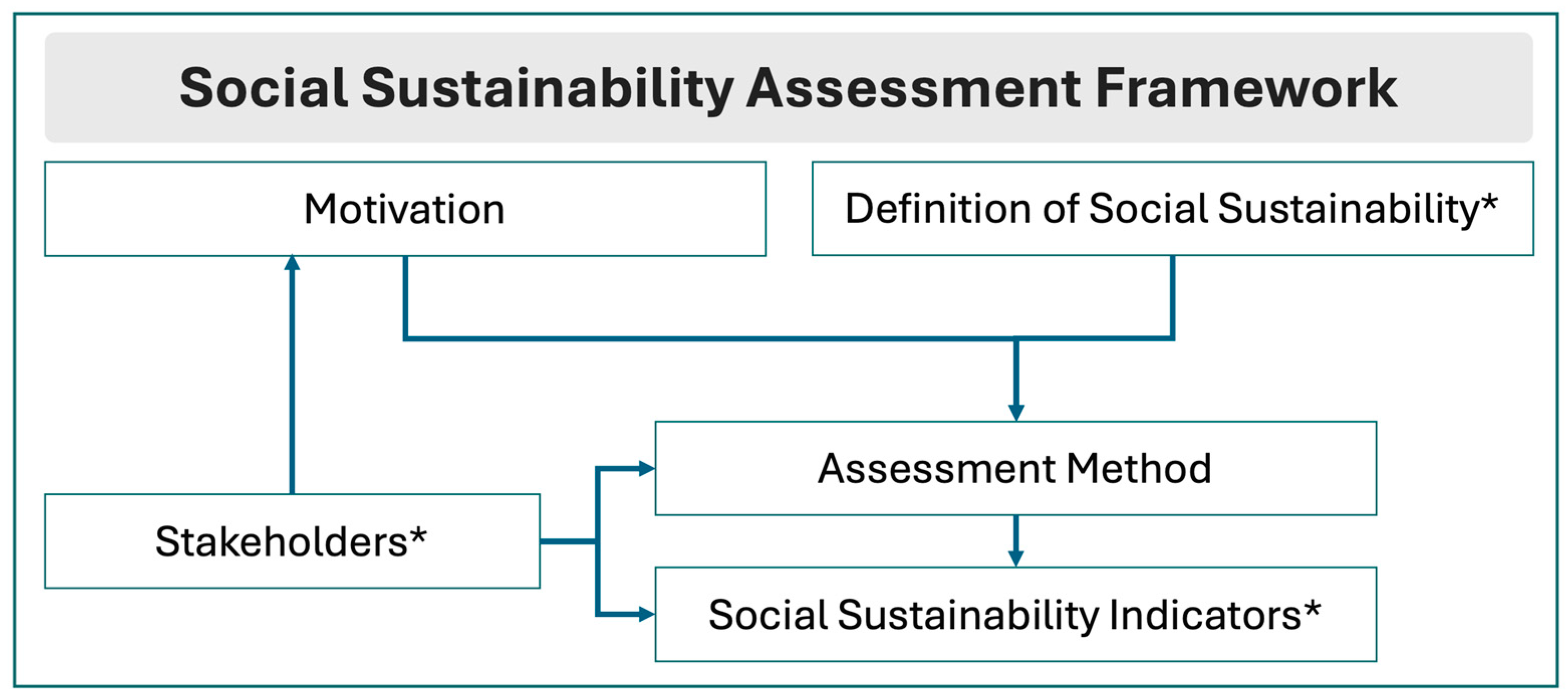

3.1. Overview of the Proposed Framework

A conceptual framework for the social sustainability assessment of energy systems was developed as shown in

Figure 6. Elements 1 and 3 are discussed briefly in this subsection while elements 2, 4, and 5 are discussed more thoroughly in the succeeding subsections.

An assessment of social sustainability begins with a clear motivation—which can be represented in the form of a problem statement, a specific goal, or a list of objectives. This element is not discussed extensively in this paper since all research mainly points to the overarching goal to evaluate the sustainability of energy systems. In addition to this main goal, four other motivations have been identified:

To try a new approach/method for sustainability assessment. For example, Shakouri G. et al. [

38] and Pereira et al. [

39] explored the application of data envelopment analysis in sustainability assessment. Other studies explored combinations of weighting and aggregation techniques in MCDA [

40,

41,

42] or incorporated life cycle approaches [

43,

44];

To conduct sustainability assessment in a particular country or region. There were studies conducted in China [

45,

46,

47], Egypt [

48,

49,

50], India [

44,

51,

52], Iran [

53,

54,

55], and the United Kingdom [

56,

57,

58], to name a few. Meanwhile, others shifted their focus to wider geographic coverage, such as developing countries [

38,

41,

59], Europe [

60,

61,

62], remote communities [

63,

64], countries along the Belt and Road [

65], or the Arctic region [

66];

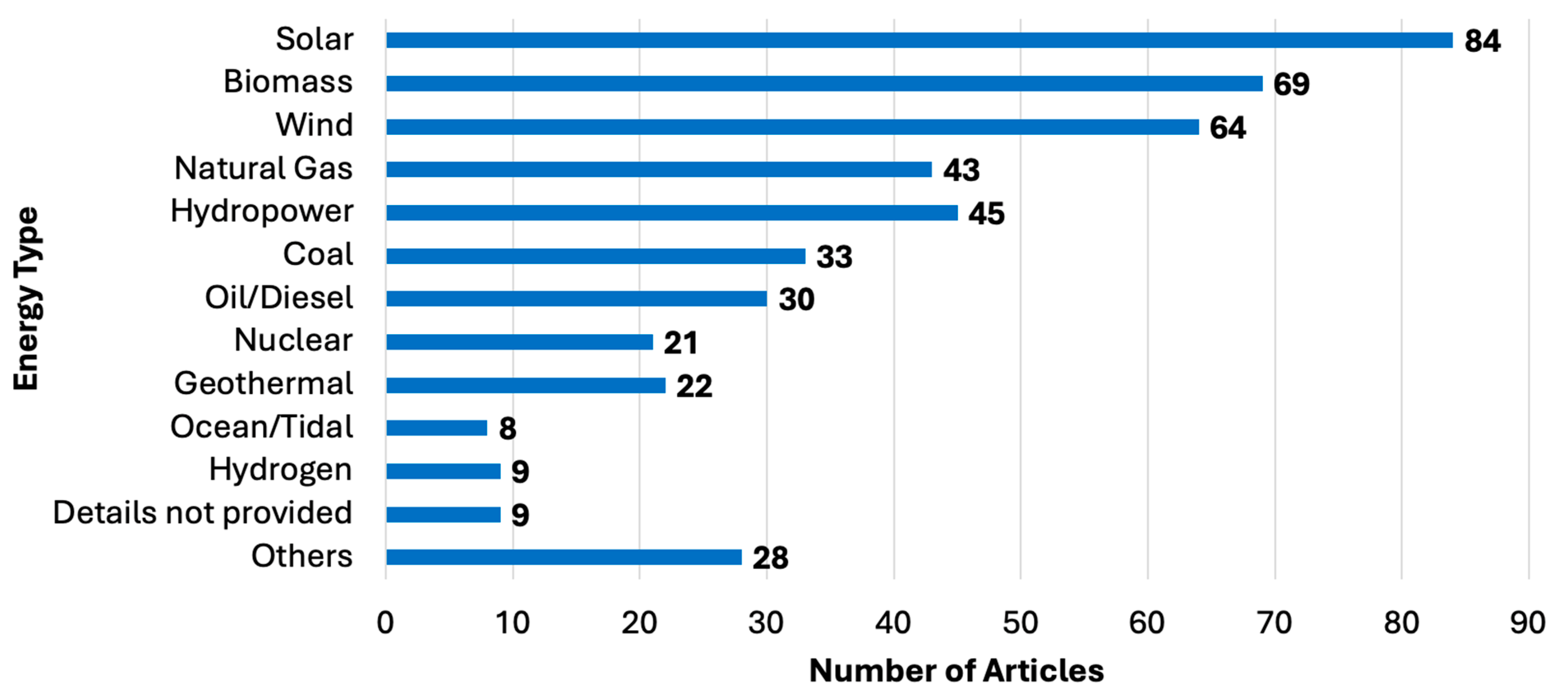

To conduct sustainability assessment for a particular energy type. The most prevalent energy types under this context are biomass [

