Beyond Personal Beliefs: The Impact of the Dominant Social Paradigm on Energy Transition Choices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Energy Transition Policy in Poland

3. Theoretical Framework

4. Methods, Measures, and Materials

5. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Questionnaire

References

- UNFCCC. United Nations Framework Convention On Climate Change. United Nations, FCCC/INFORMAL/84 GE. 05-62220 (E) 200705, Secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Bonn, Germany. 24p, Available online: http://www.unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- UNFCCC. Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; Dec. 10, 2303 U.N.T.S. 162; UNFCCC: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Smil, V. How the World Really Works: A Scientist’s Guide to Our Past, Present and Future; Penguin UK: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Servigne, P.; Stevens, R. How Everything Can Collapse; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, G.R. Going Dark, 2nd ed.; Woodthrush Productions: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ecker, F.; Hahnel, U.J.J.; Spada, H. Promoting Decentralized Sustainable Energy Systems in Different Supply Scenarios: The Role of Autarky Aspiration. Front. Energy Res. 2017, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. How Long Will It Take? Conceptualizing the Temporal Dynamics of Energy Transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 13, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, O. Unintended Consequences of Renewable Energy. Problems to Be Solved; Springer: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, N.N.; Bar-Yam, Y.; Douady, R.; Norman, J.; Read, R. The Precautionary Principle: Fragility And black Swans from Policy Actions. NYU Extreme Risk Initiative Working Paper. 2014, pp. 1–24. Available online: http://www.fooledbyrandomness.com/pp2.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2016).

- Culley, M.R.; Carton, A.D.; Weaver, S.R.; Ogley-Oliver, E.; Street, J.C. Sun, Wind, Rock and Metal: Attitudes toward Renewable and Non-renewable Energy Sources in the Context of Climate Change and Current Energy Debates. Curr. Psychol. 2011, 30, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattie, D.K. U.S. energy, climate and nuclear power policy in the 21st century: The primacy of national security. Electr. J. 2020, 33, 106690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.; Narayan, R.; Rajala, A. Ideologies in Energy Transition: Community Discourses on Renewables. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2021, 11, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varey, R.J. The Marketing Future beyond the Limits of Growth. J. Macromark. 2012, 32, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickel, J. Less is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World; Random House: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bardi, U. Before the Collapse; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Micro-Foundations of the Multi-Level Perspective on Socio-Technical Transitions: Developing a Multi-Dimensional Model of Agency through Crossovers between Social Constructivism, Evolutionary Economics and Neo-Institutional Theory. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 152, 119894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.; McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A. Sustainable Consumption and the Quality of Life: A Macromarketing Challenge to the Dominant Social Paradigm. J. Macromark. 1997, 17, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.E.; Dorsch, M.J.; McDonagh, P.; Urien, B.; Prothero, A.; Grünhagen, M.; Polonsky, M.J.; Marshall, D.; Foley, J.; Bradshaw, A. The Institutional Foundations of Materialism in Western Societies: A Conceptualization and Empirical Test. J. Macromark. 2009, 29, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, A.; Thompson, C.J. Branding Disaster: Reestablishing Trust through the Ideological Containment of Systemic Risk Anxieties. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 877–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platje, J.; Will, M.; Paradowska, M.; van Dam, Y.K. Socioeconomic Paradigms and the Perception of System Risks: A Study of Attitudes towards Nuclear Power among Polish Business Students. Energies 2022, 15, 7313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, M.E.; Ghasemzadeh, F.; Hossein Rouhani, S. Energy Storage Concentrates on Solar Air Heaters with Artificial S-shaped Irregularity on the Absorber Plate. J. Energy Storage 2023, 74, 109289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayan, M.E.; Najafi, G.; Ghobadian, B.; Gorjian, S.; Mamat, R.; Ghazali, M.F. Multi-microgrid Optimization and Energy Management under Boost Voltage Converter with Markov Prediction Chain and Dynamic Decision Algorithm. Renew. Energy 2022, 201, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Program Zdrowie Rodzina Praca, Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, Warszawa. 2014. Available online: https://www.gramwzielone.pl/trendy/16998/co-pis-zrobi-z-oze-po-przejeciu-wladzy (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Program PIS. Available online: https://pis.org.pl/files/Program_PIS_2019.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Dyrekcja Generalna ds. Działań w Dziedzinie Klimatu Komisja Europejska. Neutralność Klimatyczna do 2050. Strategiczna Długoterminowa Wizja Zamożnej, Nowoczesnej, Konkurencyjnej i Neutralnej dla Klimatu Gospodarki; Urząd Publikacji Unii Europejskiej: Luxembourg, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Przedstawiciele Rządu i Związków Zawodowych Podpisali Umowę Społeczną dla Górnictwa. Available online: https://www.cire.pl/artykuly/serwis-informacyjny-cire-24/185426-przedstawiciele-rzadu-i-zwiazkow-zawodowych-podpisali-umowe-spoleczna-dla-gornictwa (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Hebda, W. Polityka Energetyczna Polski do 2040r. (Energy Policy of Poland until 2040); Ministry of Climate and Environment: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- NIK (Najwyższa Izba Kontroli). Rozwój Sektora Odnawialnych Źródeł Energii; NIK: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. Available online: https://www.nik.gov.pl/kontrole/P/17/020/ (accessed on 11 February 2023).

