Sustainability and Resilience Assessment Methods: A Literature Review to Support the Decarbonization Target for the Construction Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

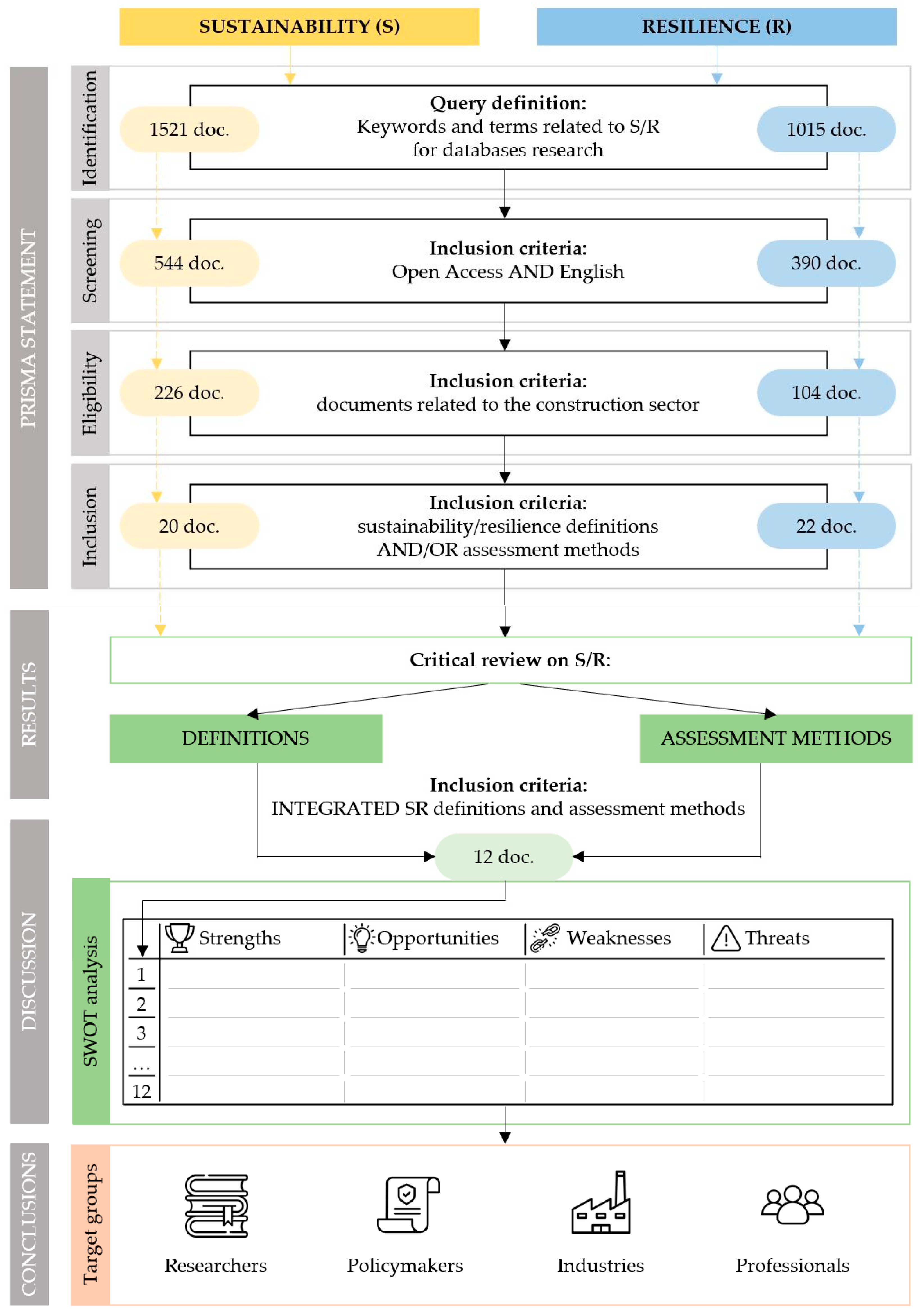

2. Methodology

3. Sustainability in Construction: Definitions and Assessment Methods

3.1. Sustainability Definitions for the Construction Sector

3.2. Sustainability Assessment Methods for the Construction Sector

4. Resilience in Construction: Definitions and Assessment Methods

4.1. Resilience Definitions for the Construction Sector

4.2. Resilience Assessment Methods for the Construction Sector

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

- (i)

- Researchers can identify in each reviewed method a starting point for structuring integrated sustainability and resilience analysis methodologies for each value chain of the construction sector. In particular, researchers can find in the framework developed by Chhabraet al. [70] a rational probabilistic approach that can be easily integrated with LCA analyses to calculate the trade-offs within different design alternatives.

- (ii)

- Policymakers can find in the methodologies developed by Angeles et al. [73] and Asadi et al. [72] a unified multi-criteria framework to promote the adoption of specific construction methods, sustainable and resilient materials, and energy-efficient technologies. In particular, Angeles et al. [73] studied a method that easily integrates life cycle assessment (LCA) analyses and BIM methodology in order to evaluate building SR levels. At this stage, however, the studies on the application of the two methods are restricted to low- and mid-rise buildings with specific characteristics.

