Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the key characteristics for the sample energy companies and illustrates the diversity that exists between them. It depicts the average number of employees in the sample for the entire period, indicating an overall average of 21,448 employees, with the highest average recorded in 2019. The lowest number of employees was documented at Verbund in 2018 with 2742, while the highest level was observed at E.ON in 2019 with 78,948. On an annual basis, the highest average revenue among the monitored companies was achieved in 2017, with the lowest total revenue in 2017 at Vattenfall with EUR 13,746 million. Conversely, the highest total revenue was recorded at Enel in 2019, at EUR 80,327 million. The average total assets of all companies observed amounted to EUR 31,184,955 million. Notably, the average values for the total number of employees, total revenue, and total assets exhibited a declining trend over the observed period.

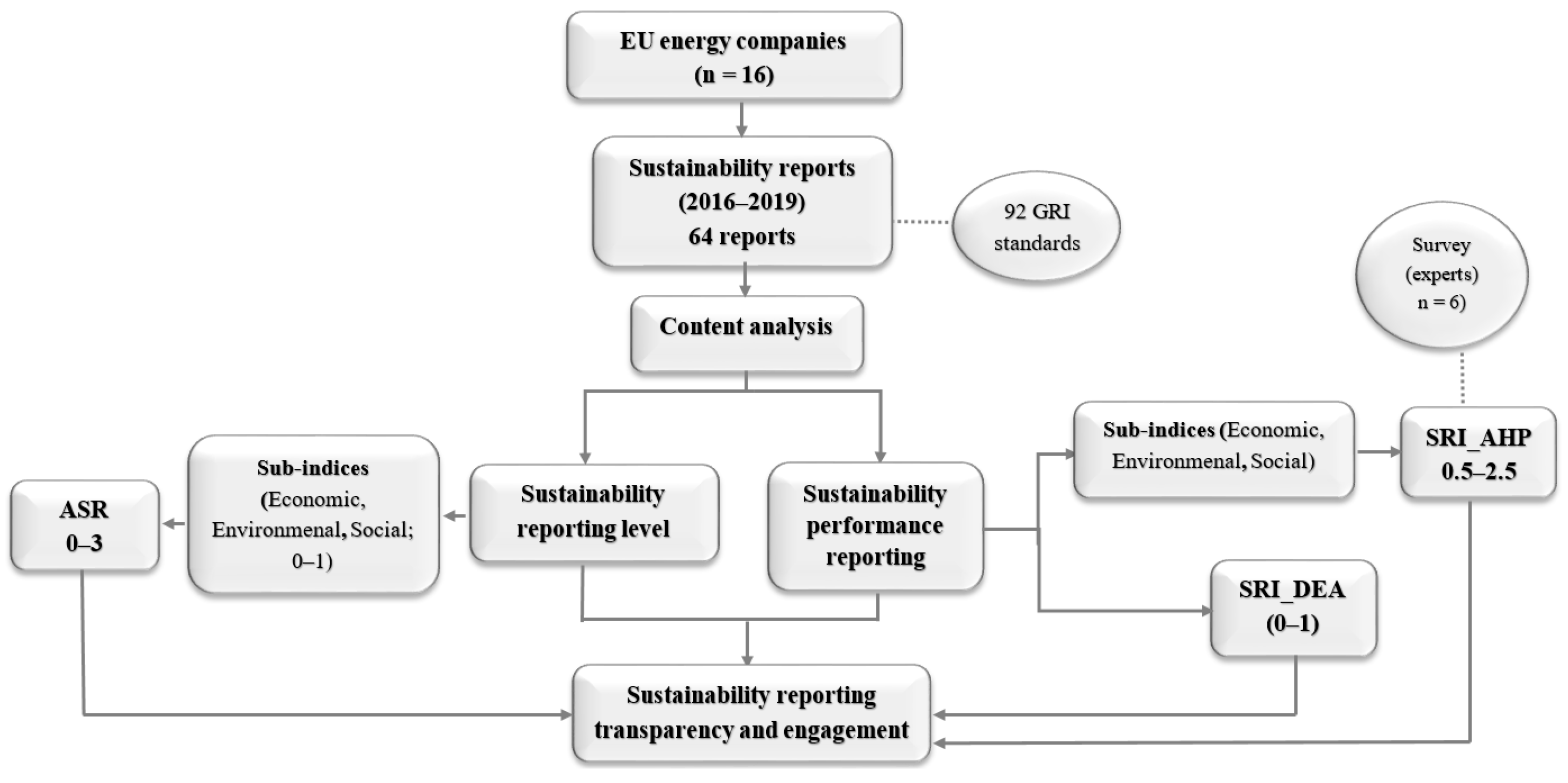

Three metrics were developed to assess the level of transparency and engagement displayed by energy companies in their sustainability reporting.

