Abstract

As a major component of the building envelope, the energy-saving design of exterior windows is key to energy savings in office buildings. The conventional design of exterior windows mainly focused on their impact on heating and cooling energy but ignored the indoor thermal comfort problems caused by the direct solar radiation transmitted by windows and the fluctuation of their internal surface temperatures. This study analyzed the influence of exterior windows on the indoor thermal environment of office buildings by carrying out field experiments. The experiments were carried out in a typical office building in Xi’an during December and January. The impact of exterior windows on human thermal comfort was studied from two perspectives: longwave radiation from the surface of window glass and solar shortwave radiation. It was found that solar radiation was the main cause of temperature fluctuations on the internal surface of windows and created non-uniform thermal environments. The mean radiant temperature fluctuations in the near-window area could reach up to 7.8 °C due to outdoor solar radiation in winter. Solar radiation transmitted by windows directly affects thermal sensations. Since conventional thermal comfort models or indices underestimated the thermal sensations of occupants in the presence of solar radiation, the additional thermal loads caused by solar radiation needed to be taken into account. The allowable operative temperature range for maintaining thermal comfort should be reduced by 0.5 °C when occupants are exposed to solar radiation.

1. Introduction

With economic development and accelerated urbanization, building energy consumption in China has increased rapidly during the past few decades. According to the report published by THUBERC, the current energy consumption of buildings in China has reached 1.06 billion tons of standard coal, accounting for 21% of the country’s total energy consumption. The energy consumption of office buildings, which accounts for 14% of the total building energy consumption, was one of the main reasons for the rapid increase in building energy consumption in recent years [1]. Thus, the energy-saving design of office buildings has become a matter of urgent concern. Unlike residential buildings, office buildings have a higher proportion of window area in the envelope. The impact of exterior windows on the energy consumption of office buildings is reflected in three aspects: illumination, heating, and air conditioning. In recent years, the exterior window area of office buildings has become larger, owing to various demands such as aesthetics, lighting, and psychology [2,3]. The increase in window area is beneficial for lighting energy consumption reduction, but it can lead to a significant increase in heating and air conditioning energy consumption [4,5].

The conventional energy-saving design for office building exterior windows mainly aims to reduce heat conduction by reducing the thermal conductivity of windows and to maintain the indoor air temperature within a comfortable range for the human body by reducing the energy consumption of heating and air conditioning [6,7,8]. However, approximately 50% of the body’s heat is exchanged with indoor surroundings in the form of radiation, in which exterior windows play an important part and may affect indoor thermal comfort [9]. The conventional energy-saving design of exterior windows focuses on their impact on indoor air temperature but ignores the indoor thermal comfort problems caused by the solar radiation transmitted by windows and the fluctuation in their interior surface temperatures [10,11,12].

Owing to differences in the thermophysical properties of materials, the internal surface temperature of windows is prone to large fluctuations. According to a survey conducted by Ge and Fazio in Montreal, the interior surface temperature of exterior windows was only 10 °C and 3.8 °C when outdoor temperatures were −18 °C and −32 °C, respectively [13]. Changes in the interior surface temperature of windows can have an impact on the indoor radiant temperature and thermal comfort by longwave radiation. Gan found that the asymmetric radiation temperature 1 m from a window exceeded 10 °C when the outdoor air temperature was −4 °C and the indoor air temperature was 21 °C [14]. Chaiyapinunt’s study of the indoor thermal environment of office buildings in Bangkok found that an increase in the interior surface temperature of windows can trigger an increase in the PPD value of the neighboring area, which in turn increases the risk of indoor overheating [15]. The numerical simulation analysis by Sengupta and Chapman found that only 7% of the room area in rooms with a window-to-wall ratio of 40% can meet the needs of thermal comfort in summer with solar radiation [16,17]. Too high or too low the surface temperature of the window can cause thermal discomfort and increase the operating time of air conditioners and other equipment, resulting in an increase in building energy consumption.

Shortwave radiation aroused by solar radiation through exterior windows is another important factor that triggers indoor thermal discomfort. The research by Zhao showed that the mean radiant temperature will increase by 4 °C when the solar radiation through exterior windows achieves 750 during the summer [18]. Chaiyapinunt indicated that the thermal discomfort caused by solar radiation through windows did not depend on the distance between the person and the window but on the magnitude and direction of solar radiation [19]. Arens found that when a person sitting near a window was exposed to direct solar radiation, the heat load acting on his or her body was equivalent to an increase in the average radiation temperature of the environment by 11 °C [20]. Through actual testing, Schutrum [21] figured out that on a cloudy day, the overall thermal sensation of the human body increased by 1.1 units when the window temperature increased from 3 °C to 48 °C. When sunlight directly struck the human body on a sunny day, the window temperature rose to 31.7 °C, and the overall thermal sensation of the human body increased by 2.5 units. The study by Lyons [22] further confirmed that the longwave radiation between a person and a window had the greatest impact on human thermal sensation when there was no sunlight exposure. However, when there was sunlight exposure, solar radiation became the dominant factor. Solar shortwave radiation transmission not only has an impact on the thermal comfort of the human body in the direct sunlight zone but also has a direct impact on the thermal uniformity of an entire room. Through numerical simulation analysis, Sengupta [17] found that exterior windows can lead to significant inhomogeneities in indoor thermal comfort distribution. Moreover, the heating or cooling system of an entire room cannot eliminate or improve the uneven distribution of thermal comfort. A study by Bessoudo and Tzempelikos et al. found that the internal surface temperatures of exterior windows rapidly increased and triggered asymmetric indoor radiation temperatures of up to 15 °C due to solar radiation [23,24]. Solar radiation transmitted by exterior windows will further exacerbate the inhomogeneity of the indoor thermal environment and indoor thermal discomfort and increase the intensity and duration of the use of indoor air conditioning systems, thus increasing the energy consumption of a building.

