Abstract

Over time, several relationships have been defined between electricity consumption and a region’s social and economic variables, with income as the main factor. This paper uses multiple correspondence analysis to identify the categories of dwellings and, from a graphical point of view (positioning maps), the effects of the different characteristics that influence the electricity consumption of households in rural areas of Cundinamarca, Colombia. In this analysis, the consumption of residential users responded mainly to what they can afford or acquire based on their income, consumption habits, and the characteristics of the technology. Furthermore, this study highlights the implications of these findings for policymakers and energy providers, providing valuable insights for developing targeted strategies to promote energy efficiency and sustainability in rural areas. This research contributes to a deeper understanding of the dynamics of electricity consumption and highlights the importance of tailoring energy-related interventions to the specific socio-economic context of rural communities, in this case in Cundinamarca.

1. Introduction

In several countries, understanding the intricate dynamics of energy consumption in rural households is of paramount importance, revolving around three fundamental pillars: (a) energy for cooking, an indispensable necessity for all households; (b) energy for heating, critical for basic survival; and (c) electricity for powering various household activities, including study, work, food preparation, and entertainment [1,2,3]. The behavior of electricity in rural households presents some unique characteristics and challenges that differ from those in urban households [4]. Often, the availability and reliability of electricity in these areas can be limited, which influences how residents use electricity [5]. In addition, some rural households may have limited access to modern appliances due to reliance on traditional energy sources such as firewood or charcoal, and they use more rudimentary technologies instead [2,4].

In 2022, global electricity’s share in final energy consumption remained steady at 20.4%, a three-point increase since 2010. Notable growth in electrification was seen in Asia, especially in China, while the Middle East and Latin America also experienced increases. However, regions like North America, Europe, Australia, and Africa maintained relatively stable levels of electrification [6]. Globally, households consume a significant amount of electricity, with estimated figures suggesting that the residential sector accounts for around 20% of total electricity consumption [7,8], and a third of the final electricity in the EU is consumed by households [9]. In Colombia, the residential sector represents a significant portion, approximately 20% of the country’s total energy consumption [10]. Energy-intensive refrigeration, lighting, and cooking needs mainly contribute to that figure. Households predominantly rely on electricity and fuelwood to meet these needs, which account for about 31% and 28% of the total energy market, respectively [10]. While urban areas have increasingly been adopting energy-efficient appliances, rural areas rely on traditional energy sources such as firewood, charcoal, and rudimentary tools [10]. It is worth noting, however, that each region within a country has unique dynamics in energy use and availability of energy sources, making it essential to tailor energy policies and programs to specific regional contexts.

Most research on household energy consumption focuses on the energy ladder [4,11,12,13,14,15]; this theory indicates that households tend to move from more polluting and less efficient energy sources to cleaner and more efficient energy sources as their income increases and their access to energy technologies and services improves, with electricity at the top of the ladder. Therefore, the socio-economic status of each household plays a central role in shaping these energy consumption patterns, as higher incomes often lead to increased energy access and use [2,16,17,18,19,20,21]. However, a comprehensive understanding of rural household energy behavior requires a more holistic approach considering various social variables, including housing construction characteristics and the use of electrical and electronic appliances [1,2,16,17,18,19,22,23,24,25,26,27,28]. Furthermore, it is crucial to highlight that, in order to deal with this complexity, simple approaches that allow these variables to be effectively grouped are needed. In this sense, clear and concise graphs are one of the best tools to represent and understand the relationships between these variables. These graphs simplify the visualization of complex data and make it easy to identify significant patterns and trends in the energy behavior of rural households.

This paper presents an innovative methodology to analyze and identify the factors differentiating electricity consumption patterns among households in rural Colombia. To achieve this, data obtained from the Sustainable Rural Electrification Programs (PERS, in Spanish) were used (https://sig.upme.gov.co/SIPERS/TableuResources, accessed on 28 January 2024), advanced statistical techniques, such as multiple correspondence analysis, were applied, and visual mapping techniques to provide a graphical representation of the findings were employed. The novelty lies in the simplicity and effectiveness of using the positioning map to identify relationships between multiple variables with different categories. Understanding the factors that influence household energy use in rural areas allows us to understand the energy needs of these communities, which in some cases are economically lagging behind urban areas, facilitating the planning of electrical infrastructure and the more efficient allocation of resources. It also helps to identify areas of opportunity to promote more efficient practices and technologies in the use of electrical energy in the household. This may include awareness campaigns, incentive programs for the purchase of efficient appliances, and guidance on more economical and environmentally friendly consumption habits. This case study focused on Cundinamarca, which provides a diverse and representative sample of rural energy consumption in Colombia.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 discusses the multifaceted factors associated with household energy consumption in rural areas. It also provides a detailed description of the PERS, highlighting their objectives and methodology. Section 3 presents the multiple correspondence analysis methodology and criteria used for its implementation in this study. Analysis and discussion are included in later sections, where the main findings, in the context of rural energy consumption in Cundinamarca, are presented and interpreted. Finally, the conclusions summarize this research’s critical findings, implications, and avenues for further exploration in rural energy consumption dynamics and policy formulation.

2. Review of Related Literature

Universal access to energy has emerged as a top priority in both global and local policy landscapes [5,12,29,30]. Pursuing Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) through energy use requires a deep understanding of how individuals interact with energy consumption and the multiple factors that shape their behavior in this regard [2,3,29,30].

Research has unraveled the complex dynamics of energy use and utilization of appliances with respect to household income and energy availability [9,27,28,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Economic and technical models have been enriched by incorporating social and psychological variables to improve the accuracy of energy consumption estimated figures [1,21,38]. These models include a lot of social variables that underpin decision-making processes related to energy use [21,38,39].