- Michałowska, G. UNESCO Sukcesy Porażki Wyzwania; Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- De Laurentis, C. Mediating the form and direction of regional sustainable development: The role of the state in renewable energy deployment in selected regions. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2020, 27, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USTAWA, Act of 22 June 2016 on Investments in Wind Farms, Journal of Laws 2016 Item 961 (Ustawa z Dnia 22 Czerwca 2016 r. o Zmianie Ustawy o Odnawialnych Źródłach Energii Oraz Niektórych Innych Ustaw, Dz. U. 2016 poz. 925), Prezes Rady Ministrów, Warsaw. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20160000925 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Tavakoli, A.; Saha, S.; Arif, M.T.; Haque, M.E.; Mendis, N.; Oo, A.M. Impacts of grid integration of solar PV and electric vehicle on grid stability, power quality and energy economics: A review. IET Energy Syst. Integr. 2020, 2, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USTAWA, Act of 29 October 2021 Amending the Act on Renewable Energy Sources and Certain Other Acts, Journal of Laws 2021 Item 2376. (Ustawa z Dnia 29 Października 2021 r. o Zmianie Ustawy o Odnawialnych Źródłach Energii Oraz Niektórych Innych Ustaw, Dz. U. 2021 poz. 2376), Prezes rady Ministrów, Warsaw. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20210002376 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Raport Rynek Fotowoltaiki w Polsce za Poszczególne Lata. Instytut Energetyki Odnawialnej. 2020. Available online: https://ieo.pl/en/aktualnosci/1475-rola-regionalnych-programow-operacyjnych-w-stymulowaniu-rozwoju-rynku-fotowoltaiki-w-polsce (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Aouf, R.S. Finnish “Sand Battery” Offers Solution for Renewable Energy Storage. 2022. Available online: https://www.dezeen.com/2022/07/14/finnish-sand-battery-solution-renewable-energy-storage-technology-news/ (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Chen, T.; Jin, Y.; Lv, H.; Yang, A.; Liu, M.; Chen, B.; Xie, Y.; Chen, Q. Applications of Lithium-Ion Batteries in Grid-Scale Energy Storage Systems. Trans. Tianjin Univ. 2020, 26, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mój Prąd. Available online: https://mojprad.gov.pl/ (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Archiwa Fotowoltaika. Available online: https://globenergia.pl/kategoria/fotowoltaika (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- USTAWA, Act of 20 February 2015 on Renewable Energy Sources, Journal of Laws of 2021, Item 610, 1093, 1873 and 2376 and the Act of 29 October 2021 Amending the Act on Renewable Energy Sources and Certain Other Acts, Journal of Laws 2021 Item 2376. [Ustawa z Dnia 20 Lutego 2015 r. o Odnawialnych Źródłach Energii, Dz. U. z 2021 r. poz. 610, 1093, 1873 i 2376 Oraz USTAWA z Dnia 29 Października 2021 r. o Zmianie Ustawy o Odnawialnych Źródłach Energii Oraz Niektórych Innych Ustaw, Dz. U. 2021 poz. 2376], Prezes Rady Ministrów, Warsaw. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20150000478 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Główny Urząd Nadzoru Budowlanego, Centralna Ewidencja Emisyjności Budynków. Available online: https://www.gunb.gov.pl/strona/centralna-ewidencja-emisyjnosci-budynkow (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- PSEW. Wind Energy in Poland 4.0, Report 2022, TPA Poland/Baker Tilly TPA. Available online: http://psew.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/skompresowany-raport-22Polska-energetyka-wIatrowa-4.022-2022-.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- USTAWA, Act of 19 July 2019 Amending the Act on Renewable Energy Sources and Certain Other Acts, Journal of Laws of 2019, Item 1524. [Ustawa z Dnia 19 Lipca 2019 r. o Zmianie Ustawy o Odnawialnych Źródłach Energii Oraz Niektórych Innych Ustaw, DZ. U. z 2019 r. poz. 1524], Prezes Rady Ministrów, Warsaw. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WDU20190001524 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- KOWR. Available online: https://www.kowr.gov.pl/odnawialne-zrodla-energii/spoldzielnie-energetyczne (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Powstaje Trzecia Spółdzielnia Energetyczna w Polsce. Available online: https://www.gramwzielone.pl/trendy/108211/powstaje-trzecia-spoldzielnia-energetyczna-w-polsce (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Yildiz, O.; Rommel, J.; Debor, S.; Holstenkamp, L.; Mey, F.; Muller, J.R.; Radtke, J.; Rognli, J. Renewable energy cooperatives as gatekeepers or facilitators? Recent developments in Germany and a multidisciplinary research agenda. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Saizarbitoria, I.; Saez, L.; Allur, E.; Morandeira, J. The emergence of renewable energy cooperatives in Spain: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierling, A.; Schwanitz, V.J.; Zeiß, J.P.; Bout, C.; Candelise, C.; Gilcrease, W.; Gregg, J.S. Statistical evidence on the role of energy cooperatives for the energy transition in European countries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozgul, S.; Kocar, G.; Eryasar, A. The progress, challenges, and opportunities of renewable energy cooperatives in Turkey. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2020, 59, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proka, A.; Loorbach, D.; Hisschemöller, M. Leading from the Niche: Insights from a Strategic Dialogue of Renewable Energy Cooperatives in The Netherlands. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraś, B.; Ivashchuk, O. Rola Klastrów w Zrównoważonym Rozwoju Energetyki w Polsce. Polityka Energ.-Energy Policy J. 2017, 20, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cluster Map, PARP. Available online: https://mapaklastrow.parp.gov.pl/Klastry2/index_en.html (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Polskie Sieci Elektroenergetyczne. Available online: https://www.pse.pl/dane-systemowe/funkcjonowanie-kse/raporty-dobowe-z-pracy-kse (accessed on 12 February 2023).