- (iii)

- Industries of the construction value chain have increased their interest and awareness about their sustainability assessment and resilience evaluation level in recent decades with a higher peak after the pandemic emergency. The initial application of those concepts was focused principally on the economic sphere of both sustainability and resilience, specifically for the production and selling categories of the industry. With the increased awareness of the potentialities of the S and R assessment also for other spheres such as social and environmental ones, industries have started to invest in procedures to certify their overall sustainability level concerning market needs and requests for technologically resilient and innovative products. Referring to the Roostaie et al. [76] and Sesana [79] studies, they can implement some lessons learned for the decarbonization path sector, assessing their SR level in comparison with the currently available results for some companies. Using the DEMATEL approach, they can assess whether their operations are sustainability enhancers or detractors based on their impacts. However, the application and diffusion into practice of this method are limited by the long duration and large number of queries on which it is structured and the need for advanced skills to perform the assessment. While the SARIA methodology [79], being developed specifically for steel construction industries, is a user-friendly ready-to-use assessment methodology for these specific industries and needs an adaptation for use by other value chains, nevertheless, being a tool developed in such a clear and modular structure, it can be easily adapted, slightly integrating specific details for another industry value chain.

- (iv)

- Professionals may use the frameworks proposed by Yang et al. [69] and Asadi et al. [71] to analyze and compare the available materials and construction solutions and categorize them according to stakeholders’ preferences and risk levels. Additionally, professionals can also take into consideration the use of the Taherkhani et al. [75] method to study the possibility of executing building renovations through urban district regeneration. All those methods are limited by the need for advanced skills to perform the analysis and detailed data available only by a specific data-monitoring collection and campaign.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Author/s (Year) | Research Objective | Sustainability Definitions for the Construction Sector |

|---|---|---|

| Kibert (1994) [80] | Sustainable construction | “Sustainable construction represents the creation and responsible management of a healthy built environment based on ecological and resource-efficient principles”. |

| Vanegas, DuBose, Pearce (1995) [81] | Sustainable design and construction | “Sustainable designers and constructors will approach each project with the entire life cycle of the facility in mind, not just the initial capital investment. Instead of thinking of the built environment as an object separate from the natural environment, it should be viewed as part of the flow and exchange of matter and energy which occurs naturally within the biosphere”. |

| Bourdeau (1999) [82] | Sustainability in construction sector | “…reaching sustainable development through environmental, socio-economic and cultural aspects. It is divided into three parts: (i) Management and organization, (ii) Product and building issues, and (iii) Resources consumption”. |

| CIB, UNEP-IETC (2002) [83] | Sustainable construction | “...principles of sustainable development are applied to the comprehensive construction cycle, from the extraction and beneficiation of raw materials, through the planning, design and construction of buildings and infrastructure, until their final deconstruction and management of the resultant waste. It is a holistic process aiming to restore and maintain harmony between the natural and built environments, while creating settlements that affirm human dignity and encourage economic equity”. |

| Ortiz, Castekks, Sonnemann (2009) [84] | Sustainable construction | “Enhancing quality of life and thus improve social, economic and environmental conditions for future generations”. |

| Edum-Fotwe, Price (2009) [40] | Sustainable construction | “Meet the needs of the present and future generation without compromising our and their living standards”. |

| Oyegoke, McDermott, Abbott (2009) [34] | Sustainable construction | “Encompasses diverse areas covering construction process (supply chain) and business development”. |

| Shen, Tam, Tam, Ji (2010) [85] | Sustainable construction companies | “About construction business, sustainability is about achieving a win-win outcome for contributing to the improved environment and the advanced society, and at the same time for gaining competitive advantages and economic benefits for construction companies”. |

| Akadiri, Chinyio, Olomolaiye (2012) [26] | Sustainable building | “The practice of sustainable building refers to various methods in the process of implementing building projects that involve less harm to the environment, increased reuse of waste in the production of building material, beneficial to the society, and profitable to the company”. |

| Berardi (2013) [86] | Sustainable building | “A sustainable building can be defined as a healthy facility designed and built in a cradle-to-grave resource-efficient manner, using ecological principles, social equity, and life-cycle quality value, and which promotes a sense of sustainable community”. |

| Castro, Mateus, Bragança (2014) [87] | Sustainable building | “A building is a sustainable building when it is built in an ecologically oriented way that reduces its impact on the environment”. |

| Yilmaz, Bakis (2015) [19] | Sustainable construction | “Sustainable construction is application of sustainable development principles to a building life cycle from planning the construction, constructing, mining raw material to production and becoming construction material, usage, destruction of construction, and management of wastes. It is a holistic process which aims to sustain harmony between the nature and constructed environment by creating settlement which suit human and support economic equality”. |

| Spinks (2015) [88] | Sustainable building | “Sustainable building is both a social and a physical construct. As a social construction, it involves a process of interaction amongst different groups with the shared goal of addressing and producing action that will progress a sustainability agenda. As a physical construction, a sustainable building is a process of technical engagement of materials and system flows which collectively contribute to the production of a structure that fulfils the principles of a sustainability agenda”. |

| Conte (2018) [89] | Sustainable construction | “Sustainable construction symbolizes the great, all-embracing, promise to contribute significantly to sustainable development, locally and globally, improving the built environment while protecting the natural environment—the way to establish a balance between human life and nature without one prevailing over the other and, thus, their long-lasting coexistence”. |

| Liu, Pyplacz, Ermakova, Konev (2020) [90] | Sustainable construction | “Sustainable Construction is defined as a construction process, which is carried out by incorporating the basic objectives of Sustainable Development. Such construction processes would thus bring environmental responsibility, social awareness, and economic profitability to a new built environment and facilities for the wider community”. |

| Goh, Chong, Jack, Faris (2020) [91] | Sustainable construction | “Sustainable construction ensures the delivery of environmental, social and economic sustainability in a balanced and optimal manner, without one pillar dominating any others”. |

