1. Introduction

Energy Communities (ECs) are communities with energy resources, such as photovoltaic systems, micro-wind, bio-energy, and the consumption of its residents is controlled by its members. These new entities contribute to the energy transition towards a zero-gas emission system and enable people to be active users of the energy system. There are two types of ECs: Renewable Energy Communities (REC) and Citizen Energy Communities (CEC). Both terms have been defined by the European Directives in 2018 and 2019 [

1,

2].

The primary goal of ECs is to provide social, environmental and economic benefits to members and the community in which they operate. The European Directives allow these legal entities to participate in the electricity markets [

1,

2]. It is the responsibility of each member state to implement the legal framework effectively and practically so that ECs can participate in the electricity sector without discrimination and fulfill their obligations and rights [

3].

ECs are primarily driven by the active participation of citizens, empowering them to take control of both energy generation and consumption within the electricity system. This empowerment is anticipated to foster more engaged and responsible energy use among the population. Consequently, numerous studies have explored the potential social and environmental impacts of ECs on society [

4], with some focusing on their role in alleviating energy poverty [

5,

6]. Given their objectives and characteristics, ECs are also being considered for implementation in various countries, including Egypt [

7].

In addition to these impact studies, research has also highlighted the importance of creating inclusive and participatory environments for the successful implementation of ECs. For instance, ref. [

8] emphasized the role of energy cooperatives in fostering community engagement, noting that a strong local perception and sense of ownership are critical for these initiatives. Similarly, ref. [

9] conducted a comparative analysis of seven pilot EC projects across Europe—including Belgium, Spain, the Netherlands, and Greece—focusing on the design elements that contribute to the success of ECs. Their study, which employed a multi-criteria and multi-stakeholder approach, concluded that such methods are instrumental in helping stakeholders align their objectives.

The study in [

10] analyzes best practices for transferring the experience of multi-functional energy gardens from the Netherlands to Germany, serving as a potential model for ECs. These projects emphasize renewable and ecological approaches. The authors conclude that the success of such transfers relies heavily on active participation from local governments and communities, financial support, clear objectives, and strong commitment [

11]. Additionally, a favorable regulatory framework for energy sharing significantly aids the development of these initiatives. Other research, such as [

12], has focused on replicable strategies and trends, particularly in creating positive energy buildings and smart cities. The analysis of these strategies is not only of great societal interest but also crucial for understanding contextual adaptation.

In [

13], the authors provide a descriptive analysis of various ECs funded by European projects, along with case studies on their implementation. The evaluation centers on the primary operational strategies and identifies key European strategic policies. One of the barriers to EC development as highlighted by the authors is the challenging relationship between citizens and institutions. Moreover, technological advancements and national legislation often lag behind the implementation pace proposed by European directives.

The study in [

14] analyzes four pilot EC projects in the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, and the UK through interviews, focusing on member participation, management, and legal aspects. The findings suggest that further legislative efforts are necessary to ensure the successful operation of these community initiatives. Similarly, ref. [

15] identifies the best administrative, technical, and technological practices for developing REC within the Italian regulatory framework, emphasizing the need for strategies to attract stakeholders and underscore the importance of energy issues [

16,

17].

In [

18], the most effective strategies for achieving net-zero and positive ECs are outlined based on the findings of the Zero-Plus project. The case studies analyze cases in New York in the United States, Calgary in Canada, Granarolo dell’Emilia in Italy, and Cairo in Egypt. Among the study’s conclusions, the authors mention that these initiatives have focused more on the generation side than on demand reduction or efficiency improvements to reduce consumption, which requires new and better policies and management tools. In [

19], the authors analyze 24 case studies of ECs in different European countries, and identify different design options for ECs. They evaluate the cases using a morphological box, in which they analyze the cases in terms of their role in the value chain, support, geography, financial volume, and application in the sector. Among the conclusions, they underline that the participation schemes should be focused on the demand flexibility services that urban citizens organized in ECs could offer to the Distribution System Operators (DSOs).