It is important to consider, for example, reference [40], which postulates intricate linkages between clusters of variables that include housing characteristics, socio-demographic factors, energy-related attitudes, price considerations, and feedback information on energy use. Stern’s model, as detailed in [38], integrates individual elements (such as attitude, habit, and routine) alongside contextual factors (comprising external conditions and personal capabilities) to construct a multifaceted framework. In [41], a comprehensive social–psychological model of energy use behavior is presented, which includes two sets of factors (psychological and positional) that interact in a complex manner to prompt users to make proactive choices that either facilitate or hinder their energy-related actions. At the same time, Ref. [42] notes that both micro-level factors (such as preferences, values, attitudes, and opportunities) and macro-level factors (including socio-cultural changes, technological advances, economic and demographic trends, regulations, and policies) have a substantial influence on household energy consumption.

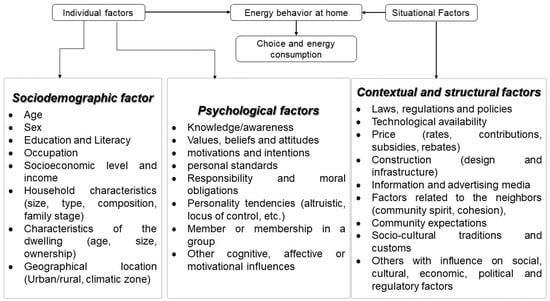

In summary, the literature vividly depicts energy consumption as the product of a complex interplay of multiple variables, including individual and situational factors (as shown in Figure 1) [39].

Figure 1.

Individual (socio-demographic and psychological) and situational (contextual and structural) factors can profoundly influence household energy choices and consumption. This model, adapted from [31], underscores the intricate web of forces at play in household energy behavior, promoting a holistic understanding of this crucial facet of sustainability and development.

However, it is important to recognize that more comprehensive approaches have been implemented primarily in developed countries and urban areas. While a three-dimensional energy profile framework has been introduced to assess energy use in rural households, it is essential to recognize that numerous factors can influence this profile through complex, linked, and reciprocal relationships [38]. This framework deliberately avoids overemphasizing income and gives equal importance to other variables, including energy availability, affordability, conversion technologies, household size, and various contextual factors.

While several papers have addressed the factors influencing household electricity consumption [1,5,19,24,43,44], it is noteworthy that very few of these studies have explicitly focused on energy consumption patterns within rural households. Considering this research gap and drawing insights from the reviewed literature, as well as data collected through the Household Energy Consumption and Use Survey conducted as part of the Sustainable Rural Electrification Programs (PERS), this study undertakes a qualitative classification of variables and characteristics, distinguishing between endogenous and exogenous factors related to household energy consumption. These distinctions are critical components of the under-development model.

To explore the explanatory variables that influence electricity consumption, we employed an inductive (ad hoc) analysis, drawing insights from selected scientific papers that examine the underlying relationships with respect to household electricity consumption [16,19,24,43,44]. It is essential to clarify that this exploratory study aims to avoid drawing quantitative conclusions about the importance of these factors. Rather, its primary objective is to conceptually illuminate the intricate inter-relationships among the explanatory variables, thus providing a qualitative framework for understanding the complex dynamics that govern household electricity consumption.

Data compiled in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, which illustrate the various interactions within households, are used to depict these qualitative relationships. This presentation helps to convey the impacts of these variables on energy consumption. It is worth emphasizing that certain variables exert influence on the characteristics of others, and in some cases, this influence is reciprocal.

Table 1.

Variables, categories, and relationships between factors for the economic characteristic [1,4,19,20,24,42,43,44,45].

Table 2.

Variables, categories, and relationships between factors for the behavioral and cultural characteristic [1,4,19,20,24,42,43,44,45].

Table 3.

Variables, categories, and relationships between factors for the non-economic characteristic [1,4,19,20,24,42,43,44,45].

Table 4.

Variables, categories, and relationships between factors for the physical environmental characteristic [1,4,19,20,24,42,43,44,45].

Table 5.

Variables, categories, and relationships between factors for the power supply characteristic [1,4,19,20,24,42,43,44,45].

Table 6.

Variables, categories, and relationships between factors for the device features characteristic [1,4,19,20,24,42,43,44,45].

It is important to note that this exploratory study does not aim to draw quantitative conclusions about the factors’ importance but to conceptually visualize the relationships between the explanatory variables. Therefore, three virtual communities were determined based on some graphs created in Gephi (Gephi.org, accessed on 26 January 2024). The higher the value, the higher the level of influence within the networks.

- Community 1—Socio-Demographic Dynamics: income (1), occupation (0.64), age (0.57), biological sex (0.43), education (0.40);

- Community 2—Economic and Housing Profile: expenditure (0.97), housing (0.83), household size (0.64), social classes (0.42);

- Community 3—Energy Use and Accessibility: number of appliances (0.86), hours of use (0.58), technology (0.58), power supply (0.39), affordability (0.25), reliability (0.24).

Over time, different types of household electricity use and behavior have been defined in terms of income. According to the energy ladder hypothesis, electricity is at the top of the energy ladder of household energy use, which mainly depends on the users’ wealth, income, and educational levels. However, households with higher levels of income, wealth, and education often use electricity only for some household activities, such as lighting, heating, and cooking. Income is the variable with the most significant preponderance, since a higher income implies a greater willingness to pay for the best fuel (electricity). It is also related to the other variables (better education, greater affordability, better housing, and more household appliances).

Although the lowest core values are those related to SDG7 (Ensure universal access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy), this subject has yet to be considered in the literature. Furthermore, household electrical appliances should not only be modeled by their electrical characteristics but also considered in the context of the provision of services and the comfort of people. Therefore, the needs of the users, what they use the appliances for, as well as other characteristics, such as if the appliances work autonomously or if they are exclusive to the home, should be included [5,25,29].