| Arcila Novelo, Alvarez Romero, Corona Suarez, Morales Ramirez (2021) [92] | Social sustainability in the construction sector | “SS in construction projects is the capacity of buildings to positively contribute to the SDGs, and human rights of persons directly or indirectly involved in any of the stages of the life cycle, considering that people in conditions of poverty and vulnerability are those who receive the strongest adverse effects of unsustainable lifestyles, consumption, and construction”. |

| Utomo, Astarini, Rahmawati, Setijanti, Nurcahyo (2022) [93] | Sustainable building | “Sustainable buildings are intended as buildings designed and built to reduce the adverse effects of human activities, based on three main pillars, namely the economic aspects, social aspects, and environmental aspects”. |

| Li, Wang, Zhang (2022) [94] | Sustainable building and construction industry | “In the building and construction industry, sustainability can be specified as minimizing waste and negative environmental impacts, maintaining low energy and resource consumption, and maximizing safety and efficiency throughout the full life cycle—planning and design (PD), construction (C), operation and maintenance (OM), and end of use or demolition of buildings (ED)”. |

| Vickram, Lakshmi (2023) [95] | Sustainable construction materials | “Materials that are selected and developed from extraction and manufacture through transportation and disposal to minimize environmental effects”. |

Appendix B

| Author/s (Year) | Research Object | Resilience Definitions for the Construction Sector |

|---|---|---|

| Bosher (2008) [96] | Resilient built environment | “A resilient built environment as one designed, located, built, operated, and maintained in a way that maximises the ability of built assets, associated support systems (physical and institutional) and the people that reside or work within the built assets, to withstand, recover from, and mitigate the impacts of threats”. |

| Madni, Jackson (2009) [97] | Resilience engineering | “the ability to build systems that are able to circumvent accidents through anticipation, survive disruptions through recovery, and grow through adaptation”. |

| Haigh, Amaratunga (2011) [98] | Resilient built environment | “A resilient built environment will ensue when we design, develop and manage context sensitive buildings, spaces and places that have the capacity to resist or change in order to reduce hazard vulnerability, and enable society to continue functioning, economically, socially, when subjected to a hazard event”. |

| Bocchini, Frangopol, Ummenhofer, Zinke (2013) [99] | Civil infrastructure resilience | “resilience is associated with the ability to deliver a certain service level even after the occurrence of an extreme event, such as an earthquake, and to recover the desired functionality as fast as possible”. |

| Jennings, Vugrin, Belasich (2013) [100] | Resilient building | “Resilient buildings are often thought of as structures that exceed minimum code requirements so that the key building systems continue to function, enabling the continued operation of the building”. |

| Pearson, Flanery (2013) [101] | Urban resilience | “The capacity of the city (built infrastructure, material flows, etc.) to undergo change while still maintaining the same structure, functions and feedbacks, and therefore identity”. |

| The White House (2013) [102] | Resilience in the built environment and critical infrastructure | “the ability to prepare for and adapt to changing conditions and withstand and recover rapidly from disruptions”. |

| Faller (2013) [103] | Building resilience | “Buildings resilience could be seen as an ability to withstand the effects of earthquakes, extreme winds, flooding and fire, and their ability to be quickly returned after such event”. |

| Sedema (2014) [104] | Resilient cities | “the ability of citizens to absorb shocks and reorganize while undergoing climate change, through decentralization of activities, the diversity of economic sources, decoupling between economic development and emissions, the integration of the city with natural ecosystems, social cohesion, and redundancy”. |

| Zaho, McCoy, Smoke (2015) [105] | Resilient built environment | “RBE exists as equilibrium among the facilities that populate the environment and the functions needed from that environment. […] The environment might require attributes in facilities (demand), whereas facilities attempt to fit within the greater functions that serve society (supply) and maintain a baseline of balance”. |

| Champagne, Aktas (2016) [106] | Building resilience | “A building’s ability to withstand severe weather and natural disasters along with its ability to recover in a timely and efficient manner if it does incur damages”. |

| Marjaba, Chidiac (2016) [30] | Building resilience | “a building resilience is a measure of the building’s ability to recover from or adjust easily to an unlucky condition, event, or change”. |

| Phillips, Troup, Fannon, Eckelman (2017) [9] | Resilience in building context | “A building that resists physical damage, may be quickly and cost-effectively repaired if damaged, and maintains key building functionality either throughout a disruptive event or restores a target operation level more quickly after such an event occurs”. |

| Lupíšek, Růžička, Tywoniak, Hájek, Volf (2018) [107] | Building resilience | “A single building is resilient if it has the ability to quickly adapt to changes in conditions and continue to function smoothly” |

| Moazami, Carlucci, Geving (2019) [108] | Resilient building | “A resilient building is a building that not only is robust but also can fulfill its functional requirements during a major disruption. Its performance might even be disrupted but has to recover to an acceptable level in a timely manner in order to avoid disaster impacts”. |

| Hewitt, Oberg, Coronado, Andrews (2019) [109] | Resilience in buildings | “Resilience in buildings [...] is framed as the ability of the building to serve the occupants’ needs in times of crisis or shocks. [...] The capacity of a building to sustain atypical operating conditions in disaster situations, rather than succumbing to building failure, is the critical measure of its resilience”. |

| Sun, Specian, Hong (2020) [110] | Building resilience | “The ability of a building to prepare for, withstand, recover rapidly from, and adapt to major disruptions due to extreme weather conditions”. |

| De Angelis, Ascione, De Masi, Pecce, Vanoli (2020) [111] | Resilience of the built environment | “The resilience of the built environment can be defined as the capacity to sustain operations under both expected and unexpected conditions”. |

| The BRE Group (2020) [112] | Resilience in the built environment | “The capacity of built assets and infrastructure to endure acute shocks and chronic stresses while successfully adapting to long term changes”. |

| Homaei, Hamdy (2021) [113] | Resilient building | “The building is defined to be resilient if it is able to prepare for, absorb, adapt to and recover from the disruptive event” |

| Nagy, Adnan (2022) [114] | Resilient building | “A resilient building is a building that achieves a collection of important aspects such as the social aspects that is represented in the improvement of the internal environment of the building”. |

| Jia, Zhan (2023) [10] | Resilience in civil engineering | “Resilience refers to the ability of systems to resist and recover from the external disasters. […] In civil engineering, resilience refers to the ability of system to resist or recover from the disasters, such as earthquakes, floods, and blasts”. |