- Mikołajuk, H.; Zatorska, M.; Stępniak, E.; Wrońska, I. Informacja statystyczna o energii elektrycznej. Biul. Miesięczny Agencji Rynk. Energii 2021, 3, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Największe Elektrownie Fotowoltaiczne w Polsce RANKING. Available online: https://www.rynekelektryczny.pl/najwieksze-farmy-fotowoltaiczne-w-polsce/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Moc Zainstalowana Farm Wiatrowych AKTUALIZACJA. Available online: https://www.rynekelektryczny.pl/moc-zainstalowana-farm-wiatrowych-w-polsce/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Kępińska, B.; Hajto, M. Przegląd wykorzystania energii geotermalnej w polsce w latach 2022–2023. 2023. Available online: https://kongresgeotermalny.pl/viii-ogolnopolski-kongres-geotermalny/przeglad-wykorzystania-energii-geotermalnej-w-polsce-w-latach-2022-2023/ (accessed on 9 December 2023).

- Schmelzer, M.; Vetter, A.; Vansintjan, A. The Future Is Degrowth: A Guide to a World Beyond Capitalism; Verso Books: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne, W.E.; Beckmann, S.C.; Thelen, E. The role of the dominant social paradigm in environmental attitudes: A multinational examination. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourne, W.E.; Beckmann, S.C.; Lewis, A.; van Dam, Y. A Multinational Examination of the Role of the Dominant Social Paradigm in Environmental Attitudes of University Students. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. Socialism, Capitalism and Democracy; Harper and Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Nasar, S. Grand Pursuit: The Story of Economic Genius; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P.K. Sustainable Development–Economics and Policy; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Platje, J. Institutional Capital–Creating Capacity and Capabilities for Sustainable Development; Wydawnictwo Universytetu Opolskiego: Opole, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Applebaum, A. Twilight of Democracy: The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rae, C.; Bradley, F. Energy autonomy in sustainable communities–A review of key issues. Renew. Sustain. Energ. Rev. 2012, 16, 6497–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.O.; Stämpfli, A.; Dold, U.; Hammer, T. Energy autarky: A conceptual framework for sustainable regional development. Energy Policy 2011, 39, 5800–5810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.; Schönhart, M.; Biberacher, M.; Guggenberger, T.; Hausl, S.; Kalt, G.; Leduc, S.; Schardinger, I.; Schmid, E. Regional energy autarky: Potentials, costs and consequences for an Austrian region. Energy Policy 2012, 47, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, T.N.; Kennelly, J.J.; Krause, T.-S. Shifting paradigms for sustainable development: Implications for management theory and research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 874–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrensal, K.N. Critical Management Studies and American Business School Culture: Or, How Not to Get Tenure in One Easy Publication. Presented at the International Critical Management Studies Conference, Manchester, UK, 14–16 July 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrensal, K.N. Training capitalism’s foot soldiers. In The Hidden Curriculum in Higher Education; Margolis, E., Ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2001; pp. 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; COM/2019/640 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 11 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