Sustainable Rural Electrification Programs—PERS

The PERS are the result of a regional and inter-institutional working scheme established in Colombia to combine efforts for the empowerment of the regions and the decentralization of knowledge with the leadership of the academy through administrative agreements of public entities such as the Mining and Energy Planning Unit (UPME in Spanish) and the Institute for Planning and Promotion of Energy Solutions for Non-Interconnected Zones (IPSE in Spanish) [46].

This strategy seeks to ensure that the formulated projects are sustainable and that energy use is a fundamental pillar for improving the productivity and development of rural communities.

The PERS take a bottom-up approach (information and individual approaches to assess general variables). Based on their results, energy needs (demand and supply) are identified to develop comprehensive and sustainable projects in the short, medium, and long term (a 15-year horizon). They also include proposals for a public energy policy that makes it possible to link energy to productivity [46].

The surveys used to develop the PERS inquire about the following four proper aspects of each region: social, economic, technological, and environmental. These, in turn, are divided into the following categories: housing characterization; public services; electricity services; willingness to pay (electricity and renewable energy); knowledge about renewable energy; use of lighting equipment, refrigeration equipment, cooking equipment, and other electrical appliances; household composition, household economics, and some health and environmental aspects.

The conducted surveys include 110 questions that were validated and adapted to the specific conditions of rural areas of Colombia over the last ten years, making them an ideal tool for knowing and analyzing the characteristics of electricity consumption in these areas. The complete survey information (in Spanish) can be consulted in the information system of the Mining–Energy Planning Unit (UPME) at https://sig.upme.gov.co/SIPERS/Uploads/CUNDINAMARCA.pdf, accessed on 26 January 2024.

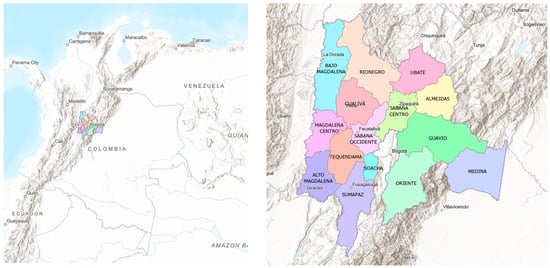

The surveys were conducted in Cundinamarca (Figure 2). It is located in the center of Colombia, in one of the six natural regions, the Andean region [47,48]. The PERS—Cundinamarca analysis was carried out between 2015 and 2016, and this included a diagnosis of the rural areas of its 15 provinces (see Figure 2); 1346 surveys were conducted in 46 municipalities [47,48]. As one of the most relevant results, 95.73% of the rural households in Cundinamarca have electricity service, and 32.9% of the households have no interruptions. Furthermore, the average consumption per user is 123.82 kWh/month, with an average cost of USD 9.93 (TRM: 1 USD = 3149 COPs) [47,48].

Figure 2.

Location of Cundinamarca and its provinces in Colombia. Adapted from [49].

For the PERS—Cundinamarca sample, the rurality index (the rurality index encompasses three key aspects: it combines demographic density with the distances from smaller to larger population centers, adopts the municipality as a whole as the unit of analysis rather than solely focusing on the size of settlements (such as the main town, populated center, and dispersed rural areas within the same municipality), and views rurality as a continuum, referring to municipalities as more or less rural rather than strictly categorizing them as urban or rural), the number of homes, and the absence of electricity in each cluster were taken into account. The selected sample took the provinces of Cundinamarca as strata and the municipalities as clusters. Rurality was assigned to select municipalities with a high rurality index compulsorily. The homes were selected to be surveyed with equiprobabilistic sampling by stratified bimetallic conglomerates [50].

In the first stage, the population was divided into 15 provinces with their corresponding conglomerates (municipalities), which constituted the primary sampling units (PSUs) and were used as the sampling frame with their respective population sizes. In each region, independent samples were randomly selected with probabilities proportional to the population sizes of the clusters (households) [50].

In the second stage, the number of surveys was selected for each of the municipalities in the residential sector, proportionally to the number of homes, the rurality index, and the number of homes without electricity in each cluster [50].

Between 2014 and 2016, PERS surveys were conducted in five departments of Colombia and 113 municipalities (Chocó: 14 municipalities, Cundinamarca: 46 municipalities, Guajira: 15 municipalities, Nariño: 22 municipalities, and Tolima: 17 municipalities).

PERS surveys did not include detailed technical information on appliance capacity but did include information on ownership and technology. The energy bill was requested for electricity consumption.

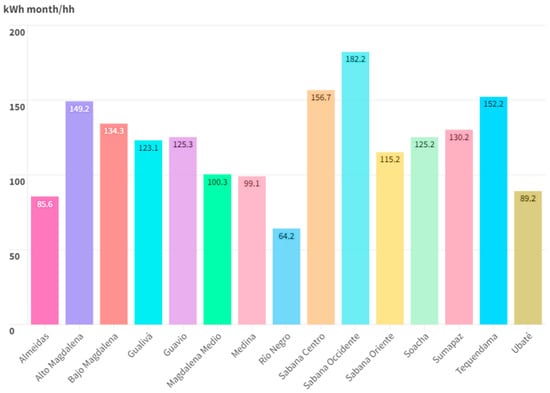

Monthly electricity consumption per household by province with PERS data provides insight into the behavior and living standards of rural households in Cundinamarca (Figure 3). This figure provides a comprehensive understanding of the energy needs and consumption patterns in different regions, reflecting the different socio-economic conditions and lifestyle choices in rural areas of each province.

Figure 3.

Monthly electricity consumption per household by province (2016).

Although the data are from 2016, a comprehensive data set that explicitly considered the variable energy consumption in each home was needed. However, this specific question was not directly included in the surveys of later DANE studies, such as the Census and the Quality-of-Life Survey. When comparing the macroeconomic variables of the municipalities to determine changes, the available data are from 2018. In addition, many of the projects and studies planned for these years were postponed due to COVID-19.

