Green Goals, Financial Gains: SDG 7 “Affordable and Clean Energy” and Bank Profitability in Romania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Development of Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Bank Profitability and SDG Reporting

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data Sources and Sample

3.2. Variables and Models

3.2.1. Dependent and Independent Variables

- Recurring earning power (REP), computed as pre-impairment operating earnings over total assets, shows the bank’s ability to achieve profitability in a constant and sustainable manner, avoiding risks related to profitability [30]. The lack of risk exposure is highlighted in the numerator of the indicator, which takes into account pre-impairment operating profit. This rate is used in the literature as a proxy for earnings stability because it assumes that all current operating conditions remain constant [31,32].

- Loans yield (LY), calculated as net interest income over net loans, is a profitability measure that shows a bank’s ability to generate earnings from its lending activities [30]. Indicators that take into account net interest income are considered a more robust performance measure, superior to alternative ratios such as ROA and ROE, because they assess the efficiency of banks’ use of their interest-bearing assets [27]. Conversely, ROA and ROE represent the overall performance that encompasses both loans and market investments.

- Return on assets (ROA), extensively used in the literature to capture management performance [8,33,34,35], is calculated as total net income over total assets. A high ROA helps strengthen the bank’s reputation, which attracts new depositors and borrowers, reduces early withdrawals, and increases working capital by using accumulated profits [36].

- Return on equity (ROE), calculated as net income over equity, shows the return to stockholders and is influenced by leverage [22,24,35,37,38]. Unlike ROA, which is influenced solely by the income-generating capacity of assets, ROE is also affected by the methods used to finance these assets [26] and shows stockholders’ perspective [8].

- indicators related to energy consumption (REnC) and energy intensity level of primary energy (EnInt). Renewable energy consumption is the share of total energy consumption, while the energy intensity level of primary energy (EnInt) is the ratio between energy supply and gross domestic product measured at purchasing power parity. They are also used in other studies such as [15,40,41,42] and have a mixed impact on bank profitability;

- bank size (size), calculated as the logarithm of total assets [20], is a good indicator of the adaptation of banks’ balance sheets to sustainable development, with larger banks expected to have more resources to transition to renewable energy and be subject to more pressure from stakeholders to implement the SDGs [35]. However, the current literature has not agreed on the type of influence exerted by size, which has an uncertain impact [26,35,43,44];

- deposit-taking activity (DA), determined as total deposits over total assets, is expected to have a positive effect on financial performance [38,43], as deposits are a cheap and stable financial resource when compared to other financing alternatives [44]. However, government-provided insurance protections make deposit demand a significant contributor to agency problems, which might negatively affect profitability [44];

- banking corporate governance structures (CEO gender—CEO and shareholder structure—own). CEO is a dummy variable, coded as 1 when the CEO is a female and 0 otherwise, and is expected to have a mixed impact, based on existing literature [45,46]. Own is a categorical variable, with 3 categories: 1—Romanian ownership, 2—foreign ownership, and 3—mixed ownership. It is expected from foreign investors to show greater concern and to demand more transparency from the companies in which they have invested [18].

