The Impact of the Rule of Law on Energy Policy in European Union Member States

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990’s levels.

- Enhancing energy efficiency by 32.5%.

- Elevating the share of renewable energy in the overall energy mix to 42.5%, with an ultimate target of 45%.

- Lowering primary and final energy consumption by the EU by 11.7% in comparison to the 2020 projections by 2030, translating to 40.5% and 38%, respectively, versus 2007 projections.

- Expanding interconnections to encompass at least 15% of EU electricity systems.

- Achieving net greenhouse gas emissions of zero by 2050.

- To what extent does the rule of law and the degree of adherence to it impact the realization of policies stemming from the imperative of enacting EU laws and delivering solutions that align with them, particularly within the realm of energy policy?

- How does the rule of law influence the degree to which energy policies prescribed at the EU level are effectively enacted?

- Which specific aspects of the rule of law exert the most significant influence on the efficacy of implementing EU regulations and fulfilling commitments to fellow member states in the domain of energy policy?

- Can a lower level of adherence to the rule of law in a member state contribute to setbacks or distortions in the pursuit of energy policy objectives by individual states within the broader context of the EU’s political system?

- Demonstrating the relationship between the rule of law and the level of implementation of energy policy in EU member states,

- Highlighting the key components of the rule of law in the context of the efficiency of energy policy implementation,

- Determining the level of influence of these components on the progress of implemented energy policy,

- Raising awareness of the importance of law enforcement for the coherence of the jointly adopted policy, including the interconnection of these two areas to achieve the goals set by the EU,

- Identifying countries that act as “drivers” in implementing energy policy and those acting as “spoilers” deviating from adopted commitments to a “side track”,

- Presenting selected conditions of the state of the rule of law in relation to the implementation of EU energy policy commitments.

2. Theoretical Approach

2.1. Rule of Law—Selected Aspects

- Legality—meaning a transparent, accountable, democratic, and pluralistic process of passing laws,

- Legal certainty—which requires that regulations be clear and predictable and, as a rule, cannot be amended retrospectively,

- The prohibition of arbitrariness in executive action—which requires that the interference of public authorities in the field of the private activity of an individual or legal entity has a legal basis and is justified by reasons set forth in the law,

- Independent and effective judicial review—including review of respect for fundamental rights and an independent and impartial judiciary respecting the principle of the separation of powers,

- Equality before the law—Annex I to the communication.

2.2. Energy Policy—Selected Aspects

- Diversification of European energy sources, ensuring energy security through solidarity and cooperation among EU countries;

- Ensuring the functioning of a fully integrated internal energy market, allowing the free flow of energy in the EU through appropriate infrastructure and without technical or regulatory barriers;

- Improving energy efficiency and reducing dependence on energy imports, reducing emissions, and stimulating job creation and economic growth;

- Decarbonizing the economy and transitioning to a low-carbon economy in accordance with the Paris Agreement;

- Promoting research on low-carbon and clean energy technologies and prioritizing research and innovation to stimulate the energy transition and improve competitiveness.

2.3. Rule of Law and Energy Policy—Selected Relationships and Relations

2.4. Data Sources and Transformation

| Lp | Energy Policy Factors | Label | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Contribution to renewable energy | RE | Share of energy from renewable sources in gross final consumption of energy (FEC) |

| 2 | Total gross available energy | GAE | Means the overall supply of energy for all activities in the territory of the country. This also includes energy transformation (including generating electricity from combustible fuels), distribution losses, and the use of fossil fuel products for non-energy purposes. |

| 3 | Eco-Innovation Scoreboard | EcoIS | Measures the environmental innovation performance of EU member states on the basis of the 12 indicators included in the measurement framework. |

| 4 | Pimary energy consumption | PEC | Measures the total energy demand of a country. It covers the consumption of the energy sector itself, losses during the transformation (for example, from oil or gas into electricity) and distribution of energy, and the final consumption by end users. It excludes energy carriers used for non-energy purposes. |

| 5 | Final energy consumption | FEC | Is the total energy consumed by end users, such as households, industry, and agriculture. It is the energy which reaches the final consumer’s door and excludes that which is used by the energy sector itself. |

| 6 | Effort Sharing Regulation | ESR | Binding target for greenhouse gas emission reductions compared to 2005 under the Effort Sharing Regulation. |

| 7 | Level of electricity interconnectivity | EI | Electricity interconnectivity refers to high-voltage cables connecting the electricity systems of neighboring countries. They enable excess power, such as that generated from wind and solar farms, to be traded and shared between countries. This ensures that renewable energy is not wasted and makes for a greener, more efficient power system. |

| 8 | Energy market indicator | EM | An energy market is a type of commodity market that deals with electricity, heat, and fuel products. It shows the concentration of energy production by major companies. |

- Data expressed as percentages remained unaltered and were recorded as a value after the decimal point.

- Data not expressed in percentages were normalized using the following formula:

- X′—variable after normalization,

- X—variable before normalization,

- Xmin—the minimum value of the variable X before the transformation,

- Xmax—the maximum value of the variable X before the transformation,

- Vmin—the minimum value of the variable X′ after the transformation (0.01),

- Vmax—the maximum value of the variable X′ after the transformation (0.99).

2.5. Methodological Assumptions

- O1 and O2 for indicators with values above the arithmetic average

- O3 and O4 for indicators with values below the arithmetic average

- O1 and O3 for indicators with values above the arithmetic average

- O2 and O4 for indicators with values below the arithmetic average

- Col. 1 describes variables related to the energy sector (green economy, brown economy),

- Col. 2 shows the range of values above and below average for “energy” variables,

- Col. 3 shows the EU countries classified into areas O1 and O2 and col. 5 areas O3 and O4,

- The designations of each area are included in cols. 4 and 6 on the corresponding lines,

- The headlines of cols. 3–6 record the calculated arithmetic averages for each rule-of-law-related variable.

- In Phase I, EU countries were ranked, in absolute terms, according to the number of occurrences within the O1 area (col. 2 in Tables 3a, 5a, 7a, 9a, 11a, 13a, 15a, 17a, 19a, 21a in the Data Repository [75]),

- In Stage II, EU countries were ranked according to the number of occurrences within the O2 area, but taking into account the results of the ranking from Stage I (col. 3 in Tables 3a, 5a, 7a, 9a, 11a, 13a, 15a, 17a, 19a, and 21a in the Data Repository [75]),

- In Stage III, EU countries were ranked according to the number of occurrences within the O3 area, but taking into account the results of the ranking from Stages I and II (col. 4 in Tables 3a, 5a, 7a, 9a, 11a, 13a, 15a, 17a, 19a, and 21a in the Data Repository [75]),

- In Stage IV, EU countries were ranked according to the number of occurrences within the O4 area, but taking into account the results of the ranking from Stages I, I, and III (col. 5 in Tables 3a, 5a, 7a, 9a, 11a, 13a, 15a, 17a, 19a, and 21a in the Data Repository [75]).

- In Phase I, EU countries were ranked by incidence within the O1 area for incidences greater than or equal to 4 (col. 2 in Tables 3b, 5b, 7b, 9b, 11b, 13b, 15b, 17b, 19b, 21b in the Data Repository [75]),

- In Stage II, the remaining EU countries were ranked by incidence within the O2 area for counts greater than or equal to 4 (col. 3 in Tables 3b, 5b, 7b, 9b, 11b, 13b, 15b, 17b, 19b, 21b in the Data Repository [75]),

- In Stage III, the remaining EU countries were ranked by incidence within the O3 area for incidences greater than or equal to 4 (col. 4 in Tables 3b, 5b, 7b, 9b, 11b, 13b, 15b, 17b, 19b, 21b in the Data Repository [75])

- In Stage IV, the remaining EU countries were ranked by incidence within the O4 area for incidences greater than or equal to 4 (col. 5 in Tables 3b, 5b, 7b, 9b, 11b, 13b, 15b, 17b, 19b, 21b in the Data Repository [75]).