50,

53,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83] and solar energy systems [

56,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89];

To explore the social aspect of energy system sustainability assessments. Only a few studies exclusively or heavily focused on social sustainability [

39,

61,

73,

80,

81,

84,

86,

90]. Others conducted a multi-pillar sustainability assessment but have emphasized the role of the social pillar [

1,

49,

63,

72,

74,

75,

78,

91,

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100,

101,

102,

103].

Next, to proceed with the assessment, the term “social sustainability” should be clearly defined or operationalized. Doing so will guide the selection of the assessment method and the indicators to measure social sustainability, among others. A more detailed discussion of social sustainability can be found in

Section 3.2 and

Section 3.4. Respectively, these sections summarize the existing definitions of social sustainability found in the literature and present synthesized themes generated from such definitions as well as the indicators that were used in the prior literature.

The next element in the framework is the assessment method. The present work does not focus on this topic for two main reasons. Firstly, previous work has already reviewed prevalent social sustainability assessment methods. For example, the work of Rafiaani et al. [

15] previously discussed three main assessment methods for social sustainability: socio-economic impact assessment (SEIA), social impact assessment (SIA), and social life cycle assessment (SLCA). Additionally, a methodological review paper would warrant a more extensive discussion, and often this would involve a significant in-depth discussion of the context and other components, which is not in balance with the analysis of the remaining components discussed below.

The review of 143 peer-reviewed articles performed in this research highlighted various methods. In order to streamline the discussion of such methods, the three major assessment categories provided by Ness et al. [

104] were adopted as follows:

Indicators and indices are simple measures that reflect system status according to their economic, social, and/or environmental aspect. Indicators/indices can be integrated (involves aggregation of sustainability aspects) or non-integrated (sustainability aspects are treated as mutually exclusive);

Product-related assessments comprise methods focused on analyzing the systems’ flows and processes. Since life cycle analysis is the most common assessment under this category, this type usually addresses the environmental aspect. However, life cycle tools for economic (life cycle costing) and social aspects (SLCA) have also emerged;

Integrated assessments are usually conducted for policy or project decision-making and often involve evaluating different scenarios or alternatives. This type generally applies systems analysis approaches to incorporate all sustainability dimensions. Common examples of this type of assessment are multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA), conceptual modelling, system dynamics, risk and uncertainty analyses, vulnerability analysis, cost–benefit analysis, and impact assessments.

Table 2 summarizes the articles covered in this review according to the abovementioned categories. A more detailed categorization of the assessment methods can be accessed from

Supplementary Material File S1.

From the pool of reviewed articles, integrated assessments are the most used assessment tool, with MCDA as the leading approach to perform sustainability assessment. The common MCDA tools used in previous studies were analytic hierarchy process (AHP), Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), VIseKriterijumska Optimizacija I Kompromisno Resenje (VIKOR), and fuzzy MCDA, among others. However, to improve the assessment and address certain limitations, other articles have combined MCDA with tools such as strengths–weaknesses–opportunities–threats analysis [

46], fuzzy logic [

135], and system dynamics [

139]. The scope, advantages, and disadvantages of MCDA are already adequately discussed in the previous literature [

8,

15,

104]. Readers are directed to the work of Wang et al. [

8], where detailed background about general MCDA steps and the different weighting, aggregation, and ranking techniques are thoroughly discussed.

Related to assessment methods are indicators, which were observed to have widespread use across all identified assessment methods in this literature review. In

Section 3.3, sub-themes (sub-criteria) surrounding the main themes of social sustainability have been developed to depict the variety of indicators that have been used in the pool of articles included in this review.

Finally, energy system stakeholders represent the final element of the proposed framework. These stakeholders can influence the social sustainability assessment of energy systems. Specifically, they help in providing data, selecting indicators, and assigning weights to these indicators. In other cases, they also help define scenarios as well as identify assumptions. The stakeholder groups identified from previous studies, as well as the common nature of involvement among these stakeholders, are presented in

Section 3.5.

From a practical standpoint, this framework offers a valuable reference for stakeholders tasked with evaluating the social sustainability of energy systems. It provides a structured approach that can be seamlessly integrated with economic and environmental assessments, particularly through the utilization of MCDA techniques.

From an academic standpoint, the framework illustrates numerous avenues for researchers to explore further. For instance, researchers could delve into refining the definition of social sustainability within energy systems. Moreover, considering the widespread use of MCDA tools in sustainability assessment, there is room for researchers to enhance existing tools or investigate tools that have not yet been utilized in the energy sector. Stakeholder involvement can also be investigated, specifically the nature, methods, and extent of their involvement in sustainability assessments. Lastly, the intersections of these elements, as elaborated in

Section 4, offer diverse research opportunities.

3.2. Social Sustainability Definitions

This research argues that, along with having a clear motivation, it is fundamental to define social sustainability first before performing an assessment. The definition will guide how to perform the assessment, as well as the tools or indicators that will be used to measure social sustainability.

After analyzing the full texts, 51 articles were found to have explicit definitions of social sustainability. In these articles, their authors have clearly defined how they view social sustainability. “Social sustainability is…”, “the social impacts of energy systems are…”, and “the social aspect is concerned with…” were some of the phrases that signaled an article’s definition of the concept. The extracted definitions are presented in

Supplementary Material File S1.

Meanwhile, 92 articles were identified to have an unclear or non-specific explanation of social sustainability. These studies either immediately proceeded to enumerate indicators or methods they used to measure social sustainability or just referred to a broad statement mentioning “social impacts” or “influences of the energy system to society”, without defining what those impacts or influences are. Despite the absence of an explicit definition, it can be implied that these articles view social sustainability based on the indicators that they use, which will be discussed in

Section 3.3.

Through conceptual content analysis, ten themes were developed from the definitions provided by the 51 articles. This is summarized in

Table 3, along with a brief description of each theme. The succeeding parts of this subsection provide insights into how previous articles’ definitions relate to each developed theme.

To this end, “social development/well-being and quality of life” and “socio-economic benefits” are the predominant themes reflecting social sustainability based on the number of articles, with 28 and 24 articles referring to said themes, respectively. Meanwhile, social sustainability in the form of “health and safety”, “energy access, quality, and reliability”, “social acceptance”, and “social equity” were also attributed to social sustainability, although in fewer articles. The remaining parts of this subsection briefly discuss each theme, as reflected by the definitions provided in the previous literature.