3.2.2. Models

4. Results

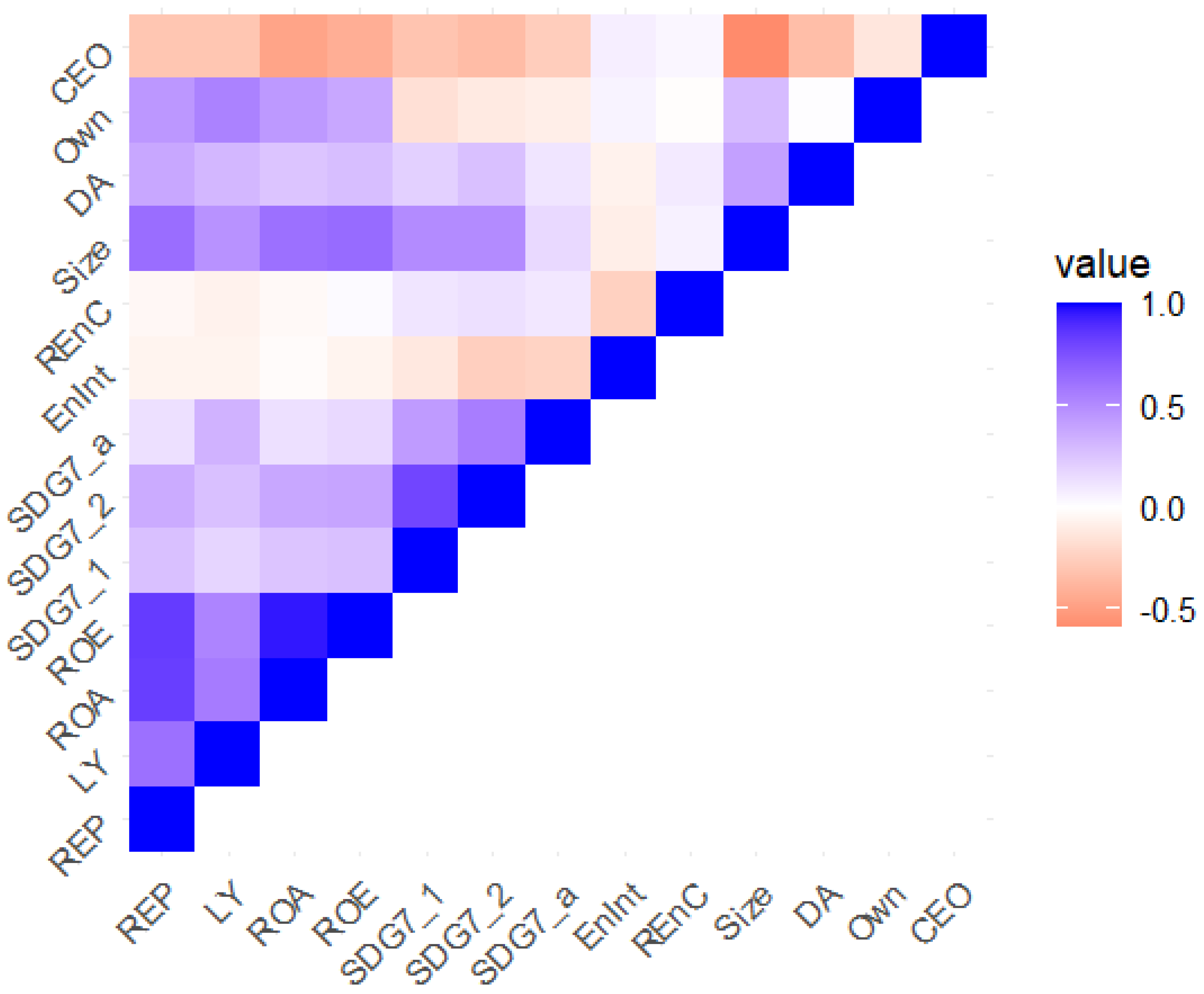

4.1. Descriptive Analysis and Correlation Matrix

| Categories | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEO | ||||

| -frequency | 96 | 14 | ||

| -percentage | 87.27 | 12.73 | ||

| Own | ||||

| -frequency | 16 | 53 | 41 | |

| -percentage | 14.55 | 48.18 | 37.27 |

4.2. Empirical Analysis

| Variables | REP | LY | ROA | ROE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| SDG7_1 | −0.4660 *** | −0.0026 | −0.0041 ** | −0.0272 * |