As a key component of the office building envelope, determining an appropriate thermal performance of windows, such as U-value and SHGC, would significantly reduce building energy consumption and improve indoor thermal comfort. Although the impact of exterior windows on indoor human thermal comfort has gradually attracted attention, the existing standards and specifications still use conventional human thermal comfort laws to guide indoor thermal environment design [25,26,27], which may limit the enhancement of energy-saving performance of exterior windows in office buildings and the improvement of indoor thermal environment. Established studies are mostly focused on theoretical analysis and lack on-site experimental research on occupants, particularly the thermal effect of solar radiation on occupants. Therefore, the aim of this study was to conduct on-site experiments to quantitatively analyze the impact of exterior windows on the indoor thermal environment of office buildings. The effect of exterior windows on human thermal comfort is studied from the perspectives of longwave radiation caused by the fluctuation in interior surface temperatures of windows and solar shortwave radiation caused by the direct solar radiation transmitted by windows to provide guidance and support for the energy-saving design of exterior windows in office buildings.

2. Method

To study the effect of exterior windows on the indoor thermal environment and thermal comfort, experiments were carried out in a typical office building during December and January. The experiments included two parts: (a) a questionnaire survey; and (b) a thermal environment test.

2.1. Experimental Site

The experimental site is located in a south-facing room of a typical office building in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, China. Xi’an has a temperate climate influenced by the East Asian monsoon, classified under the building thermal climate zones as situated in the cold zone (CZ) [28]. The general climate of Xi’an is characterized by cold, dry winters, hot, humid summers, and dry springs and autumns. The most intense direct solar radiation occurs in winter as the dry air tends to overheat in rooms with heating systems and large exterior windows.

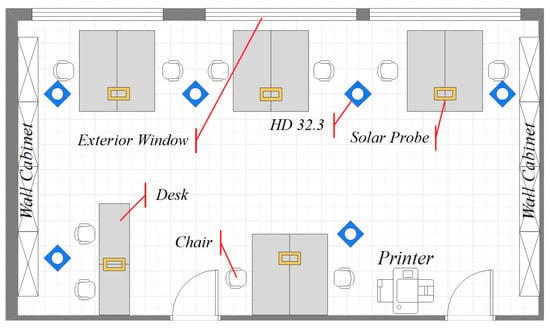

The experimental chamber plan is shown in Figure 1. The total area of the chamber was 63 m2 with a height of 2.7 m. There are three large windows on the south wall with window areas of 5.46 m2, 6.3 m2, and 6.3 m2. These windows consist of aluminum frames and double-layer glass. The window-to-wall ratio of the south wall was approximately 82%. The exterior windows were unobstructed outside. The north wall was a gypsum board partition wall, and a bookshelf on the west side of the room was backed by a gypsum partition wall. The lighting load of the chamber was 8.6 , and half of the lighting was switched on during the experiment. The heating system was set at 20 °C during the experiments.

Figure 1.

Experimental chamber plan and the arrangement of furniture and equipment.

2.2. Questionnaire Survey

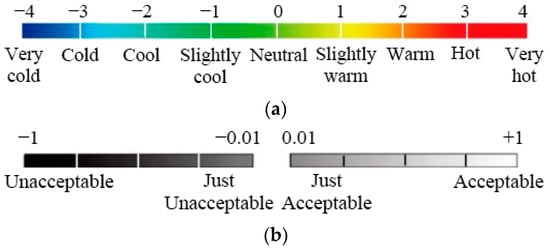

A questionnaire survey is an effective method for investigating the impact of the thermal environment on subjective thermal sensations. The questionnaire consisted of two parts: (a) basic information of personal factors, including participant’s age, activity status, and clothing; and (b) subjective thermal sensation, thermal comfort. According to ASHRAE Standard-55 [29], the thermal sensation scale is a symmetrical and bipolar seven-point scale. The seven-point scale is perfectly sufficient for general indoor thermal environment studies. However, it may not be accurate for environments containing strong solar radiation heat sources. Therefore, a nine-point scale was used in the questionnaire design, as shown in Figure 2a [30]. The acceptable scale in the questionnaire to count occupants’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction is shown in Figure 2b.

Figure 2.

The thermal sensation scale and acceptable scale applied in the questionnaire survey. (a) Nine-point thermal sensation scale in the questionnaire. (b) Acceptable scale in the questionnaire.

Subjects reported their clothing levels at the time of completing the questionnaire by means of a clothing checklist in the questionnaire. The values of clothing insulation were quantified in units of clo based on the evaluation standard for the indoor thermal environment in civil buildings (GB/T 50785) [27]. The added insulation when sitting on the chair was estimated to be 0.1 clo according to the GB/T 50785.

2.3. Subject Characteristics

A total of 33 subjects participated in the whole experiment, including 16 males and 17 females. The BMI index of the subjects was mainly concentrated between 21 and 24, which is in line with the characteristics of the general population in an office environment. The general information on these subjects can be found in Table 1. The metabolic rate was determined by the activity type of the occupant and estimated to be 1.2 met in this study, which corresponds to office activities and seated according to GB/T 50785.