3.2.1. Social Development/Well-Being and Quality of Life

The theme “social development/well-being and quality of life” takes on several essential aspects of society and daily life, with prevalent terms and phrases including the words and phrases “welfare”, “well-being”, “quality of life”, and “living conditions/standards”, as commonly found in the previous literature [

47,

55,

64,

80,

98,

100,

103,

111,

112,

119,

136,

139,

160,

161,

177]. Articles frequently attribute energy systems as instrumental in enhancing or improving this “quality of life” [

47,

136,

160,

161,

162] or as solutions to address diverse social issues while contributing to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [

51,

62,

63,

177]. In the same context, Refs. [

111,

139] associate social sustainability with indicators that measure quality of life or well-being.

However, “quality of life” and “well-being” are inherently broad and subject to various interpretations. Moreover, expounding these terms inevitably intertwines with other themes of social sustainability described in the following subsections and with the other pillars of sustainability overall. For instance, Fedorova et al. [

80] correlates well-being with factors such as “prosperity, education, health, and safety”, while Fonseca et al. [

98] attributes quality of life to elements of equity and health.

Overall, the concept of social sustainability in the context of this theme is also intricately linked with diverse factors. These include environmental health and effects on local scenery [

105,

133], societal and human development [

55,

61,

64,

74,

180], workplace dynamics in the form of social support for the labor force [

166], and cultural preservation [

161], all of which collectively shape the well-being and quality of life within society.

3.2.2. Socio-Economic Benefits and Employment

Under the “socio-economic benefits and employment” theme, the majority of the articles referred to job creation, employment, or provision of livelihood opportunities as one of the significant social impacts of energy systems [

39,

50,

74,

101,

103,

116,

129,

150,

166]. Although some articles did not directly refer to employment, they mention the energy systems’ impacts on people’s livelihood [

83,

86,

173].

In addition to the focus on job creation and livelihood opportunities, several articles explore the broader socio-economic implications of energy systems [

64,

80]. These discussions include factors such as affordability [

127] and economic growth [

50,

74,

133,

166].

By providing opportunities for employment and livelihood, coupled with the wider socio-economic impacts brought by energy systems, it can be said that socially sustainable energy systems also contribute to lifting individuals and communities out of poverty [

55,

160].

3.2.3. Health and Safety

Health and safety are fundamental aspects of the social sustainability of energy systems, intersecting with various dimensions of social development, well-being [

80], and quality of life [

98], as previously mentioned. Across several studies, there is a consistent call to address health concerns as integral components of social sustainability in the context of energy systems [

55,

64,

80,

83,

98,

107,

116,

160,

164,

180].

In rural electrification projects, as outlined by Assefa et al. [

163] and Juanpera et al. [

164], the establishment of energy systems facilitates access to vital health services, further proving the vital role of energy in improving public health.

Alongside health considerations, several authors advocate prioritizing safety within energy systems [

55,

73,

80]. As emphasized by Fedorova et al. [

80], safety not only impacts individual well-being but also influences broader societal well-being.

In a broader scope, socially sustainable energy systems are expected to contribute to the overall improvement of society’s living environment [

50,

80]. Additionally, as highlighted by Wilkens et al. [

105], evaluating social sustainability encompasses factors such as the impact on personal and local environments, reflecting the interconnection between energy systems and community well-being.

Lastly, it is essential to recognize the broader environmental implications of energy systems that are related to health and safety. For instance, the type of energy systems directly affects indoor and air pollution [

107,

160], as well as determines how much the system can contribute to global warming [

107].

3.2.4. Energy Access and Reliability

A significant portion of the literature under this theme highlights the fundamental role of energy access [

51,

103,

111,

119,

127,

129,

136,

137]. However, some articles delve deeper into this concept. For instance, the social aspect of an energy system is attributed to the right of consumers to energy access [

137]. Meanwhile, others underscore the importance of ensuring that this access to energy must be delivered in an equitable, affordable, and reliable manner [

51,

111]. Moreover, several authors argue that energy access facilitates other social benefits, including employment opportunities [

129], enhancements in an individual’s quality of life [

136], and improved access to essential services such as water [

84].

Alongside access, discussions about energy access and social sustainability often extend to reliability [

38,

51,

73,

151], as previously mentioned, and to energy security [

151].

3.2.5. Social Acceptance

Public perception and social acceptance play a critical role in the success of sustainable development projects, particularly those involving energy systems. Effectively addressing concerns and garnering support from different stakeholders are essential for overcoming barriers to implementation. The most widely used term is “social acceptance” [

38,

80,

112,

137,

154], but other terms have been used: public acceptance [

74] and community acceptance [

84].

Notably, measuring social acceptance poses challenges, specifically in terms of cultural values as well as stakeholder perception and opinion [

80]. Previous studies have equated social sustainability with stakeholders’ perceptions [

100,

105] or preferences [

100], but it can also be ultimately aligned with societal preferences [

90].

Ultimately, the study of social acceptance can be linked to other aspects of social sustainability, specifically the quantifiable ones such as job creation, access to energy, and economic growth. But it is also influenced by context-specific and subjective aspects such as preservation of cultural preservation, visual aesthetics, and well-being.

3.2.6. Social Equity

The majority of articles within the social equity theme emphasize the importance of equity [

71,

83,

85,

98,

161,

163,

164] and addressing social disparities [

85,

127] as key issues that energy systems can help mitigate. However, in the work of Lillo et al. [

180], energy systems are not directly presented as solutions to equity issues; rather, it underscores the necessity of addressing these disparities when introducing such systems, especially in rural contexts. Finally, as previously highlighted, there is an overlap between the themes of social sustainability and socio-economic impacts, which is particularly evident in the context of poverty alleviation [

55,

160].

3.2.7. Education

The availability of energy systems is central to education primarily because energy availability enhances educational opportunities and reduces illiteracy by facilitating better access to education [

160,

164]. This theme does not have an in-depth discussion compared to other themes since the previous literature mainly espouses the idea that energy systems are means to improve society through education [

46,

64,

74,

80,

103,

160,

163,

164,

180]

3.2.8. Involvement and Governance

The theme of involvement and governance is primarily derived from the notion that microgrids are rooted in social structures, because they comprise decentralized socio-technical networks that foster a community characterized by significant interaction among its participants [

136]. This can be applicable at different scales of energy systems, but the complexity between participant interactions can be greater in larger-scale systems and more manageable in smaller-scale systems.

As such, this theme corresponds to the nature of involvement among different stakeholders in the development and eventual operations of energy systems. This can be accomplished through open and participatory practices [

73,

170] in order to solicit the opinions and perceptions of stakeholders [

48]. By involving stakeholders, particularly end-users, the concept of empowerment can be fulfilled [

164]. More broadly, this theme also relates to the compatibility of the energy system with societal infrastructure, specifically in politics and governance [

50].

3.2.9. Gender

Despite gender gaining attention in the research sphere in recent decades, few articles included in this review have explicitly integrated gender and gender equity with the concept of social sustainability [

160,

163,

180]. However, a specific literature search using the terms gender and energy produces numerous recent articles concerning these topics. For example, a recent study explored how female labor participation is impacted by energy access and availability in developing countries [

181].

3.2.10. Human Rights

The “human rights” theme recognizes that socially sustainable energy systems firstly promulgate people’s right to have access to energy [

137]. However, this theme also corresponds to energy systems’ obligations to other humanitarian and human rights issues [

73], such as the rights of indigenous and traditional communities to their lands as well as protecting society’s heritage in the cultural, historical, and archeological aspects [

39].

