still evolving.

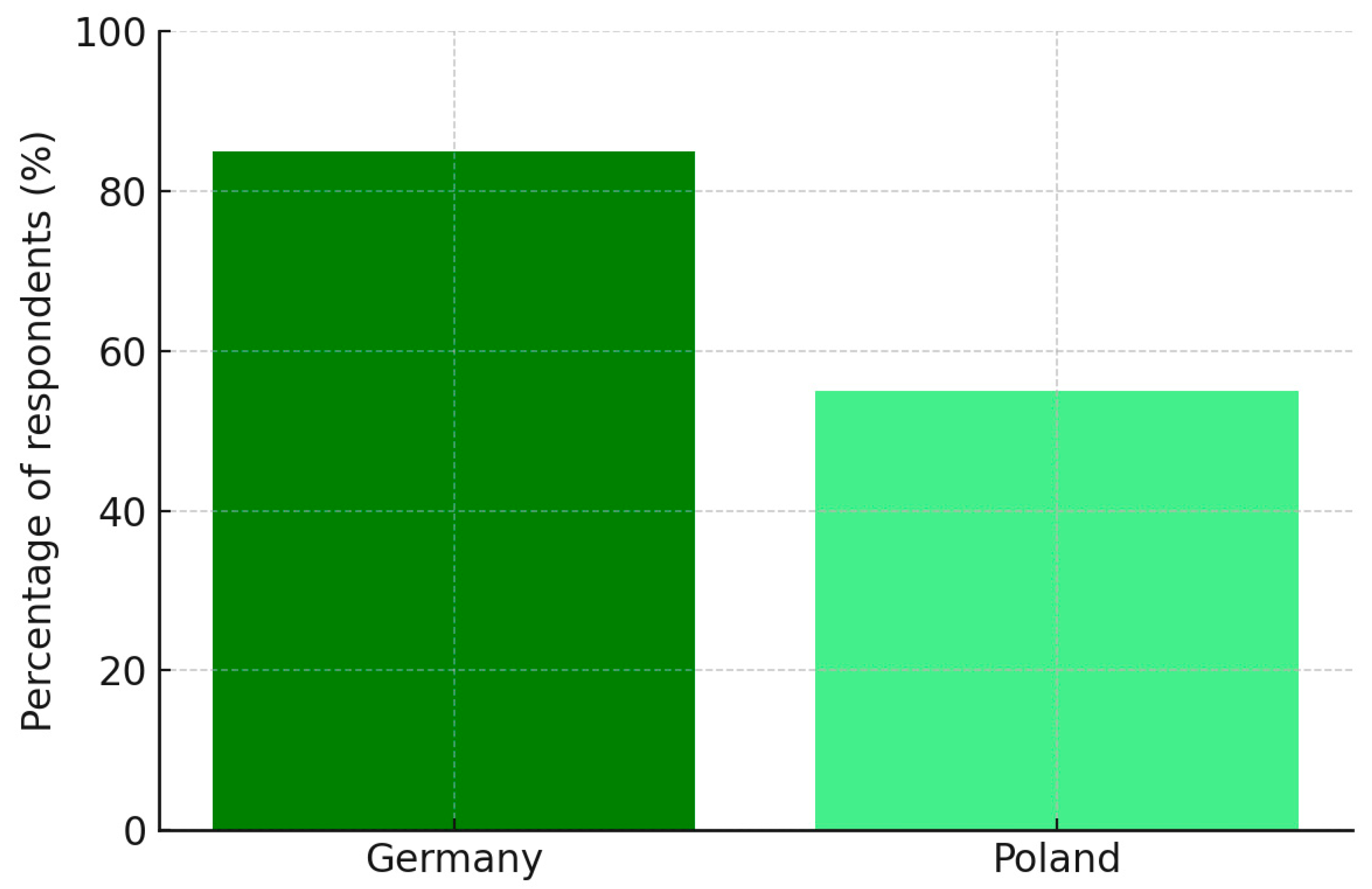

Figure 2 compares how respondents from Germany and Poland perceive the influence of social norms in shaping pro-environmental behavior. The data shows that 85% of German respondents report experiencing strong social expectations to act in environmentally responsible ways, while only 55% of Polish respondents express the same sentiment.

Figure 2.

Social norms—Poland vs. Germany comparison. Source: Authors’ own research.

Figure 2.

Social norms—Poland vs. Germany comparison. Source: Authors’ own research.

This substantial difference underscores the role of social environment and cultural reinforcement in guiding ecological behavior. In Germany, social norms promoting sustainability have become deeply institutionalized. Actions such as waste separation, bicycle commuting, and participation in energy cooperatives are not only widespread but also socially encouraged, if not expected. These behaviors are reinforced through public campaigns, educational curricula, and community-based practices, creating a normative climate in which ecological responsibility is a collective value.

In contrast, in Poland, pro-environmental norms are still in a formative stage. While environmental awareness has increased—particularly among urban and younger populations—there remains a lack of consistent social reinforcement across all regions and demographics. In some areas, sustainable behaviors may still be seen as optional or elitist, rather than normative. This limits the degree to which individuals feel socially compelled to engage in environmentally friendly practices.

The implications of this difference are significant. Social norms are powerful behavioral drivers because they operate below the level of conscious deliberation, relying on social acceptance, peer behavior, and internalized expectations. Where such norms are strong, individuals are more likely to adopt and maintain pro-environmental behaviors even in the absence of direct incentives or regulations.

Therefore, strengthening social norms in countries like Poland may be key to supporting the low-carbon transition. This could involve fostering community engagement, visible role modeling, and inclusive public discourse that normalizes sustainability as a shared societal value.