References

- UN Climate Change Conference COP28, United Arab Emirates, Global Stocktake Report, December 2023. Available online: https://unfccc.int/topics/global-stocktake (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- UN Climate Change Conference, COP21, Paris Agreement, Paris Climate Change Conference—November 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/184656 (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Who Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter, Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-4-003422-8.

- Achour, N.; Pantzartzis, E.; Pascale, F.; Price, A. Integration of resilience and sustainability: From theory to application, International. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2015, 6, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mari, S.I.; Lee, Y.H.; Memon, M.S. Sustainable and resilient garment supply chain network design with fuzzy multi-objectives under uncertainty. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, M.; Cagno, E.; Colicchia, C.; Sarkis, J. Integrating sustainability and resilience in the supply chain: A systematic literature review and a research agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2021, 30, 2858–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Castro, L.F.; Solano-Charris, E.L. Integrating Resilience and Sustainability Criteria in the Supply Chain Network Design. A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roostaie, S.; Nawari, N.; Kibert, C. Sustainability and resilience: A review of definitions, relationships, and their integration into a combined building assessment framework. Build. Environ. 2019, 154, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.; Troup, L.; Fannon, D.; Eckelman, M.J. Do resilient and sustainable design strategies conflict in commercial buildings? A critical analysis of existing resilient building frameworks and their sustainability implications. Energy Build. 2017, 146, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Zhan, D.J. Resilience and sustainability assessment of individual buildings under hazards: A review. Structures 2023, 53, 924–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtagh, N.; Scott, L.; Fan, J. Sustainable and resilient construction: Current status and future challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 268, 122264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU/2023/1791) on Energy Efficiency (EED Recast) (OJ C, C/2023/1553, 19.12.2023, ELI). Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/C/2023/1553/oj (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Cholewa, T.; Balaras, C.A.; Kurnitski, J.; Mazzarella, L.; Siuta-Olcha, A.; Dascalaki, E.; Kosonen, R.; Lungu, C.; Todorovic, M.; Nastase, I.; et al. Energy Efficient Renovation of Existing Buildings for HVAC Professionals-REHVA GB No.32; REHVA Office: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; ISBN 978-2-930521-31-2. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey, C.; Keogh, J.; Tiwari, M.S.; Artioli, N.; Manyar, G. Techno-Economic Assessment and Sensitivity Analysis of Glycerol Valorization to Biofuel Additives via Esterification Krutarth Pandit. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 9201–9210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesana, M.M.; Rivallain, M.; Salvalai, G. Overview of the Available Knowledge for the Data Model Definition of a Building Renovation Passport for Non-Residential Buildings: The ALDREN Project Experience. Sustainability 2020, 12, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waseem, M.; Adnan Khan, M.; Goudarzi, A.; Fahad, S.; Sajjad, I.A.; Siano, P. Incorporation of Blockchain Technology for Different Smart Grid Applications: Architecture, Prospects, and Challenges. Energies 2023, 16, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvalai, G.; Sesana, M.M.; Dell’Oro, P.; Brutti, D. Open Innovation for the Construction Sector: Concept Overview and Test Bed Development to Boost Energy-Efficient Solutions. Energies 2023, 16, 5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372I, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M.; Bakis, A. Sustainability in Construction Sector. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 2253–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grierson, D. Towards a sustainable built environment. CIC Start Online Innov. Rev. 2009, 1, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, C.S. Towards an integrated approach for assessing triple bottom line in the built environment. In Proceedings of the SB-LAB 2017: International Conference on Advances on Sustainable Cities and Buildings Development, Porto, Portugal, 15–17 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Abidin, N.Z. Investigating the awareness and application of sustainable construction concept by Malaysian developers. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 421–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, L.; Trindade, E.; Alencar, L.; Alencar, M.; Silvia, L. Sustainability in the construction industry: A systematic review of the literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasting, R.; Wall, M. Sustainable Solar Housing; Vol. 1—Strategies and Solutions; Earthscan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Berardi, U. Sustainability Assessment in the Construction Sector: Rating Systems and Rated Buildings. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 20, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akadiri, P.O.; Chinyio, E.A.; Olomolaiye, P.O. Design of a sustainable building: A conceptual framework for implementing sustainability in the building sector. Buildings 2012, 2, 126–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.C.; Bowen, P.A. Sustainable construction: Principles and a framework for attainment. Constr. Manag. Econ. 1997, 15, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sev, A. How can the construction industry contribute to sustainable development? A conceptual framework. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 17, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040: 2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Marjaba, G.E.; Chidiac, S.E. Sustainability and resiliency metrics for buildings—Critical review. Build. Environ. 2016, 101, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emekci, S.; Tanyer, A.M. Life Cycle Costing in Construction Sector: State of the Art Review. In Proceedings of the 5th international Project and Construction Management Conference (IPCMC2018), Girne, North Cyprus, 16–18 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, P.T.I.; Chan, E.H.W.; Chau, C.K.; Poon, C.S. A sustainable framework of “green” specification for construction in Hong Kong. J. Facil. Manag. 2011, 9, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presley, A.; Meade, L. Benchmarking for sustainability: An application to the sustainable construction industry. Benchmarking Int. J. 2010, 17, 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyegoke, A.S.; McDermott, P.; Abbot, C. Achieving sustainability in construction through the specialist task organization procurement approach. Int. J. Procure. Manag. 2009, 3, 288–313. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, Y.; Shen, L.; Yao, H. Sustainable construction practice and contractors’ competitiveness: A preliminary study. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, S.; Parrish, K. The contractor’s role in the sustainable construction industry. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Eng. Sustain. 2015, 168, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, M.; Bryde, D.; Fearon, D.; Ochieng, E. Stakeholder engagement: Achieving sustainability in the construction sector. Sustainability 2013, 5, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameh, S.H. Promoting earth architecture as a sustainable construction technique in Egypt. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 65, 362–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, J.; Kim, Y. Sustainable value on construction projects and lean construction. J. Green Build. 2008, 3, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edum-Fotwe, F.; Price, D.F. A social ontology for appraising sustainability of construction projects and developments. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2009, 27, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Directive 2002/91/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2002 on the Energy Performance of Buildings, 2002/91/EC. 2002. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A32002L0091 (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- European Commission. Amendments Adopted by the European Parliament on 14 March 2023 on the Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Energy Performance of Buildings (Recast) (COM(2021)0802—C9-0469/2021—2021/0426(COD))(1). Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2023-0068_EN.html (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- Fetting, C. The European Green Deal, ESDN Report, December 2020, ESDN Office, Vienna. Available online: https://www.esdn.eu/fileadmin/ESDN_Reports/ESDN_Report_2_2020.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- EPC Recast: Energy Performance Certificate Recast (2020–2023), Grant Agreement (GA) No: 893118. Available online: https://epc-recast.eu/ (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- EUB SuperHub: European Building Sustainability Performance and Energy Certification Hub (2021–2024), Grant Agreement (GA) No: 101033916, 2021. Quality, Usability and Visibility of Energy and Sustainability Certificates in the Real Estate Market. Available online: https://eubsuperhub.eu/assets/content/Deliverables/EUBSuperHub_D1.1.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- TIMEPAC: Towards Innovative Methods for Energy Performance Assessment and Certification of Buildings (2021–2024), Grant Agreement (GA) No: 101033819, 2022. . Deliverable 1.1 Context Analysis of EPC Generation. Available online: https://timepac.eu/reports/context-analysis-of-epc-generation/ (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- crossCert: Cross Assessment of Energy Certificates in Europe (2021–2024), Grant Agreement (GA) No: 101033778, 2022. D2.4 EPC Cross-Testing Procedure. Available online: https://www.crosscert.eu/fileadmin/user_upload/D2-4_EPC_cross-testing_procedure_v2-9.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Linkov, I.; Bridges, T.; Creutzig, F.; Decker, J.; Fox-Lent, C.; Kröger, W.; Lambert, J.H.; Levermann, A.; Montreuil, B.; Nathwani, J.; et al. Changing the resilience paradigm. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2014, 4, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Gunderson, L. Resilience and Global Sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, C.L. Should sustainability and resilience be combined or remain distinct pursuits? Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O’Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Shinozuka, M.; Tierney, K.; Wallace, W.A.; von Winterfeldt, D. A Framework to Quantitatively Assess and Enhance the Seismic Resilience of Communities. Earthq. Spectra 2003, 19, 737–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Carpenter, S.; Elmqvist, T.; Gunderson, L.; Holling, C.S.; Walker, B. Resilience and sustainable development: Building adaptive capacity in a world of transformations. AMBIO A J. Hum. Environ. 