4.1. Sustainability Reporting Level in Energy Companies

Based on the methodology presented above, the ASR score was calculated for each company and the energy sector as a whole, for each year, considering each sustainability dimension (economic, environmental, and social). The corresponding ASR values are presented in

Table 2.

The reliability of the ASR score was found to be good, with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.923, indicating that the sustainability reporting sub-indices consistently measured this construct. The highest ASR score of 2.69 was achieved by Endesa in 2019, while the lowest value of 0.48 was obtained by E.ON in 2018. The industry average for the ASR scores was narrow, ranging from 1.40 to 1.45, which indicated not only a low level of reporting (with a maximum score of 3), but also stagnation in sustainability reporting. This observation was also supported by the results of the dependent

t-tests, where the

p-value was greater than 0.1, indicating that there was no difference in sustainability reporting before and after the introduction of the legal obligations, as well as during their implementation. However, there are contradictory findings in the literature regarding the impact of such regulations on sustainability reporting. While some studies reported favorable effects [

18], others reported unfavorable effects [

19,

55], suggesting the contextual dependence of the regulation’s impact.

The analysis of the sustainability reporting levels enabled the classification of energy companies into three trend categories: growth/decline (>±1.5%: 8 and 6 companies, respectively) and stagnation (<±1.5%; 2 companies), as presented in

Table 2. During the observed period, ESB achieved the highest increase in reporting level, while Innogy experienced the largest decrease. The significant changes in these companies are due to shifts in the number of indicators reported in the companies’ sustainability reports. ESB has notably expanded its reporting, with the number of environmental indicators rising from 9 (2016) to 20 (2019) and social indicators from 5 (2016) to 14 (2019). Conversely, Innogy significantly reduced its reported indicators, particularly the environmental indicators from 15 (2016) to 9 (2019) of 35 possible indicators and the economic indicators from 7 (2016) to 3 (2019) of a total of 13 possible indicators. EDP had the highest reporting level (average 2.63), and interestingly, the reporting level remained consistent throughout the period. Notably, some companies consistently reported above or below the industry average, indicating consistent reporting practices over time. However, more companies with above-average sustainability reporting scores experienced a decline in reporting levels over the observed period compared to those that experienced growth. This could be a sign of a movement towards a consensus on sustainability reporting practices (see [

55] for discussion), which may contribute to consistency [

39] and credibility [

45] of reporting. Similar observations were made for individual sustainability dimensions. However, achieving consistency in sustainability reporting requires standardization at a higher level of reporting.

Table 2 presents the classification of energy companies into four groups based on their average reporting level (high, medium, low, and very low), with each level corresponding to a quantile range of 25%. The companies with a high reporting level were EDP, Endesa, Enel, and HEP, while SSE, PGE, Vattenfall, and E.ON had a very low reporting level. It is noteworthy that EDP had both the highest reporting level and the highest level in each sub-index of sustainability, achieving the maximum score in the economic dimension. The table also shows that companies generally reported the most on the economic dimension of sustainability, while the social dimension was the least represented, despite the number of GRI Standards available for reporting. This discrepancy has been observed in previous studies regardless of country or industry [

14,

34,

39], and could be due to companies’ profit orientation (they are profit-driven and therefore prioritize the economic dimension, which is directly related to financial performance) and their perception of stakeholder expectations (they may perceive that their stakeholders, such as investors, are more interested in their financial performance). The results of the paired sample

t-test confirmed statistically significant differences between the mean values of the fractions for the sub-measures of sustainability reporting level.

The ASR values, ranging from 0.48 to 2.69, indicate that while all companies are complying with their reporting obligations, there is still considerable room for improvement in their reporting practices to the public.

In the field of energy reporting, there are both desirable and undesirable indicators. This study revealed that companies generally prioritize reporting on desirable indicators, such as employee training and board and workforce diversity, while often avoiding detailed reporting on undesirable indicators such as workplace injuries, corruption, and harmful gas emissions. However, energy companies are expected to increase their efforts to strengthen social responsibility and reduce undesirable environmental indicators, especially given their role as major polluters with ever-increasing emissions.