The discussion up to this point, and in reference to

Table 3, only considers the articles that have provided an explicit definition or contextualization of social sustainability. Even though most of the articles in this review did not have an explicit working definition of social sustainability, it can be implied that social sustainability aspects are reflected by the indicators chosen by the articles’ authors. As such,

Section 3.3, which focuses on indicators, will reflect an updated categorization of articles based on the social sustainability themes.

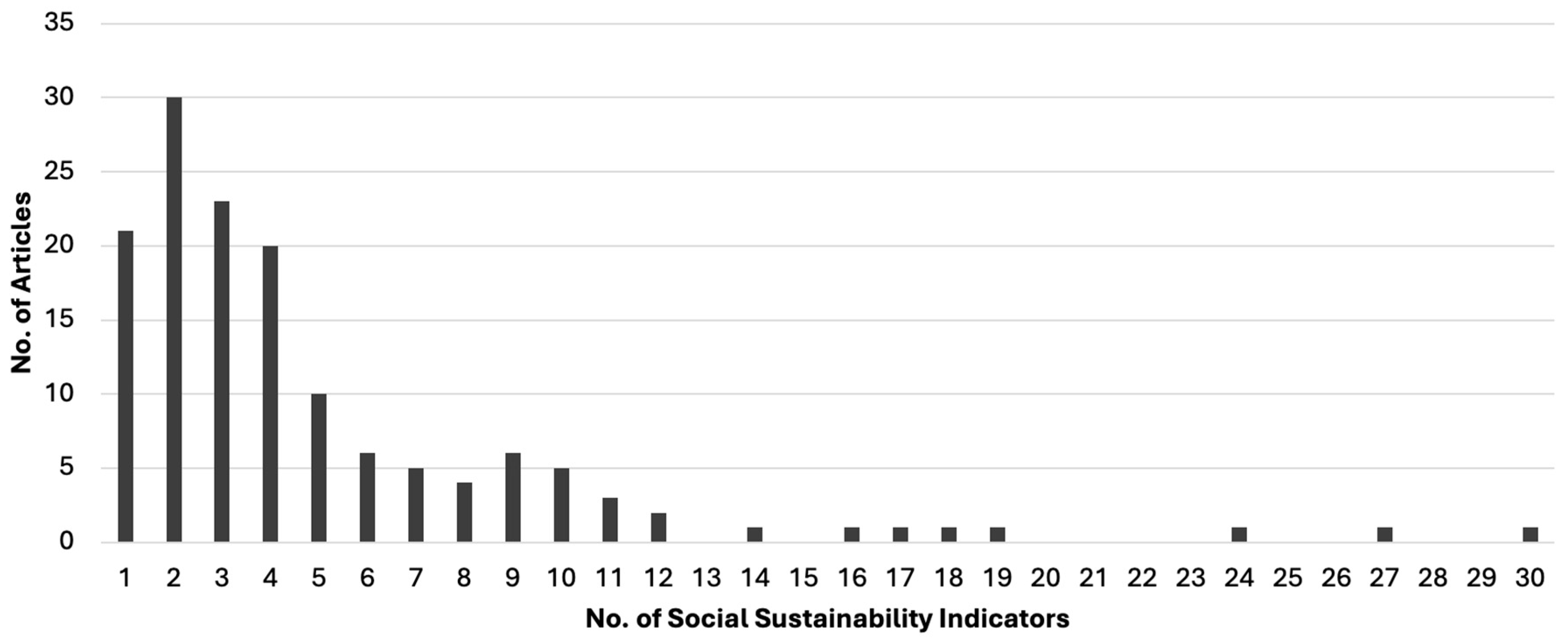

3.3. Social Sustainability Indicators

In this study, a total of 709 social sustainability indicators (SSIs) were identified from the pool of reviewed articles. The number of SSIs used in these articles range from as few as 1 indicator to as many as 30 indicators, as depicted in

Figure 7. On average, about five SSIs were used, although using two indicators was the most common among the reviewed articles.

For this research, the major categories for SSIs were based on the themes that have been identified in

Section 3.2. Sub-themes were also developed by the researchers to group indicators that cover similar characteristics.

Table 4 summarizes the number of indicators per theme and sub-theme.

The categorization of the indicators into themes and sub-themes was conducted to create a streamlined discussion and to allow readers to obtain a general sense of the types of indicators found in the literature. However, it should not be ignored that some of these indicators are context-specific. For example, the work of Terrapon-Pfaff et al. [

86] provided an extensive list of SSIs, but some of them are specifically addressed to the circumstances of their studied site, which is Morocco. Meanwhile, the indicators used by Khan [

1] are catered to developing countries. As such, when actual assessments are performed, proponents should also consider stakeholder inputs and other specific or unique circumstances.

When developing

Table 4, an indicator was allowed to be classified under two or more themes based on their description or how the authors defined them. Furthermore, themes and sub-themes can overlap in some aspects—for example, “pollution and emissions-related indicators” under the “health and safety” theme can be related to “surroundings, environment, ecosystems” sub-theme of the “social development, well-being, quality of life” theme. This suggests the multi-faceted nature of social sustainability and the challenge of defining and contextualizing the concept. Nonetheless, the themes and sub-themes provided here establish a starting point for stakeholders to identify potential social aspects to be considered when performing an energy system sustainability assessment.

Overall, similar to the themes based on explicit definitions discussed in

Section 3.2, the prominent themes based on the number of indicators are “socio-economic benefits and employment” and “social development, well-being, quality of life”, with 210 and 183 SSIs, respectively. These themes are followed by “health and safety”, “energy access and reliability”, and “social acceptance”. The “involvement and governance” theme surpasses the “social equity” theme based on the number of indicators.

Sub-themes mainly from the prominent themes have more indicators compared to other major themes. For example, job creation, economic benefits/economic-related, social welfare, surroundings/environment/ecosystems, labor- and plant-related safety, and energy access sub-themes have more indicators compared to social equity, education, gender, and human rights themes. This could signal the need to develop more indicators under the less-incorporated themes or to further standardize the indicators of these themes to ensure that they are more frequently used in sustainability assessments. A dedicated literature review covering these specific less-incorporated themes can be explored to expound the discussion.

Taking into account all individual indicators, the most used SSI in the pool of articles considered in this review was job creation, which essentially corresponds to the total number of jobs that an energy system employs. A total of 98 studies used this indicator to measure social sustainability. Other common terms for this indicator include employment, employment generation, and created jobs. There are also different ways to measure this indicator: total number of jobs [

55,

63], total number of jobs per generating capacity [

67,

95,

121], and total number of working hours per generating capacity [

117,

118,

123], among other variations. Although most studies have classified the job generation indicator under the social aspect, some studies [

39,

112] have classified it under the economic aspect.

In some cases, the social aspect is extended to include matters concerning culture and traditions [

85]. Others [

10] have treated the cultural aspect as an entirely separate sustainability pillar from the social aspect. As such, indicators that pertain to cultural sustainability were also identified and were treated separately from the social ones.

Section 3.2 previously discussed that, in the absence of an explicit definition of social sustainability, it can be assumed that the authors’ definition of the concept is reflected by the indicators that they use. Following this approach, the articles were categorized under the same themes as in

Section 3.2 based on the indicators they used.