Although some of the studies mentioned above present real cases of ECs, there is a gap in the literature to study the interaction of ECs in the energy market. ECs also open the door to the development of new energy technologies. In [

20], the authors study the best practices of Termoli REC in the city of Termoli, Italy, in which they highlight the technological design tool Enea. Enea’s strategy is to facilitate a development process starting from RECs considering energy exchange. Enea has created a digital framework to support ECs through the creation of tools and services, taking into account the evolution of the regulatory framework in Italy. Also, in [

21], the authors present an Energy Community Platform, a modular system designed for the smart monitoring of local ECs to encourage a more conscious energy use by users, and the Energy Community Tokenization Platform as part of the best practices within ECs. In [

22], the authors study the implementation of fifth-generation district heating and cooling and propose best practices for its implementation. In doing so, they refer to three business models of ECs: local energy markets, third-party sponsored communities, and community ESCO (energy service companies). This study focuses on Swedish district heating and cooling but can be applied to other contexts. Also in [

23], the implementation of the combination of collective investment and the P2P business model is advised.

Four cases of Dutch and German communities are studied in [

24] to identify the factors influencing the formation and development of RECs. The author concludes that he found no significant differences between the two countries, despite their different regulations and backgrounds, nor did he find urban or rural location to be an influential factor. However, he did find that there is a high level of investment in communities where citizens have a good and close relationship of trust, as well as the size of the community. In [

25], an analysis is conducted of the strategies some RECs have used to engage their members and enable them to save energy. In [

26], a study is made of the factors that facilitate and hinder the implementation of sustainable ECs, based on two case studies, one from Denmark and the other from Ireland. Among the conclusions, the authors mention the need to identify the key person of influence in the project as well as to interact with the community members.

As can be observed, these studies are based on sound practices in the functioning of the EC or the provision of technological tools that facilitate its development. Furthermore, some of the studies also concentrate on the membership practices of the community. Nevertheless, there is a lack of focus on the strategy of participation of the ECs in energy markets.

Unlike previous studies, our study focuses on identifying ECs that participate in energy and ancillary services markets and other energy services. ECs are expected to accelerate the decentralization and decarbonization of the electricity system; therefore, analyzing the current and expected future implementation cases helps predict the impact of these entities on the electricity systems.

Contribution and Organization

This study aims to answer the following questions:

What is the current participation of ECs in the electricity market?

What strategies are ECs using to participate in the electricity sector?

In what services are ECs expected to participate in real projects under development?

This article addresses the regulatory perspective of ECs in different countries, outlining the implementation strategies and lines of action or operation of real cases of ECs. It also presents ECs that aim to provide flexibility services and have been evaluated for this purpose. Furthermore, it presents some community aggregation programs that can serve as references for the aggregation of ECs and participation in flexibility services.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the methodology we used to analyze the literature.

Section 3 provides the definition and gives the context of the ECs studied in this article.

Section 4 presents real case studies of ECs that participate in the electricity sector, and

Section 5 summarizes the main conclusions of this study.

2. Materials and Methods

This study aims to present real-life case studies of ECs operating in the electricity sector, highlighting the importance of transferring best practices and success stories. Given the diverse nature of ECs (some focused on energy efficiency, self-consumption, or electric mobility), it would be impractical to present all existing examples. Not all ECs are involved in selling energy to the grid or offering ancillary or flexibility services. Therefore, this study concentrates on a selection of relevant case studies from various contexts and countries, ensuring a versatile approach.

The methodology employed involved reviewing real cases of ECs with specific characteristics, such as the following:

Providing energy to different users, agents, and/or directly to the electricity sector;

Participation in ancillary or flexibility services.

To gather data on these cases, a wide range of sources were consulted, including national and international publications, public and private databases, and the websites of relevant projects. Additionally, the legal structures that can constitute an Energy Community were also considered.