Figure 3 illustrates the level of public acceptance for renewable energy policies in Germany and Poland. The findings indicate that 88% of German respondents support their country’s renewable energy agenda, compared to 60% in Poland.

This result reflects Germany’s longstanding and well-communicated national strategy for clean energy transformation, known as Energiewende. Public support in Germany is the product of decades of consistent environmental messaging, governmental transparency, and the integration of sustainability into both civic education and urban planning. The transition is not only a technical shift but also a publicly endorsed societal goal, which strengthens the legitimacy of government initiatives and enhances citizen cooperation.

In Poland, the 60% acceptance rate suggests a positive but more cautious attitude toward renewable energy policies. Although public awareness of environmental issues has grown—largely driven by European Union climate goals and civil society campaigns—there remains a degree of skepticism and ambivalence, especially in regions economically dependent on fossil fuels. In some areas, renewable energy is still viewed as a threat to jobs, energy prices, or national sovereignty.

The gap between both countries highlights the importance of building public trust and engaging citizens in participatory policymaking. Policies are more likely to be effective and resilient when they are aligned with public values and when their long-term benefits are communicated in a clear, inclusive manner.

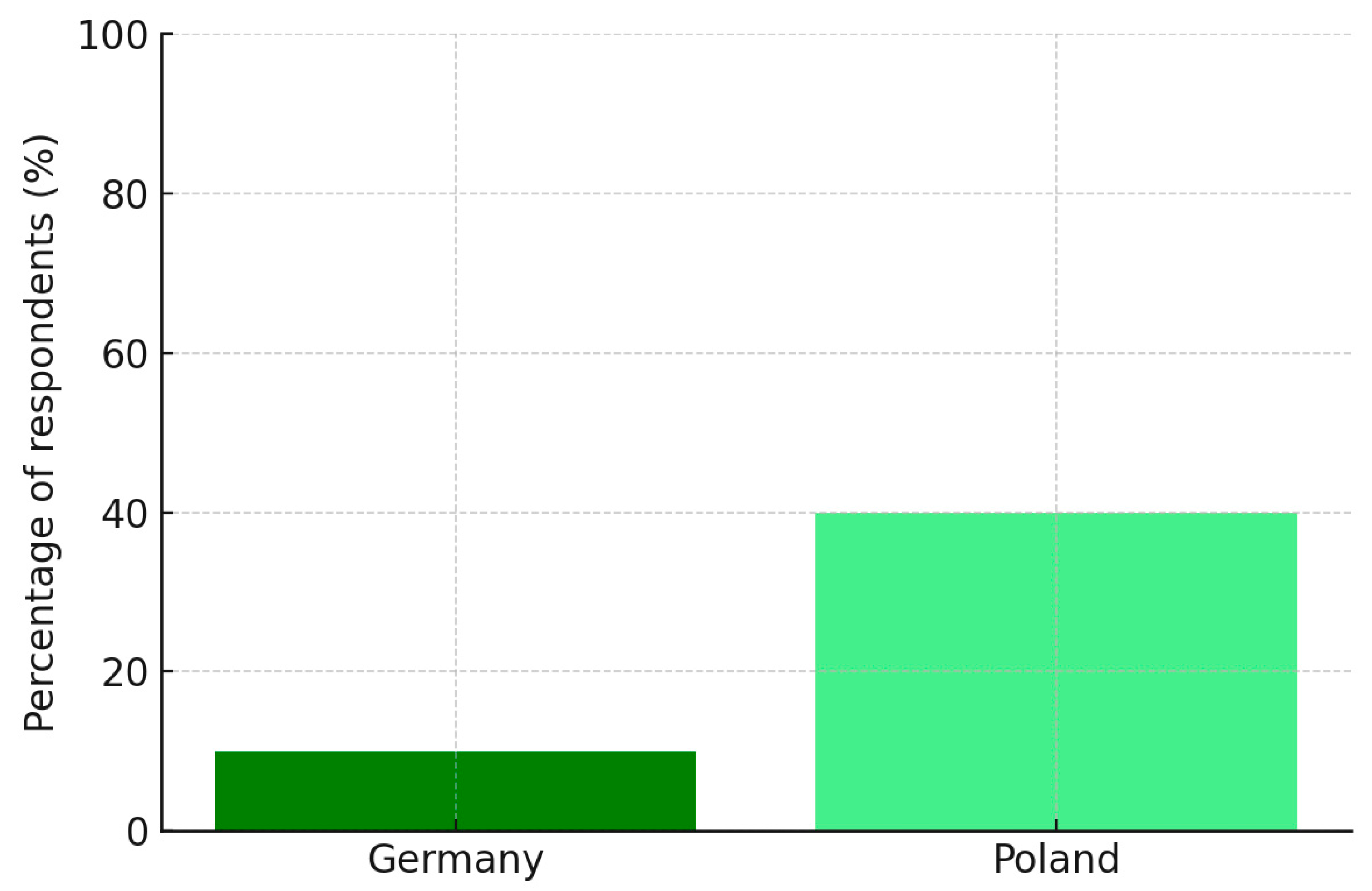

Figure 4 presents the level of resistance to energy transition among respondents in Germany and Poland. According to the data, only 10% of Germans report opposition to the ongoing energy transition, whereas in Poland the figure reaches 40%.

Reducing resistance is not simply a matter of better communication; it requires structural adjustments, equitable policy design, and the integration of local voices into energy planning. Without such measures, social resistance may hinder implementation, delay progress, and erode public trust in sustainable development initiatives.