Table 1.

Personal factors of the subjects in the survey.

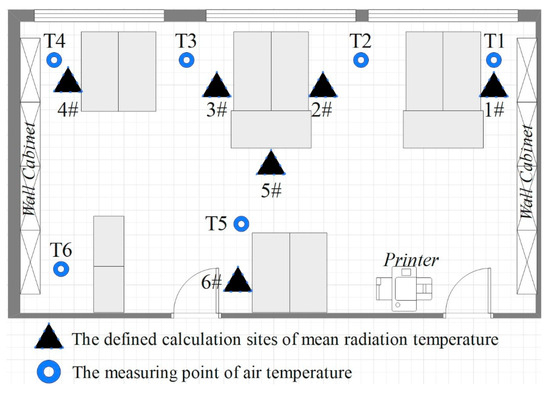

2.4. Measurement Points

The purpose of the test was to observe the direct solar radiation transmitted through the exterior windows and the variation in mean radiant temperature. The test was divided into two parts: indoor and outdoor. Indoor test items included air temperature, relative humidity, air velocity, solar radiation, and internal surface temperature of the envelope. Outdoor test items included total solar radiation, diffuse solar radiation, total solar radiation in south vertical planes, and air temperature. The arrangement of indoor equipment is shown in Figure 3. The height of equipment for air temperature, relative humidity, and air velocity was 0.6 m from the ground level. The main equipment used for testing is shown in Table 2.

Figure 3.

The defined calculation sites of mean radiant temperature and the measuring point of air temperature in the experimental chamber.

Table 2.

Equipment used in on-site experimental research.

2.5. Experimental Procedure

The seat for each subject was randomized during the experiment, and up to ten subjects could be accommodated in a single experiment due to chamber seating limitations. To eliminate the impact of previous thermal experiences, the subjects were asked to sit in an adjacent room with the same thermal environment as the experimental chamber for 30 min before the experiment to fully adapt to the current thermal environment. During the experiment, subjects remained seated and filled out the questionnaire at 30 min intervals.

2.6. Data Processing Method

2.6.1. Mean Radiant Temperature

Radiant heat transfer is the primary means by which external windows affect human thermal comfort. According to the radiation wavelength, the radiant heat transfer can be classified as longwave or shortwave. Longwave radiant heat transfer is the result of the temperature of the internal surface of an exterior window, while shortwave radiant heat transfer is the result of transmitted solar radiation.

In previous studies on human thermal comfort, the mean radiant temperature () has usually been used to measure the longwave radiant heat transfer of an entire enclosed space to the human body under the action of longwave radiation alone [31]. In this study, the mean radiant temperature was calculated from the test surface temperatures of each envelope according to the following equation:

The can be calculated according to the method used in [31]. The effect of a temperature change on the internal surface of an exterior window on thermal comfort is mainly reflected in the change of in Equation (1).

2.6.2. Solar-Adjusted Mean Radiant Temperature

The thermal effect of solar radiation on occupants is an additional heat load applied to the human body. In recent years, many scholars have proposed a variety of calculation models from different perspectives [32,33,34,35,36,37]. There are three main categories: (a) converting the transmitted solar radiation into the mean indoor radiant temperature increment [15,32,33,34,35,36], (b) directly substituting the transmitted solar radiation into the PMV calculation as the additional heat load on the human body [12,37], and (c) converting the transmitted solar radiation into an indoor air-temperature increment [38]. Based on the mechanism of the thermal effect of solar shortwave radiation on the human body, it is more reasonable to convert the transmitted solar radiation into a mean indoor radiant temperature increment. Therefore, this study calculated the thermal effect of solar shortwave radiation on the human body as an equivalent increase in the mean radiant temperature. The corrected mean radiant temperature was written as [33]:

The was taken as 0.67 in this study.

2.6.3. Data Analysis

The operative temperature is primarily used to measure the indoor thermal environmental conditions for accessing thermal comfort. The operative temperature in this study was calculated based on the following equation [31]:

In this study, there were two values for . When was the mean radiant temperature, the calculated value was the operative temperature. When was the solar-adjusted mean radiant temperature, the calculated value was the solar-adjusted operative temperature ().

The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to test the degree of linear correlation between the two sets of data and was calculated as:

3. Result Analysis

3.1. Environmental Test Results

As glass facades have an effect on solar radiation, there may be some differences in air temperatures at different locations. Table 3 compares the air temperatures of each measuring point shown in Figure 3. It can be found that the magnitude of air temperature fluctuations decreased with the increasing distance from the windows. Measuring points near the windows had higher average temperatures than those away from the windows, although the difference was small. Therefore, the following operative temperatures and PMV values of each subject were calculated according to the data measured by the nearest measuring point.

Table 3.

Summary of indoor air temperatures.