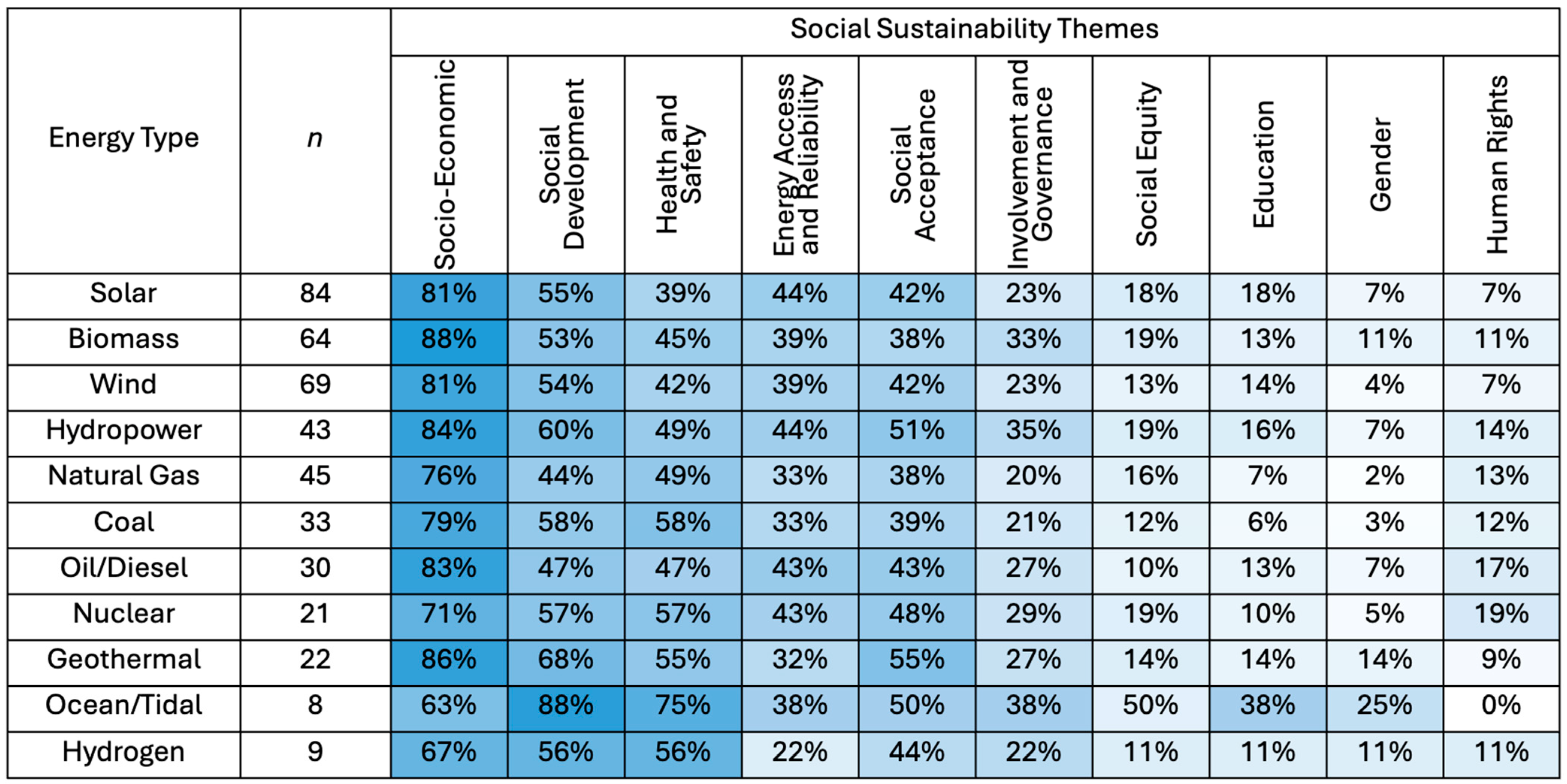

Table 5 summarizes the updated article count per theme.

Finally, a more comprehensive study about indicators in general is recommended. Such a study could cover the meanings (description) of the indicators, their data sources, methods/techniques/quantification/qualification, units of measurement, and criteria for inclusion.

3.4. Focus on the Social Sustainability Themes

Considering both the explicit definitions discussed in

Section 3.2 and the indicators discussed in

Section 3.3, there were minor adjustments to the article count per social sustainability theme. An article is considered to incorporate a theme as long as it either has an explicit definition or used an indicator that falls under the corresponding theme. The adjustments are reflected in

Table 6.

Ideally, the articles that provided definitions of social sustainability would have used indicators that correspond to the themes present in their definitions. However, this was not the case in a number of articles. For example, the definition provided by Assefa et al. [

163] incorporates social equity, education, involvement and governance, and gender; however, the main indicators used in the article fall primarily under the social acceptance theme. Meanwhile, the definition of Shakouri G. et al. [

38] attributes social sustainability to socio-economic benefits and employment, energy access and reliability, and social acceptance themes, but used job creation as the only indicator to measure social sustainability. On the other hand, some of the articles that provided definitions had indicators that fall under themes that were not present in the definitions.

Overall, the most prevalent themes remain as “socio-economic benefits and employment” and “social development, well-being, quality of life”. These are followed by “health and safety”, “energy access and reliability”, and “social acceptance”. The remaining themes may be considered minor themes if only article count is considered. However, this does not necessarily mean that they are less important with regards to their actual implications in practice.