2002, 31, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, S. Assessing Resilience: Why Quantification Misses the Point; Humanitarian Policy Group: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Seismic Performance Assessment of Buildings; Vol. 1—Methodology; FEMA: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- The World Bank Group. Building Urban Resilience: Principles, Tools and Practice; Managing the Risks of Disasters in East Asia and the Pacific; The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bignami, D.F. Testing solutions of a multi-disaster building’s certification functional to the built environment sustainability and resilience. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2017, 8, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, R.A.; Nielsen, S.B.; Rode, C. Coupling and quantifying resilience and sustainability in facilities management. J. Facil. Manag. 2015, 13, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derissen, S.; Quaas, M.; Baumgärtner, S. The Relationship between Resilience and Sustainable Development of Ecological-Economic Systems. Work. Pap. Ser. Econ. 2009, 146, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.; Carpenter, S.; Anderies, J.; Abel, N.; Cumming, G.S.; Janssen, M.; Lebel, L.; Norberg, J.; Peterson, G.D.; Pritchard, R. Resilience management in social-ecological systems: A working hypothesis for a participatory approach. Conserv. Ecol. 2002, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, S.A.; Barrett, S.; Aniyar, S.; Baumol, W.; Bliss, C.; Bolin, B.; Holling, C. Resilience in natural and socioeconomic systems. Environ. Dev. Econ. 1998, 3, 221–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K.; Bolin, B.; Costanza, R.; Dasgupta, P.; Folke, C.; Holling, C.S.; Jansson, B.O.; Levin, S.; Maler, K.G.; Perrings, C.; et al. Economic Growth, Carrying Capacity, and the Environment. Ecol. Econ. 1995, 15, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrings, C. Resilience and sustainable development. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2006, 11, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, L.; Anderies, J.; Campbell, B.; Folke, C.; Hatfield-Dodds, S.; Hughes, T.; Wilson, J. Governance and the capacity to manage resilience in regional social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencturk, B.; Hossain, K.; Lahourpour, S. Life cycle sustainability assessment of RC buildings in seismic regions. Eng. Struct. 2016, 110, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lew, A.A.; Ng, P.T.; Ni, C.C.; Wu, T.C. Community sustainability and resilience: Similarities, differences and indicators. Tour. Geogr. 2016, 18, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, D.; Reynolds, E.; Bates, M.E.; Morgan, H.; Clark, S.S.; Linkov, I. Resilience and sustainability: Similarities and differences in environmental management applications. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613–614, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, E.C.; Friedland, C.J.; Orooji, F. Integrated environmental sustainability and resilience assessment model for coastal flood hazards. J. Build. Eng. 2016, 8, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, M.M.; Dhulipala, L.N.S.; Shahtaheri, Y.; Tahir, H.; Ladipo, T.; Eatherton, M.R.; Irish, J.L.; Olgun, C.G.; Reichard, G.; Rodriguez-Marek, A.; et al. Developing a Decision Framework for Multi-Hazard Design of Resilient, Sustainable Buildings. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Natural Hazards & Infrastructure, Chania, Greece, 28–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.Y.; Frangopol, D.M. Bridging the gap between sustainability and resilience of civil infrastructure using. In Routledge Handbook of Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 419–442. [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra, J.P.S.; Hasik, V.; Bilec, M.M.; Warn, G.P. Probabilistic assessment of the life-cycle environmental performance and functional life of buildings due to seismic events. J. Archit. Eng. 2018, 24, 4017035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, E.; Salman, A.M.; Li, Y. Multi-criteria decision-making for seismic resilience and sustainability assessment of diagrid buildings. Eng. Struct. 2019, 191, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi, E.; Shen, Z.; Zhou, H.; Salman, A.; Li, Y. Risk-informed multi-criteria decision framework for resilience, sustainability and energy analysis of reinforced concrete buildings. J. Build. Perform. Simul. 2020, 13, 804–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeles, K.; Patsialis, D.; Taflanidis, A.A.; Kijewski-Correa, T.L.; Buccellato, A.; Vardeman, C. Advancing the Design of Resilient and Sustainable Buildings: An Integrated Life-Cycle Analysis. J. Struct. Eng. 2021, 147, 4020341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, G.A.; Dong, Y.; Zhai, C. Performance-based probabilistic framework for seismic risk, resilience, and sustainability assessment of reinforced concrete structures. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2020, 23, 1454–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, R.; Hashempour, N.; Lotfi, M. Sustainable-resilient urban revitalization framework: Residential buildings renovation in a historic district. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 286, 124952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roostaie, S.; Nawari, N. The DEMATEL approach for integrating resilience indicators into building sustainability assessment frameworks. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.L.; You, X.Y.; Liu, H.C.; Zhang, P. DEMATEL technique: A systematic review of the state-of-the-art literature on methodologies and applications. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 2018, 3696457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, S. Integrating resilience in the multi-hazard sustainable design of buildings. Disaster Prev. Resil. 2023, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesana, M.M. Towards the development of an integrated Sustainability and Resilience Impact Assessment for industries of the construction sector. In Proceedings of the IN TRANSIZIONE, Opportunità e Sfide per l’Ambiente Costruito, Bari, Italy, 14–17 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kibert, C.J. Sustainable Construction. In Proceedings of the First International Conference of CIB TG 16, Tampa, FL, USA, 6–9 November 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Vanegas, J.A.; DuBose, J.; Pearce, A.R. Sustainable Technologies for the Building Construction Industry. In Proceedings of the Designing for the Global Environment Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 2–3 November 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdeau, L. Sustainable Development and the Future of Construction: A Comparison of Visions from Various Countries. Build. Res. Inf. 1999, 27, 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council for Research and Innovation in Building and Construction; United Nations Environment Programme International Environmental Technology Centre. Agenda 21 for Sustainable Construction in Developing Countries: A Discussion Document; CSIR Report Number; CSIR: Pretoria, South Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, O.; Castells, F.; Sonnemann, G. Sustainability in the Construction Industry: A Review of Recent Developments Based on LCA. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Tam, V.W.Y.; Tam, L.; Ji, Y. Project feasibility study: The key to successful implementation of sustainable and socially responsible construction management practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardi, U. Clarifying the new interpretations of the concept of sustainable building. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2013, 8, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, M.F.; Mateus, R.; Bragança, L. A critical analysis of building sustainability assessment methods for healthcare buildings. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2015, 17, 1381–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinks, M. Understanding and actioning BRE environmental assessment method: A socio-technical approach. Local Environ. 2015, 20, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, E. The Era of Sustainability: Promises, Pitfalls and Prospects for Sustainable Buildings and the Built Environment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.J.; Pyplacz, P.; Ermakova, M.; Konev, P. Sustainable Construction as a Competitive Advantage. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, C.S.; Chong, H.Y.; Jack, L.; Faris, A.F.M. Revisiting triple bottom line within the context of sustainable construction: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 11988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcila Novelo, R.A.; Álvarez Romero, S.O.; Corona Suárez, G.A.; Diego Morales Ramírez, J. Social sustainability in the planning, design, and construction in developing countries: Guidelines and feasibility for México. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2021, 9, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, C.; Astarini, S.D.; Rahmawati, F.; Setijanti, P.; Nurcahyo, C.B. The Influence of Green Building Application on High-Rise Building Life Cycle Cost and Valuation in Indonesia. Buildings 2022, 12, 2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. Technology Innovation for Sustainability in the Building Construction Industry: An Analysis of Patents from the Yangtze River Delta, China. Buildings 2022, 12, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickram, A.S.; Vidhya Lakshmi, S. Advancements in Environmental Management Strategies and Sustainable Practices for Construction Industry: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 10, 10–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bosher, L. Introduction: The need for built-in resilience. In Hazards and the Built Environment: Attaining Built-in Resilience, 1st ed.; Bosher, L., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Madni, A.; Jackson, S. Towards a conceptual framework for resilience engineering. IEEE Syst. J. 2009, 3, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, R.; Amaratunga, D. Introduction: Resilience in the built environment. In Post Disaster Reconstruction of the Built Environment: Rebuilding for Resilience; Amaratunga, D., Haigh, R., Eds.; Willey-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Bocchini, P.; Frangopol, D.M.; Ummenhofer, T.; Zinke, T. Resilience and Sustainability of Civil Infrastructure: Toward a Unified Approach. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2013, 20, 4014004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, B.J.; Vugrin, E.D.; Belasich, D.K. Resilience certification for commercial buildings: A study of stakeholder perspectives. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2013, 33, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, L.J.; Flanery, T.H. Designing, planning, and managing resilient cities: A conceptual framework. Cities 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- The White House. Presidential Policy Directive/PPD-21, Subject: Critical Infrastructure Security and Resilience; The White House: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Unclassified.