3. Research Results

3.1. Introduction

3.2. Analysis Results

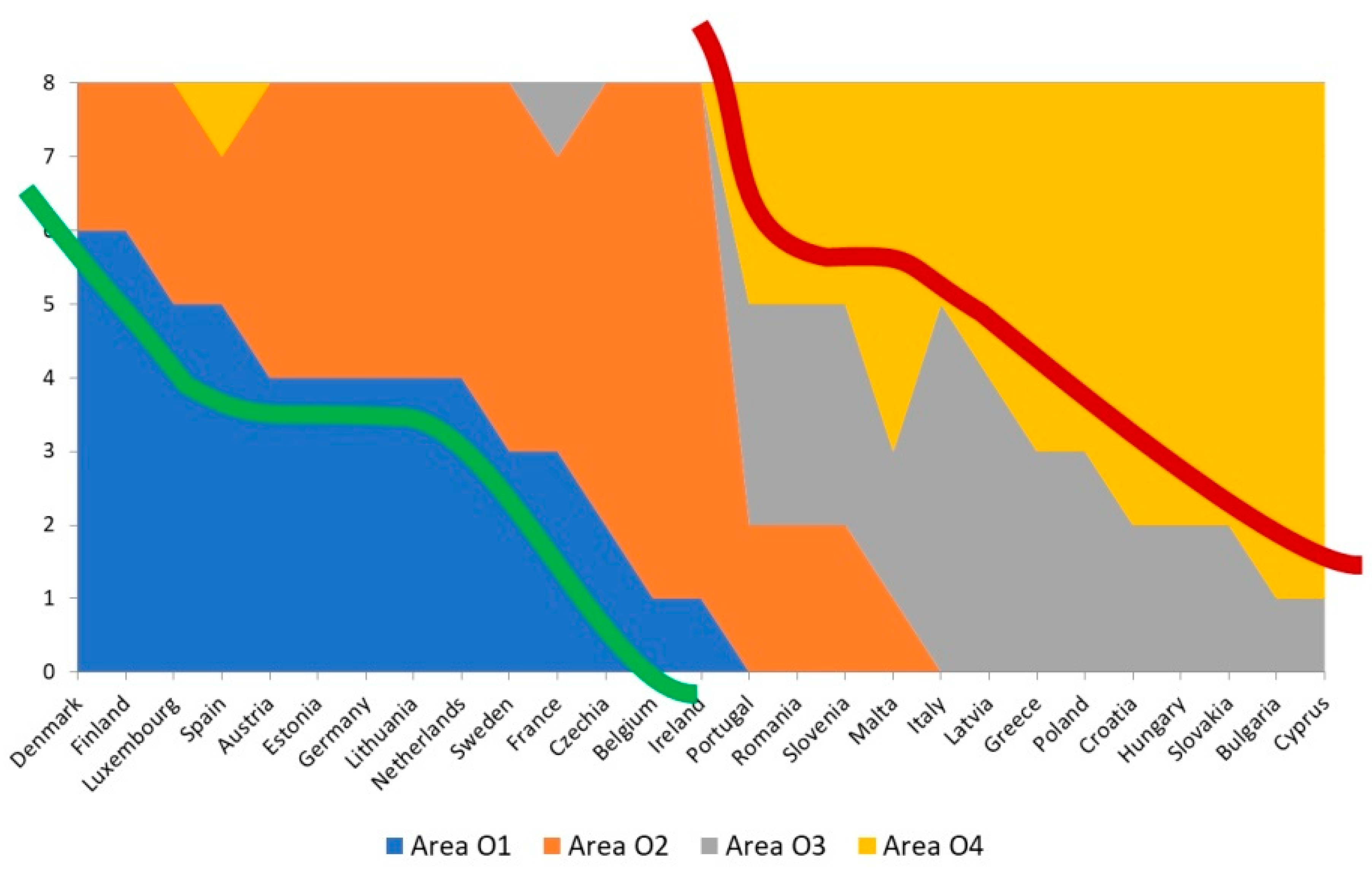

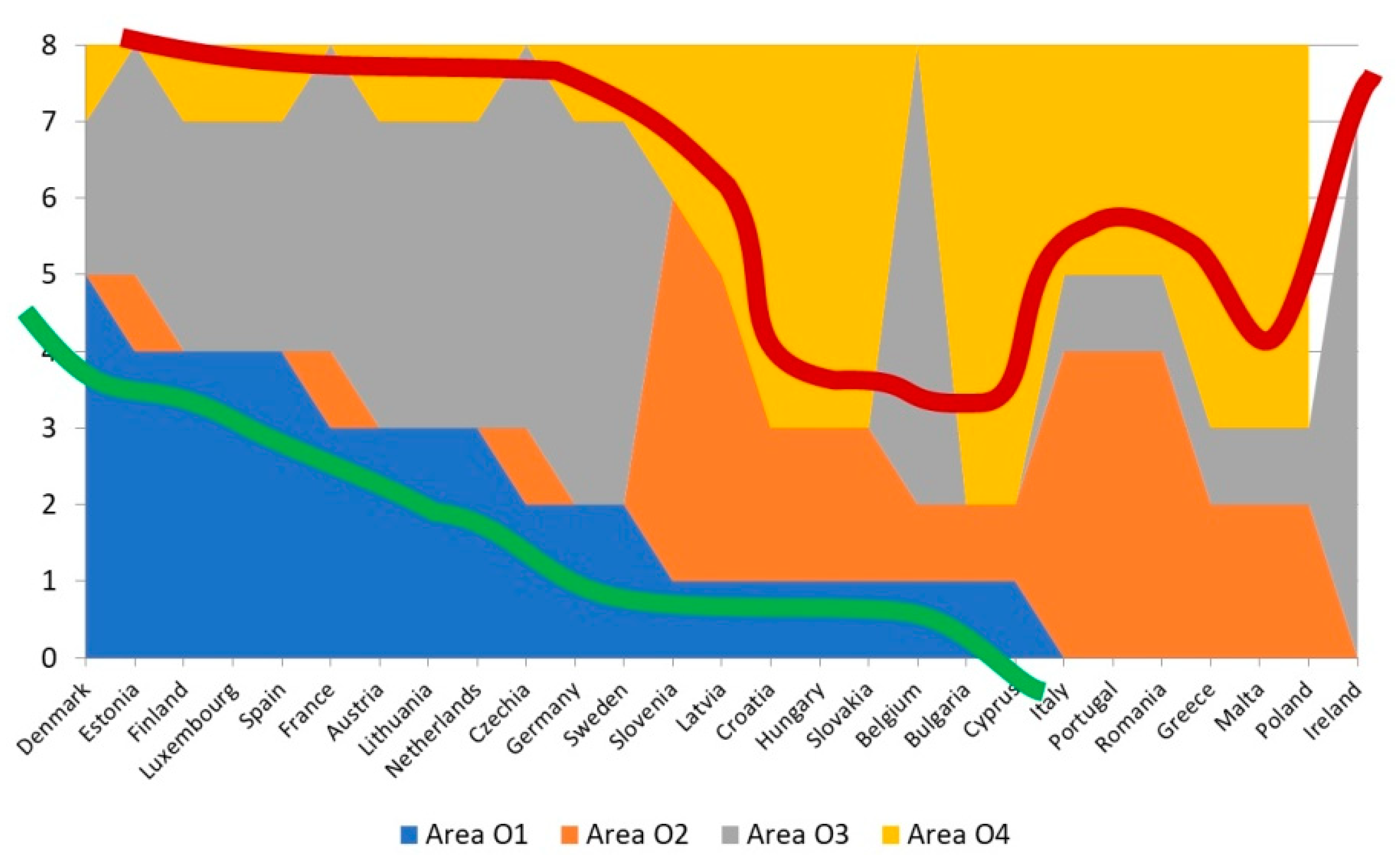

3.2.1. Rule of Law Index—Overall Score (Data from Table 3a,b in the Data Repository [75])

- Excelling in both the rule of law and the responsible implementation of energy policies including green economy elements are Denmark, Finland, Luxembourg, Spain, Austria, Estonia, Germany, Lithuania, and the Netherlands.