| SDG7_2 | 0.3115 ** | −0.0009 | 0.0032 ** | 0.0208 * |

| SDG7_a | 0.0526 | 0.0016 | 0.0001 | 0.0015 |

| EnInt | −1.0040 ** | −0.0141 *** | −0.0075 | −0.0831 * |

| REnC | 0.5775 | −0.0110 | 0.0106 | 0.1599 * |

| Size | −0.8658 ** | −0.0009 | −0.0067 | −0.0669 * |

| DA | −2.2832 *** | −0.0032 | −0.0302 *** | −0.2902 *** |

| Own | 0.7112 * | 0.0023 | 0.0198 *** | 0.1771 *** |

| CEO | −0.4195 | 0.0026 | −0.0050 * | −0.0453 * |

| constant | 5.1816 | 0.3471 | −0.1295 | −2.5146 |

| R-squared | 0.4272 | 0.3911 | 0.5073 | 0.5326 |

| Obs | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 |

| Year Dummies | yes | yes | yes | yes |

4.3. Robustness Checks

| Variable | fpc |

|---|---|

| SDG7_1 | −0.7377 *** |

| SDG7_2 | 0.4976 ** |

| SDG7_a | 0.0759 |

| EnInt | −1.8938 ** |

| REnC | 1.8477 |

| Size | −1.4368 ** |

| DA | −5.1507 *** |

| Own | 2.8869 *** |

| CEO | −0.8667 * |

| constant | −17.1611 |

| R-squared | 0.5160 |

| Obs | 93 |

| Year Dummies | yes |

| Variable | REP | LY | ROA | ROE | REP | LY | ROA | ROE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| SDG7_1 | −0.4635 *** | −0.0025 | −0.0041 ** | −0.0272 * | −0.4806 *** | −0.0022 | −0.0043 ** | −0.0310 * |

| SDG7_2 | 0.3183 ** | −0.0008 | 0.0032 ** | 0.0207 * | 0.3410 *** | −0.0007 | 0.0043 *** | 0.0303 ** |

| SDG7_a | 0.0426 | 0.0013 | 0.0001 | 0.0016 | 0.0197 | 0.0014 | −0.0006 | −0.0039 |

| EnInt | −1.0368 ** | −0.0152 *** | −0.0075 | −0.0827 * | −0.9246 ** | −0.0090 * | −0.0017 | −0.0481 |

| REnC | 0.7093 | −0.0067 | 0.0106 | 0.1580 | 0.5278 | −0.0245 ** | −0.0009 | 0.0991 |

| Size | −0.8956 ** | −0.0018 | −0.0067 | −0.0664 * | −0.8790 * | 0.0085 | −0.0010 | −0.0492 |

| DA | −2.2708 *** | −0.0028 | −0.0302 *** | −0.2904 *** | −2.4439 *** | −0.0045 | −0.0359 *** | −0.3409 *** |

| Own | 0.7261 * | 0.0028 | 0.0198 *** | 0.1768 *** | ||||

| CEO | 0.3912 | −0.0035 | 0.0050 | 0.0457 * | ||||

| WBoD | −0.2421 | −0.0078 | 0.001 | 0.0035 | ||||

| CpR | −3.7201 | 0.1137 ** | −0.0089 | −0.4816 | ||||

| constant | 2.2894 | 0.2697 *** | −0.1339 | −2.2542 | 8.4328 | 0.4913 ** | 0.0810 | −0.9897 |

| R-squared | 0.4294 | 0.4120 | 0.5073 | 0.5327 | 0.3732 | 0.4312 | 0.3125 | 0.3548 |

| Obs | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 | 93 |

| Year Dummies | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | REP | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 2 | LY | 0.62 | 1.00 | |||||||||||

| 3 | ROA | 0.83 | 0.57 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 4 | ROE | 0.84 | 0.53 | 0.96 | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 5 | SDG7_1 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.25 | 0.27 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 6 | SDG7_2 | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.39 | 0.80 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 7 | SDG7_a | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.43 | 0.56 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 8 | EnInt | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.02 | −0.06 | −0.12 | −0.25 | −0.23 | 1.00 | |||||

| 9 | REnC | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.10 | −0.24 | 1.00 | ||||

| 10 | Size | 0.63 | 0.47 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.16 | −0.09 | 0.06 | 1.00 | |||

| 11 | DA | 0.38 | 0.31 | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.11 | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.41 | 1.00 | ||

| 12 | Own | 0.45 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.38 | −0.16 | −0.11 | −0.09 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.29 | 0.01 | 1.00 | |

| 13 | CEO | −0.30 | −0.30 | −0.47 | −0.42 | −0.31 | −0.35 | −0.26 | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.59 | −0.34 | −0.13 | 1.00 |