- Faller, G. The resilience of timber buildings. In Research and Application in Structural Engineering, Mechanics and Computation, 1st ed.; Zingoni, A., Ed.; Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sedema (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente). Programa de Acción Climática de la Ciudad de México 2014–2020; Sedema: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; McCoy, A.P.; Smoke, J. Resilient built environment: New framework for assessing the residential construction market. J. Archit. Eng. 2015, 21, B4015004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champagne, C.L.; Aktas, C. Assessing the Resilience of LEED Certified Green Buildings. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupíšek, A.; Růžička, J.; Tywoniak, J.; Hájek, P.; Volf, M. Criteria for evaluation of resilience of residential buildings in central Europe. Int. Rev. Appl. Sci. Eng. 2018, 9, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazami, A.; Carlucci, S.; Geving, S. Robust and resilient buildings: A framework for defining the protection against climate uncertainty. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 609, 72068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, E.; Oberg, A.; Coronado, C.; Andrews, C. Assessing “green” and “resilient” building features using a purposeful sys-tems approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 48, 101546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Specian, M.; Hong, T. Nexus of thermal resilience and energy efficiency in buildings: A case study of a nursing home. Build. Environ. 2020, 177, 106842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, A.; Ascione, F.; De Masi, R.F.; Pecce, M.R.; Vanoli, G.P. A Novel Contribution for Resilient Buildings. Theoretical Fragility Curves: Interaction between Energy and Structural Behavior for Reinforced Concrete Buildings. Buildings 2020, 10, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The BRE Group. Building Research Establishment Assessment Method (BREEAM). Encouraging Resilient Assets Using BREEAM; The BRE Group: Watford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Homaei, S.; Hamdy, M. Thermal resilient buildings: How to be quantified? A novel benchmarking framework and labelling metric. Build. Environ. 2021, 201, 108022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, G.; Adnan, H. A Guideline for Developing Resilient Office Buildings using Nanotechnology Applications. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1056, 12015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PRISMA Statement | Sustainability | Resilience |