- Performing well in the rule of law and demonstrating a responsible approach to energy policies, including green economy elements, are Sweden, France, Czechia, Belgium, and Ireland.

- Struggling in terms of the rule of law and showing limited progress in energy policy, including green economy elements are Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Malta, and Italy.

- Experiencing significant challenges in the rule of law and displaying limited advancement in energy policy including green economy elements are Latvia, Greece, Poland, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Cyprus.

- The countries excelling in both the rule of law and green economy policies are Denmark, Finland, Luxembourg, and Spain.

- The countries demonstrating a strong commitment to the rule of law but with some ambiguity in their approach to green economy policies include Austria, Estonia, Germany, Lithuania, and the Netherlands. France is ambiguously implementing brown economy policies.

- The countries with a strong adherence to the rule of law but pursuing brown economy policies are Ireland, Belgium, Czechia, and Sweden.

- Italy exhibits an issue with the rule of law (below average) while actively implementing green economy policies.

- Latvia faces challenges with the rule of law and lacks a clearly defined energy policy.

- Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, Malta, Greece, Poland, Romania, and Slovenia experience significant difficulties with the rule of law and are actively pursuing brown economy policies.

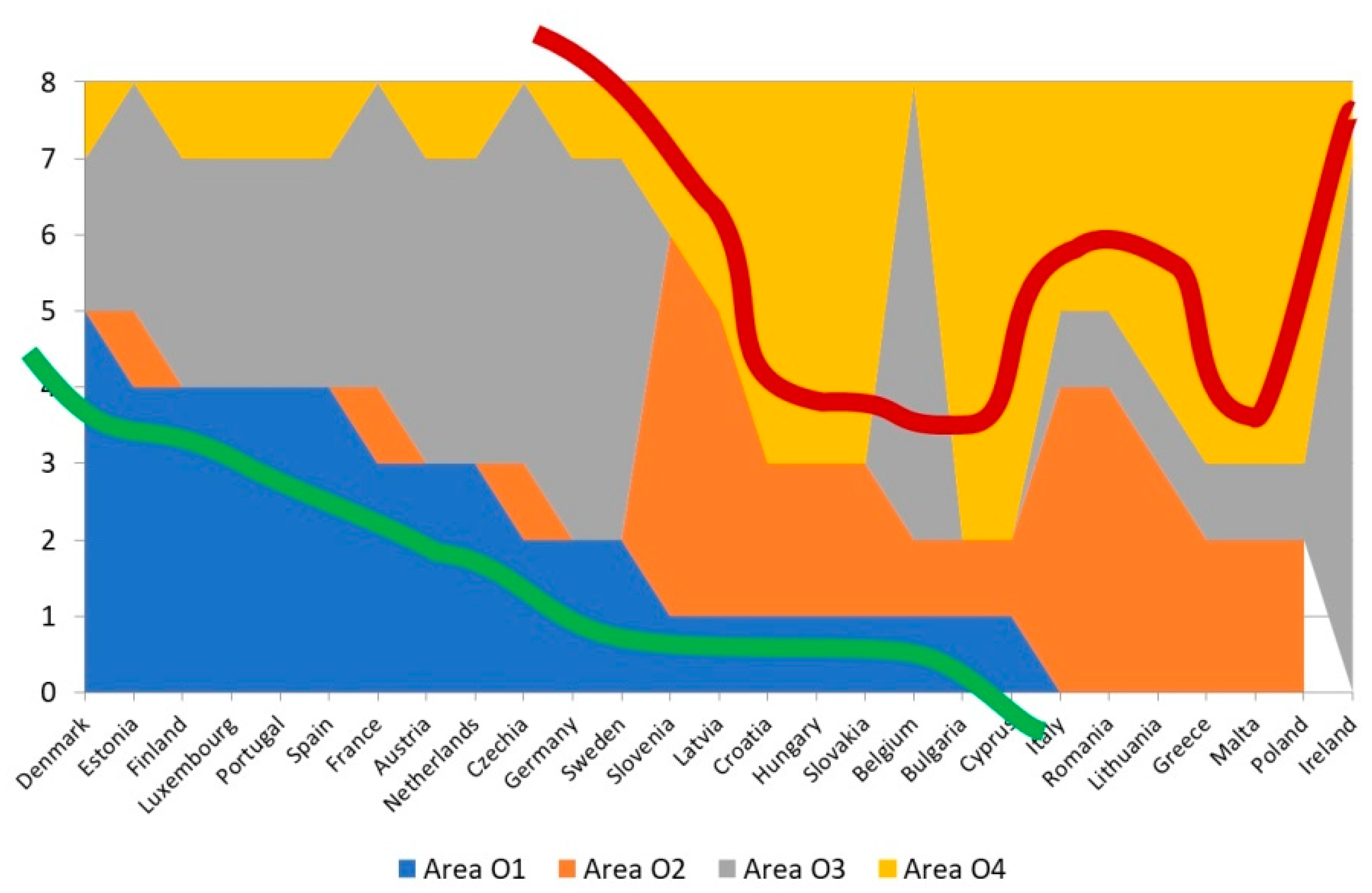

3.2.2. Factor: Constraints on Government Powers (Data from Table 5a,b in the Data Repository [75])

- Excelling in the rule of law and responsible implementation of energy policies, including elements of the green economy, are Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, France, Austria, and the Netherlands.

- Demonstrating average adherence to the rule of law and average implementation of energy policies, including elements of the green economy, are Czechia, Germany, Sweden, Slovenia, Latvia, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Belgium.

- Struggling significantly with the rule of law and displaying limited implementation of energy policy, including green economy elements, are Bulgaria, Cyprus, Italy, Romania, Lithuania, Greece, Malta, Poland, and Ireland.

- The most law-abiding countries that also implement green economy policies are Denmark, followed by Estonia, Finland, Luxembourg, Portugal, and Spain.

- The countries that exhibit law-abiding tendencies but lean toward brown economy policies are Slovenia, Latvia, Italy, and Romania.

- The countries with a below-average score in the rule of law dimension of Constraints on Government Powers but still implementing green economy policies include Ireland, Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Sweden, France, Austria, and the Netherlands.

- The countries facing the most significant rule of law challenges and also implementing brown economy policies are Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, Malta, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, Poland, and Lithuania.