References

- Sebastião, A.M.; Tavares, M.C.; Azevedo, G. Evolution and Challenges of Sustainability Reporting in the Banking Sector: A Systematic Literature Review. Adm. Sci. 2024, 14, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manko, K.; Watkins, T.A. Microfinance and SDG 7: Financial impact channels for mitigating energy poverty. Dev. Pract. 2022, 32, 1036–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Frijat, Y.S.; Al-Msiedeen, J.M.; Elamer, A.A. How Green Credit Policies and Climate Change Practices Drive Banking Financial Performance. Bus. Strat. Dev. 2025, 8, e70090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghami, S.A. The role of economic policies in achieving sustainable development goal 7: Insights from OECD and European countries. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Circular Economy, Banks, and Other Financial Institutions: What’s in It for Them? Circ. Econ. Sust. 2021, 1, 787–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Broadstock, D.C. Does economic, financial and institutional development matter for renewable energy consumption? Evidence from emerging economies. IJEPEE 2015, 8, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrampou, A.; Skouloudis, A.; Iliopoulos, G.; Khan, N. Advancing the Sustainable Development Goals: Evidence from leading European banks. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 743–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.; Marimuthu, M.; Mat Isa, M.P.B.M. The nexus of sustainability practices and financial performance: From the perspective of Islamic banking. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Buallay, A.; Al Marri, M.; Nasrallah, N.; Hamdan, A.; Barone, E.; Zureigat, Q. Sustainability reporting in banking and financial services sector: A regional analysis. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2023, 13, 776–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K. Sustainable Development Goals and bank profitability: International evidence. Mod. Financ. 2023, 1, 70–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, A.; Rahman, H.U.; Zahid, M.; Salameh, A.A.; Khan, P.A.; Al-Faryan, M.A.S.; Che Aziz, R.B.; Ali, H.E. Islamic corporate sustainability practices index aligned with SDGs towards better financial performance: Evidence from the Malaysian and Indonesian Islamic banking industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 405, 136860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, M.; Fraccalvieri, I.; Cuoccio, M.; Bussoli, C. Answering the call to action: An empirical analysis of SDG performance in global banks. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyznarska-Dworczak, B.; Fijałkowska, J.; Garsztka, P.; Mamić Sačer, I.; Mokošová, D.; Săndulescu, M.-S. Sustainability performance efficiency in the banking sector. Econ. Res.-Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2218473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, C.-N.; Albu, N.; Dumitru, M.; Fota, M.-S.; Guşe, R.G. Sustainability reporting in Central and Eastern European countries. In Research Handbook on Sustainability Reporting; Rimmel, G., Aras, G., Baboukardos, D., Krasodomska, J., Nielsen, C., Schiemann, F., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2024; pp. 400–417. ISBN 978-1-0353-1626-7. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, T.; Kamran, M.; Djajadikerta, H.G.; Sarker, T. Can Banks Sustain the Growth in Renewable Energy Supply? An International Evidence. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2023, 35, 20–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.M.; Umair, M.; Hu, J. Green finance and renewable energy growth in developing nations: A GMM analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampone, G.; Nicolò, G.; Sannino, G.; De Iorio, S. Gender diversity and SDG disclosure: The mediating role of the sustainability committee. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2024, 25, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, M.M.M. An empirical analysis of SDG disclosure (SDGD) and board gender diversity: Insights from the banking sector in an emerging economy. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2024, 22, 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Goyal, S. Determinants of SDG Reporting by Businesses: A Literature Analysis and Conceptual Model. Vis. J. Bus. Perspect. 2022, 09722629221096047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidari, G.; Djajadikerta, H.G. Factors influencing corporate social responsibility disclosures in Nepalese banks. Asian J. Account. Res. 2020, 5, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Khan, H.Z.; Bakshi, S. Determinants and consequences of sustainable development goals disclosure: International evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 140021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Homaidi, E.A.; Tabash, M.I.; Farhan, N.H.S.; Almaqtari, F.A. Bank-specific and macro-economic determinants of profitability of Indian commercial banks: A panel data approach. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2018, 6, 1548072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erin, O.A.; Olojede, P. Do nonfinancial reporting practices matter in SDG disclosure? An exploratory study. Meditari Account. Res. 2024, 32, 1398–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buniamin, S.; Jaffar, R.; Ahmad, N.; Johari, N.H. Exploring SDGs Disclosure among Public Listed Companies in Malaysia: A Case of Energy-related SDGs. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 762–776. [Google Scholar]