We anticipated an unsatisfactory environmental performance, offset by other dimensions, especially the economic one. These expectations align with the fact that energy companies contribute to three-quarters of all CO

2 emissions [

63]. It seems that emphasizing compensation in the economic dimension serves as a strategic move to avoid penalties, preserve reputation, and maintain positive relationships with stakeholders, especially investors. Thus, our findings suggest that it may not be advisable for companies to voluntarily choose reporting standards due to the potential for manipulation and the need for standardization given the specificities of the sector. Directive 2014/95/EU underlines the importance of standardization to ensure access to all essential sustainability information [

64].

4.2. Sustainability Performance Reporting in Energy Companies

To enable a more comprehensive and accurate assessment of sustainability practices in the energy industry, two sustainability performance reporting indices were constructed. The first index is based on the AHP method, while the second one is based on the DEA method. The combination of these two methods provides a more robust evaluation of sustainability performance, taking into account both subjective and objective factors.

SRI_AHP. The content analysis identified categories of quantitative indicators that were present in more than 50% of the sustainability reports, resulting in a total of 13 indicator categories: 3 economic, 6 environmental, and 4 social (see

Table A2 in the

Appendix A). These indicators were then reviewed by experts to determine their importance or weight. Based on the expert opinions, a consolidated pairwise comparison matrix was created for the selected indicator categories and sustainability dimensions. It is worth noting that the expert opinions were consistent, as supported by the consistency ratio. Specifically, the consistency ratio was 3.9%, 2.9%, and 0.5% for the economic, environmental, and social dimensions, respectively, which is well below the acceptable upper limit of 0.1 or 10%. The indicator categories that received the highest AHP importance weighting were anti-corruption (205; 47.88%) for the economic dimension, emissions (305; 23.36%) for the environmental dimension, and health and safety at work (403; 36.81%) for the social dimension. Specifically, the most frequently reported economic indicator was confirmed cases of corruption and actions taken (205–3) at 70%, while the most frequently reported environmental indicator was direct (Scope 1) GHG emissions (305–1) at 100%. For the social dimension, the most frequently reported indicator was work-related injuries ((403–2 (2016), 403–9 (2018)) at 100%. Most of the energy companies in the sample are either wholly or partly owned by the state (see [

65]), which could be a factor in their efforts to present themselves as socially responsible and environmentally conscious to their stakeholders. According to stakeholder theory, government ownership can have a positive impact on sustainability reporting [

17], which has been demonstrated in the energy industry by [

37]. Notably, emissions were the most commonly reported environmental GRI Standard, which was likely due to the continued emphasis on sustainability in the EU. Additionally, Avram et al. [

39] found that energy companies are generally more concerned about the environment than companies in less environmentally sensitive industries. Other studies showed that the importance of image and credibility in sustainability reporting can vary from industry to industry [

55] and that environmentally sensitive industries are more inclined to disclose their sustainability practices and information in sustainability reports to improve their credibility and transparency [

66].

Using the methodology described in the previous section, the SRI_AHP scores were calculated for each company, each year, and for each sustainability dimension. The industry average was also calculated (

Table 3).

The SRI_AHP scores ranged from 0.50 to 0.77. However, energy company sustainability performance reporting stagnated at the industry level during the observed period, as confirmed by the paired samples

t-test (

p > 0.1), suggesting that these energy companies followed the existing sustainability reporting practices, similar to many European companies (see [

18]. This is consistent with the perspective of institutional theory, which emphasizes the importance of the institutional framework for the quality of sustainability reporting (see [

55]). In addition, previous research has found that energy companies are reporting more information in their sustainability reports every year [

67], choosing between reactive and proactive sustainability strategies to manage various sustainability responsibilities that go beyond legal and environmental compliance [

68], producing higher-quality sustainability reports, and are less responsive to regulatory changes [

55].

To gain insight into the progress made in reporting sustainability performance at the company level, the companies were categorized into three groups: companies with growth (HEP, PPC, Latvenergo, E.ON, and Endesa), decline (PGE, Verbund, Enel, Innogy, ČEZ, Fortum, MVM, and SSE), and stagnation (EDP, ESB, and Vattenfall). Enel and EDP had the highest level of sustainability performance reporting, while Latvenergo had the lowest SRI_AHP score in the observed period. Similar to the ASR scores, the analysis revealed a decline in sustainability performance reporting for companies that had previously had above-average reported, and this trend was consistent across the individual sustainability dimensions. Notably, reporting on the economic dimension was the most comprehensive, while reporting on the environmental and social dimensions showed no statistically significant difference (

p < 0.001). Sartori et al. [

44] reported similar results in the Brazilian electricity industry, where economic indicators dominated the GRI reports, and only two companies disclosed more than 70% of the indicators related to sustainability issues. These results are consistent with the other studies mentioned in

Section 4.1. Therefore, it is crucial to place more emphasis on environmental and social indicators [

43] to improve sustainable performance [

14,

19].