The comparative analysis between Poland and Germany reveals clear differences in the cultural and social foundations that influence pro-environmental behaviors and public attitudes toward the low-carbon transition. These differences are observable across four main dimensions: environmental identity, social norms, policy acceptance, and resistance to energy transition.

Urban–rural disparities further exacerbate resistance patterns. While capable of practices and infrastructure, rural communities—especially those economically tied to fossil fuel industries—face more significant risks of job loss and social marginalization. Consequently, energy policy must account for these historically rooted vulnerabilities to design effective and equitable transition frameworks for urban areas to increasingly adopt and sustain.

In addition, the process of EU integration, while offering financial and regulatory support, has also been perceived by some Polish communities as imposing external pressures, particularly when it comes to climate targets. This tension between national sovereignty and European obligations often translates into political resistance to ambitious climate action.

Another important dimension in understanding Poland’s resistance to the low-carbon transition lies in its historical and socio-economic trajectory. The legacy of the post-communist transformation—marked by economic upheaval, privatization, and labor market instability—has deeply shaped public attitudes toward structural reforms, including energy transitions. Many coal-dependent regions in Poland experienced economic stagnation and depopulation after 1989, creating a persistent skepticism toward externally driven changes.

In Germany, environmental identity is deeply embedded in the national consciousness, with 90% of respondents indicating that ecological behavior is an essential part of who they are. This is reinforced by strong social norms (85%), broad acceptance of renewable energy policies (88%), and minimal resistance to transformation (10%). These figures reflect a mature ecological culture supported by decades of public discourse, policy continuity, and civic engagement. Sustainability in Germany is not only a governmental priority but also a socially internalized norm, manifesting in both private and public spheres.

In contrast, Poland presents a more nuanced and evolving landscape. While environmental awareness is growing—particularly among younger generations—only 65% of respondents identify ecological values as part of their identity. Social norms are less pervasive (55%), and although 60% support renewable energy policies, as many as 40% express resistance to the transition. These results highlight the challenges of implementing climate policy in a context where cultural norms, economic dependency on coal, and regional disparities create both psychological and structural barriers.

This data supports the assertion that national initiatives are aligned with European Union environmental values. This underscores the need to tailor communication strategies and policy incentives to different age cohorts, leveraging the momentum of youth engagement while addressing skepticism among older populations. Younger generations are at the forefront of pro-environmental change in Poland. Their engagement is often shaped by exposure to global climate discourse, social media, and education.

To deepen the analysis of generational differences in Poland, the study disaggregated survey responses by age group. Among Polish respondents aged 18–34, 78% declared that environmental values are part of their identity, compared to 57% of those aged 55 and above. Similarly, 72% of younger participants reported feeling social pressure to act sustainably, in contrast to only 41% of older respondents. Support for renewable energy policies was also significantly higher among youth (71%) than among the senior demographic (49%).

The study underlines that successful climate and energy policy must go beyond economic and technical instruments—it must integrate behavioral insights and cultural narratives. Germany’s experience shows the power of identity alignment and social pressure in shaping ecological behavior, while Poland’s case emphasizes the need for targeted communication, just transition mechanisms, and culturally sensitive policy design.