The average monthly electricity consumption in the rural residential sector of Cundinamarca was 124 kWh/month. Fluctuations in electricity consumption in rural areas are influenced by factors such as altitude, socio-economic conditions, and the geographical location of the population.

3. Data and Methodology

Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) allows the graphical representation (on a Cartesian plane) of the pattern of relationships between the categories of qualitative analyzed variables (ordinal or nominal), identifying the similarities and associations or the influence of the different variables. MCA helps to describe patterns of relationships distinctively using geometric methods by locating each variable/unit of analysis as a point in a low-dimensional space. MCA can be used to map both variables and individuals, allowing the construction of complex visual maps whose structure can be interpreted.

The heterogeneous set of analysis units must be represented on a plane where the dimensions have enough inertia to explain the variables. The first dimension explains as much variance as possible; the second dimension is orthogonal to the first and shows as much of the remaining variance as possible. The inertia is equal to the chi-square statistic (χ2) divided by the total, and it indicates how much of the variation in the original data is retained in the dimensional solution, which graphically represents the distance between the object category and its mean.

Depending on the typology of the individuals or the groups represented, the interpretation of the graphs will be through a perception of items being more or less close. Therefore, individuals with similar characteristics will appear close in space, and at the same time, each one of the characteristics will be in the space of the individuals.

In the present research, this relational analysis tool allowed us to establish correlations between the consumption of electricity and the variables of the PERS surveys, proving the existence of similar characteristics in the households studied.

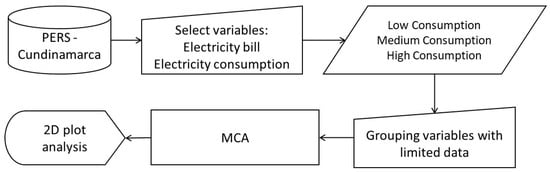

Figure 4 illustrates the procedure developed to generate location maps. Based on the PERS database for Cundinamarca (1346 surveys), data preprocessing or filtering was performed using the variable of interest, electricity consumption, obtained from billing records (708 surveys). Surveys without consumption data were excluded. The monthly electricity consumption data were then categorized into three groups: Group 1: 1–90 kWh (low consumption), Group 2: 90–180 kWh (medium consumption), and Group 3: 180–300 kWh (high consumption). These categories were then cross-referenced with over 60 variables in various analyzed location maps. Values greater than 300 kWh were omitted as they were assumed to belong to population centers beyond the scope of this research. For some variables, it was deemed beneficial to group data into ranges to ensure more representative categories.

Figure 4.

Flowchart of the multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) applied to the PERS Cundinamarca database.

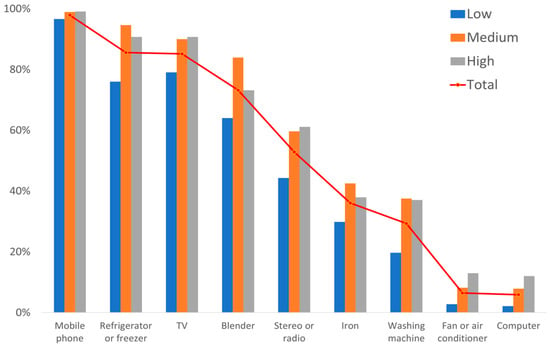

Based on the 708 surveys analyzed (taking into account only the homes that had electricity consumption information from the PERS—Cundinamarca surveys), the electrical and electronic devices with the highest participation in households were the mobile phone (97.9%), refrigerator or freezer (85.6%), TV (85.1%), blender (73.2%), stereo or radio (52.9%), iron (36.0%), washing machine (29.3%), fan or air conditioner (6.5%), and computer (5.9%). The same order can be observed when grouped by level of consumption (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Ownership of electrical appliances with regard to consumption. PERS—Cundinamarca (2016).

4. Results

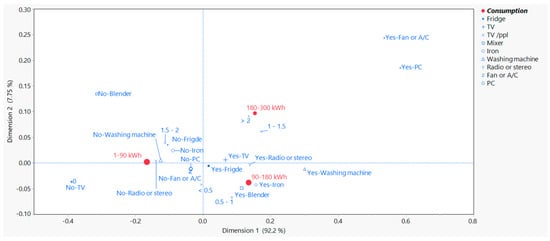

Position maps analyze the relationships between factors or categories of qualitative variables. In Figure 6, Group 1 (1–90 kWh) can be observed on the left side, where users do not own any electrical appliances. Looking at Figure 5, this conclusion regarding the ownership of household appliances cannot be observed. However, this group does have TVs (*<0.5 TVs/person and between *1.5–2 TVs/person). Households with medium consumption (Group 2) have a refrigerator, a mixer, an iron, a washing machine, and a stereo or a radio. The number of TV sets per household ranges from 0.5 to 1. Group 3 has the same characteristics as Group 2, but they have more than two TVs per household. They have computers, air conditioners or fans.

Figure 6.

Positioning map of main appliances, TV per person, and consumption.

Regarding the variable TV per person, Group 1 (low consumption) has a higher range than those with higher consumption (see Table 7). The same conclusion can be observed in Figure 6 (closeness of the values). Additionally, in Table 7, it can be observed that there is more than one TV per person in the household.

Table 7.

TVs/people.