The categorization of sustainability performance was based on the same percentile approach as for the ASR scores.

Table 3 indicates that companies with a medium level of sustainability performance reporting showed a decreasing trend in reporting, while companies with the lowest level generally showed an increasing trend. It is important to note that all companies can still improve sustainability performance reporting, as the maximum value of the index is 1.0.

SRI_DEA. The SRI_DEA was calculated using the BCC DEA method with VRS, using input and output data published in 75% or more of the sustainability reports (codes 302-1, 305-1, 305-2, 305-3, 305-7, 403-2, 403-9, and 405-1; see

Table A3). This was performed for two reasons: first, to construct a measure based on indicators that the energy companies themselves recognize as the most important, and second, to minimize the number of variables in the DEA model, as a large number of variables makes it difficult to differentiate sustainability performance [

35]. Two emission indicators (tCO2) were selected as output variables, which represent the total sum of all emissions produced (305-1, 305-2, 305-3, and 305-7) and the number of work-related injuries, which is also the sum of two individual indicators (403-2 and 403-9).

Total revenue (EUR), energy consumption within the organization (GJ), and the diversity of governance bodies and employees (405-1) were selected as input variables.

Table 4 shows these results.

Five companies (HEP, Innogy, Latvenergo, PGE, and Vatenfall) operated efficiently with an SRI_DEA score of 1. However, the remaining companies were classified as inefficient and were categorized as medium, low, and very low. EDP was identified as the least efficient of all the companies throughout the observation period. It is noteworthy that all inefficient companies (68.75%) had the potential to operate at the efficiency frontier. Other studies also pointed out the lower sustainable efficiency of energy companies [

35] and emphasized the need to invest in emission mitigation measures [

61].

Looking at the values year to year, they ranged between 0.71 and 0.84, showing an increasing trend. However, the paired-samples t-test revealed that the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.1), indicating that there was no significant change in the sustainability levels during the observation period, despite institutional pressure.