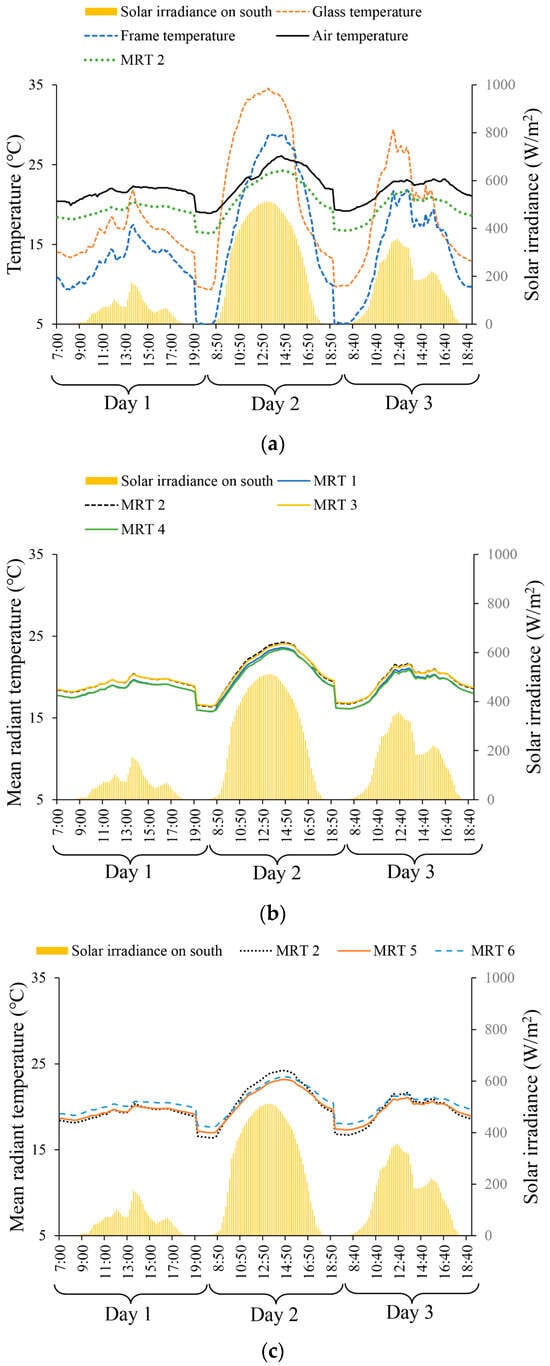

The indoor thermal environment test results for three consecutive days were analyzed, including three different outdoor working conditions: sunny, cloudy, and overcast. Day 1 was overcast, Day 2 was sunny, and Day 3 was cloudy. The analysis included the dynamic trends of the internal surface temperature of the window, the indoor air temperature, and the mean radiant temperature at different locations in the room. The results are shown in Figure 4, and the defined calculation sites of mean radiant temperature in the tested room are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Indoor thermal environment test results. (a) Comprehensive analysis result. (b) Comparative analysis result of positions in the direction of room openings. (c) Comparative analysis of positions in the direction of room depth.

As shown in Figure 4a, the outdoor solar radiation had a significant disturbance effect on the indoor thermal environment. The fluctuation amplitude of the indoor thermal environment was directly related to the outdoor solar radiation intensity during the same period. The most significant impact of outdoor solar radiation was on the temperature of the interior surface of the window glass. As the intensity of outdoor solar radiation increased, the temperature of the interior surface of the window increased rapidly up to 34.6 °C and had large temperature fluctuation. The test results of Day 2 showed that the fluctuation amplitude of the surface temperature of the window glass could reach 25.2 °C between 8:00 and 19:00. Fluctuations in the surface temperature of the window glass had a direct impact on the indoor air temperature and mean radiant temperature. According to Section 2.6.1, an increase in the surface temperature of the window glass can directly trigger an increase in the mean indoor radiant temperature. Figure 4a shows that on a clear winter day, the impact of outdoor solar radiation caused the fluctuation amplitude of the mean indoor radiation temperature near the window to reach 7.8 °C. A comparison of the analysis results under different outdoor environments shows that the higher the outdoor solar radiation intensity, the more fluctuations in the indoor thermal environment.

As demonstrated by the variation of the mean radiant temperature at different locations in the room in Figure 4b,c, a significant difference in the mean radiant temperature from the window existed at different locations. The maximum difference in average radiation temperature between Points 2 and 5 was 1.1 °C. Throughout the day, the fluctuation amplitude of the mean radiant temperature gradually weakened as the distance from the window increased. The fluctuation amplitudes of the mean radiant temperature at Points 2, 5, and 6 were 7.8 °C, 6.2 °C, and 5.8 °C, respectively. Figure 4b shows that at the same distance from the window, the mean radiant temperature in the central area of the room was more significantly affected by the surface temperature of the window than that in the areas on both sides. This was due to the larger visual coefficient between the central area and the window compared to other positions. This also indicates that for office buildings with large windows, the central area of a window is the most unfavorable area for the indoor thermal environment. As shown in Figure 4c, the mean radiant temperature generally increased with the distance from the window during Day 1. It was indicated that the glass surface temperature was mainly influenced by the outdoor air temperature on an overcast day. The lower glass temperature would lead to a lower mean radiant temperature in the vicinity of the window.

The analysis results of the indoor thermal environment suggest that the fluctuation of the window glass surface temperature was the main cause of changes in indoor mean radiant temperature. Additionally, this effect depended on the outdoor solar radiation intensity. The scope of the impact of windows on the indoor thermal environment was limited and concentrated in the near-window region. Reducing the heat-transfer coefficient of windows as well as the absorption and re-conduction of solar radiation by window glass was an effective way to weaken the impact of windows on indoor thermal comfort and to maintain indoor thermal stability. As introduced above, the conventional design of exterior windows mainly focused on their impact on heating and cooling energy. This study showed that the occupants’ thermal comfort demands should also be considered in determining the optimum heat-transfer coefficient for exterior windows in the future. Considering the non-uniform indoor thermal environment caused by windows, office buildings with large window areas should be divided into zones for air temperature regulation, or personalized tools should be used to regulate the human thermal sensation near windows. Moreover, more and more new technologies and materials, such as smart electrochromic windows, thermochromic smart windows, and aerogel glazing systems, have been applied to building windows in recent years [39,40,41]. The impact of windows on indoor thermal comfort will be weakened by the excellent capability of solar management for these new window systems.