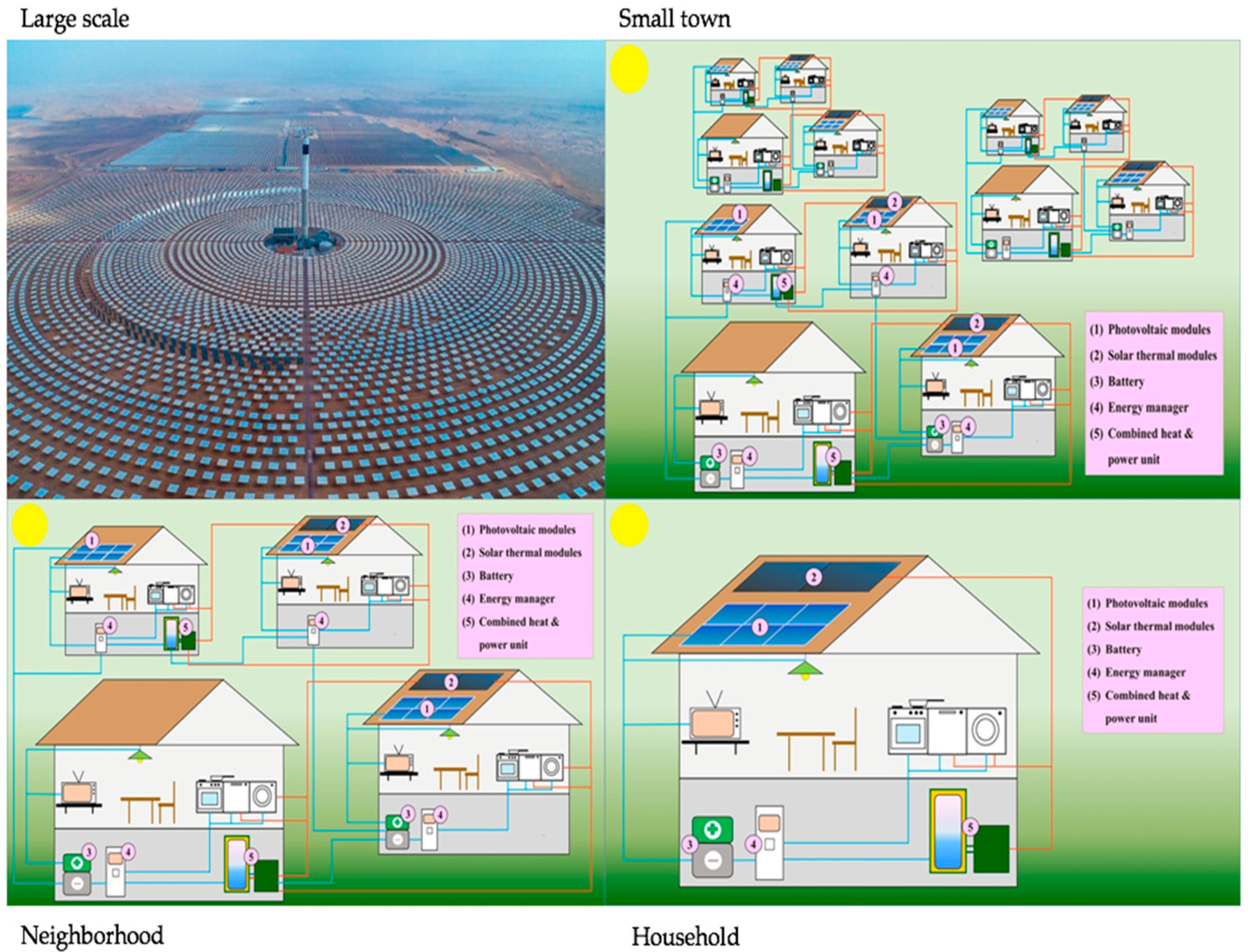

| Energy Supply Scenario | Assumed Perceptual Components |

|---|---|

| Household | Only a few people involved (family members) High sense of independence Individuals feel autonomous and self-sufficient Easy decision-making process Control of the ongoing process Energy supply is secured |

| Neighborhood | Increased number of people involved Dependencies on others Individuals feel less autonomous and self-sufficient Need for communication and interpersonal trust Decision-making is complicated Less control of the ongoing process Energy supply is secured |

| Small town | High number of people involved Dependencies on others Individuals feel less autonomous and self-sufficient Need for advanced communication collaboration Need for organized decision-making process Need for organized control process Energy supply is secured |

| Large-scale | No local governance involved Dependencies on others No autonomy and no self-sufficiency No need for advanced communication, collaboration and interpersonal trust by the end used No need for organized decision-making procedures at the local level No need for organized control process and control of the ongoing process Energy supply is secured |

| RQ1. Is There a Difference in Preference for the Energy Transition Scenarios? |

| Hypothesis 1. The large-scale energy supply scenario is the most attractive energy transition scenario. |

| Hypothesis 2. The large-scale scenario is most attractive for dealing with the impact of fossil fuel use. |

| Hypothesis 3. The preference for the energy supply scenario has an impact on (a) perceived desirability, (b) perceived autarky, (c) perceived feasibility, (d) the assessment of the impact on the environment, and (e) the perceived stability of energy supply to the individual home. |

| RQ2. Is adherence to the Dominant Social Paradigm related to the choice of the scenario for energy transition? |