4.3. Relationship between Sustainability Reporting and Sustainability Performance in Business

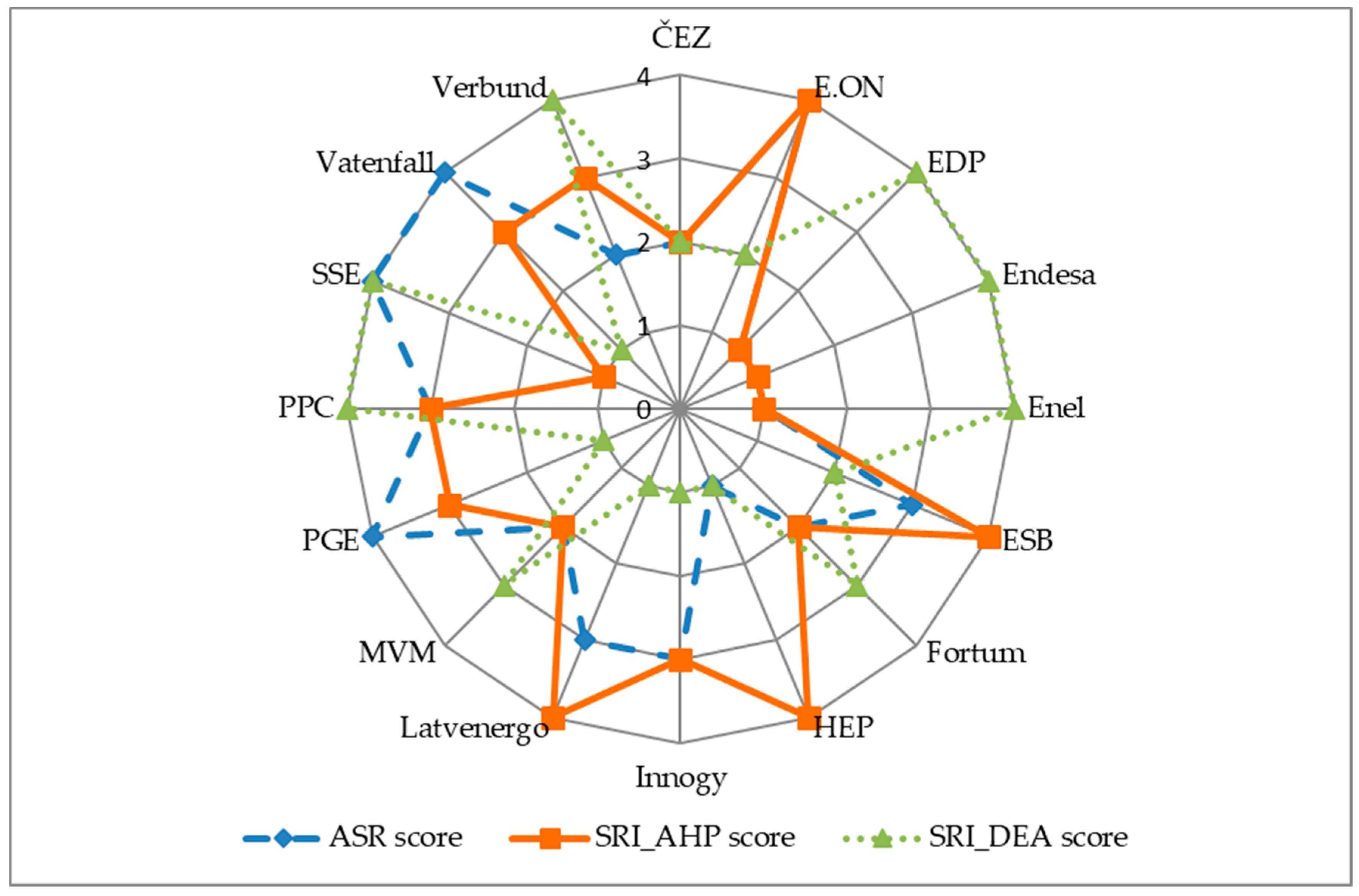

The analysis of the effect of the established level of sustainability reporting and reporting on the sustainability performance of energy companies for each year observed provides insights into their transparency and engagement in sustainability reporting. Notably, the study found statistically significant differences in the scores of all constructed measures of corporate sustainability reporting, including ASR and SRI_AHP (t = 10.229, df = 63,

p < 0.05), ASR and SRI_DEA (t = 6.272, df = 63,

p < 0.05), and SRI_AHP and SRI_DEA (t = −3.755, df = 63,

p < 0.05). The results are shown visually in

Figure 2 and are based on

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4.

The results of the study indicate that the sustainability reporting and sustainability performance of all energy companies differed significantly, with the exception of ČEZ, which consistently reported at a medium level in all three measures. For the majority of companies (9), the level of sustainability reporting was the same when comparing the ASR and SRI_AHP scores. However, there were two scenarios in which ASR > SRI_AHP (PGE, SSE, and Vattenfall) and in which ASR < SRI_AHP (ESB, HEP, Latvenergo, and Verbund). Additionally, for all companies except ČEZ, there was a difference in the level of sustainability performance reporting when comparing the SRI_AHP and SRI_DEA scores. The companies that were efficient according to the DEA method primarily had a lower level of sustainability performance reporting, and vice versa. The relationship between the level of sustainability reporting and performance reporting was further supported by the correlation coefficients shown in

Table 5. These coefficients not only measure the strength of the relationship but also indicate the degree of substitutability and compatibility.

The results show a significant positive correlation between the ASR and the SRI_AHP scores. This indicates that companies reporting a higher number of sustainability indicators (ASR score) have a higher level of sustainability performance (SRI_AHP). These findings are consistent with previous studies [

69,

70], which found that higher levels of sustainability reporting are associated with higher levels of corporate sustainability. In contrast, a statistically significant negative correlation was found between the ASR and the SRI_DEA scores as well as between the SRI_AHP and the SRI_DEA. This discrepancy resulted from differences in the methods used and the data selected. In particular, the SRI_DEA focuses exclusively on undesirable outputs, while the SRI_AHP considers both desirable and undesirable outputs.

Despite these differences, the ASR, SRI_AHP and SRI_DEA measures complemented each other and together improved the quality of sustainability reporting. As each measure reflects different aspects of sustainability performance, researchers can use them individually or in combination—depending on research objectives and data availability—to effectively assess sustainability performance.