3.2. Psychological Responses

For the analysis of thermal sensation, the data obtained during the experiment were analyzed based on the presence or absence of direct sunlight. In Section 3.2.1, the general thermal sensation of occupants only under longwave radiation caused by temperature fluctuations on the window’s inner surface is analyzed. Section 3.2.2 compares the trends in occupant thermal sensations when exposed to direct solar radiation under similar thermal environmental conditions.

3.2.1. Thermal Comfort without Direct Solar Radiation

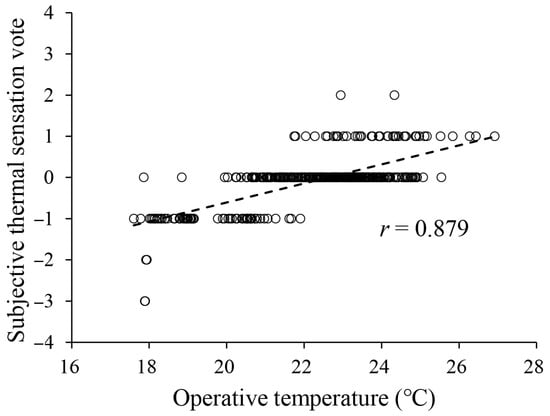

As mentioned above, the variation of indoor air and ambient radiation temperatures of office buildings are the main impacts on indoor thermal comfort. The impact of changes in the indoor thermal environment on thermal sensation can be analyzed by establishing the variation trends between subjective thermal sensations and the operative temperatures over the same period. The distribution of subjective thermal sensation under each operative temperature is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The relationship between subjective thermal sensation votes and operative temperatures.

As shown in Figure 5, with the increase in operative temperature, the subjective thermal sensation increased progressively. If the subjective thermal sensation vote (TSV) values of −1 and 1 were taken as the acceptability limits, the allowable operative temperature range is 18–25 °C. However, the upper limit of 25 °C is not credible owing to sample size limitations. If the comfort range was defined based on the neutral thermal sensation, the allowable operative temperatures should be within the range of 21–25 °C.

Although the thermal sensation vote can reflect the subjective thermal sensation in an indoor thermal environment, it cannot fully reflect occupants’ satisfaction and comfort because of differences between individuals’ thermal preferences. Previous studies have shown a good correlation between overall thermal sensation and thermal comfort in a uniform thermal environment, but a certain deviation exists between the two in non-uniform thermal environments [42]. Therefore, determining whether the indoor thermal environment induced by windows can meet the thermal comfort needs requires further analysis.

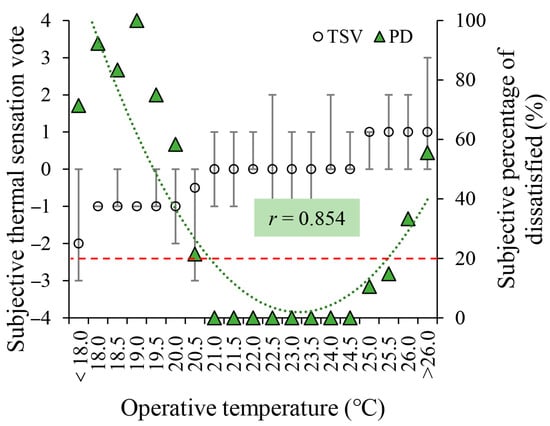

Figure 6 shows the analysis results of the range of thermal comfort thresholds in the absence of direct sunlight. The subjective percentage of dissatisfaction (PD), determined by the subjects’ reports of their thermal comfort status, increased as the operative temperature decreased or increased. An optimal operative temperature range exists that meets thermal comfort needs. According to the authors of [27], if the 80% acceptability limits were used as the threshold for the indoor thermal comfortable environment, the allowable operative temperatures should not be lower than 21.0 °C or higher than 25.5 °C. In comparison with previous studies, this temperature range is consistent with the general rule of indoor thermal comfort in non-direct sunlight environments. This confirms that the changes in indoor thermal comfort are in line with the general laws of indoor thermal environments with the longwave radiation of windows alone.

Figure 6.

Threshold of allowable operative temperatures without solar radiation.

3.2.2. Thermal Comfort under Direct Solar Radiation

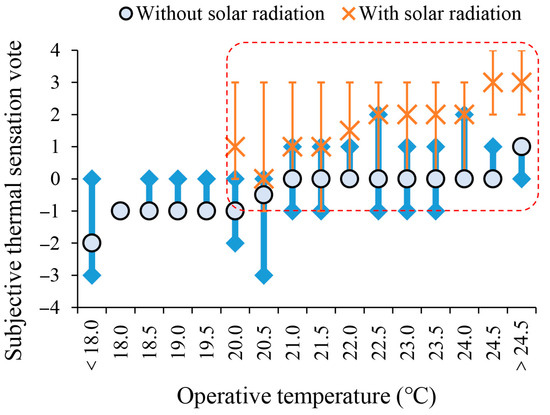

The thermal effect of direct solar radiation on the human body is to enable thermal comfort to move in the direction of partial heat. As long as it is under the influence of solar radiation, the human body will passively absorb radiation heat. When exposed to direct sunlight at the same room temperature, the human body may be more prone to overheating. The experimental data were grouped based on the presence or absence of direct sunlight and statistically analyzed the subjective thermal sensation differences between the two groups of occupants at different operative temperatures at 0.5 °C intervals, as shown in Figure 7. The calculated operative temperature was the combined value of environmental radiant temperature and air temperature from longwave radiation heat alone.