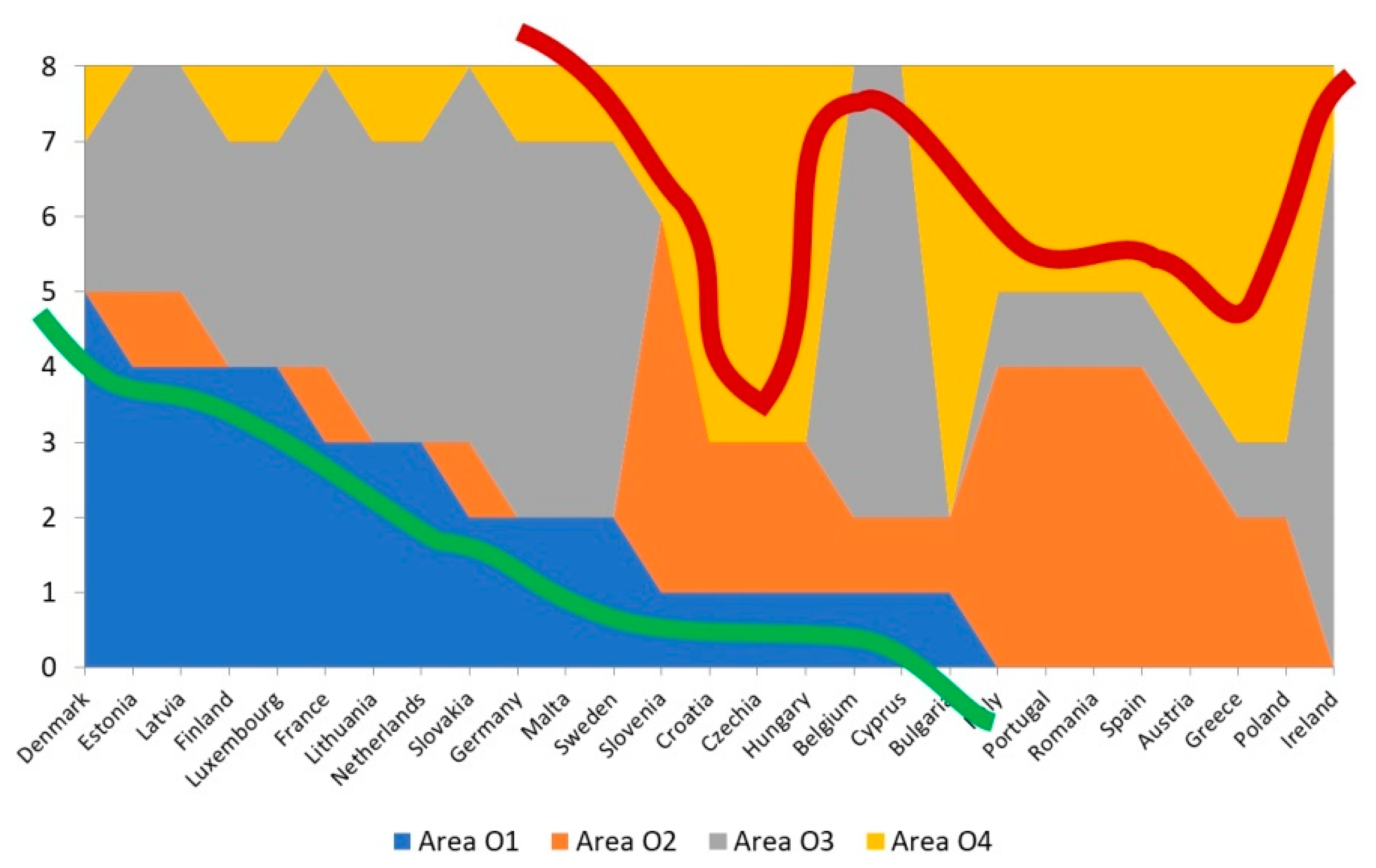

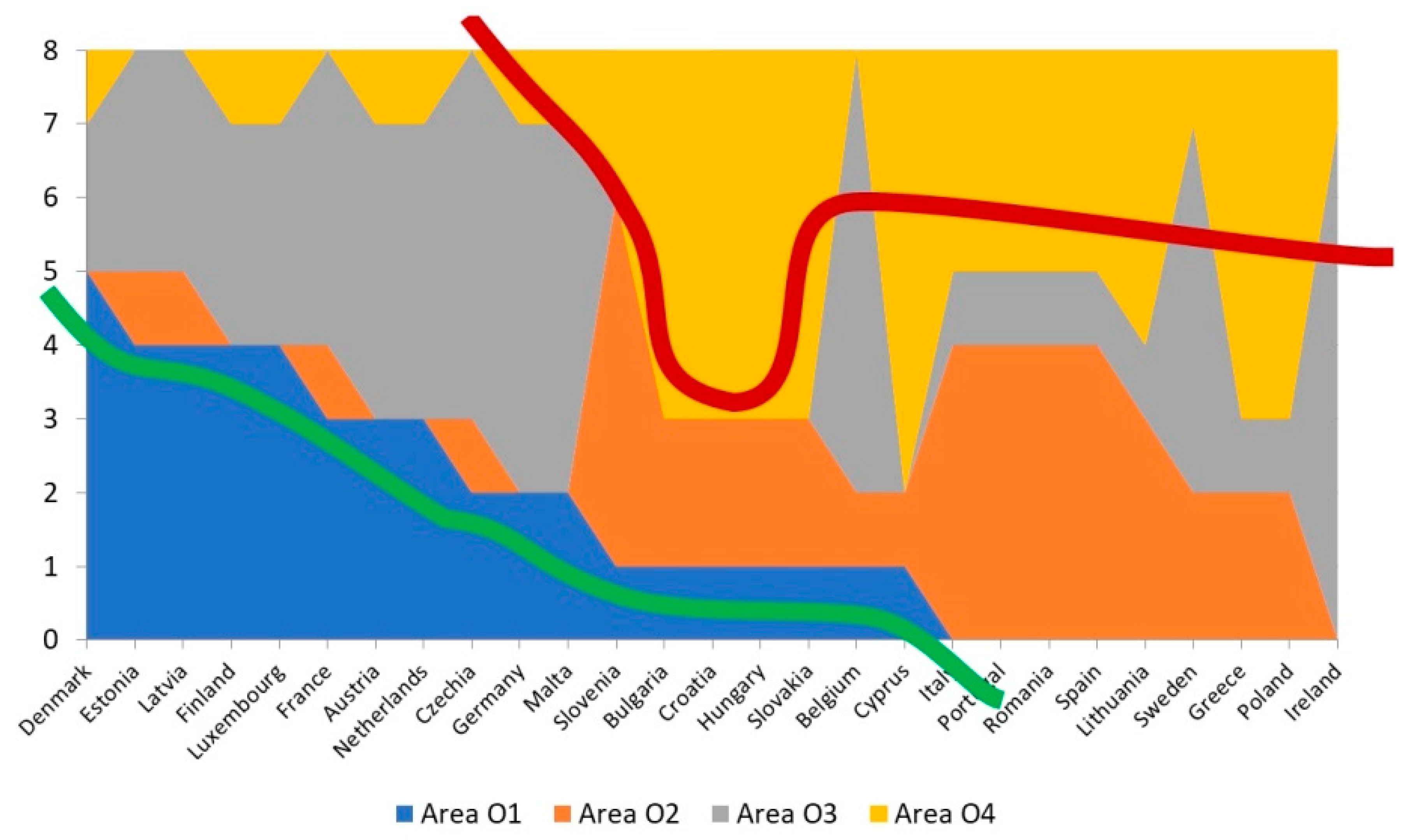

3.2.3. Factor: Open Government (Data from Table 7a,b in the Data Repository [75])

- The countries that perform exceptionally well in terms of the rule of law and the responsible implementation of energy policies, including elements of the green economy, are Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Finland, Luxembourg, France, Lithuania, and the Netherlands.

- The countries that exhibit an average performance in terms of the rule of law and the implementation of energy policies, including green economy elements, are Slovakia, Germany, Malta, Sweden, Slovenia, Croatia, Czechia, Hungary, Belgium, and Cyprus.

- The countries with significant rule of law challenges and limited implementation of energy policy, including green economy elements, include Bulgaria, Italy, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Austria, Greece, Poland, and Ireland.

- Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, and Finland exhibit the highest level of adherence to the rule of law and actively pursue green economy policies.

- Luxembourg and France are actively involved in green economy policies but have undefined rule of law standings.

- Countries like Ireland, Belgium, Cyprus, Slovakia, Germany, Malta, Sweden, Lithuania, and the Netherlands face rule of law challenges in the context of “Open Government,” yet they are actively implementing green economy policies.

- Slovenia demonstrates compliance with the rule of law while pursuing brown economy policies.

- Italy, Portugal, Romania, and Spain are focused on brown economy policies and have undefined rule of law standings.

- Bulgaria, Poland, and Greece, as well as Croatia, Czechia, Hungary, and Austria, confront significant rule of law issues and are simultaneously pursuing brown economy policies.