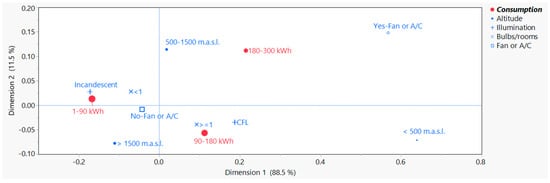

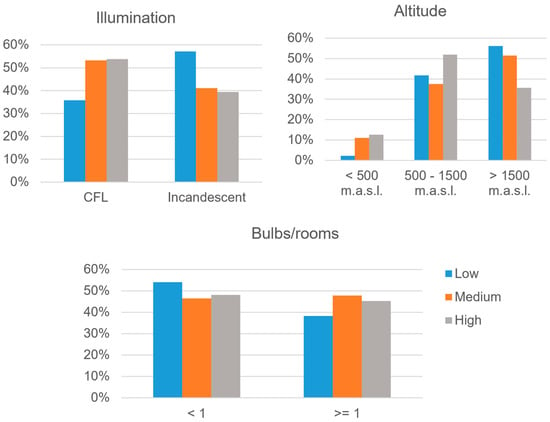

The low-consumption group has less than one light bulb per room, and the predominant technology is incandescent (Figure 7). This technology was withdrawn from the Colombian market in 2014; however, it is still being imported [51], and it is used in places above 1500 m above sea level (m.a.s.l.) to improve thermal comfort. The light bulb technology in the medium-consumption group is CFL (Compact Fluorescent Light Bulb), with at least one light bulb per room. The high-consumption group has the same characteristics as the medium-consumption group, but with more than one bulb per room. In addition, they have a fan or air conditioner when close to the variable < 500 m.a.s.l.

Figure 7.

Positioning map of altitude, illumination, bulbs/room, and consumption.

Looking at the graphs independently, it is possible to conclude that the low-consumption group is found, at higher heights, with incandescent bulbs and less than one bulb per room (see Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Altitude, illumination, bulbs/room, and consumption.

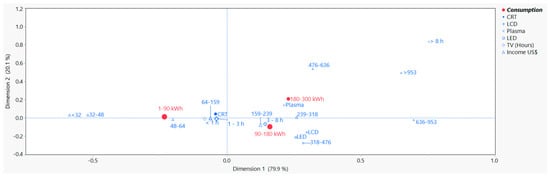

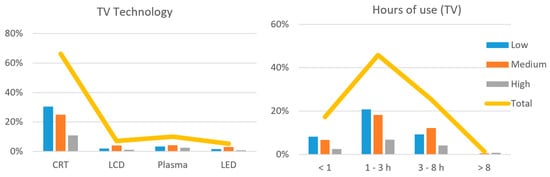

Figure 9 shows the relationships between television technology, hours of television viewing, and household income. In Group 1, CRT (Cathode-Ray Tube) technology predominates, with a daily use of up to 3 h and the lowest household income (up to USD 160 per month). In Group 2, the TV was used for from 3 to 8 h, CRT, LED, and LCD technologies predominate, and users had an average income (from USD 160 to USD 475 monthly). Group 3 is associated with a higher income (TV was used more than 8 h daily, including all TV technologies (CRT, LED, LCD, and plasma).

Figure 9.

Positioning map of TV technology, hours of use (TV), income, and consumption.

When observing the graphs independently (see Figure 10 and Table 8), it is possible to reach the same conclusion: the most significant number of televisions operate with CRT technology. For the low-usage-duration categories (“<1” and “1–3” h), older technologies such as CRT have a relatively high share. This suggests that users may prefer older technologies for sporadic or short-term use. In the extended-use categories (“3–8” and “>8” h), LCD and LED technologies dominate, with significantly higher percentages compared to CRT and plasma. This suggests that newer technologies are preferred for longer viewing sessions.

Figure 10.

TV technology, hours of use (TV), and consumption.

Table 8.

TV technology, hours of service (TV), and consumption.

Table 9 shows a clear trend of decreasing consumption levels as income increases. The percentages of households with low consumption are higher in the lower-income row labels (“<32”, “32–48”), while high consumption is more prevalent in the higher-income row labels (“>953”). In addition, the row labels corresponding to lower incomes (“<32”, “32–48”) have significantly higher percentages of households with low consumption levels. This suggests that families with lower incomes tend to have lower consumption in relative terms.

Table 9.

Income vs. consumption.

Similarly, as we move towards the middle-income row labels (“48–64”, “64–159”, “159–239”), there is a progressive increase in the percentages of households with average consumption. This suggests that middle-income families tend to have more balanced consumption levels. The row labels corresponding to higher incomes (“239–318”, “318–476”, “476–636”, “636–953”, “>953”) have significantly higher percentages of households with high consumption levels. This indicates that higher-income families tend to have relatively higher consumption levels. In the middle-income row labels (“48–64”, “64–159”, “159–239”), there is variability in the percentages of households with medium and high incomes. This suggests that there is diversity in consumption patterns at these income levels.

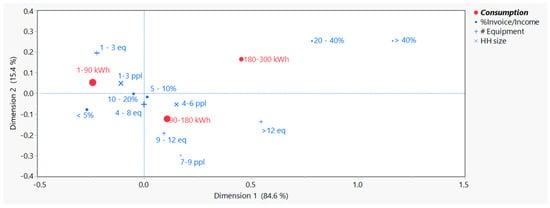

The behavior of the cost of electricity is not obvious because there are other loads, such as public lighting and subsidies, included in the bill that distort this value, so the relationship between bills and income was analyzed. We found that the higher values (20–40% and >40%) are related to Group 3. In contrast, the other values correspond to Groups 1 and 2 (see Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Positioning map of numbers of pieces of equipment, households’ size, % invoice/income, and consumption.

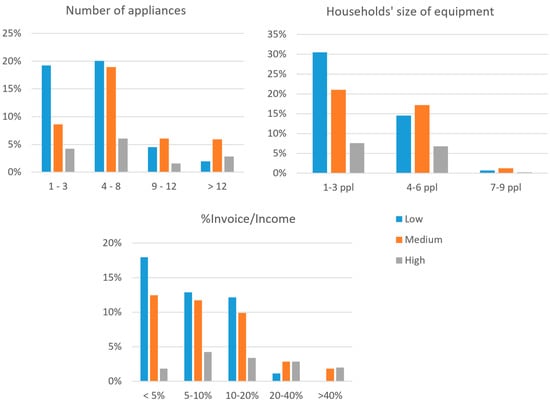

Group 1 households are families with few persons (1–3), and Group 2 is related to households with 4–6 persons and 7–9 persons. Regarding the number of electrical appliances, the smallest number of appliances (1–3) is found in Group 1 (see Figure 11).