Figure 7.

Comparison of subjective thermal sensations under direct and non-direct sunlight environments.

At the same operative temperature, a deviation in the thermal sensation existed between people exposed to direct sunlight and those without direct sunlight. The degree of deviation increased with an increase in the operative temperature. When exposed to direct sunlight, the human body is more likely to experience a feeling of overheating. As shown in the red-dashed area in Figure 7, when the operative temperature was greater than 24.5 °C, the subjective thermal sensation vote values of the two experimental groups reached an overall deviation of more than 2 units.

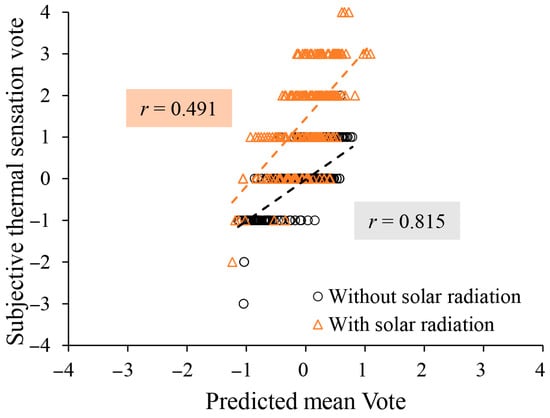

In Figure 8, the subjective thermal sensation vote (TSV) was compared with the predicted mean vote (PMV). It was indicated that the linear correlation between TSV and PMV was prominent when the occupants were not exposed to solar radiation, while the linear correlation was significantly weaker when solar radiation landed on the occupants. These orange data points were clustered in the upper left corner of the chart. It was suggested that the PMV would underestimate the thermal sensations of subjects exposed to solar radiation.

Figure 8.

The relationship between subjective thermal sensation vote (TSV) and predicted mean vote (PMV) under direct and non-direct sunlight environments.

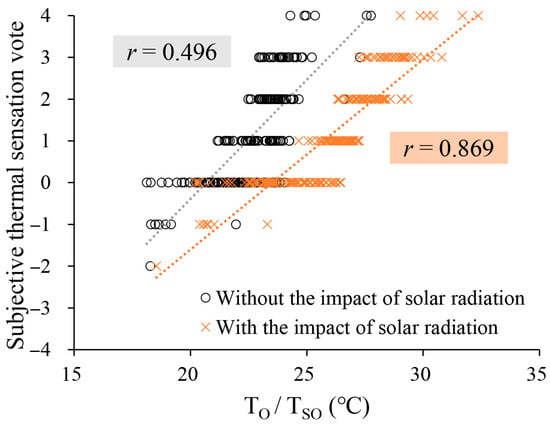

The analysis results of Figure 7 and Figure 8 both indicate that it was no longer appropriate to use the conventional indoor thermal environment indices to assess thermal sensation when the human body was exposed to direct sunlight. The operative temperature only considered the effect of longwave radiation in conventional thermal comfort indices. In response to this issue, we adopted the SMRT method to modify the conventional operative temperature and considered the additional heating load on the human body under the influence of solar radiation as described in Section 2.6.3. The solar-adjusted operative temperature was linearly refitted with the subjective thermal sensation vote value, which was compared with the linear fitting results with conventional operative temperatures shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Comparison of subjective thermal sensation polling values and linear regression results of and .

The linear correlation between operative temperatures and subjective thermal sensations was 0.496, while the solar-adjusted linear correlation between the two was 0.876. This suggests that the solar-adjusted operative temperature can better predict the thermal sensation under the effect of solar radiation. The correlation between the operative temperatures and thermal sensations showed that the conventional calculation method of the mean radiant temperature underestimated the thermal sensation with solar radiation.

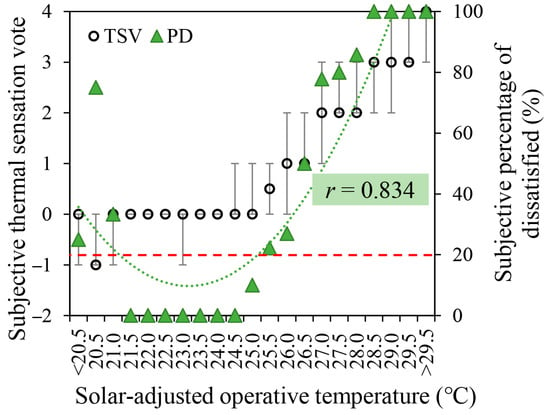

To further analyze the thermal comfort threshold of occupants under the effect of solar radiation, the solar-adjusted operative temperature was fitted to the thermal sensation as shown in Figure 10. If the 80% acceptability limits were used as the threshold for the indoor thermal comfortable environment, the solar-adjusted operative temperature should be controlled between 21.0 °C and 25.0 °C to maintain thermal comfort under the impact of solar radiation. Compared with Figure 6, the maximum operative temperature that occupants can withstand under the effect of solar radiation decreased. This suggests that when occupants are exposed to direct sunlight, lower indoor air temperatures are required to maintain a state of thermal comfort.

Figure 10.

Threshold of allowable operative temperatures with solar radiation.