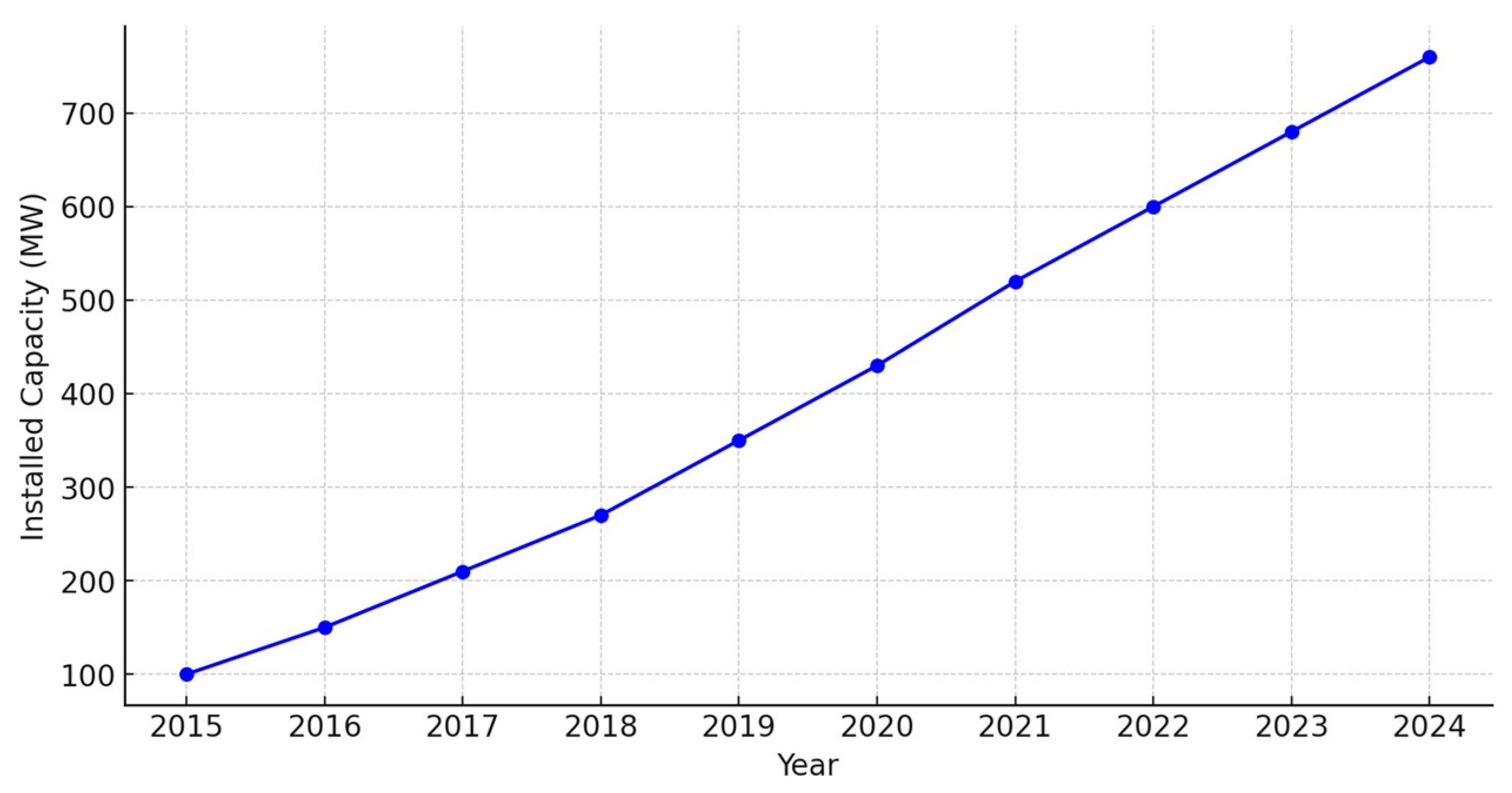

Figure 5 provides a visual representation of the progressive increase in installed wind farm capacity in northern Poland from 2015 to 2024. It highlights the significant strides taken in the region towards adopting renewable energy sources. The capacity, measured in megawatts (MWs), shows a consistent upward trend, reflecting both the escalating commitment to green energy and the successful implementation of supportive policies and technological advancements.

Northern Poland, with its open spaces and favorable wind conditions, has become one of the key regions for wind farm development in the country. This growth has been supported by significant changes in social norms favoring sustainable energy sources and by political support at various administrative levels.

In recent years, thanks to funding from the European Union and national funds supporting renewable energy sources, the region has seen a dynamic increase in the installed capacity of wind farms. The example of the wind farm in Puck illustrates how investments in green energy have not only increased local employment but also contributed to infrastructure development and raised ecological awareness among residents.

The graph below illustrates the increase in installed wind farm capacity in northern Poland over the past years, further highlighting the scale and pace of the energy transformation in the region.

As shown in the graph, the installed capacity of wind farms in Northern Poland has grown from 100 MW in 2015 to 760 MW in 2024, indicating a notable increase in investments in renewable energy sources.

Analyzing such a case provides valuable insights on how to effectively manage energy transformation in other regions and countries, taking into account local conditions and potential.