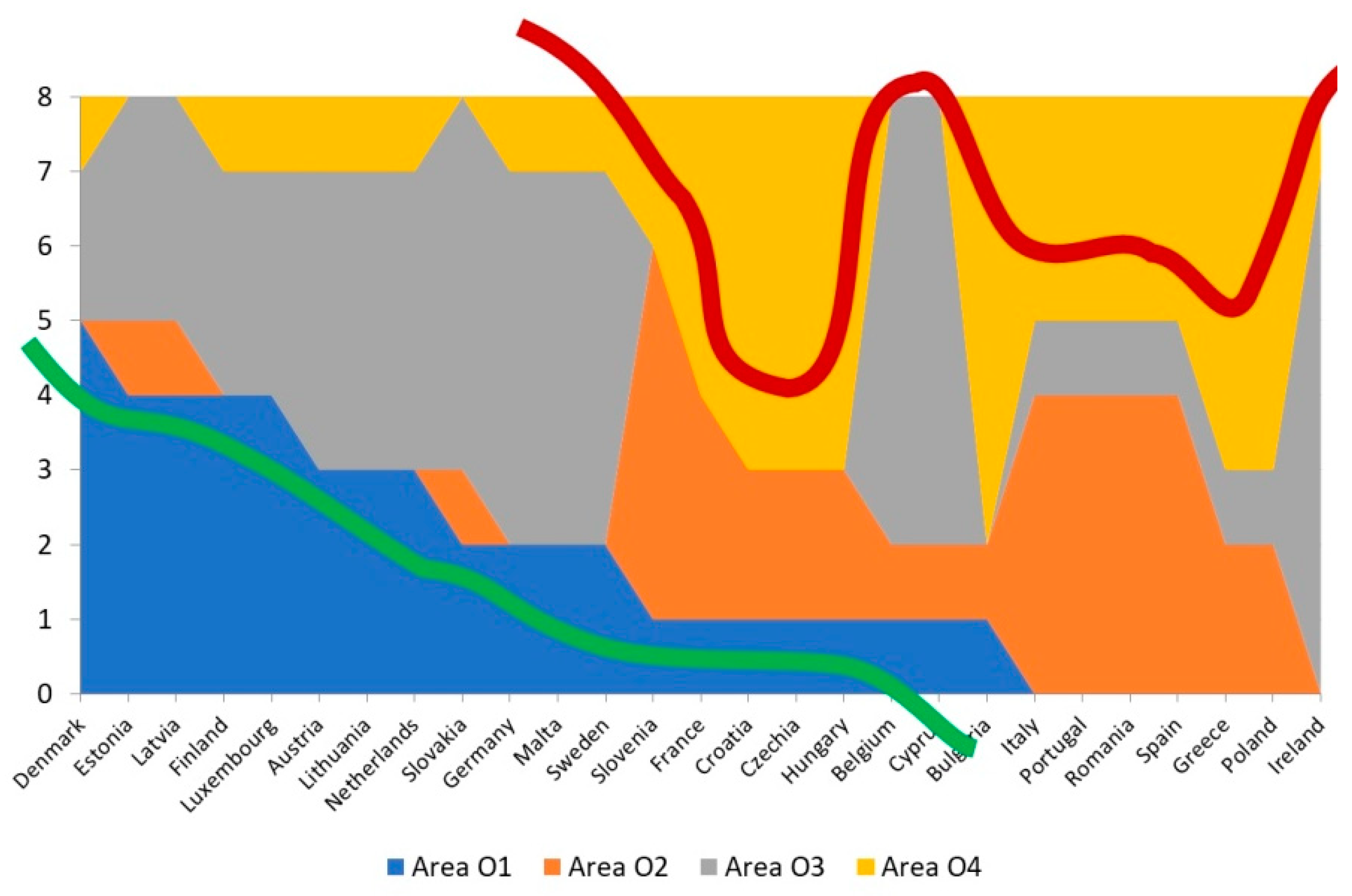

3.2.4. Factor: Fundamental Rights (Data from Table 9a,b in the Data Repository [75])

- Achieve a high level of compliance with the rule of law and responsibly implement energy policies, including elements of the green economy—Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Finland, Luxembourg, Austria, Lithuania, and the Netherlands.

- Demonstrate average adherence to the rule of law and moderately implement energy policies, including elements of the green economy—Slovakia, Germany, Malta, Sweden, Slovenia, France, Croatia, Czechia, Hungary, Belgium, and Cyprus.

- Experience significant rule of law challenges and exhibit limited implementation of energy policies, including green economy elements—Bulgaria, Italy, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Greece, Poland, and Ireland.

- The countries that demonstrate the highest adherence to the rule of law and actively implement green economy policies are Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, and Finland.

- Luxembourg and France are pursuing green economy policies but have an undefined status in terms of the rule of law.

- The countries with rule of law challenges in the Fundamental Rights dimension (below average) but actively implementing green economy policies include Ireland, Belgium, Cyprus, Slovakia, Germany, Malta, Sweden, Austria, Lithuania, and the Netherlands.

- Slovenia adheres to the rule of law and implements brown economy policies.

- Italy, Portugal, Romania, and Spain are pursuing brown economy policies but have an undefined status in terms of the rule of law.

- The countries facing the most significant rule of law challenges and actively implementing brown economy policies are Bulgaria, Poland, and Greece, followed by Croatia, Czechia, and Hungary.

3.2.5. Factor: Regulatory Enforcement (Data from Table 11a,b in the Data Repository [75])

- The countries that excel in both the rule of law and the responsible implementation of energy policies, including elements of the green economy, are Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Luxembourg, Spain, France, Austria, Lithuania, and the Netherlands.

- The countries that maintain an average level of rule of law and implement energy policies including elements of a green economy to an average extent include Czechia, Germany, Sweden, Slovenia, Latvia, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Belgium.

- The countries that face significant rule of law challenges and have limited implementation of energy policies including green economy elements are Bulgaria, Cyprus, Italy, Portugal, Romania, Greece, Malta, Poland, and Ireland.

- The countries that are most law-abiding and actively implement green economy policies are Denmark and Estonia.

- Finland, Luxembourg, and Spain are pursuing green economy policies, but their status regarding the rule of law is undefined.

- There is a rule of law problem in the Regulatory Enforcement dimension (below average) but the implementation of green economy policies is visible in countries like Ireland, Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Sweden, France, Austria, Lithuania, and the Netherlands.

- Slovenia and Latvia maintain a law-abiding status but implement brown economy policies.

- Italy, Portugal, and Romania are actively pursuing brown economy policies but also face rule of law challenges.

- The countries with the most significant rule of law issues and simultaneous implementation of brown economy policies are Bulgaria, Cyprus, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, Poland, Greece, and Malta.

3.2.6. Regulatory Quality Index (Data from Table 13a,b in the Data Repository [75])

- Those who excel in both the rule of law and the responsible implementation of energy policies, encompassing green economy elements, are Denmark, Estonia, Latvia, Finland, Luxembourg, France, Austria, and the Netherlands.

- The countries that maintain an average level of rule of law and implement energy policies including green economy aspects are Czechia, Germany, Malta, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, Belgium, and Cyprus.

- The countries with significant rule of law challenges and limited progress in energy policy, particularly in green economy areas, include Italy, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Lithuania, Sweden, Greece, Poland, and Ireland.

- The countries most committed to the rule of law and the implementation of green economy policies are Denmark, Estonia, and Latvia.

- Finland, Luxembourg, and France are pursuing green economy policies but have undefined rule of law standings.

- There is a rule of law deficiency in the dimension of the Regulatory Quality Index (below average) but the implementation of green economy policies is evident in Ireland, Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Malta, Sweden, Austria, and the Netherlands.

- The countries that adhere to the rule of law but implement brown economy policies include Slovenia.

- Italy, Portugal, Romania, and Spain have undefined rule of law standings and are pursuing brown economy policies.

- The most substantial rule of law challenges combined with the implementation of brown economy policies are experienced by Bulgaria, Cyprus, Poland, Greece, as well as Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, and Lithuania.