4. Conclusions

The impact of exterior windows on the indoor thermal environment and thermal comfort is not only reflected in air temperature but also in the uniformity of environmental radiant temperature and thermal environment. The study of the impact of exterior windows on the indoor thermal environment and thermal comfort can help to further improve the energy-saving design of windows in office buildings. In this study, field experiments were carried out to analyze the influence of windows on the indoor thermal environment in office buildings from the perspective of temperature fluctuations on the surface of the window glass and solar radiation transmission. The following conclusions were obtained:

- Outdoor air temperature and the intensity of outdoor solar radiation have a significant effect on the temperature change of the internal surface of windows. Changes in the surface temperature of the window trigger the fluctuation of the mean indoor radiant temperature and increase the non-uniformity of the indoor thermal environment. On a clear winter day, the fluctuation in the mean radiant temperature in the indoor near-window area can reach 7.8 °C, owing to the solar radiation;

- When the human body is not directly exposed to sunlight, the thermal comfort changes follow the general law under the action of longwave radiation from the window alone. When the human body is exposed to direct sunlight, the conventional indoor thermal environment evaluation indices underestimate the thermal sensation. The mean indoor radiant temperature must be corrected and the additional heat load caused by solar shortwave radiation should be considered;

- When the human body is directly exposed to sunlight, the threshold range of operative temperature to maintain thermal comfort is reduced. In this study, the maximum operative temperature that the human body can withstand decreased by approximately 0.5 °C.

Windows play a critical role in building energy consumption and indoor thermal comfort. The outcomes of this study indicate that the design of exterior windows in office buildings should also take into account the effect of solar radiation transmission on thermal comfort, as well as the impact of temperature fluctuations on the window’s inner surfaces. For the thermal performance of windows, reducing the heat-transfer coefficient of windows, as well as the absorption and re-conduction of solar radiation by glasses, is an effective way to weaken the impact of windows on the indoor thermal environment. Further, the shading devices, including the use of Venetian blinds and sun shields, which can reduce the transmission of shortwave radiation, can alleviate the occupant’s discomfort. However, it should be noted that these measures can also lead to an increase in lighting energy consumption. These measures should balance the demand for thermal comfort and daylighting.

In terms of the design of air conditioning systems, the indoor air temperature of office buildings with large windows should be regulated in zones. For example, in the near-window area, it is necessary to reduce the supply air temperature when solar radiation reaches the occupants. Air temperature and radiant temperature both are important factors in the indoor thermal environment. Conventional practice is to control the air conditioning using temperature sensors that respond only to air temperatures. According to the results of this study, a sensor that responds to the combination of air and radiant temperatures may be more appropriate under the circumstances close to exterior windows.

In this study, potential differences between TSV experienced by males and females did not emerge, limited by the number of participants. This study focused primarily on the south façade and on the winter months when the solar radiation transmission through windows is most significant. The design of windows should balance the indoor thermal environment requirements throughout the year. In future research work, more orientation conditions should be considered and there is a need to cover different time periods, such as summer and transitional seasons, in order to provide a more comprehensive guide to the design of office building windows.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S. and L.B.; methodology, B.S.; validation, L.B. and L.Y.; investigation, B.S.; writing, B.S. and L.B.; supervision, L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52108093.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| CZ | Cold zone |

| HSCWZ | Hot summer and cold winter zone |

| PD | The subjective percentage of dissatisfaction |

| PMV | Predicted mean vote |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SHGC | Solar heat gain coefficient |