|---|---|---|

| Identification | 1521 | 1015 |

| Screening | 544 | 398 |

| Eligibility | 226 | 104 |

| Inclusion | 20 | 22 |

| No. | Author/s (Year) |  | Strengths |  | Opportunities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Matthews, Friedland, Orooji (2016) [67] | Definition of a more holistic approach to flood-prone building design, considering both resilience and environmental sustainability. Inclusion of LCA to evaluate the environmental impacts of initial construction and flood damage repairs incurred over a building’s life. | Implementation of the method into a user-friendly tool for evaluating and quantifying performance-based design solutions. Increase the knowledge and awareness of the impacts and the performances of individual buildings in the urban environment. | ||

| 2 | Flint, et al. (2016) [68] | Definition of a multi-hazard decisional framework that considers the construction and operation impacts for conceptual design of resilient, sustainable building. | Possibility to integrate the multi-hazard framework into other existing performance-based and optimization methods to make a multidimensional assessment. | ||

| 3 | Yang, Frangopol (2018) [69] | Definition of a holistic probabilistic framework for multi-objective life-cycle performance optimization which considers multiple utilities such as lifetime risk, intervention actions, and lifetime resilience. | Possibility to use stochastic process theories to accelerate and make more efficient the computation. | ||

| 4 | Chhabra, Hasik, Bilec, Warn (2018) [70] | Definition of a rational probabilistic approach to measure the environmental impacts and functional lifespan of buildings exposed to repeated hazards throughout a specific design life. | Possibility to use the approach for evaluating the dispersion of damage between building elements to identify the most effective design strategies for improving the environmental performance over the whole building life by an LCA integration. | ||

| 5 | Asadi, Salman, Li (2019) [71] | Integration into a unique probabilistic decision model three well-known theories for building in seismic zone: analytic hierarchy process, multi-attribute utility theory (MAUT), and technique for order preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS). | Possibility to increase the applicability and flexibility of the framework through the integration of the Bayesian adaptive decision model. | ||

| 6 | Asadi, Shen, Zhou, Salaman, Li (2020) [72] | Development of a multi-criteria framework for building design based on a quantitative risk decision factor for the assessment of both structural and architectural building performance. | Possibility to compare different renovation solutions based on quantitive indicators considering stakeholders’ preference, and risk acceptance level by user/investor. Possibility to extend the method to other structures or infrastructure systems. | ||