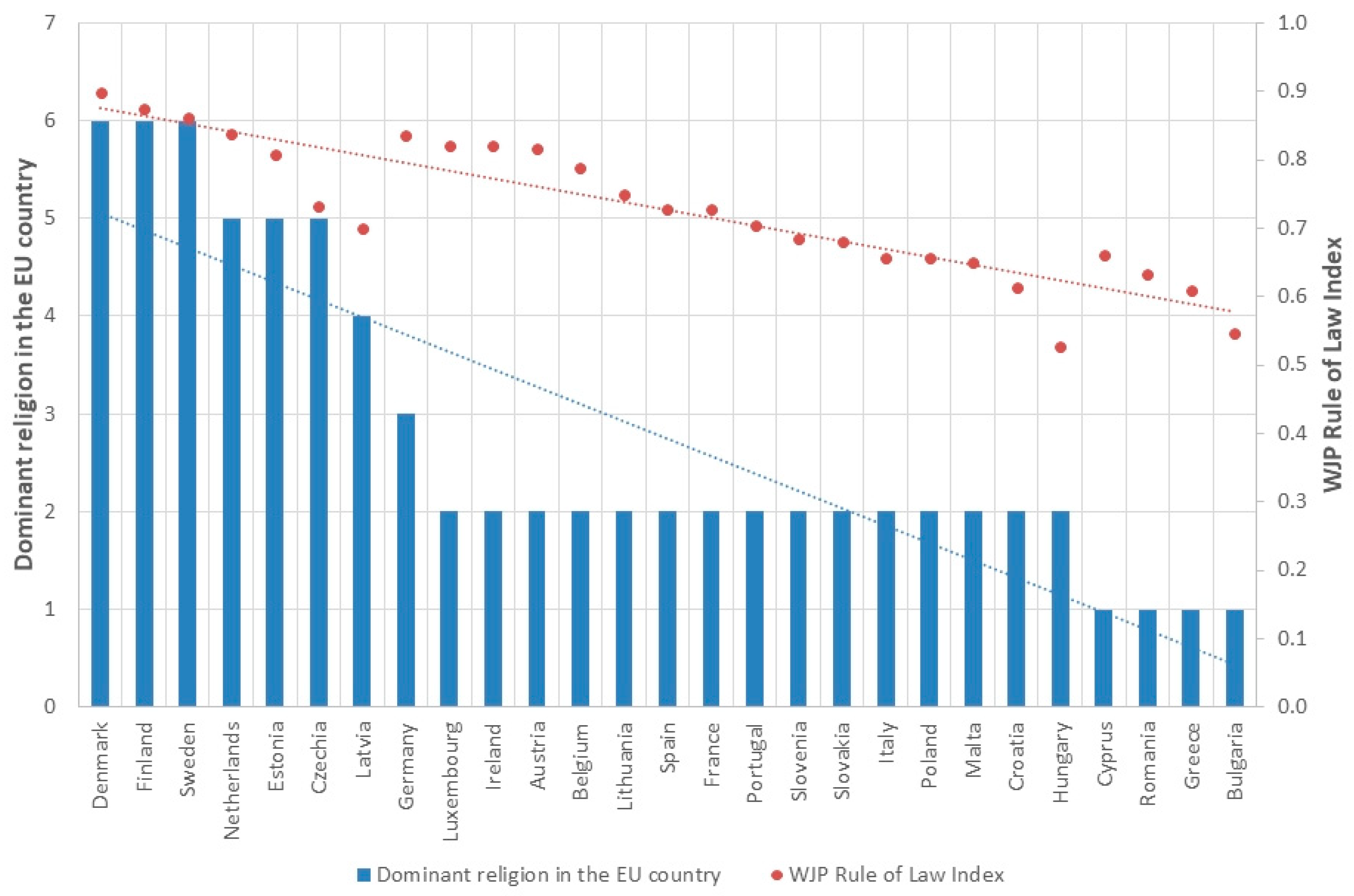

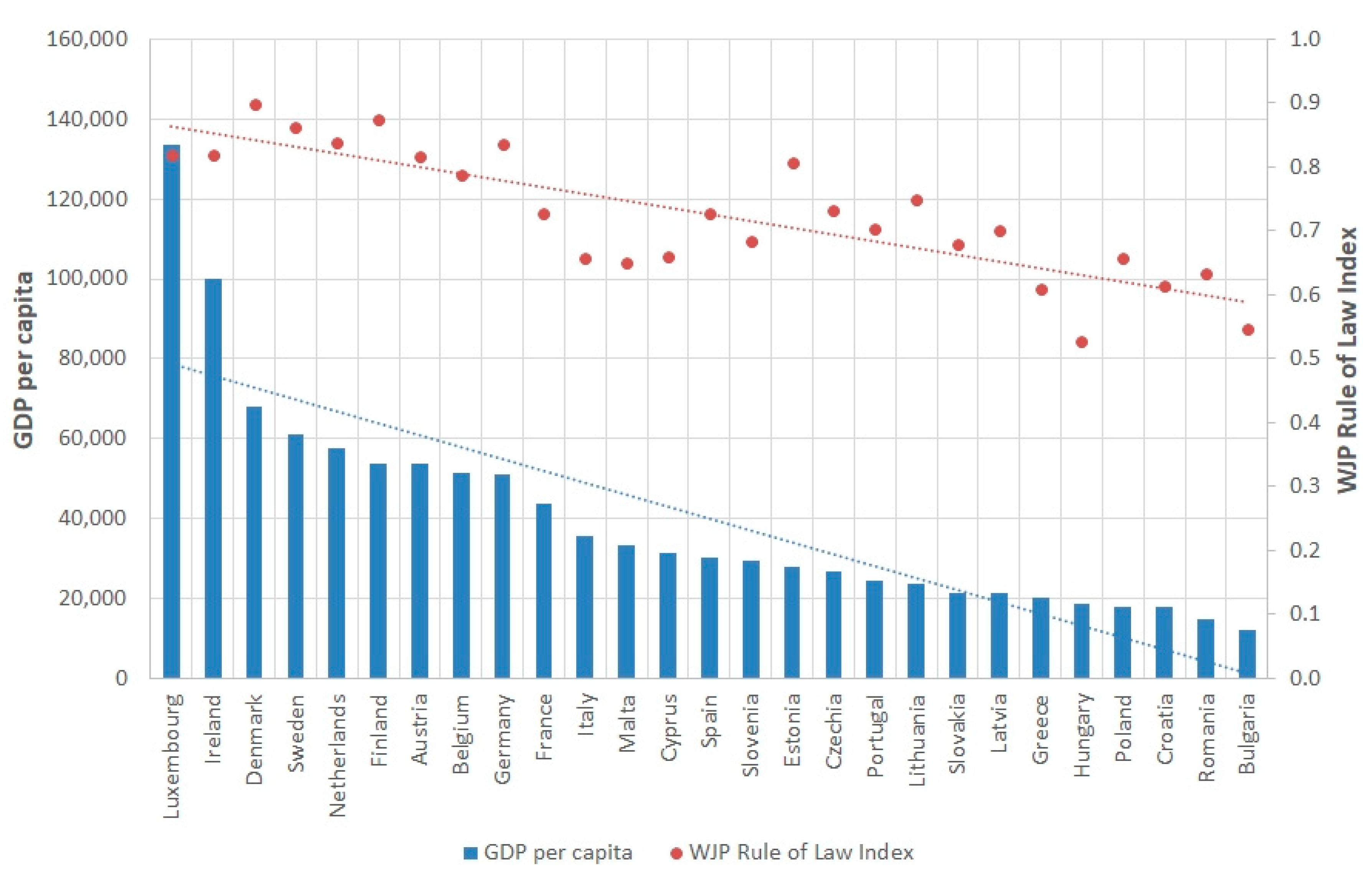

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Recommendations on the Rule of Law and Energy Policy

- The EU’s energy policy is determined by a number of factors, one of which is the level of rule of law in various member countries.

- The rule of law (and its level) in a given country influences the implementation of energy policy resulting from the need to implement EU law and implement solutions that fulfill it.

- A low level of rule of law in an EU member state can contribute to delays in or the deformation of the energy policy objectives implemented by that state within the framework of the whole that is the EU.

- The most significant influence on the effectiveness of the implementation of EU laws and obligations to other member states—linked to the rule of law—in the area of energy policy is related to “Fundamental Rights” and “Order and Security” (see FR and OS in Table 2).

- In the EU, the best performers in terms of the rule of law and responsible implementation of energy policy are Denmark, Finland, Luxembourg, and Spain. In the EU, performing very badly with the rule of law and implementing energy policy in a limited way are Latvia, Greece, Poland, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Cyprus.