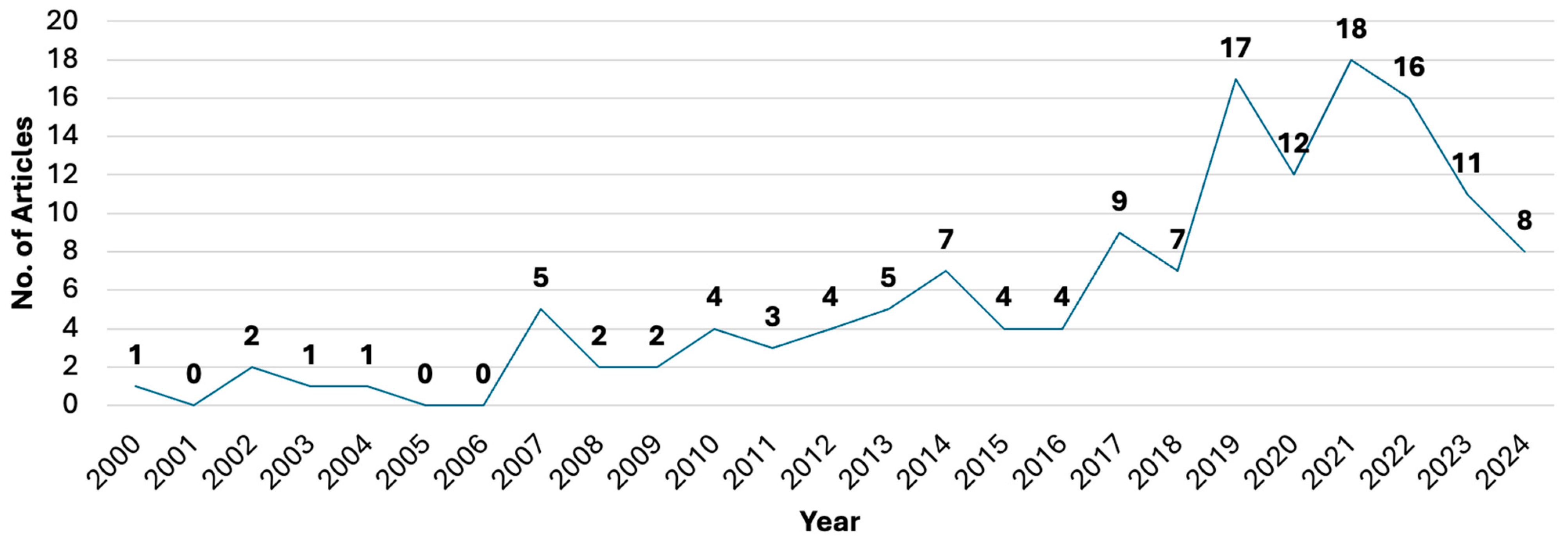

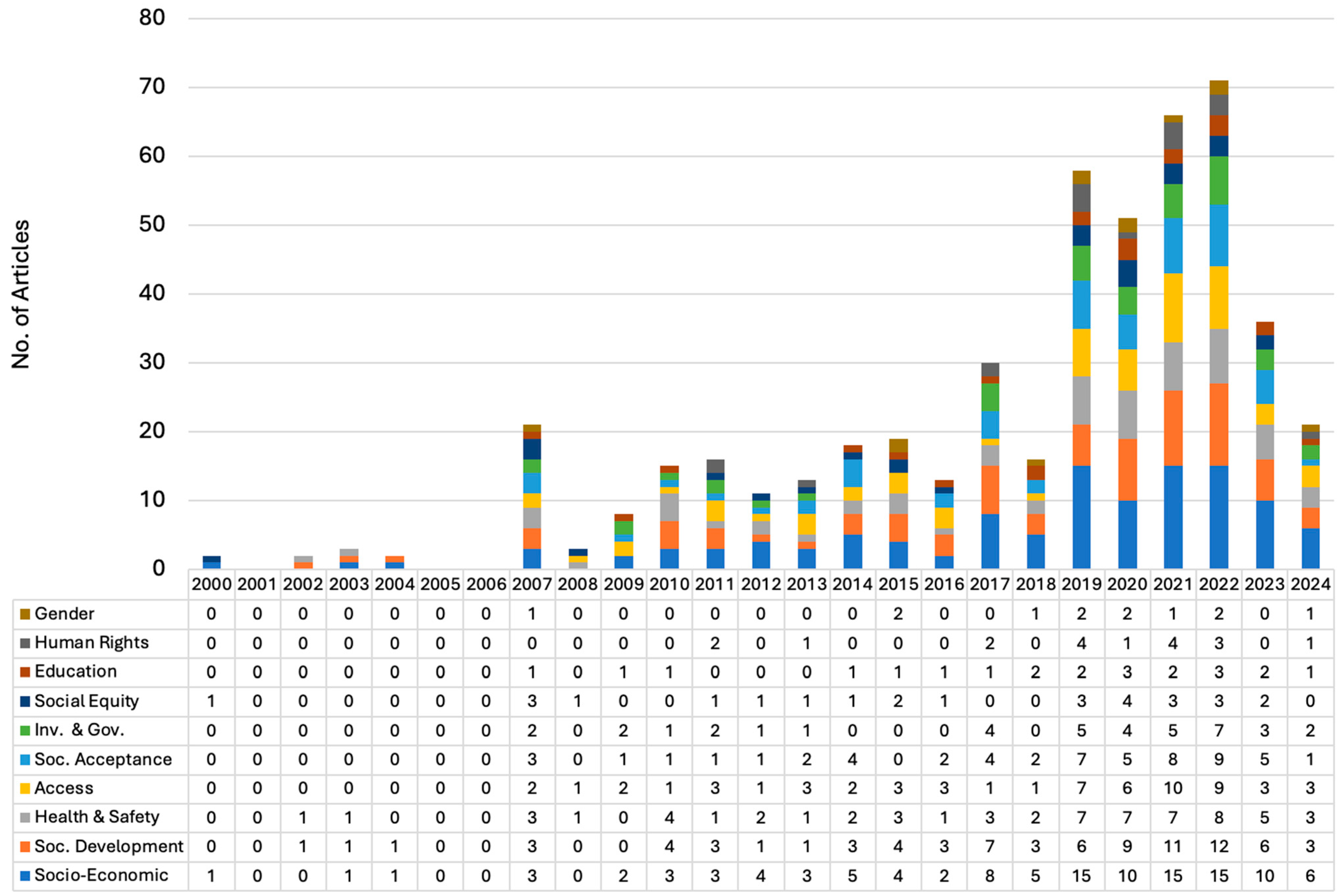

Analyzing the articles from a chronological perspective provides additional insights into the growth of each theme in terms of the number of articles incorporating them.

Figure 8 shows the annual number of studies that reflect different social sustainability themes, considering both the explicit and implicit definitions discussed in the previous sections. The themes of “socio-economic benefits and employment” and “social equity” were already present in the earlier studies considered in this review, specifically in 2000. This was followed by the themes of “social development, well-being, quality of life” and “health and safety” in studies appearing in 2002.

Most of the other themes—“energy access and reliability”, “social acceptance”, “involvement and governance”, “education”, and “gender”—appeared later (2007), while the theme of “human rights” emerged the most recently compared to other themes, in 2011.

A more focused view of each theme is represented in

Figure 9, which shows individual line charts of the number of articles reflecting each social sustainability theme. Based on these charts, it can be observed that the number of articles covering the themes of “socio-economic benefits and employment” and “social development, well-being, quality of life” generally have an upward trend since 2000.

Articles reflecting the theme of “health and safety” did not grow as much despite having appeared as early as 2000. Meanwhile, starting in the mid-2010s, more articles have started incorporating the themes of “energy access and reliability”, “social acceptance”, and “involvement and governance”. Generally, the number of articles covering the themes of “social equity”, “education”, “gender”, and “human rights” did not grow as significantly as the more predominant themes. As research on sustainability assessment of electricity generating systems progresses, it is expected that these themes will continue to be incorporated.

The discussion up to this point has primarily treated the themes as mutually exclusive facets of social sustainability. However, the multifaceted nature of social sustainability has been a recurring discussion in the previous literature and in earlier sections of this paper. As such, the co-occurrence of themes was investigated and is graphically shown on

Figure 10. The percentage shows the frequency of co-occurrence of the theme in the column relative to the number of articles that incorporated the theme in the row. For example, 80% of the 82 articles that incorporated “social development, well-being, quality of life” have also employed “socio-economic benefits and employment”.

Across all themes, “socio-economic benefits and employment” and “social development, well-being, quality of life” are the themes that were co-incorporated with the other themes. This complements earlier findings that the two themes were the most prominent. Furthermore, it also suggests two possible implications: first, other themes hinge upon the said themes. Another is that the two themes have been studied more frequently, resulting in more indicators and a frequent appearance in sustainability assessments. Future social sustainability assessments of energy systems can also benefit from including less incorporated aspects, such as social equity, education, gender, and human rights. Doing so can help make the assessments more holistic.

Meanwhile,

Figure 11 serves as an attempt to synthesize these facets, illustrating their interconnectedness and the simple relationships they form.

Firstly, energy access is an essential driver of social sustainability since it allows for the realization of other social benefits and impacts. However, considering a life cycle perspective requires incorporating other social sustainability themes at earlier stages of the energy system. For instance, ensuring health and safety during the system’s construction must be ensured. Moreover, involvement of different stakeholders during the planning phase can significantly contribute to the long-term success of the energy system, as they have more ownership of the system. Simultaneously, adhering to existing administrative and political frameworks is crucial for ensuring legitimacy and securing institutional support. Meanwhile, gender empowerment and human rights issues must also be considered prior to the establishment of energy systems to ensure respecting all who might be involved.