| SMRT | Solar-adjusted mean radiant temperature |

| TSV | Subjective thermal sensation vote |

| U-value | The rate of transfer of heat through matter |

| th enclosure | |

| th window | |

| The number of windows | |

| The number of enclosure surface | |

| th enclosure relative to the orientation of a human body, °C | |

| The operative temperature | |

| The mean radiant temperature | |

| The mean radiant temperature of longwave radiation, °C | |

| The solar-adjusted mean radiant temperature | |

| The solar-adjusted operative temperature | |

| The value of the ith sample in the X dataset | |

| The mean value of the X dataset | |

| The value of the ith sample in the Y dataset | |

| The mean value of the Y dataset | |

| Projected area factor | |

| The Pearson correlation coefficient | |

| Air temperature | |

| Relative absorption coefficient referring to the solar radiation | |

| Emissivity of the subject | |

| Stefan–Boltzmann constant |

References

- Building Energy Efficiency Research Center. Annual Development Research Report of China Building Energy Efficiency; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2022; pp. 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.W.; Kandar, M.Z.; Ahmad, M.H.; Ossen, D.R.; Abdullah, A.M. Building façade design for daylighting quality in typical government office building. Build. Environ. 2012, 57, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troup, L.; Phillips, R.; Eckelman, M.J.; Fannon, D. Effect of window-to-wall ratio on measured energy consumption in US office buildings. Energy Build. 2012, 203, 109434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuce, E.; Riffat, S.B. A state-of-the-art review on innovative glazing technologies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, A.R.; Rodrigues, E.; Gaspar, A.R.; Gomes, Á. A thermal performance parametric study of window type, orientation, size and shadowing effect. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 26, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasalainen, T.; Mäkinen, A.; Lehtinen, T.; Moisio, M.; Vinha, J. Architectural window design and energy efficiency: Impacts on heating, cooling and lighting needs in Finnish climates. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 27, 100996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Bae, M.J.; Kim, Y.D. Policies and status of window design for energy efficient buildings. Procedia Eng. 2016, 146, 155–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S. Progress in energy-efficiency standards for residential buildings in China. Energy Build. 2004, 36, 1191–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höppe, P.R. Indoor climate. Experientia 1993, 49, 775–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.P.; Wang, L.B.; Li, B.Q. A model of the long-wave radiation heat transfer through a glazing. Energy Build. 2013, 59, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halawa, E.; van Hoof, J.; Soebarto, V. The impacts of the thermal radiation field on thermal comfort, energy consumption and control—A critical overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 37, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Zhang, H.; You, S.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, X.; Ye, T. Study on the thermal comfort index of solar radiation conditions in winter. Build. Environ. 2020, 167, 106456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Fazio, P. Experimental investigation of cold draft induced by two different types of glazing panels in metal curtain walls. Build. Environ. 2004, 39, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, G. Analysis of mean radiant temperature and thermal comfort. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2001, 22, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiyapinunt, S.; Phueakphongsuriya, B.; Mongkornsaksit, K.; Khomporn, N. Performance rating of glass windows and glass windows with films in aspect of thermal comfort and heat transmission. Energy Build. 2005, 37, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, J.; Chapman, K.S.; Keshavarz, A. Window performance for human thermal comfort. ASHRAE Trans. 2005, 111, 254–275. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, J.; Chapman, K.S.; Keshavarz, A. Development of a methodology to quantify the impact of fenestration systems on human thermal comfort. ASHRAE Trans. 2005, 111, 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, K.; Gui, X.C.; Ge, J. Influence of solar radiation on thermal comfort in lager spaces and corresponding design of indoor paeameters. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2019, 40, 2655–2662. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiyapinunt, S.; Khamporn, N. Effect of solar radiation on human thermal comfort in a tropical climate. Indoor Built Environ. 2021, 30, 391–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens, E.; Gonzalez, R.; Berglund, L. Thermal comfort under an extended range of environmental conditions. ASHRAE Trans. 1986, 92, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schutrum, L.F.; Stewart, J.L.; Nevins, R.G. A subjective evaluation of effects of solar radiation and reradiation from windows on the thermal comfort of women. ASHRAE Trans. 1968, 74, 115–128. [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, P.; Arates, D.; Huizenga, C. Window performance for human thermal comfort. ASHRAE Trans. 1999, 73, 400–420. [Google Scholar]

- Bessoudo, M.; Tzempelikos, A.; Athienitis, A.K.; Zmeureanu, R. Indoor thermal environmental conditions near glazed facades with shading devices–Part I: Experiments and building thermal model. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 2506–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzempelikos, A.; Bessoudo, M.; Athienitis, A.K.; Zmeureanu, R. Indoor thermal environmental conditions near glazed facades with shading devices–Part II: Thermal comfort simulation and impact of glazing and shading properties. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 2517–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50189-2015; Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings. 1st ed. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015; pp. 17–18.

- GB 50736-2012; Design Code for Heating Ventilation and Air Conditioning of Civil Buildings. 1st ed. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 4–10.

- GB/T 50785-2012; Evaluation Standard for Indoor Thermal Environment in Civil Buildings. 1st ed. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012; pp. 3–15.

- Bai, L.; Song, B.; Yang, L. Developing the New Thermal Climate Zones of China for Building Energy Efficiency Using the Cluster Approach. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. 1st ed. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE): Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017; pp. 7–20.

- Pantavou, K.; Koletsis, I.; Lykoudis, S.; Melas, E.; Nikolopoulou, M.; Tsiros, I.X. Native influences on the construction of thermal sensation scales. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2020, 64, 1497–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO. Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment Instruments for Measuring Physical Quantities, 1st ed.; International Organization for Standards: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998; pp. 31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M.C.; Garg, S.N.; Jha, R. Different glazing systems and their impact on human thermal comfort—Indian scenario. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 1596–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Gennusa, M.; Nucara, A.; Rizzo, G.; Scaccianoce, G. The calculation of the mean radiant temperature of a subject exposed to the solar radiation—A generalised algorithm. Build. Environ. 2005, 40, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Gennusa, M.; Nucara, A.; Pietrafesa, M.; Rizzo, G. A model for managing and evaluating solar radiation for indoor thermal comfort. Sol. Energy 2007, 81, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, C.; Nucara, A.; Pietrafesa, M.; Polimeni, E. The effect of the short wave radiation and its reflected components on the mean radiant temperature: Modelling and preliminary experimental results. J. Build. Eng. 2017, 9, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamporn, N.; Chaiyapinunt, S. Effect of installing a venetian blind to a glass window on human thermal comfort. Build. Environ. 2014, 82, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yang, R.; You, S.; Zheng, W.; Zheng, X.; Ye, T. The CPMV index for evaluating indoor thermal comfort in buildings with solar radiation. Build. Environ. 2018, 134, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhai, Z.J. Critical review and quantitative evaluation of indoor thermal comfort indices and models incorporating solar radiation effects. Energy Build. 2020, 224, 110204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannavale, A.; Ayr, U.; Fiorito, F.; Martellotta, F. Smart electrochromic windows to enhance building energy efficiency and visual comfort. Energies 2020, 13, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Niu, J.L. Energy and visual performance of the silica aerogel glazing system in commercial buildings of Hong Kong. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 94, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, T.; Yang, R.; Tan, G.; Long, Y. Thermochromic smart windows with highly regulated radiative cooling and solar transmission. Nano Energy 2021, 89, 106440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, R. Relationship between thermal sensation and comfort in non-uniform and dynamic environments. Build. Environ. 2009, 44, 1386–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).