3. Energy Community Concepts

The European directive introduced two distinct concepts of ECs: Renewable Energy Communities (RECs) [

1] and Citizen Energy Communities (CECs) [

2]. An REC is a legal entity characterized by several key features. It is based on open and voluntary participation, ensuring autonomy and effective control by partners or members who are located near renewable energy projects that are owned and developed by the entity. These partners or members can include natural persons, small and medium-sized enterprises, or local authorities, such as municipalities. The primary purpose of an REC is to deliver environmental, economic, or social benefits to its partners, members, or the local area in which it operates, rather than seeking financial gain. Furthermore, member states are required to guarantee that RECs have the right to access all relevant energy markets, whether directly or through aggregation, on a non-discriminatory basis.

On the other hand, a CEC is also a legal entity, but it emphasizes voluntary and open participation with effective control exercised by individuals, local authorities (including municipalities), or small businesses. Similar to RECs, the primary objective of CECs is to provide environmental, economic, or social benefits to their partners, members, or the local community, rather than focusing on financial returns. CECs engage in a wide range of activities, including the generation of energy (potentially from renewable sources), distribution, supply, consumption, aggregation, and storage of energy. They may also provide energy efficiency services, electric vehicle charging, or other energy-related services to their members or partners. Member states must ensure that CECs have access to all organized markets, either directly or through aggregation, under non-discriminatory conditions.