5.2. Limitations of Research

5.2.1. Theoretical Limitations

5.2.2. Methodology Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hix, S. The Political System of the European Union; PWN Scientific Publishers: Warszawa, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cini, M. The European Union Organization and Functioning; Polish Economic Publishing House: Warszawa, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Beetham, D.; Lord, C. Legitimacy and European Union; Longman: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, D. A System Analysis of Political Life; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT:PL:PDF (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Brack, N.; Coman, R. Sovereignty Conflicts in the European Union. In Dans Les Cahiers du Cevipol; Crespy, A., Ed.; CEVIPOF: Paris, France, 2019; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rüffi, N. EU science diplomacy in a contested space of multi-level governance: Ambitions, constraints and options for action. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 103842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosse, T. The two-tier political system in Europe. Eur. Rev. 2012, 2, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kownacki, T. Legitimizing the Political System of the European Union; Elipsa Publishing House: Warszawa, Poland, 2014; pp. 275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Nugent, N. The European Union. Power and Politics; Jagiellonian University Publishing House: Kraków, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Members of the Helsinki Rule of Law Forum. A Declaration on the Rule of Law in the European Union. Verfassungsblog on Metters Constitutional. 2022. Available online: https://verfassungsblog.de/a-declaration-on-the-rule-of-law-in-the-european-union/ (accessed on 3 January 2024).

- Pech, L. The rule of law as a well-established and well-defined principle of EU law. Hague J. Rule Law 2022, 14, 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijers Committee. Rule of Law—Frequently Asked Questions. Debunking Common Myths. 2022. Available online: https://www.commissie-meijers.nl/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/rule-of-law-faqs-polishpdf-622b1cb7cc248.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Energy.ec.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energy-strategy/energy-union_pl (accessed on 23 July 2023).

- Busch, H.; Ruggiero, S.; Isakovic, A.; Hansen, T. Policy challenges to community energy in the EU: A systematic review of the scientific literature. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 151, 111535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osička, J.; Černoch, F. European energy politics after Ukraine: The road Ahead. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 91, 102757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europarl.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/pl/sheet/68/polityka-energetyczna-zasady-ogolne (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Wach, K.; Glodowska, A.; Maciejewski, M.; Sieja, M. Europeanization Processes of the EU Energy Policy in Visegrad Countries in the Years 2005–2018. Energies 2021, 14, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunz, S.; Gawel, E.; Lehmann, P. Towards a general “Europeanization” of EU Member States’ energy policies? Econ. Energy Environ. Policy 2015, 4, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sosnicki, M.; Wisniewski, D. Sustainable development concept—Eco-energy perspective. Def. Knowl. 2023, 283, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Majumdar, A. Opportunities and challenges for a sustainable energy future. Nature 2012, 488, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, M.Z.; Delucchi, M.A. A path to sustainable energy by 2030. Sci. Am. 2009, 301, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmik, C.; Bhowmik, S.; Ray, A. Optimal green Energy Source Selection: An eclectic Decision. Energy Environ. 2020, 31, 842–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crownshaw, T.; Morgan, C.; Adams, A.; Sers, M.; Britto dos Santos, N.; Damiano, A.; Gilbert, L.; Yahya Haage, G.; Horen Greenford, D. Over the horizon: Exploring the conditions of a post-growth world. Anthr. Rev. 2019, 6, 117–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, J.F.; Rajeswari, S.R. Post-growth in the global south? Some reflections from India and Bhutan. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 150, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0550 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52022DC0230 (accessed on 1 February 20024).

- Cheba, K.; Bak, I.; Szopik-Depczyńska, K.; Ioppolo, G. Directions of green transformation of the European Union countries. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrini, E. Economic integration, structural change, and uneven development in the European Union. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2019, 50, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Nuta, A.C.; Mishra, P.; Ayad, H. The impact of informality and institutional quality on environmental footprint: The case of emerging economies in a comparative approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 348, 119325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, M. Competitive Strategy; Free Press: Nowy Jork, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen, M.; Peteraf, M.A. Competitor identification and competitor analysis: A broad-based managerial approach. Manag. Decis. Econ. Manage. Decis. Econ. 2002, 23, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Świątkowski, W. The cosmopolitan form of the rule of law in the context of the federalization of the European Union—Its assessment and relevance for competitiveness. Civ. Et Lex 2022, 3, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mik, C. Opinion on the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Strengthening the Rule of Law in the Union. An action plan (COM(2019) 343 final). BAS Leg. Noteb. 2019, 4, 93–94. [Google Scholar]

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32020R2092 (accessed on 6 May 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:caa88841-aa1e-11e3-86f9-01aa75ed71a1.0015.01/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 1 February 20024).

- Marcisz, P.; Taborowski, M. The European Union’s new framework for strengthening the rule of law. A critical analysis of critical analysis (polemical article). State Law 2017, 12, 100–109. [Google Scholar]

- Commission.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/upholding-rule-law/rule-law/rule-law-mechanism_pl (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:2e95c008-037b-11ed-acce-01aa75ed71a1.0022.02/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:caa88841-aa1e-11e3-86f9-01aa75ed71a1.0015.04/DOC_1&format=PDF (accessed on 1 February 20024).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT (accessed on 1 February 20024).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?toc=OJ:L:2018:328:TOC&uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2018.328.01.0001.01.POL (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2019.158.01.0125.01.POL&toc=OJ:L:2019:158:TOC (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2019.158.01.0054.01.POL&toc=OJ:L:2019:158:TOC (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2019.158.01.0001.01.POL&toc=OJ:L:2019:158:TOC (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2018.328.01.0210.01.POL&toc=OJ:L:2018:328:TOC (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0558 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?toc=OJ:L:2018:156:TOC&uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2018.156.01.0075.01.POL (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0802 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32018L2001&qid=1607617602591 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0557 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32009L0073&from=PL (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/ALL/?uri=CELEX:32009R0715 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0803 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=COM:2021:804:FIN (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:02003L0096-20230110 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/pl/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0563 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32022R0869 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32019R0942 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32019D0504 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Commission.Europa.eu 2023. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/energy-climate-change-environment/implementation-eu-countries/energy-and-climate-governance-and-reporting/national-long-term-strategies_pl#:~:text=EU%20long%2Dterm%20strategy,-The%20Commission%20put&text=The%20European%20Council%20endorsed%20in,(UNFCCC)%20in%20March%2020 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/pl/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0559 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Eur-lex.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX:52021PC0561 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- ESPAS. Global Trends to 2030: Challenges and Choices for Europe. 2023. Available online: https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/global-trends-2030-%E2%80%93-challenges-and-choices-europe (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Office of the Director of National Intelligence (2023) Global Trends 2040: A More Contested World. Available online: https://www.dni.gov/index.php/gt2040-home/gt2040-media-and-downloads (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Word Economic Forum (2022) Global Risk Report 2022. 17th Edition, Insight Report. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_The_Global_Risks_Report_2022.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Svendsen, G.T. Environmental Reviews and Case Studies: From a Brown to a Green Economy: How Should Green Industries be Promoted? Environ. Pract. 2013, 15, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Hernández, J.G. Strategic transformational transition of green economy, green growth and sustainable development: An institutional approach. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Green Technol. 2020, 11, 34–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, R.; Daniluk, P.; Nowakowska-Krystman, A.; Kownacki, T. Critical Success Factors of the Energy Sector Security Strategy: Case of Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulich, A. The meaning of the sustainable development economy. Mark.-Soc. Cult. 2018, 4, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato, D.; Korhonen, J. Integrating the green economy, circular economy and bioeconomy in a strategic sustainability framework. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 188, 107143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bina, O. The Green Economy and Sustainable Development: An Uneasy Balance? Environ. Plan. C Gov. Policy 2013, 31, 1023–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Justice Project® (WJP). 2023. Available online: http://worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/global (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- TheGlobalEconomy.com (2023) GDP per Capita, Current Dollars—Country Rankings. Available online: https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/GDP_per_capita_current_dollars/European-union/ (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Nowakowska-Krystman, A.; Wisniewski, R. Correlation of the Rule of Law with Energy Policy—Position of EU Countries. Data Repository. RepOD-Repository for Open Data. 2023. Available online: https://repod.icm.edu.pl/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.18150/FHYR7N (accessed on 8 January 2024).