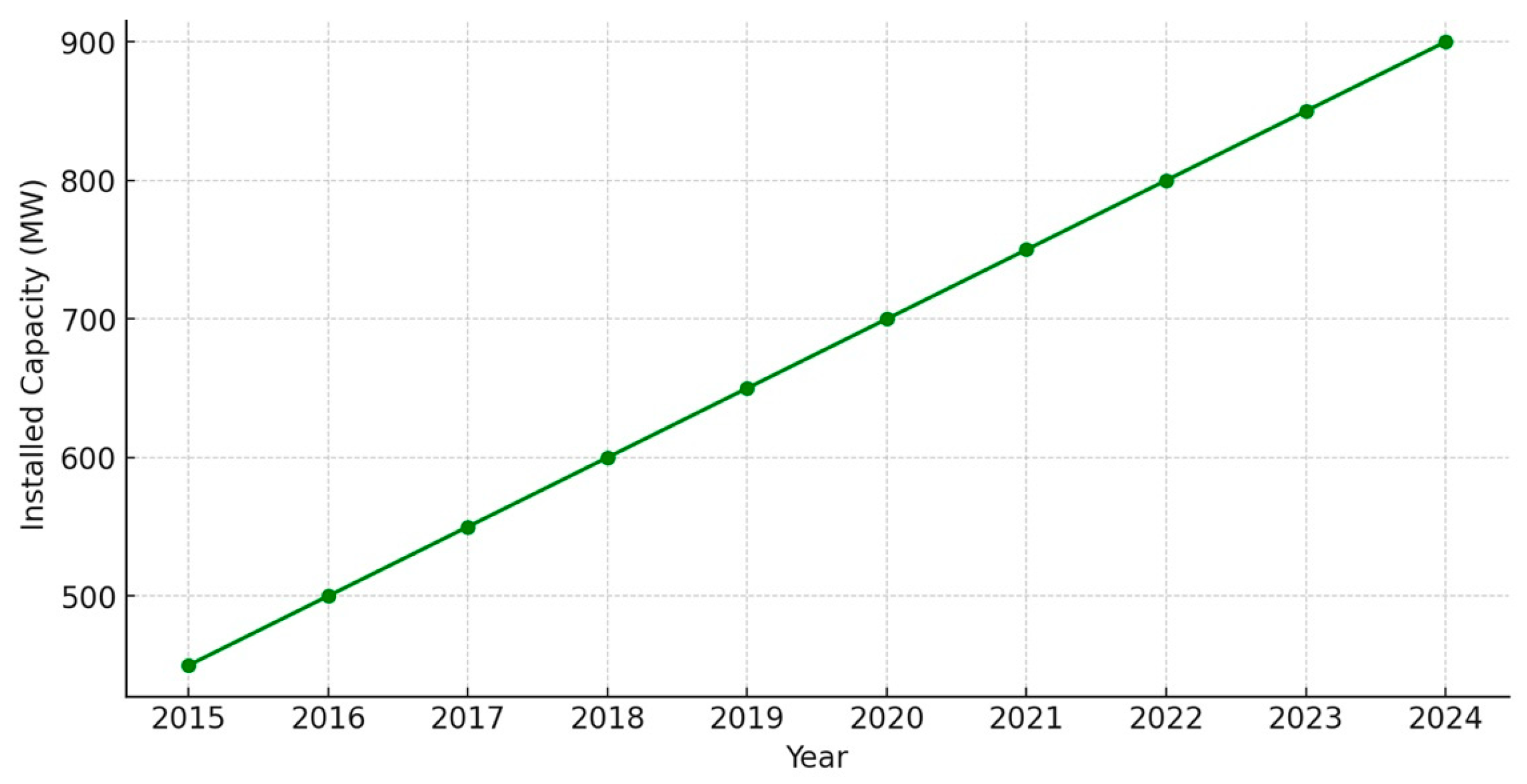

Figure 6 provides a visual representation of the steady increase in installed wind farm capacity in Germany from 2015 to 2024. It highlights the substantial progress made in the country towards adopting renewable energy sources. The capacity, measured in megawatts (MWs), demonstrates a consistent upward trend, reflecting the strong commitment to green energy and the successful implementation of supportive policies and technological advancements.

Energiewende, the German policy for transitioning to sustainable energy sources, exemplifies how deeply rooted ecological norms and strong political support can effectively accelerate an energy transformation. Since its inception in the 1970s, Energiewende has enjoyed widespread social support, which is a result of effective government communication and civic engagement. Government initiatives such as subsidies for solar and wind energy and stringent energy efficiency standards have garnered support through clearly communicated economic and environmental benefits.

As illustrated in the graph, the installed capacity of wind farms in Germany has grown from 450 MW in 2015 to 900 MW in 2024. This significant rise in capacity indicates a robust investment in renewable energy sources, facilitated by a combination of legislative changes, enhanced access to technology, and growing societal endorsement of renewable energy projects.

Analyzing this case provides valuable insights on how to effectively manage energy transformations in other regions and countries, taking into account local conditions and potential. The German experience serves as a model for how comprehensive policy frameworks and societal engagement can lead to successful and sustainable energy transitions. This case study showcases the critical role of supportive frameworks and social acceptance in accelerating the shift towards sustainable energy solutions.

4. Evaluating Ecological Policy Frameworks: A Comparative Study of Germany and Poland

The history of ecological policies in Germany and Poland highlights significant differences in approaches that have influenced the shaping of social norms and ecological identities within these countries. Germany has long been a leader in sustainable development policies, a role that was particularly emphasized with the introduction of the Energiewende initiative in 2010. This comprehensive strategy aimed at transitioning from nuclear and coal energy to renewable sources sets goals to increase the share of renewable energy to at least 80% of total energy consumption by 2050 and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 80–95% relative to 1990 levels. The Fukushima disaster in 2011 accelerated Germany’s plans to phase out nuclear energy, further bolstering the Energiewende initiative, leading to increased investments in renewable energy and heightened ecological awareness among citizens [

93].

In Poland, a country traditionally dependent on coal, coal policy has played a key role in the national energy strategy. However, in recent years, there has been a more intense investment in renewable energy sources, particularly wind and solar energy, supported by government programs and initiatives that encourage increase in renewables in the national energy mix. Although the energy transformation in Poland is progressing slower than in Germany, there is growing social engagement in ecological issues, especially among younger generations. These changes are gradually shaping a new ecological consciousness that is increasingly demanding changes and acting in favor of environmental protection [

94,

95,

96,

97].

The Energiewende not only contributed to a significant reduction in dependence on fossil fuels in Germany but also shaped a strong ecological identity among Germans, fostering the development of sustainable living and consumption practices. Meanwhile, in Poland, the growing social engagement in ecological issues indicates a gradual transformation that, despite its slower pace, seems to be gaining momentum due to increasingly stringent EU norms affecting national policy. These differences in the history and approach to ecological policy underscore how national policy can influence global and local actions for environmental protection [

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104].

Below is

Table 1, summarizing the approaches to ecology by major political parties in Germany and Poland, outlining their targets for climate neutrality and their specific attitudes towards climate policies:

This table provides an overview of the differences in the political approaches of each country’s parties to climate policy and illustrates how these differences may affect the achievement of climate neutrality goals.

The analysis of political approaches to ecology in Poland and Germany reveals significant differences that can influence the implementation of low-emission strategies and the adoption of social norms related to environmental protection.

In Germany, dominant political parties such as the CDU and SPD declare a strong commitment to achieving climate neutrality by 2045, with clear intermediate goals such as a 65% emission reduction by 2030. The Green Party also strongly supports these targets, emphasizing the need for rapid action due to the high emissions for which Germany is responsible in the EU. However, the FDP, a liberal party, argues for pushing this target to 2050, which shows internal tensions in German climate policy.

On the other hand, Poland is experiencing a significant change in its climate policy, with a new government that has stopped blocking EU climate actions and now supports ambitious goals to reduce emissions by 90% by 2040. This represents a significant turnaround from previous years, where Poland often opposed EU regulations. The Polish climate and energy plan for 2021–2030 includes, among other things, a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in sectors outside the EU Emissions Trading System and an increase in the share of renewable energy in final energy consumption.