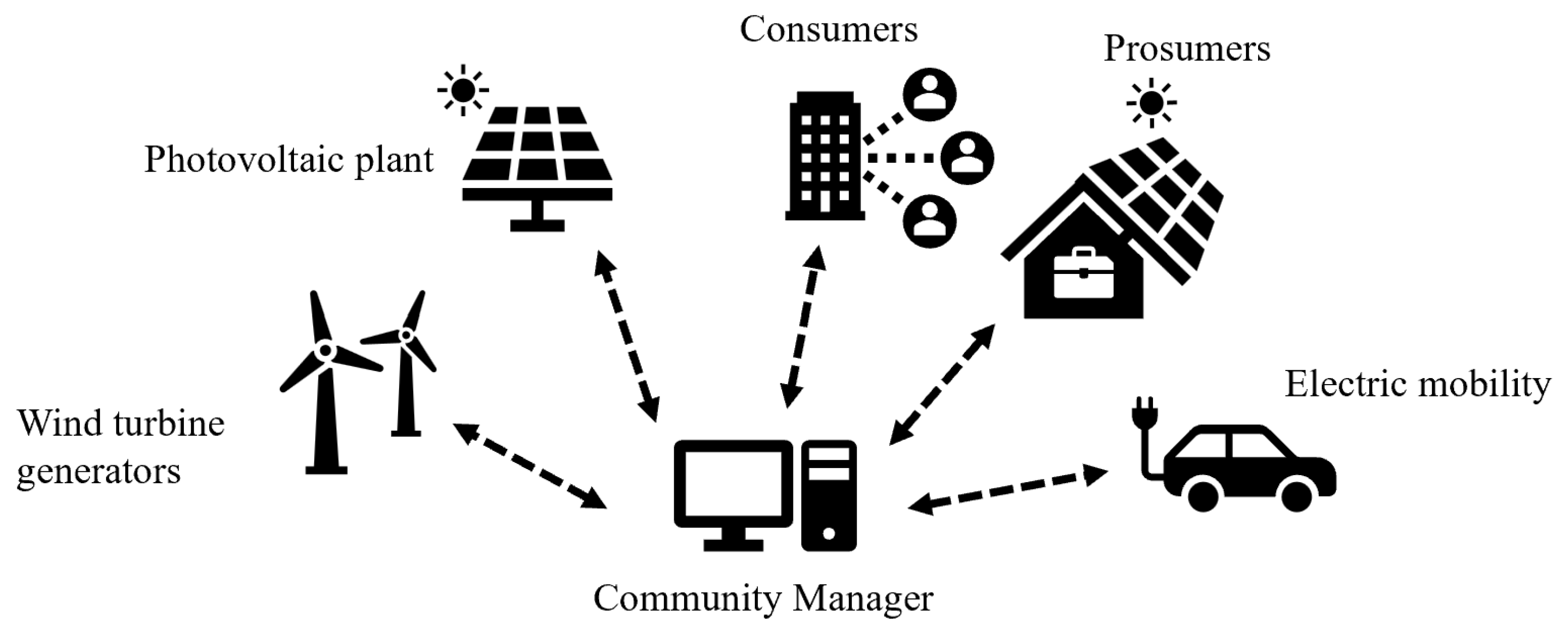

Figure 1 illustrates some of the components that can form an EC. This legal entity can consist of energy-consuming buildings or homes, as well as businesses and prosumers, i.e., consumers who also produce energy. It can also include electric mobility, and public charging stations for electric vehicles, which can serve as flexible loads for the community and can be managed. On the generation side, most ECs currently have photovoltaic installations, but they can also include other renewable and even conventional technologies. In contrast to CECs, RECs can only include renewable generation technologies due to the definition of the European Directive.

5. Conclusions

This study reviewed real cases of ECs in different European countries. The results have demonstrated the participation of ECs in P2P market platforms through pilot projects. It also showed that several electricity cooperatives, one of the most common forms of ECs, participate in energy trading with their members and other entities. In addition, several citizen projects sell their energy, mainly from renewable sources, to various energy supply cooperatives.

The case studies analyzed in this article highlight the diverse strategies employed by ECs across different countries. These strategies include innovative approaches such as renting public rooftops for photovoltaic installations, restricting membership through codes, and acquiring facilities or purchasing green energy from community projects. This diversity underscores that there is no single model for ECs to secure generation resources but rather a spectrum of approaches tailored to specific regulatory and market conditions.

ECs are also engaged in various activities beyond just electricity supply. These include electric mobility and flexibility services. While these activities are not mutually exclusive, each community often focuses on a particular area that aligns with its strengths or primary market participation strategy. For instance, some ECs may prioritize electricity supply while others might concentrate on offering electric mobility services or providing flexibility to the grid.

The transposition of European directives into national legislation varies considerably from country to country, affecting the development and operation of ECs. Austria, for example, has successfully integrated REC and CEC regulations into its national laws and has a robust number of operational ECs. In contrast, Spain is still in the process of approving its draft law for EC regulation, which has slowed the development of these communities. Meanwhile, countries like Germany and the Netherlands benefit from the long-standing tradition of community energy projects, which has facilitated the proliferation of ECs.

Based on these findings, we recommend that energy policies emphasize enabling ECs to participate effectively in the energy market by providing strategic frameworks tailored to their unique contexts. Additionally, implementing pilot programs for offering flexibility services, supported by solid legal frameworks, can foster confidence among citizens and encourage broader participation. It is crucial to recognize that ECs are more than just energy collectives; they represent a collaborative effort between different stakeholders in the sector, who complement and enhance each other’s capabilities.

This article contributes to the academic discourse by analyzing the various models of EC participation in the electricity sector and disseminating implementation strategies that can serve as a foundation for emerging citizen-led energy projects.

The conclusions drawn in this article are based on the analysis of specific case studies related to ECs and the corresponding regulations. However, it is important to acknowledge certain limitations within this study. The conclusions would benefit from a broader range of case studies, particularly by including examples from countries not covered in this research, such as Croatia and Lithuania. Additionally, most of the analyzed cases are concentrated in European countries, except for the United States. Expanding the scope to include ECs from other continents, like Australia, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of global trends.

Furthermore, the study did not encompass all existing aggregation models. The focus was primarily on community aggregation models, illustrated by real operational cases in the United States. This selective approach leaves room for further exploration of other aggregation models that may also play a significant role in the integration of ECs into the market.

Building on this research, future studies could explore several key areas. These include the implementation of flexibility markets for the participation of ECs, the development of regulatory frameworks that facilitate aggregator participation in electricity markets, and the support of international strategies to enhance the involvement of ECs in both local and national energy markets.

There is a considerable amount of work to be conducted to facilitate the direct engagement of ECs in the market, either independently or through aggregators. While there is evident enthusiasm for such projects, particularly in countries like Spain, the progress is hindered by a lack of regulatory momentum. Strengthening these regulatory frameworks will be crucial for realizing the full potential of ECs in the energy sector.