Once energy becomes accessible to society, a variety of benefits can be realized, particularly in terms of social development and socio-economic growth. This is supported by the number of indicators that have been used which relate to these themes. Additionally, energy availability facilitates improved access to essential social services such as health and education. Access can also play a vital role in addressing social inequities and gender disparities. From the inception to disposal or decommissioning of electrification systems, considerations of involvement and governance, as well as human rights, must be upheld to ensure holistic adherence to social sustainability principles.

Figure 11 also highlights the current prominence of socio-economic benefits and employment along with social development, well-being, and quality of life as the major themes that represent social sustainability. Although these two themes are the most incorporated, the bi-directional arrows represent that these themes connect and exist simultaneously with other themes.

Ultimately, these net social benefits shape the social acceptance of energy systems. This level of acceptance—or opposition—eventually significantly influences the success of future electrification projects. Thus, understanding and addressing social dimensions are imperative for fostering widespread acceptance and ensuring the efficacy of these initiatives.

Although it is ideal to incorporate all social sustainability themes when conducting an assessment of an energy system, the decision can be influenced by the interests of different stakeholders. In particular, the stakeholders can direct the criteria considered in the sustainability assessment and dictate how these criteria match each other. The roles of stakeholder are discussed more thoroughly in the next subsection.

3.5. Stakeholder Roles and Nature of Involvement

Stakeholders correspond to the actors that are directly or indirectly involved in electrification systems throughout their life cycle. In this research, stakeholders were classified into seven major groups: industry experts, academics, government, end-users/public, non-government organizations and community groups, suppliers, and private companies. These terms were taken directly from the articles and merged for similarities. The following list provides a brief description for each stakeholder group:

Industry experts are individuals who were involved specifically because they have extensive experience in various fields; for example, in the energy sector [

41,

58], specific energy technologies [

43,

50,

159], or sustainability or life cycle assessments [

43,

89,

92]. These stakeholders are usually drawn from other categories, such as government or academia. When an article provides a description or profile that clearly identifies the background of the stakeholder, the stakeholder was categorized to the appropriate group (e.g., if stakeholder ABC comes from University XYZ, then the stakeholder will be assigned to the academic group);

Academic stakeholders are people who are currently employed at universities or research institutes and also provide specific expertise related to the sustainability assessment [

46,

85,

113];

Government stakeholders are representatives from different government agencies or offices, such as environmental ministries [

52,

65,

95], energy ministries [

54,

165], or local government units [

56,

68,

106];

End-users/public are the primary recipients of the energy systems; they are usually the consumers of the energy produced by the system and/or those who live within the approximate vicinity of the energy system [

105,

165,

180];

Non-government organizations (NGOs), civil society organizations, and community groups are associations that usually represent or advocate environmental [

61,

154,

173], labor-related [

40], or humanitarian causes [

68,

173];

Suppliers are actors along the supply chain, specifically those who are from the trade industry or those that provide or manufacture technologies or fuel [

57,

61,

105];

Private companies are those who participate in energy projects through corporate social responsibility mandates or by providing financial assistance to enact such projects [

40,

80,

95].

The full-text investigation of the 143 articles included in this review reveals that the article pool is divided almost evenly, with 73 articles involving stakeholders, and with the remaining 70 articles not involving stakeholders. Involvement of stakeholders means that the authors of the articles specified that they have invited persons outside of the authors pool or research team to solicit assistance for the sustainability assessment. The nature of this assistance is also discussed in this subsection.

In this study, no attempt was made to investigate the reasons other articles did not involve stakeholders. Additionally, studies of this type often referred to the findings of other studies in terms of criteria selection, weight assignments, or indicator valuations.

Overall, industry experts, academics, and representatives of the government have been the most involved stakeholders in the reviewed articles. The involvement of these stakeholder groups is expected as they have more knowledge in the different operations along the life cycle of an energy system as well as in the field of sustainability assessments. They also have technical expertise that allows them to provide information regarding certain features of energy systems and, eventually, to evaluate system alternatives.

The remaining stakeholder groups, namely the end-users/public, NGOs, suppliers, and private companies were involved to a lesser extent. Meanwhile, eight studies did not explicitly disclose the backgrounds of the stakeholders involved in their respective studies.

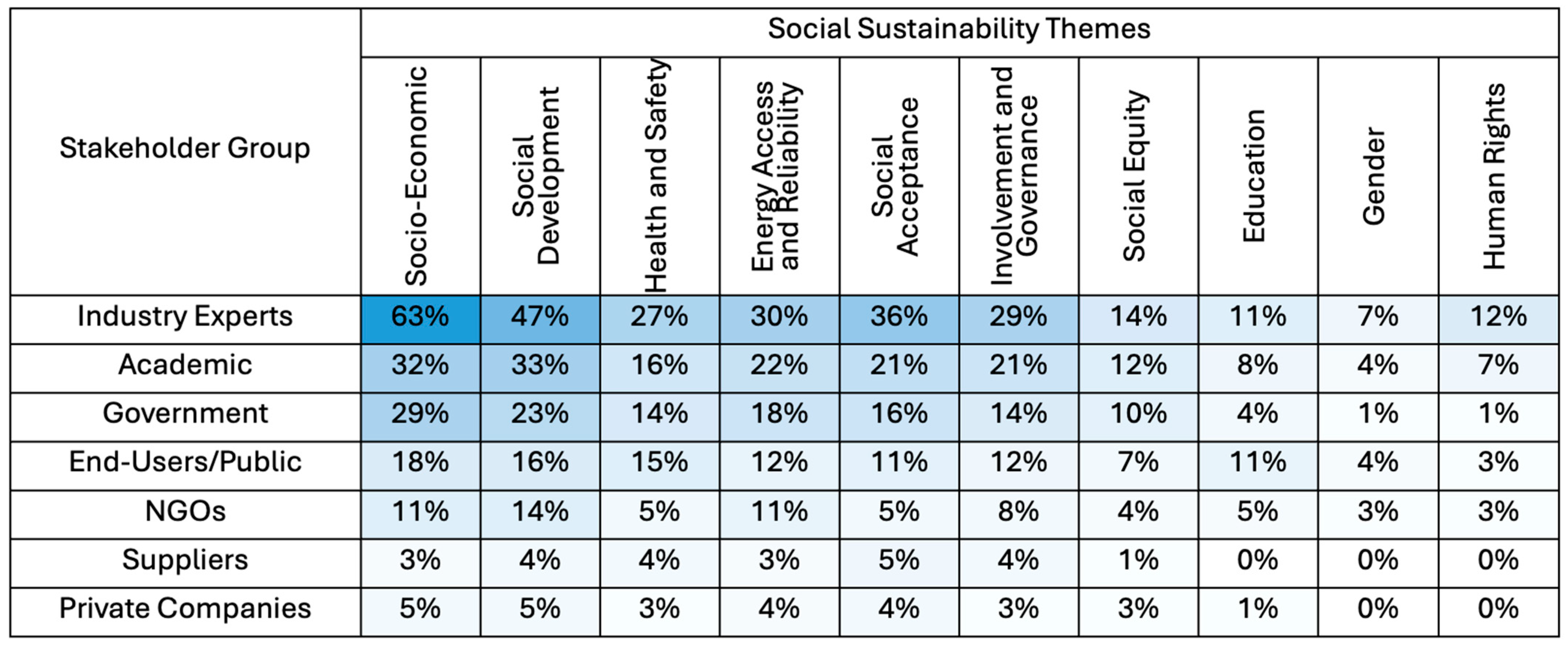

Table 7 shows the number of articles involving the different stakeholder groups (a study can involve multiple stakeholder groups).