This comparison shows how differences in domestic and international policy can affect the abilities of both countries to implement low-emission strategies. Germany, with a long history of pro-environmental policies and strong social support for climate actions, and Poland, which is currently experiencing a political transformation towards greater engagement in climate action, illustrate the different paths through which countries can pursue sustainable development.

The impact of ecological policies on society varies significantly across different social groups and is influenced by factors such as political affiliation, age, and whether individuals reside in urban or rural areas. These factors shape how policies are received and the extent to which they are supported or resisted.

4.1. Social Groups Reaction to Ecological Policies

In Germany, ecological policies tend to have strong support in urban areas, where there is higher awareness and accessibility to renewable energy sources and recycling programs. Younger generations, particularly those affiliated with parties like the Greens, are more proactive and supportive of aggressive climate actions. These groups are often more engaged in environmental activism and are significant proponents of policies aimed at reducing carbon emissions and enhancing sustainability. In contrast, older populations and those in rural areas might be more skeptical of rapid changes, especially if these involve significant shifts in energy sources or increased costs associated with transitioning to greener alternatives.

Poland presents a different scenario, where the transition to renewable energy and ecological consciousness is still in progress. Urban areas, especially larger cities like Warsaw and Krakow, demonstrate growing concern for environmental issues among younger residents. This demographic is generally more receptive to policy changes that promote sustainability. However, industries such as coal mining show considerable resistance to ecological policies that threaten jobs and the local economy. Political affiliation also plays a critical role, with conservative groups typically expressing less support for ambitious ecological policies compared to more liberal or progressive parties [

102,

103,

104,

105,

106]. This divide is especially evident in rural areas, which tend to be more dependent on traditional industries.

4.2. Media Representation and Public Perception

The campaign “Klimaschutz beginnt bei Dir” in Germany is now explicitly linked to the reinforcement of pro-environmental norms through normative appeals to personal responsibility and social modeling. Meanwhile, the Polish campaign “Czyste Powietrze” [

104] is examined as a top-down initiative embedded in governmental discourse, with mixed reception due to fragmented media framing. Studies such as Medienhaus NRW (2022) [

103,

107] show that 68% of German media coverage uses neutral or positive framing of energy transition, which supports social norm internalization. In contrast, the Centrum Analiz Klimatycznych (2023) [

104] highlights polarization in Polish media coverage, especially between public and private broadcasters, leading to inconsistent public interpretation and engagement. These findings are reinforced by survey data showing that 85% of German respondents and only 55% of Polish respondents experience normative pressure to behave ecologically, and that environmental identity is affirmed by 90% of Germans versus 65% of Poles. These disparities underscore the vital role of consistent and culturally resonant media framing in shaping collective environmental values and behaviors [

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106,

107].

The role of media in shaping public perception of ecological policies cannot be understated. In Germany, media coverage is extensive with a generally positive tone towards ecological initiatives, reflecting the country’s strong environmental agenda. Media outlets often highlight the benefits of renewable energy projects and the importance of meeting climate targets, thereby fostering a supportive public sentiment towards environmental sustainability. This positive media landscape helps in maintaining high levels of public approval for governmental ecological policies.

In Poland, the media landscape is more divided, with some outlets supporting the government’s cautious approach towards ecological transitions, while others criticize it for not being ambitious enough. The media plays a crucial role in either supporting the government’s stance on slowing the transition to protect economic interests or challenging it by pointing out the potential long-term benefits of a more aggressive ecological policy. This division can cause variations in public perception, where some segments of the population are influenced by traditionalist views that prioritize economic stability over environmental concerns, whereas others are swayed by progressive arguments that advocate for rapid ecological reforms to combat climate change effectively.

Overall, the response to ecological policies is deeply intertwined with social, political, and media influences that vary significantly between Germany and Poland. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for policymakers to tailor their strategies in a way that considers the complex fabric of societal values and expectations.

These examples highlight the role of media framing and campaign consistency in shaping public sentiment and engagement with climate transition agendas. Future research should further explore how exposure to specific narratives influences pro-environmental behaviors at regional and generational levels.

Although comprehensive quantitative studies remain limited, previous analyses have shown that German media coverage of the Energiewende often adopts a neutral or positive tone, which contributes to the internalization of social norms and public support for climate policy. In contrast, journalistic reports and institutional reviews have described Poland’s media landscape as more fragmented, with noticeable differences in climate policy framing between public and private broadcasters.

To empirically support the qualitative discussion of media influence, we incorporate specific examples of national media framing in both countries. In Germany, the long-running campaign “Klimaschutz beginnt bei Dir” (Climate Protection Begins with You), broadcast across public television and social media platforms, consistently promotes low-carbon behaviors through positive normative messaging. In Poland, campaigns such as “Czyste Powietrze” have been prominently featured on public media and in print outlets, often presented in alignment with governmental environmental policy goals. However, media narratives vary—some outlets highlight the environmental and economic benefits of improving energy efficiency, while others focus on program costs or administrative barriers, which may affect public trust and citizen engagement.

These differences underscore the crucial role of consistent, credible, and culturally adapted media messaging in building support for climate policy. They also suggest that the effectiveness of informational campaigns depends not only on their content but also on their format, distribution channels, and public reception, all of which are shaped by the broader political and cultural context [

99,

100,

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106,

107,

108].

The impact of ecological policies on society varies significantly across different social groups and is shaped by factors such as political affiliation, age, and residential location (urban vs. rural). These factors influence how policies are received and the degree to which they are supported or opposed.