The conclusions shown in Figure 12 are similar to those of Figure 11. According to the surveys, it is common to have between four and eight electric devices. The proportion of households with a high number of devices (>12) is considerably lower than the proportion with a moderate number of devices (4–8 and 9–12). This suggests that most households tend to have a moderate number of appliances. Households with smaller sizes (1–3 persons) have a significantly higher representation in all consumption categories. A high percentage of households spend more than 5% on electricity. This suggests that smaller households face a greater economic burden from energy expenditures.

Figure 12.

Number of appliances, households’ size, % invoice/income, and consumption.

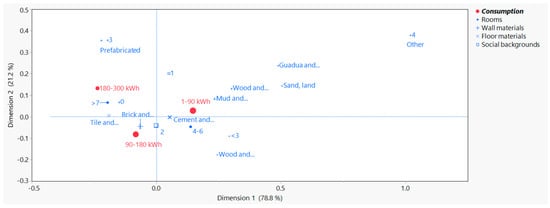

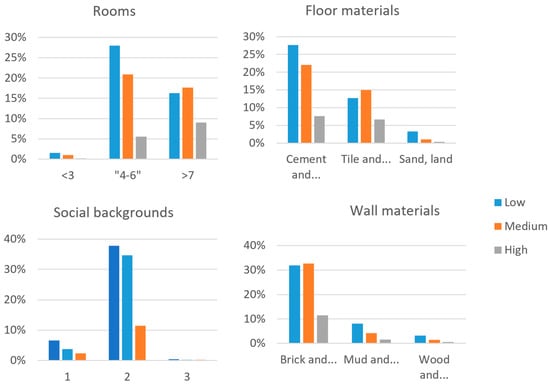

The relationship between the socio-economic level and energy consumption should be more obvious, as shown in Figure 13. A smaller number of rooms (less than three and between four and six) is related to Group 1, as well as handmade construction materials in the walls (bamboo, rush mat, other vegetables, mud, adobe, clay, rough wood plank) and floors (land, sand, cement, gravel, rough wood, board, plank).

Figure 13.

Positioning map of socio-economic level, numbers of rooms, floor and wall materials, and consumption.

Households in Groups 2 and 3 have more rooms; the walls are made of brick, block, stone, polished wood, and prefabricated materials; the floors are made of tiles and bricks (see Figure 13).

The attributes of Group 2, cement floors and brick walls, are located near the center of the map. In an MCA, the closer to the center, the less different it will be, so these attributes are not good consumption differentiators.

In Figure 14, households with 4–6 rooms have a significantly higher proportion in all consumption categories, suggesting that the house size does not influence Cundinamarca’s case. Most of the houses have cement floors and brick walls; they do not show consumption patterns according to the material. As in the previous conclusions, the most representative social background population is Group 2.

Figure 14.

Socio-economic level, number of rooms, floor and wall materials, and consumption.

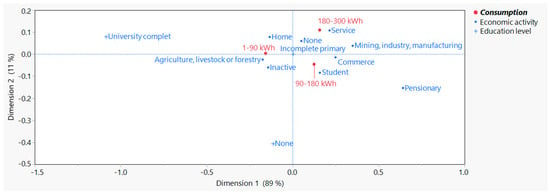

Figure 15 shows the occupations of the family members; those in Group 1 are related to households, agriculture, livestock, and forestry. Group 2 consists of students, businesspeople, and pensioners. Services, mining, industry, and manufacturing activities are related to Group 3.

Figure 15.

Positioning map of economic activity, education level, and consumption.

Figure 15 shows the higher education level of the family members, but no relationship can be established because the values of χ2 are close to 0.

Table 10 summarizes the results of the multiple correspondence analysis and compares the main characteristics of the three consumption groups.

Table 10.

Comparison of the characteristics of the three groups identified.

5. Discussion

Although several papers have analyzed the factors influencing electricity consumption at the household level, there are few cases of rural households. MCA is a technique for analyzing categorical variables that is useful when it is required to get a general understanding of how these variables are related, compare subgroups, and understand trends. An issue lies in the fact that the resulting maps can be more user-friendly if they contain fewer than five variables, as demonstrated in this instance.

The results found in this study are similar to those reported in the literature, but MCA was not mentioned.

The higher the household income, the higher the electricity consumption (Figure 8 and Figure 9, and Table 10) [16,17,18,19]. This is due to more appliances (Figure 10 and Figure 11) and the number of people in the household (Figure 10 and Figure 11). In addition, income is directly related to bill payment (Figure 10 and Figure 11), rooms (Figure 12 and Figure 13), wall and floor materials (Figure 12 and Figure 13), occupancy (Figure 14), and the use of more efficient technology (Figure 8 and Figure 9, Table 7 and Table 8) [16,17,18,19,22,23,24,43].

Generally, the higher the socio-economic level, the higher the electricity consumption in households, but in this case, this is not true.

The number of appliances and their use are influenced by household size (Figure 4 and Figure 5) and lifestyle (hours of use), which correlate with electricity consumption. The purchase of these appliances is related to income (Figure 5 and Figure 9), expenses (Figure 10 and Figure 11), and appliance characteristics (Figure 7 and Figure 9) [16,17,18,19].

The “Jevons paradox” indicates that demand can increase when a technological process increases in efficiency. In this case, there is an “environmental rebound effect” in which the introduction of more energy-efficient technologies can increase total energy consumption because instantaneous consumption decreases, but the time of use increases (Figure 7 and Table 8) [52].