- Nizam, E.; Ng, A.; Dewandaru, G.; Nagayev, R.; Nkoba, M.A. The impact of social and environmental sustainability on financial performance: A global analysis of the banking sector. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2019, 49, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre Olmo, B.; Cantero Saiz, M.; Sanfilippo Azofra, S. Sustainable Banking, Market Power, and Efficiency: Effects on Banks’ Profitability and Risk. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Umar, M.; Su, C.-W.; Mirza, N. Renewable energy, credit portfolios and intermediation spread: Evidence from the banking sector in BRICS. Renew. Energy 2023, 208, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeazzo, A.; Miandar, T.; Carraro, M. SDGs in corporate responsibility reporting: A longitudinal investigation of institutional determinants and financial performance. J. Manag. Gov. 2024, 28, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BNR. Banca Naţională a României Raport Anual 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.bnro.ro/Raport-anual-2023-28053-Mobile.aspx (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Huian, M.C.; Mironiuc, M.; Mihai, O.I. Studying banking performance from an accounting perspective: Evidence from Europe. Theor. Appl. Econ. 2018, XXV, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- De Haan, J.; Scholtens, B.; Shehzad, C.T. Growth and Earnings Persistence in Banking Firms: A Dynamic Panel Investigation. SSRN J. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, P.K.; Uadiale, O. Ownership concentration and bank profitability. Future Bus. J. 2017, 3, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltweri, A.; Sawan, N.; Al-Hajaya, K.; Badri, Z. The Influence of Liquidity Risk on Financial Performance: A Study of the UK’s Largest Commercial Banks. JRFM 2024, 17, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.D.; Ngo, T. The determinants of bank profitability: A cross-country analysis. Cent. Bank Rev. 2020, 20, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caby, J.; Ziane, Y.; Lamarque, E. The impact of climate change management on banks profitability. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 142, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.V.; Vo, D.V. Determinants of Liquidity of Commercial Banks: Empirical Evidence from the Vietnamese Stock Exchange. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 699–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naili, M.; Lahrichi, Y. The determinants of banks’ credit risk: Review of the literature and future research agenda. Int. J. Fin. Econ. 2022, 27, 334–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, Z.; AlGhazali, A.; Samour, A. GCC banks liquidity and financial performance: Does the type of financial system matter? Futur. Bus. J. 2024, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalis, T.A.; Malamateniou, K.E.; Koulouriotis, D.; Nikolaou, I.E. New challenges for corporate sustainability reporting: United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for sustainable development and the sustainable development goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. 2020, 27, 1617–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sueyoshi, T.; Goto, M. Energy Intensity, Energy Efficiency and Economic Growth among OECD Nations from 2000 to 2019. Energies 2023, 16, 1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.; Sequeira, T.; Cerqueira, P. Renewable energy consumption and economic growth: A note reassessing panel data results. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 19511–19520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anton, S.G.; Afloarei Nucu, A.E. The effect of financial development on renewable energy consumption. A panel data approach. Renew. Energy 2020, 147, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoun, R.; Coskun, A.; Georgievski, B. Determinants of financial performance of banks in Central and Eastern Europe. Bus. Econ. Horiz. 2018, 14, 513–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saona, P. Intra- and extra-bank determinants of Latin American Banks’ profitability. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2016, 45, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huian, M.C.; Curea, M.; Apostol, C. The association between governance mechanisms and engagement in commercialisation and entrepreneurship of Romanian public research institutes. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palvia, A.; Vähämaa, E.; Vähämaa, S. Are Female CEOs and Chairwomen More Conservative and Risk Averse? Evidence from the Banking Industry During the Financial Crisis. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 131, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazziotta, M.; Pareto, A. Synthesis of Indicators: The Composite Indicators Approach. In Complexity in Society: From Indicators Construction to their Synthesis; Maggino, F., Ed.; Social Indicators Research Series; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 70, pp. 159–191. ISBN 978-3-319-60593-7. [Google Scholar]

- Mazziotta, M.; Pareto, A. Principal component analysis for constructing socio-economic composite indicators: Theoretical and empirical considerations. SN Soc. Sci. 2024, 4, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Rice, J. Little Jiffy, Mark Iv. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, J.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ionașcu, A.E.; Gheorghiu, G.; Spătariu, E.C.; Munteanu, I.; Grigorescu, A.; Dănilă, A. Unraveling Digital Transformation in Banking: Evidence from Romania. Systems 2023, 11, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farisyi, S.; Musadieq, M.A.; Utami, H.N.; Damayanti, C.R. A Systematic Literature Review: Determinants of Sustainability Reporting in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tăchiciu, L.; Fulop, M.T.; Marin-Pantelescu, A.; Oncioiu, I.; Topor, D.I. Non-Financial reporting and reputational risk in the Romanian financial sector. Amfiteatru Econ. 2020, 22, 668–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, F.; Carletti, E.; Goldstein, I.; Leonello, A. Moral Hazard and Government Guarantees in the Banking Industry. J. Financ. Regul. 2015, 1, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunea, M.; Dinu, V. The impact of the gender diversity on the Romanian banking system performance. Transform. Bus. Econ. 2018, 17, 42–59. [Google Scholar]