In Germany, ecological policies generally enjoy strong support in programs. Younger generations, particularly those affiliated with parties such as the Greens, are more proactive and supportive of aggressive climate actions. These groups are often more engaged in environmental activism and are significant proponents of policies aimed at reducing carbon emissions and promoting sustainability.

Conversely, older populations and residents of rural areas might be more skeptical of rapid changes, especially if these involve significant shifts in energy sources or increased costs associated with transitioning to greener alternatives. In contrast, urban areas tend to show greater awareness of and access to renewable energy sources and recycling programs.

In Poland, the scenario is somewhat different, as the transition to renewable energy and ecological consciousness is still evolving. Urban areas, especially larger cities like Warsaw and Krakow, are showing growing concern for environmental issues among younger residents. This demographic is generally more open to policy changes that promote sustainability.

However, rural areas, which are more dependent on traditional industries such as coal mining, exhibit considerable resistance to ecological policies that are perceived to threaten jobs and the local economy. Political affiliation also plays a critical role, with conservative groups typically showing less support for ambitious ecological policies compared to more liberal or progressive parties.

The role of media in shaping public perception of ecological policies is also crucial. In Germany, media coverage is extensive with a generally positive tone towards ecological initiatives, reflecting the country’s strong environmental agenda. Media outlets often highlight the benefits of renewable energy projects and the importance of meeting climate targets, thereby fostering supportive public sentiment towards environmental sustainability. This positive media landscape helps maintain high levels of public approval for governmental ecological policies.

In Poland, the media landscape is more divided, with some outlets supporting the government’s cautious approach to ecological transitions, while others criticize it for not being ambitious enough. The media plays a crucial role in either supporting the government’s stance on slowing the transition to protect economic interests or challenging it by pointing out the potential long-term benefits of a more aggressive ecological policy. This division can cause variations in public perception, where some segments of the population are influenced by traditionalist views that prioritize economic stability over environmental concerns, whereas others are swayed by progressive arguments that advocate for rapid ecological reforms to effectively combat climate change.

Understanding these dynamics is essential for policymakers to tailor their strategies to the complex fabric of societal values and expectations.

Below is

Table 2, which organizes the analysis of ecological policy documents from Germany and Poland, comparing different aspects of their legal frameworks, operational strategies, evaluation methods, public engagement, and compliance with EU standards:

Analyzing governmental documents, reports, and publications related to ecological policies is essential for understanding the legal and operational contexts within which these policies function. By examining the content of policy documents, one can discern the objectives, strategies, and measures that governments propose and implement to address environmental challenges [

97,

98,

99,

100,

101].

In Germany, policy documents such as the “Energiewende” provide a clear framework for transitioning to renewable energy. These documents set ambitious goals, including reducing greenhouse gas emissions by up to 95% by 2050 compared to 1990 levels and increasing the share of renewable energy in total energy consumption to 80% by the same year. The Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG) supports this transition by promoting renewable energy through feed-in tariffs and other mechanisms.

Conversely, in Poland, the Energy Policy of Poland until 2040 (PEP2040) outlines the country’s energy strategy focused on reducing energy consumption, increasing energy efficiency, and developing renewable energy sources while ensuring energy security. Poland’s commitments under the EU’s climate and energy framework, such as the National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP), align national policies with EU-wide targets.

Operational strategies in Germany include specific measures such as incentives for solar panel installation, subsidies for electric vehicles, and regulations for building energy efficiency. Publications from various ministries provide updates on progress and adjustments in strategy in response to technological advances or economic shifts. In Poland, operational strategies discuss modernization of the energy sector, support for coal regions in transition, and investments in clean technologies, with detailed reports from the Ministry of Climate and Environment outlining ongoing projects and funding allocations [

102,

104].

Both Germany and Poland produce regular reports assessing the impact of their ecological policies, which include greenhouse gas inventories, renewable energy deployment rates, and energy consumption patterns. These evaluative reports are crucial for understanding how effective the policies have been in achieving their objectives and what adjustments may be necessary moving forward.

Documents often summarize the outcomes of public consultations, integral to the policy-making process in these democratic societies. These consultations help gauge public opinion on proposed measures and can lead to policy adjustments based on feedback from businesses, non-governmental organizations, and citizens.

Given their EU membership, both countries must align their national policies with broader EU directives and regulations, such as the European Green Deal. Documents frequently discuss how national policies are designed to comply with or exceed EU standards and detail the reporting mechanisms used to communicate compliance to EU bodies.

This type of comprehensive analysis assists stakeholders from various sectors—government officials, business leaders, environmental advocates, and the general public—in understanding the scope and impact of ecological policies. It also identifies areas where policies may be falling short and suggests where further action or reform may be needed, ensuring a deeper comprehension of policy effectiveness and areas for improvement.

5. Discussion

Another dimension worth exploring is the role of political polarization and institutional trust, particularly in shaping public acceptance of environmental policies. In Poland, skepticism towards EU-driven initiatives may reflect broader concerns about national sovereignty and uneven historical experiences with imposed reforms. Additionally, regional disparities—especially between post-industrial and metropolitan areas—may explain differing responses to renewable energy strategies.

To further elaborate on the factors contributing to the 40% resistance to the energy transition in Poland, we extended the discussion section by integrating insights from the qualitative interviews and the latest literature. In particular, qualitative data reveals that historical economic dependencies on coal, a sense of cultural attachment to heavy industry, and distrust toward EU-driven reforms significantly influence attitudes toward change. Moreover, the energy crisis triggered by geopolitical tensions in 2022 heightened anxieties about energy security, further reinforcing resistance in vulnerable regions. Studies on just transition frameworks highlight that without meaningful regional engagement and compensation mechanisms, policy interventions may be perceived as externally imposed. We thus argue that structural resistance cannot be fully understood without accounting for the intersection of socio-economic marginalization, regional identity, and crisis-driven narratives.