In terms of the nature of involvement, stakeholders were primarily involved in four major ways, as outlined in

Table 8. Predominantly, their involvement centered around assessing energy system options or assigning values to sustainability indicators. Moreover, they were also usually involved in developing or selecting the sustainability criteria, alongside assigning relative weights to these criteria. A smaller subset of studies engaged stakeholders in additional aspects of research, such as validating assumptions, crafting scenarios, and coordinating on-site activities.

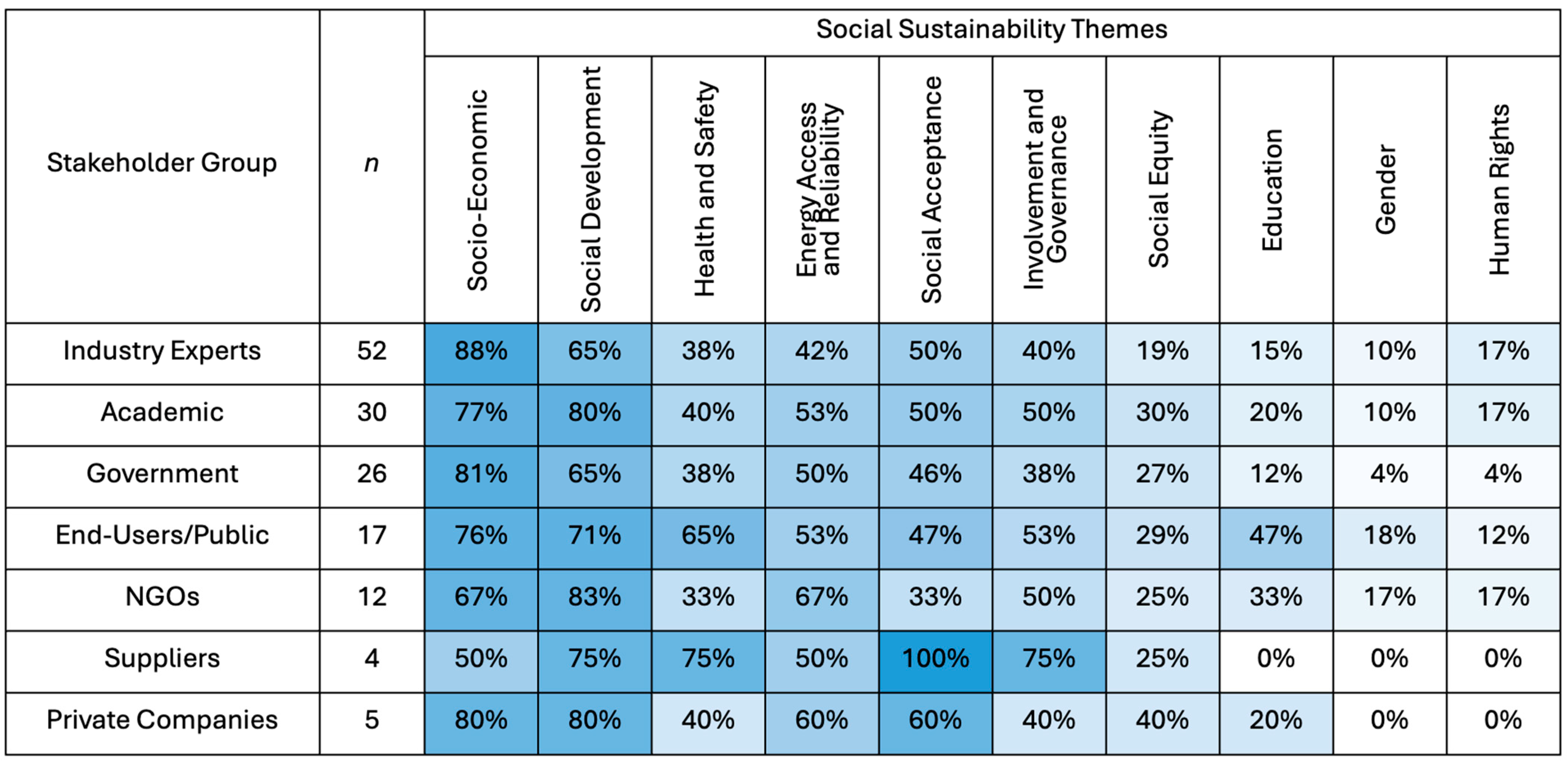

To clarify the understanding of the specific nature of how each stakeholder group participated in the assessment, this research attempted to cross-tabulate each stakeholder group with respect to the specific activity categories.

Table 9 and

Table 10 summarize the level of involvement of each stakeholder group across the four primary involvement categories discussed earlier.

Table 9 and

Table 10, respectively, depict percentages relative to the total number of studies covering different involvement categories and the total number of studies involving different stakeholder groups.

However, it is important to note that the values presented are only approximations since not all articles included in this study provided clear or transparent indications of the extent and manner of involvement for each stakeholder group. The assumption was made that an article involved all mentioned stakeholders in all described activities unless explicitly stated otherwise. For future studies, it is advisable to provide explicit clarification on how each stakeholder group was engaged, especially concerning activities related to the social aspect of sustainability assessment. This transparency would enhance the accuracy and reliability of the findings.

Referring to

Table 9, it can be seen that across all natures of involvement, industry experts are the primarily involved stakeholder group, followed by representatives from academics and the government. End-users/public and NGOs were involved to a lesser extent when developing or selecting criteria. While NGOs are more involved in evaluating alternatives or assigning values to sustainability indicators, the end-users/public were more involved in auxiliary assessment activities such as providing data or other necessary information. Generally, suppliers and private companies were the least involved across all major assessment activities.

Meanwhile, from the perspective of the number of studies involving each stakeholder group, as shown in

Table 10, stakeholders are more often involved in developing or selecting criteria as well as the evaluation of alternatives or assigning values to indicators. That is, if a certain stakeholder group was involved, they are more likely to assist in developing sustainability criteria. Overall, industry experts, academics, and government representatives were more involved in the evaluation of alternatives, but slightly less involved when it comes to assigning weight to these criteria—complementing the insights from

Table 9.

To involve stakeholders, previous studies have mainly implemented surveys or questionnaires [

39,

61,

92,

95,

113,

128] and interviews [

41,

50,

87,

152,

154]. These methods were used primarily for stakeholders to convey which criteria were most relevant as well as to assign weights to these criteria. Focus group discussions [

86,

90,

112,

121] and workshops [

68,

80,

83,

105] were employed less frequently. These methods were used to gather more qualitative information and were useful when developing scenarios or formulating assumptions.

There were few studies that used more specific methods, such as the Delphi method [

136] and discrete choice experiment [

90]. All in all, there were 22 articles that were unclear about the method used to involve stakeholders; these articles simply indicated “participatory process” or similarly non-specific methods. A complete picture of the manner of involvement is presented in tabular form in

Supplementary Material File S1.