The presence of household appliances does not imply electricity consumption since user consumption habits (routines) of the users and the frequency of use of the appliances must be taken into account (Figure 10).

The occupation of family members influences the time spent at home and, therefore, the use of electrical appliances, which in turn influences consumption (Figure 14).

6. Conclusions

Many studies have argued that income is one of the fundamental factors in determining household electricity consumption. However, there are other decisive factors for household electricity consumption related to income that have been studied in this paper, such as the number of appliances, educational level, and house characteristics; the literature in this area has focused on developing countries, but rural areas had not been covered yet. We address this research gap and extend the existing literature on sustainable energy development using data collected in Cundinamarca, a mainly rural area in Colombia.

The authors used a descriptive approach to analyze the collected data, and MCA was also used. Multiple correspondence analysis is a technique for analyzing categorical variables, a form of factor analysis for categorical data. It is best used when it is necessary to get a general understanding of the way in which categorical variables are related. The resulting maps are difficult to use with more than five or six variables.

In the case of Cundinamarca, the factors that influence household electricity consumption are income, household size, rooms, appliances, technology, and hours of use.

In the rural households of Cundinamarca, the most common appliances are the refrigerator and the television. However, the emerging concern about the proper use of new technologies that facilitate the social integration of communities, such as telephones, PCs, etc. is worth mentioning.

The multiple correspondence analysis identified similar characteristics of rural households in Cundinamarca, which were divided into three groups: low consumption (low income, few people in the house, few appliances, and old technology); medium consumption (average income and increased number of people, entertainment use, food preservation, and personal care devices); the high-consumption group is like the medium-consumption group, but with higher income, more appliances, and more hours of use.

Author Contributions

D.S.G.-M.: writing, original draft preparation, investigation, review, editing, conceptualization, methodology, software, and formal analysis. F.S.: analysis, writing, review, and editing. C.L.T.: analysis, writing, review, and editing. H.E.R.-C.: analysis, writing, review, and editing. W.A.R.: analysis, writing, review, and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the research group GISE3, which is part of the project “Methodology for decision-making of electrification projects in isolated rural areas, from a systemic and sustainable development approach” registered in the CIDC of the Universidad Distrital Francisco Jose de Caldas.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| CFL | Compact Fluorescent Light Bulb |

| CRT | Cathode-Ray Tube |

| DANE | Departamento administrativo nacional de estadística (National Administrative Department of Statistics) |

| HH | Households |

| IPSE | Instituto de Planificación y Promoción de Soluciones Energéticas para Zonas No Interconectadas (Institute for Planning and Promotion of Energy Solutions for Non-Interconnected Zones) |

| m.a.s.l. | Meters above sea level |

| MCA | Multiple correspondence analysis |

| PERS | Programa de Electrificacion Rural Sostenible (Sustainable Rural Electrification Programs) |

| PSU | Primary sampling unit |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| SDG7 | Sustainable Development Goal 7 (Ensure universal access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy) |

| TV/ppl | TVs/people |

| UPME | Unidad de Planeación Minero Energética (Mining and Energy Planning Unit) |

References

- Twumasi, M.A.; Jiang, Y.; Addai, B.; Asante, D.; Liu, D.; Ding, Z. Determinants of household choice of cooking energy and the effect of clean cooking energy consumption on household members’ health status: The case of rural Ghana. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 484–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherhes, V.; Alina, M. Sustainable Behavior among Romanian Students: A Perspective on Electricity Consumption in Households. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank; World Health Organization. Measuring Energy Access: A Guide to Collecting Data Using ‘The Core Questions on Household Energy Use; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, X.; Sun, H.; Yang, Z.; Yuan, W.; Ma, D. Decoupling Analysis of Rural Population Change and Rural Electricity Consumption Change in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemiński, P.; Hadyński, J.; Lira, J.; Rosa, A. Regional diversification of electricity consumption in rural areas of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 8532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Share of Electricity in Total Final Energy Consumption. Available online: https://yearbook.enerdata.net/electricity/share-electricity-final-consumption.html (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Final Consumption—Key World Energy Statistics 2021—Analysis—IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/key-world-energy-statistics-2021/final-consumption (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Distribution of Final Electricity Consumption Worldwide in 2018, by Sector. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/859150/world-electricity-consumption-share-by-sector/#:~:text= (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Proedrou, E. A Comprehensive Review of Residential Electricity Load Profile Models. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 12114–12133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UPME. Actualización Plan Energético Nacional (PEN) 2022–2052. 2023. Available online: https://www1.upme.gov.co/DemandayEficiencia/Documents/PEN_2020_2050/Actualizacion_PEN_2022-2052_VF.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Groh, S. The Role of Access to Electricity in Development Processes: Approaching Energy Poverty through Innovation. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Development and Planning, Aalborg University, Aalborg, Denmark, 2015; p. 174. [Google Scholar]