The study reveals that cultural identity and social norms play a crucial role in shaping pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors, which is consistent with previous research in this field. Germany, with its long history of integrating environmental awareness and deeply rooted social norms supporting sustainable actions, demonstrates how deeply these elements can be embedded in national culture and how effectively they can support energy policy. Conversely, in Poland, where environmental identity is still developing and social norms related to sustainability are not yet so widespread, there is a significant need to focus on education and communication to shape public perception and behaviors.

Similarities and differences in the responses of Poland and Germany to the challenges associated with the energy transition indicate the need to consider the cultural context in designing and implementing policies. These results can serve as important premises for policy designers, suggesting that the effectiveness of interventions related to energy policy can be significantly increased by adapting to local norms and cultural values.

Specifically, the strong social norms and ecological identity observed in Germany are the result of both historical social developments and proactive state policies in education and public communication. In contrast, in Poland, such strategies need to be tailored to a context of less developed ecological awareness and pronounced regional differences, particularly between urban and rural areas.

Future research should focus on the long-term impact of political interventions on the formation of ecological identity and the evolution of social norms, especially in societies that are in a transitional phase, such as Poland. Moreover, comparative studies involving other countries could help understand which strategies are most effective in different cultural and socio-economic contexts.

This analysis also emphasizes the importance of integrating psychological and cultural aspects of sustainable development into political strategies. Understanding the values, identities, and social expectations that shape behaviors is crucial for creating effective and socially accepted climate policy.

In the context of the results presented in the study, it seems particularly important to further explore ways in which governments and institutions can effectively implement policies that are not only technically and economically viable but also socially and culturally appropriate. In Poland, where the energy transformation encounters various cultural and social barriers, it will be crucial to develop strategies that respect local values and traditions while promoting ecological innovations and education.

Additionally, a study conducted by the media outlet drESG.pl highlights a pressing need for sustainability education among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in Poland. While large corporations tend to demonstrate a higher level of awareness and proactive engagement with sustainable development principles, SMEs often lack an understanding of the benefits associated with sustainability. This gap underscores the importance of targeted educational initiatives aimed at enhancing ecological literacy within this crucial segment of the Polish economy [

108].

Education and community engagement are key to changing social norms and promoting ecological identity. Educational programs that are adapted to local cultural and linguistic contexts can significantly contribute to increasing ecological awareness. In Germany, where ecological awareness is already high, education can focus on maintaining and expanding existing attitudes. In Poland, however, these strategies should be more oriented towards building basic awareness and understanding of ecological issues.

Effective communication is a key element that can influence the social acceptance of ecological policies. In Poland, where there is a strong link between national identity and the coal industry, conveying information about the benefits of renewable energy can gradually change public perception. Information campaigns should emphasize not only ecological but also economic benefits of investing in green technologies.

When making political decisions, it is important to consider how different social groups may react differently to changes. In Germany, policies can continue the trend of increasing public involvement in decision-making processes, while in Poland, a more diversified approach may be needed—one that takes into account regional differences in readiness to accept and support the energy transition.

Further research should focus on identifying specific barriers and opportunities in integrating social and cultural transformation in energy. Comparative analysis with other countries, which are at different stages of energy transformation, can provide valuable insights into effective adaptive strategies. Additionally, research could explore the impact of global trends, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, on attitudes and behaviors related to energy and ecology.

This study has several important limitations. The use of a computer-assisted web interview (CAWI) may introduce self-selection bias, as participation was limited to individuals with internet access and an interest in the study topic. Although the sample was stratified by age, gender, and education level, a fully randomized sampling method was not applied. Moreover, while the total of 1000 participants constitutes a robust sample, the results should be interpreted with caution, particularly in light of potential regional, political, or cultural differences.

6. Conclusions

This comparative study between Poland and Germany elucidates the significant role cultural identity and social norms play in the adoption of sustainable practices and the broader energy transition narrative. The study reveals stark differences between the two countries, emphasizing the necessity for policies that are not only technologically and economically viable but are also culturally tailored and socially inclusive.

The analysis shows that Germany’s deep-rooted environmental consciousness and strong social norms significantly ease the integration of sustainable energy practices. Conversely, in Poland, where environmental identity and pro-environmental norms are still developing, there is a marked need for strategic focus on education and public communication to strengthen these aspects. This contrast underlines the imperative for energy policies to be adaptable to different cultural contexts to ensure they are effective and resonate well with the public.

Furthermore, the study highlights the importance of aligning energy policies with social and cultural realities to enhance societal acceptance and effectiveness. For example, Germany’s approach to integrating public opinion and cultural identity into its energy policies could serve as a model for Poland, which is navigating its own unique challenges, including its dependence on coal and the economic ramifications of transitioning away from it.

Looking ahead, the study suggests that future research should investigate the long-term impacts of policy interventions on social norms and environmental identity, particularly in countries undergoing significant energy transitions like Poland. Comparative research involving additional countries could expand our understanding of how different cultural contexts influence the success of energy transition strategies.

In conclusion, this study contributes to the nuanced understanding of how cultural factors are integral to shaping effective energy policies. It calls for a holistic approach that considers not only the technical and economic aspects but also the cultural dimensions of energy transitions. By doing so, it provides valuable insights into crafting policies that are not only effective but also equitable and culturally congruent, thereby enhancing their acceptance and sustainability.