- Studenmund, A.H. Using Econometrics: A Practical Guide, 7th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, S.S. Green finance, sustainability disclosure and economic implications. Fulbright Rev. Econ. Policy 2023, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuer, S.; Tröger, T.H. The Role of Disclosure in Green Finance. J. Financ. Regul. 2022, 8, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A.; Fadel, S.M.; Al-Ajmi, J.Y.; Saudagaran, S. Sustainability reporting and performance of MENA banks: Is there a trade-off? Meas. Bus. Excel. 2020, 24, 197–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beretta, V.; Demartini, M.C.; Trucco, S. From sustainability to financial performance: The role of SDG disclosure. Meas. Bus. Excell. 2024, 29, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Investment Bank Romania to Expand Clean Energy Production with EUR30 Million EIB Support for Major New Wind Farm. Available online: https://www.eib.org/en/press/all/2025-139-romania-to-expand-clean-energy-production-with-eur30-million-eib-support-for-major-new-wind-farm (accessed on 22 May 2025).

- Michelon, G.; Pilonato, S.; Ricceri, F. CSR reporting practices and the quality of disclosure: An empirical analysis. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 33, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachdi, H. What Determines the Profitability of Banks During and before the International Financial Crisis? Evidence from Tunisia. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Manag. 2013, 2, 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Adom, P.K.; Amuakwa-Mensah, F.; Amuakwa-Mensah, S. Degree of Financialization and Energy Efficiency in Sub-Saharan Africa: Do Institutions Matter? Financ. Innov. 2020, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidell, M. Air pollution and worker productivity. IZA World Labor 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, S.; Rosati, F.; Venturelli, A. The determinants of business contribution to the 2030 Agenda: Introducing the SDG Reporting Score. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2021, 30, 404–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REP | 93 | 1.62 | 0.91 | −0.93 | 3.91 | ||

| LY | 93 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.09 | ||

| ROA | 93 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.03 | ||

| ROE | 93 | 0.09 | 0.08 | −0.12 | 0.26 | ||

| SDG7_1 | 110 | 0.80 | 0.94 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 3.77 | 0.27 |

| SDG7_2 | 110 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 3.18 | 0.31 |

| SDG7_3 | 110 | 0.87 | 0.96 | 0.00 | 2.00 | ||

| SDG7_a | 110 | 0.67 | 0.90 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 1.58 | 0.63 |

| EnInt | 110 | 2.39 | 0.14 | 2.12 | 2.62 | 1.15 | 0.87 |

| REnC | 110 | 23.52 | 0.30 | 23.00 | 24.10 | 1.09 | 0.92 |

| Size | 110 | 16.61 | 1.27 | 14.09 | 18.95 | 2.52 | 0.40 |

| DA | 110 | 0.76 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.92 | 1.27 | 0.79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Curea, M.; Huian, M.C.; Zecca, F.; Balu, F.O.; Mironiuc, M. Green Goals, Financial Gains: SDG 7 “Affordable and Clean Energy” and Bank Profitability in Romania. Energies 2025, 18, 3252. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18133252

Curea M, Huian MC, Zecca F, Balu FO, Mironiuc M. Green Goals, Financial Gains: SDG 7 “Affordable and Clean Energy” and Bank Profitability in Romania. Energies. 2025; 18(13):3252. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18133252

Chicago/Turabian StyleCurea, Mihaela, Maria Carmen Huian, Francesco Zecca, Florentina Olivia Balu, and Marilena Mironiuc. 2025. "Green Goals, Financial Gains: SDG 7 “Affordable and Clean Energy” and Bank Profitability in Romania" Energies 18, no. 13: 3252. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18133252

APA StyleCurea, M., Huian, M. C., Zecca, F., Balu, F. O., & Mironiuc, M. (2025). Green Goals, Financial Gains: SDG 7 “Affordable and Clean Energy” and Bank Profitability in Romania. Energies, 18(13), 3252. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18133252