| Hypothesis 4. Adherence to techno-optimism (DSPt) determines the choice of the energy supply scenario. This hypothesis is tested for (a) the attractiveness of the scenario for homeowner, (b) the attractiveness of the scenario for dealing with the impact of fossil fuel use, (c) the perceived desirability, (d) the perceived autarky, (e) the perceived feasibility, (f) the perceived impact on the environment and (g) the perceived impact of stability of energy supply to the owner’s home. |

| Hypothesis 5. Belief in free markets (DSPe) determines the choice of the energy supply scenario. This hypothesis is tested for (a) the attractiveness of the scenario for homeowner, (b) the attractiveness of the scenario for dealing with the impact of fossil fuel use, (c) the perceived desirability, (d) the perceived autarky, (e) the perceived feasibility, (f) the perceived impact on the environment and (g) the perceived impact of stability of energy supply to the owner’s home. |

| Hypothesis 6. Adherence to political liberalism (DSPp) determined the choice of the energy supply scenario. This hypothesis is tested for (a) the attractiveness of the scenario for homeowner, (b) the attractiveness of the scenario for dealing with the impact of fossil fuel use, (c) the perceived desirability, (d) the perceived autarky, (e) the perceived feasibility, (f) the perceived impact on the environment and (g) the perceived impact of stability of energy supply to the owner’s home. |

| Dimensions of the Dominant Social Paradigm | Questions | Likert Scale | Descriptive Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1.Technological dimension | 1. Advancing technology provides us with hope for the future. 2. The bad effects of technology outweigh its advantages (recoded). 3. Future resource shortages will be solved by technology. 4. Advancing technology is out of control (recoded). | 4 items. Cronbach’s α = 0.43 | M = 4.26 Sd = 0.76 |

| D2.Political dimension | 1. The average person should have more input in dealing with social problems. 2. Business interests have more political power than individuals (recoded). 3. Political equality can be attained only by major changes in election procedures. 4. Political questions are best dealt with through free market economics. | 4 items. Cronbach’s α = 0.69 | M = 4.35 Sd = 0.57 |