- Commission.europa.eu 2023. Available online: http://commission.europa.eu/energy-climate-change-environment/implementation-eu-countries/energy-and-climate-governance-and-reporting/national-energy-and-climate-plans_en (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Ec.europa.eu/Eurostat. 2023. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/NRG_BAL_C__custom_5297863/default/table?lang=en (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Green-Business.ec.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: http://green-business.ec.europa.eu/eco-innovation_en (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Commission.Europa.eu. 2023. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/eu-budget/protection-eu-budget/rule-law-conditionality-regulation_pl (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Circabc.europa.eu. 2023. Available online: http://circabc.europa.eu/ui/group/96ccdecd-11b4-4a35-a046-30e01459ea9e/library/ddb0a147-f2fc-4555-849a-215c95ba592d/details (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- Nationalgrid.com. 2023. Available online: https://www.nationalgrid.com/stories/energy-explained/what-are-electricity-interconnectors (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- European Parliament and Council (2020) Regulation (EU, Euratom) 2020/2092 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2020 on the General System of Conditionality to Safeguard the Union’s Budget. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32020R2092 (accessed on 23 May 2023).

- McGee, J. Strategic groups: Theory and practice. In The Oxford Handbook of Strategy: A Strategy Overview and Competitive Strategy; Campbell, A., Faulkner, D.O., Eds.; Oxford Academic: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 267–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meilich, O. Strategic groups maps: Review, synthesis, and guidelines. J. Strategy Manag. 2019, 12, 447–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Pierre, J.; Schreuder, H. From Coal to Biotech: The Transformation of DSM with Business School Support; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; ISBN 978-3-662-46298-0. [Google Scholar]

- Domański, J. Strategic group analysis of Poland’s nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2010, 39, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. Christian Population as Percentages of Total Population by Country. 2011. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2011/12/19/table-christian-population-as-percentages-of-total-population-by-country/ (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Pew Research Center. Religious Composition by Country, in Percentages. 2012. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2012/12/18/table-religious-composition-by-country-in-percentages/ (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- ARDA. National/Regional Profiles. The Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). 2020. Available online: https://www.thearda.com/world-religion/national-profiles?REGION=0&u=180c&u=106c&u=23r (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Pew Research Center. Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe, National and Religious Identities Converge in a Region Once Dominated by Atheist Regimes. 2017. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2017/05/10/religious-belief-and-national-belonging-in-central-and-eastern-europe/ (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Szymczak, W. Civil society and religion. Types of relations in the perspective of leading theories of sociology of religion. Ann. Soc. Sci. 2015, 43, 49–75, 52. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=301374 (accessed on 27 July 2023).

- Gardawski, J. Protestantism and Civil Society: The Role of Social Capital—Civil Society and Trust. 2017. Available online: https://forumewangelickie.eu/index.php/xxi-fe-wroclaw-2017/159-protestantyzm-a-spoleczenstwo-obywatelskie-rola-kapitalu-spolecznego-spoleczenstwo-obywatelskie-a-zaufanie (accessed on 27 July 2023).

| Category | Brown Economy | Green Economy |

|---|---|---|

| P: | Economy of energy supply | Self-sufficiency, energy security |

| P: | Relying on the cheapest energy sources | Diversification of energy sources |

| P: | Relying on traditional economic sectors | Change in economic structure |

| P: | Destruction of biodiversity | Protection of biodiversity |

| E: | Unlimited economic growth | Decoupling economic growth from natural resource consumption |

| E: | Infinity of resources | Limited resources |

| E: | Reliance on fossil fuels | Renewable energy sources |

| E: | Intensive consumption of natural resources | Energy efficiency |

| E: | Consolidation of the sector | Sector dispersion |

| S: | Global social inequality | Intergenerational and interregional justice |

| S: | Unlimited consumption (overconsumption) | Sustainable consumption |

| S: | Lack of accountability | Corporate social responsibility and ESG |

| S: | Weakening public confidence | Growing public confidence |

| T: | Greenhouse gas emissions | Clean production |

| T: | Modification of existing technologies | Advances in clean technology |

| Lp. | Rule of Law Factors | Label | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Overall Score | T | Average obtained from indicators 1–4, 6–9 |

| 1 | Constraints on Government Powers | CGP | Measures the extent to which those who govern are bound by law. It comprises the means, both constitutional and institutional, by which the powers of the government and its officials and agents are limited and held accountable under the law. It also includes non-governmental checks on the government’s power, such as a free and independent press. |

| 2 | Open Government | OG | Measures the openness of the government, defined by the extent to which a government shares information, empowers people with tools to hold it accountable, and fosters citizen participation in public policy deliberations. This factor measures whether basic laws and information on legal rights are publicized and evaluates the quality of information published by the government. |

| 3 | Fundamental Rights | FR | Recognizes that a system of positive law that fails to respect the core human rights established under international law is at best “rule by law” and does not deserve to be called a rule of law system. Since there are many other indices that address human rights, and because it would be impossible for the index to assess adherence to the full range of rights, this factor focuses on a relatively modest menu of rights that are firmly established under the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and are most closely related to rule of law concerns. |

| 4 | Regulatory Enforcement | RE | Measures the extent to which regulations are fairly and effectively implemented and enforced. Regulations, both legal and administrative, structure behaviors within and outside of the government. This factor does not assess which activities a government chooses to regulate nor does it consider how much regulation of a particular activity is appropriate. Rather, it examines how regulations are implemented and enforced. |

| 5 | Regulatory Quality Index | RG | The index of regulatory quality captures perceptions of the ability of the government to formulate and implement sound policies and regulations that permit and promote private sector development. |

| 6 | Absence of Corruption | AC | Measures the absence of corruption in government. The factor considers three forms of corruption: bribery, improper influence by public or private interests, and misappropriation of public funds or other resources. These three forms of corruption are examined with respect to government officers in the executive branch, the judiciary, the military, police, and the legislature. |

| 7 | Order and Security | OS | Measures how well a society ensures the security of persons and property. Security is one of the defining aspects of any rule of law society and is a fundamental function of the state. It is also a precondition for the realization of the rights and freedoms that the rule of law seeks to advance. |

| 8 | Civil Justice | CJ | It measures whether ordinary people can resolve their grievances peacefully and effectively through the civil justice system. It measures whether civil justice systems are accessible and affordable as well as free of discrimination, corruption, and improper influence by public officials. It examines whether court proceedings are conducted without unreasonable delays and whether decisions are enforced effectively. It also measures the accessibility, impartiality, and effectiveness of alternative dispute resolution mechanisms. |

| 9 | Criminal Justice | CJ | Evaluates a country’s criminal justice system. An effective criminal justice system is a key aspect of the rule of law, as it constitutes the conventional mechanism to redress grievances and bring action against individuals for offenses against society. An assessment of the delivery of criminal justice should take into consideration the entire system, including the police, lawyers, prosecutors, judges, and prison officers. |

| O1 | law-abiding above average and showing an indicator that realizes the green economy above average | O2 | law-abiding above average and showing an indicator that realizes the brown economy below average |

| O3 | law-abiding below average and showing an indicator that realizes the green economy above average | O4 | law-abiding below average and exhibiting an indicator realizing the brown economy below average |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wisniewski, R.; Nowakowska-Krystman, A.; Kownacki, T.; Daniluk, P. The Impact of the Rule of Law on Energy Policy in European Union Member States. Energies 2024, 17, 739. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17030739

Wisniewski R, Nowakowska-Krystman A, Kownacki T, Daniluk P. The Impact of the Rule of Law on Energy Policy in European Union Member States. Energies. 2024; 17(3):739. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17030739

Chicago/Turabian StyleWisniewski, Radoslaw, Aneta Nowakowska-Krystman, Tomasz Kownacki, and Piotr Daniluk. 2024. "The Impact of the Rule of Law on Energy Policy in European Union Member States" Energies 17, no. 3: 739. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17030739

APA StyleWisniewski, R., Nowakowska-Krystman, A., Kownacki, T., & Daniluk, P. (2024). The Impact of the Rule of Law on Energy Policy in European Union Member States. Energies, 17(3), 739. https://doi.org/10.3390/en17030739