- Louie, H. Off-Grid Electrical Systems in Developing Countries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kaygusuz, K. Energy services and energy poverty for sustainable rural development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, C.; Qian, M.; Baozhong, G. The consumption patterns and determining factors of rural household energy: A case study of Henan Province in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 146, 111142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Kroon, B.; Brouwer, R.; Beukering, P. The energy ladder:Theoretical myth or empirical truth? Results from a meta-analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 20, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yohanis, Y.G. Domestic energy use and householders’ energy behaviour. Energy Policy 2012, 41, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergiades, T.; Tsoulfidis, L. Estimating Residential Demand for Electricity in the United States, 1965–2006 Revisiting Residential Demand for Electricity in Greece: New Evidence from the ARDL Approach to Cointegration; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anable, J. Energy 2050—WG1 Energy Demand Lifestyle and Energy Consumption Working Paper; UK Energy Research Center: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hayn, M.; Bertsch, V.; Fichtner, W. Electricity load profiles in Europe: The importance of household segmentation. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutumbi, U.; Thondhlana, G.; Ruwanza, S. Reported Behavioural Patterns of Electricity Use among Low-Income Households in Makhanda, South Africa. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahut, D.B.; Behera, B.; Ali, A.; Marenya, P. A ladder within a ladder: Understanding the factors influencing a household’s domestic use of electricity in four African countries. Energy Econ. 2017, 66, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVeigh, J.C.; Mordue, J.G. Energy Demand and Planning; E & FN Spon: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Alvial-Palavicino, C.; Garrido-Echeverría, N.; Jiménez-Estévez, G.; Reyes, L.; Palma-Behnke, R. A methodology for community engagement in the introduction of renewable based smart microgrid. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2011, 15, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.V.; Fuertes, A.; Lomas, K.J. The socio-economic, dwelling and appliance related factors affecting electricity consumption in domestic buildings. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 901–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lv, L.; Zhang, Z. Research on the Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Chinese Urban Households’ Electricity Consumption Efficiency. Energies 2022, 15, 7748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, R.S.; Weiss, M.; Lampis, A.; Bermann, C.; Hallack, M. La Pobreza Energética en Los Hogares y Su Relación con Otras Vulnerabilidades en América Latina: El Caso de Argentina, Brasil, Colombia, Perú y Uruguay; Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Zheng, X.; You, C.; Wei, C. Household energy consumption in rural China: Historical development, present pattern and policy implication. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari, M.; Proedrou, E.; Schäfer, B.; Beck, C.; Kantz, H.; Timme, M. Data-driven load profiles and the dynamics of residential electricity consumption. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oparaocha, S.; Ibrekk, H.O. Accelerating Sdg7 Achievement Policy Briefs in Support of the First Sdg7 Review at the Un High-Level Political Forum 2018; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018.

- Alloisio, I.; Zucca, A. SDG 7 as the enabling factor for sustainable development: The role of technology innovation in the electricity sector. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sustainable Development, New York, NY, USA, 23–24 September 2015; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Eras, J.J.C.; Fandiño, J.M.M.; Gutiérrez, A.S.; Bayona, J.G.R.; German, S.J.S. The inequality of electricity consumption in Colombia. Projections and implications. Energy 2022, 249, 123711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igawa, M.; Managi, S. Energy poverty and income inequality: An economic analysis of 37 countries. Appl. Energy 2022, 306, 118076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Bai, D.; Cong, X. Modeling the dynamic influences of economic growth and financial development on energy consumption in emerging economies: Insights from dynamic nonlinear approaches. Energy Econ. 2022, 116, 106404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A, Drivers of reported electricity service satisfaction in transition economies. Energy Policy 2017, 107, 151–157. [CrossRef]

- Nathan, H.S.K.; Hari, L. Towards a new approach in measuring energy poverty: Household level analysis of urban India. Energy Policy 2020, 140, 111397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, X.; Zhu, B.; Wang, P. Assessing global energy poverty: An integrated approach. Energy Policy 2021, 149, 112099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, R.; Walker, G.; Simcock, N. Conceptualising energy use and energy poverty using a capabilities framework. Energy Policy 2016, 93, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowsari, R.; Zerriffi, H. Three dimensional energy profile: A conceptual framework for assessing household energy use. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 7505–7517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiks, E.R.; Stenner, K.; Hobman, E.V. The socio-demographic and psychological predictors of residential energy consumption: A comprehensive review. Energies 2015, 8, 573–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Raaij, W.F.; Verhallen, T.M.M. A behavioral model of residential energy use. J. Econ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, M.; Archer, D.; Aronson, E.; Pettigrew, T. Energy Conservation Behavior. The Difficult Path From Information to Action. Am. Psychol. 1986, 41, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, W.; Steg, L.; Vlek, C.; Rothengatter, T. A review of intervention studies aimed at household energy conservation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, J.P.; Seixas, J. Unraveling electricity consumption profiles in households through clusters: Combining smart meters and door-to-door surveys. Energy Build. 2016, 116, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buys, L.; Vine, D.; Ledwich, G.; Bell, J.; Mengersen, K.; Morris, P.; Lewis, J. A framework for understanding and generating integrated solutions for residential peak energy demand. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pachauri, S.; Rao, N.; Nagai, Y.; Riahi, K. Access to Modern Energy: Assessment and Outlook for Developing and Emerging Regions; IIASA: Laxenburg, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- UPME. Inicio—PERS Cundinamarca. Available online: https://sig.upme.gov.co/SIPERS (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Rodriguez, C.L.T.; Roa, C.M.; Aldana, A.; Jacome, E. Plan de Energizacion Rural del Departamento de Cundinamarca PERS; Diagnostico Energetico del Departamento de Cundinamarca: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017; p. 96.

- Gamba, W.D. Caracterización Socioeconómica del Departamento de Cundinamarca—PERS Cundinamarca; Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas: Bogotá, Colombia, 2017.

- Provincias de Cundinamarca|Provincias de Cundinamarca|Mapas y Estadísticas de Cundinamarca. Available online: https://mapas.cundinamarca.gov.co/datasets/37c336fd508e4025ba924d759d2c2984_0/explore?location=3.606568%2C-74.008879%2C7.78 (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Perez, C.A.; Valles, C.F. UPME Documentos PERS. Available online: https://sig.upme.gov.co/SIPERS/Files/Index/1055 (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Portafolio. Colombia se Inundó de Bombillos Obsoletos en 2018|Empresas|Negocios|Portafolio. Available online: https://www.portafolio.co/negocios/empresas/colombia-se-inundo-de-bombillos-obsoletos-en-2018-528377 (accessed on 28 January 2024).

- Alcott, B. Jevons’ paradox. Ecol. Econ. 2005, 54, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).