| D3.Economic dimension | 1. We focus too much on economic measures of well-being. (Left out of analysis in accordance with the original research [57,58]) 2. Individual behavior should be determined by economic self-interest, not politics. 3. The best measure of progress is economic. 4. If the economy continues to grow, everyone benefits. | 3 items. Cronbach’s α = 0.43 4 items. Cronbach’s α = 0.46 | M = 4.70 Sd = 0.78 M = 4.42 Sd = 0.64 |

| Dependent Variable | Scale | Question |

|---|---|---|

| a. Attractiveness for home owner | Rank from 1 (most attractive) to 4 (least attractive) | Suppose, you are the owner of a house. There are 4 options available for an energy transition in order to become independent from fossil fuels. Please rank the attractiveness of these options for yourself personally in order of attractiveness from 1 (most attractive) to 4 (least attractive). |

| b. Attractiveness for dealing with the impact of fossil fuel use | Rank from 1 (most attractive) to 4 (least attractive) | Please rank the attractiveness of all solutions for dealing with all the negative impacts of the use of fossil fuels in order of attractiveness from 1 (most attractive) to 4 (least attractive). |

| c. Perceived desirability | Rank from 1 (definitely not desirable) to 6 (completely desirable) | “How do you perceive the desirability of the described scenario?” |

| d. Perceived autarky | Rank from 1 (definitely not autarkic) to 6 (completely autarkic) | “How do you perceive the autarky of the described scenario?” |

| e. Perceived feasibility | Rank from 1 (definitely not feasible) to 6 (completely feasible) | “How do you perceive the feasibility of the described scenario?” |

| f. Impact on the environment | Rank from 1 (very negative impact) to 6 (very positive impact) | Impact of the solution on the environment. |

| g. Impact on stability of energy supply to your home | Rank from 1 (very negative impact) to 6 (very positive impact) | Impact of the solution on the stability of energy supply to your home |

| Attractive for Homeowner | Attractive for Dealing with the Impact of Fossil Fuel | |

|---|---|---|

| Large-scale | 2.20 a (1.64) | 1.87 a (1.41) |

| Small Town | 2.52 b (.095) | 2.47 b (0.80) |

| Neighborhood | 2.65 b (0.84) | 2.66 c (0.75) |

| Household | 2.63 b (1.44) | 2.99 d (1.40) |

| Perceived Desirability | Perceived Autarky (Self-Sufficiency) | Perceived Feasibility | Impact on the Environment | Impact of Stability of Energy Supply to Your Home | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large-scale | 4.40 (1.26) a | 4.05 (1.62) a | 4.08 (1.37) d | 4.13 (1.89) b | 4.28 (1.32) b |

| Small Town | 4.26 (0.92) b | 3.73 (0.73) b | 4.15 (0.97) c | 4.22 (1.08) b | 4.23 (0.81) b |

| Neighborhood | 4.13 (1.04) c | 3.70 (0.75) b | 4.31 (1.10) b | 4.29 (0.96) b | 4.19 (0.80) b |

| Household | 4.48 (1.30) a | 3.94 (1.33) a | 4.69 (1.34) a | 4.43 (1.20) a | 4.47 (0.97) a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Platje, J.; Kurek, K.A.; Berg, P.; van Ophem, J.; Styś, A.; Jankiewicz, S. Beyond Personal Beliefs: The Impact of the Dominant Social Paradigm on Energy Transition Choices. Energies 2024, 17, 1004. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17051004

Platje J, Kurek KA, Berg P, van Ophem J, Styś A, Jankiewicz S. Beyond Personal Beliefs: The Impact of the Dominant Social Paradigm on Energy Transition Choices. Energies. 2024; 17(5):1004. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17051004

Chicago/Turabian StylePlatje, Johannes, Katarzyna A. Kurek, Petra Berg, Johan van Ophem, Aniela Styś, and Sławomir Jankiewicz. 2024. "Beyond Personal Beliefs: The Impact of the Dominant Social Paradigm on Energy Transition Choices" Energies 17, no. 5: 1004. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17051004

APA StylePlatje, J., Kurek, K. A., Berg, P., van Ophem, J., Styś, A., & Jankiewicz, S. (2024). Beyond Personal Beliefs: The Impact of the Dominant Social Paradigm on Energy Transition Choices. Energies, 17(5), 1004. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17051004