| 7 | Angeles, Patsialis, Taflanidis et al. (2021) [73] | Development of a unified building design approach that integrates synergies between material choice, hazard vulnerability, and environmental impact, based on the LCA. | Possibility to improve the method by integrating the response module and providing a more accurate measurement of environmental impact data. | ||

| 8 | Anwar, Dong, Li (2021) [74] | Clearness of the methodology structure and multi-criteria (5 equal weighting factors) to assess S and R, considering seismic loss. Possibility to quantify refurbishment solutions by a systematic ranking. | Possibility to enhance and stream the ranking process. | ||

| 9 | Taherkhani, Hashempour, Lotfi (2021) [75] | Development of a framework for building renovation through urban district regeneration, integrating sustainability and resilience aspects. | Possibility to integrate age, gender, and education within the priority factors for the measurement of the residents’ tendency on S and R renovation. | ||

| 10 | Roostaie, Nawari (2022) [76] | Definition of 2 factors: sustainability enhancers and detractors based on their impact to evaluate the overall building sustainability. Dependency on the DEMATEL approach [77] to examine the integration of sustainable and resilient factors. | Possibility to incorporate the quantification of a scale score for the whole assessment framework, cluster per categories, and to validate the proposed methodology by case studies. | ||

| 11 | Bianchi (2023) [78] | Development of a practical multi-criteria method for the evaluation of safety, sustainability, and resilience of buildings subjected to seismic actions and heatwaves. | Possibility to integrate alternative hazard scenarios to analyze the cumulative effects on the service life of buildings. | ||

| 12 | Sesana (2023) [79] | Definition of a specific integrated SR method for the construction sector, based on stakeholders’ experience, needs, and barriers. | Implementation of the method with other KPIs according to the new emergent needs, certification, or market requests for the buildings. | ||

| No. | Author/s (Year) |  | Weaknesses |  | Threats |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Matthews, Friedland, Orooji (2016) [67] | Limitation of sustainability and resilience analysis to the environmental aspect only. | Lack of data evaluation on specific seismic parameters (i.e., wave loads, RSLR scenarios). | ||

| 2 | Flint et al. (2016) [68] | Limitation applicability to specific building typology (single isolated buildings). | Lack of data for the analysis of the influence on external infrastructure failure. | ||

| 3 | Yang, Frangopol (2018) [69] | Skills in Monte Carlo simulation are necessary for the use of this method to quantify the results of the overall assessment. | Limited target groups for the use and applicability of the method due to a highly skilled knowledge of the computational process. | ||

| 4 | Chhabra, Hasik, Bilec, Warn (2018) [70] | Absence of key factors for the building sustainability assessment, such as the effect of structural deterioration on building performance, and the environmental impacts. | Lack of analysis of potential uncertainty or variability during the estimation process for components and materials, as well as the selection of the most suitable unit processes from a life-cycle database. | ||

| 5 | Asadi, Salman, Li (2019) [71] | Limited and difficult data collection process due to the need for detailed data, available only through case studies collection. | Limited application of the method for the seismic assessment, due to the lack of inclusion of the fragility specification for many structural systems. | ||

| 6 | Asadi, Shen, Zhou, Salaman, Li (2020) [72] | Limited applicability to specific building typology (low- to mid-rise multi-story residential and commercial buildings). Exclusion of some data as methodology assumptions such as material and geometric properties. | Possibility of a lack of data on tall buildings or special buildings such as hospitals and schools which may limit the usability of the method in such cases. | ||

| 7 | Angeles, Patsialis, Taflanidis et al. (2021) [73] | Limited applicability to specific building typologies (not subjected to crosswind loading or vortex sheddings). | Limited applicability of the method due to a high dependency on the quantity and quality of the data. | ||

| 8 | Anwar, Dong, Li (2021) [74] | Lack of data and need to derive some data from empirical observations, stakeholders’ preferences, and/or data analytics to cover the entire analysis period. | Need to survey for collecting missing data. | ||

| 9 | Taherkhani, Hashempour, Lotfi (2021) [75] | Case-specific data collection process for economic and social aspects. | Limited applicability of the method due to its development for a specific geographical area. | ||

| 10 | Roostaie, Nawari (2022) [76] | Need to have skilled experts or professionals to conduct surveys for the methodology application. | Long duration and a large number of survey queries may cause a lack of conclusion for the data collection. | ||

| 11 | Bianchi (2023) [78] | Need to integrate a more comprehensive approach based on uncertainty for environmental and energy analyses. | Limited analyses of the effects of thermal resilience for the quantification of the impacts of heatwaves. | ||

| 12 | Sesana (2023) [79] | Need further validation for other value chains and, consequently, to slightly generalize some queries now developed for steel industries. | Need to update the section related to the pandemic to not limit the evaluation of its effects but to integrate a general risk assessment section. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sesana, M.M.; Dell’Oro, P. Sustainability and Resilience Assessment Methods: A Literature Review to Support the Decarbonization Target for the Construction Sector. Energies 2024, 17, 1440. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17061440

Sesana MM, Dell’Oro P. Sustainability and Resilience Assessment Methods: A Literature Review to Support the Decarbonization Target for the Construction Sector. Energies. 2024; 17(6):1440. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17061440

Chicago/Turabian StyleSesana, Marta Maria, and Paolo Dell’Oro. 2024. "Sustainability and Resilience Assessment Methods: A Literature Review to Support the Decarbonization Target for the Construction Sector" Energies 17, no. 6: 1440. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17061440

APA StyleSesana, M. M., & Dell’Oro, P. (2024). Sustainability and Resilience Assessment Methods: A Literature Review to Support the Decarbonization Target for the Construction Sector. Energies, 17(6), 1440. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17061440